Public diplomacy Gastro Diplomacy - ISSUE 11, WINTER 2014 - Squarespace

←

→

Page content transcription

If your browser does not render page correctly, please read the page content below

Make an impact.

Public Diplomacy education at USC:

Two-year Master of Public Diplomacy (M.P.D.)

One-year Professional Master of Public Diplomacy

Mid-career Summer Institute in Public Diplomacy

for professional diplomats

Home of the USC Center on Public Diplomacy

at the Annenberg School, online at

www.uscpublicdiplomacy.com

• Home of the nation’s first master’s degree program in public diplomacy

• Combines the strengths of USC’s Annenberg School for Communication and

Journalism and Dornsife College’s School of International Relations

• Center on Public Diplomacy recognized by the U.S. State Department as

“the world’s premier research facility” in the field

• Strong institutional relationships with embassies, government agencies and

nongovernmental organizations around the world

• Innovative perspective informed by Los Angeles’ role as international

media capital and key position on Pacific Rim

• Energetic and international

student body

annenberg.usc.edu

The University of Southern California admits students of any race, color, and national or ethnic origin.ABOUT

editorial policy

Public Diplomacy Magazine seeks contributions for each themed issue based

on a structured solicitation system. Submissions must be invited by the editorial

board. Unsolicited articles will not be considered or returned. Authors interested

in contributing to Public Diplomacy Magazine should contact the editorial board

about their proposals.

Articles submitted to Public Diplomacy Magazine are reviewed by the editorial

board, which is composed entirely of graduate students enrolled in the Master of

Public Diplomacy program at the University of Southern California.

Articles are evaluated based on relevance, originality, prose and argumentation.

The editor-in-chief, in consultation with the editorial board, holds final authority

for accepting or refusing submissions for publication.

Authors are responsible for ensuring the accuracy of their statements.

The editorial staff will not conduct fact checks, but edit submissions for basic

formatting and stylistic consistency only. Editors reserve the right to make changes

in accordance with Public Diplomacy Magazine style specifications.

Copyright of published articles remains with Public Diplomacy Magazine. No

article in its entirety or parts thereof may be published in any form without proper

citation credit.

about public diplomacy magazine

Public Diplomacy Magazine is a publication of the Association of Public

Diplomacy Scholars (APDS) at the University of Southern California, with

support from the USC Center on Public Diplomacy at the Annenberg School, USC

Dana and Dornsife College of Letters, Arts and Sciences School of International

Relations, the Annenberg School for Communication and Journalism and USC

Annenberg Press.

Its unique mission is to provide a common forum for the views of both scholars

and practitioners from around the globe, in order to explore key concepts in the

study and practice of public diplomacy. Public Diplomacy Magazine is published

bi-annually, in print and on the web at www.publicdiplomacymagazine.org.

ABOUT apds

The USC Association of Public Diplomacy Scholars (APDS) is the nation's

first student-run organization in the field of public diplomacy. As an organization,

APDS seeks to promote the field of public diplomacy as a practice and study,

provide a forum for dialogue and interaction among practitioners of public

diplomacy and related fields in pursuit of professional development, and cultivate

fellowship and camaraderie among members. For more information please visit

www.pdscholars.org.

Winter 2014 | PD Magazine 3ABOUT

EDItorial board

Editor-in-chief

Shannon Haugh

Senior Editors

Lauren Madow, Managing Editor

Colin Hale, Layout Editor

Siyu Li, Marketing Editor

Syuzanna Petrosyan, Digital Editor

Emily Schatzle, Submissions Editor

Staff Editors

Soraya Ahyaudin, Jocelyn Coffin, Caitlin Dobson, Andres Guarnizo-Ospina

Bryony Inge, Maria Portela, Amanda Rodriguez

Production

Nick Salata

Chromatic Inc.

Faculty Advisory Board

Nicholas J. Cull, Director, Master of Public Diplomacy Program, USC

Jian ( Jay) Wang, Director, USC Center on Public Diplomacy

Philip Seib, Professor of Journalism, Public Diplomacy, and International Relations, USC

Ex-Officio Members

Robert English, Director, School of International Relations, USC

Sherine Badawi Walton, Deputy Director, USC Center on Public Diplomacy

Naomi Leight-Give'on, Assistant Director, Research & Publications, USC Center on Public Diplomacy

International Advisory Board

Sean Aday, Director, Institute for Public Diplomacy and Global Communication. Associate Professor of Media and Public

Affairs and International Affairs, George Washington University

Simon Anholt, Editor Emeritus, Journal of Place Branding and Public Diplomacy

Geoffrey Cowan, University Professor and Annenberg Family Chair in Communication Leadership, USC

Harris Diamond, CEO, Weber Shandwick Worldwide

Pamela Falk, Foreign Affairs Analyst and Resident UN Correspondent, CBS News

Kathy Fitzpatrick, Professor and Director of Graduate Studies in Public Relations, Quinnipiac University

Eytan Gilboa, Professor of International Communication, Bar-Ilan University

Howard Gillman, Provost and Executive Vice Chancellor, University of California, Irvine

Guy Golan, Associate Professor of Public Relations/Public Diplomacy, S.I. Newhouse School of Public Communications,

Syracuse University

Cari Guittard, Principal, Global Engagement Partners. Adjunct Faculty, Hult IBS and USC Annenberg School for

Communication and Journalism

Markos Kounalakis, President and Publisher Emeritus, Washington Monthly

William A. Rugh, US Foreign Service (Ret.)

Crocker Snow, Edward R. Murrow Center for Public Diplomacy, Tufts University

Nancy Snow, Professor of Communications, California State University, Fullerton; Adjunct Professor, IDC-Herzliya

Lauder School of Government, Diplomacy & Strategy; Adjunct Professor, USC Annenberg School for Communication and

Journalism

Abiodun Williams, President, Hague Institute for Global Justice

Ernest J. Wilson III, Dean and Walter Annenberg Chair in Communication, USC Annenberg School for Communication and

Journalism

Winter 2014 | PD Magazine 5ABOUT

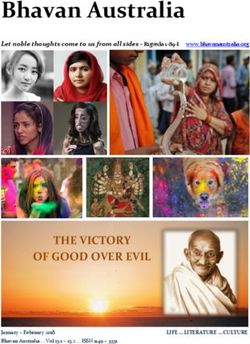

About The Cover

by Reagan Cook

The cover design ties together a collection of social and cultural symbols of international cuisine. Distinct regional

dishes are deconstructed into an arrangement of popular ingredients, handpicked from a global marketplace. This

collection of foodstuffs, displayed as elements of a potential meal, invites the viewer to engage with the unfinished

inventory, and to invent a recipe that fits their own individual creativity and taste.

Actors and Actions in a

Globalized World

VOLUME 4, FALL 2013

EXCHANGE

Available now at

Exchangediplomacy.com

A Syracuse University Publication The Journal of Public DiplomacyABOUT

Letter from the Editor

Issue 11, Winter 2014

Food brings people together. Throughout time, national cuisines have spread organically through

migration, trade routes, and globalization. Others have been deliberately packaged and delivered to

foreign audiences—both by state and non-state actors—as a means of expressing a country’s culture

and values. This form of cultural diplomacy, whether deliberate or unintentional, has been coined

“gastrodiplomacy.”

