LITERACY AND CEREBRAL PALSY: FACTORS INFLUENCING LITERACY LEARNING IN A SELF-CONTAINED SETTING

←

→

Page content transcription

If your browser does not render page correctly, please read the page content below

Journal of Reading Behavior

1995, Volume 27, Number 4

LITERACY AND CEREBRAL PALSY: FACTORS INFLUENCING

LITERACY LEARNING IN A SELF-CONTAINED SETTING

Dennis G. Mike

State University of New York at Buffalo

ABSTRACT

This study was conducted as an ethnography of one self-contained classroom at a

school for children with cerebral palsy. The five students were severely multiply

disabled, exhibiting differing degrees and combinations of physical, visual, speech,

hearing, and perceptual impairments. All were diagnosed as having severe read-

ing disabilities. The purpose of the study was to describe and explain those fac-

tors that impacted on literacy learning within this setting. Data collection involved

nonparticipant observation, interviews with teachers and administrators, video-

tape analysis and examination of student records. Factors identified as facilitat-

ing literacy learning were (a) the room as a text-rich environment, (b) the latitude

often given students to govern their own literate behavior, (c) the regularly con-

ducted storyreading sessions, and (d) the constructive use of computers. Factors

identified as hindering literacy learning were (a) restriction of instructional time,

(b) overreliance on individual instruction, and (c) lack of student literate interac-

tion.

Of all the student disabilities that teachers, reading specialists, and educa-

tional researchers encounter, cerebral palsy (CP) is perhaps the most enigmatic.

From a reading perspective, the condition is mysterious in that much of what we

currently know about reading diagnosis, instruction, and remediation simply does

not apply to individuals who are severely multiply disabled. Multiple disabilities

manifest themselves in seemingly random and highly variable ways, making it

difficult, sometimes impossible, to determine the affected person's current level of

functioning and potential. Ten individuals with cerebral palsy may well present 10

radically different profiles of instructional and therapeutic needs. Although some

627

Downloaded from jlr.sagepub.com by guest on July 24, 2015628 Journal of Reading Behavior

individuals are cognitively unimpaired, others are severely mentally retarded. Some

may exhibit normal or near-normal speech, others are totally nonverbal. Some

have limited gross and fine motor control, others have none. Some are ambulatory,

others are confined to electric wheelchairs. Some learn to read and write, others do

not.

The great majority of children severely affected by cerebral palsy do not, in

fact, become literate (Koppenhaver, 1991). This is especially problematic for those

people with severe multiple disabilities since literacy represents their best hope for

participation in the broader society. Participation requires communication. For the

severely speech impaired, communication requires either written language or the

use of communication devices that take the place of human speech, devices most

frequently requiring a literate user (Blackstone & Cassatt-James, 1988;

Koppenhaver, Coleman, Kalman, & Yoder, 1991).

Unfortunately, we know very little of the manner and contexts in which chil-

dren with severe cerebral palsy are taught to read. More positively, in one of the

few studies to link literacy with cerebral palsy (Koppenhaver, Evans, & Yoder,

1991), 22 skilled adult readers with severe physical and/or speech deficits (many of

whom had cerebral palsy) responded to a questionnaire about the manner in which

they acquired literacy. Interestingly, when asked to attribute their success in learn-

ing to read and write, relatively few cited teacher or school support. The support

and high expectations of parents, as well as the subject's own abilities and persis-

tence, were cited far more frequently. When Koppenhaver (1991) examined the

schooling of children with severe speech and physical impairments, he found that,

although substantial allocated instructional time was provided, instructional em-

phasis focused on subskills and words in isolation. Relatively little emphasis was

placed on the reading of connected text. He also found a preponderance of one-to-

one teacher-student contact, to the exclusion of grouped activity. A related study of

learners with similar disability profiles (Koppenhaver, Abraham, & Yoder, 1993)

focused on writing instruction. The researchers concluded that teachers maintained

a great deal of control over the composition process, thereby limiting opportunities

for student text production.

The current study furnishes additional information about literacy learning in

the classroom. I provide here an instructional and cultural picture of one class

within a Cerebral Palsy Center, focusing on institutional factors that influence

literacy learning within the class.

METHOD

This study was conducted as an ethnography of one class at the Center for the

Treatment of Individuals with Cerebral Palsy (CTICP), a facility specifically de-

signed to meet the educational and therapeutic needs of those with cerebral palsy.

