The European Union as a Protagonist to the United States on Climate Change

←

→

Page content transcription

If your browser does not render page correctly, please read the page content below

International Studies Perspectives (2006) 7, 1–22.

POLICY

The European Union as a Protagonist to the

United States on Climate Change

JOHN VOGLER

Keele University

CHARLOTTE BRETHERTON

Liverpool John Moores University

The European Union (EU) has established itself as the moving force in

the development of the international climate-change regime. By pro-

ceeding with the ratification of the Kyoto Protocol and building its own

carbon emissions trading system, it has directly confronted the United

States. Contemporary commentaries on the politics of climate change

center upon the conflict between the EU and the U.S., but the precise

nature of the EU as a protagonist remains elusive. It is neither a state

nor an orthodox international organization but it can be regarded as an

actor. This article investigates what it means for the EU to be an actor

and develops a conceptualization based upon presence, opportunity,

and capability. This is applied to the analysis of how the Union became

an actor in climate-change politics, and its special characteristics,

strengths, and vulnerabilities. The final part of the article then pro-

ceeds to consider the differences between the European actor and the

United States over the development of the climate-change regime.

Keywords: EU–U.S. relations, climate change, EU as an international

actor

When the Kyoto Protocol to the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change

(UNFCCC) finally entered into force on February 16, 2005, it provided an occasion

to celebrate the resolve and leadership of the European Union (EU). Ratification

had finally been achieved in the teeth of U.S. opposition and climate-change policy

had become part of a wider transatlantic discourse on the role of the Union, in

which it often came to be regarded as a necessary counterbalance to the U.S.

Whatever the failings of the Common Foreign and Security Policy (CFSP) and

whatever the divisions between ‘‘old’’ and ‘‘new’’ Europe over Iraq, here at least

was a vindication of the aspirations of the Union to become an actor in world

politics. According to the President of its Commission, the EU had ‘‘worked hard to

be worth listening to. We are maturing, speaking with a unified voice more often

and on a broader range of issues’’ (Barroso 2005).

Yet, the Union, enlarged to 25 state members, was neither a state nor an

orthodox international organization. The EU (as opposed to one of its

r 2006 International Studies Association.

Published by Blackwell Publishing, 350 Main Street, Malden, MA 02148, USA, and 9600 Garsington Road, Oxford OX4 2DQ, UK2 European Union on Climate Change

componentsFthe European Community) does not enjoy international legal per-

sonality, although it was widely recognized as an important player in climate-change

politics.1 During climate negotiations, it was routinely treated as an actor capable of

autonomy and volition, but at the same time the differences between its Member

States were manifest and there were suspicions that it could not wield state-like

authority in implementing its international commitments. Nonetheless, it achieved

its specific aim of bringing the Kyoto Protocol to life and creating, in 2005, the

world’s first international emissions trading system (ETS) to fulfill its own Kyoto

obligations. Beyond this, it was expected to lead attempts to develop new global

undertakings, perhaps even to become a ‘‘climate hegemon’’ (Legge and Egenhofer

2001) and not only to challenge but also to persuade the United States to participate.

The Union is, as will be argued below, both a problematic leader and a most

unlikely hegemon. Its current activities and aspirations set a puzzle in terms of

‘‘actorness.’’ How should one conceptualize an entity for which there are no pre-

cedents, and for which the template of statehood is evidently inappropriate? This

remains a real concern for those who have to deal with it, especially in environ-

mental negotiations. A frequent observation among members of the diplomatic

community in Brussels is not only that the Union is entirely unlike a state, but that

they also have to spend much of their time explaining its idiosyncrasies to their

governments back home. We attempt to investigate this question in the specific area

of climate-change politics by considering how the presence of the EU and the

opportunities open to it led to the growth of actor capabilities and ultimately a key

role in the climate-change regime.

The investigation of the characteristics of the EU as an actor may reflect two

meanings of a ‘‘protagonist’’: as ‘‘the chief person in a drama’’ and as ‘‘an advocate

or champion of a cause.’’ This provides a necessary basis for the second part of this

article, which takes its cue from another definition of a protagonist as ‘‘one of the

chief contenders in a contest’’ in which the other is clearly the United States. During

the 1970s and the 1980s the U.S. was a powerful and progressive leader in en-

vironmental policy, exerting a decisive influence over the development of inter-

national environmental regimes. This was exemplified in the negotiation of the

1987 Montreal Protocol to protect the stratospheric ozone layer (Benedick 1991).

By contrast, the European Community appeared divided, insecure as to the re-

spective powers of the Commission and the Member States, and overly influenced

by the interests of British and French chemical industries. In the ensuing years, this

position has been radically changed. It is now the EU that self-consciously claims

the mantle of environmental leadership and the United States that is cast in the role

of ‘‘veto state,’’ obstructing international environmental policy in the protection of

habitats, in biosafety, and, above all, in its denunciation of the Kyoto Protocol.

It was during the 1980s that scientific evidence of increasing concentrations of

greenhouse gases (GHGs), and notably carbon dioxide, in the atmosphere gave rise

to concern that human activities might be leading to an increase in global mean

temperatures and alterations in the climate. In response, the UNFCCC was signed

in 1992. The Convention only imposed reporting obligations on its signatories, but

it did include the principle of ‘‘common but differentiated responsibilities’’ under

which developed or Annex I countries were charged with making the initial moves

to curb emissions of GHGs. Subsequent Conferences of the Parties (CoPs) discussed

how the regime might be developed, leading up to the signature of a control

1

The European Union was created in 1993 under the Treaty of Maastricht. It comprised the existing European

Community (Pillar I) along with two new intergovernmental pillars: the Common Foreign and Security Policy (Pillar

II) and Justice and Home Affairs (Pillar III). It has become commonplace to speak of the European Union even if, as

in trade policy, the legally correct reference is to the European Community. This practice will be followed except,

where for reasons of historical accuracy or where the competencies of the Community are at issue, it is necessary to

make reference to the EC.JOHN VOGLER AND CHARLOTTE BRETHERTON 3

Protocol at Kyoto in 1997. The terms of this agreement are well known and involve

commitments by Annex I countries to reduce their GHG emissions by an average of

5.2% from a 1990 baseline by 2008–12. To assist them in this, the Protocol includes

three ‘‘flexibility mechanisms’’; emissions trading, joint implementation (JI), and

the clean development mechanism (CDM).

