Tourist Expectations and Motivations in Visiting Rural Destinations. The Case of Extremadura (Spain)

←

→

Page content transcription

If your browser does not render page correctly, please read the page content below

doi:10.5477/cis/reis.175.105

Tourist Expectations and Motivations

in Visiting Rural Destinations.

The Case of Extremadura (Spain)

Expectativas turísticas y motivaciones para visitar destinos rurales.

El caso de Extremadura (España)

Marcelo Sánchez-Oro, Rafael Robina-Ramírez,

Antonio Portillo-Fernández and Héctor Valentín Jiménez-Naranjo

Key words Abstract

Rural Areas According to the UNWTO (2020), Spain received 83.7 million tourists

• Countryside in 2019. To our knowledge, few studies have delved into the impact of

Experiences tourism on Spanish semi-depopulated areas. This article aims to develop

• Tourist Expectations an explanatory model of tourist motivations and expectations in visiting

• Pull Factors those areas in the Region of Extremadura, in south-west Spain. The model

• Maslow uses Maslow’s hierarchy of needs to rank factors such as the destinations’

• Motivation socioeconomic conditions and tourists’ satisfaction with their experience.

• Tourism The sample consisted of 6,106 personal interviews with visitors. The

hypotheses about causal relationships were formulated by using a

multivariate analysis model. The variables that explained the reasons for

making a trip to these types of regions were essentially socioeconomic

(SEC). The model can be applied to other social and territorial contexts to

verify whether the hierarchy of motivations takes different forms.

Palabras clave Resumen

Áreas rurales Según la OMT (2020), España recibió 83,7 millones de turistas en

• Experiencias rurales 2019. Hasta donde sabemos, pocos estudios han profundizado en qué

• Expectativa turística mueve a los turistas, realmente, a visitar las zonas semidespobladas

• Factores de atracción de España. Este artículo tiene como objetivo desarrollar un modelo

• Maslow explicativo de las motivaciones y expectativas turísticas en áreas del

• Motivación sudoeste de España, particularmente Extremadura. El modelo que

• Turismo presentamos clasificó, partiendo de la jerarquía de necesidades de

Maslow, algunos factores que la literatura considera relevantes, como

son las condiciones socioeconómicas de los visitantes y la satisfacción

de la experiencia turística. La muestra consta de 6.106 entrevistas

personales realizadas a visitantes. Las hipótesis sobre las relaciones

causales se plantean a través de un modelo de análisis multivariado.

Las variables que explican las razones para hacer un viaje a este tipo

de regiones son esencialmente socioeconómicas (SEC). El modelo se

puede aplicar en otros contextos sociales y territoriales para verificar si

la jerarquía de motivaciones toma diferentes formas.

Citation

Sánchez-Oro, Marcelo; Robina-Ramírez, Rafael; Portillo-Fernández, Antonio and Jiménez-Na-

ranjo, Héctor Valentín (2021). “Tourist Expectations and Motivations in Visiting Rural Destinations.

The Case of Extremadura (Spain)”. Revista Española de Investigaciones Sociológicas, 175: 105-128.

(http://dx.doi.org/10.5477/cis/reis.175.105)

Marcelo Sánchez-Oro: Universidad de Extremadura | msanoro@unex.es

Rafael Robina-Ramírez: Universidad de Extremadura | rrobina@unex.es

Antonio Portillo-Fernández: Universidad de Extremadura | antoniofp@unex.es

Héctor Valentín Jiménez-Naranjo: Universidad de Extremadura | hectorjimenez@unex.es

Reis. Rev.Esp.Investig.Sociol. ISSN-L: 0210-5233. N.º 175, July - September 2021, pp. 105-128106 Tourist Expectations and Motivations in Visiting Rural Destinations. The Case of Extremadura (Spain)

Introduction health tourists (Voigt, Brown and Howat,

2011), backpackers and independent trav-

Motivation is a driver that moves individuals ellers (Murphy, 2001), cultural tourists (Tan,

to take action (Schiffman and Kanuk, 2003). Luh and Kung, 2014), among others. This

It has become a key factor in the tourism paper aims to contribute to the study of the

sector in ascertaining tourists’ expectations motivations in visiting rural destinations. This

in initiating the desire to travel (Zhang and is done by analysing the reasons offered for

Peng, 2014). tourist satisfaction, experience and socio-

Numerous papers have explored tour- economic characteristics (Devesa, Laguna

ists’ motivations in rural areas from differ- and Palacios, 2010; Jiménez-Naranjo et al.,

ent angles, including the perception of the 2016).

host (Bitsani and Kavoura, 2014), rural-ur- Tourist motivations can be classified and

ban inter-relationship (Hernández, Suárez- explained by linking Maslow´s model of hier-

Vega and Santana-Jiménez, 2016; Zheng archy of needs to the world of human needs

et al., 2019), sustainable rural tourism (Mar- satisfaction (Pearce, 1988, 1994; Pearce and

tínez et al., 2019; Su et al., 2019), and rural Caltabiano, 1983; Moscardo and Pearce,

entrepreneurship (Jaafar and Rasoolimanesh, 1986; Šimková and Holzner, 2014; Han,

2015). There have also been a large number 2019). Few studies to date have used this

of theories about tourist motivation and methodology in inland areas in southern Eu-

methodology (Araújo and Sevilha, 2017; rope, such as the Extremadura Region. Smart

Hsu and Huang, 2008; Kao, 2008; Kim, Lee PLS Path Modelling has been applied in an at-

and Klenosky, 2003; Robina-Ramírez and tempt to define any relationships among vari-

Pulido-Fernández, 2018a). ables (Jiménez-Naranjo et al., 2016; Robina-

The main one is the “push pull theory”, Ramírez and Fernández-Portillo, 2018).

which has been broadly explored to investi- The paper is structured into five sec-

gate tourist motivations as factors underlying tions. Section one contains the introduc-

tourist behaviour. Whereas “push” stresses tion, which is followed by a discussion of

what drives the decisions to travel, “pull” the materials and methods in the theoreti-

studies the reasons that cause the specific cal section. This addresses the reasons and

selection of the destination (Klenosky, 2002). motivations reported by tourists for travel-

Very little consensus has been reached on ling to Extremadura, as well as an analysis

“pull” theories to date; in other words, on of tourist motivation based on Maslow’s hi-

what motivates an individual to engage in erarchy of needs. Section three contains the

travel (Filep and Greenacre, 2007; Pearce, methodology, and section four discusses

2011). Pearce (2011) identified motives that the statistical analysis, based on the struc-

were organised into three layers. Layer one ture equation modelling used. The paper

includes: to experience novelty; the need to provides some conclusions in section five.

escape and relax; and to build relationships;

layer two relates to the close contacts de-

veloped by experienced tourists; and layer Material and methods

three includes the desire for isolation and

having romantic relationships. Araújo and Tourist motivation. Relevance and

Sevilha (2017) stressed that the motives for consequences

tourist travel lie in market niches: golf play-

ers (Kim and Ritchie, 2012), cruise travel cli- Castaño (2005: 142) highlighted three at-

ents (Hung and Petrick, 2011), adventure tributes of tourist travel: reasons (why),

tourists (Schneider and Vogt, 2012), wellness destination (where) and outcomes (satis-

