SCALING UP SOLUTIONS FOR A DESERT IN DISTRESS - Tucson Audubon Society

←

→

Page content transcription

If your browser does not render page correctly, please read the page content below

CONTENTS

T U C S O N A U D U B O N .O R G

Fall 2020 | Vol 65 No 4

02 Southeast Arizona Almanac of Birds, October Through December

MISSION 04 How Did You Connect with Birds and Tucson Audubon in 2020?

Tucson Audubon inspires people to enjoy and protect birds

through recreation, education, conservation, and restoration

06 Fire on the Mountain… and in the Desert

of the environment upon which we all depend. 08 Scaling Up Solutions for a Desert in Distress

TUCSON AUDUBON SOCIET Y 10 The Bighorn Megafire: A New Normal?

300 E University Blvd. #120, Tucson, AZ 85705

tel 520-629-0510 · fax 520-232-5477

12 Migratory Birds Need Wildfire, But Beware Too Much of a Good Thing

14 A Second Chance for the Saguaro-Palo Verde Forests of the Santa Catalinas

BOARD OF DIRECTORS

Mary Walker, President 16 The Linked Fates of Saguaros and Desert Birds

Kimberlyn Drew, Vice President

Tricia Gerrodette, Secretary

17 Bigger Picture: Brown-crested Flycatcher

Cynthia VerDuin, Treasurer 18 Conservation in Action

Colleen Cacy, Richard Carlson, Laurens Halsey, Bob Hernbrode, 20 Paton Center for Hummingbirds

Keith Kamper. Linda McNulty, Cynthia Pruett, Deb Vath

22 Next Gen Birders: Your Mentorship and the Future

S TA F F

Emanuel Arnautovic, Invasive Plant Strike Team Crew

24 Habitat at Home Plant Profile: Gray Thorn

Keith Ashley, Development Director 25 Birds & Community

Howard Buchanan, Sonoita Creek Watershed Specialist

Marci Caballero-Reynolds, In-house Strike Team Lead 26 Southeast Arizona Birding Festival

Gregory Decker, In-house Strike Team Crew 27 Holiday Gift Guide

Tony Figueroa, Invasive Plant Program Manager

Matt Griffiths, Communications Coordinator 31 Birds Benefit Business Alliance

Kari Hackney, Restoration Project Manager 33 Woo Hoot!

Debbie Honan, Retail Manager

Jonathan Horst, Director of Conservation & Research 33 The Final Chirp

Alex Lacure, In-house Strike Team Crew

Rodd Lancaster, Field Crew Supervisor

Dan Lehman, Field Crew

Kim Lopez, Finance & Operations Director

Matthew Lutheran, Restoration Program Manager

Jonathan E. Lutz, Executive Director

Keeley Lyons-Letts, Restoration Project Manager

Jennie MacFarland, Bird Conservation Biologist

Kim Matsushino, Habitat at Home Coordinator

Olya Phillips, Citizen Science Coordinator

Diana Rosenblum, Membership & Development Coordinator

Luke Safford, Southeast Arizona Birding Festival &

Volunteer Program Manager

Autumn Sharp, Communications & Development Manager

Karin Sharp, Bookkeeper

Roswitha Tausiani, Retail Assistant

Cody Walsh, In-house Strike Team Crew

Jaemin Wilson, Invasive Plant Strike Team Crew

N AT U R E S H O P S + N AT U R E C E N T E R S

Nature Shops: tucsonaudubon.org/nature-shop

Mason Center: tucsonaudubon.org/mason

Paton Center for Hummingbirds: tucsonaudubon.org/paton

V E R M I L I O N F LY C AT C H E R is published quarterly.

Call 520-629-0510 for address changes or subscription issues.

Vermilion Flycatcher Production Team

Matt Griffiths, Production Coordinator

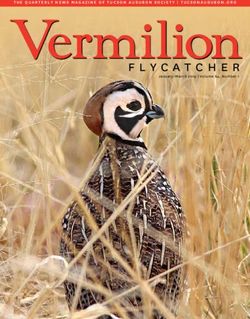

ON THE COVER

Autumn Sharp, Managing Editor Red-breasted Nuthatch by Brad James. Brad is a wildlife photographer from Newfoundland & Labrador, Canada. He

Keith Ashley, Editor-in-Chief hopes to inspire others to get out and enjoy the world around them through artistic images of wildlife that highlight the

Melina Lew, Design beauty of nature. See more of his work at bradjameswildlifephotography.com.

© 2020 Tucson Audubon Society; All photos © the photographer ABOVE: Gilded Flicker, Laura StaffordNOW THAT’S A GOOD IDEA!

INCLUSION, EQUIT Y, DIVERSIT Y, AND ACCESS

AT TUCSON AUDUBON

Nicole Gillett Kari Hackney Autumn Sharp

Conservation Advocate Restoration Project Manager Communications & Development Manager

ngillett@tucsonaudubon.org khackney@tucsonaudubon.org asharp@tucsonaudubon.org

A social justice revolution is taking place in the birding and conservation • A self-selected committee of three staff members from different

worlds. The experience of black birder, Christian Cooper, put the spotlight departments meets regularly to address IDEA concerns across

on a historically white-led conservation movement that does not reflect the the organization. The goal is to facilitate staff taking ownership of

diverse make-up of our nation. We feel it is our responsibility as members organization-wide implementation of IDEA principles and initiatives.

of a community-based bird conservation organization to act with greater • Birdability, the national movement to bring birding to mobility-challenged

intention in removing barriers and welcoming diversity. We must fight

individuals, has been engaged through a partnership with Arizona

until all of our Black, Indigenous, and People of Color (BIPOC) friends

Adaptive Sports and a volunteer-based assessment and documentation

and colleagues, the LGBTQ+ community, and all other marginalized

of accessibility for local birding hotspots.

and socially-oppressed individuals feel safe in their pursuits and in our

public spaces. We are meeting this demand with self-reflection, humility,

• Tucson-based Equity, Diversity, and Inclusion consultants, Ragland &

willingness to learn, and a passion for equity. Wilhite, have been hired to facilitate the best possible evolution of IDEA

principles and practices within the organization and our community of

We know that the crises facing birds are the same crises facing people— participants and supporters.

we cannot effectively address habitat loss and climate change without

addressing the issues of human injustice and inequity as a significant As an organization, we seek to reflect and serve our diverse Southeast

factor in each of these. Arizona community, and we are committed to educating ourselves about

what perpetuates systemic racism and all strains of social inequity within

A series of Tucson Audubon staff meetings held in July 2019 has culminated our own organization so that we can change. If you would like to know

in the organization-wide adoption of a new initiative: IDEA—systematically more about our newly formed IDEA committee or have any questions,

bringing Inclusion, Diversity, Equity, and Access considerations to our please email us at idea@tucsonaudubon.org.

organizational culture, programming, and goals. This year we’ve seen the

following developments:

CONSERVATION Over the years you have supported Tucson Audubon’s mission: inspiring people to enjoy and protect

the birds of Southeast Arizona. When you include us in your estate planning, you join many others

CAN BE as a member of our Vermilion Society—and you gain peace of mind, knowing that your values will

continue to become action on behalf of birds and their habitats, far into the future.

