From conflict to collaboration: the contribution of co- management in mitigating conflicts in Mole National Park, Ghana

←

→

Page content transcription

If your browser does not render page correctly, please read the page content below

From conflict to collaboration: the contribution of co-

management in mitigating conflicts in Mole National

Park, Ghana

O P H E L I A S O L I K U and U L R I C H S C H R A M L

Abstract Few studies exist about the extent to which co-man- and values, thereby resulting in violence, loss of livelihoods,

agement in protected areas contributes to conflict prevention displacement of communities and resource degradation

or mitigation and at what level of the conflicts such collabora- (Castro & Nielsen, ; Treves & Karanth, ).

tive efforts are possible. Following varying degrees of conflict, Conflicts occur when two or more parties hold strong

Mole National Park, Ghana, embarked on a collaborative views over conservation objectives and one party tries to as-

community-based wildlife management programme in . sert its interests at the expense of the other (Young et al.,

Using Glasl’s conflict escalation model, we analysed the contri- ; Redpath et al., , ). Such conflicts can occur

bution of co-management to mitigating and preventing con- when parties representing conservation interests try to im-

flicts from escalating. We conducted a total of interviews pose restrictions on the use of forests and wildlife resources

with local traditional leaders, Park officials and local govern- or displace and relocate local people from their abodes as a

ment officials, and focus group discussions with farmers, result of the establishment of protected areas (Vodouhe

hunters, women and representatives of co-management et al., ; Velded et al., ). Conflicts can also occur

boards, selected from of the communities surrounding when protected wildlife has impacts on people and their ac-

the Park. Our findings indicate that co-management can help tivities, such as predating farm crops and livestock, resulting

mitigate or prevent conflicts from escalating when conflicting in retaliatory killings (Dickman, ; Mateo-Tomás et al.,

parties engage with each other in a transparent manner using ).

deliberative processes such as negotiation, mediation and the Although in these circumstances conflicts may be inevit-

use of economic incentives. It is, however, difficult to resolve able, the challenge is to prevent such conflicts escalating, or

conflicts through co-management when dialogue between to minimize their impacts (Redpath et al., ). Since the

conflicting parties breaks down, as parties take entrenched s, in response to such conflicts, there has been a move

positions and are unwilling to compromise on their core values from conventional centralized approaches of protected area

and interests. We conclude that although co-management management to participatory and integrative approaches,

contributes to successful conflict management, factors such including co-management and community-based natural

as understanding the context of the conflicts, including the resources management. Some scholars contend that co-

underlying sources and manifestations of the conflict, incor- management between local people, other stakeholders and

porating local knowledge, and ensuring open dialogue, trust state agencies offers substantial promise for conflict man-

and transparency between conflicting parties are key to agement (Butler, ; Ho et al., ). These approaches

attaining sustainable conflict management in protected areas. are expected to foster community empowerment (Plummer

et al., ), ensure inclusive decision making and legitimacy

Keywords Co-management, conflict management strate-

(Berkes, ; Sandström et al., ), and lead to benefit

gies, Ghana, Mole National Park, protected area

sharing and, ultimately, livelihood enhancement (Chen

et al., ; Ming’ate et al., ). Others have argued that

co-management can strengthen the state’s control over

Introduction

resources, leading to further marginalization of local

communities (Castro & Nielsen, ). Castro & Nielsen

P rotected areas are tools for conserving biodiversity but

their objectives are often in conflict with other interests () advocated that a clear assessment of the benefits

and limitations of co-management as a mechanism for

promoting conflict resolution, peacebuilding and sustain-

OPHELIA SOLIKU* (Corresponding author) Chair of Forest and Environmental able development is necessary.

Policy, University of Freiburg, Tennenbacher Str. 4, 79106 Freiburg, Germany

E-mail ophelia.soliku@ifp.uni-freiburg.de Studies of co-management have focused on the role and

ULRICH SCHRAML Department of Forest and Society, Forest Research Institute prospects of co-management in conflict resolution and

Baden-Wuerttemberg, Freiburg, Germany management (e.g. Zachrisson & Lindahl, ; De Pourcq

et al., ) but little is known about the actual contribution

*Also at: Department of Community Development, University for Development

Studies, Wa, Ghana and influence of co-management in preventing or mitigat-

Received September . Revision requested November . ing conflicts in protected areas. A key question is, to what

Accepted February . First published online September . extent does the involvement or otherwise of key

This is an Open Access article, distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution licence (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted re-use,

Downloadeddistribution,

from https://www.cambridge.org/core. IP address:

and reproduction in any medium, provided 82.12.2.223, on 06isSep

the original work 2020 cited.

properly at 19:38:20, subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms

. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0030605318000285

Oryx, 2020, 54(4), 483–493 © 2018 Fauna & Flora International doi:10.1017/S0030605318000285484 O. Soliku and U. Schraml

stakeholders in protected area management affect the pre- collaborative and private approaches that involve only the

vention and mitigation of conflicts? Here we focus on a conflicting parties or a mediator, to more coercive actions

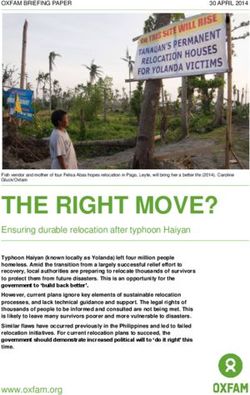

case study in Ghana’s largest national park, Mole National that can involve violence (Fig. ). The most appropriate

