STUDENT GUIDE 2010 2010 - United Capoeira Association (UCA) A Project of the Capoeira Arts Foundation - Tucson Capoeira

←

→

Page content transcription

If your browser does not render page correctly, please read the page content below

2010 STUDENT GUIDE © 2010 - United Capoeira Association (UCA) A Project of the Capoeira Arts Foundation

Table of Contents

Welcome................................ 03 1900s Street Capoeira............. 19

Abbreviated Summary........... 05 Capoeira Regional................... 20

Levels of Development........... 06 Capoeira Angola...................... 22

Required Techniques............. 08 Present Day Capoeira.............. 23

Fundamentals & Rules........... 11 About the Music....................... 24

Capoeira Arts Foundation...... 14 Moving Through the Levels..... 32

About Capoeira....................... 15 Vocabulary Pronunciation....... 33

Origins of Capoeira................. 16 Additional Resources............... 35

Pre-Republican Capoeira........ 18 Mestre's Gallery........................ 36Welcome to Capoeira UCA.

First of all, let's thank Mestre Galo, Mestra

Suelly, and Akal for editing this work.

This brief and informal guide will give you

some insight into general aspects of capoeira, as

well as some details about our school. It is designed

to help you understand our system of training, as

well as how you can get the most benefit from

practicing capoeira. If you are a novice and do not

want to read everything at once, please read the

Summary.

Capoeira is a complex art with a rich

historical trajectory, a full and meaningful cultural

context, and contradictory interpretations. To

acquire clear and comprehensive information on

capoeira requires a significant level of responsibility

from both the school and student. In the early

seventies, levels of proficiency were established to

accommodate students with different goals and

time invested in the study of capoeira.

Consequently, students will progress through

distinct levels in terms of physical and technical

capabilities, musical skills, and theoretical

knowledge. These levels help students to measure

their own progress and to visualize attainable goals.

This guide has specific information that we require

from our novices and advanced students as well. We

encourage you to learn as much as possible from it.

We hope that it inspires you to learn more about

capoeira outside of classes and to bring your

questions to us.

During classes, we will challenge you to

extend the limits of your physical possibilities, but

without losing perspective of the traditional values,

rituals, and other aspects inherent to capoeira.

Please, feel free to voice your concerns or questions,

to any of us.

Good luck and good jogos.

03Abbreviated Summary

Capoeira is a four-century-old, African-

Brazilian art form that involves ritualized

fighting techniques, music, and practical

philosophy. It is practiced as a means of self

expression, self defense, and self growth in

Brazil, as well as in a large and growing

number of countries.

The legal name of our school is “Capoeira Arts

Foundation,” a 501 (c )(3) founded by Mestre

Acordeon* and his students in 1979. Mestre

Acordeon is a world-renowned capoeira

master who learned the art from the legendary

Mestre Bimba in Bahia, Brazil and is one of

the pioneers to bring Capoeira to North

America (1978).*

In 1992, Mestre Acordeon invited Mestre Rã

to join forces in teaching together, and both

founded the United Capoeira Association, an

umbrella for our associated schools teaching

throughout the United States. We refer to our

school in Berkeley as “UCA Capoeira –

Berkeley.” Other mestres of our association

are: Mestre Rã, currently living in Brazil;

Mestra Suelly (first American female Mestra)

in Berkeley; Mestre Calango also in Berkeley;

Mestre Galo in Denver; and Mestre Amunka

in Ukiah, CA.

Our approach to capoeira derives from the

traditional Capoeira Regional. This style of

capoeira was developed by Mestre Bimba (1889-1974), who was a very charismatic, highly respected,

and legendary Capoeira master. Mestre Bimba greatly contributed to the survival and growth of

Capoeira in the 20th century. He opened the first legal Capoeira school in Brazil and developed an

efficient method of teaching that brought respect to the practice of the art, while preserving its

authenticity and main characteristics.

Like most contemporary schools, our training system runs on annual cycles that begin and end with a

ceremony called “batizado.” During this ceremony, new students are welcomed into the school and

the work and progress of the more advanced students are acknowledged through a promotion to a

higher level. The levels are shown on the next page.

* More about Mestre Acordeon:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bira Almeida

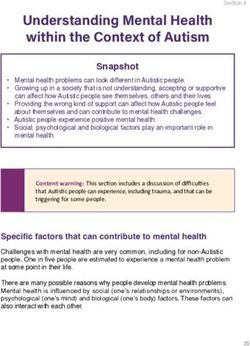

05LEVELS OF DEVELOPMENT

Comprehensive Student Program: Levels I, II, and III

This program is designed to give the student a solid foundation in capoeira in terms of physical

development, historical understanding, and knowledge of capoeira music and rituals. A capoeirista

may remain at the level of cordão azul, the highest level in the Comprehensive Student Program, as

long as he or she wishes, continuing to develope their skills, knowledge, and enjoyment of capoeira.

Level I - Calouro(a): Term for the novice student who has not participated in her first batizado. At

this level, the student has no cordão (cord or belt).

Level II - Batizado(a): is a generic term for the student who has received his first cordão and is in

one of the following sub-levels:

Cordão verde (green cord)

Cordão verde/amarelo (green/yellow cord)

Cordão amarelo (yellow cord)

Level III - Graduado(a): Term for the students who pass to a blue cord capoeirista involving the

levels of:

Cordão verde/azul (green/blue cord)

Cordão amarelo/azul (yellow/blue cord)

Cordão azul (blue cord)

Level IV - Formando(a): Term for a stage in which the students polish their knowledge and skills

and decide whether to continue their training toward becoming a UCA-endorsed teacher.

Post-graduate levels: Levels V, VI, and VII

Level V - Formado(a) refers to individuals who have completed our student program and have

successfully achieved the goals set for the formandos. They are entitled to open their own school

under supervision of our association. Their cordão is a braid of green, yellow, and blue.

Level VI - Contramestre(a) refers to a formado who has significantly contributed to the school by

teaching and assisting their Mestre in many different ways and who wishes to develop a carreer as a

capoeira teacher (mestre).

Level VII - Mestre(a) is a traditional and valued title attributed to some capoeira teachers. To

become a mestre, the capoeirista must have a long career teaching capoeira and satisfy the following

requirements:

1) Be indicated to the title by a recognized and well-known teacher;

2) Gain unanimous acceptance as such by known mestres of the art; and

3) Achieve popular recognition within the larger capoeira community.

