ORIGINAL ARTICLE Should snacks be recommended in obesity treatment? a 1-year randomized clinical trial - Nature

←

→

Page content transcription

If your browser does not render page correctly, please read the page content below

European Journal of Clinical Nutrition (2008) 62, 1308–1317

& 2008 Macmillan Publishers Limited All rights reserved 0954-3007/08 $32.00

www.nature.com/ejcn

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Should snacks be recommended in obesity

treatment? a 1-year randomized clinical trial

H Bertéus Forslund1, S Klingström2, H Hagberg3, M Löndahl2, JS Torgerson4 and AK Lindroos1,5

1

Department of Metabolism and Cardiovascular Research, Sahlgrenska Academy, Göteborg University, Göteborg, Sweden;

2

Helsingborgs Lasarett, Helsingborg, Sweden; 3Skaraborgs Sjukhus, Skövde, Sweden; 4Norra Älvsborgs Länssjukhus, Trollhättan,

Sweden and 5MRC Human Nutrition Research, Cambridge, UK

Objective: To study the effect to recommend no snacks vs three snacks per day on 1-year weight loss. The hypothesis was that it

is easier to control energy intake and lose weight if snacks in between meals are omitted.

Subjects/Method: In total 140 patients (36 men, 104 women), aged 18–60 years and body mass index430 kg/m2 were

randomized and 93 patients (27 men, 66 women) completed the study. A 1-year randomized intervention trial was conducted

with two treatment arms with different eating frequencies; 3 meals/day (3M) or 3 meals and 3 snacks/day (3 þ 3M). The patients

received regular and individualized counseling by dieticians. Information on eating patterns, dietary intake, weight and

metabolic variables was collected at baseline and after 1 year.

Results: Over 1 year the 3M group reported a decrease in the number of snacks whereas the 3 þ 3M group reported an increase

(1.1 vs þ 0.4 snacks/day, respectively, Po0.0001). Both groups decreased energy intake and E% (energy percent) fat and

increased E% protein and fiber intake but there was no differences between the groups. Both groups lost weight, but there was

no significant difference in weight loss after 1 year of treatment (3M vs 3 þ 3M ¼ 4.176.1 vs 5.979.4 kg; P ¼ 0.31). Changes

in metabolic variables did not differ between the groups, except for high-density lipoprotein that increased in the 3M group but

not in 3 þ 3M group (Po0.033 for group difference).

Conclusion: Recommending snacks or not between meals does not influence 1-year weight loss.

European Journal of Clinical Nutrition (2008) 62, 1308–1317; doi:10.1038/sj.ejcn.1602860; published online 15 August 2007

Keywords: snacking; eating patterns; obesity; recommendations; adherence; weight loss

Introduction patterns on energy balance and weight loss (Drummond et al.,

1996; Kirk, 2000; Booth et al., 2004; Jebb, 2005).

Although the importance of regular mealtimes is consistently Yet, snacking may play a role in obesity management as

advocated in obesity treatment (Wing et al., 1996; NIH, 1998; snacking may influence energy intake and thus body weight.

DPP, 2002; SBU, 2002; Wadden and Stunkard, 2002; Elfhag Spreading the energy load over the day by including several

and Rossner, 2005), the role of eating frequency in obesity is snacks may reduce appetite (Speechly et al., 1999) and as a

unclear (WHO, 2003) and there is no clear evidence of the consequence, decrease energy intake and body weight.

impact of in-between meal snacking and frequent eating On the other hand, snacking between meals may not be

satiating (Booth, 1988; Marmonier et al., 2002) and there-

fore, habitual snacking may be a factor driving energy intake

Correspondence: Dr H Bertéus Forslund, Department of Clinical Nutrition, up and instead increase body weight. Although, short

Sahlgrenska Academy, Göteborg University, Medicinaregatan 7a, S-405 30 experimental studies in obese subjects have not shown any

Göteborg, Sweden.

effect of eating frequency on weight loss in energy-restricted

E-mail: helene.berteus.forslund@medfak.gu.se

Contributors: HBF initiated, designed and conducted the study, collected the diets (Garrow et al., 1981; Verboeket-van de Venne and

data, did the statistical analysis and wrote the paper. SK, HH and ML collected Westerterp, 1993), epidemiological studies suggest a link

the data, participated in the discussion of results and reviewed the paper. JT between snacking and weight gain (Basdevant et al., 1993;

and AKL participated in the study design, the discussion of the results and

Coakley et al., 1998; Levitsky et al., 2004). Subjects who

reviewed the paper.

Received 8 December 2006; revised 17 April 2007; accepted 13 June 2007; regain weight after successful weight reduction also report

published online 15 August 2007 more snacks than those who maintain their weight lossSnacks in obesity treatment

H Bertéus Forslund et al

1309

(Kayman et al., 1990). These findings are in line with a Dietary intervention

number of studies showing that a high meal frequency and The study was a 1-year intervention with dietician counsel-

snacking are related to a high energy intake (Dwyer et al., ing at a regular basis. Before study start, all patients met a

2001; Zizza et al., 2001; Bertéus Forslund et al., 2002, 2005). dietician at a screen visit and received written and oral

The effect of eating frequency is important to understand information about the study. From start of the study to the

and an evidence-based appraisal is needed (Bellisle et al., inclusion visit the patient met the dietician every 2 weeks up

1997; de Graaf, 2000; Bray and Bouchard, 2004; Mattson, to week 12 and thereafter, every 4 weeks up to week 52. In

2005; Parks and McCrory, 2005). If snacking increases total, 17 visits were offered, from inclusion visit to week 52.

the total energy intake the recommendation to eat snacks Each visit lasted for approximately 45 min.

in between meals may be questioned in obesity treatment. At the inclusion visit the dietician gave instruction about