Downloaded from jlr.sagepub.com by guest on July 24, 2015Literacy and Cerebral Palsy 629

It offered a variety of services, including speech, occupational, and physical thera-

pies, as well as psychological, dental, medical, and educational services. The Cen-

ter School, in which this study occurred, subscribed to a team approach. For each

class, the team consisted of the teacher, the teacher's assistant, and a nurse, as well

as speech, occupational, and physical therapists. Under the coordination of the

teacher, the team determined the educational and therapeutic program for each

child. I had worked there as a curriculum developer and was already familiar with

the center's structure and with many of its staff. This familiarity was helpful in

gaining institutional permission to conduct the study and in selecting a classroom.

However, my knowledge of the setting also represented a methodological disad-

vantage in that I was unable to enter the site free of preconceptions.

An ethnographic methodology was selected because of the highly exploratory

and descriptive nature of the study. The primary data source was fieldnotes derived

from nonparticipant observation of the school setting. In addition, videotape and

interview data were collected and analyzed, as were student records. Data were

collected over a 6-month period in 1987.

Selection of and Access to the Classroom

The classroom selected for study was viewed by school administrators as one

in which literacy was particularly well promoted. The teacher heading this class-

room was approached and agreed to allow her class to serve as the setting for the

study. Permission was obtained from the students' parents and other adult partici-

pants.

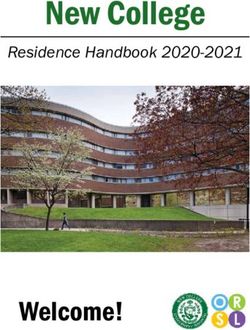

The class was housed in a room at the junction of two main hallways. For a

room that had to accommodate several wheelchairs, it was a small room, measur-

ing 17' X 24.5'. In a square space, this might have been tenable. However, as shown

in Figure 1, the room was L-shaped, which made it difficult for students to move

about. Wheelchair traffic jams were a regular occurrence, particularly during ar-

rivals, departures, and transitions between activities. The size and configuration of

the room also made it difficult to position students for academic activities.

The room was a literacy-rich environment in the sense that a great deal of

textual material was displayed on the walls. Individual student schedules, a larger

class schedule and a wall calendar were posted. The students referred to these

regularly. Posters and examples of exemplary student work were also displayed.

Books and magazines were kept on shelves at a height accessible to the students.

The Students

During the data collection period, five students, ages 12 to 14, were assigned

to the classroom. Three were boys and two were girls. The students each had the

following characteristics in common:

Downloaded from jlr.sagepub.com by guest on July 24, 2015630 Journal of Reading Behavior

1. Each student had cerebral palsy. The range of physical involvement extended

from moderate to practically total. Four of the students were confined to wheel-

chairs. One student was able to walk, but did so with a severely affected gait.

Fine motor control was severely affected in each of the children.

2. Each student was classified as speech impaired. One student was intelligible

under most conditions. Three were described in their IEP's as being unintelli-

gible, in that they could only be understood by a listener highly familiar with

their speech. One student was totally nonverbal.

3. As reflected in their IEP's, literacy was considered a viable goal for each stu-

dent. However, each was reading well below expected levels for their ages. The

teachers reported that none of the students could comprehend connected text

beyond the second-grade level. Two of the students had sight-word vocabularies

of less than 100 words.

4. Each student was described by the teachers as being "classically" learning dis-

abled (their expression), even though this formal classification was precluded

due to the presence of cerebral palsy. Nevertheless, each student's IEP reflected

the presence of severe perceptual difficulties. In the case of two students, the

IEP's also indicated mild mental retardation.

The Teachers

The classroom was served by two teaching professionals: a teacher and a

teacher's assistant. Both were in their late 20s. The teacher, Lauren, was in the

BoMm Bowd 2

The Classroom

ComtoUr Computer IPrinter I

Figure 1. Layout of the classroom.

Downloaded from jlr.sagepub.com by guest on July 24, 2015Literacy and Cerebral Palsy 631

process of acquiring her Master's degree in special education from a small local

college. Her undergraduate degree was also in special education. She described her

formal training in reading and writing instruction as "restricted" and reported that

courses dealing with literacy were not emphasized in either her undergraduate or

graduate programs. At the time of the study, Lauren described her approach to

reading instruction as being in transition. She reported that she was moving away

from a subskills, decoding approach and moving toward an emphasis on the read-

ing of connected text. She had recently begun to regularly schedule storyreading in

class and found it to be a valuable experience.

The teacher's assistant, Linda, was a Master's level intern completing her

studies at a local college. Linda's educational background revealed approximately

the same amount of formal training in literacy instruction as that of the teacher;

she had taken one course in reading instruction and one in writing instruction as

an undergraduate. As a teacher's assistant, her role was to implement instruction

under the teacher's supervision. She was also given the responsibility of planning

the reading and math programs for two students. The teacher reported that she

trusted Linda and respected her instructional sensitivity.

