Combining in-school and community-based media efforts: reducing marijuana and alcohol uptake among younger adolescents

←

→

Page content transcription

If your browser does not render page correctly, please read the page content below

HEALTH EDUCATION RESEARCH Vol.21 no.1 2006

Theory & Practice Pages 157–167

Advance Access publication 30 September 2005

Combining in-school and community-based media

efforts: reducing marijuana and alcohol uptake among

younger adolescents

Michael D. Slater1,7, Kathleen J. Kelly2, Ruth W. Edwards3, Pamela J. Thurman3,

Barbara A. Plested3, Thomas J. Keefe4, Frank R. Lawrence5 and

Kimberly L. Henry6

Abstract sults suggest that an appropriately designed in-

school and community-based media effort can

This study tests the impact of an in-school reduce youth substance uptake. Effectiveness

Downloaded from http://her.oxfordjournals.org/ by guest on May 9, 2015

mediated communication campaign based on does not depend on the presence of an in-school

social marketing principles, in combination prevention curriculum.

with a participatory, community-based media

effort, on marijuana, alcohol and tobacco

uptake among middle-school students. Eight Introduction

media treatment and eight control communities

throughout the US were randomly assigned to Despite some encouraging downward trends, use

condition. Within both media treatment and of substances including marijuana and alcohol

media control communities, one school received remains widespread among American adolescents.

a research-based prevention curriculum and Early initiation is commonplace, with 14.6% of

one school did not, resulting in a crossed, split- eighth graders reporting marijuana use and 38.7%

plot design. Four waves of longitudinal data reporting alcohol use in the past year (Johnston

were collected over 2 years in each school and et al., 2002). Reducing the rate of early uptake is

were analyzed using generalized linear mixed especially important given evidence that early

models to account for clustering effects. Youth initiation is predictive of a variety of negative

in intervention communities (N 5 4216) showed outcomes (Grant and Dawson, 1997).

fewer users at final post-test for marijuana A premise of the present study, consistent with

[odds ratio (OR) 5 0.50, P 5 0.019], alcohol a social-ecological framework (Berkman and

(OR 5 0.40, P 5 0.009) and cigarettes (OR 5 Kawachi, 2000), is that the norms and expectations

0.49, P 5 0.039), one-tailed. Growth trajectory that influence substance uptake among younger

results were significant for marijuana (P 5 adolescents are formed through a variety of social

0.040), marginal for alcohol (P 5 0.051) and experiences, including experience in school and in

non-significant for cigarettes (P 5 0.114). Re- the larger community. Reinforcement of non-use

norms and expectations, therefore, should ideally

be echoed and reinforced across these social envi-

1

School of Communication, The Ohio State University,

ronments (Flay, 2000). In the present study, we test

Columbus, OH 43210-1339, USA, 2Department of an intervention that includes an in-school media

Marketing, 3Tri-Ethnic Center for Prevention Research and campaign reinforced by participatory, community-

4

Department of Environmental Health, Colorado State based media efforts. This intervention is crossed

University, 5HDD Methodology Center, The Pennsylvania with implementation of a research-based prevention

State University and 6Institute of Behavioural Science,

University of Colorado

curriculum in selected schools.

7

Correspondence to: M. D. Slater; There is evidence that carefully designed,

E-mail: slater.59@osu.edu community-wide anti-drug advertising efforts can

Ó The Author 2005. Published by Oxford University Press. All rights reserved. doi:10.1093/her/cyh056

For permissions, please email: journals.permissions@oxfordjournals.orgM. D. Slater et al.

reduce youth marijuana (Palmgreen et al., 2001a) roaches, their record is mixed (Merzel and D’Afflitti,

and cigarette (Farrelly et al., 2002) use, and that 2003). Participatory community efforts focused

community-wide anti-smoking advertising in on mobilizing media, events and other commun-

conjunction with in-school prevention curricula ication strategies have the potential to reinforce

can reduce smoking uptake (Flynn et al., 1992, in-school communication efforts. We therefore

1994). There are two primary challenges to the expected a main effect for the combined community/

effectiveness of such media-based prevention ef- in-school media treatment on reducing increase in

forts: obtaining sufficient exposure to the messages substance uptake.

to achieve measurable impact (Hornik, 2002), and Similarly, we expected the prevention curricu-

identifying and executing message strategies that lum intervention to reduce substance uptake as well

can achieve such impact given adequate exposure (Tobler and Stratton, 1997). As Flay (Flay, 2000)

(Worden, 1999; Pechmann et al., 2003). notes, however, prevention curriculum effects tend

Ensuring exposure to anti-drug messages is typ- to decay and may require reinforcement (e.g. via

