Green Revolving Funds: An Introductory Guide to Implementation & Management

←

→

Page content transcription

If your browser does not render page correctly, please read the page content below

A co-publication of the Sustainable Endowments Institute &

the Association for the Advancement of Sustainability in Higher Education

Green Revolving Funds:

An Introductory Guide to Implementation & Management

Joe Indvik, ICF International

Rob Foley, Sustainable Endowments Institute

Mark Orlowski, Sustainable Endowments Institute

University of British Columbia, Earth Science Building, Perkins and WillPartners

A M E RICA N C OLL EGE & U N IVERS ITY

P RE S I D E N TS’ C LI M AT E C OM M I T M E N T

An Introductory Guide to GRF Implementation & Management

Second Nature

Education for Sustainability

Funders

Prepared by ICF International for the Sustainable Endowments Institute

© 2013 Sustainable Endowments Institute and the Association for the Advancement of Sustainability in Higher Education

Sustainable Endowments Institute | 45 Mt. Auburn Street, Cambridge, MA 02138 • 617.528.0010

www.endowmentinstitute.org • info@endowmentinstitute.org

Published January, 2013

2Table of Contents

Executive Summary Pg. 4

Chapter 1 What is a Green Revolving Fund? Pg. 6

Chapter 2 The Anatomy of a Green Revolving Fund Pg. 9

An Introductory Guide to GRF Implementation & Management

2.1 Seed capital

2.2 Accounting systems

2.3 Fund oversight

2.4 Fund operations and project selection

2.5 Project criteria

2.6 Measuring savings

2.7 Long-term strategy

Chapter 3 10 Steps to a Successful GRF Pg. 16

Step 1: Do your homework

Step 2: Select your model

Step 3: Assess opportunity and run the numbers

Step 4: Build buy-in

Step 5: Secure seed capital

Step 6: Establish financial flows

Step 7: Launch and manage

Step 8: Implement projects

Step 9: Track, analyze, and assess performance

Step 10: Optimize and improve

Chapter 4 Common Obstacles to GRF Implementation Pg. 23

Chapter 5 The Billion Dollar Green Challenge Pg. 25

About the Authors & Acknowledgements Pg. 27

3Executive Summary

The goal of this introductory implementation guide

is to provide practical guidance for designing,

implementing, and managing a green revolving fund

(GRF) at a college, university, or other institution.

An Introductory Guide to GRF Implementation & Management

The GRF model is widespread in higher education,

with at least 79 funds in operation in North America

representing over $111 million in committed

investment as of late 2012. GRFs have proven their

ability to reduce operating costs and environmental

impact while promoting education and engaging

stakeholders. The number of GRFs in operation has

increased 60 percent since 2010 and 15-fold in the University of Colorado Boulder, Center for Innovation and Creativity

last decade (see Greening the Bottom Line 2012 report).

The Guide is informed by data and insights from

In 2011, the Sustainable Endowments Institute (SEI)

schools that have already incorporated GRFs into

launched The Billion Dollar Green Challenge, an

their campus operations. It includes information

initiative that encourages colleges, universities, and

from (1) interviews with dozens of stakeholders

other nonprofit institutions to invest in their own

representing institutions that vary in size, setting,

GRFs. As part of this initiative, SEI has researched

and wealth; (2) research conducted by SEI, AASHE

GRFs at a wide range of institutions and has

and other organizations; (3) and the direct experience

developed a suite of tools and resources to support

of its authors in implementing and advising on GRFs

GRF adoption (see Chapter 5: The Billion Dollar

at a variety of institutions.

Green Challenge).

Anyone interested in establishing, managing, or

However, it can be difficult to establish and

researching GRFs will benefit from this Guide.

manage an effective GRF. There is a need for a

While the Guide is targeted at higher education,

guiding document that taps into the expertise

its principles can be applied to many other sectors,

of presidents, administrators, facility managers,

including K-12 schools, healthcare institutions,

sustainability directors, students, consultants, and

municipalities, and private companies.

other stakeholders with GRF experience to establish

best practices. This Guide—a co-publication of This introductory guide is not intended as a technical

SEI and the Association for the Advancement of guidance document, but rather as a high-level

Sustainability in Higher Education (AASHE)—is overview of GRF establishment and management. A

intended to fulfill that need. more detailed comprehensive guide will be available

in spring 2013. Key chapters are summarized below.

4Chapter 1: What is a Green Chapter 3: 10 Steps to a Successful

Revolving Fund? Green Revolving Fund

Chapter 1 introduces readers to the green revolving Chapter 3 of this Guide includes a step-by-step

fund (GRF) concept. A GRF is an internal fund that roadmap for how to design, implement, and manage

provides financing to parties within an organization a successful GRF. A few key themes are present

to implement energy efficiency, renewable energy, throughout all 10 steps. First, use existing research

and other sustainability projects that generate and strong data analysis to inform your GRF strategy

cost-savings. These savings are tracked and used when building the case for the fund, setting up its

to replenish the fund for the next round of green structure, and identifying and selecting projects.

investments, thus establishing a sustainable funding Second, dedicate time and resources to undertaking

cycle while cutting operating costs and reducing a thorough stakeholder engagement process, both to

An Introductory Guide to GRF Implementation & Management

environmental impact. build buy-in and to leverage the insights of experts

There are several advantages of GRFs that go beyond on your campus to improve the fund. Third, tailor the

one-time investments. Revolving funds build the mission, structure, and management of your fund to

business case for sustainability, engage and educate the unique characteristics of your institution.

