Can an Ape Create a Sentence?

←

→

Page content transcription

If your browser does not render page correctly, please read the page content below

23 November 1979, Volume 206, Number 4421 SCIENCE

quences produced and understood by

their pongid subjects were governed by

grammatical rules. The Gardners, for ex-

ample, note that "The most significant

results of Project Washoe were those

Can an Ape Create a Sentence? based on comparisons between Washoe

and children, as . . . in the use of order

H. S. Terrace, L. A. Petitto, R. J. Sanders, T. G. Bever in early sentences" (3, p. 73).

If an ape can truly create a sentence

there would be a reason for asserting, as

Patterson (11) has, that "language is no

longer the exclusive domain of man."

The innovative studies of the Gardners song when asserting territory. Such ri- The purpose of this article is to evaluate

(1-3) and Premack (4-6) show that a gidity is typical of the communicative be- that assertion. We do so by summarizing

chimpanzee (Pan troglodytes) can learn havior of other genera, for example, bees the main features of a large body of data

substantial vocabularies of "words" of communicating about the location and that we have collected from a chim-

visual languages. The Gardners taught quality of food or sticklebacks engaging panzee exposed to sign language during

Washoe, an infant female chimpanzee, in courtship behavior (14). its first 4 years. A major component of

signs of American Sign Language (ASL) Human language is most distinctive these data is the first corpus of the multi-

(7, 8). Premack taught Sarah, a juvenile because of a second level of structure sign utterances of an ape. Superficially,

female, an artificial language of plastic that subsumes the word-the sentence many of its utterances seem like sen-

tences. However, objective analyses of

our data, as well as of those obtained by

Summary. More than 19,000 multisign utterances of an infant chimpanzee (Nim) other studies, yielded no evidence o

........... ....

an

were analyzed for syntactic and semantic regularities. Lexical regularities were ob- ape's ability to use a grammar. Each in-

served in the case of two-sign combinations: particular signs (for example, more) stance of presumed grammatical compe-

tended to occur in a particular position. These regularities could not be attributed to tence could be explained adequately by

memorization or to position habits, suggesting that they were structurally constrained. simple nonlinguistic processes.

That conclusion, however, was invalidated by videotape analyses, which showed that

most of Nim's utterances were prompted by his teacher's prior utterance, and that

Nim interrupted his teachers to a much larger extent than a child interrupts an adult's Project Nim

speech. Signed utterances of other apes (as shown on films) revealed similar non-

human patterns of discourse. Our subject was a male chimpanzee,

Neam Chimpsky (Nim for short) (16, 17).

Since the age of 2 weeks, Nim was raised

chips of different colors and shapes. In a (15). A sentence characteristically ex- in a home environment by human surro-

related study, Rumbaugh et al. (9) taught presses a complete semantic proposition gate parents and teachers who communi-

Lana, also a juvenile chimpanzee, to use through a set of words and phrases, each cated with him and amongst themselves

Yerkish, an artificial visual language. bearing particular grammatical relations in ASL (7,8). Nim was trained to sign by

These and other studies (10), one of to one another (such as actor, action, ob- a method modeled after the techniques

which reports the acquisition of more ject). Unlike words, most sentences can- that the Gardners (2) and Fouts (18) have

than 400 signs of ASL by a female gorilla not be learned individually. Psycholo- referred to as molding and guidance. Our

named Koko (11), show that the shift gists, psycholinguists, and linguists are methods of data collection paralleled

from a vocal to a visual medium can in general agreement that using a human those used in studies of the development

compensate effectively for an ape's in- language indicates knowledge of a gram- of language in children (19-24). During

ability to articulate many sounds (12). mar. How else can one account for a their sessions with Nim, his teachers

That limitation alone might account for child's ultimate ability to create an 'in- whispered into a miniature cassette re-

earlier failures to teach chimpanzees to determinate number of meaningful sen- corder what he signed and whether his

communicate with spoken words (13). tences from a finite number of words?

Human language makes use of two Recent demonstrations that chim-

levels of structure: the word and the sen- panzees and gorillas can communicate H. S. Terrace is a professor of psychology at Co-

lumbia University, 418 Schermerhorn Hall, Colum-

tence. The meaning of a word is arbi- with humans via arbitrary "words" pose bia University, New York 10027. L. A. Petitto is a

a controversial question: Is the ability to graduate student in the Department of Human De-

trary. This is in contrast to the fixed velopment at Harvard University, Cambridge, Mas-

character of various forms of animal create and understand sentences unique- sachusetts 01238. R. J. Sanders is a graduate student

in the Department of Psychology at Columbia Uni-

communication. Many bird species, for ly human? The Gardners (1, 3), Premack versity and a visiting instructor at the State Univer-

example, sing one song when in distress, (6), Rumbaugh (9), and Patterson (11) sity of New York in Utica. T. G. Bever is a professor

of psychology and linguistics at Columbia Universi-

one song when courting a mate, and one have each proposed that the symbol se- ty.

SCIENCE, VOL. 206, 23 NOVEMBER 1979 0036-8075/79/1123-0891$02.00/0 Copyright C 1979 AAAS 899signs were spontaneous, prompted, Table 1. Number of tokens and types of com- turn of the hands to a relaxed position

molded, or approximations of the correct binations containing two, three, four, and five (29). Of Nim's combinations, 95 percent

sign (25). or more signs. consisted of sequences of distinct signs

Nim satisfied our criterion of acquiring Length of Tokens Types that occurred successively. These are re-

a sign when (i) on different occasions, combination ferred to as "liiear sequences." Two

three independent observers reported its Two signs 11,845 1,138 other kinds of combinations were not in-

spontaneous occurrence and (ii) it oc- Three signs 4,294 1,660 cluded in the corpus: contractions of two

curred spontaneously on each of five Four signs 1,587 1,159 or more signs and simultaneous combi-

successive days. By spontaneously we Five or more signs 1,487 1,278 nations in which two distinct signs oc-

mean that Nim signed the sign in an ap- curred at the same time. Even though

propriate context and without the aid of such combinations can occur in ASL,

molding, prompting, or modeling on the stances of more tickle, the conventional they were excluded from our corpus be-

part of the teacher. As of 25 September English juxtaposition of these signs. Ac- cause it was impossible to specify the

1977, Nim had acquired 125 signs (26). cordingly, there is no basis for deciding temporal order of the signs they con-

whether Washoe's multisign combina- tained. Figure 1 shows a typical linear

tions obeyed rules of sign order (28). One combination, me hug cat, in which there

Combinations of Signs could conclude that Washoe had learned is no temporal overlap between any of

that both more and tickle were appropri- the signs.

The Gardners' analyses of Washoe's ate ways of requesting that tickling reoc- In no instance were specific se-

sign combinations prevents one from cur and that when Washoe signed both quences, contractions, or simultaneous

studying their grammatical structure. signs it was because of her prior training combinations reihforced differentially.