Downloaded from http://her.oxfordjournals.org/ by guest on May 9, 2015

ically expensive, requiring paid advertising to en- media) elsewhere in the environment. Therefore,

sure delivery of the message to the desired audience. we also examined interaction effects of the media

However, the school environment provides a unique intervention and the school prevention curriculum.

opportunity to inexpensively ensure a relatively high

level of exposure to anti-use communication. In

Methods

addition, focusing communication efforts within a

school may influence youth perceptions of the norms

and expectations within an environment in which

Design, participants and data collection

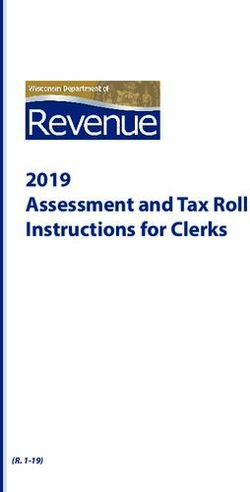

they spend much of their day. This study utilized a randomized community design

A variety of message strategies have shown some to assess the effects of the community/in-school

success in influencing substance use-related atti- media intervention, with eight media treatment and

tudes and behaviors (Flynn et al., 1994; Palmgreen eight control communities. Communities random-

et al., 2001a; Pechmann et al., 2003). In this study, ized to the media treatment condition received both

we emphasized non-use as an expression of per- community- and in-school media prevention ef-

sonal identity and the consistency of non-use with forts. Data were collected in two middle or junior

youth aspirations (Slater and Kelly, 2002), in the high schools in each of these 16 communities. In

belief that such messages would not be redundant each community (media treatment or media con-

with already existing information regarding sub- trol), one of the two schools also received an

stance risks, more likely to reinforce non-use norms

and less likely to generate reactivity (Ringold,

2002). Another advantage of this strategy is that 8 Media

8 No Media

Communities

the same messages could address a variety of (Community

Communities

(No coalition

substances (i.e. marijuana, alcohol and tobacco), coalition

or media)

media efforts)

whereas risk messages are typically substance

specific. Given the limited resources of most

communities and schools, developing effective

cross-substance prevention strategies is advanta-

Curriculum 8 Curriculum

geous (Griffin et al., 2003). Treatment Comparison

8 Curriculum 8 Curriculum

The school is nested within the larger commu- Treatment Comparison

Schools (In- Schools (In-

Schools Schools (no

nity (Flay, 2000): participatory, community-based school school

(All Stars treatment of

media plus media/ no

approaches may help change youth substance be- All Stars) All Stars)

only) any kind)

haviors (Aguirre-Molina and Gorman, 1996; Perry

et al., 2002), although, like media prevention app- Fig. 1. Study experimental design.

158Combining in-school and community-based media efforts

in-school prevention curriculum and the other did been prohibitively lengthy. Treatment and control

not, creating a crossed design (see Figure 1); as communities were located in each of the four major

noted below, assignment of schools receiving the regions of the US (northeast, southeast, midwest

prevention curriculum was not fully randomized. and west). Because of the complexities of imple-

Four waves of data collection were conducted: the menting and managing this 2-year intervention,

first prior to initiating the in-school curriculum, recruitment and implementation were staggered

the second immediately following the last session, over a 4-year period, following an initial start-up

the third early in the fall of the second school year, year. The first communities began intervention

and the fourth and final wave in late spring of the activities in the fall of 1999 and the last commu-

second year. Data collection in the control schools nities completed the intervention in spring 2003.

was matched as closely as possible to data collec- Communities that entered the project were randomly

tion times in the schools receiving the prevention assigned to condition using a group-matching

curriculum. strategy to minimize the potential for confounded

Downloaded from http://her.oxfordjournals.org/ by guest on May 9, 2015

Students (N = 4216) were recruited to the study effects due to random differences between treat-

using active consent procedures, required in this ment and control communities. Data on community

study given the provision of identifying informa- income, region, size, ethnic make-up, junior high

tion. Sixty-six percent of eligible students returned versus middle school configuration and readiness

signed consent forms and participated in at least one to engage as a community in prevention efforts

survey. A total of 68.6% of these participating (Edwards et al., 2000) were gathered from NCES

students provided data at all four measurement and other databases as well as from data collection

occasions; 16.8% provided data on three, 10.9% within each community. All possible assignment

provided data on two and 3.7% provided data on combinations were generated in the latter 2 re-

just one of the measurement occasions. Missing data cruitment years, including those communities pre-

were primarily the result of absence from school on viously assigned in earlier years (in the first year

the day of the survey or missed survey items. In pure random assignment was used for three com-

addition, the data for individual students who had munities). Treatment or control assignment was

indicators of inconsistent responding or exaggera- based on random selection of one of the combina-

tion at a given measurement occasion were removed tions in which no variables were different at P <

from the dataset. At any one measurement occa- 0.15 (from two such combinations in recruiting

sion, this equated to the removal of less than 2% of year 2 and from 10 such combinations in the

the students. The sample was approximately equal crucial recruiting year 3).

