Practice Guidelines for Central Venous Access

←

→

Page content transcription

If your browser does not render page correctly, please read the page content below

Practice Guidelines for Central Venous Access

A Report by the American Society of Anesthesiologists Task

Force on Central Venous Access

P RACTICE Guidelines are systematically developed rec-

ommendations that assist the practitioner and patient

in making decisions about health care. These recommenda-

• What other guideline statements are available on this topic?

X Several major organizations have produced practice guide-

lines on central venous access128 –132

tions may be adopted, modified, or rejected according to • Why was this Guideline developed?

clinical needs and constraints, and are not intended to re- X The ASA has created this new Practice Guideline to provide

place local institutional policies. In addition, Practice Guide- updated recommendations on some issues and new rec-

ommendations on issues that have not been previously ad-

lines developed by the American Society of Anesthesiologists dressed by other guidelines. This was based on a rigorous

(ASA) are not intended as standards or absolute require- evaluation of recent scientific literature as well as findings

ments, and their use cannot guarantee any specific outcome. from surveys of expert consultants and randomly selected

Practice Guidelines are subject to revision as warranted by ASA members

the evolution of medical knowledge, technology, and prac- • How does this statement differ from existing guidelines?

X The ASA Guidelines differ in areas such as insertion site

tice. They provide basic recommendations that are sup- selection (e.g., upper body site) guidance for catheter place-

ported by a synthesis and analysis of the current literature, ment (e.g., use of real-time ultrasound) and verification of

expert and practitioner opinion, open forum commentary, venous location of the catheter

and clinical feasibility data. • Why does this statement differ from existing guidelines?

X The ASA Guidelines differ from existing guidelines because

it addresses the use of bundled techniques, use of an as-

Methodology sistant during catheter placement, and management of ar-

terial injury

A. Definition of Central Venous Access

For these Guidelines, central venous access is defined as

placement of a catheter such that the catheter is inserted into internal jugular veins, subclavian veins, iliac veins, and com-

a venous great vessel. The venous great vessels include the mon femoral veins.* Excluded are catheters that terminate in

superior vena cava, inferior vena cava, brachiocephalic veins, a systemic artery.

Developed by the American Society of Anesthesiologists Task B. Purposes of the Guidelines

Force on Central Venous Access: Stephen M. Rupp, M.D., Seattle, The purposes of these Guidelines are to (1) provide guid-

Washington (Chair); Jeffrey L. Apfelbaum, M.D., Chicago, Illinois;

Casey Blitt, M.D., Tucson, Arizona; Robert A. Caplan, M.D., Seattle,

ance regarding placement and management of central ve-

Washington; Richard T. Connis, Ph.D., Woodinville, Washington; nous catheters, (2) reduce infectious, mechanical, throm-

Karen B. Domino, M.D., M.P.H., Seattle, Washington; Lee A. Fleisher, botic, and other adverse outcomes associated with central

M.D., Philadelphia, Pennsylvania; Stuart Grant, M.D., Durham, North

Carolina; Jonathan B. Mark, M.D., Durham, North Carolina; Jeffrey P.

venous catheterization, and (3) improve management of

Morray, M.D., Paradise Valley, Arizona; David G. Nickinovich, Ph.D., arterial trauma or injury arising from central venous cath-

Bellevue, Washington; and Avery Tung, M.D., Wilmette, Illinois. eterization.

Received from the American Society of Anesthesiologists, Park

Ridge, Illinois. Submitted for publication October 20, 2011. Accepted

for publication October 20, 2011. Supported by the American Society of

C. Focus

Anesthesiologists and developed under the direction of the Committee These Guidelines apply to patients undergoing elective cen-

on Standards and Practice Parameters, Jeffrey L. Apfelbaum, M.D. tral venous access procedures performed by anesthesiologists

(Chair). Approved by the ASA House of Delegates on October 19,

2011. Endorsed by the Society of Cardiovascular Anesthesiologists,

or health care professionals under the direction/supervision

October 4, 2010; the Society of Critical Care Anesthesiologists March 16, of anesthesiologists. The Guidelines do not address (1) clin-

2011; the Society of Pediatric Anesthesia March 29, 2011. A complete ical indications for placement of central venous catheters, (2)

list of references used to develop these updated Guidelines, arranged

alphabetically by author, is available as Supplemental Digital Content 1,

emergency placement of central venous catheters, (3) pa-

http://links.lww.com/ALN/A783. tients with peripherally inserted central catheters, (4) place-

Address correspondence to the American Society of Anesthesi- ment and residence of a pulmonary artery catheter, (5) inser-

ologists: 520 North Northwest Highway, Park Ridge, Illinois 60068- tion of tunneled central lines (e.g., permacaths, portacaths,

2573. These Practice Guidelines, as well as all ASA Practice Param-

eters, may be obtained at no cost through the Journal Web site,

www.anesthesiology.org. Supplemental digital content is available for this article. Direct

* This description of the venous great vessels is consistent with URL citations appear in the printed text and are available in

the venous subset for central lines defined by the National Health- both the HTML and PDF versions of this article. Links to the

care Safety Network (NHSN). digital files are provided in the HTML text of this article on the

Copyright © 2012, the American Society of Anesthesiologists, Inc. Lippincott Journal’s Web site (www.anesthesiology.org).

Williams & Wilkins. Anesthesiology 2012; 116:539 –73

Anesthesiology, V 116 • No 3 539 March 2012Practice Guidelines

Hickman®, Quinton®, (6) methods of detection or treat- Scientific Evidence

ment of infectious complications associated with central ve-

Study findings from published scientific literature were ag-

nous catheterization, or (7) diagnosis and management of gregated and are reported in summary form by evidence cat-

central venous catheter-associated trauma or injury (e.g., egory, as described in the following paragraphs. All literature

pneumothorax or air embolism), with the exception of ca- (e.g., randomized controlled trials, observational studies, case

rotid arterial injury. reports) relevant to each topic was considered when evaluat-

ing the findings. However, for reporting purposes in this

D. Application document, only the highest level of evidence (i.e., level 1, 2,

These Guidelines are intended for use by anesthesiologists or 3 within category A, B, or C, as identified in the following

and individuals who are under the supervision of an anes- paragraphs) is included in the summary.

thesiologist. They also may serve as a resource for other

physicians (e.g., surgeons, radiologists), nurses, or health Category A: Supportive Literature

care providers who manage patients with central venous Randomized controlled trials report statistically significant

catheters. (P ⬍ 0.01) differences between clinical interventions for a

specified clinical outcome.

