WZB Report 2014 WZB Berlin Social Science Center

←

→

Page content transcription

If your browser does not render page correctly, please read the page content below

WZB www.wzb.eu

Report 2014

WZB Berlin Essays on:

Migration, integra-

tion, education,

Social Science Center global governance,

democracy, market

behavior and

science policy2 WZB Report 2014

Contents

WZB

Report 2014

Cover photo: 5 Editorial 48 Can You Trade Love for Wealth?

Getty Images / Grant Faint Jutta Allmendinger and Heinrich Baßler The TV Series Breaking Bad Can Teach

Us Some Lessons about Economics

7 The WZB in 2013/2014 Steffen Huck

50 With Shared Responsibility

Migration and Integration How Committee Decisions Depend on

Procedures and Size

11 Taking the Scripture Literally Justin Valasek

Religious Fundamentalism among

Muslim Immigrants and Christian

Natives in Western Europe Democracy

Ruud Koopmans

52 After the Arab Uprising

16 A Measure for Social Integration A Conflict-ridden Region in the Grip

Mixed Marriages between Muslims and of Autocrats

Non-Muslims Are Accepted but Rare Wolfgang Merkel

Sarah Carol

55 The Pragmatic Turn of Democracy

19 Religion Matters Combining Representation and

Faith and its Practice Influence Coex- Participation

istence More Than Generally Assumed Thamy Pogrebinschi

Sarah Carol, Marc Helbling and

Ines Michalowski 59 Elites in the Mirror

Self-Image, Collective Image, and Issues

of Responsibility among Germany’s

Education and Labor Leaders

Elisabeth Bunselmeyer and

22 A Call for Action Marc Holland-Cunz

The Right to Education Challenges

Germany’s Social and Educational

System Global Governance

Michael Wrase

62 Governing the World without World

26 Wishes and Reality Government

Managers and Part-Time Work: States, Societies and Institutions

A European Comparison Interact in Many Ways

Lena Hipp and Stefan Stuth Michael Zürn

29 Diverging Paths 66 The Rise of New World Players

How the UN Disability Convention In Global Governance, a Balance of

Affects School Reforms in Germany Power Is Re-emerging

Jonna M. Blanck, Benjamin Edelstein, Matthew Stephen

and Justin J.W. Powell

69 And It Does Listen - Sometimes

33 Growing in a Niche Public Debates Can Influence the

Dual Study Programs Contribute to Politics of the EU Commission

Change in Germany’s Higher Education Christian Rauh

Lukas Graf

72 Publications

Science and Globalization

76 In Focus

37 Globalization à la carte

The Political Economy of Research Co- 84 Bodies, Boards, Committees

operation with China Is Bound to Change

Benjamin Becker and Ulrich Schreiterer

All Things Considered

41 Preventing Global Disaster

International Governance of Dual-use 86 EU Support for Social Science and

Sciences Humanities

Alexandros Tokhi More Money for Identities and

Cultures

Jutta Allmendinger and Julia Stamm

Markets and Decisions

45 Goods without a Price Tag

Smart Market Design Can Make the

Distribution of Important Goods More

Fair and Efficient

Dorothea Kübler

WZB Report 2014 3Imprint About the WZB

WZB Report 2014 The WZB Berlin Social Science Center conducts basic r esearch

ISSN 2195-5182 with a focus on problems of modern societies in a globalized

Publisher

world. The research is theory-based, problem-oriented, often

The President of the WZB Berlin Social Science long-term and mostly based on international c omparisons.

Center (WZB)

Professor Jutta Allmendinger Ph.D.

Key research topics include:

Reichpietschufer 50 – democracy and civil society

10785 Berlin – migration and integration and intercultural conflicts

Germany – markets, competition, and behavior

Phone: +49 - 30 - 25 491 0 – education, training, and the labor market

Fax: +49 - 30 - 25 491 684 – inequality and social policy

– gender and family

www.wzb.eu

– international relations

Editorial staff – transnationalization and the rule of law

Dr. Paul Stoop (editor-in-chief) – innovation and science policy

Gabriele Kammerer

Claudia Roth

Kerstin Schneider 160 German and international researchers work at the WZB,

including sociologists, political scientists, economists, legal

Documentation scholars, and historians.

Martina Sander-Blanck

Translations Research results are published for the scientific community

David Antal as well as for experts in politics, business, the media, and civic

Rhodes Barrett

organizations.

Carsten Bösel

Nancy du Plessis

Teresa Go As a non-university research institute, the WZB is member of

the Leibniz-Association. The WZB closely cooperates with

Photo

Page 5: David Ausserhofer

Berlin universities. Its directors also hold chairs at universi-

ties in Berlin and beyond.

Layout

Kognito Gestaltung, Berlin

The WZB was founded in 1969 by members of the German

Printing arliament from all parties. The WZB is funded by the Federal

p

Bonifatius GmbH, Druck · Buch · Verlag, government and the state of Berlin.

Paderborn

4 WZB Report 2014Beyond Seven

Looking back on the WZB’s development in 2013, we can say

with great satisfaction that we did not experience a seven-

year itch in this seventh year of our tenure as the institu-

tion’s management. We take pride in what has been accom-

plished and are grateful for the dedication of the many people

who contributed to the WZB’s academic and societal impact.

We also thank our shareholders—the German federal govern-

ment and the Berlin state government—which have entrusted

us with the careful, wise, and creative use of the funding they

provide. They are realistic about what is possible for us and do

not call for us to attract ever more outside funding or to pub-

lish a constantly increasing number of peer-reviewed journal

articles at any price. Our shareholders encourage our efforts

to focus on certain topics in the European research agenda, to

pursue particular academic career paths, and to emphasize

networked research throughout Berlin. This constructive ex-

change with the federal and Land governments is a key asset.

This report gives many insights into what we do, stressing

the WZB’s service to social science and to public discussion

of basic social issues. Readers may imagine what lies behind

that input: the research itself, the institutional support for it,

and the intense work in internal committees as well as col-

lective celebrations and original events like the science

slams. All these activities ultimately enrich academic life and

scientific research.

