Mungbean: A Preview of Disease Management Challenges for an Alternative U.S. Cash Crop

←

→

Page content transcription

If your browser does not render page correctly, please read the page content below

Journal of Integrated Pest Management, (2022) 13(1): 4; 1–21

https://doi.org/10.1093/jipm/pmab044

Profile

Mungbean: A Preview of Disease Management Challenges

for an Alternative U.S. Cash Crop

J. C. Batzer,1, A. Singh,2 A. Rairdin,2 K. Chiteri,2 and D. S. Mueller1,3

1

Department of Plant Pathology and Microbiology, Iowa State University, Ames, IA, 50011, USA, 2Department of Agronomy, Iowa

State University, Ames, IA, 50011, USA, and 3Corresponding author, e-mail: dsmuelle@iastate.edu

Subject Editor: Nathan Walker

Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/jipm/article/13/1/4/6524412 by guest on 20 June 2022

Received 7 July 2021; Editorial decision 13 December 2021

Abstract

Mungbean (Vigna radiata L. Wilczek) products and other plant-based protein sources exceeded $1 billion in U.S. sales

during 2020. Nearly all of the mungbean consumed in the U.S. is imported, but it has considerable potential as

a domestic crop. Its tolerance of drought and high temperatures gives U.S. farmers additional options for crop

rotation. Mungbean is a short-season crop (60 to 90 d). It fits the current infrastructure of equipment, chemical,

inputs, and storage for soybean and has a developed market. Similar to other crops, vulnerability to diseases can

be a constraint for mungbean production. This manuscript reviews mungbean diseases causing significant yield

losses in current production regions and current control options. This information will provide a useful guide to

breeders and farmers to develop and produce a profitable crop, and will also equip university extension personnel

with essential information to assist mungbean farmers with disease management.

Key words: Vigna, grain legume, pulse crop, fungi, virus

There is growing interest in producing mungbean (Vigna radiata Easily digestible mungbean is free from flatulent effects and is hypo-

L. Wilczek) subfamily Papilinoidae and family Leguminoseae in allergenic (Dahiya et al. 2015). Thus, mungbean is widely fed to ba-

North America (Quazaz et al. 2019), driven by consumer demand bies, convalescents, and elders (Quazaz et al. 2019). Mungbean seeds

for plant-based protein foods (Hirtzer et al. 2021, King 2020). are 21 to 31% protein by weight, with amino acid profiles similar to

Consumer preferences composed of pea (Pisum sativum L.), soy- other beans and complementary to cereal grains. Mungbean is also

bean (Glycine max (L.) Merr.), and mungbean have been steadily valued for its high levels of vitamins and minerals, folate, and iron

growing. U.S. sales of plant-based meats totaled $939 million in (Keatinge et al. 2011). Mungbean has been heralded as a future crop

2019 and was projected to exceed $1 billion in 2020 (Robinson and of pharmacological importance, as well as anti-inflammatory and

Mulvany 2020). A plant-based burger requires 75% less water, 95% anti-oxidant effects (Dahiya et al. 2015, Hall et al. 2017, Hou et al.

less land, and produces roughly 87% fewer greenhouse gas emis- 2019, Sehrawat et al. 2020).

sions than a beef patty, according to Impossible Foods, a plant-based U.S. imports of mungbean in the first two quarters of 2021 in-

commercial food producer (Jones 2020). The “bleeding” vegetable creased by 62% compared to that of 2020 (NASS 2021). In 2020,

burger substitute made by “Beyond Meat” is largely comprised of 31 million kg (equivalent to $45 million) of mungbean seed were

pea and mungbean, according to the product website and founder imported to the U.S., mostly from China (NASS 2021). Global

Ethan Brown (NPR 2017, Brown 2021). It is now on the menu of mungbean production area is about 7.3 million ha and average yield

dozens of national restaurant chains, in addition to chicken, sausage, is 721 kg/ha (Bindumadhava et al. 2017). While the U.S. appetite

and bacon substitutes (Bendix 2019). The McPlant was also devel- for mungbean is expanding, consumption worldwide from 1982 to

oped for McDonald’s using mungbean products in cooperation with 2006 increased by >60% (Shanmugasundaram et al. 2009). India

Beyond Meat producers (Halzack 2020). Mungbean is also a key and Myanmar each account for 30% of global output (Pandey et al.

ingredient in a vegan egg product, which is produced by Eat JUST 2018). India followed by China are the world’s largest producers

and sold at national grocery chains and served at hundreds of uni- of mungbean (Sun et al. 2016, Nair and Schreinemachers 2020).

versities, corporate cafeterias, and restaurants. As of August 2019, Mungbean production is fully mechanized in Australia, where in

Eat JUST had sold the plant-based equivalent of more than 17 mil- 2020, 125,000 ha were planted and $180 million was exported to

lion chicken eggs (Shoup 2019). Asia, North America, Europe, and the Middle East (Clarry 2016,

High-quality protein from whole and processed seeds is used AMA 2020).

for sprouts, soups, transparent noodles, bean paste, beverages, ice Mungbean has shown potential to complement the existing

creams, noodles, and desserts (Nair and Schreinemachers 2020). Midwest U.S. corn (Zea mays L.) and soybean rotation as a cover crop,

© The Author(s) 2022. Published by Oxford University Press on behalf of Entomological Society of America.

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/),

1

which permits unrestricted reuse, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.2 Journal of Integrated Pest Management, 2022, Vol. 13, No. 1

intercrop, or rotation crop (Zougmore et al. 2000, Kayani et al. 2010, Kumar et al. 2013). Mungbean is a pulse crop which is also known

Anas et al. 2017, Saima et al. 2018, Syafruddin 2020). Mungbean as mung bean, green gram, golden gram, moong, Chickasaw pea,

was first grown in the U.S. in 1835 (Nair and Schreinemachers 2020). Oregon pea, and chop suey bean. The seed of mungbean can be

It can be used as an alternative crop in dryland farming systems in the bright green or golden, shiny or dull (Fig. 1). Mungbean cultivars

western U.S. plains (Ghanbari and Javan 2015, Sunayana and Yadava vary in seed size, from 25,000 to 30,000 seeds/kg (Singh et al.

2016, Henning and Killan 2017). From 2019 to 2020 U.S. crop 2017b). Medium-sized, shiny seeds have higher market value (Singh

values of pulses increased by 30% and harvested acres increased by et al. 2017b). Vigna mungo L. is similar to mungbean, but with a

10% (mungbean is included with dry beans, peas, lentils in USDA black seed, also referred to as urd bean or black gram (Clarry 2016).

reports) (NASS 2021). Exports increased by 16%, while per capita There are 98 species in the genus Vigna (Kang et al. 2014), of these

availability decreased by 7%. Production costs of mungbean are mungbean is the most important grain legume.

similar to soybean, but differ in postharvest cleaning and transporta- Mungbean is day-neutral and takes as few as 55 d from sowing

tion costs (Myers 2003). Although mungbean is mostly consumed by to harvest if average temperature is above 20°C (Clarry 2016), al-

humans, sometimes the crop is plowed under as green manure, and it though high-yielding cultivars often require 85–90 d (Mehandi

has also been used for beef cattle forage (Myers 2003). Split, cracked et al. 2019) and traditional cultivars reach maturity in 90–110 d

seed and other material left after cleaning mungbean is often fed to (Humphry et al. 2003). Mungbean has good potential for double

Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/jipm/article/13/1/4/6524412 by guest on 20 June 2022

livestock in place of soybean. cropping after wheat or canola, if planted before July in the South

Mungbean is vulnerable to numerous destructive diseases. Central Plains of the U.S. (Myers 2003). It has a taproot that can

Disease losses are blamed as the main biotic limitation to yield access moisture to a 90 cm soil depth if compaction is not present