E. Task Force Members and Consultants Level 1: The literature contains multiple randomized con-

The ASA appointed a Task Force of 12 members, including trolled trials, and aggregated findings are supported

anesthesiologists in both private and academic practice from by meta-analysis.‡

various geographic areas of the United States and two con- Level 2: The literature contains multiple randomized con-

sulting methodologists from the ASA Committee on Stan- trolled trials, but the number of studies is insuffi-

dards and Practice Parameters. cient to conduct a viable meta-analysis for the pur-

The Task Force developed the Guidelines by means of a pose of these Guidelines.

seven-step process. First, they reached consensus on the cri- Level 3: The literature contains a single randomized con-

teria for evidence. Second, original published research stud- trolled trial.

ies from peer-reviewed journals relevant to central venous

access were reviewed and evaluated. Third, expert consul- Category B: Suggestive Literature

tants were asked to (1) participate in opinion surveys on the Information from observational studies permits inference of

effectiveness of various central venous access recommenda- beneficial or harmful relationships among clinical interven-

tions and (2) review and comment on a draft of the Guide- tions and clinical outcomes.

lines. Fourth, opinions about the Guideline recommenda- Level 1: The literature contains observational comparisons

tions were solicited from a sample of active members of the (e.g., cohort, case-control research designs) of clin-

ASA. Opinions on selected topics related to pediatric pa- ical interventions or conditions and indicates statis-

tients were solicited from a sample of active members of the tically significant differences between clinical inter-

Society for Pediatric Anesthesia (SPA). Fifth, the Task Force ventions for a specified clinical outcome.

held open forums at three major national meetings† to solicit Level 2: The literature contains noncomparative observa-

input on its draft recommendations. Sixth, the consultants tional studies with associative (e.g., relative risk,

were surveyed to assess their opinions on the feasibility of correlation) or descriptive statistics.

implementing the Guidelines. Seventh, all available informa- Level 3: The literature contains case reports.

tion was used to build consensus within the Task Force to

finalize the Guidelines. A summary of recommendations Category C: Equivocal Literature

may be found in appendix 1. The literature cannot determine whether there are beneficial

or harmful relationships among clinical interventions and

F. Availability and Strength of Evidence clinical outcomes.

Preparation of these Guidelines followed a rigorous meth- Level 1: Meta-analysis did not find significant differences

odologic process. Evidence was obtained from two principal (P ⬎ 0.01) among groups or conditions.

sources: scientific evidence and opinion-based evidence. Level 2: The number of studies is insufficient to conduct

meta-analysis, and (1) randomized controlled trials

† Society for Pediatric Anesthesia Winter Meeting, April 17, 2010,

San Antonio, Texas; Society of Cardiovascular Anesthesia 32nd have not found significant differences among

Annual Meeting, April 25, 2010, New Orleans, Louisiana, and Inter- groups or conditions or (2) randomized controlled

national Anesthesia Research Society Annual Meeting, May 22, 2011, trials report inconsistent findings.

Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada.

Level 3: Observational studies report inconsistent findings

‡ All meta-analyses are conducted by the ASA methodology

group. Meta-analyses from other sources are reviewed but not or do not permit inference of beneficial or harmful

included as evidence in this document. relationships.

Anesthesiology 2012; 116:539 –73 540 Practice GuidelinesSPECIAL ARTICLES

Category D: Insufficient Evidence from Literature Disagree. Median score of 2 (at least 50% of responses are 2

The lack of scientific evidence in the literature is described by or 1 and 2).

the following terms: Strongly Disagree. Median score of 1 (at least 50% of re-

sponses are 1).

Inadequate: The available literature cannot be used to assess

relationships among clinical interventions and

clinical outcomes. The literature either does not Category C: Informal Opinion

meet the criteria for content as defined in the “Fo- Open-forum testimony, Internet-based comments, letters,

cus” of the Guidelines or does not permit a clear and editorials are all informally evaluated and discussed dur-

interpretation of findings due to methodologic con- ing the development of Guideline recommendations. When

cerns (e.g., confounding in study design or imple- warranted, the Task Force may add educational information

mentation). or cautionary notes based on this information.

Silent: No identified studies address the specified relation- Guidelines

ships among interventions and outcomes.

I. Resource Preparation

Opinion-based Evidence Resource preparation includes (1) assessing the physical envi-

ronment where central venous catheterization is planned to de-

All opinion-based evidence relevant to each topic (e.g., survey data,

termine the feasibility of using aseptic techniques, (2) availabil-

open-forum testimony, Internet-based comments, letters, editori-

ity of a standardized equipment set, (3) use of an assistant for

als) is considered in the development of these Guidelines. However,

central venous catheterization, and (4) use of a checklist or pro-

only the findings obtained from formal surveys are reported.

tocol for central venous catheter placement and maintenance.

Opinion surveys were developed by the Task Force to

address each clinical intervention identified in the docu- The literature is insufficient to specifically evaluate the

ment. Identical surveys were distributed to expert consul- effect of the physical environment for aseptic catheter inser-

tants and ASA members, and a survey addressing selected tion, availability of a standardized equipment set, or the use

pediatric issues was distributed to SPA members. of an assistant on outcomes associated with central venous

catheterization (Category D evidence). An observational study

reports that the implementation of a trauma intensive care

Category A: Expert Opinion unit multidisciplinary checklist is associated with reduced

Survey responses from Task Force-appointed expert consultants catheter-related infection rates (Category B2 evidence).1 Ob-

are reported in summary form in the text, with a complete servational studies report reduced catheter-related blood-

listing of consultant survey responses reported in appendix 5. stream infection rates when intensive care unit-wide bundled

protocols are implemented (Category B2 evidence).2–7 These

Category B: Membership Opinion studies do not permit the assessment of the effect of any

Survey responses from active ASA and SPA members are re- single component of a checklist or bundled protocol on out-

ported in summary form in the text, with a complete listing of come. The Task Force notes that the use of checklists in other

ASA and SPA member survey responses reported in appendix 5. specialties or professions has been effective in reducing the

error rate for a complex series of activities.8,9

Survey responses are recorded using a 5-point scale and

summarized based on median values.§ The consultants and ASA members strongly agree that cen-

tral venous catheterization should be performed in a location

Strongly Agree. Median score of 5 (at least 50% of the that permits the use of aseptic techniques. The consultants and

responses are 5). ASA members strongly agree that a standardized equipment set

Agree. Median score of 4 (at least 50% of the responses are should be available for central venous access. The consultants

4 or 4 and 5). and ASA members agree that a trained assistant should be used

Equivocal. Median score of 3 (at least 50% of the responses during the placement of a central venous catheter. The ASA

are 3, or no other response category or com- members agree and the consultants strongly agree that a check-

bination of similar categories contain at list or protocol should be used for the placement and mainte-

least 50% of the responses). nance of central venous catheters.