With but two minor exceptions, the to sign each sign separately. Indeed, Nim was never required to make

Gardners did not report the order of We defined a combination of signs as a combination of signs as opposed to a

signs of Washoe's multisign combina- the occurrence of two or more different single sign. However, Nim's teachers of-

tions (27). For example, more tickle and signs that were not interrupted by the oc- ten signed to him in stereotyped orders

tickle more were both reported as in- currence of other behavior or by the re- modeled after English usage, and they

I

Fig. 1. Nim signing the linear combination, me hug cat to his teacher (Susan Quinby). (Photographed in classroom by H. S. Terrace.)

892 SCIENCE, VOL. 206may also have unwittingly given him spe- consisting of all transitive verbs com- we observed. A conservative inter-

cial praise when he signed an interesting bined with all references to himself (me pretation of these regularities, one that

combination. Such unintentional reac- or Nim), is shown in Table 3 (32). The does not require the postulation of syn-

tions do not, however, appear to differ number of tokens with the verb in the tactic rules, would hold that Nim used

from the reactions parents exhibit when first position substantially exceeds the certain categories as relatively initial or

their child produces an interesting utter- reverse order. Also, Nim combined tran- final irrespective of the context in which

ance or one that conforms to correct sitive verbs as readily with Nim as with they occur. If this were true, it should be

English. me (33). Nim's preference for using me possible to predict the observed frequen-

Nim's linear combinations were sub- and Nim in the second position of two- cy of different constructions, such as

jected to three analyses. First, we looked sign combinations was also evident in verb + me or verb + Nim, from the rel-

for distributional regularities in Nim's requests for various ingestible and non- ative frequency of their constituents in

two-sign utterances: did Nim place par- ingestible objects (Table 2). the initial and final positions.

ticular signs in the first or the second po- Different frequency patterns, such as The accuracy of such predictions was

sition of two-sign combinations? Sec- those shown in Tables 2 and 3, are not tested by allocating each sign of a two-

ond, having established that lexical sufficient to demonstrate that Nim's se- sign sequence to a lexical category and

regularities did exist in two-sign com- quences are constrained structurally. then using the relative frequencies of

binations, we looked for semantic re- Nim could have a set of independent these lexical categories to predict the

lationships in a smaller corpus of two- first- and second-position habits that probabilities of each two-sign lexical

sign combinations for which we had ade- generated the distributional regularities type. The predicted value of the proba-

quate contextual information. The re-

sults of these analyses were equivocal. A

third, "discourse," analysis of videotape Table 2. Frequency of particular signs in first and second positions of two-sign combinations.

transcripts shows that Nim's signs were Combination Types Tokens

often prompted by his teacher's prior

signs. + X 47 974

Corpus and distributional regularities. + more 27 124

+ X 51 271

From Nim's 18th to 35th month his + give 24 77

teachers entered in their reports 5235 me

types of 19,203 tokens of linear combina- Transitive verb + or 25 788

tions of two to five or more signs. Dif- Nim

ferent sequences of the same signs were + Transitive verb 19 158

regarded as different types (for example,

banana eat or eat banana). The number me

of types and tokens of each length of Noun (food/drink) + or 34 775

combination (Table 1) in each case grew Nim

linearly (30, 31). + noun (food/drink) 26 261

The sheer variety of types of combina-

tions and the fact that Nim was not re- me

quired to combine signs suffices to show Noun (nonfood/drink) + or 35 181

Nim

that Nim's combinations were not v

learned by rote. The occurrence of more + Noun (nonfood/drink) 26 99

than 2700 types of combinations of two- Nim

and three-sign combinations would

strain the capacity of any known esti-

mate of a chimpanzee's memory. As was Table 3. Two-sign combinations containing me or Nim and transitive verbs [V(t)].

mentioned earlier, however, a large vari-

ety of combinations is not sufficient to V(t) + me V(t) + Nim me + V(t) Nim + V(t)

demonstrate that such combinations are Types Tokens Types Tokens Types Tokens Types Tokens

sentences; that is, that they express a se-

mantic proposition in a rule-governed se-,- bite me 3 bite Nim 2 me bite 2

break me 2

quence of signs. In the absence of addi- brush me 35 brush Nim 13 me brush 9 Nim brush 4

tional evidence, the simplest explanation clean me 2 clean Nim 1 me clean 2

of Nim's utterances is that they are un- me cook I

structured combinations of signs, in draw Nim I

which each sign is separately appropriate finish me I finish Nim 7 Nim finish I

give me 41 give Nim 23 me give 11 Nim give 4

to the situation at hand. Nim go 4

The regularity of Nim's combinations groom me 21 groom Nim 6 Nim groom 1

suggest that they were generated by help me 6 help Nim 4 me help 2

rules and was most pronounced in the hug me 74 hug Nim 106 me hug 40 Nim hug 23

kiss me 1 kiss Nim 6 me kiss 1 Nim kiss 2

case of two-sign combinations. As open me 13 open Nim 6 me open 10 Nim open 5

shown in Table 2, more + X is more fre- pull Nim 1

quent than X + more, give + X is more tickle me 316 tickle Nim 107 me tickle 20 Nim tickle 16

frequent than X + give, and verb + me 515 283 98 60

or Nim is more frequent than me or

Nim + verb. An example of the regular- Total types: 25 Total types: 19

Total tokens: 788 Total tokens: 158

ities in Nim's two-sign combinations,

23 NOVEMBER 1979 893Table 4. Twenty-five most frequent two- and three-sign combinations. frequent two-sign combinations (gum,

Two-sign Fre- Three-sign Fre-

tea, sorry, in, and pants) appear in his 25

combinations quency combinations quency most frequent three-sign combinations.

We did not have enough contextual in-

play me 375 play me Nim 81 formation to perform a semantic analysis

me Nim 328 eat me Nim 48 of Nim's two- and three-sign combina-

tickle me 316 eat Nim eat 46

eat Nim 302 tickle me Nim 44 tions. However, Nim's teachers' reports

more eat 287 grape eat Nim 37 indicate that the individual signs of his

me eat 237 banana Nim eat 33 combinations were appropriate to their

Nim eat 209 Nim me eat 27 context and that equivalent two- and

finish hug 187 banana eat Nim 26 three-sign combinations occurred in the

drink Nim 143 eat me eat 22

more tickle 136 me Nim eat 21 same context.

sorry hug 123 hug me Nim 20 Though lexically similar to two-sign

tickle Nim 107 yogurt Nim eat 20 combinations, the three-sign combina-

hug Nim 106 me more eat 19 tions (Table 4) do not appear to be in-

more drink 99 more eat Nim 19

eat drink 98 finish hug Nim 18 formative elaborations of two-sign com-

banana me 97 banana me eat 17 binations. Consider, for example, Nim's

Nim me 89 Nim eat Nim 17 most frequent two- and three-sign com-

sweet Nim 85 tickle me tickle 17 binations: play me and play me Nim.

