PHYSICAL REVIEW PHYSICS EDUCATION RESEARCH 17, 010103 (2021)

←

→

Page content transcription

If your browser does not render page correctly, please read the page content below

PHYSICAL REVIEW PHYSICS EDUCATION RESEARCH 17, 010103 (2021)

Social positioning in small group interactions

in an investigative science learning environment physics class

David T. Brookes

Department of Physics, California State University,

Chico, 400 W. 1st Street, Chico, California 95929-0202, USA

Yuehai Yang

Department of Natural Sciences, Oregon Institute of Technology,

3201 Campus Drive, Klamath Falls, Oregon 97601, USA

Binod Nainabasti

Department of Physics, Lamar University, 4400 MLK Parkway, Beaumont, Texas 77705, USA

(Received 17 August 2020; accepted 8 January 2021; published 25 January 2021)

We conducted a semester-long ethnographic study of group work in a physics class that implemented the

investigative science learning environment approach. Students’ conversations were videotaped while they

were engaged in group learning activities. Our primary research goal was to better understand what factors

made some groups more effective than others. We developed a coding scheme that uses particular modality

markers such as hedging and upward inflection to identify how students position themselves in these

group conversations. Additionally we quantified group effectiveness by how many key ideas in a particular

activity a group negotiated and resolved through the course of their conversation. This research builds on

theories of social positioning that posit that groups are more effective when their discussion is more

equitable. Our exploratory study indicates that groups whose participants position themselves in a more

equitable way, are more effective at completing challenging physics activities and resolving areas of

confusion that arise.

DOI: 10.1103/PhysRevPhysEducRes.17.010103

I. INTRODUCTION to do it, but rather are asked to advance their knowledge of

a particular physical system under investigation by design-

This research began out of a set of informal observations

ing experiments, analyzing scenarios using multiple rep-

of a highly student-centered interactive classroom. The

resentational tools, or applying their knowledge to achieve

classroom consisted of groups of students working together

some meaningful real-world goal (e.g., “design and imple-

on investigative science learning environment (ISLE)

ment two independent ways to measure the coefficient of

activities [1] in a studiolike setting [2] with little formal

friction between your shoe and a floor tile”). Prior research

lecturing.

has shown that the ISLE approach is effective in its primary

Central to the ISLE approach is the idea that physics

goal of helping students develop scientific reasoning

students acquire scientific habits of mind (often referred to

abilities in the context of physics as compared to students

as scientific abilities) and a deeper understanding of where

who learn physics through a more traditional approach [4].

scientific knowledge comes from by engaging in a process

ISLE students are more aware of how they know what they

of doing physics that mirrors the practices and reasoning

know as compared to traditionally taught students [3].

that physicists implement as they construct their knowledge

Finally, ISLE students have shown significant positive

[3]. Students who learn physics in a class that implements

shifts in their attitudes towards physics [5].

the ISLE approach engage in carefully scaffolded but open-

Just as physicists collaborate to advance their knowl-

ended activities that have specific epistemic (knowledge-

edge, a thriving classroom scientific learning community

generating) goals. Students are not told what to do or how

[6] is key to the ISLE approach. In the class that was the

subject of our research, students worked in their groups

using 20 × 2.50 whiteboards, and tried to reach communal

Published by the American Physical Society under the terms of consensus about their ideas with whole-class “board”

the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license.

Further distribution of this work must maintain attribution to meetings [7,8]. We became interested in how this learning

the author(s) and the published article’s title, journal citation, community was functioning. What we observed was that

and DOI. each year there were a few groups of students who stood

2469-9896=21=17(1)=010103(13) 010103-1 Published by the American Physical SocietyBROOKES, YANG, and NAINABASTI PHYS. REV. PHYS. EDUC. RES. 17, 010103 (2021)

apart from the others. These groups were pivotal groups in This view treats knowledge as an ontological process and

the whole class board meetings where students were posits that students learn by engaging or participating in

expected to converge on consensus ideas. Their ideas were that knowledge-building process, turning the classroom

deeper, more insightful and frequently defined the direction into a knowledge-building community [13]. The origins of

in which the class moved. Two questions that arose were the participationist theoretical framework lie in the under-

what made these effective groups function better and what standing that students can be viewed as participants in a

were the students in those groups doing differently from learning community and wherein they transform their

their peers? participation from peripheral to central [14], or in terms

We decided to video randomly selected episodes of of growing into and transforming the sociocultural activ-

learning activities where students worked together in their ities of that community [15]. Importantly, it is the kind of

groups. We gathered and analyzed data throughout the participation that determines what is learned [15]. In a

semester. We took a grounded theory approach [9] to classroom following the ISLE approach, students partici-

analyzing our data, coming up with descriptive codes while pate in the sociocultural practices of physics. These

simultaneously reading the literature on group collabora- practices include both epistemic practices [5] and repre-

tion. This literature is summarized in Sec. II. We started by sentational [16] or semiotic [17] practices. By engaging in

looking for patterns in student participation when they these practices they are learning physics by doing physics.

talked to each other. In our initial approach we simply tried In summary, if knowledge is a process of knowing, the way

to code students’ conversation for being “on topic” if they in which students participate in that process becomes

were talking about physics, “off topic/disengaged” if they paramount. This is the theoretical perspective that forms

were doing something obviously unrelated to the topic at the basis of the research we will present in this paper.

hand, “writing on the whiteboard” or “uncodable” if they As mentioned in the introduction, within the broader

were silent. We found that off-topic behavior was predictive framework of participation, we became interested in how

of individual student success in the course [10] as measured students participated in group activities and whether this

by their exam scores. On-topic behavior was also signifi- could account for why some groups appear to be more

cantly correlated with exam scores, but the correlation was successful than others.