The four different levels of Mestre are:

Cordão verde/branco (green/white cord)

Cordão amarelo/branco (yellow/white cord)

Cordão azul/branco (blue/white cord)

Cordão branco (white cord)

06Some common titles for those who teach or assist others teaching:

Monitor(a): for students at levels II and III who assist other teachers in their classes;

Instrutor(a): for students at the levels III and IV who are formally authorized to be

responsible for teaching and administrating capoeira programs;

Professor(a): for students at level V (Formado) who are teaching or who may conduct their

own capoeira schools.

Cover of little manual published in conjunction with the capoeira album recorded by

Mestre Bimba under the label J.S. Discos JLP-101, Salvador, BA.

07Required Techniques For The First Level: Cordão Verde

Old mestres used to say that capoeira had 7 movements. The rest were improvisations done in the

heat of the jogo. Today, the number of techniques in capoeira has grown substantially. Students in

one level may learn and practice techniques from more advanced levels. However, they must know

well the ones required for his or her level.

During the examination for Cordão Verde, the calouro (novice) should demonstrate the

following movements:

I - FUNDAMENTAL MOVEMENT

Ginga, including variations such as “passa pra atrás por baixo” and “por cima”

II - ATAQUES (attacks)

Usando a cabeça (using head)

Cabeçada alta (also called arpão de cabeça) and cabeçada baixa

Usando as mãos (using hands)

Asfixiante

Cutila

Galopante and galopante com giro

Palma (leque and sometimes "cutila")

Usando o cotovelo (using elbow)

Cotovelada

Godeme

Usando o joelho (using knees)

Joelhada

Usando os pés (using feet)

Armada

Benção

Martelo

Meia-lua de frente

Meia-lua de compasso

Pisão

Ponteira

Queixada

Derrubadas ou Quedas (take-downs)

Arrastão or boca de calças

Rasteira de chão

Tesoura de costas

Tesoura de frente

Vingativa

08III - DEFESAS (defensive movements)

Au aberto, au fechado, au com rolê, and au enrolado

Cocorinha de Mestre Bimba, cocorinha na ponta dos pés (on the ball of the feet)

Esquivas (escapes): defesa 1 (um), defesa 2 (dois), and defesa 3 (três)

Movimentos de Chão (floor techniques)

Escala

Negativa de ataque

Negativa de defesa (negativa de Mestre Bimba)

Ponte

Queda de Rins

Rolê Baixo

Troca de negativas

IV - MESTRE BIMBA'S SEQUÊNCIA

In addition to knowing the individual attacks and defenses, the calouro needs to be able to

demonstrate correctly with a partner the Sequência of Mestre Bimba, an important learning tool used

in Capoeira Regional.

Sequence order:

01 - Capoeirista A: Two meia-luas de frente, armada, au, and rolê

Capoeirista B: Two cocorinhas, negativa, and cabeçada

02 - Capoeirista A: Two queixadas, cocorinha, benção, au, and rolê

Capoeirista B: Two cocorinhas, armada, negativa, and cabeçada

03 - Capoeirista A: Two martelos, cocorinha, benção, au, and rolê

Capoeirista B: Two esquivas and palmas, armada, negativa, and cabeçada

04 - Capoeirista A: Two godemes, arrastão, au, and rolê

Capoeirista B: Two esquivas and palmas, galopante, negativa, and cabeçada

05 - Capoeirista A: Giro, joelhada, au, and rolê

Capoeirista B: Cabeçada alta (arpão de cabeça), negativa, and cabeçada

06 - Capoeirista A: Meia-lua de compasso, cocorinha, joelhada, au, and rolê

Capoeirista B: Cocorinha, meia-lua de compasso, negativa, and cabeçada

07 - Capoeirista A: Armada, cocorinha, benção, au, and rolê

Capoeirista B: Cocorinha, armada, negativa, and cabeçada

08 - Capoeirista A: Benção, au, and rolê

Capoeirista B: Negativa, cabeçada

09In terms of music in capoeira, the novice should be able to:

A - Identify the following berimbau rhthyms:

! 1 - São Bento Grande de Angola:!! Press dobrão on the first clap and two hits open

! 2 - Cavalaria:!! ! ! ! Open, press, open

! 3 - São Bento Grande de Regional:! Open, open, and pressed

! 4 - Banguela:!! ! ! ! Open, press, "waw" sound with the gourd

! 5 - Angola:! ! ! ! ! Open, press, do not play the third clap

B - Know how to hold the berimbau and play the instruments in a basic manner as shown in the

following chart courtesy of Contramestre Galego from Capoeira Agua de Beber:

Instruments

This is a simple description of how to play the capoeira instruments. Played repetitively in a 4/4

rhythm.

Count 1 2 3 4

Instrument

Open note Smack Open

Pandeiro

(Thumb) (Hand) (Thumb)

Agogo Low High Low

Open Bass Open

Atabaque

(Fingers) (Palm) (Fingers)

Berimbau:

Sao Bento Grande

de Angola

Berimbau:

Sao Bento Grande

de Regional

Berimbau:

Angola

Berimbau Key:

The high note produced by pressing the dobrão (rock) firmly against the arame (wire)

The low not made by striking the arame without touching the dobrão

The double buzz sound produced by holding the dobrão lightly against the arame

No note or just the caxixi (shaker) played

10Fundamental Principals of Capoeira

- Ginga is the way of the capoeirista.

- The senior mestre is in charge of the classes and rodas.

- The berimbau commands the jogos and dictates their character and speed.

- The capoeiristas exercise respect for the mestres, their partners, and themselves.

- All present observe the particular rules of the academia (physical space for the practice).

Rules and Recomendations of Our School

- As with any other form of demanding physical activity, please consult your physician before taking

up capoeira classes, and let us know if you have any special conditions that we should be aware of.

- Capoeira is a vigorous art form that helps you to expand the limits of your perceived possibilities.

You are your own judge during practice, and it is your responsibility to minimize the chances of

getting hurt.

- Bring in only personal belongings that are necessary for class. We are not responsible for lost items

left in the dressing rooms or in any other area of the school.

- Please show up 10 minutes early to class to sign in and get prepared. It is important to start on time

because the beginning of the class is the warm up and explanation of the fundamental points of the

lesson.