me play 81 apple me eat 15 Combining Nim with play me to produce

gun eat 79 eat Nim me 15

tea drink 77 give me eat 15 the three-sign combination, play me

grape eat 74 nut Nim nut 15 Nim, adds a redtndant proper noun to a

hug me 74 drink me Nim 14 personal pronoun. Repetition is another

banana Nim 73 hug me hug 14 characteristic of Nim's three-sign combi-

in pants 70 sweet Nim sweet 14

nations, for example, eat Nim eat, and

nut Nim nut. In producing a three-sign

combination, it appears as if Nim is add-

bility of a particular sequence was calcu- as units when they are used to expand ing to what he might sign in a two-sign

lated by multiplying the probabilities of what was expressed previously by a combination, not so much to add new in-

the relevant lexical types appearing in single word. formation but instead to add emphasis.

the first and second positions, respec- The apparent topic of Nim's three-sign Nim's most frequent four-sign combina-

tively. In predicting the probability of me combinations overlapped considerably tions (Table 5) reveal a similar picture. In

eat, for example, the probability of me in with the apparent topic of his two-sign children's utterances, in contrast, the

the first position (.121) was multiplied by combinations (Table 4). Eighteen of repetition of a word, or a sequence of

the probability of eat in the second posi- Nim's 25 most frequent two-sign combi- words, is a rare event (34).

tion (.149), yielding a predicted relative nations can be seen in his 25 most fre-

frequency of .016. quent three-sign combinations, in virtu-

The correlation between 124 pairs of ally the same order in which they appear Differences Between Nim's and a

predicted and observed probabilities was in his two-sign combinations. Further- Child's Utterances

.0036. It seems reasonable to conclude more, if one ignores sign order, all but

that, overall, Nini>s two-sign sequences five signs that appear in Nim's 25 most The fact that Nim's long utterances

are not form ent vosition were not semantic or syntactic elabora-

habits. Furthermore, it is not possible to tions of his short utterances defines a

predict the observed relative position major difference between Nim's initial

frequencies of lexical types of three-sign Table 5. Most frequent four-sign combina- multiword utterances and those of a

tions.

combinations from the relative frequen- / child. These and other differences in-

cies of their constituents. The correla- Four-sign combinations Fre- dicate that Nim's general use of combi-

tion between the 66 pairs of predicted quency nations bears only a superficial similarity

and observed probabilities was only .05. eat drink eat drink 15 to a child's early utterances (35-38).

Relation between Nim's two-, three- eat Nim eat Nim 7 The mean length of Nim's utterances.

and four-sign combinations. As children banana Nim banana Nim 5 As the mean length of a child's utter-

increase the length of their utterances, drink Nim drink Nim 5

banana eat me Nim 4 ances (MLU) increases, their complexity

they elaborate their initially short utter- banana me eat banana 4 also progressively increases (20-22). In

ances to provide additional information banana me Nim me 4 English, for example, subject-verb and

about some topic (20, 22). For example, grape eat Nim eat 4 verb-object construction merge into sub-

instead of saying, sit chair, the child Nim eat Nim eat 4 ject-verb-object constructions.

play me Nim play 4

might say, sit daddy chair. In general, it drink eat drink eat 3 Figure 2 shows Nim's MLU (the mean

is possible to characterize long utter- drink eat me Nim 3 number of signs in each utterance) be-

ances as a composite of shorter constitu- eat grape eat Nim 3 tween the ages of 26 and 45 months (39).

ents that were mastered separately. eat me Nim drink 3 The most striking aspect of these func-

Longer utterances are not, however, grape eat me Nim 3

me eat drink more 3 tions is the lack of growth of Nim's MLU

simple combinations of short utterances. me eat me eat 3 during a 19-month period. Figure 2 also

In making longer utterances, the child me gum me gum 3 shows comparable MLU functions ob-

combines words in short utterances in me Nim eat me 3 tained from hearing (speaking) and deaf

justone order; he deletes repeated ele- Nim me Nim me 3 (signing) children (40), including the

tickle me Nim play 3

ments, and he treats shorter utterances smallest normal growth of MLU of a

894 SCIENCE, VOL. 206speaking child that we could locate. All such judgments, introduced by Bloom word utterances of children (78 and 95

children start at an MLU similar to (19, 20) and Schlesinger (42), are known percent, respectively). No data are avail-

Nim's at 26 months, but, unlike Nim, the as the method of "rich interpretation"

(21-23, 42). An observer relates the utter-

,Jable as to the reliability of the inter-

pretations that the Gardners and Patter-

children all show increases in MLU.

Another difference between Nim's and ance's immediate context to its contents. son have advanced.

childrens' MLU has to do with the value Supporting evidence for semantic judg- A widely cited example of Washoe's

of the MLU and its upper bound. Ac- ments includes the following observa- ability to create new meanings through

cording to Brown, ". . . the upper bound tions. The child's choice of word order is novel combinations of her signs is her ut-

of the (MLU) distribution is very reliably usually the same as it would be if the idea terance, water bird. Fouts (45) reported

related to the mean.... At MLU = 2.0 were being expressed in the canonical that Washoe signed water bird in the

the upper bound will be, most liberally, ( adult form. As the child's MLU increas- presence of a swan when she was asked

5 ± 2" (41). Nevertheless, with an MLU es, semantic relationships identified by a what that? Washoe's answer seems

of 1.6 Nim made utterances containing rich interpretation develop in an orderly meaningful and creative in that it juxta-

as many as 16 signs (give orange me give fashion (20, 22, 43). The relationships ex- poses two appropriate signs in a manner

eat orange me eat orange give me eat or- pressed in two-word combinations are consistent with English word order.

ange give me you). In our discourse anal- the first ones to appear in the three- and Nevertheless, there is no basis for con-

yses of Nim's and Washoe's signing (see four-word combinations. Many longer cluding that Washoe was characterizing

below), we suggest mechanisms that can utterances appear to be composites of the swan as a "bird that inhabits water."

lengthen an ape's utterance but that do the semantic relationships expressed in Washoe had a long history of being

not presuppose an increase in se antic shorter utterances (20, 22). asked what that? in the presence of ob-

or syntactic competence. \/) Studies of an ape's ability to express jects such as birds and bodies of water.

Semantic-reraie s hips expressed in semantic relationships in combinations In this instance, Washoe may have sim-

Nim's two-sign combinations. Semantic 'of signs have yet to advance beyond the ply been answering the question, what

distributions, unlike the lexical ones we stage of unvalidated interpretation. The that?, by identifying correctly a body of

discussed above, cannot be constructed Gardners (44) and Patterson (11) con- water and a bird, in that order. Before

directly from a corpus. In order to derive cluded that a substantial portion of concluding that Washoe was relating the

a semantic distribution, observers have Washoe's and Koko's two-sign combina- sign water to the sign bird, one must

to make judgments as to what each com- tions were interpretable in categories know whether she regularly placed an

bination means. Procedures for making similar to those used to describe two- adjective (water) before, or after, a noun

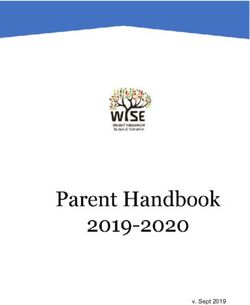

Children: Nim: 0.14

Hearing Deaf 0

A Eve o--o Ruth *-* Classroom sessions

* 'Sarah *--- Pola x---x Home sessions I 0.10

4.4 D--O Videotape samples

I

4 I 0.06

4.0

I

I th

0.02

n 11 n

3.6 - I

I

0

3.2 Q 0,oDC

ID) UoC< Q+ 0+ o'0 to

Q D

Q

c ...---- sL

c c w La.0

0

2.8H /

c

2.4

.1

4

/.