(Iqbal et al. 2014). The “Alternative Field Crops Manual” gives U.S. (GDRC 2018). While mungbean thrives on deep or sandy loam soils,

Midwest farmers seeding, fertility, and harvest recommendations, it also grows well in a wide range of soil types (Cumming 2014,

but does not consider specific diseases or control measures (Oplinger Moore et al. 2014). Seed germination requires a minimum soil tem-

et al. 1997). Pandey et al. (2018) and Naimuddin et al. (2016) pro- perature of 10.5°C (Kumar et al. 2013). A seeding depth of 2.5 to

vide reviews for fungal, bacterial, and viral disease management of 4.0 cm is recommended for most soils (Myers 2003, GDRC 2018).

mungbean in major growing areas of South Asia. We have drawn Mungbean plants have alternately arranged trifoliate leaves similar

on a wide breadth of resources. For example, the “International to soybean, but plants are slightly smaller (Fig. 1). Plants may grow

Mungbean Improvement Network” (IMIN) established in 2016, from 38 to 127 cm tall, depending on cultivar, and stop increasing

focuses on genetic resource collection. Annual IMIN meeting re- in height once flowering has begun (Cumming 2014, Sunayana and

ports are summarized in the Mung Central newsletter (https://avrdc. Yadav 2016) (Fig. 1). Missouri growers were advised to plant from late

org/wpfb-file/008_mung-central-pdf/). The “Grains Research and May through mid-June at a seeding rate of 16.8–22 kg/ha, depending

Development Corporation” (GRDC) conducts a wide range of re- on row width (Myers 2003). Plant growth is optimal at 28–30°C

search and extension resources for Australian farmers and has pro- (Kumar et al. 2013). Vegetative and reproductive growth stages of

duced an exhaustive manual for mungbean growers (GRDC 2018). mungbean are akin to soybean in that they range from emergence at

The National Agricultural Research Organization (NARO) has a VE to physiological maturity at R7 (Clarry 2016 (Fig. 1)). Greenish

manual for mungbean that includes recommendations for sowing, to bright yellow flowers are clustered at the leaf axils and continue

fertilizer, management of weeds, insects, and diseases, threshing and to bloom for a few to several weeks (Fig. 1). The flowers are pre-

storage (Mbeyagala et al. 2017). dominately self-pollinated, a process that occurs at night (Cumming

Our aim is to both familiarize North American farmers about 2014). About 20 d after flowering, plants develop 20–30 pods that

mungbean and discuss the disease management considerations re- turn tawny brown to black upon reaching maturity (Cumming 2014)

quired for the production of this “new to America” crop. This article (Fig. 1). Pods are 5–13 cm long and hold 8–20 seeds. Leaves may dry,

compiles information targeted to North American farmers who are but do not always drop off by seed maturity. Seed is harvested in early

considering mungbean as part of their crop rotation. Beyond a sum- to mid-September in Oklahoma (Myers 2003).

mary of this unfamiliar crop, the disease portion of this review is Mungbean plants are widely naturalized across South Asia,

organized by plant part, beginning with soilborne seedling and root as evidenced by their occurrence at archeological sites in that

diseases, followed by vascular diseases, and finally foliar mungbean region(Chavhan et al. 2018). India has contributed greatly to geno-

diseases. Prevalent disease pathogens are described for each group. type collections and modern cultivars (Mehandi et al. 2019, Dikshit

A “North American Farmers” section follows each group of patho- et al. 2020). However, relatively few parental lines are available.

gens that speculates how mungbean production may be impacted Mungbean breeding efforts in the U.S. have been minimal. Only three

by these diseases. Since management approaches are often similar decades-old-varieties of mungbean (Berken, Satin, and Oklahoma

across each group of diseases, a management section is presented 2000) are available to U.S. farmers. The USDA, Plant Genetic

following descriptions of pathogens. Resources Conservation Unit, Griffin, Georgia, has wild nonadapted

This information will create a baseline for North American and diverse germplasm lines available to breeders. Current breeding

farmers, breeders, and agribusiness professionals when consid- efforts focus on 1) plant traits, such as growth habit, pigmenta-

ering whether to invest time, energy, and money in this intriguing tion, leaf traits, pubescence, inflorescence type and color, and pod

alternative crop. It will also equip university extension personnel color (Fig. 1); 2) management traits, such as herbicide and disease

with essential information to assist mungbean farmers with disease resistance, early sowing time, photoperiod response, tolerance to

management. drought and waterlogging, and flower abortion; and 3) marketable

characteristics, such as seed size, seed coat, seed hardness, and color

(Ghanbari and Javan 2015, Sunayana and Yadav 2016, Singh et al.

Mungbean

2017, Mogali and Hegde 2020). Reference genomes of cultivated

The Crop mungbean VC1973A and a wild relative of mungbean (V. radiata

Mungbean and cowpea (Vigna unguiculata L. Fabaceae) are among var. sublobata) provide a framework for mungbean genetic and

the few drought-tolerant legume grains (Kumar and Sharma 2009, genome research (Lambrides and Goodwin 2007, Kim et al. 2015).Journal of Integrated Pest Management, 2022, Vol. 13, No. 1 3

Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/jipm/article/13/1/4/6524412 by guest on 20 June 2022

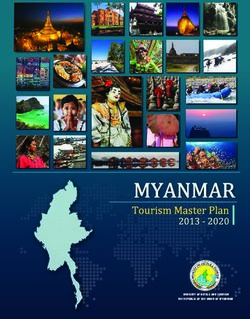

Fig. 1. Plant stages across growing season (early June to early September) of several mungbean genotypes grown in breeding plots in Ames, Iowa, U.S. A. First

true leaves are unifoliate, vegetative stage (VC) B. Trifoliate leaves are produced during the vegetative stage. These V5 plants have 5 nodes. C–D. Leaf-shape

can be lobed or nonlobed. E. Yellow or green flowers are produced on the top of the plant and are self-pollinated at night; appearance of flowers starts the

reproductive stage 1 (R1). E–F. Pods are formed in clusters; full bloom is reproductive stage 2 (R2). G. Several branches have pods which elongate as seeds

develop; full pod is reproductive stage 4 (R4) H. Mungbean pods mature between 60 to 90 d after planting, depending on variety, and change from green to

black or brown, reproductive stage 7 (R7); leaves may dry, but do not drop. I–K. Seed varies from yellow, black to green, can be dull or shiny, and ranges in size

(2-5mm in diameter).

Hundreds of experimental lines of mungbean have been tested in the (Sandhu and Singh 2020). Mungbean cultivars suited for production

U.S. at Texas A&M University, Oklahoma State University, and the in the Central U.S. will be available in 2023 (Singh, unpublished).

University of Missouri (Oplinger et al. 1997). Mungbean germplasm Based on phenotyping work at Iowa State University, an extension

suitable for Midwest and Southeast U.S. production is being tested bulletin “Green Gram and Black Gram: Small Grain Legume Crops

and new cultivars are being developed in Iowa and Tennessee for the Midwestern United States” (Singh et al. 2008) explains the4 Journal of Integrated Pest Management, 2022, Vol. 13, No. 1

breeding program. Thus, as farmers to begin produce mungbean, ex- Sustainable disease management of mungbean should exploit a

tension and agronomic professionals will need to provide disease range of tools as part of an integrated pest management (IPM) pro-

management recommendations for their regional farmers. gram. Cultural methods are the first line of defense. Cultural prac-

tices relating to planting time, soil preparation, removal of diseased

plants and alternative hosts, plant residue management, clean seed,

Disease Threats to Mungbean Production

and crop rotation are essential for a healthy crop. Software known

Overview of Management Strategies as Agriculture Production System Simulator (APSIM) is used to esti-

