The Iberian lynx LynxpardinusConservation Breeding Program

←

→

Page content transcription

If your browser does not render page correctly, please read the page content below

190 THE DEVELOPING ZOO WORLD

Int. Zoo Yb. (2008) 42: 190–198

DOI:10.1111/j.1748-1090.2007.00036.x

The Iberian lynx Lynx pardinus Conservation

Breeding Program

A. VARGAS1, I. SÁNCHEZ2, F. MARTÍNEZ1, A. RIVAS1, J. A. GODOY3, E. ROLDÁN4,

M. A. SIMÓN5, R. SERRA6, MaJ. PÉREZ7, C. ENSEÑAT8, M. DELIBES3, M. AYMERICH9,

A. SLIWA10 & U. BREITENMOSER11

1

Centro de Crı́a de Lince Ibérico El Acebuche, Parque Nacional de Doñana, Huelva, Spain,

2

Zoobotánico de Jerez, Cádiz, Spain, 3Doñana Biological Station, CSIC, Sevilla, Spain,

4

National Museum of Natural Science, CSIC, Madrid, Spain, 5Environmental Council,

Andalusian Government, Jaén, Spain, 6Investigação Veterinária Independente, Lisbon,

Portugal, 7Centro de Crı́a en Cautividad de Lince Ibérico La Olivilla, Jaen, Spain, 8Parc

Zoológic, Barcelona, Spain, 9Dirección General para la Biodiversidad, Ministerio de Medio

Ambiente, Madrid, Spain, 10Cologne Zoo, Cologne 50735, Germany, and 11IUCN Cat Specialist

Group, Institute of Veterinary Virology, University of Bern, Bern, Switzerland

E-mail: centrolinceav@oapn.mma.es

The Iberian Lynx Conservation Breeding Program fol- INTRODUCTION

lows a multidisciplinary approach, integrated within the

National Strategy for the Conservation of the Iberian

lynx, which is carried out in cooperation with national, Iberian lynx Lynx pardinus wild populations

regional and international institutions. The main goals of have undergone a constant regression through-

the ex situ conservation programme are to: (1) maintain a out the last century. The decline has been

genetically and demographically managed captive popu- especially abrupt in the last 20 years, with more

lation; (2) create new Iberian lynx Lynx pardinus free-

ranging populations through re-introduction. To achieve than an 80% reduction, mostly owing to the

the first goal, the Conservation Breeding Program aims to dramatic decline of wild rabbit Oryctolagus

maintain 85% of the genetic diversity presently found in cuniculus populations, the lynx’s prey base.

the wild for the next 30 years. This requires developing According to the last census (Guzmán et al.,

and maintaining 60–70 Iberian lynx as breeding stock.

Growth projections indicate that the ex situ programme

2002), o200 Iberian lynx (only half of them

should achieve such a population target by the year 2010. considered to be adults with reproductive po-

Once this goal is reached, re-introduction efforts could tential) survive in nature. The last two remnant

begin. Thus, current ex situ efforts focus on producing populations, Doñana and Sierra Morena, are

psychologically and physically sound captive-born indi- located in Andalusia, southern Spain. This

viduals. To achieve this goal, we use management and

research techniques that rely on multidisciplinary input dramatic population decline has brought the

and knowledge generated on species’ life history, beha- species to what is known as an ‘extinction

viour, nutrition, veterinary and health aspects, genetics, vortex’. The small size of both populations

reproductive physiology, endocrinology and ecology. makes them highly vulnerable to stochastic

Particularly important is adapting our husbandry schemes

based on research data to promote natural behaviours in

events, such as natural disasters (e.g. forest

captivity (hunting, territoriality, social interactions) and a fires, flooding), disease outbreaks, genetic and

stress-free environment that is conducive to natural demographic problems, etc., that could com-

reproduction. pletely wipe out a remnant population within a

very short period of time (Delibes et al., 2000).

Key-words: adaptive management; applied research;

conservation breeding; ex situ; genetics; husbandry; The species is listed as Critically Endangered

Iberian lynx; outreach; re-introduction; reproductive by The World Conservation Union (IUCN,

physiology; veterinary science. 2006).

Int. Zoo Yb. (2008) 42: 190–198. c 2007 The Authors. Journal compilation c 2007 The Zoological Society of LondonIBERIAN LYNX CONSERVATION BREEDING PROGRAM 191

Owing to the precarious situation of the make pairing recommendations based on

Iberian lynx in the wild, conservation mea- genetic distance between breeders, etc. One

sures need to be implemented effectively and of our goals is to minimize the use of

efficiently, integrating efforts and working potentially invasive methods while simulta-

tools (Heredia et al., 1999; MIMAM, 1999). neously enhancing the trust between the

