Patients' Perceptions of Patient Care Providers With Tattoos and/or Body Piercings

←

→

Page content transcription

If your browser does not render page correctly, please read the page content below

Attachment NK4EOg, JONA Vol 42 Number 3 pp 160-164

JONA

Volume 42, Number 3, pp 160-164

Copyright B 2012 Wolters Kluwer Health | Lippincott Williams & Wilkins

THE JOURNAL OF NURSING ADMINISTRATION

Patients’ Perceptions of Patient Care

Providers With Tattoos and/or

Body Piercings

Heather V. Westerfield, MSN, RN, CMSRN Karen Gabel Speroni, PhD, RN

Amy B. Stafford, MSN, RN, CMSRN Marlon G. Daniel, MHA, MPH

Objective: This study evaluated patients’ percep- Conclusions: Nursing administrators should develop

tions of patient care providers with visible tattoos and/or evaluate policies regarding patient care pro-

and/or body piercings. viders with visible tattoos and/or body piercings.

Background: As tattooing and body piercing are

increasingly popular, research that informs nursing Tattooing has become increasingly popular among

administrators regarding policies on patient care all ages, occupations, and social classes.1 With the in-

providers having visible tattoos and body piercings creasing number of individuals in the workforce elect-

is warranted. ing to have tattoos and/or body piercings, hospital

Methods: A total of 150 hospitalized adult patients administrators must decide what policies to set forth

compared pictures of male and female patient care supporting a professional environment. Literature on

providers in uniform with and without tattoos and/ the perceptions of visible tattoos and body piercings

or nonearlobe body piercings. on healthcare professionals including nurses is limited

Results: Patient care providers with visible tattoos based on a search of articles dated 1988-2011, in

and/or body piercings were not perceived by patients PubMed, EBSCO host, PROQUEST, and the Cochrane

in this study as more caring, confident, reliable, at- Library using the following search terms: nurse, nurs-

tentive, cooperative, professional, efficient, or ap- ing care and body piercing, tattoo, patient satisfaction,

proachable than nontattooed or nonpierced providers. perception of care, dress code. A recent study did report

Tattooed female providers were perceived as less pro- that many hospitals had no rationale or reference

fessional than male providers with similar tattoos. supporting policies addressing body art.2 Research

Female providers with piercings were perceived as conducted in the general population on perceptions

less confident, professional, efficient, and approach- of college students with tattoos and body piercing

able than nonpierced female providers. showed that having a tattoo hindered interpersonal

perceptions.3 These perceptions included physical ap-

pearance, such as attractiveness, and personality traits,

Author Affiliations: Staff Nurse (Ms Westerfield), EducatorY such as caring. The presence of a tattoo has been re-

Professional Nursing Practice (Ms Stafford), Chair of Nursing ported to diminish image and credibility.4 Patients

Research Council (Dr Speroni), and Biostatistician (Mr Daniel),

Shore Health System, Easton, Maryland. have reported viewing facial piercing among physi-

No funding was received for this research. cians as inappropriate and negatively affecting per-

The authors declare no conflict of interest. ceived competence and trustworthiness.5

Correspondence: Mrs Westerfield, 219 South Washington St,

Easton, MD 21601 (hvw@goeaston.net). Research is warranted to evaluate patients’ per-

Supplemental digital content is available for this article. ceptions of patient care providers with visible tattoos

Direct URL citations appear in the printed text and are provided and/or body piercings. For purposes of this study,

in the HTML and PDF versions of this article on the journal’s

Web site (www.jonajournal.com). body piercing is defined as a piercing of the body any-

DOI: 10.1097/NNA.0b013e31824809d6 where other than the earlobes. Outcomes should be

160 JONA Vol. 42, No. 3 March 2012

Copyright @ 2012 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. Unauthorized reproduction of this article is prohibited.

1Attachment NK4EOg, JONA Vol 42 Number 3 pp 160-164

consent. Patients were excluded if they were in iso-

lation because of infection control, or if they had an

acute neurological or psychological deficit altering

their ability to complete the survey.