Gastrodiplomacy is the practice of sharing a country’s cultural heritage through food. Countries such

as South Korea, Peru, Thailand, and Malaysia have recognized the seductive qualities food can have,

and are leveraging this unique medium of cultural diplomacy to increase trade, economic investment,

and tourism, as well as to enhance soft power. Gastrodiplomacy offers foreign publics the opportunity

to engage with other cultures through food, often from a distance. This form of edible nation branding

is a growing trend in public diplomacy.

The Winter 2014 issue of Public Diplomacy Magazine contributes to the burgeoning scholarship on

gastrodiplomacy and its role in public diplomacy. Our feature and perspective pieces create a theoreti-

cal and practical framework for discussing gastrodiplomacy in multiple contexts. From the heated

debate over the ownership of dolma, to how food television travelogues play a role in national image,

to a prescriptive piece suggesting how to better measure and evaluate gastrodiplomacy programs. Our

case studies examine the gastrodiplomacy of Japan and Greece, while our interviews cover an Asian

night market in Los Angeles and elegant Indian food in Texas. In addition, Public Diplomacy Maga-

zine speaks with a U.S. Foreign Service Officer who specializes in gastrodiplomacy. We close this issue

with a book review on cultural icon and chef Eddie Huang’s new biography, Fresh Off The Boat, and

an endnote to introduce our next issue: “The Power of Non-State Actors.”

We would like to express our gratitude to the USC Center on Public Diplomacy, the Annenberg

Press, the USC Dornsife School of International Relations, and the USC Master of Public Diplo-

macy Program. Their continued support has helped make Public Diplomacy Magazine a leader in the

field of public diplomacy.

Last, but certainly not least, we would like to thank all our contributors for adding to the dialogue on

the emerging and expanding field of gastrodiplomacy.

We hope you enjoy this issue as much as we enjoyed putting it together. We encourage you to visit our

website (www.publicdiplomacymagazine.com) to view our online-only articles on gastrodiplomacy,

past issues, and to participate in the ongoing conversation on public diplomacy trends.

Shannon Haugh

Editor-in-Chief

Winter 2014 | PD Magazine 9contents

FEATURES

the state of gastrodiplomacy

11 paul rockower

from gastronationalism to gastrodiplomacy: reversing the

16 securitization of the dolma in the south caucasus

yelena osIpOva

CONFLICT CUISINE: TEACHING WAR THROUGH WASHINGTON'S ETHNIC

21 RESTAURANT SCENE

JOHANNA MENDELSON FORMAN

HEARTS, MINDS, AND STOMACHS: GASTRODIPLOMACY AND THE

27 POTENTIAL OF NATIONAL CUISINE IN CHANGING PUBLIC PERCEPTIONS

OF NATIONAL IMAGE

BRADEN RUDDY

rs pec t ives

pe

cooking up a conversation:

34 Gastrodiplomacy in contemporary public art

carly schmitt

WAR AND PEAS:

38 CULINARY CONFLICT RESOLUTION AS CITIZEN DIPLOMACY

SAM CHAPPLE-SOKOL

jamie oliver and the gastrodiplomacy of simulacra

44 francesco buscemi

Winter 2014 | PD Magazine 10in t e rvi e ws

on INDIAN FOOD IN THE DIASPORA

50 an interview with INDIAN RESTAURATEUR

ANITA JAISINGHANI

on the 626 taiwanese night market

52 an interview with founder jonny hwang

on gastrodiplomacy campaigns

54 an interview with u.s. foreign service officer mary jo pham

E ST UDI ES

CAS

most f(L)Avored nation Status: the gastrodiplomacy of

57 japan's global promotion of cuisine

theodore c. bestor

gastrodiplomacy: the case of the embassy of greece

61 zoe kosmidou

ok r e vi e w

bo

eddie huang's fresh off the boat: a memoir

65 jocelyn coffin

endnote

our summer 2014 issue:

67 the power of non-state actors

AN INTERVIEW WITH caroline bennett

communications director, amazon watch

Winter 2014 | PD Magazine 11FEAT UR ES

lomacy

st a t e o f gastrodip

the

wer

paul rocko lomacy: re

versing

a s t r od ip s

r o n a t io n alism to g t h e s o u t h caucasu

from gast t io n of the do

lma in

u r it iz a

the sec

Ova

yelena osIp H

AC H IN G W AR THROUG

UISINE: TE AURANT SCE

NE

CONFLICT C H N IC R ES T

N'S ET

WASHINGTO ORMAN

OHA N N A M ENDELSON F

J

INE

IN D S , A N D STOMACHS: IAL O F N AT IONAL CUIS

HEARTS, M OTENT

D IP LO M A C Y AND THE P S O F NATIONAL

IMAGE

GASTRO RC E P T IO N

G PUBLIC PE

IN CHANGIN

DY

BRADEN RUD

Winter 2014 | PD Magazine 12features

The state of gastrodiplomacy

By paul rockower

It is fitting that a magazine devoted to studying in- routes and awarding economic and political power

novations and trends in the field of public diplomacy has to those who handled cardamom, sugar, and coffee.

turned its focus on an increasingly popular forms of cul- Trade corridors such as the incense and spice route

tural diplomacy: gastrodiplomacy. through India into the Levant and the triangular

Public Diplomacy Magazine’s Summer 2009 issue on trade route spanning from Africa to the Caribbean

middle powers explored the behavior of middle powers and Europe laid the foundations for commerce and

and the contours of “middlepowermanship.” Articles in trade between modern nation-states. Indeed, these

this issue outlined how emerging countries are using pub- pathways encouraged discovery—weaving the cul-

lic diplomacy more prominently to break out of a crowded tural fabric of contemporary societies, tempering

field of competing nations. Meanwhile, the issue on cul- countless palates, and ultimately making way for

tural diplomacy looked at the various means that countries the globalization of taste and food culture.2

used to communicate their idiosyncratic cultures, ranging

from Japan’s use of Anime cartoons to conduct cultural di- There are few aspects as deeply or uniquely tied to cul-

plomacy, to how Nigeria made their culture a continental ture, history, or geography as cuisine. Food is a tangible tie

phenomenon, through the Nigerian film industry, Nol- to our respective histories, and serves as a medium to share

lywood. Both editions led the way towards a better un- our unique cultures.

derstanding of the field of public diplomacy, and helped The most effective cultural diplomacy takes national

create the space in which gastrodiplomacy is beginning to traits and cultures, distills them to their most tangible

be understood. forms, and communicates them to audiences abroad. Like

the successful use of music as cultural diplomacy, gastro-

THE GENESIS OF GASTRODIPLOMACY diplomacy also seeks to create a tangible, emotional and

Gastrodiplomacy represents one of the more exciting trans-rational connection.3 Both music and food work

trends in public diplomacy outreach. The subject of culi- to create an emotional and transcendent connection that

nary cultural diplomacy—how to use food to communi- can be felt even across language barriers. Gastrodiplomacy

cate culture in a public diplomacy context—began with seeks to create a more oblique emotional connection via

the application of academic theories of public diplomacy cultural diplomacy by using food as a medium for cultural

to case studies in the practice of the cultural diplomacy engagement. On this emotional connection, Rachel Wil-

craft. son comments:

Gastrodiplomacy was borne out of pinpointing case

studies in the field and connecting these cases to a broad- Because we experience food through our senses

er picture. An obscure word in an obscure article about (touch and sight, but especially taste and smell),

Thailand’s outreach to use its restaurants as forward cul- it possesses certain visceral, intimate, and emotion

tural outposts as a means to enhance its nation brand has qualities, and as a result we remember the food we

become a field of study within the expanding public di- eat and the sensations we felt while eating it. The

plomacy canon. The highlighting of disparate case stud- senses create a strong link between place and mem-

ies such as South Korea, Taiwan, Malaysia, Peru, among ory, and food serves as the material representation

others, led to patterns of practice; patterns led to broader of the experience.4

pictures of trends that proved an innovative means of con-

ducting successful cultural diplomacy.1 As such, gastrodiplomacy understands that you do not

Scholars of gastrodiplomacy have remained cognizant win hearts and minds through rational information, but

of the manner in which food has shaped both world his- rather through indirect emotional connections. Therefore,

tory and diplomatic interactions. Mary Jo Pham notes: a connection with audiences is made in tangible sensory

interactions as a means of indirect public diplomacy via

Throughout history, food has played a significant cultural connections. These ultimately help to shape long-

role in shaping the world, carving ancient trade term cultural perceptions in a manner that can be both

Winter 2014 | PD Magazine 13FEATURES

more effective and more indirect than targeted strategic of a country’s edible nation brand through the promotion

communications. of its culinary and cultural heritage. Gastrodiplomacy also

differs from food diplomacy, which involves the use of food

Theories of Gastrodiplomacy aid and food relief in a crisis or catastrophe. While food

In offering a theoretical construction for the field of diplomacy can aid a nation’s public diplomacy image, it is

gastrodiplomacy, it is necessary to define the framework. not a holistic use of cuisine as an avenue to communicate

This author highlights the characteristics of gastrodiplo- culture through public diplomacy.7

macy by comparing it to the practice of culinary diploma-

cy.5 In drawing distinctions to the field, the author notes Gastrodiplomacy 2.0: Poly- and Para-

the equivalence of diplomacy to public diplomacy, thusly Thus far, most gastrodiplomacy case studies come from

culinary diplomacy is to gastrodiplomacy.6 While diplo- states defined as “middle powers.” Middle powers are that

macy involves high-level communications from govern- fair class of states that neither reign on high as super-

ment to government, public diplomacy is the act of com- powers nor reside at the shallow end of the international

munication between governments and non-state actors power dynamic, but exist somewhere in the vast muddled

to foreign publics. Similarly, this author defines culinary middle of the global community.8

diplomacy as the use of food for diplomatic pursuits, in- Public Diplomacy Magazine’s issue on middle powers

cluding the proper use of cuisine amidst the overall formal explored the hallmarks and techniques of middle powers

diplomatic procedures. Thus, culinary diplomacy is the use and how they navigate the fight through the congested

of cuisine as a medium to enhance formal diplomacy in swathe of states in the middle of the pack in the global

official diplomatic functions such as visits by heads-of- system. In writing about the challenges facing middle

state, ambassadors, and other dignitaries. Culinary diplo- powers, Eytan Gilboa notes:

macy seeks to increase bilateral ties by strengthening re-

lationships through the use of Peoples around the world

food and dining experiences C Y S E E K S TO don’t know much about

as a means to engage visiting A S T R O D IP LOMA them, or worse, are holding

G N

dignitaries. T H E E D IBLE NATIO attitudes shaped by nega-

In comparison, gastrodi-

ENHANCE C U LT URAL tive stereotyping, hence

THROU G H

plomacy is a public diplomacy BRAND L IG H TS the need to capture atten-

attempt to communicate culi- L O M A C Y THAT HIGH tion and educate publics

D IP D

nary culture to foreign publics M O T E S AW ARENESS AN around the world. Since

in a fashion that is more dif- AND PRO NA T ION A L the resources of middle

fuse; it takes a wider focus to N D E RS TA N DING OF powers are limited, they

U WITH WIDE

influence the broader public C U LT UR E have to distinguish them-

audience rather than high-

CULINARY P U B L IC S. selves in certain attractive

FORE IG N

level elites. Gastrodiplomacy SWATHES OF areas.9

seeks to enhance the edible

nation brand through cul- States like Norway and Qatar focused on niche areas

tural diplomacy that highlights and promotes awareness like conflict resolution.10 Other middle power states, like

and understanding of national culinary culture with wide South Korea and Taiwan, have pushed to raise their na-

swathes of foreign publics. Moreover, as public diplomacy tion brands through the arts, music, and cuisine that make

in the age of globalization transcends state-to-public rela- their respective cultures unique. 11

tions and increasingly includes people-to-people engage- There are a number of difficulties that middle pow-

ment, gastrodiplomacy also transcends the realm of state- ers share in regards to their visibility issues on the global

to-public communication, and can also be found in forms stage. Middle powers face the fundamental challenge of

of citizen diplomacy. recognition in that global publics are either unaware of

Gastrodiplomacy should not be confused with interna- them, lack nuance or broad understanding, or hold nega-

tional public relations campaigns to promote various na- tive opinions—thus requiring the need to secure broader

tional food products. Simply promoting a food product of global attention. As culinary cultural diplomacy scholars

foreign origin does not mean that such promotions con- have learned through the emergence of the field, gastro-

stitute gastrodiplomacy. Rather, gastrodiplomacy remains diplomacy helps under-recognized nation brands increase

a more holistic approach to raise international awareness their cultural visibility through the projection of national

Winter 2014 | PD Magazine 14or regional cuisine. bul) in 1554, many centuries before Starbucks ever roasted

Yet it is not middle powers alone that are conducting a bean, the Turkish coffee campaign to educate audiences

gastrodiplomacy now. In 2012, the U.S. Department of on the history and flavor of Turkish coffee is smart gastro-

State embarked on its own culinary cultural diplomacy diplomacy.

campaign: the Diplomatic Culinary Partnership. The Dip- The Mobile Turkish Coffee Truck began its gastro-

lomatic Culinary Partnership includes equal parts culinary diplomacy outreach in 2012 by handing out free cups of

diplomacy—through the creation of an American Chef Turkish coffee up and down the East Coast of the United

Corps to help engage with the State Department in formal States, making stops in Washington, Baltimore, Philadel-

diplomatic functions—and gastrodiplomacy—through phia, New York, and Boston. The campaign handed out

sending out the American Chef Corps to embassies and cups of hot, sweet Turkish coffee with the grinds at the

consulates around the globe to conduct public diplomacy bottom, while an education component of the campaign

programs using food to engage with foreign publics. Addi- informed audiences about the historical connection of cof-

tionally, the program facilitates people-to-people cultural fee to Turkish culture. The campaign also included fun cul-

exchanges through the International Visitors Leadership tural diplomacy events, like fortune telling from the coffee

