CAUSES AND CONSEQUENCES: WHAT DETERMINES - OUR SEXUAL AND REPRODUCTIVE HEALTH? - THE EUROPEAN MAGAZINE FOR SEXUAL AND REPRODUCTIVE HEALTH

←

→

Page content transcription

If your browser does not render page correctly, please read the page content below

CAUSES AND CoNSEqUENCES: WHAT DETERMINES

oUR SExUAL AND REPRoDUCTIvE HEALTH?

THE EUROPEAN MAGAZINE FOR SEXUAL AND REPRODUCTIVE HEALTH

No.73 - 2011Contents

The European Magazine for Sexual and

Reproductive Health Editorial

By José Maria Martin-Moreno 3

Entre Nous is published by:

Division of Noncommunicable Diseases Social determinants of sexual and reproductive health:

and Health Promotion A Global Overview

Sexual and Reproductive Health By Jewel Gausman and Shawn Malarcher 4

(incl. Making Pregnancy Safer)

Social determinants of health and Millennium Development Goal

WHO Regional Office for Europe

(MDG) 5: improving maternal health

Scherfigsvej 8

An excerpt from “Progress towards Millennium Development Goals 4, 5, and 6

DK-2100 Copenhagen Ø

in the WHO European Region: 2011 Update.” 8

Denmark

Tel: (+45) 3917 17 17 The Millennium Development Goals, social determinants and sexual

Fax: (+45) 3917 1818 and reproductive health: an overview in Europe

www.euro.who.int/entrenous By Sandra Elisabeth Roelofs and Tamar Khomasuridze 12

Chief editor

Dr Gunta Lazdane UNFPA Regional technical meeting on reducing health inequalities

Editor in eastern Europe and central Asia

Dr Lisa Avery By Rita Columbia 14

Editorial assistant

Jane Persson Sexual and reproductive health in eastern Europe and central Asia:

Layout exploring vulnerable groups’ needs and access to services

Kailow Creative, Denmark. By Manuela Colombini, Susannah H. Mayhew and Bernd Rechel 16

www.kailow.dk

Sexual and reproductive health inequities among Roma

Print in the European Region: lessons learned from the

Kailow Graphic

former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia

By Sebihana Skenderovska 18

Entre Nous is funded by the United Nations

Population Fund (UNFPA), New York, with the Decreasing inequality in health – moving towards Health 2020

assistance of the World Health Organization Interview with Dr Agis D. Tsourus 20

Regional Office for Europe, Copenhagen,

Denmark. Domestic violence in Romania:

Present distribution figures stand at: 3000 The relationship between social determinants of health and abuse

English, 2000 Spanish, 2000 Portuguese, By Cornelia Rada, Suzana Turcu and Carmen A. Bucinschi 22

1000 Bulgarian and 1500 Russian.

Migrants’ health needs and public health aspects associated with

Entre Nous is produced in: the north Africa crisis

Bulgarian by the Ministry of Health in Bul- By Santino Severoni 24

garia as a part of a UNFPA-funded project;

Portuguese by the General Directorate for Contraceptive behaviour change: beyond contraceptive prescription

Health, Alameda Afonso Henriques 45, By Lisa Ferreira Vicente 26

P-1056 Lisbon, Portugal;

Displaced populations in Georgia:

Russian by the WHO Regional Office for

UNFPA supported sexual and reproductive health programmes

Europe Rigas, Komercfirma S & G;

By Tamar Khomasuridze, Lela Bakradze and Natalia Zakareishvili 28

Spanish by the Instituto de la Mujer, Minis-

terio de Trabajo y Asuntos Sociales, Almagro Resources

36, ES-28010 Madrid, Spain. By Lisa Avery 30

The Portuguese and Spanish issues are

distributed directly through UNFPA repre

sentatives and WHO regional offices to

Portuguese and Spanish speaking countries

in Africa and South America.