Daily Routine

The teachers arrived at the classroom between 8:00 and 8:15 a.m. The stu-

dents usually arrived between 8:30 and 9:00. Their arrival times were staggered

due to the fact that each student lived in a different district and had to be trans-

ported by a different carrier.

The instructional day was scheduled to begin at 9:00. However, more often

than not, students were still in the process of getting settled at 9:15. If a student

arrived late, the beginning of the academic day would be delayed still further as the

teachers attended to that student's particular needs. The morning's instructional

time was blocked into half-hour periods. These ended at 11:30, when students

would go to lunch.

The students ate lunch at the Center cafeteria until 12:30 and arrived back at

the classroom between 12:35 and 1:40. The loosely structured period between 12:30

and 1:30 was referred to as "free time." Students were generally taken out of their

wheelchairs and positioned on the floor. They did whatever they wanted to for

20-30 minutes. The remaining half-hour was reserved for storyreading. Lauren sat

on the floor to read, while the students either sat or were positioned on wedges

around her.

Following free time, the students were repositioned in their wheelchairs for

the afternoon instructional period, extending from 1:30 to 2:30. As with the morn-

ing academic session, this period was organized into half-hour blocks of time.

At 2:30, the students began their preparations for the trip home. Notes to the

parents and the occasional homework assignment were packed into the children's

knapsacks.

Downloaded from jlr.sagepub.com by guest on July 24, 2015632 Journal of Reading Behavior

Observation

Observational sessions generally lasted from 30 to 60 minutes. Sessions were

conducted during the entire school day, including lunch, gym, and arrival/depar-

ture times. In total, 63.5 hours of class activity were observed. Fieldnotes were

recorded longhand and later elaborated upon in fuller narrative form on the com-

puter. In addition, a separate file was kept of my own insights regarding the evolv-

ing methodology.

Establishing The Foci of Observation

In the first month of data collection, the focus of observation was intentionally

kept broad, as is consistent with an ethnographic mindset. A precise focus for

observation had not been selected beforehand; I had not yet decided which aspect

of the class would be specifically studied. Because this was to be a study of reading

behavior, it was clear from the start that literacy and literacy events would be ob-

served and recorded. However, no particular person or facet of classroom operation

was singled out for special observational attention.

After one month of observation (16 hours), I reviewed the fieldnotes for trends

and repetitive themes. By that time, I had noted one aspect of the classroom culture

as being particularly evident: although the students interacted a great deal with the

adults in the room, they rarely interacted with each other. Review of the first month's

data indicated that fewer than 5% of all classroom interactions had occurred be-

tween students. Student interactions involving literacy were, quite naturally, rarer

still: only one was noted during the entire first month of observation. This lack of

student literate interaction seemed striking. Consequently, I narrowed the focus of

observation to emphasize student-to-student interactions, most especially those in-

volving literacy.

In what Spindler (1982) calls the hypothesis-testing phase of ethnography, the

second month's fieldnotes were continuously reviewed for occurrences of student-

to-student interaction. These data confirmed that student-to-student contact was,

indeed, a relatively rare occurrence in the classroom. Furthermore, as during the

first month, few of these interactions involved literacy. I also found that, on the few

occasions when literate student interaction had occurred, technology was generally

involved in some way. For this reason, I adjusted the focus of observation to reflect

the presence of technology. For the remainder of the study, the focus of observation

remained consistent.

For one out of five observational sessions, I reinstated the original broad focus

of observation. During these sessions, I made equal note of all interactions, as

opposed to focusing primarily on student-to-student contact. Broadening the focus

of observation provided a measure of the proportion of student-to-student interac-

tions to all classroom interactions. This was needed to confirm that the dearth of

Downloaded from jlr.sagepub.com by guest on July 24, 2015Literacy and Cerebral Palsy 633

student interaction was actually a normal feature of the classroom culture and not

just an anomaly.

Establishment of an observational focus was paralleled by the development of

a coding system. I established a tentative system at the end of the first month of

observation and refined it over the course of the next 6 weeks. During this period,

if an observed event failed to fit into the existing coding system, the scheme was

revised to accommodate the new set of circumstances. Adjustments such as these

continued until all episodes were codeable.

The episode was used as the conceptual unit for fieldnote analysis. For the

purposes of this study, an episode was conceptualized as a stable action or sequence

of actions involving one or more persons. The duration of an episode was

operationalized as the period during which participants and/or activities remained

consistent and stable. For a full description of the coding scheme, see Mike (1991).

