Men Finally Got It! Rhotic Assibilation in Mexican Spanish in Chihuahua - MDPI

←

→

Page content transcription

If your browser does not render page correctly, please read the page content below

languages

Article

Men Finally Got It! Rhotic Assibilation in Mexican

Spanish in Chihuahua

Natalia Mazzaro * and Raquel González de Anda

Department of Languages and Linguistics, University of Texas at El Paso, El Paso, TX 79968, USA;

raquelg@utep.edu

* Correspondence: nmazzaro@utep.edu

Received: 17 August 2020; Accepted: 3 October 2020; Published: 14 October 2020

Abstract: Rhotic assibilation is a common sociolinguistic variable observed in different Spanish speaking

countries such as Argentina, Ecuador, and México. Previous studies reported that rhotic assibilation

alternates with the flap and/or with the trill. In this study, we explore three aspects of rhotic assibilation in

the Spanish of the state of Chihuahua, Mexico/El Paso, TX, United States: (1) Its diachronic development;

(2) the linguistic and social factors that affect this variation and; (3) the possible effect of contact with

English in this variable. Fifty-eight participants, including Spanish monolingual and Spanish-English

bilingual subjects, performed one formal and two semi-informal speech production tasks. Acoustic and

perceptual analysis of the tokens showed that the variation is not binary (standard vs. non-standard

variant), but that it includes other rhotic variants with varying degrees of frication. Variation is restricted

to phrase-final position and heavily favored by preceding front vowels (/e/ and /i/). These effects have

a clear aerodynamic and articulatory motivation. Rhotic assibilation is not receding, as previously

reported. It continues to be a prestigious variable prevalent amongst females, but also present in male

speakers. The comparison between bilingual and monolingual speakers shows that contact with English

does not significantly affect the occurrence of assibilation.

Keywords: rhotic assibilation; sociolinguistics; sociophonetics; Mexican Spanish; variation

1. Introduction

Rhotic assibilation is a pervasive feature of most varieties of Spanish. It has been reported in

Argentina (Colantoni 2006); Bolivia (Morgan and Sessarego 2016); Costa Rica (Vásquez Carranza 2006);

Ecuador (Bradley 2004); Spain (Henriksen and Willis 2010); Dominican Republic (Willis 2007); and

Mexico (Amastae et al. 1998; Bradley and Willis 2012; Eller 2013; Lope Blanch 1967; Perissinotto 1972;

Rissel 1989). Although assibilation is a common feature in all these dialects, social and linguistic factors

seem to influence the phonological feature in unique ways. In this study, we focus on rhotic assibilation

in the Spanish of the state of Chihuahua, Mexico/El Paso, TX, United States. We explore three aspects of

rhotic assibilation: (i) The development of this feature more than two decades after the first (and only)

study was conducted in this same dialect (Amastae et al. 1998); (ii) the linguistic and social factors that

affect this variation; and (iii) whether contact with English affects the variable in bilinguals.

The rest of the paper is organized as follows: Section 1 reviews the phonetic and phonological

characteristics of rhotics, the sociolinguistic literature on rhotic assibilation in Mexico City and Ciudad

Juárez, Chihuahua. Section 2 details the methodology for the study. Section 3 introduces the results,

and Section 4 answers the research questions and relates the findings of the present study with the

literature reviewed. Finally, we conclude and discuss the future directions of this research.

Languages 2020, 5, 38; doi:10.3390/languages5040038 www.mdpi.com/journal/languagesLanguages 2020, 5,

Languages

x FOR

Languages PEER

2020, 5, 2020,REVIEW

38 5, x FOR PEER REVIEW 2 of 21 2 of 21

1.1. Phonological,

1.1. Articulatory,

Phonological, and

Articulatory,

Acoustic Characteristics

and Acoustic Characteristics

of Spanish Rhotics

of Spanish Rhotics

Languages 2020, 5, x1.1.

FOR Phonological,

PEER REVIEW Articulatory, and Acoustic Characteristics of Spanish Rhotics 2 of 21

REVIEW With regard to

With

rhotic

regard

distribution,

to rhotic there

distribution,

is a clear

there

distinction

is a clear

2 between

of distinction

21 the syllabic

between positions

the syllabic

With regard to rhotic distribution, there is a clear distinction between the syllabic positions that thatposition

can be occupied

1.1. Phonological, can can

Articulatory,

be by

occupiedbe tapsoccupied

and

by and

taps trills.

Acousticby trills.

and taps Taps and/ /ɾtrills.

Characteristics

Taps /,/,asas inTaps

in ofcaro

caro /ká/ ɾo/

Spanish /káɾo/

/,‘expensive’,

asRhotics

in‘expensive’,

caroand /káɾo/trillsand /r̄/, astrills

‘expensive’, in carro /r̄/,/kár̄o/

and

as intrills carro /r̄/, as in

ory, and /kár̄Acoustic

o/ ‘car’, Characteristics

‘car’, contrast

contrast

/kár̄ o/ ‘car’,

in of SpanishinRhotics

in word-internal

word-internal

contrast intervocalic

word-internal

intervocalic Languages

position position (Hualde

intervocalic 2020, 5,

2005).

(Hualde x FOR

position In PEER

word-initial

2005). REVIEW

(Hualde position

In word-initial 2005). and after

Inposition

word-initial and position

x FORWith PEER REVIEW regard a to rhoticindistribution,

consonant a different thereonly

syllable, is a the clear trill distinction

occurs: Rosa between

/r̄ósa/ ‘rose’theand syllabic positions

of 21 /isr̄aél/.

2Israel The that

tap

after a consonant

distribution, there after ina consonant

a different in

syllable,

a different only syllable,

the trill occurs:

only theRosa trillthat /r̄

occurs:

ósa/ ‘rose’ Rosaand /r̄ósa/ Israel‘rose’ /isr̄andaél/.Israel

The /isr̄aél/

can be occupied by istaps

occurs ina onset

clear distinction

andclusters:

trills. Taps Prosabetween / ɾósa/

/p /, as‘prose’the

in syllabic

caro and/káɾo/

1.1. positions

Phonological,

in ‘expensive’,

word-final Articulatory,

position and

before trills

aand /r̄Acoustic

vowel: /, asSerin carro

amigosCharacteristics of Sp

tap occurs/ ɾin/,tap onset occurs clusters:in onset Prosa clusters:

/pɾósa/Prosa ‘prose’ /pɾósa/

and in

,‘prose’

asword-final and inposition word-final before positiona vowel: before Ser a vowe

and

/kár̄ otrills.