Reis. Rev.Esp.Investig.Sociol. ISSN-L: 0210-5233. N.º 175, July - September 2021, pp. 105-128Marcelo Sánchez-Oro, Rafael Robina-Ramírez, Antonio Portillo-Fernández and Héctor Valentín Jiménez-Naranjo 107

faction). According to Beltrán-Bueno and 2011; Coghlan and Pearce, 2010; Harril and

Parra-Meroño (2017), previous models re- Potts, 2002; Iso-Ahola, 1982; Moscardo,

lated to tourist expectations relied on push 2011; Pearce, 2005; Pearce and Uk-ll,

factors vs. pull factors (Crompton, 1979) to 2015; Robina-Ramírez and Pulido-Fern-

study the motivational typology of visitors ández, 2018b). Although research on tour-

in the Region of Murcia. As a result, a spe- ism motivation has been approached from

cific typology of visitors was constructed different points of view, few of them have

based on four types: the rationalist, the an- taken into account Maslow’s hierarchy of

thropologist (culture, exploration and eval- needs theory (1954). This groups together

uation of the self), the emotional, and the motivational factors including cultural and

hedonistic. educational needs; the desire to visit places

and enjoy works of art, archaeological sites,

Devesa, Laguna and Palacios (2010a:

cultural heritage, natural areas; needs re-

170) associated motivation and satisfac-

lated to health; need to relax and move

tion with the tourist experience. They ap-

away from ordinary life, both socially and

plied their model to inland tourism in order

as a family; need for consumption and pur-

to analyse the relationship between mo-

chasing; and an aspiration to have a hedon-

tivation, satisfaction and loyalty, specifi-

istic, pleasant life (Huete, 2009: 64). Tour-

cally in connection with a destination in the

ist motivation is stimulated by a complex

Province of Segovia. They hypothesised

set of economic, social, psychological, cul-

that visitors have different motivations,

tural, political and environmental influences

which affect satisfaction and the attributes

(Huete, 2009: 63 and following). When tour-

of the trip and the destination. In addition,

ists are asked about the purpose of travel-

satisfaction and motivation affect loyalty to ling, their answer usually includes relaxing,

the destination, which is considered an at- becoming acquainted with historical and

tribute that involves an increased (or de- cultural heritage sites, business, visiting rel-

creased) frequency of a visitor to a certain atives or friends, enjoying nature, etc.

destination.

At first sight, the reasons for travelling

In this line, Huete (2009: 65) pointed out seem to be self-explanatory, which sug-

that there are determining social and demo- gests that it may not be necessary to fur-

graphic factors in motivation and expecta- ther enquire into the underlying reasons.

tions, including age, —related to leght of However, there are motivations that reflect

stay—, type of transport, distance, and so- both desires and individual needs. Mill and

cial variables such as family relationships Morrison (1992: 17) studied the reasons

associated with people’s life cycle. For for travelling that give rise to the difference

Csikszentmihalyi and Coffey (2016), motiva- between a travel “agent” and a tourism

tional variations should be set in relation to “promoter”. Whereas a travel agent is con-

cultural differences throughout the traveling cerned with selling airline seats or hotel res-

experience to allow for a better understand- ervations, a tourist promoter is concerned

ing of how multiple or changing motives with marketing dreams and expectations.

might be associated with well-being. Those Mayo and Jarvis (1981) established four

motivational variations emerge when at- categories of motivations: physical motiva-

tempting to answer the question about the tors (sport, beach entertainment and relaxa-

reasons for and the rewards to be obtained tion, physical health); interpersonal motiva-

from travelling. tors (meeting new people, visiting friends,

There are wide-ranging motivational rea- escaping from routine); cultural motivators

sons for travel (Chen, Mak and McKercher, (discovering new countries, places, dance,

Reis. Rev.Esp.Investig.Sociol. ISSN-L: 0210-5233. N.º 175, July - September 2021, pp. 105-128108 Tourist Expectations and Motivations in Visiting Rural Destinations. The Case of Extremadura (Spain)

music...); and, finally, motivator regarding There are at least two other lines of re-

status and social prestige (desire to be ad- search that also study tourism motivation.

mired and even envied by the destinations The first of these is derived from Maslow’s

people travel to and their experiences, and hierarchy of needs. It measures the impor-

reputational reinforcement). tance and the reasons given by tourists for

The Lanquar classification, which has travelling to a specific place using Likert-

been accepted by the World Tourism Or- type scales. It provides accurate knowledge

ganization (UNWTO) (Lanquar, 1985), estab- about the motivations that push tourists

to visit Extremadura, a remote place in the

lishes a classification based on three groups:

south-west of Europe. The second is based

personal motivations (contact with nature,

on a scale of 16 attributes related to tourist

escape and need for knowledge); family and

destinations (Cossens, 1989).

tribal motivations (experience involved in liv-

ing with a family different from the one in All the scholars mentioned above have

everyday life, need for family reunification, agreed that motivations vary according to

discovering the environments where ances- the positive or negative character of the

tors lived); and social motivations (imitation, tourist experience (Castaño, 2005: 144). In

prestige, obtaining uniqueness, searching the case of positive experiences, the needs

for authenticity, evasion, new experiences). at the lower end of the Maslow scale are

In addition, Schmidhauser (1989) studied the not involved. However, when the tourism

leisure-work relationship, within which trips experience has been negative, those “low-

to visit friends and relatives, business trips, end” needs have a more active presence.

The greater the experience and maturity of

and trips for health reasons were the main

tourists, the greater their concern about the

tourist motivations. Pearce and Caltabiano

high-end needs in the Maslow scale.

(1983) developed the Maslow theory on the

basis of 5,000 surveys of Canadian travellers As a consequence of these differences,

from ten cities. Pearce (1988, 1994) adapted Maslow’s hier-

archy of needs and applied it to tourist mo-

tivations, ordered as follows: at the base of

The analysis of tourist motivation based the pyramid is the need for relaxation (rest/

on Maslow’s hierarchy of needs activity), followed by the need for stimulation

(security, strong emotions), the social order

As a motivational factor, Maslow’s pers- needs (family relations, friendship relations,

pective has been part of tourism research couples) are in third place; in the fourth place

for decades, although the methodology are self-esteem needs (personal, cultural, his-

about the motivational aspects of tourism torical development, environmental); the need

has not been properly addressed (Todd, for self-realisation and the search for happi-

1999). Regarding research that has relied ness is also included. But there are also con-

on Maslow’s motivational scheme (McIn- textual variables that more broadly explain the

tosh, 1977; Mayo and Jarvis, 1981; Pearce issue of motivation for travel and the choice of

and Caltabiano, 1983, cited by Castaño, tourist destination. These include the person-

2005), while the information provided is ality of the individual, as evidenced by Plog

adequate, the hierarchy of needs split into (1977) in his classic typology of psychocen-

five levels is still highly debated amongst tric, mid-centric, and allocentric travellers.

scholars (Lucas and García, 2002: 142). According to Pearce (1994), the theory of

Despite this lack of theoretical consensus, hierarchy needs should be applied to tourism

the model is currently widely used. by using the “Travel Career Ladder” concept

Reis. Rev.Esp.Investig.Sociol. ISSN-L: 0210-5233. N.º 175, July - September 2021, pp. 105-128Marcelo Sánchez-Oro, Rafael Robina-Ramírez, Antonio Portillo-Fernández and Héctor Valentín Jiménez-Naranjo 109