Iberian lynx conservation could be conceived lynxes and their keepers to assist in securing

as a puzzle whose pieces should fit together information on animal body mass and gesta-

adequately. Primary efforts should be direc- tional status. Over the past 3 years, eight

ted towards in situ conservation, which in- pregnancies have resulted in the birth of 19

cludes (1) maintaining and expanding offspring, of which 11 survive to date (Vargas

remnant populations, monitoring, managing et al., 2007). While describing various orga-

prey (wild Rabbit) populations, protecting nizational aspects of the Iberian lynx Con-

and restoring habitat, promoting agreements servation Breeding Program, this paper will

with land owners, minimizing non-natural also emphasize how results from multidisci-

causes of mortality and connecting, from a plinary life-science research can be integrated

genetic standpoint, the two remnant popula- into an adaptive management approach to

tions, and (2) preparing habitat for creating help recover the world’s most threatened felid

new free-ranging populations. Another piece species.

of the puzzle is ex situ conservation, which

includes, among other activities, captive THE IBERIAN LYNX EX SITU

breeding, preparing animals for release, re-

CONSERVATION PROGRAM

search in different areas, management of a

Biological Resource Bank (BRB), genetic The Iberian Lynx Ex Situ Conservation Breed-

management of all lynx populations (wild ing Program follows a multidisciplinary ap-

and captive) as a single metapopulation, as proach, integrated within the National

well as training staff, education and outreach Strategy for the Conservation of the Iberian

efforts (Vargas, Sánchez et al., 2005). lynx, officially endorsed by the Spanish

Current Iberian lynx conservation-breed- National Commission for the Protection of

ing efforts focus on producing psychologi- Nature. National, regional and international

cally and physically sound captive-born institutions collaborate with the Program,

individuals. For this purpose, we use manage- which is currently implemented through a

ment and research techniques that rely on ‘multilateral commission’ that involves the

multidisciplinary input and knowledge, gen- central governments of Spain and Portugal,

erated on the life history of the species, together with the autonomous governments of

behaviour, nutrition, veterinary and health Andalusia, Extremadura and Castilla-La Man-

aspects, genetics, reproductive physiology, cha, Spain. Portugal, where no Iberian lynx

endocrinology and ecology. Particularly im- populations were detected during the last

portant is adapting our husbandry schemes 2002–2003 census, has developed its own ex

based on research data to promote natural situ conservation action plan, prepared in

behaviours in captivity (hunting, territoriality, coordination with the Iberian lynx captive

social interactions) and a stress-free environ- breeding committee (Serra et al., 2005; see

ment that is conducive to natural reproduc- also Vargas, 2006).

tion. Some relevant research areas include: The main goals of the Iberian Lynx Con-

determining faecal hormone profiles for adult servation Breeding Program are twofold: (1)

and subadult lynxes, studying reproductive to maintain a genetically and demographi-

behaviour and cub development, determining cally managed captive population that serves

the reproductive health of < and , breeders, as a ‘safety net’ for the species and (2) to help

developing a non-invasive pregnancy test, establish new Iberian lynx free-ranging po-

establishing sound biosecurity and biomedi- pulations through re-introduction pro-

cal protocols, genotyping all founders and grammes. Because the extraction of large

Int. Zoo Yb. (2008) 42: 190–198. c 2007 The Authors. Journal compilation c 2007 The Zoological Society of London192 THE DEVELOPING ZOO WORLD

number of lynxes from the last two remnant

populations could compromise their viability,

the most viable way to create new popula-

tions is through the re-introduction of indivi-

duals born in captivity. To achieve the latter

goal, the Conservation Breeding Program

must be integrated with in situ measures, such

as the conservation and restoration of poten-

tial Iberian lynx habitat in areas of historical

presence of the species (Andalusia, Castilla-

La Mancha, Extremadura and Portugal)

The Iberian Lynx Program encompasses

management and applied research strategies

in the following six areas.

1. Genetic and demographic management of

the captive population The best genetic man-

agement of threatened captive populations is

achieved through rapid population growth

until the established number of individuals

required to maintain genetic variability for

the species in question is reached (Lacy,

1994). Afterwards, population size should be

stabilized. In order to implement this ap-

proach, the production of new individuals

must be planned properly to meet both re-

introduction and breeding programme needs,

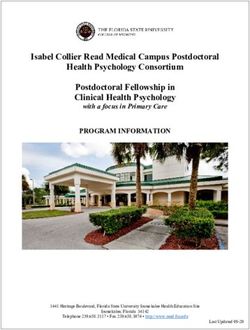

because the latter will gradually require the Plate 1. Iberian lynx Lynx pardinus , and cub which

replacement of older individuals past their are part of the Iberian Lynx Conservation Breeding

reproductive prime. Genetic and population Program in Spain. Iberian Lynx Ex Situ Conservation

management must be accompanied by proper Program, Ministry of the Environment, Madrid, and

Environmental Counsel of Andalusia (MMA-CMA).