Many reports have been published on management of mungbean mate the risk of tactical decisions for a crop; APSIM is being adapted

diseases across the world, but few reports are based on research for mungbean in Australia (Holzworth et al. 2018). This software

conducted in North America. More than 20 of the 27 documented aims to predict the impact of climate on yield gaps of dryland crops

mungbean diseases have been reported in China (Sun et al. 2020a). (Rodriguez et al. 2018). Inputs for the APSIM-mungbean model in-

Since there are few cultivars suitable for the Midwest and there is no clude cardinal temperatures of 7.5°C base, 30°C optimum and 40°C

commercial production, integrated disease management practices have maximum, and a total of 1,200-degree days from sowing to maturity

not been developed for this region. Below, we have grouped diseases (Collins and Anderson 2019). By linking climate forecasts to a spe-

into those affecting seedlings and roots, vascular system, and foliage cific APSIM-crop model, growers can fine-tune their “crop design”

Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/jipm/article/13/1/4/6524412 by guest on 20 June 2022

(Table 1). Nearly all disease identification and management strategies to optimize yield. For example, adjustments can be made to sowing

have been developed for South Asia, sub-Saharan Africa, and Australia. times, planting density, row configuration, soil type, or fertilizer ap-

The “North American Farmers” section will focus on how this valu- plication (Rodriguez et al. 2018). Since weather plays an important

able information may impact American and Canadian farmers. factor in the disease triangle of host, pathogen, and environment, the

Table 1. Widely known mungbean diseases, symptoms, causal agents, disease distribution, management recommendations, and refer-

ences classified by disease type

Disease Common name, (causal agents) Symptoms Mungbean Management recommendations References

type growing regions

with high preva-

lence

Root/

Stem

Nema- Root knot Root galls, wilting, re- Africa, Asia, Resistance, seed treatments, crop rota- GRDC 2018,

todes nematode,(Meloidogynespp). duced vigor Australia tion with grain Hassan and

Devi 2004,

Singh and

Prasad 2016,

Stirling et al.

2006

Reniform nematode Stunting, reduced vigor Asia Seed treatments, Dayal and

(Rotylenchulus reniformis), crop rotation with grain Sharman 2007

cyst nematode

(Heterodera cajani),

Fungi Dry root rot, charcoal rot, Seedlings with dark Africa, Asia, Favored by warm, dry soils. Addition of Athira 2017,

carbon rot (Macrophomina lesions; postflowering Australia organic matter, foliar fungicides, seed Kumari

phaseolina) plants with reddish- treatments with carbendazim and et al. 2012,

brown lesions on thiophanate methyl, bioagent seed Mbeyagala

roots and stems, dressing and soil drenching using et al. 2017,

scattered black neem cake, trichoderma sp. Pseudo- Thilagavath

microsclerotia monas fluorescens, crop roation with et al. 2007

nonhost cereal crops

Wet root rot, web blight (Rhiz- Reddish-brown lesions Africa, Amer- Row spacing, planting time, fungicidal Basandrai et al.

octonia solani) at or below the soil icas, seed and foliar treatments, suppres- 2016, Dubey

level; Asia, sive soils, bioagent seed dressing, soil et al. 2011,

Web blight, above Australia drenching Singh et al.

ground rot,spiderweb- Favored by 2008

like growth with warm, wet

microsclerotia. conditions.

Fusarium wilt (Fusarium Root rot and vascular Northern Aus- Resistance, crop rotation with grain, Kelly 2017, Iqbal

oxysporum f. sp., wilt tralia, Can- avoid excessively wet soils et al. 2019

F.solani) ada, China,

Northern

India and

Pakistan

Collar rot, southern blight Foliage yellowing, Worldwide Soil solarization, organic amendments, Yaqub and

(Sclerotium rolfsii) girdling stem lesions seed-pelleting with Trichoderma Shahzad. 2008,

at soil line harzianum 2009.Journal of Integrated Pest Management, 2022, Vol. 13, No. 1 5

Table 1. Continued

Disease Common name, (causal agents) Symptoms Mungbean Management recommendations References

type growing regions

with high preva-

lence

Foliar

Virus Mungbean yellow mosaic Yellow mosaic, wilt, Africa, Asia Resistance. Control of whitefly vector Akbar et al.

virus, horsegram yellow mo- yellow-spotted pods using trap crops (marigold, and 2019, Biswas

saic virus, dolichos yellow sticky traps; seed treatment with et al. 2012,

mosaic virus imidacloprid or thiomethoxam; foliar 2017, Khaliq

spray with imidacloprid, neem oil, et al. 2017,

or oxydemton methyl; early season Mbeyagala

roguing, planting time to avoid white et al. 2017,

flies Naimuddin

et al. 2016

Goundnut bud necrosis virus Bud necrosis, yellowing, India Control of thrips vector Sreekanth et al.

Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/jipm/article/13/1/4/6524412 by guest on 20 June 2022

distortion, ringspots, 2004

stunting

Leaf crinkle virus Leaf crinkle, stunting, South and Clean seed, early season roguing, bar- Sastry 2013

stem thickening, en- Southeast rier crops, resistance

larged leaves Asia

Bean common mosaic virus, Mosaic, dwarfing, Africa, Asia Virus detection, aphid control, clean Lee et al. 2017,

bean common mosaic necro- chlorosis,deformation, seed Worrall et al.

sis virus leaf curling. 2015

Bac- Halo blight Round, dark-brown, Africa, China, Removal of alternative hosts, disease- Noble et al. 2019

teria (Pseudomonas savastanoi pv. water-soaked lesions, Australia. free seed

phaseolicola) chlorotic halos Favored by cool

temperatures.

Bacterial leaf spot Irregular necrotic spots Africa, Asia Resistance, clean seed, seed dressings Dutta et al. 2005,

(Xanthomonas axonopodis with a thin halo, leaf Favored by arid, containing antagonistic bacteria, Kumar 2016

pv. vignaeradiatae) blight, discolored seed warm condi- or copper, streptomycin, neem leaf

tions. extract

Tan spot/ bacterial wilt. Water-soaked lesions Australia, Africa Clean seed,seed dressings Mbeyagala et al.

(Curtobacterium and leaf scorch, flac- containingstreptomycin, copper sul- 2017, Schwartz

flaccumfacienspv. cidity, discolored seed phate, oxytetracycline 2007

flaccumfaciens)

Fungi Powdery mildew (Erysiphe White floury upper leaf Cool dry season. Timely fungicide sprays Mancozeb, Rakhonde, et al,

polygoni, E. vignae, surface Africa, wettable sulfur, carbendazim, 2001, Kelly

Sphaerotheca phaseoli, Asia,Australia thiophanate methyl, and dinocap. et al. 2021,

Podosphaera fusca Neem oil, resistance Mbeyagala

P. xanthii) et al. 2017,

Yadav et al.

2014

Cercospora leaf spot Leafspots first brown, Africa, India, Early planting time, early detection, Bhat et al. 2014,

(Cercospora cruenta, water-soaked, later fungicide spray containing QoI, with Kavyashree and

C. canescens, become irregular dry, carbendazim or mancozeb, resistance Yadahalli

C. caracallae) gray with narrow red- 2016, Joshi

dish margins et al. 2006,

Mbeyagala

et al. 2017

Anthracnose Irregular dark water- Asia, Fungicide seed treatments, foliar fungi- Chaudhari

(Colletotrichumdestructivum soaked spots, orange Sub-Saharan cide sprays, crop rotation, resistance et al. 2016,

species complex, margins, shot holes, Africa Chankaew

C. lindemuthianum, defoliation et al. 2013,

C. truncatum) Shukla et al.

2014, Kumar

et al. 2020

Alternaria leafspot (Alternaria Concentric circles on Asia Timely fungicide sprays when symp- Maheshwari and

alternata) leaf undersides toms are first detected Krishna 2013

Ascochyta blight (Didymella Brown concentric rings, Asia Rotation. Timely fungicide sprays when Ahmed et al.

rabiei) dark margins with symptoms are first detected 2017, Chang

small black specks et al. 2007,

Iqbal et al.

