EVALUATING VOCATIONAL TERTIARY EDUCATION PROGRAMS IN A SMALL REMOTE COMMUNITY IN AOTEAROA, NEW ZEALAND

←

→

Page content transcription

If your browser does not render page correctly, please read the page content below

Journal of Community Engagement and Higher Education Volume 9, Number 2

EVALUATING VOCATIONAL TERTIARY EDUCATION

PROGRAMS IN A SMALL REMOTE COMMUNITY IN

AOTEAROA, NEW ZEALAND

Heather Hamerton and Sharlene Henare

Toi Ohomai Institute of Technology

Abstract

Tertiary vocational programs offered in a small remote town in Aotearoa, New Zealand, were delivered

in partnership with indigenous community organizations and other stakeholders to prepare people for

future regional developments in primary industries. An evaluation investigated the impact of these pro-

grams on students, their families, and the community. Qualitative interviews and focus groups were con-

ducted with staff, students, and community stakeholders. Student outcomes were high across all pro-

grams evaluated. Participants attributed the high success rate for students, the majority of whom were

indigenous, to the strong relationships developed and fostered between community people, students, and

teaching staff and to the relevance of the programs with clear links to the region’s economic develop-

ment goals. They emphasized the importance of educational pathways from school into tertiary educa-

tion. Tertiary study impacted not only the students, many of whom were previously disengaged from

education, but also their extended families. The evaluation confirmed the value of partnering with com-

munities to deliver vocational education that meets their identified needs.

Keywords: vocational education, indigenous education, second chance education, community

partnerships, educational evaluation

BACKGROUND ciated the opportunity to study close to home,

were highly motivated to succeed, and appreci-

ated the close and supportive relationships with

Most tertiary education organizations in their tutors (Watt & Gardiner, 2016).

Aotearoa, New Zealand, are situated in larger The evaluation reported here focused

cities and provincial towns, although increas- on programs offered in Ōpōtiki, approximately

ingly, many of these institutions also offer edu- a two-hour drive from the two main campuses.

cational programs in smaller and more remote In making decisions about which programs to

settings. Toi Ohomai Institute of Technology1 is offer in this location, the institution worked

a large regional institute of technology with closely with community organizations that re-

campuses in two provincial cities, delivering a ported that many young people were leaving

broad range of vocational, technical, and pro- school without qualifications, and that many

fessional programs. In addition to programs wanted to stay close to family, but needed to

taught from its urban campuses, the organiza- learn basic and job-related skills. The programs

tion has been delivering programs in more rural have been delivered in partnership with several

and remote areas for many years. An earlier Māori2 organizations and stakeholder groups

study of barriers and enablers to study for stu- including the local high school. They were cho-

dents studying away from our organization’s sen to prepare local people to work in local em-

main campus found that students greatly appre- ployment, and also to re-engage youth. Further

1

Toi Ohomai Institute of Technology is a new institution in the Bay of Plenty, created in May 2016 from the mer-

ger of Bay of Plenty Polytechnic in Tauranga and Waiariki Institute of Technology in Rotorua.

2

Māori are the indigenous people of Aotearoa, New Zealand.

30

© Journal of Community Engagement and Higher Education

Copyright © by Indiana State University. All rights reserved. ISSN 1934-5283Journal of Community Engagement and Higher Education Volume 9, Number 2

information about the changing nature of em- mated that the harbor development project will

ployment in Ōpōtiki is provided below. create up to 450 new jobs, provide a seven-fold

Delivery has differed for the various return on investment and indirectly result in

courses. For the most part, tutors have travelled improved social statistics for the district

from the main campuses to teach, with student (Ōpōtiki District Council, 2015).

support offered by local organizations. Block These planned developments have im-

courses have also been offered, for example in plications for education and training. The Bay

horticulture, to ensure programs meet the needs of Plenty Tertiary Intentions Strategy 2014-

of full-time employees in the kiwifruit industry. 2019 (Bay of Connections, 2014a) notes the

In the 2013 Census, 8,436 people re- importance of delivering relevant trade and in-

ported living in the Ōpōtiki district, of whom dustry training locally in the Eastern Bay of

approximately 50% live in the town itself Plenty, and of engaging “second-chance” learn-

(www.stats.govt.nz). Approximately 60% of the ers in tertiary education. “Second chance” edu-

population are Māori; unemployment is higher cation refers to alternatives to regular school

than the New Zealand average at 11% (Buchan that provide opportunities for people who did

& Wyatt, 2012). Age group profiles show a not complete school to re-engage in education

drop in numbers of young people aged 25-40, (Ross & Gray, 2005; te Riele, 2000). Students

as many people leave the district for study and drop out of school for a variety of reasons,

employment (www.stats.govt.nz). These trends sometimes because of personal or social cir-

are similar to those found in rural areas in other cumstances, but also because of school-related

Western countries, such as the United Kingdom factors (McGregor, Mills, te Riele, & Hayes,

(Jamieson, 2000) and Australia (Hugo, 2002), 2015; Ross & Gray, 2005). School structures do

with American researchers noting that follow- not suit all students; indigenous students may

ing the global recession in 2007-9, rural em- be particularly disadvantaged (Ross & Gray,

ployment in the U.S.A. fell dramatically and 2005).

has not yet recovered (https:// In addition, the Māori Economic Devel-

www.ers.usda.gov/topics/rural-economy- opment Strategy (Bay of Connections, 2014b)

population/employment-education/rural- calls for the alignment of training to regional

employment-and-unemployment/). market needs, a focus on pathways and transi-

As in many rural areas, the local econo- tions from school into employment and train-

my in Ōpōtiki is mostly driven by primary in- ing, and alignment of tertiary education provi-

dustries like agriculture, horticulture, forestry, sion with the needs of Māori organizations. In-

and fishing (Buchan & Wyatt, 2012). Both the vestment in people generally and youth in par-

median income for working-age people and the ticular is seen as vital to the region’s economic

number of people with formal qualifications are growth (Hudson & Diamond, 2014). Our insti-

lower than the national average tution has the opportunity to contribute to this

(www.stats.govt.nz). development through providing educational

Despite being classified as an area of opportunities that will assist in workforce de-

high deprivation (Atkinson, Salmond, & velopment toward expansion in horticulture,

Crampton, 2014), Ōpōtiki is a small town with marine farming, and the harbor development.

