R easons why farmers in Australia adopt the Internet

←

→

Page content transcription

If your browser does not render page correctly, please read the page content below

Electronic Commerce Research and Applications 2 (2003) 27–41

www.elsevier.com / locate / ecra

Reasons why farmers in Australia adopt the Internet

John Rolfe a , *, Shirley Gregor b , Don Menzies c

a

Faculty of Business and Law, Central Queensland University, P.O. Box 197, Emerald, QLD 4720, Australia

b

School of Business and Information Management, Australian National University, Canberra, ACT 0200, Australia

c

School of Business and Information Management, Australian National University, Rockhampton, QLD 4700, Australia

Received 29 June 2002; received in revised form 1 October 2002; accepted 1 February 2003

Abstract

Landholders in rural Australia are increasing their use of computers and the Internet. In part, this is because of the

increased availability of hardware, software and communications infrastructure at reasonable cost. However, it is unclear

what all the benefits of adopting a new technology are. It may be that the primary benefits are simply cost reduction; for

example, the time saved in financial bookkeeping. Other reasons might include potential gains to production, keeping pace

with regulatory and other external changes, or improved marketing opportunities. These issues are explored in relation to the

grains and beef industries of the Central Queensland region.

2003 Elsevier Science B.V. All rights reserved.

Keywords: Computing; Internet; Agriculture

1. Introduction ing e-commerce). There are many indicators that

suggest that the level of penetration of information

The growth in the US economy over the past technology is broadly similar between Australia and

decade can be partly explained through the contribu- the US [15].

tion of information technology [2,9,12,16]. Advances Agriculture is a forgotten sector in the debate

have occurred through improved productivity (par- about the contribution of information technology to

ticularly in the services sector), and changes in the economic growth. For example, most studies of

labour and capital markets. These advances occur in productivity changes in an economy focus on the

part because of the integration of computing hard- non-farm sector [3,16]. Because information technol-

ware and software into production processes (allow- ogy applications allow not just direct productivity

ing greater productivity and better use of labour and changes, but also organisational changes, marketing

capital), the development of new services and prod- and consumer relationship changes, and better con-

ucts (including the Internet), and the improved trol over supply chain management, the greatest

linkages between businesses and consumers (includ- benefits from adoption of information technology

have tended to be at the manufacturing and service

*Corresponding author. Tel.: 161-7-4980-7081; fax: 161-7- industry levels [3]. Agriculture, firmly in the primary

4982-2031. industry sector, is generally assumed to have fewer

E-mail address: j.rolfe@cqu.edu.au (J. Rolfe). gains to make from information technology.

1567-4223 / 03 / $ – see front matter 2003 Elsevier Science B.V. All rights reserved.

doi:10.1016 / S1567-4223(03)00004-828 J. Rolfe et al. / Electronic Commerce Research and Applications 2 (2003) 27–41 It could be expected that some innovators in electronic component. Second, many of the benefits agriculture would experiment with information tech- and costs relating to information technology are not nology. However, the use of information technology priced in markets. Non-priced benefits range from by agriculture appears to be expanding beyond this many free products available on the Internet to the group [14]. In the US, the proportion of farmers who social benefits in isolated areas of gaining e-mail had access to the Internet had risen from 13% in access. Non-priced costs include the additional time 1997 to 29% in 1999 [10]. By June 2000, 58% of spent on solving problems, and the potential for Australian farms had computer access and 34% had harmful events like virus infections or data loss. Internet access [1]. Farmers are notoriously con- In this paper, we report an attempt to evaluate servative and cautious with new technology. The some of these issues though a case study of farmers high rates of takeup indicate that farmers are gaining in a particular region of northern Australia. The case real benefits from using information technology, and study focused on broadscale cropping and beef cattle that they judge the benefits to be greater than the industries, which tend to be small business enter- costs of time, money and frustration involved in prises supplying generic markets and not be highly getting to grips with a new technology. However, specialised in production. As a consequence, these there has been little work to identify and quantify industries could be expected to be at the low end of these benefits and costs. demands and uptake for information technology Identifying why farmers in Australia take up services. If producers in these industries report that information technology is important for two reasons. there are net benefits in the use of information The first is that if productivity can be improved from technology, the results should be broadly transferable using information technology, this might be an across other agricultural industries and regions of important way of achieving further growth in ag- Australia. riculture. Determining where opportunities lie for productivity gains, how they might be achieved, and what are the barriers and triggers for takeup of 2. The takeup of information technology in information technology are important questions re- rural areas lated to this issue. The second issue is about the net benefits that Australia is one of the leading nations in the world might be expected from adopting information tech- in terms of Internet infrastructure, penetration and nology. There is a large political debate in Australia use [15]. By September 2001, 67% of Australian about the provision of appropriate information tech- households owned or leased a computer, and 52% nology services to rural and regional areas, and the were online [15]. The proportion of farms in Aus- appropriate level of public funding (Government tralia with computers rose from 40 to 58% between expenditure), quasi-public funding (community ser- March 1998 and June 2000 (see Table 1). Internet vice obligations by telecommunications providers) access rose from 11 to 34% over the same time and private funding. Estimates of the level of bene- period, with a 91% increase in access between fits and costs will be important to help provide March 1999 and June 2000 (see Table 2). Queens- information about the likely demand for information land was third lowest in terms of proportion of farms technology services, and the efficient use of public with a computer, and second lowest in terms of funding. proportion of farms with access to the Internet. While These goals are not easily achievable. First, mea- these rates of takeup are very high, rates of computer surement of e-commerce and e-business activities ownership and Internet access still lag behind the and information technology contributions are very small business sector [15,18]. difficult [5]. Most national statistics are collected on The grains, sheep and beef sector reported both an industry basis, and do not identify the contribu- the lowest proportion of computer use (55%), and tion of particular components. It is difficult to the lowest proportion of farms using the Internet identify transactions that occurred electronically, or (31%) [10]. There was a strong positive relationship to apportion actions and transactions that have an between farm size (as measured by value of turnoff),

