ASPER CENTRE OUTLOOK Volume 13, Issue 1 (April 2021)

←

→

Page content transcription

If your browser does not render page correctly, please read the page content below

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Message from the Executive Director 3

The Mi’kmaq Fisheries Dispute 4

Bill C7 and Medical Assistance in Dying 9

Update on Voting Age Challenge 13

Challenging Canada’s Immigration & Refugee Law Regime15

The Supreme Court: Year in Review 17

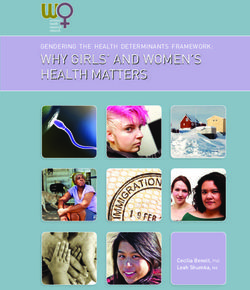

Section 15 and Fraser v Canada 20

R v Sullivan: Extreme Intoxication Defence 24

Mathur v Ontario: Moving Towards a Greener Future 28

Addressing the Use of Facial Recognition Software 31

2 Asper Centre Outlook 2021MESSAGE FROM THE EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR

It has been a really tough year for everyone. Appeal in the challenge to the Safe Third

I did not imagine that we would be facing Country Agreement which leads to refugee

another province-wide pandemic lock-down claimants being turned back at the United

in April 2021, but I suppose if we had States border. However, it was an even

listened to the experts, we should not be greater disappointment for the Court to

surprised. Through all of this, I am amazed atallow the appeal and dismiss the application.

the dedication that the students have again We will be keeping our eye on the inevitable

demonstrated to learning, to contributing to application for leave to appeal at the

the work of the Asper Centre, and to doing Supreme Court of Canada. I will also be

work that makes a difference. I am grateful looking at ways to address the treatment of

and impressed. interveners at the Federal Court (all

The Faculty of Law has also gone through interveners were refused leave to participate

some turbulence that is yet to be resolved. I in this important appeal). As we seek to be

miss working closely with the International critical of institutions which make advocacy

Human Rights Program and look forward to on behalf of marginalized communities and

a revitalized program with a permanent individuals, I trust the Faculty will continue to

director some time soon. The report of Hon. be supportive.

Thomas Cromwell did acknowledge the

precarious position that our programs are in Cheryl Milne,

without clear commitments to protecting the Executive Director

freedom of programs such as the Asper

Centre to challenge authority and advocate

vigorously for the rights of marginalized

communities and for access to justice.

It was a disappointing blow to be denied

intervener standing at the Federal Court of

3 Asper Centre Outlook 2021Reconciliation and

Recognition of Treaty Rights:

The Mi’kmaq Fisheries Dispute

by Lavalee Forbes and Julia Nowicki

T

he launch of a self-regulated commercial November. Declarations of illegality soon escalated

lobster fishery in Saulnierville, Nova Scotia into acts of violence directed towards Sipekne’katik

by Sipekne’katik First Nation brought to fishers and their property. Flares were shot at

the fore issues such as Canada’s failure to Mi’kmaq fishing boats, fishing lines were cut, traps

uphold treaties, the RCMP’s failure to protect Indig- were seized, fishers were harassed, and a lobster

enous peoples from acts of violence, and racism pound was burned down.

against Indigenous peoples. Most striking was per- Many non-Indigenous fishers have argued

haps the confusion and misinformation that that Sipekne’katik’s failure to comply with fishing

abounded with regards to the fishing rights seasons would jeopardize the health of the lobster

Mi’kmaq possess by virtue of the peace and friend- populations off the coast of Nova Scotia. Although

ship treaties they entered into with the British Aboriginal rights can be limited for conservation

Crown in the 18th century. The constitutionally pro- reasons, this position ignores the conservation

tected right to fish for a moderate livelihood was measures taken by the Sipekne’katik fishery itself,

confirmed and recognized by the Supreme Court of including their fisheries management plan. It also

Canada in the 1999 R v Marshall decision; however, ignores persuasive expert evidence which indicates

the crisis that unfolded in response to the launch of that the Sipekne’katik lobster fishery is too small to

the Sipekne’katik fishery demonstrates both how endanger the lobster stocks, which are currently

little the government has done to protect this right healthy and capable of supporting a Mi’kmaq com-

and how little this right is understood by the gen- mercial fishery.

eral population. Instead of protecting the Sipekne’katik’s con-

stitutionally-entrenched right to fish, the govern-

Summary of Present Day Dispute ment threatened to prosecute individuals for pur-

The Sipekne’katik First Nation commercial lobster chasing fish from the Sipekne’katik commercial fish-

fishery was launched on September 17, 2020 — 21 ery. While everything caught as a part of the

years after the decision in Marshall. The fishery Sipekne’katik commercial fishery was eventually

operated from September until December, with sold, these sales had to be done in secret because

members choosing to fish earlier than the federally- no buyer would openly do business with the First

mandated season because the community’s boats Nation’s fishers. By the close of the Sipekne’katik’s

were poorly equipped for winter conditions. Licenc- fishing season in December, all fishers had lost

es and lobster trap tags were issued to a number of money.

Mi’kmaq fishers by the Sipekne’katik First Nation. Back in October 2020, Prime Minister Justin

However, non-Indigenous fishers quickly responded Trudeau pledged to work with both Mi’kmaq and

to the fishery by declaring that it was illegal and in non-Mi’kmaq fishers to find a solution to the con-

violation of the federal government’s required fish- flict and to increase funding for police in the region.

ing seasons, which prohibited lobster fishing until While Mi’kmaq leaders held conversations with

4 Asper Centre Outlook 2021Fisheries and Oceans Canada (the “DFO”) through nous nations and the British Crown. After centuries

the fall months, Sipekne’katik chief, Mike Sack, of the Crown’s failure to uphold treaty obligations,

ended these talks around December. He cited a coupled with a refusal on the part of the courts to

lack of desire and ability on the part of the DFO to treat treaties as constitutional documents, treaties

protect the Mi’kmaq Nation’s constitutionally en- were constitutionalized by section 35 of the Consti-

trenched right to fish commercially. Chief Sack did tution Act, 1982, which reads as follows: “(1) The

indicate, however, that he would continue speak- existing aboriginal and treaty rights of the aborigi-

ing with Crown-Indigenous Relations Minister Car- nal peoples of Canada are hereby recognized and

olyn Bennett about Indigenous self-governance. affirmed.” The Aboriginal rights and treaty jurispru-

dence which has followed the enactment of s. 35

R v Marshall SCC 1999 has dealt primarily with interpreting the meaning

In 1999, the treaty right to fish and trade for suste- of the provision and has both limited and clarified

nance was affirmed by the Supreme Court of Cana- the definition and application of aboriginal and

da in Marshall. Donald John Marshall Jr. was a treatyrights.

