Memory for Pictures: A Life-Span Study of the Role of Visual Detail

←

→

Page content transcription

If your browser does not render page correctly, please read the page content below

Memory for Pictures: A Life-Span Study

of the Role of Visual Detail

Kathy Pezdek

The Chremont Graduate School

PEZDEK, KATHY. Memory for Pictures: A Life-Span Study of the Role of Visual Detail. CHILD

DEVELOPMENT, 1987, 58, 807-815. This experiment assessed the effect of the amount of physical

detail in pictures on picture recognition memory for 7-year-olds, 9-year-olds, young adults, and older

adults over 68. Subjects were presented simple and complex line dxawings, tactorially combined in

a "same-different" recognition test with simple or complex forms of each. For each age group,

recognition accuracy was significantly higher for pictures presented in the simple dian in the

complex form. This eflfect was due to diflferences between simple and complex pictures in the

correct rejection rate but not die hit rate; subjects were less accurate detecting deletions fix>m

changed complex pictures than addithns to changed simple picitures. The older adults were no

better than chance at correctly rejecting changed complex pictures. Altfiou^ increasing the presen-

tation duration from 5 sec to 15 sec increased overall accuracy, it did not increase subjects' ability to

correctly reject changed complex pictures. Results are interpreted in terms of schematic encoding

and storage of pictures. Accordingly, visual information that communicates the central schema of

each picture is more likely to be encoded and retained in memory than information diat does not

communicate this schema.

Individuals have an impressive ability to tures. This procedure thus tests how well sub-

remember pictures they have seen before. jects can distinguish pictures they have seen

This has been demonstrated with recognition from picjtures they have not seen, and they

tests (Nickerson, 1965; Shepard, 1967; Stand- can do this quite well. What we do not leam

ing, Conezio, & Haber, 1970) as well as with from these studies, however, is how much of

recall tests (Bousfield, Esterson, & Whit- the visual detail in a pic^ture has been re-

marsh, 1957). In addition, a number of devel- tained in memory when a picture is recog-

opmental studies have reported increases nized. The present study examines this partic-

with age, from childhood to early adulthood, ular aspect of picture memory and tests for

in recognition memory for large nxmibers of qualitative differences in these processes

pictures (Hofi&nan & Dick, 1976), recall and with age.

recognition for visual objects (Dirks &c Neis-

ser, 1977; Mandler, Seegmiller, 6E Day, 1977), We initially addressed this issue in an

and face-reex)gnition memory (Blaney fie earlier study from our laboratory (Pezdek &

Winograd, 1978). However, few of these stud- Chen, 1982). In this previous study, 7-year-

ies have examined qualitative developmen- olds, 9-year-olds, and young adults were pre-

tal differences in picture memory. In other sented simple and complex line elrawings of

words, are adults and older chilciren process- scenes. The simple and cK)mpIex forms of

ing pictures differently than younger chil- each picture contained the same c^entral infor-

dren, or are they just performing the same mation, but peripheral details, shading, and

processes better? embellishment were added in the complex

form of each pic^re. These pictures were se-

In typical picture recognition memory lected from the set of pictures utilized by Nel-

studies, subjects are presented a series of pic- son, Metzler, and Reed (1974) and originally

tures to remember and are then presented a constructed by Nickerson (1965). At test, pic-

test that includes some of die "old" pictures tures were presented one at a time in a

and some "new," distractor pictures. In the "same-different" recognition test Half of the

large majority of these studies, the "new," simple and complex line elrawings were

distractor pictures are completely new pic- tested in the same form as presentation; half

This research was conducted while die author was supported by a grant from the National

Institute of Education. I especially thank Sidney Fox for collecting the data for diis study and Tom

Dougherty fbr analyzing the data, and I appreciate conceptual contributions and feedback on die

manuscript provided by Ruth Maki. Requests for reprints should be sent to Kathy Pezdek, Depart-

ment of Psychology, The Claremont Craduate School, Claremont, CA 91711.