J. Rolfe et al. / Electronic Commerce Research and Applications 2 (2003) 27–41 29

Table 1

Farms using a computer, by state / territory

March 1998 March 1999 June 2000

Farms using a computer Farms using a computer Farms using a computer

No. % No. % No. %

New South Wales 16 934 40 21 545 49 23 028 53

Victoria 13 538 37 18 075 49 21 549 58

Queensland 11 311 37 13 870 45 17 841 58

South Australia 6795 43 8361 53 10 180 64

Western Australia 6850 49 8270 59 9466 68

Tasmania 1608 36 2186 49 2507 57

Northern Territory 196 52 241 65 260 71

Australian Capital T. 58 55 66 64 67 70

Australia 57 290 40 72 615 49 84 898 58

Source: Ref. [1].

and the use of the computer and Internet [10]. There value of farm production. Larger farms in the US

are claims that farm users of the Internet actually use with gross sales of more than US$100 000 had

it for longer periods than do the general population approximately double the computer use and Internet

[7], implying that reported usage rates are under- access of farms with incomes between US$10 000

stated. One explanation is that farmers tend to access and US$100 000 [10].

the Internet for both business and recreation pur- Many users of the Internet appear to be accessing

poses, while metropolitan users tend to be recreation it to gain information, and only a small proportion

only. are using it to purchase goods and services [7]. Other

There has also been rapid adoption of the Internet important activities include education and training

in agriculture in the US. While only 13% of farmers activities, access to services (such as electronic

had access in 1997, the proportion had risen to 29% banking), and social and recreational activities.

in 1999 [7]. Computer access rose from 38 to 47% Using the Internet for selling or teleworking appears

over the same time period, indicating that Australian less important at this stage for rural industries.

farmers may have been slightly ahead in takeup in The rate of computer and Internet takeup indicate

this area. Like Australia, computer ownership and that farmers perceive real benefits in adopting in-

Internet access in the US is closely related to the formation technology. Yet as a primary industry,

Table 2

Farms using the Internet, by state / territory

March 1998 March 1999 June 2000

Farms using the Internet Farms using the Internet Farms using the Internet

No. % No. % No. %

New South Wales 5006 12 8231 19 13 596 31

Victoria 3621 10 6174 17 12 270 33

Queensland 3075 10 4830 16 9811 32

South Australia 1896 12 3030 19 6442 40

Western Australia 1428 10 2548 18 5621 40

Tasmania 552 12 973 22 1539 35

Northern Territory 81 22 114 31 180 49

Australian Capital T. 21 20 27 26 40 42

Australia 15 680 11 25 927 18 49 499 34

Source: Ref. [1].30 J. Rolfe et al. / Electronic Commerce Research and Applications 2 (2003) 27–41

agriculture appears to have limited possibilities to weather forecasts and commodity prices are easily

use information technology to increase economic accessible on the Internet, but this simply represents

outputs. This raises questions about whether the another way of getting information that is already

benefits of information technology adoption will be widely available. While these improvements in in-

small in this sector, with corresponding implications formation technology may be welcomed by the

for the rate and extent of the takeup. To explore agricultural sector because of convenience and time

these issues, the potential benefits and costs of saving, they will do little to generate production

adopting information technology are explored next. increases by themselves.

Improved communication technology is reducing

transaction costs in areas such banking, stockbrok-

3. The benefits and costs of adopting ing, and supply chain management. There are many

information technology examples, such as electronic banking, where primary

producers now have better and cheaper communica-

There are a number of benefits that farmers and tion services, with improved efficiencies as a result.

graziers can expect to gain from access to infor- There have also been suggestions that improved

mation technology. For convenience, these can be communication would improve the marketing of

separated into two main areas. The first reflects a products by cutting out middle marketers and reduc-

focus on cost reduction, where computers and Inter- ing costs [14]. Here, the benefits of e-commerce are

net access are used to automate tasks and reduce that more direct links can be established between

operating costs. In this case, the key benefits of producers and consumers, and the producers can pick

adopting information technology flow from cost up the gains from the reduced marketing costs.

savings. The second area relates to benefits that However, these potential gains from direct marketing

farmers and graziers might gain from encouraging remain largely unfulfilled, mostly because inter-

innovation. Under this scenario, information technol- mediate links in the marketing chain provide very

ogy allows and encourages new ways of doing real services that are difficult to replicate [14,20].