Mi’kmaw man who was arrested and charged un- In 1990, the landmark case of R v Sparrow set

der the Maritime Provinces Fishery Regulations for out the test for prima facie interference with an

selling eels without a licence, fishing without a li- existing Aboriginal right and for the justification of

cence, and fishing during the close season with ille- such an interference. The test states that, in deter-

gal nets off the coast of Pomquet Harbour, Antig- mining whether prima facie interference exists, the

onish County, Nova Scotia. Marshall Jr. appealed courts should ask (1) whether the limitation is un-

his conviction on grounds he had a treaty right to reasonable, (2) whether the regulation that limits

catch and sell fish under a treaty agreed to by the the right imposes undue hardship, and (3) whether

British Crown in 1760, and it was the terms therein the regulation denies the holders of the right their

which were under dispute in this case. preferred means of exercising that right. If a prima

Today’s Aboriginal law jurisprudence contin- facie infringement is found, the question of what

ues to be based on treaties signed between Indige- “constitutes legitimate regulation of a constitution-

5 Asper Centre Outlook 2021The Mi’kmaq Fisheries Dispute

al aboriginal right” arises. In answering this ques- March 10, 1760. It was part of a series of treaties

tion, the court must consider whether there is a signed with individual Mi’kmaq communities in

valid legislative objective and whether the legisla- 1760 and 1761 intended to be combined into a

tive objective upholds the honour of the Crown. larger, single treaty which never came into exist-

The court must also ensure (1) that any allocation ence. The 1760 treaty document included a num-

of priorities after measures that secure the law’s ber of provisions ensuring peace between the

objective must give top priority to Aboriginal in- Crown and the Mi’kmaq people, as well as a nega-

terests, (2) that such laws infringe as little as pos- tive covenant, referred to after as the “Trade

sible, and (3) that the right bearers are fairly com- Clause”, through which the Mi’kmaq people

pensated. As will be further explained below, one promised to “not traffick, barter or Exchange any

legislative objective that is considered a valid rea- Commodities in any manner but with such per-

son to infringe Aboriginal rights is the goal of con- sons or the managers of such Truck houses as

servation and resource management. shall be appointed or Established by His Majesty's

Governor.” This promise at the time limited the

Six years after Sparrow, the test for identify- ability of the Mi’kmaq people to trade with non-

ing Aboriginal rights was set out in R v Van der government individuals and the Crown was to es-

Peet. The Court in this case required that for an tablish and run “truck houses” or trading posts to

activity to constitute an Aboriginal right it “must facilitate this trading. Over time, the truck houses

be an element of a practice, custom or tradition disappeared from Nova Scotia as they had fallen

integral to the distinctive culture of the aboriginal into disuse during the American Revolution.

group claiming the right.” The Court then set out

a list of factors courts should take into account In court, Marshall Jr. argued that this

when applying the test, a significant one of which trade clause and truck house provision included

was to take into account both Aboriginal and within it the right to trade, and by extension, the

common law perspectives. right to hunt, fish, and gather in support of this

trade. At the trial level, the judge found that alt-

hough the clause contained a positive right to

The Aboriginal right to hunt, bring the products of hunting, gathering and fish-

ing to truck houses, this right was extinguished

fish and gather in pursuit of upon the disappearance of the truck houses.

a ‘moderate livelihood’ was However, the Supreme Court of Canada

held differently. Justice Binnie for the majority

affirmed through the Peace wrote that when determining the scope of the

and Friendship Treaties of treaty obligations, the court may need to look be-

yond the obligations set out in the written docu-

1760 and 1761 ment to extrinsic evidence, including (1) when it is

available to show the document does not include

all terms, (2) when there is ambiguity in the face

The 1999 Marshall case drew upon the Aboriginal of the treaty, and (3) where the treaty was con-

rights framework set out in Sparrow and con- cluded verbally and afterwards written up by rep-

cerned the interpretation of an 18th century trea- resentatives.

ty signed between the British Crown and the Bearing in mind these relevant evidentiary

Mi’kmaq nation. Following a period of war and sources, including documentary records of negoti-

conflict between the British and Mi’kmaq people, ations with First Nations communities, the Court

a Treaty of Peace and Friendship was signed on held that the written document of the treaty was

6 Asper Centre Outlook 2021The Mi’kmaq Fisheries Dispute

incomplete and was to be interpreted based on most 22 years after the decision, the Government

the historical record, stated objectives of the of Canada has yet to elaborate and set these lim-

British and Mi’kmaq in 1760, and the political and its. Now, Mi’kmaq people and non-Indigenous fish-

economic context. In this case, the treaty was ers alike are calling for more clarity.

written on the assumption that Mi’kmaq people

have the right to hunt and fish in order to facilitate Post-Marshall

this trade at the truck houses. Further, the promis- Immediately following the decision in 1999, there

es of truck houses were not literal promises, ra- remained a number of unanswered questions re-

ther they represented a right for the Mi’kmaq peo- garding both the implementation and scope of the

ple to continue to obtain the necessaries of life treaty rights of the Mi’kmaq, Maliseet, and Passa-

through hunting and fishing by trade. The origin of maquoddy people. Confrontations arose soon

this clause stemmed from earlier negotiations with after amongst non-Indigenous fishers and First Na-

the Maliseet and Passamaquoddy First Nations, tions members seeking to exercise their treaty

where the restriction on trading with non- rights.

government entities was a response to an original Partial clarification came in November of

request for the provision of truck houses for trad- that year, when the Court denied The West Nova

ing made by the First Nations communities. Fishermen’s Coalition’s application for a rehearing

of Marshall No.1. The decision was seen by Indige-

As such, the regulations that prohibit fish- nous peoples as a partial backtrack, the Court

ing or selling eels without a licence prima facie vio- writing that the treaty rights of Indigenous people

lated the appellants’ treaty rights and were were not unlimited, and could be regulated bear-

deemed of no force and effect. The regulation re- ing in mind certain policy considerations such as

garding the use of improper nets was likewise an conservation and economic fairness.