big dreams. Local Māori are a majority share- The New Zealand Tertiary Education

holder in a large aquaculture venture 8.5 km off Strategy 2014-2019 (Ministry of Education,

the coast, which in 2016 began to produce mus- 2014) has “delivering skills for industry” (p. 9)

sels and mussel spat in commercial quantities. as its first priority. The challenge for tertiary

To assist with the processing of mussels, the education providers is to ensure that students

local authority plans to develop the local river have access to skills that will lead to career op-

mouth into a harbour with wharf and marina. portunities. To support this priority, six voca-

Local and central government will finance this tional pathways have been introduced with the

development (Ōpōtiki District Council, 2015). goal of improving students’ ability to move

In the future, mussels will be brought ashore for through education and into employment (http://

processing in a plant to be built adjacent to the youthguarantee.net.nz/vocational-pathways/the-

harbor. It is anticipated that from 2021, a large six-vocational-pathways/). However, as re-

and growing volume of mussels will be able to searchers have pointed out, the pathways that

be processed in Ōpōtiki. The council has esti- young people follow between study and work

31

© Journal of Community Engagement and Higher Education

Copyright © by Indiana State University. All rights reserved. ISSN 1934-5283Journal of Community Engagement and Higher Education Volume 9, Number 2

are very often complex and non-linear (Ross & education in remote settings away from larger

Gray, 2005; te Riele, 2000). Students want to campuses is often quite different from on-

know that their chosen programmes of study campus education. Students living in rural areas

will bring them good prospects of desirable em- are likely to be subject to a number of stresses

ployment, meaning that education must be de- (Owens, Hardcastle, & Richardson, 2009).

mand-driven rather than supply-driven (Watts, Challenges such as family pressures, violence,

2009). In addition, because of the changing la- poverty, and associated financial concerns are

bour market, job seekers need to actively man- also found in urban communities, but in rural

age their skills acquisition (Vaughan, Roberts, settings like Ōpōtiki, these are compounded by

& Gardiner, 2006) and ensure they develop isolation and lack of employment and education

flexible and transferable skills such as social opportunities (Hill, 2014). In addition, rural

skills and confidence (McGregor et al., 2015; schools can experience difficulty in attracting

Ross & Gray, 2005). Very often they do this via high-calibre teachers (Gallo & Beckman, 2016).

non-linear or spiral pathways (Ross & Gray, Opportunities for tertiary education are not al-

2005). ways readily available close to home, meaning

Changes have occurred rapidly in both students will need to move away or travel in

education and employment, with knowledge order to study.

increasingly available through technology; In rural areas of New Zealand, it can be

learners require skills in appraising the value of common for young people, particularly those

this readily available knowledge (Siemens, who have successfully completed school quali-

2005) and in transferring what they learn into fications, to move away to continue their educa-

the workplace (Eraut, 2004). However, educa- tion at tertiary level (Bay of Connections,

tional institutions are not always connected with 2014a). Similar trends have been described

the workplaces their graduates will encounter, elsewhere. For example, Lynne Jamieson

hence a call for better connections between (2000) in her study of youth in rural Scotland

these sectors (Fredman, 2013; Helms Jørgen- found that around half of school leavers moved

sen, 2004). away once they left school, especially those of

It is unlikely in such a rapidly changing higher social class. However, she also reported

world that formal education can provide all of that participants’ reasons for staying or going

the learning required for employment success. were complex, and related to family and com-

Increasingly, learning opportunities are being munity ties, as well as better job prospects and

made available in workplaces, through such education available elsewhere. Attachment to a

mechanisms as internships, work placements, place influenced people’s decisions to stay in

and work-integrated learning (Billett, 2004; their community (Jamieson, 2000). It is likely

Cooper, Orrell, & Bowden, 2010; Guile & Grif- that students in Ōpōtiki will have similar pat-

fiths, 2001). Employers want graduates who are terns, with some moving away for study or em-

employable, work-ready, and able to engage in ployment, and others staying because of family

continuous skill development (Cooper et al., ties and attachment to the place. Students from

2010). Māori communities have strong ties to particu-

Researchers have noted that youth are lar localities, as well as extended family and

critical to the sustainable future of communities community obligations that will affect decisions

(Henderson, 2016), and have called for educa- to move away for study, and to return.

tion institutions to align themselves more close- Bambrick (2002) has reported that in

ly with local communities as one strategy in Australia, satellite campuses are pedagogically

meeting local employment needs (Ministry of and financially challenging. Students in remote

Business, 2015). However, Australian research- areas may be disadvantaged, are often indige-

ers have reported that the links between educa- nous (Bambrick, 2002; Thomas, Ellis, Kirkham,

tion and work are not straightforward or simple, & Parry, 2014), and may have additional stress-

with many young people finding it difficult to es in their lives, such as poverty, violence, or

make this transition (Cuervo & Wyn, 2016). family commitments (Owens et al., 2009). As

tertiary institutions work to improve access to

Tertiary Education at a Distance education in more remote areas, many of the

students are likely to be vulnerable learners

Researchers have noted that tertiary who may not have previously experienced suc-

32

© Journal of Community Engagement and Higher Education

Copyright © by Indiana State University. All rights reserved. ISSN 1934-5283Journal of Community Engagement and Higher Education Volume 9, Number 2

cess in education. Many are unable to move with students (C. Morgan, 2001; Owens et al.,

away to study because of cost and other com- 2009; Phipps & Merisotis, 1999).

mitments (Bambrick, 2002; May, 2009; To ensure success, tertiary education

McMurchy-Pilkington, 2009). providers need to work in partnership with

In New Zealand, there has been a call communities (Cortese, 2003; Hohepa, Jenkins,

for institutions to improve access to tertiary ed- Mane, Sherman-Godinet, & Toi, 2004; Tarena,

ucation, in particular for Māori students, and to 2013; Thomas et al., 2014) and engage families

create an environment that is suitable for a di- (Johnstone & Rutgers, 2013). They also need to

verse student population (Bay of Connections, work closely with local schools (Johnstone &

2014a). There is a need for flexible delivery Rutgers, 2013; O’Sullivan, 2007; Thomas et al.,