- If you arrive late, please warm up properly on the side and ask the teacher for permission to join

class. Likewise, if you need to leave the mat for any reason, please let your teacher know.

- Wear your clean capoeira uniform and be sure that you are free of strong personal odor. We

recommend that you train barefoot, but, if absolutely necessary, you may use a soft-soled sneaker

such as ones specialized for martial arts.

- Consistency is important for your advancement, and we highly suggest that you attend as many

classes as you can and that you participate in the various extra training opportunities and social

activities that we promote from time to time.

- You will get the most benefit from a class in which you are fully engaged. As such, you will foster

positive energy for the group as a whole.

- Always pay attention to what the teacher is saying and doing, and try every movement that you are

requested to do, even if you aren’t confident in your ability. Ask for assistance if you need it.

- A good athlete must avoid injuries and properly manage those that she or he cannot avoid. Take

proper care of any injury you may incur in order to heal faster and to keep yourself strong. By the way,

our statistics show that most of our students' injuries happen while they are involved in other

activities outside of class.

- If you are injured, let your teacher know about your condition. Most of the time, even if you are not

feeling well, you still may benefit from coming to class to observe or to play instruments and learn the

songs. At the minimum, try to follow the lyrics of the chorus and to clap your hands with the rhythm.

11- Capoeira is a vast subject with lots of information and possibilities of learning and having fun. You

may participate in our informal music classes, Portuguese practice, additional workshops, and

frequent events of our affiliated schools and of other capoeira groups. Also, in addition to our in-

house store that carries many capoeira items, you may find articles, blogs, forums, videos, and

capoeira music and lyrics on the internet. Be curious and ask questions! Take responsibility for your

own learning.

- You will notice that in the capoeira world the teachers are addressed by their rank titles before their

nicknames, such as Mestre, Mestra, Contramestre(a), or Professor(a). This treatment is part of the

traditions of the art and is good manners.

- Last but not least, pay your dues on time and help our school to keep going strong and alive. We

consider ourselves a community in which its members are involved in its maintenance and growth. So

we expect you to assume responsibilities such as mopping the floor, writing grants, decorating the

studio for a party, bringing friends, and volunteering in a broad range of activities the school may

need. Remember, this is your academia de capoeira!

- To join the students' list contact: ProfessorRecruta.uca@gmail.com or go to the address below

and click on “Join this group!” at the right top button:

http://sports.groups.yahoo.com/group/CafeCapoeiristas/

Our websites:

our schools: www.capoeira.bz.

our store: www.capoeiraarts.com

our main organization: www.capoeiraartsfoundation.org

our social project in Brazil: http://www.projetokirimure.org/

our partner in Berkeley: www.brasarte.com

12ADDITIONAL INFORMATION FOR ALL

The Capoeira Arts Foundation

Capoeira UCA is part of the Capoeira Arts Foundation (CAF). CAF was founded in 1981 under

the name of World Capoeira Association. Its founding was a visionary leap toward the establishment

of capoeira in the United States. In 2000, World Capoeira Association changed its name to Capoeira

Arts Foundation, and a long-term plan was launched to continue preserving, teaching, and

performing capoeira, as well as other arts related to African-Brazilian culture.

The goal of the Capoeira Arts Foundation is to create awareness of the depth and breadth of the

African-Brazilian experience, with its primary focus on capoeira, a rich hybrid fight-like dance, dance-

like fight, ritual, and way of life. To achieve its mission, CAF also presents artistic, social, and cultural

events that aim to strengthen the community; publishes written works; produces musical recordings

and documentary films; and is the primary supporter of Projeto Kirimurê, a project for disadvantaged

youth in the neighborhood of Itapoã, in Salvador, Bahia, Brazil. This diverse body of work attends to

and supports the human and aesthetic values of our broad community. CAF welcomes similar

organizations and individuals to participate in an ongoing dialogue of ideas and to develop

collaborative projects that challenge and bring out the best in all of us.

The acronym UCA in our logo stands for “United Capoeira Association.” UCA was born of Mestre

Acordeon's and Mestre Rã's desire to create an organization in which they could work together with

similar philosophical ideals while preserving their own identities. Mestre Rã worked with Mestre

Acordeon from 1992 to 2006, when he moved back to his school in Jundiai, São Paulo, Brazil. He is

still an active mestre of UCA, along with Mestra Suelly, Mestre Galo, Mestre Calango, and Mestre

Amunka. Today, some of their students teach capoeira in different locations under the umbrella of the

United Capoeira Association. To learn more about our associated schools, go to www.capoeira.bz.

Many teachers in today’s capoeira world have embraced the system of "groups" as the paradigm

of capoeira organizations, a strategy which has been very positive for the growth of capoeira and for

the survival of many. However, Mestre Acordeon comes from a time when the concept of group was

yet to be developed. Therefore, we are not a large “group” as understood in the capoeira context, nor

are we interested in many chapters. We strive to have a small community of students that appreciate

the collective work we try to develop with respect for all capoeira tendencies and approaches in Brazil

and abroad.

Substantial part of the Capoeira Arts Foundation revenues are dedicated to the Instituto Mestre

Acordeon in Brazil. This non-profit organization carries on the valued social Projeto Kirimurê. Our

vision regarding Projeto Kirimurê is to see young children from Itapoã, Bahia, Brazil learning about

human values, social responsibility, and environmental education in order to empower them to

choose a positive path in life and to influence their communities. We provide training tools to

complement their limited formal education. Those kids are chosen from a neighborhood with a great

number of under privileged inhabitants who suffer from lack of formal education, consequences of

drug trafficking, and family violence. Our main emphasis is on the teaching of capoeira as a tool of

personal transformation through discipline, self-knowledge, and mutual respect. We also offer other

activities such as literacy classes, homework help, psychological follow up, and field trips to cultural

events and organizations. Lastly, Projeto Kirimurê promotes an environment of beneficial cultural

exchange between capoeiristas from schools in the United States and the youth of Itapoã.

14About Capoeira

(An adapted excerpt from the article “Capoeira: An Introductory History” by Mestre Acordeon)

Since 1978, when I began teaching capoeira in the United States, the number of people

interested in this African-rooted art form has grown from a few curious individuals to a substantial

community of thousands of Americans. Valued as an expressive and enticing art from a different

cultural context, a subject of academic study, a means of physical conditioning, and a form of self-

defense, capoeira has captured the imagination and the attention of many.