the campus community, convey reputational benefits, Chapter 4: Common Obstacles

and create fundraising opportunities in a way that to Green Revolving Fund

conventional investments do not. GRFs are being

successfully employed by a wide range of schools—

Implementation

including public and private institutions with varying Several obstacles are often encountered during

sizes, locations, strategic priorities, and levels of GRF development and management. Chapter 4

endowment wealth. These funds regularly achieve of this Guide outlines those issues and offers best

high financial returns, with a median return on practices for overcoming them based on insights

investment of 28 percent annually. from GRF leaders. To avoid financial obstacles,

gain a comprehensive understanding of your

Chapter 2: The Anatomy of a Green institution’s accounting system, incentive structure,

Revolving Fund and sustainability investment portfolio to inform the

design of your fund. To overcome administrative and

No two GRFs are the same. Chapter 2 of this

political obstacles, build a strong business case for the

Guide discusses how each component of a GRF can

fund using performance forecasts and comparisons

be designed, customized, and optimized for your

with peer institutions.

institution. Sources of GRF seed capital are diverse

and include administrative budgets, endowment

assets, student fees, and alumni donations. Fund

To the readers of this guide

accounting may be done using either the loan model, Whether you are a student leader excited about the

in which funding is distributed to individual project prospect of reducing your school’s carbon footprint,

owners, or the accounting model, in which funding a sustainability coordinator building a strategic

is transferred to and from a central account. There plan, a facility manager exploring options for energy

are also several options for fund oversight, such as efficiency retrofits, an administrator seeking advice

the use of a management committee or housing the on GRF management strategies, or a researcher

fund in a specific office. Funds may differ in terms of interested in innovative sustainability financing

their project criteria—such as payback requirements mechanisms, we hope you find this Guide to be a

or environmental benefits—and whether they track useful resource. Through this document, our goal

project savings using engineering estimates or is to facilitate the continued growth of GRFs as

empirical measurement. an effective tool for cutting expenses, reducing

environmental impact, and enriching campus

communities.

5Chapter 1:

What is a Green Revolving Fund?

This chapter: Green revolving funds are often managed by

• Provides a high-level overview of the GRF model a committee drawn from different stakeholder

groups on campus. These may include students,

• Discusses some common arguments for investing faculty, facility or energy managers, administrators,

An Introductory Guide to GRF Implementation & Management

in a GRF sustainability coordinators, and others. Funds may

also be managed directly by administrators or by the

Facilities, Finance, or Sustainability Office. While

2.1 The green revolving

GRFs can finance many types of projects, they

fund model typically target energy, water, and waste reduction

Facing budget cuts and rising energy costs, many due to their potential cost savings. Projects have

educational institutions are grappling with how to included lighting upgrades, boiler replacements,

finance urgently needed—but capital intensive— water pipe insulation, low-flow toilets, building

energy efficiency upgrades on campus. One strategy envelope upgrades, solar panels, and more.

for overcoming these challenges is creating a green After reviewing a variety of funds in higher

revolving fund (GRF). A GRF is an internal education, SEI developed the following two

investment vehicle that provides financing to parties criteria for a green revolving fund:

within an organization for implementing energy 1 The fund must finance measures that reduce

efficiency, renewable energy, and other sustainability resource use (e.g., energy, water, waste) or mitigate

projects that generate cost-savings. These savings greenhouse gas emissions (e.g., renewable energy).

are tracked and used to replenish the fund for the

next round of green investments, thus establishing 2 The fund must revolve so that at least some of the

a sustainable funding cycle while cutting operating savings generated by reducing operating expenses

costs and reducing environmental impact. are required to be repaid to the fund, thus providing

capital for future projects.

Figure 1: How Green Revolving Funds Work

How Green Revolving Funds Work

DATED HEATING

2. Finance efficiency project

SYSTEM with Green Revolving Fund YEAR SAVINGS

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8

ENERGY

USE

1. Identitfy energy 3. Repay loan from energy savings,

EFFICIENCY

waste on campus UPGRADE

Reinvest new monetary savings

62.2 The case for green Convey reputational benefits: A GRF can

revolving funds signal your institution’s commitment to sustainability

and operational efficiency in a way that one-time

Non-revolving investments from an operating investments cannot. It is a unified, purposeful

budget, capital budget, or endowment can also investment vehicle that generates more positive press

drive improvements in campus environmental than conventional top-down investments.

performance. So why should you adopt a GRF?

Catalyze a culture shift: A GRF also

There are several key advantages that revolving funds represents a commitment to larger strategic goals,

hold over traditional non-revolving expenditures. such as greenhouse gas reductions, and provides a

An Introductory Guide to GRF Implementation & Management

Revolving funds: tangible vehicle for achieving them. “A GRF provides

Demonstrate the business case for constant focus on the idea that you want continuous

improvement until you get to a carbon footprint of

sustainability: Despite the large cost-saving

zero,” says Anthony Cortese, Founder and Senior

potential of energy efficiency and sustainability

Fellow at Second Nature and Trustee of Tufts

investments, many institutions perceive them as

University and Green Mountain College. “That

an expense only. Rather than simply allowing the

doesn’t happen if you use debt financing or some

savings from these projects to be absorbed into the

other kind of capital financing.”

operating budget, a GRF tracks the savings distinctly

and directs them into future projects—thus creating a

Create a programmatic approach: A

measurable return on investment (ROI).

GRF creates a formalized program of sustainability

Established GRFs report a median annual ROI of

investments rather than a series of one-off projects.