Program (IVLP) in chef exchanges in the United States. grounds in the cups.14 The Mobile Turkish Coffee Truck

If gastrodiplomacy conducted by middle powers was is conducting a second round of outreach, this time in Eu-

about using culinary cultural diplomacy to enhance the na- rope with stops in Holland, Belgium, and France.

tion brand, then gastrodiplomacy conducted by great pow- The Mobile Turkish Coffee Truck campaign in the U.S.

ers (the U.S., China), or culinary great powers like France, was conducted initially as a private venture with sponsor-

becomes more focused on illustrating and deepening nu- ship from Turkish-American businesses, the American-

ance in the edible nation brand. Turkish Association, the Turkish coffee company Kuruka-

Unlike many middle powers seeking to simply high- heveci Mehmet Efendi and Turkish Airlines—as well as

light their edible nation brand as a means to increase their some support from the Turkish Embassy to the U.S. and

visibility, the visibility of the U.S. is not in question. Rather, Consulates. The program’s success led to its second itera-

the strategy of the U.S. gastrodiplomacy campaign is to tion in Europe, launched in a more polylateral gastrodip-

create nuance and understanding so that the American lomatic fashion as a public/private initiative, including the

edible nation brand is seen as more than fast food dishes support of the representative offices of Turkey’s Ministry

and giant consumer chains, and includes a deeper under- of Culture and Tourism. Meanwhile, with the increased

standing of regional differences. Thus there is less a need prevalence of “paradiplomacy,” the phenomenon of sub-

to highlight the cuisine as a whole, but rather a need to state actors conducting their own international diplomatic

focus on the various regional and local dimensions that engagements, the necessity for these sub-state actors to

offer uniqueness. To this end, distinctive cuisines like Ca- also engage in public and cultural diplomacy has become

jun cuisine from New Orleans, or cuisine from the Pacific more pronounced.15 Already some sub-state actors are

Northwest, become the object of America’s gastrodiplo- conducting cultural diplomacy. In international forums

macy focus. like the Taipei Flora Expo in 2011, the State of Hawaii

As gastrodiplomacy moves forward as a field, we can conducted its own pavilion separate from that of the U.S.

expect two trends to become more prevalent: 1) gastro- Pavilion as a means to showcase Hawaii’s unique flora and

diplomacy polylateralism and; 2) gastrodiplomacy paradi- fauna. In addition, numerous sub-state regions conduct

plomacy. The term “polylateralism,” coined by diplomacy their own gastrodiplomacy at various food fairs to exhibit

scholar Geoffrey Wiseman, refers to the interaction of their unique culinary heritages.

states with non-state actors in the realm of diplomacy or The positive side of paradiplomacy engaging in gastro-

public diplomacy. 12 Gastrodiplomacy is one area of public diplomacy is that it makes cultural diplomacy significantly

and cultural diplomacy where states are starting to work more localized. To make public diplomacy more successful

with non-state actors through public/private initiatives, as a field, it remains incumbent on local communities to

such as the U.S. State Department’s Diplomatic Culinary understand their role in communicating culture. Creating

Partnership—a public/private initiative that includes a sub-state buy-in can ultimately strengthen gastrodiplo-

partnership with the nonprofit James Beard Foundation. 13 macy initiatives and make more local communities realize

Another initiative that has taken on elements of their role in public, cultural, and gastrodiplomacy.

polylateral gastrodiplomacy is the Mobile Turkish Coffee Just as gastrodiplomacy helps under-recognized na-

Truck. Given that the Ottoman Empire had its first coffee tions expand their brands and cultural visibility through

shop in the Sublime Porte’s capital Constantinople (Istan- the projection of national or regional cuisine, gastrodiplo-

Winter 2014 | PD Magazine 15FEATURES

macy by sub-state actors helps increase their own unique- MA: Harvard UP, 2004. Print.

ness and brand visibility in a similarly cluttered landscape. 4. Wilson, Rachel. "Cocina Peruana Para El Mun-

As more sub-state actors are starting to conduct paradi- do: Gastrodiplomacy, the Culinary Nation Brand, and

plomacy and seeking to strengthen their brand, we can the Context of National Cuisine in Peru." Exchange: The

likely expect these actors to turn to gastrodiplomacy as a Journal of Public Diplomacy 2.2 (2011): Web.

means to highlight cultural uniqueness of their respective 5. For more on the history of culinary diplomacy,

sub-state brands. see: Chapple-Sokol, Sam. "Culinary Diplomacy: Breaking

One additional trend that is likely to become more Breads to Win Hearts and Minds."The Hague Journal of

common is the use of gastrodiplomacy by non-state ac- Diplomacy 8 (2013): Web.

tors as a means to conduct public diplomacy and people- 6. For more on difference between gastrodiplomacy

to-people diplomacy. As gastrodiplomacy becomes a more and culinary diplomacy, see Rockower, Paul. "Recipes for

recognized field within public diplomacy, there stands a Gastrodiplomacy." Place Branding and Public Diplomacy

likelihood of more non-state actors using gastrodiplomacy 8 (2012): Print.

to facilitate people-to-people diplomacy related to issues 7. Ibid.

of conflict. 8. Cooper, Andrew Fenton, Richard A. Higgott,

and Kim Richard. Nossal. Relocating Middle Powers:

Conclusion Australia and Canada in a Changing World Order. Van-

Representing one of the newer trends within public di- couver: UBC, 1993. Print.

plomacy, gastrodiplomacy has come a long way in a short 9. Gilboa, Eytan. "The Public Diplomacy of Middle

time. In just a few years, the field of gastrodiplomacy has Powers." Public Diplomacy Magazine 1.2 (2009): Print.

gone from obscurity to an issue of discussion and debate in 10. On Norway, see: Henrikson, Alan, “Niche Di-

academic journals, as well as the subject of its own confer- plomacy in the World Public Arena: The Global 'Corners'

ence at American University.16 Gastrodiplomacy embod- of Canada and Norway,” in The New Public Diplomacy.

ies a powerful medium of nonverbal communication to New York: Palgrave, 2005. Print.; On Qatar, see: Rock-

connect disparate audiences, and thusly is a dynamic new ower Paul, “Qatar's Public Diplomacy,” unpublished paper

tactic in the practice and conduct of public and cultural (2008): Web.

diplomacy. 11. On Korea, see: Jang, Gunjoo, and Won K. Paik.

As more states engage in gastrodiplomacy, new trends "Korean Wave as Tool for Korea's New Cultural Diplo-

will emerge that will shape a new set of best practices in macy." Advances in Applied Sociology 2.3 (2012): n. pag.

the field, such as increased polylateral partnerships and Print. ; Rockower, Paul. "Projecting Taiwan." Issues and

gastrodiplomacy paradiplomacy, as well as non-state actors Studies 47.1 (2011): Print.

turning to gastrodiplomacy as a means to foster people-to- 12. Wiseman, Geoffrey, “’Polylateralism’ and New

people connections. Modes of Global Dialogue” in Diplomacy edited by Cris-

ter Jonsson and Robert Langhorne, 36-57. Sage: London,

2004. Print.

13. Rockower, Paul. "Setting the Table for Diplo-

REFERENCES AND NOTES macy." USC Center on Public Diplomacy. 21 Sept. 2012.