[Child Development, 1987,58, 807-815. © 1987 by tfie Society for Research in Child Etevelopment, Inc.

All rights reserved. 0009.3920/87/5803-000S$01.00]808 d f l d Development

were changed picUires. The changed test pic- 1969; Tverricy & Shrarman, 1975) as w ^ as for

tures were arrived at by chan^s^ tiie pictures &ces (Lffi^«y, Alexander, & Lane, 1971)

that had been presented in a simple form to increases w£th preseHiitation time and tfut ike

tiie complex form of tibe same picture and beneSts of incireased presenl^fm tlo^ are

changing pictures that had been presented in greater for yovrag c ^ & e n Aao for older c ^ -

a complex form to tiie simple form of tiie same dren and acblts ( H B ^ Mcairison, & Shein-

picture. gold, 1970; Naus, Omstein, & Mvano, 1977;

Pezdefc & Mlceli, 19^). Seven-year-olds and

The piincipal result of Pe2Kiek and Chen 9->^a'"0lds were included in the pre^nt

(1982) was tbat for adults, recx^Eiitlon sen- study for cOTi^Mn^^ay wifli the P e z d ^ and

sitivity, meastcred in terms of d', was grei^r Chen (19^) stucb' and, al«), bec»ise previ-

for pictures in tiie simple than in tiuf C(^ d& ^ l

preseirtation condition. However, for 7-i

olds and 9-yeaiHklds, recxignltion sensUJ , . f^E»Uy scun pk^uw

measured in temis of d', was similiB- for pic- cale atl^tlcm to central versus

tures in the ^ns^effiEidccm^^fix p^es^rarttttion cJbbOls (see Goo^ban, 1S80;

condition. 'Hus finding is in maslced cffliferast & Bruner, 1970; V « « | ^ t , 19

to Reese's (1970) hypothesis tiiat reteatitm of & present study ioduded a

visual stimi^ should be posi^vdy rektedl to l k , haa^ on recent &

the amount (^ dBtf^ in &e ^mali. It is ako also b e o ^ more Aan

inconsistent witii studies that have repeated ger adiiAs &(»Q iacrettsed Tgs^Beao^0^im

superior recall for compl«£ over simple pic- on meoHiry t a ^ (Cza& & BiS^nowUz, 1985;

tures (Bevan & Steger, 1971; Evertson & Wingfield, Pooa, Unnbrnxli, & Lowe, 1965).

Wicker, 1974) or no difierence between

aduhs* recognition ctf uix^le and comidex^c-

tures (Nelson et al., 1974). life span were u ^ s e d in Ms s t e ^ to test if

dS hiomn to ^dst in

pictures.

on the above s p ^ S ^ cliSf^Qces between

the test items used by P e a ^ and Oran and In tiie present study. 7-year-old8,9-year-

those used in odi» studies. That is, Pe^ek adMte (coAei^ stadente), toid

and Chen utilized test |^c;tures v/iHk &e same

centxal iafom^rtion as i^ctiues presented, but jprocedkire c^ized hy Pezeiek md Chen

with added or deleted elabor^ve viswil de- ~), w ^ iHesectation time per ^ d u r e

t ^ s . This study thus speeifically tested mem- . .jen sd:^oete. Tbe |H»lHg#*UHi

ory for the visual di^ails in pfctaires thai re- ut^xdhy P e z M and C&en ( I M ) was

tained the same thematic ctmtwat in their 8 sec per pctuie. In the iseBcait ^&^, each

simple and comi^^ forms. Aj^paready, ^ten, picture was pvescmUtd for 5 (»• 15 sec. If the

faults' ability to cSiscrimuof^ same &om 3es in i8co®^tion taemnixy for

changed simple pictures is gr^^a: 6utQ their jf^^alev^ctiu:^ lepotted^ Pez-

ability to discriminate swne feom and C3ien Jl^Z) are in paA chie to age

r— r—--—. *• 1. J v«««erences intbe speedof ei«x»lte®U!fiMana-

to discrinikiate same nom c^bai^ed plcte^es ^^^^ ^ ^ ^ mwii^l^faaiE pn^ntttttbn ^Eoe in

was similar for simile wid conqcHex jrfctures. ^^ present ^udy ^ouM resiA in s u u i ^ pat-