/ ‘car’,Taps

l, Articulatory, /sé amígos/

and

contrast asword-internal

Acoustic

in in‘to caro /káɾo/

Characteristics

be friends’. ‘expensive’,

of Spanish

A variable

intervocalic rhotic andRhotics

position trills

appears /r̄/coda

in

(Hualde in carro

position

2005). In(within

word-initial a word orposition across word and

rd-internal amigos /séɾ amíɡos/

amigos

boundaries)

intervocalic ‘to

/séɾ

followed

position beamíɡos/

friends’.

by a consonant

(Hualde ‘to A bevariable

2005). friends’.

orIn atrill rhotic

pause, Ai.e.,

word-initial variable

appears

With

when rhotic

in coda

regard

resyllabification

position appears

to position

and rhotic isandindistribution,

not coda

(within

possible. positiona word

While therea(within

orisacross

tap a word

a clear or a

distinc

after a

rd to rhotic consonant in a different syllable, only the occurs: Rosa /r̄ ó sa/ ‘rose’ Israel /isr̄ a él/. The

erent word distribution,

syllable, boundaries)

is more

only word

the

there

followed

frequently

trill boundaries)

occurs:

isfound

a clear

by

Rosaina distinction

followed

consonant

these

/r̄ósa/ contexts,by between

‘rose’ or

aan consonant

and aemphatic

can bethe

pause,

Israel

syllabic

i.e.,

occupiedoracan

trill

/isr̄ aél/.

whenpause,

by

also positions

The resyllabification

taps

occur i.e.,1and

e.g.,that

when arte resyllabification

trills. Taps

a[r̄]te isornot / ɾ]te

á[ possible.

/, as iniscaro not /káɾ

pos

tap occurs in onset clusters: Prosa

ɾ] /,oras /pɾósa/ ‘prose’ and in word-final position before a vowel: Ser

d by taps

ers: While

Prosa

and a tap

/pɾósa/

trills.

‘art’, amor

is

WhileTaps

more

‘prose’

amo[ /frequently

aandtap in

amo[r̄]

is in caro

more

word-final

‘love’.

found /káɾo/

frequentlyFollowing

in ‘expensive’,

these

position

Hualde

found contexts,

/kár̄

before oin and

/(2005),

these

‘car’, an

acoda

wetrillswill/r̄

emphatic

contexts,

contrast

vowel:

use/, the

asan in

symbol

trill

Serin word-internal can/r/also

carro

emphatic to represent

trill

occur can

intervocalic 1 the alsoarte

e.g., occur1 e.g.

position (H

amigos

ntrast in /séɾ amíɡos/ ‘to

non-distinct be friends’.

rhotic found A variable

in final rhotic

position appears

where there in

is no possible position (within

resyllabification. a word

We will or across

also use

friends’. a[r̄word-internal

]Atevariable

or á[ɾ]tea[r̄ ]intervocalic

‘art’,

rhotic te or amor á[ɾ]te

appears amo[ɾ] position

‘art’,

inrather

codaamor (Hualde

or position

amo[r̄ amo[ɾ] ] ‘love’. 2005).

orafter

(within amo[r̄ In

Following word-initial

] ‘love’.

aa refer

consonant

word or Hualde inposition

Following

across (2005),

a different and

Hualdewesyllable,

will (2005),

useonly thewethe symbol

will useoccurs:

trill the sy

word boundaries)

nt in a different the followed

neutral

syllable, term

only by

‘rhotic’a consonant

the trillthe occurs: than or

‘tap’ a

Rosafound pause,

and ‘trill’

/r̄ótap sa/ i.e.,

to

‘rose’ when

andto it. resyllabification

Israel is not possible.

ed by /r/ to represent

aa consonant /r/ atothe

orfrequently represent

pause, non-distinct

i.e., when non-distinct

rhotic

resyllabification 2 share rhotic

in

occurs

is final

found

not position

inpossible.

onset in /isr̄ final aél/.

where

clusters: The

position there where

Prosa is no there

/pɾósa/ possible

‘prose’ isand no inpos w

While tap is more Articulatorily, standard

found taps

in and trills

these contexts, the

an same

emphatic place and trillmannercan of articulation;

also occur 1 e.g.,they arte are

onset clusters:resyllabification. Prosa /pɾósa/

resyllabification.

Werealizedwill ‘prose’

also andthe

use

We will inneutral

word-final

also position before a‘to vowel: Ser

uently

a[r̄ ] te or found

á[ɾ]te both

in‘art’,

these usually

amor contexts, amo[ɾ] anas

or voiced

emphatic

amo[r̄ and

] trill use

alveolar

‘love’. can term

3 . the

Following

amigos

The

also ‘rhotic’

neutral

mainoccur /séɾ 1rather

term

amíɡos/

difference

Hualde

‘rhotic’

e.g.,(2005), than

between

arte ‘tap’

be

we

rather

taps and

friends’.

will and than

‘trill’

use

A‘tap’

trills theistothat

variablerefer

and

symbol

‘trill’

to it. to

tapsrhotic refer toi

appears

íɡos/ ‘to be Articulatorily,

friends’. A variable with rhotic

Articulatorily,

standard tapsappears

standard

andbetween in coda

trills taps

2 share position

and trills

the (within

same

2 share athe word or across

amo[ɾ]

/r/ to or amo[r̄

represent

are] produced

‘love’.

the Following

non-distinct

a single contact

Hualde

rhotic (2005),

found

the

we

in

word

tip

will

final

of the

use the place

boundaries)

tongue

position

towards

symbol where

andsame

followed

the manner place

alveolar

there is

aof

by ridge,and

no

articulation;

manner

consonant

while

possible

trillsor of athey

articulation;

pause, i.e.,

ies) followed

are both byareaproduced

usually consonant

are both

realized with or

usually as avoiced

several pause,

realized

(usually andi.e.,

as

two when

alveolar

voiced

or three) resyllabification

3and

. The

such

Whileisa tap alveolar

main

rapid difference

3. The

contacts

is is not

main

(Hualde possible.

betweendifference

2005).

more frequently found in these contexts, taps

Navarro between

and trills

Tomás taps

is that

and trills

anis

n-distinct

resyllabification. rhotic We found will in final

also use theposition

neutral where

term there

‘rhotic’ rather no than possible ‘tap’ and ‘trill’ to refer to it.

more taps frequently (Tomásfound 1970, pp.

inwith these 1, 116) gave

contexts, a more an detailed

emphatic description

trill can of the

also Spanish

occur trill

tip e.g.,

1 that specifies

arte the position

also use theare

Articulatorily,

produced

neutral

of the

taps

term

standard

tongue

are produced

‘rhotic’

tip, taps

a single

dorsum,rather

and

with

and

contact

than

trillsroot.

a single

2 ‘tap’

share

He

betweenand

stated

contact

the

a[r̄ ]the

‘trill’

same

that

te or

the tobetween

tip of

á[ɾ]te

refer

place

tip of

the

the to

and

the

‘art’,tongue

it.

tongue

amor

manner

oftowards

bends

the

amo[ɾ]

of

tongue ortheamo[r̄

articulation;

upwards to

alveolar

towards

touch

] ‘love’.