For the sake of brevity, I will only note here that each coded episode included

reference to the following factors:

1. Whether the episode had involved a student literacy event;

2. if so, whether the student was prompted to engage in the literate behavior or

whether the behavior had occurred independently;

3. the nature of the literacy event that had occurred (there were seven different

categories based on observed classroom behavior);

4. whether an interaction between classroom participants had occurred during the

episode and, if so, between whom;

5. whether technology had played a role in the episode and, if so, which classroom

device;

6. whether the episode had occurred during planned instructional or

noninstructional time.

The construct of literacy event was taken from the description used by Ander-

son, Teale, and Estrada (1980). They define a literacy event as "any action se-

quence, involving one or more persons, in which the production and/or

comprehension of print plays a role." Because all the students in the present study

were emerging readers, I expanded this description to include the attempted com-

prehension, as well as actually demonstrated comprehension. This was problem-

atic. Because of verbal and physical impairments, these children did not give off

the same behavioral cues as do able-bodied children. Despite this, a conservative

approach to the coding of literacy events was employed, requiring a tangible indi-

cation that a literacy event had occurred before it could be coded as such.

Interviews

Throughout the data collection period, several open-ended interviews were

conducted. These were transcribed and analyzed either to confirm or disconfirm

Downloaded from jlr.sagepub.com by guest on July 24, 2015634 Journal of Reading Behavior

earlier assumptions drawn from observational data. Interviews were conducted with

the classroom teacher, her assistant, the principal, and the assistant principal.

Initially, I had intended to interview students, as well. However, as the study

progressed, it became clear to me that the children's verbal disabilities precluded

this. Because of the students' communication difficulties, teachers recommended

against student interviews, as did the speech therapists.

Videotaping

Twenty hours of classroom activity were recorded on videotape. As with inter-

view data, the primary function of the videotapes was to provide an additional data

source to be used to either confirm or disconfirm observational findings, permit-

ting repeatably analyzable detail. This was especially helpful in examining student

computer use.

Examination of Student Records

Student records were reviewed to provide as full a sense of each student as

possible. In gaining permission from parents for the examination of student records,

assurance was given that only educational records would be reviewed. Consent

from four of the five sets of parents was received. The official records reviewed

included the Individualized Education Plan (IEP), which expressed the student's

current level of functioning and goals for the current school year. Statements of

current functioning levels were helpful in that they provided a summary of perti-

nent medical and psychosocial information. The statements of goals and objectives

were revealing in that they provided a sense of the teacher's attitudes about student

potential, as well as the ongoing instructional plan. Past IEP's were also examined.

FACTORS THAT PROMOTED LITERACY LEARNING IN THE

CLASSROOM

Within the context described above, several factors were identified as provid-

ing support for student literate development. These are (a) the room as a text-rich

environment, (b) the latitude often given students to determine their own literate

behavior, (c) regularly conducted storyreading sessions, and (d) the constructive

use of computers.

The Room as a Text-Rich Environment

Much material was posted on the walls, including a lunch menu and student

schedules. Students were encouraged to refer to this material and they frequently

did so. When students had questions about their activity schedules, teachers would

respond by telling them to read the schedules for themselves. Eight percent of the

observed literacy events involved student reference to the menu and schedules.

Downloaded from jlr.sagepub.com by guest on July 24, 2015Literacy and Cerebral Palsy 635

Student Decision-Making

The students were given regular opportunity to make decisions regarding their

own literate behavior. During the free-time period following lunch, they were al-

lowed to do what they wanted. Often, they chose to look through the magazines

kept in the room. In addition to free time, there was one academic period of 30

minutes (referred to by participants as the independent period), during which stu-

dents could select any academic activity. At these times, students could either en-

gage in literate behavior or not, although they were encouraged by the teachers to

do so. If they chose to read, they were allowed to self-select reading material. This

feature of the classroom environment is especially noteworthy in light of the con-

tention that the severely disabled are rarely allowed to make meaningful decisions

for themselves (Wolfensberger, 1991).

Storyreading

During her interview, the teacher said that the after-lunch storyreading ses-

sions were intended to promote literacy as a recreational activity. That the children

enjoyed this activity is evidenced by the consistency with which they requested it.

Their interest and engagement is illustrated by the following fieldnote:

Lauren then closes the book and says, "We'd better stop now; it's late. They're all

going to drown." The class responds with groans and negative sounds. Bob says,

"Please keep going." Lauren says, "I'm only kidding" and continues reading. The

text describes the oncoming flood. It includes mention of "two waves, one of

them white spotted with black and the other one brown." Lauren stops and asks

the class what the book means by this. She asks what the wave of white, spotted

with brown, would be. Shirley answers, "Pigs" and Lauren says, "Right. Now

what is the other wave, the brown one?"

Children were also exposed to books at other times of the school day. A student's

reading lesson would sometimes involve the reading of a storybook by the teacher.