Capoeira is an art form that involves movement, music, and elements of practical philosophy.

One experiences the essence of capoeira by playing a physical game called "jogo de capoeira" (game of

capoeira) or simply “jogo.” During this ritualized combat, two capoeiristas (players of capoeira)

exchange movements of attack and defense in a constant flow while observing rituals and proper

manners of the art. Both players attempt to control the space by confusing the opponent with feints

and deceptive moves. During the jogo, the capoeiristas explore their strengths and weaknesses, fears

and fatigue in a sometimes frustrating, but nevertheless enjoyable, challenging, and constant process

of personal expression, self-reflection, and growth.

The speed and character of the jogo are generally determined by the many different rhythms of

the berimbau, a one-string musical bow, which is considered to be the primary symbol of this art

form. The berimbau is complemented by the pandeiro (tambourine), atabaque (single-headed

standing drum), agogô (double bell), and reco-reco (grooved segment of bamboo scraped with a stick)

to form a unique ensemble of instruments. Inspiring solos and collective singing in a call-and-

response dialogue join the hypnotic percussion to complete the musical ambiance for the capoeira

session. The session is called "roda de capoeira," literally "capoeira wheel," or simply "roda." The term

roda, refers to the ring of participants that define the physical space for the two capoeiristas engaged

in the ritualized combat.

15Origins

Between the years of 1500 and 1888, almost four million souls crossed the Atlantic in the

disease-ridden slave ships of the Portuguese Crown. The signing of the Queiroz Law prohibiting slave

traffic in 1850 was not strong enough to empty the sails of the tumbadores (slave ships) crossing the

ocean. Many Africans were still forced to face the "middle passage" and were smuggled into Brazil.

The ethnocultural contributions of this massive forced human migration, along with those of the

native inhabitants of the colony and those of the Europeans from Portugal, shaped the people and the

culture of Brazil. It is unquestionable that from the Africans, we inherited the essential elements of

capoeira. This is evident in the aesthetics of movement and musical structure of the art, in its rituals

and philosophical principles, as well as in historical accounts of the ethnicity of those who practiced

capoeira in the past.

Three main lines of thought concerning the origins of capoeira have been introduced throughout

the times: capoeira was already formed in Africa; capoeira was created by Africans and their

descendants in the rural areas of colonial Brazil; and capoeira was created by Africans and their

descendants in one of the major Brazilian urban centers. Arguments supporting these theories have

long been discussed. It is undisputed that capoeira is an elusive "chameleonic-like" art form that has

assumed many shapes throughout its existence. Change, however, has never been able to wring out

capoeira's soul, or extirpate its formative seeds, the common denominator threading together all the

shapes capoeira has assumed. Capoeira's spirit, its innate capacity to resist pressure through a

deceptive strategy of adaptability and "non-direct" confrontation of opposing forces, is one of the

essences that exudes from its African roots.

Capoeira is not the only popular expression that derived from the same formative elements.

African in essence, these elements are present in other African-rooted art forms, such as the dances

mani from Cuba and laghya from Martinique, or in other purely African cultural expressions, such as

the ceremonial dance n'golo from Angola. In many ways, these arts resemble capoeira. However,

common structural elements that have coalesced in different geographic and cultural environments

result in different outcomes. In spite of capoeira's mutant, broad, and diffuse contours that may

obfuscate those who are not experienced enough to understand the art's complexities and

contradictions, capoeira remains a distinct and well-recognized popular cultural expression that has

been practiced in Brazil for centuries. As the venerable capoeira teacher Mestre Pastinha said:

"Capoeira is capoeira...is capoeira...is capoeira.”

Some questions related to the formative period of capoeira still remain unanswered. When, how,

and why did capoeira emerge in Brazil? From what specific cultural groups did it come, and from

which original art forms did it derive? The difficulty in answering these questions resides in a few

factors. Until the late 1970s, the scarcity of known written registers of capoeira was a big impediment

for a more comprehensive understanding of capoeira history. Another obstacle to the unveiling of

capoeira’s past is the absence of an oral tradition that reaches as far back as the pre-dawn of the art.

Fortunately, over the last decades, capoeira has been a subject of many academic studies in fields such

as history, sociology, anthropology, ethnomusicology, politics, physical education, and arts. This

growing process of investigations will bring up new lights on the origins and development of capoeira.

16Pre-Republican Capoeira

From the 1500s until 1822

Brazil was a Portuguese

colony. After a short

monarchic period of sixty-

seven years and immediately

after the official abolition of

slavery, Brazil became a

republic in 1889. This last

period was a time of

profound socio-economic

change and transformation

that shook the political

structure of the country. The

different forms of capoeira

documented through oral

tradition and written

accounts, which thrived from

the middle of the sixteenth

century through the end of

the nineteenth, are grouped

under the label Pre-Republican Capoeira. This period was an era of mystery, an era of the paintings of

Rugendas and Debret, the saga of the Quilombos dos Palmares and Zumbi, the era of extraordinary

conflict of an enslaved people and their oppressors, an era of romantic historical accounts. Nowadays,

the academic study of this period is substantial, from the maltas and malandros of Rio de Janeiro to

the capoeira steps as precursors to the frevo dance in Recife. Since then, capoeira has been a means of

self-expression, a means of connection with the ancestors, an expression of freedom, and,

encompassing all of that, a weapon of survival.

In the last days of the Brazilian Empire, conflicts between Republicans and Monarchists

occurred frequently. The streets of Rio de Janeiro were the stage of actual battles that involved a large

number of participants, including many capoeiristas. They caused a big itch to the established society

who lived in discomfort, confronting the fears of cabeçadas, martelos, club strikes, and straight razor

blades, a favorite weapon of the malandros at the time. The police records of this time listed

thousands of capoeiristas, which leads us to wonder how many mestres existed, how many personal

styles were displayed, how many movements were able to kill enemies? The physical displays of

capoeira at that time were generally called vadiação (a term with various meanings related to playing

around, doing nothing), malandragem (implied in the activity of bums, deceitfulness, street smarts,

cunning), capoeiragem, or simply, “capoeira.” Common to all manifestations of capoeira until recent

years was the constant attention the art received from the social mechanisms of repression. Capoeira

activities were a magnet for the police.