For that reason longer, randomized interventions in free- the allocated eating frequency. As a guide for portion sizes

living obese subjects are needed to elucidate the role of and meal/snack composition an individualized energy-

snacking in obesity treatment. To our knowledge no such restricted, nutritionally balanced diet plan was prepared

studies exist. and handed out to the patients at the next visit. The

The aim of this study was therefore to study the effect calculations of prescribed energy level were based on basal

of two different recommended eating frequencies on 1-year metabolic rate (BMR) estimated according to the formula of

weight loss in a randomized design. The hypothesis was that Harris and Benedict (1919). From BMR, total daily energy

it is easier to control energy intake and lose weight if food expenditure was calculated by multiplying a physical activity

intake is concentrated to three main meals per day compared level (PAL) 1.3 for moderate physical activity and PAL 1.5

to three main meals and three snacks. for heavy physical activity. From the estimated total energy

expenditure 30% was subtracted to get the prescribed energy

intake. The minimum energy level prescribed was 1400 kcal/

Methods day. The prescribed energy level was divided into three meals

or three meals and three snacks depending on which group

Study design the patient was randomized to. Recommended energy intake

A 1-year, parallel group, randomized clinical trial was in the group of 3M was divided in breakfast, 30% of daily

conducted with two treatment groups with different eating energy intake (D%), lunch 35D% and dinner 35D% and no

frequencies; three meals per day (3M) or three meals snacks with the exception of limited fruit intake and calorie-

and three snacks per day (3 þ 3M). The study was conducted free drinks. For the group of 3 þ 3M the daily energy intake

at three medical outpatient clinics in the western and was divided in breakfast 20D%, lunch 25D%, dinner 25D%

southern part of Sweden (Sahlgrenska Hospital, Skaraborg and three snacks, each on 10D%. In all other respects the

Hospital and Helsingborg Hospital). The recruitment period prescribed diet followed Swedish Nutrition Recommenda-

was from September 2002 to January 2005 and the tions (SNR) (Livsmedelsverket, 1997). The patients were

intervention period from September 2002 to January 2006. encouraged to follow the allocated eating frequency

The study was coordinated from the obesity unit at throughout the study and the individualized diet plan was

Sahlgrenska University Hospital, Göteborg and at each study used as a guideline to enable changing eating behavior. In

site a local dietician, physician and nurse were responsible addition, the patients were encouraged to increase their

for the running of the study. All participants received written physical activity, primarily walking on a regular basis.

and oral information about the study protocol from the Thus, the patients received individual counseling in

registered dietician at each site and gave written informed changes of diet and physical activity behavior. A diet-

consent. The study was approved by the ethics committees counseling plan was followed by the dieticians to ensure a

at the Faculty of Medicine, Göteborg University (Göteborg concordant treatment between the study sites. The diet-

and Skövde) and Faculty of Medicine, Lund University counseling plan included themes for every visit, nutritional

(Helsingborg). information, fact sheets and self-monitoring exercises. Food

Body weight, height (only at baseline), waist and hip and physical activity records could be used as a pedagogic

circumference and blood pressure were measured and tool. Even if each visit had a preplanned topic the counseling

fasting blood samples were collected at baseline and after was individualized, focusing on specific individual problems.

1 year. In addition, body weight was measured at every However, adherence to the allocated eating pattern was

visit. Self-administered questionnaires including information emphasized at all visits.

on eating frequency, energy intake and physical activity were

also completed at baseline and after 1 year. The

primary outcome was change in weight after 1 year of Compliance

treatment. Secondary outcomes included changes in blood Compliance to the recommended eating frequency was

pressure, cardiovascular risk factors, energy intake, evaluated by repeated telephone interviews at six predefined

eating frequency and the subjects’ own evaluation of the time periods during the year of intervention. The interviews

treatment. were carried out by the dietician, who coordinated the study

European Journal of Clinical NutritionSnacks in obesity treatment

H Bertéus Forslund et al

1310

at Sahlgrenska University Hospital. ‘The meal pattern was used. The questionnaire was distributed at baseline and

questionnaire’ was used as a basis for the assessment of at the end of the study. The dietary questionnaire is judged

intake occasions (Bertéus Forslund et al., 2002). The subjects to give valid results in both obese and normal weight

were asked about their intake pattern the previous day subjects. The questionnaire is described elsewhere (Lindroos

specifying time and type of intake occasions. Food choices et al., 1993).

at snack meals were registered specifically; other intake

occasions were registered according to the meal types in the

questionnaire. The telephone interviews were conducted on Assessment of physical activity

randomly selected days with emphasis to cover different A questionnaire describing physical activity at work and

days of the week. If it was impossible to get in contact with during leisure time was used (Larsson et al., 2004). Occupa-

the subject in the predefined time period the interview was tional PAL was categorized in five levels; unemployed,

omitted in this period. sedentary work, moderately sedentary work, moderately

heavy work and heavy work. Leisure time physical activity

was categorized in four levels; sedentary leisure, moderately

Anthropometrical measures activity, moderate exercise and heavy exercise. The partici-

Body weight was measured to the nearest 0.05 kg with the pants choose one of the alternatives corresponding to their

patient wearing underwear and no shoes, using calibrated usual activity pattern. In our analyses, the leisure time

scales. Body height was measured without shoes to the activity level ‘sedentary leisure’ and occupational PAL

nearest 0.05 cm. Body mass index (BMI) was calculated from ‘sedentary work’ were coded as sedentary in a dichotomous

weight (kg) divided in height squared (m2). Waist circum- variable, sedentary yes ¼ 1, no ¼ 0.

ference was measured in a standing position at the midpoint

between lower border of the rib cage and the iliac crest. Hip

was measured at the symphysis major trochanter level. Evaluation

To evaluate the subjects’ own opinion on the allocated

eating pattern (3M or 3 þ 3M) they were asked to answer the

Blood pressure and biochemical analyses questions on a Visual Analog Scale: ‘How content are you

Blood pressure was measured after 5 min in a sitting position with eating 3 (3 þ 3) meals per day?’ (not content ¼ 0, very

on the right arm. Blood samples; P-glucose, S-insulin, S- content ¼ 100). ‘How easy did you find it eating 3 (3 þ 3)

cholesterol, S-high-density lipoprotein (HDL), S-low-density meals per day? (very difficult ¼ 0, very easy ¼ 100). ‘Would

lipoprotein (LDL) and S-triglycerides were drawn in a fasting you consider eating 3 (3 þ 3) meals per day from now on?’

