NetMap Project The - www.netmap.ie

←

→

Page content transcription

If your browser does not render page correctly, please read the page content below

The NetMap Project Research Report Exploring Opportunities to Create Value from Waste Fishing Nets in Ireland www.netmap.ie

Table of Contents

Executive Summary

Introduction

Section One - The Challenge of Marine Plastics & Fishing Gear

1. Overview

1.1 Fishing Gear

1.2 The Impacts of Lost & Discarded Fishing Gear

1.3 Marine Plastic Pollution in Ireland

1.4 Conclusion

2. Relevant International & National Policy

2.1 International Policy

2.2 National Policy

2.3 Conclusion

3. Management of Fishing Nets at Irish Ports

3.1 Introduction

3.2 Cork Port Findings

3.3 National Port Findings

3.4 Aquaculture

3.5 Conclusion

Section Two - Looking Towards Potential Solutions for Ireland

4. Social Enterprise

4.1 Introduction

4.2 The Role of Social Enterprise & the Environment

4.3 European & National Policy supporting Social Enterprise

4.4 Funding & Operational Supports

4.5 Could a Social Enterprise help manage waste Fishing Nets in Ireland?

4.6 Opportunities & Considerations in the establishment of a Social Enterprise.

4.7 Conclusion

5. Concrete Trials

5.1 Introduction

5.2 Trial Methodology

5.3 Trials

5.4 Conclusion

Appendices

1. Relevant National Port Policy - Documents Reviewed

2. SFPA Port Stats 2015

3. Concrete Trial Specification

4. Concrete Trial One Record Sheet Results - Gannon Eco

5. Concrete Trial Two Record Sheet Results - Inland & Coastal

The Netmap Project 2Executive Summary

It is clear that marine litter and in particular plastic Polyethylene, a lower value material, is more complex

pollution continues to ascend on the global agenda, to recycle. There appears to be an absence of recycling

as the realities of the harmful effects of plastic debris companies in Ireland that have a desire or are capable

and microplastic become apparent. Likewise, the of reprocessing discarded fishing nets. Due to the volume

problem of lost and abandoned fishing gear is now and weight of end of life nets, they are costly to transport

receiving attention on a global, European and to any recycling facilities in Europe that may be able to

national level, with policymakers, governmental reprocess the material. Some ports are then faced with

and non-governmental organisation lobbying for the accumulation of waste fishing nets on ports over

and implementing strategies to improve management a period of time, eventually causing a health and safety

of fishing nets, increasing recyclability and in the hazard and then needing to be removed by a waste

longer term protecting our environment. management company. However, BIM, in recent times,

have engaged with a number of ports to trial a recycling

The first section of this report introduces the Challenge programme for Polyethylene nets which be expanded

of Marine Plastics and Fishing Gear, exploring the relevant upon in the future.

International & National Policy governing the management

of end of life fishing nets and exploring the current Section Two examines potential solutions for waste fishing

situation as regards management of waste fishing nets in Ireland, centring around the potential for a Social

nets at Irish ports. Enterprise to obtain value from the waste stream and

then more specifically at potential applications within

In a national context, it appears evident that the specific the concrete industry. The number of enterprises and

management of waste fishing nets has not been provided organisations tackling waste fishing gear globally and

for in legislation or policy within the Irish statues nor their proven success, demonstrates the possibilities for

directly expressed in any of the port waste management such a venture in Ireland. It is clear that there are multiple

plans or in the bye-laws reviewed as part of this research. opportunities for Social Enterprise in collecting,

However reference has been made in the Fishing re-processing or reusing net materials for new products

Harbours Centres business strategy that the need for on a small scale local level. However the challenges

fishing net storage, repair and waste management should in the management of fishing nets as a waste material

be addressed. Ireland’s National Seafood Agency, should be also be acknowledged by groups or

Bord Iascaigh Mhara (BIM) have been working with organisations interested in embarking on a Social

a number of ports across the country to improve Enterprise in this area.

management of waste fishing gear, through various

schemes and projects, including the successful "Fishing Trials undertaken with the construction sector as regards

for Litter” initiative. Recent developments at EU level, the potential applications for waste fishing net materials

including the potentially transformative Plastics Strategy in concrete suggest comparative benefits on mortar

2018, coupled with specific measures on Port Reception strength when using waste fishnet fibres. However, it is

Facilities, Gear Marking and Producer Responsibility evident, that if a market was to emerge for waste fishing

Schemes are set to bring considerable positive change net fibres in the construction industry, investment would

in how waste fishing nets are managed, potentially be required to establish facilities suitable for re-processing

streamlining routes for re-processing, recycling and fishing net materials in Ireland.

reuse, allowing a wider 2nd life market for these

valuable materials. This report will serve as a useful starting point for both

social and commercial enterprises wishing to further

Discussions with management at Irish ports revealed that explore the potential for the reuse, the recycling and

the primary types of fishing nets used in Ireland include the reprocessing of waste fishing nets in an Irish context.

polyethylene and nylon netting. The latter does not

appear to be a problem when they come to end of life

due to robust recycling schemes in place coupled with

demand in Europe for this higher value nylon material.

The Netmap Project 3Introduction

Current research estimates approximately 8 million treatment, 3D printing and the construction sector, as well

tonnes of plastic enter our oceans each year, with the as providing expert guidance to SME’s on sustainable

Ellen McArthur Foundation citing there is likely to be more business. Through the Circular Ocean project, Macroom E

plastic than fish in our seas by 2050. The issue of marine gained substantial knowledge on the scale of the problem

plastics is of ever increasing international concern and and the intricacies surrounding management of end of life

is particularly pertinent to Ireland. As an island nation we fishing gear on an international level. It became apparent

have a marine area that is ten times the size of its land there was an opportunity to explore this further in an Irish

area above the sea, with the majority of our population context, specifically:

living within 50km of the ocean. The issues surrounding

marine plastic pollution continue to rise to the top of • How this waste stream is currently managed in

the environmental agenda both on the international and Irish ports, with a focus on the Cork region

national stage, most recently with the launch of the first • Would it be possible to gather data on the

ever EU Plastics Strategy in January 2018. volumes of waste fishing gear materials in Ireland

• Could we identify potential sustainable

Background to The NetMap Project applications for waste net materials, so that

The idea for this project emerged from the SMILE they can benefit coastal communities in which

Resource Exchange programme. A FREE service for they emerge, with a particular focus on the

businesses, SMILE encourages the exchanging of applications of waste fishing net fibres in the

resources between its members in order to save money, construction industry

reduce waste going to landfill and to develop new • Examine the potential of a Social Enterprise

business opportunities. Potential synergies are identified model to provide a community based solution,

through an online platform www.smileexchange.ie, which could potentially reap employment and

through the programme hotline or through facilitated economic advantages to rural communities,

technical assistance. SMILE is project managed by while addressing an environmental challenge

Macroom E (a wholly owned subsidiary of Cork County

Council) and is funded through a partnership between the Following a successful application to the EPA Green

Environmental Protection Agency, Cork County & Council, Enterprise Funding Call in 2016, research began on

the Southern Waste region and Local Enterprise Offices. the “NetMap” project in January 2017.