YOUR LEGACY There are many types of Planned Gifts to explore: gifts left by

bequest in a will or trust, charitable remainder trust, beneficiary

designations for your IRA, 401K, or life insurance.

We sometimes receive bequests from people whom we have never had

the opportunity to thank. If you include us in your estate plans, we

hope you will let us know. We value the opportunity to thank you, and

your gift can inspire others in their legacy planning.

For more information, please contact:

Vermilion Flycatcher, Lois Manowitz Keith Ashley, Development Director, 520-260-6994.SOUTHEAST ARIZONA

ALMANAC OF BIRDS

OCTOBER THROUGH DECEMBER

This year’s Bighorn Fire has caused a lot of us to wonder

about the effects of wildfires on the birds we love. While

we may fear worst case scenarios of birds unable to return

to the burned forests of Mt. Lemmon until they are fully

“recovered” many years from now, the reality is much more

encouraging. Many bark-foraging birds respond positively

to a mosaic of burn intensities, especially in the west where

wildfires are a natural part of the ecosystem. We may even

see the abundance of nuthatches, woodpeckers, and aerial

insectivores such as the Buff-breasted Flycatcher increase

in the years following major fires.

Matt Griffiths

Communications Coordinator

mgriffiths@tucsonaudubon.org

Northern Flicker, Mick Thompson

2 VERMILION FLYCATCHER | Fall 2020B I R D A L M A N AC

BUFF-BREASTED FLYCATCHER

The classic example of a bird species responding positively to wildfire in Southeast Arizona is the

Buff-breasted Flycatcher. This is the smallest and most easily identifiable Empidonax flycatcher in

the US, sporting a wonderful cinnamon color as opposed to the dull green of the other birds in the

genus. It is also one of the rarest—only a handful of pairs are found every year in pine-oak woodlands

of the mountain ranges in the region.

It is thought that the population of Buff-breasted Flycatchers was historically much larger, but was

diminished from the 1800s through the 1970s, possibly due to fire suppression and grazing practices.

More recently, and after some major fires in the region, their numbers have rebounded—it is now

relatively easy to find these birds in most of the Sky Island ranges. Wildfires may provide access

to understory vegetation making it easier for these flycatchers and other aerial foragers to move

through the habitat in search of food. After a low-intensity 1976 fire in Carr Canyon of the Huachuca

Mountains, the Buff-breasted Flycatcher population increased substantially over the next 7 years, and

other research suggests that they prefer forests that have been burned more frequently in the last 30

years. Will we find more flycatchers in the Santa Catalina Mountains soon? Time will tell!

RED-BREASTED NUTHATCH AND BROWN CREEPER

Nuthatches are weak cavity excavators and need soft and decayed wood to create their nest holes,

while creepers nest almost exclusively in the bark crevices of dead trees. Populations of Red-breasted

Nuthatch and Brown Creeper are most abundant in diverse forests of old growth trees mixed with

standing dead trees, like those created by wildfires. In the Pacific Northwest, creepers responded

positively to severe post-fire forests and were the dominant breeding bird the first three years after

the fire. Dead trees also attract the insects that both species forage for, and they should be left

standing to be utilized by a number of bird species. Red-breasted Nuthatch is unique among North

American nuthatches in that it regularly undertakes irruptive winter migrations in search of food—this

occurred in Tucson in 2017. Depending on the resources available on Mt. Lemmon this winter, will

the fire cause another large movement of this beautiful forest species into urban Tucson?

WOODPECKERS

The Black-backed Woodpecker of northern boreal forests and the American Three-toed Woodpecker

that inhabits parts of northern Arizona are both well known for their dependence on frequently burned

landscapes. These species actually thrive in areas that have experienced severe stand-replacing fires

because they feed on the bark- and wood-boring beetles that colonize the dead trees of burned forest.

Fire suppression and salvage logging have been shown to be detrimental to the habitat available for

these species.

Closer to home, these aspects of fire and forest management affect local species such as the

Hairy Woodpecker and Northern Flicker. Hairy Woodpeckers rely on dead trees and insects to a

lesser extent but may still benefit from locally abundant insect outbreaks resulting from natural

disturbances such as wildfires. Northern Flickers feed mainly on ants in the soil and rarely forage on

tree trunks and branches. They tend to forage along forest edges and prefer bare ground and short

grass when searching for ants. Frequent fires can help facilitate these habitat characteristics, and

Northern Flickers in Southeast Arizona forests have reacted positively to areas that have burned in

the last three years.

Buff-breasted Flycatcher, Matthew Studebaker; Brown

Creeper, Greg Lavaty; Hairy Woodpecker, Mick Thompson

VERMILION FLYCATCHER | Fall 2020 3M E M B ER S H I P T E S T I M O N I A L S

HOW DID YOU CONNECT

WITH BIRDS AND TUCSON

AUDUBON IN 2020?

BETH ACREE

I participated in the Tucson Bird Count for the first time this year. I was hesitant at first, concerned that my skills

weren’t good enough. However, the program is very well organized and gives you all the information you need. I

learned a lot through this experience and will do it again! I appreciated getting to be a part of a citizen-science

program that is helping to sustain a diverse bird community.

I also joined in the Birdathon fundraiser this year. Since we couldn’t participate in groups due to COVID, I counted

the birds in my neighborhood for a month when I was out walking. One day when I was birding at Rio Vista

Natural Resource Park, I stopped and realized a couple of hours had passed. I had been totally immersed in my

exploration and received two hours of respite from the weariness of sheltering in place.

The online classes and social events have also been a beacon for me during the pandemic. I’ve learned a lot and

have enjoyed having the continued community with my fellow bird watchers. I’m very grateful to Tucson Audubon

for all the effort that they have put into developing such creative and informative programs.

Participating in programs and field trips are very enjoyable, but it is also so satisfying to see birds in your own

backyard. I was treated to some Vermilion Flycatchers in the neighborhood this spring breeding season. Every

morning I got to see and hear the male out hunting for food as he fluttered over my backyard.