.. ,

~~~//

z ~//

v. 0.18_

Semantic relationship

,0.14

2.0 F

A~

/ n 0.10 F

1.6& .x / O P

0.06 F

1.2

E E ss t o~~~~~~

l~ ~ -6 \ It El l

I 0I I I I 40 4 41 5 0.02

20 24 28 32 36 40 44 48 52 ,=6- r" Cl=

Age (months) .; _

Fig. 2 (left). Mean length of signed utterances of Nim and three deaf children and *V @ z ;

mean length of spoken utterances of two hearing children. The functions showing T O C0

E

Nim's MLU between January 1976 and February 1977 (age, 26 to 39 months) are f0 r

3.1~0

based on data obtained from teachers' reports; the function showing Nim's MLU + '- C

>

+ +

between February 1976 and August 1977 (age, 27 to 45 months) is based upon : +

videotranscript data. [See (39) regarding the calculation of MLU's for signed ut-

terances.] Fig. 3 (right). Relative frequencies of different semantic relation-

ships. The bars above I and II show to the relative frequencies of two-sign combi- Semantic relationship

nations expressing the relationship in the order specified under the bar, for example, an agent followed by an action. The bars above I show

the relative frequencies of two-sign combinations expressing the same relationship in the reverse order, for example, action followed by an agent.

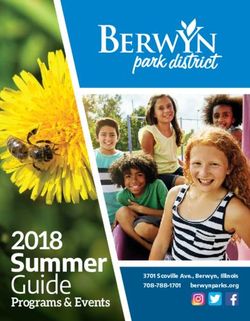

23 NOVEMBER 1979 8951.U - _ Children Nim our semantic analyses of an ape's two- Table 6. Discourse between Washoe (W) and

Bloom, Rocissano B. Gardner (B.G.). See Fig. 5. This is a tran-

& Hood (1976) 00'O" sign combinations nor those of any oth-

0.8 Adjacent responses-- er studies have produced such evidence.

script of a tape shown on television.

--

3

CL 0.6 - o\

j

/ 1' 8' , In some cases, utterances were inher-

' ,, 'ently equivocal in our records. Accord-

Xozo .

Time Frame

00.00 7 B.G:Iwhat

2

0.6

*

ingly, somewhat arbitrary rules were 1.46 8 time

/i used to interpret these utterances. Con- 1.96 9 W: Itime

0.4 ~

* . sider, for example, combinations of Nim 2.25 10 now?! eatl

e 0.4 /t/ r. 1 and me with an object name (for ex- 4.50 11 Itimel

/ Expansions 4.84 12 eat!

ample, Nim banana). These occurred --------- splice ---------

A

0.2 when the teacher held up an object that

Imitations the teacher was about to give to Nim

who, in turn, would ingest it. We had no

0.o 2, 21?6 , 36 26* ---,-'.*. 6 clear! basis for distinguishing between the There has been increasing interest in

31 36 41 following semantic interpretations of the way parents speak to their children

Age (months) combinations containing Nim or me and

Fig. 4. Proportion of utterances emitted by aobject name: ngeNt-obje bn- (50) and in the ways children adjust their

children (left-hand function) and by Njm an object name: agent-object, ben- speech to aspects of the prior verbal con-

(right-hand functions) that are adjacent to, im- eficiary-object, and possessor-possessed text (51). Fillmore (52) has likened adult

itative of, or expansions of an adult's prior ut- object. conversations to a game in which two

terance. An equally serious problem is posed participants take turns moving a topic

by the very small number of lexical items along. Children learn quite early that

used to express particular semantic conversation is such a turn-taking game

(bird). That cannot be decided on the roles. Only when a semantic role is rep- (53). However, our discourse analysis

basis of a single anecdote, no matter how resented by a large variety of signs is it revealed a fundamentally different rela-

compelling that anecdote may seem to an reasonable to attribute position prefer- tionship between Nim's and his teach-

English-speaking observer. ences to semantic rules rather than to er's utterances.

Without prejudging whether Nim ac- lexical position habits. For example, the fhe corpus we analyzed was derived

tually expressed semantic relationships role of recurrence was presented exclu- from transcripts of 31/2 hours of video-

in his combinations, we analyzed, by the sively by more. In combinations pre- tapes from nine sessions recorded be-

method of rich interpretation, 1262 of his sumed to relate an agent and an object or tween the ages of 26 to 44 months (54). A

two-sign combinations, which occurred an object and a beneficiary, one would comparison of Nim's discourse with his

between the ages of 25 to 31 months (46). expect agents and beneficiaries to be ex- teachers and children's discourse with

The results of our semantic analysis are pressed by a broad range of agents and adults, characterized by Bloom et al.

shown in Fig. 3. Twenty categories of se- beneficiaries, for example: Nim, me, (51), is shown in Fig. 4. Adjacent utter-

mantic relationships account for 895 (85 you, and names of other animate'beings. ances are those that follow an adult ut-

percent) of the 957 interpretable two-sign However, 99 percent (N = 297) of the terance without a definitive pause (51).

combinations. Brown (47) found that beneficiaries in utterances judged to be At 21 months (MLU - 1.3), the mnost ap-

there were 11 semantic relationships that object-beneficiary combinations were propriate stage of development with

account for about 75 percent of all com- Nim and me, and 76 percent (N = 35) of which to compare Nim, the average pro-

binations of the children he studied. Sim- the agents in'utterances judged to be portion of a child's utterances that are

ilar categories of semantic relationships agent-object combinations were you. adjacent is 69.2 percent (range, 53 to 78

were used by the G'ardners and by Pat- From these and other examples, it is dif- percent). A somewhat higher percentage

terson (48). ficult to decide whether the positional (87 percent) of Nim's utterances were

Figure 3 shows several instances of regularities favoring agent-object and ob- classified as adjacent (range: 58.7 to 90.9

significant preferences for placing signs ject-beneficiary constructions (Fig. 3) percent).

expressing a particular semantic role in are expressions of semantic relationships Adjacent utterances can be classified

either the first or the second positions. or idiosyncratic lexical position habits. in four categories. (i) Imitations are

Agent, attribute, and recurrence (more) Such isolated effects could also be ex- those utterances that contain all of the

were expressed most frequently in the pected to appear from statistically ran- lexical items of the adult's utterances,

first position, while place and beneficiary dom variation. and nothing else; (ii) reductions are those

roles were expressed most frequently by Discourse analysis. An analysis of that contain some of the lexical items of

second-position signs (49). video transcripts revealed yet another the adult's utterance and nothing else;

At first glance, the results of our se- contribution to the semantic look of (iii) expansions are those that contain

mantic analysis appear to be consistent Nim's combinations; his utterances were some of the lexical items of the adult's

with the observations of the Gardners often initiated by his teacher's signing utterance along with some new lexical