Through discussions with SMILE members, the significant

problem posed by waste fishing nets in Ireland

and internationally was highlighted as an area that

warranted further research.

Macroom E subsequently initiated an application to the

ERDF Interreg VB Northern Periphery and Arctic (NPA)

Programme for the Circular Ocean project, in conjunction

with University partners at the Environmental Research

Institute at North Highland College (Scotland), The Centre

for Sustainable Design (UK), The Arctic Technology Centre

(Greenland) and The Norwegian University of Science & The Seafood Industry in Ireland

Technology (Norway). The focus of the three year (2015- According to “Harnessing Our Ocean Wealth - An

2018) Circular Ocean project is to seek opportunities for Integrated Marine Plan for Ireland” (July 2012) “Taking our

recovery and reuse of waste Fishing Nets & Rope (FNR’s), seabed area into account, Ireland is one of the largest EU

with a view to benefiting local economies. states; with sovereign or exclusive rights over one of the

largest sea to land ratios (over 10:1) of any EU State. Our

Macroom E is the sole Irish partner and has responsibility ocean is a national asset, supporting a diverse economy,

for the Communications activities surrounding the project. with vast potential to tap into the global marine market for

Circular Ocean’s communications strategy centres around seafood, tourism, energy and new applications for health,

creating awareness of the detrimental environmental medicine and technology.

impacts of end of life fishing nets and rope, while inspiring

communities to divert waste fishing gear materials from The Marine Institute explain that “the waters around

our oceans and landfills for reuse, recycling and new Ireland contain some of the most productive fishing

product development. Circular Ocean will produce grounds and biologically sensitive areas in the EU.

progressive new data on the environmental impact of lost The main fish species caught are mackerel, horse

and abandoned FNR’s, lifecycle analysis and a barrier mackerel, boarfish, blue whiting, herring, cod, whiting,

assessment on mechanisms for better management. haddock, saithe, hake, megrim, anglerfish, plaice,

Partners are also investigating the potential applications sole and nephrops.”

of end of life fishing nets in areas such as wastewater

The Netmap Project 4According to the 2016 BIM Business of Seafood Report:

• Ireland’s Seafood Industry contributes

€1 billion in GDP to the overall economy and

represents 70% of the overall Blue Economy, • 6 Fishery Harbour Centres

valued at €1.4 billion • Managed by the Department for Agriculture,

• The industry employs an estimated 8,500 Fisheries & the Marine

people in full and part-time roles, rising to • Strong network of collaboration

11,000 when ancillary employment is included

• In 2015, sea fisheries landings (both Irish and

Foreign) into Ireland were valued at €344 million,

while aquaculture production was valued at

€148 million

• 50 Ports under management across 13

Ireland’s six major Fishery Harbour Centres (FHCs) are Local Authorities

run by the Department of Agriculture, Food & the Marine. • Follow individual Local Authority

From our research, it appears there is an established Waste Regulations

culture of networking and knowledge exchange amongst

harbourmasters in the FHC’s, as well as seemingly more

robust systems and structures for waste management.

There are an additional 40 secondary ports in the

Republic of Ireland, run by either local authorities or

a semi-state port companies. The number of smaller • 12 Commercial semi-state companies based in

harbours used by the inshore fleet is probably in excess ports with a commercial freight aspect

of 100, however, many of these are grouped together for • Some also manage smaller neighbouring

statistical purposes (e.g. in Cork, Skibbereen is an official fishing ports

landing port that encompasses a number of smaller piers). • Independent structure and waste

Most of these smaller harbours are only used over the management strategy

summer months by seasonal, usually pot fisheries. Most

of the larger vessels (in excess of 15m length) operate

from the Fishery Harbour Centres. However, some of the

non-fishery harbour ports account for increasingly larger

volumes of fish landings. The 2016 annual report by the

Licensing Authority for Sea Fishing Boats puts the number

of Irish Fishing vessels at 1,991 across all sectors.

The first section of this report introduces The Challenge

of Marine Plastics and Fishing Gear, exploring the relevant

International & National Policy governing the management

of end of life fishing nets and exploring the current

situation as regards management of waste fishing nets at

Irish ports. Section Two examines potential solutions for

waste fishing nets in Ireland, centring around the potential

for a Social Enterprise to obtain value from the waste

stream and then more specifically at potential applications

within the concrete industry.

References

• Harnessing Our Ocean Wealth – An Integrated Marine Plan for Ireland (July 2012) https://www.ouroceanwealth.ie/about-plan

• The Marine Institute – Areas of Activity – Fisheries & Ecosystems https://www.marine.ie/Home/site-area/areas-activity/fisheries-ecosystems/

fisheries-ecosystems

• “The Business of Seafood 2016 – A Snapshot of Ireland’s Seafood Sector” – BIM (2016) http://www.bim.ie/media/bim/content/pub lications/corporate-other-

publications/BIM-the-business-of-seafood-2016.pdf

• Licensing Authority for Sea Fishing Boats Annual Report (2016) https://www.agriculture.gov.ie/media/migration/seafood/seafisheries/fishboatlicencing/

AnnualReportEnglish190717.pdf

The Netmap Project 51. Overview 1.1 Fishing Gear 1.2 The Impacts of Lost & Discarded Fishing Gear 1.3 Marine Plastic Pollution in Ireland

1. Overview

Marine pollution is a major concern on a global scale, recycling. Due to it’s characteristically expansive size

with reports of millions of tonnes of litter ending up in and weight, fishing nets also prove to be a difficult

our oceans worldwide. Jambek et. Al estimate that more material to store and re-process mechanically.

than 150 million tonnes of plastics have accumulated Fishing gear proves a particular threat to our marine

in the world’s oceans, while 4.6-12.7 million tonnes are environments when lost or abandoned at sea, commonly

added every year. This scourge of plastic pollution on our referred to as “Ghost Gear”. Ghost Gear refers to any

coastlines is causing significant harm to our environment, fishing equipment or fishing-related litter that has been

our health and our economies, causing ever increasing abandoned, lost or otherwise discarded; also referred

concern and demand for action. to as ‘derelict fishing gear’ and/or ‘fishing litter’.