HOLLIE MANSFIELD

We moved to Tucson in August 2016 and joined Tucson Audubon the next year to learn about birds. I was in awe

of the number of birds all around, and since I wasn’t a birder, I could only identify a few common birds that I knew

from growing up in Illinois. After joining Tucson Audubon, I bought a pair of binoculars and signed up for every

field trip that I could attend. I decided to be a volunteer for the festival that summer because I wanted a way to

give back for the awesome education I had received on the free field trips. Joining Tucson Audubon has been the

best decision I have made since moving to Tucson.

This year I had booked trips to Panama and to the Spring Chirp festival

in Texas and was hoping to do several weekend trips with Tucson

Audubon. Of course, all those trips were rescheduled or cancelled,

and I have mainly birded at home, in neighborhood parks or close by at

Madera Canyon or Canoa Ranch. I have added several new feeders to

my yard and have planted lots of pollinator and native plants in my yard

to attract more birds and butterflies.

I took the opportunity of being at home more to learn a new hobby that

has also helped me become a better birder, nature journaling. I have

found myself journaling about the erratic flight patterns of the Lesser

Nighthawks in my backyard and drawn comics about the silly things

doves and other birds do on my feeders in my front yard.

Nature journaling a Lucifer Hummingbird by Hollie Mansfield

4 VERMILION FLYCATCHER | Fall 2020M E M B ER S H I P T E S T I M O N I A L S

SHARON FREEMAN-DOBSON

I joined Tucson Audubon in October of 2013 because it is a diverse group concerned with birds, and that

essentially means the environment in Arizona. I connect with birds in my environment every day from the feeders

in my backyard to taking a bike ride along the Canada del Oro Wash. I would say I have watched more bird cams

this year than ever before. I find them soothing. Birds give me hope that things are continuing and will be okay—

they live on and so will we. With all the uncertainties during the pandemic, birds are a stable, good thing.

Hooded Oriole, Martin Molina

MARY AND DAVID DUNHAM

We have been coming to southern Arizona to bird for over thirty years and connected with Tucson Audubon

shortly after purchasing our home here in 2008. We have loved the online classes, particularly, “Birding the

Calendar for June, July, and August” since we are snowbirds and normally not in Arizona those months. It has

been great to see all the nesting activities this summer.

What we appreciate the most about Tucson Audubon is its extensive conservation work. We have been involved

in the Lucy’s Warbler nestbox program since its inception and have found that to be particularly rewarding.

DAN WEISZ

I enjoy being a member of Tucson Audubon for the educational opportunities, the birding trips offered, and

being a part of the local birding community. 2020 changed much of my birding life. Zoom birding groups

replaced in-person lectures and classes; group birding trips became a thing of the past, and I went birding

alone more often than I ever did. In fact, because my calendar was remarkably empty I actually ended up going

birding more often than I would have otherwise. I also spent more time repeatedly birding and photographing

birds from the same locations. Birding in 2020 has brought me peace and calm during an otherwise very

different year.

“A friend of a friend let me know about a nesting Lesser

Nighthawk just outside their backyard wall. It was a

fascinating opportunity to observe the nighthawk and

her chick from the “blind” of the wall. The chick would

open its mouth wide every evening well after sunset as

a signal to the parent that it needed to be fed. Once the

chick did this, the mother would fly off within a minute.

This was also accompanied by the chick’s nibbling at

the parent’s beak. These birds have big mouths!”

—Dan Weisz

VERMILION FLYCATCHER | Fall 2020 5On many days late this summer the sun rose a beautiful but eerie orange-pink. It stayed that way for

hours. Wildfires are on everyone’s minds right now. From the massive local fires early this summer, Jonathan Horst

to the numerous megafires along the west coast, the reality of wildfire is inescapable. It’s a friend—it Director of Conservation & Research

jhorst@tucsonaudubon.org

maintains the habitat patchwork that numerous species require. And it’s a foe—at the wrong scale or

in the wrong place it can cause ecosystem collapse.

Many of Southeast Arizona’s premier birding areas, and some of the The impacts above result from unnaturally intense fires burning in areas

region’s most important habitat, have burned in recent history: the where fire normally occurs and maintains ecosystem balance. Fueled by

South Fork of Cave Creek and Rustler Park (Chiricahuas), Mt. Graham fire-adapted invasive plants, especially grasses, fires now spread into

(Pinaleños), Gardner Canyon and the springs along it (Santa Ritas), and the Sonoran and Mojave Desert uplands, habitat types not meant to

this year, a huge portion of the Santa Catalinas... again. burn, and where long-term impacts to birds can escalate quickly. The

buffelgrass-fueled Mercer Fire in the Santa Catalinas last year and last

Indirect impacts downstream of burns can be just as damaging. The month’s brome-fueled Dome Fire in Joshua Tree National Park were

incinerated roots of burned vegetation no longer lock the soil in place. clarion calls to the region.

The next thunderstorm then sweeps massive amounts of sediment

into drainages. This causes two problems: First, our mountain tops and In the pages that follow, regional experts weigh in on the positive and

foothills are normally the region’s sponges, absorbing and then releasing negative aspects of fire, discuss where it does and does not belong, and

rainfall slowly through time which creates the amazing habitat along our describe specific impacts on birds. We hope their words both instill the

mountain streams. When the mountains aren’t absorbent, more intense gravity of the situation and inspire insight regarding the way forward to

downstream flows and increased flooding result. Second, the sediment protecting the integrity of our regional ecosystems.

that accumulates in our managed lowland rivers has to be removed to

maintain human safety against flooding. The sediment removal process

LEFT: The Bighorn Fire rips through the lower slopes of the Santa Catalina Mountains, James

unfortunately takes with it the rare and high-value lowland riparian habitat

Capo; ABOVE: The aftermath of the 2019 Mercer Fire that was fueled by invasive buffelgrass,

that develops in these areas. courtesy Arizona-Sonora Desert Museum

VERMILION FLYCATCHER | Fall 2020 7F I R E O N T H E M O U N TA I N …

SCALING UP SOLUTIONS

FOR A DESERT IN DISTRESS

Since its founding, Tucson Audubon has fought to protect the desert and Sky Island mountains and the species that depend on these unique habitats.

We’ve controlled erosion, replanted native plants, and restored habitat. We’ve educated, advocated, and litigated. We’ve researched, mitigated impacts,

and innovated new strategies. All to help birds and other wildlife cope with a rapidly changing environment.

But now we’re taking our conservation efforts to a whole new level.

