Speakers of the House: Elections, 1913-2013

←

→

Page content transcription

If your browser does not render page correctly, please read the page content below

Speakers of the House: Elections, 1913-2013

Richard S. Beth

Specialist on Congress and the Legislative Process

Valerie Heitshusen

Analyst on Congress and the Legislative Process

January 4, 2013

Congressional Research Service

7-5700

www.crs.gov

RL30857

CRS Report for Congress

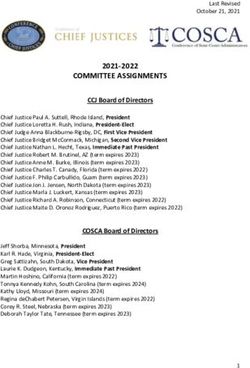

Prepared for Members and Committees of CongressSpeakers of the House: Elections, 1913-2013 Summary Each new House elects a Speaker by roll call vote when it first convenes. Customarily, the conference of each major party nominates a candidate whose name is placed in nomination. Members normally vote for the candidate of their own party conference, but may vote for any individual, whether nominated or not. To be elected, a candidate must receive an absolute majority of all the votes cast for individuals. This number may be less than a majority (now 218) of the full membership of the House, because of vacancies, absentees, or Members voting “present.” This report provides data on elections of the Speaker in each Congress since 1913, when the House first reached its present size of 435 Members. During that period (63rd through 113th Congresses), a Speaker was elected four times with the votes of less than a majority of the full membership. If a Speaker dies or resigns during a Congress, the House immediately elects a new one. Four such elections have been necessary since 1913. In the earlier two cases, the House elected the new Speaker by resolution; in the more recent two, the body used the same procedure as at the outset of a Congress. If no candidate receives the requisite majority, the roll call is repeated until a Speaker is elected. Since 1913, this procedure has been necessary only in 1923, when nine ballots were required before a Speaker was elected. From 1913 through 1943, it usually happened that some Members voted for candidates other than those of the two major parties. The candidates in question were usually those representing the “progressive” group (reformers originally associated with the Republican party), and in some Congresses, their names were formally placed in nomination on behalf of that group. From 1943 through 1995, only the nominated Republican and Democratic candidates received votes, representing the culmination of the establishment of an exclusively two-party system at the national level. In six of the nine elections since 1997 (105th, 107th-109th, 112th, and 113th Congresses), however, some Members voted for Members of their own party other than the party nominees. Also, some Members in 1997 and in 2013 voted for candidates who were not then Members of the House. Although the Constitution does not so require, the Speaker has always been a Member. Further, in 2001, a Member affiliated with one major party voted for the nominee of the other. Until then, House practice had long taken for granted that voting for Speaker was demonstrative of party affiliation in the House. The report will be updated as additional elections for Speaker occur. Congressional Research Service

Speakers of the House: Elections, 1913-2013 Contents Regular and Special Elections of the Speaker ................................................................................. 1 Size of the House and Majority Required to Elect .......................................................................... 1 Third and Additional Candidates ..................................................................................................... 3 Tables Table 1. Individuals Receiving Votes for Speaker, 1913-2013 ........................................................ 4 Contacts Author Contact Information............................................................................................................. 8 Congressional Research Service

Speakers of the House: Elections, 1913-2013

Regular and Special Elections of the Speaker

The traditional practice of the House is to elect a Speaker by roll call vote upon first convening

after a general election of Representatives. Customarily, the conference of each major party in the

House selects a candidate whose name is formally placed in nomination before the roll call.

Members may vote for one of these nominated candidates or for another individual. Usually,

Members vote for the candidate nominated by their own party conference, since the outcome of

this vote in effect establishes which party has the majority, and therefore will organize the House.

Table 1 presents data on the votes cast for candidates for Speaker of the House of Representatives

in each Congress from 1913 (63rd Congress) through 2013 (113th Congress). It shows the votes

cast for the nominees of the two major parties, for other candidates nominated from the floor, and

for individuals not formally nominated.