After the signature of Kyoto, negotiators faced the laborious and complex task

(outlined at the Buenos Aires CoP of 1998) of fleshing out the details and imple-

mentation of the heads of agreement outlined in 1997. The process was scheduled

to end at the November 2000 Hague CoP 6, in the dying days of the Clinton

administration. There was still some expectation in EU circles that the United States

would come to be in a position where it would ratify the Protocol. The incoming

Bush administration declared the Protocol ‘‘fatally flawed’’ and denounced the U.S.

signature. One well-known American academic commentator (Victor 2001) went so

far as to publish a book proclaiming the death of Kyoto. This was certainly pre-

mature. The immediate survival of the Protocol and the subsequent conclusion of

its detailed provisions at Bonn (CoP 6 bis) and Marrakech (CoP 7) were, without

question, direct consequences of the resolve of the EU to proceed without the U.S.

The decision, confirmed by the Gothenburg European Council in June 2001, to

move ahead with the Protocol in the face of outright U.S. rejection, may well come

to be seen as a crossing of the Rubicon in international environmental politics. Thus,

EU Environment Commissioner, Margot Wallstrom, claimed at the timeF‘‘I think

something has changed today in the balance of power between the U.S. and the

EU’’ (Earth Negotiations Bulletin 2001:1).

The entry into force of the Protocol, upon which so much European energy

had been expended, required ratification by 55% of the signatories, who must

include developed (Annex I) states responsible for 55% of emissions. The latter

hurdle could only be surmounted, in the absence of the U.S., by ensuring rati-

fication by Japan, Canada, and, most critically, Russia, responsible for around 17%

of GHG emissions. Achieving this required a real demonstration of EU resolve as

an actor.

Conceptualizing Actorness

Traditional and Realist approaches to IR have focused almost exclusively upon the

role of states as actors in ‘‘high politics.’’ The ability to use force was the deter-

minant of great-power status. As a consequence, Realist treatments have neglected

the potential of a largely civilian EU to be a significant political actor in its own right,

concentrating instead upon its utility as an instrument of its most powerful Member

States. In international law, too, states remain pre-eminent although since 1946

there has been some modification in terms of the acceptance of the legal personality

of organizations. At the UN, membership is confined to states, the EU being grant-

ed only observer status. This is also the case for most international organizations,

with the very notable exception of the WTO.

However, once we accept the significance of climate politics as a key arena of

contemporary international relations, perhaps even achieving the status of high

politics, we are forced to consider the EU itself as an actor. That this acceptance is

now commonplace can be verified by even a cursory reading of press reportage.

The EU is urged to act, is blamed for its immobility, and is frequently told to resist

U.S. hegemony. Such a construction is more than a convenient shorthand to avoid

wearisome reference to the 25 Member States and the European Community

‘‘acting within its competencies.’’ It demonstrates an understanding, however im-

perfect, that the Union is an actor in its own right. This has long been the case in the

specialized literature on the development of the climate-change regime (Vellinga

and Grubb 1993; Mintzer and Leonard 1994; Nilsson and Pitt 1994; O’Riordan

and Jäger 1996; Paterson 1996). It also reflects the legal situation, where, as in a4 European Union on Climate Change

number of other areas, the European Community (but not the Union) is a signatory

alongside the Member States of both the Framework Convention on Climate

Change and the Kyoto Protocol. In environmental conventions, including the UN-

FCCC, it appears in the special guise of a Regional Economic Integration Organ-

ization (REIO)Fa category within which the Community is the only extant

example.2

The status and growing international role of the EU is one of several factors that

led IR scholars to broaden the scope of their analysis to include a range of non-state

actors. As long ago as 1970, the European Community was being discussed along-

side a range of other ‘‘new international actors’’ (Cosgrove and Twitchett 1970). By

1973, Keohane and Nye were referring to a ‘‘mixed actor system’’ but such pluralist

analyses tended to categorize the Union alongside other intergovernmental orga-

nizations not enjoying its special status and characteristics. Furthermore, those

scholars who have dealt specifically with the EU in international relations have often

restricted their analysis to high politics as represented by the CFSP and the nascent

European Security and Defence policy (ESDP). There is now an extensive body of

scholarly work in this area that demonstrates the increasing institutionalization of

foreign policy cooperation between EU members and the not inconsiderable im-

pact of the Union in areas such as the promotion of human rights (Ginsberg 2001;

White 2001; Smith 2003, 2004). It is our contention that an emphasis on foreign

policy alone fails to capture the general significance of the EU in the world system

and its particular importance in climate-change politics. The approach adopted

here conceives of the EU neither as a partly formed state nor as an overdeveloped

intergovernmental organization. It derives from a more extensive study (Brether-

ton and Vogler 1999, 2006) that treats the EU as an actor sui generis and that, in

examining the totality of external policy areas, attempts to ascertain the Union’s

overall significance as a global actor.

Abandoning the template of the state requires that we substitute some other

behavioral measure of what it means to be an international actor. Over the years,

various attempts to achieve this have emphasized the characteristics of autonomy

and volition (Hopkins and Mansbach 1973; Sjöstedt 1977; Merle 1987). An actor

must be distinct from its component partsFa recognizable entity in its own right.

In the case of the EU, this may direct attention to the determinants of autonomous

action located in the competencies of the European Community, the independence

of the Commission, and in the extent of qualified majority voting in the Council,

which removes the sovereign right of individual Member States to exercise a veto.