§ When an equal number of categorically distinct responses are Recommendations for Resource Preparation. Central ve-

obtained, the median value is determined by calculating the arith- nous catheterization should be performed in an environ-

metic mean of the two middle values. Ties are calculated by a ment that permits use of aseptic techniques. A standard-

predetermined formula.

ized equipment set should be available for central venous

㛳 Refer to appendix 2 for an example of a list of standardized

equipment for adult patients. access.㛳 A checklist or protocol should be used for place-

# Refer to appendix 3 for an example of a checklist or protocol. ment and maintenance of central venous catheters.# An

** Refer to appendix 4 for an example of a list of duties per- assistant should be used during placement of a central

formed by an assistant. venous catheter.**

Anesthesiology 2012; 116:539 –73 541 Practice GuidelinesPractice Guidelines

II. Prevention of Infectious Complications 100%), caps (100% and 94.7%), and masks covering both

Interventions intended to prevent infectious complica- the mouth and nose (100% and 98.1%).

tions associated with central venous access include, but are

not limited to (1) intravenous antibiotic prophylaxis, (2)

aseptic techniques (i.e., practitioner aseptic preparation Selection of Antiseptic Solution

and patient skin preparation), (3) selection of coated or Chlorhexidine solutions: A randomized controlled trial com-

impregnated catheters, (4) selection of catheter insertion paring chlorhexidine (2% aqueous solution without alcohol)

site, (5) catheter fixation method, (6) insertion site dress- with 10% povidone iodine (without alcohol) for skin prep-

ings, (7) catheter maintenance procedures, and (8) aseptic aration reports equivocal findings regarding catheter coloni-

techniques using an existing central venous catheter for zation (P ⫽ 0.013) and catheter-related bacteremia (P ⫽

injection or aspiration. 0.28) (Category C2 evidence).13 The literature is insufficient

to evaluate chlorhexidine with alcohol compared with povi-

Intravenous Antibiotic Prophylaxis. Randomized con-

done-iodine with alcohol (Category D evidence). The litera-

trolled trials indicate that catheter-related infections and

ture is insufficient to evaluate the safety of antiseptic solu-

sepsis are reduced when prophylactic intravenous antibi-

tions containing chlorhexidine in neonates, infants and

otics are administered to high-risk immunosuppressed

children (Category D evidence).

cancer patients or neonates. (Category A2 evidence).10,11

Solutions containing alcohol: Comparative studies are in-

The literature is insufficient to evaluate outcomes associ-

sufficient to evaluate the efficacy of chlorhexidine with alco-

ated with the routine use of intravenous antibiotics (Cat-

hol in comparison with chlorhexidine without alcohol for

egory D evidence).

skin preparation during central venous catheterization (Cat-

The consultants and ASA members agree that intrave-

egory D evidence). A randomized controlled trial of povidone-

nous antibiotic prophylaxis may be administered on a

iodine with alcohol indicates that catheter tip colonization is

case-by-case basis for immunocompromised patients or

reduced when compared with povidone-iodine alone (Cate-

high-risk neonates. The consultants and ASA members

gory A3 evidence); equivocal findings are reported for cathe-

agree that intravenous antibiotic prophylaxis should not ter-related infection (P ⫽ 0.04) and clinical signs of infection

be administered routinely. (P ⫽ 0.09) (Category C2 evidence).14

Recommendations for Intravenous Antibiotic Prophylaxis. The consultants and ASA members strongly agree that

For immunocompromised patients and high-risk neonates, chlorhexidine with alcohol should be used for skin prep-

administer intravenous antibiotic prophylaxis on a case-by- aration. SPA members are equivocal regarding whether

case basis. Intravenous antibiotic prophylaxis should not be chlorhexidine-containing solutions should be used for

administered routinely. skin preparation in neonates (younger than 44 gestational

weeks); they agree with the use of chlorhexidine in infants

(younger than 2 yr) and strongly agree with its use in

Aseptic Preparation and Selection of Antiseptic Solution

children (2–16 yr).

Aseptic preparation of practitioner, staff, and patients: A ran-

domized controlled trial comparing maximal barrier precau-

tions (i.e., mask, cap, gloves, gown, large full-body drape) Recommendations for Aseptic Preparation and Selection

with a control group (i.e., gloves and small drape) reported of Antiseptic Solution

equivocal findings for reduced colonization (P ⫽ 0.03) and In preparation for the placement of central venous catheters,

catheter-related septicemia (P ⫽ 0.06) (Category C2 evi- use aseptic techniques (e.g., hand washing) and maximal bar-

dence).12 The literature is insufficient to evaluate the efficacy rier precautions (e.g., sterile gowns, sterile gloves, caps, masks

of specific aseptic activities (e.g., hand washing) or barrier covering both mouth and nose, and full-body patient

precautions (e.g., sterile full-body drapes, sterile gown, drapes). A chlorhexidine-containing solution should be used

gloves, mask, cap) (Category D evidence). Observational stud- for skin preparation in adults, infants, and children; for ne-

ies report hand washing, sterile full-body drapes, sterile onates, the use of a chlorhexidine-containing solution for

gloves, caps, and masks as elements of care “bundles” that skin preparation should be based on clinical judgment and

result in reduced catheter-related bloodstream infections institutional protocol. If there is a contraindication to chlo-

(Category B2 evidence).2–7 However, the degree to which each rhexidine, povidone-iodine or alcohol may be used. Unless

particular element contributed to improved outcomes could contraindicated, skin preparation solutions should contain

not be determined. alcohol.