Jutta Allmendinger and Heinrich Baßler

WZB Report 2014 5WZB Research

Education, Work, and Life Chances Dynamics of Political Systems

Research Unit Skill Formation and Labor Markets Research Unit Democracy and Democratization

Director: Professor Heike Solga Director: Professor Wolfgang Merkel

Research Unit Inequality and Social Policy Research Professorship Structural Problems of Liberal

Director: Professor David Brady Ph.D. Political Systems

Professor Kurt Biedenkopf

Project Group Demography and Inequality

Head: Professor Anette Eva Fasang Research Professorship Theory, History and Future of

Democracy

Project Group National Educational Panel Study:

Professor John Keane

Vocational Training and Lifelong Learning

Head: Professor Reinhard Pollak Project Group Civic Engagement

Head: Dr. sc. Eckhard Priller

Junior Research Group Work and Care

Head: Lena Hipp Ph.D.

Migration and Diversity

Markets and Choice Research Unit Migration, Integration, Transnationalization

Director: Professor Ruud Koopmans

Research Unit Market Behavior

Director: Professor Dorothea Kübler Emmy Noether Junior Research Group

Immigration Policies in Comparison

Research Unit Economics of Change Head: Dr. Marc Helbling

Director: Professor Steffen Huck

Junior Research Group Risk and Development

Head: Ferdinand Vieider Ph.D.

Trans-sectoral Research

WZB Rule of Law Center

Society and Economic Dynamics Managing Head: Professor Mattias Kumm

Bridging Project – Cultural Framing Effects in

Research Unit Cultural Sources of Newness

Experimental Game Theory

Director: Professor Michael Hutter

Heads: Professor Michael Hutter, Professor Dorothea Kübler

Research Group Science Policy Studies

Bridging Project – Recruitment Behavior of Companies in

Head: Dr. Dagmar Simon

Vocational Training and Labor Markets

Heads: Professor Dorothea Kübler, Professor Heike Solga

Project Group Globalization, Work and Production

Head: Dr. Martin Krzywdzinski Bridging Project – The Political Sociology of

Project Group Modes of Economic Governance Cosmopolitanism and Communitarianism

Head: Sigurt Vitols Ph.D. Heads: Professor Ruud Koopmans,

Professor Wolfgang Merkel, Professor Michael Zürn

International Politics and Law

Research Unit Global Governance

Director: Professor Michael Zürn

Research Professorship Rule of Law in the Age of

Globalization

Professor Mattias Kumm

Project Group The Internet Policy Field

Head: Professor Jeanette Hofmann Structure as of January, 2014

6 WZB Report 2014The WZB in 2013/14

After years of change wrought by constant re- skill formation, aspirations, and attainment, es-

cruitment and the emergence of a new struc- pecially during the transition from school to

ture having six research areas, the WZB had work.

time in 2013 to consolidate its achievements

and build on them. Research does well with a The Institute for Protest and Social Movement

phase of calm, as shown by this year’s list of Studies, in which researchers of the former

WZB works, many of which appeared with in- WZB Research Group on Civil Society, Citizen-

ternational publishers and journals. Numerous ship, and Political Mobilization in Europe would

WZBriefe and scholarly reports sparked discus- like to continue their work, is gaining a firm

sion, leaving their mark on specialists and the institutional footing. The WZB supports the

broad public alike. WZB events now have new, founding of this organization. Its public pre-

interdisciplinary formats inviting links with sentation in June 2013 gave a chance to reflect

other social sectors. on this field of inquiry and to consider avenues

of cooperation with other institutions.

Institutional Developments We are privileged to be an active part of the

Leibniz Association, which links 89 indepen-

The research units changed little during the dent nonuniversity research institutions rep-

year under review. The final phase of work in resenting a broad range of disciplines. We prof-

the Research Unit on Inequality and Social In- it from the joint research opportunities this

tegration was completed in March. The Schum- organization affords. Forming thematic clus-

peter Junior Research Group on Position For- ters, the new Leibniz research networks con-

mation in the EU Commission ended in stitute an outstanding resource on which we

September. Miriam Hartlapp, the head of the all draw. We welcome three new Leibniz cen-

group, accepted a professorship at the Center ters. The WZB will have an exceptionally close

for Social Policy at the University of Bremen. relationship with the Leibniz-Institut für Bil-

dungsverläufe (LIfBi). The LIfBi has now become

When the WZB founded the Alexander von part of the system of federal and Land research

Humboldt Institute for Internet and Society funding, a milestone in empirical research on

(HIIG) in 2012, critical questions ensued, and education, to which the WZB is committed.

the institute’s future seemed uncertain. But

the research has withstood scrutiny. Google is

initially supporting the institute through 2016, The WZB in Berlin’s Academic

and further sponsors have been found. The Setting

WZB has responded by creating the Project

Group on The Internet Policy Field, which is The WZB traditionally seeks close ties to Berlin

currently planned for three years. The group is universities, at which researchers at the WZB

expected to ensure a solid link between the can complete their doctorates and teach. With-

HIIG and the WZB and is headed by Jeanette out this opportunity, their academic careers

Hofmann, who is also a director at the HIIG. would not be possible. The WZB can do much

for the universities, too. We work with them,

Together with the Free University of Berlin training doctoral students, teaming up to apply

(FU), the WZB has also set up the Junior Re- for research funding, pooling resources for ap-

search Group on Neuroeconomic Decision The- pointments, and jointly financing junior re-

ory. It is seated at the FU and will begin its search groups.

work in 2014, exploring issues of research on

experimental and behavioral economics. The degree of coordination between the Berlin

institutions varies from discipline to disci-

The WZB has decided to establish a Research pline. Joint announcements of postdoctoral va-

Professorship on Risk and Adaptation in the cancies have already become a reality through

Transition to Adulthood. It will be offered to In- the network of Berlin’s behavioral economists,

grid Schoon, a professor of human develop- for instance. In 2013 the WZB, Humboldt Uni-

ment and social policy at the Institute of Edu- versity of Berlin, and the German Institute for

cation at the University of London. Her research Economic Research (DIW) together filled five

will focus on matters of social inequality in positions, for which more than 300 economists

WZB Report 2014 7had applied. The selected researchers have an search (BMFB) and the Jacobs Foundation. If

office at either the WZB or the DIW and at Hum- this international pilot program runs success-

boldt University. fully, the WZB will strive to extend it into other

areas of research. Heike Solga is also steward-

Networking is less advanced in the social and ing the WZB’s involvement in the Berlin Inter-

political sciences. Graduate schools in these disciplinary Education Network (BIEN), for

two fields operate separately. Creation of a which BMBF funding has been pledged from

common roof for them lies far in the future. the end of 2013 through 2016.