Actorness also implies volition. It is a measure of a unit’s capacity to ‘‘behave actively

and deliberately in relation to other actors in the international system’’ (Sjöstedt

1977:16). Over the past decade, since inclusion in the Treaty on European Union of

the objective ‘‘to assert its identity on the international scene’’ (TEU Article 2), there

has been a drive to enhance the Union’s status as an actor and develop its distinctive

roles and identityFnot least as a benign power committed to upholding human

rights, eradicating poverty, and protecting the environment (Manners 2002).

This broad and challenging agenda clearly demanded that the EU progress be-

yond its practice, in several external policy areas, of simply reacting to external

events and demands. Thus, the focus, here, is upon the extent to which the EU has

developed the capacity to move beyond rhetorical statements and reactive policies

2

The status of Regional Economic Integration Organization was established to allow European Community

participation, alongside the Member States, in the 1979 Long Range Transboundary Air Pollution Convention. It

provides the format under which the EC is involved and may vote (but only in the absence of the Member States) in

most of the main global environmental treaties, including the UNFCCC. The relevant provisions are Arts. 6, 4(2b),

18 and 22 of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, UN Doc.A/AC.237/18 (Part II) Add.1,

15 May 1992. There have been various unsuccessful attempts to endow the EU as a whole with legal personality,

culminating in agreement that this would occur under the Constitutional Treaty Art.I-7.JOHN VOGLER AND CHARLOTTE BRETHERTON 5

in order to make conscious choices and decisionsFand hence to engage in

purposive externally oriented action. Becoming an actor, in our view, involves more

than establishing a degree of autonomy in relation to the Member States and for-

mulating a set of common purposes. Actorness is also critically dependent upon the

expectations and constructions of other international actors and its development

may be regarded as a dialectical process, involving three facets and the intercon-

nection between themFpresence, opportunity, and capability.

Presence conceptualizes the ability of the EU, by virtue of its existence, to exert

influence beyond its borders. It combines understandings about the fundamental

nature, or identity of the EU with the (sometimes unintended) consequences of

the Union’s priorities and policies. It provides the link between the internal de-

velopment of the EU and third-party perceptions and expectations of the EU’s

role in world politics and demands that it shall act.

Opportunity refers to the external environment of ideas and events that enable or

constrain purposive action. It signifies the structural context of action.

Capability refers to the capacity to formulate and implement external policy, both

in developing a proactive policy agenda and in order to respond effectively to

external expectations, demands, and opportunities.

Presence and the Construction of Actorness

Broadly following Allen and Smith (1990), presence refers to the ability to exert

influence to shape the perceptions and expectations of others. Presence does not

denote purposive external action; rather, it is a consequence of the external impact

of internal policies and processes and, more broadly, of perceptions of the EU’s

significance. Thus, presence is a function of being rather than doing; it is an at-

tribute that can denote structural power, including the power of veto. Inevitably,

presence is enhanced by the success of the European projectFreflected in the

implementation of internal measures such as the creation of the Single Market or

the accession of new members. Similarly, it must be supposed that presence will be

diminished by perceptions of failureFnot least, in the present context, should the

EU ultimately fail to reach its own Kyoto emissions targets. Highly public disunity

inevitably also impinges on presenceFwhether over Iraq policy or the fate of the

Constitutional Treaty.

The EU’s espousal of the Kyoto Protocol has now given climate policy very much

greater salience, such that success or failure will most definitely affect the Union’s

external presence. This has rarely been the case with other aspects of environ-

mental policy:

Climate change is not only an extremely grave international problem but an issue

which had been acquiring a symbolic profile in the protest movement against the

destructive effects of globalization. It may therefore be affirmed that this agree-

ment on the Kyoto Protocol was of major importance in terms of the regulation of

globalization and international governance (European Parliament 2002:7–8).

The expectations surrounding EU presence in the climate-change issue area are

now huge and perhaps dangerously so.

Presence has undoubtedly played an important role in the construction of ac-

torness. The relationship between them can be relatively direct, in that active re-

sponses from third parties generated by internal policy initiatives tend to produce,

in turn, demands for action by the EU. The trade-diversionary effects of setting up

the Common Market or the malign external implications of CAP subsidies provide

obvious examples of this process. In respect of climate change, the sheer scale of the

Single Market, by some measures the largest economy in the world, ensures that

the Union will be the closest rival to the U.S. in terms of tonnage of greenhouse gas

emissions (if not in per capita emissions). Thus, in 2002, the U.S. emitted around6 European Union on Climate Change

6.9 million metric tons of CO2 equivalent, the EU 25, 4.8; Russia 1.9; and Japan 1.3.3

This means that, whether it is an effective actor or not, the Union will be held

responsible, alongside the United States, and to a much lesser extent the other

developed countries, for the fate of the earth’s climate. This understanding provided

the basis for internal action by the Union, despite the absence of Community com-

petence for matters such as energy policy and taxation. Internal actions have, in turn,

established Union presence that both underpins the EU’s participation in the cli-

mate-change regime and, in the case of the ETS, is highly significant in its own right.

Early attempts at EU action were not auspicious (Skjaerseth 1994). A carbon

taxation initiative of the early 1990s, seen as a response to the development of the

UNFCCC, failed. In protest, the then Environment Commissioner, Ripa de Meana,

refused to attend the 1992 Rio Earth Summit at which the Convention was signed.

There are a number of specific problems faced by the Union in this area additional

to those, such as the assumed burden to economic competitiveness imposed by

energy taxation, that confront all developed economies. In particular, alongside the

very different patterns of development and energy use among 25 Member States,

there is the problem of competence. Competence is the EU term for ‘‘powers.’’

There are relatively few areas, such as competition policy, the setting of external

tariffs, or the preservation of marine biological resources, where exclusive Com-

munity competence exists. Here, European decision-making is at its most powerful

and has been demonstrated over the years by the central role played by the Trade

Commissioner, alongside the U.S. Trade Representative at the World Trade Org.

(WTO). The Commission initiates and the Council of Ministers approve, usually by

qualified majority vote, and Member States may not legislate in these areas.