28 percent (see SEI’s Greening the Bottom Line 2012

GRFs typically include specific requirements to

report), reliably outperforming average endowment

ensure fiscal discipline, environmental responsibility,

investment returns while hedging against rising

and a clear financing process that funnels savings

energy costs.

from past projects into current spending plans. In

Engage and educate the campus some cases, this source of funding actually enables

community: Whereas traditional capital projects to be implemented that would otherwise

improvement investments are typically managed by be omitted. For example, the University of New

a small team of administrators, a GRF can bring Hampshire historically struggled with a complicated

diverse stakeholders together to make decisions about financing process that sometimes prevented them

investments and build a sustainability strategy. GRFs from investing in high-return energy efficiency

can also issue loans to projects proposed by students projects. “A GRF allowed us to get the wrinkles

and other community members, thus promoting out and allowed everyone to say ‘I trust this

entrepreneurship and outside-the-classroom methodology,’” says Matt O’Keefe, Energy Manager

learning. at UNH.

7Leverage savings into opportunity:

GRFs are a great way for organizations to capitalize

on the savings from energy efficiency projects to

promote sustainability in general. For example,

Dartmouth College’s GRF directs 10 percent of

the savings from projects into a Green Community

Fund. Students, staff, and faculty can then apply

for money from this fund for projects that promote

sustainability on campus, whether or not they have

financial paybacks.

An Introductory Guide to GRF Implementation & Management

Track performance: You cannot manage what Lane Community College – Health & Wellness Center. Large

you do not measure. A GRF creates a streamlined projects funded by GRFs can generate a high volume of savings

process for an institution to distinctly track, manage, while providing a visible symbol of an institution’s commitment to

sustainability.

and analyze the financial and resource savings

resulting from sustainability projects. The Green

Revolving Investment Tracking System (GRITS) way that does not lend itself to a revolving approach.

was developed as part of The Billion Dollar Green Potential GRF adopters should carefully weigh the

Challenge, and collects, standardizes, and analyzes associated pros and cons of the model to ensure that

data related to GRF performance (see Section 5.3: it is appropriate for them.

Resources).

Seize new fundraising opportunities:

Some institutions have had success with fundraising

for a GRF, both from alumni and external

foundations. For example, President Elizabeth Kiss

and her development team at Agnes Scott College

raised over $400,000 in seed capital from donors

within a few months by pitching their fund’s strong

ROI and its potential to turn the campus into a living

laboratory for sustainability.

Despite the strong case for the GRF approach, it

may not be the best strategy for every institution.

For example, an institution may not yet want to

commit the cost-savings from energy efficiency

to future projects until it has verified that there

are enough investment opportunities available to

absorb such funding. In other cases, an institution’s

procedure for financing projects may be set up in a

8Chapter 2:

The Anatomy of a GRF

This chapter: 2.1 Seed capital

• Discusses key components that make up a green

Capital for a GRF may be obtained from a variety

revolving fund strategy

of funding sources, and some institutions have

An Introductory Guide to GRF Implementation & Management

• Provides a menu of options for how each fund combined multiple sources. Potential seed funding

component might work sources are discussed below.

• Provides recommendations for tailoring each Operating budgets

component to your institution

Annual operating budgets are the most common

source of GRF seed capital. This budget is often the

No two green revolving funds are exactly the same.

most readily available and flexible funding source,

While all GRFs finance measures that improve

and because the savings that GRF projects generate

environmental performance and use the associated

will often come from the operating budget, it may

cost-savings to finance future projects, they can differ

be seen as the most appropriate source of seed

on a wide range of parameters including structure,

capital. An operating budget may provide a one-time

size, mission, management, project criteria, funding

infusion of capital or multiple infusions over time to

sources, payback requirements, and more.

scale the fund gradually.

Successful funds will be tailored to the distinct

structure and culture of their home institution. Within operating budgets, common sources can

Perhaps the most powerful attribute of the GRF include the facilities, sustainability, or energy

model is that each of its components can be adapted budgets, as well as other departmental budgets or

to the unique challenges, goal, and opportunities that administrative funds. In some cases, shrewd fund

you face. Key components are discussed below. proponents have been able to tap into unused

or underutilized budgets to launch a GRF, thus

converting these funds into a high-return investment

opportunity. For example, the University of Vermont

is using a portion of its cash reserves— normally held

in low-risk investments before being spent—to seed

its GRF.

9Endowment principal Students

An institution may also invest its endowment funds Student sources of capital include a green fee

directly into a GRF. Given recent volatility and risk levied on students (either mandatory or voluntary)

in financial markets, investing in high-return, low- or student government funding. If proposing a fee,

risk sustainability projects on campus may present it is advisable to first conduct a willingness-to-pay

a favorable option for endowment managers. Refer analysis by polling the student body to: 1) assess

to SEI’s GRF Investment Primer for more detailed support for the fee, 2) determine the optimal size of

guidance (see Section 5.3: Resources). the fee, and 3) estimate the revenue that the fee will

generate for planning purposes.

Utility rebates and incentives

Utility companies often offer programs to large Donations and grants

An Introductory Guide to GRF Implementation & Management

institutional customers to encourage them to reduce Many institutions, especially colleges and

energy use, such as rebates, demand response, universities, have relationships with outside

or other incentives. In exchange for conserving foundations or other donors who seek to foster

electricity or natural gas through upgrades and research and improve programs and operations.

retrofits, colleges and universities are often given GRFs are often appealing because of their

reduced rates or cash rebates, which they can interdisciplinary scope, ability to promote education

then use to seed a GRF. Sometimes GRF project and engagement, and environmental and economic

savings then translate into even further incentives benefits. The Jessie Ball duPont Fund recently

from the utility company. launched the first foundation grantmaking program

in the country specifically designed to help seed

Capital budgets green revolving funds at a select group of colleges.