For the desert, a year of prevention is worth 200 years of saguaro-maturing cure. Controlling fire-adapted invasive plants may be the most effective tool to

prevent catastrophic, long-term losses to many of our most threatened and unique birds that rely on healthy desert habitat and saguaro cactus for nesting.

INVASIVE PLANT STRIKE TEAMS EL CORAZÓN SIN FUEGO

Tucson Audubon is proud to announce a new invasive plant program and The confluence of the Rillito River and Cañada del Oro Wash with the

the inauguration of two invasive plant strike teams in 2020. In February we Santa Cruz River is the heart of the lower Santa Cruz, and is an area

launched our federal-lands team as a collaborative effort with the National of particular local concern for hazardous fuels and urban fire—as well

Park Service, Fish & Wildlife Service, and Saguaro National Park. The as an area with significant unmet habitat potential. Perennial effluent

Collaborative Audubon Inventory and Treatment Squad (CoATIS) focuses flow upstream has increased vegetation in the river channel and has

on the highest-priority lands at wildlife refuges, national monuments, and led to a 27-acre patch of highly flammable salt cedar surrounding what

Saguaro National Park. Their specialty is Early Detection-Rapid Response, was formerly a major birding hotspot. The whole system is a fire waiting

identifying and addressing the leading edge of plant invasions while to happen, with the potential to spread fire up each of the connected

eradication and complete control in an area are still achievable goals. Their waterways and into adjoining infrastructure.

work extends throughout Arizona and New Mexico, often living on-site in

remote areas for extended periods of time to get the job done. With partners Pima County Flood Control and the Northwest Fire District,

we submitted a successful proposal to Arizona State Forestry to perform

At the beginning of September we launched our second strike team. Our a pre-emptive strike to prevent fires from occurring in this urban area by

In-house Strike Team will work, on contract, with local municipalities, removing potentially hazardous fuels from the landscape. The project

HOAs, federal agencies, conservation organizations, and local landowners will create 13 fire breaks along 4.2 miles of the channel and remove

with a primary focus on ecologically high-value areas. They’re currently the salt cedar patch. These actions will improve firefighting access and

treating buffelgrass to protect saguaros in Tucson Mountain Park for Pima reduce connectivity limiting fire’s ability to spread. Each group added

County and on Ironwood Forest National Monument for the Arizona Native their relevant expertise to the proposal and has been active in ongoing

Plant Society. SaddleBrook2 HOA has recently contracted us to create an discussions of river and floodplain management resulting in a reconciliation

invasive plant management plan and rid their HOA of buffelgrass. ecology-driven plan that achieves significant human safety goals while

maintaining biodiversity.

We have effectively treated invasive plants on our own lands and

projects for years, from Simpson Farm to Esperero Canyon to the Cuckoo Invasive plant removal is often the first step in ecosystem restoration

Corridor at the Paton Center, but Tucson Audubon is now elevating its projects; this project is no different. While fully worthwhile as a standalone

efforts to a regional scale and is fully licensed to control invasive plants effort, this project also paves the way for a suite of future large scale

on a contractual basis throughout Southeast Arizona—the only local riparian restoration projects at the site as envisioned by many partners and

conservation organization able to do so. led by Pima County Flood Control.

8 VERMILION FLYCATCHER | Fall 2020A N D I N T H E D E S ER T

INVASIVE SPECIES MAPPING IN SABINO AND BEAR CANYONS

Before being able to effectively control invasive plants on the landscape Tucson Audubon is also helping to standardize the regional protocol for

scale, one must know where and how pervasive they are in relation to mapping invasive plants. While there are countless ways to achieve and

priority habitat areas. High-quality spatial data make possible the strategic record the desired data, we opt to use the same system as our partners

decision-making necessitated by limited resources. Late this summer, in the Sonoran Desert Network of the National Park Service. This ensures

the National Forest Foundation awarded Tucson Audubon a contract that data we collect for the Forest Service can be used for decision making

to inventory and map invasive plants occurring on 1888 acres of Sabino and across agencies, especially as Saguaro National Park is next door. We

Bear Canyons in the Catalina Mountains on the Coronado National Forest. use the same process and data format for private parcels we map and

Four invasive grasses are the highest priority targets: buffelgrass, fountain are actively encouraging additional partners to adopt the same system

grass, natal grass, and giant reed. However, our crew is also on the lookout for a landscape scale understanding of the invasive plant problem and

for 16 other invasive plant species likely to occur in the two canyons, and treatment efforts underway.

identifiable during the project window, and will be mapping them all.

Inventorying such a large area is a daunting task, especially when the goal

is to pinpoint all occurrences to guide future treatment. On areas that can

Tucson Audubon is and will remain on the cutting edge, taking

be physically traversed safely, our crew works as a team systematically

surveying the area search and rescue style. For cliff sides and areas too steep

concrete and innovative steps to create a better future for

to walk, we use spotting scopes to survey areas block by block. We record birds and people in Southeast Arizona on all fronts: research,

precise, geospatial data every step of the way directly into our GIS system advocacy, and implementation.

where the results can be analysed and shared readily by all project partners.

Fire burning through a 25-acre stand of buffelgrass and saguaro cactus in the front range of the Santa Catalinas during the Scoping and mapping invasive plants in Sabino Canyon, Keeley Lyons-

Mercer Fire, August 22, 2019; courtesy of David Rankin Letts; The CoATIS on assignment in Grand Canyon National Park

VERMILION FLYCATCHER | Fall 2020 9F I R E O N T H E M O U N TA I N …

THE BIGHORN

MEGAFIRE:

A NEW NORMAL?

The Bighorn Fire explodes on the upper slopes of the Santa Catalina Mountains, courtesy InciWeb

On the evening of June 5, 2020, lightning struck multiple locations in the frequent fire from southwest conifer forests in the 20th century, and

Santa Catalina Mountains, as it has for thousands of years. One of these forests grew more dense. Hot, dry weather pushes extreme fire behavior,

strikes, near Pima Canyon, ignited dry fuels—grasses, small shrubs, as has and combined with dense fuels, megafires result.

