Urban Contractual Policies in Northern Europe - Lukas Smas with contributions from Christian Fredricsson, Liisa Perjo, Tim Anderson, Julien ...

←

→

Page content transcription

If your browser does not render page correctly, please read the page content below

Urban Contractual Policies in Northern Europe Lukas Smas with contributions from Christian Fredricsson, Liisa Perjo, Tim Anderson, Julien Grunfelder and Christian Dymén N O R D R E G I O W O R K I N G PA P E R 2 0 1 7 : 3

Urban Contractual Policies in Northern Europe

Lukas Smas with contributions from Christian Fredricsson, Liisa Perjo,

Tim Anderson, Julien Grunfelder and Christian DyménUrban Contractual Policies in Northern Europe Nordregio Working Paper 2017:3 ISBN: 978-91-87295-47-8 ISSN: 1403-2511 © Nordregio 2017 and the authors Nordregio P.O. Box 1658 SE-111 86 Stockholm, Sweden nordregio@nordregio.se www.nordregio.se www.norden.org Editor: Lukas Smas with contributions from Christian Fredricsson, Liisa Perjo, Tim Anderson, Julien Grunfelder and Christian Dymén Nordic co-operation Nordic co-operation is one of the world’s most extensive forms of regional collaboration, involving Denmark, Finland, Iceland, Norway, Sweden, and the Faroe Islands, Greenland, and Åland. Nordic co-operation has firm traditions in politics, the economy, and culture. It plays an important role in European and inter- national collaboration, and aims at creating a strong Nordic community in a strong Europe. Nordic co-operation seeks to safeguard Nordic and regional interests and principles in the global community. Common Nordic values help the region solidify its position as one of the world’s most innovative and competitive. The Nordic Council is a forum for co-operation between the Nordic parliaments and governments. The Council consists of 87 parliamentarians from the Nordic countries. The Nordic Council takes policy initiatives and monitors Nordic co-operation. Founded in 1952. The Nordic Council of Ministers is a forum of co-operation between the Nordic governments. The Nordic Council of Ministers implements Nordic co-operation. The prime ministers have the overall responsibility. Its activities are co-ordinated by the Nordic ministers for co-operation, the Nordic Committee for co-operation and portfolio ministers. Founded in 1971. Nordregio – Nordic Centre for Spatial Development conducts strategic research in the fields of planning and regional policy. Nordregio is active in research and dissemina- tion and provides policy relevant knowledge, particularly with a Nordic and European comparative perspective. Nordregio was established in 1997 by the Nordic Council of Ministers, and is built on over 40 years of collaboration. Stockholm, Sweden, 2017

Table of Contents Preface .............................................................................................................................................................................. 6 1. Introduction ................................................................................................................................................................. 7 2. Finland: Letters of intent ......................................................................................................................................... 9 3. Norway: Contracts and agreements ................................................................................................................... 13 4. Sweden: Negotiations and agreements............................................................................................................. 20 5. Comparing the Nordic cases ................................................................................................................................ 24 6. France: Urban and regional contracts ............................................................................................................... 26 7. England: Local enterprise partnerships and ‘City Deals’ ............................................................................. 30 8. European outlooks and insights ......................................................................................................................... 34

Preface This working paper is based on two separately commis- 6 to 8, which incorporate additional comparisons and sioned projects that Nordregio carried out during critique of urban policies in France and, especially, the 2015–2016. The first project was commissioned by the UK. Nordic Working Group for Green Growth: Sustainable The projects were a collaborative undertaking, with Urban Regions set up under the Nordic Council of a number of national experts at Nordregio involved. Ministers’ Committee of Senior Officials for Regional Lukas Smas was the overall co-ordinator and editor. Policy (EK-R). This project relates to Chapters 2 to 5 of Liisa Perjo was responsible for Finland, Christian Fre- the present working paper, which describe the policy dricsson contributed the Norwegian part and Chris- details and inner workings of urban contractualism in tian Dymén (now at Trivector) was responsible for Norway, Sweden and Finland. The second project was Sweden. Julien Grunfelder was responsible for France commissioned by the Norwegian Ministry of Local while Timothy Andersson (currently a PhD Student Government and Modernisation. The objective was to at Tallinn University) wrote the UK section alongside review the experiences in France and England with dif- contributions to the introduction and conclusion. ferent forms of contractualism. This relates to Chapters 6 N O R D R E G I O W O R K I N G PA P E R 2 017 : 3

1. Introduction

The co-ordination and integration of transport, land- economic and political rationales behind these often

use and housing planning has emerged as an important complex organizational and financial arrangements

policy direction to promote sustainable development are, however, beyond the scope of this descriptive

in the Nordic countries. To facilitate sectorial co-ordi- analysis. Instead, we offer a brief comparative overview

nation and integration, different types of multi-level and review how these contractual agreements relate to

arrangements between state authorities, regional bod- other formal (municipal and regional) spatial planning

ies and local municipalities have been developed. For- processes: a critical policy (and research) question.

mal and informal agreements between state (national) Within our analysis, we explore contractualism as an

authorities and municipalities regarding sectorial poli- emerging policy development in Finland, Norway,

cies in areas such as transport and infrastructure are Sweden, France and the UK. Our examples provide

not a new or unusual phenomenon. However, what is multiple perspectives on how urban contractual policy

interesting is the combination of cross-sectorial and is developing in Northern Europe.