husbandry, which involves stimulating natur-

al behaviours in captive-born individuals

from early developmental periods in order to

improve their potential for survival in the 5 year period. Wild-born founders should be

wild (Plate 1). selected from large litters (of three or more

Based on recommendations provided by siblings), because the extraction of such in-

the IUCN Conservation Breeding Specialist dividuals will have a lower impact in the wild

Group, in collaboration with the Iberian lynx population (Lacy & Vargas, 2004). The main-

in situ conservation managers, the actual tenance of genetic diversity over 30 years

situation of this species will allow for the will, therefore, require a group of 60 (30.30)

conservation of 85% of the current genetic breeding animals (comprising the original

variability for a period of 30 years (Lacy & founders plus individuals born in the Con-

Vargas, 2004; Godoy, 2006). Captive popula- servation Breeding Program). As a basic

tions that maintain o85% genetic variability strategy for maintaining genetic variability, it

are considered to be dangerously inbred. is important to achieve rapid population

In order to achieve the established genetic growth over the first 10 years of the Program,

goals, four wild-born cubs/juveniles (foun- until it reaches its ‘capacity phase’, estab-

ders) must be incorporated into the Breeding lished at 60 breeding individuals. Efforts

Program each year for 5 years consecutively. should also be made to ensure equal repre-

Thus, 20 cubs/juveniles are needed within a sentation of founders, which should all

Int. Zoo Yb. (2008) 42: 190–198. c 2007 The Authors. Journal compilation c 2007 The Zoological Society of LondonIBERIAN LYNX CONSERVATION BREEDING PROGRAM 193 provide a similar number of offspring to the Center has developed a standard operational- Program. procedures manual that details the various 2. Captive husbandry Captive husbandry is protocols that are applied to its breeding based on multidisciplinary input from a vari- population (see Vargas, Martı́nez et al., ety of animal-care fields, such as nutrition, 2005). Detailed protocols based on experi- behaviour, genetics, physiology and veterin- ences at the ‘pilot facilities’ will help smooth ary medicine, together with the systematic the way towards unified practices across ex use of the scientific method. Over the past situ lynx breeding centres as new centres two decades, a great deal of knowledge and open. experience has been gained in the manage- 3. Health and veterinary aspects The health ment of wild felids in captivity. The Associa- considerations involved in captive breeding, re- tion of Zoos and Aquariums Felid Taxon introduction and translocation programmes are a Advisory Group has compiled a Husbandry source of great concern to conservation biologists. Manual for Small Felids containing useful For instance, mycoplasmosis in Mohave desert information on, for example, health, repro- tortoises Xerobates agassizi (Jacobson, 1991), duction, nutrition and facilities (Mellen & equine encephalitis in Whooping cranes Grus Wildt, 1998). Many European zoos have americana (Dein et al., 1986), diaphragmatic broad-ranging experience in breeding wild hernias in Golden lion tamarins Leontopithecus cats in general and lynxes in particular. These rosalia (Bush et al., 1993) and herpes virus in a documents and experiences have been and large list of captive-bred avian species (Viggers continue to be a very useful reference to the et al., 1993) are just a few examples of health Iberian Lynx Captive Breeding Program problems associated with small, threatened popula- (Vargas et al., 2006). tions. There have been various cases in which One of the Program’s key husbandry chal- captive-bred animals re-introduced into the wild lenges is to strike a balance between fostering have transmitted infectious diseases to wild popu- natural behaviours in captivity (hunting, ter- lations; for example, tuberculosis in reintro- ritoriality, social interactions, etc.) and creat- duced Arabian oryx Oryx leucoryx (Viggers ing a stress-free environment where animals et al., 1993). Also, wild-caught individuals are more prone to mate. In order to obtain have occasionally infected captive populations important information about the animals with potentially lethal diseases [e.g. canine (such as their body mass or determining distemper in Black-footed ferrets Mustela ni- whether or not the ,, are pregnant), certain gripes (Williams et al., 1988)]. It is generally training techniques are being used. Some of felt that most of these conservation pro- these include obtaining regular body-mass grammes were lacking sufficient information measurements by encouraging the lynx to on: (1) disease distribution and risk in captive step onto a measuring scale. Such techniques populations; (2) disease incidence, distribution are designed to avoid using invasive meth- and risk in wild populations; (3) quarantine ods, which would stress the animals, and they systems to prevent disease transmission; (4) a also serve as a way to strengthen the bond system to track and detect pathogens ade- between the animals and their keepers. quately. The animals’ behaviour is also being care- Because relatively little is known about the fully observed by a round-the-clock video- diseases affecting lynx, actions to improve surveillance system, which provides a great our knowledge of the main diseases affecting deal of information on the species that could the species are imperative. The Iberian Lynx not be learned easily through observations in Conservation Breeding Program has a Veter- the wild. Based on the experience acquired at inary Advisory Team dedicated to diverse the ‘El Acebuche’ Center and at the Jerez aspects of veterinary and research manage- Zoo, together with information obtained from ment, as well as protocol development. To programmes established at European and tackle the understanding of the various dis- American zoos, the El Acebuche Breeding eases that potentially affect the species, the Int. Zoo Yb. (2008) 42: 190–198. c 2007 The Authors. Journal compilation c 2007 The Zoological Society of London