state, that is no food or drink were allowed from 1200 the (Yes ¼ 1/No ¼ 2).

night before measurement day. Blood samples were analyzed

locally at the central clinical laboratories at Sahlgrenska

University Hospital, Skaraborg Hospital and Helsingborg Subjects

Hospital. Laboratory analyses were the same as those used in Patients referred to the obesity unit at Sahlgrenska University

ordinary patient care according to local practice. Hospital, Göteborg, obesity research unit at Helsingborg

Hospital, Helsingborg and at the Medical clinic at Skaraborgs

Hospital, Skövde were invited to participate at the first visit

Assessment of eating pattern to the clinics. At the latter, clinic participants were also

A self-administered questionnaire, ‘The meal pattern ques- recruited through local advertisement. The patients were

tionnaire’, was used to assess habitual daily intake pattern. recruited continuously over time, starting at Sahlgrenska

The questionnaire was distributed at baseline and at the end University Hospital in September 2002. To speed up recruit-

of study. The subjects were asked to describe how they eat ‘an ment Helsingborg Hospital joined in March 2003 and

ordinary’ day, specifying time for each intake occasion and Skaraborgs Hospital in March 2004.

choose one of four predefined types of intake occasions; The selection criteria to enter the study included age 18–60

main meal, light meal/breakfast, snacks and drink only. years and BMI430 kg/m2. Subjects reporting previous obe-

In the analysis of the eating pattern, main meals and light sity surgery, anti-obesity drug treatment the last year, drug-

meal/breakfast were added together and called principal or insulin-treated diabetes, hypothyroidism, severe psychia-

meals (one light meal/breakfast and two main meals or two tric disorder, bulimia, drug or alcohol abuse were not eligible

light meals/breakfast and one main meal). The questionnaire for the study.

is described elsewhere (Bertéus Forslund et al., 2002). Pre-study power calculations showed that 70 subjects were

needed in each group to obtain a significant (Po0.05)

difference in body weight change of 3.075.2 kg with a power

Assessment of dietary intake of 80% and an estimated dropout rate of 35%. Accordingly,

A self-administered dietary questionnaire to assess habitual two groups of each 70 patients were randomly allocated to

energy and macronutrient intake during the past 3 months the two different intervention groups; three meals or three

European Journal of Clinical NutritionSnacks in obesity treatment

H Bertéus Forslund et al

1311

meals and three snacks per day. A block randomization was Screened

used to keep the two groups balanced at all times and evenly n = 170

spread throughout the year, according to Altman (1991). The

two groups were in blocks of four at a time. In each block Excluded or

refused to participate

two subjects got group ‘three meals’ and two subjects got n = 30

group ‘three meals þ three snacks per day’ in a random order. Randomly allocated to two

treatment groups

Blinded and sealed envelopes for the randomization were n = 140

prepared at the Sahlgrenska site and sent out to the two

other sites. The procedure was supervised from the Sahl-

Allocated to 3 meals and

Allocated to 3 meals regimen

grenska University Hospital and the sites were in contact n = 70

3 snacks regimen

n = 70

continuously. Randomization was carried out at the inclu-

sion visit and the dietician gave instruction about the

allocated eating frequency.

Dropped out during intervention Dropped out during intervention

n = 21 n = 26

Statistics

To analyze differences between groups w2 test was used for Completed the intervention Completed the intervention

n = 49 n = 44

proportions, McNemars’ test for paired proportions and t-test

for continuous variables. Survival analysis was used to Figure 1 Flow chart.

compare time for dropout in the two study groups. Weight,

anthropometry and laboratory variables were analyzed in

completers and in all participants using the last observation principal meals per day did not differ between the 3M and

carried forward (LOCF). Repeated measures analysis was used 3 þ 3M group. However, change in number of snacks differed

to analysis weight change between study groups over time. significantly between the two groups. The 3M group

The SAS 8.2 statistical package was used for all analyses (SAS decreased the number of snacks whereas the 3 þ 3M group

Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA). increased snack frequency (Po0.0001, confidence interval

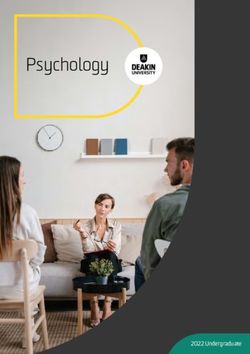

(CI) 2.18 to 1.06). Figures 2a and b show the percent

completers in each group reporting number of principal

Results meals and snacks before treatment and after 1 year.

After 1 year of treatment 22 patients (45%) in the 3M

Participation flow group reported consuming the recommended three principal

A total of 140 (36 men and 104 women) patients were meals and no snacks whereas 21 patients (48%) in the 3 þ 3M

randomized and 93 (27 men and 66 women) patients group reported having the recommended three principal

completed the entire study. Participation flow is shown in meals and three snacks.

Figure 1. Dropout rate was 30% in the 3M group and 37.1%

in the 3 þ 3M group, although the difference was not

statistical significant (P ¼ 0.37). There was no difference in Diet and physical activity

time of attrition between the study groups (P ¼ 0.27). Mean energy and macronutrient intake and physical activity

However, younger patients (P ¼ 0.004) and patients with at baseline and after 1 year of treatment is shown in Table 2.

lower BMI (P ¼ 0.01) dropped out from the study program Reported energy intake decreased with 2955 kJ (707 kcal) in

earlier than older patients and those with higher BMI. In the 3M group compared to 2178 kJ (521 kcal) in the 3 þ 3M

addition more men in the 3m group dropped out compared group and the decrease did not differ significantly between

to the 3 þ 3M group (7/18 compared to 2/18, respectively; the two groups. The reported change in energy intake was in

P ¼ 0.05) whereas in women dropout rate was higher in men 4140 kJ (991 kcal) and 2021 kJ (484 kcal) in 3 and 3 þ 3M

the 3 þ 3M group than the 3M group (24/52 and 14/52, groups, respectively. Corresponding figures for women were

respectively; P ¼ 0.04). Baseline characteristics for all study 2584 kJ (618 kcal) and 2274 kJ (544 kcal) in the 3 and 3 þ 3M

participants and for completers in both groups are shown in groups, respectively. Furthermore, change in energy percent

Table 1. Baseline characteristics did not differ significantly macronutrient intake did not differ between the two groups.

between completers and all participants included in the Although both groups decreased the energy percent fat

study. Neither did the participants who completed the study intake and increased energy percent protein and fiber intake

differ between the three study sites. expressed as g/1000 kcal from baseline to week 52.