Material from Entre Nous may be freely trans-

lated into any national language and reprint-

ed in journals, magazines and newspapers or

2 placed on the web provided due acknowl- The Entre Nous Editorial Advisory Board

edgement is made to Entre Nous, UNFPA and

the WHO Regional Office for Europe. Dr Assia Brandrup- Dr Evert Ketting Prof Ruta Nadisauskiene

Lukanow Senior Research Fellow, Head, Department of Obstetrics

Articles appearing in Entre Nous do not Senior Adviser, Radboud University and Gynaecology

necessarily reflect the views of UNFPA Danish Center for Health Nijmegen Department Lithuanian University of Health

or WHO. Please address enquiries to Research and Development of Public Health, Sciences,

the authors of the signed articles. Faculty of Life Sciences Netherlands Kaunas, Lithuania

For information on WHO-supported activi-

ties and WHO documents, please contact Ms Vicky Claeys Dr Manjula Lusti- Dr Rita Columbia

Dr Gunta Lazdane, Division of Noncom Regional Director, Narasimhan Reproductive Health Advisor

municable Diseases and Health Promotion, International Planned Scientist, Director’s Office UNFPA Regional Office for

Sexual and Reproductive Health at the Parenthood Federation HIV and Sexual and Eastern Europe and Central Asia

address above. European Network Reproductive Health

Please order WHO publications directly from Department of

the WHO sales agent in each country or from Dr Mihai Horga Reproductive Health

Marketing and Dissemination, WHO, Senior Advisor, and Research

CH-1211, Geneva 27, Switzerland East European Institute for WHO headquarters,

Reproductive Health, Geneva, Switzerland

ISSN: 1014-8485 Romania,,

Editorial José

Maria

Martin-

Moreno

As the countdown to the formal deadline to attend antenatal care or to obtain the However, with political will, consider-

for the Millennium Development Goals appropriate information about pregnancy able progress can be made. This issue

in 2015 grows nearer, it is apparent that services. If she happens to reside in a of Entre Nous highlights what progress

gross inequalities in health, including country where public policies penalize and challenges have been made in the

sexual and reproductive health (SRH), are adolescent pregnancy or prevent youth European Region in tackling this very

present both across and within regions friendly health services, she becomes even important issue. It is our hope that long

and countries, globally and in Europe. more marginalized, with limited ability to after you have completed reading the

While it is true that the majority of Mem- access SRH services. All of these aspects articles you will continue to ask yourself

ber States in the WHO European Region combine to greatly reduce both her and “What determines our SRH?” It is only in

have much to celebrate when it comes to her unborn child’s opportunity for posi- continually asking this question that we

progress in improving SRH and increas- tive health outcomes. will be able to address the root causes and

ing access to SRH services, it is also true However, SRH and other health decrease SRH inequities. From our side,

that even in the most affluent countries inequities are not inevitable – quite the the WHO Regional Office for Europe will

of the Region, social injustice exists, with contrary. Health inequities are a problem continue defining goals and targets of

select groups at greater risk of poor SRH for all countries and require actions that the New European Health Policy, Health

outcomes and limited access to SRH move beyond treating adverse health and 2020, gathering best practices and assist-

services. This social gradient holds true SRH outcomes to tackle the underlying ing countries in promoting equity and

across all health fields and in all socie- causes that contribute to them. Across championing the principles of human

ties; the most disadvantaged experience Europe, more and more countries are in- rights.

poorer health and shorter life expectancy. troducing policies that address the social

In order to address this social injustice, determinants of health, but translating

there is an urgent need to move beyond these policies into action remains a chal- Dr José Maria Martin-Moreno,

examining the different statistics that lenge. Doing this successfully requires Director,

highlight these disparities (e.g. maternal that action across all five of the key build- Programme Management,

mortality, neonatal mortality, contracep- ing blocks of the “social determinants

WHO Regional Office for Europe

tive prevalence rate, abortion rate, adoles- approach” recommended by the WHO

cent pregnancy rate, number of antenatal Commission on Social Determinants of

care visits, HIV and sexually transmitted Health is taken. This entails involvement

infections incidence and prevalence) and of multiple sectors at all levels (inter-

ask, “What determines our SRH?” national bodies, governments and civil

In fact, the answer is quite complex. society), with concerted action across the

While genetic susceptibility plays a small following five themes:

role, it is our environment and the condi-

tions in which we live and work that have 1. Governance to tackle the root causes

the greatest impact and effect on our of health inequities: implementing

health. Increasingly, social factors such as action on social determinants of

geographic location, education, employ- health;