Students sometimes chose storyreading as a free-time activity, especially if an aide

or teacher was available to read aloud to them. This is not to suggest that the

reading of connected text was an emphasis of the students' instructional reading

programs. This was not the case; subskill and sight-word instruction (usually mani-

fested through worksheets) played a much larger role, constituting over 90% of

observed instructional activity [for a complete discussion of the nature and occur-

rence of classroom instructional activities, see Mike (1991)]. Nevertheless, the read-

ing of books and stories was part of the classroom routine.

The Use of Computers

In interviews, the teachers repeatedly stressed the high motivation that com-

puters held for these students. Explanation of this affinity lies largely in the simple

fact that, in a world where they could control precious little, these students were

capable of controlling the computer (when provided with alternative input devices).

Downloaded from jlr.sagepub.com by guest on July 24, 2015636 Journal of Reading Behavior

Compared to able-bodied children, their physical facility with computers was greatly

limited. However, the computer itself was not likely to complain if a child using a

headpointer took 5 minutes to write a five-word sentence. The computer provided

an infinitely patient partner for both work and leisure activities. Regardless of the

degree of each child's aggregate disabilities, a program could be found that would

allow that child to perform actions that would, without the computer, be impos-

sible.

When asked to explain the children's affinity for computers, Lauren responded:

They're toys, but they're things that older people use, and so they [the children]

see it as, you know, something even their parents don't know how to use. I've had

parents come in and say, "How does he know how to use that? I don't know how

to do that." Bob's mother really was freaking out. She thought it was great. "Look

how fast he is. He knows what to do." You know, that's a great feeling when your

parents don't know about this and you do.

Although students were rarely given the opportunity to work together on the

computer during the instructional periods, they interacted on several occasions

during noninstructional time. In interviews, both the teacher and the teacher's

assistant confirmed observational data regarding the prevalence of computer in-

volvement during free-time student interactions. In most of these instances, one

student would be engaged in independent computer use and another student would

approach. Both students would then coactively use the computer or communicate

about it in some way. Frequently, one student helped another with the intricacies of

a program. Such interaction had the advantage of not being solely dependent on

verbal communication. Instead, one student could simply demonstrate how to ma-

nipulate a game or word processor.

An example of this is when Keith approached while Bob was playing a com-

puterized phonics game. Keith initiated the contact by asking, "What are you do-

ing, Bob?" Bob responded pointing to the monitor and verbalizing. Although his

response was unintelligible to me, Keith apparently echoed Bob's response by say-

ing "Winter Games," as he nodded knowingly. For approximately 2 minutes, Keith

watched as Bob played the game, repeating the letter sounds that comprised the

answers, while Bob accessed the appropriate letter with his headpointer. Once,

when Bob hit the incorrect letter, Keith said, "No" and reached over to hit the

correct letter-response. Bob then nodded in response. This illustrates that the stu-

dents were able to communicate about the computer and that the resultant interac-

tions often involved literacy. Fully two-thirds of all noninstructional student

interactions that involved literacy also involved technology [either a computer or

an augmentative communication device; for a complete discussion of augmenta-

tive communication devices, see Blackstone and Cassatt-James (1988)].

There was little instructional use of drill-and-practice software, unusual for a

special education setting (Woodward, 1992). Although the teacher had several drill-

and-practice programs, she did not assign them:

Downloaded from jlr.sagepub.com by guest on July 24, 2015Literacy and Cerebral Palsy 637

Lauren: One reason is . . . it's boring. We've got some that talk [i.e., make use of

the voice synthesizer] and they're not that much fun. I'd rather have them [the

students] like to use the computer than to hate it.

The most prevalent use of the computer during instructional periods was for

word processing. During noninstructional periods, the class frequently used pro-

grams such as Print Shop to generate cards and banners, especially near a holiday

or a class member's birthday:

Lauren: I liked things that were a lot of fun. Because I was there, it didn't matter

how complicated it was. Print Shop was a good example. It was complicated, but

it was a lot of fun to make a big banner that you could bring home and show

somebody.

In addition to being fun, the creation of signs and banners involved both read-

ing and writing. Eleven percent of all student literacy events observed during

noninstructional time reflected the creation of cards and banners.

In total (instructional and noninstructional time), technology was involved in

27% of all student literacy events. The computer, then, was an important part of

the literacy education of these children.

FACTORS THAT INHIBITED LITERACY LEARNING

IN THE CLASSROOM

In my opinion, there were three factors that impacted negatively on literacy

learning in this classroom: (a) restriction of instructional time, (b) overreliance on

individual instruction, and (c) lack of student literate interaction. The third was

partially a consequence of the first two.

Restriction of Instructional Time

In this setting, there was relatively little time available for literacy instruction.

