Shocks, risks and global value chains in a COVID-19 world

←

→

Page content transcription

If your browser does not render page correctly, please read the page content below

Shocks, risks and global value chains in a COVID-19 world by Frank Van Tongeren, OECD Trade and Agriculture Directorate In just six short months, the COVID-19 pandemic has swept the globe, leaving but a few island nations untouched. The virus and the measures required to contain it have left in in their wake a global economy damaged beyond what was thought possible after the financial crisis over a decade ago. Unemployment in the OECD area increased by an unprecedented 2.9 percentage points in April alone, up from 5.5% the previous month, and the recent OECD Economic Outlook projects that ‘five years or more of income growth could be lost in many countries by the end of 2021’. The pandemic has painfully reminded us of the vulnerability of the global economy to unexpected shocks. In the early stages of the pandemic, we saw dramatic shortages in the global availability of personal protective equipment and other medical supplies due primarily to surging demand, in some cases exacerbated by trade restricting measures. This raised questions about whether the relative gains and risks from deepening and expanding international specialisation in global value chains (GVCs). Global value chains organize the cross-border design, production and distribution processes, creating much of what we purchase and consume every day: from food and medicines to smartphones and cars. Some people now wonder whether more localised production of key goods would provide greater

security against disruptions that can lead to shortages in supply and uncertainty for consumers and businesses. Modelling the question of reshoring post- COVID While we do not have a more ‘localised’ world at hand that we can use to compare vulnerability to shocks such as the COVID-19 pandemic, we can use economic models to explore such a counterfactual scenario and equip policy makers with information that can help them start to answer these pressing questions. Recent simulations with a large-scale OECD trade model, METRO, compare two stylised versions of the global economy: the interconnected economies regime captures production fragmentation in GVCs much as we see it today, but also taking into account the changes already resulting from the COVID-19 crisis. These include reductions in supply and productivity of labour, reductions in demand for certain goods and services, and a rise in trade costs related to new customs procedures for goods and restrictions on temporary movement of people in services. In the localised -‘turning inward’- regime, production is more localised and businesses and consumers rely less on foreign suppliers. This illustrative counterfactual world is constructed through a global rise in import tariffs to 25%, combined with national value-added subsidies equivalent to 1 % of GDP on labour and capital, directed to domestic non-services sectors to mimic rescue subsidies that favour local production. It is also assumed that, in the localised regime, firms are more constrained in switching between different sources of products they use, making international supply chains more rigid. Those assumptions create strong incentives to increase domestic production and rely less on international trade and are meant to illustrate a range of potential implications of policies

that aim at more localisation. Starting from these two baseline scenarios for future trade regimes, the models can be exposed to a ‘supply chain shock’ similar to the disruption COVID-19 caused to global supply chains. During the pandemic, disruptions to labour, transport and logistics increased the cost of exporting and importing to a similar extent. The analysis, laid out in Shocks, risks and global value chains: insights from the OECD METRO model explores how the interconnected economies and the localised regimes compare in terms of the propagation of, or insulation from such shocks. The ‘supply chain shock’ is simulated with a 10% increase in the costs of bilateral exports and imports between a given region and all other countries. Because a shock that decreases trade costs by 10% –a big drop in oil prices for instance— would have effects of the same magnitude, but in the opposite direction, both the downside and upside stability in the two regimes can be explored. Increased localisation leads to GDP losses and makes domestic markets more vulnerable Current debates over future trade regimes often focus on a purported trade-off between efficiency and security of supply. This model simulation study allows us to evaluate the two simulated regimes for both. It found that a localised regime, where economies are less interconnected via GVCs, has significantly lower levels of economic activity and lower incomes. Increased localisation would thus add further GDP losses to the economic slowdown caused by the COVID-19 pandemic. Furthermore, even with the support and protection offered to domestic producers under a localised regime, not

all stages of production can be undertaken in the home country, and trade in intermediate inputs and raw materials continues to play an important role in domestic production. In that context, less international diversification of sourcing and sales means that domestic markets have to shoulder more of the adjustments to absorb shocks, and this translates into larger price swings and large changes of production, and ultimately to greater variability of incomes. In this sense, the more localised regime delivers neither greater efficiency nor greater security of supply. Recent OECD analysis on The face mask global value chain in the COVID-19 outbreak offers an concrete illustration. It showed that producing face masks requires a multitude of inputs along the value chain, from non-woven fabric made with polypropylene to specialized machinery for ultra-sonic welding. While the production itself does not require high- tech inputs, localising the production of just this one good would require high capital investments which would need to be supported during periods when demand shrinks and localized production is not competitive. With current technologies it would therefore be excessively costly for every country to develop production capacity that matches crisis-induced surges in demand and which encompasses the whole value chain from raw materials through distribution for a whole catalogue of essential goods to match any potential crisis—foreseen and otherwise.

More localisation also means more reliance on fewer sources of—and often more expensive—inputs. In this regime, when a disruption occurs somewhere in the supply chain, it is harder, and more costly, to find ready substitutes, giving rise to greater risk of insecurity in supply. This is also the case for sectors that are often seen as strategic: food, basic pharmaceuticals, motor vehicles and electronics. Work on Trade interdependencies in Covid-19 goods further supports these findings, demonstrating that no single country produces efficiently all the goods it needs to fight COVID-19. Indeed, while the United States and Germany tend to specialise in the production of medical devices, China and Malaysia are most specialised in producing protective garments.