A laptop, loaded with Snap Survey version 10

(Snap Surveys, Portsmouth, New Hampshire), was

provided to patients eligible for the survey. After in-

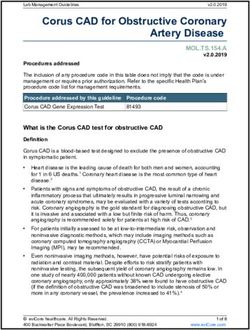

Figure 1. Definitions of descriptive words used in survey. formed consent was obtained, patients were shown

color pictures on the computer screen and were

considered by hospital administrators in the develop- asked to provide survey responses by picture type

ment or revision of policies addressing visible tattoos (See Figures, Supplemental Digital Content 1,

and/or body piercings among healthcare workers. http://links.lww.com/JONA/A70 and Supplemental

Digital Content 2, http://links.lww.com/JONA/A71).

About the Study Four sets of pictures of male and female patient care

The study purpose was to explore patients’ percep- providers dressed in uniforms (scrubs) were shown

tions of patient care providers with visible tattoos to patients via computer as follows: 1 male with a

and/or body piercings. The hypothesis of this study tattoo of the upper arm and 1 without; 1 female with

was that patients would have a lower overall per- a tattoo of the upper arm and 1 without; 1 male with

ception of patient care providers who had visible a piercing of the eyebrow and 1 without; and 1 female

tattoos and/or body piercings. A modified version of with a piercing of the nose and 1 without. For each

the nurse image scale was used.6 The modified sur- of the 4 picture sets, patients were asked to provide

vey is referred to as the Tattoo and Body Piercing survey responses via computer specifying which pa-

Patient Research Study Questionnaire. Content va- tient care provider looked the most caring, confident,

lidity was conducted on the modified version of the reliable, attentive, cooperative, professional, efficient,

instrument. Members of the Nursing Research Coun-

and approachable. Definitions of these concepts were

cil of the healthcare system where the research was

provided to patients participating in the survey

conducted evaluated the relevance and clarity of the

(Figure 1).

questionnaire. Items were retained if at least 80%

The sample size of 150 was based on an effect

agreement occurred among the members regarding

size of 0.85 to detect perceived differences by patients

the relevance and clarity of an individual item. The

of patient care provider characteristics associated

content validity index of the final survey was 1.0.

with having tattoos and body piercings, at an 80%

power and ! of .05.7 Means and frequencies were

Methods used to describe the sample and responses of the par-

This was a cross-sectional, computerized survey re- ticipants. To ascertain differences between groups

search study using computer-assisted self-interviewing (ie, age categories, gender) and response categories

on 150 patients hospitalized in a rural community (including bivariable associations), exact 2 2 methods

hospital in the mid-Atlantic region. This study re- were used. In instances of multiple comparisons,

ceived institutional review board approval. Patients Bonferroni adjustments were incorporated. Analysis

included in the study were 18 years or older and able was completed using SAS version 9.2 (SAS Institute,

to communicate in English and provide informed Cary, North Carolina).

Table 1. Respondent Perceptions of Male Patient Care Providers by Tattoo Status (n = 150)

Healthcare Provider Characteristic Male With Tattooa Male Without Tattooa No Differencea Significance Testinga

Caring 1 (0.7) 43 (28.7) 106 (70.7) G.0001

Confident 8 (5.3) 44 (29.3) 98 (65.3) G.0001

Reliable 3 (2.0) 48 (32.0) 99 (66.0) G.0001

Attentive 4 (2.7) 39 (26.0) 107 (71.3) G.0001

Cooperative 2 (1.3) 44 (29.3) 104 (69.3) G.0001

Professional 2 (1.3) 45 (30.0) 103 (68.7) G.0001

Efficient 2 (1.3) 45 (30.0) 103 (68.7) G.0001

Approachable 3 (2.0) 52 (34.7) 95 (63.3) G.0001

a

Data are reported in raw numbers and percentages (%).

JONA Vol. 42, No. 3 March 2012 161

Copyright @ 2012 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. Unauthorized reproduction of this article is prohibited.

2Attachment NK4EOg, JONA Vol 42 Number 3 pp 160-164

Table 2. Respondent Perceptions of Female Patient Care Providers by Tattoo Status (n = 150)

Healthcare Provider Female With Female Without No Significance

Characteristic Tattooa Tattooa Differencea Testinga

Caring 0 (0.0) 49 (32.7) 101 (67.3) G.0001

Confident 0 (0.0) 49 (32.7) 101 (67.3) G.0001

Reliable 0 (0.0) 53 (35.3) 97 (64.7) .0004

Attentive 1 (0.7) 52 (34.7) 97 (64.7) G.0001

Cooperative 0 (0.0) 51 (34.0) 99 (66.0) G.0001

Professional 0 (0.0) 80 (53.3) 70 (46.7) .4625

Efficient 1 (0.7) 52 (34.7) 97 (64.7) G.0001

Approachable 1 (0.7) 57 (38.0) 92 (61.3) G.0001

a

Reported in both raw numbers and percentages (%).