they

the

ridge,

the Following

alveolar r

‘art’, amor while amo[ɾ] are or amo[r̄ ] ‘love’. Following Hualde (2005), we willtwo use orthe symbol

ard

are taps

both andtrills

usually trills 2 while

share

realized

upper-most

produced trills

thevoiced

as

part

are

same

of

with produced

the alveolarplace

and

several and with

alveolar

ridge,

(usually

manner

the3. The

several

tongue

/r/oftwo

main

to (usually

or

articulation;

root

three)

represent

difference

retracts towards

such

theythe

between

rapid

three)

non-distinct

the back taps

contacts

such rapid

of the and oraltrills

(Hualde

rhotic

cavity, is

contacts

found

that

and

2005). (Hualde

in final 2

nt theNavarro non-distinct Tomás rhotic

Navarro 3([1918]

found

Tomás 1970,difference in final position where there isWeno possible

as voiced

taps are and alveolar

produced the tongue

with . The

body

a main

singleadopts a([1918]

contact

pp.

hollow 1, 116) 1970,

or

between betweengave

concave pp.shape.

the

a1,

taps

tip

more

116)

resyllabification.

of and gave

detailed

the trills a more

tongue isdescription

that detailed

will

towards

alsoofdescription

the

use thethe

alveolar

Spanish

neutral of trill

ridge,

the

term Spanish

that

‘rhotic’tril ra

n. We specifies

will also the useposition

the

specifies neutral

The realization of

the term

the position ‘rhotic’

tongue of tip, rather

the dorsum,

tongue than and‘tap’

tip, and

dorsum,

root.

Articulatorily,He‘trill’and

stated to refer

root. that

standard He tothe it.

stated

tip

taps of that

the the

trills share the sameb

tongue

andtongue-tip tip2 of

bends

the tongue

singletrills

while contact are between

produced the with tipofseveral

oftrillstherequires

tongue

(usually

a complex

towardstwo

combination

or the three) alveolar of articulatory

such ridge,

rapid

movements

contacts

of the

(Hualde 2005). 3

rily, standard

upwards taps

to touch

and and the

upwards

aerodynamic trills 2 share

upper-most

to touch

forces the

(Soléthe same

part

upper-most

2002). of

Due place

the to their and

alveolar

part

are manner

ofridge,

both

articulatory theusually of

thearticulation;

alveolar

complexity, tongue ridge,

realized trills root asthey

the

are retracts

tongueand

voiced

mastered towards

root

late retracts

inalveolar

the L1 the back.towards

The main thed

with

Navarro several

Tomás (usually

([1918] two

1970, or pp.three) 1, such

116) gave rapid a morecontacts detailed (Hualde description 2005). of the Spanish trill that

y realized of the asoralvoiced ofand

acquisition

cavity, the andalveolar

andoral are

the not

cavity, 3 .present

tongue The and main

inthe

body difference

thetongue

babblinga

adopts stage.

body between

hollow

taps Not

are only

adopts or taps

ado

concave

produced andwith

native

hollow trills

speakers

shape. aissingle

or concave that

find trills shape.

contactchallenging,between the tip of

970,

specifies pp. 1,

the 116) butgave

position L2 a more

of

learners the maydetailed

tongue also tip,

find description

dorsum,

them and

difficult ofto the

root.acquire Spanish

He stated

and trill

some that that

may thenever tip of

succeedthe tongue

in rolling bends

their

ced with aThe single contact

realization The ofbetween

realization

trills the of

requires tiptrills

a of the

complex

requires tongue combination

whilea towards

complex trills of the

combination

arebends alveolar

articulatory ofridge,

movements

produced with several (usuallyarticulatory of movements

the tongue- two of orthethre

ton

he tongue

upwards tip,

to dorsum,

touch [r]s the(Solé and

upper-most root.

2002). Because He part stated

theofproduction

the that the

alveolar tip

mechanism of

ridge, the thetongue

tongue

of trills is quite root retracts

complex andtowards

requiresthe back

precise

produced tippart and with several

aerodynamic tip andand (usually

aerodynamic

forces two or

(Solé 2002).

forcesthree) Due(Solésuch to2002). rapid

their

Navarro contacts

articulatory

Due to the

Tomás their (Hualde

complexity,

articulatory

([1918] 1970,2005). trills

complexity,

pp. 1,are 116) mastered trillsaare

gave late

more mastered

detai

er-most

of the oral of

cavity, theand alveolar

articulatory the ridge,

tongue aerodynamic the

body tongue conditions,

adopts root

a retracts

hollowsmall or towards

changes concave in their shape. back

production can lead to perceptible

s ([1918] in body 1970,

the L1adopts pp.

acoustic 1,

acquisition

in athe 116)

differences. gave

L1and acquisition

are a

These more

notsmall detailed

present

and areinnot

changes description

the

in present

thebabbling

specifies

production of

in stage.

the the

theofbabbling Spanish

Notwhich

position

trills, only trill

stage.

of do native

the

could that

Not

tongue

be due only speakers

tip, dodorsum,

native findspeakers

trills

and root. find

He

tongue

osition The of realization

the tongue oftip,

hollow

trills dorsum,

or

requires concave

and a complex

root.

shape.

He combination

stated that the of tiparticulatory

of the tongue movements bends ofto the contextual

tongue-

ls requires challenging,

a complex but

challenging,

or prosodic L2features,

combination learners but

createmay

of L2 learners

also find

a favorable

articulatory maythem

environment

movements also difficult

upwards find

for the

ofthemto

to acquire

touch

instability

the difficult

tongue- theofand tosound

some

upper-most

this acquire may

and and

thenever

part some

of the

creation succeed

may

ofalveolarnever

in ridge,succe th

uchtip andupper-most

the aerodynamic new part forces

variants. of the

In

(Soléalveolar

fact,

2002).

the rich

Due

ridge,literature

to their

the tongue

on

articulatory

rhotic root

variationretracts complexity,

in towards

different

trills

the

dialects back are

of

mastered

Spanish provides

late

es the

(Solé rolling

2002). their

Due [r]s

rolling

toand (Solé

their their

2002). [r]sBecause

articulatory (Solécomplexity,

2002).

the production

Because ofthe

trills the mechanism

are production

oral cavity,

mastered ofmechanism

trillsthe

and is quite

tongue ofcomplex

trills

body is quiteand complex

adopts requires

a hollow andorreq co

in L1the

ty, andprecise acquisition

tongue evidence body for are

the

adopts not present

instability

a hollow of in

trills

or the

and, babbling

concave most stage.

importantly,

shape. Notthe onlylate

methodologicaldo native speakers

challenges they find presenttrills

are not present articulatory

inL2 the precise

babbling and

articulatory

aerodynamic

stage. and aerodynamic

conditions, small

conditions,

The changes

realization small in their

of trills changes production

requires in their

a complex canproduction

lead to can lea

combination o

challenging,

ation of trills but in

requires their learners

analysis may

a complex (see alsoNot

Method

combination find only

section). themof

dodifficult

native speakers

articulatory to movements

acquire find and trills

ofsomethe may never succeed in

tongue-

ers may perceptible

also [r]s find(Solé acoustic

themperceptible differences.