and Patterson. But even though our judg- and they were often full or partial imita- items; and (iv) novel utterances are those

mnents were reliable, several features of tions of his teachers' preceding utter- that contain none of the lexical items of

our results suggest that our analysis, and ance. Since full or partial imitations were the aduft's utterance. Among the chil-

that of others, may exaggerate Nim's se- included in the corpus, it is possible that dren studied by Bloom et al. (51), imita-

mantic competence. One problem is the the semantic relationships and position tions and reductions accounted for 18

subjective nature of semantic inter- preferences we observed are, to some percent (Fig. 4) of all of the children's ut-

pretations. That problem can be reme- extent, reflections of teachers' signing terances at stage 1 (MLU = 1.36). That

died only to the extent that evidence cor- habits. Those that were imitated cannot 18 percent decreas,ed with increasing

roborating the psychological reality of be regarded as comparable to a child's MLU, accounting for only 2 percent of

our interpretations is available. Neither nonimitative constructions. the children's utterances at stage 5

896 SCIENCE, VOL. 206(MLU = 3.91). In contrast, 39.1 percent Table 7. Discourse between\Washoe (W) and amples of the influence of the teacher's

of Nim's adjacent utterances (N = 509) B. Gardner (B.G.). signing on Nim's signing were noted ift

were imitations or reductions (range, Time Frame photographs such as those shown in Fig.

19.5 to 57.1 percent). (sec- (see 1 (a series of still photographs taken with

At stage 1, 21.2 percent of a child's ut- ond) Fig. 5) a motor-driven camera). Examination of

terances are expansions of the adult's 00.00 1 B.G: leat Fig. 1, prompted by the results of our

prior utterance (range, 10 to 28 percent). 00.42 2 mel discourse analysis, reveals that Nim's

On the average, only 7.3 percent of 02.38 3 Imore teacher signed you while Nim was sign-

Nim's utterances were expansions of his 02.80 4 me(mine)l ing me, then later signed who? while Nim

03.34 5 (W feeds B.G)

teacher's prior utterance (range, I to 15 07.09 6 /thank you/ was signing cat. Because these were the

percent). As the child gets older, the pro- 10.92 7 /what only four photographs taken of this dis-

portion of its utterances that are expan- 12.38 8 time course, we cannot specify just when the

sions increases. Bloom et al. (51) noted 12.88 9 W: /time teacher began her signs. It is not clear,

13.17 10 now?l eatl for example, whether the teacher signed

that many of the child's utterances are 15.42 11 Itime

systematic expansions of verb relations 15.76 12 eatl you simultaneously or immediately prior

contained in the adult's prior utterance. ---------splice--------- to Nim's me. However, it is unlikely that

No such pattern was discernible in 00.00 13 B.G: /what the teacher signed who? after Nim signed

Nim's expansions. Indeed a preliminary',/ 00.46 14 now?l cat.

analysis of Nim's expansions indicates 00.29 15 /what W: lin

that aside from the teacher's signs, his 04.79 16 now in,

05.33 17 Ime

utterances contain only a small number 05.67 18 eat Comparison of Nim's Discourse with

of additional signs, such as me, Nim, 06.17 19 time That of Other Signing Apes

you, hug, and eat. Since these signs are 06.38 20 4 ?l eatl

not specific to particular contexts, they Two valuable sources of information

do not add new information to the teach- that suggest that Nim's discourse with

er's utterance. teacher's signing or the degree to which his teachers was not specific to the con-

By definition, adjacent utterances may Nim imitated or interrupted his teachers. ditions of our project are a film produced

include interruptions of a teacher's or an That information can be obtained only by Nova for television, entitled, The

adult's utterance. Such interruptions de- from ifim or videota nspts. The First Signs of Washoe (57), and a film,

tract from true conversation since they contrast between the conclusions that produced by the Gardners, Teaching

result in discourse that is simultaneous might be drawn from our distributional Sign Language to the Chimpanzee:

rather than successive. In 71 percent of analyses and those that follow from our Washoe (58).

the utterances that have been examined discourse analysis provides an important Consider the scene from First Signs of

(425 out of 585), Nim signed simulta- methodological lesson. In the absence of Washoe shown in Table 6 and in the left-

neously with his teacher. Of these over- a permanent record of an ape's signing, hand portion of Fig. 5 (59). In this con-

lapping utterances, 70 percent occurred and the context in which that signing oc- versation, Washoe's utterances either

when Nim began an utterance while the curred, even an objectively assembled followed or interrupted B. Gardner's ut-

teacher was signing. When the teacher corpus of an ape's utterances does not terance. It is also the case that the sign

interrupted one of Nim's utterances, it provide a sufficient basis for drawing time was uttered by B. Gardner just prior

was generally the case that Nim had just conclusions about the grammatical regu- to Washoe's utterance time eat (60).

interrupted the teacher and the teacher larities of those utterances. Teaching Sign Language to the Chim-

was, in effect, asserting his or her right to Unanticipated, but instructive, ex- panzee: Washoe presents a longer ver-

hold the floor. Nim's interruptions show

no evidence that they are in response to

the teacher's attempts to take the floor Table 8. Discourse between Washoe (W) and S. Nichols (S.N.).

from him. Few data are available con-

cerning the relative frequency or dura- Frame

tion of simultaneous utterances that oc- (see

Fig. 6)

cur in dialogues between children and

adults in either spoken or sign language. 1 S.N: Ithatl (points to cup)

In the most relevant study we could lo- 2 W:/babyl

(brings cup and doll closer

cate, McIntyre reports that her video- to W; S.N. allows W to touch

tape transcripts of a 13-month deaf child it; S.N. slowly pulls it

signing with her mother revealed virtual- away)

ly no interruptions of the mother's utter- 3 S.N: Ithatl (points to cup)

W:/in/

ances (54a). Bloom (55) and Bellugi (56) (looks away from

have observed that interruptions are vir- S.N.)

tually nonexistent in their videotapes of S.N: (brings the cup

children learning vocal and sign lan- and doll closer to W)

W: (looks back at cup

guages (56a). and doll)

None of Nim's teachers, nor the many 4 W: Ibabyl

expert observers who were fluent in sign S.N: (brings cup closer to W)

language, were aware of either the extent " 5 W: linl

to which the initiation and contents of 6 S.N.: Ithatl (points to cup) W: /my

7 drinkl

Nim's signing were dependent on the

23 NOVEMBER 1979 897sion of the same conversation. As can be Table 9. Discourse between Washoe (W) and without intervening prompting on the

seen in Table 7 and Fig. 5 both of Wash- S. Nichols (S.N.). part of the teacher. The sign glossed in

oe's signs (time) and (eat) were signed by Time film as my is confiiurationally identical