Included in the table are not only the elections held regularly at the outset of each Congress, but

also those held during the course of a Congress as a result of the death or resignation of a sitting

Speaker. Such elections have occurred four times during the period examined:

• in 1936 (74th Congress) upon the death of Speaker Joseph Byrns (D-TN);

• in 1940 (76th Congress) upon the death of Speaker William Bankhead (D-AL);

• in 1962 (87th Congress) upon the death of Speaker Sam Rayburn (D-TX); and

• in 1989 (101st Congress) upon the resignation of Speaker Jim Wright (D-TX).

On the two earlier occasions among these four, the election was by resolution rather than by roll

call vote. On the more recent two, the same procedure was followed as at the start of a Congress.

Size of the House and Majority Required to Elect

The data presented here cover the period during which the permanent size of the House has been

set at 435 Members. This period corresponds to that since the admission of Arizona and New

Mexico as the 47th and 48th States in 1912. The actual size of the House was 436, and then 437,

for a brief period between the admission of Alaska and Hawaii (in 1958 and 1959) and the

reapportionment of Representatives following the 1960 census.

By practice of the House going back to its earliest days, an absolute majority of the Members

present and voting is required in order to elect a Speaker. A majority of the full membership of the

House (218, in a House of 435) is not required. Precedents emphasize that the requirement is for a

majority of “the total number of votes cast for a person by name.”1 A candidate for Speaker may

receive a majority of the votes cast, and be elected, while failing to obtain a majority of the full

membership, because some Members either are not present to vote, or vote “present” rather than

voting for a candidate. During the period examined, this kind of result has occurred four times:

1

The Clerk, “Parliamentary Inquiry,” remarks from the chair, Congressional Record, vol. 143, January 7, 1997, p. 117.

Congressional Research Service 1Speakers of the House: Elections, 1913-2013

• in 1917 (65th Congress), “Champ” Clark (D-MO) was elected with 217 votes;

• in 1923 (68th Congress), Frederick Gillett (R-MA) was elected with 215 votes;

• in 1943 (78th Congress), Sam Rayburn (D-TX) was elected with 217 votes; and

• in 1997 (105th Congress), Newt Gingrich (R-GA) was elected with 216 votes.

Also, in 1931 (72nd Congress), the candidate of the new Democratic majority, John Nance Garner

of Texas (later Vice President), received 218 votes, a bare majority of the membership. The table

does not take into account the number of vacancies existing in the House at the time of the

election; it therefore cannot show whether or not any Speaker may have been elected lacking a

majority of the then qualified membership of the House.2

If no candidate obtains the requisite majority, the roll call is repeated. On these subsequent

ballots, Members may still vote for any individual; no restrictions have ever been imposed, such

as that the lowest candidate on each ballot must drop out, or that no new candidate may enter.

Because of the predominance of the two established national parties throughout the period

examined, only once during that period did the House fail to elect on the first roll call.3 In 1923

(68th Congress), in a closely divided House, both major party nominees initially failed to gain a

majority because of votes cast for other candidates by Members from the Progressive Party, or

from the “progressive” wing of the Republican Party. Progressives agreed to vote for the

Republican candidate only on the ninth ballot, after the Republican leadership had agreed to

accept a number of procedural reforms favored by the progressives. Thus the Republican was

ultimately elected, although (as noted earlier) still with less than a majority of the full

membership.4

2

The existence of vacancies at the point when a new House first convened was more common before the 20th

Amendment took effect in 1936. Until that time, a Congress elected in one November did not begin its term until

March of the following year, and did not convene until December of that year, unless the previous Congress provided

otherwise by law.

3

This occurrence, however, was more common before the period covered in this report, when the two-party system had

not become as thoroughly established, nor the discipline accompanying it as pronounced.