by gender (52% female/48% male). The majority of The two schools within each community were,

the sample was white (83.3%); 10.4% of respond- when possible, randomly assigned to either the

ents were African-American, 2.9% were Hispanic curriculum or no curriculum condition. However,

and 3.4% were of some other ethnic background. problems of scheduling and staffing in seven of the

As we were concerned with assessing students in 16 communities precluded assignment of a school

their first year of middle or junior high school, we to the curriculum treatment condition (usually be-

recruited sixth graders from the former and seventh cause key school staff members were new hires

graders from the latter (mean age at baseline = 12.2 and administrators were unwilling to burden them

years). As noted below, we balanced school/grade with a new curriculum). In such cases, school ad-

type between treatment and control conditions. ministrators provided written documentation to assure

Communities were recruited using the National us that assignment was not based on perceived

Center for Educational Statistics (NCES) database, need. As assignment to school condition, unlike

excluding the two largest census groupings, as the the media treatment, was not fully random, infer-

time required to gain approval for inclusion of a ences about prevention curriculum effects are qual-

prevention curriculum in larger districts would have ified accordingly. Because school curriculum was

159M. D. Slater et al.

of secondary concern (i.e. we wanted to examine tion, as discussed below, and adaptations were made

possible interactions of curriculum and media as needed.

intervention effects), this limitation does not One set of materials was developed for distri-

affect our analyses of primary interest. bution in the first year, with another set for the

second year in order to keep the campaign fresh.

Intervention design In the last year, schools in the media treatment

Social marketing principles were used to guide the communities were also offered the opportunity to

development of the media campaign to ensure a localize a poster with the campaign slogan for their

focus on influencing behavior change (Goldberg school by featuring a diverse group of students

et al., 1997; Kotler and Zaltman, 1971). Specifi- from that school. Typically, a school counselor

cally, primary and secondary research was used to or administrative support person was respons-

better understand adolescents’ attitudes, values and ible for distributing these media/social marketing

behaviors regarding substance use, and this knowl- materials.

Downloaded from http://her.oxfordjournals.org/ by guest on May 9, 2015

edge guided the message strategy for the in-school The community-based, participatory communica-

media campaign, ‘Be Under Your Own Influence’. tion effort had several components. First, half-day

Additionally, through focus groups and personal community readiness workshops were conducted,

interviews we learned what types of promotional involving people active in prevention efforts in the

items (the products) and media channels (the community as identified using a snowball recruit-

places) were valued and attended to by the adoles- ment approach (Thurman et al., 2003; Slater et al.,

cent audience. These materials accordingly included 2005). In these workshops, trained project staff

print materials such as a series of posters as well as reviewed results of the community readiness assess-

promotional items such as book covers, tray liners, ment that had already been conducted to facilitate

T-shirts, water bottles, rulers and lanyards. assignment of communities to treatment condition

The central premise of our message strategy was and worked with community prevention leaders to

that the primary task of adolescence is attaining identify prevention strategies appropriate to their

greater independence and autonomy. A principal community’s level of readiness. This was followed

benefit of substance use therefore is likely to be the by a half-day session focused on community media

accompanying feeling of rebellious noncompliance by providing training in the use of campaign media

and independence. A principal cost is the risk to materials (including brochures, press releases, ideas

aspirations associated with greater maturity and for special events, posters and radio public service

autonomy. Our campaign was intended, therefore, announcements) (Hansen, 1996). Community pre-

to emphasize the inconsistency of drug (primarily vention leaders developed their own strategies for

marijuana) and alcohol use—and to a lesser extent this media effort and used whatever materials they

tobacco use—with one’s aspirations (Oman et al., either chose or developed on their own. Our in-

2004). In addition, the campaign sought to reframe tention was that community efforts would reinforce

substance use as an activity that impaired rather in-school efforts for youth by underscoring an anti-

than enhanced personal autonomy (Williams et al., drug community norm. A part-time project staff

1999). person developed new materials and provided on-

We thereby sought to decrease the cost and going support as needed for these community

increase the benefit of the non-use choice by ado- media efforts.

lescents. We also often used images such as rock- The in-school intervention was a research-based

climbing and four-wheeling that were appealing to cross-substance prevention curriculum, All StarsTM,

risk-oriented, sensation-seeking youth (Palmgreen which emphasizes non-use norms, commitment not

et al., 2001b). The campaign was monitored via to use and school bonding (Hansen et al., 1996;

qualitative and quantitative process evaluations Harrington et al., 2003). The curriculum involved

several times throughout campaign implementa- 13 sessions in the first year and seven booster

160Combining in-school and community-based media efforts

sessions in the second year; teachers were trained procedure incorporated in SAS version 9.0 (SAS

by experienced All StarsTM staff. Institute, Cary, NC).