The puipose of tiie present study was to tems erf r e s i ^ among age ffotps ^ ^

farther p r c ^ the quiaiiidive deferences be- slower pres^rtOtJon time but not at tiie faster

tween Euhilts and c^dren in recc^p^tion

memory for visual deteils in pU±iu%s. This

study tested tiie hypt^esis ti^ tbe e^ differ-

ences reported by PezcJ^ and CSien (1982) S v i ^ e c t s . — V c a t y sufcg p ^ ^

could be accounted for by cHififei'raices in tiie eachKathy Pezdek 809

They ranged in age from 68 to 90 (M = 80.2 sentation pictures. The 11 changed versions

years, SD = 4.52), were generally well of simple presentation pictures were tiie

educated (M = 17.4 years of education, SD = complex versions of these pic:tures. The 11

3.4), and were amply healthy to live self- changed versions of the complex presenta-

sufiiciently. In each age group approximately tion pic^res were the simple versions of

equal numbers of males and females partici- these pictures. Thus, each of tiie 44 presenta-

pated in each condition, but gender was not tion pic*ires was included onc« in the test

si)ecifically controlled for. phase, in eitiiar the same or changed form.

Design.—All subjects viewed simple and In the tBSt phase, subjects viewed pic-

complex line drawings in the presentation tures one at a time at a rate controlled by tiie

phase and were tested with same and experimenter. For each pic;ture the experi-

changed forms of these pictures. Twenty sub- menter asked, "Is this picture the same as a

jects in each age group were presented the picture you saw before, or are there some

pictures at a duration of 5 sec each, and 20 changes in this picture?" Several practice

were presented the pictures at a duration of slides were shown first to ensure that subjects

15 sec each. The study can thus be described understood what types of changes c:onstituted

a s a 4 x 2 x 2 x 2 mixed &ctorial design changed test items. The assignment of each

with age and presentation duration as be- picture to conditions of presentation and test

tween-subjects factors and presentation form and the sequencing of presentation and test

and test form as within-subjects Victors. slides were arranged in two orders. Half of

the subjects in each condition were randomly

Materials.—The materials were the same assigned to each order. A 3-min intervening

as those used by Pezdek and Chen (1982) and delay task (circling all of the twos on a ran-

were selected from the set of pictures used by dom number sheet) was included between

Nelson et al. (1974) and, originally, by Nicker- presentation and test to ensure that the test

son (1965). These included 44 basic pictures, that followed measured long-term memoiy.

each drawn in both a simple, unembellished

line drawing form, and a cx)mplex, embel- Results

lished line chawing form, for a t o ^ of 88 pic-

tures. All drawings were black and white. The data were scared and analyzed in

The complex form of each picture was an ex- terms of the mean percent correct as well as

ac^ reproduction of the simple form, with the the signal detection measure of d'. However,

adciition of elaborative details to both the the m^jor results of this study concem di£Fer-

principal figure and the background. The cen- ences between the percent correct data for

tral information was thus the same in the sim- same test items (i.e., tiie hit rate) and changed

ple and complex form of each picture. Exam- test items (i.e., the csoirect rejection rate).

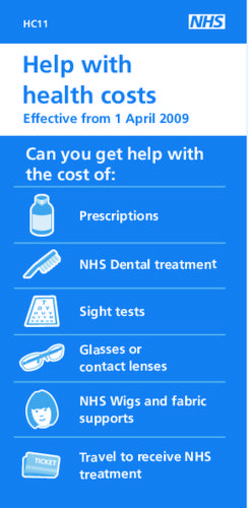

ples of stimulus pictures are shown in Figure These two conditions cannot be examined

1. The use of the same materials as in previ- separately with the d' measure. Throu^out

ous studies strengtiiens this study by allowing the study, results are considered significant at

a comparison of results ac^ross studies with- tile .05 level.