B. Gardner immediately prior to Wash- (sec- Discourse to the sign me shown in Fig. 5, frame 17.

oe's having signed them. Time eat can- onds) Both signs conform to the specification

not be considered a spontaneous utter- 00.00 S.N:/ who stupid?l of my in the Gardners' description of

ance for two reasons. It was a response 00.42 W:/ Susan, Susanl Washoe's sign (1, p. 264). For these rea-

to a request to sign by B. Gardner and it 05.30 S.N:/ who stupid?l sons alone, Washoe's actual sequence of

05.58

contained signs just signed by her. The 06.42 W:/ stupidl signs, baby in baby in my drink, cannot

S.N/: who?l be regarded as a spontaneously gener-

significance of a full record of discourse 06.72 W:I Washoel

between a chimpanzee and its teacher is 07.04 S.N:/ Washoel ated utterance.

also revealed by the segment that follows 07.36 S.N:/ (tickles In the immediately preceding scene of

the splice in the film. Consider Washoe's Washoe)/ the film, Susan was shown drilling Wash-

combination me eat time eat in isolation. oe extensively about a baby in shoe and

Without knowledge of the teacher's prior an apple in hat while Washoe was trying

utterances it would be all too easy to in- 6 and Table 8), a combination of four to grab the desired objects from the

terpret Washoe's utterance as one that signs described in both films as a creative teacher. This suggests that Washoe's

signifies a description of future behavior use of sign language by Washoe. In this sign my, in baby in baby in my drink, was

and a knowledge of time. Our transcrip- (run-on) sequence, the order of Wash- signed to convey to her teacher that she

tion of the discourse between B. Gardner oe's signs reflects the order in which the wanted the doll. Given this type of drill,

and Washoe also shows that three out of teacher (Susan Nichols) signed to Wash- and the teacher's pointing to the objects

Washoe's four utterances interrupted B. oe to sign about a baby doll inserted in a to be named in the appropriate sequence,

Gardner's utterances. cup. The sequence of the teacher's signs it is gratuitous to characterize the utter-

Another instructive example of the in- (pointing to the doll and then pointing to ance shown in Fig. 6 as a creative juxta-

,fluence of the teacher on the production the cup) follows the order called for by position of signs that conveyed the

of Washoe's signs is provided by the ut- an English prepositional phrase. Only meaning "a doll in Washoe's cup."

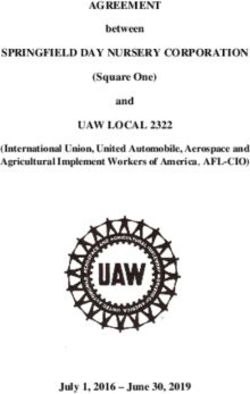

terance glossed as baby in my drink (Fig. the last two signs, my and drink occurred As a final example of Washoe's dis-

now?

I w

B.G.:/what

I

II /what W.: /in

now

in/

D

I

I

I

B.G.:/w hat

W.:/time W.: /me eat

7? )

now/

eat/ /time eat/ time eat/

Fig. 5. Tracings (made from a film) of Washoe signing with B. Gardner. See (S9).

898 SCIENCE, VOL. 206course with her teachers, consider the

conversation about Washoe's intelli-

gence shown in Table 9. This sequence

also appears to be a drill. The important

question it raises, however, is whether

Washoe actually understood the mean-

ings of stupid (and smart). Her usage of S.N.:/that/

stupid was clearly imitative of her teach- W.:/baby/ /in/

er. The exchange between Washoe and

the teacher (Susan Nichols) was also ter-

minated at the point at which the teacher

induced Washoe to make the signs stupid

and Washoe. The circumstances under

which this sequence of signs occurred

raises questions about the Gardners' se-

mantic analysis of combinations such as

Naiomi good (44). That combination was W:/baby in my drink/

presented as an example of attribution, Fig. 6. Tracings of Washoe (made from a film) signing with S. Nichols. See (59).

an interpretation that would be appropri-

ate only in the absence of the kinds of

prompting and reward shown in the films a sentence or whether a particular per- production on the part of Sarah and

of Washoe signing. formance qualifies as an instance of Lana. As a result of rote training, both

The longer of these films, Teaching grammatically guided sentence compre- Sarah and Lana learned to produce spe-

Sign Language to the Chimpanzee: hension. It has been observed widely cific sequences of words, for example,

Washoe, showed 155 of Washoe's utter- that the early sequences of words uttered please machine give apple (9), or Mary

ances of which 120 were single-sign ut- by a child do not necessarily qualify as give chocolate Sarah (6). Subsequently,

terances. These occurred mainly in vo- sentences (19, 24). If, indeed, the only both Sarah and Lana learned to sub-

cabulary testing sessions. Each of Wash- evidence that children could create and stitute certain new words in order to ob-

oe's multisign sequences (24 two-sign, 6 understand sentences were their initial tain other incentives from the same or

three-sign, and 5 four-sign sequences) utterances, and their responses to their from other agents (for example, Randy

were preceded by a similar utterance or a parents' utterances, there would be little give Sarah apple, please machine give

prompt from her teacher. Thus, Wash- reason to conclude that a child's produc- drink, or please machine show slide).

oe's utterances were adjacent and imita- tion and comprehension of words are The last sequence was presented as evi-

tive of her teacher's utterances. The governed by a grammar. dence that Lana learned to use different

Nova film, which also shows Ally (Nim's A rich interpretation of a young child's "verbs" (give and show) in conjunction

full brother) and Koko, reveals a similar early utterances assumes that they are with a different category of incentives,

tendency for the teacher to sign before constrained by structural rules (20, 22). slide, window, and music (9).

the ape signs. Ninety-two percent of Al- It is difficult, however, to exclude sim- Sarah's and Lana's multisign utter-

ly's, and all of Koko's, signs were signed pler accounts of such utterances. A ances are interpretable as rotely learned

by the teacher immediately before Ally child's isolated utterance of a sequence sequences of symbols arranged in partic-

and Koko signed. of words could be a haphazard concate- ular orders; for example, Mary give Sa-

The data provided by a few films are nation of words that bear no structural rah apple, or please machine give apple.

admittedly much more limited in scope relationship to one another (22) or rou- There is virtually no evidence that Lana

than data of the type we obtained from tines that the child learns by rote as imi- and Sarah understood the meaning of all

our nine videotapes. It seems reasonable tations of its parent's speech (24). How- of the "words" in the sequences they

to assume, however, that the segments ever, as children get older, the variety produced. Except for the names of the

shown in the films, the only ones avail- and complexity of their utterances grad- objects they requested, Sarah and Lana

able of apes signing, present the best ex- ually increase (21, 61). Especially telling were unable to substitute other symbols