In capoeira songs and texts, you will find references to Quilombos, Zumbi, Nzinga, Princesa

Isabel, the Guarda Negra, and so on. Wikipedia contains numerous references about this historical

period.

181900s Repressed Street Capoeira

After the proclamation of the Republic of Brazil in 1889, the attempt to contain the trouble-

making activities of the capoeiristas was intensified. Indeed, the capoeiristas received specific

mention in the first Penal Code of the Republic of the United States of Brazil (Código Penal da

República dos Estados Unidos do Brasil), instituted by decree on October 11, 1890:

Art. 402. To perform on the streets or public squares the exercise of agility and corporal

dexterity known by the name, capoeiragem; to run with weapons or instruments capable of inflicting

bodily injuries, provoke turmoil, threaten certain or uncertain persons, or incite fear of bad actions;

Sentence: prison cell for two to six months (Oscar Soares 1904).

The Republican police enforcement was severe, and tales of persecution are abundant. Many

capoeiristas would run when the police squadron arrived. Others were put in jail or deported, and

some would bribe the police to let them go. Within this struggle, which lasted until the end of the

1920s, the capoeira from Bahia began to emerge, initiating its almost mythological journey to

influence the present-day shape and display of the art form. It became noticed for its soulful

characteristics: songs with noticeably African melodic lines and occasional terms from different

African dialects, playfulness, and theatrics. Perhaps, applying an unconscious strategy in a demanding

game of survival, capoeira had changed again, disguising its fierce fighting characteristics that had

been described in past written accounts.

During these troubled times, it is known that good capoeiristas hid their art far from the most

visible locations. The lore of the art is full of great fighters, such as Pedro Porreta, Chico Tres Pedaços,

and the famous Bezouro Mangangá, and a little later, Tiburcinho, Bilusca, Maré, Noronha, Americo

Pequeno, Juvenal da Cruz, Manoel Rozendo, Delfino Teles, João Clarindo, Livino Diogo, and

Francisco Sales.

Amongst those who kept capoeira alive, a giant was born in Bahia. Manuel dos Reis Machado

emerged to become venerated as the most extraordinary personality in the historical trajectory of

capoeira. He is recognized all over the world as Mestre Bimba, the creator of the Capoeira Regional.

19Capoeira Regional

Manuel dos Reis Machado

(1889-1974), nicknamed Bimba, began

to learn capoeira at the age of 10 from

an African called Bentinho who

worked as a captain for the Bahian

Company of Navigation. For many

years he honed his skills, practicing the

traditional capoeira from Bahia to

become considered one of its great

artists. In the mid 1920s he developed

his innovative style that went on to

influence the destiny of capoeira. His

work emerged in a time of complex

political and cultural circumstances.

This scenario instigated an

extraordinary amount of

interpretations regarding his motives

and methods. Unquestionably a full

plate for the scholars, Mestre Bimba

lived a simple life deeply rooted in his

ancestors' culture. Because of his

character, dignity, and wisdom, he was

considered by his peers and the

Bahians in general as one of the most

expressive and influential African-

Brazilian personalities of the time.

Early in his teaching career—

according to Bimba himself—in

reaction to the sloppiness of some of

the capoeira displayed on the streets of

Bahia, he resolved to train his students to become powerful fighters. To demonstrate the validity of

his training method, he challenged capoeiristas and fighters from other disciplines, winning these

public matches. In the early 1930s, attracted by the Mestre’s charismatic teaching, a large number of

students joined his school, helping to generate a momentum that propelled capoeira forward in terms

of general acceptance.

The growth of Mestre Bimba's style would not have been possible if he had not opened a formal

and legalized school. Prior to him, capoeira had been mainly practiced as a weekend pastime, played

in the street and informally learned on the spot. The “academia de Mestre Bimba” was officially

registered with the Office of Education, Health and Public Assistance of Bahia in 1937. This set a

precedent for greater tolerance towards the practice of other African-Brazilian popular expressions.

The school was registered under the name of Centro de Cultura Física Regional (Center of Regional

Physical Culture). Because of his school's name, which also offered a way around the legal prohibition

of capoeira, the term Capoeira Regional was reinforced and definitively established as the

denomination of Mestre Bimba's style.

20Why “Regional?”

For Mestre Bimba, “Regional” was Bahia—the immediate local universe that embodied the

“baiano” quality of his art; an implicit respect for its inherent African connections.

In reality “Bahia” is correctly called “Salvador,” the capital city of the large state of Bahia. Seated

atop hills and surrounded by sunny beaches and green valleys, Salvador has been a fortress of African

culture in Brazil, from which arises today’s capoeira. Its imaginary and mystical body has a unique

significance for its sons and daughters who simply call it “Bahia.” To be "African in Bahia" and

simultaneously "just Brazilian," especially in Mestre Bimba’s time, was naturally accepted by all

baianos, without needing to be explicitly voiced or displayed with some obviousness. It is the result of

a state of immersion in an environment in which the sacred and profane mingle, regulated by the will

of the orixás as an integral part of everyday life. “Capoeira Regional” means all that.

Mestre Bimba's approach encompassed the following: teaching in an enclosed physical space

that was conducive to a more focused practice; the introduction of a systematic training method; the

use of a specific musical ensemble of one berimbau and two pandeiros; and an emphasis placed on the

toques de berimbau (berimbau rhythms) of São Bento grande, banguela and iuna. Those rhythms

mandated jogos with specific characteristics: being more fight-oriented, more co-operative and

demonstration-like, or involving movements from the cintura desprezada, respectively. The capoeira

of Mestre Bimba had a medium-paced cadence that allowed the capoeiristas to ginga strategically

with manha, malicia, and elegance. Following the berimbau command, the capoeiristas were guided

in an intricate and dynamic display of attacks, defenses, and a tricky juke-like swing to confuse

opponents. Mestre Bimba did not include in his style some movements from the capoeira at the time

that he did not like and introduced other of his own and from batuque, a vigorous foot-sweeping

dance that he learned from his father. It was a brilliant and subtle adaptation of a traditional artform

that brought out its most fight-like capabilities inherent in the historical tradition of capoeira. Some

argue that the creation of Capoeira Regional was Mestre Bimba’s intentional response to a

nationalistic effort based in Rio de Janeiro to put forth a kind of an official Brazilian physical

education system that was based on European models.