infringement, as the SCC said there can be no limi- In the years that followed, the Canadian

tation on the “method, timing, and extent” of In- government, through the DFO, implemented a

digenous hunting under a treaty. Justice Binnie number of initiatives aimed at both regulating and

therefore held that, absent any justification for the providing access to commercial fishing opportuni-

regulatory prohibitions, these regulations under ties for First Nations communities in New Bruns-

the Maritime Provinces Fishery Regulations were wick, Prince Edward Island, Nova Scotia and the

of no force and effect by virtue of ss.35(1) and 52 Gaspé region of Quebec. Around $545 million was

of the Constitution. Marshall Jr. was acquitted on allocated to providing communities licences, gear,

all charges. As such, the right to hunt, fish and boats and training through the Marshall Response

gather in pursuit of a ‘moderate livelihood’ was Initiative in exchange for promises to abide by the

affirmed through the Peace and Friendship Trea- same regulations governing non-Indigenous fisher-

ties of 1760 and 1761, affecting 34 First Nations in ies.

New Brunswick, Prince Edward Island, Nova Scotia, The program was replaced in part by the At-

and the Gaspé region of Quebec. lantic Integrated Commercial Fisheries Initiative

The Court defined moderate livelihood as (AICFI), which likewise provides financial resources

including “such basics as ‘food, clothing and hous- to support the Marshall communities in commer-

ing, supplemented by a few amenities’, but not the cial fishing enterprises and diversify their econom-

accumulation of wealth’”. The catch limits that ic bases. Thirty-three of the thirty-four eligible

could be reasonably expected to produce a moder- communities participate in the AICFI, with a vast

ate livelihood could be regulated and enforced majority of licences being held communally and

without infringing the treaty right. However, al- fishing done through community-owned vessels.

7 Asper Centre Outlook 2021The Mi’kmaq Fisheries Dispute

Although these various programs increased em- application in Canadian law and provide a frame-

ployment and business opportunities, communal work for the Government of Canada’s implemen-

commercial fisheries do not encapsulate rights to tation of the Declaration.” S. 5 of Bill C-15 re-

moderate livelihood fishing. quires that Canada cooperate and consult with

Indigenous peoples in taking “all measures neces-

According to an explanatory article written sary to ensure that the laws of Canada are con-

by APTN National News, “[m]ost Mi’kmaq, and sistent with the Declaration.” S. 6(1) then goes on

Wolastoq bands in the Atlantic region signed to require that the Minister of Justice “in consul-

commercial fishing deals after the Marshall deci- tation and cooperation with Indigenous peoples

sion – but Moderate Livelihood has never been and with other federal ministers, prepare and im-

defined. A Moderate Livelihood is supposed to plement an action plan to achieve the objectives

allow a Mi’kmaw individual to make a living off of the Declaration.”

resources. As a sovereign nation on unceded ter-

ritory, the Mi’kmaq have jurisdiction and that is While the potential impact of Bill C-15 on

the basis to make their own rules for their fishery the protection of Aboriginal rights, such as the

and that is what they’re asserting right now”. Mi’kmaq right to fish commercially, is as yet un-

clear, it is possible that the direct implementation

Pending UNDRIP Implementation of UNDRIP into Canadian law may put additional

The United Nations’ 2007 adoption of the United pressure on the federal government to ensure

Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous that Aboriginal rights are upheld. This said, Bill C-

Peoples (“UNDRIP”) was the culmination of work 15 does not alter the licencing conditions, the

that began back in 1982. In 2007, only four coun- Fisheries Act or any laws related to the DFO. How-

tries voted against its adoption: Canada, the Unit- ever, it is possible that the action plan Bill C-15

ed States, Australia, and New Zealand. It was not aims to create could be used as a tool for Indige-

until 2010 that these four countries endorsed the nous communities to ensure the protection of

declaration with reservations and not until 2016 their Aboriginal and treaty rights and potentially

that Canada fully adopted the declaration without help to stimulate government action in resolving

reservation. UNDRIP “establishes a universal the current issues facing Indigenous fishers and

framework of minimum standards for the surviv- First Nations members in Nova Scotia. Until such

al, dignity and well-being of the indigenous peo- a time, the dispute will remain ongoing, and a

ples of the world and it elaborates on existing hu- continuing lack of clarity from the Canadian gov-

man rights standards and fundamental freedoms ernment will only serve to deter efforts for mean-

as they apply to the specific situation of indige- ingful reconciliation.

nous peoples.” The various individual and collec-

tive rights enumerated therein include the right

to self-determination, autonomy or self-

government, and the recognition, observance and

enforcement of treaties, agreements and other

constructive arrangements.

In December 2020, Bill C-15, United Nations Lavalee Forbes is a 2L JD student at the Faculty of Law

Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples and the Asper Centre’s Indigenous Rights working

group leader this year and Julia Nowicki is a 2L JD stu-

Act was introduced in the House of Commons,

dent at the Faculty of Law and was the Asper Centre’s

which, if passed, will affirm UNDRIP as “a univer-

work-study student this year.

sal, international, human rights instrument with

8 Asper Centre Outlook 2021Bill C-7 and MAID:

Life, Death, Liberty and Equality

by Ainslie Pierrynowski

“

This case raises many legal, ethical and mor- prohibit assistance in ending one’s life, were uncon-

al issues that touch on the very foundations stitutional. Specifically, these provisions unjustifi-

of our society, on death and on our relation- ably infringed section 7 of the Charter. The Court

ship with it.” With these words, the Superior determined that the legal prohibition on assisted

Court of Quebec captured the underlying issues at death deprived “competent adults” who seek MAID

stake in its recent decision regarding medically as- as a result of a “grievous and irremediable medical

sisted dying (MAID). In Truchon c Procureur général condition that causes enduring and intolerable

du Canada, the Superior Court of Quebec held that suffering” of their rights to liberty, life, and security

certain aspects of the Criminal Code provisions le- of the person.

galizing medically assisted dying were unconstitu-

Accordingly, in 2016, a bill legalizing medical

tional. In turn, this decision prompted the federal

assistance in dying received Royal Assent. Under

government to introduce Bill C-7, which would

the new law, an individual can only consent to

make significant amendments to the law surround-

MAID if she has “a have a grievous and irremedia-

ing MAID. What effect will Bill C-7 have? What

ble medical condition” and her natural death is

prompted this change to the law? To answer these

“reasonably foreseeable.”

questions, we must turn to the landmark Supreme

Court of Canada decision that marked a turning

Reasonably Foreseeable Natural Death

point in the debate on MAID in Canada: the 2015

case of Carter v Canada (Attorney General). Less than three years later, however, the statute

was at the centre of a consequential legal case. The

Carter and Bill C-14 applicants, Jean Truchon and Nicole Gladu, chal-

lenged the constitutionality of the requirement that

In Carter, the Supreme Court of Canada held that

one’s natural death must be reasonably foreseea-

sections 241(b) and 14 of the Criminal Code, which

ble to receive MAID. Both Mr. Trunchon and Ms.