194 THE DEVELOPING ZOO WORLD

Program’s main lines of action involve the searched at the Institute for Zoo and Wildlife

establishment of preventive disease protocols Research in Berlin (Jewgenow et al., 2006).

for the captive populations, and research on The non-invasive techniques described above

general veterinary science (Martı́nez, 2006). provide a great deal of information, while

Projects are now under way to determine minimizing the disturbance of the animals

the incidence and prevalence of infectious under study. Assessment of reproductive

pathogens in captive and wild lynx popula- health by trans-rectal ultrasound has also been

tions (Meli et al., 2006; Millán, 2006), deter- applied to study physiological changes in <

mination of normal vs pathological blood and , Iberian lynx (F. Goeritz, unpubl. data).

values (Muñoz et al., 2006; Pastor et al., This knowledge has been essential to assess

2006) and research on potential renal disfunc- the reproductive soundness of the captive

tion (Jiménez et al., 2006). The results of population of Iberian lynx and it is regularly

research, protocol developments and standar- used to make management decisions regard-

dization efforts, coupled with dissemination ing the pairings of captive animals.

and sharing of knowledge and experience In order to assist breeding and maintaining

among veterinarians working in the pro- gene diversity, the Iberian Lynx Ex Situ

gramme, are all contributing to more consis- Program collaborates with the maintenance

tent diagnosis and treatment. For further of a Biological Resources Bank for conserva-

information, see http://www.lynxexsitu.es/ tion of biomaterial gathered from wild and

aaveterinaros/aaveterinarios.htm captive Iberian lynx populations (León et al.,

4. Reproductive physiology Reproductive 2006; Roldán et al., 2006). In order to

physiology studies and associated technolo- conserve the maximum possible genetic di-

gies increase the success rate of any captive- versity, samples of < and , gametes, as well

breeding programme and are important in as different cells or tissues, are being kept.

helping with the conservation of wild felids The conservation of gametes allows us to

in captivity. Reproductive technologies are extend future options without the limitations

available for three major purposes: (1) asses- of space, or the risk of disease transmission.

sing fertility and monitoring reproductive Also, the cryopreservation of gametes and

status; (2) assisting in breeding and mainte- embryos allows for the opportunity of

nance of gene diversity; (3) learning more prolonging the possibilities of reproduction

about reproductive mechanisms of the Criti- for individual animals after their death. The

cally Endangered Iberian lynx. preservation of somatic cells (or undifferen-

An important outcome of Iberian lynx tiated germ cells) could give individuals who

reproductive physiology studies is the devel- have died before reaching sexual maturity a

opment of non-invasive techniques that aid in reproductive opportunity, or extend the repro-

captive population management. Over the ductive potential of other individuals.

past 2 years, work carried out to define Iberian The Iberian lynx BRB is presently being

lynx < and , hormonal profiles has helped us maintained at two locations: the National

gain a clearer perspective on the length of Museum of Natural Sciences in Madrid

breeding periods, and the potential use of (Roldán et al., 2006) and the Miguel Hernán-

hormonal metabolites in faeces as a non- dez University in Elche, Alicante (León et al.,

invasive gestation predictor (Jewgenow 2006). Although the Museum of Natural

et al., 2006; Pelican et al., 2006; see also Sciences specializes principally in reproductive

Schwarzenberger, 2007). While faecal hor- samples and the University MH specializes in

mones do not seem to be the best diagnostic multi-potential somatic cells, both banks pre-

tool, they have proven to be extremely useful serve tissue, blood, serum and other biological

to understand better the year-round reproduc- materials. The storage of these samples means

tive activity of < and , Iberian lynx. Another that materials will be available for future

gestation diagnostic technique, based on ana- analysis whenever needed, which is a valuable

lyses of relaxin in urine, is now being re- resource for potential retrospective studies.