4

Full results were as follows:

Ballot and Date Gillett (R) Garrett (D) Cooper Madden Present

1 December 3, 1923 197 195 17 5 4

2 December 3 194 194 17 6 3

3 December 3 195 196 17 5 3

4 December 3 197 196 17 5 3

5 December 4 197 197 17 5 3

6 December 4 195 197 17 5 3

7 December 4 196 198 17 5 3

8 December 4 197 198 17 5 3

9 December 5 215 197 0 2 4

Congressional Research Service 2Speakers of the House: Elections, 1913-2013 Third and Additional Candidates The opening of the 105th Congress in 1997 marked the first time since 1943 that anyone other than the two major party candidates received votes for Speaker. Exclusively two-party voting had characterized the entire period since World War II, and the entire period of the “modern Congress,” usually reckoned from the implementation in 1947 (80th Congress) of the Legislative Reorganization Act of 1946 (P.L. 79-601, 60 Stat. 812). Earlier, however, the presence of votes for other candidates was normal, occurring in 11 of the 16 Congresses (63rd through 78th) that convened from 1913 through 1943. On seven of those 11 occasions, candidates for Speaker, in addition to those of the two major parties, were formally nominated. These events reflect chiefly the influence in Congress, during those three decades, of the progressive movement. The additional nominations were offered in the name of that movement, and the votes cast for Members other than the major party nominees also generally represent an expression of progressive sentiments. The pattern of occurrence of additional nominations (displayed in the table) reflects changing views of Members identifying themselves as “progressives” about whether to constitute themselves in the House as a separate Progressive Party caucus or as a wing of the Republican Party. So does the pattern of shifts in the party labels by which these nominees and others receiving votes chose to designate themselves. The last formal Progressive Party nominee appeared in 1937 (75th Congress). After defeats in the following election, the only two remaining Members representing the Progressive Party were reduced to voting for each other for Speaker, and beginning in 1947 (80th Congress), the last standard bearer of the tendency accepted the Republican label. The demise of this movement in the House represented the final stage in the establishment of a two-party system at the national level. In 1997, 2001, 2003, 2005, 2011, and 2013, at least one Member voted for a Member of their own party who was not that party’s official nominee. These events seem to manifest a new pattern of behavior in elections for Speaker. Votes cast for other candidates in these years seem more often to have reflected specific circumstances and events than established factions or identifiable political groupings Votes cast for other candidates in these years reflected specific circumstances and events, however, rather than established factions or even identifiable political groupings. The 1997 and 2013 ballots were also notable because votes were cast for candidates who were not Members of the House at the time. Although the Constitution does not require the Speaker (or any other officer of either chamber) to be a Member, the Speaker has always been so, and it is not known that any votes for individuals other than Members to be Speaker had ever previously been cast in the entire history of the House. Finally, in 2001, a Member who bore the designation of one major party voted for the nominee of the other. Although the table below does not indicate the party affiliation of the Members voting for each candidate, examination of other available records confirms that no such action had occurred at least for the previous half century. Rather, House practice had long taken for granted that the vote for Speaker determines, or at least demonstrates, not only which parties command majority and minority status, but also of which Members each of these parties is composed. Subsequently, in organizing for that Congress (the 107th), the party caucus against whose nominee the Member in question voted did not formally expel him, but declined to provide him with committee assignments. Congressional Research Service 3

Speakers of the House: Elections, 1913-2013

Table 1. Individuals Receiving Votes for Speaker, 1913-2013

Year Republican Nominee Votes Democratic Nominee Votes Others Receiving Votes Votes