After 1 year of treatment number of patients reporting

sedentary lifestyle decreased significantly in both groups and

Eating frequency there was no significant difference between the groups.

Intake of eating occasions at baseline and after 1 year of Neither did changes in sedentary work differ between the

treatment is presented in Table 2. The change in number of groups (Table 2).

European Journal of Clinical NutritionSnacks in obesity treatment

H Bertéus Forslund et al

1312

Table 1 Baseline characteristics for the two groups; three meals (3M) and three meals þ three snacks (3 þ 3M) in 140 patients included in the study and

in 93 patients who completed the study

Characteristic All 3M (n ¼ 70) All 3 þ 3M (n ¼ 70) Completers 3M (n ¼ 49) Completers 3 þ 3M (n ¼ 44)

Gender (M/F) 18/52 18/52 11/38 16/28

Age (year) 38.7711.6 40.1711.5 40.6711.1 41.8711.0

Weight (kg) 113.0718.6 112.6721.5 113.9719.8 118.2723.0

Height (m) 1.7270.1 1.7170.1 1.7170.1 1.7370.1

BMI (kg/m2) 38.375.3 38.476.0 38.875.8 39.476.5

Circumference measure (cm)

Waist 117.0711.7 115.7712.8 117.5712.0 118.0713.6

Hip 125.2711.6 123.4711.6 125.6712.8 124.9713.0

Blood pressure (mm Hg)

Systolic 127.1715.2 129.7716.5 127.5715.2 131.2716.4

Diastolic 82.879.0 81.9710.5 83.379.3 83.879.8

Blood analysis

P-glucose (mmol/l) 5.470.6 5.470.9 5.470.6 5.470.8

S-insulin (mU/L) 18.5711.6 17.7711.4 18.8713.1 18.6712.5

S-cholesterol (mmol/l) 5.370.9 5.270.9 5.470.9 5.370.9

S-HDL (mmol/l) 1.470.4 1.470.3 1.370.3 1.470.3

S-LDL (mmol/l) 3.370.8 3.270.8 3.470.8 3.370.8

S-triglycerides (mmol/l) 1.871.0 1.670.6 1.871.0 1.670.6

Abbreviations: F, female; HDL, high-density lipoprotein; LDL, low-density lipoprotein; M, male; P, plasma; S, serum.

Mean values7s.d. are presented.

Table 2 Intake of meals and snacks, dietary intake and physical activity in the three-meal (3M, n ¼ 49) and 3 þ 3 meal (3 þ 3M, n ¼ 44) groups of

completers at baseline and after 1 year of treatment

Variable Baseline Week 52 P for difference between changes 95% CI for difference between changes

Principal meals (n)

3 meals (n ¼ 47) 2.970.7 2.970.4

3 þ 3 meals (n ¼ 42) 2.870.7 3.070.3a 0.051 0.66 to 0.004

Snacks (n)

3 meals (n ¼ 47) 1.870.9 0.770.7b

3 þ 3 meals (n ¼ 42) 1.971.6 2.370.9c o0.0001 2.18 to 1.06

Energy intake, kJ (kcal)

3 meals (n ¼ 46) 11 72575141 877072546

(280571230) (20987609)d

3 þ 3 meals (n ¼ 44) 11 08573804 898773666 0.51 3118 to 1568

(26527910) (21507877)e (746 to 375)

Protein (E%)

3 meals (n ¼ 46) 15.872.6 17.072.4e

3 þ 3 meals (n ¼ 44) 16.472.2 18.272.7d 0.31 2.0 to 0.6

Fat (E%)

3 meals (n ¼ 46) 35.275.0 33.474.2a

3 þ 3 meals (n ¼ 44) 34.975.7 32.275.6c 0.54 2.1 to 4.0

Carbohydrate (E%)

3 meals (n ¼ 46) 46.975.1 46.975.0

3 þ 3 meals (n ¼ 44) 46.476.1 47.575.7 0.48 4.3 to 2.0

Mono-disaccharides (E%)

3 meals (n ¼ 46) 21.476.6 20.675.1

3 þ 3 meals (n ¼ 44) 21.076.0 21.075.8 0.64 4.4 to 2.7

Fiber (g/1000 kcal)

3 meals (n ¼ 46) 8.972.4 11.273.1d

3 þ 3 meals (n ¼ 44) 8.972.2 11.672.7b 0.17 2.0 to 1.2

European Journal of Clinical NutritionSnacks in obesity treatment

H Bertéus Forslund et al

1313

Table 2 Continued

Variable Baseline Week 52 P for difference between changes 95% CI for difference between changes

Sedentary leisure time (%)

3 meals (n ¼ 49) 30.6 14.3e

3 þ 3 meals (n ¼ 44) 38.6 22.7c 0.75

Sedentary at work (%)

3 meals (n ¼ 49) 32.7 30.6

3 þ 3 meals (n ¼ 44) 40.9 38.6 0.63

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; E%, energy percent.

The P-value and 95% CIs are difference in change between the two groups from baseline to W52.

a

P ¼ 0.06, bPo0.0001, cPo0.05, dPo0.001, ePo0.01 for difference from baseline.