Int. Zoo Yb. (2008) 42: 190–198. c 2007 The Authors. Journal compilation c 2007 The Zoological Society of LondonIBERIAN LYNX CONSERVATION BREEDING PROGRAM 195

5. Re-introduction As mentioned above, joyed by conservation-breeding programmes

the two current small populations of free- is their ability to gain public attention, parti-

ranging Iberian lynxes are highly vulnerable. cularly if the animal in question is charismatic

Thus, it is imperative to create, as soon as and attractive to the broader public. The

possible, new wild populations (while simul- Iberian lynx is one such case and raising

taneously increasing numbers in the existing public awareness of the need for habitat

ones). conservation to guarantee survival of the

Before any re-introduction/translocation, a species in the wild is one of the Program’s

detailed viability study is required (see IUCN primary objectives. It is important to empha-

Guidelines for Re-introductions: IUCN, size that breeding and keeping lynxes in

1998). It is important to determine whether captivity, with no hope of ever returning them

the cause or causes that brought the species to to the wild or of recovering the natural

extinction in the specific area have been population, would be a pointless exercise.

eradicated and, if so, whether there is admin- The breeding programme encourages, coop-

istrative and local population support for the erates with and supports media interest in the

Program and whether the habitat is prepared Iberian lynx, while taking every opportunity

to support a viable population of the species. to remind the public of the primary impor-

All re-introductions and translocations must tance of in situ conservation work.

be performed using scientific support and We also share on-line information on the

the Iberian lynx should be no exception Iberian lynx web page (http://www.lynxexsitu.

(Palomares, 2006). Such conservation techni- es), featuring monthly newsletters, pictures and

ques require an interdisciplinary approach, videos of all ‘captive’ lynxes, along with

with input from experts in ecology, veterinary general interest and scientific articles, and

medicine, physiology and behavioural scien- descriptions of the Center’s protocols and

ces, as well as support from socio-political working methods. An English-language ver-

and information sciences. All stages of pro- sion is currently in production, to further

gramme development and implementation expand the scope of communication and

must have well-defined protocols that docu- awareness efforts. The Web page also contains

ment the objectives, methodology, responsi- an area only accessible to managers, research-

bilities, as well as the accountability of the ers and technical personnel working directly

organizations and individuals involved. with the Program, for restricted database access

The greater the number of captive-bred and other information exchange. As part of its

lynxes produced and trained to maximize their training efforts, the Acebuche Center Breeding

potential for post-release survival, the lower Program organizes on-site internships for re-

the number of wild lynxes that must be cap- cent college graduates interested in acquiring

tured to establish new populations, or to re- first-hand knowledge within an endangered

inforce the existing ones (Simón & Cadenas, species conservation programme.

2006). Re-introduction and translocation each

pose advantages and disadvantages. A com-

CONCLUSION

parative study is required to determine which

option, or combination of options, is most Besides offering an insurance against extinc-

appropriate for the conservation of the Iberian tion, the Iberian Lynx Conservation Breeding

lynx. Program emphasizes how results from multi-

6. Communication, awareness and training disciplinary life-science research can be

Awareness, education and scientific training integrated into an adaptive management ap-

are essential to all conservation-breeding pro- proach to help recover the world’s most

grammes. Education and awareness efforts threatened felid species. The ultimate goal of

should be focused on changing prevalent the ex situ Program is to offer sound support

attitudes that contribute to habitat destruction to in situ conservation efforts by providing

and species extinction. One advantage en- healthy Iberian lynx for future re-introduction

Int. Zoo Yb. (2008) 42: 190–198. c 2007 The Authors. Journal compilation c 2007 The Zoological Society of London196 THE DEVELOPING ZOO WORLD

projects. In addition, the Program carries out ings: 59–60. Sevilla: Fundación Biodiversidad; Madrid:

Ministerio de Medio Ambiente. http://www.lynxexsitu.es/

a communication plan aimed at preparing documentos/comunicacion/simposios/cursoexsitu06/Iberian

professionals for working with threatened- %20Lynx%20Ex-situ%20Conservation.pdf

species conservation as well as sensitizing GUZMÁN, N., GARCÍA, F., GARROTE, G., PÉREZ DE AYALA,

the general public and decision-makers about R. & IGLESIAS, M. (2002): El lince ibérico (Lynx pardinus)

the importance of conserving habitat for the en España y Portugal. Censo-diagnóstico de sus pobla-

ciones. Dirección General para la Biodiversidad, Madrid.

recovery of this charismatic felid. An effec- HEREDIA, B., GAONA, P., VARGAS, A., SEAL, U. & ELLIS, S.

tive recovery of the Iberian lynx in nature will (Eds) (1999): Taller sobre la viabilidad de las pobla-

help protect large areas of Mediterranean ciones de lince Ibérico (Lynx pardinus). Apple Valley,

forests and scrubland, thus benefiting a wide MN: IUCN SSC Conservation Breeding Specialist

variety of species that thrive on this unique Group; Madrid: MIMAM. http://lynx.uio.no/lynx/ibe

lynxco/20_il-compendium/home/index_es.htm

and important ecosystem. IUCN (1998): IUCN guidelines for re-introductions.

Gland and Cambridge: IUCN/SSC Re-introduction Spe-

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS cialist Group. http://www.iucn.org/themes/ssc/publica

The authors would like to thank all the institutions (and tions/policy/reinte.htm

associated staff) that presently collaborate in the Iberian IUCN (2006): 2006 IUCN red list of threatened species.

Lynx Conservation Breeding Program, including the Gland and Cambridge: IUCN. http://www.iucnredlist.