Most consultants and ASA members indicated that the Catheters Containing Antimicrobial Agents. Meta-analysis

following aseptic techniques should be used in preparation of randomized controlled trials15–19 comparing antibiotic-

for the placement of central venous catheters: hand washing coated with uncoated catheters indicates that antibiotic-

(100% and 96%); sterile full-body drapes (87.3% and coated catheters reduce catheter colonization (Category A1

73.8%); sterile gowns (100% and 87.8%), gloves (100% and evidence). Meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials20 –24

Anesthesiology 2012; 116:539 –73 542 Practice GuidelinesSPECIAL ARTICLES

comparing silver-impregnated catheters with uncoated cath- Recommendations for Selection of Catheter Insertion Site.

eters report equivocal findings for catheter-related blood- Catheter insertion site selection should be based on clin-

stream infection (Category C1 evidence); randomized con- ical need. An insertion site should be selected that is not

trolled trials were equivocal regarding catheter colonization contaminated or potentially contaminated (e.g., burned or

(P ⫽ 0.16 – 0.82) (Category C2 evidence).20 –22,24 Meta-anal- infected skin, inguinal area, adjacent to tracheostomy or

yses of randomized controlled trials25–36 demonstrate that open surgical wound). In adults, selection of an upper

catheters coated with chlorhexidine and silver sulfadiazine body insertion site should be considered to minimize the

reduce catheter colonization (Category A1 evidence); equivo- risk of infection.

cal findings are reported for catheter-related bloodstream in- Catheter Fixation. The literature is insufficient to evaluate

fection (i.e., catheter colonization and corresponding posi- whether catheter fixation with sutures, staples or tape is as-

tive blood culture) (Category C1 evidence).25–27,29 –35,37,38 sociated with a higher risk for catheter-related infections

Cases of anaphylactic shock are reported after placement of a (Category D evidence).

catheter coated with chlorhexidine and silver sulfadiazine Most consultants and ASA members indicate that use of

(Category B3 evidence).39 – 41 sutures is the preferred catheter fixation technique to mini-

Consultants and ASA members agree that catheters coated mize catheter-related infection.

with antibiotics or a combination of chlorhexidine and silver Recommendations for Catheter Fixation. The use of su-

sulfadiazine may be used in selected patients based on infectious tures, staples, or tape for catheter fixation should be deter-

risk, cost, and anticipated duration of catheter use. mined on a local or institutional basis.

Recommendations for Use of Catheters Containing Anti- Insertion Site Dressings. The literature is insufficient to

microbial Agents. Catheters coated with antibiotics or a evaluate the efficacy of transparent bio-occlusive dressings

combination of chlorhexidine and silver sulfadiazine should to reduce the risk of infection (Category D evidence). Ran-

be used for selected patients based on infectious risk, cost, domized controlled trials are equivocal (P ⫽ 0.04 – 0.96)

and anticipated duration of catheter use. The Task Force regarding catheter tip colonization50,51 and inconsistent

notes that catheters containing antimicrobial agents are not a (P ⫽ 0.004 – 0.96) regarding catheter-related blood-

substitute for additional infection precautions. stream infection50,52 when chlorhexidine sponge dressings

Selection of Catheter Insertion Site. A randomized con- are compared with standard polyurethane dressings (Cate-

trolled trial comparing the subclavian and femoral insertion gory C2 evidence). A randomized controlled trial is also equiv-

sites report higher levels of catheter colonization with the ocal regarding catheter tip colonization for silver-impreg-

femoral site (Category A3 evidence); equivocal findings are nated transparent dressings compared with standard

reported for catheter-related sepsis (P ⫽ 0.07) (Category C2 dressings (P ⬎ 0.05) (Category C2 evidence).53 A randomized

evidence).42 A randomized controlled trial comparing the in- controlled trial reports a greater frequency of severe localized

ternal jugular insertion site with the femoral site reports no contact dermatitis when neonates receive chlorhexidine-im-

difference in catheter colonization (P ⫽ 0.79) or catheter pregnated dressings compared with povidone-iodine im-

related bloodstream infections (P ⫽ 0.42) (Category C2 evi- pregnated dressings (Category A3 evidence).54

dence).43 Prospective nonrandomized comparative studies The ASA members agree and the consultants strongly

are equivocal (i.e., inconsistent) regarding catheter-related agree that transparent bio-occlusive dressings should be used

colonization44 – 46 and catheter related bloodstream infec- to protect the site of central venous catheter insertion from

tion46 – 48 when the internal jugular site is compared with the infection. The consultants and ASA members agree that

subclavian site (Category C3 evidence). A nonrandomized dressings containing chlorhexidine may be used to reduce the

comparative study of burn patients reports that catheter col- risk of catheter-related infection. SPA members are equivocal

onization and bacteremia occur more frequently the closer regarding whether dressings containing chlorhexidine may

the catheter insertion site is to the burn wound (Category B1 be used for skin preparation in neonates (younger than 44

evidence).49 gestational weeks); they agree that the use of dressings con-

Most consultants indicate that the subclavian insertion taining chlorhexidine may be used in infants (younger than 2

site is preferred to minimize catheter-related risk of infec- yr) and children (2–16 yr).

tion. Most ASA members indicate that the internal jugular Recommendations for Insertion Site Dressings. Transpar-

insertion site is preferred to minimize catheter-related ent bio-occlusive dressings should be used to protect the

risk of infection. The consultants and ASA members agree site of central venous catheter insertion from infection.

that femoral catheterization should be avoided when pos- Unless contraindicated, dressings containing chlorhexi-

sible to minimize the risk of infection. The consultants dine may be used in adults, infants, and children. For

and ASA members strongly agree that an insertion site neonates, the use of transparent or sponge dressings con-

should be selected that is not contaminated or potentially taining chlorhexidine should be based on clinical judg-

contaminated. ment and institutional protocol.