1. For South Korea, see Pham, Mary Jo. "Food as Web.

Communication: A Case Study of South Korea's Gastro- 14. Werman, Marco. "Sharing Turkey's Centuries-

diplomacy." Journal of International Service 22.1 (2013): Old Coffee Tradition with a Food Truck."Public Radio

Web.; for Taiwan, see Rockower, Paul. "Projecting Tai- International's The World. 11 May 2012. Web.

wan." Issues and Studies 47.1 (2011): Print.; For Peru, see 15. Wolff, Steffen, “Paradiplomacy,” Bologna Center

Wilson, Rachel. "Cocina Peruana Para El Mundo: Gastro- Journal of International Affairs 16 (2010): Web.; Tavares,

diplomacy, the Culinary Nation Brand, and the Context Rodrigo, “Foreign Policy Goes Local,” Foreign Affairs,

of National Cuisine in Peru." Exchange: The Journal of (2013): Print.

Public Diplomacy 2.2 (2011): Web. 16. Pham, Mary Jo “Food + Diplomacy= Gastro-

2. Pham, Mary Jo. "Food as Communication: A diplomacy,” The Diplomatist (2013): Web.; Wallin, Mat-

Case Study of South Korea's Gastrodiplomacy." Journal of thew “Gastrodiplomacy— ‘Reaching Hearts and Minds

International Service 22.1 (2013): Web. through Stomachs,’” American Security Project (2013):

3. Von, Eschen Penny M. Satchmo Blows Up the Web.

World: Jazz Ambassadors Play the Cold War. Cambridge,

Winter 2014 | PD Magazine 16wer

paul rocko

Paul S. Rockower is a graduate of the USC Master

of Public Diplomacy program. He has worked with

numerous foreign ministries to conduct public diplomacy,

including Israel, India, Taiwan and the United States.

Rockower is the Executive Director of Levantine Public

Diplomacy, an independent public and cultural diplomacy

organization.

Photo: Paul Rockower

Winter 2014 | PD Magazine 17FEATURES

from gastronationalism to gastrodiplomacy:

reversing the securitization of the dolma in

the south caucAsus

By yelena osipova

“I don’t think the war strategy has ever worked for humanity, but after thousands and thousands and thousands of

years of earth controlled by humans, war still seems to be the answer? I hope one day, food will be the answer.”

– José Andrés1

Dolma is a simple, albeit time-consuming, dish to pre- is no exception.2 As a basic necessity for sustenance and

pare. Grains or ground meat, rice, tomato paste, spices, survival, food provides “links between social actors and

and veggies (to stuff ) or leaves (to wrap) are usually all their cultural pasts, shared bonds of familial or religious

there is to it. It comes in all shapes, colors, and sizes: from identity, and narratives of organizational identity.”3 Culi-

stuffed eggplants, tomatoes, peppers, and zucchini to nary culture also recreates national myths and memories,4

carefully wrapped grape or cabbage leaves. Dolma can be functions as a language to articulate “notions of inclusion

made with beef or lamb, and there is a vegetarian option, and exclusion, of national pride and xenophobia,”5 and,

too, with lentils, peas, or chickpeas instead. This tasty mor- therefore, acts as “a boundary-marker between one iden-

sel, which has joined the list of globalized “ethnic” foods tity and another.”6

(usually marketed as Mediterranean/Middle Eastern in In a rapidly globalizing world where claims of au-

the West), is characteristic of many traditional cuisines in thenticity and exoticism provide a competitive edge for

the area that extends from Central Asia to the Balkans, goods on the global market,

and from North Africa to Rus- the importance of national

sia. The various permutations n s a n d signifiers for food products

traditio

of the dolma recipe reflect its culinary a nthe m s has increased further.7 Mi-

transformation and adapta- ju st l ik e chaela DeSoucey has coined

tion by various peoples who foodways, o n g t h e a term for the combination of

are am

have inhabited that vast terri- or flags, c k s this phenomenon with that of

tory over millennia. m e n ta l b uilding blo identity. 8 Gastronationalism,

funda

The variety and pervasive- l identity. she suggests, describes the

ness of dolma have led to dis- of nationa “use of food production, dis-

putes among countries of the tribution, and consumption to

region regarding the origins create and sustain the emotive power of national attach-

of the dish. Where did the dolma originate and whose ment” that is later used in the production and marketing

“national cuisine” does it represent? This paper examines of food.9 Yet, much like other national symbols that rarely

the food fight raging between Armenia and Azerbaijan follow the strict rules of separation and the neat lines of

– two nations in the South Caucasus that fought a bitter political borders, international disputes over the “owner-

war in the 1990s and are still in a frozen conflict with each ship” of certain foods and dishes are increasingly common.

other. It posits that despite the intensity of gastronational- Some of the more prominent of these cases include the

ism in the region, gastrodiplomacy can serve as an addi- fights over hummus (as well as tabouleh, labne, or falafel,

tional tool for achieving and maintaining peace between to name but a few) between Israel and Lebanon,10 kimchi

the Armenians and the Azerbaijanis. between China and South Korea,11 and “Turkish” delight

between Cyprus and Turkey.12 There is certainly an eco-

GASTRONATIONALISM nomic justification to patenting foods as one’s national

Culinary traditions and foodways, just like anthems dish, as it can help promote sales and provide exclusive

or flags, are among the fundamental building blocks of access to markets. However, underlying most if not all of

national identity. Nations define themselves through these fights is also a fundamental contestation over iden-

things that give group members shared experiences and tity linked to territorial and historical disputes.

generate solidarity. Food, as a material artifact of culture,

Winter 2014 | PD Magazine 18Making Dolma a Matter of Armenian cuisine “has served as a donor” to neighboring

National Security countries and that at its root, the cuisine of the region is

Conflicts regarding the origins of various cultural actually Armenian. As evidence to support their claims,

artifacts in the Southern Caucasus have been simmer- some of the chefs participating in the Festival claimed

ing for years over issues like carpet patterns, winemak- to have taken their dolma recipes from ancient archives,

ing, horses, musical instruments, and dog breeds, to name and some from cuneiform records dating back to the 8th

but a few. The culinary controversies gained prominence century BC found in the Erebuni fortress (on territory of

in late 2011, when UNESCO decided to add keshkek, modern-day Yerevan), the capital of the Urartian Kind-

an Anatolian stew made with chicken and wheat berries, gom at the time.19 To prove their dedication to the dish

to its list of “Intangible Heritage” on behalf of Turkey.13 and taking inspiration from their Mediterranean counter-