(TCL). The core idea underlying this concep- 2010; Hsu, Cai and Wong, 2007; Lee, Lee and

tual framework is that an individual’s moti- Wicks, 2004; Severt et al., 2007).

vation for travelling changes with their travel From our perspective, any contribution to

experience. It suggests that people’s travel the literature should analyse tourists’ moti-

needs change over their life span and with ac- vational needs when visiting certain specific

cumulated travel experience. However, Araújo areas. In other words, to ascertain what type

and Sevilha (2017) found gaps in Pearce´s of needs travellers need to have satisfied in

theory. As a result, the individual’s travel mo- specific areas based on Maslow’s theory.

tivation changes according to the tourism cul-

tures they encounter, and to the reasons as-

sociated with being in contact with nature. The characteristics of the tourism flow

Moreover, factors such as age, spending ca- into Extremadura and sampling

pacity and even nationality should be taken

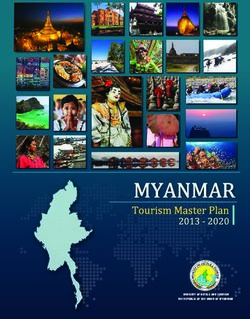

into account. These variables can cause sig- Extremadura (see Figure 1) is a region with

nificant variations in tourist motivations (Swar- a population of just over one million one

brooke and Horner, 2002). hundred thousand, which represents 2.3%

of the population of Spain (see Figure 1). Its

More recent studies on tourist motiva- population density is 26.4 inhabitants/km2.

tion have also focused on the reasons for The small proportion out of the total Spa-

the existence of significant variations in spe- nish population and the small occupation of

cific market segments, such as golfers (Kim the region are essential features of its de-

and Ritchie, 2012), cruise travel (Hung and mographic structure (Pérez, 2014: 239).

Petrick, 2011), adventure tourists (Schnei-

According to the Statistics Unit of the

der and Vogt, 2012), wellness tourism (Voigt,

Directorate General of Tourism of the Gov-

Brown and Howat, 2011), backpackers and

ernment of Extremadura, 1,866,168 trav-

independent travellers (Murphy, 2001), cul-

ellers visited the region in 2018 (Statistical

tural tourism (Tan, Lu and Kung, 2014), and

Unit, 2019). 83% of these visitors to Extre-

diving (Ong and Musa, 2012), among others.

madura were Spanish, and 17% were from

Variations in tourism motivation have been

other countries. Extremadura is relatively

focused on locating the more characteristic isolated in southern Europe, and it is not

motivations for each tourism sector. well connected by rail or by air. The number

Reasons for travelling to a certain destina- of visitors to the region represents 1.43%

tion are complex and may be related to pre- of the people who travel to Spain. In terms

vious experience and available information of the number of travellers it receives, Ex-

(Castaño et al., 2003). Multiple dimensions tremadura occupies the 14th position in the

should therefore be used to explain tourist ranking of the 17 Spanish autonomous re-

motivation (Pearce, 1993; Devesa, Laguna, gions (Statistical Unit, 2019: 6).

and Palacios, 2010: 4; Parrinello, 1993). Tour- Tourism is a temporary displacement

ist motivation, visitor satisfaction and loyalty whereby people travel outside their usual

to the product or destination through market place of residence, mainly for leisure (Jimén-

segmentation have been increasingly valued ez-Naranjo et al., 2016), but also for reasons

by scholars as key components of motiva- to do with visiting historical and cultural her-

tion (Devesa, Laguna and Palacios, 2010: 4). itage sites, family or friends, business and

As a result, interest in tourist motivation and other reasons (INE, 2004: 3-6). According to

market segmentation has increased in re- the surveys conducted by the Observatory of

cent years (Beh and Bruyere, 2007; Cervantes Tourism in Extremadura (Observatorio de Tur-

et al., 2000; Devesa, Laguna and Palacios, ismo de Extremadura, 2018) 54% of respond-

Reis. Rev.Esp.Investig.Sociol. ISSN-L: 0210-5233. N.º 175, July - September 2021, pp. 105-128110 Tourist Expectations and Motivations in Visiting Rural Destinations. The Case of Extremadura (Spain)

ents chose Extremadura as their main travel came to Extremadura as a member of larger

destination, and more than half came to Ex- groups. They preferred to travel to the region

tremadura to visit the historical-artistic herit- in their private vehicle (85.3%) and by bus

age sites in the region. Some 16.2% visited (7%). A total of 61% had no relationship with

natural spaces. A total of 43% of respondents Extremadura, whereas 26% had family and

travelled with their partner, and 33% visited friendship ties, and 8.4% reported they had a

the region with their families. Some 14.4% second home in the region.

FIGURE 1. Extremadura (Spain). Turistic zones

Salamanca

Beiras Alta e

Serra da Estrela

Ávila

Sierra de Gata, Valle del Ambroz,

Las Hurdes, Tierras de Granadilla

Valle de Alagón Valle del Jerte,

La vera

Plasencia

Reserva de la

Beira

Biosfera de Monfragüe

Baixa

Toledo

Tajo Internacional,

Sierra de San Pedro

Cáceres

Geoparque

Villuercas

Ibores-Jara

Trujillo, Miajadas,

Montánchez

Alto

Alentejo

Badajoz Mérida

Vegas del

Guadiana

Ciudad

Alentejo Real

La Siberia, La Serena,

Central Tierra de Barros, Campiña Sur

Zafra

Alqueva,

Sierra Suroeste, Córdoba

Tentudia

Baixo

Alentejo

Huelva Sevilla

Source: Observatorio de Turismo de Extemadura, Quarterly bulletin of tourism supply and demand in Extremadura Fourth

quarter 2018 Document (14/2018), p. 78. https://www.viajarporextremadura.com/cubic/ap/cubic.php/doc/Guia-de-Extrema-

dura-11.htm

Reis. Rev.Esp.Investig.Sociol. ISSN-L: 0210-5233. N.º 175, July - September 2021, pp. 105-128Marcelo Sánchez-Oro, Rafael Robina-Ramírez, Antonio Portillo-Fernández and Héctor Valentín Jiménez-Naranjo 111

The main reason given by respondents to Building an explanatory model based on

travel the region was “visiting the historical-ar- socioeconomic characteristics, satisfaction

tistic heritage of the region” (62.35%), “visiting with tourist experiences and evaluation of

natural spaces and hiking” (11.38%) and “vis- specific resources and facilities in the terri-

iting family and friends” (5.62%). Tourist vari- tory can contribute to a better understan-

ables were measured on a Likert-type scale, ding of the motivations of those who plan to

ranging from 1 (very poor), to 5 (very good). visit the area.