Anesthesiology 2012; 116:539 –73 543 Practice GuidelinesPractice Guidelines

Catheter Maintenance. Catheter maintenance consists of (1) connectors with standard caps indicate decreased levels of

determining the optimal duration of catheterization, (2) con- microbial contamination of stopcock entry ports with

ducting catheter site inspections, (3) periodically changing needleless connectors (Category A2 evidence);63,64 no differ-

catheters, and (4) changing catheters using a guidewire in- ences in catheter-related bloodstream infection are reported

stead of selecting a new insertion site. (P ⫽ 0.3– 0.9) (Category C2 evidence).65,66

Nonrandomized comparative studies indicate that longer The consultants and ASA members strongly agree that

catheterizations are associated with higher rates of catheter catheter access ports should be wiped with an appropriate

colonization, infection, and sepsis (Category B2 evi- antiseptic before each access. The consultants and ASA mem-

dence).45,55 The literature is insufficient to evaluate whether bers agree that needleless ports may be used on a case-by-case

specified time intervals between catheter site inspections are basis. The consultants and ASA members strongly agree that

associated with a higher risk for catheter-related infection central venous catheter stopcocks should be capped when not

(Category D evidence). Randomized controlled trials report in use.

equivocal findings (P ⫽ 0.54 – 0.63) regarding differences in Recommendations for Aseptic Techniques Using an Ex-

catheter tip colonizations when catheters are changed at 3- isting Central Line. Catheter access ports should be wiped

versus 7-day intervals (Category C2 evidence).56,57 Meta-anal- with an appropriate antiseptic before each access when using

ysis of randomized controlled trials58 – 62 report equivocal an existing central venous catheter for injection or aspiration.

findings for catheter tip colonization when guidewires are Central venous catheter stopcocks or access ports should be

used to change catheters compared with the use of new in- capped when not in use. Needleless catheter access ports may

sertion sites (Category C1 evidence). be used on a case-by-case basis.

The ASA members agree and the consultants strongly

agree that the duration of catheterization should be based on III. Prevention of Mechanical Trauma or Injury

clinical need. The consultants and ASA members strongly Interventions intended to prevent mechanical trauma or

agree that (1) the clinical need for keeping the catheter in injury associated with central venous access include, but

place should be assessed daily; (2) catheters should be are not limited to (1) selection of catheter insertion site,

promptly removed when deemed no longer clinically neces- (2) positioning the patient for needle insertion and cath-

sary; (3) the catheter site should be inspected daily for signs of eter placement, (3) needle insertion and catheter place-

infection and changed when infection is suspected; and (4) ment, and (4) monitoring for needle, guidewire, and cath-

when catheter infection is suspected, replacing the catheter eter placement.

using a new insertion site is preferable to changing the cath- 1. Selection of Catheter Insertion Site. A randomized con-

eter over a guidewire. trolled trial comparing the subclavian and femoral insertion

Recommendations for Catheter Maintenance. The dura- sites reports that the femoral site had a higher frequency of

tion of catheterization should be based on clinical need. The thrombotic complications in adult patients (Category A3 ev-

clinical need for keeping the catheter in place should be as- idence).42 A randomized controlled trial comparing the in-

sessed daily. Catheters should be removed promptly when no ternal jugular insertion site with the femoral site reports

longer deemed clinically necessary. The catheter insertion equivocal findings for arterial puncture (P ⫽ 0.35), deep

site should be inspected daily for signs of infection, and the venous thrombosis (P ⫽ 0.62) or hematoma formation (P ⫽

catheter should be changed or removed when catheter inser- 0.47) (Category C2 evidence).43 A randomized controlled trial

tion site infection is suspected. When a catheter related in- comparing the internal jugular insertion site with the subcla-

fection is suspected, replacing the catheter using a new inser- vian site reports equivocal findings for successful veni-

tion site is preferable to changing the catheter over a puncture (P ⫽ 0.03) (Category C2 evidence).67 Nonran-

guidewire. domized comparative studies report equivocal findings for

arterial puncture, pneumothorax, hematoma, hemotho-

Aseptic Techniques Using an Existing Central Venous rax, or arrhythmia when the internal jugular insertion site

Catheter for Injection or Aspiration is compared with the subclavian insertion site (Category

C3 evidence).68 –70

Aseptic techniques using an existing central venous catheter

for injection or aspiration consist of (1) wiping the port with Most consultants and ASA members indicate that the

an appropriate antiseptic, (2) capping stopcocks or access internal jugular insertion site is preferred to minimize

ports, and (3) use of needleless catheter connectors or access catheter cannulation-related risk of injury or trauma.

ports. Most consultants and ASA members also indicate that the

The literature is insufficient to evaluate whether wiping internal jugular insertion site is preferred to minimize

ports or capping stopcocks when using an existing central catheter-related risk of thromboembolic injury or trauma.

venous catheter for injection or aspiration is associated with a Recommendations for Catheter Insertion Site Selection.

reduced risk for catheter-related infections (Category D evi- Catheter insertion site selection should be based on

dence). Randomized controlled trials comparing needleless clinical need and practitioner judgment, experience, and

Anesthesiology 2012; 116:539 –73 544 Practice GuidelinesSPECIAL ARTICLES

skill. In adults, selection of an upper body insertion site tion, and the skill and experience of the operator. The

should be considered to minimize the risk of thrombotic consultants and ASA members agree that the selection of a

complications. modified Seldinger technique versus a Seldinger technique

2. Positioning the Patient for Needle Insertion and Cath- should be based on the clinical situation and the skill and

eter Placement. Nonrandomized studies comparing the Tren- experience of the operator. The consultants and ASA

delenburg (i.e., head down) position with the normal supine members agree that the number of insertion attempts

position indicates that the right internal jugular vein increases in should be based on clinical judgment. The ASA members

diameter and cross-sectional area to a greater extent when adult agree and the consultants strongly agree that the decision

patients are placed in the Trendelenburg position (Category B2 to place two central catheters in a single vein should be

evidence).71–76 One nonrandomized study comparing the Tren- made on a case-by-case basis.

delenburg position with the normal supine position in pediatric Recommendations for Needle Insertion, Wire Placement,

patients reports an increase in right internal jugular vein diam- and Catheter Placement. Selection of catheter size (i.e.,

eter only for patients older than 6 yr (Category B2 evidence).77 outside diameter) and type should be based on the clinical

The consultants and ASA members strongly agree that, situation and skill/experience of the operator. Selection of

when clinically appropriate and feasible, central vascular ac- the smallest size catheter appropriate for the clinical situ-

cess in the neck or chest should be performed with the patient ation should be considered. Selection of a thin-wall needle

in the Trendelenburg position. (i.e., Seldinger) technique versus a catheter-over-the-nee-

dle (i.e., modified Seldinger) technique should be based

on the clinical situation and the skill/experience of the

Recommendations for Positioning the Patient for Needle operator. The decision to use a thin-wall needle technique

Insertion and Catheter Placement or a catheter-over-the-needle technique should be based at

When clinically appropriate and feasible, central venous ac- least in part on the method used to confirm that the wire

cess in the neck or chest should be performed with the patient resides in the vein before a dilator or large-bore catheter is