The WZB is now striving to interlink and even-

tually stabilize the considerable number of

doctoral programs. Discussions opened in 2013 International Engagement

for moving toward an integrated structure in

2014: the Berlin Center for Doctoral Programs The WZB seeks to help strengthen research in

in the Social Sciences. the social sciences and the humanities in Eu-

rope. To this effect we initiated an open letter

to EU Research Commissioner Máire Geoghe-

Strengthening Interdisciplinary gan-Quinn and members of the European Par-

Approaches liament in May. It called for an appropriate sum

to be guaranteed for the social sciences and

Projects spanning two or more areas within humanities in the negotiations on the new EU

the WZB continued expanding in many fields of research framework program, Horizon 2020.

activity: bridging projects and other joint re- The letter was cosigned by the Max Planck In-

search, joint events such as the Distinguished stitute for the Study of Societies, the Free Uni-

Lectures in Social Sciences, and jointly con- versity of Berlin, and the Bremen International

ducted advanced interdisciplinary academic Graduate School of Social Sciences.

training offered by the doctoral and postdoc-

toral scholars. The WZB’s series of Distin- Aside from working on research policy at the

guished Lectures was launched in 2013, with European level, the WZB expanded its scientific

Neil Fligstein (University of California, Berke- cooperation with European partners. The inno-

ley), Torsten Persson (Stockholm University), vative “Research in Pairs” program of the WZB

and Robert Keohane (Princeton University) and the Institute for Advanced Studies (IAST) of

each giving an address. the Toulouse School of Economics opened in

the spring of 2013. It affords scholars of both

Interdisciplinarity also figured prominently in organizations new possibilities for cooperating

the interaction of the organizations within the on a research project or academic work by al-

Leibniz Association. More and more Leibniz re- ternating relatively long exchanges at the

search alliances are forming. The WZB takes partner institutes. In the first round of these

part in four of them: educational potential, exit arrangements, Dorothea Kübler (WZB) and Yin-

from nuclear and fossil-fuel energy, crises in a gua He (IAST) are pursuing a joint survey on

globalized world, sustainable food production admission procedures at universities, and Fer-

and healthy nutrition. In the network dealing dinand Vieider (WZB) and Christoph Rhein-

with energy issues, the WZB has the role of co- berger (IAST) are developing an experimental

ordinator. design for “Texting Ambiguity Aversion in the

Wild: Experiment on Uncertain Health Risks.”

Institutionally, the WZB is emphasizing inter-

disciplinary research especially for postdoc- The WZB’s visibility in 2013 increased beyond

toral scholars in order to establish them in Europe’s borders as well. For instance, the

their own disciplines and to help them keep proven collaboration with the University of

the big picture in mind. An example is the pio- Sydney entered a new phase in November,

neering postdoctoral program that Heike Solga when a three-day workshop entitled “Re-Imag-

has initiated and elaborated in empirical re- ing the Future of Democracy” explored new op-

search on education. Of the 60 applicants cho- tions for cooperation with the Research Units

sen, 30 fellows from 22 scientific centers in on Democracy, Global Governance, and Migra-

Europe were admitted from the fields of so- tion (Michael Zürn, Ruud Koopmans, and Wolf-

ciology, psychology, pedagogy, and economics gang Merkel). Both the Rule of Law Center (un-

and are now working across subject-area der Mattias Kumm) and the Research Unit on

boundaries to grapple with important topics of Inequality and Social Policy (David Brady) were

educational research. They are focusing pri- involved, too.

marily on educational disparities, academic

successes against the odds, skill development The WZB found additional academic partners in

as an educational and social process, and mon- Singapore, concluding a cooperation agree-

etary and nonmonetary returns on education. ment with the College of Humanities, Arts, and

This research training group is funded by the Social Sciences of Nanyang Technological Uni-

German Federal Ministry of Education and Re- versity (NTU). Substantively, cooperation with

8 WZB Report 2014the NTU and with the National University of Interlinking Areas of Society

Singapore as yet another partner began with a

workshop entitled “Immigration Policies, Im- If the challenges to globalized societies are to

migrant Rights, and Social Inclusion – Western be mastered, various areas of society must im-

Experiences and Asian Challenges.” Leading prove what they know about each other and

migration researchers from the participating how they interact. To reinforce this dialogue,

institutions developed specific ways to con- the WZB has introduced “Science in Practice.”

tribute to this topic. This program gives young scholars the chance

to work in business, administration, the poli-

Another milestone in 2013 was the signing of cy-making community, or associations, where

the memorandum of understanding with the they offer their theoretical and methodologi-

International Social Science Council (ISSC) in cal knowledge as scientists in residence.