(Bambrick, 2002), and organizations need to 2014) and ensure scaffolding from school to

respond proactively to the diverse needs of stu- tertiary while providing students with clear in-

dents (Whiteford, Shah, & Nair, 2013). For in- formation about career pathways (Bidois, 2013;

stance, research has demonstrated that indige- Johnstone & Rutgers, 2013; May, 2009; Thom-

nous students are more likely to succeed in en- as et al., 2014).

vironments where their own culture is reflected,

and where they have opportunities to establish Māori and Indigenous Tertiary Educa-

relationships of trust with their teachers tion

(Bishop, Berryman, Cavanagh, & Teddy, 2009). Researchers have reported that organi-

They also prefer classrooms in which learning zations need to ensure that programs are learner

of theory is closely followed by opportunities -centered and meet students’ literacy and nu-

for putting this theoretical learning into practice meracy needs (McMurchy-Pilkington, 2009;

(Fraser, 2016). It is important for providers to Skill New Zealand, 2001). For indigenous stu-

be responsive (Skill New Zealand, 2001), flexi- dents, it will be important that programs also

ble, and open (Hoffman, Whittle, & Bodkin- meet their cultural needs by allowing them to

Allen, 2013; Thomas et al., 2014). Researchers express themselves in their own language, cre-

have noted a need for dialogue between provid- ating reciprocal and respectful relationships,

ers and community to ensure programs match and ensuring they can see themselves and their

local needs (A. Morgan, Saunders, & Turner, lives reflected in the curriculum (Bishop et al.,

2004). 2009; McCarty & Lee, 2014; Skill New Zea-

Smaller campuses often have smaller land, 2001). New Zealand research notes the

classes and enthusiastic staff (Bambrick, 2002; importance of Māori pedagogies and values in

May, 2009). Although some researchers have programs where there are high numbers of

observed that distance students are more likely Māori students (Bidois, 2013; May, 2009;

to drop out (Owens et al., 2009; Phipps & Mayeda, Keil, Dutton, & Ofamo’oni, 2014).

Merisotis, 1999), others note that students often Māori pedagogy places a high value on rela-

perform better (Bambrick, 2002) and that im- tionships, both between students and teacher

proving access does not necessarily have a neg- and amongst students. Other important factors

ative impact on academic standards (Whiteford are group work, multisensory approaches, and

et al., 2013). Experiencing success close to reflection (Stucki, 2010). Māori pedagogies

home may inspire some students to continue such as the Te Kotahitanga approach challenge

their study away from home on a larger cam- deficit thinking and ensure Māori students have

pus; moving to campus requires commitment positive learning experiences that use and rein-

and support (Thomas et al., 2014). force Māori cultural values (Bishop et al.,

Undoubtedly, students studying remote- 2009).

ly have a different experience from on-campus Research in New Zealand and Australia

students (Bambrick, 2002), and isolation can be has found that in the classroom, indigenous stu-

a barrier (Owens et al., 2009). They need a real- dents will be more likely to suceed in a family-

istic, authentic environment and a sense of be- like atmosphere where they feel a sense of be-

longing (Owens et al., 2009). Support and tech- longing (Hoffman et al., 2013; McMurchy-

nology are seen as important factors (Owens et Pilkington, 2009; Owens et al., 2009). Unsur-

al., 2009; Thomas et al., 2014), as are teachers prisingly, New Zealand’s Ministry of Education

who are enthusiastic and skilled communica- (2015) has found that for Māori students, better

tors, and willing to establish good relationships qualifications lead to better employment out-

33

© Journal of Community Engagement and Higher Education

Copyright © by Indiana State University. All rights reserved. ISSN 1934-5283Journal of Community Engagement and Higher Education Volume 9, Number 2

comes, and therefore improve income levels. In Lack of success for Māori at school has

addition, Māori with post-school qualifications been attributed to colonization and to an educa-

are more likely to live longer (Ministry of Edu- tion system that has functioned to reproduce

cation, 2015). Historically there has been a sig- European culture and marginalize Māori

nificant gap in tertiary education participation (Walker, 2004). Other writers have similarly

and achievement between Māori and non-Māori noted that indigenous students are disadvan-

as a result of colonization and hegemonic his- taged in mainstream schooling (Ross & Gray,

torical expectations that Māori will assimilate 2005). Researchers have also found that many

themselves to a Western education system. Ed- young people are likely to engage in more

ucation in both schools and tertiary institutions meaningful learning away from schools, learn-

in New Zealand has for the most part followed ing generic life skills and vocational job-related

a monocultural model both in the curriculum skills (McGregor et al., 2015; Sanguinetti, Wa-

and in pedagogical practices (Bishop et al., terhouse, & Maunders, 2005). In a rapidly

2009; Walker, 2004). As a result, Māori changing globalised world, the skills and attrib-

achievement has lagged behind that of non- utes needed for work are changing also. Rather

Māori for many years (Walker, 2004). Ministry than blaming students who drop out or are ex-

of Education (2015) statistics show that Māori cluded from school because of structural fac-

tertiary completions have increased from 20% tors, it is important to design learning environ-

in 2007 to 30% in 2014, but non-Māori comple- ments that are student-centered, with high-

tions during this period increased from 40% to quality teachers (te Riele, 2000), and a curricu-

50%. The 20% gap between Māori and non- lum that is holistic and flexible (Sanguinetti et

Māori completions remains. Other measures of al., 2005) and allows students to choose and

success are also important for Māori. Colleen negotiate their study (McGregor et al., 2015).

McMurchy-Pilkington (2009) reported tertiary Researchers have found that in the right kind of

students gained important social skills and soft environment with more reasonable rules, and in

skills such as self-confidence. Successful stu- which they are treated like adults, youth, in-

dents also become role models for others in cluding indigenous youth, will reengage suc-

their families and communities (McMurchy- cessfully with education (McMurchy-

Pilkington, 2009; Thomas et al., 2014). Pilkington, 2009; te Riele, 2000, 2007). In cre-

Students need to develop skills for em- ating such an environment, researchers have

ployment and also skills that equip them for emphasized the importance of teachers creating

life, so provision of real-life experiences is im- trusting relationships with students, being will-

portant (Hoffman et al., 2013; McMurchy- ing to listen, and providing them with support

Pilkington, 2009). Other factors that affect edu- (McGregor et al., 2015; Sanguinetti et al., 2005;

cational outcomes are student support (Hoffman te Riele, 2000).