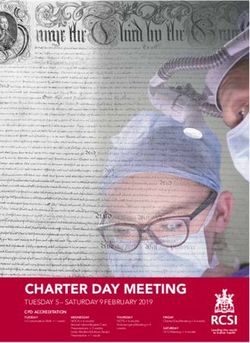

in the Trendelenburg position. threaded (fig. 1). The Task Force notes that the catheter-

over-the-needle technique may provide more stable ve-

3. Needle Insertion, Wire Placement, and Catheter Place-

nous access if manometry is used for venous confirmation.

ment. Needle insertion, wire placement, and catheter place-

The number of insertion attempts should be based on

ment includes (1) selection of catheter size and type, (2) use of a clinical judgment. The decision to place two catheters in a

wire-through-thin-wall needle technique (i.e., Seldinger tech- single vein should be made on a case-by-case basis.

nique) versus a catheter-over-the-needle-then-wire-through- 4. Guidance and Verification of Needle, Wire, and Catheter

the-catheter technique (i.e., modified Seldinger technique), (3) Placement. Guidance for needle, wire, and catheter placement

limiting the number of insertion attempts, and (4) introducing includes ultrasound imaging for the purpose of prepuncture

two catheters in the same central vein. vessel localization (i.e., static ultrasound) and ultrasound for

Case reports describe severe injury (e.g., hemorrhage, he- vessel localization and guiding the needle to its intended venous

matoma, pseudoaneurysm, arteriovenous fistula, arterial dis- location (i.e., real time or dynamic ultrasound). Verification of

section, neurologic injury including stroke, and severe or needle, wire, or catheter location includes any one or more of the

lethal airway obstruction) when there is unintentional ar- following methods: (1) ultrasound, (2) manometry, (3) pressure

terial cannulation with large bore catheters (Category B3 waveform analysis, (4) venous blood gas, (5) fluoroscopy, (6)

evidence).78 – 88 The literature is insufficient to evaluate continuous electrocardiography, (7) transesophageal echocardi-

whether the risk of injury or trauma is associated with the ography, and (8) chest radiography.

use of a thin-wall needle technique versus a catheter-over-

the needle technique (Category D evidence). The literature

is insufficient to evaluate whether the risk of injury or Guidance

trauma is related to the number of insertion attempts Static Ultrasound. Randomized controlled trials comparing

(Category D evidence). One nonrandomized comparative static ultrasound with the anatomic landmark approach for lo-

study reports a higher frequency of dysrhythmia when two cating the internal jugular vein report a higher first insertion

central venous catheters are placed in the same vein (right attempt success rate for static ultrasound (Category A3 evi-

internal jugular) compared with placement of one cathe- dence);90 findings are equivocal regarding overall successful can-

ter in the vein (Category B2 evidence); no differences in nulation rates (P ⫽ 0.025– 0.57) (Category C2 evidence).90 –92 In

carotid artery puncture (P ⫽ 0.65) or hematoma (P ⫽ addition, the literature is equivocal regarding subclavian vein

0.48) were noted (Category C3 evidence).89 access (P ⫽ 0.84) (Category C2 evidence) 93 and insufficient for

The consultants agree and the ASA members strongly femoral vein access (Category D evidence).

agree that the selection of catheter type (i.e., gauge, The consultants and ASA members agree that static ultra-

length, number of lumens) and composition (e.g., poly- sound imaging should be used in elective situations for pre-

urethane, Teflon) should be based on the clinical situa- puncture identification of anatomy and vessel localization

Anesthesiology 2012; 116:539 –73 545 Practice GuidelinesPractice Guidelines Fig. 1. Algorithm for central venous insertion and verification. This algorithm compares the thin-wall needle (i.e., Seldinger) technique versus the catheter-over-the needle (i.e., Modified-Seldinger) technique in critical safety steps to prevent uninten- tional arterial placement of a dilator or largebore catheter. The variation between the two techniques reflects mitigation steps for the risk that the thin-wall needle in the Seldinger technique could move out of the vein and into the wall of an artery between the manometry step and the threading of the wire step. ECG ⫽ electrocardiography; TEE ⫽ transesophageal echocardiography. when the internal jugular vein is selected for cannulation; Real-time Ultrasound. Meta-analysis of randomized con- they are equivocal regarding whether static ultrasound imag- trolled trials94 –104 indicates that, compared with the ana- ing should be used when the subclavian vein is selected. The tomic landmark approach, real-time ultrasound guided ve- consultants agree and the ASA members are equivocal re- nipuncture of the internal jugular vein has a higher garding the use of static ultrasound imaging when the fem- first insertion attempt success rate, reduced access time, oral vein is selected. higher overall successful cannulation rate, and decreased Anesthesiology 2012; 116:539 –73 546 Practice Guidelines

SPECIAL ARTICLES

rates of arterial puncture (Category A1 evidence). identifying the position of the catheter tip (Category B2 evi-

Randomized controlled trials report fewer number of dence). Randomized controlled trials indicate that continu-

insertion attempts with real-time ultrasound guided ous electrocardiography is effective in identifying proper

venipuncture of the internal jugular vein (Category A2 catheter tip placement compared with not using electrocar-

evidence).97,99,103,104 diography (Category A2 evidence).115,126,127

For the subclavian vein, randomized controlled trials report The consultants and ASA members strongly agree that

fewer insertion attempts with real-time ultrasound guided veni- before insertion of a dilator or large- bore catheter over a

puncture (Category A2 evidence),105,106 and one randomized wire, venous access should be confirmed for the catheter or

clinical trial indicates a higher success rate and reduced access thin-wall needle that accesses the vein. The Task Force be-

time, with fewer arterial punctures and hematomas compared lieves that blood color or absence of pulsatile flow should not

with the anatomic landmark approach (Category A3 evi- be relied upon to confirm venous access. The consultants

dence).106 agree and ASA members are equivocal that venous access

For the femoral vein, a randomized controlled trial re- should be confirmed for the wire that subsequently resides in

ports a higher first-attempt success rate and fewer needle the vein after traveling through a catheter or thin-wall needle

passes with real-time ultrasound guided venipuncture com- before insertion of a dilator or large-bore catheter over a wire.

pared with the anatomic landmark approach in pediatric The consultants and ASA members agree that, when feasible,

patients (Category A3 evidence).107 both the location of the catheter or thin-wall needle and wire

The consultants agree and the ASA members are equivocal that, should be confirmed.

when available, real time ultrasound should be used for The consultants and ASA members agree that a chest

guidance during venous access when either the internal radiograph should be performed to confirm the location of

jugular or femoral veins are selected for cannulation. The the catheter tip as soon after catheterization as clinically ap-

consultants and ASA members are equivocal regarding the propriate. They also agree that, for central venous catheters

use of real time ultrasound when the subclavian vein is placed in the operating room, a confirmatory chest radio-

selected. graph may be performed in the early postoperative period.