amples of Washoe's, Ally's, and Koko's is the observation that children pass in each of the remaining positions of the

signing. Even more so than our tran- through phases in which they produce sequences they learned. Accordingly, it

scripts, these films showed a consistent systematically incorrect classes of utter- seems more prudent to regard the se-

tendency for the teacher to initiate sign- ance. During these phases, the child ap- quences of symbols glossed as please,

ing and for the signing of the ape to mirV/ parently "tries out" different sets of machine, Mary, Sarah, and give as se-

ror the immediately prior signing of the rules before arriving at the correct quences of nonsense symbols (63).

teacher. grammar. Children are also able to dis- Consider comparable performance by

criminate grammatically correct from in- pigeons that were trained to peck arrays

correct sentences (62). Accordingly, ex- of four colors in a particular sequence,

Other Evidence Bearing on an planations of their utterances that are not A--B--*C-->D, regardless of the physical

Ape's Grammatical Competence based upon some kind of grammar be- position of the colors (64). In these ex-

come too unwieldy to defend. periments, all colors were presented si-

In evaluating the claim that apes can Production of sequences. Before re- multaneously and there was no step-by-

produce and understand sentences it is garding a sequence of words as sen- step feedback after each response. Evi-

important to keep in mind the lack of a tences, it is necessary to demonstrate the dence that the subjects learned the over-

single decisive test to indicate whether a insufficiency of simpler interpretations. all sequence, and not simply the specific

particular sequence of words qualifies as Consider some examples of sequence responses required by the training arrays

23 NOVEMBER 1979 899was provided by performance that was possible answers, the results of such such, these regularities provide superfi- considerably better than chance on novel

less alternative explanations of an ape's Press, London, 1961); K. von Frish, The Danc- of the disagreements occurred when the teacher

ing Bees (Methuen, London, 1954); N. Tin- failed to record a sign, when, for example, the

combinations of signs areieliminated, in bergen, The Study of Instinct (Clarendon, Ox- teacher was busy preparing an activity, when

particular the habit of partially imitating ford, 1951). Nim was signing too quickly, or when the teach-

15. N. Chomsky, Aspects of the Theory of Syntax er was signing to Nim. There was no evidence

teachers' recent utterances, there is no (MIT Press, Cambridge, Mass., 1965); Syntactic that the omissions of the teacher were system-

reason to regard an ape's multisign utter- Structure (Mouton, The Hague, 1957); M. atic. At worst, the teachers' reports under-

Gross, M. Halle, M. P. Schuztenberger, Eds., estimated the extent to which Nim signed.

ance as a sentence. The Formal Analysis of Natural Languages 26. A complete listing of Nim's vocabulary, includ-

Our results make clear that any new (Mouton, The Hague, 1973); J. Katz and P. M. ing the topography of each sign and context in

Postal, An Integrated Theory of Linguistic De- which it occurred, can be found in (17, Ap-

study of an ape's ability to use language scription (MIT Press, Cambridge, Mass., 1964). pendix C).

16. Nim was born on 21 November 1973 at the Insti- 27. B. T. Gardner and R. A. Gardner, Bull Psy-

must collect a large corpus of utterances, tute for Primate Studies in Norman, Okla. On 3 chon. Soc. 4 (No. 4a), 264 (1974); Minn. Symp.

in contexts that can be readily docu- December 1973, Nim was flown to New York Child Psychol. 8, 3 (1974).

accompanied by Mrs. Stephanie LaFarge, who, 28. Word order is but one of a number of ways in

mented by reference to a permanent vi- along with her family, raised Nim in their home which a language can encode different mean-

sual record (67). With such data one on New York's West Side for 21 months. Be- ings. When, however, regularities of sign order

tween 15 August 1975 and 25 September 1977, can be demonstrated, it does provide strong evi-

would be left with an incomplete basis Nim lived on a university-owned estate dence for the existence of grammatical struc-

ture. Given the difficulty of documenting other

for comparing an ape's and a child's use (Delafield) in Riverdale, N.Y., in a large house

with private grounds where he was cared for by aspects of an ape's signing, regularities of sign

of language. four to five resident trainers. Nim formed partic- order may provide the simplest way of demon-

ularly close attachments with certain members strating that an ape's utterances are grammatical

For the moment, our detailed investi- of the project. H. S. Terrace was the only proj- [U. Bellugi and E. S. Klima, The Signs of

gation suggests that an ape's language ect member who maintained a strong and a con- Language (Harvard Univ. Press, Cambnidge,

tinuous bond with Nim throughout the project. Mass., 1979); H. W. Hoemann, The American

learning is severely restricted. Apes can During the first 18 months of the project, Mrs. Sign Language: Lexical and Grammatical

learn many isolated symbols- (as can LaFarge was the most central person in Nim's Notes with Translation Exercises (National As-

life. After he was moved to Delafield, Nim be- sociation of the Deaf, Silver Spring, Md., 1975);

dogs, horses, and other nonhuman spe- came closely attached to L. A. Petitto, who su- E. S. Klima and U. Bellugi, Ann. N.Y. Acad.

Sci. 263, 255 (1975); H. Lane, P. Boyes-Braem,

cies), but they show no unequivocal evi- pervised his care both at Delafield and in a spe-

cial classroom built for Nim in the Psychology U. Bellugi, Cog. Psychol. 8, 262 (1976)].

dence of mastering the conversational, Department of Columbia University. After Pet-

itto left the project (when Nim was 34 months

29. In ASL, the segmentation of combinations into

signs has a function similar to that of the seg-

semantic, or syntactic or tion of old), Nim became closely attached to two resi- mentation of phrases into words in spoken lan-

language.-r dent teachers at Delafield, W. Tynan and J. But- guage: segmentation delineates sign sequences

ler. From September 1974 until August 1977, that are immediately related to one another.

Nim was driven to his classroom at Columbia Other segmentation devices as well are used in

Rae im-is gaid NOWe three to five times a week where he was given ASL. In addition to the relaxation of the hands,

intensive instruction in both the expression and specific head and body shifts, and specific facial

1. B. T. Gardner aad R. A. Gardner, J. Exp. Psy- the comprehension of signs and where he could expressions signal constituent boundaries

chol. Gen. 1I (No. 3),.244 (97S). also be observed, photographed, and videotaped [Stokoe et al. (8); E. Brown and S. Miron,-J.

2. R. A. Gardner and B. T. Gardner, Ann. N. Y. by other teachers with a minimum of distraction Verbal Learn. Verbal Behav. 10. 658 (1971);

Acad. Sdt. A09.31(197).- (through a one-way window). Nim was also H. Lane and F. Grosjean, J. Exp. Psychol. 97,