According to a 2018 report by World Animation Protection

“Ghost gears capacity to entangle, injure and kill hundreds

of species of marine animals on a large scale makes

it a serious concern requiring urgent action. Globally,

ghost gear hotspots differ in the types of gear they

contain, the original target species to be fished and the

currents that carry them, but is estimated to represent

10% of all marine debris.”

Case Study: Global Ghost Gear Initiative

A multi-stakeholder alliance committed to driving

solutions to the problem of lost and abandoned

fishing gear worldwide, the Global Ghost Gear

Initiative (GGGI) aims to improve the health of marine

ecosystems, protect marine animals from harm,

and safeguard human health and livelihoods.

Founded by World Animal Protection on the best

available science and technology, the GGGI is the

first initiative dedicated to tackling the problem of

ghost fishing gear at a global scale. The GGGI’s

strength lies in the diversity of its participants

Source: www.circularocean.eu including the fishing industry, the private sector,

academia, governments, intergovernmental and

As policymakers work to introduce legislation around non-governmental organisations. Every participant

the manufacture and use of certain single use plastic has a critical role to play to mitigate ghost gear

products, the focus has also been placed on the fishing locally, regionally and globally. The Global Ghost

gear, primarily produced from plastic materials but as of Gear Initiative have published a series of guidance

documents including a “Best Practice Framework for

yet, not widely recycled. Fishing gear can be particularly

Fishing Gear Management” and “Approaches to the

detrimental to our marine environmental when lost or Collection and Recycling of End-of-Life Fishing Gear”

abandoned at sea, left to continue to entangle and designed to assist those wishing to participate in

poison marine life for hundreds of years. ghost gear related projects.

In order to provide a basis for our research, this section Source: www.ghostgear.org

will provide an introduction to some of the problems

associated with the prevalence of waste fishing gear.

A 2016 Report from UNEP (United Nations Environment

Programme) reveals that “Due to the continued expansion

of the Aquaculture industry, the effects of the associated

1.1 Fishing Gear gear must also be considered in the context of marine

plastic pollution. Aquaculture structures are either

Due to its many advantages over more natural fibres, suspended from the sea surface or placed in intertidal

plastic has been the material of choice for most fishing and shallow subtidal zones directly on the bottom. The

gear within the commercial fisheries sector over the past majority of activities use lines, cages or nets suspended

number of decades. Undeniably resilient, plastic fishing from buoyant structures, often consisting of plastics (air-

nets may then be equipped with ancillary gear such as filled buoys), and EPS (expanded polystyrene). Aquaculture

lead weights, plastic buoys or combination rope, resulting structures are lost due to wear and tear of anchor ropes,

in a multi-material item which can be difficult to separate because of storms, and due to accidents/conflicts with

into individual materials/polymers for the purposes of other maritime users. Severe weather conditions can cause

widespread damage to aquaculture structures, at times

generating large quantities of marine debris.”

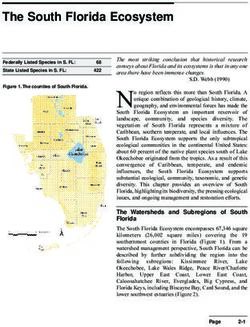

The Netmap Project 81.2 The Impacts of Lost

& Discarded Fishing Gear

Environment

According to research by Wilcox et al., “the entanglement

of marine animals in marine debris, especially derelict nets

and other abandoned fishing gear is widely recognised

as a major source of mortality. The findings of a report on

the impacts of pollution on marine wildlife, showed the 8 MILLION TONNES

single greatest impact from any item was predicted to

OF PLASTICS

GO INTO THE SEA EACH YEAR,

be entanglement of birds by fishing line and rope, with AMONG WHICH A LARGE

AMOUNT OF FISHING GEAR

expected lethal impacts on 25-50% of animals. Given

that fishing gear is intentionally designed to ensnare and IN FACT HOW DOES

capture fishing, it is expected that loss of intentionally THAT HAPPEN?

discarded gear would continue to ensnare both fish and 46%

OF THE GREAT

• ABRASION (broken plastics

bits get lost in the water)

other marine taxa, with considerable risk of death by GARBAGE PATCH

IS FISHING NETS

• VOLUNTARY ABANDONMENT

• ACCIDENTS

exhaustion or suffocation.” The report goes on to state

“when compared with other consumer items discarded 20% OF EU FISHING GEAR

IS LOST OR DISCARDED

AT SEA, WORLDWIDE THAT’S

in the ocean, fishing gear clearly poses the greatest 640 000 TONNES

ecological threat.”

EACH YEAR

27 % OF ALL

BEACH LITTER

COMES FROM FISHING GEAR

ONLY

1.5%

OF WORN OUT

FISHING GEAR

GET RECYCLED

Research undertaken by The Circular Ocean Project

state that “The desirable properties of plastics (low cost,

light weight, durable) are those that contribute to it being

problematic in the marine environment. Owing to its low THE IMPACT

density, a large proportion of plastic floats, increasing the THE ANIMAL

number of species that may interact with it, with potentially ENVIRONMENT WELFARE

SEAFLOORS ARE POLLUTED

negative consequences. Furthermore, it does not AND BIODIVERSITY DECREASES

GHOST FISHING

Marine life gets

CHEMICAL

CONTAMINATION

biodegrade, but instead breaks up into smaller fragments GLOBAL COST

OF MARINE LITTER

trapped in lost

fishing gear

has disruptive effects

on species

that remain in the environment.” TO MARINE ECOSYSTEMS

€10.7 billion

There are two main ways that plastic pollution HUMAN

effects marine species: HEALTH

Marine litter is a vehicle

for diseases and bacteria

• Entanglement – species become entangled in TOXICITY IN THE

FOOD CHAIN

lost for discarded fishing nets or other single

use plastics. Seabirds may also collect plastic THE

ECONOMY

as nesting building materials, often causing LESS € 630 1 TO 5% € 30

entanglement of chicks and adults, resulting TOURISM

due to dirty

MILLION

cost for

TOTAL MILLION

REVENUE LOSS cost for the navigation

in injury or death. beaches and

waters

cleaning up all

EU coasts

for the fisheries sector (damaged

& aquaculture sector equipment, accidents, etc.)