Paris. Cooperation will center on a joint fellow-

ship program announced in the summer for For three to twelve months, these academics

the first time. The WZB–ISSC Global Fellowship work with the selected partner on a specific

Program will bestow a six-month stipend to a project they have developed together. The

researcher from a developing country. The partner institutions profit from the expertise

widely advertised call for applications and the of the scholars, and the scholars gain insight

competitive selection procedure was conceived into the culture, logic, and approach of other

by the WZB and the ISSC together. The first sectors. These individuals acquire versatile

WZB–ISSC fellow has been invited for 2014. skills and can develop ideas for new projects

that may have practical relevance. The first

The ties to the Minda de Gunzburg Center for WZB researcher in this capacity worked in an

European Studies (CES) at Harvard University, international recruitment consultancy in 2013.

which have been institutionalized for some

years, consolidated further under the organi- The intention at the WZB is to promote this

zation’s new director, Grzegorz Ekiert. Two mutual understanding by doing more than

WZB–Harvard Merit Fellowships were awarded preparing corresponding publications and

in 2013: one to Céline Teney, a senior research- opening events to a broad audience. We regu-

er in the Research Unit on Migration, Integra- larly host “Lunch Talks” and the “Berliner Run-

tion, Transnationalization; the other to Sebas- den” – the latter sponsored by Soroptimist In-

tian Botzem, a research fellow of the Project ternational Deutschland – in which discussants

Group on Modes of Economic Governance. Both from a wide range of areas take part.

scholars will work at CES for three months. The

WZB’s cooperation with the University of Syd- A new series of events along these lines was

ney was fostered, too. In 2013 Matthew D. Ste- added. It began with a public discussion with

phen, a research fellow of the Research Unit on Vince Gilligan, the creator and producer of the

Global Governance, and Rustamdjan Hakimov, a critically acclaimed TV series Breaking Bad. The

research fellow of the Research Unit on Market exchange revealed the great interest in bound-

Behavior, spent a few months in Sydney, and ary-crossing dialogue between research and

Janine Bredehöft and Elisabeth Humphrys the arts. Gilligan, opera general manager and

came to the WZB from Sydney. series expert Sir Peter Jonas, and WZB director

Steffen Huck examined the theme of markets

The WZB’s presence throughout the world was and morals that lies at the heart of the series.

apparent also from the foreign guests interest-

ed in research of this organization. The inter-

national delegations that visited the WZB in Career Advancement

2013 included junior academics from Uganda;

scholars from the Khobara Center, a new think Young academics face a host of uncertainties,

tank in Yemen; and a group from the social sci- such as short-term contracts, part-time em-

ence academy in China. ployment, ambiguity about what is expected of

them during the doctoral and postdoctoral

The A.SK Academic Award and the A.SK Public phase of their work, excessively lax supervi-

Policy Fellowships serve as an international sion, unpredictable career prospects, and lack

beacon. They were conferred in 2013 for the of information about the job requirements in

fourth time. The economist and Africa expert other social sectors.

Paul Collier received the main award, with Klaus

Töpfer delivering a eulogy. The fellowships went These years of life are rife with other issues as

to Daniel Tischer (Centre for Research on So- well: How do I combine academia and family? Is

cio-Cultural Change, University of Manchester), science more than a calling and a vocation?

Rami Zeedan (University of Haifa), Olga Ulybina Does it dominate my entire life and leave little

(Cambridge Central Asian Forum), Theresa Rein- room for a partner, friends, parents, and chil-

hold (WZB), and Josef Hien (Max Planck Institute dren? Do I have to choose between these

for Study of Societies (Cologne and Turin). worlds?

WZB Report 2014 9For these reasons career advancement at the Finances and Human Resources

WZB centers on a code of conduct. As a written

statement of the rights and responsibilities of As in previous years, the financial perspective

doctoral and postdoctoral scholars being was shaped in 2013 by the Joint Initiative for

trained at the WZB, it serves as a common ori- Research and Innovation, in which the WZB

entation and foundation for people to work to- shares as a member institution of the Leibniz

gether. Questions of guidance and feedback, Association. The revenues received, and thus

constant dialogue, length of contract, start-up the total funds spent, at the WZB in the year

and wrap-up funding, and the possibilities of under review came to €19.3 million (as op-

pursuing a number of topics and gaining posed to €18.8 in 2012). Institutional funding

teaching experience are all addressed system- from the German federal government and the

atically and transparently. Land (state) government of Berlin totaled €15.2

million in 2013 (compared to €15.3 million in

2012). The revenues spent from external fund-

Alumni Network and “Friends of ing for research and development amounted to

the WZB” €4.2 million (€3.6 million in 2012). The exter-

nally funded projects that were in progress on

In May 2013 representatives of different December 31, 2012, accounted for 21.8% of the

spheres convened at the invitation of Kai-Uwe WZB’s total expenditures (19.8% in 2012).

Peter (Association of Savings Banks, Berlin) to

consult with and actively support the WZB An additional sum of €3.5 million for 27 new

through an association called The Friends of externally funded projects was raised in 2013

the WZB. The goal of this group is to facilitate (€5.6 million in 2012) from organizations pro-

networking between the WZB’s multiple con- moting research and from federal ministries,

tacts in Berlin, Germany, and the international the European Commission, public and private

community and to familiarize interested par- foundations, and industry. Over time there has

ties outside science and academia with this been a notable shift in the relative proportions

organization’s research results. The main goal accounted for by the donors. Since 2006, when

is take the critical examination of urgent con- the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG)

temporary issues and extend it beyond the sci- contributed 10% of the WZB’s external funding,

entific disciplines and to strengthen its moor- that share has risen to far more than 50% today.

ing in the policy-making community, business

and associations, culture, the media, and soci- The average number of people employed by the

ety. WZB by the end of 2013 was 368. 83.2% of the

institution’s total number of employed research

Just under 2,000 people have worked at the ers were on temporary contracts. Doctoral can-

WZB and left again since it was founded in didates made up 32.3% of the scientific staff, and

1969. For the WZB they are potential advisors, 22 doctorates were completed in 2013. 5 ap-

mentors, project partners, multipliers, employ- prentices had finished their training at the WZB.

ers, political allies, volunteers, and supporters.

Since then, nearly 500 WZB alumni have agreed The WZB’s efforts to provide working conditions

to join the new alumni network. Its formation that enable to reconcile work and family have

was celebrated at the inaugural meeting in Oc- carried the auditberufundfamilie® seal since

tober by more than 100 former and new mem- 2010. The WZB’s good practice and the measures

bers of the WZB. They gathered in the building, agreed upon to keep developing it were recog-

witnessed young academics present their work nized again when reinspected in 2013. In 2013,

at the science slam, and exchanged their views. the European Commission rewarded the WZB

The WZB is clearly a place with which its alum- with the "HR Excellence in Research" logo. The

ni identify and feel connected as they look WZB is the first German institution to receive

back on their time there. This line of tradition the logo thanks to the joint efforts of WZB mem-

became possible to highlight for the first time bers working in the fields of science, adminis-

– an auspicious beginning. tration, and research management.