weak [10,11]. In addition, while members of some groups

clearly interacted with each other much more than in other B. Groups and group effectiveness

groups, thereby creating more opportunities for discussion Why are groups and group work important to student-

and sense making, there were several groups whose centered inquiry learning environments? The ISLE

members interacted on topic a lot and yet failed to engage approach is typically used to structure a highly student-

in deep sense making or make significant progress on the centered inquiry class where students are expected to learn

activities. We needed to look deeper. We started looking at physics by thinking like physicists [18]. They engage in

how students were talking to each other in their intragroup epistemologically authentic inquiry tasks [19] that can be

conversations and we started to identify regular patterns in extremely challenging. The activities that students engage

their language. In this paper, we will present and test a in frequently ask them to design experiments to achieve

specific hypothesis that we developed through our own certain epistemic goals and are highly task interdependent

observations and through reading the literature: The where task interdependence is defined as the degree to

hypothesis is that groups are more effective when group which group members need to collaborate, coordinate, or

members open the collaborative space to discussion and interact in order to complete the assigned task [20]. In short,

sense making by making statements that are prefaced by the task of having students create physics knowledge on

hedges or other similar means that suggest a degree of their own is difficult and working in groups can facilitate

uncertainty in the ideas that are being presented. The data this creative process.

we have analyzed support this hypothesis and we will Groups can function as a source of knowledge con-

discuss (with examples) why those particular behaviors struction [21]. It is understood that group members bring

might be pivotal for the functioning of effective groups. diverse views and experiences to the task. Through verbal

discussion and mediating their discussion with a variety of

II. PARTICIPATION AND GROUP WORK semiotic resources [17], groups converge on shared mean-

ing [22] and consensus understanding [7]. Additionally,

A. The participationist framework research has shown that students learn more from collabo-

The transmissionist or acquisitionist views of learning rating with each other as opposed to working alone and the

both view knowledge in the ontological category of an quality of the group’s interpersonal interactions directly

object that can be given to or acquired by students [12]. In affects learning and transfer [23,24].

contrast, the investigative science learning environment In trying to understand why groups are successful and

approach, around which our classroom is structured, is effective or not, the literature divides the factors that

firmly rooted in the participationist theory of learning [1]. contribute to group effectiveness into two categories:

010103-2SOCIAL POSITIONING IN SMALL GROUP … PHYS. REV. PHYS. EDUC. RES. 17, 010103 (2021)

structural factors and interpersonal factors. Structural group discussions with the self-assurance of the expert.”

factors are factors like the nature of the task that the group (p. 200) While students can position themselves as experts,

is being asked to complete. For example, Mesch, Johnson, Conlin and Scherr have shown that students can create

and Johnson [25] showed that both positive task and reward epistemic distance (thereby opening the space to sense

interdependence are mechanisms that drive group perfor- making) through humor and by rephrasing a statement

mance. Much early research on groups has treated the as a question [32]. How participants position themselves

group as a black box, manipulating structural factors and can be viewed as a matter of equity: For Esmonde, equity

assessing how those affect group performance [26]. More in a group is the fair distribution of opportunities to learn.

recent research has started to look inside the black box This includes both access to the content and to the

at interpersonal factors that affect group effectiveness. discourse practices of the field, but also access to positional

Research has begun to focus more on how the group identities [30].

members interact and relate to each other as they work. Researching group interactions, Fragale [33] demon-

Various interpersonal factors that affect groups have strated that when groups of people are asked to collaborate

been identified. Williams Woolley and colleagues [27], in to solve a problem, the way they talk to each other is critical

measuring the collective intelligence of a group (using a to whether ideas are heard and taken up by the group.

number of open-ended group tasks), found that the social Group members who made hedged statements or softened

sensitivity of the group members was more predictive of the their statement with an attached question, achieved higher

collective intelligence of the group than individual IQs status and recognition when the task was more interdepend-

of the group members. Similarly, Barron found that there ent whereas the powerful speakers (members who made

was no correlation between prior math performance and the emphatic or unhedged statements) were accorded higher

success of groups of three sixth graders engaged in a status when the activity had lower task interdependence.

challenging math problem [23]. An emphatic or unhedged statement is one like “The

Edmondson [28] found that team learning behavior was answer is X,” while a hedged version of the same statement

highly dependent on the climate of psychological safety would be “I think the answer might be X.” In the field of

in the team. Julia Rozovsky, a researcher at Google, found linguistics, it is understood that when language users use

that the effectiveness of a team is primarily determined by language to communicate information, they introduce

how the people on the team interact: “Who is on a team uncertainty into an otherwise emphatic statement of fact,

matters less than how the team members interact, structure by using hedges and even upward inflection at the end of

their work, and view their contributions.” [29] She too has the sentence, denoting an “epistemic stance” towards the

identified “psychological safety” as the key variable that information contained therein [34]. This is referred to as

predicts whether a team will be successful or not. “modalizing” the statement [35].

Psychological safety is defined by Edmondson as “… a In developing our coding scheme described in Sec. III C

shared belief that the team is safe for interpersonal risk below we have combined these disparate ideas that (a) peo-

taking,” giving members the confidence to speak up; and, ple position themselves as experts or novices in a given

“This confidence stems from mutual respect and trust conversation, and (b) people introduce degrees of uncer-

among team members.” [28] (p. 354) tainty into their statements through hedges and inflections,

While prior research has been based on the subjective thereby softening their “expert” position. In this way we

perceptions of group members [21], we want to go beyond have extended previous work on positioning in which

this in our research. In this paper, we aim to shed light on researchers mainly focused on students assuming either an

the underlying processes that promote psychological safety expert or a novice position in conversation.

in a group and the feeling of mutual respect and appreci-

ation in an ecologically valid classroom setting. D. Measuring group learning effectiveness

Measuring group effectiveness is one of the most

C. Group interactions viewed through difficult theoretical issues that we faced in our research.

a participationist lens There is a paucity of literature that adequately discusses

The idea of positioning is a relatively new construct how to directly measure how effective a group is. Williams

in the participationist framework. Esmonde [30] has sug- Woolley and colleagues [27] measured collective intelli-

gested that students position themselves in interactions and gence of a group through a series of open-ended tasks like

that this act of positioning can create or reduce learning “think up as many unique uses for a brick as you can

opportunities for others in the group. Bonderup Dohn [31] in 1 minute.” Both Barron [23], and Menekse and Chi [24]

has argued that students can dynamically position them- used a post-test to measure student learning from prior

selves moment by moment, thereby negotiating a transient group collaboration, but these approaches sacrifice the

participatory identity for themselves within a particular ecological validity of an actual classroom setting for a

activity that they are engaged in: “The ‘expert’ students did more controlled lab intervention. Measuring how effective

not explicitly say ‘I am an expert,’ but they took the lead in a group is in an ecologically valid classroom learning