In total, 3'/2 hours per day were allocated for academics. However, activities other

than academics were also scheduled during this time, most notably the various

therapies that the students received. (Daily provision of at least one therapy for

each student was considered essential because the Center generated revenue by

billing Medicaid or private insurance companies for therapies provided. The Cen-

ter could submit a "billable" for only one therapy per student per day, so the Center's

administration mandated that these should be spread out throughout the week.) In

addition to the therapies themselves, there was the need to schedule everything else

around the therapies, constantly disrupting the class. If one of the therapists was

absent or could not meet with a child, the teacher had to drop everything to arrange

another therapy for that child. If one student's schedule was changed, other stu-

dents' schedules would likewise be affected.

Downloaded from jlr.sagepub.com by guest on July 24, 2015638 Journal of Reading Behavior

Once therapies were accounted for, 2Vi hours were available for academics.

Out of this time, however, gym, swimming, medical visitations, assemblies, and

the occasional birthday party were also scheduled. What remained was one aca-

demic block for literacy instruction: 30 minutes per day, less than half the allocated

time observed by Koppenhaver (1991) in an observational study of similarly dis-

abled students.

Time for instruction was compromised still further by the need to manage

transitions between activities. In addition, there was a need to precisely position

students for certain classroom activities. Proper positioning was especially neces-

sary for activities involving reading and writing. The students' visual and percep-

tual impairments made it important that reading material be placed at an optimal

distance and angle. Positioning for writing was also highly problematic. The stu-

dents needed adaptive equipment that was often difficult to fabricate and adjust,

processes frequently requiring the input of several therapists.

Teachers often were forced to interrupt one student's lesson to attend to the

needs of another student, with many of these disruptions due largely to institu-

tional factors. For example, the small size of the room led to situations that, taken

in total throughout the day, took a great deal of time to resolve. The room was

simply too small to accommodate four wheelchairs moving about at the same time.

Overreliance on Individual Instruction

Instruction provided in the classroom was overwhelmingly teacher-directed

activity in which the student either worked alone or with a teacher. This was due to

the teacher's attitude regarding classroom structure. On one hand, Lauren expressed

a favorable attitude toward grouping, saying "It's normal, part of normal develop-

ment—working in a group is normal." On the other hand, she maintained that

planning group instruction within this particular classroom was a difficult and

frustrating task, citing the wide range of student ability levels and the uncertainties

of student schedules as impediments to grouped instruction. Scheduling uncer-

tainty was due largely to the billables policy and the small size of the room. That is,

a larger room would have facilitated grouped instruction by making it possible to

administer billable therapies within the classroom. This, in turn, would have made

it easier for the teacher to adapt to changing student schedules. A larger room also

would have accommodated grouped instruction by making it possible for students

in wheelchairs to gather together.

To sum up, this classroom was a place where individual seatwork took prece-

dence over group instruction, disturbing because children do not learn well in iso-

lation. Learning, most especially language learning, is a socially elaborated process

(Au, 1980; Bloome & Green, 1984; Ewoldt, 1985; Fishman, 1988; Kantor, 1992;

Soderbergh, 1985; Vygotsky, 1978), one in which these children are not given the

opportunity to fully participate.

Downloaded from jlr.sagepub.com by guest on July 24, 2015Literacy and Cerebral Palsy 639

Lack of Student Literate Interaction

Severe speech impairments made it difficult for these children to communi-

cate with each other. Despite this, the students did interact occasionally. The fol-

lowing fieldnote relates one such situation:

Jon has walked on his knees to the AHTalk, situated on table 3. All of a

sudden, Linda's voice calling "Bob, Bob, Bob" is heard through the room. (It is

Linda's voice that has been programmed into the AHTalk.) "Bob" is repeated at

least seven times, and each time Bob laughs. Everyone in the room is now watch-

ing the performance, including Keith. The AHTalk cries, "Linda, Linda" and Linda

answers "What? What?" each time her name is called. Jon is getting more and

more excited, especially when Linda responds. He starts pushing a few buttons

indiscriminately and the machine answers him each time. He asks Linda, "Where's

'home'?", meaning the key for the word "home." Linda echoes, "Where's 'home'?

Look for it." Jon does and, after perhaps five seconds, the machine says "home."

Jon goes back to pushing buttons, seemingly indiscriminately (but I'm not so sure

of that now) and Keith walks over to join him.