100

90

80

70

% completers

60

50 3M

40 3+3 M

30

20

10

0

1 2 3 4 1 2 3 4

Baseline One year

Number of principal meals per day

60

3M

50

3+3 M

% completers

40

30

20

10

0

0 1 2 3 ≥4 0 1 2 3 ≥4

Baseline One year

Number of snacks per day

Figure 2 (a) Percent completers reporting number of principal meals per day at baseline and after 1 year of treatment in the 3M and 3 þ 3M

groups. (b) Percent completers reporting number of snacks per day at baseline and after 1 year of treatment in the 3M and 3 þ 3M groups.

Compliance line with the meal frequency reported by the subjects at the

Repeated interviews on eating frequencies with emphasis end of study as described in the section ‘Eating frequency’.

on snacking were conducted throughout the study. Mean

number of interviews was 4.4 per subject. Reported mean

number of principal meals and snacks is described in Table 3. Weight loss

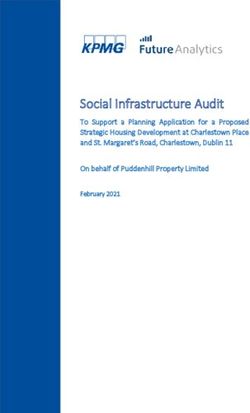

The 3M group reported fewer snacks than the 3 þ 3M group. Weight loss after 1 year of treatment was in the 3M group

In the 3 þ 3M group the frequency of snacks was decreasing 4.176.1 kg (3.674.9%) and in the 3 þ 3M group

in the latter study period. The results of compliance are in 5.979.4 kg (4.776.7%) and did not differ significantly

European Journal of Clinical NutritionSnacks in obesity treatment

H Bertéus Forslund et al

1314

(P ¼ 0.31). When analyzing weight loss over time no intake and weight loss. Even if omitting snacks may help

difference was found between the two groups neither in cutting down energy intake, our result implies that when

the completers only (P ¼ 0.34) nor in all participants using patients attain extensive support and diet counseling they

LOCF (P ¼ 0.35) (Figures 3a and b). manage to cut down calories despite a high snacking

frequency. The choice of low-energy dense snacks is crucial

and we can only speculate if the good quality snack choices

Metabolic variables

Changes in blood pressure, blood glucose, insulin, cholesterol,

LDL, HDL and triglycerides did not differ between the

groups. However, HDL increased in the 3M group compared 130

to the 3 þ 3M group (Po0.033) (Table 4).

3M

125 3+3 M

Evaluation 120

The patients’ personal opinion on the meal regimen was

Kg

evaluated. When analyzing the question ‘How content are 115

you with eating 3 (3 þ 3) meals per day?’ no difference was

found between the two groups. The mean score was 55 and 110

63% in the 3M and 3 þ 3M groups (P ¼ 0.14), respectively.

Neither was a difference found between the groups replying 105

the question ‘How easy did you find it eating 3 (3 þ 3) meals

per day?’ showing a mean score of 50 and 55% in the 3M and 100

3 þ 3M group (Po0.30), respectively. Nor was a difference w. 0 w. 12 w. 24 w. 36 w. 52

found when asking ‘Would you consider eating 3 (3 þ 3) Visit week

meals per day from now on?’; 51% of the patients in the 3M 130

group reported ‘yes’ compared to 68% in the 3 þ 3M group

(Po0.10). 3M

125 3+3 M

120

Discussion

Kg

115

In this 1-year randomized clinical trial subjects in both

groups lost weight and improved their metabolic profile over 110

1 year. However, weight loss did not differ significantly

between the two intervention arms suggesting that recom- 105

mending snacks or not between meals is not an important

factor for achieved weight loss after 1 year. As previous cross- 100

sectional studies have shown that a high eating frequency w. 0 w. 12 w. 24 w. 36 w. 52

and snacking increase total energy intake (Bertéus Forslund Visit week

et al., 2002, 2005), we hypothesized that no snacking Figure 3 (a) Mean weight and 95% CI in completers (n ¼ 92). (b)

between meals would facilitate the restriction of energy Mean weight and 95% CI in all subjects (n ¼ 140) using LOCF.

Table 3 Compliance to the meal pattern recommendation in the 3M and 3 þ 3M groups of completers at repeated interviews during 1-year dietary

intervention

1 2 3 4 5 6

3M

Principal meals 2.8 (1–3) 2.9 (2–4) 2.7 (1–4) 2.8 (2–3) 2.7 (2–3) 2.7 (1–3)

Snacks 0.5 (0–3) 0.4 (0–2) 0.5 (0–2) 0.5 (0–2) 0.8 (0–3) 0.7 (0–2)

(n ¼ 49) (n ¼ 32) (n ¼ 28) (n ¼ 41) (n ¼ 43) (n ¼ 30) (n ¼ 23)

3 þ 3M

Principal meals 2.8 (1–4) 2.8 (1–4) 2.7 (0–3) 2.4 (1–3) 2.9 (2–4) 2.6 (1–3)

snacks 2.2 (0–4) 2.5 (1–5) 2.2 (1–4) 1.4 (0–3) 1.6 (0–3) 1.9 (0–4)

(n ¼ 44) (n ¼ 38) (n ¼ 31) (n ¼ 41) (n ¼ 40) (n ¼ 36) (n ¼ 27)

Reported mean (min–max) number of principal meals and snacks at six interview periods.

European Journal of Clinical NutritionSnacks in obesity treatment

H Bertéus Forslund et al

1315

Table 4 Fasting blood samples and blood pressure in the three-meal changed eating patterns toward the recommended number

(3M, n ¼ 49) and 3 þ 3 meal (3 þ 3M, n ¼ 44) groups of completers at of snacks and the reported number of snacks differed

baseline and after 1 year of treatment

significantly between the groups after 1 year. Adherence

Baseline 1 year Change P-value was also similar in the two groups. This suggests that many

subjects in the present study managed to change eating

P-glucose (mmol/l) patterns despite the difficulties in doing so reported by other

3M 5.470.6 5.370.6 0.1670.46* NS

investigators (King and Gibney, 1999). It is noteworthy

3 þ 3M 5.470.8 5.070.5 0.3370.78**

that the subject’s own opinion on difficulties did not differ

S-insulin (mU/l) between the groups. However it should be noted that the

3M 18.8713.1 14.678.4 4.0711.0* NS discrepancy in snacking between the two groups was not

3 þ 3M 18.6712.5 15.377.9 3.4710.3*

as large as intended. This suggests that the difference in

S-cholesterol (mmol/l) snacking patterns might not have been large enough to

3M 5.470.9 5.371.0 0.1170.59 NS attain a difference in weight loss.