Armenians, who call the same dish harisa and consider parts, who had engaged in bitter competitions over the

it to be their own, were outraged at the decision and set biggest plate of hummus and the largest piece of “Turkish”

out to find ethnographic evidence to overturn it.14 That delight, participants of the 2013 Festival competed over

served as a catalyst for the mobilization of several NGOs the longest dolma in an attempt to set a world record, the

and youth groups in the country, which started calling for winner being a 25-foot-long “behemoth.”20

greater government involvement in reclaiming Armenia’s Another campaign aimed at primordializing the dol-

intangible heritage, as well as advocating for a more coor- ma was an attempt to reconceptualize the etymology of

dinated effort to preserve and promote Armenia’s culinary the name, playing on the difference between the spell-

traditions.15 ing – “dolma” and “tolma” – to suggest that dolma means

Those behind the Armenian initiative construed this “stuffed,” while tolma means “wrapped” – that is, in grape

effort in terms of a greater struggle for cultural survival leaves. A prominent restaurant chef even went so far as to

and national security. As historian and analyst Ruben Na- claim that “Tolma is a word that consists of two Urartu

hatakyan stated in an interview at the time: language roots, ‘toli’ and ‘ma,’ which mean ‘grape leave’ and

‘wrapped’.”21 However, it is important to note that the

We are in the middle of the war of civilizations root itself is Turkic and “dolma” in Turkish means stuffed

[…]. [O]ur not so friendly neighbors are trying to or full of. The word for wrapped, on the other hand, is

rob the entire Armenian highland, both the terri- “sarma,” which is in fact what wrapped grape leaves are

tories that are part of the Armenian Republic and called in Turkey and some of the Balkan countries (but,

those that aren’t. […] A neighbor will always take surprisingly, not in Azeri, which has Turkic roots, too).

what’s yours if you don’t protect it; and today we The difference between the spelling of “dolma” and

are dealing with neighbors who are acting upon a “tolma” can be attributed to the phonological change as

well-thought strategy, and we keep failing to resist a result of the influence of the Russian language in coun-

their plots.16 tries like Armenia or Azerbaijan. This is demonstrated

with the example in Armenian, where there is a differ-

The activists involved in this effort have promised ar- ence between the pronunciation of the first letter, which

ticles and films on various Armenian traditional dishes, is harder (“d”) in Western Armenian (spoken in Anatolia

international campaigns that raise awareness and get rec- and by most of the current Diaspora) and softer (“t”) in

ognition, as well as various festivals to engage the public Eastern Armenian (of Armenia proper, Iran. and the For-

at large. mer Soviet Union). All the while the spelling of the word

Amidst this fight, dolma seems to have gained a spe- remains identical.

cial status. For the past three years, the Development and These claims enraged the Azerbaijanis who accused

Preservation of Armenian Culinary Traditions (DPACT) Armenians of culinary plagiarism, and elevated the issue

NGO has overseen the organization of an annual Dolma to a matter of national security. As a result, the Ministry

Festival as a way of “disproving the wrong opinions that of National Security established a National Cuisine Cen-

tolma [sic] has Turkish roots.”17 At the first festival, head ter – a watchdog of sorts – charged with “exposing the

of DPACT Sedrak Mamulyan noted that the choice of Armenian lies” about the dishes stolen from Azerbaijani

location for the festival – Sardarapat, a battlefield of ma- cuisine.22 Furthermore, the Ministry of National Secu-

jor historical significance – was not accidental, since Ar- rity, along with the Ministry of Culture and the national

menians need to develop their “self-defense instinct” in Copyright Agency, has been actively involved in publicity

the culinary world, just as they defended their homeland campaigns, including film screenings and publications on

during the battle of 1918.18 He went on to say that the ethnographic origins and etymology.23 And to highlight

Winter 2014 | PD Magazine 19FEATURES

the significance of dolma itself, in 2012 President Ilham trust.30 Although these fundamental conditions might

Aliyev went as far as to declare it an “Azeri national dish,” be absent in the current Armenian-Azerbaijani relations,

effectively denying the claims laid to it by all other na- given that other channels of resolution to the conflict do

tions, including Turkey.24 not seem to be working, food and, more specifically, dolma

diplomacy should be given a chance.

Gastrodiplomacy: An Answer?

The dolma dispute is part of the larger conflict between Moving Forward: Can Enemies Become

the two nations, including that over Nagorno Karabakh, Friends?

which remains unresolved. Writing about the hummus Both Armenia and Azerbaijan have been calling for

wars, Ari Ariel noted that in circumstances of conflict, the need to enhance their respective public diplomacy

those involved in the preparation and the sale of the food strategies abroad, in order to garner more international

on both sides are seen as representatives of their respective support for their stances on the conflict.31 Despite being

communities: “If food and national identity are univer- few in number, there have also been calls for, and attempts

sally linked, here political dispute and warfare produce a at more engagement with each other through public di-

rhetoric of violence that transforms cooks into combat- plomacy.32 Gastrodiplomacy can be a potent tool in this

ants.”25 However, beyond just being an extension of the latter process, demonstrating commonality and creating a

conflict, food can also bring the two sides together – as shared, safe space where a conversation can begin. Some

long as they accept its shared origin. And this is where projects – such as the Azerbaijani Cuisine Day organized

diplomacy of food can play a major role. in Nagorno Karabakh by the Helsinki Initiative NGO in

Sam Chapple-Sokol suggests using “culinary diplo- 2007 – have met with suc-

macy […] as an instrument cess, because despite politics

to create cross-cultural un- b e ing an and hostility, both nations

derstanding in the hope of e y o n d just still enjoy each other’s food.33

b t,

improving interactions and n o f t h e conflic Other suggested projects can

cooperation.”26 Paul Rock-

extensio g t h e t wo include – but are not limited

also b r in

ower, however, highlights the food can o n g a s to – joint culinary festivals,

need to differentiate between e s t o g e t her - as l cooking competitions with

sid .

“culinary diplomacy,” which e p t its s hared origin teams from both nations,

he conceptualizes in terms they acc and cooking shows featuring

of high diplomacy between chefs from both sides cooking

representatives of certain na- common dishes together.

tions and communities, and “gastrodiplomacy,” which is Over time, such activities and projects can bring about

much broader and includes engagement with the public the “right conditions” for Contact Hypothesis outlined

at large.27 Gastrodiplomacy – “the act of winning hearts by Allport. Given the separation between the Armenians

and minds through stomachs” – introduces foreign culture and the Azerbaijanis, and their lack of knowledge or un-

through familiar access points such as the sense of taste, derstanding of each other, exploring common traditional

and seeks to establish an emotional connection through dishes can help establish the notion that the two sides

food.28 In terms of conflict resolution, gastrodiplomacy share quite a bit in common – whether culturally, socially,

can serve as a medium for Contact Hypothesis, a theory or historically. Furthermore, engaging in joint projects

suggesting that hostility between groups is “fed by un- where both sides have to cooperate to achieve a superor-

familiarity and separation.”29 According to the theory, dinate goal – such as in case of competitions or festivals

greater contact between the groups, under the right con- – can help the participants overcome their distrust, which

ditions, can bring an end to the conflict by promoting can then be used to build further dialogue. In this sense,

more positive intergroup attitudes. Gordon Allport who the effort has high acquaintance potential and promotes

developed the Hypothesis identified four major condi- cooperative interactions. Equal status is another impor-

tions necessary for success: support of respective authori- tant condition, since it can disconfirm negative expecta-

ties who would foster the social norms that favor accep- tions about the other.34 Sharing a meal – such a dolma

tance and ties, promotion of close contact between the – which both sides would prepare together, could establish

members of the two groups, equal status between them, equality through a common sensory experience, as well as

and the presence of cooperative interdependence between provide an atmosphere of intimacy where a constructive

the groups to ensure mutual reliance and cultivation of conversation can begin.35