also happened for thousands of years. The weather was unusually hot, dry

and windy, and fire began to spread. A spreading fire is a chain reaction, Much of what burned during the early days of the Bighorn Fire were

where one patch of burning fuel initiates the combustion reaction in desert grassland, Madrean oak grasslands and woodlands, and interior

adjacent fuels. The transfer of heat to unburned fuels is facilitated by wind chaparral—vegetation types that are thought to be fire resilient. As the

and low humidity, and fires are strongly propelled upslope because the hot fire progressed, it moved into pine forest and mixed conifer forests at

gases and heat radiated by the fire strikes the upslope fuels and sets them higher elevations. Some of these old-growth stands are many hundreds

afire. In a matter of hours, the ignition that had started at a point on the of years old. Fire moves differently through these denser forests, because

landscape had turned into a flaming front in remote country. in addition to the fuels near the ground, fire can spread through the tree

canopy—a crown fire. While some conifers can withstand or recover from

Over the next month, the Bighorn Fire roamed, and sometimes raged, over crown fire, most cannot and mortality can be very high. An exception is our

nearly the entire extent of the Santa Catalina Mountains. For the first few unique Chihuahuan pine, which can resprout even after being top-killed,

days, the fire spread moderately, less than 1000 acres per day. But with but this is a rare adaptation among conifers.

extreme fire weather in rugged mountains full of combustible fuels, the

fire began to spread rapidly. On June 17, the fire nearly doubled in size, Even large fires like the Bighorn leave behind a complex mosaic of burn

burning more than 12,000 acres in a single day, followed by almost two severity, the term used to describe fire impacts on vegetation and soils

weeks averaging nearly 7,000 acres per day. By the time the fire was under (Figure 1). The areas of most concern are those that burn at high severity,

control, the Bighorn Fire had burned over almost the entire combined which means extensive soil damage, tree mortality, and high potential

perimeters of all the previous fires that have affected the Santa Catalinas for soil erosion. These areas are likely to remain impaired for years or

in 18 years. Megafires, like this one, burning entire mountain ranges in decades, meaning that they may take the longest to recover. In the past,

a single event are a phenomenon influenced by our management of the severely burned patches tended to be smaller, and could be reseeded by

forest. Grazing and fire suppression led to the near elimination of natural, trees in nearby stands that were less damaged.

10 VERMILION FLYCATCHER | Fall 2020A N D I N T H E D E S ER T

Figure 1. Bighorn Fire Severity. Prepared by Dr LA Marshall, University of Arizona. Bracken fern returning to severely burned areas of the Bighorn Fire, Don Falk

After a gigantic event like the Bighorn, what constitutes “recovery”, fire. These all fall into the second post-fire pathway, a switch from forest to

especially in an era of climate change? Dense, overgrown forests and shrub-dominated landscape. A final possibility is a switch to grass, should

extreme weather mean that severely burned patches can be much larger, conifers seedlings fail and root sprouters be absent. Though fire can burn a

leaving thousands of acres without trees. Conifer seeds tend to not travel mountain range in a matter of days to weeks, recovery along any pathway

far from their parent tree, and so recovery of the forest is difficult as shrubs happens on much longer time scales.

and grasses take over the open gaps. In our increasingly warm and dry

climate, it is unlikely the forest will go back to what it was at the beginning In the end, what lessons do we learn from the Bighorn Fire? Perhaps the

of the 2000s, before large fires burned over the mountains repeatedly. most important lesson will be the time that ecosystems need to recover,

particularly given the added stresses of climate change. Climate change

There are three major potential pathways the forest might take for is also making fire seasons longer and more intense, suggesting that there

recovery. Given the mosaic nature of fire, each of them might play out in may be more megafires in our future in other mountain ranges throughout

different areas on the mountains. The first is a return to conifer forest, the West. With megafires threatening to destroy ecosystems on a massive

but with a less dense structure and a more open and diverse understory, scale, we need to support the proper management of our public lands, and

supporting habitat for many different species. This outcome could be fight to slow down the pace of climate change every way that we can.

closer to what the forest looked like in the 1800s, when frequent low-

severity fire burned through the upper elevations every ten years or so—

the natural, adapted relationship with fire in southwestern pine forests.

The other options for recovery come into play in the large severely burned

patches, and elsewhere if the remaining trees fail to produce surviving

seedlings as can happen in drought. In mixed pine-oak woodland, oak

Professor Don Falk and Dr. Laura Marshall

will sprout from the roots and recover from severe fire faster than pines

School of Natural Resources, University of Arizona

can move back in, resulting in dense shrubfields of oak and ceanothus.

Aspen, another root sprouting species, will also come back quickly after

VERMILION FLYCATCHER | Fall 2020 11F I R E O N T H E M O U N TA I N …

MIGRATORY BIRDS NEE

BUT BEWARE TOO MUCH

The beautiful woodlands and forests blanketing the mountains increases in their severity and extent beyond what plants and animals have

surrounding Tucson provide increasingly critical and rare habitat to a adapted to over evolutionary time that is the problem. Wildfire effects on

diverse array of Neotropical migratory birds. Many of these species follow birds during their breeding season have been studied for decades, yet

forested corridors of the rugged mountain ranges spanning the length of there has been virtually no research of fire at stopover habitats during

the Central and Pacific Flyways from Oaxaca to Alaska. The Sky Islands migration. My work with Dr. Charles van Riper III of University of Arizona

of our Madrean Archipelago provide stepping-stones for migrating forest and the USGS Sonoran Desert Research Station on Mt. Lemmon and other

birds connecting Mexico’s Sierra Madre with the Rockies, Sierra Nevada, Madrean Sky Islands examines the use of burned woodland and forest

and other wooded mountains of the US—thousands of birds stopping just habitats by migrating songbirds during spring stopover.

to rest and refuel before they continue their journeys. Imagine, weighing

about as much as four pennies, a Black-throated Gray Warbler aptly While the Bighorn Fire may be foremost on our minds, Mt. Lemmon is

foraging among the flowering oaks of Madera Canyon may only be halfway no stranger to large, severe wildfires. In 2002 and 2003, the Bullock and

along its 2,000-kilometer voyage. Aspen fires burned roughly 100,000 acres of the Santa Catalina range.

Ten years later, I surveyed migratory songbirds in the recovering pine-oak

While the catastrophic fires of recent decades can be devastating for us to woodlands and mixed conifer forests there and in burned areas of the

witness, it is critical we recognize that wildfire is a natural, even essential Santa Rita and Huachuca Mountains, comparing areas with different burn

part of migratory bird habitats. Indeed, fire is perhaps the primary force of severities and fire ages. For part of our analysis, we categorized birds into

ecological disturbance shaping biodiversity and habitat mosaics from Mt. two groups or “guilds” based on their diet and foraging behavior. From

Lemmon to Mt. Rainier. The plants and animals, and the cultures of the all the birds we detected during surveys, we first separated the primarily

First Peoples of our continent’s west, evolved with wildfire and adapted insectivorous species. Next, we identified those species as either foliage-

to the environmental and habitat conditions it fosters. Even extremely gleaners, birds that primarily hunt by plucking their prey from plant

destructive, high severity fire is an essential part of natural wildfire surfaces (warblers, vireos, and kinglets), or aerial insectivores such as

dynamics. It is not the occurrence of wildfires, but rather the recent flycatchers, which mostly seize prey on the wing by flycatching.