3 þ 3M 5.370.9 5.170.9 0.1670.64 The weight loss difference between the treatment arms

was 1.8 kg. It may be argued that we did not have enough

S-HDL (mmol/l)

3M 1.370.3 1.470.3 þ 0.170.21** 0.033 statistical power to find a difference due to too small study

3 þ 3M 1.470.3 1.470.3 þ 0.0270.15 groups. When planning the study we decided that a

difference of 3 kg or more would be considered clinically

S-LDL (mmol/l)

relevant in a weight loss trial. This is in line with anticipated

3M 3.470.8 3.370.8 0.1070.50 NS

3 þ 3M 3.370.8 3.270.8 0.0870.60 weight loss differences used in power calculations in other

studies (Heshka et al., 2003; Samaha et al., 2003; Brinkworth

S-TG (mmol/l) et al., 2004).

3M 1.871.0 1.671.0 0.1770.88 NS

Previous studies on eating patterns have focused mainly

3 þ 3M 1.670.6 1.470.6 0.2370.58**

on the influence on metabolic factors. Spreading the

Systolic BP (mm Hg) nutrient load on many small meals may reduce insulin and

3M 127715 125716 3.3711.3* NS glucose response and improve blood lipid profile (Fábry

3 þ 3M 131716 128716 4.0712.7*

et al., 1964; Jenkins et al., 1989, 1992) although findings are

Diastolic BP (mm Hg) inconsistent (Beebe et al., 1990; Arnold et al., 1994, 1997;

3M 8379 81710 2.4710.3 NS Thomsen et al., 1997). In this study metabolic variables were

3 þ 3M 84710 81710 2.379.9 improved in both groups after 1 year but did not differ

except for HDL cholesterol that increased in the 3M group.

Abbreviations: BP, blood pressure; HDL, high-density lipoprotein; LDL, low-

density lipoprotein; NS, not significant; P, plasma; S, serum; TG, triglycerides. The literature on eating frequency and HDL cholesterol is

Mean values7s.d. are presented. inconsistent. In short experimental studies HDL cholesterol

Significant difference from baseline within group *Po0.05, **Po0.01. has been positively (McGrath and Gibney, 1994), negatively

(Murphy et al., 1996; Thomsen et al., 1997) or unrelated

(Arnold et al., 1993, 1994) to eating frequency. Therefore, we

will be sustained without extensive support. It may be cannot role out that the difference in HDL cholesterol is a

suggested that the role of snacking is different in obese ‘real chance finding.

life’ and during treatment conditions. Not only frequency Attrition is usually high in obesity treatment studies

but regularity of meal times may also have an impact on (Glenny et al., 1997). The dropout rate in this study was

energy intake. In a recent study by Farshchi et al. (2005) similar to what we had expected and in line with with-

obese women were instructed to maintain their usual intake drawals found in other studies (Clark et al., 1995; Torgerson

on an irregular (‘caotic’ pattern with 3–9 meals/day) vs an et al., 1999). In line with other studies we also found that

regular (6 meals/day) meal pattern in a 14-day crossover younger patients dropped out earlier than older patients

design. The obese women reported a significantly higher (Andersson and Rossner, 1997; Torgerson et al., 1999; Lantz

energy intake during the irregular meal pattern than during et al., 2003a, b). However, patients with lower BMI dropped

the regular meal pattern. In a similar study in lean women, out earlier, which is in contrast to others that found no

energy intake did not differ between the two meal patterns association between BMI and attrition (Andersson and

suggesting that eating patterns may have different implica- Rossner, 1997; Torgerson et al., 1999; Lantz et al., 2003a) or

tions in normal weight and obese subjects (Farshchi et al., that those with higher BMI dropped out more frequently

2004). Although we do not know how regular the patients (Clark et al., 1995). One study with a very high dropout rate

were eating during the intervention, it is possible that the (77%) also found that dropouts had a slightly lower BMI

extensive support helped the patients to follow a more than completers (Inelmen et al., 2005).

regular meal pattern. The larger withdrawal in men from the 3M group and

A crucial point when evaluating our weight loss results is women from the 3 þ 3M group indicates that preferred

the adherence to the allocated intervention. Both groups snacking frequency may differ by gender. We can only

European Journal of Clinical NutritionSnacks in obesity treatment

H Bertéus Forslund et al

1316

speculate if men find it easier to adhere to a frequent Arnold L, Mann JI, Ball MJ (1997). Metabolic effects of alterations in

snacking pattern than no snacks whereas women do the meal frequency in type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care 20, 1651–1654.

Arnold LM, Ball MJ, Duncan AW, Mann J (1993). Effect of

opposite. Although, gender differences have also been noted

isoenergetic intake of three or nine meals on plasma lipoproteins

in a previous intervention study. This study showed that and glucose metabolism. Am J Clin Nutr 57, 446–451.

men who adhered to three principal meals and two or three Basdevant A, Craplet C, Guy-Grand B (1993). Snacking patterns in

snacks per day lost more weight than those who did not, obese French women. Appetite 21, 17–23.

Beebe CA, Van Cauter E, Shapiro ET, Tillil H, Lyons R, Rubenstein AH

whereas women who adhered to this eating pattern lost less

et al. (1990). Effect of temporal distribution of calories on diurnal

weight than those who did not (H Bertéus Forslund, personal patterns of glucose levels and insulin secretion in NIDDM.

communication). Gender differences have also been noted Diabetes Care 13, 748–755.

in observational studies suggesting a negative association Bellisle F, McDevitt R, Prentice AM (1997). Meal frequency and

between meal frequency and BMI or body weight in men and energy balance. Br J Nutr 77, S57–S70.