20196 Journal of Integrated Pest Management, 2022, Vol. 13, No. 1

decision to use a seed treatment, change planting date, or choose a North American Farmers. There is a need to assess the impact of

disease-resistant cultivar may reduce risk and optimize yield. reniform and cyst nematodes on North American mungbean culti-

Disease-resistant plants are a key weapon for disease manage- vars, since soybean are hosts to these parasites (Usovsky et al. 2021).

ment. A number of disease-resistant mungbean lines have been de- North American mungbean farmers will likely experience prob-

veloped for Africa, Asia, and Australia (Chueakhundthod 2019). lems with Heterodera sp. (cyst) nematodes. Soybean cyst nematode

“Berken” (one of three varieties available in the U.S.) shows sus- (Heterodera glycines) was reported in Canada mungbean cultivar

ceptibility to several pathogens (Ryley and Tatnell 2011). Efforts to trials (Park and Anderson 1997). The southern root-knot nematode

assess or develop mungbean cultivars that are adapted to the tem- (Meloidogyne incognita) may impact mungbean production in the

perate Midwest U.S. climate are underway in Montana and Iowa southern and mid-Atlantic regions of the U.S., while the northern

(Henning and Kilian 2017, Sandhu and Singh 2020) and new culti- root-knot nematode (Meloidogyne hapla) may impact the Midwest.

vars should be available for the 2023 growing season. For example, legumes in Wyoming (42°N latitude) are host to

Other management methods presented include the use of syn- M. hapla (Griffin and Jensen 1997).

thetic fungicides, botanical extracts, bio-fungicides, and host defense

activators (Pandey et al. 2018, Nair et al. 2019). Knowledge of the Management of Nematodes in Mungbean

ecology and etiology of specific pathogens will aid in disease preven- The most effective management tactics for nematode control on

Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/jipm/article/13/1/4/6524412 by guest on 20 June 2022

tion, but regular scouting can help farmers with early detection and mungbean are disease-resistant cultivars (Hassan and Devi 2004,

provide more options to suppress disease losses. Singh and Prasad 2016) and botanical seed dressings, such as neem

Production of mungbean in North America will likely require and oilseed cakes (Dayal and Sharman 2007). Growing sorghum,

different disease management strategies than those used in sub- small grains, grasses, or leaving a clean summer fallow between

tropical and tropical regions where most mungbean is grown. In crops can reduce the nematode populations and should be routinely

Ontario, Canada, for example, on sites with heavy clay soils, root incorporated into the cropping sequence (Stirling et al. 2006, Mohler

and crown rot caused by Rhizoctonia solani and late season wilt and Johnson 2009). Interestingly, rotation to mungbean was highly

associated with Fusarium oxysporum were limiting factors for com- effective for reducing root-lesion nematode on wheat (Pratylenchus

mercial mungbean production (Anderson 1985, Olson et al. 2014). thornei; Owen et al. 2014).

Although the charcoal rot pathogen (Macrophomina phaseolina)

was isolated from fields in Canada, disease symptoms were not re-

Fungi and Oomycetes

ported (Anderson 1985). Although mungbean is not widely grown

The mycelia of fungi are composed of chitin, while the mycelia

in North America, there are scant reports of disease occurrence in

of oomycetes are composed of cellulose, and are descended from

Canada and the U.S. that are not reported in subtropical and trop-

blue-green algae (Sharma 2005). Damping-off diseases reduce

ical regions. White mold (Sclerotinia sclerotiorum (Lib.) de Bary was

mungbean stand count by rotting seeds or attacking emerging seed-

reported as a serious threat to mungbean in field trials conducted in

lings as they germinate. Root rot pathogens enter through root hairs

Ontario, Canada (Tu and Zheng 1997). Common bacterial blight

and wounds, and may invade the vascular system, resulting in low

symptoms were noted in a mungbean evaluation in western Canada

plant vigor, wilting, and death (Bodah 2017).

(Olson et al. 2011). Sentinel field plots in Iowa, 2020 and 2021 de-

tected frogeye leafspot (Cercospora sojina), Rhizoctonia crown rot,

Dry root rot, charcoal rot, and carbon rot are caused by

and sudden death syndrome (Fusarium virguliforme O’Donnell &

Macrophomina phaseolina (Tassi) Goid (formerly known as

T. Aoki) (Batzer, unpublished). Flowering and pod fill require ad-

Rhizoctonia bataticola) (Iqbal and Mukhtar 2014); in mungbean

equate rainfall, but high humidity and excess rainfall in the late

Macrophomina causes dry root rot, while in soybean Macrophomina

season may result in disease problems in the Midwest U.S. (Oplinger

causes charcoal rot. Dry root rot symptoms on seedlings appear as

et al. 1997). To date, U.S. mungbean farmers lack sufficient regis-

dark lesions on epicotyls and hypocotyls that obstruct xylem vessels

tered pesticides and growing recommendations to ensure dependable

(Iqbal and Mukhtar 2014). In postflowering plants, the disease ap-

harvests.

pears as reddish-brown lesions on roots and stems, along with the

formation of dark mycelia and scattered black microsclerotia that

ultimately result in wilt, leaf drop, and plant death (Fig. 2A) (Pandey

Seedling, Root, and Stem Diseases

et al. 2019).

Nematodes This soil-inhabiting and seedborne fungus resides in all soil types

Plant-parasitic nematodes are microscopic, worm-like animals that use across the world and infects more than 500 plant species including

a needle-like stylet to extract nutrients from plants. Mungbean is host legumes and cereals at almost all growth stages (Martínez-Villarreal

to several plant-parasitic nematodes in south Asia and Africa where et al. 2016, Pandey et al. 2019). M. phaseolina hugely impacted the

warm climate favors the survival of nematodes in soils (Ali 1995). premium mungbean sprout export market from Australia to the

Root-knot nematodes (Meloidogyne spp.) can reduce mungbean U.S. and Europe (Conde and Diatloff 1991, Fuhlbohm et al. 2013).

yield by 13 to 16% (Khan et al. 2002). These parasitic roundworms Yield losses from dry root rot have ranged from 11% in Northern

cause root galls, which impede water uptake and nutrients that lead India (Kaushik et al. 1987) to 44% in Pakistan (Bashir and Malik

to wilting, mineral deficiency, and poor yield (Abad et al. 2003). 1991). Dry root rot of mungbean was reported in Shanxi province

Temperature is a major factor in the nematode replication rate (Joshi of China in 2010 (Zhang et al. 2011).

et al. 2019). The prevalence and virulence of M. phaseolina’s microsclerotia

The pigeon pea cyst nematode (Heterodera cajani) reduced is enhanced by low soil moisture and high temperature (Mbeyagala

mungbean grain yield by 67% when comparing the effect of aldi- et al. 2017). Microsclerotia serve as inoculum when released into

carb nematicide (Saxena and Reddy 1987). A 13% yield loss was at- the soil through decomposition or tillage operations (Pandey et al.

tributed to the reniform nematode (Rotylenchulus reniformis; Dayal 2019). Rainfall during flowering and pod-fill is often associated

and Sharma 2007). with mungbean seed infection; while above ground infections areJournal of Integrated Pest Management, 2022, Vol. 13, No. 1 7

often the result of water splash, systemic infection (Pandey 2019). yield loss to Fusarium wilt (Anderson 1985). Fusarium root rot was

Paraquat herbicide sprays, which can be applied to cause leaf drop observed in mungbean breeding plots in Iowa; breeding efforts are

before harvest, aid in colonization of mungbean seed (Pandey et al. being made to develop resistant cultivars for the U.S. (Sandhu and

2019). Singh 2020).