ment, economic status, religion, culture, 2. Promoting participation: community

social exclusion, gender and ethnicity are leadership for action on social deter- 3

being identified as the underlying causes minants;

of these health disparities. Individually 3. The role of the health sector, includ-

or in combination, these factors under- ing public health programmes, in

mine more than just SRH health, but reducing health inequities;

also development, sustainability and 4. Global action on social determinants:

overall community wellbeing. Public aligning priorites and stakeholders;

policies that fail to act on these adverse and

social conditions help contribute to 5. Monitoring progress: measurement

unfair and avoidable inequities in SRH and analysis to inform policies and

between groups. For example, a pregnant, build accountability on social deter-

unmarried adolescent girl will likely face minants.

social stigma because of her pregnancy.

Although she attends school, she may Addressing the social determinants

not have the financial means to be able of health can appear overwhelming.

No.73 - 2011Social Determinants of Sexual

and Reproductive Health:

A Global Overview

T

he World Health Assembly and largest cancer-related cause of life human papillomavirus can lead to the

the World Health Organization years lost in these countries (5). development of genital cancers, while

(WHO) affirm that “sexual and STIs are the main preventable cause

reproductive health is fundamental to Observed imbalances in access to re- of infertility (8). Infertility is often

individuals, couples and families, and sources result in a cycle of disadvantage blamed on the woman, and women

the social and economic development of at the individual level. Evidence demon- may suffer similar negative conse-

communities and nations” (1). strates that less advantaged population quences including humiliation and

In many countries, however, improve- groups are more vulnerable to exposure, physical abuse.

ments in sexual and reproductive health less likely to access health care, and have • Women in developing countries are

(SRH) related outcomes have often been worse health outcomes. Migrant popula- more likely to suffer from chronic dis-

slow despite significant investment. tion, adolescents, and ethnic minorities ability resulting from unsafe abortion

Social and economic inequalities have are often difficult to reach through the or complicated pregnancies. When a

come to the attention of the interna- existing health infrastructure, and face a woman develops an obstetric fistula,

tional community as an important factor variety of legal, social and cultural barri- she not only faces the physical suffer-

driving many health inequalities. Social, ers to accessing SRH services. For many ing associated with the condition, but

demographic, economic and geographic vulnerable groups, issues surrounding may also face divorce, social exclu-

differences within a population are im- language, cultural attitudes, perceptions sion, malnutrition, and increased

portant underlying factors that influence of health service availability, and provider poverty.

access to high quality health care and thus attitudes make accessing services, if they • Environmental factors play an im-

health status. are available, a challenge (6). portant role in women’s susceptibility

At the global level, the world’s poorest Women in many developing countries to rape and gender based violence

countries often struggle with resource also face increased economic vulnerability (GBV). For example, women are often

constraints that limit investment in the which combines with low levels of educa- placed in vulnerable situations while

health infrastructure. As a result, develop- tion and a reduced social status – thereby waiting for transportation at night,

ing countries bear the highest burden of resulting in them having little autonomy collecting water, or using latrines.

disease, including maternal mortality, to make decisions on how or when to seek • Where early marriage and/or

reproductive cancers, and sexually trans- medical care or family planning services. childbearing is prevalent, girls who

mitted infections (STIs) while also facing Underutilization of health services are exposed have less education and

high population growth. by women has been well documented schooling opportunities, less house-

Globally, the magnitude of poverty’s with factors related to underutilization hold and economic power than older

impact on SRH is astounding: of health services grouped into three married women, less exposure to

• Of the 20 million unsafe abortions categories (7). The first includes service modern media and social networks,

that occur each year, 19 million are factors such as affordability, accessibil- are at great risk of GBV, and face

estimated to take place in developing ity, and adequacy of the health system to greater health risks, such as exposure

countries. The consequences of un- meet women’s needs. The second group to HIV and/or having their first birth

safe abortion are also highly variable. addresses user constraints, such as social at a young age (9).