• Ingestion – individuals mistakenly consume

plastic debris, with potentially lethal side effects. EU ACTION

Recent estimates by Gall & Thompson (2015) indicate that EXISTING ACTION EXTENDED

The EU has already started

PRODUCER

over 690 marine species globally have been affected by addressing the problem

RESPONSIBILITY

marine debris, including cetaceans, pinnipeds, seabirds, target to

REDUCE

By making producers responsible for managing

plastic litter from fishing gear, we will:

turtles, fish and crustaceans, with the majority MARINE

LITTER BY UPDATED INTERNALISE

RULES ON PORT

involving plastic. 30% RECEPTION

THE ENVIRONMENTAL

COST OF MARINE LITTER

FACILITIES

ATTRACT

€ 53 MILLION INNOVATION FOR

FUNDING MORE SUSTAINABLE

through the European MATERIALS

Maritime and Fisheries Fund

(2014-2020) STIMULATE

THE RECYCLING

MANDATORY MANDATORY MARKET

MARKING RETRIEVAL

OF FISHING OR REPORTING HELP OUR

GEAR OF LOST FISHERMEN

FISHING GEAR

CHERISH THE

RESOURCES OF

OUR OCEAN

maritime affairs

& fisheries

Source: RSPB Cymru Source: Claire Fackler, NOAA Source: https://ec.europa.eu/fisheries/new-proposal-will-tackle-

National Marine Sanctuaries marine-litter-and-%E2%80%9Cghost-fishing%E2%80%9D_en

The Netmap Project 9Economy

In addition to the environmental impacts, lost or

abandoned fishing gear can have a significant negative

impact on the fishing industry. Continued “ghost fishing”

continually causes mortality of target species, ultimately

reducing the fishing stocks available to fisherman.

Lost and abandoned gear on or beneath the surface

of the water often become entangled in engines or

propellers, with fisherman incurring substantial repair

costs and loss of fishing time. UNEP estimate “The total

cost of marine litter to the EU fishing fleet has been

estimated to be nearly €61.7 million (Annex VII; Mouat

et al. 2010, Arcadis 2014).”

Tourism continues to play a vital role in Ireland’s

economy, with figures from the Irish Tourism Industry

Confederation showing the industry was worth an

estimated €8.7 billion in 2017. With Failte Ireland’s 2016

Tourism Review revealing that”overseas tourists listing

beautiful scenery and natural unspoilt environment as the

leading attractions to visit Ireland”, it is imperative that

our coastlines and marine environments are protected

against plastic pollution. Stockpiles of discarded fishing

nets at fishing ports can blemish picturesque coastlines,

diminishing the potential economic gain of tourism in

our coastal towns and villages. With recent international

publicity surrounding the level of microplastic in seafood

globally, Ireland maintains a reputation for premium quality A 2017 report on Seabirds & Marine Plastic Debris in

seafood, which is an added attraction to our shores for Ireland undertaken under the Circular Ocean project

culinary enthusiasts. reported that “The presence of plastics, particularly

micro-plastic is widespread in the North-eastern Atlantic

1.3 Marine Plastic with a mean of 2.46 particles m-3 There is no baseline

data for the levels of marine plastic in the seas around

Pollution in Ireland Ireland, however recent monitoring in the Celtic Sea

revealed that 57% of trawl samples contained litter, with

In the 2017 Coastwatch Survey, the most widely 84% comprising of plastic. Between 2012 and 2016, 93%

distributed litter item after plastic bottles was rope/ of 14 beached fulmars collected in Ireland were found

string, reported from 72% survey sites, while fishing and to contain ingested plastic, all exceeding OSPAR’s 0.1g

aquaculture waste was recorded in 42.8 % of survey units. EcoQO Level (Ecological Quality Objectives indicator).

When this figure was broken down, nets were seen in 148 It was noted that 69 seabird species were identified as

survey sites, aquaculture and angling gear in 67 and traps commonly occurring breeding species or migrants in

in 58. Results were obtained from 538 shore sections or Ireland, of these 17 species had been examined, with

‘survey units’ across the Republic of Ireland and checked 13 showing evidence of plastic ingestion. A further four

by Coastwatch volunteers at low water. species that had been studied showed no evidence of

plastic ingestion. For species where multiple samples

were available, the highest prevalence of plastic ingestion

occurred in the Northern Fulmar, consistent with other

studies which highlight that as surface feeders they are

highly susceptible to ingesting plastic fragments.”

The Netmap Project 10Source: www.circularocean.eu

A 2018 study led by the National University of Ireland in

1.4 Conclusion

Galway to quantify microplastic ingestion by mesopelagic While awareness of the issues surrounding marine plastics

(part of the pelagic zone that extends from a depth of has grown, so too has the scale of the problem, due to

200 to 1000 meters below the ocean surface) fish in the continued economic growth, particularly as the global

Northwest Atlantic, found that 73% of all fish contained demand for seafood continues to escalate. As many

plastics in their gut contents. Overall, the study found a organisations, groups and individuals continue working

much higher occurrence of microplastic fragments, mainly to explore systems to better manage end of life fishing

polyethylene fibres, in the gut contents of mesopelagic gear, it is essential to unearth the materials potential

fish than previously reported. Stomach fullness, species value as a resource for new products.

and the depth at which fish were caught at, were found

to have no effect on the amount of micro-plastics found

in the gut contents.

The international Ghost Fishing foundation in

collaboration with Ghost Fishing UK announced their

first Irish project in early 2018. The partnership with

Whale Watch West Cork and South West Technical Diving

will retrieve abandoned or lost fishing nets, fishing gear

and other marine debris from local wrecks and reefs,

while creating awareness of the problem by sharing

photos and films of the clean-up project. Subject to a

successful funding campaign, Phase One of the ghost

gear removal project was scheduled to take place in May

2018, whereby two divers will perform a reconnaissance

mission to identify specific target areas and pinpoint ghost

gear in preparation of the main team who will

start removing the gear later in the summer.