Park, which is currently implementing co-management and legitimate means of addressing a conflict depends on

programmes to promote stakeholder participation in Park the situation and intensity or stage of the conflict (Glasl,

management. ; Engel & Korf, ). Moore’s () continuum of

Specifically, we address three questions: () How do actors conflict management approaches reflects Glasl’s escalation

in the Park perceive conflicts between Park authorities and model. We therefore applied Glasl’s impairment approach

surrounding communities? () How have co-management and conflict escalation model to define the conflict situation

initiatives helped to manage or prevent conflicts from escal- and stages of escalation, and Moore’s () conflict man-

ating? () How can co-management initiatives be improved agement strategies to analyse the contribution of co-

to enhance conflict management? Our study is based on the management in prevention and mitigation of conflicts, to

propositions that actors perceive conflicts when they are determine at which stages of conflict co-management is pos-

excluded from decision making regarding protected area sible and can yield positive outcomes (Fig. ).

management, and involvement (or exclusion) of key stake-

holders, including surrounding communities, in the form Study area

of co-management has a significant impact on the preven-

tion and mitigation of conflicts. Forest and wildlife resources are the main source of liveli-

hood for many rural people in Ghana. However, in the pro-

cess of utilizing these resources they have severely depleted

Conflict and conflict management: a theoretical them. In , to ameliorate this situation and to address

framework the increasing conflicts between protected area manage-

ment and surrounding communities, the Wildlife Division

Conflicts have broadly been defined as differences in inter- of the Forestry Commission commissioned a policy for

ests, goals or perceptions (Coser, ; Pruitt et al., ). Collaborative Community Based Wildlife Management.

This definition has, however, been criticized for not distin- The aim was to ‘enable the devolution of management au-

guishing between conflicts and causal factors (Yasmi et al., thority to defined user communities and encourage the par-

; De Pourcq et al., ) as differences are inevitable in ticipation of other stakeholders to ensure the conservation

almost all social encounters. Glasl’s () impairment ap- and a perpetual flow of optimum benefits to all segments

proach to conflict, however, provides clear criteria for dis- of society’ (Forestry Commission of Ghana, , p. ).

tinguishing between conflict and non-conflict situations. This policy culminated in two primary institutional me-

Glasl () describes conflict as a situation in which an chanisms for implementing collaborative forest and wildlife

actor feels impairment from the behaviour of another management both within and outside protected areas:

actor because of differences in perceptions, emotions and Protected Areas Management Advisory Units and

interests. This approach notes three key elements that de- Community Resource Management Areas. The latter pro-

scribe conflicts. Firstly, conflicts are attributed to two actors, vide a mechanism by which authority and responsibilities

the opponent and the proponent (Yasmi et al., ; Marfo for wildlife are transferred from the Wildlife Division of

& Schanz, ). Secondly, the defining element of conflict, the Forestry Commission to rural communities within the

which is the key criterion to distinguish conflict situations same socio-ecological landscape, who collaborate with

from non-conflict situations, is the experience of an actor’s other non-local stakeholders to achieve linked conservation

behaviour as impairment. Thirdly, the approach distin- and development goals and derive economic incentives

guishes between the sources or causes of conflicts and the through the promotion of community-based tourism, art

actual conflict situations. These three distinctions provide and craft production, and promotion of alternative liveli-

the framework for our study. Glasl () further provides hood options such as beekeeping. Protected Areas

a nine-stage conflict escalation model (Table ) that de- Management Advisory Units serve as focal points in

scribes the stages of a conflict, the threshold to the next which protected area administrators and stakeholders, in-

stage, and strategies for de-escalation. cluding local government, government agencies, NGOs

Approaches to conflict management generally refer to a and surrounding communities, come together to exchange

range of options for preventing the escalation of conflict ideas on natural resource management and to resolve any

(Yasmi, ; Redpath et al., ) but most do not provide conflicts. All surrounding communities are part of a

a clear delineation of the stages of conflict management Protected Areas Management Advisory Unit and therefore

based on the level of escalation and resultant outcomes. benefit from its activities. On the other hand, only commu-

Moore (), however, outlined a continuum of conflict nities who have formed Community Resource Management

management approaches ranging from informal, Areas enjoy benefits accruing from them.

Oryx, 2020, 54(4), 483–493 © 2018 Fauna & Flora International doi:10.1017/S0030605318000285

Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. IP address: 82.12.2.223, on 06 Sep 2020 at 19:38:20, subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms

. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0030605318000285. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0030605318000285

Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. IP address: 82.12.2.223, on 06 Sep 2020 at 19:38:20, subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms

Oryx, 2020, 54(4), 483–493 © 2018 Fauna & Flora International doi:10.1017/S0030605318000285

TABLE 1 A nine-stage model of conflict escalation (Glasl, ).