10 WZB Report 2014Migration and Integration. How societies cope with immigration and the in-

creased cultural and religious diversity is explored mainly in the Research Area

on Migration and Diversity. The objects of study include the integration of immi-

grants along its various dimensions, the reactions of native populations to immi-

gration, as well as the impacts of immigration and diversity on social trust, coop-

eration and solidarity in society at large. Policies and institutions of core

relevance are immigration policies, citizenship, assimilation requirements,

church-state relations, and the welfare state.

Taking the Scripture Literally

Religious Fundamentalism among Muslim

Immigrants and Christian Natives

Ruud Koopmans

In the context of heated controversies over immigration and Islam in the early Summary: A lmost half of European

21st century, Muslims have become widely associated in media debates and Muslims agree that there is only one

popular imagery with religious fundamentalism. To counter this, others have interpretation of the Koran, that Mus-

argued that religiously fundamentalist ideas are only found among a small mi- lims should return to the roots of Is-

nority of Muslims living in the West, and that religious fundamentalism can lam, and that religious rules are more

equally be found among adherents of other religions, including Christianity. important than secular laws. Based on

However, claims on both sides of this debate lack a sound empirical base, be- these items, a WZB study shows that

cause very little is known about the extent of religious fundamentalism among religious fundamentalism is much

Muslim immigrants, and virtually no evidence is available that allows a compar- more common among Muslims than

ison with native Christians. among Christians. This is alarming in

the light of the strong link between

Religious fundamentalism is certainly not unique to Islam. The term has its ori- religious fundamentalism and out-

gin in an early 20th century Protestant revival movement in the United States, group hostility.

which propagated a return to the “fundaments” of the Christian faith by way of a

strict adherence to, and literal interpretation of the rules of the Bible. A large

number of studies on Protestant Christian religious fundamentalism in the US

have shown that it is strongly and consistently associated with prejudice and

hostility against racial and religious out-groups, as well as “deviant” groups such

as homosexuals. By contrast, our knowledge of the extent to which Muslim mi-

norities in Western countries adhere to fundamentalist interpretations of Islam

is strikingly limited. Several studies have shown that in comparison to the ma-

jority population, Muslim immigrants define themselves more often as religious,

identify more strongly with their religion, and engage more often in religious

practices (such as praying, visiting the mosque or following religious prescrip-

tions such as only eating halal food or wearing a headscarf). But religiosity as

such says little about the extent to which these religious beliefs and practices can

be deemed “fundamentalist” and are associated with out-group hostility.

A WZB-funded survey study among immigrants and natives in six European

WZB Report 2014 11countries – Germany, France, the Netherlands, Belgium, Austria and Sweden –

provides a solid empirical basis for these debates for the first time. The survey

with a total sample size of 9,000 respondents was conducted in 2008 among

persons with a Turkish or Moroccan immigration background, as well as a native

comparison group. Following Altermeyer and Hunsberger’s widely accepted

definition of fundamentalism, the fundamentalist belief system is defined by

three key elements:

- that believers should return to the eternal and unchangeable rules laid

down in the past;

- that these rules allow only one interpretation and are binding for all be

lievers;

- that religious rules have priority over secular laws. Ruud Koopmans i s director of the WZB research unit

Migration, Integration, Transnationalization and pro-

Native respondents who indicated that they were Christians (70%), and respon- fessor of sociology and migration research at Hum-

boldt University Berlin. He holds a guest professor-

dents of Turkish and Moroccan origin who indicated they were Muslims (96%)

ship at the University of Amsterdam.[Photo: private]

were asked about aspects of fundamentalism that were measured by the follow- ruud.koopmans@wzb.eu

ing survey items:

“Christians [Muslims] should return to the roots of Christianity [Islam]”

“There is only one interpretation of the Bible [the Koran] and every Christian

[Muslim] must stick to that”

“The rules of the Bible [the Koran] are more important to me than the laws of

[survey country]”

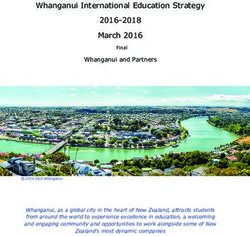

Figure 1 shows that religious fundamentalism is not a marginal phenomenon

within West European Muslim communities. Almost 60 percent of the Muslims

surveyed agree that Muslims should return to the roots of Islam, 75 percent

think there is only one interpretation of the Koran possible to which every Mus-

lim should stick and 65 percent say that religious rules are more important to

them than the laws of the country in which they live. Consistent fundamentalist

beliefs, with agreement to all three statements, are found among 44 percent of

the interviewed Muslims. Fundamentalist attitudes are slightly less prevalent

among Sunni Muslims with a Turkish (45% agreement to all three statements)

compared to a Moroccan (50%) background. Alevites, a Turkish minority current

within Islam, display far lower levels of fundamentalism (15%). Contrary to the

idea that fundamentalism is a reaction to exclusion by the host society, we find

the lowest levels of fundamentalism in Germany, where Muslims enjoy fewer

Christians Muslims

80 %

70 %

60 %

50 %

40 %

30 %

20 %

10 %

0%

Return to Only one binding Religious rules Agree with all

the roots interpretation more important three statements

than secular laws

Figure 1

Religious fundamentalism among native Christians and

Muslim immigrants in Western Europe

12 WZB Report 2014religious rights than in any of the other five countries. But even among German

Muslims, fundamentalist attitudes are widespread, with 30 percent agreeing to

all three statements. Comparisons with other German studies reveal remark-

ably similar patterns. For instance, in the 2007 Muslime in Deutschland study 47

percent of German Muslims agreed with the statement that following the rules

of one’s religion is more important than democracy, almost identical to the 47

percent in our survey that finds the rules of the Koran more important than

German laws.