While the argument about GVCs is often posited as one of efficiency versus security, OECD research illustrates that greater localisation fails to achieve either. The localization of production is costly for the most developed countries and virtually impossible for the less developed—while at the same time a localised regime provides less protection from the impact of shocks. An alternative, more effective and cost-efficient solution to the challenges posed by shortages in some key equipment during demand surges may involve the combination of strategic stocks; upstream agreements with companies for rapid conversion of assembly lines during crises and supportive international trade measures. If this crisis has taught us anything, it is that viruses, shocks, and economic consequences know no borders, and the one and best option that we have is to meet these challenges together. References: OECD Economic Outlook. Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), 24, June 2020. http://www.oecd.org/economic-outlook/june-2020/ Shocks, risks and global value chains: insights from the OECD METRO model. Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), 29, June 2020. https://issuu.com/oecd.publishing/docs/metro-gvc-final

The face mask global value chain in the COVID-19 outbreak: Evidence and policy lessons. Organisation for Economic Co- operation and Development (OECD), 4, May 2020. http://www.oecd.org/coronavirus/policy-responses/the-face-mask -global-value-chain-in-the-covid-19-outbreak-evidence-and- policy-lessons-a4df866d/ Trade interdependencies in Covid-19 goods. Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), 5, May 2020. http://www.oecd.org/coronavirus/policy-responses/trade-interde pendencies-in-covid-19-goods-79aaa1d6/ India’s export performance: the goods and services nexus By Isabelle Joumard, India Desk, OECD Economics Department The government aims at making India an export hub, to help boost job creation. The export-to-GDP ratio has risen fast since the early 1990s and now stands broadly at par with China (Figure 1). The large share of services in total exports however stands out: while India has performed very well in exporting IT services, exports of goods have lagged behind. Exports of labour-intensive manufacturing products could grow faster and contribute to job creation. The 2019 OECD Economic Survey of India discusses policies to make India’s exports more competitive.

Performance of services exports has been stellar. India’s share of world services trade more than quadrupled from 0.5% in 1995 to 3.5% in 2018 and India has become a major exporter of business services, notably in the Information, Communication and Technology (ICT) sector. Medical and wellness tourism is also performing well, with patients seeking high-quality medical treatment at competitive prices in some Indian hospitals. Exports of goods have displayed mixed results. India has gained market shares for some skill- and capital-intensive goods, including pharmaceuticals and refined oil. However, performance in exporting textiles, leather and agricultural products has disappointed. Looking at the labour-intensive components of the textile sector (including garment) provides an illustration: Vietnam now has a larger market share (Figure 2).

Domestic factors partly explain the relatively low performance of labour-intensive exports. Labour regulations are more stringent for industries and large firms. This creates incentives for firms to stay small, making it difficult to exploit scale economies. Electricity prices are also relatively high and transport infrastructure bottlenecks persist despite recent improvements. This hampers the competitiveness of manufacturing goods which tend to be more intensive in energy and transport than services. The length and costs to acquire land, combined with relatively high financing costs, are further weighing on firms’ competitiveness. Barriers to trade also play a role. Import tariffs on goods declined substantially in the 1990s and 2000s. They have been raised again since 2017 and are relatively high (Figure 3). Expensive imports of intermediate products, due to import duties, can penalise Indian exporters if they do not receive the full compensation for the duties paid on inputs — this is

often the case in a sector like the apparel sector where small enterprises account for the lion’s share. The complexity of India’s tariff structure further raises administrative and compliance costs. Overall, import duties run against the objective of making India an export hub. Trade in services also faces some restrictions, with local suppliers protected from foreign competition (Nordås, 2019; OECD, 2017). Only Indian nationals are allowed to practise as lawyers or architects. Services trade restrictions, as assessed by the OECD, are also relatively high in the banking, insurance, rail and air transport, and telecommunication sectors (Figure 4). Because services are key inputs for the manufacturing sector and support participation in global value chains, stringent regulations on services are weighing on manufacturing costs and thus on export performance.

OECD simulations suggest that India would be a major beneficiary of a multilateral reduction in barriers to services trade (OECD, 2019b). Better priced services intermediates would foster a rapid expansion of production and job creation in the manufacturing sector. It would further support wages for low-skilled workers. Simulations also reveal that, even in the absence of a multilateral agreement, the economy would gain from a unilateral liberalisation of trade and investment (Joumard et al., 2020). India could make exports a new growth engine. India’s trade prospects are relatively positive as it has specialised in sectors which will likely be in high demand in the future (e.g. ICT services, pharmaceuticals and medical devices) and in fast growing destinations (with a large share of its exports to emerging market economies). To unlock its potential to seize market shares in the labour-intensive manufacturing segment, India should modernise labour and land regulations, address infrastructure bottlenecks and open up further the

services sector to trade and investment. Better and less expensive services – financial, marketing, distribution, legal, transport, etc. – will increase competitiveness in the manufacturing sector, boost job creation and meet the aspirations of women and new comers on the labour market. References Joumard I., M. Dek and C. Arriola (2020), “Challenges and opportunities of India’s enhanced participation in the global economy”, OECD Economics Department Working Paper No. 1597. https://doi.org/10.1787/a6facd16-en Nordås, H.K. (2019) “Services trade restrictiveness index, methodology and application: The Indian context” in D. Chakraborty and Nag, B. (eds), India’s Trade Patterns and Export Opportunities: Reflections through Trade Indices and Modelling Techniques, New Delhi: Sage Publications OECD (2017), Services Trade Policies and the Global Economy, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264275232-en OECD (2019a), OECD Economic Surveys: India 2019, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/554c1c22-en. OECD (2019b), Trade Policy and the Global Economy – Scenario 4: Addressing Barriers to Services Trade, OECD publishing, Paris https://issuu.com/oecd.publishing/docs/oecd-trade-scenario-4-s ervices