Stage Conflict characteristics Threshold to next stage Strategies for de-escalation*

1. Hardening Standpoints harden but parties are not yet entrenched; there is an Loss of faith in the possibility of fair discus- Self-help

awareness of mutual dependence & actors believe the tension is sions; tactical & manipulative tricks used in

resolvable argumentation

2. Debates & Polarization of thought & emotions; parties look for more forceful When dialogue is pointless & useless; when Self-help

polemics ways of pushing their standpoints, usually through arguments, & are action is taken without consultation

partly committed to common goals

3. Actions, not Common interests recede into the background & parties see each other Deniable punishment behaviour; covert at- Self-help; external process guidance/

words as competitors; verbal communication is reduced & actions dominate tacks aimed at discrediting opponent facilitation

4. Images & Rumours spread, stereotypes & clichés are formed; the parties man- Loss of face through deliberate & continuous External process guidance/facilitation; ex-

coalitions oeuvre each other into negative positions & fight; a search for sup- offending of opponent’s honour ternal socio-therapeutic consultation

porters is sought

5. Loss of face Open & direct attacks ensue that aim to discredit the opponent Issuance of ultimatums & strategic threats External process guidance/facilitation; ex-

ternal socio-therapeutic consultation;

mediation

6. Strategies of Threats & counter threats increase; escalation of the conflict as a result Execution of ultimatums; attacks on oppo- External socio-therapeutic consultation;

threats of ultimatums nent’s sanction potential mediation; arbitration, court action

7. Limited destruc- Opponent no longer viewed as a person; limited destruction is con- Attacks at the core of opponent; effort to External socio-therapeutic consultation;

tive blows sidered an appropriate response & a benefit shatter opponent mediation; arbitration, court action; power

intervention

8. Fragmentation of Annihilate opponent; the destruction & dissolution of the hostile Giving up self-preservation drive; total de- Mediation; arbitration, court action; power

the enemy system is pursued intensively as a goal structiveness/war intervention

9. Together into the Total confrontation ensues; extermination of the opponent at the price Forcible/power intervention

From conflict to collaboration

abyss of self-extermination is seen & accepted

*In mediation a third party moderates between disputing parties, whereas in arbitration a third party listens to the concerns of both sides and reaches an independent decision.

485486 O. Soliku and U. Schraml

FIG. 1 Stages of conflict escalation and conflict management strategies (adapted from Glasl, , and Moore, ).

Our study focuses on the , km Mole National Park, proximity or remoteness to the Park, their ethnic background

which was gazetted as a National Park in and has had a and the availability or non-availability of Community

turbulent history that involved the forced eviction of whole Resource Management Areas in the communities. The iden-

communities from within the Park (Forestry Commission of tification and selection of information-rich cases in qualita-

Ghana, ). The Park’s enclosure of traditional hunting tive research ensures that individuals or groups of individuals

grounds, farmlands and sacred sites resulted in the loss of who are especially knowledgeable about or have an experi-

livelihoods and homes, fuelling resentment towards the ence with a phenomenon of interest are selected (Creswell

Park’s authorities. The turbulent history of the Park’s estab- & Plano Clark, ; Palinkas et al., ).

lishment, its effects on the socio-economic well-being of We used focus group discussions, in-depth interviews

c. , people and its present drive to curb depletion of and observations to ensure triangulation and validation of

forest and wildlife resources and encourage the participation information from the various sources, as prescribed for

of stakeholders in protected area management make it an case study research (Yin, ). At least two focus groups

ideal case study (Yin, ). were held in each community, with occupational and social

groups who had an interest in the Park and were often in

Methods conflict with Park authorities, including seven with farmers,

two with hunters, with women engaged in agro-based

Data collection small-scale industries, one with young people and three

with the elderly. Focus groups are ideal for research relating

A case study approach was adopted because of its appropri- to a group of people who share characteristics, such as occu-

ateness for addressing either a descriptive question (what pation, and experience the same group norms, meanings

happened?) or an explanatory question (how or why did and processes (Silverman, ). Focus groups comprised

something happen?), and also because it enables the re- adults $ years of age who resided in the communities.

searcher to examine a ‘case’ in-depth within its ‘real-life’ In the focus groups community members were invited to

context (Yin, , p. ). Data were collected during talk freely about actions of the managers of the Park that

October–December . Of the communities surround- they perceived as an impairment or conflict and about the

ing the Park (Fig. ) were selected, to provide a diverse factors that led to conflicts, to describe the extent of local

range of cases (Table ). A community in this context refers people’s involvement in co-management (including the

to a group of people who live within a defined geographical forms this involvement took and their roles and responsibil-

area, share the same values and customs, and are subject to a ities in such arrangements), and how this co-management

chief. Thus, communities were selected based on their arrangement may have helped reduce incidents of conflict

Oryx, 2020, 54(4), 483–493 © 2018 Fauna & Flora International doi:10.1017/S0030605318000285

Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. IP address: 82.12.2.223, on 06 Sep 2020 at 19:38:20, subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms

. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0030605318000285From conflict to collaboration 487

FIG. 2 Mole National Park, showing the

surrounding communities and study

communities.

and how co-management could be improved to enhance field work. Interview questions depended on the roles of

conflict management. the interviewees in co-management in the Park. Questions

In-depth interviews were also conducted with Tendanas generally focused on individual roles, co-management

(the local customary authority overlooking land issues in processes, the contribution of co-management to reducing

Northern Ghana), chiefs of the communities, local govern- conflicts and how co-management could be improved to

ment representatives in the communities, Park officials enhance conflict management. In-depth interviews were

and representatives of environmental NGOs working generally used as a follow up to focus group discussions:

in the area. Participants were purposefully selected issues that were raised during the focus groups were probed

(Creswell & Plano Clark, ). Tendanas and chiefs further, for depth and details (Morgan, ).

were selected as they are knowledgeable about the history,

culture and values of the communities (Tonah, ).

