Health information and teenagers in residential care A qualitative study to identify young people's views

←

→

Page content transcription

If your browser does not render page correctly, please read the page content below

Health information and teenagers in

residential care A qualitative study to identify

young people’s views

Study setting and sample

Annabelle Bundle presents the results of a quali-

The study was carried out between

tative study, undertaken in a mixed residential August and November 1998 in a mixed

children’s home, which aimed to identify what looked residential children’s home for young

after young people see as important in terms of people aged 12–16+ years, with a school

health information. The young people wanted inform- on site. Situated in the north of England,

ation particularly on mental health issues, keeping fit, the home has 32 beds, eight being in a

secure setting. It is a national facility,

substance use and sexual health. Many were reluct- suitable for those with previous place-

ant to request appointments for personal matters ment breakdown and school failure.

and did not feel they were encouraged to ask about Forty-six young people were resident at

personal health concerns during medical examinations. some time during the study period. Ten

were admitted on emergency placements

and were excluded from the study. Of the

remaining 36, the age range was 13–16

Annabelle Bundle is Introduction years, with more males at the younger

Associate Specialist A school-based survey in 1997 found that and more females at the older end of the

Community most young people preferred to share age range. All were white. Eight had

Paediatrician,

Central Cheshire

health worries with their mother (Balding, experienced multiple episodes in care.

Primary Care Trust, 1998). Because breakdown of family The mean number of placements per child

Winsford, Cheshire relationships is a contributory factor to was six. The mean length of time being

residential placement for many teenagers, looked after was 30.9 months. Thirty-

Key words:

those in residential care may not be able three residents attended the on-site school

teenagers, looked after

children, residential to share health concerns with a parent. and three attended other schools. Seven-

care, public care, Education and behaviour problems are teen had a statement of special educa-

health information common in looked after children and tional needs (60 per cent for emotional/

there is a high rate of psychiatric illness behavioural disorders and 20 per cent for

in adolescents in care (Halfon et al, 1995; moderate learning difficulties).

McCann et al, 1996; Mather et al, 1997;

Broad, 1999). Many looked after children Methods

have poor school attendance and school A list of questions to be covered in the

refusal (Berridge and Brodie, 1998; interviews was compiled by the author and

Sinclair and Gibbs, 1998). Consequently, discussed with her supervisor. As a pilot,

they may miss out on health education. semi-structured interviews were carried

Concerns about headaches, acne, diet, out with a 15-year-old boy and a 14-year-

sexual health, drugs and mental health old girl attending mainstream secondary

have been identified in studies of looked schools and not in public care. Transcripts

after young people, with written informa- of the interviews were reviewed by the

tion wanted by those in residential care author and her supervisor to identify bias

(Coutts and Polnay, 1997; Mason, 1997). and any additional questions to be asked in

However, published reports often lack the study interviews.

details of methodology or involve very Following the two pilot interviews and

small numbers of young people (Mapp, an additional discussion with two other

1996; McGuire and Corlyon, 1997; young people (not in public care) about

Landon, 1998). This research sought to the variety of issues that could be in-

clarify what a specific group of teenagers cluded under the heading ‘health’, it was

in residential care see as important in the felt that a ‘Health Information Topics’ list

area of health information. would be helpful when introducing the

research to the residents at the children’s

ADOPTION & FOSTERING VOLUME 26 NUMBER 4 2002 19home. The list contained 25 suggestions past and for most there was more than

and each resident was asked to choose up one: nine had received information from

to ten topics they wanted information school, seven from parents, six from care

about. They were not asked to put these in staff and five from a doctor. Five also

order of priority, nor were they asked to looked for information in magazines.

indicate if they had previously received Information from doctors was not always

information on these topics. They could well understood and the comprehensi-

add further topics if they wished. The bility of written information depended on

Health Information Topics list was com- how it was phrased. When asked where

pleted prior to semi-structured interviews. they would go to find out about a particu-

Some chose to complete it on their own, lar health issue, ten said a doctor, five a

others preferred to do it after discussion clinic, five a member of the care staff,

with the author. three a teacher and three a library. Only

Consent to interview was obtained three said they would ask a parent, but

from the young person and, where appro- one of these said her mother was the

priate, a person with parental responsi- person she would talk to if it was a per-

bility. Interviews were conducted privately, sonal problem. Accessibility of informa-

recorded on audio-tape with the young tion was a concern. Telephoning a parent

person’s consent and transcribed as soon was a possibility, but the majority needed

as possible afterwards. Assurance was permission to go off site. For personal

given that data would be anonymised. issues, having to ask permission to make

Frequency data were produced from an appointment and leave the site was a

the Health Information Topics list. In- problem.