Institutions often have funds set aside for large capital Some funds start with a few large alumni donors,

projects such as new construction and renovations. and others are part of targeted sustainability or

These funds may be housed within a facilities budget, broader fundraising campaigns. A gift to a GRF

within the endowment, or as a separate budget combines the immediate impact of an annual fund

entirely. Capital budgets are often already used to gift with the longevity of an endowment gift. A

fund large energy efficiency projects, making them a hypothetical $100,000 contribution will provide

logical source of seed money. more than $555,000 in cumulative savings to the

institution over 10 years (based on the median 3.5

Cost-savings or revenue from year project repayment period reported in Greening

existing projects the Bottom Line 2012).

A GRF can be financed from savings or revenue

being generated by projects that were financed by Government funding

other means. This may provide a low-risk option if A variety of government programs exist that can

decision-makers are hesitant to commit capital to a be used to seed a GRF, including programs at the

GRF without proof of actual savings from projects federal, state, and local levels. Institutions have used

within the institution. For example, the savings both American Recovery and Reinvestment Act

from a lighting upgrade or revenue from the sale of (ARRA) grants and state energy efficiency programs

renewable energy credits (RECs) from on-site solar to either start funds directly, or to implement projects

power generation may be used to start the whose savings are then used to seed a revolving fund.

fund without requiring additional capital.

10Key considerations for seed capital 2.2 Accounting systems

There is often a tradeoff between risk and reward when

The accounting system is the backbone of a GRF.

allocating funding to a GRF. Large capital allocations

This component includes the accounts, stakeholders,

from existing sources (e.g., an endowment or capital

procedures, and rules that are involved in moving GRF-

budget) enable the fund to finance large capital-

related money within the institution. Accounting is

intensive projects that will produce a high volume of

often the most complex component of successful fund

savings. Large funds are also more likely to become

design, so it should be addressed early.

firmly established because they have more flexibility to

finance projects and pay fund management expenses,

Accounting systems can be divided into

but they represent the most institutional commitment.

two broad categories:

An Introductory Guide to GRF Implementation & Management

Conversely, incremental funding strategies (e.g., annual

allocations from the operating budget, savings from Under the loan model, the project applicant (e.g.,

existing projects, or an annual student fee) put fewer department, school, campus group, etc.) actually

resources in play if the fund encounters obstacles, but borrows money from the fund via a budget transfer.

this may prevent the fund from becoming established The project owner is then responsible for repaying the

and quickly achieving the highest cost-savings. loan (with or without interest, see next section), using

the savings the project produced within his or her own

Many institutions have started their funds small to campus unit. This model works best when project

demonstrate effectiveness, then scaled up once the applicants have control over distinct operating budgets,

administrative structure is operational. As Rosi Kerr, discrete ownership of projects, and facilities staff or

Dartmouth College’s Sustainability Director, noted, building technicians to assess potential improvements.

“I would rather start small and knock it out of the park

than bite off more than we can chew initially.” For Under the accounting model, funds are transferred

example, the Harvard Green Loan Fund was capitalized to the project applicant, or to a central facilities

with $1.5 million in 1993, and was revived and department, but repayment is made via a transfer of

enlarged to $3 million from the President's Office funds back into the GRF from a centrally managed

budget in 2001. As a result of its consistent success, it operating budget (often utilities) where the savings

was doubled in 2004 and again in 2006 to arrive at its were generated. The project recipient typically does

current size of $12 million. However, other schools not have discrete ownership of the project. This model

such as Macalester College have encountered problems works best when there are no autonomous entities

with starting small, finding that less capital in a GRF (e.g., colleges, schools) within an institution, or when

leads to a proportionately higher administrative cost those entities draw from the same central budget. The

and burden on staff, and less flexibility in choosing and GRF may be a distinct account (often with its own

installing projects. account number) or it may take the form of a concept or

agreement (e.g., a line item on annual budgets) without

When deciding how to size your fund and at what rate maintaining a physical account balance.

(if any) to scale it over time, factors to consider include

1) the volume of potential projects and their ability to Successful funds have been developed using both

absorb capital, 2) your institution’s tolerance for change models. The key lesson across all institutions is that

and financial innovation, and 3) the capacity of your the GRF accounting system must be tailored to work

fund management team and facilities department to within the existing system. A GRF is not a pre-defined

support project implementation.

11entity to be adopted wholesale; it is a flexible concept 2.4 Fund oversight

that can be molded to fit with your institution’s

current standards and practices. Experience has The set of stakeholders tapped to oversee a GRF

shown that adapting the model is crucial for smooth is another key consideration that affects both the

implementation. SEI’s GRF Investment Primer (see politics of the fund and its performance. There

Section 5.3: Resources) provides more discussion. are three broad options for selecting projects and

managing the operations of a GRF (the details of

2.3 Payback mechanics management are discussed in Section 2.5: Fund

Operations):

The size and timing of repayments to the GRF may

also be customized. For example, projects may repay • A management committee is the most common

An Introductory Guide to GRF Implementation & Management

only a portion of their savings to the fund each fiscal GRF leadership model. Such a committee may

year or period. Alternately, they may be required to be formed from a pre-existing body such as a

repay an amount greater than the original loan value, working group or may be formed specifically for

either by paying interest on outstanding loan balances the GRF. Stakeholder groups who will be involved

or by repaying more than 100 percent of the loan with or affected by the fund (e.g. students, facility

value in total. In some cases, an administrative fee has managers, faculty, administrators) should typically

been levied on projects in order to cover the fund’s be represented on this committee to maintain buy-in

operating costs. Where GRFs target mainly projects and contribute their expertise.

that create savings in the central utilities budget,

interest or a fee is sometimes charged only on loans • Staff and resources from a relevant office may be

for departments outside of the central budget such used to oversee the fund—often the finance, facilities,

as athletic stadiums or student government-owned or sustainability office.