Statistical Insight: men’s employment more dependent on trade than women’s by Fabienne Fortanier, OECD Statistics and Data Directorate Concerns are growing that globalisation may have created a few big winners at the expense of many losers. This has stimulated efforts to analyse how trade can be made to Work for All, for example by focusing on the skills and occupations of affected workers. However, there has been less attention to the gender dimension of globalisation and global value chains, and in particular to whether they are having differing effects on men’s and women’s work. New analysis shows that men’s employment is more dependent on international trade than women’s. On average across the countries studied, 37% of men’s jobs, but only 27% of women’s jobs, depend on exports – either because the firms they work for export directly, or because they indirectly supply other firms that subsequently export. This compares to only 27% of women’s employment (Figure 1).

Source: OECD Statistics and Data Directorate estimates, based on full-time equivalent employment. Focusing on manufacturing exports only (which account for around 70% of international trade), Figure 2 illustrates that in nearly all countries, the share of women in employment that is indirectly sustained by manufacturing exports is higher than the share in employment that is directly sustained. For example, in Germany, women’s share of manufacturing jobs that is directly sustained was just over 20% in 2014 but close to 35% of indirect jobs (Figure 2).

Source: OECD Statistics and Data Directorate estimates Women’s jobs are thus both less dependent on trade overall, and less directly involved with manufacturing exports. These trends arise partly from differences in female labour participation across industries and partly from the relative contributions of these industries to total trade. Overall, women tend to work in business services and in other, mainly non- market, services, rather than in manufacturing, where on average they only account for a quarter of the workforce. However, while men account for the lion’s share of the work involved in manufacturing exports, that work generates a substantial number of upstream jobs held by women. As Figure 3 shows, for each unit of labour input in direct manufacturing exports, an additional 0.5 unit of female labour input is generated in the companies that supply exporters, as well as an additional 0.9 unit of male labour inputs. Put differently,

each job in manufacturing exports generates on average 1.4 additional jobs upstream, a third of which are jobs held by women. Source: OECD Statistics and Data Directorate estimates The nature of the upstream participation also differs significantly between men and women. While the bulk of upstream jobs are in the services sector, this is particularly true for women’s jobs. Taking again Germany as an example, Figure 4 shows that less than 20% of women’s upstream jobs are in industrial and goods sectors (Agriculture, Utilities, Construction, Manufacturing and Mining), compared to 45% for men.

Source: OECD Statistics and Data Directorate estimates. The detailed data compiled for this analysis on the export-dependency of men’s and women’s jobs provide an indication of the extent to which reducing gender wage gaps will depend on encouraging more women to seek employment in higher-paying sectors of the value chain. How the indicators were constructed The estimates of female employment in global value chains were produced by combining the TiVA ICIO (2008-2014) with data on labour input by industry, measured in hours worked as reported in the National Accounts, broken down by gender. The gender breakdown was derived from Labour Force Surveys, which is the only sufficiently detailed source to support this

analysis, using

a combination of total employees (male/female) broken down by

industry,

corrected for average weekly working hours to adjust for the

fact that in many

countries, women work fewer hours on average. For details on

the calculations, as

well as on the estimations made in case of missing data, see

the accompanying

background note.

Further reading

Gender in Global Value Chains: the

impact of trade on male and female employment

Background note on women in GVCs

Gender

in Global Value Chains: how does trade affect male and

female employment?,

OECD Statistics Newsletter (2018), Issue 68, July 2018

Making trade and

digitalisation work for all

by Laurence Boone, OECD Chief EconomistFor some, the financial crisis was an

eye-opener exposing the inequalities

in life chances between those with the

right skills and those without,

between those born and educated in the

right places and those who were not.

But for many others the growing gap

in well-being has been a reality for decades.

Widening inequalities threaten economic growth, undermine

trust in government and democracy, and fuel discontent with

the multilateral rules-based system of market economies.

Governments can and should seek to reverse the trend towards

growing inequality and ensure that economic growth benefits

everyone. Making trade and digitalisation work for all is not

about idealism: it is about improving people’s standard of

living, boosting opportunities for inter-generational mobility

and ensuring a brighter future for all.

The OECD has developed a whole-of-government approach, built

around analysis of policies and strategies to ensure that the

fruits of economic growth are better shared across society. We

identify comprehensive policy packages that optimise gains in

GDP and households incomes, including among the less well off.

There are no one-size-fits-all reform packages, but key

principles can guide policy-making for inclusive growth by

targeting three broad areas for action: firms, skills and

workers.

Firms: to promote business dynamism and the diffusion of

knowledge by, for instance, lowering barriers to market

entry or improving the efficiency of the corporate tax

system.

Skills: by fostering higher quality education and

greater innovation and through better-adapted R&D

policies so that innovation fosters productivity gainsacross all types of activities.