The Netmap Project 11References

• “Plastic Waste Inputs from Land into the Ocean” - Jenna R. Jambeck et al (2015) http://science.sciencemag.org/content/347/6223/768

• “Ghost Beneath the Waves – Ghost gears catastrophic impact on our oceans and the urgent action needed from industry” - World Animal Protection (2018)

https://www.worldanimalprotection.org.uk/campaigns/animals-wild/sea-change/ghosts-beneath-waves

• Global Ghost Gear Initiative https://www.worldanimalprotection.org/our-work/animals-wild/sea-change/our-work/gggi

• “Marine plastic debris and micro-plastics – Global lessons and research to inspire action and guide policy change” – UNEP (United Nations Environment

Programme), Nairobi (2016) https://europa.eu/capacity4dev/unep/document/marine-plastic-debris-and-microplastics-global-lessons-and-research-inspire-action-

and-guid

• “Using expert elicitation to estimate the impacts of plastic pollution on marine wildlife” - Wilcox et Al (2015) https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/

S0308597X15002985

• “Seabirds & Marine Plastic Debris in Ireland: A synthesis and recommendations for monitoring” – N O’Hanlon, NA. James, E. Masden & AL. Bond (2017)

http://www.circularocean.eu/research/

• “The Impact of Marine Debris on Marine Life” - Gall & Thompson 2015 https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0025326X14008571

• Irish Tourism Industry Confederation Year End Review (2017) http://www.itic.ie/YE17/index.html

• Failte Ireland Tourism Facts 2016 http://www.failteireland.ie/FailteIreland/media/WebsiteStructure/Documents/3_Research_Insights/2_Regional_

SurveysReports/Tourism-Facts-2016-Revised-March-2018.pdf?ext=.pdf

• Coastwatch Survey Results (2017) http://coastwatch.org/europe/wp-content/uploads/2017/12/Summary-results-2017-Coastwatch-Final.pdf

• “Frequency of Microplastics in Mesopelagic Fishes from the Northwest Atlantic” – Wieczorek, Alina M.; Morrison, Liam; Croot, Peter L.; Allcock,

A. Louise; MacLoughlin, Eoin; Savard, Olivier; Brownlow, Hannah; Doyle, Thomas K. (2018) https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmars.2018.00039/full

The Netmap Project 122. Relevant International & National Policy 2.1 International Policy 2.2 National Policy

2.1 International Policy

The following section outlines some of the international The effectiveness of ships to comply with the discharge

legislation that may directly or indirectly regulate requirements of MARPOL depends largely upon

management of end of life Fishing Nets, Ropes & the availability of adequate port reception facilities,

Components (FNRC’s). In some cases, the policy is especially within special areas. Hence, the Annex

categorised under the subject of marine pollution also obliges Governments to ensure the provision of

or ocean plastics, but ultimately encompasses FNRC adequate reception facilities at ports and terminals for

materials, which are predominantly plastic based. the reception of garbage without causing undue delay to

ships, and according to the needs of the ships using them.

UN Sustainable Development Goals However, according to MARPOL, vessels smaller than 100

Launched in 2015, the UN’s 17 Sustainable Development gross tons and carrying fewer than 15 persons are exempt

Goals (SDG’s) were designed to shape the global from a number of regulations. This exemption means that

agenda on sustainable development until 2030. a large proportion of fishing boats are exempt from many

Goal 14 “Life Below Water” is particularly pertinent to of MARPOL’s stringent waste handling regulations.

management of end of life gear and was implemented

“to conserve and sustainably use the oceans, seas and FAO Voluntary Guidelines

marine resources for sustainable development.” SDG on Marking Fishing Gear

14.1 requires a significant reduction of marine debris by In February 2018, the Food & Agricultural Organisation

2025, citing “Careful management of this essential global (FAO) of the United Nations announced a draft set of

resource is a key feature of a sustainable future.” Voluntary Guidelines on Marking Fishing Gear.

The guidelines will “help countries to develop effective

While SDG 12 aims to “Ensure sustainable consumption systems for marking fishing gear so that it can be traced

and production patterns”, stating that by 2030 overall back to its original owner. Doing so will support efforts

waste generation must be significantly reduced through to reduce marine debris and its harmful impacts on the

prevention, reduction, recycling and reuse. marine environment, fish stocks, and safe navigation.

It will also allow local authorities to monitor how

fishing gear is being used in their waters and who is

using it, which makes them an efficient tool in the fight

against illegal, unreported and unregulated (IUU) fishing.”

Considering the worldwide scale of the problem of

lost and abandoned fishing gear in our oceans, “the

Guidelines are global in scope, but countries recognize

that making them work for small-scale fisheries in

developing countries will require additional support

to meet the new standards.” It is expected that the

guidelines will receive final endorsement by FAO’s

Committee on Fisheries in July 2018.

Source: www.un.org

UNEP (UN Environment)

MARPOL 73/78 Regional Sea Programme

The International Maritime Organization (IMO) developed The objective of the UNEP Regional Seas Programme

the MARPOL 73/78 Annex V as a major international is “to address the accelerating degradation of the

instrument that addresses ocean-based litter pollution world’s oceans and coastal areas through a “shared

from ships. Overall, this instrument bans discharge of all seas” approach, by engaging neighbouring countries

garbage from ships at sea with the exception of only a few in comprehensive and specific actions to protect their

defined circumstances. A recently revised Annex V sets common marine environment.” More than 143 countries

a framework for managing garbage generated by ships. have joined 18 Regional Seas Conventions and Action

Ships >100 GT or ships certified to carry >15 passengers Plans for the sustainable management and use of the

are required to provide a Garbage Record Book (GRB), marine and coastal environment. In most cases,

which is meant to record all discharge of garbage made the Action Plan “is underpinned by a strong legal

at both sea and reception facility. MARPOL Annex V also framework in the form of a regional Convention and

requires vessels to log the loss of any fishing gear by associated Protocols on specific problems.” Ireland

recording where the gear was lost, the characteristics is a contracted party of the North East Atlantic

of the lost items and which precautions were taken to programme, under the OSPAR Commission.

prevent the loss.

The Netmap Project 14OSPAR Convention for Prevention of Pollution from Ships (MARPOL 73/78)

OSPAR is the mechanism by which 15 Governments and associated regulations. In addition, the application of

(including Ireland) & the EU cooperate to protect the the Code of Conduct for Responsible Fisheries, support of

marine environment of the North-East Atlantic. the Responsible Irish Fish initiative, and implementation of

The objective of OSPAR objective in respect of marine the Fishing for Litter scheme, are measures engaging the

pollution is “to substantially reduce marine litter in the fishing industry in tackling marine litter.”