multi-level governance, along with the adoption of dif-

ferent types of contractual or agreement-based policies Contractualism and spatial planning

among various public authorities (i.e. public–public- The term contractualism has been used to describe a

relations). These different ‘agreement-based urban pol- model of relations between states and citizens within

icies’ or ‘contractual urban polices’ that are emerging neo-liberal society, with implications for governance. It

in Finland, Norway and Sweden are also becoming in- is not a self-evident concept, and the different potential

stitutionalized. formulations of social, moral and political contracts

Urban contractual policy is a key instrument for have been the subject of much debate within social sci-

the Norwegian Government to steer urban develop- ence. In political science, ‘new contractualism’ has been

ment towards the goal of zero growth in car traffic. The discussed within the context of European social policy,

multi-level agreement is a strategic instrument to co- with some scholars contending that ‘contractual think-

ordinate actors and policy measures, including various ing emphasizes… citizens’ own responsibility for their

forms of financing under a common policy framework. welfare’ (Ervik et al., 2015, p. 2). More broadly, there is

In Finland, contracts entitled ‘letters of intent’ have discussion of ‘chains of contracts’ where the individual is

been developed in recent years for land use, housing at the end of a chain (Jayasuriya, 2002), while private fi-

and transport (2012-2015). The aim of these has been to nance initiatives and public–private partnerships (PPPs)

create integrated, efficient and competitive urban city- are links in themselves. For example, British ‘workfare’

regions via co-operation between the state and munici- policies linked to neo-liberal contractualism have sig-

palities in the city-regions. During 2015, urban envi- nificantly restructured ‘the relationship between state

ronment agreements were also introduced in Sweden. and citizen’ (Jayasuriya, 2002, p. 309). This has also lead

This working paper provides an introduction to to criticism of the private-sector focus of European Un-

these new developments including contractual urban ion (EU) ‘contractual governance’, with a warning that

policy initiatives in Finland, Norway and Sweden. such deals pose a threat to democratic and representa-

It also compares these with developments in France tive processes of regional development (Jayasuriya 2002,

and the UK. The Nordic urban contractual policies p. 309). Other researchers have focused on the way in

reviewed here seek to integrate land use, housing and which contractualism and neoliberalism have been

transport, i.e. they are cross-sectorial arrangements. linked together, arguing that contractual governance

They have also been established primarily in order to ‘has been problematic in that many contracting regimes

promote sustainable urban development. Furthermore, have failed to respond adequately to public needs’ (Vin-

institutionalization of these urban contractual polices cent-Jones, 2007, p. 259).

in the Nordic countries is increasing through new na- In the realm of spatial planning, ‘contractualism’

tional regulation and funding schemes. The multiple and ‘deal-making’ as concepts are frequently consid-

N O R D R E G I O W O R K I N G PA P E R 2 017 : 3 7ered to be important facets of neo-liberal discourse tual arrangements between different public authorities,

(e.g. Sager 2011). The significance of contractualism for i.e. public-to-public relations. In this explorative and

planning is multifaceted and obvious. Raco (2013), for descriptive paper, the term urban contractual policy

example, within an article about planning and contrac- is thus broadly defined to encompass the new types

tualism in the UK, claims: of deals, agreements and contracts emerging in some

planning domains.

The broader rationality for a planning system This study details contractual policies from five Eu-

that integrates and co-ordinates the provision of ropean countries—Finland, Norway, Sweden, France

infrastructure and welfare services across nation- and England—and offers a view of urban policy evolu-

al and regional spaces is undermined in a context tion in these places. For the cases that we address here,

where contracts shield private interests from contractualism functions (ostensibly) as a mechanism

changing public values and sensitivities. to ‘minimize the costs of governance while encourag-

(2013, p. 60) ing greater co-operation between principals and agents

to maximize their joint utility’ (Wiseman et al., 2012,

There are a number of studies that examine contractu- p. 210).

alism in relation to planning with a focus on public– The objective of this working paper is to map the

private relations. For example, Haila (2008) offers a current use of urban contractual policies and to explore

case study of contracts and property development in how these contracts are structured and organized, in-

Finland. However, less attention has been given to con- cluding how responsibilities are divided between tiers

tractual agreements between public institutions, such of government (local, regional and national). Another

as contracts developed between state authorities and objective is to further understand what types of cri-

municipalities. teria are used for selecting the projects; what types of

The contractual policies considered in this paper, policy measures are included; what type of financial

such as those that are emerging in the Nordic coun- models are used; and how the contracts are evaluated.

tries, are of this different type. They are primarily not The paper aims to initiate and facilitate a discussion on

related to the relations between state and citizen or be- the challenges and potentials accompanying the emer-

tween public and private actors, but are about contrac- gence of urban contractual policy in the Nordic region.

8 N O R D R E G I O W O R K I N G PA P E R 2 017 : 32. Finland: Letters of intent

Integration of land use, housing and transport has Topic and goals

been a notable planning trend in Finland since year

The aim of the LOIs during the period 2012–2015 was

2000 (Mäntysalo et al., 2014). The state has also been

to guide the integration of land use, housing and trans-

promoting an increased city-regional perspective in

port policies in the largest city-regions. Integration of

planning and increased city-regional co-operation has

housing and transport (e.g. locating housing close to

been taking place over recent decades (Kanninen &

public transportation) is seen as a way to avoid the ur-

Akkila, 2015). Linking together these trends of policy

integration and city-regional perspectives, urban con- ban sprawl that was one of the main concerns of Finn-

tractual policy between the state and city-regions has ish spatial planning in the 2000s. In addition to devel-

been established to support integration of land use, oping denser urban structures, promoting the

housing and transport, as important areas for city-re- integration of land use, housing and transport was

gional co-operation, and for co-operation between thought to foster sustainable development and facili-

city-regions and the state. Agreements between the tate well-functioning everyday life in the city-regions,

state and municipalities in city-regions were called which are also functional labour market areas. Access

‘Letters of intent for land use, housing and transport’ to affordable housing was also emphasized (MAL,

(LOIs) between 2012 and 2015, and were aimed at more 2015).