Workers: with policies that ensure workers benefit from

a fast-evolving labour market, including those who are

most vulnerable to the changing demand for skills and

automation, or who have less bargaining power.

The principles build on extensive OECD empirical research into

the effects of pro-growth structural policy reforms on

household disposable incomes. This research highlights the

trade-offs between productivity gains and inequality when they

appear, as well as possible synergies between efficiency and

equity.

The policies needed to raise equality of opportunity are

clear. It is striking that a child whose parents did not

graduate from secondary school has only a 15% chance of doing

so himself or herself, compared to a 65% chance for more well-

off children. Equality of opportunities can foster social

mobility: an equal access to education, finance, jobs, health,

transport and other public services helps compensate for the

environment in which people were born. Good quality education

is primordial throughout life – especially early childhood

education, but also training at work, which too often benefits

those already well educated.

Other reforms have more ambiguous effects on efficiency and

equity. Policies which reduce labour costs by lowering

unemployment benefits increase employment, but also make the

vulnerable more fragile when there is an economic downturn.

Meeting the twin objectives of raising employment while

mitigating the negative consequences on poor households

requires well-targeted active labour market policies to

enhance the employability of low-skilled workers, the long-

term unemployed and discouraged job seekers.

Some policies have more ambiguous effects: raising the minimum

wage reduces inequality, just as stronger unions may

strengthen workers’ bargaining position. When firms have theoption of investing in automation technology, striking the right balance between bargaining power and the economic environment is crucial to preserving employment with appropriate wage gains. Spurring productivity, by easing barriers to firm entry and competition in product markets, supports GDP growth gains without exacerbating inequality, but only to the extent that the associated job gains are fairly equally shared across households. This requires the distributional effects of higher employment – which tends to benefit the less affluent households disproportionately – to more than offset those of higher labour productivity, which tends to benefit the wealthiest households. Inclusive growth also requires devoting careful attention to transition. Opening markets to trade or progress in technology inevitably leads to the decline of certain companies and obsolescence of particular skills. Accompanying measures – building on an active partnership between employers and governments, often at the regional level – can help workers and strengthen trust in the protective capacity of governments. Safety net packages and trampoline policies for keeping workers in the labour markets are all relevant. For example, in Sweden, job security councils, founded by employers, assist workers whose employment is put at risk when firms restructure. The programmes have enabled 85% of displaced workers to find a new job within a year, a higher rate than any other OECD country. Conversely, the US Trade Adjustment Assistance and the EU Globalisation Adjustment Fund, which lack such partnerships, have barely benefitted those affected by the displacement of economic activities. It is important to acknowledge that transitional policy responses have limits. This is especially the case for persistent shocks concentrated in specific regions, sectors or skills. When distributional effects are persistent, direct fiscal policy measures may be needed to restore equity and

opportunity. These may include well-designed wealth and inheritance taxation, paying particular attention to the progressivity of the tax system, and better targeting social benefits towards those who need those most. Separately at the global level, the international programme to tackle Base Erosion and Profit Shifting (BEPS) and increase information transparency of the tax system will help strengthen the level- playing field and ensure a fair share of firms’ revenues is allocated to where value added is produced. This will help stabilise government revenues and ensure redistribution benefits to those who need it most, but perhaps more importantly may help increase trust in multilateral cooperation. Sustained growth is a pre-condition for improving living standards and job creation, but sustainability depends on an effective and perceived broad sharing of the growth dividends. The OECD has been promoting an inclusive growth framework based on three pillars: equal opportunities, business dynamism and inclusive labour markets, efficient and responsive governments. Implementation needs to start today. References: OECD (2018), Opportunities for All: A Framework for Policy Action on Inclusive Growth, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264301665-en. Causa, O., M. Hermansen and N. Ruiz (2016), “The Distributional Impact of Structural Reforms”, OECD Economics Department Working Papers, No. 1342, OECD Publishing, Paris, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/5jln041nkpwc-en.

The global impact of weaker

demand growth in China

by Nigel Pain and Elena Rusticelli,

Greater international integration has modified the

transmission channels and the impact that external shocks have

on domestic economies via increased trade openness and

exposure to global financial developments. One important

change, discussed in the special chapter of the latest OECD

Economic Outlook, is that growth prospects in OECD economies

have become more sensitive to macroeconomic shocks in non-OECD

countries. This reflects the rising share of the emerging

market economies (EMEs) in global trade and finance. EMEs now

account for one-fifth of world trade, up from around one-tenth

two decades ago.

Changes in trade patterns and also in the intensity of trade

(trade openness) have implications for the strength of the

spillovers from any shocks in the EMEs. One particular example

– the size of spillovers from a negative demand shock in China

– is discussed below, using simulations on the global

macroeconomic model NiGEM. The scenario considered is a 2-

percentage point decline in Chinese domestic demand growth

that persists for two years.

The trade-related spillovers from this shock are considered

using versions of the model with different sets of trade

patterns and different levels of trade openness (the share of

trade in GDP).

In a first scenario, the shock is simulated at a single

point in time with two different sets of bilateral trade

linkages in the model – the linkages that existed in1995 and those that existed in 2016. The share of China

in total global trade rose by close to 8 percentage

points between these years.