The machine says, "Liza," then "Liza" again. Then, "I like Liza." Linda

says, "That's a nice sentence." Liza, who is smiling broadly, apparently thinks so,

too . . . Keith says, "Let me do that!" and Jon, talking through the machine,

immediately answers, "No. No." Keith points to a word . . . Jon goes (through the

machine) "I want pizza." ("I want" is one box. "Pizza" is another.) . . . Keith

picks up Jon's hand by the wrist and directs his finger to the box. "Linda" comes

out several more times, then "no." Again, Keith guides Jon's hand; Jon doesn't

seem to mind. The machine says, "Can I have a drink please?" And both Jon and

Keith stop to look at Linda. Linda makes no move or sign of comprehension.

Keith directs Jon's hand to "yes" and then says "yes." . . . Keith again directs

Jon's hand and the words, "Can I have a drink?" are heard.... Linda says, "Oh,

do you really want one?" Both Keith and Jon say yes.

This note of an extemporaneous incident contains four separate peer interac-

tions, all of which involved literacy. Jon's performance during this incident is es-

pecially notable. Without practice, he was able to apply the literacy skills necessary

to effectively operate an unfamiliar augmentative communication device. Follow-

ing the incident, Linda expressed shock (her word) that he was able to do so.

Although the students were clearly capable of engaging each other in ways

that involved literacy, they only rarely did so. During both instructional and

noninstructional periods, fewer than 1% of the classroom interactions were found

to involve student-to-student literate contact. Students were only rarely provided

with opportunities to do so. The teacher's assistant believed that a greater effort

should have been made to foster student literate interaction:

Linda: Personally, I think we need to do more grouping . . . you can set up many,

many ways of doing things that you can do in a group, and you can do it where

everybody's at a different level, and that's okay.. . . There are a lot of different

ways to do it, so that you know, Liza's input is one thing, and Shirley's is another.

Keith is reading the directions and has no idea what he is reading, but Shirley

Downloaded from jlr.sagepub.com by guest on July 24, 2015640 Journal of Reading Behavior

might be interpreting, and explaining them to everybody else because her lan-

guage is clear and everybody can understand.

When asked why more effort was not made to bring students together for read-

ing and writing, both teachers cited difficulties influenced by the institutional fac-

tors described above: the difficulty of coordinating student therapy schedules and

the small size of the room. Both teachers maintained that, had these issues been

resolved, planning for student interaction would have been a far more practical

consideration.

CONCLUDING COMMENTS

The children who attended the classroom described in this study were all se-

verely disabled. Faced with the imposing task of learning to read and write, they

were already seriously disadvantaged. It stands to reason that we would seek to

provide such children with an educational environment that could compensate for

their disabilities to whatever extent possible. The Center was represented as being

such a setting; its informational brochure stated that "meeting the unique educa-

tional needs of [multiply disabled] students in an environment which enhances

their optimal development is the basis of our Educational Services Division." How-

ever, although some positive factors were noted, the classroom studied was not

nearly as conducive to literacy learning as might have been the case. In particular,

the small size of the room and the unpredictability of student scheduling (caused

by the need to accommodate a problematic therapy schedule) were identified as

impediments to literacy learning. These institutional factors had a direct and detri-

mental impact on the time available for instruction, as well as having an indirect

impact on the teacher's own instructional decision making, particularly with re-

spect to grouping practices.

The argument most commonly advanced against inclusion programs is that

public schools are not equipped to meet the special needs of disabled children

(Fuchs & Fuchs, 1993; Reganick, 1993; Ysseldyke, 1993). However, the self-con-

tained setting described in this study, specifically designed for children with cere-

bral palsy, was also ill-equipped for this purpose. If segregated institutions claim to

promote the learning of children with multiple disabilities, they should be struc-

tured accordingly. This study suggests the following factors as being prerequisite.

First, the room must be large enough to easily accommodate wheelchair traffic,

thereby reducing time needed for students to transition between activities. Second,

whenever possible, therapies should be provided within the classroom in order to

promote integration between therapies and academics, as well as to save time oth-

erwise spent transporting students to therapy areas. Third, the classroom should

contain a bathroom, again in order to save time otherwise spent transporting stu-

dents. Although these factors may seem far removed from actual instructional prac-

Downloaded from jlr.sagepub.com by guest on July 24, 2015Literacy and Cerebral Palsy 641

tice, this study has demonstrated their impact on all aspects of classroom opera-

tion, including instruction. As with Maslow's (1967) hierarchy of needs, the most

basic structural considerations must be met before the "higher order" business of

instruction can be fully attended to. Had the classroom studied been structured

accordingly, the results of this research would likely have been quite different:

more time available for literacy instruction and fewer constraints placed on in-

structional planning.

REFERENCES

Abraham, L. M., & Koppenhaver, D. A. (1993, May). Social and academic organization of composition

lessons for AAC users. Paper presented at the Symposium on Research and Child Language Disor-

ders, Madison, WI.