These were services and the infrastructure of Three specific objectives were set: 1) to

the region: road signs for access to the area, analyse what motivates tourists to visit Ex-

tourist infrastructure, conservation of the ar- tremadura, by using a large sample (6,108

tistic historical heritage sites, the natural en- tourists). These reasons wåill then be adap-

vironment, signposting, local gastronomy, ted and classified according to Maslow’s hie-

professional staff in establishments, hospital- rarchy of needs (Pearce, 1988, 1994); 2) to

ity and friendly population in general. Average explore ranges of correlated reasons such

stated expenditure per person per day was as socioeconomic satisfaction and territorial

€86.15 (€88.55). Overall, 73% of respondents characteristics to choose Extremadura as a

claimed to have spent less than €100 per day

potential destination, by using a descriptive

per person. Some 86.90% of respondents

approach; 3) to develop a structural equa-

were Spanish, while 13.1% were from other

tion motivational model based on three di-

countries. Half of the respondents were men,

mensions: a) socioeconomic variables, age-

and the average age was 50.09 years old

nationality-spending; b) evaluative variables,

(Sánchez-Oro et al., 2019).

including tourist experience, and assessment

of tourist services and infrastructures in Extre-

Methodology madura; and c) variables of satisfaction with

the tourist experience, such as satisfaction

Objectives

with the treatment received from hospitality

This paper investigates the motivation of professionals and welcome by the population

tourists who travel to rural destinations in the (Baloglu and McCleary, 1999).

Extremadura Region, in order to expand its Table 1 shows the survey’s characteris-

popularity amongst the tourism industry. tics.

TABLE 1. Characteristics of the survey

Sample Characteristics

Tourists visiting Extremadura in 2018 (INE data) 1,866,168, obtained by the Observa-

Population

tory of Tourism of Extremadura.

Geographical area Extremadura.

Size of the survery 6,108.

Survery 22 questions randomly delivered amongst the regional population.

Significance level (NC) 95%

Sample error ± 1.3%, in the case of maximum indeterminacy, p = q = 50%, p = 1–q

Data extracted October and December 2018.

Data stratified According to age and sex in the regional territory.

Source: Own elaboration.

Reis. Rev.Esp.Investig.Sociol. ISSN-L: 0210-5233. N.º 175, July - September 2021, pp. 105-128112 Tourist Expectations and Motivations in Visiting Rural Destinations. The Case of Extremadura (Spain)

Hypotheses and sample from the Extremadura Region between Octo-

ber and December 2018 by the Observatory

The main question was whether the reasons of Tourism of Extremadura. It used stratified

for travelling to relatively isolated rural areas random sampling (according to territorial quo-

of southern Europe were based on satisfac- tas, age and sex) and a maximum variation

tion with tangible aspects (infrastructure, sample (p = 1–q = 50%), with a margin of er-

conservation of the environment, gastro- ror of ± 1.3% and a confidence level of 95%.

nomy), and/or intangible aspects (courtesy,

hospitality) of the tourist destination con-

ditioned by socioeconomic variables such Data processing and variables

as age, nationality and level of expenditure.

Following Caballero (2006) and Shmueli and The data processing was initially conducted

Koppius (2011), a positive relationship bet- by describing the variables, followed by using

ween both variables was established. This a structural equation model to establish the

relationship is in alignment with the studies dependency relationship between the varia-

presented by these authors, and the litera- bles. The system of structural equations has

ture (Baloglu and McCleary, 1999; Castaño, an advantage over other systems and mul-

2005; Devesa, Laguna and Palacios, 2010a, tivariate techniques, as it analyses the rela-

2010b; Bojollo, Pérez and Muñoz, 2015). tionships inherent in each subset of variables,

The following hypotheses were proposed: also allowing for interrelations between them.

“Tourist expectations” (TEs) concerned

H1. Socioeconomic conditions (SECs), na-

two questions. The first involved the mo-

mely age, country and spending, deter-

tives for travelling adduced by respondents

mine tourist expectations (TEs).

(TEs1). These reasons, initially expressed

H2. Socioeconomic conditions (SECs), na- in the questionnaire by choosing between

mely age, country and spending, deter- a nominal battery of options, was hierar-

mine the accommodation motivation re- chised to adapt them to the Maslow scale.

lated to professionalism and hospitality According to Pearce and Caltabiano (1983),

or hospitality motivation (HM). the second component of this variable was

H3. Accommodation motivation related to “what the visitor did” at the destination

professionalism and hospitality (HM) (TEs2).

determines tourist expectations (TEs). “Socioeconomic Conditions” (SECs), in-

H4. Socioeconomic conditions (SECs), na- cluded age, daily spending reported by re-

mely age, country and spending, deter- spondents, and nationality.

mine secondary motivations, such as

appropriate signposting, infrastructure

and road signs (SMs). laboration agreement signed between the Directorate

General of Tourism and the University of Extremadura

H5. Secondary motivations such as appro- for the of Tourism and the University of Extremadura for

priate signs, infrastructure and road the study of tourism in the region during 2018. We would

therefore like to thank Mr. Francisco Martín Simón for the

signs (SMs) determine tourist expecta-

trust placed in our team, Director General of Tourism of

tions (TEs). the Junta de Extremadura (Spain). We would also like to

thank for their collaboration and commitment the techni-

The sample used for this study consisted cians of the Tourist Offices of Extremadura, the research-

ers Ana Nieto Masot and Yolanda García García, and the

of 6,106 personal interviews1 with visitors

Yolanda García García, as well as the research assist-

ants Gema Cárdenas Alonso and Jennifer González. Fi-

nally, this work is also possible thanks to the GR18052

1 The data used for this publication were made possi- grant, financed by both the Junta de Extremadura and

ble thanks to the thanks to the inter-administrative col- the European Regional Development Fund (ERDF).

Reis. Rev.Esp.Investig.Sociol. ISSN-L: 0210-5233. N.º 175, July - September 2021, pp. 105-128Marcelo Sánchez-Oro, Rafael Robina-Ramírez, Antonio Portillo-Fernández and Héctor Valentín Jiménez-Naranjo 113

“Hospitality Motivations” (HM) were ven, 90% of the respondents only gave one

treated as an independent variable, and re- reason for their trip. As can be seen in Ta-

ferred to the satisfaction with an intangible ble 2, 71.7% of the Spanish nationals who

aspect, such as professionalism of staff travelled to Extremadura stated that the

(HM1) and hospitaly and friendliness of the reasons for level 4 were linked to personal

population (HM2). development and self-esteem, which was

Secondary motivations referred to the based on visiting cultural and historical-ar-

satisfaction of visitors with tangible aspects tistic heritage sites in the region. This block

of the tourism experience: signposting and also included the question “What activities

infrastructure, conservation of the natu- have you done or intend to do, during your

ral environment and local gastronomy. This stay in the region?”. This was structured in

variable is called “Secondary Motivations the same way as the previous one and in-

such as appropriate signposting, infrastruc- volved an additional element in tourists’ in-

ture and road signs (SMs)”. tentions. This was treated in the same way

as the descriptive values in Table 2.