Bertéus Forslund H, Lindroos A, Sjöström L, Lissner L (2002). Meal

a positive or no relationship in women (Drummond et al., patterns and obesity in Swedish women—a simple instrument

1998; Titan et al., 2001). describing usual meal types, frequency and temporal distribution.

Thus, one limitation of the present study is that we lack Eur J Clin Nutr 56, 740–747.

power to analyze gender differences. Another limitation is Bertéus Forslund H, Torgerson JS, Sjostrom L, Lindroos AK (2005).

Snacking frequency in relation to energy intake and food choices

that the recruitment period was very long. To speed up in obese men and women compared to a reference population. Int

recruitment we involved two other study sites. This made the J Obes Relat Metab Disord 29, 711–719.

study more heterogeneous. On the other hand recruiting Booth DA (1988). Mechanism from model-actual effects from real

subjects from different parts of Sweden strengthens the life: the zero-calorie drink-break option. Appetite 11 (Suppl),

94–102.

generalizablity of the results.

Booth DA, Blair AJ, Lewis VJ, Baek SH (2004). Patterns of eating and

In Sweden, the commonly used dietary recommendation movement that best maintain reduction in overweight. Appetite

in obesity treatment is based on the general dietary 43, 277–283.

recommendations for the whole Swedish population, SNR Bray G, Bouchard C (2004). Handbook of Obesity: Etiology and Patho-

physiology. Marcel Dekker: Baton Rouge, Louisiana. pp. 453–454.

(Livsmedelsverket, 1997). The SNR recommendations in-

Brinkworth GD, Noakes M, Keogh JB, Luscombe ND, Wittert GA,

clude eating frequency as well as temporal distribution of Clifton PM (2004). Long-term effects of a high-protein, low-

energy over the day. An eating frequency of 3 main meals carbohydrate diet on weight control and cardiovascular risk

and 2–3 snacks has been recommended, although revised to markers in obese hyperinsulinemic subjects. Int J Obes Relat Metab

1–3 snacks/day recently (Livsmedelsverket, 2005). However, Disord 28, 661–670.

Clark MM, Guise BJ, Niaura RS (1995). Obesity level and attrition:

the evidence that this recommendation facilitates energy support for patient-treatment matching in obesity treatment. Obes

restriction and weight control is not substantiated. This Res 3, 63–64.

study showed that approximately half of the patients in each Coakley EH, Rimm EB, Colditz G, Kawachi I, Willett W (1998).

group managed to adhere to the allocated ‘no snack’ or Predictors of weight change in men: results from the Health

Professionals Follow-up Study. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord 22,

‘three-snack’ pattern and also considered to continue this 89–96.

eating pattern after the study had ended. The findings from de Graaf C (2000). Nutritional definitions of the meal. In: Meiselman

this study also suggest that a recommended energy-restricted H (ed). Dimensions of the Meal. Aspen Publishers: Gaitersburg, MD.

diet results in similar weight loss irrespective high- or low- pp. 47–56.

DPP (2002). The Diabetes Prevention Program (DPP): description of

eating frequency. Consequently, recommending snacks in

lifestyle intervention. Diabetes Care 25, 2165–2171.

obesity treatment should be based on individual needs rather Drummond S, Crombie N, Kirk T (1996). A critique of the effects of

than that all patients should eat snacks or not. snacking on body weight status. Eur J Clin Nutr 50, 779–783.

Drummond SE, Crombie NE, Cursiter MC, Kirk TR (1998). Evidence

that eating frequency is inversely related to body weight status in

male, but not female, non-obese adults reporting valid dietary

Acknowledgements intakes. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord 22, 105–112.

Dwyer JT, Evans M, Stone EJ, Feldman HA, Lytle L, Hoelscher D et al.

(2001). Adolescents’ eating patterns influence their nutrient

We thank Ted Lystig for statistical advice. This study was intakes. J Am Diet Assoc 101, 798–802.

supported by a grant from Västra Götalandsregionen. Elfhag K, Rossner S (2005). Who succeeds in maintaining weight

loss? A conceptual review of factors associated with weight loss

maintenance and weight regain. Obes Rev 6, 67–85.

Fábry P, Hejl Z, Fodor J, Braun T, Zvolánkov á K (1964). The frequency

References of meals. Its relation to overweight, hypercholesterolemia and

decreased glucose-tolerance. Lancet 2, 614–615.

Altman D (1991). Practical Statistics for Medical Research. Chapman & Farshchi HR, Taylor MA, Macdonald IA (2004). Regular meal

Hall: London. pp 87–88. frequency creates more appropriate insulin sensitivity and lipid

Andersson I, Rossner S (1997). Weight development, drop-out profiles compared with irregular meal frequency in healthy lean

pattern and changes in obesity-related risk factors after two years women. Eur J Clin Nutr 58, 1071–1077.

treatment of obese men. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord 21, 211–216. Farshchi HR, Taylor MA, Macdonald IA (2005). Beneficial metabolic

Arnold L, Ball M, Mann J (1994). Metabolic effects of alterations in effects of regular meal frequency on dietary thermogenesis,

meal frequency in hypercholesterolaemic individuals. Athero- insulin sensitivity, and fasting lipid profiles in healthy obese

sclerosis 108, 167–174. women. Am J Clin Nutr 81, 16–24.

European Journal of Clinical NutritionSnacks in obesity treatment

H Bertéus Forslund et al

1317

Garrow JS, Durrant M, Blaza S, Wilkins D, Royston P, Sunkin S (1981). Marmonier C, Chapelot D, Fantino M, Louis-Sylvestre J (2002).

The effect of meal frequency and protein concentration on the Snacks consumed in a nonhungry state have poor satiating

composition of the weight lost by obese subjects. Br J Nutr 45, efficiency: influence of snack composition on substrate utilization

5–15. and hunger. Am J Clin Nutr 76, 518–528.