The imputation model was as rich as our analytic

Measures model (Schafer, 1999), reducing the chance that the

For the lifetime incidence of alcohol intoxication imputation would bias the results. In addition, the

score, students responded to three questions: ‘‘Have imputation model included auxiliary items that

you ever gotten drunk?’’, ‘‘How old were you the were not used in the analyses, but were useful in

first time you got drunk?’’, ‘‘How often in the last predicting missing values (i.e. attitudes, normative

month have you gotten drunk?’’. For the lifetime beliefs, demographic variables, etc.) The parameter

smoking score, students responded to three ques- estimates reported below reflect combined esti-

tions: ‘‘Have you ever smoked cigarettes?’’, ‘‘Do mates from analyses done on 10 imputed data

you smoke cigarettes?’’, ‘‘In using cigarettes are sets. The 10 data sets yielded a relative efficiency

you a ... (non-user, very light user, light user, estimate of 95% for our parameter estimates

Downloaded from http://her.oxfordjournals.org/ by guest on May 9, 2015

moderate user, heavy user or very heavy user)?’’. (Rubin, 1987).

For the lifetime marijuana score, students responded

to five questions: ‘‘Have you ever tried mari- Statistical analysis

juana?’’, ‘‘How often in the past month have you The unit of randomization in our design (the

used marijuana?’’, ‘‘How old were you the first time community) was used to compute degrees of

you used marijuana?’’, ‘‘Have you ever used mar- freedom for the test statistics (Murray et al., 1998,

ijuana when alone?’’, ‘‘In using marijuana are you 2004). This approach permits relatively unqualified

a ... (non-user, very light user, light user, moderate assertions of support for causal claims, in that the

user, heavy user or very heavy user)?’’. Items were degrees of freedom reflect a true community-

from the American Drug and Alcohol SurveyTM, randomized experimental design.

used by permission of the Rocky Mountain Behav- The model used was a four-level (measurement

ioral Science Institute. occasion within individual within school within

An affirmative response to any of the items community) random-intercept model. Random-

resulted in a score of ‘‘1’’ for that particular lifetime slope models were initially attempted, but failed

use score, while students who indicated in all the to converge because the variance among slopes

items that they had never tried the substance re- approached zero. Slopes were therefore treated as

ceived a score of ‘‘0’’. As one would expect, given fixed (global tests of model fit indicated the fixed

that students experimenting with use might endorse slope model fit the data better than a random slope

past trial but not past month use, reliability across model). Two-stage analyses were not used to permit

these items was quite good, but not perfect. The estimation of random slopes because such analyses

a values for the lifetime marijuana use measure ignore variability in subordinate cluster sizes

varied from 0.88 to 0.92 across the four waves; (school size was quite variable in this study, so

a varied from 0.83 to 0.88 for lifetime intoxication, this limitation would have distorted results in a non-

and from 0.88 to 0.90 for lifetime cigarette use. trivial way) and because of problems associated

The timing of the data collection varied among with estimation of standard errors in two-stage

participants. Therefore, our model was constructed analyses (Verbeke and Molenberghs, 2000). To

to allow for intervals of different lengths between address non-linearity issues, over-dispersion (i.e.

measurements (Brown and Prescott, 1999; Wallace conditional variance larger than implied by the

and Green, 2002). model) and the clustering effects, we used gener-

alized linear mixed models (McCullagh and Nelder,

Missing data 1989; Rotnitzky and Jewell, 1990; Hastie and

For our study, missing data were treated using Pregibon, 1993; Lee and Nelder, 1996; McCulloch

multiple imputation (MI). We employed the MI and Searle, 2001).

161M. D. Slater et al.