buildings. • A dedicated manager may be appointed

There is often a tradeoff between making GRF specifically to run the fund, or fund management

financing attractive to funding applicants and the may be added to the job responsibilities of a current

need to cover administrative costs or grow the fund administrator.

over time. Project recipients might prefer to retain a

Management by committee is often advantageous

portion of annual savings, but it will be at the expense

for several reasons. First, it leverages the unique

of quickly replenishing the fund. Similarly, charging

breadth of expertise in a campus community. Second,

interest or requiring repayment over and above the

it promotes engagement and awareness of the fund.

loan value will allow the fund to grow organically

Third, it promotes cross-disciplinary collaboration

without additional capital infusions, but this

and innovation. Fourth, it reduces the burden that

places a higher cost on project owners. The correct

falls on any one member of the committee. If a

balance will depend on your institution’s political

student green fee or student government funds

environment and the goals of your fund.

are used to capitalize the GRF, it is particularly

important to have student representation on the fund

committee. However, a smaller management team

housed in a single office may offer tighter control of

financing and a more streamlined process for issuing

loans.

12In some cases, the leadership structures highlighted 2.6 Project criteria

above have been combined, with different groups

managing different aspects of the fund. For example, When assessing potential projects, it is helpful

a sustainability director or administrator may serve for fund managers to work from a specific set of

as the fund manager and coordinate the operations project criteria. These criteria may include both

of the fund, with a committee (sometimes chaired by hard requirements and preferred attributes. Some

the fund manager) that selects projects and provides common project criteria include:

guidance.

• Payback duration

2.5 Fund operations and • Capital cost

project selection

An Introductory Guide to GRF Implementation & Management

• Specific environmental benefits such as resource

conservation or greenhouse gas reduction

The management of fund operations involves a

broad array of duties. Many institutions create • Cost-effectiveness metrics such as greenhouse

a GRF charter, an official and publicly available gas reduction per dollar of capital cost

document that explains how the fund operates. This • Potential for community engagement and

is particularly important when campus community collaboration

members will be applying for GRF financing.

• Educational benefits

Charters are often developed from a written proposal

used as a forum for discussion during fund design Project criteria should be selected based on two

and may use much of the same language (see Steps factors. First, they should promote the mission of

2, 4, and 7 in Chapter 3 for more discussion of the fund. A GRF that is focused on maximizing

proposals, charters, and other documentation). operational efficiency might have aggressive payback

requirements, whereas a fund that emphasizes

It is important to clearly specify your fund’s

community engagement might favor projects that

procedure for reviewing, evaluating, and selecting

are student-led. Second, criteria should be tailored to

projects. Project selection may be conducted by

the actual portfolio of projects that are available for

soliciting applications from the campus community

investment.

and putting them through a competitive process.

Alternatively, fund managers may select projects Consider incorporating flexibility in project

non-competitively. For example, they may compile requirements at the discretion of the fund managers.

a prioritized list of potential projects identified They may need to adapt as the portfolio of

via an energy audit and select projects from this available projects changes over time or as unique

list. If using this approach, it is advisable to have a opportunities arise. For example, a project may

representative from the facilities department either compensate for failing to meet financial requirements

on the management team or in close contact with with outstanding performance in other areas such

the team in order to streamline this process. Projects as education, engagement, or tackling deferred

may also be identified from previously existing lists maintenance. In addition to specific criteria, projects

such as deferred maintenance, or through research by should also be prioritized in a way that best allocates

other groups on campus. limited resources while accounting for the feasibility

and timing of projects given other constraints, such

as staff availability.

132.7 Measuring savings performance unless necessary. Other schools, such as

the University of Denver, perform both upfront and

The GRF model relies on capturing cost savings retroactive M&V on larger projects, and use project

to replenish the fund, so the method by which specifications and engineering estimates for smaller

those savings are measured is crucial. There are ones.

two main strategies that fund managers may use to

calculate savings from projects in order to determine 2.8 Long-term strategy

repayment amounts.

A GRF can drive broader strategic initiatives,

First, fund managers may use front-end savings including Sustainability Master Plans or Climate

estimates based on engineering analysis. This method Action Plans (CAPs). When defining your fund’s

An Introductory Guide to GRF Implementation & Management

relies on technology specifications and assumed long-term vision, consider two key possibilities. First,

usage patterns to predict future performance. This is it is often effective to tie the fund to long-term goals

the most straightforward and inexpensive approach, like emissions reductions or capital improvement

but it will not capture any deviations in the event that plans, both when building buy-in for a GRF and

a project performs better or worse than expected. when operating it. This connects the fund with

Second, fund managers may retroactively calculate other initiatives and may provide a source of capital

savings based on actual performance. This entails to meet campus objectives. Second, GRFs present a

using a measurement and verification (M&V) unique opportunity to bring campus stakeholders to

approach to directly meter savings while accounting the table—both as part of a management committee

for conflating factors like weather and usage patterns. and as project applicants. This can create a forum

This approach is more accurate but also more costly for collaboration and innovation that goes beyond

and labor-intensive. financing.

There are several potential levels of rigor for M&V “The climate issue and the challenge

analysis. An institution may perform rigorous

building energy modeling based on submetering

of making affordability and

data, or it may measure pieces of equipment accessibility of higher education a

individually and extrapolate for the full set of

priority—the two work together.

equipment installed. Another option is to conduct

a less rigorous assessment of whether utility costs are It’s not one versus the other,” said

decreasing over time. This will not be sufficient to Anthony Cortese, Founder and Senior

calculate project repayments, but it can help verify

that a project or portfolio of projects is decreasing Fellow at Second Nature and Trustee

costs broadly. of Tufts University and Green

Some institutions benefit from a best of both Mountain College. “A GRF is a way

worlds approach in which the loan approval and

repayment schedule are based on estimated savings,

to get a serious focus on deferred

but M&V is then performed to verify that the maintenance at the same time that we

project is functioning according to projections.

push toward dramatically reducing

This has the added administrative benefit of not

requiring updates to the repayment process based on the carbon footprint.”