In a second scenario, the shock is simulated using a

single set of bilateral trade linkages – those for 2016

– but with the shock occurring at two different starting

periods with very different levels of trade openness. On

average across economies, trade openness is 11

percentage points higher in the second starting point

for the shock than in the first. This change is broadly

comparable to the rise in trade openness in the decade

or so prior to the financial crisis.

The adverse effects of the China shock on GDP growth in other

countries increase as China becomes more integrated into

global markets and as each country becomes more open to trade

(figure below). In the scenarios considered, negative

spillovers increase by more when trade openness is changed

than from the stronger role of China in global trade, thus

indicating that the general rise in cross-border trade over

recent history contributes more extensively to changing

transmission of shocks than the increase in the weight of

single countries. GDP growth in most major OECD economies is

reduced modestly, by 0.1-0.2 percentage points per annum, with

a stronger impact in Japan. Negative output spillovers are

larger in open economies more exposed to China via tighter GVC

linkages, such as East Asia or commodity exporters.

GDP growth in China declines by between 1¼-1½ per cent per

annum, depending on the particular scenario considered, with

import demand falling sharply. In the scenario with the higher

level of trade openness, world trade growth declines by 1

percentage point per annum relative to baseline. At the same

time, the slowdown in China puts downward pressure on export

prices and import prices decline in all trade partners,

partially helping to correct negative growth spillovers. Such

effects become more important as the share of trade with Chinaincreases, and as economies become more open to trade. The negative output spillovers would be larger still if monetary policy did not react, or was unable to react, to offset the adverse demand shock. Central Banks, targeting the deviation of inflation and nominal GDP from their target levels, cut policy interest rates, which by the second year of the shock decline by 25-50 basis points on average in the OECD countries (depending on the scenario considered) and by more in the economies most heavily exposed to China. Heightened financial market uncertainty and weaker commodity prices could intensify the adverse impact of a demand shock in China over and above the direct trade-related impact considered here (OECD, 2015). References: OECD (2015), OECD Economic Outlook, Volume 2015 Issue 2, OECD Publishing, Paris. OECD (2018), OECD Economic Outlook, Volume 2018 Issue 1, OECD Publishing, Paris.

Brexit and Dutch Exports:

Fewer glasshouses, more glass

towers as agri-food shrinks

and finance gains.

by Donal Smith, OECD Trade Directorate and Economics

Department

The Netherlands is likely to be one of the

European countries that is going to be

significantly affected by the United Kingdom’s

planned departure from the European Union

(Brexit). As an open economy with strong trade

and investment links to the United Kingdom,

the Netherlands is exposed to increases in

barriers to trade between the United Kingdom

and EU (Vandenbussche et al., 2017). New OECD simulations show

the potential extent of this impact, as well as the different

sectors of the Dutch economy likely to be affected.

The sector-level impacts will depend on differing UK trade

exposures, tariff rates and non-tariff measures (NTMs) applied

to different products; varying degrees of global value chain

integration of the sectors; and differences in sectors trade

diversification opportunities. On trade exposure for example,

the agri-food sector has a comparatively high UK exposure.

This sector accounts for 23% of the total exports of the

Netherlands to the UK while the UK market makes up 12% of

total Dutch agri-food exports (OECD 2018).[1]

An illustrative worst-case Brexit scenario – assuming the UK

leaves the EU without any trade agreement – is simulated usingthe OECD METRO model (OECD, 2015).[2] The key advantage of this analysis is that it accounts for changes in both tariff and non-tariff barriers. The scenario assumes that trade relations between the EU and UK default to the World Trade Organisation’s (WTO) Most-Favoured Nation (MFN) rules, that is, the most basic trade relationship. Relative to current arrangements, this corresponds to an increase in tariffs on Dutch trade with the United Kingdom of between 0 and 12 per cent. Simulation results show that Dutch exports to the UK would fall by 17%in the medium-term. The Dutch agri-food sector is estimated to experience a 22% fall in its UK exports (Figure 1). This is driven by a substantial 35% decline in exports in the meat products sector. Smaller materials manufacturing sectors such as wood and leather products and textiles would see a 20% fall in their UK exports. The 2% fall in production in agri-food contributes to a 7% decline in the value of agricultural land. Four of the five sectors that record the

largest declines in employment following production falls are in the agri-food sectors. Of all the non-agri-food sectors, electronic equipment would see the largest decline in total exports at 3% and the largest decline in production at 2.4% in the scenario. Access to supply chains for intermediate imports from the UK for Dutch sectors is also curtailed; intermediate imports from the UK would fall by over 40% in the finance and insurance sector in the scenario. There are a few sectors which have export gains under this scenario. These include motor vehicles, finance and insurance and transport equipment, these sectors show increases in exports to the rest of the EU as well as the United States. The gas sector expands slightly, but this translates into relatively larger gains of gross exports of 6% (to EU) and 10% (to US). [1] OECD METRO model data. [2] This shock implies a scenario could be the result of a disorderly conclusion to negotiations and can be considered something close to a worst case outcome and does not consider the impact via investment. References OECD (2018), OECD Economic Surveys: Netherlands 2018, OECD Publishing, Paris. OECD (2015), “METRO v1 Model Documentation”, TAD/TC/WP(2014)24/FINAL. Vandenbussche, Hylke and Connell Garcia, William and Simons, Wouter, Global Value Chains, Trade Shocks and Jobs: An Application to Brexit (September 2017). Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3052259 or http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3052259