difficult acoustic These

differences. small changes

Thesetip and smallinaerodynamic

the changes

production in forces

theofproduction

trills,

(Soléwhich 2002). ofcould

trills,

Due tobe which duecould

their articula be

rolling their Acoustically,

2002). theto

Because tap acquire

and

the the and

trill

production some

share the may never

same characteristics:

mechanism ofsucceed

trills in

Aislowered

quite complex third formant and(Colantoni

requires

namictoforces contextual (Solé

2001)to

2002).

or contextual

prosodic Due to their

features,

orofprosodic articulatory

create complexity, trills are mastered late

2). Because

precise the production

articulatory and

and brief periods

mechanism

aerodynamic trillsfeatures,

occlusion,

ofconditions, isaquite

one favorable

occlusion create

in the

complex

small for environment

a favorable

L1

the

changes

acquisition

tap

and and inmore

requires environment

forthan

their

the one

and instability

arefor

production

not for

the the

presentof this

trill. instability

canHowever,

insound

lead to

of

the babblingand this soundstage

sition and are

the creation not present

taps of the

andnew in

creation the

variants.

differ of babblingnew Induration

fact, stage.

variants. Not only do native speakers find trills

aerodynamic

perceptible conditions,

acoustic

trills

differences. small in

These

the

changes small in the of the

their

changes

rich

Inproduction

fact,

literature

segment,

in the

the

challenging, with richon

tapsliterature

can

production

rhotic

but being

lead L2shorter

oftovariation

on than

learners

trills,

rhotic

may

which

in different

trills.variation

also

Quilis find

could be due

dialects

(1993)in

them differentof dialec

difficult to a

ut L2 learners

Spanish may

provides also

Spanish find

evidencethem

provides difficult

for evidence to

the instability acquire and some may never succeed in

offor the of instability

trillstheir and,[r]s ofmost trills importantly,

and,

2002).most importantly,

the the methodological the methodolo

reported an average of 20 ms. for taps and 60 ms.

rolling for trills. The length

(Solé of the trill

Because is affected by the

production mechanis

rences. These or small changes in the create production trills, which could be due

sto(Solé

contextual 2002).

challenges

prosodic

following

Because they the

challenges

present

features,

vowel:

production It

in

theyis shorter

their

a favorable

before

mechanism

presentanalysis in [i] andof environment

longer

trills is before

quite [a] for

(Solé

complex the instability

2002).and requires of this sound and

eatures,

the creation create of anewfavorable variants.

Assibilated environment

and Instandard

fact,small the for thetheir

rich

rhotics

(see Methodanalysis

4 instability

literature

tend toin

precise

alternate ofsection).

on

(see

this

rhotic

Method

articulatory

sound

synchronically variationand section).

and aerodynamic conditions, small ch

andin different

diachronically dialects

(Solé 1992). of

atory and Acoustically,

aerodynamic conditions,

Acoustically,

the taponand the

the variation

tap changes

trill and share the the their

trill

perceptiblesame production

share characteristics:

the same

acoustic can lead

characteristics:

differences. A loweredto These third

A lowered

small formant

changes thirdin theforp

ants.

Spanish In fact, the

provides These rich

Synchronically,literature

evidence forchanges

apical rhotic

the instability

trills exhibit in

of trills and,

non-trilled different

variants, dialects

mostwhich

taps, importantly,

approximants, of and the methodological

fricatives. Solé (2002)

ustic differences. small in the production of trills, could be due

ce for(Colantoni

the instability 2001)

theyperformed

(Colantoni

ofand atrillsbrief

study 2001)

and,

to periods and brief

most

replicate of

theocclusion,

periodsto

importantly,

phonological of

one occlusion,

occlusion

contextual

the methodological

variation or

between onefor occlusion

the

prosodicvoiced taptrills and for

features, andmore

the tapthan

create

fricatives. and

aone Her morefor the

favorable than one fo

environm

rchallenges

prosodic features, present create in a their

favorable analysis (see

environment Method for section).

the instability of this sound and

their trill.

analysis However, results

(see trill.

taps

showed

Method However,

and thattrills

section). taps

trills differ

may and intrills

become the duration

differthe

fricatives in (orof

the the

creationduration

segment,

assibilated) of new ofthe

if the

with segment,

taps

variants.

finely being

controlledInwith shorter

fact, taps

the being

articulatory than literature

rich trills.

shorter than on

newAcoustically,

variants. In the

fact, tap

the and

rich the

literature trill share on the same

rhotic variation characteristics:

in different Adialects

lowered of third formant

and Quilis (1993) Quilis

reported

the (1993) an average

reportedfor ofan 20average

ms. forSpanish

oftaps 20suggesting

and

ms. for

60formant

provides ms.

taps forand

evidence trills.

60 involve

ms.

The

for for length

the trills. ofThe

instability thelength

trill is of and,

of trills the t

or aerodynamic requirements trills are not met, that fricatives a less complex

p(Colantoni the trill 2001) share

and brief same

periods characteristics:

of occlusion, A

onelowered occlusion thirdfor the the tap and more than one for the

des evidence affected for the

articulation

by affected instability

following and allow

by the ofa

vowel: trills

wider

following It theand,

range

is shorter ofmost

vowel: importantly,

oropharyngeal

before

It challenges

is shorter[i] pressure

andone before

longer

they methodological

variation

[i]before

present and inthan longer

[a] trills.

their(Solé Thus,

before 2002).

analysis assibilated

[a](see(Solé 2002). section

Method

f periods of occlusion, andone occlusion infor tap and ofmore than for the

ytrill. However,

present taps

inAssibilated

their analysis and

trills

(see

Assibilated

differ

Method

standard and

the

rhotics

duration

section).

standard 4 tendbeing

the segment,

rhotics

to alternate 4 tendthan

Acoustically,

with

synchronically

to alternate

taps

the tap

being shorter than trills.

synchronically

and the diachronically

trill and sharediachronically

(Solésame ch

the

ills differ

Quilis (1993) in the duration

reported anofshare the

average segment, ofsame20 withms. taps

for taps andshorter 60 ms. for trills.

trills. The length of the trill is

lly, the 1992).tap and the

Synchronically,

1992). trill Synchronically,

apical the trills exhibit

apicalcharacteristics:

non-trilled

trills exhibit

(Colantoni A

variants,lowered

non-trilled taps, third

variants, formant

approximants, taps, approximants,

and fricatives.and Solé fricatives

average

affected by ofthe 20 1following

ms. Thefor taps

distribution vowel: and

of trills 60

It isms.

and shorter

taps is forfurthertrills.

before

discussedThe[i]inand length

Hualde longer of 2001)

(2005). thebefore trilland is brief

[a] (Solé

periods

2002).

of occlusion, one occlusio

1) and(2002) brief periods

performed of

(2002) occlusion,

a isstudy

performed one occlusion for the tap and more than one for the

andto replicate

a study thetoof[a]

phonological

replicate trill. the phonological

variation

However, when wetaps between variation

and voiced

trills between

differ trills

wein and

thevoiced fricatives.

duration trillsofand thefrica

segm

2 Since there variation affecting the system rhotics (Hualde 2005), refer to ‘standard’ variants mean prestige

vowel: It is shorter before [i] longer 4 before (Solé 2002).

taps Assibilated

and

Her trills

results

4 3tend

and

differforms standard

Her in

showed

used in careful rhotics

the duration

results

andthat

speech, prescribed

showed

trills of themay

tend byto

segment,

thatbecome

schools

trills

alternate

and used by

with

may taps

fricatives

Quilis

synchronically

become

newscasters.

being

(1993) shorter

(orreported

fricatives

assibilated)

and

thanan

diachronically

trills.