things, stimulating additional productivity. In this

case, the benefits of adoption come from increased 3.2. Information technology and direct productivity

productivity, rather than from cost reduction. Here, gains in agriculture

the case for each of these possibilities is examined in

more detail. Adoption of information technology impacts may

lead to direct production gains, as opposed to

3.1. Information technology and cost reduction in reductions in operating costs. There are several areas

agriculture where this might happen, including:

The initial focus of using computer hardware and • better retrieval and evaluation of available data

software in agricultural enterprises is usually in the for management purposes,

field of accountancy and budgeting. This was the • development of management decision support

dominant application for computers in the beef systems,

industry in the late 1990s [13]. Some benefits here • development of processes for quality assurance

come in the form of reduced inputs, as computing and external regulatory compliance require-

resources are used to replace labour and accountancy ments,

fees. Computers are also replacing manual processes • better links to remote sensing and geographic

for data entry and storage [6], as the retrieval process information systems (GIS) data,

is much more efficient when mechanised. Word • better links to technical and other information,

processing is also an important use, and fax ma- • better links to agricultural suppliers,

chines are now commonplace. • more direct feedback from customers and con-

These uses represent slightly more efficient ways sumers,

of carrying out previous functions. In the same way, • improved supply chain management,J. Rolfe et al. / Electronic Commerce Research and Applications 2 (2003) 27–41 31

• opportunities for marketing and other networks larger farms. It is only the larger scale enterprises

to emerge. that can afford the investment in capital and person-

nel. As decision support software becomes more

Some commentators on agricultural trends suggest available and successful in micro management, it

that the next decade will see the growing use of GIS may offer even greater economies of scale to larger

data, increasingly detailed farm-level record keeping, farms, and allow further amalgamation of farms and

and increased reporting requirements for items like development of corporate farming.

chemical use [6]. Satellite and GIS applications are Better links to agricultural suppliers is likely to

already emerging in Australia. In one pilot study in occur through reverse flows of information [10]. This

Western Australia, satellite images are used by is when suppliers are able to track farmers who

woolgrowers to predict pasture biomass and pasture explore their sites, and by building up profiles of

growth rates [17]. This information can assist man- their customers, target products and advertising

agement decisions such as grazing rotations, feed directly. There are economies of scale in profiling

budgeting, fertiliser applications and other ‘precision customers this way, suggesting that it is the larger

farming’ techniques. suppliers that will be dominant.

There are already examples where improved data The Internet may also help farmers to market their

sets are being used to improve management in areas produce more effectively. Better information will

such as fertiliser application and water use ef- allow some producers to diversify and market niche

ficiency. In many cases, such as the development of products directly to customers. Information will help

Breed Plan, the availability of data is coupled with producers of bulk commodities like grains to match

decision support systems to improve cattle selection supply with demand better, and to insure against

on specific traits. Other decision support systems that fluctuations in commodity prices. Information tech-

have been developed involve climate predictions and nology allows growers to form alliances more easily

rainfall probabilities. for marketing their product. It also allows for closer

A key benefit of access to the Internet is the integration of supply chains through the improved

increased supply of information to farmers. Infor- flow of information, establishment of quality assur-

mation takes many forms, including those relating to ance programs, better information and traceback, and

production, farm inputs and machinery, and identifi- closer links between market players [4,11,19].

cation of buyers, sellers and favourable contracts

[10]. It is likely that the Internet will transform the 3.3. Information technology and indirect

farm input supply sector in particular, and the output productivity gains

marketing sector as well. Farmers will have the

possibility to use the Internet to learn about and buy While computers are useful in replacing labour for

about a wide range of inputs, to search for lower mechanical calculations, these are not the primary

costs, and to order directly from manufacturers. In purpose of computers in most business applications

these cases, use of the Internet will reduce spending in the non-farm sector. Computers, when aligned

through local and regional suppliers, but should with other elements of information technology, can

make rural producers more profitable. be broadly applied to reduce the costs of coordina-

Information by itself quickly results in overload. It tion, communication, and information processing [3].

is the decision support systems that enable us to Because these are such integral parts of business

make use of the information that are important. In production systems in a modern economy, improve-

some cases these are achieved through people de- ments here stimulate wider economic restructuring.

velopment, e.g., training staff to make the best use of Here the arguments about information technology

available data. The real gains are to be made in the driving gains in innovation in the non-farm sector are

development of improved decision support software. analysed. These are then related to potential gains in

It is possible that the extent of investment in such agriculture.

software and the learning process explains why From an innovation perspective, the real gains