Mestre Bimba's most important

contribution was perhaps the

revolutionary achievement of turning an

activity outlawed by the dominant elites

and on the brink of extintion into a freely

practiced popular art form that became a

prestigious and potent means of cultural

and self expression. On June 12, 1996, the

Federal University of Bahia unanimously

gave a title of Doctor Honoris Causa to

Manoel dos Reis Machado, and in 2008,

capoeira was proclamed by the Brazilian

Government as being a national treasure,

a cultural legacy of humanity.

21Capoeira Angola

The easing of repression on popular expressions during the

government of Getulio Vargas in the mid-thirties made the timing

right for Mestre Bimba's concept to be realized. Other capoeiristas

followed in his footsteps. Amorzinho, Aberrê, Antônio Maré, Daniel

Noronha, Onça Preta, and Livino Diogo all became involved in the

quest to create an organization to facilitate the practice of their

capoeira in this new stage of the art's development.

From amongst those involved in this quest, Vicente Joaquim

Ferreira Pastinha, Mestre Pastinha, distinguished himself by

founding the second capoeira association after Mestre Bimba. In his

own book Pastinha explained, "On February 23, 1941, in the

Jingibirra at the end of the neighborhod of Liberdade, this center

was born. Why? It was Vicente Ferreira Pastinha who gave the name

Centro Esportivo de Capoeira Angola [Sports Center of Capoeira

Angola]" (In Decânio, 1994: 4a).

In his pursuit of organizing his beloved capoeira, Mestre

Pastinha mobilized his students, other capoeiristas, and politically

influential friends to formally establish a permanent home for his

school. After years of struggle and long periods of inactivity, on

October 1, 1952, the Centro de Capoeira Angola was officially

installed at the Largo do Pelourinho (Pelourinho Plaza) in Salvador,

Bahia.

Mestre Pastinha was an extraordinary character – innovative, wise, and open-minded. Well-

deserved for his total commitment to capoeira, his work and wisdom, Vicente Pastinha, son of a

Spaniard and a Brazilian woman of African descent, became the primary historical point of reference

for the practitioners of today’s Capoeira Angola and for those concerned with his unique philosophical

approach to capoeira.

Capoeira Angola is characterized by a focus on rituals of the game, an emphasis on playfulness

and theatrics of the movement, and with a high degree of combat simulation. For a long time after the

turn of the twentieth century it was

predominantly an amusement on weekends

and in open plaza festivities. Nowadays, in

the broad scope of capoeira in Brazil,

Capoeira Angola has its niche, recognized as

having importance within the historical and

contemporary context of capoeira. As time

goes by, today’s Capoeira Angola gives more

conscious attention to a body language and a

gestural lexicon related to a selected aesthetic

perceived as belonging to African dance

forms and rituals.

22Present Day Capoeira

Before Mestre Bimba there were

many stylistic displays of capoeira

in all its aspects of fight, dance,

pastime, ritual, mannerisms, and

different social behaviors.

However, none of them gained

center stage as a defined approach

to capoeira.

Both Capoeira Regional and

Capoeira Angola have generated

new schools and styles based upon

interpretations of the teachings of

Mestre Bimba and Mestre

Pastinha. Some of these schools

have attempted to maintain the

characteristics of the original styles

of these great mestres, while others

have embraced both, while

developing their own

characteristics and styles.

Mestre Acordeon was a student

of Mestre Bimba, and we are

predominantely a school of

Capoeira Regional. We also

understand the need to

incorporate elements of today's

capoeira into our teaching and to

encourage our students to interact

with capoeiristas from other styles

without losing the particularities of

our game.

23About the Music

The music of capoeira has the potential to become a means for understanding the past and

present universe of the art form, as well as constructing the present reality of the capoeira that is lived

by a particular community. In this case, "capoeira community" does not refer to the social gathering

of students that naturally occurs in all schools, but to a strong body synergistically greater than the

individuals who belongs to that "particular community." The materialization of this community

should be felt as a magical presence in the terreiro in which the capoeira practice happens.

We place great emphasis on the knowledge of the instruments, their rhythmical elements, and

the performance of the capoeira music at our maximum potential. This helps to summon the soul and

energyto the rodas. There is a big distinction between some physical aspects of the music such as

speed and volume, and the "axé"— as a kind of constructive energy. Axé happens when the respect for

the music, properly tuned berimbaus, sensitive playing of the instruments, singing in the right pitch,

and concern with the maintenance of a harmonious ensemble are present.

All the multiple facets of being a capoeirista are facilitated and enhanced through the music.

These facets are to sing, to play instruments, to play capoeira, to laugh, to cry, to think, to love, to care

for our brothers and sisters, to care for our school, and to live as a full human being.

24Until the early twenties, there was not a defined composition for the instruments in capoeira

accepted by all teachers. In Mestre Bimba’s school, he used one berimbau and two pandeiros,

emphasizing the idea that the berimbau is the leader of the roda, deciding the character of the game,

its variations, and length. Therefore, one of the fundamentals of playing Capoeira Regional is to use

exclusively one berimbau and two pandeiros. We keep this tradition when we play Capoeira

Regional.

In the late sixties, a bateria with 3 berimbaus, 2 pandeiros, 1 atabaque, 1 agogô bell, and 1

reco-reco became predominant. We frequently use this bateria organizing the order of instruments as

follows (left to right as one faces it): reco-reco, pandeiro, berimbau viola (treble one), berimbau de

centro ou medio, berimbau gunga (bass one), atabaque, and agogô.

There are several ways to tune the berimbaus and to sing to them. One that is simple to do and

that makes it easier to find the right pitch is to tune the berimbau medio and the viola one step above

the gunga. In this case, the gunga plays the rhythm called Angola, the medio plays São Bento grande

de Angola in a kind of inversion in the use of the dobrão, and the viola will make variations, repicando

in a syncopated fashion and ending the rhythmical cicle with a “closed note” (when the dobrão is

pressed against the string to obtain the highest note of the instrument).

Rhythms that we play during the jogos in our school:

For the Capoeira Regional: São Bento grande, banguela, and Iuna.

For any other style: Angola, São Bento grande de Angola, São Bento pequeno, and other

variations.

25Ladainhas

The puxador (soloist) begins alone after the cry of the "Ie" which defines who will sing next. The

ladainha tells a story in the form of a lament. For some, the "ladainhas" are influenced perhaps by

Islamic prayer, and for others, by the cry of Brazilian cattle herders while travelling long distances.