010103-3BROOKES, YANG, and NAINABASTI PHYS. REV. PHYS. EDUC. RES. 17, 010103 (2021)

context is less well defined. For example, one may think to development of the students [37], and generally could

measure group effectiveness by how quickly and accurately not be completed by even the very best students working

the group completes an assigned learning activity. Yet, how alone. Additionally, task and reward interdependence were

many key points of each learning activity did the group built into the environment with shared grades for lab

examine and really grapple with? A group may complete a activities. Board meetings, where groups were asked to

task quickly, but not really engage in the difficult parts of present their results, inculcated a sense of shared enterprise

the task. On the other hand, a group can get stuck and go in the learning process.

nowhere, following irrelevant tangents and becoming lost, Students were audio-video recorded 14 separate times

resulting in an incomplete assignment. during the semester. The room was arranged in such a way

Edmondson [28] provides a definition of team learning that there were 5 rectangular tables with two groups of 3

behavior that is helpful to understand group learning seated opposite each other at the same table. This design

effectiveness: choice followed the recommendation of the SCALE-UP

project [38], that the learning environment should be

“I conceptualize learning at the group level of analysis designed to allow local interactions between groups,

as an ongoing process of reflection and action, char- thereby fostering smaller communities within the larger

acterized by asking questions, seeking feedback, exper- classroom learning community. Each table was recorded

imenting, reflecting on results, and discussing errors or using a miniature camera mounted in the ceiling. A voice

unexpected outcomes of actions. For a team to discover recorder was placed in the middle of the table to acquire the

gaps in its plans and make changes accordingly, team best possible audio. The audio and video tracks were

members must test assumptions and discuss differences synced up afterwards in Final Cut Pro. In total, we gathered

of opinion openly rather than privately or outside the about 70 h of data. A view of one table setup is shown

group. I refer to this set of activities as learning in Fig. 1.

behavior, as it is through them that learning is enacted Students were randomly assigned to their groups at the

at the group level.” (p. 353) start of the semester. They were then randomly reassigned

to new groups by the instructor one week later to allow

This description served as an inspiration for our approach them to meet new people and experience a new group

to quantifying group learning effectiveness (or “group dynamic. One week after that, students were instructed to

effectiveness” for short) described in Sec. III D below. choose their own groups (without the intervention of the

An effective group does more than get correct answers, they instructor) and those groups remained together for the rest

engage in contentious issues and also find ways to resolve of the semester. This is important because the episodes of

their uncertainties and difficulties, using the instructor or student work we chose to analyze are all from the months of

textbook as a resource; or (more preferably) by engaging in October and November, after the groups were well estab-

the practices of physics (including experimentation, exam- lished. We decided not to analyze episodes recorded in

ining assumptions, and/or coordinating semiotic resources, September because groups were still getting themselves

etc.), reaching consensus on their own. established and learning how to work together effectively.

We labeled the ten groups A–J.

III. METHODOLOGY

A. A description of the classroom

Our research took place in a student-centered introduc-

tory university-level calculus-based physics class of 30

students. Students were ethnically diverse and many were

first-generation college students. Students engaged in a

variety of epistemically authentic guided inquiry learning

activities [36] based on the ISLE approach [3]. Working in

10 groups of 3 students each, students would sometimes

engage in experimentation, sometimes working on devel-

oping a model, or applying physical ideas to solve a real-

world problem using a group whiteboard. Groups then

presented their ideas to each in a whole-class board

meeting, reaching consensus through discussion and guid-

ance from the instructor. The instructor would then some-

times summarize a key point or idea in a short 5-min

lecture. Activities were open ended, sometimes ill struc- FIG. 1. A view of the setup of one table, as viewed from the

tured, often at the edge of the zone of proximal video camera.

010103-4SOCIAL POSITIONING IN SMALL GROUP … PHYS. REV. PHYS. EDUC. RES. 17, 010103 (2021)

upward inflection and other means of indicating uncer-

tainty. A student who assumes a “novice” position by

asking a question, can do this in different ways: They can

ask a probing question that potentially contributes to

driving the conversation forward, or can ask a question

or make a statement that suggests some degree of help-

lessness or lack of knowledge. Lastly, a student can make

comments that have little conceptual content, yet support

the discussion in a productive manner by directing the

focus of the group, discussing the purpose of an activity, or

providing encouragement or support to one or more other

group members. We call these “facilitation” moves. Table I

describes and gives examples of each positional move.

Additionally, we applied the following rules when

coding 15 second segments of conversation: If a student

only made firm statements in the interval they were coded

1. If, in addition to firm statements they also made any

hedge in that 15 sec interval, they were coded 2 instead.

FIG. 2. The questions that students were working on for the If a student made firm statements and asked a question in

three episodes we analyzed. an interval they were coded 2. If a student only asked

questions in an interval they were coded 3 or 4 by the

B. Coded episodes criteria in the table. If a student only made a facilitation

move or moves in the 15 sec interval they were coded 5,

We selected three episodes of student work to code. The otherwise the facilitation was ignored. Off-topic conversa-

questions that students were asked to work on for each tions were not coded, thus coded segments represent time

of the episodes are shown in Fig. 2. The episodes were spent engaged in on-topic discussion. Finally, affirmative

selected because they were typical of all the episodes in the statements like “yes,” “I agree,” and “right!” were not

October-November time period. considered in the coding scheme since we found it

impossible to assign an unambiguous positional identity

C. Coding scheme to these.

The coding scheme we developed identifies five “posi-

tional moves” that students can make during conversation. 1. Coding and interrater reliability

A student who positions themselves as an expert providing For each group in each episode, we selected a 10–15 min

an idea or answering a question can do so in a “firm” continuous segment to code. We coded each group sepa-

manner or “softened” (modalized) manner, using hedges, rately. We only coded conversations between the three

TABLE I. Table of 5 positional moves including examples.