Anderson, A. B., Teale, W. B., & Estrada, E. (1980). Low-income children's preschool literacy experi-

ences: Some naturalistic observations. The Quarterly Newsletter of the Laboratory of Comparative

Human Cognition, 2, 59-65.

Au, K. H. (1980). On participation structures in reading lessons. Anthropology and Education Quarterly,

11, 91-115.

Blackstone, S. W., & Cassatt-James, E. L. (1988). Augmentative communication. In N. J. Lass, L. V.

McReynolds, J. L. Northern, & D. E. Yoder (Eds.), Handbook of speech-language pathology and

audiology (pp. 986-1013). Toronto: B. C. Decker.

Bloome, D., & Green, J. (1984). Directions in the sociolinguistic study of reading. In P. D. Pearson, R.

Barr, M. L. Kamil, & P. B. Mosenthal (Eds.), Handbook of reading research (pp. 395-421). New

York: Longman.

Ewoldt, C. (1985). A descriptive study of developing literacy of young hearing-impaired children. Volta

Review, 87(5), 109-126.

Fishman, A. R. (1988). Amish Literacy: What and how it means. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann.

Fuchs, D., & Fuchs, L. S. (1993). Inclusive schools movement and the radicalization of special educa-

tion reform. Bethesda, MD: National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. (ERIC

Document Reproduction Service No. ED 364 046)

Kantor, R. (1992). Diverse paths to literacy in a preschool classroom: A sociocultural perspective. Reading

Research Quarterly, 27, 184-201.

Koppenhaver, D. A. (1991). A descriptive analysis of classroom literacy instruction provided to chil-

dren with severe speech and physical impairments. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, University of

North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

Koppenhaver, D. A., Coleman, P. P., Kalman, S., & Yoder, D. E. (1991). The implication of emergent

literacy research for children with developmental disabilities. American Journal of Speech-Lan-

guage Pathology, 1, 38-44.

Koppenhaver, D. A., Evans, D. A., & Yoder, D. E. (1991). Childhood reading and writing experiences of

literate adults with severe speech and motor impairments. Augmentative and Adaptive Communica-

tion, 7, 21-35.

Maslow, A. H. (1967). Self-actualization and beyond. In J. F. T. Bugental (Ed.), Challenges of humanistic

psychology (pp. 279-286). New York: McGraw-Hill.

Mike, D. G. (1991). Literacy and the multiply disabled: An ethnography of classroom interaction. Disser-

tation Abstracts International, 53(02), 454A. (University Microfilms No. AAI92-18319)

Reganick, K. A. (1993). Full inclusion: Analysis of a controversial issue. (ERIC Document Reproduc-

tion Service No. ED 366 145)

Downloaded from jlr.sagepub.com by guest on July 24, 2015642 Journal of Reading Behavior

Soderbergh, R. (1985). Early reading with deaf children. Prospects, 15, 77-85.

Spindler, G. (Ed.). (1982). Doing the ethnography of schooling: Educational anthropology in action.

New York: Holt, Rinehart & Winston.

Vygotsky, L. S. (1978). Mind in society: The development of higher psychological processes. Cam-

bridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Wolfensberger, W. (1991). A brief overview of social role valorization as high-order construct for struc-

turing human services. Syracuse: Syracuse University Training Institute.

Woodward, J. (1992). Textbooks, technology, and the public school curricula: Identifying emerging

issues and trends in technology for special education. Washington, DC: COSMOS Corporation.

(ERIC Document Reproduction Service No. ED 350 760)

Ysseldyke, J. E. (1993). National goals, national standards, national test: Concerns for all (not virtu-

ally all) students with disabilities? (Synthesis Report 11). Washington, DC: Special Education Pro-

grams. (ERIC Document Reproduction Service No. ED 366 168)

AUTHOR NOTE

This study was conducted as a dissertation through the Department of Read-

ing, State University of New York at Albany. I am indebted to committee members

Dr. Debi May, Dr. Sean Walmsley, and Dr. Rose Marie Weber. I am especially

indebted to committee chair, Dr. Peter Johnston, who guided the investigation, as

well as offering feedback on this article. I also acknowledge the support of Dr.

Richard Allington and Dr. Valerie Janesick.

Correspondence concerning this article should be addressed to Dennis G. Mike,

at the Department of Learning and Instruction, 593 Baldy Hall, State University of

New York at Buffalo, Buffalo, NY 14260. Electronic mail may be sent via

INTERNET to "insmiked@ubvms.cc.buffalo.edu".

Manuscript received: October 8, 1994

Revision requested: November 14, 1994

Revision received: January 15, 1994

Accepted for publication: February 3, 1995

Downloaded from jlr.sagepub.com by guest on July 24, 2015You can also read