1913 James R. Mann (IL) 111 James B. (“Champ”) Clark (MO) 272 Victor Murdock (P-KS) 18

Henry A. Cooper (R-WI) 4

John M. Nelson (R-WI) 1

1915 James R. Mann (IL) 195 James B. (“Champ”) Clark (MO) 222

1917 James R. Mann (IL) 205 James B. (“Champ”) Clark (MO) 217 Irvine L. Lenroot (R-WI) 2

Frederick H. Gillett (R-MA) 2

1919 Frederick H. Gillett (MA) 228 James B. (“Champ”) Clark (MO) 172

1921 Frederick H. Gillett (MA) 297 Claude Kitchin (NC) 122

1923 (first ballot) Frederick H. Gillett (MA) 197 Finis J. Garrett (TN) 195 Henry A. Cooper (R-WI) 17

Martin B. Madden (R-IL) 5

(ninth ballot) Frederick H. Gillett (MA) 215 Finis J. Garrett (TN) 197 Martin B. Madden (R-IL) 2

1925 Nicholas Longworth (OH) 229 Finis J. Garrett (TN) 173 Henry A. Cooper (R-WI) 13

1927 Nicholas Longworth (OH) 225 Finis J. Garrett (TN) 187

1929 Nicholas Longworth (OH) 254 John N. Garner (TX) 143

1931 Bertrand H. Snell (NY) 207 John N. Garner (TX) 218 George J. Schneider (R-WI) 5

1933 Bertrand H. Snell (NY) 110 Henry T. Rainey (IL) 302 Paul J. Kvale (F-L-MN) 5

1935 Bertrand H. Snell (NY) 95 Joseph W. Byrns (TN) 317 George J. Schneider (P-WI) 9

W.P. Lambertson (R-KS) 2

1936 (June 4)a William B. Bankhead (AL) (H.Res. 543)b voice vote

1937 Bertrand H. Snell (NY) 83 William B. Bankhead (AL) 324 George J. Schneider (P-WI) 10

Fred L. Crawford (R-MI) 2

1939 Joseph W. Martin (MA) 168 William B. Bankhead (AL) 249 Merlin Hull (P-WI) 1

Bernard J. Gehrmann (P-WI) 1

1940 (Sept. 16)a Sam Rayburn (TX) voice vote

(H.Res. 602)b

1941 Joseph W. Martin (MA) 159 Sam Rayburn (TX) 247 Merlin Hull (P-WI) 2

Bernard J. Gehrmann (P-WI) 1

1943 Joseph W. Martin (MA) 206 Sam Rayburn (TX) 217 Merlin Hull (P-WI) 1

Harry Sauthoff (P-WI) 1

CRS-4Speakers of the House: Elections, 1913-2013 Year Republican Nominee Votes Democratic Nominee Votes Others Receiving Votes Votes 1945 Joseph W. Martin (MA) 168 Sam Rayburn (TX) 224 1947 Joseph W. Martin (MA) 244 Sam Rayburn (TX) 182 1949 Joseph W. Martin (MA) 160 Sam Rayburn (TX) 255 1951 Joseph W. Martin (MA) 193 Sam Rayburn (TX) 231 1953 Joseph W. Martin (MA) 220 Sam Rayburn (TX) 201 1955 Joseph W. Martin (MA) 198 Sam Rayburn (TX) 228 1957 Joseph W. Martin (MA) 199 Sam Rayburn (TX) 227 1959 Charles A. Halleck (IN) 148 Sam Rayburn (TX) 281 1961 Charles A. Halleck (IN) 170 Sam Rayburn (TX) 258 1962 (Jan. 10)a Charles A. Halleck (IN) 166 John W. McCormack (MA) 248 1963 Charles A. Halleck (IN) 175 John W. McCormack (MA) 256 1965 Gerald R. Ford (MI) 139 John W. McCormack (MA) 289 1967 Gerald R. Ford (MI) 186 John W. McCormack (MA) 246 1969 Gerald R. Ford (MI) 187 John W. McCormack (MA) 241 1971 Gerald R. Ford (MI) 176 Carl B. Albert (OK) 250 1973 Gerald R. Ford (MI) 188 Carl B. Albert (OK) 236 1975 John J. Rhodes (AZ) 143 Carl B. Albert (OK) 287 1977 John J. Rhodes (AZ) 142 Thomas P. (“Tip”) O’Neill (MA) 290 1979 John J. Rhodes (AZ) 152 Thomas P. (“Tip”) O’Neill (MA) 268 1981 Robert H. Michel (IL) 183 Thomas P. (“Tip”) O’Neill (MA) 233 1983 Robert H. Michel (IL) 155 Thomas P. (“Tip”) O’Neill (MA) 260 1985 Robert H. Michel (IL) 175 Thomas P. (“Tip”) O’Neill (MA) 247 1987 Robert H. Michel (IL) 173 Jim Wright (TX) 254 1989 Robert H. Michel (IL) 170 Jim Wright (TX) 253 1989 (June 6)a Robert H. Michel (IL) 164 Thomas S. Foley (WA) 251 1991 Robert H. Michel (IL) 165 Thomas S. Foley (WA) 262 1993 Robert H. Michel (IL) 174 Thomas S. Foley (WA) 255 CRS-5