Insertion de la Tunisie dans les chaines de valeur mondiales et rôle des entreprises offshore Isabelle Joumard, responsable du bureau Tunisie, Département d’Économie de l’OCDE L’ouverture de la Tunisie aux échanges internationaux a fortement progressé depuis le milieu des années 90, témoignant des avantages comparatifs du pays. Les exportations ont sensiblement augmenté, tirées par le secteur manufacturier, avec une transformation en faveur de secteurs plus intensifs en technologie et en compétences. De plus, l’analyse des échanges commerciaux sur la base de la valeur ajoutée remet en cause la perception selon laquelle les activités à faible teneur en valeur ajoutée dominent. Cette analyse montre aussi que le degré d’intégration de la Tunisie dans les chaines de valeur mondiales est similaire à celui de pays de l’OCDE, le Portugal notamment, et supérieur à celui de nombreux pays émergents. La montée en gamme et la diversification des exportations augurent de plus d’un potentiel de croissance de l’économie tunisienne élevé.

Cette bonne performance à l’exportation est pour l’essentiel le fait d’entreprises entièrement exportatrices (dites offshores). Le secteur offshore dégage un excédent commercial croissant. La contribution des entreprises du secteur à la création d’emplois formels a aussi augmenté – en 2016, les entreprises du secteur offshore contribuaient à hauteur de 34% des emplois formel du secteur privé – alors que le travail informel reste un problème majeur (environ 50% des jeunes). Néanmoins, ces entreprises sont pour l’essentiel localisées proches des ports, contribuant à la concentration géographique de l’activité économique. En outre, l’effet d’entrainement sur le reste de l’économie est faible : les entreprises offshore s’approvisionnent peu sur le marché local et servent rarement la demande locale. La complexité des procédures douanières, fiscales et administratives est perçue par les entreprises comme une barrière aux échanges avec les entreprises du régime onshore. De leur côté, les entreprises du secteur onshore sont pénalisées par des difficultés lors du passage en douane de leurs produits et des services logistiques peu performants.

La levée des contraintes à l’exportation rencontrées par les entreprises du secteur onshore et le décloisonnement entre régimes offshore et onshore permettraient à la Tunisie de se hisser dans les chaines de valeur mondiales et d’en tirer plus d’avantages, notamment en termes de progrès technologique, de création d’emplois et de richesse. Références : Joumard I., S. Dhaoui et H. Morgavi (2018), « Insertion de la Tunisie dans les chaines de valeur mondiales et rôle des entreprises offshore », Document de travail du Département d’Économie N°1478. OCDE (2018), Étude économique de l’OCDE sur la Tunisie.

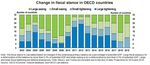

Stronger Growth but Risks loom large By Álvaro S. Pereira, OECD Chief Economist ad interim, Economics Department After a lengthy period of weak growth, the world economy is finally growing around 4%, the historical average of the past few decades. This is good news. And this news is even better knowing that, in part, the stronger growth of the world economy is supported by a welcome rebound in investment and in world trade. The recovery in investment is particularly worth emphasising, since the fate of the current expansion will be highly dependent on how investment will perform. Although long anticipated, the pick-up in investment remains weaker than in past expansions. The same is true for global trade, which is expected to grow at a respectable, albeit not spectacular, rate, unless it is derailed by trade tensions. However, contrary to previous periods, 4% world growth is not due to rising productivity gains or sweeping structural change. This time around the stronger economy is largely due to monetary and fiscal policy support.

For many years, monetary policy was the only game in town. During the international financial crisis, central banks cut interest rates aggressively, injected funds into the economy and purchased assets at a record pace in an attempt to boost the economy. In contrast, in most countries, fiscal policy remained prudent or even became contractionary. Still, historically low interest rates provided an opportunity for governments to use their available fiscal space to help foster growth, as the OECD argued forcefully in 2016. Many OECD governments are now following this advice. At first, the resources enabled by lower interest payments were used by governments to avoid cutting expenditures or raising taxes. With the improving economic situation, many governments have started to undertake additional fiscal easing. Now that monetary policy is finally starting to return to normal, governments are stepping in to provide fiscal policy support. We can say that fiscal policy is the new game in town: three quarters of OECD countries are now undertaking fiscal easing. The fiscal stimulus in some countries is very significant, while it is less ambitious in other countries. Still, this fiscal easing will have important repercussions

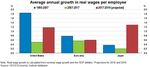

for the world economy. In the short run, it will add to growth. However, countries that have been experiencing longer expansions might find that this fiscal stimulus (where it is large) will also add to inflationary pressures in the medium term. Only time will tell if these short-run gains might be offset by some medium-term pain. What matters is that, in making these choices, governments are fully aware of the medium-term impact of their policies, and do not focus only on the short-term benefits from fiscal stimulus. The strong growth we are witnessing is also associated with robust job creation in many economies. In fact, it is particularly satisfying to see that in the OECD area, unemployment is set to reach its lowest level since 1980, even though it remains high in some countries. Thanks to this robust job creation and the related intensifying labour shortages, we are now projecting a rise in real wages in many countries. This increase is still somewhat modest. However, there are clear signs that wages are finally on the way up. This is an important development, since the global crisis had a severe impact on household incomes, particularly for the unskilled and low-income workers.