Twhatever its origins, the ladainhas set up an atmosphere of anticipation and call for attentioin of all

the capoeiristas present. It is a moment of reflection and solemnity. Messages may be sent by the

singer, from the hail of a historical character to a challenge of his or her partner; from the salute to a

mestre, to the invocation of ancestral powers. Squatting beneath the berimbaus, the capoeiristas

about to play concentrate, meditate, and pray within his or her own mystical universe, psyching

themselves up to the important moment of vadiarem (an old term for the jogo de capoeira).

Canto de Entrada

When the ladainha ends, a new song style begin. It is called canto de entrada, louvação, or

sometimes chulas. It is a salute initiated by the cantador (also the soloist) or puxador and answered

by a chorus of all the presents. The puxador always will begin with the salute "Ie viva meu Deus" (Ie

longlive my God). The chorus will always respond with the same exclamation, adding at the end of the

setence the word “camará," which is a corruption of the word camarada (friend). This louvation

extends to the mestres, cities they come from, many other subjects they want to salute, as well to the

other person that the capoeirista is about to play. For instance:

Soloist: Ieh Viva Meu Mestre.

Chorus: Ieh, Viva Meu Mestre, camará.

Soloist: Ieh que me ensinou

Chorus: Ieh, que me ensinou, camará

Soloist: Ieh a capoeira

Chorus: Ieh, a capoeira, camará.

We use this song to formally end our class. It means: “Long live my teacher who taught me

capoeira, comrade.”

The last line in the canto de entrada should be “iê, volta do mundo,” which means “let’s go

around the world.” This is the signal for the jogadores (players) to begin the jogo.

Ouadras (quatrains), Corridos (free running rhymes), and Chulas

In this part is included a great variety of songs styles, from old samba de rodas, batuques,

afoxés, and other genders of folk music to contemporary songs written specifically for capoeira. That

is the moment in which the jogo is allowed to begin. It is common for the puxadores to take turns

improvising and challenging each other.

Throughout time, capoeira lyrics, the poetic voice of underprivileged people, have reflected their

unique perspective of the universe, including the simple mundane reality of daily life. This reality is

not unique to capoeira, but is reflected in many other art forms of the Afro-Brazilian diaspora. Lyrics

have been studied from socio-etnographic, socio-political, regionalistic, spiritual/religious, and

folklore perspectives. These studies began in mid 1930s, much earlier than any other academic study

of capoeira as a movement form.

26A CAPOEIRA SONG TO PRACTICE

Berimbau de Ouro

by Mestre Acordeon

Lead singers: Mestre Acordeon, Destino, andProfessor Cravo

From the CD: Cantigas de Capoeira

O meu berimbau de ouro minha mãe eu deixei no Gantoi (2x)

É um gunga bem falante que dá gosto de tocar

Eu deixei com Menininha para ela abençoá

Amanhá as sete horas, pra Bahia eu vou voltá

Vou buscar meu berimbau, que deixei no Gantoi, ha, ha!

Iê viva meu Deus!

CHORUS: EH VIVA MEU DEUS, CAMARÁ!

Ai, ai Aidê, Joga bonito que eu quero ver

CHORUS: AI, AI, AIDÊ

Joga bonito qu’eu quero aprender

Joga bonito que eu quero ver

Como vai como passou, como vai vosmicê

Angola ê, angola, angola ê, mandigueira, angola

CHORUS: ANGOLA EH, ANGOLA, ANGOLA EHMANDIGUEIRA, ANGOLA

Angola ê, angola angola ê, mandigueira, angola

Vou m’imbora pra Bahia, amanhã eu vou pra lá,

vou jogar a capoeira no Mercado Popular

Paranauê, Paranauê, Paraná

CHORUS: PARANAUÊ, PARANAUÊ, PARANÁ

Paranauê, Paranauê, Paraná

Vou m’imbora, vou m’imbora, como já disse que vou Paraná

Paranauê, Paranauê, Paraná, Paranauê, Paranauê, Paraná

Eh vim lá da Bahia pra lhe ver

Eh vim lá da Bahia pra lhe ver

Eh vim lá da Bahia pra lhe ver, pra lhe ver

CHORUS: VIM LÁ DA BAHIA PRA LHE VER

VIM LÁ DA BAHIA PRA LHE VER

VIM LÁ DA BAHIA PRA LHE VER,

PRA LHE VER, PRA LHE VER, PRA LHE VER, PRA LHE VER

Pra lhe ver, pra lhe ver, pra lhe ver, pra lhe ver, pra lhe ver (2x)

Vim lá da Bahia pra lhe ver (2x)

Vim lá da Bahia pra lhe ver, pra lhe ver, pra lhe ver, pra lhe ver, pra lhe ver

Pra lhe ver, pra lhe ver, pra lhe ver, pra lhe ver, pra lhe ver

27Vou manda lecô

CHORUS: CAJUÊ

Vou manda loiá…

O meu berimbau de ouro minha mãe, eu deixei no Gantois

O meu berimbau de ouro minha mãe, eu deixei no Gantoois

Eu saí da minha terra por ter sina viajeira

Caminhando pelo mundo, ensinando capoeira

Amanhá as sete horas p´ra Bahia vou voltar

Vou buscar meu berimbau, que deixei no Gantoi, camaradinho...

Ieh ê hora é hora...

CHORUS: IEH Ê HORA , Ê HORA, CAMARÁ...

Eh sacode a poeira, embalança, embalança, embalança, embalança

CHORUS: EH SACODE A POEIRA, EMBALANÇA, EMBALANÇA, EMBALANÇA,

EMBALANÇA.

Eh sacode a poeira, embalança, embalança, embalança, embalança

Meu berimbau é feito de berimba, uma cabaça bem maneira, Mestre Bimba quem me deu.

Entra na roda abre o peito e sai falando, toca Iuna e Banguela mostra o som que Deus lhe deu.