(oraverage

ifassibilated)

the finely

of 20 ms.

(Solé

ifofcontrolled

thefor finely

taps and contr60

ndard rhotics

1992). Synchronically, Lipski to(1994)alternate

apical Hualde

trills synchronically

(2005) discussed

exhibit non-trilled other and diachronically

(non-standard)

variants, realizations

taps, (Solédorsalization

including

approximants, and and pre-aspiration

fricatives. the

Solé

eported an

articulatory average or

trill, of

articulatory20

aerodynamic

neutralization,ms. for taps

or aerodynamic

retroflexion, and

requirements 60

strengthening ms. of for

requirements

for trills

rhotics trills.

in

affected codas The

arefricatives.

not

forthe

and

by length

met,

trills

onset of

suggesting

are not met,

clusters.

following the trill

vowel: thatis

suggesting

Itfricatives

is shorter that

involvefricatives

before a[i] and involo

cal

(2002)trills exhibit4non-trilled

performed aItstudy

Solé to

(1992) actually variants, refers totaps,

replicate theand

word-final approximants,

phonological

rhotics as “trills”variation and

but, between

as stated earlier, we Solé voiced

prefer trills and

to use Hualde’s (2005)fricatives.

neutral term

following less complexvowel: is

less

“rhotic”. shorter

articulation

complex before

Solé also refers and [i]

articulation

allow

to assibilated longer

avariants

wider

andvoiced as before

allow

range

“fricatives”. [a]

a wider

of (Solé

oropharyngeal

Assibilated range2002). of oropharyngeal

and pressure rhotics

standard variationpressure

4 tend than variation

totrills.

alternate thansy

to replicate

Her the phonological variation between trills and fricatives.

d andresults standard showed rhotics that 4 tend trills to may alternate become fricatives

synchronically (or and assibilated)

diachronically if the(Solé finely controlled

t trillsThus,

articulatory mayassibilated

become Thus, rhotics

assibilated

fricatives occur (or rhotics

when

assibilated) the

occur vibratingwhen 1992).

trillsif approximants,

the the

tongue-tip

finelyvibrating

Synchronically,

met, controlled

failstongue-tip

to make apical fails

contact

trills to exhibit

make

with the contact palate,

non-trilled with orvariants

the pala

nically, apicalortrills aerodynamic

exhibit non-trilled requirements variants, for taps, are

(2002)

not

performed

suggesting

and fricatives.

a study

that fricatives

Solé involve a

to replicate the phonological variat

micless requirements for trills and are not met, suggesting that fricatives involve a

ed a complex

study to replicate articulation the phonological allow a widervariation range of oropharyngeal

between Her voiced

resultsthan trills

showed

pressure

and variation than trills.

fricatives.

that trills may become fricatives (o

and allow

Thus, assibilated a wider range of oropharyngeal pressure variation trills.

howed that trillsrhotics may become occur when the vibrating

fricatives (or assibilated)tongue-tip if

articulatory

fails theorto finely

make contact

aerodynamic controlled with the palate, or

requirements for trills are not m

ccur when the vibrating tongue-tip fails to make contact with the palate, or

aerodynamic1 The distribution 1

requirements The of distribution

trills

forand trills taps of is

are trills

further

not and

met,tapsdiscussed isless

suggesting further in Hualde

discussed

that (2005).

fricatives

complex articulation and allow in Hualde involve (2005). a a wider range of orophLanguages 2020, 5, 38 3 of 21

rhotics occur when the vibrating tongue-tip fails to make contact with the palate, or when apical

vibration fails, allowing the high velocity air to flow continually through the aperture generating

frication (Solé 2002). She further stated that assibilated rhotics in phrase-final position result from the

difficulty of sustaining trilling with the lowered decreased subglottal pressure that occurs at the end of

a statement.

Since this is a natural phenomenon, Solé (2002) argued that the co-occurrence of trilling and

frication (or standard and assibilated rhotics) should be a common cross-linguistic pattern. In fact,

rhotic assibilation (mainly in phrase-final position) has been reported in many dialects of Spanish

(Blecua and Cicres 2019; Canfield 1981; Quilis 1981), in other Romance and non-Romance languages

such as Brazilian Portuguese (Silva 1996), Czech (Howson et al. 2014), and in Farsi (Ladefoged and

Maddieson 1996). Solé (2002) replicated in the laboratory the variation observed in different languages.

1.2. Sociolinguistic Literature on Rhotic Assibilation in Mexico City

Assibilated taps and trills were first studied in Mexico City by Lope Blanch (1967). The author

(Lope Blanch 1967) argued that assibilation was a recent phenomenon that appeared after the 1950s

in the speech of women. He suggested that assibilation might have been imported from Spain,

because it had been observed there and in several other Latin-American countries. Lope Blanch (1967)

proposed that rhotic assibilation is a natural process in the evolution of the phonological system of

languages. Unfortunately, this last point was not developed further, but it is explored in the laboratory

by Solé (2002), summarized above.

The first synchronic sociolinguistic analysis of rhotic assibilation in Mexico City was published by

Perissinotto (1972). The study was based on 110 h of recorded conversation (the number of participants

was not stated) collected between 1963 and 1969. His results showed a high overall percentage of

assibilation (68.2%). Female speakers had a higher rate of the assibilated rhotic [ř] compared to their

standard variant [r] ([ř] 81.8% vs. [r] 18.2%) while male speakers had a reverted pattern of variation:

A higher percentage of the standard variant compared to the assibilated one ([r] 61.1% vs. [ř] 38.9%).

By comparing the distribution of the assibilated variant across age and socio-economic status, Perissinotto

(1972) found that assibilation was more common in the younger age group and in the high and middle

socio-economic levels. In other words, assibilation was a prestigious innovative variant adopted by

women of the higher classes.