In spite of all this good news, risks loom large for the global outlook. What are these risks? First and foremost, an escalation of trade tensions should be avoided. It is worth remembering that, in part, the rise in trade restrictions is nothing new. After all, more than 1200 new trade restrictions have been implemented by G20 countries since the outset of the global financial crisis in 2007. Still, as outlined in Chapter 2, since the world economy is much more integrated and linked today than in the past, a further escalation of trade tensions might significantly affect the economic expansion and disrupt vital global value chains. Another important risk going forward is related to the rise in oil prices. Oil prices have risen by close to 50% over the past year. Persistently higher oil prices will push up inflationary pressures and will aggravate external imbalances in many countries. In the past few years, very low interest rates have encouraged borrowing by households and corporations in some countries and led to overvaluation of assets (e.g. houses, equities) in many others. In this context, rising interest rates might be challenging for highly indebted countries, families and corporations. Of course, this rise in interest rates has been widely anticipated and should thus not cause any major

disruptions. Nevertheless, if inflation rises more than expected and central banks are forced to raise rates at a faster pace, it is likely that market sentiment could shift abruptly, leading to a sudden correction in asset prices. A swifter rise in interest rates in advanced economies might also continue to lead to significant currency depreciation and volatility in some emerging market economies (EMEs) that are highly reliant on external financing and facing internal or external imbalances. Geopolitical tensions might also contribute to sudden market corrections or a further rise in oil prices. Brexit and policy uncertainty in Italy could add pressures to the expansion in the euro area. What does this all mean for policy? Since private and public debt remain high in some countries, improving productivity, decreasing debt levels and building fiscal buffers is key to strengthen the resilience of economies. As monetary and fiscal policies will not be able to sustain the expansion forever and might even contribute to financial risks, it is absolutely essential that structural reforms become a priority. In the past couple of years, few countries have undertaken substantial structural reforms. Most of the countries that reformed are large EMEs, such as Argentina, Brazil and India. In the advanced economies, important labour reforms were introduced in France and a sweeping tax reform was implemented in the United States. However, as the 2018 OECD Going for Growth points out, these important exceptions do not counter the rule that reform efforts have been lagging. Why is this important? Because the only way to sustain the current expansion and to make growth work for all is to undertake productivity-enhancing reforms. As many OECD Education Policy Reviews and OECD National Skills Strategies show, it is crucial to redesign curricula to develop the cognitive, social and emotional skills that enable success at work, and to improve teaching quality and the resources necessary to deliver those skills effectively. In many

countries, investment in quality early childhood education and vocational education and apprenticeships are of particular importance. Skills-enhancing labour-market reforms are also crucial. Reforms to boost competition, improve insolvency regimes, reduce barriers to entry in services and cut red tape are also key for making our economies more dynamic, more inclusive and more entrepreneurial. Investment in digital infrastructure will also be essential in this digital age. In addition, there are significant opportunities to reduce trade costs in both goods and, in particular, services, boosting growth and jobs across the world. In spite of stronger growth, there is no time for complacency. Structural reforms are vital to sustain the current expansion and to mitigate risks. Therefore, at this juncture of the world economy, it is truly crucial to give reforms a chance. After monetary and fiscal policies have done their jobs, it is time for reforms to sustain the expansion, to improve well- being, and to make growth work for all. References Economic Outlook, May 2018. La croissance s’affermit, mais des risques

assombrissent fortement l’horizon Álvaro S. Pereira, Chef économiste de l’OCDE par intérim, Département des affaires économiques Après une longue période de croissance atone, l’activité économique mondiale croît enfin au rythme d’environ 4 %, qui correspond à la moyenne historique des dernières décennies. C’est une bonne nouvelle, et qui apparaît encore meilleure lorsque l’on sait que ce rebond de la croissance de l’économie mondiale est, pour partie, le résultat d’un redémarrage opportun de l’investissement et des échanges mondiaux. La reprise de l’investissement mérite tout particulièrement d’être soulignée, sachant que l’avenir de l’expansion actuelle dépendra fortement de l’évolution de l’investissement. Bien qu’anticipé depuis longtemps, le redressement de l’investissement demeure plus timide que lors des phases d’expansion passées. Il en va de même pour les échanges mondiaux, dont on attend qu’ils progressent à un rythme respectable, sans toutefois être spectaculaire, à moins que des tensions commerciales ne viennent les mettre en péril.

Cependant, contrairement à ce qui avait pu être observé précédemment, cette croissance mondiale de 4 % ne repose pas sur un accroissement des gains de productivité ou sur une évolution structurelle profonde. Cette fois, l’intensification de l’activité économique est dans une large mesure imputable au soutien procuré par les politiques monétaire et budgétaire. Pendant de nombreuses années, la politique monétaire a été le seul levier utilisé. Durant la crise financière internationale, les banques centrales ont procédé à des réductions draconiennes des taux d’intérêt, elles ont injecté des fonds dans l’économie et acquis des actifs à un rythme sans précédent dans l’espoir de donner un coup de fouet à l’activité économique. Dans la plupart des pays, en revanche, la politique budgétaire est restée guidée par la prudence, voire est devenue restrictive. Au demeurant, le niveau historiquement bas des taux d’intérêt offrait aux pouvoirs publics l’occasion d’employer la marge de manœuvre budgétaire dont ils disposaient pour contribuer à relancer la croissance, selon la position défendue avec force par l’OCDE en 2016. Un grand nombre de pays de l’OCDE suivent désormais ce conseil. Dans un premier temps, les États ont utilisé les ressources dégagées