The complex fire mosaic of the Huachuca Mountains looking north from the summit of Miller Peak, Jherime Kellermann Cordilleran Flycatcher, Tom Benson

12 VERMILION FLYCATCHER | Fall 2020A N D I N T H E D E S ER T

ED WILDFIRE,

H OF A GOOD THING

Foliage-gleaners were most abundant in more high severity burn areas phenology such as spring flowering like billboards advertising the best

within highest elevation montane conifer forest, while flycatchers were refueling stations. This means that birds like warblers and flycatchers may

more abundant in low and moderate severity burns of mid-elevation look for different “road signs”, since they eat prey at different phenological

oak-juniper woodlands. Among the most important prey items for foliage- stages (e.g. larvae vs adults). We have barely scratched the surface of

gleaning insectivores during migratory stopover are herbivorous larvae understanding the role wildfire plays in the complex ecology of Neotropical

and caterpillars, which can be more abundant in post-fire successional songbird migration.

habitats. Foraging success of warblers and other foliage-gleaners is closely

associated with fine-scale foliage structure, such as leaf petiole length, Rapid climate change, land use and development, and invasive species are

which affect birds’ ability to physically reach prey and may be associated all interacting to alter the wildfire regimes bird migration has adapted too.

with post-fire vegetation communities and structure. In contrast, We desperately need more research on the effects of wildfire on habitat

flycatchers primarily capture insects in-flight, requiring relatively open condition and selection at a wide range of spatial and temporal scales and

woodland understory. Current research by Dr. van Riper suggests that in across the awesome diversity of bird species and ecological communities

response to the Bighorn Fire, breeding Cordilleran Flycatchers packed into in the Sky Islands and throughout the western migratory flyways.

the remaining unburned habitat at twice the normal density, all had failed

nests, and may have departed for fall migration over two weeks early.

Wildfire may benefit migrating birds before they even land at a stopover

site by providing “road signs” of good rest stops to refuel. Wildfire can

Jherime L. Kellermann, PhD

affect the timing or phenology of plant flowering, budburst, and fruiting Associate Professor

which is seasonally driven by temperature and moisture. In turn, the Environmental Sciences Program Director

Natural Sciences Deptartment

emergence and growth of plant-eating insects has adapted to coincide

Oregon Institute of Technology

with plant phenology. Migrating birds could use visible differences in plant

Black-throated Gray Warbler, Matthew Studebaker March snowfall in 2010 on Mt. Wrightson within the 2005 Florida Fire in the Santa Rita Mountains,

Jherime Kellermann

VERMILION FLYCATCHER | Fall 2020 13F I R E O N T H E M O U N TA I N …

A SECOND CHANCE FOR

THE SAGUARO-PALO

VERDE FORESTS OF THE

SANTA CATALINAS

The Bighorn Fire brought sudden and drastic change to the Santa fire was uncommon in the Sonoran Desert, taking place on average

Catalinas. In a matter of weeks we lost untold acres of pine and mixed approximately once every 250 years. As a result, our desert plants are not

conifer forests. In the decades to come, some of the forest may return, adapted to fire. In contrast, buffelgrass thrives on fire. Fire removes the

some may instead become shrubland. dead biomass from previous years’ growth, which accumulates because,

here in the Sonoran Desert, nothing eats buffelgrass. The removal of this

In contrast to this rapid change that took place in our higher elevation dead biomass and the influx of nutrients after a fire, combined with a little

forest ecosystems, a slower change has been occurring over the rain, results in a lush, green field of buffelgrass.

course of the past three decades in the desert ecosystem at the base

of the mountains. On the southern front range of the Catalinas, below As a fire-prone invasive grass, buffelgrass made headlines during the

approximately 4,000 feet, lie our saguaro-palo verde forests. Here you’ll Bighorn Fire, but what role did it play in the fire? The answer to that

find a relative newcomer to the Catalinas, a plant native to the savannas of question requires getting on the ground to document the primary fuels of

Africa that has made itself at home in our desert: buffelgrass. the fire, something that colleagues and I hope to be able to do soon. What

we already know is that there is a lot of buffelgrass in the front range, but

Buffelgrass is a perennial—an individual plant may live ten or more years. it exists in discrete patches. Last year we saw what happens when one

Buffelgrass is present in the landscape all year long, and most of the of those patches ignites. On August 22, 2019 lightning struck a patch of

time it’s in a dormant state, extremely dry and extremely flammable.This buffelgrass just to the west of Soldier Canyon. The resulting fire, known

grass burns incredibly hot, 1,300–1,600 F versus 190–750 F, recorded as the Mercer Fire, burned through the entire 25-acre patch, burning out

in wildfires fueled by desert annual plants. Historically, even low intensity at the edge of the patch where it encountered drastically lower fuel loads

typical of the Sonoran Desert.

Colleagues and I have initiated a long-term study of the impacts of the

Mercer Fire. We’ve already seen that buffelgrass has re-sprouted from

its roots, but we want to know how our native plants will respond. How

many saguaros did we lose in the months immediately after the fire, and

how many more will we lose in the coming years? We will have to track

these saguaros for over a decade to find out the true cost of the fire to

the population. Our detailed study of the Mercer Fire will help us better

understand the impacts of the Bighorn Fire, in the areas where the fire

reached stands of buffelgrass.

If we overlay a map of buffelgrass in the front range with the Bighorn Fire

perimeter, we see that the fire reached only the higher elevation patches

Buffelgrass resprouted quickly after the Mercer Fire in the front range of the Santa Catalinas in

August 2019, courtesy Arizona-Sonora Desert Museum

14 VERMILION FLYCATCHER | Fall 2020A N D I N T H E D E S ER T

Six weeks after the Mercer Fire vegetation still showed fresh signs of being burned. It will take decades to determine the true cost to these saguaros, courtesy Arizona-Sonora Desert Museum

of buffelgrass, which tend to be smaller than lower elevation patches. Our attention is drawn to buffelgrass when a fire takes place, but even in the

Perhaps this is a result of the heroic efforts of our firefighters, or perhaps absence of fire, buffelgrass is transforming our desert. Diversity of native

the patchy distribution of buffelgrass in the front range limited the spread of plants goes down as the age of a buffelgrass patch increases. The stand

the fire. These are the types of questions we’d like to investigate in coming of buffelgrass that burned in the Mercer Fire had been growing for many

months. But regardless of the answers, we ought to view the Bighorn Fire years, and many native plant species had already declined or disappeared

as a wake-up call—next time we might not be so lucky. It’s safe to assume from the area as a result of competition with buffelgrass for space, water,

that buffelgrass patches will continue to expand through the front range, and nutrients. Fire simply speeds up this process of transformation, from a

coalescing into even larger patches, and increasing the chances of a major biodiverse desert to a depauperate buffelgrass grassland. Fortunately, we

disaster. Just last month in the Mojave National Preserve, a fire burned over have a second chance.