integrated planning of land use, housing and transport According to the mid-term evaluation of the LOI

with improved focus on these topics at a city-regional period 2012–2015, the objective was a policy tool that

level. Agreements covering the period 2016-2019 are would encourage municipalities to adopt joint meas-

called ‘Agreements on land use, housing and trans- ures taking into consideration city-regional outcomes,

port’. This overview discusses only the LOIs during the instead of focusing on benefits for each municipality

period 2012–2015. (MAL, 2014). The aim was to promote co-operation be-

The need for this type agreement between the state tween municipalities and decrease competition within

and the city-regions arose because regional level plans the city-region (Tuominen, 2015). At the same time,

were not considered sufficient to meet the specific chal- LOIs were established as an instrument for multi-level

lenges of the regional growth centres (i.e. the larger governance in the sense that they were used to ensure

city-regions), while municipalities, in turn, did not the implementation of state-level policy goals at the

take into consideration the city-regional perspective in city-regional level (MAL, 2014).

their municipal plans (Ojaniemi, 2014). It was felt that The contents of the LOIs differed between city-re-

this led to overlapping investments and, among other gions based on needs that the participating municipali-

things, urban sprawl. The LOI on land use, housing ties and the state had agreed on. In the Helsinki metro-

politan city-region, the focus was on housing because

and transport, as a policy tool between the state and

of the city-region’s challenges regarding the provision

city-regions, was seen as a way to address such chal-

of affordable housing. The city-regions of Oulu, Tam-

lenges (Ojaniemi, 2014).

pere and Turku focused more on cohesive or densified

The first LOI relating to land use, housing and trans-

urban structures and sustainable mobility (interview

port was established between the state and the Tampere Mäkelä, 2015). In the Oulu city-region, issues of service

city-region in 2011 as a pilot agreement. The Tampere provision structure and business were also included.

city-region was chosen as the pilot city-region because During the programme period, 2012–2015, it was of-

of its well-established inter-municipal co-operation. ten debated whether the LOIs should be broadened

After the pilot, a longer-term LOI was drafted for Tam- to include other development issues or if they should

pere as well as for the city-regions of Helsinki, Turku remain focused on integrating land use, housing and

and Oulu. (MAL, 2015; interview Mäkelä, 2015). transport.

N O R D R E G I O W O R K I N G PA P E R 2 017 : 3 9Partners and process example, in the Turku city-region, one of the more pe- In principle, the LOIs were signed by each municipality ripheral municipalities decided not to enter the agree- in a city-region, and the state. In the agreements, the ment during the first round even though it had been state was represented by the Ministry of the Environ- part of the negotiations (interview Mäkelä, 2015). ment (which also co-ordinated the policy), the Minis- try of Transport and Communications, the Housing Relation to other plans and the Land Use and Finance and Development Centre, and the Finnish Building Act Transport Agency. The Centres for Economic Develop- As LOIs (and now the agreements on land use, housing ment, Traffic and the Environment were state repre- and transport) are made between the municipalities in sentatives at the regional level (Ministry of the Envi- a city-region and the state, they operate on a city-re- ronment, 2015). The contracts could include other gional level, i.e. between the formal municipal and re- actors if they were responsible for some of the included gional planning levels. These types of agreements are measures (MAL, 2015). Some LOIs, for example, in- outside the formal planning system and not legally cluded regional councils as partners. The involved city- binding for the partners, although active discussions regions were chosen by the state: so, for example, the have been taking place on ways to improve commit- city-region of Lahti expressed interest but the govern- ment and make them more binding. It has been noted ment decided to include only the four largest city-re- the role of LOIs relative to the regional level and the gions and excluded Lahti (interview Mäkelä, 2015). planning system as a whole remains unclear (Mänty- In the process of establishing an LOI, the munici- salo et al., 2014). In interviews, a majority of city-re- palities of a city-region first formed a common un- gional and state actors stated that they did not wish derstanding of the aims of the city-region, and based LOIs to be legally binding (Ojaniemi, 2015). on the city-regional goals, negotiations with the state LOIs, as strategic documents, link to other plans were commenced (MAL, 2015). The LOIs were also ap- and strategies at municipal, city-regional, regional and proved by the municipal councils before being signed national levels (see Figure 1). City-regional structure by the municipalities and the state (MAL, 2015). For models or other existing city-regional land-use plans Figure 1. Organizational structure of LOIs 10 N O R D R E G I O W O R K I N G PA P E R 2 017 : 3

and traffic plans were commonly used as the basis for increase their housing plan spending by 25% between

LOIs. As there is no legally binding city-regional plan- 2015 and 2019, compared to the amount stated in the

ning in Finland, the plans and models that are the basis existing LOI, as a counter performance to the funding

for LOIs are themselves also non-binding. The work- received for the larger infrastructure projects.

ing group on LOIs noted that making city-regional

structure models more binding could strengthen city- Lessons learnt

regional planning. (MAL, 2015) LOIs were evaluated as a policy tool, as were the imple-

While LOIs focus on creating a shared inter-munic- mentation and goal achievement of each individual LOI.

ipal city-regional vision on issues of land use, housing Assessment of goal achievement is considered important

and transport, issues like international competitiveness even though there are no consequences in case of failure

are the subject of growth agreements. There has been to reach the goals. While evaluation requires significant

some discussion, in various evaluation reports, about resources, a focus on the key areas, and limiting the is-

combining LOIs and growth agreements as they partly sues included, could increase the efficiency of the LOI

overlap (e.g. MAL, 2015). It would be challenging to evaluation procedures (MAL, 2015). Measuring out-

combine land-use, housing and transport issues with comes and evaluating the LOIs is, however, expected to

business and competitiveness issues because an even remain challenging as the development processes to be

larger variety of actors would be involved and because monitored are of long duration compared to the relative-

the issues to be solved are different in the different con- ly short LOI periods (Mäntysalo & Kosonen, 2016). En-

tracts (interview Mäkelä, 2015). Current thinking is tire LOIs have not been fully evaluated, but individual

that LOIs and growth agreements should be drafted si- infrastructure projects, which are implemented as part

multaneously but result in separate agreements (MAL, of the LOIs, are evaluated in the ordinary way through,

2015). for example, environmental impact assessments (inter-

view Mäkelä, 2015).