et al., 2013; Johnstone & Rutgers, 2013; May,

2009) and good relationships with passionate Evaluating Educational Impact

tutors who are culturally aware (Hoffman et al.,

2013; May, 2009; McMurchy-Pilkington, Self-assessment and evaluation are im-

2009). portant for tertiary education providers commit-

Many students in remote centers are ted to continuous self-improvement to achieve

likely to be “second chance learners.” In talking excellent student outcomes (Alzamil, 2014;

about indigenous students in several New Zea- Burnett & Clarke, 1999) and drive change and

land contexts, Stephen May (2009) reports: transformation (Cortese, 2003; Fiddy & Peeke,

1993; Law, 2010). Although the most common

Those tertiary programs in kind of evaluation within education is course

which they are involved thus evaluation (Burnett & Clarke, 1999; Stein et al.,

represent for many of these sec- 2012), the Ako Aotearoa National Centre for

ond-chance adult Māori learn- Tertiary Teaching Excellence website

ers their first unqualified expe- (www.akoaotearoa.ac.nz) reveals a growing

rience of educational achieve- number of both workshops on evaluation and

ment/success and give them the reports of evaluations mostly driven by a desire

confidence to continue with for program improvement.

further study (p. 5). Impact evaluation is often considered a

useful way to measure program outcomes. Both

34

© Journal of Community Engagement and Higher Education

Copyright © by Indiana State University. All rights reserved. ISSN 1934-5283Journal of Community Engagement and Higher Education Volume 9, Number 2

quantitative and qualitative methods can be mixed-method case study approach was consid-

used (Befani, Barnett, & Stern, 2014; Ravallion, ered most suitable. Information to meet the

2001; Rogers & Peersman, 2014; White, 2010). evaluation aims was collected from the follow-

Qualitative evaluation can provide in-depth ex- ing groups:

planations for success, better understanding of

the context, and useful information for im- Tutors (face-to-face, phone, or email inter-

provement (Bell & Aggleton, 2012; Rogers & views);

Peersman, 2014). Senior management (face-to-face inter-

Educational evaluation needs to be in- views);

dependent (Fiddy & Peeke, 1993), flexible

(Kettunen, 2008), and student-centered (Law, Students and former students (focus group

2010; Youngman, 1992), and needs to engage interviews);

communities and stakeholders (Reed, 2015). Key community stakeholders (focus group

Possible measures of the short-term effective- or individual interviews).

ness of educational programs include student

outcomes and student satisfaction (Phipps &

Merisotis, 1999); longer-term measures might Participants

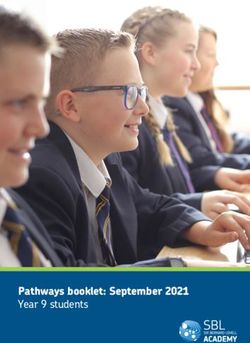

be that graduates achieve better jobs and higher The table below summarises the num-

income (Scott, 2005). ber of participants in each group.

Jennifer Greene (2013) notes that

mixed methods evaluations improve the credi-

bility of evidence through allowing for diverse Participant Groups Numbers

standpoints and voices to be heard, resulting in

richer, deeper, and better understanding of out- Staff 14

comes, contexts, and processes. Qualitative

mixed-methods can also attend to the relational

aspects of the program/s and settings and, be- Community Stakeholders 10

cause of attention to process and contexts, the

evidence is more likely to be actionable. Students 55

In Ōpōtiki, because of the broad range

of programs being taught and the way in which Students from the following programmes

these offerings had expanded over time, it was participated in focus groups:

timely to evaluate the impact that the institu-

tion’s presence and programs were having on Certificate in Maritime and Fishing Tech-

students and the community and to consider nology Level 3

how this delivery has impacted on the institu-

National Certificate in Beauty Services

tion. The aims were:

(Cosmetology) Level 3

1) To evaluate the impact of Ōpōtiki programs Certificate in Beautician and Cosmetology

on students and on the community; Level 4

2) To gather information about the suitability, National Certificate in Horticulture Level 4

value, and success of programs offered in

2015; Certificate in Preparation for Law Enforce-

ment Level 3

3) To gather feedback from students and com-

munity organizations about possible future National Certificate in Aquaculture Level 4

programs. At the time the evaluation was carried

out, the total number of students enrolled in

METHOD these programmes in Ōpōtiki was 94 (59% of

those enrolled in 2015) as the evaluation was

Because the institution was interested conducted in the second semester, and some

to learn more about the impact its programs courses had already been completed in the first

were having in Ōpōtiki in order to improve, a semester. The students who participated in the

35

© Journal of Community Engagement and Higher Education

Copyright © by Indiana State University. All rights reserved. ISSN 1934-5283Journal of Community Engagement and Higher Education Volume 9, Number 2

focus group interviews were all those students Findings

who were in class on the days on which the fo- A total of 217 students enrolled in the

cus groups were held. Participation was volun- institution’s programs in Ōpōtiki in 2015. Sev-

tary, but all students consented to participate. enty-one percent were Māori; 34% were under

Because of the nature of the focus 25 years old. Course and qualification comple-

groups, the researchers did not record the eth- tions in 2015 were high, ranging from 75% up

nicity or age of participants. However, it is like- to 100%. Course evaluations were very posi-

ly that the percentage of Māori participating in tive, with 93% of students who completed an

the focus groups was similar to the overall eth- evaluation reporting that they were satisfied

nicity of students enrolled in Ōpōtiki pro- with their course overall. The table on the next

grammes (71% Māori). It is also likely that the page shows the program completions for each

age profile was very similar to the overall co- program.

hort (35% under 25 years).