Glenny AM, O’Meara S, Melville A, Sheldon TA, Wilson C (1997). The Mattson MP (2005). The need for controlled studies of the effects of

treatment and prevention of obesity: a systematic review of the meal frequency on health. Lancet 365, 1978–1980.

literature. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord 21, 715–737. McGrath SA, Gibney MJ (1994). The effects of altered frequency of

Harris JA, Benedict FG (1919). A Biometric Study of Basal Metabolism in eating on plasma lipids in free-living healthy males on normal

Man. The Carnegie Institute: Washington DC. self-selected diets. Eur J Clin Nutr 48, 402–407.

Heshka S, Anderson JW, Atkinson RL, Greenway FL, Hill JO, Phinney Murphy MC, Chapman C, Lovegrove J, Isherwood SG, Morgan LM,

SD et al. (2003). Weight loss with self-help compared with a Wright JW et al. (1996). Meal frequency; does it determine

structured commercial program: a randomized trial. JAMA 289, postprandial lipaemia? Eur j Clin Nutr 50, 491–497.

1792–1798. NIH (1998). Clinical guidelines on the identification, evaluation, and

Inelmen EM, Toffanello ED, Enzi G, Gasparini G, Miotto F, Sergi G treatment of overweight and obesity in adults—the evidence

et al. (2005). Predictors of drop-out in overweight and obese report. National Institutes of Health. Obes Res 6 (Suppl 2),

outpatients. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord 29, 122–128. 51S–209S.

Jebb SA (2005). Dietary strategies for the prevention of obesity. Parks EJ, McCrory MA (2005). When to eat and how often? Am J Clin

Proc Nutr Soc 64, 217–227. Nutr 81, 3–4.

Jenkins DJA, Ocana A, Jenkins AL, Wolever TMS, Vuksan V, Katzman Samaha FF, Iqbal N, Seshadri P, Chicano KL, Daily DA, McGrory J

L et al. (1992). Metabolic advantages of spreading the nutrient et al. (2003). A low-carbohydrate as compared with a low-fat diet

load: effects of increased meal frequency in non-insulin-depen- in severe obesity. N Engl J Med 348, 2074–2081.

dent diabetes. Am J Clin Nutr 55, 461–467. SBU Statens beredning för medicinsk utvärdering (2002). Fetma—

Jenkins DJA, Wolever TMS, Vuksan V, Brighenti F, Cunnane SC, problem och åtgärder. En systematisk litteraturöversikt: Göteborg.

Venketeshwer R et al. (1989). Nibbling versus gorging: metabolic Speechly DP, Rogers GG, Buffenstein R (1999). Acute appetite

advantages of increased meal frequency. N Eng J Med 321, reduction associated with an increased frequency of eating in

929–934. obese males. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord 23, 1151–1159.

Kayman S, Bruvold W, Stern JS (1990). Maintenance and relapse after Thomsen C, Christiansen C, Rasmussen OW, Hermansen K (1997).

weight loss in women: behavioral aspects. Am J Clin Nutr 52, Comparison of the effects of two weeks’ intervention with

800–807. different meal frequencies on glucose metabolism, insulin sensi-

King S, Gibney M (1999). Dietary advice to reduce fat intake is more tivity and lipid levels in non-insulin-dependent diabetic patients.

successful when it does not restrict habitual eating patterns. J Am Ann Nutr Metab 41, 173–180.

Diet Assoc 99, 685–689. Titan SM, Bingham S, Welch A, Luben R, Oakes S, Day N et al. (2001).

Kirk TR (2000). Role of dietary carbohydrate and frequent eating in Frequency of eating and concentrations of serum cholesterol in

body-weight control. Proc Nutr Soc 59, 349–358. the Norfolk population of the European prospective investigation

Lantz H, Peltonen M, Agren L, Torgerson JS (2003a). A dietary and into cancer (EPIC-Norfolk): cross sectional study. BMJ 323,

behavioural programme for the treatment of obesity. A 4-year 1286–1288.

clinical trial and a long-term posttreatment follow-up. J Intern Med Torgerson JS, Agren L, Sjostrom L (1999). Effects on body weight of

254, 272–279. strict or liberal adherence to an initial period of VLCD treatment.

Lantz H, Peltonen M, Agren L, Torgerson JS (2003b). Intermittent A randomised, one-year clinical trial of obese subjects. Int J Obes

versus on-demand use of a very low calorie diet: a randomized Relat Metab Disord 23, 190–197.

2-year clinical trial. J Intern Med 253, 463–471. Verboeket-van de Venne WP, Westerterp KR (1993). Frequency of

Larsson I, Lissner L, Näslund N, Lindroos AK (2004). Leisure and feeding, weight reduction and energy metabolism. Int J Obes Relat

occupational physical activity in relation to body mass index in Metab Disord 17, 31–36.

men and women. Scand J Nutr 48, 165–172. Wadden T, Stunkard A (2002). Handbook of Obesity Treatment. The

Levitsky DA, Halbmaier CA, Mrdjenovic G (2004). The freshman Guildford Press: New York. pp 191.

weight gain: a model for the study of the epidemic of obesity. Int J WHO (2003). Diet, Nutrition and the Prevention of Chronic Diseases

Obes Relat Metab Disord 28, 1435–1442. World Health Organ Tech Rep Ser, Vol. 916, pp. i–viii, 1–149,

Lindroos AK, Sjöström L, Lissner L (1993). Validity and reproduci- backcover.

bility of a self-administered dietary questionnaire in obese and Wing RR, Jeffery RW, Burton LR, Thorson C, Nissinoff KS, Baxter JE

nonobese subjects. Eur J Clin Nutr 47, 461–481. (1996). Food provision vs structured meal plans in the behavioral

Livsmedelsverket (1997). Svenska Näringsrekommendationer PO Box treatment of obesity. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord 20, 56–62.

622, S-751 26 Uppsala: Sweden. Zizza C, Siega-Riz A-M, Popkin BM (2001). Significant increase in

Livsmedelsverket (2005). Svenska näringsrekommendationer 2005 PO young adults snacking between 1977–1978 and 1994–1996

Box 622, S-751 26 Uppsala: Sweden. represent a cause for concern!. Prev Med 32, 303–310.

European Journal of Clinical NutritionYou can also read