Funding mechanisms Evaluations show that the LOI process initiated dia-

The LOIs included areas for which the city-regions logue across administrative and policy-sector bounda-

would receive funding from state level independent of ries. It provided a forum for discussion through which

the LOI (e.g. state funding for affordable housing). State municipalities in city-regions could create common vi-

funding was then allocated in line with the details of sions. It also improved dialogue between city-regions

the LOI. However, there was also some LOI funding and the state, as well as between the various state ac-

(approx. EUR 30 million in total in two years), allocated tors working with city-region-level topics, which often

specifically through the LOIs, that was mainly directed spanned different policy sectors (MAL, 2015; Ojaniemi,

towards small cost-efficient traffic projects often related 2014). The LOIs also improved understanding among ac-

to supporting cycling, walking and public transport tors of the importance of linking together transport and

(Mäkelä, 2015). In addition to providing some addi- housing-related goals (MAL, 2015).

tional funding, the policy instrument was particularly One of the major challenges in the period 2012-2015

important in providing a common forum in which mu- concerned the commitment of the state to implementing

nicipalities could discuss land use, housing and trans- the LOIs. The involved ministries cannot make binding

port, and in strengthening the dialogue between city- contracts as budgets are decided annually by the gov-

regions and the state (interview Mäkelä, 2015). In order ernment and the parliament (interview Mäkelä, 2015,

to receive the funding, the municipalities of a city-re- Ojaniemi, 2014). When the state cannot commit to the

gion, together, had to provide the same sum as the state goals set up in the LOIs, making funding insecure, there

(50/50 funding between state and the municipalities of are negative effects on the trust and commitment of the

the city-region) (interview Mäkelä, 2015). municipalities (Ojaniemi, 2014) As a possible solution,

Larger projects are generally discussed by the gov- it has been suggested that the Ministry of Finance, as it

ernment and the parliament in annual national budget is responsible for preparing the state budgets and also

negotiations (interview Mäkelä, 2015). State funding has responsibility for municipal issues, should be more

for large infrastructure projects was however notion- closely involved in the agreements (MAL, 2015).

ally added to the LOIs in the Helsinki and Tampere Shifts in national government and municipal coun-

city-regions, but was not part of the LOIs as such and cils has been another challenge as changes in policy pri-

funding was not granted through them. For example, in orities, at both local and national levels, can affect the

the Helsinki metropolitan region there was a separate implementation of the LOIs. Furthermore, national and

agreement between the city-region and the state about municipal elections do not take place at the same time,

infrastructure projects. The municipalities agreed to and so national and municipal priorities may be refor-

N O R D R E G I O W O R K I N G PA P E R 2 017 : 3 11mulated at different times. One suggestion has been to by the strong role of municipal borders. In some cases,

bind the LOI periods to national government working providing ‘something for everyone’ has been prioritized

periods (Ojaniemi, 2014). over the benefits for the city-region as a whole. (Mänty-

Other issues discussed in evaluations related to the salo & Kosonen, 2016).

topical scope of the LOIs and the involvement of dif- In general, the role of the LOI and planning at city-

ferent actors. There are different opinions on the ideal regional level, in relation to the planning system and the

scope of the LOIs and which topics to include, which Land Use and Planning Act, remains uncertain. Mänty-

also means varied opinions on which actors to involve salo & Kosonen (2016) see the LOI as an element of a new

(MAL, 2015; Ojaniemi, 2014). For example, concern- form of governance where the key actors belong to the

ing stakeholders, it has been suggested that developers traditional government at different levels, but in which

should be involved in negotiations related to housing. the mode of working is through networked governance

Citizen involvement is another topic of discussion. Since slightly outside the formal planning system. This is illus-

the LOIs are approved by elected municipal councils, it trated, as an example, by the appearance of a new city-

is argued that the negotiations do not need to include di- regional planning level that is not an institutional actor

rect citizen participation (interview Mäkelä, 2015). Some itself, but lies between institutional actors with planning

actors, however, have the view that some topics within mandates at local and national levels. In research on at-

the LOIs require citizen participation (e.g. traffic system titudes to LOIs, actors in general consider them as useful

planning) (interview Mäkelä, 2015). tools with good development potential: in particular, in

Evaluators believe that the LOI tool has not succeed- providing a forum for dialogue between municipalities,

ed in creating sufficient shared understanding of city- between city-regions and cities and between policy areas

regional structures, and that their success is still limited (Mäntysalo & Kosonen, 2015).

12 N O R D R E G I O W O R K I N G PA P E R 2 017 : 33. Norway: Contracts and

agreements

Urban contractual policy in Norway can be seen as a growth in car traffic. This objective arises from the par-

national policy response to specific challenges in larger liamentary climate agreement (adopted in 2012), in

urban regions. The arguments for introducing urban which it was agreed that all new personal transport in

contractual polices are: increased pressure to manage urban regions should be by public transport, cycling or

land-use planning and transport at the city-region walking. In this context, the UECs are a strategic poli-

scale, and the challenges of co-ordinating planning be- cy instrument to co-ordinate actors, policy measures/

tween the state, regions and municipalities (Norheim instruments and various forms of financing under a