In short, the structure of the associa-

tion between the different components of Table 3 shows information about the “So-

the model took into account the variables cioeconomic Conditions: age, country and

that the literature considers in explaining spending” (SECs) of respondents. Some

tourist motivations (reasons for travelling). 64.2% were over 45 years old; 51.5% stated

These motivations, obtained from ques- that their daily expenditure was less than €60;

tions with nominal answers, were hierar- and 87% of the respondents were Spanish.

chised based on Maslow’s ordinal scale Table 4 shows data on the (HM) variable,

of needs, following Pearce and Caltabiano which referred to satisfaction with intangible

(1983). This variable has been called tour- aspects such as “professionalism”, “hos-

ist expectations (TEs). Motivation in prin- pitality, and friendly” staff providing tour-

ciple may be determined by the tourist ist services. The level of satisfaction with

experience, which is identified here with these aspects was very high, an average of

“level of satisfaction” with both tangible 4.40 and 4.66 out of 5. “Professionalism” of

and intangible aspects (SMs and HMs the establishments was considered to be

variables). There was a third determining very good by 55.3% of respondents. Some

variable in the model, namely, that of ex- 67.5% considered hospitality and friendli-

perience and maturity of tourists, opera- ness of the general population to be very

tionalised based on age, level of reported good.

expenditure and nationality (socioeco- Variables were added to the descriptive

nomic variables, or SECs). aspects of the sample that referred to the

degree of satisfaction with tangible aspects

of the tourism experience (satisfaction with

Statistical analysis the sector’s infrastructures of the sector).

Some 37.3% of the respondents gave this

Descriptive analysis the highest level of satisfaction, “5. Very

good”. A total of 43.3% of the respondents

What is the reason to come to this region? rated the conservation of the natural envi-

The questionnaire used a battery of op- ronment and signposting with the highest

tions and the answers were ordered based level of satisfaction and 52.5% expressed

on the Maslow scale of needs. While this that they were highly satisfied with local

allowed for more than one answer to be gi- gastronomy (see Table 5).

Reis. Rev.Esp.Investig.Sociol. ISSN-L: 0210-5233. N.º 175, July - September 2021, pp. 105-128114 Tourist Expectations and Motivations in Visiting Rural Destinations. The Case of Extremadura (Spain)

TABLE 2. Motives Adduced by Tourists to Travel to Extremadura and Activities They Carried Out

Tourist Motivation Reasons to travel

(TE1) (TE2)

Maslow’s Classification

n % n %

1. Need for relaxation (rest/activity) (Sports and hun-

146 1.4 8 0.1

ting activities, spas...).

2. Stimulation needs (safety, new emotions, party)

(Attend local parties, visit natural areas and hiking, 840 13.8 158 2.6

attendance to Festivals/Events).

3. Social needs (family, friends, couples but also for

467 7.6 82 1.3

work and business).

4. Reasons related to personal development and

self-esteem (Cultural visits and historical-artistic he- 4,379 71.7 2,675 4.8

ritage).

5. Need for self-realisation: search for happiness

105 1.7 3,052 50.0

(Bird Watching, Gastronomic Tasting).

Does not answer. 171 2.8 130 2.1

Total 6,108 100 6,108 100

Source: Prepared by the authors of the Annual Report of the Extremadura Tourism Observatory (2019).

TABLE 3. Socioeconomic Conditions: Age, Nationality and Spending (SECs) (n = 6,108)

Daily income

Nationallity

Age (SEC1) n % (SEC2) n % n %

(SEC3)

Euros per day

18 to 24 176 2.9 < of 20 euros 404 6.6 Spain 5,309 86.9

25 to 34 years 758 12.4 21- 40 euros 870 14.2 European Union 491 8.0

35 to 44 1,157 18.9 41-60 euros 1,204 19.7 South America 179 2.9

45 to 54 1,440 23.6 61- 80 euros 673 11.0 EE. UU. and Canada 67 1.1

55 to 64 1,361 22.3 81-100 euros 995 16.3 Asian countries 44 0.7

More than 101

65 above 1,116 18.3 944 15.5 Other 18 0.3

euros

Do not answer 100 1.6 Do not answer 1,018 16.7

Total 6,108 2.9 Total 6,108 6.6 Total 6,108 100

Source: Prepared by the authors of the Annual Report of the Tourism Observatory of Extremadura (2019).

Reis. Rev.Esp.Investig.Sociol. ISSN-L: 0210-5233. N.º 175, July - September 2021, pp. 105-128Marcelo Sánchez-Oro, Rafael Robina-Ramírez, Antonio Portillo-Fernández and Héctor Valentín Jiménez-Naranjo 115

TABLE 4. S

atisfaction with Intangible Aspects such as Professionalism, Hospitality and Friendliness of the

Staff Providing Tourist Services (HM)

(HM1) Professionalism of the staff (HM2) Hospitality and friendliness

of establishments of the general population

n % n %

1. Worst 16 0.3 12 0.2

2. Bad 65 1.1 14 0.2

3. Neutral 500 8.2 158 2.6

4. Good 2,019 33.1 1,643 26.9

5. Very good 3,379 55.3 4,120 67.5

Total 5,979 97.9 5,947 97.4

Does not answer 129 2.1 161 2.6

Half 4.45 4.66

Source: Prepared by the authors of the Annual Report of the Tourism Observatory of Extremadura (2019).

TABLE 5. S

econdary Motivations: Satisfaction with Tourist Infrastructures, Environment and Road Signs and

Gastronomy (SMs)

(SM2)

(SM4)

(SM1) The Natural (SM3)

Conservation of

The tourist Environment and Signaling of access

Historical-Artistic

infrastructures the explanatory to the territory

Heritage

signage

n % n % n % n %

Worst 33 0.5 39 0.6 149 2.4 18 0.3

Bad 102 1.7 137 2.2 140 2.3 72 1.2

Neutral 797 13.0 655 10.7 779 12.8 564 9.2

Good 2,713 44.4 2,337 38.3 2,448 40.1 2,366 38.7

Very good 2,279 37.3 2,643 43.3 1,467 40.4 2,873 47.0

Total 5,924 97.0 5,811 95.1 5,983 98.0 5,893 96.5

Does not answer 184 3.0 297 4.9 125 2.0 215 3.5

Half 4.20 4.27 4.16 4.36

Source: Prepared by the authors of the Annual Report of the Tourism Observatory of Extremadura (2019).

Reis. Rev.Esp.Investig.Sociol. ISSN-L: 0210-5233. N.º 175, July - September 2021, pp. 105-128116 Tourist Expectations and Motivations in Visiting Rural Destinations. The Case of Extremadura (Spain)

A descriptive analysis of the variables a Spanish national. This statistic of asso-

(Table 6) showed that the socioeconomic ciation of ordinal variables oscillated be-

variables (SECs) of tourists visiting inland tween -1 and +1 (García, 2008: 250). Table

regions such as Extremadura were those 5 shows that the only variables with nega-

most strongly associated with the reasons tive values in Kendall’s Tau-b were the ones

for tourists’ to visit the area (TE1). Accord- that linked the reasons provided for trav-

ing to Kendall’s Tau-b, the variables with the elling to Extremadura (TE1) to the activity

strongest association as explanatory fac- that the respondent performed during their

tors for travelling to the region were those tourist stay in the region (TE2). It can simply

related to the socioeconomic order: age, be stated that one thing was the reason for

spending and nationality. Being an adult, coming, and another was what was actually

having a medium-low level of daily spend- done once here, as they did not coincide in

ing in terms of length of stay, and being 40% of the cases.

TABLE 6. M

ean Variables Related to Expectations (TEs) Associated with the Rest of the Variables of the

Model

Motivation for travel (TE1)

Asymptotic

Tau-b of Approx. Approx. Valid

standard

Kendall tb sig. Cases

errora

Activity carried out in the tourist desti-

–0.385 0.013 –28,116 0.000 6,108

nation (TE2).