North American Farmers. Although Macrophomina has not

been reported to infect mungbean in the U.S. or Canada, this im- Collar rot or southern blight, caused by Sclerotium rolfsii Sacc., is

portant soybean pathogen (Allen et al. 2017) has a high likelihood of highly pathogenic on mungbean grown in warm climates with well-

occurring in North American mungbean fields when conditions are drained soils (Yaqub and Shahzad 2005). On mungbean, the first

hot and dry, especially when double cropped. symptoms are yellowing of foliage, then girdling stem lesions near

the soil line, followed by proliferation of white mycelia on plants

Wet root rot and web blight, caused by Rhizoctonia solani Kuhn, (Sun et al. 2020a). During the late disease stage, tan to brown

is found worldwide and is favored by warm, moist soils (Reddy sclerotia form along the stem base and on the soil surface around

et al. 1992). It has a wide host range characterized by multiple anas- declining plants (Sun et al. 2020a). Collar rot impacts production in

tomosis groups that impact the genetic diversity of this pathogen Pakistan (Yaqub and Shahzad 2005) and is an emerging disease in

(Sharon et al. 2008). If infection occurs on the collar region of seed- southern China (Sun et al. 2020a).

Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/jipm/article/13/1/4/6524412 by guest on 20 June 2022

lings, a reddish-brown lesion at or below the soil level girdles the North American Farmers. Farmers, especially in the southern

plant (Basandrai et al. 2016), leading to wet root rot and collar rot states, may encounter collar rot in mungbean although no reports

symptoms (Fig. 2B). High humidity augments rapid spread from have been made. The pathogen is widespread across much of the

irregular water-soaked spots on lower plants parts to the upper U.S. and has a wide host range of over 500 species and produces

canopy leading to web blight (Jhamaria and Sharma 2002). Web abundant overwintering sclerotium survival structures (Punja 1985).

blight is typified by conspicuous spiderweb-like mycelial growth When sclerotia were buried in soils, Sclerotium rolfsii (southern

with white to brown microsclerotia, that rots all above-ground plant blight) survived for one year in Georgia and North Carolina, and

parts (Jhamaria and Sharma 2002). Sclerotium rolfsii var. delphinii (northern blight) survived in the soil

Wet root rot seedling mortality ranges from 20 to 44% across for at least one year in Iowa and North Dakota (Xu et al. 2008).

south Asia (Singh et al. 2013). Web blight causes approximately

30% reduction in grain yield in mungbean in the same region (Singh Several pathogens that are endemic to the U.S. have been reported as

et al. 2013), but is considered a minor disease in Pakistan (Bashir minor diseases on mungbean not listed in Table 1, may also impact

and Malik 1991). North American farmers. Verticillium wilt (Verticillium dahliae) has

North American Farmers. Rhizoctonia root rot and damping-off been reported on mungbean across northern China (Sun et al. 2016).

is commonly found in crops across the U.S. and has been observed in Symptoms include gradual leaf yellowing, wilting, and shortened

Iowa mungbean sentinel plots (Batzer, unpublished). Aboveground internodes resulting in stunting. Basal stems and roots show a ring

web blight is uncommon in the cooler, drier Midwest U.S. (Torres of discoloration within the vascular tissue (Sun et al. 2016). Root

et al. 2016). rot, caused by Pythium myriotylum, is another disease of temperate

climates and was first reported on mungbean in Henan Province in

Vascular wilt and root rot on mungbean are caused by the Fusarium China (Qiang et al. 2020). Sudden death syndrome (SDS), caused by

oxysporum and Fusarium solani complex (Kelly 2018). Affected Fusarium virguliforme, is an important disease of soybean in the U.S.

plants often wilt and die, or they may develop basal rots, leading (Kolander et al. 2012). Although this disease does not impact the

to stunting, leaf yellowing, and defoliation (Fig. 2C)(Pottorff et al. production of mungbean across the globe, it can infect mungbean

2012). When mungbean stems are cut longitudinally, brown vascular in greenhouse conditions (Melgar and Roy 1994). SDS was also ob-

tissues may be visible; white or pink mycelia may also develop at served in mungbean sentinel field plots in Iowa in 2020 and 2021

the plant base (Anderson 1985). The soilborne fungus infects the (Batzer, unpublished). Symptoms of SDS were observed during the

root system through wounds or roots hairs, then invades the vas- early reproductive stage as yellow circular spots, that enlarged be-

cular tissue, and can affect mungbean plants at any stage of growth tween the green leaf veins. (Fig. 2D). Foliage turned brown and was

(de Borba et al. 2017). Fusarium wilt is more prevalent in low-lying accompanied by gray to reddish brown root discoloration, including

areas and heavy clay soils with excess water (Kelly 2018). Urd bean the tap and lateral roots, and crown rot (Fig. 2E). Thus, SDS should

cultivars may have higher levels of resistance to Fusarium pathogens be considered when developing management practices in the

than other mungbean cultivars (Kelly 2017). Midwest U.S. Sclerotinia sclerotiorum causes white mold on more

Fusarium wilt is a minor disease in South Asia (Nair et al. than 40 plant species (Schwartz et al. 2006). White mold was re-

2019), but it may be more important in temperate climates. For ported as a threat to mungbean in Ontario field trials (Tu and Zheng

example, across northern China, F. oxysporum f. sp. mungicola is 1997). The disease is endemic in cool, humid regions of the world

prevalent and increasingly severe on mungbean (Sun et al. 2020b). and is a serious disease on common bean, dry bean (Phaseolus vul-

Severe yield losses in India and Pakistan were associated with garis L.), and soybean; sclerotia survive in the soil and plant debris

F. oxysporum in combination with root knot nematode (Akhtar for years (Steadman et al. 1983).

et al. 2005). Fusarium wilt is considered a minor disease complex

in Australia, with losses of $4.3 million per year (Pandey et al. Management of Root Rot and Soilborne Diseases of Mungbean

2018). In affected paddocks in northern Australia, however, yield Genetic disease resistance or tolerance is the most widely recom-

losses can be 80% (Kelly 2017). mended control strategy against soilborne diseases. Uge et al. (2020)

developed a set of criteria to evaluate mungbean genotype responses

North American Farmers to soilborne pathogens. Mungbean genotypes have been identified

It is likely that Midwest growers will encounter this disease in that could be useful in developing root rot-resistant cultivars (Khan

mungbean. A single report from Ontario, Canada attributed a 20% and Shuaib 2007; Choudhry et al. 2011; Pandey et al. 2019, 2021a).8 Journal of Integrated Pest Management, 2022, Vol. 13, No. 1

Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/jipm/article/13/1/4/6524412 by guest on 20 June 2022

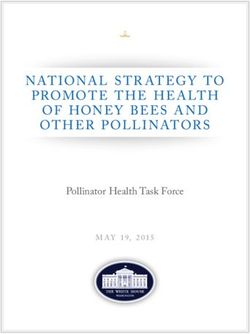

Fig. 2. Mungbean diseases A. Dry root rot lesions on stems caused by Macrophomina phaseolina (provided by Venkata Naresh Boddepalli). B. Wet root

rot pathogen caused by Rhizoctonia solani causing wilt. C. Foliar wilt caused by Fusarium oxysporum. D–E. Sudden death syndrome caused by Fusarium

virguliforme on foliage and reddish-brown root discoloration. F. Yellow mosaic disease (YMD) symptoms (provided by Venkata Naresh Boddepalli). G. Stunting,

stem thickening, leaf enlargement, and crinkling caused by Leaf crinkle virus (LCV) H. Common bacterial blight caused by Xanthomonas axonopodis pv.

vignaeradiatae (Xav) induces irregular necrotic spots with narrow, chlorotic, water-soaked haloes that develop into leaf blight (provided by Dr. Deng-Jin Bing).