O meu berimbau de ouro

minha mãe, eu deixei no

Gantois

O meu berimbau de ouro

minha mãe, eu deixei no

Gantois

O sinhô amigo meu veja bem

o meu cantá

Ando muito ocupado, não sei

quando vou voltar

Pr’a buscar meu berimbau,

que deixei no Gantoi,

camaradinho

Eh da volta ao mundo

CHORUS: IE DA

VOLTA AO MUNDO,

CAMARÁ

Ai, ai, Aidê, joga bonito que

eu quero ver

CHORUS: AI, AI,

AIDÊ,

(Section of improvisation)

O meu berimbau de ouro eu

deixei no Gantois

2829

30

Moving Through the Levels of Capoeira

By Mestre Acordeon in “Capoeira: A Brazilian Art Form” by North Atlantic Books

“The career of the capoeirista begins with the batizado. From their first jogo to the point of

fully understanding the art, students will spend many years constantly training and probing

their weaknesses, facing the treacheries of life with open eyes. During this time, they will be

physically, mentally and spiritually challenged as they strive toward a well-rounded study of

the art. An isolated focus on any one of those aspects will bring limited results and shortsighted

capoeiristas.

The journey through the stages of development will be continuous with no abrupt

advances along the way. Students cannot jump from one plateau to the next but must climb

through them slowly and carefully, following a natural process that comes from dedicated

training and a feeling of well being in the art. It never should be a hasty and neurotic attempt to

progress prematurely, or a plunge into unhealthy and excessive work toward unattainable

goals. Capoeiristas, however, must fully commit themselves in every jogo, continuously striving

to play beyond falsely perceived points that we may believe to be our limits. Seemingly

limitations of knowledge, age, or even experience over opponents should not cause capoeiristas

to give up striving toward their full potential, nor should the amount of toil, occasional pains,

or previous failure discourage anyone from starting anew each jogo.

The goals one sets in Capoeira define the categories of discipulo (calouro, batizado,

formando, and formado); contramestre, and mestre. The majority of capoeiristas are disciples

who live the art as a complementary activity to the other activities in their life. They are

satisfied simply to have capoeira in their hearts and to improve the quality of their lives

through its practice.

Contramestres are capoeiristas who definitely have reached the maximum of their

physical potential, who dedicate time to internalize the philosophy of capoeira, and who have a

strong desire to pass on the tradition of the art

Mestres are those who have crossed the paths of discipulo and contramestre, who totally

open themselves to an understanding of the spiritual dimension of the art, and who are totally

committed to devote a lifetime helping others discover, enjoy and become initiated into

capoeira."

32Written words of the “Vocabulary Pronunciation”

Last track on our CD “2009 Capoeira-Bahia”

Academia Atabaque

Academia de capoeira Rum

Aula de capoeira Rumpi

Uma aula de capoeira numa academia Le

Corda Atabaque

Ou (or)cordão

Corda Agogô

Cordão

Cordões Reco reco

Cordão verde

Masculine in O Capoeira regional

Feminine A

Cantigas de capoeira

Calouro

Caloura Cantiga

Formando Puxa o côro

Formanda O puxado da cantiga

Puxar o côro

Formado

Formada Ladainha

Canto de entrada

Professor Quadras ou corridos

Professora

Professores Ladainha

Louvação

Bateria

Xaranga

Orquestra Toque de berimbau

Berimbau Regional

Verga

Madeira São Bento grande

Biriba Banguela

Iuna

Arame de aço Cavalaria

Aço Santa Maria

Amazonas

Dobrão Idalina

Pedra Hino da capoeira

Baqueta São Bento Pequeno

Vareta Samango

Caxixi Miudinho

Pandeiro São Bento grande

Couro Banguela

Platinela or xuá Iuna

33Movimentos de ataque Giro

Movimentos de ataque Giro em pé

Movimentos de defesa Escorão

Movimentos de floreio Benção

Balões

Quedas Tesoura de frente

Ritual Tesoura de costas

Rituais Cintura desprezada

Mandinga Cotuvelada, cotuvelo

Mandigar Joelhada,joelho

Mandigueiro Girar

Mandigueira Giro alto

Ginga Au enrolado

Gingar Rolê

Descer Pastinha

Desce Mestre Pastinha not pastina

Subir Mestre Canjiquinha not Canjiquina

Sobe Catarina not Catarinha

Jogue Idalina not Idalinha

Jogar capoeira

Jogue em baixo

Jogue no chão

Jogar dentro

Jogue dentro

Jogar solto

Jogue solto

Jogue seguro

Jogar seguro

Jogue duro

Armada

Meia lua

Meia lua de frente

Meia lua de compasso

Martelo

Ponteira

Queixada

Au

Cocorinha

Tesoura

Boca de calças

Arqueado

Asfixiante

Cotuvelada

Joelhada

Passa pra traz

Au chibata

Queda de rins

Crucifixo

34To learn more about capoeira history and philosophy, we recommend:

ALMEIDA, Bira (Mestre Acordeon), Capoeira: A Brazilian Art Form: History, Philsophy and

Practice; Berkeley, CA: North Atlantic Books, 1986.

ASSUNÇÃO, Mathias Rohrig, Capoeira: The History of An Afro-Brazilian Martial Art; New York,

NY: Taylor & Francis Inc, 2005.

CAPOEIRA, Nestor, Capoeira: Roots of the Dance-Fight-Game; Berkely, CA: North Atlantic Books,

2002.

On the Internet (Copy and Paste):

THE HERITAGE OF MESTRE BIMBA - AFRICAN PHILOSOPHY AND LOGIC OF CAPOEIRA

By Angelo Decânio Filho Translated to English by Shayne Mchugh

http://www.capoeira-connection.com/main/downloads/Heritage_Bimba.pdf

THE HERITAGE OF PASTINHA

By Angelo Decânio Filho Translated to English by Shayne Mchugh

http://www.capoeira-connection.com/main/downloads/Heritage_Pastinha.pdf

Berimbau Africano (Madosini Manqina)

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=z2AORnJlUdw&feature=related

Naná Vasconcelos Playing the Berimbau

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dFbd3GLVikU&feature=related

Berimbau Blues, Dinho Nascimento no PercPan 2007

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2sFkoXyNEY8&feature=related

A Capoeira Lyrics Website: Capoeira Connection

http://www.capoeira-connection.com/main/content/view/162/73/

Jogo Perigoso: Mestre Acordeon & The Capoeira Arts Café By Diallo Jeffery

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OnyLuUD8iek

Mestre Lourimbau

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qDfIdA1EjvM

35MESTRES DE CAPOEIRA: WHO ARE THEY THEY?

You can also read