Energy, environmental, and transport policy are areas of ‘‘shared competence’’

where substantial legislative rights remain with the Member States, while some

areas, such as atmospheric quality, have been made a Community competence.

Taxation remains a jealously guarded competence of each Member State. A mo-

ment’s consideration of the many dimensions of climate policy will indicate the

problems faced by the Union in establishing an effective and collective approach.

While there has been a real political commitment to make policy for the Union as a

whole, there are wide divergences between Member State approaches. Nonetheless,

the results achieved since the signature of the Kyoto Protocol have been relatively

encouraging.

A broad set of measures are proposed by the Commission under the European

Climate Change Programme (ECCP). In addition to measures in direct support of

Kyoto Protocol implementation, they include a range of energy efficiency and de-

mand management proposals and a public awareness campaign. Also covered are

the methane emissions from landfill waste, and the ways in which reforms to the

Common Agricultural policy could reduce emissions and augment sinks for carbon

dioxide. Most controversial are proposals for transport involving a ‘‘modal shift’’

toward rail, infrastructure charging, and the promotion of biofuels (Commission

2001a:23).

The centerpiece of the Union’s approach is its own ETS. Covering power gen-

erators above 20 MW and other large installations, the system has been operational

since January 1, 2005, although an embryonic market in carbon futures had al-

ready started up. ETS covers around 12,000 enterprises in all 25 Member States. As

a ‘‘cap and trade’’ system, it relies upon national allocation of carbon allowances to

3

The 2002 figures for total aggregate anthropogenic emissions, excluding removals through land-use change

and forestry (which, by including sinks, would reduce the totals) are as follows, expressed in metric tonnes of C02

equivalent: U.S.: 6,934,562 (a 13% increase from the 1990 baseline), EU15: 4,123,618 (3% decrease), Russia:

1,876,000 (last available data but revealing a 38% decrease), and Japan: 1,330,793 (a 12% increase) (UNFCCC

2004:14). The first figures for the EU25 calculated by the Commission for 2002 are: 4,852,000, with a 9% decrease

from the 1990 baseline (Commission 2004:4–5). We owe the existence of such comparable data to the national

inventory reporting requirements imposed upon parties by the 1992 Framework Convention on Climate Change.JOHN VOGLER AND CHARLOTTE BRETHERTON 7

plants that are then tradable. These will be progressively reduced in line with Kyoto

commitments. Many commentators have regretted the generosity of the national

allocations in the first phase and the absence of a central EU ‘‘cap’’ (Bowyer et al.

2005). Nonetheless, the system is now operating and firms have the choice of,

either, cutting their own emissions and saving some of their allocated allowances,

which have a market value, or, buying allowances in order to maintain existing

levels of emission (Commission 2005a:17). The effectiveness of this artificially cre-

ated market relies upon rigorous enforcement of compliance by national govern-

ments in issuing permits to individual firms, verifying their monitoring procedures,

and in running national transaction registries, the whole procedure being overseen

by the Commission in Brussels. It also requires an equilibrium between supply and

demand for carbon allowances that may be difficult to engineer. The most difficult

part of the exercise will be the second phase of national allocations, from 2008,

when the Commission will need to ensure that, unlike in the initial phase, Member

States really bear down upon permitted emissions.

While the ETS was created as a means whereby the Union would fulfill its own

Kyoto commitments, it was also designed to be an open system, compatible with the

international emissions tradingFone of the three flexible mechanisms of the Pro-

tocol (Commission 2001b). The ETS incorporates the use of the other two. JI where

credits are earned by assisting other developed countries in reducing their emis-

sions and the CDM, where the same logic of spending money where it best pro-

motes energy efficiency, also applies with respect to developing countries. In both JI

and CDM, those who are prepared to invest in energy-conservation measures

overseas can earn credits against their own emissions within the European system.

The ETS opens the door to numerous presence effects involving the participation

of applicant countries, neighbors like Norway and potential worldwide involve-

ment. Emissions trading schemes have already begun in various parts of the world

and it is by the elaboration of its own dominant scheme that, according to Legge

and Egenhofer (2001:4), the EU could become the international standard setter

and acquire a hegemonic role, finding ‘‘itself in control of the most important

international regulatory effort to limit GHGs.’’ This kind of expansive politics has

already occurred, for in recent years efforts have been made to ensure that EU

positions on climate change have been ‘‘elaborated jointly with candidate countries’’

(Council 1998:2).

The world’s first international carbon ETS is already having demonstration ef-

fects that may reinforce expectations of a proactive Union role. Despite the refusal

of the Bush administration to institute carbon trading under Kyoto, there is grow-

ing interest at a sub-federal level among coalitions of U.S. cities and in the private

sector where prudent decision makers need to plan for a carbon-limited future.

Over the longer term, the presence effects of the ETS within the United States may

be as significant as anything that is achieved by the EU as an actor in negotiation

with the U.S. government.4 There is, in fact, no inevitable link between the external

presence of internal policies and the development of actor capability. This may be

demonstrated by the successful creation of the euro, which greatly extended the

Union’s monetary presence but has not led to identifiable EU actorness at the IMF

and elsewhere. In the case of climate change, however, the establishment of the

ETS is likely to augment the actor capability that already exists. Conversion of all

such aspects of presence into actorness, however, requires opportunity.

4

There is also the reintroduced McCain–Lieberman Climate Stewardship and Innovation Bill in the U.S. Con-

gress, which, contrary to the intent of the Bush administration, aims to set up carbon trading. The controversial part

of this scheme is the provision for the auction of allowances to fund innovation in energyFincluding nuclear

technology.8 European Union on Climate Change

Opportunity

During the early years of the development of the original European Community,

the external environment was dominated, politically, by the Cold War bipolar

structure and, economically, by U.S. preponderance within the Bretton Woods

system. Freed from direct concern with military security or monetary stability, the

process of European integration flourished. Beyond the requirements of the Com-

mon Commercial Policy, there was little expectation of, or opportunity for, pro-

active external action.