Positional

move (code) Description Example(s)

Expert (1) Firm statements of fact or firm or strong Thomas (Ep. 3) “No gravitational energy, so work is equal to mv

disagreement. initial, squared, minus mv final squared.” [downward inflection]

Intermediate Softened statements or softened disagreement, José (Ep. 1): “And it’s the same as this one, right?”

expert (2) using hedges or upward inflection at the end Helen (Ep. 2): “So, direction of acceleration should be…up” [there

of a sentence. is a slight pause before “up” and it is inflected upwards.]

Intermediate Questions that drive the conversation. Chris (Ep 2.) “Can we say that constant speed is the same as

novice (3) constant velocity?”

Jessica (Ep. 3): “What about the change in energy initial?”

Novice (4) Questions or statements that convey Joseph (Ep 1): “I don’t know what the tilt would be.”

helplessness or general confusion.

Facilitator (5) Metalevel statements or questions that facilitate Paul (Ep. 2): “Just like we got here. Alright!”

the discussion in some way. [Paul high fives Helen next to him.]

Donald (Ep. 3): “It says place an object on the scale,

note the reading.”

010103-5BROOKES, YANG, and NAINABASTI PHYS. REV. PHYS. EDUC. RES. 17, 010103 (2021)

TABLE II. Group effectiveness scores for all 10 groups for the roller coaster activity.

Group A B C D E F G H I J

(b) Identify 2 forces (Ftrack on car and mg only) 1 1 0 1 1 1 0 3 3 1

(b) Get direction of ar (up) 2 3 2 3 2 3 0 1 1 0

(b) Recognize Ftrack on car > mg–connected to direction of ar 3 0 0 1 1 2 0 1 1 0

(c) Get direction of ar (down) 2 0 1 1 0 3 0 0 1 0

(c) Identify 2 forces (Ftrack on car and mg only) 1 1 0 0 0 1 0 1 0 0

(c) Recognize Ftrack on car points downwards 3 0 0 0 0 2 0 2 0 0

(c) Connect Ftrack on car þ mg, to ar . 2 0 1 0 0 2 0 1 0 0

Total score 14 5 4 6 4 14 0 9 6 1

group members; any conversation between the two groups as a fraction of total number of social positioning codes

seated at the same table was ignored. We broke the for each group. Note that percentages do not add to 100%

transcript into 15 sec segments and assigned a position because groups could either be engaged in off-topic

to each group member according to the coding scheme conversation or completely silent for certain 15-sec inter-

described above. We examined interrater reliability by vals of the segment we coded.

having two coders independently code the same transcript.

Most discrepancies between coders occurred because the

boundaries of the 15-second time intervals had to be treated

somewhat elastically because sometimes the boundary

occurred while a student was in the middle of a sentence.

After resolving boundary discrepancies we were able to

achieve an average Cohen’s Kappa of 0.79 across 5

randomly selected groups. Having established reliability,

the remaining groups were coded by one coder.

D. Quantifying group effectiveness

We also need a way to quantify the learning effectiveness

of each group. We created a quantitative measure of group

effectiveness as follows: Each activity had a number of key

points that students need to discuss or wrestle with in order

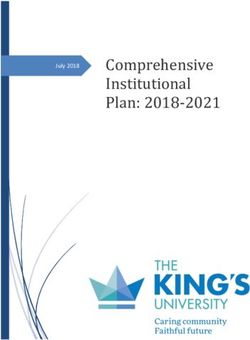

to figure out the problem and come out with an answer. We FIG. 3. The distribution of social positions for each group in

identified all the key points that each activity entailed. Then “scale tilt” activity, episode 1. Columns represent percentage of

1, 2, 3, 4, and 5 codes as a fraction of total number of codes,

the group was scored on each key point out of 3 points total:

scaled by the amount of coded time.

1 point if the group members correctly addressed a key

point without discussion or questioning it, and without

justification, 1 point for verbally justifying their reasoning

using normative physics knowledge, and 1 point if the

group questioned and wrestled with a particular key point.

We identified key points as common stumbling blocks such

as in part (b). of the roller coaster activity, where the car

is at the bottom of the loop, students tend to start from the

idea that Ftrack on car ¼ FEarth on car from part (a), but they

need to recognize that Ftrack on car > FEarth on car in order to

keep the car moving in circular motion at that point. The

scoring of the roller coaster activity is shown in Table II.

IV. FINDINGS AND ANALYSIS

A. Quantitative analysis

FIG. 4. The composition of social positions for each group in

1. Positional coding and group effectiveness

“roller coaster” activity, episode 2. Columns represent percentage

Figures 3–5 show group positional distribution during of 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5 codes as a fraction of total number of codes,

the three episodes, i.e., percentage of code 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5 scaled by the amount of coded time.

010103-6SOCIAL POSITIONING IN SMALL GROUP … PHYS. REV. PHYS. EDUC. RES. 17, 010103 (2021)

TABLE IV. Groups’effectiveness score (Effect) for each epi-

sode and ranked by total effectiveness score from highest to

lowest.

Rank Group Effect (E1) Effect (E2) Effect (E3) Effect total

1 A 10 14 11 35

2 F 10 14 9 33

3 H 7 9 6 22

4 I 6 6 8 20

5 D 5 6 7 18

6 B 5 5 6 16

7 C 3 4 6 13

8 G 5 0 5 10

9 J 5 1 3 9

10 E 4 4 0 8

FIG. 5. The composition of social positions for each group in

“energy bar-chart” activity, episode 3. Columns represent per-

centage of 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5 codes as a fraction of total number of

codes, scaled by the amount of coded time. the remaining 6 groups, who spent significantly more of

their time engaged in on-topic conversation, these groups

Table III shows the average time that groups spent display very distinct distributions of positional moves.

One pattern in particular stands out: Members of groups

engaged in on-topic conversation, averaged across the

A and F consistently adopted the “intermediate expert”

three coded episodes.

position (code 2) more frequently than the expert position

Next, we coded the effectiveness of each group for each

(code 1) across all 3 episodes. They stand apart from the

of the three activities they engaged in. The results of this

other 4 groups except for one occasion in episode 2 when

coding are shown in Table IV, ranked from overall most to

group H matched this code 2 versus code 1 distribution.

least effective.