Age of visitors (SEC1). 0.256 0.010 24,433 0.000 6,108

Declared daily expenditure (SEC2). 0.308 0.010 28,800 0.000 6,108

Nationality of visitors (SEC3). 0.230 0.011 17,731 0.000 6,108

Professionalism of the staff of establis-

0.100 0.012 8,241 0.000 5,979

hments (HM1).

Hospitality and friendliness of the ge-

0.092 0.130 7,312 0.000 5,947

neral population (HM2).

The tourist infrastructures (SM1). 0.088 0.012 7,308 0.000 5,924

The Natural Environment and the expla-

0.060 0.012 5,186 0.000 5,811

natory signage (SM2).

Signaling of access to the territory

0.025 0.011 2,172 0.030 5,983

(SM3).

Conservation of Historical-Artistic Heri-

0.064 0.012 5,255 0.000 5,893

tage (SM4).

Note: a. Assuming the alternative hypothesis. b. Using the typical asymptotic error based on the null hypothesis.

Source: Own elaboration based on the Annual Report of the Tourism Observatory of Extremadura (2019).

Reis. Rev.Esp.Investig.Sociol. ISSN-L: 0210-5233. N.º 175, July - September 2021, pp. 105-128Marcelo Sánchez-Oro, Rafael Robina-Ramírez, Antonio Portillo-Fernández and Héctor Valentín Jiménez-Naranjo 117

Model

which of them are dependent or indepen-

The second step in the empirical study of dent of others, since within the same model,

travelling motivation to establish an integra- variables that may be independent in one

ted model for the important variables in the relationship may be dependent in others

study of tourist motivation in inland areas (Escobero et al., 2016: 6).

was to establish a model of causal relation- The results and hypotheses of the pro-

ships between them. posed conceptual model were validated us-

Figure 2 below summarises this deduc- ing partial least squares (PLS) collected in

tive model. Structural equation modelling the structural equation models (SEM) based

establishes the dependence relationship on variance. SmartPLS 3.2.8 software was

between variables. It attempts to integrate used for this purpose (Ringle, Wende and

a series of linear equations and establish Becker, 2015).

FIGURE 2. Model of Tourist Motivations in Travellers

Source: Own elaboration.

Reis. Rev.Esp.Investig.Sociol. ISSN-L: 0210-5233. N.º 175, July - September 2021, pp. 105-128118 Tourist Expectations and Motivations in Visiting Rural Destinations. The Case of Extremadura (Spain)

Structural equation models (SEMs) are establish a comparison between the differen-

well suited to social science studies as well ces between the groups (Ringle, Wende and

as in the areas of economics and organi- Becker, 2015). A more detailed assessment

sational management (Fornell and Book- of the sample size and its validity using PLS-

stein, 1982). This methodology is particu- SEM established the “effect size” for each

larly useful to analyse the causal behaviour regression from the Cohen tables (2013). The

between dependent and independent rela- tables devised by Chin and Newsted (1999)

tionships. and Green (1991) were also consulted.

Structural equations allow several multi- The measurement model and the structural

variable techniques to be used, such as mul- model were the starting point for the definition

tiple regression and factor analysis (Kahn, of results. First, the validity and reliability of

2006). In this case the PLS technique was the measurement model was analysed. A pro-

chosen because it was the best suited to pre- cedure was therefore developed for the study

dict and study relatively recent phenomena of reflective element measurement models as

(Chin and Newsted, 1999; Robina-Ramírez, shown in Table 7 (Hair et al., 2016).

Fernández-Portillo and Díaz-Casero, 2019; Reliability was studied through the exami-

Hair et al., 2019). nation of individual loads or simple correla-

tions of the measurements with their respec-

Outer model tive latent variables (≥ 0.7 was accepted).

Subsequently, Cronbach’s alpha coefficient

The load factor was > 0.7 for all the indica- was analysed, which was taken as the relia-

tors. A PLS analysis was then carried out to bility index of the latent variables.

TABLE 7. Reliability, Validity of the Constructs and Fornell-Larcker Criteria

Fornell-Larcker Criterion

Alfa de

Constructs rho_A CR AVE

Cronbach

TE HM SM SEC

HM 0.725 0.733 0.879 0.783 0.885

SM 0.766 0.824 0.847 0.584 0.475 0.764

SEC 1 0.139 0.153

TE 1 0.089 0.078 0.488

Note: rho_A = Dijkstra-Henseler Rho_A; CR = Composite Reliability, AVE = Average Variance Extracted, TE = Tourist Ex-

pectations, HM = Hosting Motivation, SM = Secondary Motivations, SEC = Socioeconomic Conditions.

Source: Own elaboration.

The convergent validity of the latent var- 2015), which explains its validity when the

iables was first evaluated by extracting the square root of the average value extracted

average variance in order to calculate com- (AVE) for each element was higher than

posite reliability (accepted > 0.5). For the the correlations with the other latent vari-

verification of the discriminant validity of the ables (Henseler, 2017). In this case, Table

latent variables, the Fornell-Larcker crite- 7 shows that the square root of the average

rion was used (Ringle, Wende and Becker, variance extracted for each construction

Reis. Rev.Esp.Investig.Sociol. ISSN-L: 0210-5233. N.º 175, July - September 2021, pp. 105-128Marcelo Sánchez-Oro, Rafael Robina-Ramírez, Antonio Portillo-Fernández and Héctor Valentín Jiménez-Naranjo 119

was greater than its greater correlation with each pair of factors. These were < 0.90

any other construction. (Gold, Malhotra and Segars, 2001; Hense-

ler, 2017).

TABLE 8. Heterotrait-Monotrait Ratio (HTMT)

Inner model

TE HM SM SEC

After examining the measurement model, the

TE relationships between the constructs were

analysed. The path coefficients of the hypo-

HM

theses were studied. Bootstrapping of 10,000

SM 0.645 subsamples was done to verify the statistical

SEC significance of each route. The explained va-

riance (R2) of the endogenous latent variables

Source: Own elaboration. and the p-value of the regression coefficients

(t-test) were used as indicators of the expla-

The studies by Henseler, Ringle and natory power of the model (Table 9). The re-

Sarstedt (2015) showed that a lack of dis- sults obtained allowed all the auxiliaries hypo-

criminant validity was better detected by theses to be accepted, except H5, because

means of another technique: the Heter- there were statistically significant differences

otrait-Monotrait (HTMT) relationship. Ta- in some of the relationships between variables

ble 8 explains the HTMT relationships for in our model (p-value < 0.05).

TABLE 9. Path Coefficients

Original T Statistics

Hipothesis Lower CI Higher CI p value (Sig.) Acepted

Sample (O) (|O/STDEV|)

H1: SEC → TE 0.486 53,649 0.472 0.501 0.000 Yes

H2: SEC → HM 0.139 11,864 0.120 0.158 0.000 Yes

H3: HM → TE 0.025 1,826 0.002 0.048 0.034 Yes

H4: SEC → SM 0.153 13,013 0.134 0.173 0.000 Yes

H5: SM → TE –0.008 0.591 –0.031 0.014 0.277 No

Source: Own elaboration.