By the mid-1970s, however, the international system was increasingly seen in

terms of (primarily economic) interdependence. This was associated with Cold War

détente and a decline in U.S. economic dominance, reflected in the demise of fixed

parities pegged to the dollar. It was manifested in perceptions of vulnerabilityFto

economic instability but also to transboundary (and by the 1980s) global environ-

mental problems. In circumstances where the ability of individual states to regulate

increasingly global processes was in question, the EC appeared well placed to act

externally on behalf of its members. During this period, however, increased op-

portunity saw only tentative steps toward actorness.

One advance occurred at the end of the decade with European Community

involvement, in its own right, as a participant in the negotiation process establishing

the 1979 Long Range Transboundary Air Pollution Convention (LRTAP). This UN

Economic Commission for Europe-sponsored negotiation reflected the spirit of

détente and the EC was able to take advantage of a relaxation in the usual Soviet

objection to its participation. Apparently, the unfulfilled Soviet objective was that

similar treatment would be afforded to Comecon. The LRTAP negotiations also

devised the REIO formula to cover EC participation alongside the Member States.

Although this marked the seizure of an external opportunity, participation was

grounded in internal developments. The 1970s had witnessed the rapid acquisition

of internal Community competencies as environmental policy developed in areas

such as air pollution, waste management, water quality, and acidification. An im-

portant judgment of the European Court of Justice had already established that,

where Community competence existed, competence for external negotiations au-

tomatically followed.5 This meant that the European Commission could assert its

right to negotiate aspects of an international environmental agreement alongside

the Member States.

The end of the Cold War had enormous overall significance for the development

of the EU’s external roles. Routine objections from the Soviet Union to EC par-

ticipation came to an end and new relationships were forged with countries in Asia

and Latin America, so that the potential influence of the Union became truly global.

The EU has also benefited in terms of opportunity, from the way in which some

very high-profile environmental negotiations on stratospheric ozone, climate, and

the Rio process coincided with the end of the Cold War. During the negotiations for

the 1987 Montreal Protocol, the chief U.S. negotiator could make out a credible

case for American leadership and that the whole agreement had been delayed by

the inability of the EC to resolve the internal difficulties associated with the passage

of the Single European Act (Benedick 1991). In the 1960s and 1970s, U.S. state and

federal administrations had virtually invented modern environmental policy, and

were acknowledged leaders in the use of legislation to conserve species and habitats

along with pioneering work on market-based instruments. In 1995, the United

States initiated the world’s first ETS for sulfur dioxide, and continues to extend this

method of environmental protection in areas other than carbon trading. The

5

In the ERTA judgment, ECJ 22/70 (1971). This provides the legal basis for Community involvement in external

environmental and other policy areas. Environmental policy itself first received treaty recognition in the 1987 Single

European Act; the relevant clauses are now to be found at Arts 174 and 175 of the Treaty Establishing the European

Community (TEC) while the arrangements for external representation are contained in Art.300.JOHN VOGLER AND CHARLOTTE BRETHERTON 9

influence of all this intellectual capital is still evident in, for example, the Com-

mission’s acknowledgment that exchange of information with American experts

had played a role in the development of the ETS (Commission of the European

Communities 2005a:17). One of the paradoxes of the Union’s espousal of the Kyoto

flexibility mechanisms is that what is often claimed as EU leadership is also an

instance of ‘‘policy transfer’’ from the United States (Damro and Mendez 2003).

Whatever the continuing influence of U.S. policy innovations, during the past

decade, the idea of U.S. environmental leadership has, to put it politely, ceased to

be credible. In the words of one Commission official, referring to a range of en-

vironmental negotiations in the mid-1990s, ‘‘the U.S. has raised sitting on its hands

to the status of an art form’’ (Interview then DGXI Brussels 6 June 1996). U.S.

obstructionism and disengagement across a range of negotiations left the EU with a

leadership opportunity that it was uniquely qualified to seize:

The U.S. is a strong political actor whereas the EU is a slow moving but weighty

ship. The Community position has more weight in the long term. The U.S. often

cannot define a credible negotiating platform - they cannot think of all the ram-

ifications, on North-South issues for example, as the Community can. In climate,

forests and biodiversity the EU is the only leader while the U.S. is absent, blocking

or destructive. (ibid.)

Not only was the U.S. no longer a leader, but it was involved in a progressive

distancing from active involvement in climate-change management, culminating in

the March 2001 formal denunciation of the Kyoto Protocol. U.S. withdrawal from

the negotiations prompted the observation by the president of the sixth UNFCCC

Conference of the Parties (CoP 6), Jan Pronk, that the EU ‘‘had become the only

game in town’’ (Earth Negotiations Bulletin 2001:13).

It is possible, however, that the period between the end of the Cold War and the

attacks of 9/11 2001 was singularly propitious for EU actorness. Despite demands

that the EU should assert or increase its influence on the world stage, and in

particular should strive for an identity and roles that sharply distinguish its stance

from that of the U.S.A., the contemporary period is undoubtedly dominated by the

U.S.-led ‘‘war on terror.’’ It has been characterized by a significant disregard for

international law and the authority of the United Nations, by sustained efforts by

the U.S. government to undermine the newly established International Criminal

Court, and by contravention of civil and human rights norms. The denunciation of

the Kyoto Protocol is seen, rightly or wrongly, as part of a pattern of ‘‘lawlessness’’

(Sands 2005). To the extent that ‘‘security threats’’ dominate the agenda of inter-

national politics, the EU may encounter a diminution in opportunity to develop a

distinctive postureFand, more specifically, to maintain a leadership role in climate-

change diplomacy. Nevertheless, while the Iraq crisis demonstrated the limitations

of a common foreign policy, U.S. rejection of the Kyoto Protocol has undoubtedly

provided the EU with a unique opportunity to capitalize on its economic and en-

vironmental presence and to assume a leadership role in the climate-change re-

gime. While EU representatives have enthusiastically claimed this role, it remains to

consider the extent to which the EU possesses the capacity to achieve and sustain it.