While on-topic conversation seems generally predictive of

There are three key patterns we can observe from these

group effectiveness (the four least effective groups spend

data. There are some groups that do not talk much to each

the least amount of time engaged in on-topic conversation),

other about the physics topic as compared to all other

there is no correlation between the amount of time spent

groups. These are groups C, E, G, and J, as indicated by

on topic and group effectiveness among the top 6 groups.

their total amount of interaction in the figures and table.

This fact, combined with the notable pattern of interaction

Across the three coded episodes their average interaction

displayed by groups A and F, motivated the next part of our

times were 29%, 37%, 43%, and 39%, respectively (see

analysis.

Table III). The next lowest group (group B) interacted an

average of 57% of the time. It turned out that these four

2. The relationship between group equality

groups were also the 4 least effective groups in the class

and group effectiveness

(see Table IV). Perhaps unsurprisingly, group members

need to talk to each other about the topic in order to engage According to the ideas presented so far, code 2 and code

in sense making and learning as a group. Focusing only on 3 represent conversations that promote equality among

group members, while code 1 and code 4 conversations do

the opposite, they promote inequality among group mem-

TABLE III. Total time spent talking about the topic averaged

bers. Therefore we defined a “group equality” score by

across three episodes. Note: because some segments are longer adding the number of 2 and 3 codes for each group and

than others, they carry more weight in the average. subtracting from that, the combined total of 1 and 4 codes.

The larger the equality score, the more equal that group is in

Group Total interaction % Rank their discussions. Group equality scores are shown in

F 74% 1 Table V, ranked from most equal to least (highest to lowest).

I 73% 2 Table V shows that groups A and F exhibit a distinctive

H 72% 3 pattern across the 3 episodes. In these two groups, the

A 69% 4 percentage of code 2þ code 3 is consistently larger, while

D 67% 5 their percentage of code 1 + code 4 is consistently smaller

B 57% 6 than groups B, D, H, and I, who all share a similar amount

G 43% 7 of total interaction time. Notice that for group J, their

J 39% 8 equality score is quite high, while their total amount of

E 37% 9

interactions remain low. This was a result of a regularly

C 29% 10

occurring group dynamic that we will examine in greater

010103-7BROOKES, YANG, and NAINABASTI PHYS. REV. PHYS. EDUC. RES. 17, 010103 (2021)

TABLE V. Group equality score (Eq.): Difference (2 þ 3) codes positioning (measured by the equality scores) is a necessary

− (1 þ 4) codes ranked from overall highest to lowest. but not a sufficient condition for the group to be effective.

While groups like group J are interesting in their own

Rank Group Eq. (E1) Eq. (E2) Eq. (E3) Eq. avg.

right, they are not the focus of our research questions in this

1 F 24 56 18 32.7 paper. As mentioned in the introduction, we are trying to

2 A 27 29 26 27.3 understand why some groups outperform others in their

3 H 0 37 4 13.7 learning effectiveness, irrespective of how much they

4 J 2 8 17 9.0

interact with each other. Groups A, B, D, F, H, and I

5 B 5 2 8 5.0

6 E −2 3 11 4.0 are thus the groups we want to focus on.

7 C −1 2 2 1.0 In Table VI we performed a set of rank-order correlation

8 D −10 10 −3 −1.0 tests comparing the effectiveness of the top 6 groups to their

9 G −7 3 −2 −2.0 group equality score across the three episodes.

10 I −24 2 14 −2.7 It is necessary to use a nonparametric permutation test to

estimate p values because of our small sample size, which

violates most of the inherent assumptions of the standard

parametric tests, namely, homoscedasticity, normal distri-

detail in Sec. IV B below. The short summary is that a bution, etc. Following the recommendation of Lakens et al.

member from group J made bids to start a conversation with [39], we are deliberately avoiding the term “statistical

other group members by making statements with hedging significance” in our analysis. Rather, following Lakens’s

words and asking meaningful questions. However, his recommendation [39], we examine what α level is appro-

positional moves were not taken up by other group priate for us to observe a large effect in the potential relation

members; the initiating group member was either rebuffed between group effectiveness and equality score. According

with emphatic statements (code 1) or was simply ignored to Cohen [40], an effect size r2 ¼ 0.25 ðr ¼ 0.5Þ is con-

by other group members. As a result, the conversation sidered to be the minimum boundary for a “large effect.”

petered out [31]. The probability p of this happening by random chance in a

For example, in episode 3 sample of n ¼ 6 is 0.3. Thus we can consider any p value

lower than 0.3 (r > 0.5) to be indicative of a likely relation

Donald: What do we do with the bar chart?, between group effectiveness and equality score. Each of the

[Long silence, the other group members do not re- observed correlations between group effectiveness and

spond.] equality score in Table VI are larger than 0.5 and all

Donald: So it started with kinetic energy [tailing off], probabilities are less than 0.3. Additionally, the probability

and then no kinetic energy, that this association between group effectiveness and group

[Other group members remain silent] equality occurred by random chance across the three

episodes is 0.18 × 0.06 × 0.07 ¼ 0.0008. The null hypoth-

The interaction ended there. Notice that Donald made two esis that there is no association between group effectiveness

bids to start a discussion: first with an intermediate novice and group equality can be rejected.

position (code 3), and then with an intermediate expert

position (code 2). Both attempts amount to bids to engage

other group members. However, neither of these 2 posi- B. Qualitative analysis

tional moves were recognized by his colleagues, and The coding scheme above only captures limited aspects

collaboration did not happen. Our data suggests that equal of how the group members are interacting with each other.

TABLE VI. Effectiveness versus equality score for the top 6 most talkative groups for all three episodes. Probability that each of

these correlations happened by random chance (p) was calculated using a nondirectional permutation test to create a sampling

distribution of r’s.

Group Effect Rank effect Eq. Rank Eq. Group Effect Rank effect Eq. Rank Eq. Group Effect Rank effect Eq. Rank Eq.