out possible confounding effects of different

materials. OveraU results.—A 4 (age) x 2 (presen-

tetion duration) x 2 (simple or complex pre-

Procedure.—Subjects participated indi- sentation form) X 2 (same or changed test

vidually. They were presented a sequence of form) mixed factorial analysis of variance was

slides including 44 presentation pictures, fol- performed on the percent correct data. All

lowed by a 3-min delay task, and then 44 test main effects were significant First, there

pictures. The presentation pictures included were signific^ant difierencies among the four

22 simple line drawings and 22 complex line £^e groups; young adults perfonned best

drawings. In the presentation phase, subjects (83.2%), followed by ^year-olds (75.4%), 7-

were instruc!ted to study each picture care- year-olds (67.6%). and older adults (67.0%),

fully, as it would be important in a later part F(3,152) = 29.94, MS^ = 309.10. Tukey pair-

of die experiment The pic;tures were pre- wise compariscms indic^ated that only the dif-

sented on slides by a Kodak Carousel slide ferences between young adulte and 7-year-

projector. During the presentation phase, olds and between young adults and older

slides were presented for 5 sec each or for 15 adtilts were significant Recognition acxnuacy

sec each. The inter-slide interval was 1 sec. was higher at the l5-sec rate (76.4%) than at

the 5-sec rate (70.2%). F(l,152) = 20.04, MSe

The test sequence consisted of 22 pic- = 309.10. Sulgects were more accurate recog-

tures from the presentation phase—11 simple nizing pic^res in the simple (79.5%) than

and 11 complex pic^tures. The remaining 22 cx)mplex (67.2%) presentation form, F(l,152)

test pictures were c^hanged versions of pre- = 100.71, MSe = 240.39, and they were more810 Child Development

SIMPLE COMPLEX

FIC. 1.—Examples of pictures in both simple and complex form

accurate recognizing pictures tested in the simple form (77.7%), i(152) = 1.81. In other

same form (hit rate = 77.9%) than in the words, subjects were significantly less accu-

changed forni (correct rejection rate = rate at detecting deletions from changed com-

68.7%), F(l,152) = 32.62, MS^ = 240.39. plex pictures than they were at detecting ad-

Interpretations of these main effects are ditions to changed simple pictures. This

qualified by three significant interactions. pattem of results was also the basis for the;

First, as can be seen in the bottom row of significant main effect of presentation form on

Table 1, the interaction of presentation form d'data,F(l,152) = 70.29, MS^ = 1.02, with d'

X test form was significant, F(l,152) = 32.31, greater for simple (d' = 2.12) than for com-

MSe = 161.49. Post hex: comparisons revealed plex pictures (d' = 1.17).

that the hit rate did not differ between pic- The interaction of presentation form x

tures presented in the simple form (81.3%) test form on percent correct also entered into

and complex form (74.7%). However, the cor- significant second-order interactions of age x

rect rejection rate was significantly less for presentation form x test form, F(3,152) =

pictures presented in the complex form 10.22, MSe = 161.49, and presentation dura-

(59.7%) than for pictures presented in the tion X presentation form X test fonn.Kathy Pezdek 811

TABLE 1

MEAN PERCENTAGE CORRECT IN EACH EXPERIMENTAL CONDITION

PRESENTATION CONDITION

Simple Complex

TEST CONDITION Same Changed Same Changed

7-year-olds:

5 sec 71.4 61.4 60.5 64.5

15 sec 82.7 74.5 69.1 56.8

Mean 77.0 67.9 64.8 60.7

9-year-olds:

5 sec 80.4 76.8 72.7 62.3

15 sec 90.9 80.9 80.9 58.2

Mean 85.7 78.9 76.8 60.2

Young adults:

5 sec 83.6 87.3 80.0 71.8

15 sec 87.7 91.8 88.6 74.5

Mean 85.7 89.5 84.3 73.2

Older adults:

5 sec 73.6 68.6 68.2 40.0

15 sec 79.5 80.0 77.3 49.1

Mean 76.6 74.3 72.7 44.5

Overall mean 81.3 77.7 74.7 59.7

F(l,152) = 4.99, MSe = 161.49. However, tiie presentation duration. The presentation form

overall age x presentation duration x pre- X test form interaction was significant at htiAi

sentation form X test form interacrtion did not presentation rates. Further, the percent cor-

approach significance (F< 1.00). rect difference between the 5-sec and 15-sec

conditions was significant in all cx)nditions ex-

The signific^ant interaction of age x pre- cept for changed complex pictures. The cor-

sentation form X test form is of particnilar in- rect rejection rats fbr complex pic:tures was

terest because this interaction allows an as- exactly the same (59.7%) at both presentation

sessment of qualitative differences in picture durations. Thus, increasing the presentation

recognition memory with age. These results duration by threefold did not increase sub-

are presented in Table 1. In order to assess jects' ability to detect the deleted details in

the nature of this interaction, separate 2 (pre- pictures that had been presented in the com-

sentation form) X 2 (test form) analyses of plex form.

variance were performed on the data for each

age group. The presentation form X test form Comparisons of young and older adults

interaction was significant for each age group only.—Several previous studies have re-

except 7-year-olds. Further, for each age ported tiiat differences in memory perfor-

group except 7-year-oIds the difference be- mance between young and older adults can in

tween the hit rates for simple and complex part be acxiounted for by age differences in

pictures was not significiant; however, the cor- pDDcessing time (Craik 6c Rabinowitz, 1985;

rect rejection rate was significantly less for Wingfield et al., 1985). The older adults were

changed c^omplex pictures than for changed included in the present study to examine

simple pic^res. On the other hand, for qualitative ciifferences in memory for details

7-year-olds, although pic^tures presented in in pictures between tiiese two age groups

their simple form were recognized signifi- and, specific^ally, to probe whetiier age differ-

cantly more accurately than pictures pre- ences in processing time underlie these mem-

sented in their complex form, F(l,38) = ory differences. Furtiier. the significant age X

12.08, the test form x presentation form in- presentation form x test fonn interaction re-

teraction was not significant. ported above statistically justifies examining

these two age groups separately.

In order to assess the nature of the signif-

icant interaction of presentation duration x A 2 (age) x 2 (presentation duration) x 2

presentation form x test form, separate 2 (presentation form) x 2 (test form) mixed fac-

(presentation form) x 2 (test form) analyses of torial analysis of variance was performed on

variance were periformed on the data at each the percent correct data. All main effects812 were significant in tiie same direction as in (see Friedman, 1979; Goodman, 1980; Nick- the overall axisAysis reported above. Of partic- erson & Adams, 197^). For example, consider ular interest is tiie finding thiA recogmtion ac- the chawing represented at the bottom left of curacy was higher for yoimg adults (83J2%) Figure 1. l l i e schema applied to tike |»cture tiian for older aduhs (67.0%), F(l,76) = 74.89, wcmld be the prepositional representation of a MSe = 278.17. There were also signlficfuit in- sentence such as, "The clown is crying." Ac- teractions of age X presentE^on form, F(l,76) c^txlin^y, infinmation that communict^s the = 5.27, MSe = 240.13, age x test form, central Schema of each picbire is mcare lticely F(l,76) = 7.71, MSe = 348.J®, and presenta- to be ehcoded and retained in memory than tion fctrm X test form, F(l,76) = 55.59, MS^ information tiiat does not communicate this = 150.51. Interpretations of each of these schema. It is important to note that tiie impli- firstKJrder interactions are qualified by the cation here is not that schemata are preserved significant secx}nd-orc^r interaction of £^e x in memcffy in a verbal form but, rotiier, that presentation form x test form, F(l,76) = 3.95, the pictorial ui&nrmatkat that is enc»>dbd sche- MSe = 103.40. As can be seen in the bottom matkraily is stoaikz' to tiie type of in&sm^ion half of Table 1, the hit rates for botii £^e that can be represented in a sentence tiiat sum- groups did not significantly differ between marizes the picture. simple and complex presentation pictures. However, for botii age groups, the correct re- Relevant to the present study, it is sug- jection rate was hi^ier for pictures pres^ted gested that the schema that is cilerived from in the simple form than in the complex fc»tn, the simple wid the cc»nplex form of eaeh pic- but the size of this dil&ren

Kathy Pezdek 813

tails are encoded and retained at longer inter- additions and deletions in the Mandler and

vals. Ritchey (1977) study involved adding or de-

leting a whole object in an array of objects.