Spanish Ministry of the Environment, the governments org/

of Andalusia, Extremadura, Castilla-La Mancha and JACOBSON, S. (1991): Evaluation model for developing,

Portugal, the Life-Nature Project for Iberian Lynx Con- implementing and assessing conservation education pro-

servation in Andalusia, the International Union for the grams: examples from Belize and Costa Rica. Environ-

Conservation of Nature (Cat Specialist Group and Con- mental Management 15: 143–150.

servation Breeding Specialist Group), the National Scien- JEWGENOW, K., DEHNHARD, M., FRANK, A., NAIDENKO, S.,

tific Research Council (Doñana Biological Station, the VARGAS, A. & GÖRITZ, F. (2006): A comparative analysis

National Museum of Natural Sciences, and Almeria Arid of the reproduction of the Eurasian and the Iberian

Zones Station), the Seville Diagnostic Analysis Center, lynx in captivity. In Iberian lynx ex-situ conservation

the Autonomous University of Barcelona, the Miguel seminar series book of proceedings: 116–117. Sevilla:

Hernández University, the Complutense University of Fundación Biodiversidad; Madrid: Ministerio de Medio

Madrid, the University of Huelva, the University of Ambiente. http://www.lynxexsitu.es/documentos/comu

Cordoba, the University of Zurich – Vet Clinical Labora- nicacion/simposios/cursoexsitu06/Iberian%20Lynx%20

tory (Switzerland), the Institute for Zoo and Wildlife Ex-situ%20Conservation.pdf

Research, Berlin (Germany), the Smithsonian Institution JIMÉNEZ, M. A., SÁNCHEZ, B., GARCÍA, P., PÉREZ, M.,

(USA), the Jerez Zoo, the Terra Natura Foundation, the CARRILLO, M. E., MORENO, F. J. & PEÑA, L. (2006):

Fuengirola Zoo, the Barcelona Zoo, the European Asso- Pathology of the Iberian Lynx. In Iberian lynx ex-situ

ciation of Zoos and Aquariums, the Iberian Association conservation seminar series book of proceedings: 22–27.

of Zoos and Aquariums, the International Society for Sevilla: Fundación Biodiversidad; Madrid: Ministerio de

Endangered Cats, PolePosition, The BBVA Foundation, Medio Ambiente. http://www.lynxexsitu.es/documentos/

the Andalusian School of Biologists and the SEO/Bird- comunicacion/simposios/cursoexsitu06/Iberian%20Lynx%

life and Doñana National Park volunteer programmes. 20Ex-situ%20Conservation.pdf

LACY, R. (1994): Managing genetic diversity in captive

REFERENCES populations of animals. In Restoration of endangered

BUSH, M., BECK, B. B. & MONTALI, R. J. (1993): Medical species: 63–83. Bowles, M. L. & Whelan, C. J. (Eds).

considerations of reintroductions. In Zoo and wild animal Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

medicine: current therapy: 24–26. Fowler, M. E. (Ed.). LACY, R. & VARGAS, A. (2004): Informe sobre la gestión

Philadelphia, PA: W. B. Saunders. Genética y Demográfica del Programa de crı́a para

DEIN, F. J., CARPENTER, J. W., CLARK, G. G., MONTALI, R. la Conservación del Lince Ibérico: Escenarios,

J., CRABBS, C. L., TSAI, T. F. & DOCHERTY, D. E. (1986): Conclusiones y Recomendaciones. Apple Valley, MN:

Mortality of captive whooping cranes caused by eastern CBSG; Madrid: Ministerio de Medio Ambiente

equine encephalitis virus. Journal of American Veterin- http://www.lynxexsitu.es/genetica/documentos_genetica.

ary Medicine Association 189: 1006–1010. htm

DELIBES, M., RODRIGUEZ, A. & FERRERAS, P. (Eds) (2000): LEÓN, T., JONES, J. & SORIA, B. (2006): Iberian lynx cell

Action plan for the conservation of the Iberian lynx bank: biological reserves and their application to the

(Lynx pardinus) in Europe/Plan de Acción para la conservation of the species. In Iberian lynx ex-situ

Conservación del Lince Ibérico en Europa. Madrid, conservation seminar series book of proceedings: 106–

Spain: WWF International and Council of Europe. 108. Sevilla: Fundación Biodiversidad; Madrid: Minis-

GODOY, J. A. (2006): Iberian lynx population genetics: terio de Medio Ambiente. http://www.lynxexsitu.es/doc

Doñana, Sierra Morena, and ex-situ program. In Iberian umentos/comunicacion/simposios/cursoexsitu06/Iberian%

lynx ex-situ conservation seminar series book of proceed- 20Lynx%20Ex-situ%20Conservation.pdf