Episode 1: Scale tilt Episode 2: Roller coaster Episode 3: Energy bar chart

A 10 1.5 27 1 F 14 1.5 56 1 A 11 1 26 1

F 10 1.5 24 2 A 14 1.5 29 3 F 9 2 18 2

H 7 3 0 4 H 9 3 37 2 I 8 3 14 3

I 6 4 −24 6 D 6 4.5 10 4 D 7 4 −3 6

D 5 5.5 −10 5 I 6 4.5 2 5.5 H 6 5.5 4 5

B 5 5.5 5 3 B 5 6 2 5.5 B 6 5.5 8 4

rp ¼ 0.65; p ¼ 0.18 rp ¼ 0.85; p ¼ 0.06 rp ¼ 0.81; p ¼ 0.07

010103-8SOCIAL POSITIONING IN SMALL GROUP … PHYS. REV. PHYS. EDUC. RES. 17, 010103 (2021)

In this section we present a fuller or richer picture of the Robert: Yeah, I know. There’s acceleration in the radial

moment-by-moment dynamics that show what a more direction, that’s it.

equal or a less equal conversation between group members Ronald: But what does that tell you about force?

looks like. In the following sections we will present three Robert: Huh?

examples from, and draw contrasts between, groups A, D, Ronald: What does that tell you about force? You have

and I. We focus on these three groups because they are acceleration in the radial direction, but what about the

comparable in terms of the amount of time they spend in force, up and down?

conversation (69%, 67%, and 73%, respectively) and yet Robert: If you have force in the radial direction, I mean

their outcomes in terms of group effectiveness (average acceleration in the radial direction, you have force in

11.7, 6.0, 6.7) are strikingly different. We will use these the radial direction.

three examples to highlight a number of common patterns Ronald: What would the force diagram be… [inaudible

of behavior that we observed repeatedly throughout the as Robert talks over him.]

episodes we coded. Robert: Huh?

Ronald: What would the force diagram be?

1. When bids to open the conversation fail Robert: Pointing towards the center.

Ronald: Yeah?

The pattern of conversation we examine in this section Robert: Yeah, that’s it!

was observed across multiple groups. Often a group Ronald: From a top view…

member would try to open the conversation with another Robert: From a top view, yeah.

group member, either by asking questions or offering George: But [inaudible] the force going upwards

hedged statements ending in phrases like “right?” or “what though, also.

do you think?” Instead of engaging in the conversation the [Robert ignores him and continues drawing on the

second group member shut down the conversation with whiteboard.]

both (a) emphatic (code 1) statements that often came

across as aggressive or condescending, and (b) by ignoring This short excerpt epitomizes the failure of what could

the group member who was trying to initiate the con- have turned into a productive conversation and shows how

versation. The following example from group D is a model expert positioning can lead to a dynamic of inequality in the

example of this pattern of interaction with one group group. The group has already established that the upward

member employing both techniques to shut down the force exerted by the track on the car balances the downward

conversation. In the following excerpt from October 15 force exerted by Earth on the car in the previous case of

(episode 2) Group D are trying to draw a force diagram moving along a horizontal track at constant velocity. Now,

for a moving roller coaster car at the bottom of a Ronald is trying to understand how to draw a force diagram

circular loop. for the next case and seems to recognize that it shouldn’t be

the same as before, but appears unsure how to continue.

[Ronald is talking to George. Robert is involved in a Instead of using Ronald’s questions as a chance to open up

separate conversation with group C.] a dialogue, Robert shuts down the conversation. In the

Ronald: If the Earth was stronger it would be falling. excerpt above Robert mostly maintains an expert position

George: Technically it wouldn’t be falling because the… (code 1). Robert comes across as dismissive of Ronald’s

the force of… the rails pulling it up. repeated questioning when he cuts across him saying

Ronald: What would the force diagram be for (b)? “huh?” and instead of just providing affirmation he says

[He raises his voice above the noise at the table and “Yeah, that’s it!” in an emphatic downward inflection.

directs his gaze towards Robert. Robert ignores him and While one group member can make bids to open the

continues writing on the whiteboard—his conversation collaborative space through hedged statements (code 2) and

with group C has ended by this point.] focused questions (code 3), the other group members must

[Ronald raises his voice louder—there is no mistaking necessarily listen to and respect the statement or question

he’s trying to make sure Robert hears him above and take it up, integrating it into the conversation. The need

another conversation happening between the members for mutual respect is a key factor that we found in our

of group C next to them.] deeper qualitative analysis.

Ronald: Like for (c) it’s going down so the force of the

Earth is longer or it would be falling.

Robert: Yeah, it’s going to be balanced there too. So if 2. In effective groups, everyone’s contribution matters

you are making a top view, then there’s acceleration Contrast the conversation above with the next excerpt

towards the radial direction. If it’s the frontal view, then from group A. Superficially the two groups are similar in

like, the upward forces are balanced because it’s not the sense that (a) they spend roughly the same amount of

really moving up or down. It’s just moving in a circle. time talking, and (b) similar to Robert in group D, one

Ronald: But in terms of the force diagram… person (José) is controlling the whiteboard and markers.

010103-9BROOKES, YANG, and NAINABASTI PHYS. REV. PHYS. EDUC. RES. 17, 010103 (2021)

In this excerpt from episode 1, group A is working on that needed to be struggled with and resolved in order to

trying to draw force diagrams for the cases of a horizontal successfully complete the activity.

scale and a tilted scale. (Episode 1, October 3.)

José: We have to balance it out because it’s not moving.

José: So, force of Earth on weight, The net force needs to be zero on the y and the x.

Nancy: And… [They have chosen to orient their coordinate system

Nancy and José in unison: force of scale… aligned with vertical and horizontal rather than aligned

Jessica: They’re equal to each other [inaudible] with the tilted scale]

José: Is there…? would we include…? No, there’s no… Jessica: What if we break this one [leans over and

Jessica: no, [inaudible] it’s not moving. points] if we break this up into an x and a y. The y

Nancy: And then you put the little… component and this [points to the frictional force], the

José Oh, but now there is… scale on the weight, would be equal to the force of

Nancy: Yes the Earth on the weight and now we just need to figure

José: In this one. out x.

Jessica: [inaudible] is holding it up. José: So would those [inaudible] I mean…

José: Right, so then in this case… Jessica: Perpendicular?

Nancy: You still have earth acting upon it not as strong. [José leans over, asks to borrow the scale from group B.

José: And it’s the same [draws]… as this one, right? They stare at the scale as he tilts it. Nancy measures the

Nancy: Yes. And then… angle with a protractor, finds it to be 10 degrees and

José: Now. says “good job” to José and laughs.]