More than three decades after the first study, Martín Butragueño (2006) performed an analysis

of rhotic assibilation in 54 native speakers of Mexico City. The overall percentage of assibilation in

absolute final position was 27%, compared to the 68.1% reported by Perissinotto (1972). A multivariate

analysis of rhotic assibilation showed a number of linguistic and social factors that favored assibilation:

(1) Absolute final position; (2) formal style; (3) mid and high education; (4) older generation; and (5)

females. Martín Butragueño (2006) claimed that given the lower percentage of assibilation found in his

study, as compared to Perissinotto’s (1972), rhotic assibilation seemed to be a receding case of language

change. This conclusion was reinforced by the fact that assibilation was more frequent in older women,

followed by the adult and younger groups (36%, 32%, and 17%, respectively). This is a tendency in

the other direction of what Perissinotto (1972) had found with assibilation being more frequent in

younger speakers, followed by adults and older speakers (73.5%, 64.5%, and 31.3%, respectively).

The comparison of assibilation found by Perissinotto (1972) and Martín Butragueño (2006) seems to

indicate that rhotic assibilation was a short-lived fashion in Mexico City.

Martín Butragueño’s (2014) second study analyzed the speech of 54 interviews and reading tasks

from the Sociolinguistic Corpus of Mexico City. The subjects were distributed along the different

social categories of age, sex, and education level. The study took into consideration all rhotic positions

including coda, onset and consonant cluster, word final, and absolute final. A multivariate analysis

confirmed what had been reported previously for rhotic assibilation. Presented in order of importance,

assibilation was favored by: (1) Phrase-final position; (2) interview (as opposed to reading); (3)

consonant clusters (especially /tr/); (4) people with medium level of instruction (10–12 years); (5) femaleLanguages 2020, 5, 38 4 of 21

speakers; and (6) older speakers (55+ years old). Other coda positions were not selected as significant

by the multivariate analysis and the author reported very few cases of assibilation in positions other

than absolute final and in consonant cluster /tr/.

Languages 2020, 5, x FOR PEER REVIEW 4 of 21

Martín Butragueño (2014) presented some spectrograms of trill and taps to illustrate the different

types of rhotics found in Mexico

selected City Spanish.

as significant by the Besides the standard

multivariate analysis variants,

and the author he alsoreported

found approximant

very few cases of

assibilation in positions other than absolute final and in consonant

variants, which the author defined as weakened versions of standard rhotics, and assibilated rhotics. cluster /tr/.

He proposed that rhotic Martín Butragueño

assibilation be (2014) presented

described some spectrograms

as change of trill and taps

from an approximant to atofricative

illustratesound.

the different

types of rhotics found in Mexico City Spanish. Besides the standard variants, he also found

According to theLanguages

author, this becomes

2020, 5, xvariants,

evident in the cases where the rhotic starts as an approximant4 of 21

FOR PEER which

REVIEWthe author defined as weakened versions of standard rhotics,

approximant and

(with a clear sonority bar and no noise) and continues as a fricative with high frequency noise and an

assibilated rhotics. He proposed that rhotic assibilation be described as change from an approximant

almost inexistent F0.

selected

to However,

a fricative as demonstrated

as significant

sound. According to theby

by the multivariate Soléanalysis

author, (2002) in

and

this becomes thethe

laboratory,

author

evident there

reported

in the isvery

cases where compelling

fewrhotic

the casesstarts

of

assibilation

cross-linguistic evidence in positions

suggesting(with

as an approximant other than

that atrills absolute

clearalternate final

withand

sonority bar and in consonant

fricatives

no noise) (orand cluster

assibilated /tr/.

continuesvariants),

as a fricativeso itwith

is high

Martín

plausible that assibilated

frequency Butragueño

rhotics

noise result (2014)

and anfrom presented

“a failure

almost some spectrograms

of sustaining

inexistent F0. However, of

as trill

trilling withandthetapslowered

demonstrated to illustrate the

decreased

by Solé different

(2002) in the

types of rhotics

laboratory, thereatfound

isthe in Mexico

compelling City Spanish. Besides the standard variants, hewith

alsofricatives

found

subglottal pressure that occurs end of across-linguistic

statement” evidence

(Solé 2002).suggesting that trills alternate

approximant

(or assibilated variants,

variants), whichso it the author defined

is plausible as weakened

that assibilated rhoticsversions

result from of standard

“a failure rhotics,

of sustaining and

assibilated

1.3. Sociolinguistictrilling

Literature rhotics.

with on theRhoticHe

lowered proposed

Assibilation that

decreased in rhotic assibilation

the Statepressure

subglottal be

of Chihuahua, described

that occurs Mexicoas change from an

at the end of a statement” (Soléapproximant

to2002).

a fricative sound. According to the author, this becomes evident in the cases where the rhotic starts

Rhotic assibilation reached the

as an approximant (with northa clear of sonority

Mexico after bar and theno1960s,

noise)with the first study

and continues conducted

as a fricative with high

in Ciudad Juárez1.3.frequency noise

inSociolinguistic

1998 (Amastae and an

Literature almost

et al.on1998). inexistent F0.

This studyinshowed

Rhotic Assibilation However, as

the State ofthat demonstrated

assibilation

Chihuahua, by Solé

Mexicowas present (2002) in the

laboratory, there is compelling cross-linguistic

in Ciudad Juárez, but with a lower frequency of overall occurrence than reported in Mexico City. evidence suggesting that trills alternate with fricatives

Rhotic assibilation reached the norththat of Mexico afterrhotics

the 1960s, with the“a first studyofconducted

sustainingin

The percentage (or of assibilated

assibilation

Ciudad Juárez

variants), so

in 1998

in all final it is plausible

positions

(Amastae et al. (including

1998).

assibilated

This word

study final

showed

result

andthat from

phrase-final) failure

assibilation was

was 6%,

present

trilling with the lowered decreased subglottal pressure that occurs at the end of a statement” (Soléin

while the percentage Ciudadof assibilation

Juaréz, but in absolute

with a lower final position

frequency of was 22%.

overall Compared

occurrence than to the 68.1%

reported in reported

Mexico City. The

2002).

by Perissinotto (1972),percentage assibilation

of assibilation was in much lesspositions

all final frequent in Ciudad

(including word Juárez.

final and Amastae

phrase-final) et al.was (1998)

6%, while

theSociolinguistic

conducted a multivariate

1.3. percentage analysisofLiterature

assibilation

on 72onspeakers in absolute

Rhotic and final

Assibilation position

found in thethat was

State of22%.

assibilationCompared

Chihuahua, was

Mexico to the 68.1%

affected by: reported

(1) by

Gender: Higher rate of assibilated rhotics in women (women 28% and men 16%); (2) social class:(1998)

Perissinotto (1972), assibilation was much less frequent in Ciudad Juárez. Amastae et al.