Winter 2014 | PD Magazine 20Finally, and perhaps most importantly, Allport sug- understanding, one that goes beyond mere lines that de-

gests that social and institutional support is vital for the note purported national borders on maps. Foodways are

success of the process, since without a conducive environ- constructed over time through constant interaction and

ment of tolerance and acceptance, no dialogue can take communication with others, meshing, reshaping, and of-

place and no achievements can be sustained. It is, there- ten simply borrowing from each other. Labeling foods

fore, important to ensure state support for such conciliato- – especially ones that are popular around the region and

ry measures. Nareg Seferian, an independent analyst and more recently, around the world – as “Armenian” or “Azer-

a cosmopolite currently based in Armenia, raises similar baijani,” “Lebanese” or “Israeli,” therefore, reflects a very

concerns. Seferian says that the Nagorno Karabakh issue simplistic understanding of the world, pandering to base

is fundamentally a political one, where lives and territory nationalistic sentiments and emotions, for the purposes

are at stake.36 Therefore, according to him, only a politi- of achieving certain political ends. Gastrodiplomacy can

cal solution – peace through diplomacy – can be a lasting help step beyond this worldview towards the higher goal

one. “In order to maintain an atmosphere of neighbor- of cooperation, demonstrating that differences are not

liness afterwards, though, I would say that food, among truly as great or tangible as they might have been initially

other things, can be used as a common marker. That can presented. After all, as Krikorian notes, “Does it actu-

only be an afterthought, however.” Onnik Krikorian, a ally matter [who “owns” the dolma], especially when the

British freelance reporter and photojournalist based in origins are hard to prove and the whole point is to eat it

Tbilisi, Georgia, expresses a similar sentiment: “Traveling anyway? […] I've seen Armenians and Azerbaijanis share

around Georgia, I’ve seen ethnic Armenians and Azeris tables numerous times. The toasts are nearly always to

share tables full of dolma and other dishes without men- peace.”

tion of 'whose' they might be. But that's probably because

they're spared the near constant propaganda in circulation

in Armenia and Azerbaijan.”37 In short, unless the neces-

sary conditions highlighted by Allport are present, success REFERENCES AND NOTES

will be questionable, at best. Yet if the conflict is somehow 1. In Chapple-Sokol, Sam. "Culinary Diplomacy:

resolved, gastrodiplomacy – along with other forms of Breaking Bread to Win Hearts and Minds." The Hague

public and cultural diplomacy – can be a potent medium Journal of Diplomacy 8.2 (2013): 161-83. Print.

for bringing the two nations together. 2. Palmer, Catherine. "From Theory to Practice.

Experiencing the Nation in Everyday Life." Journal of

Conclusion Material Culture 3.2 (1998): 175-99. Print. See also Bell,

By no means is gastrodiplomacy suggested here as a David, and Gill Valentine, eds. Consuming Geographies:

solution in itself, especially given the context of a seem- We Are Where We Eat. New York: Routledge, 1997.

ingly intractable conflict driven by nationalism and the Print.

propaganda of hate on both sides. However, it can serve 3. DeSoucey, Michaela. "Gastronationalism: Food

as a tool for conflict resolution in two ways. Firstly, it can Traditions and Authenticity Politics in the European

begin a peace from below, starting a movement towards a Union." American Sociological Review 75.3 (2010): 432–

constructive conversation during which some of the other 55. Print.

more difficult issues and fundamental disagreements can 4. Cho, Hong Sik. "Food and Nationalism—Kim-

be negotiated. Gastrodiplomacy can provide the partici- chi and Korean National Identity." The Korean Journal of

pants with an inherent understanding that some things International Relations 46.5 (2006): 207-29. Print.

are, have been, and should probably be shared: that col- 5. Bell, David, and Gill Valentine, eds. Consuming

laboration and cooperation, and not exclusion or hostil- Geographies: We Are Where We Eat. New York: Rout-

ity, are the answer to the wider conflict. Secondly, gastro- ledge, 1997: 168. Print.

diplomacy can follow a peace from above – one agreed 6. Palmer, Catherine. "From Theory to Practice.

to on the high, diplomatic level between negotiators and Experiencing the Nation in Everyday Life." Journal of

politicians – to establish a friendlier atmosphere on both Material Culture 3.2 (1998): 188. Print.

sides of the border and create the conditions for lasting 7. Ferguson, Priscilla Parkhurst. "Culinary Nation-

peace. In both cases, however, gastrodiplomacy can only alism." Gastronomica: The Journal of Food and Culture

play a supplementary role. There must be mutual will and 10.1 (2010): 102-09. Print.

recognition for any of it to work. 8. DeSoucey, Michaela. "Gastronationalism: Food

Cuisine, just like identity, requires a more complex Traditions and Authenticity Politics in the European

Winter 2014 | PD Magazine 21FEATURES

Union." American Sociological Review 75.3 (2010): 432– erty 17 January . 17 2013. Web. 18 October. 18 2013

55. Print. 25. Ariel, Ari. "The Hummus Wars." Gastronomica:

9. DeSoucey, Michaela. "Gastronationalism." The The Journal of Food and Culture 12.1 (2012): 34. Print.

Wiley-Blackwell Encyclopedia of Globalization. Ed. 26. Chapple-Sokol, Sam. "Culinary Diplomacy:

Ritzer, George. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons, 2012. Breaking Bread to Win Hearts and Minds." The Hague

Print. Journal of Diplomacy 8.2 (2013): 162. Print.

10. Ariel, Ari. "The Hummus Wars." Gastronomi- 27. Rockower, Paul S. "Recipes for Gastrodiplo-

ca: The Journal of Food and Culture 12.1 (2012): 34-42. macy." Place Branding and Public Diplomacy 8.3 (2012):

Print. 235–46. Print.

11. Pham, Mary Jo A. "Food as Communication: A 28. Ibid.

Case Study of South Korea's Gastrodiplomacy." Journal 29. Brewer, Marilynn B., and Samuel L. Gaertner.

of International Service 22.1 (2013): 1-22. Print. "Toward Reduction of Prejudice: Intergroup Contact and

12. Hadjicostis, Menelaos. "Turkey Less Than De- Social Categorization." Blackwell Handbook of Social

lighted over Candy Trademark Move." The Houston Psychology: Intergroup Processes. Eds. Brown, Rupert

Chronicle 14 December. 14 2007. Web. 20 October. 20 and Samuel L. Gaertner. Oxford, UK: Blackwell Publish-

2013. ers, 2008. 452. Print.