14GRF Anatomy in Practice: Four Case Studies of Successful Funds

School Seed Fund Accounting Project Measuring

Funding Oversight System Criteria Savings

Alumni and Sustainability Accounting Payback critical for Repayments based

foundation Steering model selection – flexible on estimates and

donors, utility Committee time periods measured savings

savings

An Introductory Guide to GRF Implementation & Management

Sustainability

Money market Director and Energy Accounting 6-year payback Repayments based

fund within Manager; with model requirement on estimates and

approval from AVP measured savings

endowment

of Facilities and VP

of Business and

Finance

President’s Director of Loan model 5-year payback Repayments

administrative Sustainability; requirement based on estimated

funding Advised by Loan savings but

Fund Advisory confirmed with

Committee measurement and

verification

Operating cash VP of Finance and Accounting 7-year payback Varies by

reserves Administration; model requirement; GRF project

Advised by returns 5 percent

Energy Initiatives of its outstanding

Committee balance annually

to cash reserve

For example, the University of New Hampshire Matt O’Keefe, Energy Manager of UNH, notes that

formed an Energy Working Group with the goal of their GRF has turned energy efficiency projects into

meeting its greenhouse gas emissions reduction targets a consistent program rather than a series of one-

under its CAP. When the GRF was established, this off investments, which has increased interest from

group became the management committee for the fund potential funders. “We’ve already leveraged the fund

and now uses the fund as the main financial instrument to participate in larger programs and receive grant

to drive progress toward CAP goals. money,” he says. For example, a grant of $50,000 for

a solar power installation might turn into $400,000

of investment over 10 years as savings revolve. “I talk

about how money will be leveraged into this program,

and people are a lot more interested.”

15Chapter 3:

10 Steps to a Successful GRF

This chapter: Step 1: Do your homework

• Presents a step-by-step guide to designing,

The first step in developing a successful GRF is to

implementing, and managing a GRF

gain an understanding of the range of GRF models

An Introductory Guide to GRF Implementation & Management

• Provides key considerations and resources and to begin thinking about how the design of your

for each step fund can be tailored to your institution. Much work

has already been done in this area, and using existing

This chapter provides a roadmap for designing, materials can cut months from the fund development

implementing, and managing a successful GRF. process. There are two key areas in which research is

These steps will aid you in developing a fund that: crucial.

1) maintains high financial and environmental

First, learn about GRFs in use at your peer

performance, 2) effectively engages key stakeholders

institutions. Gain a basic understanding of how

on campus, and 3) is tailored to the unique

these funds are structured, the types of projects they

character of your institution. While each fund

typically finance, and popular variations on the GRF

development process will differ by institution, this

model in use by institutions similar to your own.

chapter provides a general framework that is widely

Several resources have been assembled as part of

applicable across institutions. Each step addresses

The Billion Dollar Green Challenge to facilitate this,

a separate component of the GRF creation process,

including GRF case studies as well as Greening the

and they are positioned roughly in the order they

Bottom Line 2012 (see also Section 5.3: Resources).

should be conducted. However, the steps are often

A keen understanding of GRFs at peer institutions

interconnected. Elements of each step may need to be

can help build the case for your fund while providing

addressed before or after the point at which it is listed.

ideas for how to best adapt the model.

16“Don’t reinvent the wheel. Talk to Step 2: Select your model

other universities who have made this Early in the fund development process, tentatively

work and assimilate those programs outline a basic structure and mission for the fund.

GRFs have many variable elements that can be

into a custom program that will work adapted to the unique challenges, opportunities, and

at your school” said John Onderdonk, priorities of your institution. There are no established

Caltech’s Director of Sustainability rules for how a GRF must be structured, so be on the

lookout for opportunities to innovate.

Programs. Chapter 2: Anatomy of a GRF provides specific

An Introductory Guide to GRF Implementation & Management

guidance and decision points for each component

Second, be sure to examine the elements of your own

of a GRF.

institution’s operations that are relevant to a GRF.

These include: Fund design should be an iterative and interactive

process. It is often helpful to begin with a concept

• How are utility services distributed and paid on

proposal, which can serve as a point of discussion

campus? Is the entire institution run as one large unit

with stakeholders on campus as you seek their

or is the university split into smaller, autonomous

feedback. This may take the form of a document,

departments or schools?

presentation, or a few talking points. Engage key

• How is money transferred internally? Universities stakeholders with this proposal early and often, being

often have accounts associated with each department sure to include facility managers, energy managers,

and organization and it may be necessary to secure an sustainability directors, investment managers, and

account for the GRF. administrators in charge of operations and finance.

Student groups and faculty can also provide valuable

• Which stakeholders contribute to decisions about

feedback, particularly those active in sustainability,

facility operations and project finance? Who will

economics, and engineering. The goal of this initial

need to be consulted in order to build buy-in for

round of discussions is to identify logistical, political,

the fund?

and financial barriers to a GRF; develop a strategy

• What is the current state of energy efficiency and for overcoming these barriers; lay the groundwork for

auditing on campus? Have any studies been done to building future support; and refine the structure of

identify potential energy efficiency or sustainability your proposed fund to capture opportunities at your

projects? institution.