Goodness of fit test for the model SRMR evaluates the general fit of a re-

search model in PLS, thus avoiding ob-

To perform the global adjustment of the

taining an erroneous specification of the

model, the mean squared residual indi-

model (Henseler, Hubona and Ray, 2016).

cator of the standardised root (SRMR)

was studied. Hu and Bentler (1998) defi- SRMR values that are lower than those are

ned SRMR as the average mean squared considered valid (Henseler, Hubona and

discrepancy between the correlations ob- Ray, 2016). In this study, the SRMR was

served and the implicit correlations in the 0.056 (< 0.08), which means that the model

model. fits the empirical data (Hair et al., 2016).

Reis. Rev.Esp.Investig.Sociol. ISSN-L: 0210-5233. N.º 175, July - September 2021, pp. 105-128120 Tourist Expectations and Motivations in Visiting Rural Destinations. The Case of Extremadura (Spain)

According to Chin and Newsted, (1999) TABLE 10. R2 and Q² Results

R2 values in any structural model may be

one of three different types: 0.67 “Sub- Construct Q2 R2 (%)

stantial”, 0.33 “Moderate” or 0.19 “Weak”.

TE 0.117 23.9%

Therefore, the evidence obtained shows

that this model was “Weak” when applied HM 0.014 1.9%

to “tourist expectations”. It is logical that SM 0.012 2.3%

the variables that are not endogenous do

not have a value of R2 (see Table 10). SEC

Source: Own elaboration.

FIGURE 3. Final Model of Tourist Motivations

TE1 TE2

181.349 8.667

TE

R 2 (23.9%)

H3 H5

T student T student 0.591

1.826 (pMarcelo Sánchez-Oro, Rafael Robina-Ramírez, Antonio Portillo-Fernández and Héctor Valentín Jiménez-Naranjo 121

To analyse the Blindfolded technique, study are provided for destinations with uni-

part of the data for a given construct has que characteristics. The main contribution

to be omitted during the estimation of the of the paper is that it introduces a means for

parameters, in order to estimate those that comparison that can be used in future stu-

were previously omitted from the estimated dies, as several scholars have pointed out

parameters (Chin and Newsted, 1999). In (Bitsani and Kavoura, 2014; Beh and Bru-

this way, the predictive relevance of the yere, 2007; Cervantes et al., 2000; Devesa,

model from the contributions of the Stone- Laguna and Palacios, 2010a; Hsu, Cai and

Geisser (Q²) test can be studied (Stone, Wong, 2007; Lee, Yoon and Lee, 2007; Se-

1974; Geisseir, 1974). vert et al., 2007).

In the case discussed here, it was According to Maslow’s hierarchy of

shown that the model has a predictive needs and several other studies (Pearce

capacity when all endogenous construc- and Caltabiano, 1983; Pearce, 1988, 1994),

tions met the Q2 > 0 requirement. The Q2 research on reasons for travelling and tour-

values of 0.02, 0.15 and 0.35, Henseler, ist experiences has addressed causal re-

Ringle and Sarstedt (2015), indicated that lationships with variables such as satis-

the Predictive relevance could be small, faction and socioeconomic characteristics.

medium and high. Therefore, another im- The primary source of data was a number

portant result can be deduced; the TE and of surveys on tourists visiting Extremadura,

SM constructs will have predictive rele-

a Spanish semi-depopulated inland region.

vance, since the values of Q2 are greater

The descriptive analysis mainly provides the

than 0.02. However, TE will be of little rele-

reasons resulting from forming a majority of

vance, with a very high value of Q2 (0.117)

level 4 in Maslow’s scale of needs; in other

(see Figure 3).

words, they are essentially reasons linked to

The final model resulting from the empiri- personal development and self-esteem (cul-

cal study is shown in Figure 3. In this model, tural visits to explore historical-artistic herit-

hypothesis 3 was accepted if the results age sites). This analysis is in line with Swar-

showed a level of significance over 95%. brooke and Horner (2002), who identified

Hypotheses 1, 2 and 4 were accepted with different types of tourist products and des-

a level of significance over 99%; in contrast, tinations. This can cause variations in tour-

hypothesis 5, is rejected because it is not ists’ motivations.

significant. This result can be very interest-

ing for future research. Hypotheses about causal relationships

were formulated by using a multivariate

analysis model based on the use of struc-

tural equation models. This resulted in four

Conclusions out of the five hypotheses being accepted

(H1, H2, H3 and H4). Causal relationships

This paper addresses the issue of tourist

have been underlined in previous studies

motivation for a specific niche market, and

analyses some of the reasons that tourists (Baloglu and McCleary 1999; Devesa, La-

give for visiting a particular destination. The guna and Palacios, 2010a,b; Bojollo, Pé-

objectives set are in line with those of other rez and Muñoz, 2015; Caballero Domínguez

studies that have analysed motivation in 2006; and Shmueli and Koppius 2011).

tourism (Araújo and Sevilha, 2017; Pearce, Regarding H1, the structural model in-

1988, 1994; Pearce and Caltabiano, 1983; dicated that the socioeconomic conditions

Moscardo and Pearce, 1986). According (SECs) was the variable that best explained

to Castaño et al. (2005), the results of the the motivation (TE), mainly in relation to the

Reis. Rev.Esp.Investig.Sociol. ISSN-L: 0210-5233. N.º 175, July - September 2021, pp. 105-128122 Tourist Expectations and Motivations in Visiting Rural Destinations. The Case of Extremadura (Spain)

reasons for travelling to the region (TE1). This In summary, it was found that the vari-

relationship was found to be less important ables that explained the reasons for making

for the activities carried out (TE2). The SECs a trip to the Extremadura Region are essen-

variable was formed by indicators that allow tially socioeconomic. An interesting line of

them to be ranked according by their weights, future research would be for this model of

which showed that daily spending (SEC2) was causal relationships to be applied to other

the most important indicator in the relation- social and geographical contexts, in order

ship between socioeconomic conditions and to verify whether the hierarchy of motiva-

motivation, followed by nationality (SEC3), tions and covariance in the model compo-

while age was found to be less important nents take different forms.

in this relationship (SEC1) (Swarbrooke and

Horner, 2002; Araujo and Sevilha, 2017).

The validation of this hypothesis identi-

fies daily spending as one of the most im-

Bibliography

portant factors in the reasons linked to per-

Araújo Pereira, Gisele and Sevilha Gosling, Mar-

sonal development and self-esteem that

lusa de (2017). “Los viajeros y sus motivacio-

made tourists choose this particular desti- nes. Un estudio exploratorio sobre quienes

nation. This information is important for the aman viajar”. Estudios y Perspectivas en Tu-

decision making of those responsible for rismo, 62-85.

tourism in the region, and others that share Baloglu, Seyhmus and Mccleary, Ken W. (1999). “A

similar characteristics. Model of Destination Formation”. Annals of Tour-

ism Research, 26(4): 868-897.