OSPAR maritime area to levels where properties and

quantities do not cause harm to the marine environment” EC Directive on Port Reception Facilities

by 2020. In order to achieve this, the North East for the Delivery of Waste from Ships

Atlantic Environment Strategy also commits to “develop Directive 2000/59/EC on port reception facilities for ship

appropriate programmes and measures to reduce generated waste and cargo residues aligns EU law with

amounts of litter in the marine environment and to the international obligations provided in the MARPOL

stop litter entering the marine environment, both Convention. The Directive’s main aim is “to reduce the

from sea-based and land-based sources”. discharges of ship-generated waste and cargo residues

into the sea, thereby enhancing the protection of the

To fulfil this objective OSPAR agreed a Regional Action marine environment. As such, the Directive is a key

Plan for Marine Litter for the period 2014-2021. The plan instrument for achieving a Greener Maritime Transport,

contains “55 collective and national actions which aim to as set out in the Commission’s Communication ‘Strategic

address both land based and sea based sources, as well goals and recommendations for the EU’s maritime

as education and outreach and removal actions. The key transport policy until 2018’, which includes among its

action areas relating to waste fishing gear include Port recommendations a long term objective of ‘zero-waste,

Reception Facilities, waste from fishing industry, fines for zero-emissions’. The Directive is also the main EU

littering at sea, the Fishing for Litter initiative, abandoned legal instrument for reducing marine litter from sea-

and lost fishing gear and improved waste management.” based sources in line with the 7th Environmental Action

Programme and international commitments made by the

EU Marine Strategy Framework Directive EU and its Member States.”

The Marine Strategy Framework Directive requires

European member states to “reach good environmental The PRF Directive requires ports to meet the following

status (GES) in the marine environment by the year requirements: ports must develop and implement a waste

2020 at the latest”. Good environmental status in the reception and management plan, require waste deliveries,

marine environment means that the seas are clean, implement a type of cost-recovery system and establish

healthy and productive and that human use of the marine a system for enforcement. Ship owners are required to

environment is kept at a sustainable level. Under the notify ports of waste deliveries in advance. Member states

directive, marine waters must be assessed against an are to ensure that costs of waste handling at ports are

agreed set of standards across a number of important recovered through fees charged to the ships. All ships

environmental areas.” calling at an EU port must pay a fee irrespective of their

actual use of the facilities. This is called an “indirect fee”

Ireland has been working on the implementation of versus a “direct fee” where payment is based directly

the MSFD and development of a strategy for Ireland’s on use/services. These indirect fees should provide a

marine waters since the Directive was transposed into “significant” part of the port’s waste handling fees. This

Irish Law in 2011. “The first steps in the implementation “significant” amount has been defined as at least 30% of

of the MSFD in Ireland was the undertaking of an Initial the total cost of ship waste handling. Some fishing and

Assessment of Ireland’s marine waters, the definition recreational vessels are exempt depending on the size.

of the characteristics of GES for each of the eleven

descriptors and the establishment of a comprehensive Member States are relying increasingly on the MARPOL

set of environmental Targets and Indicators to guide framework, making implementing and enforcing the

progress towards achieving GES. This step was followed Directive problematic. In addition, Member States apply

by the establishment and implementation of coordinated different interpretations of the Directive’s main concepts,

monitoring programmes for the on-going assessment creating confusion among ships, ports and operators.

of the environmental status of marine waters.” Consequently, a 2018 proposal for revision of the directive

aims to achieve a higher level of protection of the marine

According to a summary report released by the environment by reducing waste discharges at sea, as well

Department of Environment, Community and Local as improved efficiency of maritime operations in port by

Government in 2016 “For sea-based sources of litter reducing the administrative burden and by updating the

Ireland’s marine strategy focuses on the implementation regulatory framework.

of measures through existing legislation and international

agreements and industry based initiatives. Marine

litter-related measures are included in the Foreshore

and Dumping at Sea (Amendment) Act (2009), EC Port

Reception Facilities Directive, the International Convention

The Netmap Project 15EU Control Regulation EU Plastics Strategy 2018

Article 8 of the EU Control Regulation (EEC) (no. 2847/93) The first ever Europe-wide strategy on plastics was

provides detailed rules for fishermen to mark and announced in January 2018, is a part of the transition

identify their fishing vessels and gear. These rules came towards a more circular economy. It will protect the

into force in 2005 and apply to passive gear such as environment from plastic pollution whilst fostering growth

gillnets, entangling nets, trammel nets, drifting gillnets and innovation, turning a challenge into a positive agenda

and longlines. These detailed regulations require gillnet for the Future of Europe. There is a strong business

fishermen to mark each piece of gear and also use case for transforming the way products are designed,

intermediary buoys. produced, used and recycled in the EU and by taking

the lead in this transition, we will create new investment

EU Action Plan for the Circular Economy opportunities and jobs. Under the new plans, all plastic

The EU Circular Economy package includes legislative packaging on the EU market will be recyclable by 2030,

proposals on waste, with long-term targets to reduce the consumption of single-use plastics will be reduced

landfilling and increase recycling and reuse. The targets and the intentional use of micro-plastics will be restricted.

should lead Member States gradually to converge on best

practice levels and encourage the requisite investment in To reduce discharges of waste by ships, the Commission

waste management. Further measures are proposed to is presenting together with this strategy a legislative

make implementation clear and simple, promote economic proposal on port reception facilities. This presents

incentives and improve extended producer responsibility measures to ensure that waste generated on ships

schemes. This action plan will be instrumental in reaching or gathered at sea is delivered on land and adequately

the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) by 2030, in managed. Building on this, the Commission will also

particular Goal 12 of ensuring sustainable consumption develop targeted measures for reducing the loss or

and production patterns. By stimulating sustainable abandonment of fishing gear at sea. Possible options

activity in key sectors and new business opportunities, to be examined include deposit schemes, Extended

the plan will help to unlock the growth and jobs potential Producers Responsibility schemes, recycling targets

of the circular economy. and incentive schemes for the collection of discarded

fishing gear. The Commission will also further study

To raise levels of high-quality recycling, the plan seeks the contribution of aquaculture to marine litter and

harness improvements in waste collection and sorting. examine a range of measures to minimise plastic loss

Collection and sorting systems are often financed in from aquaculture.

part by extended producer responsibility schemes, in

which manufacturers contribute to product collection The commission will continue its work to improve

and treatment costs. In order to make these schemes understanding and measurement of marine litter,

more effective, the Commission is proposing minimum an essential but often neglected way to support effective

conditions on transparency and cost-efficiency. Member prevention and recovery measures. The strategy will