computer and Internet usage is so much higher on with information technology come from business32 J. Rolfe et al. / Electronic Commerce Research and Applications 2 (2003) 27–41 managers finding new processes and organisational ing and / or allows specialisation through better links structures that employ the new technology in differ- to consumers. ent ways. These encompass changes in the way that Second, there are often considerable lags between firms communicate within the organisation (hence investment in information technology and real prod- the opportunities to change structure), between other uctivity gains. The size of the investment in in- businesses (changes in the way that supplies are formation technology, the extent to which it is sourced), and between customers. Just as the steam integrated into operations, and the ability of mana- engine, the electric motor and the telegraph each gers to create new production and management transformed economies by changing the form, loca- opportunities are all indications of potential prod- tion, and pattern of production, so does information uctivity gains. technology allow innovation to be the key to prod- It is not always apparent how applicable these uctivity gains [3]. Business investments in infor- lessons are for agriculture. Most operations are run mation technology do not simply generate normal as family farms, so communication needs are simple. rates of return by replacing labour, but allow much The complexities come from variabilities in weather greater productivity gains to be made. and natural processes, rather than from trying to These arguments led to a search for a relationship coordinate complex inputs and outputs. Much of the between the takeup of information technology and information that is used in farming is an amalgam of productivity in an economy. Up to the 1990s, it was personal observation, inherited knowledge, advice difficult to identify that takeup of information tech- from peers and technical advice, rather than in- nology had any influences on productivity within an formation that has been collected scientifically. In economy. After that point though, much more con- addition, coordination, communication and informa- crete evidence has been found that information tion needs are probably a much smaller proportion of technology is generating real gains [16]. One expla- effort in agricultural enterprises than for businesses nation for this long lead time is that investment in involved in the secondary and tertiary sectors. It is information technology entails corresponding invest- with these ambiguities in mind that we turn to ment in some intangible items such as staff training, identifying the costs and benefits of using infor- building up a database, software development, or- mation technology in agriculture in a particular case ganisational restructure and designing new processes study. [3]. It is only when these have been completed that the net productivity gains and profits will emerge. 3.4. The design and application of the survey Another explanation of the delays in productivity instrument gains is that it takes business managers some time to find innovative ways of using the new technology The purpose of the research was to identify what within their business and market setting. A further the key benefits and costs of adopting information explanation is that there is some threshold level of technology were for beef and grain growers in the investment in information technology before enough Central Queensland region of Australia. These are capital stock and expertise develops within a firm to the dominant land uses in that region. Other primary generate productivity gains. industries such as irrigation, mining and forestry, and Some lessons for agriculture can be drawn from other land uses such as national parks, occupy only a this brief overview. First, the real gains from in- small proportion of the land mass. In line with the formation technology may not be in automating national data [10,15], the beef and grain producers of existing mundane tasks, but in encouraging innova- the region would be expected to have low takeup tion to occur. Where agricultural businesses involve rates of information technology relative to other coordination, communication, and information pro- agricultural sectors. cessing tasks, the opportunities for using information The key research question to address was whether technology will be high. This means that information adoption of computers and Internet use was pro- technology is likely to provide most benefit to viding more benefits in the form of reduced oper- agriculture when it improves complex decision mak- ating costs (including non-financial ones), or in the

J. Rolfe et al. / Electronic Commerce Research and Applications 2 (2003) 27–41 33 form of increasing productivity. The latter might directory using the region of Central Queensland and occur in several ways, through items such as better could include any producer with greater than 11 management, improved application of technology, or head. The DPI grains producers were supplied by a new opportunities for marketing. If the key purpose DPI grain Extension Officer and were sourced from a of information technology was to replace labour, list of producers subscribing to a DPI grains newslet- then its penetration and use in agriculture is likely to ter. Participants were selected at random from the be limited. If the key purpose is to improve manage- compiled lists (Table 3). ment and productivity, then the net benefits of The survey was collected through a mail-out / adoption are likely to be much higher. telephone response format. All surveys were mailed Survey data was collected to address the research out in batches of 20 per week from October to question. Producers were asked to rank, in turn, how December 2001. Respondents were contacted by important computers and Internet usage were to their telephone in the following week and asked if they business. These rankings could then be tested against would like to participate. Respondents could either other variables collected in order to determine complete the forms in their own time and return whether it was the cost reduction or the productivity them by post, or could give the answers to the enhancing activities that were significant in explain- interviewer over the telephone. One of the research- ing the rankings. The self-assessment approach im- ers and a research assistant performed the mailout plicit in the survey was used for two main reasons. and the telephone interviews. The first was that specific case study information on By January 2002, 75 responses had been received applications and adoption on information technology from 197 surveys issued. There were another 8% of in the region of interest was not available. The respondents who indicated that they did not own a second was that a large proportion of costs and computer and that the survey was not relevant to benefits involved are non-financial ones (i.e., im- them, giving an overall response rate of 46%. proved social communication), and personal assess- ment allows these factors to be considered. In the survey, respondents were asked a series of 4. Results and analysis questions about their use of computers and the Internet, as well for information about their en- The responses to the survey indicated generally terprise, and some demographic and attitudinal in- that computer usage and Internet access was im- formation. The key questions were about how they portant for business purposes. The involvement of rated the value of computer use and Internet use in respondents in the different sectors is summarised in their business according to a number of factors such Table 4 below. The off-farm income relates to the as use of accountancy records and use of online use of property assets for other purposes (e.g., farm banking. In order to encourage participation and tourism), while other income usually refers to people minimise the cognitive burden on respondents, most working part-time or full-time off the farm or questions were framed with Likert scale intervals, property. Of the 75 respondents, 70 indicated they where respondents could tick the category that best used a computer in their business, and 63 used the suited their operation. A list of the key variables for Internet. Fifteen respondents indicated that their time which responses were collected is summarised in spent on a computer had increased slightly over the Table 1. past 5 years, while 47 respondents (64%) indicated The list of potential respondents in central that their time commitment had increased signifi- Queensland was compiled from several sources. cantly. Only five respondents indicated that their These comprised lists of members of a grains time commitment had stayed the same or declined. cooperative (Capgrains Co-operative) and a beef Respondents were asked to rate some of the marketing cooperative (Bluegum Beef), and lists of software that they might be using for certain func- grains and beef producers supplied by the Depart- tions. The results, summarised in Fig. 1, show that ment of Primary Industries (DPI). The DPI beef accountancy packages receive very high ratings. It is producers were taken from the Queensland Tail Tag clear that almost all computer users are using their