Staff interviewed included eight tutors Student feedback.

teaching on the programmes currently being Students reported that their study had

taught and six other staff who had management impacted on many aspects of their lives. Many

responsibilities for programmes taught in reported improved motivation and self-

Ōpōtiki. About half of the staff interviewed confidence, for example:

were Māori. The community stakeholder group

included participants from four organizations; We wake up in the morning and

eight of these participants were Māori. we’ve got reason to be some-

where, we belong, we’ve got a

Focus Groups and Interviews purpose, we belong somewhere,

Students were asked their views about it’s like family. There’s com-

their study, what they had liked and what the mitment.

challenges were. They were asked about their When we got here a lot of us

intentions for further study or employment on were shy, quite withdrawn and

completion of their course and what their fami- now we can’t shut up.

lies thought about their studies. Community

stakeholders were asked about their relation- Most of these ladies have joined

ships with the institution and their perceptions the gym, motivation is the key.

of the suitability, value, and success of the pro- When (the tutors) got here we

grams offered. They were also asked about the were a bit slumpy, but now you

impact they believed these programs were hav- can see how interested we are.

ing on the community or on particular groups. Others spoke about their prospects for further

Tutors were asked about their experiences, what study and employment:

kinds of community support they and the stu-

dents received, and about the success and value I want to get on to the mussel

of the programs. farm over in Coromandel, see if

Course and program completion data I can get a bit of knowledge

for 2015 and student course evaluation data there, so when this one opens

were also analysed to determine educational up I can share my knowledge

outcomes and students’ satisfaction with the with younger ones here… I

courses, supports, and services offered. want to get into aquaculture.

Participation in the evaluation was vol- My girl wants to go on the

untary and all participants were provided with boats … she wants to go to sea.

full information prior to giving written consent. I’m here for the mussel factory.

They were assured that their contributions

would be anonymous and that any personal dis- One teenage girl said:

closures would be kept confidential. The evalu- I do think the courses are a

ation was conducted by two evaluators not con- good opportunity… ’cause kids

nected to the programs being evaluated, and my age are dropping out of

was approved by the Bay of Plenty Polytechnic school, there’s not much oppor-

Research Committee. tunity around this town…

36

© Journal of Community Engagement and Higher Education

Copyright © by Indiana State University. All rights reserved. ISSN 1934-5283Journal of Community Engagement and Higher Education Volume 9, Number 2

there’s not much job opportuni- I think it all comes down to the

ties so having these courses tutor, thoughtful of us as people

actually does give teenagers my and individuals… being cultur-

age (a chance) to actually expe- ally aware was very important.

rience something new … so Culture matters when you come

these courses actually help us to into a shared space like this.

learn the things we want to do

Our tutors are the bomb! They

instead of focusing on other

teach us in different ways and

things that are not going to in-

relate to us in different things,

terest you in the future.

they’re easy to get along with

These comments show that participants be- and talk to.

lieved their study was providing them with

These participants highlight the importance of

skills and qualifications that would be useful for

having tutors who were approachable, inspiring,

future employment, and that they could see

and able to enter into their culture, in short who

these connections.

were willing to develop authentic relationships

The building of relationships with one

with them.

another and with tutors was very important for

Relationships with fellow students were

student success. Students appreciated the sup-

also important. In one class, someone reported,

port they received from their tutors, and the ef-

“this group is so tight knit, if somebody can’t

forts made to design flexible study opportuni-

make it, someone else goes and picks them up.”

ties that fit around their busy lives. One person

Some participants also reported that

said:

their relationships with others who were already

I can probably speak for every-

studying helped them decide to enroll. In the

body here that (tutor) has changed

beauty courses, more mature students mentored

our lives. We don’t want her to go,

younger ones. In the Certificate in Maritime and

we don’t want our course to finish;

Fishing Technology, the younger students were

she has inspired us all to improve

able to help older ones with using the Internet

ourselves.

to access resources.

This appreciation of tutors was echoed by oth- Beginning education locally also in-

ers: spired some students to consider continuing

Table 1. Completion Statistics for Programs Taught in the Eastern Bay of Plenty, 2015.

Percent

Number of

EFTS3 Success

students

(by EFTS)

National Certificate in Beauty Services (Cosmetology)

21.23 49 92.7 %

Level 3

Certificate in Beautician and Cosmetology Level 4 5.40 9 88.9 %

Certificate in Kiwifruit - Orchard Skills Level 3 20.39 106 100.0 %

National Certificate in Horticulture (Introductory) Level 2 2.13 14 89.1 %

National Certificate in Horticulture Level 4 4.88 10 90.3 %

Certificate in Preparation for Law Enforcement Level 3 1.73 3 75.4 %

National Certificate in Aquaculture Level 4 1.52 14 92.9 %

Certificate in Maritime and Fishing Technology Level 3 27.39 31 92.6 %

3

EFTS = Equivalent Full-Time Student

37

© Journal of Community Engagement and Higher Education

Copyright © by Indiana State University. All rights reserved. ISSN 1934-5283Journal of Community Engagement and Higher Education Volume 9, Number 2

further study elsewhere. They tasted success far more content because of the

and gained confidence in their abilities. Several life they’ve been living prior…

of the students we spoke to were planning to but they also changed very

move away to study at a higher level, now that much in themselves. Their self-

they had demonstrated that they could do it. confidence was far higher…

When summing up the success of her class, one they got more value out of cer-

student noted, “the book is ours, we just got to tain things than I would have

write it now. You’ve given us this opportunity expected.

so it’s up to us to take that on board and go fur-

Another had been impressed by the feedback

ther to better ourselves, we’ve got the tools.”

from families and community:

Tutor feedback. So the value is fantastic actual-

Tutors said that all the programs they ly. It was really huge for some

were teaching in Ōpōtiki had value for students of those girls… we even had

and community. This was because programs their men coming in saying how

had been chosen in partnership between the in- it had changed these girls’

stitution and community groups, and were de- lives… I had the police come in

signed to either provide students with skills that and say how amazing it was.

would equip them for employment that fitted They came in actually to say

with current regional development (e.g., mussel thank you to me.

farm and harbour, horticulture) or serve as a

stepping stone for further study. Comments in- The significance of these comments lies in the

cluded: evidence from family and community that stud-

ying has had a very big impact on the lives of

These programs are vital to the both the students and their wider families,

economy and local employ- broadening students’ horizons and giving them

ment. a glimpse of further possibilities for their lives.

The tutors also emphasized the value to

Ōpōtiki is oriented to the ocean

students of practically oriented programs, field

and kaimoana (seafood).

trips, and programs that offered opportunities

Creating job opportunities, al- for work experience. They noted that most of

lowing you to still live in the students had been out of education for a

Ōpōtiki and work. long time, and many had not completed high

school.