Rhotic assibilation

conducted a multivariate reached analysisthe northon 72ofspeakers

Mexico after and the found 1960s,

thatwith the first study

assibilation conducted

was affected in

Greater percentage of assibilation in the higher socio-economic class as compared to the middle class 5by: (1)

Ciudad Juárez in 1998 (Amastae et al. 1998). This study

Gender: Higher rate of assibilated rhotics in women (women 28% and men 16%); (2) social class: showed that assibilation was present in

(21% and 18%, respectively);

Ciudad Juaréz, (3)

but age:

with Adults

a lower (36–55

frequency years) of and older

overall participants

occurrence than (56+) showed

reported in Mexico higher

City. The

Greater percentage of assibilation in the higher socio-economic class as compared to the middle class5

rates of assibilation (31% and

percentage

(21% and 18%,

19%,

of assibilation respectively)

respectively); in all(3) final than

age:positions

younger

Adults (36–55 (including participants

years)word final(15%);

and older and and (4)

phrase-final)

participants

education:

(56+)was showed 6%, while

higher

Assibilation wasthe more percentage of assibilation in absolute final position

rates of assibilation (31% and 19%, respectively) than younger participants (15%); and (4) and

frequent in speakers with higher levels of was

formal 22%. Compared

education to the

(university 68.1% 23% reported

education: by

Perissinotto

high school 14%).Assibilation

All these effects(1972),

was more assibilation

suggested

frequentthat was much

assibilation

in speakers less frequent

withwas higher also in Ciudad

a prestigious

levels Juárez.

of formal education Amastae

variant in(universityet al.

Ciudad 23% (1998)

Juárez. Amastae conducted

et al.

and high a multivariate

(1998)

school argued

14%). All analysis

that on 72 suggested

assibilation

these effects speakers

in Ciudad and

that found

Juárez that

assibilation wasassibilation

a recent

was was affected

also a “change

prestigious from by: (1)in

variant

Gender:

Ciudad Higher rate

Juárez. Amastae of assibilated

et al. (1998) rhotics in women (women 28% and men 16%); (2) social class:

above” (Labov 1972) imported from Mexico City argued

by thethat higher assibilation

classesinand Ciudad Juárez was

transmitted bya women.

recent “change

Greater percentage

from(1972),

above”a (Labov of assibilation

1972) importedin the higher

from socio-economic

Mexico change City by that class as

the higher compared

classes to the middle

and transmitted class 5

by

According to Labov (21% and 18%,

change

respectively);

from above

(3) age:

is

Adults

a linguistic

(36–55from years)aboveand older

enters the language from

women. According to Labov (1972), a change is a participants (56+) showed higher

above the level of ratesconsciousness;

of assibilation that

(31% is,

and speakers

19%, are

respectively)generally than younger the linguistic

aware ofparticipants linguistic change

(15%); form and

that enters

and

(4) they the

education:

language from above the level of consciousness; that is, speakers are generally aware of the linguistic

manipulate its use depending

Assibilation was on more thefrequent

contextinand/or their interlocutors. The upper classes (university

use these 23%

form and they manipulate its usespeakers

depending with onhigher levels of

the context formal

and/or theireducation

interlocutors. The upper

new linguistic formsandclasses use these new linguistic forms in order to differentiate themselves from the classes

in

high order

school to differentiate

14%). All these themselves

effects suggested from the

that lower

assibilation classes,

was while

also a lower

prestigious lowervariant in

classes,

use these forms Ciudad

inwhile

order Juárez.

to soundAmastae more et al.

formal(1998) andargued

similar that toassibilation

the upper

lower classes use these forms in order to sound more formal and similar to the upper classes. in Ciudad

classes. Juárez was a recent “change

Twenty years fromafterabove”

Twenty (Labov

Amastae’s

years after 1972)

study, imported

Amastae’s Mazzaro from

study, and Mexico

González

Mazzaro CityGonzález

and by

dethe Anda higher(2019)

(2019) classes and transmitted

investigated

investigated the by

the relationship

women. According to Labov (1972), a change from above is a linguistic change that enters

relationship between between thethe perception

perceptionand and production

production ofofrhotic rhotic assibilation

assibilation [ř] and [ř] deaffrication

and deaffrication of the

of the voiceless

language from

post-alveolaraffricate above the level

affricate [[ ʃ ]] in of consciousness; that is, speakers are generally aware of the linguistic

the voiceless post-alveolar inthe theSpanish

Spanish of Chihuahua,

of Chihuahua, Mexico. Thirty-three

Mexico. native Spanish

Thirty-three native speakers

form

from and

the they

state manipulate

of Chihuahua its completed

use depending on the and

production context and/or tasks

perception their to interlocutors.

establish The upper

whether those

Spanish speakers from use

classes the these

state new of Chihuahua

linguistic completed production and perception tasks to establish

that produced the variants wereforms able to in perceive

order to them.

differentiate themselves

The production data from

werethe lowerby

elicited classes,

asking

whether those that while produced

lower classes theuse variants

these wereinable

forms ordertotoperceive

sound more them. formal Theandproduction

similar data were

participants to narrate the fairy tale Caperucita Roja ‘Little Red Riding Hood’ to and thebyupper

asking classes.

them to

elicited by asking participants

Twenty years toafter

narrate Amastae’s the fairy study, tale Caperucita

Mazzaro and Roja ‘Little

González (2019) Red Riding Hood’

investigated the and

relationship

talk about their favorite food. Results showed that the overall percentage of [ř] production was

by asking thembetween to talk about

greater than their

the perception

that of [ʃ]favorite

and production

(17.15% food. Results

and 11.83%, of rhotic showed

assibilation

respectively). that the

The[ř] overall

and

authors percentage

deaffrication

explained of the

that ofvoiceless

the [ř]

increased

production was post-alveolar

greater than affricate

that of [[ ʃ ]

] in the

(17.15% Spanish

and of Chihuahua,

11.83%, Mexico.

respectively).

overall rate of [ř] might be due to assibilation only being investigated in absolute final position, which Thirty-three

The authors native Spanish

explained speakers

that

from

the increased overall is thethe

rate state

context of

of [ř] Chihuahua

might

where most beof completed

due theto production

assibilation

variation occurs.only andbeing

The perception

social tasks

investigated

factors that to establish

in absolute

turned out to whether

befinal those

significant

that produced the variants were able to perceive them. The production data were elicited by asking

position, which iswere the gender

contextand wheregeneration,

most of withthefemale

variation and younger

occurs.speakersThe social favoring

factors thethat

use of assibilation.

turned out The

participants to between narrate the fairy tale Caperucita Roja ‘Little Red Riding was Hood’ and subtle; by asking them to

to be significant relationship

were gender and generation, production and female

with perception andofyounger assibilation speakersvery favoring theoverall, use the

talk about their

perception of the favorite

variantfood. was Results

very lowshowed

(9.1%). that

Those the who overall

producedpercentage

assibilationof [ř] wereproductionnot thewas ones

of assibilation. Thegreater relationship

than that ofbetween [ʃ] (17.15% production

and 11.83%, and perception

respectively). Theof assibilation

authors explained was that verythe subtle;

increased

overall rate of [ř] might be due to assibilation only being investigated in absolute final position, which

is the context where most of the variation occurs. The social factors that turned out to be significant

5 were did

Amastae et al. (1998) gender and generation,

not analyze the speech with female and

of participants younger

of lower speakers favoring

socio-economic class. the use of assibilation. The

relationship

5 Amastae et between

al. (1998)production

did not analyze and theperception of assibilation

speech of participants of lowerwas very subtle;

socio-economic class.overall, the

perception of the variant was very low (9.1%). Those who produced assibilation were not the ones

5 Amastae et al. (1998) did not analyze the speech of participants of lower socio-economic class.Languages 2020, 5, 38 5 of 21

overall, the perception of the variant was very low (9.1%). Those who produced assibilation were not

the ones that perceived it the most, which seemed to suggest that rhotic assibilation was below the

level of consciousness and social awareness (Labov 2001).