Speakers of the House: Elections, 1913-2013

Year Republican Nominee Votes Democratic Nominee Votes Others Receiving Votes Votes

1995 Newt Gingrich (GA) 228 Richard A. Gephardt (MO) 202

1997 Newt Gingrich (GA) 216 Richard A. Gephardt (MO) 205 James Leach (R-IA) 2

Robert H. Michelc 1

Robert Walkerc 1

1999 J. Dennis Hastert (IL) 220 Richard A. Gephardt (MO) 205

2001 J. Dennis Hastert (IL) 222 Richard A. Gephardt (MO) 206 John P. Murtha (D-PA) 1

2003 J. Dennis Hastert (IL) 228 Nancy Pelosi (CA) 201 John P. Murtha (D-PA) 1

2005 J. Dennis Hastert (IL) 226 Nancy Pelosi (CA) 199 John P. Murtha (D-PA) 1

2007 John A. Boehner (OH) 202 Nancy Pelosi (CA) 233

2009 John A. Boehner (OH) 174 Nancy Pelosi (CA) 255

2011 John A. Boehner (OH) 241 Nancy Pelosi (CA) 173 Heath Shuler (D-NC) 11

John Lewis (D-GA) 2

Jim Costa (D-CA) 1

Dennis Cardoza (D-CA) 1

Jim Cooper (D-TN) 1

Marcy Kaptur (D-OH) 1

Steny H. Hoyer (D-MD) 1

2013 John A. Boehner (OH) 220 Nancy Pelosi (CA) 192 Eric Cantor (R-VA) 3

Allen Westc 2

Jim Cooper (D-TN) 2

John Lewis (D-GA) 1

Colin Powellc 1

Raúl R. Labrador (R-ID) 1

Jim Jordan (R-OH) 1

David Walkerc 1

Justin Amash (R-MI) 1

John Dingell (D-MI) 1

Source: Journals of the House of Representatives (for 2003-2011, Congressional Record, daily edition, and for 2013, Clerk of the House website). Party designations are

taken from the Congressional Directory for the respective years since these reflect a Member’s official party self-designation; historical sources may differ as to the effective

party affiliation of certain individuals.

Key:

Elected candidate in bold.

“Other” candidate’s name formally placed in nomination in italic.

Party designations of “other” candidates: R = Republican, P = Progressive, F-L = Farmer-Labor.

CRS-6Speakers of the House: Elections, 1913-2013 Notes: a. Special election to fill a vacancy in the Speakership caused by death or resignation. b. Elected by resolution, not by roll call from nominations. c. Not a Member of the House at the time. CRS-7

Speakers of the House: Elections, 1913-2013 Author Contact Information Richard S. Beth Valerie Heitshusen Specialist on Congress and the Legislative Process Analyst on Congress and the Legislative Process rbeth@crs.loc.gov, 7-8667 vheitshusen@crs.loc.gov, 7-8635 Congressional Research Service 8

You can also read