The second striking finding in Figure 1 is that religious fundamentalism is

much more widespread among Muslims than among Christian natives. Among

Christians, agreement with the single statements ranges between 13 and 21

percent and less than 4 percent can be characterized as consistent fundamen-

talists who agree with all three items. In line with what is known about Christian

fundamentalism, levels of agreement are slightly higher (4% agreeing with all

statements) among mainstream Protestants than among Catholics (3%), and

most pronounced (12%) among adherents of smaller Protestant groups such as

Seventh Day Adventists, Jehova’s Witnesses and Pentecostal believers. However,

even among these groups support for fundamentalist attitudes remains much

below levels found among Sunni Muslims. Turkish Alevites’ view on the role of

religion is, however, more similar to that of native Christians than of Sunni

Muslims.

Because the demographic and socio-economic profiles of Muslim immigrants

and native Christians differ strongly, and since it is known from the literature

that marginalized, lower-class individuals are more strongly attracted to funda-

mentalist movements, it would of course be possible that these differences are

due to class rather than religion. However, results of regression analyses con-

trolling for education, labor market status, age, gender and marital status reveal

that while some of these variables explain variation in fundamentalism within

both religious groups, they do not explain at all or even diminish the difference

between Muslims and Christians. A cause for concern is that whereas religious

fundamentalism is much less widespread among younger Christians, funda-

mentalist attitudes are as widespread among young as among older Muslims.

Research on Christian fundamentalism in the United States has demonstrated a

strong association with hostility towards out-groups, which are seen as threat-

ening the religious in-group. To what extent do we find this linkage in the Euro-

pean context as well? To answer this question, we use three statements that

measure rejection of homosexuals and Jews, as well as the degree to which one’s

own group is seen as threatened by outside enemies:

“I don’t want to have homosexuals as friends.”

“Jews cannot be trusted.”

“Muslims aim to destroy Western culture.” [for natives]

“Western countries are out to destroy Islam.” [for persons with a Turkish or

Moroccan migration background]

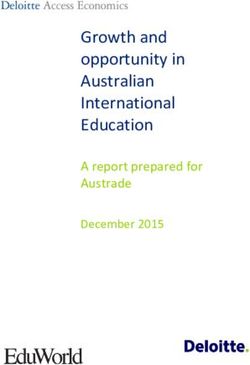

Figure 2 [see p. 14] shows that out-group hostility is far from negligible among

native Christians. As much as 9 percent are overtly anti-Semitic and agree that

Jews cannot be trusted. In Germany that percentage is even somewhat higher

(11%). Similar percentages reject homosexuals as friends (13 % across all coun-

tries, 10% in Germany). Not surprisingly, Muslims are the out-group that draws

the highest level of hostility, with 23 percent of native Christians (17% in Ger-

many) believing that Muslims aim to destroy Western culture. Only few native

Christians display hostility against all three groups (1.6%). If we consider all

natives instead of just the Christians, levels of out-group hostility are slightly

lower (8% against Jews, 10% against homosexuals, 21% against Muslims, and

1.4% against all three).

Even though these figures for natives are worrisome enough, they are dwarfed

by the levels of out-group hostility among European Muslims. Almost 60 percent

reject homosexuals as friends and 45 percent think that Jews cannot be trusted.

WZB Report 2014 13Whereas about one in five natives can be considered as Islamophobic, the level

of phobia against the West among Muslims – for which oddly enough there is no

word; one might call it “Occidentophobia” – is much higher still, with 54 percent

believing that the West is out to destroy Islam. These findings concord with the

fact that, as a 2006 Pew research institute study showed, about half of the Mus-

lims living in France, Germany and the United Kingdom believe in the conspira-

cy theory that the 9/11 attacks were not carried out by Muslims, but were or-

chestrated by the West and/or Jews.

Christians Muslims

60 %

50 %

40 %

30 %

20 %

10 %

0%

Don't want Jews cannot The west/Muslims Agree with all

homosexual be trusted aim to destroy three statements

friends

Figure 2

Out-group hostility among native Christians and

Muslim immigrants in Western Europe

Slightly more than one quarter of Muslims display hostility towards all three

out-groups. Contrary to the results for religious fundamentalism, out-group

hostility is more widespread among Muslims of Turkish (30% agreeing with all

three statements) than among those of Moroccan origin (17%). Although the dif-

ference is smaller than in the case of religious fundamentalism, Alevites (13%

agreeing to all three statements) display considerably lower levels of out-group

hostility than Sunni Muslims of Turkish origin (31%). A worrying aspect is again

that while out-group hostility is significantly lower among younger generations

of natives, this is not the case among Muslims.

Here too, we must of course make sure that differences between Muslims and

natives are not due to the different demographic and socio-economic composi-

tions of these groups, since xenophobia is known to be higher among socio-eco-

nomically deprived groups. Multivariate regression analyses indeed show this to

be the case, but controlling for socio-economic variables hardly reduces group

differences. Group differences are moreover much more important than so-

cio-economic ones. For instance, the difference in out-group hostility between

those with low and university levels of education is about half as large as the

difference between Muslims and natives.

This picture radically changes when we take religious fundamentalism into ac-

count, which turns out to be by far the most important predictor of out-group

hostility and explains most of the differences in levels of out-group hostility

between Muslims and Christians. Furthermore, the greater out-group hostility

among Turkish-origin Sunnis compared to Alevites is almost entirely explained

by the higher level of religious fundamentalism among the Sunnis. A further

indication that religious fundamentalism is a major factor behind out-group

hostility is that it is also the most important predictor in separate analyses for

Christians and Muslims. In other words, religious fundamentalism not only ex-

plains why Muslim immigrants are generally more hostile towards out-groups

14 WZB Report 2014than native Christians, but also why some Christians and some Muslims are

more xenophobic than others.

These findings clearly contradict the often-heard claim that Islamic religious

fundamentalism is a marginal phenomenon in Western Europe or that it does

not differ from the extent of fundamentalism among the Christian majority.

Both claims are blatantly false, as almost half of European Muslims agree that

Muslims should return to the roots of Islam, that there is only one interpreta-

tion of the Koran, and that the rules laid down in it are more important than

secular laws. Among native Christians, less than one in 25 can be characterized

as fundamentalists in this sense. Religious fundamentalism among both Chris-

tians and Muslims is, moreover, not an innocent form of strict religiosity as

demonstrated by its strong relationship to hostility towards out-groups.