Environmental NGOs were selected to provide information Data analysis

on their role in facilitating co-management initiatives and

the influence of these initiatives on conflict management. In total, focus groups were held and interviews con-

In addition, secondary data were collected from policy ducted. Focus groups and some interviews with local leaders

documents, Park management reports and constitutions of were conducted in the native languages of the various ethnic

co-management boards, and from observations during our groups of the participants, with the help of translators.

These interviews and discussions were recorded, with the

consent of all participants, and translated and transcribed

TABLE 2 Characteristics of the selected study communities into English. Focus groups lasted – minutes. The tran-

(Fig. ). scripts were analysed using an inductive approach in which

we allowed the research findings to emerge from the fre-

Community Resource Distance from

quent, dominant or significant themes inherent in the

Community Ethnicity Management Area Park (km)

data (Thomas, ). Using Glasl’s () definition of con-

Murugu Hanga Yes 4.8

flict and conflict escalation model and Moore’s () clas-

Mognori Hanga Yes 0.3

Larabanga Kamara No 0.2

sification of conflict management strategies, we identified

Bawena Hanga No 5.0 texts representing actions perceived as impairments, sources

Grupe Vagla No 0.5 of impairment, impairment experienced, characteristics of

Kananto Gonja No 0.1 conflict escalation and conflict management strategies,

Jelinkon Vagla Yes 6.9 which we then coded.

Jang Vagla No 3.8 Data obtained from secondary sources and observation

Yazori Hanga No 12.0 were reviewed and analysed based on relevant themes

Ducie Chakali No 7.5

such as co-management in the Park and the history of the

Oryx, 2020, 54(4), 483–493 © 2018 Fauna & Flora International doi:10.1017/S0030605318000285

Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. IP address: 82.12.2.223, on 06 Sep 2020 at 19:38:20, subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms

. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0030605318000285488 O. Soliku and U. Schraml

study area. Connections were then drawn between the ana-

Loss of human life; broken homes as a result of imprison-

ment of hunters; animosity between Park officials & local

come; inability to perform cultural & spiritual rites at sa-

loss of sacred groves; animosity between Park officials &

Limited information sharing by Mole National Park; inadequate Increased conflicts; declining resources outside Park; in-

Loss of raw materials to sustain livelihoods; reduced in-

lysis of the focus groups and interviews and the secondary

Loss of farmlands & denial of customary land rights;

sources and observation data to arrive at the contributions

Loss of food crops & livestock; reduced income;

of co-management in mitigating conflicts.

TABLE 3 Community perspectives of the actions or behaviours of Mole National Park officials perceived as impairment, sources of impairment, and impairment experienced.

Less land for farming; smaller crop yields

Results

food insecurity; increased poverty

Perception of conflicts

people; increased poverty

Actions that community members perceived as impairment,

Impairment experienced

as articulated in the focus groups, primarily concerned their

livelihoods, with problems such as loss of food crops, re-

engagement & involvement of communities in Park management creased poverty

duced incomes, food insecurity, increased poverty, less

local people

cred groves

land for farming, and loss of raw materials to sustain liveli-

hoods (Table ). These impairments were blamed on un-

clear Park boundaries, overlapping land claims, need for

income and an absence of a policy on compensation.

Unclear Park boundaries; overlapping land claims; encroachment

Interviews with Park officials revealed four key behaviours

government-led centralized management approach employed at

Absence of policy on crop compensation; less land for farming

Need for shea nuts, medicinal plants & other NTFPs; need for

Lack of consultation with chiefs in establishment of the Park;

of surrounding communities perceived as impairment to

Economic hardship as a result of poverty & insufficient jobs;

need for income and for meat for household consumption

conservation and the Park’s objectives (Table ), mainly re-

lated to issues that threatened the destruction of forest and

wildlife species and the degradation of the environment.

income; need to perform cultural & spiritual rites

Source of impairment (antecedent conditions)

Contribution of co-management to conflict prevention leading to siting of farms close to Park

and management

We categorized and analysed conflicts (perceived impair-

the time of Park establishment

ments) described by community members and Park officials

according to the characteristics of the stages of Glasl’s con-

flict escalation model. The stages of conflict escalation there-

of farming into Park

fore do not necessarily represent the sequence in which the

conflicts occurred. However, interviews with Park managers

revealed that conflict management strategies were executed

at the same time with all communities, which suggests that

most conflicts might have occurred contemporaneously.