Horticulture tutors noted that local indigenous

groups were reclaiming land that had previously Community stakeholder feedback.

been leased to larger organizations, and since All of the feedback obtained from key

they were now running the orchards them- community stakeholders about the programs

selves, they needed to upskill themselves and was very positive, with this group also noting

their staff. the impact participating in study was having on

Tutors provided many examples of pos- many students who were previously disengaged

itive changes they had observed in students, from education. They noted that many had lives

which had also had an impact on their family, marked by stresses, such as poverty and vio-

and described students as role models within lence. One reported:

the community. One tutor reported: Many come from difficult back-

What I’ve seen happen in stu- grounds… We’re getting them

dents has been far more than I from crisis to being contribu-

expected to see… clearly a lot tors, and the tohu (qualification)

of my students, they’re very is a symbol of their achieve-

exposed to one type of life and ment.

haven’t had much opportunity Stakeholders anticipated employment

to get out there, so they experi- opportunities would grow in Ōpōtiki in the fu-

enced something that was ture, and wanted to see their own young people

new… they’ve been exposed to develop the skills to meet the likely increased

38

© Journal of Community Engagement and Higher Education

Copyright © by Indiana State University. All rights reserved. ISSN 1934-5283Journal of Community Engagement and Higher Education Volume 9, Number 2

demand. They made many suggestions for pro- to their community did not negatively impact

grams that could be offered in the future. The academic standards (Whiteford et al., 2013).

most often recommended programs were in the While students in Ōpōtiki did not have access to

primary industries, such as horticulture, aqua- the same kinds of resources as students study-

culture, forestry, and marine studies. Of high ing on the institution’s larger campuses, with

importance were programs that equipped people less access to library and Internet, they reported

for employment in the mussel farm and harbor having access to what they needed to be suc-

development, such as construction and engi- cessful in their studies, and their educational

neering. Thinking laterally about how the pro- outcomes, nevertheless, were well above the

posed developments would boost growth in the institutional average qualification completion

Ōpōtiki district, people also thought that pro- rate of 67% (http://archive.tec.govt.nz/). This

grams in small business management, commu- success is likely to be due to a number of fac-

nication skills, administration, and accounting tors, such as smaller class size and enthusiastic,

would be useful. Over time, Toi Ohomai Insti- well-qualified staff; availability of high-quality

tute of Technology will respond to these sug- support and mentoring; and the partnerships

gestions by expanding the programs offered in established with local Māori organizations

Ōpōtiki. (Bambrick, 2002; May, 2009). In addition,

some of the programmes were free or low cost,

Summary of findings.

allowing students to remain in their communi-

The feedback received from all partici-

ties while studying (Jamieson, 2000), with good

pant groups was overwhelmingly positive. The

prospects of future employment in their own

only negative feedback received was about the

community.

lack of Internet availability, and a couple of

In addition, all groups interviewed

complaints about noise and lack of heating in

viewed the programs as successful beyond the

some classrooms. Positive comments were re-

completion of qualifications. Students, tutors,

ceived from students about the impact of their

and community participants reported that the

studies on them and their families, their rela-

study had a positive impact on students, their

tionships with each other and with tutors and

extended families, and community. It is likely

their hopes for future study or employment.

that the peer mentoring provided by some of the

Tutors observed the positive impact study was

older students had positive effects on both the

having on their students’ lives and families,

mentors and mentees as noted by other writers

with noticeable gains on confidence and self-

(Karcher, 2009). Studying provided students

presentation. Community stakeholders were

with “soft skills,” such as self-confidence and

pleased to see so many students reengaging in

self-esteem, personal presentation, and motiva-

education, and emphasized the importance of

tion to make changes in their lives. These out-

programs that would lead to employment.

comes are similar to those reported by McMur-

chy-Pilkington (2009) in her study of Māori

Discussion

adult learners; she found that in addition to aca-

The information gathered from comple-

demic outcomes, participants increased their

tion statistics, students, tutors, and community

confidence and learned important social, em-

stakeholders demonstrates that the programs

ployment, and life skills.

offered in Ōpōtiki have proved highly success-

Students and tutors alike reported a

ful for both students and the community. Com-

family-like feel within their classrooms, one of

pletion rates were consistently high across all

the factors other writers have considered im-

programs and exceeded the institution’s bench-

portant (Hoffman et al., 2013; McMurchy-

marks.

Pilkington, 2009). The importance of Māori

In contrast to other research findings

student success in a district with a high Māori

(e.g., Bambrick, 2002; Thomas et al., 2014), our

population cannot be underestimated, especially

study found that students were not being disad-

in a district where qualification levels and aver-

vantaged by studying in a remote center. Their

age incomes are low, and unemployment is rel-

educational experience was different, but they

atively high. A report on Māori economic de-

were receiving a similar quality of education as

velopment in the Bay of Plenty (Hudson & Dia-

students studying on the institution’s urban

mond, 2014) noted the importance of education

campuses (Bambrick, 2002; Owens et al.,

and pathways into local employment for region-

2009). Improving access by bringing programs

al growth.

39

© Journal of Community Engagement and Higher Education

Copyright © by Indiana State University. All rights reserved. ISSN 1934-5283Journal of Community Engagement and Higher Education Volume 9, Number 2

Based on the feedback from community business, hospitality, and tourism. Matching

leaders and stakeholders, and from the students, programs to identified needs ensured both com-

we believe there are several things that were munity interest in the programs and support

crucial to the success of programs in Ōpōtiki: from employers. The students we spoke to,

even those who were still at high school, could

Offering programs with clear links to em- clearly see links between their studies and fu-

ployment and economic development aspi- ture employment prospects; both students and

rations; community stakeholders reported that the pro-

grams currently being offered in Ōpōtiki were

Fostering partnership relationships of trust suitable for the community. Aquaculture and

with local indigenous and community or- maritime programs were considered useful in

ganizations; preparing students for future work on the mus-

Providing programs that assisted young sel farm or in the mussel processing factory.

people to transition from high school into Horticulture courses were considered highly

tertiary education, and from their initial relevant for the growing kiwifruit industry in

programs into further study; and the Eastern Bay of Plenty in particular. The

alignment of programs to economic develop-

Focusing on re-engaging disaffected youth ment and employment outcomes, both present

who had not previously experienced suc- and future, ensured a good fit with Bay of Con-

cess in education. nections (2014a, 2014b) strategies. Students in

Linking programs to employment the horticulture programs were all employed

and economic development. prior to and during their study, and have contin-

The Ōpotiki community has a collec- ued employment in this industry after complet-

tive vision of future prosperity through econom- ing their qualifications; some have also enrolled

ic development on several fronts, mostly fo- in further study. The table on the previous page

cused on primary production (aquaculture, hor- reports outcomes for students graduating from

ticulture, and agriculture), but also on ancillary the Beauty and Maritime programs.