formation from interviews was analysed Three felt that some health informa-

by identifying themes and categories, tion already received had not been re-

collating responses to each question and quired. For one, repetition of information

coding the information (Burnard, 1998). at different schools was unwelcome;

Audio-tapes were also reviewed by the another felt he already knew most of the

author. Quotes from the young people sex education he had received. Seven felt

have been included to illustrate themes. that some information should have been

given at a different age, or updated as

The study participants they became older. For girls this applied

Eight males and three females aged 13– to sex education, contraception, sexually

14 years, and four males and seven transmitted infections and pregnancy.

females aged 15–16 years completed the This was also mentioned by one boy. A

Health Information Topics list. This 15-year-old girl felt strongly about sex-

reflected the age and sex distribution of ually transmitted infections, that:

the residents.

In total, 18 young people were inter- children should be told as soon as they

viewed. Eight males and one female were are old enough to understand about it, at

aged 13–14 years, and three males and six their level of maturity. They should be

females were aged 15–16. Four who told straight away.

completed the Health Information Topic

list declined interview. Drugs were mentioned by a 16-year-old

girl as an issue which should be covered at

Results a younger age than 11 or 12, and two boys

wanted information about smoking at age

Health information 10–12. Twelve said previous information

Preferred topics for health information in had influenced some aspect of their

the two age bands, identified by the behaviour. Of these, seven had tried to stop

Health Information Topics list, are given smoking or decided not to start; five had

in Table 1. become aware of the importance of safe

The semi-structured interviews showed sex; one had learned not to be lazy.

that the young people had obtained in- However, despite previous information,

formation from a variety of sources in the two said they would continue to smoke and

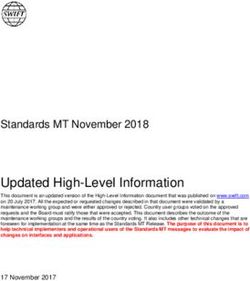

20 ADOPTION & FOSTERING VOLUME 26 NUMBER 4 2002Table 1

Health Information Topics list: choice of health information topics in order of frequency*

Topic % who selected No. in age group 13–14 No. in age group 15–16

each topic who selected each topic who selected each topic

Stress 64 6 8

Keeping fit 64 7 7

Drugs 59 8 5

Alcohol 59 8 5

Smoking 59 8 5

Sex education 54 9 3

Family planning 45 4 6

Healthy eating 45 6 4

Sexually transmitted diseases 41 4 5

Acne 41 4 5

Staying healthy 41 5 4

Depression 35 5 3

Asthma 32 2 5

Eating disorders 27 1 5

Child development 27 4 2

Sports injuries 27 4 2

Bullying 23 2 3

Personal safety 23 2 3

Personal hygiene 23 2 3

Eczema 23 1 4

Puberty 18 3 1

Sun protection 14 0 3

Epilepsy 9 1 1

Diabetes 5 0 1

Immunisations 5 0 1

one said he would continue to use drugs. Two stressed the importance of health

Two (14-year-old males) said they would information being available to all

only learn by their own experiences. residents. Five only wanted to receive

Written information about health health information verbally. Some felt

issues was wanted by 13, with the option information on computer might be useful,

of discussing it before or afterwards. The and a 14-year-old male said computer

opportunity to take it away to read them- games on bullying and hygiene would be

selves was important: more interesting to teenagers. However,

there was uncertainty about access to a

I like to have something given me to read, computer in the home.

‘cause I can sit in my room and read it. The young people were asked whether

*Additional topics, each identified by a different person, were: first aid, respect for old people,

living accommodation after leaving care, cystitis, anaemia and where teenagers can get help with

health issues.

ADOPTION & FOSTERING VOLUME 26 NUMBER 4 2002 21health information would be more accept- bullying as well, but kids could not know

able to them if teenagers helped write it. what’s happening.

Their views varied. Eight felt this would

be a good idea, although seven of these She felt this was an issue the young people

felt such information should be checked in the home knew about, but that should be

for accuracy by a professional. One said: available to children in all schools.