9 Asper Centre Outlook 2021Bill C7 and MAID

Gladu had sought MAID, but their requests were another person in order to end his life. That is a

denied. Despite meeting the other statutory crite- crime in this country.” This distinction, Justice

ria, their natural deaths were not reasonably fore- Baudouin continued, has a discriminatory effect

seeable. in that “the connection established by Parliament

between the reasonably foreseeable natural

Mr. Truchon and Ms. Gladu argued before

death requirement and the vulnerability of every

the Superior Court of Quebec that this require-

disabled person betrays a paternalistic view of

ment violated their right to life, liberty, and secu-

people like the applicants. As with section 7, the

rity of the person and their right to equality, pur-

Court found that this infringement could not be

suant to section 7 and 15 of the Charter, respec-

justified under section 1 of the Charter.

tively. In September 2019, the Superior Court of

Quebec determined that the reasonably foreseea- Responding to Truchon: Bill C-7

ble natural death requirement did, indeed, unjus-

In the wake of Truchon, Bill C-7 was introduced in

tifiably infringe the applicants’ rights under sec-

the House of Commons on February 24 , 2020.

th

tions 7 and 15 of the Charter.

The bill was reintroduced on November 5 , 2020.th

Justice Christine Baudouin held that the Bill C-7 seeks to repeal the reasonably foreseea-

Carter decision, which determined that a legal ble death requirement. Removing this require-

prohibition on MAID was contrary to section 7 of ment carries a number of other legal implica-

the Charter, was general in nature and not spe- tions. For example, while Truchon did not involve

cific to those in the terminal stages of an illness or individuals with a mental illness as their sole rea-

at the end of their life. Moreover, this infringe- son for requesting MAID, removing the reasona-

ment on the applicants’ section 7 rights was con- bly foreseeable death requirement could poten-

trary to the principles of fundamental justice and tially allow people to receive MAID where mental

could not be justified under section 1 of the Char- illness is their only underlying condition. Howev-

ter. er, Bill C-7 clarifies that a mental illness alone is

not enough to qualify for MAID.

“The reasonably foreseeable Additionally, Bill C-7 provides for several

natural death requirement safeguards where one’s death is not reasonably

foreseeable. For instance, the medical practition-

discriminated against those with er or nurse practitioner providing MAID must en-

physical disabilities, contrary to sure that the person requesting MAID was

section 15 of the Charter.” “informed of the means available to relieve their

suffering, including, where appropriate, counsel-

ling services, mental health and disability support

The Court also found that the reasonably services, community services and palliative

foreseeable natural death requirement discrimi- care...”

nated against those with physical disabilities, con-

trary to section 15 of the Charter. In particular, Lastly, if an individual’s death is reasonably

Justice Baudouin noted that there exists “a dis- foreseeable, Bill C-7 would allow her to give ad-

tinction between Mr. Truchon, deprived of the vance consent to MAID. The law currently re-

choice to commit suicide due to his physical con- quires MAID recipients to have the capacity to

dition, and other persons…due to his physical dis- consent immediately before MAID is provided.

ability and the fact that his natural death is not Justice Minister David Lametti was reportedly mo-

near, Mr. Truchon must receive assistance from tivated to add this element to Bill C-7 following

10 Asper Centre Outlook 2021Bill C7 and MAID

eligibility overly broad and lacked sufficient safe-

guards.

Conversely, Luc Thériault (Bloc Québécois)

supported Bill C-7 in principle but argued that the

bill should allow people with degenerative cogni-

tive diseases to give advance consent to MAID.

Randall Garrison (New Democratic Party) likewise

contended that Bill C-7 overlooked several issues

that were meant to figure into a wider review of

prior MAID legislation, namely, cases involving

“mature minors and requests where mental illness

is the sole underlying condition, but it was not to

be limited to those topics.” While he was sup-

portive of Bill C-7, Garrison urged the Chamber “to

consider undertaking the broader review of issues

the death of Audrey Parker in 2018. Ms. Parker

around medical assistance in dying without delay.”

had cancer which had spread to her brain. She

Despite these concerns, Bill C-7 passed without

wanted to receive MAID after Christmas. Ms. Par-

the addition of a provision allowing for advance

ker, however, was worried that she would lose ca-

consent.

pacity before this point in time. As a result, she

chose to undergo MAID in November 2018. On to the Senate

Into the House of Commons The concerns expressed in the House of Commons

were echoed in the Senate’s discussion of Bill C-7.

Thus, Bill C-7 made its way into the House of Com-

For instance, the Senate Committee on Legal and

mons. After Bill C-7 passed its first reading, the

Constitutional Affairs released a pre-study report

Second Reading saw the Chamber engaged in a

regarding Bill C-7 on December 10 , 2020. While

th

passionate and consequential debate. Lametti in-

conducting the pre-study, the Committee received

troduced the bill, noting that with respect to Tru-

eighty-six written submissions and heard from

chon, “[the government] agreed that medical as-

eighty-one witnesses, including “the Ministers of

sistance in dying should be available as a means to

Justice, Health, and Employment, Workforce De-

address intolerable suffering outside of the end-of-

velopment and Disability Inclusion; regulatory au-

life context.” The Minister also noted that many in

thorities; professional organizations; advocacy

the disability community expressed concern at

groups; people living with disabilities; academics,

widening the scope of MAID eligibility, adding that

legal and medical practitioners, and experts; Indig-

the government “supports the equality of all Cana-

enous representatives; faith groups; caregivers;

dians without exception and categorically rejects

and other stakeholders.”

the notion that a life with a disability is one that is

not worth living or worse than death itself.”