Jessica: So for the scale it’s less. [upward inflection, José: [looking at the weight on the scale] So, what’s

coded as a hedge (code 2).] keeping it from moving? [rhetorical] There’s the static

Nancy: It’s, it’s more this way, right? friction that’s holding it. It’s making it go that way. It’s

José: So… just like, the direction of the surface.

Nancy: It’s going like that. [Long 20-sec silence, all three group members stare at

the scale. José asks group B sitting opposite to explain

In this short excerpt one can observe a number of their force diagram.]

behaviors that we found to be typical of the two most

effective groups, A and F. Although José is doing the This excerpt highlights a common pattern of behaviors

writing and, from our more general observations, is seen as of both groups A and F. They were unable to reach a

the group leader, he is not controlling the conversation. All resolution on their own at this point, but because they were

three members display a remarkable pattern of turn-taking listening to and respecting each other’s ideas, they recog-

and overlapping complementary conversation, that shows nize they have something that is inconsistent (in this case an

that the three group members are positioned as equals. The unbalanced force) that needs resolving. Instead of moving

transcript shows how participants overlap their conversa- on they are able to struggle with the inconsistency and try to

tion in a complementary way by completing each other’s resolve it, first by employing standard representational

ideas rather than cutting each other off, sometimes even resources of physics and, second, by using hedged state-

talking in unison. Everyone gets to contribute something to ments and asking probing questions that engaged all three

the conversation. Every group member says something group members in the conversation.

valuable in this short 52-sec excerpt. More importantly

each idea is taken up by the group. For example when

Jessica says “… is holding it up.” José immediately 3. When two group members butt heads

responds with “right.” The following excerpt from group I illustrates what

During the 52 sec, José, Nancy, and Jessica all made a frequently happened when two group members both

clearly hedged statement (coded 2) either by inserting a positioned themselves as experts (code 1) but on opposite

“right?” and the end of their statement (José and Nancy), sides of an issue. In the following excerpt from episode 1

or in Jessica’s case by inflecting her statement upwards, the group has just finished watching the reading on the

making it sound more questionlike. These hedges open the tilted scale decrease.

space up for all group members to participate in an

equitable way. James: Why? [referring to the decreased scale reading.]

Roughly 6 min later group A reached an impasse Lisa: Draw a force diagram for each situation.

because they incorrectly drew the force exerted by the [Gary starts drawing on the board. James immediately

scale plate on the object pointing vertically upwards even interrupts him]

though the scale was tilted 10 degrees. This was one of the James: No, no, draw a tilted, a tilted… Instead of

key points we identified in our group effectiveness coding drawing like that, draw it like this

010103-10SOCIAL POSITIONING IN SMALL GROUP … PHYS. REV. PHYS. EDUC. RES. 17, 010103 (2021)

[James: draws a cross with his finger hovering their language or asking questions, but can be rebuffed,

over the whiteboard, the cross is oriented diagonally or completely ignored by another group member. In the

like × rather than þ.] examples, the ensuing silence quickly leads to frustration

Gary: Huh? What is it? It’s supposed to be like this. and failure (the task was not completed). In other words,

Force of the Earth is still going down! hedged statements only work when the ideas contained

James: Ya therein are acknowledged and taken up by other group

Gary: What are you talking about? members. While adding uncertainty to a statement may

Gary: x and y would still be x and y [He draws a cross increase the probability of that idea being heard, it does not

with his finger hovering over the whiteboard, the cross guarantee it. We have observed that it takes only one group

is oriented þ.] member to “sabotage” a productive conversation.

James: [continues drawing, speaking quietly] So, so so, What possible mechanism could there be behind why

it will be much better for us. hedged statements and meaningful questions are such clear

Gary: That makes no sense. x and y is still, even though indicators of an effective group? We hypothesize that, for a

it… even though it’s tilted, x is still x, y is still y participant to position themselves as an intermediate expert

[gestures down then sideways with his index finger] or intermediate novice, it takes a conscious effort and

Gary: Oh my god, here, [places a marker down hard on intentionality to learn and explore in a state of discomfort

the whiteboard in front of James] do yours. and uncertainty. In contrast, assuming the position of expert

when you are not 100% certain entails some degree of

James’s idea is productive. Tilting the coordinate system bluster, pretending that you know what you are talking

is a significant step in this activity. Consistent with the about more than you really do. Alternatively, making an

findings of Fragale [33] (that unhedged statements are emphatic statement may simply be a quick way to get to a

accorded lower status in highly task-involved tasks) Gary desired conversational end point, while adding a hedge

did not give James’s unhedged idea much consideration. when you feel 100% confident in your response, requires a

A mutual disrespect between Gary and James quickly certain level of conscious social sensitivity and willingness

devolved to the point they continued working separately on to prolong the conversation. We have noticed this in

the same force diagram instead of engaging in the neces- transforming our own practice in communicating with

sary productive struggle to solve the critical aspects of the colleagues and students: We have discovered that adding

activity. a right? at the end of a statement is highly effective in

opening the space to the contributions of other participants

V. DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSION in the conversation. Yet, it takes a level of conscious mental

effort to remember to soften one’s tone. Taking on the

We have found a correlation between group effectiveness

novice position may involve either (a) Asking to be fed

and group equality as indicated by the amount of time

information without too much intellectual input (“What is

group members spend positioning themselves in the posi-

the answer to this problem?”) or (b) may arise because of

tions of intermediate novice and intermediate expert. From

task avoidance (“I have no idea what is going on here”).

our quantitative and qualitative analysis, it appears that the

Both expert and novice positions can both clearly have a

most effective groups display a cluster of behaviors [41]

detrimental effect on group learning effectiveness that

that complement each other in a myriad of ways that are

requires group members to explore difficult questions

beyond the scope of this paper to elaborate. Not only do

and be comfortable with uncertainty.

they have more equal conversations and are better able to

sustain their attention during periods of adversity and

frustration, they also, according to our observations, sit A. Limitations of the study

closer to each other and often are the first groups to start a While we have found that group effectiveness is corre-

new activity. In addition, group dynamics vary from day to lated with group equality score (based on the positioning of

day. Some groups are consistently more effective than the group members), we cannot conclude there is a causal

others. But we observed days when group H (for example) link between the two. Additionally our sample size is small

worked quite effectively together, and when they did their and our study is limited to a unique physics class that is

equality score increased. focused on students figuring physics out for themselves and

The qualitative analysis shows that the underlying building a consensus through discussion. We have, how-

factors of respect and psychological safety are also key ever, found some generalizability of our results. In another

for a group to be successful. We suggest that the theme study that applied the coding scheme developed in this

of respect that emerged from our qualitative analysis is paper to a whole-class discussion of about 20 physics

connected to positioning because it is difficult or impos- students, it was found that successful consensus building

sible to convey mutual respect if group members are was strongly connected with the amount and frequency of

constantly positioning themselves as experts. As we have hedged statements during a discussion about a contentious

shown, one student can make bids to engage by hedging physics idea [42].