I would like it to be in my own words. You Their own health

get things at the doctors all in medical Twelve of those interviewed had some

jargon and you just don’t understand it. concern about their present health.

Several talked about missed immunisa-

In contrast, eight felt it was better for tions, particularly BCG. Other concerns

information to be written by older people. included sexually transmitted infections,

One 15-year-old girl said: asthma, anorexia nervosa, acne, puberty

and general fitness. Although many were

I’d probably tend to read it more if I knew not interested in their past health, one

it was somebody a bit older who’d done it, talked about his ‘lifeline’. This contained

because I still go by the, you know, the information he had asked for about such

older the wiser sort of motto. things as which day of the week he was

born and when he had been in hospital.

One preferred a mixture of writers, dep- When asked about previous medical

ending on the seriousness of the issue, consultations, either with the general

and two felt they could put information practitioner (GP) or when attending for

together themselves, with the help of their statutory annual medical examina-

someone who knew about the subject. tion, only six felt they had been useful,

Most of the young people therefore wanted and only three of these felt they had been

information they could understand and given encouragement or opportunity to

which came from a respected source. ask about their own health concerns. For

When asked if it would be useful to most, arranging an appointment to see the

have telephone helpline numbers, eight GP would be done by a member of the

felt they either would not use helplines or care staff. One 16-year-old said she could

their previous experience was unfavour- make her own appointment, but would

able. They represented both sexes and all need permission to be off site. Six did not

ages. One preferred to talk to someone feel comfortable seeing the GP and

face to face. However, ten said helpline several said that when they had to see a

numbers would be useful. The importance doctor they would prefer seeing the same

of Freephone numbers was stressed by one each time. For one, the staff member

three, and another said numbers should who accompanied her to the appointment

be available to all residents, not just kept was important, as was having a choice of

in a central place. Specific rather than whether this person would remain outside

general helplines were mentioned by the consulting room:

several:

It would depend on if the staff were sitting

It needs to be someone who knows exactly in, because if it was someone I didn’t know

what you’re talking about, for the answers well and I was told, right you can come

you need. and talk to the doctor about your eating,

but . . . was coming in, I wouldn’t talk in

All those interviewed were given the front of her. But if I was told a member of

opportunity to raise any additional health staff was sitting outside the door or if I

information needs. One girl talked about was told I’d have a member of staff I felt

information on abuse: comfortable with, it wouldn’t be a problem.

I think we should have leaflets on abuse Confidentiality was not asked as a

and things like that, or people going into specific question, but was raised by four

schools and talking. It comes under people as being important, and implied by

22 ADOPTION & FOSTERING VOLUME 26 NUMBER 4 2002a further four who said they would not in residential children’s homes. Acne and

tell staff the reason for wanting an puberty were identified in both the Health

appointment if the matter was personal. Information Topics list and the interviews

as being of concern to several male resi-

Discussion dents. Looked after children often have

The Department of Health consultation poor school attendance, so they are likely

document, Promoting Health for Looked to miss personal, social and health

After Children (1999), includes health education lessons when these issues

promotion as one of the key areas of would have been discussed.

healthcare planning for looked after Sex education was wanted by more of

children. A National Children’s Bureau the younger age group, while family

report on health promotion and looked planning and sexually transmitted infec-

after children (McGuire and Corlyon, tions were of interest to more of the older

1997) stresses the importance of viewing group. It is likely that this reflects their

health promotion as more than simply own experiences. Giving such informa-

giving information to individuals, rather tion at an early age was stressed by one

it should focus on ‘the creation or young woman, though she recognised that

improvement of structures that can pro- this would need to be tailored to the

vide help and support to young people maturity of the individuals.

and those who care for them’ (p 3). Although Broad (1999) found specific

This study could be criticised for health information about smoking and

concentrating on health information, but drinking was wanted by care leavers, in

the latter is an essential step in planning this study information about substance

health promotion intervention (Warwick use of all kinds was of more interest to

et al, 1998). Discussion of the Health the younger age group. Interventions

Information Topics list with some of the aimed at reducing the likelihood of

young people, prior to them completing younger residents starting to misuse sub-

it, could have introduced bias into their stances should be considered, while

responses, but they were encouraged to taking account of circumstances that

give their own views. Knowledge of their affect drug use (Health Education

views assists in planning appropriate Authority, 1997).