Nonetheless, the magnitude of the conflicts differed, as

communities without Community Resource Management

impairment

Areas received no economic compensation for loss of

Ranking of

their livelihoods and hence had negative attitudes towards

Park authorities. Table presents conflict situations, the

1

2

3

4

5

6

stage of escalation of the conflict, conflict management

strategies employed (Moore, ) and how co-

Restricted access to Park & its resources

Forced eviction & resettlement of some

Extension of Park’s boundaries in 1971

Arrests & killing of hunters engaged in

Non-compensation for raided farms &

& 1992 to its current size of 4,577 km2

Views of local communities not incor-

management contributes to managing conflicts in the

Park. All of Moore’s conflict management strategies are em-

porated in Park’s management

Action/behaviour perceived as

ployed in the Park except arbitration. However, in addition

to the strategies presented by Moore, we included provision

surrounding communities

of incentives, which was a key conflict management strategy

employed in the Park. Using Glasl’s conflict escalation

model as an analytical tool, we found that characteristics de-

loss of livestock

illegal hunting

scribed in the first, second and third stages of conflict were

impairment

present in conflict over restricted access to the Park, non-

compensation for raided farms, views of local people not in-

corporated in Park management, and encroachment into

Oryx, 2020, 54(4), 483–493 © 2018 Fauna & Flora International doi:10.1017/S0030605318000285

Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. IP address: 82.12.2.223, on 06 Sep 2020 at 19:38:20, subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms

. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0030605318000285From conflict to collaboration 489

TABLE 4 Park officials’ perspectives of actions or behaviours of surrounding communities perceived as impairment, sources of impairment,

and impairment experienced.

Action/behaviour per- Rank of most impor-

ceived as impairment tant impairment Source of impairment Impairment experienced

Encroachment of farming 1 Unclear Park boundaries; Destruction of forest species

into Park competing demands & interests;

overlapping land claims

Illegal killing of wildlife 2 Need for meat to sell for income Declining wildlife stock

Uncontrolled fire 3 Traditional farming practices; Destruction of forest & wildlife spe-

traditional methods of hunting & honey cies; degradation of environment

harvesting

Logging in/around Park 4 Limited staff to ensure effective patrols & Destruction of forest species

monitoring; sale to Chinese companies

the Park boundary. Participants in focus groups and inter- allowed to perform traditional rites inside the Park. These activities

do not harm wildlife or the forest, so the Park management is happy

views described how their standpoints at these various and we are also happy about this development.

stages of conflict clashed, yet the parties were not en-

trenched in their positions because of open dialogue and a In situations where deliberative processes are not employed

commitment to resolve the conflicts. They further attested and dialogue breaks down because of mistrust between par-

that conflict avoidance and the use of economic incentives ties, conflict could escalate to the fourth, fifth and sixth

were used as conflict management strategies in the first stage stages (Glasl, 1999). This is because conflict tends to be

of conflicts. An NGO official remarked: about gaining the upper hand and threatening the oppo-

nent, to force them in the desired direction (Glasl, 1999;

We realized that most of these conflicts are as a result of impacts on Moore, 2003). This proved to be the case in Mole

livelihoods, therefore conflict management should target the root National Park, where interviews with Park managers re-

cause, which is providing alternative livelihoods. In collaboration

with Park management, we have provided alternative livelihood vealed that when dialogue broke down, the Park recorded

sources in the form of beekeeping and community-based tourism, an increase in illegal activities as local people resorted to

which have provided income for households in those communities.

killing of wildlife, logging and uncontrolled bushfires in

For conflicts in the second stage, participants in focus the Park. To address these problems Park management

groups and interviews described how such conflicts were resorted to arrests and court actions, which often resulted

managed through negotiations between the parties. A in one party being aggrieved. This development further

Park official stated: triggered conflicts to escalate to the seventh, eighth and

ninth stages because of entrenched positions. Park officials

In a bid to make up for our inability to pay compensation for raided resorted to more coercive actions, including the use of the

farms, we have negotiated with community members whereby we offer

them training on preventive measures of keeping wildlife from destroy- police or armed patrol teams to force local people to con-

ing their farms. form to the Park’s laws. In an interview a Park official

When negotiations failed, NGO officials from A Rocha lamented:

Ghana served as mediators between the Park and local com-

The local people are armed, therefore our Park rangers are also armed

munities. A male farmer in Jelinkon said: and we also use the police to be able to counter any attacks during

patrols as such actions have resulted in deadly clashes in the past.

We have always been sceptical about the Park managers so when they

brought the idea that we form Community Resource Management

Areas and set aside part of our land for sustainable land use manage- Although these strategies sometimes helped to reduce illegal

ment, we thought it was another ploy to take more land from us and we activities inside the Park, they did not involve any co-

refused until A Rocha officials convinced us to do so.

management systems, as dialogue is almost impossible at

Conflict management strategies that involved open and this stage because of heightened tensions and loss of trust

transparent dialogue in the form of negotiation, mediation between parties.

and economic incentives were deemed by interviewees to re-

sult in positive outcomes because they resulted in mutual

benefits for both parties: local communities were able to sat- Discussion

isfy some of their socio-economic needs without comprom-

We found that the perception of conflict by surrounding

ising conservation goals. In Mognori a woman remarked:

communities was usually caused by an effect on local liveli-

Through deliberative processes, the Park management now allows us hoods, whereas Park administrators perceived conflict when

to collect shea nuts or fuel wood from the Park. Our chiefs are also they experienced impairment of conservation goals or a

Oryx, 2020, 54(4), 483–493 © 2018 Fauna & Flora International doi:10.1017/S0030605318000285

Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. IP address: 82.12.2.223, on 06 Sep 2020 at 19:38:20, subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms

. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0030605318000285. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0030605318000285

Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. IP address: 82.12.2.223, on 06 Sep 2020 at 19:38:20, subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms

490

O. Soliku and U. Schraml

TABLE 5 Conflict management strategies, contribution of co-management to conflict prevention and management and conflict outcomes.