The preliminary report noted that, in con-

trast to the Superior Court of Quebec’s section 15

In response, Michael Cooper (Conservative)

analysis in Truchon, several disability advocates

contended that the Attorney General of Canada

emphasized that removing the reasonably foresee-

should have appealed the Truchon decision.

able natural death requirement “would single out

Noting that MAID constituted a complex and divi-

disability in a manner that would be inconsistent

sive issue, Cooper stated that Bill C-7 made MAID

with the equality rights guaranteed by the Charter,

11 Asper Centre Outlook 2021Bill C7 and MAID

and that they anticipated a constitutional chal- people with degenerative cognitive conditions

lenge on this basis if any such amendment is like Alzheimer’s. The remaining amendments re-

passed.” Conversely, other witnesses claimed that quired the government to collect race-based data

the new procedures for receiving MAID where an on who requested MAID and to establish a com-

individual is not facing a reasonably foreseeable mittee to review Canada’s MAID regime.

natural death were overly burdensome and

The revised Bill C-7 will return to the House

marked a step backwards from the rights recog-

of Commons, where Members of Parliament will

nized in Truchon.

decide whether to accept or reject the amend-

Nonetheless, many witnesses expressed ments. While the future of Bill C-7 may be uncer-

concern that “individuals may choose MAID if tain, it is clear that the legal and ethical issues un-

there are not sufficient alternatives in palliative derlying Bill C-7 will not dissipate. As the Supreme

care or mental and physical health supports avail- Court of Canada observed in Carter:

able to them.” In particular, several witnesses

“The debate in the public arena reflects the

noted that many Canadians lack sufficient

ongoing debate in the legislative sphere. Some

healthcare services, especially people with disa-

medical practitioners see legal change as a natu-

bilities, Indigenous peoples, those living in remote

ral extension of the principle of patient autono-

areas, and racialized people. Other witnesses

my, while others fear derogation from the princi-

were concerned that repealing the reasonably

ples of medical ethics. Some people with disabili-

foreseeable natural death requirement could en-

ties oppose the legalization of assisted dying, ar-

courage “stigma and prejudice against persons

guing that it implicitly devalues their lives and

with disabilities and suggest that some lives are

renders them vulnerable to unwanted assistance

not worth living.”

in dying…Other people with disabilities take the

Accordingly, several witnesses have sug- opposite view, arguing that a regime which per-

gested alternatives to Bill C-7. These suggestions mits control over the manner of one’s death re-

range from taking more time to review current spects, rather than threatens, their autonomy and

MAID legislation, to referring the MAID regime to dignity, and that the legalization of physician-

the Supreme Court of Canada for a decision on its assisted suicide will protect them by establishing

validity. stronger safeguards and oversight for end-of-life

medical care.”

Overall, the Committee’s report revealed a

divided response to Bill C-7. With the fundamen- Indeed, regardless of the outcome in the

tal values of life, liberty, and equality hanging in Chamber, it seems that MAID will continue to ani-

the balance, this debate was poised to come to a mate significant debate for a long time to come.

head in the Senate chamber.

Passed, with Amendments

Ultimately, Bill C-7 was approved by the Senate

with several amendments. One amendment

would enable advance requests for MAID where

individuals feared losing their mental capacity.

Another amendment would place an 18-month

time limit on the provision prohibiting MAID

based on mental illness alone. A further amend- Ainslie Pierrynowski is a 2L JD student at the Fac-

ment indicated that this ban would not apply to

ulty of Law.

12 Asper Centre Outlook 2021Asper Centre Clinic Reflection

thoughtful and supportive oversight from Cheryl

Voting Age Milne, Asper Centre Clinic students completed ap-

plications for funding to support the challenge.

Students also compiled research on topics such as

Challenge Update voting and cognitive capacity, voting ages in other

countries, and voting and political theory. Finally,

students prepared a curriculum on voting in Cana-

By Sarah Nematallah da that was implemented by partner organizations

in consultations that invited youths to share their

thoughts on whether the voting age should be

I

n November of 2019, the David Asper Centre lowered.

for Constitutional Rights and Justice for Chil-

dren and Youth, in partnership with other When I joined the Asper Centre Clinic in the fall of

child rights organizations, initiated efforts to 2020, I had the opportunity to collaborate with

challenge the minimum voting age for federal elec- other Clinic students to build on this work from

tions set by the Canada Elections Act, SC 2000, c 9. the previous year in two important ways – identi-

This legislation, which allows only Canadian citi- fying non-legal experts who have written on ideas

zens over the age of 18 to vote, places a restriction that support legal arguments for lowering the

on democratic participation that is discordant with voting age; and preparing the initial drafts of

the Supreme Court’s statement in Frank v Canada pleadings.

(AG), 2019 SCC 1 that “the Charter tethers voting

rights to citizenship, and citizenship alone”. First, my Clinic colleague and I took a closer look at

experts who have conducted non-legal research

Since fall 2019, a significant amount of work on on voting ages and youth decision making. We de-

the voting age challenge has been done. With veloped a short list of experts from around the

13 Asper Centre Outlook 2021Asper Centre Clinic Reflection

world who might support the challenge, experts and from Professor Milne. The feedback I re-

from the fields of political theory, international ceived gave me useful insight into how I can im-

law, cognitive sciences, and social sciences. The prove my own drafting skills, insight that will ben-

theoretical writings, sociological studies, and sci- efit me long after I complete my studies at the

entific studies produced by these experts dispel University of Toronto’s Faculty of Law.

many of the misconceptions around youth voting

– most notably the myth that youths under the

age of 18 do not have the cognitive capacity to The experience helped me

vote, and the myth that allowing young people to

vote harms democracy by enabling uninformed

to see the tangible legal

and uninterested youths to participate in the fruits that are borne out of

democratic process. In fact, the work of these ex-

perts suggests that neither of these myths could thoughtful preparation and

be further from the truth – psychological and cog- thorough research.

nitive social science studies from the last decade

demonstrate that youths as young as 14 develop

adult-level complex reasoning skills that enable

Overall, it was an exciting time for myself and my

them to make voting decisions of the same quali-

fellow students to be working on the voting age

ty as adults, and international jurisdictions where

challenge. I personally learned a lot from being

voting ages have been lowered below 18 have

involved in the process of using preparatory re-

reported that youths are an engaged and in-

search and stakeholder consultations to build the

formed voting group and that their inclusion has

legal ingredients needed for a court challenge.

produced no negative effects on democracy.