In line with the schematic prcwessing no- Additions and deletions in the present study

tion outlined above, one interpretation of the involved adding or deleting more general

finding that pictures are better recognized at elaborative details in the simple and complex

longer study intervals is that this is due to version of each picture. Differences between

qualitative differences rather than quantita- the results of these two studies c^an be ac-

tive differences in encx)ding and storage of counted for by these methodological differ-

detail information. If we view picture mem- ences.

ory as a schema-driven process, then with

longer on-time subjects would be able to bet' In another relevant study. Brown and

ter abstract the central schema of each picture Campione (1972) had preschool children

and enrich the memory representation of the study pictures from children's bcwiks. Two

schema by incorporating into it more of the hours, 1 day, or 7 days later they were pre-

schema relevant infonnation in the picture. sented completely new distrac:tor pictures,

This would result in better schemata in mem- identical original picrtures, and changed

ory, not merely the storage of more details original pictures. The changed version of

from the picture. each original included the same character

(same clothes, same colors, etc.) as in the orig-

There are a few other studies in which inal picture but in a different pose. Subjects

recognition memory for additions to pictures responded "old" or "new" and tiien clas-

and deletions from pictures have been com- sified "old" items as either "identical" or

pared. However, each of those studies differs "changed."

in subtle but significant ways from the pres-

ent study. In some studies, for example, sub- Subjects weTe similarly accurate classify-

jects were instructed to respond "old" to orig- ing original and changed pictures as "old" at

inal pictures and to changed original pictures, each of the three retention intervals. How-

and "new" only to completely new, distractor ever, subjects were more accurate classify-

pictures. Results of these studies are not rele- ing changed pictures as "changed" than they

vant to the present interest in subject' ability were classifying identical pictures as "iden-

to distinguish original from changed pictures. tical." Although these findings differ from

The study by Park, Puglisi, and Sovacool those reported in the present study, they do

(1984) is one snch study. suggest that subjects are generally able to

"notice what is new" in changed old pictures.

In a more relevant study, Mandler and The differences in results between the prt;s-

Ritchey (1977) presented college subjects ent study and that by Rrown and Campione

with eight line drawings, each containing six (1972) can be attributed to differences in the

objects. The recognition test that followed in- type of changes included in "changed" test

cluded 64 "old" pictures composed of the pictures as well as to differences in the age of

eight target pictures plus seven transforma- the subjects.

tions of each, and 64 completely "new" dis-

tractor pictures. The two transformations Thus, several other studies have inves-

relevant to the present discussion were (a) tigated memory for additions to and deletions

additions and (b) deletions, in which a new from pictures. None of these studies concurs

object was added to or deleted from a target with the principal result of the present study,

picture. They reported no significsmt loss over that extra detail added to changed simple pic-

4 months in the recognition of additions or tures is detected more accurately than detail

deletions (in the organized picture condition), deleted from changed complex pictures. How-

and recognition accuracy did not differ be- ever, there are notable methodological differ-

tween these two types of pictures. ences between the present study and each of

these other studies.