I. Water-soaked lesions and leaf scorch symptoms of tan spot caused by Curtobacterium flaccumfaciens pv. flaccumfaciens (Cff) (provided by Venkata Naresh

Boddepalli) J. Powdery mildew covers the upper surface of the leaf with hyphae that develop a white floury appearance (provided by Venkata Naresh Boddepalli)

K. Cercospora leaf spot symptom vary with species, but are often brown, water-soaked, irregularly shaped leaf spots that gradually become dry and gray with

narrow reddish margins (provided by Venkata Naresh Boddepalli). L. Anthracnose, caused by several species of Colletotrichum, show irregularly shaped, dark

brown to black water-soaked spots on undersides of leaves and petioles and later develop “shot holes”, defoliation, and stem cankers (provided by Venkata

Naresh Boddepalli).

A few disease-resistant mungbean lines have been reported (Singh Pathogens with long-surviving sclerotia and oogonia (Macrophomina,

et al. 2013). However, all commercially grown cultivars are currently Rhizoctonia, Sclerotium, Pythium) and are able to grow on organic

susceptible to R. solani (Choudhary et al. 2011). Resistance can by matter (Fusarium) are difficult to manage with rotation alone. The

stymied by pathogen variability and the presence of multiple races addition of organic matter, in combination with controlling weed

(de Borba et al. 2017). hosts during rotation, can further reduce pathogen survival (Mohler

Crop rotation with cereal grains is widely recommended for and Johnson 2009). Solarization for 3 wks using clear polyethylene

legume crops to control disease (Mohler and Johnson 2009). tarps, in combination with organic amendments, and/or the additionJournal of Integrated Pest Management, 2022, Vol. 13, No. 1 9

of fungal biocontrol agents has been shown to reduce viability of with YMD have few flowers, whereas scant pods are yellow-spotted

sclerotia in the soil (Blum and Rodrigues-Kabana 2004, Yaqub and with immature and deformed seeds (Malathi and John 2009). Early

Shahzad 2009, Iqbal et al. 2019). Creating pathogen-suppressive infection results in the highest yield reduction, but losses are low if

soils by deploying organic amendments and Trichoderma virens is infection occurs 8 weeks after planting (Karthikeyan et al. 2014).

recommended for root disease management in India (Dubey and This disease may cause up to 100% yield loss in certain fields across

Singh 2010, Sharma and Gothalwal 2020). Asia (Biswas et al. 2012a).

Using high quality seed will reduce the introduction of pathogens

into the field. Seed vigor testing is a rapid, effective way to select Yellow mosaic diseases are transmitted by whiteflies (Bemisia tabaci

quality seed and ensure proper establishment of the crop. Subjecting Gennadius). A whitefly must feed on the phloem of an infected plant

seed to an accelerated aging test at 42°C for 72 h is recommended for 15 to 60 min to acquire the virus (Ghanim et al. 2001). A single

to assess mungbean seed quality (Silva et al. 2019). Reduction of viruliferous whitefly adult can transmit MYMV to a healthy host

residue, planting times that avoid wet conditions, and avoidance of within 8 hours of acquisition (Czosnek 2008). MYMV circulates

waterlogged fields are recommended for mitigating risk of mungbean within the whitefly, but the virus does not replicate until it is back

root diseases (Kelly et al. 2017). in mungbean (Czosnek et al. 2002). The virus cannot move into

Fungicide seed treatments and side dressing with carbendazim whitefly eggs, but can infect the newly hatched nymphs as they feed

Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/jipm/article/13/1/4/6524412 by guest on 20 June 2022

(FRAC 1) and thiophanate methyl (FRAC 1) reduces Rhizoctonia on mungbean (Czosnek et al. 2002). By itself, the B. tabaci whitefly

seedling rot and dry root rot of mungbean (Reddy et al. 1992, Athira species complex causes 17–71% yield losses in mungbean (Nair et al.

2017). However, a large body of evidence shows that pelleting seed, 2019). The high level of genetic variability of the B. tabaci whitefly

seed dressing, and soil drenching with biocontrol fungal agents species complex drives the virus spread and makes cultivar resistance

Trichoderma harzianum, T. virens, Gliocladium virens or bacterial short-lived (Brown 2007). Genetic resistance of mungbean to YMD

agents such as Rhizobium spp., Bacillus subtilis, Pseudomonas is an ongoing research priority (Mandhare and Suryawanshi 2008,

fluorescens, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and Burkholderia spp. are Akhtar et al. 2009, Sudha et al. 2013, Gupta and Mishra 2014,

more effective than fungicide treatments against a wide range of Akbar et al. 2017, Suman et al. 2018, Nagaraj et al. 2019).

root-infecting fungi and results in increased plant growth (Ebenezar

and Yesuraja 2000; Dubey and Patel 2002; Dubey 2003; Yaqub and Groundnut bud necrosis virus (GBNV) is in the family Bunyaviridea

Shahzad 2008; Dubey et al. 2009, 2011; Deshmukh et al. 2016; that holds the Tospoviruses (Daimei et al. 2017). Necrosis of

Ramzan et al. 2016). Antifungal plant extracts can reduce dry root aboveground plant tissue is caused by GBNV, most seriously the

rot incidence and severity when optimal conditions for their use are growing points, leading to plant death (Biswas et al. 2012b). In

provided (Thilagavath et al. 2007, Murugapriya et al. 2011, Kumari the field, GBNV infects pea (Akram et al. 2010), cowpea, tomato

et al. 2012, Waheed et al. 2016). (Solanum lycopersicum) (Jain et al. 2020), and soybean (Bhat et al.

Two foliar sprays of hexaconazole (FRAC 3), difenconazole 2002). Host range inoculations showed that GBNV can infect spe-

(FRAC 3), propiconazole (FRAC 3), carbendazim (FRAC 1), or cies in the Fabaceae, Cucurbitaceae, Solanaceae, Malvaceae, and

chlorthalonil (FRAC M5), and row spacing of 50 cm or more can Compositaceae families but does not infect Gramineae (Thien et al.

reduce web blight spread across the canopy (Jhamaria and Sharma 2003). Thien (2003) showed that cowpea, chickpea, and mungbean

2002, Dubey 2003, Basandrai et al. 2016). Foliar fungicides con- are the most susceptible, while only local lesions are seen on most

taining carbendazim (FRAC 1), or captan (FRAC M4) have shown other hosts. GBNV is insect-transmitted by Thrips palmi Lindeman

the highest activity in preventing Ma. phaseolina foliar infection (Daimei et al. 2017). Only adult thrips can transmit the virus to new

(Kumari et al. 2012). Economic assessments, disease control, and plants through saliva; however, the virus also colonizes immature

yield outcomes of 16 farms across India in 2016–2019 showed thrips (Moritz et al. 2004).

the most effective disease suppression when fungicides, biocontrol

agents, and phytoextracts were combined in both seed treatments Leaf crinkle disease (LCD) is caused by an RNA virus called

and foliar sprays (Singh et al. 2020a). leaf crinkle virus (LCV). Symptoms of LCD are stunting, stem

thickening, leaf enlargement, and crinkling (Fig. 2G)(Reddy et al.

2005). Early infected plants show more pronounced leaf crinkle;

Foliar Diseases

flowering is delayed and has a bushy appearance, and often fails

Foliar diseases are blamed for the lion’s share of mungbean yield to produce pods (Reddy et al. 2005). Yield losses of urd bean

loss (Pandey et al. 2018). Bacterial pathogens on foliage are widely and mungbean in India, Indonesia, and Pakistan range from 2

reported, and fungal diseases are the most prevalent among foliar to 94%, depending on cultivar, environment, and time of infec-

diseases (Bayu et al. 2021). However, viruses are considered the most tion (Gautam et al. 2016). The disease thrives in high humidity

impactful biotic constraint to mungbean production (Mishra et al. (Ashfaq et al. 2008).