States and regions can also use these schemes for support member states on the implementation of their

additional waste streams. In order to achieve high levels programmes under the Marine Strategy Framework

of material recovery, the plan aims to send long-term Directive, including the link with their waste/litter

signals to public authorities, businesses and investors, management plans under the Waste Framework Directive.

and to establish the right enabling conditions at EU level,

including consistent enforcement of existing obligations. In order to harness action on a global scale, the strategy

includes actions in support of multilateral initiatives on

A number of sectors face specific challenges in the plastic, such as renewed engagement on plastics and

context of the circular economy, because of the marine litter on for a such as the UN, G7, G20,

specificities of their products or value-chains, the MARPOL convention and regional sea conventions,

their environmental footprint or dependency on material include the development of practical tools and specific

from outside Europe. These sectors need to be addressed action on fishing and aquaculture.

in a targeted way, to ensure that the interactions between

the various phases of the cycle are fully taken into account Europe has examples of successful commercial

along the whole value chain. Increasing plastic recycling partnerships between producers and plastics recyclers

is essential for the transition to a circular economy. The (e.g. in the automotive sectors), showing that quantity

use of plastics in the EU has grown steadily, but less than and quality issues can be overcome if the necessary

25% of collected plastic waste is recycled and about 50% investments are made. To help tackle these barriers, and

goes to landfill. Large quantities of plastics also end up before considering regulatory action, the Commission is

in the oceans, and the 2030 Sustainable Development launching an EU-wide pledging campaign to ensure that

Goals include a target to prevent and significantly reduce by 2025, ten million tonnes of recycled plastics find their

marine pollution of all kinds, including marine litter. way into new products on the EU market. To achieve swift,

Smarter separate collection and certification schemes tangible results, this exercise is addressed to both private

for collectors and sorters are critical to divert recyclable and public actors, inviting them to come forward with

plastics away from landfills and incineration into recycling. substantive pledges by June 2018.

The Netmap Project 16The Commission is committed to working with the

European Committee for Standardisation and the industry

to develop quality standards for sorted plastic waste and

recycled plastics. These standards will help combat the

misgivings of many product brands and manufacturers,

who fear that recycled plastics will not meet their needs

for a reliable, high-volume supply of materials with

constant quality specifications.

Awareness Campaigns, measures to prevent marine

littering and projects to clean up beaches can be set up

by public authorities and receive support from EU Funds.

May 2018 – European Commission Proposal

will tackle marine litter and “ghost fishing”

A further directive was proposed in May 2018 to target

the reduction of the impact of certain plastic products

on the environment. The directive sets specified

targeted actions for member states in respect of the

10 single-use plastic products most often found on

Europe’s beaches and seas, notably the directive also

includes lost and abandoned fishing gear. With its

proposal, the Commission will encourage all actors

involved to get a maximum of derelict gear back to

shore and include it in the waste and recycling streams.

In particular, producers of plastic fishing gear will be

required to cover the costs of waste collection from

port reception facilities and its transport and treatment,

as well as the cost of awareness-raising measures.

This new measure builds on existing rules such as the

Marine Strategy Framework Directive and complements

other actions taken against marine pollution, such as

under the Port Reception Facilities Directive.

Up to now, ports have been able to charge fishermen

for bringing retrieved abandoned, lost or disposed of

fishing gear ashore over and above their normal fee.

The Commission’s proposal to revise the Port Reception

Facilities Directive removes this disincentive. However,

ports’ costs for expanding facilities and running them

could find their way back into the port fee; thus

increasing the overall cost for fishers.

This proposal aims to close the loop by adding

Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR) schemes to

the existing measures. This will ensure that managing

fishing gear plastic litter, once it has arrived on shore, is

the responsibility of the producers. Thereby reducing port

costs for fisherman, particularly in small fishing ports, and

it will accelerate the development of a dedicated waste

stream for fishing gear waste. The proposal will now go

to the European Parliament and Council for adoption.

See Image on Page 18

The Netmap Project 17Source: https://ec.europa.eu/fisheries/new-proposal-will-tackle-marine-litter-and-%E2%80%9Cghost-fishing%E2%80%9D_en

The Netmap Project 182.2 National Policy

This section summarises the Irish waste legislation The SPA Act requires all ships to have adequate storage

relevant to harbours authorities managing marine waste, facilities on the vessels to store oil, harmful substances,

with particular focus on any legal provisions or guidance swage and garbage on board, so as to prevent

for the management of waste fishing nets and fishing gear unauthorised disposal into the sea. This is inspected

in Irish harbours. by Harbour officers, and inadequate storage facilities

on the vessel are an offence under the Act.

There are varying management structures in Irish

harbours including Port Company managed harbours, Whilst there are clear definitions in the Act relating to

Local Authority Harbours and Fishery Harbour Centres. discharge and garbage, fishing nets and fishing gear are

Reference to waste management in relation to general not specifically mentioned, nor does the Act set out an

waste and specifically to the management of waste exception in terms of size or capacity of the vessel.

fishing gear and nets across these harbour categories

was investigated. The Dumping at Sea Act, No.14 of

1996 to 2016, (as amended)

The information presented in this section was attained The Dumping at Sea Act, 1996 gives effect in Ireland to

by carrying out desk research across relevant websites the OSPAR Convention, which sets out applications for

including the Irish Statute Book permits to allow certain controlled dumping at sea, (i.e.

http://www.irishstatutebook.ie/; the Department of dredging materials). The Act does not directly mention

Transport, Tourism and Sport website, which includes fishing nets or fishing gear, however makes clear under

Irish Maritime Administration, (http://www.dttas.ie/maritime) Clause 2 that where any vessel, substance or material is

as well as Local Authority and Port Harbour websites. dumped in a maritime area , shall be guilty of an offence

Contact was made with stakeholders in the maritime under the Act. There are specific permits that can be

sector and conversations with representatives of the granted for dumping but do not include vessel garbage.

waste management sector were taken into account. The amendment Act 2009 provides for certain functions

of permitting to be managed by the Environmental

Sea Pollution Act, No 27 Protection Agency.