The intra-class correlations (ICCs) indicated that One test of our hypothesis regarding effects at

relatively little variation in the outcome variables the conclusion of our intervention is a test of the

(0.01% for marijuana, 0.02% for alcohol and 1.3% treatment’s main effect on Wave 4 intercepts; the

for cigarettes) was explained at the school level. model intercept was placed at the last measurement

Clustering at the community level accounted for occasion (Raudenbush and Bryk, 2002). This test

5.7% of the variance for marijuana, 8.5% for has the advantages of superior statistical power and

alcohol and 19.5% for cigarettes; all analyses in- easily interpreted odds ratios (ORs). The treatment 3

corporated the random intercepts for individual, time interaction provides useful additional infor-

school and community. mation regarding the effect of treatment on the

The fixed-effects portion of the model treated linear rate of change. It also provides a more rig-

substance use as a function of media treatment, orous, although less statistically powerful, test of

curriculum treatment, time and treatment interact- hypotheses, because it is not subject to baseline

ing with time. Other interactions (e.g. media treat- differences in outcome measures. (However, it

Downloaded from http://her.oxfordjournals.org/ by guest on May 9, 2015

ment 3 school curriculum treatment and the should be noted that these baseline differences did

various higher-order interactions) were also as- not approach statistical significance).

sessed. Only those interactions that were significant We report one-tailed tests of significance because

for at least one substance outcome were included in our hypotheses are directional and because we

the final model (summarized in Table I). conducted preliminary examination of the data

Table I. Fixed effects for four-level random effects models using Murray et al. d.f. recommendations

Log-odds SE t d.f. P OR

Marijuana

intercept ÿ1.528 0.214 ÿ7.14 14Combining in-school and community-based media efforts

prior to project completion to ensure that our inter- treatment communities at the last measurement

vention was not causing iatrogenic effects. Had occasion, i.e. substance use uptake for youth in

we observed such effects, the experiment would treatment communities was half or less than that

have been terminated. Therefore, use of two-tailed of control communities by Wave 4. The Wave 4

tests for these data is superfluous as effects results for the media treatment were clearly signif-

opposite the hypothesized direction would not icant for marijuana [t (14) = 2.30, P = 0.019] and

have had the opportunity to be assessed in this alcohol [t(14) = 2.72, P = 0.009, one-tailed]. Even

model. though the Wave 4 effects for cigarettes were

statistically significant, they were less robust than

were effects on the other substances [t(14) = 1.90,

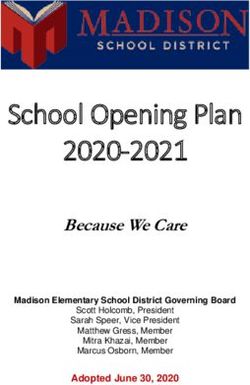

Results P = 0.039]. The percent of youth using each sub-

stance by study condition at Time 4 is shown in

Process evaluation and exposure Figure 1.

Downloaded from http://her.oxfordjournals.org/ by guest on May 9, 2015

manipulation check The treatment 3 time interaction, as noted above,

Qualitative results using in-depth interviews with provides a more rigorous though less statistically

key community coalition and school district partic- powerful and less easily interpreted test of treatment

ipants indicated that the community and in-school effect. For the media treatment 3 time interaction

media interventions were successfully implemen- on marijuana, effects were significant [t(14) = 1.89,

ted, although with some variation in intensity, in all P = 0.040]. The media treatment 3 time interaction

treatment communities. The mix of media and was marginally significant for alcohol [t(14) = 1.75,

communication approaches used varied based on P = 0.051] and was not statistically significant for

community interest, capabilities, resources and cigarettes [t(14) = 1.26, P = 0.114]. Figure 2

needs, consistent with a participatory model. Quan- illustrates the media treatment effect on rate of

titative assessment of treatment versus control ex- change in marijuana, alcohol and cigarette use.

posure differences was possible only with respect to Effects of the curriculum were statistically sig-

a sampling of advertisement-type messages that nificant at Wave 4 for each of the three substances

were used primarily in the in-school media in-

tervention. Three such messages were reproduced

in the evaluation instrument along with a foil (a

fake) message intended to reduce false recognition,

response set and research demand bias problems

associated with recognition measurement (Slater

and Kelly, 2002). After adjusting for recognition of

the foil, students exposed to the media campaign

were more likely to report recognition of selected

campaign messages at all post-test waves (Time 2,

OR=4.70, P < 0.0001; Time 3, OR=6.80, P <

0.0001; Time 4, OR=10.13, P < 0.0001).

Intervention effects

Results using community as the unit of random-

ization (Verbeke and Molenberghs, 2000) in a four-

level random effects model were supportive of

hypothesized community and in-school media ef-

fects (see Table I). The OR for using marijuana was Fig. 2. Percent of youth using each substance by study

0.50, for alcohol 0.40 and for cigarettes 0.49 for condition at final Wave 4 post-test.

163M. D. Slater et al.

as illustrated by Figure 2, culminating in the

relatively large Wave 4 treatment effects. Media

intervention effects on reducing cigarette initiation

were more problematic, as the analysis of traject-

ory effects was not significant. Effects on cigarette

uptake were less robust, perhaps because only some

messages included tobacco use, while all mentioned

drugs (or marijuana specifically) and alcohol.