provision, and the experiences of service There was a variety of views about the

users should inform the process of pro- format of future information. Written

viding services to children in need information was preferred by 72 per cent

(Mather et al, 1997; Warwick et al, 1998; of those interviewed, although some also

Department of Health, 2000). wanted an opportunity to discuss it. When

Mental health issues are of concern to discussing the Health Information Topics

young people in residential care (Mason, list, two young people stressed the

1997; Mather et al, 1997). This study importance of information being available

found that 64 per cent wanted information to every resident, not simply displayed in

about stress and 36 per cent information a central place. Any written information

about depression. Eating disorders were needs to be accessible, accurate and

also of concern. The study was not appropriate in content, style and reading

designed to diagnose mental health pro- age. Involving young people in compiling

blems, but the extent of concerns raised information could be considered, as this

by the young people themselves high- may improve both their understanding

lights their need for access to emotional and motivation to use it. The use of

support and, where necessary, specialist information technology was mentioned by

mental health services, as recommended some and should be explored, though

in the draft National Healthy Care access to a computer and privacy when

Standard (National Children’s Bureau, using it may be difficult in a residential

2002). home, as they might with telephone

Information about keeping fit was helplines.

wanted by 64 per cent and opportunities Although many of the young people

for physical activity should be available expressed little interest in their previous

ADOPTION & FOSTERING VOLUME 26 NUMBER 4 2002 23health, this information may become 1999). In the area in which the study

more important to them as they get older. home is situated, mainstream secondary

A health record which is retained by the schools have regular school nurse ‘drop-

young person has been advocated (Butler in’ clinics, in addition to health inter-

and Payne, 1997; Irving et al, 1997). views offered to all Year 7 pupils. The use

Such a record could contain the of a school nurse to provide a similar

information that one resident had asked service in residential children’s homes

for in his ‘lifeline’. would give these young people easier

Social workers and carers may discour- access to a knowledgeable health profess-

age teenagers from attending the statutory ional, with an opportunity to talk confi-

annual medical examination (Irving et al, dentially about their own health concerns

1997). Physical examination may not be and to discuss any written health informa-

the best way to assess the health of teen- tion they receive. The nurse could facili-

agers. Mental and emotional well-being, tate referrals where required and also

health promotion and gaps in the uptake address such issues as incomplete

of child health promotion should also be immunisations.

addressed (Polnay et al, 1996; Butler and The young people in this study may

Payne, 1997; Irving et al, 1997; Mather et have needs that are different from those in

al, 1997). However, where physical exam- foster care or smaller residential units.

ination is indicated, providing a choice of Those in foster placements may have less

doctor and continuity when further restriction on their movements, facilita-

appointments are required, is important. ting confidential access to telephones and

This would help address the concern healthcare services. The lack of a trusted

raised by some young people of wishing adult has been identified by young people

to see the same doctor each time. Those in public care (Mather et al, 1997). There

interviewed had found a lack of encour- may be greater opportunities to build a

agement to raise their own health con- trusting relationship with a long-term

cerns at medical examinations. This must foster carer, with whom they can share

be taken seriously as 67 per cent had health concerns. However, foster carers

concerns about their current health. may be unsure of their responsibilities in

Therefore, any consultation with a health respect of health promotion and young

professional should be combined with an people in their care (McGuire and

opportunity for teenagers to talk about Corlyon, 1997). Smaller residential units

their own concerns. may also facilitate the development of

McGuire and Corlyon (1997) identi- such a relationship of trust, but a high

fied the need for: ‘an adult from outside turnover of residents may make this

the young person’s immediate environ- difficult (Polnay et al, 1996; Sinclair and

ment from whom they can obtain inform- Gibbs, 1998). Minimising the number of

ation on such subjects as sex and drugs placement changes is crucial for all

and with whom they can share personal children in public care.

details if they so wish’ (p 74).