Both the extent of Islamic religious fundamentalism and its correlates – ho-

mophobia, anti-Semitism and “Occidentophobia” – should be serious causes of

concern for policy makers as well as Muslim community leaders. Of course, re-

ligious fundamentalism should not be equated with the willingness to support,

or even to engage in religiously motivated violence. But given its strong rela-

tionship to out-group hostility, religious fundamentalism is very likely to pro-

vide a nourishing environment for radicalization. Having said that, one should

not forget that in Western Europe, Muslims make up a relatively small minority

of the population. Although relatively speaking, levels of fundamentalism and

out-group hostility are much higher among Muslims, in absolute numbers there

are at least as many Christian as there are Muslim fundamentalists in Western

Europe, and the large majority of homophobes and anti-Semites are still natives.

As a religious leader respected by both Muslims and Christians once said: “Let

those who are without sin, cast the first stone.”

Reference

Koopmans, Ruud: Religious Fundamentalism and Out-Group Hostility among Mus-

lims and Christians in Western Europe. WZB Discussion Paper SP VI 2014-101. Ber-

lin: WZB 2014.

WZB Report 2014 15A Measure for Social Integration M

ixed

Marriages between Muslims and

Non-Muslims Are Accepted but Rare

Sarah Carol

Researchers view mixed marriages and friendships as important indicators of Summary: S tudying intermarriages

the social integration of minorities. Besides the actual marriages and friend- and attitudes toward intermarriage in

ships between Muslims and non-Muslims, attitudes toward them also play an Western Europe provides insights into

important role. In my PhD project at the WZB I examined attitudes toward inter- aspects of social distance between

marriage and the actual marriage behavior of Muslims in six European coun- ethnic minorities and the majority

tries. What are the marriage patterns of the second generation? Is there a gen- population. Overall, the second gener-

der difference regarding the partner search? What roles do parents, the family ation accepts intermarriages to a

and religion play? How do immigration and integration policies affect the search greater extent than the first genera-

for a partner? tion. However, if we look at actual

marriages, we observe the per-

To find out how policy affects the partner search, various international compar- sistence of marriage patterns across

ative data sets were analyzed, especially the WZB’s EURISLAM data set. This in- generations with the majority of mar-

cludes information on about 7,000 people in Belgium, Germany, France, United riages conducted within the family’s

Kingdom, the Netherlands and Switzerland without immigration background, as own ethnic and religious group. Mar-

well as Muslims with Yugoslav, Moroccan, Turkish and Pakistani backgrounds. riage decisions are related to parental

Respondents in the ‘Muslim’ group had at least one Muslim parent. The countries preferences, family values and levels

studied have developed various religious rights and strategies regarding Mus- of religiosity.

lims, so the question was whether Muslims are better integrated in countries

with more liberal religious rights or if the liberal granting of religious rights

reinforces the segregation of religious groups. The analysis shows that neither

granting Muslims religious rights, as in the United Kingdom, nor having a re-

strictive policy, as in Switzerland, forces a return to the individual’s religious

group (‘reactive ethnicity’). Integration policy neither promotes nor hinders so-

cial integration.

Family reunification policies do have an indirect effect on social integration and

the choice of a partner. The Six Country Immigrant Integration Comparative

Survey (SCIICS) shows that children of Turkish and Moroccan immigrants in

Belgium, Germany, France, the Netherlands, Austria and Sweden increasingly

seek partners in the country of immigration, and that making the family reuni-

fication policy stricter leads to fewer transnational marriages (to people from

the parents’ country of origin) and more marriages within the ethnic communi-

ty living in the same country of residence.

Among the main factors that influence the partner search are the prospects and

the size of the local marriage market. Pakistani immigrants in particular, who

constitute just a small share of Muslims in Western Europe (except in the United

Kingdom), fall back on help from family networks. Still, only a fraction of mar-

riages are arranged. In the second generation, hybrid forms can be observed, in

which children search for suitable partners with their parents. When many im-

migrants from the same country live in proximity, partners tend to be chosen

from their own group. Especially for the second generation, this pool offers

more possibilities of finding a partner who was similarly socialized, and who

generally is less religious.

Transnational marriages offer highly qualified women the chance of finding

a partner. Scientifically, this is interpreted as a strategy for emancipation

because the geographic distance of transnational marriages allows women

to live apart from the groom’s family, which traditionally incorporates a

bride into the household. Analysis shows that women with and without im-

16 WZB Report 2014migrant backgrounds tend to be more protected by their families than men,

which results in lower rates of interethnic marriages. Religious groups

sometimes interpret a woman’s marriage as a partial loss, because they as-

sume that the husband’s religion will prevail and be transmitted to the next

generation.

Marriage Patterns Remain Stable

Closer examination of interethnic and interreligious relationships shows that,

contrary to theory, interethnic marriages are not generally more frequent in

the second generation when educational differences are taken into consider-

ation, although Muslim members of the second generation clearly have more Sarah Carol i s researcher in the WZB research unit

positive attitudes than their parents toward marriages between Muslims and Migration, Integration, Transnationalization. Her main

non-Muslims. research fields are social integration of immigrants

and interethnic friendships and marriages (see also

her article p. 19-21). [Photo: David Ausserhofer]

Why do marriage patterns remain stable? Parental preferences for a specific sarah.carol@wzb.eu

marriage partner play a role in social integration, regardless of the children’s

age. The influence of ethnic communities and parental socialization goals are

closely linked. For immigrant children, education does facilitate their emancipa-

tion from predefined structures and their parents’ views of marriage, but social-

ization in school does not automatically lead to social integration, and the sense

of being discriminated against makes integration more difficult.