A particularly encouraging dimension of this

intervention is that it appeared to influence several

substance outcomes, in particular marijuana and

alcohol use. The focus on autonomy and aspirations

(‘Be Under Your Own Influence’) was equally

Downloaded from http://her.oxfordjournals.org/ by guest on May 9, 2015

applicable to both substances. Such multi-substance

approaches are particularly advantageous given the

limited resources and time available in most school

Fig. 3. Community treatment effect on rate of change in

marijuana, alcohol and cigarette use (averaged growth curves settings (Griffin et al., 2003).

as a function of elapsed time baseline data collection). The apparent effectiveness of this media inter-

vention may be attributed to several factors. One is

(P < 0.005; Table I). These effects must be inter- the message strategy, emphasizing the ways that

non-use meets immediate adolescent needs re-

preted with caution given the imperfect randomiza-

garding autonomy, and both personal and social

tion of the curriculum treatment described above;

success. Another possibility is that the media in-

moreover, post hoc analyses suggested significant

tervention had the advantage of ubiquity. Among

baseline differences favoring treatment schools.

young teens, beliefs and attitudes are highly dy-

Curriculum 3 media treatment interactions were

namic and changes in beliefs and attitudes tend to

not statistically significant, indicating that the effect

decay (Resnicow and Botvin, 1993), even when the

of curriculum was additive rather than synergistic.

The curriculum 3 time interactions also were not interventions that trigger such changes are rela-

tively intensive. If so, a media intervention in the

statistically significant.

school which remains continuously visible may

serve to keep desirable attitudes salient, accessible

Discussion and more likely to influence behavior (Fazio et al.,

1989), even though the intervention at any one time

Results provide support for the effectiveness of in- cannot be considered an intensive one.

school media efforts combined with participatory Inferences regarding the school curriculum can-

communication efforts at the community level by not be confidently drawn given problems with

final post-test—the odds of uptake at Time 4 were random assignment of the curriculum. However,

approximately twice as high for previously non- this is not a significant concern with respect to our

using members of the control group compared to primary objective of testing the media intervention.

their counterparts in the community-based and in- The pattern of results in Figure 1 suggests treatment

school media treatment group. strategies are not contingent nor synergistic (i.e.

These effects were confirmed by the treatment 3 effectiveness of neither the media nor the curricu-

time interaction for marijuana and were marginally lum treatment depended on the presence of the

supported (at P = 0.051) for alcohol, testing differ- other treatment), although as one would expect

ences between slope trajectories. Initially smaller the strongest effects appeared to be in the com-

treatment/control differences grew larger over time, bined condition. Study results are also qualified by

164Combining in-school and community-based media efforts

possible selection bias associated with use of active We also found, based on coding a minimum of

consent, as some research suggests that at-risk six pre- and post-test interviews with community

youth disproportionately do not provide parental key informants, that there were impacts of the

consent (Unger et al., 2004). Also, as noted earlier, media intervention on community knowledge of

the data structure was most appropriately analyzed the substance use issue and marginally on com-

with random intercept rather than random slope munity climate (Slater et al., 2005). We are con-

models, which could not be estimated due to the ducting further research to identify paths of influence

minimal variability of these slopes. While the small for the in-school and community campaigns, and

ICC for slope variability (less than 1% of variance) to determine the relative contributions of the in-

suggests this should have little impact on results, school and the community campaign components.

it is a limitation on inference, as random slope In the meantime, these results suggest that

analyses provide the most complete analyses of appropriately designed in-school and community-

group randomized trials (Murray et al., 2004). based media efforts can significantly reduce youth

Downloaded from http://her.oxfordjournals.org/ by guest on May 9, 2015

During the period of this research the Office of substance uptake, and that such efforts can be used

National Drug Control Policy was engaged in an independently of, or in addition to, classroom

active media campaign on national television prevention curricula.

focused primarily on marijuana use prevention, and

the latter years of this effort also overlapped with

national advertising by the Legacy Foundation and

the truthTM campaign to discourage youth smoking.

Acknowledgements

The effects of these national campaigns on both

treatment and control communities should make for This research was supported by grant DA12360

a more conservative test of hypothesized intervention from the National Institute of Drug Abuse to the

impacts, but should not create any systematic bias. first author. The authors thank the research staff of

Another limitation of the present study is that the the Tri-Ethnic Center, Colorado State University,

relative contributions of the in-school media/social and project manager Linda Stapel for their efforts

marketing effort and the community-based commu- in executing this research project, William Hansen

nication efforts are impossible to disentangle within and Tanglewood Research for providing and

the media treatment condition. Clearly, the combi- implementing the in-school curriculum, and the

nation has considerable potential. However, costs administrators, teachers, students, and community

for taking the in-school intervention to wide-scale prevention leaders in study communities who made

dissemination would probably be much lower than this research possible.

for the community media effort.