34 J. Rolfe et al. / Electronic Commerce Research and Applications 2 (2003) 27–41

Table 3

Key variables collected in survey

Variable Description Coded

Electronic equipment Links to computer for production 0,1

Use per week No of days used each week 1,2,4,7

Time spent on computer Increase in use over past 5 years 1–4

Accountancy records Value of computer use 1–5

Production / property records Value of computer use 1–5

Budgeting Value of computer use 1–5

Forward planning Value of computer use 1–5

Word processing Value of computer use 1–5

Overall value of computer use (DV) Overall value to organization 1–5

Use of the Internet 0, 1

E-mail Value of Internet use 1–5

Weather Value of Internet use 1–5

Technical notes Value of Internet use 1–5

Market information Value of Internet use 1–5

Education and training Value of Internet use 1–5

On-line banking Value of Internet use 1–5

Social and recreation Value of Internet use 1–5

Buying goods Value of Internet use 1–5

Selling goods Value of Internet use 1–5

Own website Value of Internet use 1–5

Teleworking Value of Internet use 1–5

Feedback on product Value of Internet use 1–5

Shares and investments Value of Internet use 1–5

Overall value of Internet (DV) Overall value to organization 1–5

Better information Advantage in using the Internet 1–5

Reduced paperwork Advantage in using the Internet 1–5

Improved customer service Advantage in using the Internet 1–5

Faster for goods in Advantage in using the Internet 1–5

Better inventory control Advantage in using the Internet 1–5

Reduced costs of operation Advantage in using the Internet 1–5

Differentiation of services Advantage in using the Internet 1–5

Improved competitive advantage Advantage in using the Internet 1–5

Help from software suppliers Support for computer and Internet use 1–5

Help from Internet service provider Support for computer and Internet use 1–5

Govt funding for training Support for computer and Internet use 1–5

Significance of financial costs Cost of computer, Internet access and other resources for business 1–5

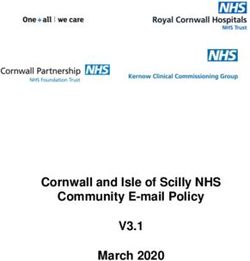

computer for some form of record keeping. There is

also widespread involvement with budgeting and

word processing, and much more limited in-

Table 4 volvement with production records and scenario

Responses by enterprise type planning.

Involvement Respondents Respondents to the survey were asked to rate the

with enterprise value of both computer use and Internet use to their

No. %

organisation. The number of responses given to each

Cattle 58 78.4

Grains 35 47.3 rating category is summarised below in Table 5. It is

Sheep 0 0 clear that the majority of respondents rate the value

Cotton 7 9.5 of computer use highly in their business. This

Off-farm 5 6.8 suggests that computer usage generates real value,

Other income 18 24.3

either in the cost savings or productivity gains area.J. Rolfe et al. / Electronic Commerce Research and Applications 2 (2003) 27–41 35

Fig. 1. Ratings given for value of different categories of computer use.

Table 5

Ratings given for value of computer and Internet usage

Value of: Very low Low Medium High Very high

Computer use 1 5 9 24 30

Internet use 9 5 16 23 9

Value for Internet usage also rated highly, but not to value for them. Reasons for use that achieved the

the same extent of computer usage. This suggests highest values were more timely and better infor-

that Internet usage does not generate nearly as much mation for decision making, and greater clerical

value as computer usage.1 efficiency (less paperwork). There was little support

Respondents were also asked to rate the value of for the Internet helping to improve service, control

Internet usage for different purposes. The responses inventories, reduce costs, or differentiate services,

are summarised in Table 6. The use of e-mail and and only modest support for the Internet helping to

electronic banking rated highly in value, followed by improve response time for goods ordered, or to

weather information, technical information, market improve competitive advantage.

information and social and recreational uses. In another section of the survey, respondents were

Respondents were also asked to rate their percep- asked about the time and dollar savings that might

tions about the advantages of using the Internet. The have been gained from access to the Internet. Two

results (see Table 7) show that the majority of respondents indicated that they had saved money

respondents viewed the Internet as achieving low making purchases over the Internet, while one re-

spondent indicated that Internet use had improved

sales results (selling lucerne hay). Eight respondents

1

Respondents to the value of computer usage question may have indicated that they had saved time through Internet

also incorporated their values for Internet usage within their use, and 14 respondents indicated that they had

response. improved management decisions. By contrast, 3536 J. Rolfe et al. / Electronic Commerce Research and Applications 2 (2003) 27–41

Table 6

Ratings given for value of different categories of Internet use

Number Very Low Medium High Very Median

using low (2) (3) (4) high score (range

(n575) (1) (5) 1–5)

E-mail 55 7 8 17 12 11 3

Weather 45 8 10 11 13 3 3

Technical 46 8 13 14 10 1 3

Market info 45 9 9 15 9 3 3

Education / training 33 6 9 13 2 3 3

Online banking 56 3 3 4 13 12 4

Social and recreation 51 19 9 15 8 0 2

buying goods 29 7 10 10 2 0 2

selling goods 17 11 5 0 1 0 1

Own web site 6 3 1 1 1 0 1.5

Teleworking 4 3 1 0 0 0 1

Feedback on product 9 2 1 5 1 0 3

Shares / investments 28 6 4 7 5 6 3

respondents (47%) indicated that the Internet al- 4.1. Do the benefits of computer usage relate more

lowed them better information access, especially in to cost savings or increased productivity?

relation to weather and market information.