2013). Traditionally, land-use and transport policy- common policy framework. UECs are a new form of

making has been fragmented, but today, national poli- collaborative agreement specifically targeted, by the

cy aims at creating a more cohesive framework for col- Norwegian Government, at the nine largest city-re-

laboration between administrative levels on land use, gions: Oslo, Bergen, Trondheim, Stavanger, Buskerud-

transport and housing. byen (Drammen), Nedre Glomma (Fredrikstads/

Norwegian urban contractual policies consist of Sarpsborg), Grenland (Porsgrunn/Skien), Kristian-

mixed instruments. Key policies are implemented sand and Tromsø. A separate contract was negotiated

under two different and complementary frameworks: with each city-region with goals consistent with the

urban environment contracts (UECs – in Norwegian: NTP (See requirements in Figure 2).

bymiljøavtalene) and urban development agreements UECs can also be described as long-term political

(UDAs – in Norwegian: byutviklingsavtalene). In re- intention agreements. They are not legally binding for

cent years, different organizational forms of contract the involved contractual parties. However, they also

have been investigated and debated in the public policy bring together some existing financial instruments

sphere, even though Norway has a tradition of contrac- for transport infrastructure in Norway, i.e. the urban

tual processes in transport packages, e.g. for the Oslo reward fund (in Norwegian: Belønningsordningen

region, which includes Oslopakke 1 negotiated in the for bedre kollektivtransport og mindre bilbruk i by-

1980s and Oslopakke 2 in the 2000s, and in other ur- områdene) and city packages (in Norwegian: Bypa-

ban regions. kker), under one framework. The urban reward fund

Policies within UECs and UDAs should comple- aims to encourage better accessibility, safety and health

ment each other, but they are implemented under sepa- in the larger urban regions by reducing growth in the

rate organizational structures. UECs are implemented number of car users and by increasing the number of

under the National Transport Plan, with the aim of co- public transport passengers. These policy instruments

ordinating transport investments with urban develop- were intended to be gradually phased in under UECs,

ment in the larger urban regions, while UDEs are fo- as a common umbrella, with the objective of a compre-

cused around the implementation of regional land-use hensive national transport policy. The form of financ-

and transport plans. The following sections describe ing is decided in the contractual process. In total, the

the different organizational structures in more detail Norwegian Government has set aside NOK 16.9 bil-

(interview Leite 2015; Bårdheim, 2014; Ministry of lion over the upcoming planning period for UECs and

Transport and Communications, 2013). NOK 9.2 billion for the urban reward fund (Ministry of

Transport and Communications, 2013). The funding of

Urban environment contracts urban development will increase, in contrast to urban

UECs were initially presented in 2013, in the National reward funds that will remain unchanged until 2023

Transport Plan 2014–2023 (NTP), as one the main pol- (Bårdheim, 2014).

icy instruments for the Norwegian Government to The Norwegian Ministry of Transport and Com-

steer urban development towards the objective of zero munications has overall responsibility for the imple-

N O R D R E G I O W O R K I N G PA P E R 2 017 : 3 13Figure 2. General requirements for UECs

UECs: general requirements and framework

Conceptual route investigation Land-use planning

• Conceptual route investigation (KVU) and QA1 are • A regional or inter-municipal land-use plan is adopted

implemented. or under adoption/revised in line with the objectives

• By KVU and KS1 is it visible that all new passenger of the national urban contractual policy, and has an

transport is taken by public transport, bicycle or walk- objective of concentrated land-use development

ing. centred on transport hubs and more public transport,

• Large projects with a budget of over NOK 750 mil- bicycle and walking. A requirement is for the guiding

lion require the submission of a quality assured cost principles of regional or inter-municipal plans to be

report (KS2) to the parliament. followed up in municipal land-use planning.

Goals and policy areas Financing

• Climate policy states that all growth in passenger • User fees as a contribution to financing are resolved.

transport should be by public transport, bicycle and Necessary decisions are taken at local and regional

walking. level in line with the requirements for ordinary toll

• Long-term goals and short-term goals are adopted. packages.

• Local adopted goals are harmonized with national • The contribution to financing of different administra-

goals. tive levels is specified and adopted locally. The state

• Main policy areas are clarified between involved ac- adopts the final decision in the Parliament.

tors. • Operation of public transport services is decided.

• The introduction of restrictive measures must be

clarified.

Monitoring process

• System of implementation process and monitoring of

economy.

• Indicator system for objectives.

Source: National Transport Plan 2014–2023

mentation of the UECs, but the task is delegated to the tive of ensuring that all growth in personal transport

Norwegian Public Roads Administration. A designat- should consist of public transport, cycling or walk-

ed steering group is responsible for organizing nego- ing. The regional council and municipalities must also

tiations between the involved actors (national, regional commit to a land-use policy that supports the devel-

and local) and its members are from the Norwegian opment of public transport, cycling or walking. In the

Public Roads Administration, the Norwegian Govern- negotiation process, the steering group is responsible

ment’s Agency for Railway Services, regional county for developing a plan for how traffic and environmen-

councils and municipalities. The County Governor tal challenges in urban area should be solved in the

has observer status in the steering group. The steer- short and long term. According to the NTP, the state

ing group is supported by a secretarial office that co- should act as a facilitator and urge the local authorities

ordinates operational activities and is responsible for to adopt ambitious objectives. In addition, the locally

the negotiation process with regional county council adopted objectives should be harmonized with nation-

and the municipalities. In particular, the secretariat al objectives and support the overarching objective in

conducts the necessary investigations and prepares all the climate agreement. The objectives should be quan-

decision-support material. The political steering group tified, time-bound and verifiable, and should also be

then decides on what decisions should be taken to the part of an overall transport policy that contributes to

county parliament and the city councils. national goals (Ministry of Transport and Communi-

The NTP describes the premises and framework for cations, 2013) (A full list of the requirements of UECs

initiating UECs. The plan emphasizes that this is an is outlined in Figure 2.) By funding urban environment

objective and result-oriented process which prioritizes contracts, the state offers the municipalities a 50% gov-

policy measures that support the underlying objec- ernmental investment grant for large public transport