The experience helped me to see the tangible le-

While these experts approach the issue of voting

gal fruits that are borne out of thoughtful prepa-

ages from a variety of different angles, they gen-

ration and rigorous research. It also gave me

erally align on the view that using the age of 18 as

great pleasure to be involved in something that

a proxy for democratic competency is arbitrary

has the potential to enrich Canada’s democratic

and cannot be justified by what we currently

landscape and make positive change for genera-

know about youth decision making.

tions of young Canadians to come.

Second, my team began preparing the legal docu-

ments that will be filed to initiate the challenge.

These documents incorporated a significant

amount of the research compiled by Asper Centre

students in previous terms. This task afforded me

a much appreciated opportunity to be involved in

legal teamwork, which I believe is one of the most

positive aspects of working in a clinic environ-

ment. My team members and I had the oppor-

tunity to discuss the voting age research that had

been collected and bounce ideas off each other

for how to structure arguments, thereby deepen-

ing our understanding of the issues and Canadian Sarah Nematallah is a 3L JD student at the Facul-

voting jurisprudence generally. We also received ty of Law and was an Asper Centre Clinic student

valuable feedback on our work from each other in Fall 2020.

14 Asper Centre Outlook 2021Constitutional Challenges to Canada’s

Immigration and Refugee Law Regime

By Monica Layarda, Anson Cai and Wei Yang

R

efugees and other migrants, like every- failing to rule on whether the STCA discriminates

one else in Canada, deserve to have their against women. In its submissions at trial, the re-

rights fully protected under the Canadian spondents had also advanced a s. 15 argument

Charter of Rights and Freedoms which presented the court with evidence that the

(“Charter”). Unfortunately, parts of our current US refugee system lacked sufficient protections for

immigration and refugee law regime, including women claimants with gender-persecution claims.

provisions in the Immigration and Refugee Protec- The Asper Centre, in collaboration with the

tion Act (“IRPA”) and the Safe Third Country Women’s Legal Education & Action Fund (LEAF)

Agreement (the “STCA”) between Canada and the and West Coast LEAF, had applied for leave to in-

U.S., significantly curtail their Charter rights. These tervene at the Federal Court of Appeal in support

impugned provisions arguably deny asylum- of the respondents’ cross-appeal. The team had

seekers the opportunity to obtain protection be- intended to explore the intersectionality of s. 7

fore they have a chance to make their case for rea- and s. 15 as well as argue that the court must rule

sons that often lie beyond their own control. This on an equality rights claim when Charter litigants

year, the Asper Centre’s Immigration and Refugee have expended significant resources to enforce

Law student working group provided research sup- their equality rights and the court recognizes the

port for two public interest litigation cases chal- seriousness of the constitutional question raised.

lenging the constitutionality of the STCA and IRPA, In other words, this was an inappropriate applica-

respectively. tion of judicial restraint. Unfortunately, in January

2021, the Federal Court of Appeal dismissed the

STCA Intervention at the Federal Court of Appeal joint motion (along with the applications of all oth-

Under the STCA regime, refugee claimants who er five proposed interveners—all of whom also

arrive in Canada from the U.S. by land, at a port-of sided with the respondents). Despite this disap-

-entry, are deemed ineligible to make a refugee pointing decision our working group eagerly awaits

claim in Canada and sent back to the U.S; they are the outcome of the case.

presumed to have access to a fair process in the

U.S. and vice versa. There were, however, IRPA Security Inadmissibility Provision Challenge

mounting concerns surrounding the increasingly Our second project this term concerns the security

limited protection afforded to asylum seekers in inadmissibility provisions of IRPA. The Asper Cen-

the U.S. and the documented practice of routine tre is conducting research for the legal team repre-

detention of asylum seekers. Last year, a number senting the CCR and the Canadian Association of

of individual applicants as well as three public in- Refugee Lawyers’ (“CARL”) in their Charter chal-

terest litigants including the Canadian Council for lenge against s.34(1)(f) of IRPA. Under s. 34(1),

Refugees (“CCR”), successfully challenged the con- applicants are deemed inadmissible if they are

stitutionality of the STCA at the Federal Court on found to have engaged in acts such as espionage

the grounds that the STCA infringed claimants’ s. 7 against Canadian interests, subversion against any

rights to liberty and security of the person. Since government, or terrorism. However, s. 34(1)(f) has

then, the federal government appealed this deter- a much wider scope, deeming refugee applicants

mination while the respondents cross-appealed on inadmissible if they are found to “[be] a member

the grounds that, inter alia, the trial judge erred in of an organization that there are reasonable

15 Asper Centre Outlook 2021Asper Centre Working Group Reflection

grounds to believe engages, has engaged or will da. For the first-year student researchers, these

engage” in any of the aforementioned prohibi- cases have undoubtedly presented them with an

tions. invaluable opportunity to hone their legal re-

The working group members have met search and writing skills and gain exposure to the

twice with lawyer and adjunct professor, Warda dynamics of public interest litigation early on in

Shazadi Meighen, who is part of the legal team their legal career. For the group’s co-leaders, it

representing the public interest litigants. The stu- has also been a delightful experience to work

dents researched whether the impacts of non- closely with the student researchers who, despite

deportation violate a claimant’s s. 7 rights to lib- being remote, continued to impress us with their

erty and security of the person and their s. 12 enthusiasm and impressive work product. Ulti-

right to not be subjected to cruel and unusual mately, for all of us involved, this year’s projects

treatment. Non-deportation restricts applicants’ have served as an important reminder that we

mobility rights and access to family, in addition to need to continue to work towards improving our

the psychological harm caused by being stuck in a immigration and refugee regime so that it will tru-

state of legal uncertainty and under constant ly protect the Charter rights of those who require

threat of deportation to persecution. The working it.