Findings (Table 2). Perspectives of professionalism signifi-

cantly differed between male and female providers

Of the 150 patients providing survey responses, the regarding tattoos, with patients specifying a lower

majority was female (68%, n = 102), white (77%, perception of professionalism regarding tattooed

n = 116), and 46 years or older (72%, n = 108). female providers (P G .0001). The characteristic of

Twenty-two percent responded that they had a professionalism when analyzed for patient care pro-

permanent tattoo, of which half were visible when vider by gender and tattoo status was not signifi-

clothed. Only 6% (n = 9) indicated body piercings cantly different according to patient gender.

other than the earlobe, of which 44% (n = 4) were Perceptions were less favorable regarding visible

visible when clothed. body piercings, other than the ear lobe, as compared

When patients evaluated pictures of a male pa- with visible tattoos. For male patient care providers

tient care provider dressed in uniform with and dressed in uniform with a visible body piercing, the

without visible tattoos, the majority perceived no majority of patients perceived no differences in car-

differences in caring (71%, n = 106), confidence ing (53%, n = 79), confidence (51%, n = 76), reli-

(65%, n = 98), reliability (66%, n = 99), attentiveness ability (51%, n = 76), attentiveness (50%, n = 75),

(71%, n = 107), cooperativeness (69%, n = 104), pro- cooperativeness (51%, n = 76), and efficiency (51%,

fessionalism (69%, n = 103), efficiency (69%, n = 103), n = 76) (Table 3). Of note, the male with a visible

and approachability (63% n = 95) (Table 1). The tat- body piercing was perceived to be less professional

tooed male was never perceived to be more caring, and approachable. As with the tattoo findings, the

confident, reliable, attentive, cooperative, professional, male with the body piercing was never perceived to

efficient, or approachable than his nontattooed coun- be more caring, confident, reliable, attentive, cooper-

terpart. Similar findings were demonstrated for female ative, professional, efficient, or approachable than his

patient care providers with 1 exception (Table 2). nonpierced counterpart.

Regarding perception of professionalism, the major- Participants’ perceptions were less favorable

ity viewed the female patient care provider dressed for female patient care providers dressed in uniform

in uniform without a tattoo as more professional with a visible body piercing than for their male

Table 3. Respondent Perceptions of Male Patient Care Providers by Body Piercing Status (n = 150)

Characteristic of Patient Male With Body Male Without Body No Significance

Care Provider Piercinga Piercinga Differencea Testinga

Caring 0 (0.0) 71 (47.3) 79 (52.7) .5678

Confident 1 (0.7) 73 (48.7) 76 (50.7) G.0001

Reliable 1 (0.7) 73 (48.7) 76 (50.7) G.0001

Attentive 0 (0.0) 75 (50.0) 75 (50.0) .9999

Cooperative 1 (0.7) 73 (48.7) 76 (50.7) G.0001

Professional 0 (0.0) 107 (71.3) 43 (28.7) G.0001

Efficient 0 (0.0) 74 (49.3) 76 (50.7) .9350

Approachable 0 (0.0) 83 (55.3) 67 (44.7) .2205

a

Reported in raw numbers and percentages (%)

162 JONA Vol. 42, No. 3 March 2012

Copyright @ 2012 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. Unauthorized reproduction of this article is prohibited.

3Attachment NK4EOg, JONA Vol 42 Number 3 pp 160-164

Table 4. Respondent Perceptions of Female Patient Care Providers by Body Piercing

Status (n = 150)

Characteristic of Patient Female With Body Female Without Body No Significance

Care Provider Piercinga Piercinga Differencea Testinga

Caring 0 (0.0) 73 (48.7) 77 (51.3) .8066

Confident 1 (0.7) 75 (50.0) 74 (49.3) G.0001

Reliable 0 (0.0) 75 (50.0) 75 (50.0) .9999

Attentive 0 (0.0) 72 (48.0) 78 (52.0) .6832

Cooperative 0 (0.0) 73 (48.7) 77 (51.3) .8066

Professional 0 (0.0) 105 (70.0) 45 (30.0) G.0001

Efficient 0 (0.0) 76 (50.7) 74 (49.3) .9350

Approachable 0 (0.0) 82 (54.7) 68 (45.3) .2885

a

Reported in raw scores and percentages (%)

counterparts. The majority perceived no difference 1 site and should be replicated in various care set-

for only 3 characteristics: caring (51%, n = 77), at- tings and organizations. The rural setting of the or-

tentiveness (52%, n = 78), and cooperativeness ganization in the mid-Atlantic region of the United