Actor Capability

In order to build upon its formidable presence and exploit available opportunities,

the Union must possess a number of the prerequisites of actor capability. We would

summarize them as follows:

shared commitment to a set of overarching values and principles;

the ability to identify priorities and to formulate coherent and consistent pol-

icies;10 European Union on Climate Change

the ability to negotiate effectively with third parties and to implement agree-

ments;

capability in the deployment of diplomatic, economic, and other instruments

in support of common policies; and

public and parliamentary support to legitimize action.

The first of these pre-requisites is relatively unproblematic. The Treaties set out

broad values and principles to which the EU and its Member States are committed.

These include a commitment to integrate sustainability into all policy areas (TEU

Art 2). In the specific case of climate change, the European Council and the Par-

liament have been robust in their view of the urgency of the situation and in their

determination to support the Kyoto Protocol. The European Council, which brings

together the 25 heads of government, has confirmed its view that ‘‘global mean

surface temperature increase should not exceed 21C above pre-industrial levels’’

and that this will require ‘‘significantly enhanced aggregate (GHG) reduction ef-

forts by all economically more advanced countries.’’ More specifically, they envisage

‘‘reduction pathways for the group of developed countries in the order of 15–30%

by 2020’’ relative to Kyoto’s 1990 baseline (Presidency ConclusionsFBrussels,

March 22 and 23, 2005: IV, 46).

Unproblematic, too, is the ability to identify priorities and formulate policyFat

least in principleFas demonstrated by the emissions reduction targets enunciated

before Kyoto and afterwards in the determination to achieve entry into force of the

Protocol. In practice, however, the extent to which objectives are realized varies

considerably between policy sectors. Inevitably, as in any complex policy system,

divergent interests generate friction. EU policy making is, however, further im-

peded by difficulties that flow from its unique character. These are commonly

identified as consistency and coherence.

Consistency and Coherence

Consistency denotes the extent to which the policies of Member States are con-

sistent with each other and complementary to those of the EU. Hence, it is a

measure both of Member State commitment to common policies and the overall

external impact of the EU and its Member States. In areas such as trade in goods

where there is exclusive community competence and common policies are en-

trenched, consistency is not a significant issue. Here the Community is well estab-

lished in its various roles as a trade actor, with the Commission representing

the Member States in bilateral negotiations with third parties and in multilateral

negotiations in the context of the WTO.

In many areas of EU external policy (e.g., development assistance), consistency

can cause difficulty. In relation to climate change three issues deserve consider-

ation. First, despite the Community competence for ‘‘preserving, protecting, and

improving the quality of the environment’’ (TEC Art.174), which provides the legal

basis for EC ratification of Kyoto, Member States retain overall responsibility for

highly relevant but politically sensitive policy areas such as energy, transport, and

taxationFa situation that is unlikely to change in the foreseeable future. As we have

seen, across all areas of environmental policy, a situation of ‘‘shared competence’’

has remained, with the degree of competence enjoyed by Community and Member

States varying by issue and by negotiation (Vogler 1999). A very high level of

Community competence exists in the Basel Convention negotiations, for example,

because they involve waste disposal and trade. Climate change, by contrast, has

been an area in which Community competencies are restricted and Member State

competencies remain extensive.

The very different energy interests and levels of economic development of

Member States have been, for the moment, reconciled by the burden-sharingJOHN VOGLER AND CHARLOTTE BRETHERTON 11

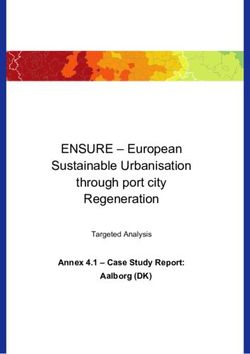

THE EU BURDEN SHARING AGREEMENT JUNE 1998

Austria –13% Italy –6.50%

Belgium – 7.50% Luxembourg –28%

Denmark –21% Netherlands –6%

Finland 0% Portugal 27%

France 0% Spain 15%

Germany –21% Sweden 4%

Greece 25% United Kingdom – 12.50%

Ireland 13%

European Union –8%

FIG. 1.

agreement (or EU ‘‘bubble’’). This agreement, engineered by the Dutch Presidency

in March 1997, provided the basis upon which the EU was able to enter the Kyoto

negotiations with a credible common emissions reduction target. Britain and Ger-

many were able to offer large commitments on reductions from 1990 levels on the

basis, respectively, of re-structuring energy supply from coal to natural gas and

closing down energy-inefficient former East German installations. Others like

France, with a heavy reliance on nuclear power generation, were allowed to main-

tain the status quo while less-developed EU economies were actually granted in-

creased emissions. The revised agreement, which came into force after Kyoto and

provides the national objectives to be reached through emissions trading and other

measures, is described in Figure 1. Nevertheless, the scope for inconsistency, as the

Member States attempt to proceed with the Climate Change Programme, has al-

ready been revealed, with the Commission attempting to ‘‘name and shame’’ Spain,

Austria, Belgium, and Ireland for backsliding on Kyoto targets (Carstens 2003).

The situation is further complicated by the 2004 enlargement, which brings into the

Union parties the UNFCCC who enjoy the special status of ‘‘economies in tran-

sition to a market economy.’’