group’s research has included exploring refugee

inadmissibility regimes in international and for-

eign law as well as researching ss. 7 and 12 juris-

prudence. Currently, the CCR and CARL are

awaiting the Federal Court’s decision on their mo-

tion for public interest standing. Monica Layarda and Anson Cai are 2L JD students

at the Faculty of Law and the co-leaders of this

A truly rewarding experience year’s Asper Centre Immigration & Refugee Law

It has been an exciting and rewarding experience working group (along with Kiyan Jamal). Wei

for the working group to engage with on active Yang is a 1L JD student and researcher in the

Charter cases that potentially affect the lives of working group.

many refugee claimants and immigrants in Cana-

A family preparing to cross

US-Canadian border de-

spite signage warning them

no crossing is permitted

here so they can request

asylum, Roxham Road,

Champlain, NY

@ Creative Commons

16 Asper Centre Outlook 2021SCC Year in Review

The Supreme Court of Canada: Year in Review

By Annie Chan

O

ver the past year, a number of compel-

ling and significant constitutional law

cases were decided by the Supreme

Court. The following are a selection of

key decisions of particular interest.

Newfoundland and Labrador (Attorney General) v

Uashaunnuat (Innu of Uashat and of Mani-

Utenam)

This case involved a claim brought by the Innu First

Nations in response to a mining megaproject

which they allege to have been conducted on their Conseil Scolaire francophone de la Colombie-

traditional territory without their consent, depriv- Britannique v British Columbia

ing them of the use and enjoyment of their territo-

ry. The Innu filed suit in Quebec for a permanent In this case, the Supreme Court broadened the

injunction against the project, $900 million in dam- scope of protection for minority language educa-

ages and a declaration of Aboriginal title and other tion rights under s. 23 of the Charter. The Conseil

Aboriginal rights. The issue was whether the Que- scolaire francophone de la Colombie-Brittanique

bec Superior Court has jurisdiction to decide all (“CSF”), BC’s French-language school board, along

issues relating to the claim, as the traditional terri- with three parents who are s. 23 rights-holders

tories claimed by the Innu spanned both Quebec brought a claim alleging that the province’s alloca-

and Newfoundland and Labrador. In a 5-4 split, a tion of funding to the CSF was insufficient to meet

narrow majority of the SCC held that the Quebec the standards required by s. 23. Wagner, writing

court had jurisdiction over the entire claim. for the majority, clarified the “sliding scale” ap-

The Civil Code of Quebec provides that Quebec proach outlined in Mahe to determine the level of

courts have jurisdiction over a matter where the services guaranteed under s. 23. If claimants can

defendant resides in the province, except with re- identify a majority language school serving a given

spect to real actions (legal actions relating to rights number of students, the minority is prima facie

over real property). Here, the defendant mining entitled to a comparably sized homogenous lan-

companies were both headquartered in Montreal. guage school. Additionally, the level of services

Further, the majority held that Aboriginal title is a provided to children of s. 23 rights holders must be

sui generis right, not a real right. Given that Abo- substantively equivalent to that provided to the

riginal rights existed before provincial borders majority. Wagner also noted that “the fair and ra-

were imposed on Indigenous peoples, the honour tional allocation of limited public funds'' is not a

of the Crown and access to justice concerns re- pressing and substantial objective that can justify

quire flexible interpretation of jurisdictional rules s. 23 breaches under s. 1. Applying these tests, the

to allow Quebec courts to adjudicate cross-border Court found that the appellants were entitled to

s. 35 claims. eight homogenous schools that were denied by

17 Asper Centre Outlook 2021Supreme Court: Year in Review

the lower courts as well as $6 million in damages was in violation of his s.11(b) Charter right to be

for the province’s inadequate funding of school tried within a reasonable time. T was charged

transportation. The Asper Centre intervened in with second degree murder of his spouse in Au-

this appeal to address the issue of whether the gust 2012. The preliminary hearing lasted over a

Court should extend a broad qualified immunity year and the trial was ultimately scheduled for

from damages when laws are struck under s. 52 April 2017; T remained in custody throughout the

of the Constitution Act, 1982 to damages sought delay. In their 2016 judgment in R v Jordan, the

solely under s. 24(1) of the Charter. SCC established that any delay over 30 months

between when an accused is charged and the

Reference re Genetic Non-Discrimination Act completion of their trial should be presumed to

be “unreasonable”, barring a discrete exceptional

In this case, the SCC affirmed the constitutionality event. Before his trial, T brought a motion for a

of Parliament’s Genetic Non-Discrimination Act as stay of proceedings on the basis that his s. 11(b)

within the federal government’s criminal law rights had been infringed. In upholding the stay of

powers under s. 91(27) of the Constitution Act, proceedings granted by the trial judge, the Court

1867. Valid criminal law must consist of (1) a pro- noted that despite most of the delay in T’s case

hibition (2) a penalty and (3) a criminal law pur- having occurred prior to Jordan, the case would

pose. The Genetic Non-Discrimination Act estab- equally have qualified for a stay under the previ-

lishes rules relating to genetic testing, including ous R v Morin framework, as the 43-month insti-

prohibitions against forcing individuals to take or tutional delay greatly surpassed the 14 to 18

disclose genetic tests as a condition for accessing month guidelines set out in that case.

goods, services or contracts or utilizing individu-

als’ test results without their written consent. Vi- Fraser v Canada

olation of the prohibitions is punishable by fine or

imprisonment. The Court unanimously agreed This case centered on whether the RCMP’s limita-

that the Act met the prohibition and penalty re- tion on job-sharers’ abilities to buy back pension

quirements of criminal law. The Court split 5-4 as credits discriminates on the basis of sex. The

to whether the law had a valid criminal purpose. claim was brought by three retired members of

The majority itself was divided as to the pith and the RCMP who participated in the job-sharing

substance of the law as well as what the criminal program offered by the RCMP to allow them to

law purpose was. Three justices characterized the balance their work and childcare responsibilities.

law’s pith and substance as combatting genetic Like the claimants, most RCMP members enrolled

discrimination while two others contended that it in the program were women with children. How-

was protecting individuals’ control over the inti- ever, job-sharers, unlike full-time employees,

mate information revealed by genetic testing. Ac- were not allowed to "buy back” pension credits

cordingly, the majority was split in the characteri- lost due to suspension or unpaid leave. The lower

zation of the risk of harm or criminal purpose be- courts found that the pension scheme did not vio-

ing addressed by the law with options including late s. 15 as the disadvantage was due to the

protection of autonomy, privacy, equality and claimants’ “choices” to work part-time rather

public health. than their gender or family status. The majority of

the SCC overturned the lower court’s holding,

R v Thanabalasingham finding that the limitation disproportionately im-

pacts women and perpetuates their historical dis-

The issue in this appeal was whether the 43- advantage. This constituted a prima facie breach

month delay in Thanabalasingham’s criminal trial of s. 15 which could not be justified under s. 1.