2020). LCV infected seed can serve as a source of primary inoculum,

after which the virus is scattered across the field by feeding insects

Viral Diseases (Ashfaq et al. 2021). Several species of aphids, beetles, and whiteflies

Yellow mosaic diseases (YMD) are caused by the Begoviruses. Several are nonpersistent vectors of the virus (Iftikhar et al. 2020); trans-

Begoviruses cause YMD on mungbean, and include mungbean mission occurs when insects probe plants with their mouthparts

yellow mosaic virus (MYMV), mungbean yellow mosaic India virus (Srivastava and Gupta 2012).

(MYMIV), horsegram yellow mosaic virus (HgYMV), and dolichos

yellow mosaic virus (DoYMV) (Naimuddin et al. 2016, Ramesh et al. Bean common mosaic virus (BCMV) is a positive-stranded RNA

2017). The two-part single-stranded DNA Geminiviruses produce Potyvirus that causes Bean common mosaic disease (BCMD)

bright yellow mosaic symptoms on infected leaves that slowly wilt symptoms: dwarfing, chlorosis, deformation, leaf curling, and mo-

(Fig. 2F) (Hussain et al. 2004, Akbar et al. 2019). Mungbean plants saic (Flores-Estévez et al. 2003). BCMV is one of the most widely10 Journal of Integrated Pest Management, 2022, Vol. 13, No. 1

found and damaging viruses of bean (Yadav et al 2021). Kaiser and BCMNV (Lee et al. 2017). Molecular diagnosis is essential to detect

Mossahebi (1974) first reported BCMD on mungbean from Iran, GNV virus, since thrips damage alone may cause similar necrosis

where it was the most important disease affecting the crop. The symptoms (Raja and Jain 2006).

virus has since been found on mungbean in Sri Lanka, Thailand,

Korea, China, India, and Kenya (Jeyanandarajah and Brunt 1993, Genetics

Choi et al. 2006, Cui et al. 2014, Mangen 2014, Tsuchaizaki et al. Disease resistance is the best control strategy against viral diseases,

1996, Yadav et al. 2021). In 1992, the BCMD causal pathogen was if available. Several high-yielding urd bean cultivars with YMD re-

divided into two species, BCMV and bean common mosaic necrosis sistance have been released in India from 2008 to 2019 (Pratap et al.

virus (BCMNV) (Worrall et al. 2015). Naturally occurring BCMNV 2021). A number of sources for YMD resistance have been identified

on mungbean has not been reported to date, although artificial in- for urd bean (Naimuddin et al. 2016). Since several Vigna species are

fections on mungbean have been demonstrated in controlled trials cross-fertile, efforts are being made to introduce MYMD immunity

(Worrall et al. 2015). Both BCMV and BCMNV are transmitted by from urd bean to mungbean (Lekha et al. 2018). Several MYMD

aphids in a nonpersistent manner, by mechanical means, and through resistant and moderately tolerant mungbean varieties are available

seed. There are six plant families susceptible to BCMV and BCMNV in India that were developed using mutation in India (Pratap et al.

(Worrall et al. 2015). Thus, crops may be vulnerable to attack from 2021). BCMV resistant common bean cultivars have been developed

Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/jipm/article/13/1/4/6524412 by guest on 20 June 2022

mungbean seedlings or nearby weeds and transmitted across the field (Singh and Schwartz 2010), but there is no information on BCMV

by aphids. are the major constraints in cultivation and production resistant mungbean. Transgenic GBNV-resistant plants are being

of green gram. studied for environmentally safe management of the disease (Varma

et al. 2002). Several disease-resistant mungbean cultivars have been

North American Farmers developed for LCV (Kaur 2007, 2011).

BCMV is one of the most serious and widespread viruses in beans

(Yadav et al. 2021). GBNV is closely related to soybean vein necrosis Exclusion

virus (SVNV). In the U.S., SVNV is a widespread virus that causes Using virus-free certified seed is a highly effective way to avoid

disease, reducing both yield and oil content of seed (Keough et al. losses from viral diseases. Among the seedborne viruses, BCMV

2016, Anderson et al. 2017). Thus, it is likely that mungbean farmers and MYMV are the most damaging to mungbean (Yadav 2021).

may encounter a similar virus. Research is needed to screen SVNV Almost 50% of viruses affecting leguminous crops are seed-

against U.S. mungbean and urd bean cultivars. Besides the afore- borne (Bos et al. 1988). Roguing virus-affected plants early in

mentioned viral diseases, mungbean is host to several commonly the growing season can control MYMV and LCV (Sastry 2013,

found viruses in the U.S., such as Cucumber mosaic virus (CMV) Akbar et al. 2019).

and Alfalfa mosaic virus (AMV) (Sastry 2013). Insect vectors can be excluded from mungbean fields by removal

The YMV white fly vector is prevalent on cotton and soybean of surrounding weeds that act as reservoir hosts (Biswas et al. 2012a,

in Australia, Brazil, and Mexico (Oliveira et al. 2001). In the U.S., Sastry 2013). Yellow sticky traps at a rate of 10 to 12 traps per

B. tabaci is difficult to control in U.S. greenhouses and field crops hectare are recommended to reduce whiteflies for the prevention of

in the southwest, along with geminiviruses impacting beans, to- MYMV (Mbeyagala et al. 2017). Barrier cropping and intercropping

matoes, lettuce, sugarbeets, and melons (Oliveira et al. 2001). with cereal crops protects mungbean from aphid- and whitefly-

Although MYMD is not reported in the Americas or Australia transmitted viruses (Biswas et al. 2012a). In South Asia, infection

(Mishra et al. 2020), the presence of its vector may leave southern can also be avoided by planting in the spring when whitefly popula-

grown mungbean vulnerable to YMD viruses, if introduced on tions are little to none (Akbar et al. 2017).

plants.

Synthetic and Natural Insecticides

Management of Viral Diseases Imidacloprid seed treatments are a prime method to reduce white-

Detection is key for virus disease management. Rapid results from flies because the insecticide is translocated through the plant and

molecular and antibody tests are available from plant diagnostic la- persists within plant tissues (Ghosh et al. 2009, Dubey and Singh

boratories that enable farmers to select appropriate tactics to head 2010). Foliar insecticide sprays of imidacloprid or triazophos + di-

off imminent crop damage. The protein that covers a virus is used methoate are recommended to control whiteflies, thrips, and aphids

to detect its presence in plants. Enzyme-linked immunosorbent on mungbean (Ganapathy and Karuppiah 2004, Sreekanth et al.

assay (ELISA) uses antibodies that attach to the virus protein coat. 2004, Khaliq et al. 2017). Neem and eucalyptus plant extracts

Monoclonal antibodies and polyclonal antisera are widely used also suppress whitefly and subsequently reduce MYMV incidence

to reliably and inexpensively detect the presence of a virus; this (Younas et al. 2021).

decades-old-method can be very specific (Yadav et al. 2021). Systemic acquired resistance has been pursued by several re-

Molecular methods are becoming more widely used. Specific searchers in order to help mungbean hosts tolerate the damaging ef-

primers designed to join with the viral nucleotide sequences of fects of viruses. Certain compounds are produced naturally in plants

the coat proteins are needed to amplify the RNA or DNA of cer- in response to pathogen attack; these further stimulate the plant

tain viruses using polymerase chain reaction (PCR) (Mullis et al. to produce compounds that activate plant defenses (Biswas et al.