The ASA members agree and the consultants strongly agree

that, if a chest radiograph is deferred to the postoperative

Verification period, pressure waveform analysis, blood gas analysis, ultra-

Confirming that the Catheter or Thin-wall Needle Resides sound, or fluoroscopy should be used to confirm venous

in the Vein. A retrospective observational study reports that positioning of the catheter before use.

manometry can detect arterial punctures not identified by blood

flow and color (Category B2 evidence).108 The literature is insuf- Recommendations for Guidance and Verification of

ficient to address ultrasound, pressure-waveform analysis, blood Needle, Wire, and Catheter Placement

gas analysis, blood color, or the absence of pulsatile flow as The following steps are recommended for prevention of me-

effective methods of confirming catheter or thin-wall needle chanical trauma during needle, wire, and catheter placement

venous access (Category D evidence). in elective situations:

Confirming Venous Residence of the Wire. An observational

● Use static ultrasound imaging before prepping and

study indicates that ultrasound can be used to confirm venous draping for prepuncture identification of anatomy to

placement of the wire before dilation or final catheterization determine vessel localization and patency when the in-

(Category B2 evidence).109 Case reports indicate that transesoph- ternal jugular vein is selected for cannulation. Static

ageal echocardiography was used to identify guidewire position ultrasound may be used when the subclavian or femoral

(Category B3 evidence).110 –112 The literature is insufficient to vein is selected.

evaluate the efficacy of continuous electrocardiography in con-

● Use real time ultrasound guidance for vessel localization

firming venous residence of the wire (Category D evidence), al-

and venipuncture when the internal jugular vein is selected

though narrow complex electrocardiographic ectopy is recog-

for cannulation (see fig. 1). Real-time ultrasound may be

nized by the Task Force as an indicator of venous location of the

used when the subclavian or femoral vein is selected. The

wire. The literature is insufficient to address fluoroscopy as an

Task Force recognizes that this approach may not be fea-

effective method to confirm venous residence of the wire (Cat-

sible in emergency circumstances or in the presence of

egory D evidence); the Task Force believes that fluoroscopy may

other clinical constraints.

be used.

Confirming Residence of the Catheter in the Venous Sys- ● After insertion of a catheter that went over the needle or a

tem. Studies with observational findings indicate that fluo- thin-wall needle, confirm venous access.†† Methods for

confirming that the catheter or thin-wall needle resides in

roscopy113,115 and chest radiography115–125 are useful in

the vein include, but are not limited to, ultrasound, ma-

†† For neonates, infants, and children, confirmation of venous nometry, pressure-waveform analysis, or venous blood gas

placement may take place after the wire is threaded. measurement. Blood color or absence of pulsatile flow

Anesthesiology 2012; 116:539 –73 547 Practice GuidelinesPractice Guidelines

should not be relied upon for confirming that the catheter nonsurgically, as follows: 54.9% (for neonates), 43.8% (for in-

or thin-wall needle resides in the vein. fants), and 30.0% (for children). SPA members indicating that

● When using the thin-wall needle technique, confirm the catheter may be nonsurgically removed without consulta-

venous residence of the wire after the wire is threaded. tion is as follows: 45.1% (for neonates), 56.2% (for infants), and

When using the catheter-over-the-needle technique, 70.0% (for children). The Task Force agrees that the anesthesi-

confirmation that the wire resides in the vein may not be ologist and surgeon should confer regarding the relative risks

needed (1) when the catheter enters the vein easily and and benefits of proceeding with elective surgery after an arterial

manometry or pressure waveform measurement pro- vessel has sustained unintended injury by a dilator or large-bore

vides unambiguous confirmation of venous location of catheter.

the catheter; and (2) when the wire passes through the Recommendations for Management of Arterial Trauma or

catheter and enters the vein without difficulty. If there is Injury Arising from Central Venous Access. When unin-

any uncertainty that the catheter or wire resides in the tended cannulation of an arterial vessel with a dilator or

vein, confirm venous residence of the wire after the wire large-bore catheter occurs, the dilator or catheter should

is threaded. Insertion of a dilator or large-bore catheter be left in place and a general surgeon, a vascular surgeon,

may then proceed. Methods for confirming that the wire or an interventional radiologist should be immediately

resides in the vein include, but are not limited to, ultra- consulted regarding surgical or nonsurgical catheter re-

sound (identification of the wire in the vein) or trans- moval for adults. For neonates, infants, and children the

esophageal echocardiography (identification of the wire decision to leave the catheter in place and obtain consul-

in the superior vena cava or right atrium), continuous tation or to remove the catheter nonsurgically should be

electrocardiography (identification of narrow-complex based on practitioner judgment and experience. After the

ectopy), or fluoroscopy. injury has been evaluated and a treatment plan has been

● After final catheterization and before use, confirm resi- executed, the anesthesiologist and surgeon should confer

dence of the catheter in the venous system as soon as regarding relative risks and benefits of proceeding with the

clinically appropriate. Methods for confirming that the elective surgery versus deferring surgery to allow for a pe-

catheter is still in the venous system after catheterization riod of patient observation.

and before use include manometry or pressure wave-

form measurement.

● Confirm the final position of the catheter tip as soon as Appendix 1: Summary of

clinically appropriate. Methods for confirming the position of Recommendations

the catheter tip include chest radiography, fluoroscopy, or

Resource Preparation

continuous electrocardiography. For central venous catheters

placed in the operating room, perform the chest radiograph ● Central venous catheterization should be performed in an envi-

no later than the early postoperative period to confirm the ronment that permits use of aseptic techniques.

position of the catheter tip. ● A standardized equipment set should be available for central ve-

nous access.