14 N O R D R E G I O W O R K I N G PA P E R 2 017 : 3Figure 3. Organizational structure of urban environment contracts

investment projects within the framework of the NTP. ment for the development and financing of public

The UEC scheme is in its initial phase. In 2015, Oslo- transport in Oslo and Akershus. Adopted in 2012, it

Akershus and Trondheim began contract negotiations, built on previous agreements, Oslopakke 1 and 2. Os-

while Stavanger and Bergen began talks in 2016. How- lopakke 1 was approved in 1988 and included, for ex-

ever, city packages and urban reward funds have been ample, funding for the introduction of an urban toll

used already in these regions (Oslopakke 3 in Oslo- ring road around Oslo. Oslopakke 2 was approved in

Akershus, city package Nord-Jæren in the Stavanger 2002 and mainly financed investments in public trans-

Region, environmental package in Trondheim and the port. Oslopakke 3 is one of the largest financial agree-

Bergen package in Bergen). All four regions have been ments on public transport in Oslo-Akershus, with an

considered for funding from the reward fund. economic framework totalling NOK 75 billion over the

Oslopakke 3 is an overarching contractual agree- period 2013–2032. It includes a metro extension and

Figure 4. Overview of transport packages in Oslo

N O R D R E G I O W O R K I N G PA P E R 2 017 : 3 15major road projects (Statens Vegvesen 2015). The Nor- a partner in Oslopakke 3. wegian Ministry of Transport and Communications Administrative Coordination Group – This consists has suggested that the organizational model of Oslop- of members from the four partners in Oslopakke 3. The akke 3 be used by other city-regions implementing a group is, together with the secretariat, responsible for UEC. It is therefore interesting to take a closer look at developing decision-support documents for the steer- how the contractual process has been organized. The ing group. Directors are directly involved in the co- role of each actor is explained below and visualized in ordination group. Figure 5. Expertise Coordination Group - This group consists As mentioned, Oslopakke 3 has been put forward of experts involved in the planning and implementa- as a model for implementing UECs. Currently, Bergen tion of Oslopakke 3 policy measures. All four main is developing a new UEC with Oslopakke 3 as its role partners are involved, plus representatives from the model. public transport authority for Oslo and Akershus, Steering Group - The steering group includes the four Norwegian State Railways and the urban environment main partners involved in the contractual process: The agency of Oslo Municipality. Director of Roads from the Norwegian Public Roads Political Negotiation Committee - This political com- Administration, Oslo City Council’s public transport mittee is a further development of a local political ini- authority, the Chairman of Akershus County Council, tiative already established in the mid-1980s. The role and the Director of the Norwegian National Rail Ad- of the committee (including Oslo Municipality and the ministration. The steering group’s main responsibility County Council of Akershus) is to address key political is steering and co-ordinating Oslopakke 3, using the issues, consider these in the context of broader prin- principles of project portfolio steering, targets, and re- ciples, and ensure important decisions are acceptable sult steering. Their analysis is used by political bodies to other representatives from their political bodies. The to set priorities in Oslopakke 3. The work also includes Director of Roads from the Norwegian Public Roads preparation of support documents for the Parliament, Administration and the Director of the Norwegian Na- ministerial departments and local and regional gov- tional Rail Administration do not participate in these ernments, to assist them in taking decisions on budgets meetings. and toll money. Political reference Group – In order to secure in ad- The secretariat is responsible for the practical as- vance that key political decisions are sound and suf- pects of steering and implementing of Oslopakke 3. ficient with respect to their political manageability, The secretariat consists of three full-time employees this group consists of group leaders from the political who report directly to the steering group. The secretar- parties represented in county and municipal councils, iat is physically located at the Norwegian Public Roads including each party’s spokesperson on transport. Administration in Oslo, but operates independently as Figure 5. Suggested implementation model of urban environment contracts 16 N O R D R E G I O W O R K I N G PA P E R 2 017 : 3

Figure 6. Organizational structure of urban development agreements

Urban development agreements other large urban areas. A separate agreement will be

In 2015, the Norwegian Government supplemented the developed for each city-region (interview Leite, 2015;

existing urban contractual policy instruments in the Ministry of Local Authorities and Modernisation,

form of the UDA. UDAs are intended to ensure follow- 2015).

up on the land-use dimension of the urban environ- UDAs are intended as a policy tool for the imple-

ment contracts through committed partnerships be- mentation of regional land-use and transport plans.

tween the state, the region and municipalities for These plans are formally implemented under § 8 (Re-

implementation of the action programme of the re- gional plan) or § 9 (Inter-municipality plans) in the

gional (or inter-municipal) land-use and transport Norwegian Planning and Building Act. In § 8-2, it is

plan, with specific focus on land use. As some national prescribed that the regional plan shall be the basis for

authorities have the right to make objections to region- planning and decision-making at county, municipal-

al and local plans, UDAs are also intended to manage ity and state levels. The Planning and Building Act is,

disagreements and contribute to good co-ordination however, not an instrument for following up on the

across the state. regional action plan and practical policy measures,

The use of UDAs is primarily targeted at the four so in this context, the UDA is a tool to formalize and

largest city-regions: Oslo-Akershus, Bergen, Trond- structure co-operative development of an action plan

heim and Stavanger, but could also be implemented in including different levels of the planning system. With