par la diminution des versements d’intérêts pour éviter d’avoir à comprimer les dépenses ou à augmenter les impôts. La situation économique s’améliorant, nombre d’entre eux se sont désormais engagés sur la voie d’un nouvel assouplissement budgétaire. Maintenant que la politique monétaire commence enfin à revenir à la normale, les pouvoirs publics s’emploient à soutenir l’activité par la politique budgétaire. On peut dire que la politique budgétaire est le levier qui a désormais la faveur des pouvoirs publics : les trois quarts des pays de l’OCDE s’engagent à présent sur la voie d’un assouplissement budgétaire. La relance budgétaire est très ample dans certains pays, et moins ambitieuse dans d’autres. Pourtant, cet assouplissement budgétaire aura des répercussions importantes sur l’économie mondiale. À court terme, il renforcera la croissance. Cependant, les pays ayant connu de plus longues périodes d’expansion s’apercevront peut-être que cette relance budgétaire (lorsqu’on lui donne de l’ampleur) accentue également les tensions inflationnistes à moyen terme. Seul le temps nous dira si les gains à court terme seront contrebalancés par des effets douloureux à moyen terme. Ce qui compte, c’est que les responsables de l’action gouvernementale, au moment de choisir telle ou telle option, soient pleinement conscients de l’impact à moyen terme de leurs politiques, et ne se bornent pas à considérer uniquement les avantages à court terme de la relance budgétaire.

La forte croissance que nous observons va également de pair avec une création d’emplois vigoureuse dans de nombreuses économies. De fait, il est particulièrement satisfaisant de constater que dans la zone OCDE, le chômage devrait atteindre son plus bas niveau depuis 1980, même s’il reste élevé dans certains pays. Compte tenu de la vitalité de la création d’emplois et de l’accentuation des pénuries de main‑d’œuvre qui en résulte, nous prévoyons désormais une progression des salaires réels dans de nombreux pays. Cette hausse est encore assez timide, mais on perçoit des signes indiquant clairement que les salaires sont enfin sur une pente ascendante. Il s’agit d’une évolution importante, sachant que la crise mondiale avait eu de graves effets sur les revenus des ménages, en particulier pour les travailleurs peu qualifiés et à faible revenu.

Malgré toutes ces bonnes nouvelles, des risques assombrissent fortement les perspectives mondiales. Quels sont-ils ? D’abord et avant tout, une escalade des tensions commerciales, qui doit être évitée. N’oublions pas que, pour une part, un recours accru à des restrictions commerciales n’a rien de nouveau. La preuve en est que plus de 1 200 restrictions nouvelles ont été instituées par des pays du G20 depuis que la crise financière mondiale a éclaté en 2007. Au demeurant, comme indiqué dans le chapitre 2, parce que l’économie mondiale est beaucoup plus intégrée et interconnectée aujourd’hui que par le passé, une nouvelle escalade des tensions commerciales pourrait porter gravement atteinte à l’expansion de l’activité économique et déclencher des perturbations dans des chaînes de valeur mondiales essentielles. Un autre risque important est lié à l’envolée des cours du pétrole. Ceux-ci ont augmenté de près de 50 % au cours de l’année écoulée. La persistance de cette tendance intensifiera les tensions inflationnistes et accentuera les déséquilibres extérieurs dans nombre de pays. Ces dernières années, le niveau très bas des taux d’intérêt a encouragé les ménages et les entreprises à recourir à l’emprunt dans certains pays et a abouti à une surévaluation

des actifs (notamment des logements et des actions) dans beaucoup d’autres. Dans ce contexte, un relèvement des taux d’intérêt pourrait mettre en difficulté les pays, les familles et les entreprises lourdement endettés. Certes, cette augmentation des taux d’intérêt a été largement anticipée et ne devrait donc pas induire de perturbations majeures. Néanmoins, si l’inflation augmente davantage que prévu et si les banques centrales sont contraintes de relever plus rapidement les taux d’intérêt, les perceptions sur les marchés pourraient s’inverser brusquement et conduire à un ajustement brutal des prix des actifs. Une remontée plus rapide des taux d’intérêt dans les économies avancées pourrait également entraîner encore d’importants phénomènes de volatilité et de dépréciations des monnaies dans certaines économies de marché émergentes qui sont très tributaires des financements extérieurs et sont confrontées à des déséquilibres internes et externes. Les tensions géopolitiques pourraient également favoriser de brusques corrections du marché ou un nouvel essor des cours du pétrole. Le Brexit et l’incertitude autour de l’action gouvernementale qui sera menée en Italie ne font qu’ajouter aux pressions qui pèsent sur l’expansion dans la zone euro. Que faut-il en déduire pour l’action publique ? Parce que la dette publique et la dette privée demeurent élevées dans certains pays, il est primordial de rehausser la productivité, de faire baisser les niveaux d’endettement et de constituer des marges de manœuvre budgétaires pour renforcer la résilience des économies. Étant donné que les politiques monétaire et budgétaire ne permettront pas d’alimenter indéfiniment l’expansion et pourraient même contribuer à accroître les risques financiers, il est absolument essentiel que la priorité soit donnée aux réformes structurelles. Ces dernières années, rares sont les pays qui ont engagé des réformes structurelles d’envergure. La plupart de ceux qui ont mené des réformes sont de grandes économies de marché

You can also read