Equally important is the role of parents without immigrant backgrounds who

influence their children’s interaction with ‘immigrant’ children. Middle-class

parents tend to control their children’s free time and social contacts more than

parents from higher or lower walks of life. Since the social status of children

with immigrant backgrounds is often below that of the receiving society, par-

ents without immigrant backgrounds may associate interethnic contact with

social decline and be more concerned about their children than better-off par-

ents who send their children to exclusive schools, where there is almost no

contact with immigrant children. The lack of opportunity for children and young

people with and without immigrant backgrounds to develop close friendships

subsequently affects their partner choice.

Beyond the major role that parents play in relation to children’s social integra-

tion, various forms of religiosity and family values are linked to fewer inter-

marriages and more negative attitudes toward intermarriage. Religious practice

that includes observing dietary rules and holidays, as well as wearing religious

symbols, plays a larger role than simply self-identifying with a religion. This

connection is more pronounced for some groups than others. In particular, im-

migrants from secular former-Yugoslavia are confronted with less acceptance

of intergroup relationships on the part of the receiving society, while immi-

grants from more religious countries like Morocco and Pakistan indicate less

willingness to marry someone from the receiving society. This can be explained

by their greater religiosity.

Besides religiosity, ethnic differences are mainly explained by family solidarity.

Muslim immigrants cultivate especially close parent-child relationships in

which adult children assume responsibility for their parents, demonstrate their

respect, accept their authority and consider it more important to protect the

family’s reputation than do children without immigrant backgrounds. Not only

are the actual differences in cultural and religious values significant, but per-

ceptions can also affect social distance: The more differences individuals per-

ceive with regard to religiosity, parent-child relationships and pre-marital sex,

the less likely they are to accept marriage with a Muslim (or a non-Muslim).

Thus the dividing line between groups runs along family values and religiosity.

This divide might explain why the divorce rate of interethnic couples is higher

than those of ethnically homogeneous couples. But describing that precisely, as

well as the consequences of intergroup relationships, must be left for future

research. Earlier studies have indicated that interethnic marriages positively

affect the integration of people with immigrant backgrounds into the job

market.

WZB Report 2014 17The integration of people with immigrant backgrounds is a bilateral process that is influenced by many factors. Both on the part of the receiving society and among immigrants, resentment of intergroup relationships remains. My work has shown how different family values, gender concepts and religiosity help explain this situation. As a driving force of integration, education creates the conditions for people with immigrant backgrounds to establish contacts. But the openness of the family of origin and the ethnic community are also important, as is acceptance by the receiving society. References Carol, Sarah: Is Blood Thicker Than Water? The Role of Family and Gender Values for the Social Distance between Muslim Migrants and Natives in Western Europe. Doc- toral Dissertation. Berlin: Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin 2013. Carol, Sarah: “Intermarriage Attitudes among Minority and Majority Groups in Western Europe: The Role of Attachment to the Religious In-Group.” In: International Migration, 2013, Vol. 51, No. 3, pp. 67-83. Carol, Sarah/Ersanilli, Evelyn/Wagner, Mareike: “Spousal Choice among the Children of Turkish and Moroccan Immigrants in Six European Countries: Transnational Spouse or Co-ethnic Migrant?” In: International Migration Review, 2014. DOI: 10.1111/imre.12068. 18 WZB Report 2014

Religion Matters Faith and its Practice

Influence Coexistence More Than Gener-

ally Assumed

Sarah Carol, Marc Helbling and Ines Michalowski

These days, when someone in Western Europe speaks about ‘migrants’ they usu- Summary: T wo WZB surveys ques-

ally mean immigrants from Muslim countries who make up most of the immi- tioned Muslims and non-Muslims

grant population in most West European countries. In the past two decades, the about their attitudes toward the other

most heated debates regarding immigrants and their integration have been group and religious symbols. It was

about Muslim religious practices, such as wearing a headscarf, or about houses shown that most people make clear

of worship like mosques, and especially minarets. Now secular societies of West- distinctions between Muslims as a

ern Europe are finding themselves confronted by completely new challenges: group and religious practices such as

Which religious practices can be tolerated and how can liberal values be main- wearing a headscarf. These distinc-

tained? tions can partly be explained by the

respondents’ values, religiosity, gen-

Given the urgency of this matter, it is surprising how little is known about West- der and attitudes towards gender dif-

ern European attitudes with regard to these challenges, and which religious ferences. The state-church relation-

rights Muslims themselves consider important. Most studies have focused on ship also plays a major role.

political discussions about Islam and Muslim integration. Despite the numerous

surveys about migration, attitudes towards Muslim migrants and their religious

practices have hardly been explored.

To close this research gap, the WZB’s Migration and Diversity research area re-

cently conducted two surveys on native and Muslim immigrant attitudes about

immigration and integration in Western Europe:

The EURISLAM Telephone Survey questioned some 7,000 people with and with-

out immigrant background in six countries – Belgium, Germany, France, the

United Kingdom, the Netherlands and Switzerland. The respondents with immi-

grant background had Muslim roots in ex-Yugoslavia, Morocco, Turkey and Paki-

stan. International comparisons were made about the attitudes of Muslims and

non-Muslims regarding religious symbols such as a Christian nun’s habit and

Muslim headscarves, as well as religious education.

The “Six Country Immigrant Integration Comparative Survey (SCIICS)” compared

the attitudes of 500 natives of Belgium, Germany, France, the Netherlands, Aus-

tria and Sweden (3,000 altogether) toward Muslims in general, and toward head-

scarves in school in particular.

The study sought to discover to what extent a difference is made between the

group as such and its religious practices.

Most attitudes to Muslims were fairly tolerant. However, most respondents re-

jected schoolgirls wearing headscarves. The second stage of the study investi-

gated this difference and revealed that attitudes regarding Muslims and the

headscarf have to do with the respondents’ liberal values and religiosity.

People with liberal values were found to be more positive toward Muslims than

people with conservative values, which corroborates numerous studies showing

that liberal values make for greater openness towards immigrants. However,

whether people with liberal values are actually tolerant of alien cultures or only

of those things that do not conflict with their liberal values is hotly debated.

Some people view religion itself as conflicting with a liberal state; even more

view the Muslim headscarf as a sign of a woman’s oppression. The study also

revealed that people with liberal values tend to be skeptical of the headscarf.

WZB Report 2014 19You can also read