N O R D R E G I O W O R K I N G PA P E R 2 017 : 3 17Figure 7. Overview of UECs and UDAs responsibility for the Norwegian Planning and Build- and the urban reward fund. The ambitious parliamen- ing Act, the Norwegian Ministry of Local Authorities tary climate agreement adopted in 2012 has supported and Modernisation is responsible for the UDA policy the establishment of a more comprehensive framework and its implementation. However, as outlined in Figure of urban contractual arrangements, namely UDAs and 6, the operational planning body for an agreement is UECs: both have been introduced with a view to reduc- the county council. Furthermore, the organizational ing CO2 emissions and reducing the environmental im- structure centres around one co-ordinating group (in- pacts of urban development in general. Moreover, they cluding the contractual partners: county council, mu- can be seen as tools for securing the practical imple- nicipalities, Ministry of Local Authorities and Mod- mentation of existing plans. In addition, looking more ernisation, state authorities, County Governor), and closely at policy arguments, we also see an objective of one supporting co-ordination group including only better co-ordination of planning across different ad- national ministries. ministrative levels (municipality–region–state), as well All four city-regions will start working with their as a push towards integration of traditional planning UDA in beginning of 2016 and the aim is that all sectors, e.g. land use and transport. These contractual should have signed contracts, at latest, in 2017. It will agreements could also be seen as a policy response to be a contract-based co-operation between the parties the current urban dynamics in which functional city- concerned with the aims of ensuring more efficient regions do not correspond with existing administrative planning and implementation of housing construction delineations based on large counties and their munici- in the region. Another three large city-regions will fol- palities. low and then potentially UDAs will be implemented in The introduction of UECs is also a part of a general further cities. process of reforming infrastructural policy to stream- Urban contractual policies in Norway build on the line the financial instruments, such as reward funds, previous tradition of city packages (e.g. Oslopakke) city packages and toll money. The experience of work- 18 N O R D R E G I O W O R K I N G PA P E R 2 017 : 3

ing with the urban reward fund and city packages has and Regional Authorities. The purpose is to collect data

shown that contracts, to a large degree, need to be re- and develop a methodology for transport models to es-

sult oriented, including precise targets and plans for timate walking, bicycling and public transport use in a

operationalization of targets. more precise way, both for the current situation and

after proposed developments in land use and transport.

Challenges and lessons learnt Implementation of urban environment contracts is

Tangible impacts of the urban contractual initiatives challenging. This very heavy political process includes

are hard to identify as so far, very few evaluations and actors at local, regional and national levels that need to

follow-up research projects have been conducted. The agree on the contractual matters, and accomplish this

responsible ministries have initiated a small number of within a relatively short time. A potential challenge

research projects that seek to improve existing regional for the Norwegian Ministry of Local Authorities and

transport models in order to assess the impact of policy Modernisation is that it will have a new operational

relating to the climate agreement. For example, a col- role in the process. It is expected to be more active in

laborative research project has been established be- supporting regional and local bodies in the contractual

tween the Norwegian Ministry of Local Authorities process, especially in the early phases, and in facilitat-

and Modernisation, the Norwegian Public Roads Ad- ing state-level co-ordination between various minis-

ministration, and the Norwegian Association of Local tries and authorities.

N O R D R E G I O W O R K I N G PA P E R 2 017 : 3 194. Sweden: Negotiations and agreements In October 2015, Urban Environment Agreements förhandlingen (2013) (see Figure 8). The NNHI is cen- (UEAs - in Swedish stadsmiljöavtal) were launched in tred around the three major urban regions: Stockholm, Sweden. Since 2014 there is also a National Negotiation Gothenburg and Skåne. on Housing and Infrastructure (NNHI - in Swedish The Swedish Government decided in 2014 that the Sverigeförhandlingen). The NNHI was formed by a NNHI should suggest a financing scheme and a de- governmental directive and follows a tradition in Swe- velopment strategy for high-speed rail lines between den that one or more specific negotiators, or a commit- Stockholm, Gothenburg and Malmö (Swedish Govern- tee, are appointed by the government to lead certain ment, 2014) while promoting public transport, improv- activities and organize negotiations between different ing accessibility and increasing housing construction actors. This has been especially so in greater urban re- in the greater urban areas. The general aim is to ad- gions where large transport packages have been negoti- dress major urban challenges: e.g. effective and fast ated and implemented during recent decades (cf. Nor- completion of high-speed rail lines; a significant in- way). This includes, for example in Stockholm, the crease in the construction of housing; and improved Dennis package (1992) and more recently the Ceder- transport accessibility and capacity in larger cities schiöldsöverenskommelsen (2007) and Stockholms- (Sverigeförhandlingen 2015). Figure 8. Overview of transport packages in Stockholm region 20 N O R D R E G I O W O R K I N G PA P E R 2 017 : 3

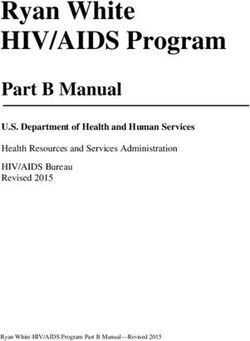

Figure 9. Funded projects in the 1st round of urban environment agreements

Funded projects: 1st round of Urban Environment Agreements

Municipality Measures Examples of counter performance measures 2016–2018

Luleå Investment in new • Detailed plan for the new neighbourhood of Kronandalen

Total cost SEK 16 million charging stations for • Mobility office

Support SEK 8 million electric buses and • Development of regional traffic strategy

renovation of all bus • Expansion of pedestrian and cycle paths and public

stops along the line. transport measures

• Parking strategy and parking rates

• Speeds tailored to vulnerable road users

Östersund Investment in new • Express bicycle paths, 6.5 km

Total cost SEK 6.350 million charging stations for • Lowering the p-standards and introducing flexible

Support SEK 3.175 million electric buses and parking numbers

renovation of all bus • Bus lane in the area Remonthagen

stops along the line. • Housing construction, about 1200 homes

Gävle Improved public • Extensive walking and cycling measures in connection

Total cost SEK 57 million transport with BRT line second

Support SEK 28.5 million measures (Bus Rapid • New housing in the city centre

Transit), and expan- • Adapting speeds in the street environment for pedestri-

sion of Gavlehov with ans and cyclists

sustainable travel. • Parking strategy

Karlstad Bus Rapid Transit • Construction of Sundsta square and Hagatorget

Total cost SEK 140 million ‘Karlstadstråket’. • Housing, workplaces and services

Support SEK 70 million • Walking and cycling measures

• Parking strategies

Linköping Measures in the mu- • Housing construction, first phase, upper Vasastaden