The second area where consistency problems impinge upon actorness relates to

the differing external orientations of Member States. This has been perhaps most

evident in the context of the U.K.’s relationship with the U.S.A. It has been com-

mon practice for U.K. officials and politicians to apologize privately to their U.S.

counterparts for a tough common position adopted by the EU. Such inconsistency

has been very evident in the CFSP where there is sometimes a damaging division

between ‘‘Atlanticist’’ and other Member States. It is much less evident in trade or

agriculture where greater Community discipline is enforced. In climate-change

negotiations, there has clearly been some scope for ‘‘indiscipline,’’ where members

of EU delegations have attempted to cut informal deals with the U.S. in contra-

vention of established internal procedures.6

Both types of consistency problem have been used by opponents to undermine

the EU’s position. There is also a third problem, which has a more formal and legal

character but has been used in the same way, particularly with respect to the EU

‘‘bubble.’’ This rests upon the incompleteness of the Union as an actor and queries

as to whether it has the capacity to bind its Member States to an agreement. It was a

persistent theme during the preparatory meetings in advance of Kyoto when EU

delegates were asked how they could guarantee an agreement that depended on an

6

A prominent example of this practice led to a very public row between U.K. minister John Prescott and the

French Presidency when the former attempted to salvage the 2000 Hague CoP 6 negotiations through personal,

high-level contacts with the U.S. delegation.12 European Union on Climate Change

entity that was not a sovereign state with all that this might entail in terms of

international legal obligation.7 We encounter here another aspect of actor capability

in terms of the need to be able to demonstrate compliance with international

agreements. U.S. officials sometimes argue that the nature of their legal system

would make the ratification of Kyoto somehow more binding for the U.S. than for

the EU. ‘‘If we were to ratify it would become law and we could not adjust and we

would be bound’’ (Interview, U.S. Mission Brussels, May, 2005). While it is not

unknown for states to renege upon their obligations, the EU has usually been

punctilious in its law making and in the monitoring of national implementation of

collective agreements. The legal text on the ratification of the Kyoto Protocol in-

cludes the burden-sharing agreement and notification that the EC had already

adopted instruments that were binding upon the Member States in respect of the

implementation of the Protocol. All the Member States and the Community si-

multaneously ratified (Commission 2001). The Commission ultimately has recourse

to the European Court of Justice to enforce compliance by errant Member States.

Problems of coherence are of a different order, but nonetheless significant. They

stem from the internal policy processes of the Union. In the multi-sectoral area of

climate change, policy responsibilities are divided between several DGs of the

Commission. This is graphically illustrated by the range of actions envisaged under

the ECCP. Within the Commission, despite a range of mechanisms intended to

facilitate coordination of external policy, there has been a tendency for the pref-

erences of the most powerful DG (and associated Commissioner) to prevail. This

has been particularly evident in the relationship between DG Trade and DG En-

vironment. More generally, there are significant and unresolved differences be-

tween the DGs over the extent to which environmental matters should be dealt with

in the context of the WTO (Bretherton and Vogler 2000). A documented case of

how the bureaucratic politics of Brussels operated in the early phase of climate

policy making is provided by Skjaerseth (1994) in respect of proposals for carbon

taxation and the pressure toward a policy of conditionality with respect to any offers

made by the EC in relation to other OECD countries.

While there have been serious examples of incoherence over trade/environment

and animal rights issues in the past, there are indications that the political salience

accorded climate-change policy has had an effect. Contradictions between short-

run economic interests and longer-term sustainability are hardly unique to the EU

and it must be of some significance that the Union has now agreed that it can bear

the costs to competitiveness arising from action to fulfill its Kyoto obligations. This

was, in fact, a reversal of pre-1997 policy that made the participation of all the EU’s

developed country trading partners a condition of any agreement. In post-2012

arrangements (2008–12 is the first commitment period under the Kyoto Protocol),

full multilateral involvement will be sought once again by the EU. Without it, the

Commission calculates that the abatement costs to the Union would rise by a factor

of three or four and the environmental effects would be ‘‘negligible’’ (Commission

of the European Communities 2005a:14–15).

Negotiating Ability

In areas of exclusive Community competence, notably trade, the Commission ne-

gotiates on behalf of the Member States albeit on a mandate agreed and monitored

by the Council (specifically by the Article 133 Committee). In environmental policy

areas under shared competence, the interlocutors of the EU are sometimes pre-

sented with the spectacle of a chameleon actor, which can change its form in the

course of a day or even an hour. On issues within Community competence the

7

Furthermore, it was pointed out that some EU members were allowed an unfair economic advantage under the

burden-sharing agreement by being allowed substantial increases in their emissions.JOHN VOGLER AND CHARLOTTE BRETHERTON 13

Commission will lead, while elsewhere the Presidency will take on this role. Climate

change was initially seen as an issue area for which the Community had minimal

competence and the early INC negotiations, to write the text of the UNFCCC, did

not formally include the Community. These talks were also marked by a lack of EC

discipline, with Member States openly disagreeing with each other.8 Nonetheless,

the Community signed the Framework Convention as an REIO and the subsequent

formula has been that the Union negotiated ‘‘at 16’’ and now ‘‘at 26’’ with the

Commission represented alongside the Member States. In practical terms, the

participation of the Commission is essential even if issues are not strictly within its

competence. Only the Commission is capable of organizing the Union’s complex

responses to its Kyoto obligations in the ECCP and the ETS.

In climate talks it is the Member State holding the Presidency that leads for the

Union as a whole and much may depend upon the willingness and capability of the

‘‘President in Office’’ to pursue the climate-change agenda.9 The rotating Presi-

dency does not encourage the holding of a firm course and some smaller Member

States are ill-equipped to undertake the burdens of leadership, a problem that has

been highlighted by enlargement to 25.10 The complexities of climate negotiations

impose a heavy burden and this is one area of external relations that would clearly

benefit from institutional reform and a permanent Presidency (van Schaik and

Egenhofer 2003). There is also a requirement to relate to an agreed mandate from

the Council and to hold coordination meetings at conferences on top of national

delegation meetings and plenary and working group. In short, the EU’s climate

negotiating system is ponderous and poses ‘‘Herculean’’ tasks of coordination

(Grubb and Yamin 2001:285). This hardly makes for flexibility in negotiation. Un-

der some circumstances, rigidity can become a bargaining tool but often it means

that the EU tends to be primarily reactive. There is substantial evidence of this

throughout the Kyoto negotiations where the EU tended, in the main, to accept

U.S. amendments and proposals as long as EU ‘‘red lines’’ on quantified emissions

limitations were defended. This was certainly the case with the flexibility mech-

anisms that were the U.S. contribution to the 1997 agreement. However, it should

not be forgotten that at a strategic level, the EU provided ‘‘the ambition that drove

the numerical targets of the Kyoto Protocol’’ (Earth Negotiations Bulletin 1997:15).