010103-11BROOKES, YANG, and NAINABASTI PHYS. REV. PHYS. EDUC. RES. 17, 010103 (2021)

B. Implications for instruction ten showed evidence they were able to collaborate effec-

As mentioned previously, we do not suggest a causal link tively on a regular basis. It appears that effective collabo-

between the social positioning of group members and the ration is rare, rather than the norm. We suggest that groups

effectiveness of the group. Therefore, telling group mem- of students may benefit from explicit training in how to

bers to “soften your tone” when talking to each other is work together in a more effective way, learning to under-

probably not going to be an effective way to improve group stand the benefit of listening to the ideas and questions of

dynamics. Rather, we suspect that mutual respect and a all group members and valuing the diverse contributions

shared orientation towards the task among group members that different group members may bring to the table.

form the basis for a cluster of behaviors that manifest

themselves in these particular idiosyncratic patterns of ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

discourse. We believe our research supports and is aligned

with the work of Tobin and colleagues who talk about We thank Eugenia Etkina for reading and editing our

training students in the skill of “cogenerative dialoguing” manuscript and José Robles for drawing our attention to the

so that they can safely identify issues and transform their importance of mutual respect among group members. We

group practice [43,44]. It is striking that in a classroom that thank three anonymous reviewers for their insightful and

emphasized collaborative learning, only two groups out of constructive comments which greatly improved our paper.

[1] E. Etkina and A. Van Heuvelen, Investigative science in Proceedings of the 2015 Physics Education Research

learning environment–A science process approach to learn- Conference, edited by A. D. Churukian, D. L. Jones, and L.

ing physics, in Research-Based Reform of University Phys- Ding (AIP, New York, 2015), pp. 231–234.

ics, Vol. 1, edited by E. F. Redish and P. J. Cooney (2007), [11] B. Nainabasti, D. T. Brookes, and Y. Yang, Students’

https://www.per-central.org/items/detail.cfm?ID=4988. participation and its relationship to success in an Interactive

[2] J. M. Wilson, The CUPLE physics studio, Phys. Teach. 32, Learning Environment, in Proceedings of the 2014

518 (1994). Physics Education Research Conference, edited by P. V.

[3] E. Etkina, Millikan Award lecture: Students of physics— Engelhardt, A. D. Churukian, and D. L. Jones (AIP,

Listeners, observers, or collaborative participants in phys- New York, 2015), pp. 195–198.

ics scientific practices?, Am. J. Phys. 83, 669 (2015). [12] A. Sfard, When the rules of discourse change, but

[4] E. Etkina, A. Karelina, M. Ruibal-Villasenor, D. Rosengrant, nobody tells you: Making sense of mathematics learning

R. Jordan, and C. E. Hmelo-Silver, Design and reflection help from a commognitive standpoint, J. Learn. Sci. 16, 565

students develop scientific abilities: Learning in introductory (2007).

physics laboratories, J. Learn. Sci. 19, 54 (2010). [13] M. Scardamalia and C. Bereiter, Computer support for

[5] D. T. Brookes, E. Etkina, and G. Planinsic, Implementing knowledge-building communities, J. Learn. Sci. 3, 265

an epistemologically authentic approach to student- (1994).

centered inquiry learning, Phys. Rev. Phys. Educ. Res. [14] J. Lave and E. Wenger, Situated Learning: Legitimate

16, 020148 (2020). Peripheral Participation (Cambridge University Press,

[6] K. Bielaczyc and A. Collins, Learning communities in Cambridge, England, 1991).

classrooms: A reconceptualization of educational practice, [15] B. Rogoff, E. Matusov, and C. White, Models of teaching

in Instructional Design Theories and Models, Vol. II, and learning: Participation in a community of learners, in

edited by C. M. Reigeluth (Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Handbook of Education and Human Development, edited

Mahwah, NJ, 1999), Chap. 12, pp. 269–292. by D. R. Olson and N. Torrance (Blackwell, Oxford, UK,

[7] D. M. Desbien, Modeling discourse management com- 1996), Chap. 18, pp. 388–414.

pared to other classroom management styles in university [16] A. Van Heuvelen, Learning to think like a physicist: A

physics, Ph.D. Thesis, Arizona State University, 2002. review of research-based instructional strategies, Am. J.

[8] B. E. Hinrichs, Sharp initial disagreements then consensus Phys. 59, 891 (1991).

in a student led whole-class discussion, in Proceedings of [17] J. Airey and C. Linder, Social semiotics in university

the 2013 Physics Education Research Conference, edited physics education, in Multiple Representations in Physics

by P. V. Engelhardt, A. D. Churukian, and D. L. Jones (AIP, Education, edited by D. F. Treagust, R. Duit, and H. E.

New York, 2014), pp. 181–184. Fisher (Springer Nature, Cham, Switzerland, 2017),

[9] B. G. Glaser and A. L. Strauss, The Discovery of Grounded Chap. 5, pp. 95–122.

Theory (Aldine Publishing Company, Chicago, 1967). [18] E. Etkina, D. T. Brookes, and G. Planinsic, Investigative

[10] B. Nainabasti, D. T. Brookes, Y. Yang, and Y. Lin, Science Learning Environment when Learning Physics

Connection between participation in an Interactive Mirrors Doing Physics (Morgan & Claypool, San Rafael,

Learning Environment and learning through teamwork, CA, 2019).

010103-12You can also read