Int. Zoo Yb. (2008) 42: 190–198. c 2007 The Authors. Journal compilation c 2007 The Zoological Society of LondonIBERIAN LYNX CONSERVATION BREEDING PROGRAM 197 MARTÍNEZ, F. (2006): Iberian lynx health program. In PELICAN, K., ABÁIGAR, T., VARGAS, A., RODRIGUEZ, J. M., Iberian lynx ex-situ conservation seminar series book of BERGARA, J., RIVAS, A., MARTÍNEZ, F., RODRIGUEZ, D., proceedings: 14–15. Sevilla: Fundación Biodiversidad; BROWN, J. & WILDT, D. (2006): Hormone profiles in the Madrid: Ministerio de Medio Ambiente. http://www. Iberian lynx and applications to in-situ and ex-situ lynxexsitu.es/documentos/comunicacion/simposios/curso conservation. In Iberian lynx ex-situ conservation semi- exsitu06/Iberian%20Lynx%20Ex-situ%20Conservation.pdf nar series book of proceedings: 113–115. Sevilla: Funda- MELI, M., WILLI, B., RYSER, M., VARGAS, A., MARTÍNEZ, ción Biodiversidad; Madrid: Ministerio de Medio F., BOYER, C., BAY, G., CATTORI, V., HOFFMAN, R. & LUTZ, Ambiente. http://www.lynxexsitu.es/documentos/comu H. (2006): Prevalence of selected pathogens in the nicacion/simposios/cursoexsitu06/Iberian%20Lynx%20 Eurasian and Iberian lynx. In Iberian lynx ex-situ con- Ex-situ%20Conservation.pdf servation seminar series book of proceedings: 28–32. ROLDÁN, E., GAÑÁN, N., CRESPO, C., GONZÁLEZ, R., Sevilla: Fundación Biodiversidad; Madrid: Ministerio de ARREGUI, L., DEL OLMO, A., GARDE, J. & GOMENDIO, M. Medio Ambiente. http://www.lynxexsitu.es/documentos/ (2006): A genetic resource bank and development of comunicacion/simposios/cursoexsitu06/Iberian%20Lynx assisted reproductive technologies for the Iberian lynx. In %20Ex-situ%20Conservation.pdf Iberian lynx ex-situ conservation seminar series book of MELLEN, J. D. & WILDT, D. E. (Eds) (1998): Husbandry proceedings: 101–105. Sevilla: Fundación Biodiversi- manual for small felids. Lake Buena Vista, FL: Disney’s dad; Madrid: Ministerio de Medio Ambiente. http:// Animal Kingdom, in association with the American www.lynxexsitu.es/documentos/comunicacion/simposios/ Zoo and Aquarium Association Felid Taxon Advisory cursoexsitu06/Iberian%20Lynx%20Ex-situ%20Conserva Group. http://www.felidtag.org/pages/Reports/Husbandry% tion.pdf 20Manual%20for%20Small%201998/husbandry.htm SCHWARZENBERGER, F. (2007): The many uses of non- MILLÁN, J. (2006): Pathogens and pollutants in wild and invasive faecal steroid monitoring in zoo and wildlife domestic animals in Iberian lynx distribution areas in species. International Zoo Yearbook 41: 52–74. Spain. In Iberian lynx ex-situ conservation seminar series SERRA, E., SARMENTO, P., BAETA, R., SIMÃO, C. & ABREU, book of proceedings: 33–35. Sevilla: Fundación T. (2005): Portuguese Iberian lynx ex situ conservation Biodiversidad; Madrid: Ministerio de Medio Ambiente. action plan. Lisbon: Instituto da Conservação da Natur- http://www.lynxexsitu.es/documentos/comunicacion/simpo eza, Investigação Veterinária Independente, Reserva Nat- sios/cursoexsitu06/Iberian%20Lynx%20Ex-situ%20Conser ural da Serra da Malcata. Available from the Iberian Lynx vation.pdf Compendium at http://lynx.uio.no/lynx/ibelynxco/20_il; MIMAM (1999): Estrategia Nacional para la conserva- compendium/home/index_es.htm ción de lince ibérico. Madrid: Dirección General para la SIMÓN, M. A. & CADENAS, R. (2006): Life-Nature Project Conservación de la Naturaleza, Ministerio de Medio (LIFE 06/NAT/E/209) for the reintroduction of the Ambiente. http://lynx.uio.no/lynx/ibelynxco/20_il-com Iberian lynx in Andalusia. In Iberian lynx ex-situ con- pendium/home/index_es.htm servation seminar series book of proceedings: 144–150. MUÑOZ, A., GARCÍA, I. & RODRÍGUEZ, E. (2006): Biochem- Sevilla: Fundación Biodiversidad; Madrid: Ministerio de istry reference values for Iberian Lynx (Lynx pardinus). Medio Ambiente. http://www.lynxexsitu.es/documentos/ In Iberian lynx ex-situ conservation seminar series book comunicacion/simposios/cursoexsitu06/Iberian%20Lynx of proceedings: 19–21. Sevilla: Fundación Biodiversi- %20Ex-situ%20Conservation.pdf dad; Madrid: Ministerio de Medio Ambiente. http:// VARGAS, A. (2006): Introduction to the Iberian lynx www.lynxexsitu.es/documentos/comunicacion/simposios/ seminar series: overview of the various disciplines in- cursoexsitu06/Iberian%20Lynx%20Ex-situ%20Conserva volved in the Ex-situ Conservation Program/Aspectos tion.pdf Generales de Todas las Disciplinas que Integran el PALOMARES, F. (2006): Scientific planning for the translo- Programa de Conservación Ex-situ del Lince Ibérico. In cation of Iberian lynx in Doñana’s National Park. In Iberian lynx ex-situ conservation seminar series book of Iberian lynx ex-situ conservation seminar series book of proceedings: 5–11 [English], 154–161 [Spanish]. Sevil- proceedings: 134. Sevilla: Fundación Biodiversidad; la: Fundación Biodiversidad; Madrid: Ministerio de Madrid: Ministerio de Medio Ambiente. http://www. Medio Ambiente. http://www.lynxexsitu.es/documentos/ lynxexsitu.es/documentos/comunicacion/simposios/cur comunicacion/simposios/cursoexsitu06/Iberian%20Lynx soexsitu06/Iberian%20Lynx%20Ex-situ%20Conservation. %20Ex-situ%20Conservation.pdf pdf VARGAS, A., MARTÍNEZ, F., BERGARA, J., KLINK, L. D., PASTOR, J., BACH-RAICH, E., MESALLES, M., CUENCA, R. & RODRÍGUEZ, J. M., RODRIGUEZ, D. & RIVAS, A. (Compilers) LAVIN, S. (2006): Hematological reference values and (2005): Manual de manejo del Lince Ibérico en Cautivi- critical difference of selected parameters for the Iberian dad. Programa de Funcionamiento del centro de crı́a, El lynx using a flow cytometer laser analyzer (Advia 120). Acebuche, Parque Nacional Doñana. Huelva, Spain: El In Iberian lynx ex-situ conservation seminar series book Acebuche Breeding Center. http://www.lynxexsitu.es/ of proceedings: 16–17. Sevilla: Fundación Biodiversi- documentos/manejo/PFCC.pdf dad; Madrid: Ministerio de Medio Ambiente. http:// VARGAS, A., SÁNCHEZ, I., GODOY, J., ROLDÁN, E., MARTI- www.lynxexsitu.es/documentos/comunicacion/simposios/ NEZ, F. & SIMÓN, M. A. (Eds) (2005): Plan de Acción para cursoexsitu06/Iberian%20Lynx%20Ex-situ%20Conserva la crı́a en cautividad del lince ibérico: Tercera edición. tion.pdf Madrid: Ministerio de Medio Ambiente; Andalucı́a; Int. Zoo Yb. (2008) 42: 190–198. c 2007 The Authors. Journal compilation c 2007 The Zoological Society of London