1986) or reverse-transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) 2012b). Such compounds can be applied to the foliage to stimulate

(Thompson and Dietzgen 1995). Multiple primers have been de- the plants own defenses. For example, methyl jasmonate applica-

veloped for mungbean (Baranwal et al. 2015, Naimuddin et al. tions were shown to give YMV tolerance to urd bean (Chakraborty

2016, Arous et al. 2018, Sandra et al. 2021). Although PCR has and Basak 2018). Applications of salicylic acid (aspirin) and

been expensive and can take several days, more affordable, con- benzothiadiazole at 5 mN and 150 mg/L, respectively, reduced

venient, and rapid methods are becoming available. For example, disease severity of MYMV, compared to nontreated mungbean con-

a loop-mediated isothermal amplification assay (LAMP) can detect trol plants (Burhan-ud-Din et al. 2019).Journal of Integrated Pest Management, 2022, Vol. 13, No. 1 11

Bacterial Diseases Tan spot/bacterial wilt caused by Curtobacterium flaccumfaciens

Halo blight is caused by Pseudomonas savastanoi pv. phaseolicola pv. flaccumfaciens (Cff) is a leaf and vascular disease that affects

Janse (Psp). Foliar symptoms are round, dark-brown, water-soaked mungbean, common bean, cowpea, and soybean (Diatloff et al.

lesions; chlorotic halos form as the bacteria secrete a toxin (González 1993). Diseased plants display water-soaked lesions and leaf scorch

et al. 2003). Halo blight poses a threat to the mungbean industry typified by marginal and interveinal necrosis (Fig. 2I) (Wood and

and has received extensive study (Sun et al. 2017, AMA 2020). The Easdown 1990). No wilting occurs on mungbean; however, plants

pathogen can inflict up to 75% yield loss in inoculated fields (Ryley may lose turgor and become “flabby or flaccid,” leading to the

and Tantell 2011). Mungbean yield in China during 2009–2014 pathogen species name “flaccumfaciens.” Early symptoms are easily

was reduced 30 to 50% due to halo blight, and total crop failure mistaken for moisture stress or zinc deficiency (Wood and Easdown

occurred in severely infected fields (Sun et al. 2017). Halo blight 1990). Diagnosis is confirmed by microscopic viewing of bacterial

was also reported on mungbean in Pakistan, India, and Africa (its ooze from cut surfaces of petioles (Huang et al. 2009). A toxin is

likely place of origin) (Taylor et al. 1996, Akhtar et al 2016). The involved in pathogenesis (Wood and Easdown 1990). Seedlings and

Psp pathogen is highly diverse, and multiple races occur in legumes young plants are more severely affected, particularly if the disease

across the globe (Lamichhane et al. 2015). originates from infected seed. Infected seedlings die when temperat-

Halo blight is favored by wet, cool temperatures (Noble et al ures exceed 30°C (Huang et al. 2009). Although the pathogen res-

Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/jipm/article/13/1/4/6524412 by guest on 20 June 2022

2019). The Psp pathogen is seedborne, and infection incidence as ides in the vascular system, the seed coat can be discolored with Cff

low as 0.01% can lead to outbreaks of halo blight (Abdullah and variants that may be orange, yellow, red, pink, or purple while pods

Douglas 2021). The Psp bacterium can spread from seed to seed appear healthy (Harveson 2013). In severe infections, mungbean

while in storage (Abdullah and Douglas 2021). Asymptomatic flowers are also blighted and seed-set will be severely reduced (Wood

spread in the field precedes symptoms. The pathogen enters plants and Easdown 1990).

through natural openings such as stomata and wounds, but in- Infested seed is the primary means of disease spread. The Cff

fection and disease development are dependent on weather con- bacterium can survive on the seed surface for more than 20 yrs

ditions (Marques and Samson 2016). Rainfall favors infection by (Burkholder 1945). Seed-transmitted bacteria occur in very low num-

driving the bacterium into the apoplasts of the leaves (Marques bers, making them difficult to detect (Diatloff et al. 1993). However,

and Samson 2016). Most strains of the bacterium produce a toxin a monoclonal antibody assay or a polymerase chain reaction (PCR)

(phaseolotoxin) that is temperature-dependent; the highest toxin test can detect the bacterium at a very low incidence (Diatloff et al.

levels are released at 18 to 20°C, but toxin production ceases above 1993, Guimaraes et al. 2001). On the other hand, a 3-yr Nebraska

28°C (González et al. 2003). survey found that Cff survived on wheat, corn, sunflower, soybean,

North American Farmers. Halo blight is found on common bean and alfalfa (Harveson et al. 2015). Storms, hail events, or any other

in the U.S. and will be a factor in mungbean disease management physical damage from humans, animals, or farm equipment allowed

in the U.S. Although halo blight is not documented as a mungbean Cff to enter and infect the host plant (Harveson et al. 2006).

pathogen in the U.S., isolates from U.S. mungbean were used in gen- Tan spot was first studied nearly 100 years ago in South Dakota

etic studies (Taylor et al. 1996) and Canada isolates were used in (Hedges 1926). Africa and Europe have limited occurrence of Cff,

mungbean cultivar evaluation (Olson et al. 2010). On common bean and to date the pathogen has not been reported in Asia (Osdaghi

in Idaho, Psp is considered to be so great a threat that any seed testing et al. 2020). Tan spot has become a concern in Australia (Vaghefi

positive for this pathogen must be destroyed (Arnold et al. 2011). et al. 2019b), where the pathogen was first reported on mungbean

in 1984 (Wood and Easdown 1990). Australian strains were closely

related to a pathogen that caused widespread tan spot on soybean in

Bacterial leaf spot (common bacterial blight) caused by Xanthomonas

Iowa during 1981 (Dunleavy 1983, Harveson et al. 2015). Whole-

axonopodis pv. vignaeradiatae (Xav) induces irregular necrotic spots

genome sequencing has provided a set of Cff isolates representing

with narrow, chlorotic, water-soaked haloes that develop into leaf

the genetic diversity of the pathogen population(s) across the globe,

blight (Fig. 2H)(Osdaghi 2014). Even asymptomatically-infected

which can be used to develop resistant mungbean cultivars (Vaghefi

seeds can reduce yield up to 40% (Chaturvedi et al. 2018). Symptoms

et al. 2019a, Chen et al. 2021). The Australian breeding team is

on seed include yellow to brown spots as well as bacterial ooze near

working on increasing its tan spot and halo blight resistance ratings

the hilum (Chaturvedi et al. 2018). The disease causes 5 to 15%

to be equivalent to or higher than that of other cultivars (Ryley and

losses to mungbean in semi-arid regions of Iran, Kenya, and India

Tantell 2011).

(Sabet et al. 1969, Tollo et al. 2020) and is an important disease

North American Farmers. Tan spot is endemic on edible dry

of mungbean in India (Kumar et al. 2018). The Xav bacterium is

beans in the U.S. (Harveson et al. 2015), where new outbreaks

transmitted through infected seed (He and Munkvold 2013) and can

have occurred in recent decades (Harveson et al. 2006, Huang et al.

survive on mungbean seed for nearly 2 yrs (Kumar 2016).

2009). Thus, North American mungbean farmers, breeders, and

North American Farmers. Midwest farmers should be on the

plant pathologists should expect to confront this disease.

look-out for Xanthomonas axonopodis pathovars causing bacterial

leafspot in mungbean. Although the pathogen was not reported to

be isolated and identified, common bacterial blight symptoms were Management of Bacterial Diseases

noted in a mungbean evaluation in western Canada (Olson et al. Successful mungbean production in the U.S. will require a systematic

2011). scheme to minimize bacterial disease introduction into the grower’s

Common bacterial blight (Xanthomonas axonopodis pv. fields. Programs to verify seed quality will be essential to detect spe-

phaseoli) is the most common bacterial disease in dry beans in the cific bacterial pathogens.

Central High Plains (Harveson et al. 2015). Bacterial pustule of soy- Detection and exclusion are foremost in managing bacterial

bean (Xanthomonas axonopodis pv. glycines) is present across the diseases. The most effective defense against bacterial diseases is to

U.S., although it is largely controlled with resistance in the Midwest grow seed in locations that are inhospitable to pathogens (Gitaitis

(Groth and Braun 1989). and Walcott 2007). Although traditional diagnostic assays such asYou can also read