Total cost SEK 72 million nicipality’s bus system, • Further detailed plans for housing

Support SEK 36 million including priority bus • Project smart trips

lanes. • Bike and Ride (MM project)

• Project on traffic and environment in schools

(MM project)

• Commuting cycle route

Helsingborg Helsingborg Express, • Expansion of the cycling paths

Total cost SEK 196 million a high-quality Bus • Speed control throughout the centre of town

Support SEK 98 million Rapid Transit concept. • Review and adjustment of parking fees

• Town plan (AOP) implemented for the whole central area

to identify areas for densification and clarify the role of

public transport as the backbone of urban development

Lund Tram line from Lund • Densification of the knowledge trail

Total cost SEK 746 million Central Station and • Expansion of Brunnshögsområdet

Support SEK 298.4 million the future district • Reconstruction of Lund Central Station at the Clement

Brunnshög. Square stop

• Development of the urban bus route system

• Expansion four defined bike lanes

• Modification of the speed limits in town

• Mobility management during construction of the tramway

Source: Swedish Transport Administration 2015a

Urban environment agreements that the municipalities can apply for co-financing for

The Swedish Government decided (in October 2015) to specific infrastructure projects. In contrast to the

invest SEK two billion in UEAs. The UEAs are not for- NNHI, in the first round of funded projects (an-

mal contract processes, but are rather structured so nounced December 2015) the agreements were mainly

N O R D R E G I O W O R K I N G PA P E R 2 017 : 3 21Figure 10. Organizational structure of urban environment agreements in Sweden targeted at small- and medium-sized towns with the cally, the Swedish Government’s goal is that 250,000 aim of developing local public transport systems new housing units should be built by 2020 and that through, for example, bus-based rapid transit and tram the transport sector’s impact on climate change should lines. diminish (see the Swedish Transport Administration, The UEAs will lead to agreements between the gov- 2015b and Näringsdepartementet 2015 b and c). ernment on the one hand, and municipalities or coun- Urban environment agreements (UEAs) are part of ties on the other, where the latter receives a contribution a broader government programme which includes SEK from the government to develop sustainable transport 3.2 billion to stimulate production of small, environ- solutions, i.e. investments to extend existing local and mentally-friendly rental apartments as well as invest- regional public transport infrastructure as well as in- ments related to maintenance of the railway infrastruc- vestments in infrastructure for new transport solu- ture (Näringsdepartementet 2015c). An underlying tions. Examples include investments for streets, tracks, aim is to foster a more reliable train infrastructure for signalling systems, docks and stops (projects funded in commuters in and around the larger cities: making the first round are listed in Figure 9). Such investments more attractive localities that today are not considered should lead to energy efficiency and increased use of attractive for investments. A further related investment public transport, and contribute to the governmental from the government is a SEK 1 billion contribution to environmental goal of a good built environment while municipalities to support their efforts to sanitize land, also creating new housing. More specifically, the con- for the purpose of building housing (Näringsdeparte- tribution should support public transport measures mentet 2015c). that are innovative, capacity intensive and resource ef- The main arguments for introducing UEAs included ficient. dealing with high housing demand and limitations in The UEAs have also been developed as a response to the capacity of the current public transport infrastruc- rapid urbanization and associated climate change chal- ture, as well as a need for more sustainable urban de- lenges, especially in relation to transport. More specifi- velopment (Näringsdepartementet 2015c). It has been 22 N O R D R E G I O W O R K I N G PA P E R 2 017 : 3

argued that a well-developed public transport infra- Transport Administration and should have a goal to

structure makes areas more attractive for both inves- increase sustainable transportation and/or housing de-

tors and future inhabitants, i.e. new housing can be velopment. At present, there is no requirement that

developed and new residents can live their everyday civil society, including citizens, should be involved in

lives without a car. UEAs aim to promote a general planning and implementation of the proposed meas-

change of transport mode from car to public transport. ures. The application from a municipality or regional

For the Swedish Transport Administration, which is authority should include the following:

responsible for implementing UECs, deciding whether A description of proposed measures, including a

a proposed measure from a municipality or a county time plan, as well as an analysis of how the measures

administration contributes to sustainable development are expected to contribute to the goals of the regula-

is challenging. tion.

A list of the costs that are associated to the above-

Regulations and rules mentioned measures, as well as when the costs will be

The new regulation (Ordinance 2015:579) for the im- presented to the Swedish Transport Administration.

plementation of UEAs came into force in November Information about other contributions that the

2015 (Näringsdepartementet, 2015a). As mentioned, applicant has applied for or received to perform the

the government and a municipality or regional author- above-mentioned measures.

ity do not sign a contract. Municipalities or regional A description of the counter measures that the mu-

authorities apply for a contribution from the Swedish nicipality or county undertakes to implement, and how

Transport Administration to perform a specific meas- such measures fit with the municipality’s or county’s

ure. After making a qualified evaluation, the Swedish overarching work towards sustainable development.

Transport Administration may decide to contribute up Additional information that the Swedish Trans-

to 50% of the costs. If a municipality or a regional au- port Administration needs to assess the application

thority receives a contribution, a counter measure is (Näringsdepartementet, 2015a).

required, i.e. the recipient of the contribution makes an The first projects were awarded funding of SEK 540

investment in an additional measure that contributes million in December 2015. In the first round, the Swed-

to sustainable urban development. This counter meas- ish Transport Administration received 34 applications

ure does not receive a contribution from the Swedish and seven were approved (as listed in Figure 9).

N O R D R E G I O W O R K I N G PA P E R 2 017 : 3 23You can also read