13. Schleifer, Yigal. "UNESCO Decision Helps 30. Ibid.

Start a Turkish-Armenian Food Fight." EurasiaNet 5 31. Ismailzade, Fariz. "Azerbaijan Boosts Its Public

December. 5 2011. Web. 18 October. 18 2013. Diplomacy Efforts." Eurasia Daily Monitor. Jamestown

14. Schleifer, Yigal. "Armenia: More Fallout from Foundation 12 August. 12 2011. Web. 22 October . 22

UNESCO's Culinary Heritage Decision." EurasiaNet 7 2013. Haratunian, Jirair. "Gap: Armenia Lacks a Public

December. 7 2011. Web. 20 October. 20 2013. Diplomacy Strategy." ArmeniaNow 5 May 5 2008. Web.

15. ArmeniaNow. "National Heritage: Initiative 22 October. 22 2013

Group Forms in Armenia to Protect Non-Material Cul- 32. Shirinyan, Anahit. "Karabakh Settlement: In

tural Values." ArmeniaNow 5 April. 5 2012. Web. 20 Oc- Need of Public Diplomacy." Caucasus Edition 12 April .

tober. 20 2013. 12 2010. Web. 22 October . 22 2013. Musayelyan, Lusine.

16. Ibid. "Appetites Trump Politics." Caucasian Circle of Peace

17. Mkrtchyan, Gayane. "Tolma Festival: Tradi- Journalism 14 December . 14 2011. Web. 20 October. 20

tional Armenian Ways of Wrapping Meat in Leaves Pre- 2013.

sented Anew." ArmeniaNow 15 July 15 2011. Web. 18 33. Schleifer, Yigal. "In Disputed Nagorno-Kara-

October. 18 2013. bakh, Locals Still Pine after Azeri Food." EurasiaNet 22

18. Ibid. December . 22 2011. Web. 21 October . 21 2013.

19. Ibid. 34. Ibid.

20. Kebabistan. "Armenia: The Dolma Battle Goes 35. See, for example, Shah, Riddhi. "Culinary Di-

On." EurasiaNet 12 July 12 2013. Web. 18 October. 18 plomacy at the Axis of Evil Cafe." Salon 9 June 9 2010.

2013. Web. 20 October . 20 2013.

21. Mkrtchyan, Gayane. "Tolma Festival: Tradi- 36. Author’s correspondence with Seferian, Octo-

tional Armenian Ways of Wrapping Meat in Leaves Pre- ber. 2013.

sented Anew." ArmeniaNow 15 July 15 2011. Web. 18 37. Author’s correspondence with Krikorian, Octo-

October. 18 2013. ber. 2013.

22. DAY.AZ. "Russia’s Large Food Company La-

bels Azerbaijani Dish as Armenian." Today.Az 16 July 16 ova

ip

2009. Web. 22 October. 22 2013. See also O'Connor, Coi- yelena os

lin. "Food Fight Rages in the Caucasus." Transmissions.

Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty 17 January . 17 2013. Yelena Osipova is a Ph.D. Candidate in International

Web. 18 October. 18 2013. Relations at the School of International Service, Ameri-

23. ANN. "Film About Armenian Plagiarism of can University, in Washington, DC. Her research focuses

Azerbaijani Cuisine Presented in Baku." ANN.AZ 16 on public diplomacy and cross-cultural communication,

January. 16 2013. Web. 20 October. 20 2013. specifically in Eurasia. She is currently working on her

24. O'Connor, Coilin. "Food Fight Rages in the dissertation on the Russian discourse on soft power and

Caucasus." Transmissions. Radio Free Europe/Radio Lib- public diplomacy.

Winter 2014 | PD Magazine 22CONFLICT CUISINE: TEACHING WAR THROUGH

WASHINGTON'S ETHNIC RESTAURANT SCENE

By JOHANNA MENDELSON FORMAN

WITH SAM CHAPPLE-SOKOL

It is a Washington cliché: you can always tell where in of the culinary legacy of these wars as manifested by the

the world there is a conflict by the new ethnic restaurants Washington restaurants. By using readings about those

that open. From Vietnam to the Russian invasion of Af- wars, and utilizing other media, I hope to bring together

ghanistan, to the Central American wars, to the civil war the classroom and the communities who still use their

in Ethiopia, diasporas have come to this city in search of cooking to retain a link with their former homelands.

freedom. With them, they bring a sense of keeping the To integrate the study of conflict with food, I asked

culinary culture of their country alive in the numerous food researcher Sam Chapple-Sokol to help identify

eateries that landscape Washington’s suburbs. four local ethnic restaurants where the owners would be

Teaching about war and conflict requires an ability to willing to share their cuisine, but also to share with us a

analyze current global upheaval. Yet if there is one thing background on particular dishes that were representative

I have observed from my experience as a policy expert of their national heritage. When I first discussed this idea

on conflicts and transitions, and my academic research with other colleagues who teach courses on war and peace

and years of teaching about weak and fragile states, it is they encouraged me to create this seminar. American

that students today lack a basic knowledge of 20th cen- U n i v e r s i t y has always had a mandate to

tury conflicts. It seems to me that, too integrate its global education

often, events before Septem- e s mission with the local com-

ber 11, 2001, are considered r v e y o r s of cuisin munity. This course is consid-

The p u

too far removed and thus ie s in c o nflict ered one of the most tangible

ntr

forgotten. Wars like Vietnam from cou a ways that we can connect with

or the Russian invasion of e t h e ir food as our neighbors to advance our

can u s

Afghanistan are considered c o m m u nicating understanding about the local

means of

ancient history. And even o m e s t ic impact of conflict.

re to U.S. d

the post-Cold War conflicts their cultu their In the next few pages,

in the Balkans or in West s a b o ut we describe our approach to

audienc e

Africa are not easily recalled. u l a r ly how teaching war and conflict.

part ic

These gaps in understand- culture, n Such a course serves as a pow-

ing about past events make it a f f ec t e d the civilia erful tool for interdisciplinary

war has r e n ow in

harder to see the connections s w h o a understanding of the nexus of

between what is happening in population international events and the

Syria or Iraq and what hap- e x il e . community. Conflict cuisines

pened in Vietnam or Ethio- are also a wonderful example

pia. Wars today are not waged of what has been described by political scientist

by regular armies, but more often by irregular forces Abraham Lowenthal as the "intermestic, referring to is-

that change the dynamics of fighting. Cities are the new sues that have both international and domestic facets."2

battlefields. Civilians, not soldiers, are the victims of to- The purveyors of cuisines from countries in conflict can

day’s conflicts. use their food as a means of communicating to U.S. do-

Through this course, Conflict Cuisines: An Introduction mestic audiences about their culture, particularly how war

to War and Peace through Washington’s Ethnic Restaurant has affected the civilian populations who are now in exile.

Scene, a seminar at the School of International Service This type of connection may be an unintended conse-

(SIS) at the American University in Washington, D.C., quence of any given conflict, but it does have a didactic

I hope to explore those events that have shaped modern element that can help build support and understanding

conflict, while also demonstrating how the nature of war- about other people and other countries.

fare has shifted in the last sixty years.1 This is a first–com- While focused on the Washington, D.C. area, we also

bining a serious course about conflicts with an exploration hope that the course format can serve as a template for

Winter 2014 | PD Magazine 23You can also read