Moore’s conflict

Action perceived as im- Stages of Glasl’s escalation management Contribution of co-management to conflict prevention &

pairment (conflict issues) model strategy management* Outcome for conflict

Restricted access to Park 1. Hardening Provision of eco- Working in collaboration with NGOs such as A Rocha Local communities were able to satisfy

nomic incentives; Ghana, alternative livelihood ventures have been provided some of their socio-economic needs

conflict avoidance to local people under the CREMA programme. These have without compromising conservation goals

provided income for communities & some households with

CREMAs, thereby improving household incomes.

Non-compensation for 2. Debates & polemics Negotiation Through PAMAU, communities were able to negotiate for This conflict management strategy re-

raided farms; the Park to grant access to groups (e.g. women & traditional sulted in mutual benefits for both parties

views of local people not authorities) upon a formal request to pick shea nuts &

incorporated in Park man- perform traditional or spiritual rites within the Park.

agement; In a bid to make up for their inability to pay compensation

Oryx, 2020, 54(4), 483–493 © 2018 Fauna & Flora International doi:10.1017/S0030605318000285

restricted access to Park for raided farms, Mole National Park through PAMAU

conducts training programmes with community members

on preventive measures for keeping wildlife off farms.

Restricted access to Park; 3. Actions not words Mediation A Rocha Ghana, through PAMAU, was able to mediate This conflict management strategy re-

encroachment into Park’s between the Park’s administrators & local communities to sulted in mutual benefits for both parties

boundaries get some communities to agree to form CREMAs & set aside

part of their land for sustainable land use management,

which also acts as a de facto buffer zone.

Illegal killing of wildlife; il- 4. Images & coalitions; Adjudication or Offenders are arraigned before a court where they are either This conflict management strategy re-

legal logging in Park; 5. Loss of face; 6. Strategies court action fined or imprisoned, or both. In this instance no co- sulted in benefits to only one party

uncontrolled fire of threat management efforts are employed as parties take entrenched

positions.

Illegal killing of wildlife; il- 7. Limited destructive blow; Non-violent direct As conflicts intensify, Park officials resort to more coercive No party derived any benefits from this

legal logging 8. Fragmentation of enemy action & violence actions, sometimes involving the use of the police or armed conflict management strategy

9. Together into the abyss patrol teams, who arrest offenders. In these instances, it is

impossible to use co-management systems as these conflicts

generate reprisal attacks.

*CREMA, Community Resource Management Area; PAMAU, Protected Areas Management Advisory Unit.From conflict to collaboration 491

flouting of rules. This suggests that actors will react when Regarding how co-management can be improved to en-

they experience impairment in their well-being (e.g. liveli- hance conflict management, we found that local knowledge,

hoods) or feel that their core values or interests, such as skills and practices were not incorporated into formal con-

maintaining conservation goals or traditional livelihoods, flict management strategies. Park officials expressed fear

are threatened. Conflicts over biodiversity often emerge that familiarity between local chiefs and local people could

from impacts on biodiversity, usually in response to an ef- undermine the fight against illegal activities in the Park, but

fect on local livelihoods or other triggers (Young et al., local chiefs believed they had better skills and knowledge to

), but incompatible values and interests can further es- manage conflicts by virtue of the respect and status they

calate such conflicts. For instance, in situations where com- enjoy in the communities. They further believed that tra-

munity members’ interests, such as hunting, were clearly at ditional norms, taboos and the fear of ostracism or gossip

variance with conservation goals, collaboration was impos- were more effective in keeping people from engaging in il-

sible, as acceding to this interest would undermine conser- legal activities and managing conflicts than Park laws and

vation goals. Therefore, conflict escalation as a result of imprisonment. Castro & Nielsen () attested that one

incompatible differences also resulted in the unwillingness of the major benefits of co-management is the opportunity

of parties to consider a negotiated agreement (Redpath it offers for incorporating local knowledge, skills and prac-

et al., ; Holland, ). tices into formal conflict management. Our interviews with

Regarding our second research question, which sought to stakeholders revealed that communities were represented

assess how co-management contributed to preventing con- on co-management boards as homogenous groups rather

flicts from escalating, we found that co-management is able than as specific resource groups. This can overshadow spe-

to contribute to conflict prevention and management in in- cific needs of different segments of the communities, includ-

stances where dialogue between conflicting parties and ing farmers, hunters and women, who all have different

third-party mediation are possible. This enables parties to interests in the use and management of the Park’s resources

openly discuss shared problems and agree on acceptable so- (Neumann, ; Engel & Korf, ). Park officials and

lutions (Redpath et al., ). However, the process of dia- NGO representatives, however, cited financial constraints

logue requires transparency and trust, without which for the inability to have all stakeholder groups from all

conflicts could escalate to a higher stage (Ansell & Gash, communities represented on such boards.

; Sandström et al., ). Successful conflict manage- Based on the two propositions of our study, we found

ment is based on the intensity or level of escalation of the that beyond their exclusion from decision making, actors

conflict (Yasmi et al., ). It is therefore necessary to perceived conflict when their socio-economic well-being

understand the context within which conflicts occur, as (livelihoods and social needs) or core values and interests

well as the dynamics of conflict escalation, to help anticipate (conservation goals) were threatened. Secondly, the involve-

the appropriate conflict management strategy. In the case of ment of key stakeholders in the form of co-management

Mole National Park most conflicts concerned livelihoods, helped to mitigate or prevent conflicts from escalating in

and therefore conflict management strategies such as provi- the first to third stages through open and transparent dia-

sion of economic incentives proved successful. In conson- logue in the form of negotiation, mediation and economic

ance with other findings (e.g. Castro & Nielsen, ; De incentives.