After 2000, the Union sustained its commitment to the Protocol through an

intense and coordinated diplomatic effort undertaken in the interval between CoP

6 and the reconvened CoP 6 bis at Bonn. During this brief period EU diplomatic

missions were undertaken to Australia, Canada, Japan, the Russian Federation, and

Iran, while the governments of several Member States, including the U.K., France,

and Germany, showed consistency by simultaneously putting diplomatic pressure

8

The INC came under the sponsorship of the UN General Assembly, a body in which the Community still has

very limited recognition (it has to negotiate for anything more than observer rights every time a major UN con-

ference occurs and the achievement of the following footnote to Agenda 21, prior to UNCED, was regarded as an

achievement by the Commission: ‘‘When the term Governments is used, it will be deemed to include the European

Economic Community acting within its areas competence’’). In the General Assembly (but not the Security Council),

extensive progress has been made in ensuring that the 25 Member States coordinate their positions and vote as the

EU.

9

In 2005, the U.K. Presidency made climate change one of its twin objectives, along with aid and debt relief for

Africa. As a large Member State with significant scientific and other resources it was able to mount a sustained

campaign, particularly directed at the United States. This exploited the fact that the U.K. also assumed the Pres-

idency of the G8 in 2005 and was able to set the agenda for the Gleneagles G8 summit in July. The European

Commission has also been represented at G7 and then G8 meetings since 1977 and participates fully in their

preparation. Four Member States, France, Germany, Italy, and U.K., are G8 members and the timing of their G8

presidencies is coordinated with their occupancy of that position within the EU.

10

During the Kyoto negotiations, for example, the ‘‘President in office’’ was Luxembourg. In such circumstances,

the use of the ‘‘troika’’ format may be useful, involving, in this case, the United Kingdom as the next holder of the

Presidency. There will also be extensive reliance upon the General Secretariat of the Council of Ministers. Its officials

provide an ‘‘institutional memory’’ as Presidencies come and go as well as assisting small Member States with

document drafting and other functions associated with holding the Presidency.14 European Union on Climate Change

on the governments of key countries, notably Japan (Earth Negotiations Bulletin

2001). In many ways, this effort demonstrates what the Union can achieve with the

coordinated use of the bilateral diplomatic assets of its Member States, up to and

including contacts at the head of government level. Most important was EU action

in the final phase to ensure Russian ratification. The agreement was finalized at the

first post-enlargement EU–Russia summit in May 2004. Although linkage is offi-

cially denied, it is apparent that the Union was prepared to use its power as a trade

actor to exchange support for Russian entry into the WTO for Kyoto ratification.11

Preparedness to act in this way not only demonstrates the strategic importance of

ratification for the Union but also the extent of its actor capability once trade

instruments are brought into play. The European Parliament has even called upon

the Commission to consider the possibility of ‘‘border adjustment measures on trade

in order to offset any competitive advantage producers in industrialised countries

without carbon constraints might have . . .’’ (European Parliament 2005:11).

Public support must, in the longer term, underpin the Union’s actor capability.

Since the rejection of the Constitutional Treaty by French and Dutch referenda in

mid-2005, the relationship between the structures of the EU and its public has been

subject to serious questions with ramifications that threaten to preoccupy the Union

for years. The external relations provisions of the Treaty, in abolishing the rotating

Presidency and installing a foreign minister and External Action Service, would

have had real benefits for the conduct of environmental diplomacy. More worrying

is the evidence, in recent national referenda and discussions of the Constitutional

Treaty, that there is widespread public misunderstanding and distrust of the Union

that may well weaken the EU as a global actor. However, climate-change policy

enjoys general public support across the 25 Member States as does the EU’s sup-

posedly benign world role, in contra-distinction to negative perceptions of the

United States.12 It has to be said that, as yet, no direct sacrifices have been required

of EU citizens in pursuit of these ends. For its part, the European Parliament has

been generally supportive and the opinion of its rapporteur, not always an un-

critical source on the doings of the Commission and Council, was that:

The EU has given proof of its leadership capacities. Without the Union’s deter-

mination, it would not have been possible to fragment the ‘‘umbrella group’’, thus

ensuring that other countries did not follow the example of the U.S. and rescuing

the Kyoto Protocol from an otherwise certain death. (European Parliament

2002:3)

The EU’s Role as Protagonist

In the decade between the negotiations for the original UNFCCC and U.S. de-

nunciation of the Kyoto Protocol, climate negotiations came to revolve around two

11

The critical diplomacy with Russia was conducted at the highest political level by a small number of large

Member States. There were a range of issues related to EU support for Russian WTO accession but the energy

agreement appears to have been crucial. This involved an effective doubling of Russian domestic natural gas prices

to industrial users by 2010 (Commission 2004a). While denying actual linkage, Russian President Putin was pre-

pared to acknowledge that ‘‘The European Union has made concessions on some points during the negotiations on

the WTO. This will inevitably have an impact on our positive attitude to the Kyoto process. We will speed up Russia’s

movement towards ratifying the Kyoto Protocol’’ (European Commission Delegation Moscow 2004).

12

The pan EU evidence of often widely variant opinion trends is collected regularly in Eurobarometer surveys.

These found in 2004 that climate change was the third highest priority environmental concern after water pollution

and man-made disasters, and that nine out of 10 citizens held that policy makers should give equal weight to

environmental and socioeconomic concerns. Roughly equal proportions of EU citizens (33% in each case) consider

the Union or the Member States to be the appropriate level for environmental action (Commission of the European

Communities 2005b:8,31,38). There is no recent polling evidence on popular views of EU climate policy toward the

U.S., but there is a general view that the U.S. has played a negative world role (58%) while the EU is regarded as a

positive promoter of peace (61%) (Commission 2004:29).You can also read