To the best of our knowledge, no other sociolinguistic studies have been done on rhotic assibilation

in this geographic area. The present research will further investigate the social and linguistic factors

that affect the production of this variable. We also add another layer of analysis to increase the accuracy

of coding of tokens, by supplying the auditory classification of tokens with a spectrographic analysis.

Acoustic information will allow us to identify if there are other variants that could also be alternating

with assibilated rhotics.

This study is designed to explore different aspects of the production of rhotic assibilation in the

state of Chihuahua/El Paso, TX speech community6 . Our specific questions are the following:

i. What is the current state of rhotic assibilation more than two decades after the first (and only)

study was done? In this study, we expect to find a lower frequency of rhotic assibilation, since

previous studies on this same dialect (Amastae et al. 1998) stated that this variable was receding.

ii. Which rhotic variants are found in Chihuahua Spanish? Given that Amastae et al. (1998) suggested

that assibilation is receding, we predict that we will find a much smaller percentage of rhotic

assibilation than he did in 1998, and a large percentage of standard variants (taps and trills). It is

possible that we could find other variants reported in other dialects of Mexican Spanish such as

approximants, retroflex, and fricatives (Martín Butragueño 2006).

iii. What are the most important linguistic and social correlates of rhotic assibilation? Gender is

expected to be one of the most significant factors that influence the variable under study. The

fact that female speakers favor assibilation has been consistently reported by Amastae et al.

(1998); Lope Blanch (1967); Martín Butragueño (2006); and Perissinotto (1972). Besides gender,

we anticipate older speakers to produce more assibilation than the other age groups, which is

due to the receding status of the variant (Amastae et al. 1998). The literature on rhotic assibilation

agree that the phrase-final position is the most favoring phonetic context for assibilated rhotics.

Thus, in this study, we focus on rhotic production in absolute final position. Finally, the preceding

vocalic context was found to be significant in our previous analysis of rhotic assibilation (Mazzaro

and González de Anda 2016), so we predict that with more data, this factor will show a clearer

and more robust effect.

iv. Does being a Spanish-English bilingual affect the use of this variable? Previous work (Dalola

and Bullock 2017) found that being bilingual affects the social perception and production rates of

variables in the L2. However, our participants are all L1 speakers of Spanish, so we do not expect

the L2 English to affect the rate of assibilation in bilingual compared to monolingual speakers.

v. What is the effect of the formality of the task (style): Reading vs. narrative vs. conversation on

the occurrence of assibilation? Given the prestige attached to assibilated rhotics (Amastae et al.

1998; Perissinotto 1972), we predict that tasks that are more formal would elicit higher instances

of assibilation. Therefore, the reading task will elicit a higher percentage of assibilation than

the narrative and the informal conversation. As the formality of the task decreases, so will the

frequency of assibilated rhotics.

vi. Does assibilation remain a prestigious feature of speech? We expect that rhotic assibilation will

continue to be a prestigious feature of speech. This is based on the vast amount of literature that

report the assibilated variant to be used in higher social classes and subjects with higher levels of

formal education (Amastae et al. 1998; Martín Butragueño 2006, 2014; Perissinotto 1972).

6 We consider El Paso, TX part of the state of Chihuahua’s Spanish-language speech community because of their geographic

proximity (separated only by the Rio Grande River). We are aware that there is lack of research that compares the Spanish of

the state of Chihuahua and that of El Paso, but we posit that they are one dialect, at least at the phonetic/phonological level.Languages 2020, 5, 38 6 of 21

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Speakers

Participants of this study are native Spanish speakers recruited in the El Paso, Texas—Ciudad

Juárez, Mexico border area. A total of 58 subjects participated in this study: 36 women and 22 men, with

an age range between 18 and 69 years. To compare our data with Amastae et al.’s (1998) generational

groups, the participants were divided into four groups: Generation 1: 56.

Participants were asked to complete an adult language background questionnaire that elicits

information about their place of birth, language(s) of schooling, and language use. The questionnaire

contained a section that asked for participants’ self-proficiency ratings in both Spanish and English,

and only those who reported to use mostly/only Spanish in their daily everyday interactions (at home,

at work, and in social situations) were selected to participate in the study. We considered bilingual

those participants who reported to know another language and self-assessed their English knowledge

as higher than basic. The demographic information of the participants considered in the statistical

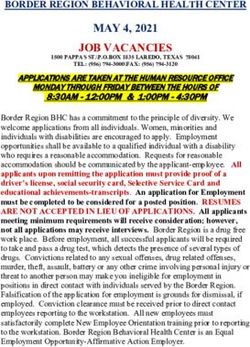

analysis is presented in Table 1.

Table 1. Participants’ demographic information.

Participants’ Information

Participants n 58

Age range in years 18–69

Generation 1 (56 years) n 5 (5 females)

Male: Female n 22:36

Median/Mean age in years 22/30

Ciudad Juárez (25),

From location n El Paso, TX (20),

Chihuahua—Capital (5), Chihuahua—Interior (Delicias, Parral, Balleza,

Cd. Guerrero, Cuauhtémoc, Jiménez) (8)

Bilingual: Monolingual n 29:29:00

All subjects gave their informed consent for inclusion before they participated in the study. The

study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and the protocol was approved by

the Ethics Committee of the University of Texas at El Paso IRB (Project identification code [274707-10]).

Thirty-four participants were recruited at the University of Texas at El Paso (UTEP). Some were

students enrolled in beginner-level ESOL (English for Speakers of Other Languages). Seven participants

were students at the Universidad Tecnológica de Ciudad Juárez. The remaining 17 participants were

contacted using the ‘friend-of-a-friend’ technique (Milroy 1987), whereby potential informants are

contacted through common friends, an approach that is particularly appropriate for the community

under study.

Although rhotic assibilation in Mexican Spanish is a feature mainly observed in higher social

classes, specifically mid-high to high class (Amastae et al. 1998; Perissinotto 1972), our study also

includes participants of the mid-low or middle social classes. Most of the participants from El Paso

who attend UTEP fall within the mid-low or middle social classes. The participants from the state

of Chihuahua who attend UTEP are probably from mid to high classes, since it is very expensive for

Mexican citizens to afford college north of the border. However, because we do not have an accurate

tool to determine participants’ social class, we will not investigate the effect of this factor henceforth.You can also read