From a research perspective, too, it is important

to establish the relative contributions of each pro- References

gram component (Flay, 2000). We do have evi-

dence that amount of exposure to the media Aguirre-Molina, M. and Gorman, D.M. (1996) Community-

materials within the treatment schools is predictive based approaches for the prevention of alcohol, tobacco and

other drug use. Public Health, 17, 337–358.

of treatment outcomes (Slater and Kelly, 2002). In Ajzen, I. and Fishbein, M. (1980) Understanding Attitudes

particular, we found that students from a subsample and Predicting Social Behavior. Prentice Hall, Englewood

of schools early in the study who recognized having Cliffs, NJ.

Berkman, L. and Kawachi, I. (2000) Social Epidemiology.

seen more of the campaign’s messages had greater Oxford University Press, New York.

aspirations inconsistent with marijuana use and that Brown, H. and Prescott, R. (1999) Applied Mixed Models in

that the effects of aspirations on marijuana use were Medicine. Wiley, Chichester.

Edwards, R.W., Thurman, P.J., Plested, B.A., et al. (2000)

mediated by intentions, consistent with the Theory Community readiness: research to practice. Journal of

of Reasoned Action (Ajzen and Fishbein, 1980). Community Psychology, 28, 291–307.

165M. D. Slater et al.

Farrelly, M.C., Healton, C.G., Davis, K.C., et al. (2002) Murray, D.M., Varnell, S.P. and Blitstein, J.L. (2004) Design

Getting to the truth: evaluating national tobacco counter- and analysis of group-randomized trials: a review of recent

marketing campaigns. American Journal of Public Health, methodological developments. American Journal of Public

92, 901–907. Health, 94, 423–433.

Fazio, R.H., Powell, M.C. and Williams, C.J. (1989) The role of Oman, R.F., Vesely, S., Aspy, C.B., et al. (2004) The potential

attitude accessibility in the attitude-to-behavior process. protective effect of youth assets on adolescent alcohol and

Journal of Consumer Research, 16, 280–288. drug use. American Journal of Public Health, 94, 1425–1430.

Flay, B.R. (2000) Approaches to substance use prevention Palmgreen, P., Donohew, L., Lorch, E.P., et al. (2001a)

utilizing school curriculum plus social environment change. Television campaigns and adolescent marijuana use: tests of

Addictive Behavior, 25, 861–885. sensation seeking targeting. American Journal of Public

Flynn, B.S., Worden, J.K., Seeker-Walker, R.H., et al. (1992) Health, 91, 292–295.

Prevention of cigarette smoking through mass media inter- Palmgreen, P., Donohew, L., Lorch, E.P., et al. (2001b)

ventions and school programs. American Journal of Public Television campaigns and sensation seeking targeting of

Health, 82, 827–835. adolescent marijuana use: a controlled time-series approach.

Flynn, B.S., Worden, J.K., Secker-Walker, R.H., et al. (1994) In Hornik, R.C. (ed.), Public Health Communication:

Mass media and school interventions for cigarette smoking Evidence for Behavior Change. Erlbaum, Mahwah, NJ,

prevention. American Journal of Public Health, 84, pp. 35–56.

Downloaded from http://her.oxfordjournals.org/ by guest on May 9, 2015

1148–1150. Pechmann, C., Zhao, G., Goldberg, M., et al. (2003) What to

Goldberg, M.E., Fishbein, M. and Middlestadt, S.E. (1997) convey in antismoking advertisements for adolescents: the use

Social Marketing: Theoretical and Practical Perspectives. of protection motivation theory to identify effective message

Erlbaum, Mahwah, NJ, pp. 291–312. themes. Journal of Marketing, 67(2), 1–18.

Grant, B. and Dawson, D. (1997) Age of onset of alcohol use Perry, C.L., Williams, C.L., Komro, K.A., et al. (2002) Project

and its association with DSM-TV alcohol abuse and depend- Northland: long-term outcomes of community action to

ence: results from the National Longitudinal Alcohol Epidemi- reduce adolescent alcohol use. Health Education Research,

ologic Survey. Journal of Substance Abuse, 9, 103–110. 17, 117–132.

Griffin, K.W., Botvin, G.J., Nichols, T.R., et al. (2003) Raudenbush, S.W. and Bryk, A.S. (2002) Hierarchical Linear

Effectiveness of a universal drug abuse prevention ap- Models: Applications and Data Analysis Methods, 2nd edn.

proach for youth at high risk for substance use initiation. Sage, Thousand Oaks, CA.