● A checklist or protocol should be used for placement and main-

IV. Management of Arterial Trauma or Injury Arising

tenance of central venous catheters.

from Central Venous Catheterization

● An assistant should be used during placement of a central venous

Case reports of adult patients with arterial puncture by a catheter.

large bore catheter/vessel dilator during attempted central

venous catheterization indicate severe complications (e.g., Prevention of Infectious Complications

cerebral infarction, arteriovenous fistula, hemothorax) af-

• For immunocompromised patients and high-risk neonates,

ter immediate catheter removal; no such complications

administer intravenous antibiotic prophylaxis on a case-by-

were reported for adult patients whose catheters were left case basis.

in place before surgical consultation and repair (Category

䡩 Intravenous antibiotic prophylaxis should not be adminis-

B3 evidence).80,86 tered routinely.

The consultants and ASA members agree that, when unin- • In preparation for the placement of central venous catheters, use

tended cannulation of an arterial vessel with a large-bore cathe- aseptic techniques (e.g., hand washing) and maximal barrier pre-

ter occurs, the catheter should be left in place and a general cautions (e.g., sterile gowns, sterile gloves, caps, masks covering

surgeon or vascular surgeon should be consulted. When unin- both mouth and nose, and full-body patient drapes).

tended cannulation of an arterial vessel with a large-bore cathe- • A chlorhexidine-containing solution should be used for skin

ter occurs, the SPA members indicate that the catheter should be preparation in adults, infants, and children.

left in place and a general surgeon, vascular surgeon, or inter- 䡩 For neonates, the use of a chlorhexidine-containing solution

ventional radiologist should be immediately consulted before for skin preparation should be based on clinical judgment and

deciding on whether to remove the catheter, either surgically or institutional protocol.

Anesthesiology 2012; 116:539 –73 548 Practice GuidelinesSPECIAL ARTICLES

䡩 If there is a contraindication to chlorhexidine, povidone-io- 䡩 In adults, selection of an upper body insertion site should

dine or alcohol may be used as alternatives. be considered to minimize the risk of thrombotic

䡩 Unless contraindicated, skin preparation solutions should complications.

contain alcohol. • When clinically appropriate and feasible, central venous access in

• If there is a contraindication to chlorhexidine, povidone-iodine the neck or chest should be performed with the patient in the

or alcohol may be used. Unless contraindicated, skin preparation Trendelenburg position.

solutions should contain alcohol. • Selection of catheter size (i.e., outside diameter) and type

• Catheters coated with antibiotics or a combination of chlo- should be based on the clinical situation and skill/experience

rhexidine and silver sulfadiazine should be used for selected of the operator.

patients based on infectious risk, cost, and anticipated dura- 䡩 Selection of the smallest size catheter appropriate for the

tion of catheter use. clinical situation should be considered.

䡩 Catheters containing antimicrobial agents are not a substi- • Selection of a thin-wall needle (a wire-through-thin-wall-needle,

tute for additional infection precautions. or Seldinger) technique versus a catheter-over-the-needle (a cath-

eter-over-the-needle-then-wire-through-the-catheter, or Modi-

• Catheter insertion site selection should be based on clinical

fied Seldinger) technique should be based on the clinical situation

need.

and the skill/experience of the operator.

䡩 An insertion site should be selected that is not contami-

䡩 The decision to use a thin-wall needle technique or a cath-

nated or potentially contaminated (e.g., burned or infected

eter-over-the-needle technique should be based at least in

skin, inguinal area, adjacent to tracheostomy or open sur-

part on the method used to confirm that the wire resides in

gical wound).

the vein before a dilator or large-bore catheter is

䡩 In adults, selection of an upper body insertion site should threaded.

be considered to minimize the risk of infection. 䡩 The catheter-over-the-needle technique may provide

• The use of sutures, staples, or tape for catheter fixation should be more stable venous access if manometry is used for venous

determined on a local or institutional basis. confirmation.

• Transparent bio-occlusive dressings should be used to protect • The number of insertion attempts should be based on clinical

the site of central venous catheter insertion from infection. judgment.

䡩 Unless contraindicated, dressings containing chlorhexidine • The decision to place two catheters in a single vein should be

may be used in adults, infants, and children. made on a case-by-case basis.

䡩 For neonates, the use of transparent or sponge dressings • Use static ultrasound imaging in elective situations before prep-

containing chlorhexidine should be based on clinical judg- ping and draping for prepuncture identification of anatomy to

ment and institutional protocol. determine vessel localization and patency when the internal jug-

• The duration of catheterization should be based on clinical ular vein is selected for cannulation.

need. 䡩 Static ultrasound may be used when the subclavian or femoral

䡩 The clinical need for keeping the catheter in place should be vein is selected.

assessed daily. • Use real-time ultrasound guidance for vessel localization and

䡩 Catheters should be removed promptly when no longer venipuncture when the internal jugular vein is selected for

deemed clinically necessary. cannulation.

• The catheter insertion site should be inspected daily for signs of 䡩 Real-time ultrasound may be used when the subclavian or

infection. femoral vein is selected.

䡩 Real-time ultrasound may not be feasible in emergency

䡩 The catheter should be changed or removed when catheter

circumstances or in the presence of other clinical

insertion site infection is suspected.

constraints.

• When a catheter-related infection is suspected, replacing the

• After insertion of a catheter that went over the needle or a

catheter using a new insertion site is preferable to changing the thin-wall needle, confirm venous access.††

catheter over a guidewire.

䡩 Methods for confirming that the catheter or thin-wall nee-

• Catheter access ports should be wiped with an appropriate anti- dle resides in the vein include, but are not limited to: ultra-

septic before each access when using an existing central venous sound, manometry, pressure-waveform analysis, or venous

catheter for injection or aspiration. blood gas measurement.

• Central venous catheter stopcocks or access ports should be 䡩 Blood color or absence of pulsatile flow should not be relied

capped when not in use. upon for confirming that the catheter or thin-wall needle

• Needleless catheter access ports may be used on a case-by-case resides in the vein.

basis. • When using the thin-wall needle technique, confirm venous res-

idence of the wire after the wire is threaded.

• When using the catheter-over-the-needle technique, confir-

Prevention of Mechanical Trauma or Injury mation that the wire resides in the vein may not be needed (1)

• Catheter insertion site selection should be based on clinical need when the catheter enters the vein easily and manometry or

and practitioner judgment, experience, and skill. pressure waveform measurement provides unambiguous con-

Anesthesiology 2012; 116:539 –73 549 Practice GuidelinesYou can also read