18 Asper Centre Outlook 2021Supreme Court: Year in Review

This decision clarified the Court’s approach to ad- and granted an absolute discharge). G sought a

verse impact discrimination as the majority found declaration that the application of Christopher’s

that differential treatment may violate s. 15 irre- Law to persons in his situation infringes their rights

spective of whether there was discriminatory in- under ss. 7 and 15 of the Charter. The SCC held

tent, whether the protected characteristic that Christopher’s Law violated the section 15

“caused” the group to be more affected or wheth- rights of those in G’s situation and could not be

er all group members are adversely impacted. upheld under s.1. They considered the appropri-

ateness of the ONCA’s remedy of (1) suspending

Quebec (Attorney General) v 9147-0732 Quebec the declaration of invalidity for 12 months and (2)

inc exempting G from the suspension. The Asper Cen-

tre intervened in the appeal to recommend that

In this appeal, the SCC ruled that the right “not to the Court apply flexible rules for the use of sus-

be subjected to any cruel and unusual treatment pended declarations of invalidity and personal

or punishment” under Section 12 of the Charter remedies for successful individual claimants. The

extends only to human beings and not to corpora- majority accepted the Asper Centre’s recommen-

tions. 9147-0732 Quebec Inc. was a corporation dation of a “principled approach” in the determi-

convicted of doing construction work as a contrac- nation of an appropriate remedy. They upheld the

tor without a license, in violation of s. 46 of Que- remedy granted by the ONCA on the basis that it

bec’s Building Act. The Court of Quebec imposed would balance the interests of protecting public

the minimum mandatory fine of $30,843 for the safety while ensuring that G is not denied the ben-

violation. The corporation challenged the fine on efit of his successful claim.

the basis that it infringed on their s. 12 rights

against cruel and unusual punishment. The Court Annie Chan is a 1L JD student and was an Asper

unanimously denied the appeal, holding that the Centre’s work-study student in 2020-2021.

purpose of s. 12 was to safeguard human dignity

and thus does not apply to corporations.

Ontario (Attorney General) v G

The issue in this case was whether part of Ontar-

io’s sex-offender registry law (Christopher’s Law)

discriminates against individuals on the basis of

mental disability in violation of s. 15 of the Char-

ter. In 2002, G was found not criminally responsi-

ble by reason of mental disorder (NCRMD) of two

sexual offences and was subsequently given an

absolute discharge by the Ontario Review Board.

Christopher’s Law requires individuals convicted of

or found not criminally responsible of a sex

offence to register under the provincial sex offend-

er registry. Exemptions are available for individuals

found guilty, for example if they obtain a discharge

at sentencing. However, these options are unavail-

able to those in G’s situation (persons found NCR

19 Asper Centre Outlook 2021Reframing Section 15:

What Fraser v Canada means for equality litigation

By Julia Nowicki

O

n October 16th, 2020, the Supreme job-sharing as part-time work and denied those

Court of Canada released its decision who participated full-time pension credits of the

in the case of Fraser v Canada. It was ability to buy-back full-time credits--an option

a long-anticipated catalyst for equality available to members accessing other full-time

jurisprudence. The history of s.15 claims has been work relief such as LWOP or suspension which

fraught with confusion and ambiguity in the 35 leaves pension benefits unaffected.

years following the Supreme Court’s first decision Initially failing at both the Federal Court

under the equality rights provisions in the 1982 and Federal Court of Appeal, Justice Abella held

Charter of Rights and Freedoms. Since Andrews v that to deny participants pension benefits due to

Law Society of British Columbia, the test for suc- a temporary reduction in working hours through

cessfully making out a claim of discrimination in the job-share program violated s.15(1) on the ba-

relation to a law or government action has been sis of sex and was not saved by s.1.

altered numerous times. Justice Abella in writing Section 15(1) of the Charter states that

for the majority not only clarifies the Court’s cur- every individual is equal before and under the law

rent test under s.15, but likewise addresses many and has the right to the equal protections and

underlying notions that must inform judges in equal benefit of the law without discrimination

their decisions, including substantive equality, based on race, national or ethnic origin, colour,

adverse effects discrimination, and the role of religion, sec, age, or mental or physical disability.

choice in finding discrimination. While the poten- To prove that an impugned law or state action

tial impact on s.15 litigation remains to be deter- has prima facie violated s.15(1), a claimant must

mined, clarity from Canada’s highest court is be- show that the law or action (1) on its face or in its

ing heralded by scholars and litigators alike. How- impact, creates a distinction based on enumerat-

ever, the dissents’ reluctance to accept some of ed or analogous grounds, and (2) imposed bur-

the concepts put forward by the majority, which dens or denies a benefit in a manner that has the

inform Canadian law’s understanding of equality effect of reinforcing, perpetuating, or exacer-

and discrimination in society, leaves a small air of bating disadvantage.

apprehension in celebrating Fraser v Canada as a Legislation can create this distinction both

truly breakthrough case. explicitly or implicitly through its impact. In this

case, the claimants had argued that the pension

Joanne Fraser, Allison Pilgrim and Colleen consequences had an adverse impact on women

Fox are retired members of the Royal Canadian with children as they made up the majority of the

Mounted Police. While serving as police officers participants in the job-share program. This dis-

for over 25 years, the three women accessed the tinction must be based on a prohibited ground

RCMP job-sharing program in order to relieve and through its effect have a disproportionate

burdens brought on by childcare responsibilities. impact on a protected group, including through

The program involved a system of job-sharing, restrictions, criteria that may act as headwinds, or

allowing for members to split full-time duties with absence of accommodations. These impacts can

other participants as an alternative to taking be proved by either evidence about the situation

leave without pay (LWOP). The RCMP classified of the claimant group, including physical, social,

20 Asper Centre Outlook 2021You can also read