The results allow some general conclusions about Some information about whether the benefits of

computer and Internet usage to be drawn. The computer usage relate more to cost savings than to

respondents have generally viewed computers as increases in productivity can be gained from the

creating real benefits for their businesses, especially survey results. It is clear that the time spent on

in the areas of financial management, budgeting and computer use has increased for almost all respon-

word processing. The value of Internet usage is not dents, with 67% of respondents indicating that their

ranked nearly so highly, perhaps because it has time spent had increased significantly. In comments,

simply tended to replace other forms of gaining many respondents indicated that there were signifi-

information about items such as weather forecasts cant time investments in learning to use the com-

and market prices. The use of the Internet and puter, and that there were low benefits to be gained.

electronic communication for personal and social However, it appears likely that in some areas, such

reasons does not appear to rank very highly, sug- as financial accounting, that there is a net savings in

gesting that the reasons for investing in information time.

technology generally relate to business purposes. There appears to be a significant group of respon-

Table 7

Ratings given for perceived advantage in Internet use

Very low Low Medium High Very high

Better information 16 9 22 14 7

Less paperwork 19 8 20 11 8

Improved customer service 36 9 13 4 1

Faster supply of goods in 27 8 8 8 0

Better inventory control 33 10 9 4 1

Reduced costs 27 12 16 5 0

Service differentiation 34 12 8 3 0

Competitive advantage 36 3 10 8 1J. Rolfe et al. / Electronic Commerce Research and Applications 2 (2003) 27–41 37

Table 8

Probit model modelling ‘high value’ and ‘low value’ computer use

Coefficient Standard error P value

Farmer is a grain producer 1.350 0.4673 0.0039

Uses computer linked equipment 0.6040 0.2049 0.0032

Uses computer for accountancy records 0.1463 0.0045 0.0730

Using computer for farm budgeting 0.0013 0.0004 0.0032

Restricted Log-likelihood 235.88

x 2 (df53) 20.95

dents who are using computers to achieve productivi- ‘medium’, ‘low’ and ‘very low’ responses were

ty gains, with 21 respondents indicating that they combined into the other response (‘low value’).

utilised electronic equipment (such as liveweight Under the second option, only the ‘very high’

scales and water scheduling equipment) in conjunc- responses formed the first value (‘very high’), while

tion with their computer. A number of respondents the other responses formed the second value

indicated that they were using software (e.g., Cattle (‘other’).

Plus) to track property production, and software (e.g., Under the probit model, choices between one of

Phoenix) to engage in budgeting and forward plan- the two options available are described in terms of

ning. This information suggests that for these respon- significant independent variables. Results of a probit

dents, the value of computer use may come through analysis generate a variate of coefficients similar to a

improved production opportunities. multiple regression exercise. A least-squares regres-

The survey data generated mostly nominal and sion exercise is used to generate starting values, and

ordinal data. For the purpose of testing the research then a bootstrapping procedure used to generate the

question and statistical analysis, the variables of probit model. Log-likelihood and x 2 statistics (for

interest, including the dependent variables, were testing model significance) are also generated.

ordinal. This restricts the pool of statistical tech- Two probit models for predicting values for

niques that may be used to construct relationships computer use are reported below. In the first model

between the variables. The key options for determin- (Table 8), the ‘high value’ of computer use was

ing relationships (apart from non-parametric correla- significantly related to four variables. Grain produc-

tion techniques) are canonical correlation analysis, ers and those using computer linked equipment,

probit models, and logit models.2 Canonical correla- accountancy packages and farm budgeting were

tion analysis is generally seen as a weaker (or last more likely to rank computers as being of high

resort) statistical technique than probit or logit value.

models [8]. The number of categorical variables in In the second model (Table 9), respondents who

the data set made it difficult to fit logit models. This rated computers as having a ‘very high value’ for

left probit models as the preferred technique for their business were more likely to be cattle produc-

testing the research question. ers, using computer linked equipment, have older

The probit model was established by creating computers, value farm budgeting and word process-

binary dependent variables for respondent percep- ing uses highly, and value Internet usage highly.

tions about the values of computer usage and Internet They were also less likely to be using computers for

usage to their businesses. Two options were created production / Quality Assurance records. There was

for each dependent variable. Under the first option, also a negative constant value in the model, indicat-

all the ‘high’ and ‘very high’ responses were com- ing that there were other unspecified variables im-

bined into one response (‘high value’), and the pacting on the choices made.