17Step 3: Assess opportunity Step 4: Build buy-in

and run the numbers A key component of developing a successful GRF is

In order to implement a successful GRF, it is thorough stakeholder engagement. First, determine

important to first understand its investment the key stakeholders and decision-makers whose

potential at your institution. This can be done by support will be required to establish and sustain

in-house facilities staff (they may already have a a GRF. Second, consider those stakeholders’

wish list of projects) or by hiring a contractor to responsibilities in the institution, the performance

perform an energy audit. If your institution has metrics on which they are evaluated, and how a

signed on to The Billion Dollar Green Challenge, GRF can be leveraged to help them meet their goals.

Third, engage those stakeholders to refine the GRF

An Introductory Guide to GRF Implementation & Management

consider consulting the project library of the

GRITS web tool (see Section 5.3: Resources) proposal so that it is in line with the needs and goals

for examples of projects typically financed by of all parties. A written proposal (building from the

GRFs. If the fund will solicit project applications concept proposal in Step 2: Select your model) can

from the campus community, it can be useful to be a helpful tool during this process. This document

determine in advance which projects are likely can serve as a forum for discussion and debate as the

to receive financing in the first round and assess GRF concept evolves, and in many cases it can evolve

their potential performance as well. into the fund charter once the proposal is approved.

The ideal result of this step is a pipeline of Note that building buy-in and a sense of collective

projects that the GRF will likely finance in ownership should be a continuous process that

the first few rounds of investment, including occurs along with all of the other steps. However, it is

estimates of the costs and savings associated with particularly important in the early stages, in order to

each project and a forecast of how the portfolio streamline the fund’s development and ensure that no

of projects as a whole will perform. Forecasting office or stakeholder is inconvenienced or left out.

the fund’s expected performance over the first

few years—including metrics like total savings, Step 5: Secure seed capital

annual return on investment (ROI), average

payback period, and net present value (NPV)—is The process of securing seed capital can range from

also helpful for building buy-in and tailoring a straightforward allocation of available funding

your fund model to maximize performance. This to a laborious multi-month process of consulting

can be done in GRITS or using custom-made decision-makers. It is therefore advisable to begin this

spreadsheets, which can then be used for tracking effort early. See Section 2.1: Seed capital for a review

once the fund is launched (see Step 9: Track of each potential source of seed funding.

performance for more information, including a One key strategy is to look for underutilized

sample performance analysis graph). capital, particularly if you are having difficulties

identifying potential funding sources. Because

of the high returns and low risk associated with

GRF investments, such a fund is often a favorable

alternative to allowing capital to go unused or poorly

used. To finance Caltech’s $8 million GRF, for

example, administrators tapped into a money market

18rainy day fund within the endowment that was going

largely unused while earning 1-2 percent annual

returns. The money now generates a return of 24

percent annually.

The size of the GRF and the amount of capital

to be raised should match your fund’s goals and

the campus’ potential for projects. Step 3: Assess

opportunity is crucial in order to determine an

appropriate size for the fund.

An Introductory Guide to GRF Implementation & Management

Step 6: Establish financial flows

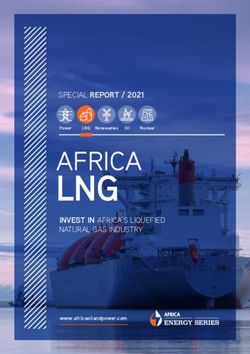

Stanford University rebate from utility PG&E. Demand-side

All stakeholders should feel comfortable with the energ y efficiency is a sustainability cornerstone in Stanford’s en-

loan and repayment process. Before any project is erg y solutions portfolio. Such rebates are also often used for GRF

seed funding and project repayments.

undertaken, involved parties must understand:

• Who pays the project invoice, which account they Step 7: Launch the fund

use, and when those funds will be available

Launching the fund is an important process in and

• Which account will be making repayments over of itself, especially if your fund relies on project

the course of the loan, how often those repayments applications from the campus community. If your

will occur, and the total of each repayment as well as institution has joined The Billion Dollar Green

the overall repayment obligation Challenge, this is also a good time to reach out to The

• How all of these flows of money will appear on the Challenge network for best practices and guidance

various departmental budgets and balance sheets (if from those with GRF management experience.

multiple departments are involved) When launching a GRF, it is useful to have the

first round of funding planned out. The insights

Establishing this internal accounting procedure

from Step 3: Assess opportunity will be useful to

is the point at which many GRF proposals stall

that end. As projects are being implemented, make

or fail entirely, often because technical details are

sure to continue the planning process for future

overlooked by fund proponents or are met with red

waves of projects or applications, as well as for

tape. Be sure to begin engaging on this issue early in

fund management, outreach, and meetings of the

the process. Some institutions have an independent

leadership team. Planning for the future is important

account with its own ID number for a GRF while

not only to efficiently manage the fund and ensure

others simply make an agreement to acknowledge the

that its capital remains effectively invested, but

savings of the GRF as annual budgets are distributed

also to show campus stakeholders how the fund is

(see Section 2.2: Accounting systems). Look at how

progressing and demonstrate success.

external purchases are made at your institution and

how funds are transferred internally, then base flows

of GRF payments upon these preexisting channels.

19It is important to establish your fund in a way that Step 8: Implement projects

fits within the campus culture and administrative

structure. Specifically: Implementing the initial round of projects will

inevitably lead to challenges and unexpected

• Formalize the GRF with a fund charter, bylaws, obstacles. There may be difficulties with fund

memorandum of understanding, formal project transfers and accounting, changes in maintenance

criteria, and any other necessary guiding documents. plans that disrupt your expected pipeline of projects,

Be sure that all relevant stakeholders are aware of projects that underperform once implemented, and

these documents. other potential issues. See Chapter 4: Common

• Consider developing a website for the fund. This obstacles for specific challenges often encountered

can provide a useful venue for informing the campus and strategies for overcoming them.