Pourcq et al., ; Ho et al., ), we found that economic We focused on assessing the contribution of co-

incentives were used both to encourage local people to par- management to conflict mitigation in the context of pro-

ticipate in co-management arrangements and as a strategy tected areas, and have shown that involving stakeholders,

for preventing and managing conflict. Community-based including surrounding communities, in co-management

co-management initiatives that provided economic incen- that involves open and transparent dialogue in the form of

tives were a key factor in variations among surrounding negotiation, mediation and economic incentives can influ-

communities regarding the level of conflict escalation and ence successful conflict management. However, the success

the contribution of co-management in conflict mitigation. of co-management in preventing conflicts from escalating is

Communities that were not beneficiaries of community- dependent on a number of factors. Key among them is to

based co-management expressed negative attitudes towards first understand the context in which protected area con-

Park officials as these communities did not benefit from flicts occur, which includes determining which actions ac-

economic incentives such as alternative livelihoods and eco- tors perceive to be impairments and what the sources of

tourism although their livelihoods had been affected by con- those impairments are. This is important in identifying

servation. Although the Community Resource Management what actors’ experienced impairments are, which then de-

Areas initiative is a laudable venture, it has resulted in min- termines what form co-management should take to address

imal economic effect in the area, as not all surrounding those impairments. To ensure sustainable co-management

communities are beneficiaries because of inadequate fund- it is important to incorporate local knowledge, ensure stake-

ing by the state. holder representativeness and maintain dialogue among

Oryx, 2020, 54(4), 483–493 © 2018 Fauna & Flora International doi:10.1017/S0030605318000285

Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. IP address: 82.12.2.223, on 06 Sep 2020 at 19:38:20, subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms

. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0030605318000285492 O. Soliku and U. Schraml

stakeholders while ensuring trust and transparency F O R E S T R Y C O M M I S S I O N O F G H A N A () Wildlife Division Policy for

throughout the conflict management process. Collaborative Community Based Wildlife Management. Wildlife

Division of Forestry Commission, Accra, Ghana. Https://www.

fcghana.org/assets/file/Publications/Wildlife%Issues/wd_policy_

collaborative_community.pdf [accessed June ].

Acknowledgements This paper was written as part of the PhD

F O R E S T R Y C O M M I S S I O N O F G H A N A () Mole National

study of OS, with a scholarship from the Deutscher Akademischer

Management Plan, –. Unpublished report. Wildlife

Austauschdienst and a travel grant from Müller-Fahnenberg-

Division of Forestry Commission, Accra, Ghana.

Stiftung. We thank two anonymous reviewers for their useful

G L A S L , F. () Confronting Conflict: A First-aid kit for Handling

comments.

Conflict. Hawthorn Press, Stroud, UK.

H O , N.T.T., R O S S , H. & C O U T T S , J. () Can’t three tango? The role

of donor-funded projects in developing fisheries co-management in

Author contributions Conceptualization and design: OS; data

the Tam Giang Lagoon system, Vietnam. Ocean & Coastal

collection, analysis and interpretation: OS, US; writing and revision:

Management, , –.

OS, US.

H O L L A N D , A. () Philosophy, conflict and conservation. In

Conflicts in Conservation: Navigating Towards Solutions (eds

S.M. Redpath, R.J. Gutierrez, K.A. Wood & J.C. Young), pp. –.

Conflicts of interest None. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK.

M A R F O , E. & S C H A N Z , H. () Managing logging compensation

payment conflicts in Ghana: understanding actor-empowerment

Ethical standards This research abided by the Oryx Code of and implications for policy intervention. Land Use Policy, ,

Conduct. Formal approval and permits were sought from the –.

Wildlife Division of the Forestry Commission of Ghana before com- M AT E O -T O M Á S , P., O L E A , P.P., S Á N C H E Z ‐B A R B U D O , I.S. & M AT E O ,

mencement of the research. Free, prior and informed consent was R. () Alleviating human–wildlife conflicts: identifying the

sought from community members and other stakeholders before causes and mapping the risk of illegal poisoning of wild fauna.

focus group discussions and interviews. Journal of Applied Ecology, , –.

M I N G ’ AT E , F.L.M., R E N N I E , H. & M E M O N , A. () Potential for

co-management approaches to strengthen livelihoods of forest

References dependent communities: a Kenyan case. Land Use Policy, ,

–.

A N S E L L , C. & G A S H , A. () Collaborative governance in theory and M O O R E , C.W. () The Mediation Process: Practical Strategies for

practice. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, , Resolving Conflict. rd edition. Jossey-Bass Wiley, San Francisco,

–. USA.

B E R K E S , F. () Evolution of co-management: role of knowledge M O R G A N , D.L. () Focus Groups as Qualitative Research. Sage

generation, bridging organisations and social learning. Journal of Publications, Thousand Oaks, USA.