These Tesults differ from results reported

in the present study. However, there are two There are two major developmental dif-

important differences between these two ferences in the pattem of results in the pres-

studies. First, in the Mandler and Ritchey ent study. First, for 7-year-olds the (difference

(1977) study, subjects were "correct" if they in the correct rejection rate for pictures pre-

classified either the target pic^res or the sented in the simple (67.9%) and complex

transformed pictures as "old." Thus, their re- form (60.7%) was not statistically significant,

sults do not allow us to assess how well sub- although this difference was significant for

jects distinguished target pictures from trans- each of the other three age groups. This

formed versions of these pic^res. Second, finding is consistent with the results of Pez-814 Child Development

dek and Chen (1982) that differences among relevant visual elaboration, as manipulated in

the four means defined by conditions of pre- the present study, is not retained well. These

sentation form and tost form were less for the results also hi^light the fact that various

younger children than for the young adults. measures of recognition memory tap very dif-

This result is also in line with the above inter- ferent aspects of what is retained in pictures.

pretation of the overall memory advantage for

simple over complex pic;tures. That is, if sim- References

ple pictures are better retained than complex Bevan, W., & Steger, J. A. (1971). Free recall and

pictures because of schematic processing of abstractness of stimuli. Science, 172, 597-599.

the pictures, and if young children are less Blaney, R. L., & Winograd, E. (1978). Develop-

likely than older children and adults to en- mental differences in children's recognition

code pictures schematically, then it would be memory for faces. Developmental Psychohgy,

expected that the correct rejection rate differ- 14, 441-442.

ence between simple and complex pictures

would be less for younger children as well. Bousfield, W. A., Esterson, J., & Whitmarsh, G. A.

(1957). The effects of concomitant colored and

The second developmental difference in uncolored pictorial representations on the

the obtained pattern of results involves a com- leaming of stimulus words. Jourruil of Applied

parison of the young and older adults. Al- Psychohgy, 41, 165-168.

though both young and older adults were Brown, A. L., & Campione, J. C. (1972). Recogni-

significantly more accurate rejecting changed tion memory for perceptually similar pictures

simple pictures than changed complex pic- in preschool children. Joumai of Experimental

tures, older adults were far less able than Psychology, 95, 55-62.

young adults to correctly reject changed Craik, F. I. M., & Rabinowitz, J. C. (1985). Tlie

complex pictures. In feet, older adults were efFect of presentation rate and encxxling task on

no better than chance at correctly rejecting age-related memory de&cits. Journal of Geron-

changed complex pictures. tology, 40, 309-315.

According to the interpretation previ- Dirks, J., & Neisser, U. (1977). Memory for objects

cmsly outlined, these results suggest that in real scenes: The development of recognition

when older adults encode complex pictures, and recall. Journal of Experimental Child Psy-

they retain far less of the elaborative details chology, 23, 315-328.

than do young adults. Thus, at the time of test, Evertson, C. M., & Wicker, F. W. (1974). Pictorial

their memory of complex pictures is similar to concreteness and mode of elaboration in chil-

the simple form of each picture, and they re- dren's leaming. Journal of Experimental Child

spond, "Same." Further, the fact that differ- Psychohgy, 17, 264-270.

ences between the young adults and the older Friedman, A. (1979). Framing pictures: The role of

adults did not result in significant interactions knowledge in automatized encoding and mem-

with presentation duration suggests that the ory for gist Journal of Experimental Psychol-

processing differences between young and ogy: General, 108, 316-355.

older adults are not simply a result of process- Coodman, C. S. (1980). Picture memoiy; How the

ing rate differences. action schema affects retention. Cognitive Psy-

chohgy, 12, 473-495.

This study leads to the conclusion that Haith, M. M., Morrison, F. J., & Sheingold, K.

although adults and children are extremely (1970). Tachistoscopic recognition of geometric

accurate at discriminating old pictures from forms by children and adults. Psychonomic Sci-

completely new pictures (Hof&nan & Dick, ence, 19, 345-347.