3. __, ibid. 157,752(1WS). taught regularly at Delafield, although in a less 141 (1973)].

4. D. Pre k Sdese 172, 84 (1971). formal manner. Extensive analyses of his sign- 30. Two rules were used in combinations containing

5. ,J. Fz. Anal. Beh'. 14, 107 (1970). ing at Delafield and in the Columbia classroom signs which were repeatedsuccessively. These

6. ,Intellee iApt and fan (Lawrence revealed no systematic differences in any of the rules ensured the shortest possible description

Erlbaum A , Hlladale, N.J,X, 1976). aspects of Nim's signing reported in this study. of a particular combination. For homogeneous

7. J. C. Woodward, Sign Lan. Stud. 3, 39 During the 46 months in which he lived in New combinations, if all signs in a sequence were the

(1973); H. Borsein, in Sign L48age of the

Deaf.: Psychological, Lingustic. Wa Sociologi-

York, Nim was taught by 60 nonpermanent vol-

unteer teachers. As he grew older, Nim's emo-

same (eat eat eat), the sequence was treated as a

single sign utterance (eat). Homogeneous se-

cal Perspectives,! . . Sh sad L. Nam- tional reactions to changes in personnel in- quences of signs were not tabulated as combina-

ir, Eds. (Academi9a, N7 Yo 1978), pp. tensified, and it became increasingly difficult for tions. For heterogeneous sequences, if a partic-

338-361; W. C. StIkoe et a. . t pften as- new teachers to command Nim's attention. By ular sign was repeated, immediate repetitions of

sumed erroneousy thati alfual-vi- September 1977, it was clear that we did not that sign were not counted. For the purpose of

seal communication are ASL. w r, sign have the resources necessary to hire a staff of tabulation within the corpus, a sequence such as

languages vary along a c m. At one qualified permanent teachers who could ad- banana me me me eat was reduced to banana

extreme is ASL, ic p uiwque gram- vance the scientific aspects of the project. Our me eat. Whereas the original sequence con-

mar, exprEsive devices;, a toQpoogy. The choice was to provide "babysitters" who could tained five signs, this combination was entered

natural language i- N a i can deaf look after Nim, but who were not uniformly as a three-sign sequence. In general, the sign Y,

people, ASL u learned as a e by qualified to further Nim's understandin8 of sign repeated in succession n times, was counted as a

many deaf people, especially *e chidren language, or to terminate the project. With great single occurrence of Y, independently of the val-

of deaf parent. At the oite extreme is reluctance, we decided on the latter course of ue of n. The entries shown in Table I represent

Signed English, a c for e i English in action. On 25 September 1977, Nim was flown the number of types and tokens of Nim's linear

a manual-vinsual mode. I Sgednlish-but back to his birthplace in Oklahoma. A fuli de- combinations observed to occur before the re-

not in ASL-sps are ued is word or- scription of Nim's history and socialization can duction rules were used. A complete listing of

der with signed equivaeat of MORes, such be found in (17). Nim's combinations that resulted from the appli-

as -ed and -ly. 1n SiWi g sh (PSE), 17. H. S. Terrace, Nim (Knopf, New York, 1979). cation of the reduction rules can be found in Ter-

ASL s toeher with s t expressive 18. R. S. Fouts and L. Groodin, Bull. Psychon. Soc. race et al. (31). In ASL, repetitions of a sign

devices in English word order without the 4 (No. 4a), 264 (1974). convey particular meanings. One type of con-

grammatical inorphemes of English, are used. 19. L. Bloom, Language Development: Form and trast between repeated and nonrepeated signs is

Hearing persocs terely achieve "uativelike" Function in Emerging Grammars (MIT Press, exemplified by the contrast between the forms

ctrol over th copesttuan ad grammar Cambridge, Mass., 1970). of certain nouns and verbs. Many verbs (sweep,

of ASL. Ia this oh se oa signing 20. __, One Word at a Time: The Use of Single fly, drive) are made with a single motion. Re-

lbavior inE n1Al. w¢ used. In

this sense, its -tihing to t their signing

Word Utterances Before Syntax (Mouton, The

Hague, 1973).

lated nouns (broom, airplane, car) are made by

repeating a sign twice (the so-called double

"ASL" since do

it doe exhibitlhe gamatical 21. L. Bloom and M. Lahey, Language and Devel- bounce form; see T. Suppala and E. Newport,

ucc01fit

strauctre _.4'--

thatlumas '' 'D

8. W. C. Stoloe, J.. C l,C. C. Cron-

opment and Language Disorders (Wiley, New

York, 1978).

personal communication). None of Nim's teach-

ers could distinguish between the meanings of

berg, Eds.,A Dkitioy n Sign Lan- 22. R. Brown, A First Language: The Early Stages utterances that did and did not contain signs that

iaenL Ggg b G ud College (Harvard Univ. Press, Cambridge, Mass., 1973). were repeated successively. Emphasis appears

23. J. A. Fodor, T. G. Bever, M. F. Garrett, The to be their sole function. Overall, less than 15

9D. M. Rumbaugh, E4., Leqrning by a Psychology of Language (McGraw-Hill, New percent of the linear utterances we observed

Chdeqpanzee: T>e La F iet(Academic York, 1978). contained successively repeated signs. As far as

Press. New po,97N.,515 24. M. Braine, Monogr. Soc. Res. Child Dev. 41 we could tell, the outcomes of our analyses

(1), Serial No. 164 (1976). would be unchanged if we included utterances

(1972); M. K.T n Lut* G Up Hu- 25. An imitative sign is one which repeats the teach- containing signs that were repeated successive-

man (Scieue and ehaiori Books, Palo Alto, er's immediately prior utterance. A spontaneous ly.

sign is one that has not occurred in the teacher's 31. H. S. Terrace, L. A. Petitto, R. J. Sanders,

FF. G. Ptten, BriA Lang. 12, 72 (1978). immediately prior utterance. A prompted sign T. Bever, in Children's Language, K. Nel-

P. ea m. N.F. Acad. Sci. 280, 660 follows a teacher's prompt. A prompt uses only son, Ed. (Gardner Press, New York, in press),

. 1975). part of the proper sign's confiration, move- vol. 2.

< C. Hayes, The APe in Ovr Hoses (Harper & ment, or location. For example, the teacher 32. Other complete listings of the regularities of

Row, New York, ?A Wl)s.St.F. Hk yes and C. might prompt Nim (first and second fingers Nim's two-sign combinations can be found in

(t7).

Hayes, I4c. 4A ;. O, IOS (1951); drawn down the temple) by extending those two

W. N.K Scie**ce 423 (1968); fingers from a fist. Agreement between teachers' 33. That there are more tokens of two-sign combina-

Wand. .ad the Child reports and transcripts of an independent ob- tions containing me than containing Nim is per-

(>Graw- ,NeW ouk, l93¢ N. N. Lady- server (who either watched Nim and his teacher haps best explained by the fact that Nim learned

:ua-Kots, Apg6nJItlusCeAI4 (Museum through the one-way window of his Columbia the sign me before he learned the sign Nim. Sub-

sequently the frequencies with which Nim and

classroom or who transcribed videotapes)

14. Univ. ranged between 77 and 94 percent. Virtually all me were combined with transitive verbs was es-

23 NOVEMB 1979 901You can also read