Environmental Economics and Management, , –. NEUMANN, R. () Primitive ideas: protected area buffer zones and the

B U T L E R , J.R.A. () The challenge of knowledge integration in the politics of land in Africa. Development and Change, , –.

adaptive comanagement of conflicting ecosystem services provided P A L I N K A S , L.A., H O R W I T Z , S.M., G R E E N , C.A., W I S D O M , J.P., D U A N ,

by seals and salmon. Animal Conservation, , –. N. & H O A G WO O D , K. () Purposeful sampling for qualitative

C A S T R O , A.P. & N I E L S E N , E. () Indigenous people and data collection and analysis in mixed method implementation

co-management: implications for conflict management. research. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental

Environmental Science & Policy, , –. Health Services Research, , –.

C H E N , H., S H I VA KO T I , G., Z H U , T. & M A D D O X , D. () Livelihood P L U M M E R , R., C R O N A , B., A R M I TA G E , D.R., O L S S O N , P., T E N G Ö , M. &

sustainability and community based co-management of forest Y U D I N A , O. () Adaptive comanagement: a systematic review

resources in China: changes and improvement. Environmental and analysis. Ecology and Society, , .

Management, , –. P R U I T T , D.G., R U B I N , J.Z. & K I M , S.H. () Social Conflict:

C O S E R , L.A. () Social conflict and the theory of social change. The Escalation, Stalemate and Settlement. McGraw-Hill Series in Social

British Journal of Sociology, , –. Psychology. McGraw-Hill, New York, USA.

C R E S W E L L , J. W. & P L A N O C L A R K , V. L. () Designing and Conducting R E D P AT H , S.M., B H AT I A , S. & Y O U N G , J. () Tilting at wildlife:

Mixed Methods Research. nd edition. Sage Publications, Thousand reconsidering human–wildlife conflict. Oryx, , –.

Oaks, USA. R E D P AT H , S.M., Y O U N G , J., E V E LY , A., A D A M S , W.M., S U T H E R L A N D ,

D E P O U R C Q , K., T H O M A S , E., A R T S , B., V R A N C K X , A., L É O N -S I C A R D , W.J., W H I T E H O U S E , A. et al. () Understanding and

T. & V A N D A M M E , P. () Conflict in protected areas: who says managing conservation conflicts. Trends in Ecology & Evolution, ,

co-management does not work? PLoS ONE, , e. –.

D I C K M A N , A. () Complexities of conflict: the importance of S A N D S T R Ö M , A., C R O N A , B. & B O D I N , Ö. () Legitimacy in

considering social factors for effectively resolving human–wildlife co-management: the impact of preexisting structures, social

conflict. Animal Conservation, , –. networks and governance strategies. Environmental Policy and

E N G E L , A. & K O R F , B. () Negotiation and Mediation Techniques Governance, , –.

for Natural Resource Management. Food and Agriculture S I LV E R M A N , D. () Doing Qualitative Research. th edition. Sage

Organization of the United Nations, Rome, Italy. Https:// Publications, Thousand Oaks, USA.

peacemaker.un.org/sites/peacemaker.un.org/files/Negotiation T H O M A S , D.R. () A general inductive approach for analysing

andMediationTechniquesforNaturalResourceManagement_ qualitative evaluation data. American Journal of Evaluation, ,

FAO.pdf [accessed June ]. –.

Oryx, 2020, 54(4), 483–493 © 2018 Fauna & Flora International doi:10.1017/S0030605318000285

Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. IP address: 82.12.2.223, on 06 Sep 2020 at 19:38:20, subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms

. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0030605318000285From conflict to collaboration 493

T O N A H , S. () The politicisation of a chieftaincy conflict: the case of empirical experience in Indonesia. PhD thesis. Wageningen

Dagbon, northern Ghana. Nordic Journal of African Studies, , University, Wageningen, The Netherlands.

–. Y A S M I , Y., S C H A N Z , H. & S A L I M , A. () Manifestation of conflict

T R E V E S , A. & K A R A N T H , K.U. () Human–carnivore conflict and escalation in natural resource management. Environmental Science

perspectives on carnivore management worldwide. Conservation and Policy, , –.

Biology, , –. Y I N , R.K. () Case Study Research: Design and Methods. Sage

V E L D E D , P., J U M A N E , A., W A P A L I L A , G. & S O N G O R WA , A. () Publications, Thousand Oaks, USA.

Protected areas, poverty and conflicts. A livelihood case study of Y O U N G , J.C., M A R Z A N O , M., W H I T E , R.M., M C C R AC K E N , D.I.,

Mikumi National Park, Tanzania. Forest Policy and Economics, , R E D P AT H , S.M., C A R S S , D.N. et al. () The emergence of

–. biodiversity conflicts from biodiversity impacts: characteristics and

VODOUHE, F.G., C O U L I B A LY , O., A D E G B I D I , A. & S I N S I N , B. management strategies. Biodiversity and Conservation, ,

() Community perception of biodiversity conservation –.

within protected areas in Benin. Forest Policy and Economics, , Z A C H R I S S O N , A. & L I N D A H L , K.B. () Conflict resolution

–. through collaboration: preconditions and limitations in forest

Y A S M I , Y. () Institutionalisation of conflict capability in the and nature conservation controversies. Forest Policy and Economics,

management of natural resources. Theoretical perspectives and , –.

Oryx, 2020, 54(4), 483–493 © 2018 Fauna & Flora International doi:10.1017/S0030605318000285

Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. IP address: 82.12.2.223, on 06 Sep 2020 at 19:38:20, subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms

. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0030605318000285You can also read