1.3 million Joshua trees, fueled in part by invasive grasses.

To learn more about buffelgrass and what you can do to help, visit

This doesn’t have to be the fate of our saguaro-palo-verde forests. The buffelgrass.org.

Tucson Mountains are a case in point. For the past twenty years a small

team of volunteers, the Sonoran Desert Weedwackers, led by Doug Siegel,

Pima County Natural Resources Specialist, has kept buffelgrass in check, Kim Franklin Ph.D.

protecting some of the densest stands of saguaros in the world. Starting Conservation Science Manager

Arizona-Sonora Desert Museum

fall 2020, they’ve hired Tucson Audubon’s new Invasive Species Strike

Team to increase the acreage covered.

VERMILION FLYCATCHER | Fall 2020 15F I R E O N T H E M O U N TA I N …

THE LINKED FATES

OF SAGUAROS AND

DESERT BIRDS

Jennie MacFarland,

Bird Conservation Biologist

jmacfarland@tucsonaudubon.org

Gila Woodpecker in saguaro nest cavity, Mick Thompson

Saguaro cacti are the iconic image of the Sonoran Desert, and synonymous all large saguaros are removed from an area, nest sites for cavity nesting

with southern Arizona in general. They are a keystone plant for the birds are virtually eliminated in that area, and won’t be available again for

ecosystem, a vital habitat component for many species of birds. A large an absolute minimum of 50 years (more likely 150 years). This would be

saguaro cactus will often have numerous holes created by either Gila acutely devastating for several birds that, in Arizona, nest exclusively in

Woodpeckers or Gilded Flickers for their nesting needs. These in turn saguaro cavities.

provide nesting opportunities for other species. Sometimes referred to as

a “saguaro hotel,” it’s relatively common to encounter several different Gilded Flickers are almost completely tied to the Sonoran Desert and

species of cavity nesting birds—Elf, Western Screech, and Cactus excavate their nesting cavities in large, mature saguaros. Data from the

Ferruginous Pygmy-Owls; Ash-throated and Brown-crested Flycatchers; Tucson Bird Count shows that fragmentation of their desert habitat causes

and American Kestrel—all using the same saguaro. In the Sonoran Desert, them to abandon even the largest saguaros within desert patches that are

the saguaro fills the role of trees in other communities, but with added too small. Unfortunately, large areas of desert habitat away from residences

insulation benefits. This is a vital nesting resource in a habitat with extreme are generally lower priority during firefighting efforts, leaving Gilded Flickers

high temperatures. even more vulnerable to the negative effects of catastrophic fires.

The Desert Purple Martin is a specialized subspecies that exclusively

nests in woodpecker cavities in saguaros and the similar cardon cactus

in Mexico. These birds time their migration to coincide their nesting with

the monsoon season, and favor large, very mature saguaros within lush

Sonoran Desert habitat. Tucson Audubon has begun a study on Desert

Purple Martins, and the first spatial analysis of these desert-adapted

birds has shown a preference, similar to Gilded Flickers, for large patches

of intact desert upland habitat.

Beyond the nesting opportunities they provide, saguaros are crucial to the

Sonoran Desert in other ways. The flowers are an important resource for

pollinators, including migratory nectar feeding bats, and the fruits provide

Purple Martin, Richard Fray food for many species. Even the buds exude nectar during the hottest driest

time of year. Buds, flowers, and fruits attract numerous insects, which in

Changing fire dynamics created by invasive grasses, such as buffelgrass, turn provide more food for birds and other wildlife. Preventing the long-

put saguaros and other cacti in danger. These species did not evolve with term loss of these keystone giants is the most effective, local conservation

regular fire, let alone the exceptionally hot temperatures that introduced measure for the approximately 14 bird species that primarily nest in

grasses produce when they burn. A catastrophic fire fueled by buffelgrass saguaros. Efforts to control the spread of invasive grasses, and protect

could kill most or all large saguaros within the burned area. Saguaros are desert habitats from fire, will positively contribute to conserving these

slow growers, taking upwards of 200 years to reach their full stature. If amazing cacti and the animals that rely on them for centuries to come.

16 VERMILION FLYCATCHER | Fall 2020B I G G ER P I C T U R E

B R O W N-C R E S T E D F LY C AT C H E R

(MYIARCHUS T YRANNULUS)

In this column we look at some of our Southeast Arizona borderlands specialty bird species. Birders from all over the US travel here to add birds to their

life lists, and we are proud of the birds that make our region unique! But how well do you know your local birds outside of the context of Southeast Arizona?

Here we take a broader look at some of our iconic species, and try to see how they fit into the larger birding landscape.

Brown-crested Flycatcher is one of my absolute This expansive range map makes the Brown-

favorite yard birds. I eagerly (but also a bit crested Flycatcher one of the most cosmopolitan

anxiously) await the return of this large flycatcher of all the 22 species in the genus Myiarchus,

each spring—it seems such a privilege to have which is among the largest genera in the Tyrant

this migratory species nesting in our urban Flycatcher family in terms of both body size and

neighborhood in Tucson. Throughout the desert number of species. Only the wide-ranging Dusky-

Southwest, Brown-crested Flycatchers are capped Flycatcher is found in more countries (19)

generally tied to watercourses with tall trees like than the Brown-crested (18). Brown-crested and

cottonwoods or oaks, but urban parks and yards Dusky-capped Flycatchers make up two of our

with lush vegetation must provide a suitable three Myiarchus species that nest in the Grand

analog to this riparian habitat. I’ve never found the Canyon State, with the desert-dwelling Ash-

nest of the pair that frequents our yard. It could be throated Flycatcher being the third. These three

in a saguaro cactus or perhaps a nearby nestbox, very similar species often cause identification

though they’ve never chosen our own backyard problems for birders here in Arizona, but if you

nestbox for a nesting attempt. think large-billed, yellow-bellied flycatchers

with crests are hard to keep straight, imagine

For me there’s a lot of mystique to the Brown- being confronted with ten similar species of

crested Flycatcher. For example, they arrive in Myiarchus while flipping through a field guide

Arizona in May and depart in August, but have you to Colombia! The taxonomic relationships of the

ever thought much about where they go for the many Myiarchus flycatchers have not been fully

other eight months of the year? We can presume analyzed with modern DNA sequencing, but the

most of them spend the winter somewhere in Brown-crested’s closest relative may actually be

southern or western Mexico, but perhaps they the Galapagos Flycatcher, living thousands of

travel all the way to Central America. In fact, the miles away on an island in the Pacific Ocean.

exact wintering grounds are unknown. In part

this is because there are resident (nonmigratory)

populations of Brown-crested Flycatcher in

Central America and South America as well, with

resident breeding populations as far south as

Argentina. It’s complicated.