It is notable that use of computers for accountancy

2

The latter can be used by identifying the independent variables as purposes only emerges as significant for high value

categorical. usage, and not for very high value usage. In contrast,38 J. Rolfe et al. / Electronic Commerce Research and Applications 2 (2003) 27–41

Table 9

Probit model modelling ‘very high value’ and ‘other value’ computer use

Coefficient Standard error P value

Intercept 22.9820 1.1802 0.0115

Farmer is a cattle producer 1.8809 0.6465 0.0036

Uses computer linked equipment 0.8102 0.4886 0.0973

Age of computer 0.4682 0.1640 0.0043

Uses production / QA records 20.0012 0.0005 0.0099

Using computer for farm budgeting 0.0020 0.0005 0.001

Uses computer for word processing 0.0013 0.0006 0.0209

Value of Internet usage to farm 0.0021 0.0005 0.0210

Restricted log-likelihood 246.39

x 2 (df57) 35.2

Table 10

Probit model modelling ‘high value’ and ‘low value’ Internet usage

Coefficient Standard error P value

Intercept 27.999 3.016 0.008

Cattle producer 22.972 1.479 0.044

Job off-farm 23.452 1.387 0.013

Days / week access Internet 0.725 0.291 0.013

Value of e-mail usage 2.414 0.875 0.006

Value of weather information 21.521 0.566 0.007

Value of market information 20.754 0.329 0.022

Advantage of better information 1.656 0.612 0.007

from Internet

Advantage of less paperwork 1.060 0.465 0.023

Advantage of faster response 1.953 0.699 0.005

time for goods in

Restricted log-likelihood 242.94

x 2 (df512) 61.85

using computers for budgeting is significant for both 4.2. Do the benefits of internet usage relate more

models. Budgeting may be a traditional activity that to cost savings or increased productivity?

primary producers have automated with computer

use. It may also be a newer management tool that Information about whether the benefits of Internet

has been more recently adopted with the aid of usage relate more to cost savings or increased

information technology. Both explanations have productivity can also be drawn from the survey

some validity, making it difficult to test the research results. It is clear from the responses to the survey

question. However, to the extent that budgeting that very few respondents had achieved either re-

activities can be associated with new and improved duced costs from purchases in, or increased revenue

management, it would appear that the benefits of from sales out as a result of Internet use. As well,

computer use are moving from the cost minimisation only a small proportion of respondents indicated that

phase towards improved management and production they were achieving time savings through Internet

phases. use. However, there did appear to be some benefitsJ. Rolfe et al. / Electronic Commerce Research and Applications 2 (2003) 27–41 39

Table 11

Probit model modelling ‘very high value’ and ‘other value’ Internet access

Coefficient Standard error P value

Intercept 215.1794 5.11708 0.003013

Days / week access Internet 1.33608 0.499439 0.007469

Value of weather information 22.90725 1.06043 0.006114

Value of technical information 2.81311 1.00087 0.004944

Value of electronic banking 1.63008 0.64171 0.011079

Value of social and recreational use 0.649792 0.373337 0.081772

Restricted log-likelihood 225.68

x 2 (df55) 36.35

in terms of improved access to information (which about the weather or markets. Actions that save time

may be related to better management decisions), and and effort, such as electronic banking or ordering

access to electronic banking services (which relate to goods to speed up delivery time, appear to be key

both management and financial accountancy needs). components in providing value. The significance of

The latter would also be important in terms of time technical information (Table 11) may suggest the

saving and convenience, as the trips would reduce importance of Internet access in increasing prod-

the number of trips to town and other centers. uctivity in some businesses, while the importance of

The results of the ‘high value / low value’ model social and recreational uses (Table 11) highlight that

(Table 10) indicate that the groups most likely to put these values are also important.

a low value on Internet use are cattle producers,

those with jobs off-farm,3 and those who want

weather and market information. The groups that are 5. Conclusions

most likely to put a high value on Internet use are

those who access the Internet more frequently each Information technology (including computers and

week, those who rate e-mail highly, see that it Internet access) have helped to transform the non-

provides more timely and better information for agricultural sectors of western economies and drive

decision making, want less paperwork, and want a real productivity gains. In recent years, agricultural

faster response time for ordering goods in. enterprises have adopted information technology at a

The results of the ‘very high / other value’ model high rate, suggesting that agricultural producers are

(Table 11) indicate that respondents with a high gaining real benefits from employing information

value for weather information are less likely to put a technology in their businesses. However, these bene-

high value on Internet use. The groups most likely to fits have been difficult to identify and quantify.

put a high value on Internet use are those with higher In this paper, survey information from primary

rates of access, and those who put a high value on producers in central Queensland has been analysed

technical information, electronic banking, and social with probit models to identify factors that are

and recreational uses. associated with perceptions of value for computer

It appears from these results that the respondents use and Internet access. The key goal was to identify

who value Internet use highly are those who can be whether benefits could be associated mainly with the

classified as wishing to improve their efficiency. It is reduction of costs or increases in productivity in

unlikely that high value simply comes from acces- agricultural enterprises.