The causal relationship was supported

by the literature; in addition, the association Beh, Adam and Bruyere, Brett (2007). “Segmenta-

tion by Visitor Motivation in Three Kenyan Na-

between the variables was verified in the

tional Reserves”. Tourism Management, 28(6):

descriptive analysis, which showed that the 1464-1471.

socioeconomic profile of visitors was the

Beltrán-Bueno, Miguel Á. and Parra-Meroño, Ma-

variable most closely associated with the ría C. (2017). “Perfiles turísticos en función de

motivations reported by respondents. las motivaciones para viajar”. Cuadernos de Tu-

Hypotheses H2 and H4 established a rismo, 39: 41-65.

somewhat weaker causal relationship, but Bitsani, Evgenia and Kavoura, Androniki (2014).

also with strong significance. It was found “Host Perceptions of Rural Tour Marketing to

Sustainable Tourism in Central Eastern Europe.

that socioeconomic conditions (SECs) were

The Case Study of Istria, Croatia”. Procedia-So-

more strongly related to secondary motiva- cial and Behavioral Sciences, 148: 362-369.

tions (SMs), namely, satisfaction with tan-

Bojollo Roca, María; Pérez Gálvez, Jesús C. and

gible aspects of tourism resources in the Muñoz Fernández, Guzmán A. (2015). “Análisis

region, than to the different aspects of sat- del perfil y de la motivación del turista cultural

isfaction with the tourist experience (HM), extranjero que visita la ciudad de Córdoba (Es-

namely, intangible aspects. paña)”. International Journal of Scientific Man-

agement and Tourism, 3: 127-147.

H3 established links between satis-

Byrd, Erick (2007). “Stakeholders in Sustainable

faction with the tourist experience (HM)

Tourism Development and their Roles: Applying

and the reasons for the trip (TE), but it was

Stakeholder Theory to Sustainable Tourism De-

found to have a weaker causal relationship. velopment”. Tourism Review, 62(2): 6-13.

However, no causal relationship was found Caballero Domínguez, Antonio J. (2006). “SEM vs.

between satisfaction with the tourist experi- PLS: un enfoque basado en la práctica”. IV Con-

ence (SM) and tourist motivation (TE), which greso de Metodologías de Encuestas. Pamplona,

led to the rejection of H5. 20, 21 and 22 September of 2006.

Reis. Rev.Esp.Investig.Sociol. ISSN-L: 0210-5233. N.º 175, July - September 2021, pp. 105-128Marcelo Sánchez-Oro, Rafael Robina-Ramírez, Antonio Portillo-Fernández and Héctor Valentín Jiménez-Naranjo 123

Castaño, José M. (2005). Psicología social de los Fornell, Claes and Bookstein, Fred (1982). “Two

viajes y del turismo. Madrid: Thomson. Structural Equation Models: LISREL and PLS

Chen, Donal (2011). Conversation between a Tech- Applied to Consumer Exit-Voice Theory”. Journal

nological Master and a Zen Master. Merit Times, Mark Research, 19(4): 440-452.

8th ed., April 17. García Ferrando, Manuel (2008). Socio-estadística.

Chen, Yong; Barry, Mak and McKercher, Bob (2011). Introducción a la estadística en sociología. Ma-

“What Drives People to Travel: Integrating the drid: Alianza Editorial.

Tourist Motivation Paradigms”. Journal of China Geisseir, Seymour (1974). “A Predictive Approach

Tourism Research, 7(2): 120-136. to the Random Effect Model”. Biometrika, 61(1):

Chin, Wynne and Newsted, Peter (1999). “Structural 101-107.

Equation Modeling Analysis with Small Samples Gold, Andrew H.; Malhotra, Arvind and Segars, Al-

Using Partial Least Squares”. In: Hoyle, R. H. bert H. (2001). “Knowledge Management: An

(ed.). Statistical Strategies for Small Sample Re- Organizational Capabilities Perspective”. Jour-

search. Thousand Oaks, California: SAGE Publi- nal of Management Information Systems, 18(1):

cations, pp. 307-341. 185-214.

Coghlan, Alexandra and Pearce, Philip (2010). Gómez-Jacinto, Luis; San Martín-García, Jesús and

“Tracking Affective Components of Satisfac- Bertiche-Haud’Huyze, Carla (1999). “A Model of

tion”. Tourism and Hospitality Research, 10(1): Tourism Experience and Attitude Change”. An-

42-58. nals of Tourism Research, 26(4): 1024-1027.

Cohen, Jacob (2013). Statistical Power Analysis for González-Herrera, Manuel R. and Álvarez-Hernán-

the Behavioral Sciences. New york: Routledge. dez, Julián A. (2014). “Diagnóstico participativo

Cossens, John J. (1989). Positions a Tourist Desti- del turismo en Ciudad Juárez desde las voces

nation: Queenstown-A Brabded Destination? Un- de los actores locales”. Revista Iberoamericana

published dissertation. New Zealand: University de Ciencias, 1(2): 117-134.

of Otago, pp. 1022-1024. Green, Samuel B. (1991). “How Many Subjects Does

Crompton, John (1979). “Motivations of Pleasure It Take To Do A Regression Analysis”. Multivari-

Vacations”. Annals of Tourism Research, 6(4): ate Behavioral Research, 26(3): 499-510.

408-424. Grönroos, Christian (1978). “A Service Oriented

Csikszentmihalyi, Mihaly and Coffey, John (2016). Approach to Marketing of Services”. European

“Why Do We Travel? A Positive Psychological Journal of Marketing, 12(3): 588-601.

Model for Travel Motivation”. Journal of Travel Guaita Martínez, José M.; Martín Martín, José M.; Sali-

Research, 52(6): 709-719. nas Fernández, José A. and Mogorrón-Guerrero,

Devesa, María; Laguna, Marta and Palacios, An- Helena (2019). “An Analysis of the Stability of Ru-

drés (2010a). “Motivación, satisfacción y lealtad ral Tourism as a Desired Condition for Sustaina-

en el turismo: el caso de un destino de interior”. ble Tourism”. Journal of Business Research, 100:

Revista Electrónica de Motivación y Emoción, 165-174.

35-36: 169-191. Hair, Joseph; Hult, Tomas G.; Ringle, Christian and

Devesa, María; Laguna, Marta and Palacios, Andrés Sarstedt, Marko (2016). A Primer on Partial Least

(2010b). “The Role of Motivation in Visitor Sat- Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-

isfaction: Empirical Evidence in Rural Tourism”. SEM). London: Sage Publications.

Tourism Management, 31: 547-552. Hair, Joseph; Hult, Tomas G.; Ringle, Christian;

Escobero Portillo, María T.; Hernández Gómez, Je- Sarstedt, Marko; Castillo Apraiz, Julen; Cepeda

sús A.; Estebané Ortega, Virginia and Martínez Carrión, Gabriel A. and Roldán, José L. (2019).

Moreno, Guillermina (2016). “Modelos de Ecua- Manual de Partial Least Squares Structural

ciones Estructurales: Características, Fases, Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM). OmniaScience.

Construcción, Aplicación y Resultados”. Ciencia (2nd ed.). Available at: https://doi.org/10.3926/

y Trabajo, 55(18): 16-22. oss.37

Filep, Sebastian and Greenacre, Luke (2007). “Eval- Hall, C. Michael; Voigt, Cornelia; Brown, Graham

uating and Extending the Travel Career Patterns and Howat, Gary (2011). “Wellness Tourists:

Model”. International Interdisciplinary Journal, In Search of Transformation”. Tourism Review,

55(1): 23-38. 66(1/2): 16-30.

Reis. Rev.Esp.Investig.Sociol. ISSN-L: 0210-5233. N.º 175, July - September 2021, pp. 105-128You can also read