development that community leaders believe It is interesting to note that graduate

will lead to growth in local businesses and tour- outcomes for these programs follow different

ism. An important factor that has contributed to patterns. Students in the Beauty programs were

the success of programs offered in Ōpōtiki has all female, and the outcomes suggest that many

been choosing to offer programs that provide used these programs as a first step to further

benefit to the town’s economic development study or employment. Those not in employment

plans: programs that equip people for work on or study were at home looking after children. In

fishing boats, mussel farm and horticulture, har- the Maritime program, which was mostly male

bour development and construction, as well as students, more were able to find employment

Table 2. Outcomes for graduates of Beauty programs (L3 and L4) and the Maritime program

Beauty programs Maritime program

Enrolled in further study 36% 3%

Working in the industry in which they completed

14% 36%

qualifications

Working in other employment 21% 36%

Looking for work 13%

Not in employment or study 11% 25%

40

© Journal of Community Engagement and Higher Education

Copyright © by Indiana State University. All rights reserved. ISSN 1934-5283Journal of Community Engagement and Higher Education Volume 9, Number 2

either in the industry or elsewhere. Fewer Mari- Students’ reports of how much they

time students went on to further study. enjoyed the engagement with others in the

Through his industry contacts, the Mar- classroom and the relationships they had with

itime program tutor was able to link students their tutors clearly demonstrated the value of

directly into employment opportunities, which providing face-to-face educational opportuni-

is likely the reason so many of these graduates ties; it is unlikely that online programs would

quickly found jobs. The importance of connec- have had the same success. Indeed, the evalua-

tions with workplaces has been noted by other tion also found that at present, technology infra-

writers (Fredman, 2013; Helms Jørgensen, structure in Ōpōtiki is inadequate to fully sup-

2004). These students had all visited workplac- port online programs. The importance for stu-

es during their study, including days spent on dents, particularly Māori students, of having a

fishing vessels, which allowed them to under- place away from their home life, in a family-

stand the relevance of their learning to employ- like setting that affirmed their culture and

ment, something that is considered important where they built relationships with their tutors

(Billett, 2004; Cooper et al., 2010; Guile & and each other was essential, as other writers

Griffiths, 2001). Making the links very clear have attested (Leslie & Ehrhardt, 2013; Mayeda

during their study is likely to have helped stu- et al., 2014; McMurchy-Pilkington, 2009).

dents transition into employment (Cuervo &

Wyn, 2016). Transition pathways.

The aquaculture program was taught at

Partnership relationships. the local high school as a “Trades Academy”4

Our findings demonstrated the im- program, with a view to providing students a

portance for tertiary education providers of es- pathway into further tertiary study that would

tablishing and continuously fostering strong prepare them for working either on the mussel

relationships with community stakeholders. farm or in the mussel processing factory. Staff

Stakeholders appreciated that senior staff visit- at the school thought that offering programs

ed the town on numerous occasions and attend- that allowed senior students to begin tertiary

ed key community events. They listened to study while remaining at school may have in-

community aspirations, and decisions about fluenced some students to remain in school in-

which programs to offer were based on the re- stead of dropping out. However, evaluating pro-

quests of community stakeholders. grams over a single year meant it was not possi-

It was also vital that tutors fostered ble to know for sure how many students re-

good relationships with their students, and with mained in school because of this opportunity;

wider families and community people. Many of further research will be needed over a number

the tutors travelled to Ōpōtiki each week to of years in order to identify any possible trend

teach, but still managed to build rapport and toward improved school retention, as has been

gain acceptance within the community. Stu- noted by other researchers (Education Review

dents and community stakeholders made very Office, 2015). Our interviews with school stu-

positive comments about tutors and their will- dents recorded the enjoyment these students

ingness to build relationships. Partnership rela- gained from their studies, and their appreciation

tionships with Māori community organizations at being treated like adult students while still at

and the local high school were crucial to the school. Researchers in other countries have also

success of the programs, demonstrating again found that it is important for students to be

the value of such relationships (Cortese, 2003; treated like adults and given choices about their

Hohepa et al., 2004; Tarena, 2013; Thomas et learning (McGregor et al., 2015; Ross & Gray,

al., 2014). Also important were the relation- 2005; te Riele, 2000).

ships developed with families (Johnstone & Other writers have similarly recognised

Rutgers, 2013) and with local schools (Bidois, the importance of transition programs, particu-

2013; May, 2009; Thomas et al., 2014). larly for Māori students (e.g., Hudson & Dia-

mond, 2014; Johnstone & Rutgers, 2013). The

4

Trades academies are partnerships between secondary schools and tertiary education providers offering trades-

based, practical programs intended to meet the needs of secondary students at risk of not staying or succeeding in

education (Education Review Office, 2015).

41

© Journal of Community Engagement and Higher Education

Copyright © by Indiana State University. All rights reserved. ISSN 1934-5283Journal of Community Engagement and Higher Education Volume 9, Number 2

transition programs taught in Ōpōtiki also met 2000). Students’ reports suggested that tutors

the recommendations of other researchers were engaging them through creating trusting

through ensuring they targeted priority learners, and supportive relationships (McGregor et al.,

linked well to future employment prospects, 2015; Sanguinetti et al., 2005; te Riele, 2000).

and were designed in partnership with schools Having successfully completed their programs,

and community organizations (Education Re- many of these “second chance” students report-

view Office, 2015; Priority Learners Education- ed increased confidence about seeking employ-

al Attainment Working Group, 2012). ment, starting up their own businesses, or carry-

As well as transitioning students from ing on with further study.

school into tertiary study, the programs offered The programs offered met the aspira-

in Ōpōtiki provided a useful stepping stone into tions set out in both the Tertiary Intentions

further study for some students. Similar to what Strategy and the Māori Economic Development

other researchers have found (Bambrick, 2002; Strategy (Bay of Connections, 2014a, 2014b) of