Women living in Sub-Saharan Africa mobility, lack of financial resources, • GBV is rooted in gender inequality. A

are 75 times more likely to die than a and greater demand’s on women’s time, WHO multi-country study on GBV

4 woman living in a developed country and information asymmetries of health found that the prevalence of women

(2). information between women and men. who have suffered physical violence

• The annual incidence of STIs ranged The third group identifies institutional from a male partner ranged from

from 109.7 million new cases in the factors, including men’s decision-making 13% in Japan to 61% in provincial

Africa region to 25.6 in the Eastern power and control over health budgets Peru. In terms of sexual violence,

Mediterranean region. As a com- and facilities, local perceptions of illness, Japan also had the lowest level at 6%,

parison, incidence in the European and stigmatization and discrimination in and Ethiopia had the highest at 59%

Region was estimated at 44.6 (3). health settings. (10).

• Approximately 80% of cervical cancer The following examples illustrate the

cases occur in low-income countries breadth of gender’s influence on SRH, Education is an important mediating

and this is expected to increase to but also highlight how multiple social factor with regard to women’s SRH

90% by 2020 (4). Cervical cancer is determinants often compound to have an outcomes. Increased women’s education

the second most common cancer even greater impact. is not only linked to fertility decline, but

among women living in the devel- • STIs are often more easily transmitted also facilitates the diffusion of ideas re-

oping world, and is also the single to women from men. Infection with garding childbearing, contraception, andJewel Shawn

Gausman Malarcher

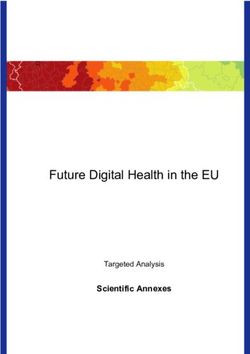

Figure 1. Total Fertility Rate by Highest Educational Level, Selected Countries. include armed conflict and legal systems

Background Characteristics that fail to prosecute sexual violence or

Total fertility rate and proportion of women pregnant Highest educational level

Fertility rates: Total fertility rate No education

protect women’s civil rights (13). A recent

8

Primary analysis in 20 countries with the highest

Secondary or higher

prevalence of child marriage found four

7 factors were strongly associated: educa-

6

tion of girls, age gap between partners,

geographical region and household

5 wealth (13).

For women who are sexually active,

4

modern contraception is the best protec-

3 tion from an unintended pregnancy.

In most developing countries, wealthy

2

individuals are more likely to adopt

1

modern contraception than the poor.

This relationship is illustrated in Figure 2

0 with data from selected developing coun-

Armenia Bangladesh Haiti India Kenya Mali Nigeria Ukraine

DHS 2005 DHS 2007 DHS 2005-06 DHS 2005-06 DHS 2008-09 DHS 2006 DHS 2008 DHS 2007 tries. In all the countries shown, modern

ICF Macro, 2011. MEASURE DHS STATcompiler - http://www.statcompiler.com - October 13 2011. contraceptive use is significantly higher

among women in the highest wealth

quintile versus those in the lowest.

the social status and value placed upon without full and informed consent. Be- Health services are responsible for

women. As shown in Figure 1, fertility yond the potential consequences of STIs providing women with essential informa-

tends to decrease as household educa- and unwanted pregnancy, evidence sug- tion to make an informed choice and suf-

tional level increases. For example, girls gests that sexual coercion negatively af- ficient instruction for correct method use.

with secondary education in Bangladesh, fects victims’ general mental and physical Yet women often receive differential treat-

were nine times less likely to be married well-being. Sexual violence is also asso ment from providers. Studies from Ghana

by their 18th birthday (11). While wealth ciated with risky behaviours such as early and Nepal using “simulated patients”

and educational status are closely related, sexual debut and multiple partners (11, indicate that lower-class, uneducated and

some analysis indicates that education 13). Key factors associated with higher younger clients receive poorer treatment

may moderate the effect of wealth on levels of sexual violence and coercion (14,15). Clients of lower socioeconomic

contraceptive use (7).

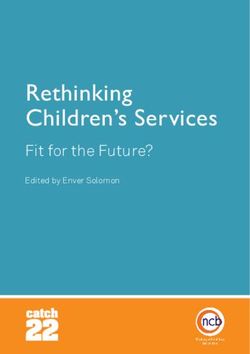

A Closer Look at the Social Figure 2. Use of a Modern Method of Family Planning Comparing the Lowest

Determinants of Unintended and Highest Wealth Quintiles, Selected Countries.