sing information more easily, such as information While most enterprises surveyed use computers

for financial accounting purposes, there were mixed

results for this variable as an explanator for percep-

3

This group may have access from their other work location. tions of value about computer usage. The variable40 J. Rolfe et al. / Electronic Commerce Research and Applications 2 (2003) 27–41

emerged as significant when explaining ‘high value’ Acknowledgements

categorisations, but not significant for the ‘very high’

category. This suggests that primary producers who The research reported in this paper has been

perceive most value in computer usage are moving supported by the Australian Research Council, the

beyond the cost-minimisation applications such as Capgrains Cooperative, the Queensland Department

financial packages. Other factors that were signifi- of Primary Industries, and the Queensland Depart-

cant in explaining ‘very high’ value responses were ment of Innovation and Information Economy.

the use of budgeting programs, computer-linked

equipment and the Internet. To the extent that these

variables can be associated with new and improved References

management, it would appear that the benefits of

computer use are moving from the cost minimisation [1] Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS), Use of Information

Technology on Farms, Australia (Cat. No. 8150.0), Canber-

phase towards improved management and production

ra, 1999–2000.

phases. This will lead to computers being used to [2] M.N. Baily, R.Z. Lawrence, Do we have a new E-conomy,

achieve production gains. American Economic Review 91 (2) (2001) 308–312.

With regard to Internet usage, respondents to the [3] E. Brynjolfsson, L.M. Hitt, Beyond computation: Informa-

survey were not generally able to identify either cost tion technology, organizational transformation and business

performance, Journal of Economic Perspectives 14 (4)

or time savings or production gains resulting from (2000) 23–48.

access. However, the statistical analysis did identify [4] B.L. Buhr, Information technology and changing supply

that high value ratings for Internet access did appear chain behaviour: a discussion, American Journal of Agricul-

to be associated with the use of technical infor- tural Economics 82 (2000) 1130–1132.

[5] B. Fraumeni, E-commerce: measurement and measurement

mation, electronic banking, and social and recrea- issues, American Economic Review 91 (2) (2001) 318–322.

tional uses. It appears that the value of the Internet is [6] G.B. Frisvold, Data, information, and rural environmental

not necessarily in replacing other means for sourcing policy: What will the next ten years bring?, Review of

information, such as about the weather. Some value Agricultural Economics 22 (1) (2000) 237–244.

[7] J. Groves, J. Da Rin, Economic and Social Impacts of Farm

comes from making processes more efficient, as in

Internet Use, Rural Industries Research and Development

the use of electronic banking services or ordering Corporation Publication No. 99 / 35, Canberra, 1999.

goods on-line. Some value comes from providing [8] J.F. Hair, R.E. Anderson, R.L. Tatham, W.C. Black, in:

better access to information (especially technical Multivariate Data Analysis, 5th Edition, Prentice-Hall Inter-

information). national, Englewood Cliffs, NJ, 1998.

[9] D.W. Jorgenson, Information technology and the US

The producers surveyed were predominantly

economy, American Economic Review 91 (1) (2001) 1–32.

broad-scale grain and beef producers. These groups [10] D.R. Just, R.E. Just, Harnessing the Internet for Farmers,

tend to be relatively low users of information Choices, Second Quarter (2001) 36–40.

technology compared to other Australian farmers. [11] J. Kinsey, A faster, leaner, supply chain: new uses of

This suggests that the results of this survey should be information technology, American Journal of Agricultural

Economics 82 (5) (2000) 1123–1129.

broadly applicable to other sectors of Australian

[12] R.E. Litan, A.M. Rivlin, Projecting the economic impact of

agriculture. Indeed, it is likely that other sectors are the Internet, American Economic Review 91 (2) (2001)

more advanced in employing information technology 313–317.

for productivity gains. [13] P. Martin, D. Riley, J. Jennings, C. O’Rourke, C. Toyne, The

These results hide a great deal of detail about Australian Beef Industry 1998, ABARE Research Report

98.7, Canberra, 1998.

farm-level benefits that would be identified in spe-

[14] R.A.E. Mueller, E-Commerce and entrepreneurship in ag-

cific case studies. There are examples of individual ricultural markets, American Journal of Agricultural Econ-

producers who are using information technology in omics 83 (5) (2001) 1243–1249.

innovative ways to reduce costs, increase production [15] National Office for the Information Economy (NOIE),

and market their goods more effectively. However, Advancing Australia: The Information Economy Progress

Report, Canberra, 2002. http: / / www.noie.gov.au / publica-

for the group of primary producers surveyed, it

tions / NOIE / progress report / index.htm.

remains difficult to quantify accurately the amount of ]

[16] S.D. Oliner, D.E. Sichel, The resurgence of growth in the

benefit that they gain from using information tech- late 1990s: Is information technology the story?, Journal of

nology. Economic Perspectives 14 (4) (2000) 3–22.J. Rolfe et al. / Electronic Commerce Research and Applications 2 (2003) 27–41 41

[17] W. Pyper, Space-age farming, Ecos 109 (2001) 20–23. [19] V. Salin, Information technology and cattle-beef supply

[18] J.C. Rolfe, The uptake of information technology by busines- chains, American Journal of Agricultural Economics 82 (5)

ses in the Central Highlands region of Queensland, in: S. (2000) 1105–1111.

Marshall, W. Taylor, X. Yu (Eds.), Proceedings of the IT in [20] J. Williams, E-Commerce and the lessons from nineteenth

Regional Areas Conference, Central Queensland University, century exchanges, American Journal of Agricultural Econ-

Rockhampton, 2001. omics 85 (5) (2001) 1250–1257.You can also read