May, 2009; McMurchy-Pilkington, 2009), re-engaging youth in education. Factors that

many students reported they were not in a posi- contributed to success in re-engaging those who

tion to move away for their studies, mostly be- had not previously experienced success in edu-

cause of family commitments. However, some cation were the choosing of programs clearly

reported that they were now intending to under- aligned to community goals, the partnership

take further study, even though it meant moving approach taken by the institution, and the rela-

away. Achieving success and gaining self- tionship-building of tutors who worked hard to

confidence assists with transition into further create a learning environment that was cultural-

study (Jefferies, 1998; May, 2009). ly appropriate for their students (Hohepa et al.,

2004; Priority Learners Educational Attainment

Re-engaging “second chance” learn- Working Group, 2012).

ers. Additional programs suggested for the

In a town where many young people future need to build on previous offerings and

leave school with no qualifications and have help prepare people for employment in the mus-

little expectation of finding employment local- sel farm, mussel processing factory, ancillary

ly, programs that encouraged them to re-engage industries such as construction, engineering,

with education were considered important by and service industries such as tourism and hos-

community stakeholders and by the students pitality. The current and planned developments

themselves. This finding confirms the value of in horticulture, forestry, and agriculture will

“second chance” education reported by other contribute to increased demand for skilled

writers internationally (e.g., Ross & Gray, workers, managers, and business owners. Pro-

2005; te Riele, 2000). Several of the programs grams offered in Ōpōtiki both now and in the

we evaluated had mostly “second chance” future should be anticipating this expected

learners enrolled, and it can be seen from the growth by offering people opportunities to gain

outcomes that these students experienced suc- skills for the future.

cess. Several reported that the school environ-

ment had not suited them well (McGregor et al., Challenges.

2015; Ross & Gray, 2005). The Maritime and Offering programs in a rural centre

Fishing Technology program attracted mostly away from the institution’s main campuses pre-

male students, many of whom had not previous- sented challenges for the institution and for tu-

ly experienced success in study. They wanted to tors. One of the biggest challenges was the lack

learn vocational job-related skills that would of Internet availability in Ōpōtiki, and therefore

lead to employment (McGregor et al., 2015; lack of access to online resources. Tutors were

Sanguinetti et al., 2005). Beauty programs were reliant on rooms and resources supplied by

seen as useful in enticing women back into edu- community stakeholder organizations that were

cation, as well as improving self-confidence not always fit for the purpose, and did not al-

and personal presentation. School students con- ways have access to the support they needed.

sidered at risk of leaving school who completed However, support for students was strong and

the aquaculture program thrived in an environ- provided locally. Although students did not

ment where they were treated like adults and have the same access to resources as on-campus

given choices about their study (McGregor et students, tutors were resourceful and found

al., 2015; Sanguinetti et al., 2005; te Riele, ways to ensure that they gained the experience

42

© Journal of Community Engagement and Higher Education

Copyright © by Indiana State University. All rights reserved. ISSN 1934-5283Journal of Community Engagement and Higher Education Volume 9, Number 2

they needed for employment. For example, field wishing to provide programs in rural communi-

trips and simulated work environments meant ties:

that students were not disadvantaged in this re-

gard. Establish relationships and/or partnerships

with community organizations to make sure

programs are suitable for that community;

CONCLUSION

Ensure that programs offered are linked to

This evaluation demonstrated the suc- local employment opportunities;

cess of providing tertiary education programs in Provide study pathways that enable young

a rural part of the Eastern Bay of Plenty, where

people to study while remaining in their

the majority of students were Māori. Our study

own communities;

found that students were not being disadvan-

taged by studying in a remote center. The suc- Meet the needs of “second chance” learn-

cess of these programs was attributed to ensur- ers; and

ing that the programs offered linked to local

economic development and employment oppor- Provide a suitable environment that meets

tunities, and that these links were explicit. Fos- the cultural needs of indigenous students.

tering relationships with local indigenous and

community organizations and responding to REFERENCES

their needs and aspirations also ensured that

programs were relevant, and that support was Alzamil, Z. A. (2014). Quality improvement of

available for students. Programs that assisted technical education in Saudi Arabia: Self-

young people to transition from high school evaluation perspective. Quality A ssurance

into tertiary education and re-engaged disaffect- in Education, 22(2), 125-144. doi:10.1108/

ed youth who had not previously experienced QAE-12-2011-0073

success in education also met important com- Atkinson, J., Salmond, C., & Crampton, P.

munity needs. (2014). NZDep2013 Index of deprivation.

A note of caution, and one mentioned Retrieved from http://www.health.govt.nz/

by several stakeholders, is that Ōpōtiki is a fair- publication/nzdep2013-index-deprivation

ly small community, with around 8,436 people Bambrick, S. (2002). The satellite/remote cam-

living in the region, and approximately half of pus: A quality experience for Australian

these in Ōpōtiki itself. There is a danger of first year students. Paper presented at the

“flooding the market” with too many courses 6th Pacific Rim First Year in Higher Educa-

and programs. Because of this, it is important tion Conference Changing Agendas “Te Ao

that Toi Ohomai Institute of Technology collab- Hurihuri” Christchurch, New Zealand.

orates with key community stakeholders when Bay of Connections. (2014a). Bay of Plenty

planning future program offerings and also tertiary intentions strategy 2014 – 2019: He

works with other tertiary education providers to mahere matauranga matua mo tatau. Re-

avoid duplications. trieved from http://

That said, it is likely that the education www.bayofconnections.com/sector-

and training needs of the Ōpōtiki region will strategies/tertiaryintentions-strategy/

expand in the future, alongside planned devel- Bay of Connections. (2014b). Maori economic

opment in primary industries and the harbour development strategy: He mauri ohooho.

development. Our institution now has a good Retrieved from http://

reputation in Ōpōtiki amongst key stakeholders www.bayofconnections.com/downloads/

and industry organizations. Because of these BOC%20MAORI%20ECONOMIC%

relationships, the organization is well placed to 20Strategy%202013.pdf

continue to offer high-quality programs to meet Befani, B., Barnett, C., & Stern, E. (2014). In-

the expressed and future needs of the region. troduction: Rethinking impact evaluation

We believe that the findings of this for development. IDS Bulletin, 45(6), 1-5.

evaluation are transferable to other situations, doi:10.1111/1759-5436.12108

and highly recommend that other educators

43

© Journal of Community Engagement and Higher Education

Copyright © by Indiana State University. All rights reserved. ISSN 1934-5283You can also read