Scott Olmstead is a high school

teacher, member of the Arizona Bird

Committee, and occasional guide for

Tropical Birding Tours.

Brown-crested Flycatcher, David Kreidler

VERMILION FLYCATCHER | Fall 2020 17CO N S ER VAT I O N I N AC T I O N

YOUR VOICE,

YOUR VOTE

Nicole Gillett

Conservation Advocate

ngillett@tucsonaudubon.org

This November we will all have a lot on our minds—our health, our friends and family, record

temperatures, fire in the mountains and across the Southwest. There is one action we all need to

take to address these concerns: we must vote.

The number of people placing “climate change and the environment” as their number one voting

priority is rising—now at 14% of registered voters, up from 2–6% in 2016. Yet 10 million of these

environmental voters did not vote in 2016! During the midterm elections we again saw a sweep of

environmentally inclined voters help change the makeup of our Congressional delegations, and yet

the potential is not yet being met.

If we don’t act and vote for birds and the places they need, no one else will. Your power is your vote,

but only if you use it!

PIMA COUNTY VOTER INFORMATION: recorder.pima.gov/ElectionInformation

SANTA CRUZ COUNTY VOTER INFORMATION: santacruzcountyaz.gov/750/Voter-Information

COCHISE COUNTY ELECTIONS: cochise.az.gov/recorder/voter-information

NATIONWIDE INFORMATION: vote.gov

YOU CAN LEARN MORE ABOUT THE ABOVE STUDY AT: environmentalvoter.org/

Migrating Swainson’s Hawks, Ned Harris

THE MIGRATORY BIRD TREATY ACT STANDS YES, YOUR VOTE MATTERS

We have won a critical court battle for birds! US District Judge Valerie

Caproni struck down the federal administration decision to roll back US These past few years, we have shared with you many Action Alerts in

government protections for migratory birds and wrote, referencing the part because it has been a record administration for environmental

time-honored classic work of literature: To Kill a Mockingbird: “It is not rollbacks. At least 95 environmental rules, protections, and laws have

only a sin to kill a mockingbird, it is also a crime.” While this is not the end been targeted for rollback, elimination, or redefinition under the current

of the battle to protect the Migratory Bird Treaty Act, it is a huge win to administration. Data shows that strong environmental policies are actually

celebrate. Continue to follow our updates on the Migratory Bird Treaty Act beneficial to our society and economy—from our health, to job creation,

and join our Free to Fly campaign to make sure your voice is heard at the global competitiveness, and of course, they safeguard our public lands,

federal level. biodiversity, and climate.

All of these rollbacks threaten birds and the places they need:

A BIPARTISAN WIN

• CLEAN WATER—from flyways to nesting locations, birds rely on clean

The Great American Outdoors Act is the win of a generation for our

and secure access to water.

environment, public lands, and communities. What does this look like

here in Southeast Arizona? The passage of this act means a backlog • CLEAR AIR—pollution and toxins can impact every level of the food

of funding needs at our National Parks, such as Saguaro, can finally chain and ecosystem.

be addressed. This Act also permanently funded the Land and Water • CLEAN ENERGY AND CLIMATE CHANGE—Climate change is the

Conservation Fund that brings much needed resources to local parks and biggest threat birds are facing.

open spaces. Overall, this is an amazing example of what we can do when

we come together and voice support for birds and the environment. These challenges are just the tip of the iceberg. Who we vote into power

really matters.

18 VERMILION FLYCATCHER | Fall 2020CO N S ER VAT I O N I N AC T I O N

VIRTUAL FLYWAY: FREE TO FLY CONTINUES!

We are celebrating a big win for the Migratory Bird Treaty Act (MBTA) but the work is not over. Migration continues to captivate the curiosity of scientists

as well as the imaginations of all of us who take notice of the seasonal movements of birds. It is at once fleeting and at our doorsteps. It is also critical to

the survival of our birds.

In response to the attack on the MBTA, Tucson Audubon launched the Free to Fly campaign, and we need YOUR help to create our Virtual Flyway! The

Virtual Flyway represents the phenomenon of migration through the stories of birds along their migratory routes through Southeast Arizona. When it’s

completed, submissions will be housed on a website available to the public, and leveraged when meeting with decision-makers.

Choose your favorite bird and share your creativity to build a Virtual Flyway! Visit tucsonaudubon.org/virtual-flyway for submission details. You can also

email Autumn at asharp@tucsonaubon.org if you have any questions.

When living in the Central Valley of California, Originally from Michigan, one of my first wild- My summers in Arizona were spent at Lake

every fall it was always great to hear the Sandhill life jobs was duck banding for the state of Roosevelt on the water. The weekly trips required

Cranes as they migrate there for the winter from Michigan. I used to think birds were so boring, plenty of hours in the car before reaching our

Northern California, Oregon, Washington, and I did not understand the appeal. But waist-deep destination. I remember Turkey Vultures flying on

Alaska. The unison rattle calls from a pair always in a mucky pond and covered in mosquitos the thermals along AZ-77 through the mountains

caught my attention. I was always fascinated and poison ivy, I stared at a trap full of these and always high above the shores of the lake.

with the fact that fossil records of the Sandhill gorgeous green-headed male and adorable Seeing a Turkey Vulture high above takes me

Crane date back over 2.5 million years. demure female Wood Ducks. I was in love. That back to the many summer days that made up my

—JIM HOAGLAND summer working with ducks was one of the best childhood and my respect for the outdoors.

summers I’ve ever had, and I am so happy that —MATT LUTHERAN

I can still see the bird that started it all for me

here in my new home in Tucson!

—MOLLIE LISKIEWICZ

Contribute to the Virtual Flyway here: TUCSONAUDUBON.ORG/VIRTUAL-FLYWAY

VERMILION FLYCATCHER | Fall 2020 19You can also read