1991 to 2006 (as amended)

In Ireland, MARPOL 73/78 (as detailed in previous The Waste Management Acts

section) has been enacted by the Sea Pollution Act 1991 1996 to 2017 (as amended)

(No.27 of 1991), (“SPA”) which has been amended several The Waste Management Acts 1996 to 2017 (“WMA”)

times up to 2006. To give full effect to the purpose of define waste as any substance or object which the holder

the Act, the Minister for Transport, Tourism and Sport, discards or intends to discard or is required to discard.

with responsibility for Maritime Administration, has the

power to make Regulations under this Act to prohibit Materials meeting the requirements of By-products are no

and regulate the discharge of garbage at sea from Irish longer classed as waste and the decision when waste can

registered vessels and within Irish waters. This includes cease to be waste, having undergone a recovery process,

the sea disposal of fishing nets and fishing gear. Anyone has been clarified.

found contravening such Regulations shall be guilty of

an offence under the Act. (Relevant Regulations made There are certain categories of waste which involve

under this Act include S.I. No. 372/2012 - Sea Pollution additional duties or controls, including hazardous waste,

(Prevention of Pollution by Garbage from Ships) Regs waste oils, bio-waste, batteries, tyres, end-of-life vehicles

2012. – see below for details). and waste electrical and electronic equipment (“WEEE”).

The SPA Act does not specify any exemptions, so the Storage of Waste

Regulations enacted under this Act may relate to ships Certain waste can be stored on a temporary basis for up

generally or to any class of ship, to substances generally to six months, provided that a certificate of registration

or any description of substance, and be made subject is obtained. The original waste producer or other waste

to such conditions and such exemptions as may be holder must be authorised to dispose of waste and must

prescribed in the Regulations. carry out the treatment of the waste in accordance with

the waste hierarchy and so as not to cause or facilitate

If facilities for disposal of waste are inadequate in a the abandonment or dumping of waste or the transport,

harbour the Minister for Transport, Tourism and Sport, recovery or disposal of that waste in a manner that causes

with responsibility for Maritime Administration, or is likely to cause environmental pollution.

may, by Regulation, make provision for such discharge

or disposal options to be made available.

The Netmap Project 19Transfer of Waste The Regulations place requirements on harbour

The WMA places a duty on a waste producer/holder to authorities and persons having control of a harbour to

only transfer waste to an “appropriate person”, which is provide adequate facilities at ports and terminals for the

a person authorised to undertake the collection, recovery reception of garbage. The Minister for Transport, Tourism

or disposal of the class of waste in question. After the and Sport, with responsibility for Maritime Administration,

waste is transferred, the person who has taken possession can notify the International Maritime Organisation where

of the waste becomes the waste holder and takes on the facilities provided under the regulations are alleged

liability for that waste. to be inadequate. Schedule 1 of the regulations provide

a format for reporting alleged inadequacies of port

The Act does not apply to the dumping of waste at sea, as reception facilities.

defined within the Dumping at Sea Act 1981 (No. 8 of 1981)

which was repealed and incorporated into the Dumping at The regulations specify that:

Sea Act 1996-2016 (as amended). All vessels of 12 meters and longer shall display placards

and notify the crew & passengers of requirements under

S.I. No. 372/2012 - Sea Pollution (Prevention of the S.4 (General Prohibition to dispose Garbage at Sea)

Pollution by Garbage from Ships) Regs 2012 S.5 (Animal Carcasses or food waste may be disposed

These Irish Regulations enacted under the Sea Pollution of more than 12 nautical miles from the coast) and S.6

Act 1991 (No 27 of 1991) give effect in Ireland to Annex V (food waste may be disposed more than 3 nautical miles

to the MARPOL Convention (as detailed in previous from land and 500 m from other floating platforms if

section). Annex V means the revised Annex V to the ground-up to less than 25mm particles), and S.7 (stricter

MARPOL Convention as set out in Resolution MEPC.201 conditions for discharge of food waste and residues in

(62) of the Marine Environment Protection Committee of seas designated as Special Areas).

the International Maritime Organization. These Regulations

revoked the Sea Pollution (Prevention of Pollution by All vessels above 100 tons gross tonnage or carrying

Garbage from Ships) Regulations 1994 (S.I. No. 45 of 1994); 15 persons or more shall comply with the regulations

Amendment Regulations 1997 (S.I. No. 516 of 1997); and by carrying a Garbage Management Plan, which

Amendment Regulations 2006 (S.I. No. 239 of 2006). specifies procedures for storing, processing and

disposing of garbage.

The Regulations apply to all Irish ships regardless of

location on National or International waters, and to all The ships above 400 tons gross tonnage or with 15

other ships when they are in the territorial seas and or more persons shall also maintain a Garbage Record

inland waters of the Irish State. Book in which every garbage disposal or completed

incineration is logged.

The purpose of the Regulations is to prohibit and control

the disposal of garbage into the sea in accordance with The Regulations:

specific requirements for different types of garbage for

disposal (i.e. food waste) and the geographical location • Sets out definition for “Fishing Gear”- means

of the ship (distance to shore). They also provide for the any physical device or part thereof or combination

requirement of availability of adequate waste facilities of items that may be placed on or in the water or

at ports and terminals for the reception of garbage. on the sea-bed with the intended purpose of

In addition, the Regulations include requirements for capturing, or controlling for subsequent capture

certain ships to have Garbage Management Plans or harvesting, marine or fresh water organisms;

and to carry Garbage Record Books. • Definition of “Garbage” includes waste fishing

gear and all plastics -further defined as all

These Regulations apply to all ships which are defined as; garbage that consists of or includes plastic in any

form, including synthetic ropes, synthetic fishing

• A vessel of any type whatsoever operating in nets, plastic garbage bags and incinerator ashes

the marine environment and includes hydrofoil from plastic products

boats, aircushion vehicles, submersibles, floating • Includes fishing gear in plastic waste to be

craft and fixed or floating platforms and includes disposed of

fixtures, fittings and equipment • S. 4. General Prohibition of disposal of garbage

at sea includes fishing gear–

The Regulations make provision for the prohibition • Accidental loss of fishing gear at sea that poses

of the discharge of all garbage into the sea, there are a significant risk to the marine environment

some exceptions in relation to food wastes. It prohibits must be reported to authorities

the discharge into the sea of all plastics, including but • The Garbage Book requirements includes waste

not limited to synthetic ropes, synthetic fishing nets, fishing gear as item ‘I’.

plastic garbage bags and incinerator ashes from plastic

products is prohibited. The discharge into the sea of all plastics, including but

not limited to synthetic ropes, synthetic fishing nets,

plastic garbage bags and incinerator ashes from plastic

products is prohibited.

The Netmap Project 20You can also read