Preventative Medicine, 36, 1–7. Resnicow, K. and Botvin, G. (1993) School-based substance use

Hansen, W.B. (1996) Pilot test results comparing the All Stars prevention programs—why do effects decay? Preventative

program with seventh grade D.A.R.E.: program integrity and Medicine, 22, 484–490.

mediating variable analysis. Substance Use and Misuse, 31, Ringold, D.J. (2002) Boomerang effects in response to public

1359–1377. health inventions: Some unintended consequences in the

Harrington, N.G., Lane, D.R., Donohew, L., et al. (2003) alcoholic beverage market. Journal of Consumer Policy, 25,

Persuasive strategies for effective anti-drug messages. 27–63.

Communication Monographs, 70(1), 16–38. Rotnitzky, A. and Jewell, N.P. (1990) Hypothesis testing of

Hastie, T.J. and Pregibon, D. (1993) Generalized linear models. regression parameters in semiparametric generalized linear

In Chambers, J.M. and Hastie, T.J. (eds), Statistical Models. models for cluster correlated data. Biometrika, 77, 485–497.

Chapman & Hall, London, pp. 195–248. Rubin, D.B. (1987) Multiple Imputation for Nonresponse in

Hornik, R.C. (2002) Exposure theory and evidence about all the Surveys. Wiley, New York.

ways it matters. Social Marketing Quarterly, 8(3), 30–37. Schafer, J.L. (1999) Multiple imputation: a primer. Statistical

Johnston, L.D., O’Malley, P.M. and Bachman, J.G. (2002) The Methods in Medical Research, 8, 3–15.

Monitoring the Future National Survey Results on Adolescent Slater, M.D. and Kelly, K.J. (2002) Testing alternative explan-

Drug Use: Overview of Key Findings, 2001. National Institute ations for exposure effects in media campaigns: the case of

of Drug Abuse, Bethesda, MD. a community-based, in-school media drug prevention project.

Kotler, P. and Zaltman, G. (1971) Social marketing: an approach Communication Research, 29, 367–389.

to planned social change. Journal of Marketing, 35, 3–12. Slater, M.D., Edwards, R.W., Plested, B.A., et al. (2005) Using

Lee, Y. and Nelder, J.A. (1996) Hierarchical generalized linear community readiness key informant assessments in a random-

models. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society B, 58, ized group trial: impact of a participatory community media

619–678. intervention. Journal of Community Health, 30, 39–53.

McCullagh, P. and Nelder, J.A. (1989) Generalized Linear Thurman, P.J., Edwards, R.W., Plested, B.A., et al. (2003)

Models, 2nd edn. Chapman & Hall, Boca Raton, LA. Honoring the differences: using community readiness to create

McCulloch, C.E. and Searle, S.R. (2001) Generalized, Linear culturally valid community interventions. In Bernal, G.,

and Mixed Models. Wiley, New York. Trimble, J., Burlew, K. and Leong, F. (eds), Handbook of

Merzel, C. and D’Afflitti, J. (2003) Reconsidering community- Racial and Ethnic Minority Psychology. Sage, Thousand

based health promotion: Promise, performance and potential. Oaks, CA, pp. 591–607.

American Journal of Public Health, 93, 557–574. Tobler, N.S. and Stratton, H.H. (1997) Effectiveness of school-

Murray, D.M., Hannan, P.J., Wolfinger, R.D., et al. (1998) based drug prevention programs: a meta-analysis of the

Analysis of data from group-randomized trials with repeat research. Journal of Primary Prevention, 18, 71–128.

observations on the same groups. Statistics in Medicine, 19, Unger, J.G., Gallaher, P., Palmer, P.H., et al. (2004) No news is

1581–1600. bad news: characteristics of adolescents who provide neither

166Combining in-school and community-based media efforts

parental consent nor refusal for participation in school-based Williams, G.C., Cox, E.M., Kouides, R., et al. (1999) Present-

survey research. Evaluation Reviews, 28, 52–63. ing the facts about smoking to adolescents—effects of an

Verbeke, G. and Molenberghs, G. (2000) Linear Mixed Models autonomy-supportive style. Archives of Pediatrics, 153,

for Longitudinal Data. Springer, New York. 959–964.

Wallace, D. and Green, S.B. (2002) Analysis of repeated Worden, J.K. (1999) Research in using mass media to

measures designs with linear mixed models. In Hershberger, prevent smoking. Nicotine and Tobacco Research, 1,

S.L. (ed.), Modeling Intraindividual Variability with Repeated S117–S121.

Measures Data: Methods and Applications. Erlbaum,

Mahwah, NJ, pp. 103–134. Received on May 23, 2005; accepted on August 15, 2005

Downloaded from http://her.oxfordjournals.org/ by guest on May 9, 2015

167You can also read