1976; Nickerson, 1965; Shepard, 1967; Stand- Hofftnan, C. D., & Dick, S. A. (1976). A develop-

ing et al., 1970), they are far less accurate dis- mental investigation of recognition memory.

criminating same from changed versions of Child Devehpment, 47, 794-799.

old pictures, especially when the changes in- Laughery, K. R., Alexander, J. V., & Lane, A. B.

volve detecting what extra detail has been de- (1971). Recognition of human faces: Effects of

leted from changed complex pictures. These target exposure time, target position, pose posi-

results are important because they suggest tion and type of photograph. Journal of Ap-

that when we "remember" a picture or a real plied Psychohgy, 55, 477-483.

world scene, we do not necessarily retain all, Mackworth, N. H., & Bmner, J. S. (1970). How

or even most, of the elaborative detail pre- adults and children search and recognize pic-

sented. This is consistent with the notion that tures. Human Devehpment, 13, 149-177.

pictures, like prose materials, are processed Mandler, J. M., & Ritchey, C. H. (1977). Long-tenn

schematically. As such, scheme-relevant memory for pictures. Journal of Experimental

information in pic:tures is likely to be retained Psychohgy: Human Leaming and Memory. 3,

well in memory, whereas less scheme- 386-396.Kathy Pezdek 815

Mandler, J. M., Seegmiller, D., & Day, J. (1977). On Potter, M. C. (1976). Short-term conceptual memory

the ccxling of spatial information. Memory and for pictures. Journal of Experimental Psychol-

Cognition, 5,10-16. ogy: Human Leaming and Memory, 2, 509-

Naus, M. U Omstein, P. A., & Aivano, S. (1977). 522.

Developmental changes in memory: The ef' Potter, M. C , & Levy, E. L (1969). Recognition

fecte of prcK:es8lng time and rehearsal instruc' memory for a rs^id sequence of pic:tures> Jour-

tions. Journal of Experimental Child Psychol- nal of Experimental Psychohgy, 81,10-15.

ogy, 2a, 23^7-251. Reese, H. W. (1970). Inuigery and contextual mean-

Nelson, T. O., Metzler, J., & Reed, D. A. (1974). ing. In H. W. Reese (Chair), Imagery in chil-

Role of details in tiie long-tenn rec:ogmticm of dren's leaming: A symposium. Psychohgical

pictures and verbal descripticms.J'cmma/ of Ex- .Bulletin, 73,40^-414.

perimental Psychohgy, 102,184-186. Shepaid, R. N. (1967). Recognition memory for

Nickerson, R. S. (1965). Short-term memoiy for words, sentences, and pictures. Joumo/ of Ver-

complex visual configurations: A {demonstra- bal Leaming and Verhal Behavior, 6,156-163.

tion of capacity. Canadian Journal of Psychol- Standing, L., Conezio, J., & Haber, R. N. (1970).

ogy, 19,155-160. Perception and memory for pictures: Single-

Nickerson, R. S.,ficAdams, M. J. (1979). Long-tenn trial leaming of 2500 visual stimuli. Psycho-

memory for a conunon object Cognitive Psy- nomic Science, 19, 73-74.

chohgy, 11,287-307. Tversky, B., & Shennan, T. (1975). Picture memoiy

Park, D. C., Puglisi, J. T , & Sovaoool, M. (1984). improves with longer on time and oS time.

Picture memory in older adults: Effects of cx>n- Journal of Experimental Psychohgy: Human

textual detail at encoding and retrieval. Journal Leaming and Memory, 104,114-118.

cf Gerontohgy, 39,213-215. Vurpillot, E. (1968). The development of scanning

Pezdek, K., & Chen, H.-C. (1982). Developmental strategies and their relation to visual differ-

di£ferences in the role of detail in picture entiation. Journal of Experimental Child Psy-

recognition memory. Journal of Experimental chohgy, 6,632-650.

Child Psychohgy, 33» 207-215. Wii^field, A., Poon, L. W., Lombardi, L., &

Pezdek, K., 6c Miceli, L. (1982). Ufe-span diSer- Lowe, D. (1985). Speed of processing in normal

ences in memoiy integraticm as a &mction of ^ n g : Effects of speech rate, linguistic stnio

prcKiessing time. Devehpmental Psychohgy, ture, and processing tixae. Journal of Gerontol-

18,485-490. ogy, 40,579-585.You can also read