(51%, n= 77) (Table 4). Similarly, the visibly pierced States may have an impact on generalizability of

female provider was not perceived to be more caring, findings as well.

confident, reliable, attentive, cooperative, professional, Additional research is recommended using a

efficient, or approachable. Females without visible prospective design in which patient care providers

body piercings were considered to be more confident dressed in uniform with various visible tattoos and

(50%, n = 75), professional (70%, n = 105), efficient body piercings can be viewed in person by patients.

(51%, n = 76), and approachable (55%, n = 82) than Additional research is recommended in other hos-

pierced female patient care providers (Table 4). pital settings to negate the effect of cultural norms

on findings as well.

Discussion

Conclusions

Study results suggest male and female patient care

Results of this study suggest that male and female

providers dressed in uniform with visible tattoos

and/or nonearlobe body piercings are never per- patient care providers dressed in uniform with vis-

ceived by patients to be more caring, confident, reli- ible tattoos and/or nonearlobe body piercings are

able, attentive, cooperative, professional, efficient, not perceived by patients to be more caring, con-

or approachable than their nonYvisibly tattooed or fident, reliable, attentive, cooperative, professional,

nonpierced peers. Because of lack of literature on efficient, or approachable than their counterparts

patients’ perceptions of healthcare providers with without visible tattoos or piercings. Gender bias may

visible tattoos and body piercings, this research be a factor in regard to female providers with visible

was warranted and can be used to help guide nurs- tattoos, as patients perceived them to be less pro-

ing administrators regarding policy development fessional than their male counterpart with a similar

and/or revision. tattoo. Also, female patient care providers with vis-

A limitation to the study is that patient per- ible nonearlobe body piercings are perceived by pa-

ceptions may vary by other types of tattoo or body tients to be less confident, professional, efficient, and

piercings than those shown in the study pictures to approachable than females with no body piercings.

the study participants. Although the tattoos in this Nursing administrators should evaluate policies and

study were similar for males and females, the body practices regarding patient care providers displaying

piercings differed. To standardize perceptions, this visible tattoos and/or body piercings while providing

survey research study was electronically based, and patient care.

patients viewed pictures of patient care providers in

uniform with and without tattoos or body piercings. Acknowledgment

Patients viewing patient care providers in person The research team thanks Lois Sanger, MLS, Li-

may result in differing patient perceptions on the brarian, and also the Nursing Research Council for

characteristics evaluated in this research. An addi- their support in verifying the content validity of the

tional limitation is that the study was conducted in survey instrument.

JONA Vol. 42, No. 3 March 2012 163

Copyright @ 2012 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. Unauthorized reproduction of this article is prohibited.

4Attachment NK4EOg, JONA Vol 42 Number 3 pp 160-164

References

1. Stuppy DJ, Armstrong ML, Casals-Ariet CC. Attitudes of 4. Seiter JS, Hatch S. Effect of tattoos on perceptions of credibility

health care providers and students towards tattooed people. J and attractiveness. Psychol Rep. 2005;96:1113-1120.

Adv Nurs. 1998;27:1165-1170. 5. Newnam AW, Wright SW, Wrenn KD, Bernard A. Should phy-

2. Dorwart SD, Kuntz SW, Armstrong ML. Developing a nursing sicians have facial piercings? J Gen Intern Med. 2005;20:213-218.

personnel policy to address body art using an evidence-based 6. Skorupski VJ, Rea RE. Patients’ perceptions of today’s nursing

model. J Contin Educ Nurs. 2010;41:540-546. attire: Exploring dual images. J Nurs Adm. 2006;36:393-401.

3. Resenhoeft A, Villa J, Wiseman D. Tattoos can harm perceptions: 7. Cohen J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences.

a study and suggestions. J Am Coll Health. 2008;56:593-596. 2nd ed. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum; 1988.

164 JONA Vol. 42, No. 3 March 2012

Copyright @ 2012 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. Unauthorized reproduction of this article is prohibited.

5You can also read