In this study, more than a quarter of Implications for practice

those interviewed saw clinics as a source Teenagers in residential care are a part-

of information. Promoting Health for icularly disadvantaged group, frequently

Looked After Children (Department of having unmet health needs and poor

Health, 1999) emphasises the importance educational attainments. It is important

of looked after young people having ‘the that they are not disadvantaged further by

opportunity to enjoy a standard of care as lack of provision of services available to

good as all children of the same age teenagers in mainstream secondary

living in the same area’ (p 3). School schools. Although provision of health

nurses have a key role in meeting the information is only part of the wider

health needs of school-age children and scope of health promotion, providing

some issues may be addressed more information in a format acceptable to

appropriately by nurses (British Paediatric them, covering issues which they have

Association, 1995; Department of Health, identified as areas of concern, is import-

24 ADOPTION & FOSTERING VOLUME 26 NUMBER 4 2002ant. If this is combined with opportunities planning, assessment and monitoring,

to talk to a health professional, such as Consultation document, London: DH, 1999

occurs at school nurse drop-in clinics, it Department of Health, Department for

could help reinforce the message and Education and Employment, Home Office,

increase its effectiveness. Whether this Framework for the Assessment of Children in

would lead to improvement in the health Need and their Families, London: The

of the residents will need to be moni- Stationery Office, 2000

tored. All health professionals who have Halfon N, Mendonca A and Berkowitz P,

contact with young people should give ‘Health status of children in foster care’, Arch

them encouragement and opportunity to Pediatr Adolesc Med 149, pp 386–92, 1995

talk about their own health concerns, and Health Education Authority, ‘Health promotion

maximise the health promotion oppor- in young people for the prevention of substance

tunities such contacts provide. misuse’, Health Promotion Effectiveness

Reviews, Summary Bulletin 5, 1997

Acknowledgements

Irving M, Evans S and Watson L, ‘British

This research was undertaken for the Agencies for Adoption and Fostering in

MMedSc in Child Health at the Univer- Scotland: Scottish medical advisers’ survey’,

sity of Leeds. I am grateful to Dr S Wyatt Public Health 111, pp 225–29, 1997

and Dr M Rudolf for their advice and

Landon J, ‘Children in care: responding to their

support; also to the Community Liaison

health education needs’, Healthlines, March,

Officer, young people and staff at the pp 12–14, 1998

home.

McCann J, James A, Wilson S and Dunn G,

‘Prevalence of psychiatric disorders in young

References

people in the care system’, British Medical

Balding J, Young People in 1997: The health-

Journal 313, pp 1529–30, 1996

related behaviour questionnaire results for

37,538 pupils between the ages of 9 and 16, McGuire C and Corlyon J, Health Promotion

School Health Education Unit, St Luke’s, and Looked After Children in Brent & Harrow,

Heavitree Road, Exeter, Devon, 1998 London: National Children’s Bureau, 1997

Berridge D and Brodie I, ‘Children’s homes Mapp S, ‘Having a say’, Community Care 21–27

revisited’, in Davies C, Archer L, Hicks L and Nov, p 27, 1996

Little M (Department of Health series eds),

Mason J, ‘Care and control’, Nursing Times

Caring for Children Away from Home: Messages

93:22, pp 25–6, 1997

from research, Chichester: John Wiley & Sons,

1998 Mather M, Humphrey J and Robson J, ‘The

statutory medical and health needs of looked

British Paediatric Association, The Health Needs

after children: time for a radical review’,

of School-age Children, London: British

Adoption & Fostering 21:2, pp 36–39, 1997

Paediatric Association, 1995

Polnay L, Glaser A and Rao V, ‘Better health for

Broad B, ‘Improving the health of children and

children in resident care’, Archives of Disease in

young people leaving care’, Adoption &

Childhood 75, pp 263–65, 1996

Fostering 23:1, pp 40–48, 1999

National Children’s Bureau, National Healthy

Burnard P, ‘Qualitative data analysis using a

Care Standard (draft document 2002,

word processor to categorise qualitative data in

www.wiredforhealth.gov.uk/nhcs)

social science research’, Social Sciences in

Health 4:1, pp 55–61, 1998 Sinclair I and Gibbs I, ‘Children’s homes: a

study in diversity’, in Berridge D and Brodie I,

Butler I and Payne H, ‘The health of children

as above

looked after by the local authority’, Adoption &

Fostering 21:2, pp 28–35, 1997 Warwick I, Fines C, Toft M, Whitty G and

Aggleton P (ed Edmonds J) Health Promotion

Coutts J and Polnay L, ‘Children in residential

with Young People: An introductory guide to

care: a healthier future’, Primary Health Care

evaluation, London: Health Education

7:3, pp 13–16, 1997

Authority, 1998

Department of Health, Promoting Health for

Looked After Children: A guide to healthcare © Annabelle Bundle, 2002

ADOPTION & FOSTERING VOLUME 26 NUMBER 4 2002 25You can also read