198 THE DEVELOPING ZOO WORLD

Consejerı́a d e Medio Ambiente de la Junta de Andalucı́a. SÁNCHEZ, I. (2007): Update on the Iberian Lynx

www.lynxexsitu.es/documentos/pexsitu/plan Conservation Breeding Programme. Cat News 46:

_de_accion.pdf 40.

VARGAS, A., MARTÍNEZ, F., KLINK, L. D., BERGARA, J., VIGGERS, K. L., LINDENAMAYER, D. B. & SPRATT, D. M.

RIVAS, A., RODRÍGUEZ, J. M., RODRIGUEZ, D., VÁZQUEZ, A. (1993): The importance of disease in reintroduction

& SÁNCHEZ, I. (2006): Manejo del Lince Ibérico en programmes. Wildlife Research 20: 687–698.

Cautividad/Husbandry of the Iberian lynx in captivity. WILLIAMS, E. S., THORNE, E. T., APPEL, M. J. & BELITSKY,

In Conservación Ex-situ del Lince Ibérico: 19–31. Sevil- D. W. (1988): Canine distemper in black-footed ferrets

la: Fundación Biodiversidad. http://www.lynxexsitu. (Mustela nigripes) from Wyoming. Journal of Wildlife

es/documentos/comunicacion/simposios/cursoexsitu06/2- Diseases 24: 385–398.

Genetics-Husbandry.pdf

VARGAS, A., MARTÍNEZ, F., RIVAS, A., BERGARA, J., VÁZ- Manuscript submitted 18 June 2007; revised

QUEZ, A., RODRÍGUEZ, J. M., VÁZQUEZ, E., LÓPEZ, J. & 2 October 2007; accepted 23 October 2007

Int. Zoo Yb. (2008) 42: 190–198. c 2007 The Authors. Journal compilation c 2007 The Zoological Society of LondonYou can also read