An Introductory Guide to GRF Implementation & Management

community about the fund, posting official fund

One approach to reduce these risks is a soft launch in

documents, providing tools and resources for getting

involved or proposing projects, and reporting on the which the first round of investment targets projects

fund’s progress to the public. that are expected to be straightforward and are being

implemented by trusted project managers. Another

• Consider providing office hours for inquiries about strategy is to begin with a manageable fund size and

the fund. This is particularly important if you will scale it up over time as success is demonstrated (see

be soliciting project applications from the campus

Section 2.1: Key considerations for seed capital).

community, as questions will arise.

Nevertheless, inform stakeholders that obstacles

Finally, when the fund is launched and the first few

will likely arise, and recognize that how they are

rounds of investment are underway, there are a few

key questions to be evaluated to ensure the fund runs handled will set the tone for future operations.

smoothly. These include: Be sure to include all relevant stakeholders in the

troubleshooting process. Despite the pressure to

• Is the GRF identifying enough projects to utilize produce successes and prove the GRF model, work

its capital? Where else should you look? through challenges slowly and carefully. Publicize

• Are those responsible for managing the fund successful projects to place any challenges in the

communicating effectively with each other and context of the broader GRF program and continue to

with other stakeholders? Is enough staff time being justify the use of capital for the fund.

allocated to manage the fund? Fund managers should be in close contact with the

• Are stakeholder needs identified in Step 4: Build facility managers, engineers, or contractors who

buy-in being met? Are these expectations reasonable implement the projects and can therefore provide

in practice? If so, how can resources be directed to on-the-ground perspective. This will allow problems

meet them? to be identified and resolved more quickly. Monthly

or quarterly progress reports may be useful for this

• What questions are arising from stakeholders?

purpose.

Can resources be provided to address them?

20Step 9: Track, analyze, and assess Note that even if you have elected to determine

project repayments based on estimated savings only,

performance conducting some measurement and verification

Once the fund is operating, tracking the performance (M&V) of individual projects will help to confirm

of individual projects and the entire GRF portfolio that they are operating as expected. Find a balance

over time is the next important step. between what is necessary for project troubleshooting

and determining payback and what is feasible given

First, determine the method by which you will staff capacity and budget.

measure savings from individual projects (see

Section 2.7: Measuring savings). Install any required Second, develop a system for tracking and analyzing

submeters and establish baseline data before project the overall activity of your GRF project portfolio.

An Introductory Guide to GRF Implementation & Management

implementation, then create a spreadsheet or The GRITS tool is specifically designed for this

use another software application such as GRITS function. Institutions also often use spreadsheets

(see Section 5.3: Resources) to manage this data built from scratch or accounting software for this

over time. Thorough project tracking will involve purpose. Verify that overall GRF performance is

recording the specifications of technology installed consistent with the forecasts conducted in Step 3:

and estimating expected savings; comparing those Assess opportunity above. If there is a discrepancy,

estimates to usage rates determined early on via determine its cause. It is often helpful to conduct

energy monitoring to ensure that projects are forecasts that are updated each year to chart a path

operating correctly; and then confirming savings forward for the fund and manage expectations. See

more conclusively later on by comparing submeter the Sample GRF Portfolio Analysis graphic for an

data to the baseline you have established. example of how fund performance can be visually

represented.

Sample GRF Portfolio Analysis:

Fund balance and total institutional cost-savings over time

TOTAL SAVINGS

FUND BAL ANCE

PROJECT 3

PROJECT 2

PROJECT 1

Mar -13

Oct -12

Jun -13

May -13

Mar -14

Sep -14

Jul -13

Nov -13

Dec -13

Apr -13

Aug -13

Feb -14

Jul -12

Nov -12

Dec -12

Aug -12

Jan -14

Jun -14

Sep -13

May -14

Sep -12

Oct -13

Jul -14

Feb -13

Apr -14

Aug -14

Jan -13

This graphic demonstrates how total capital available to the GRF and cost-savings generated by GRF investments can be modeled

over time. Such a graph is useful for forecasting future performance, illustrating historical data, or a combination of the two.

21It is also advisable to benchmark the performance • If the fund is performing well, could it be expanded

of projects, buildings, and the fund as a whole with more capital infusions?

against those of other institutions. In cases where

you are underperforming, take the opportunity to Leverage the data on project performance collected

identify the underlying causes and learn from peer in Step 9: Track performance to answer these

institutions. questions and adjust your fund strategy (and the

associated documentation). Adjustments may include

Step 10: Optimize and improve expanding or narrowing project criteria (e.g., relaxing

short payback requirements as the most cost-effective

While some of the main benefits of a GRF are

projects are exhausted), pulling in new stakeholders

stability and longevity, it must still adapt to changing

An Introductory Guide to GRF Implementation & Management

or staff to help identify or track projects, and

conditions. Even after launching, the fund’s design

adjusting the fund’s accounting procedures.

and management should be dynamic and adaptable.

The most successful funds periodically reassess their

performance and optimize accordingly. Some funds

undertake a formal strategic review of their charter

and governance every few years. It is important to not

only address aspects of the fund that are performing

poorly, but also to reassess more foundational aspects

of the fund such as which stakeholders are involved,

how cost savings are being measured and revolved,

the fund’s mission and project criteria, and how

the fund interacts with broader campus initiatives

and goals.

One key area for monitoring and optimization is

project performance. Key questions to consider

include:

• Which types of projects are performing especially

well, both within your institution and among your

peers? Consider using these as a model for new

projects.

• Where are project applications or ideas originating

and which parts of campus could be engaged further?

• Are your original project criteria still effective

for guiding the fund managers’ decisions? They

may benefit from adjustments as opportunities are

exhausted or new ones emerge.

22You can also read