Pregnancy Current use of contraception among currently married women

Background Characteristics

Household wealth index

Worldwide, 40% of all pregnancies are Contraceptive method: Any modern method Lowest

Highest

60

unintended (12). The burden of unin-

tended pregnancy disproportionately 5

affects the poor, in almost all countries. 50

Higher rates of unintended pregnancy

have also been observed among young 40

people, the uneducated, ethnic minorities

and migrants compared to more advan- 30

taged groups. Vulnerability to unintended

pregnancy is strongly influenced by access 20

to and use of effective contraception and

by exposure to unwanted sex through 10

child marriage and sexual violence.

Women are particularly susceptible to 0

unwanted sexual activity. Sexual violence Armenia Bangladesh Haiti India Kenya Mali Nigeria Ukraine

DHS 2005 DHS 2007 DHS 2005-06 DHS 2005-06 DHS 2008-09 DHS 2006 DHS 2008 DHS 2007

and child marriage are two common ways

ICF Macro, 2011. MEASURE DHS STATcompiler - http://www.statcompiler.com - October 13 2011.

women are exposed to sexual activity

No.73 - 2011Social Determinants of Sexual

and Reproductive Health:

A Global Overview (continued)

status and adolescents are especially sus- A number of studies have documented determinants of health include factors

ceptible to restrictive provider practices, higher complication rates and mortality that may directly influence biological

as they have fewer options for where to resulting from unsafe abortion among exposure or susceptibility, such as living

access services (16). women of low socioeconomic status (22). conditions and working conditions, as

The low status of women in many Women from more affluent households well as behavioral, biological, and psycho-

countries restricts their ability to make are more likely to obtain an induced social factors. Health inequities observed

decisions within the household. One way abortion from a physician or nurse, while in a population are driven by a complex

Demographic and Health Surveys capture poor women living in rural areas are relationship between social determinants,

this dynamic is by asking women if they more likely to use a traditional practi- and are mutually reinforced through

are able to decide for themselves to seek tioner or self-induce an abortion. multiple feedback channels.

health care. In the 30 countries where Unintended childbearing detrimentally While the challenge is significant,

data were available, an average of only affects women and children. Women who progress can be made in SRH with

37% of women report they are able to have an unintended pregnancy are more increased attention to the social deter-

seek their own care. In 26 of 30 countries, likely to delay antenatal care or have fewer minants. There are a growing number of

a smaller proportion of women in the visits and experience maternal anxiety, programmes that have been successful

poorest households were able to seek care. depression and abuse (23). Unintended at designing interventions that address

The rich–poor gap ranges from less than children are more likely to experience social determinants and contribute to

1 percentage point in Bangladesh (2004) symptoms of illness, less likely to receive improved SRH. Programmes that have

to 32 percentage points in Peru (2000) treatment or preventive care such as vac- been successful have taken a targeted

(17). cinations, less likely to be breastfed and approach such as fostering community

Women with an unintended pregnancy more likely to have lower nutritional sta- participation, encouraging governments

are faced with a difficult decision, one tus, have fewer educational and develop- to support more equitable policies, and

of which may be abortion. Deciding ment opportunities and are at increased improving data collection to better

whether to terminate an unintended risk of infant mortality (23-25). understand health disparities. In order

pregnancy is influenced by many factors, Improving pregnancy outcomes will to meet the objectives set forth in the

including the availability and accessibility require interventions specifically designed Millennium Development Goals, greater

of induced abortion services, the social to achieve equity in the availability of all attention must be paid to inequities and

acceptability of childbearing and induced related health services, especially targeting the social and economic structures that

abortion, and support from social struc- the poor and disadvantaged for access to contribute to them.

tures. The decision made will have social, contraceptive and skilled birth attendant

financial and health consequences that are services. Such efforts will be most effec

not equally experienced among women. tive when combined with addressing Jewel Gausman, MHS, CPH,

“Unsafe abortion” is defined as a pro upstream determinants, such as improv- Technical Advisor

cedure for terminating pregnancy carried ing education for women and the effective Research, Technology and

out by attendants without appropriate functioning of the health sector and of Utilization Division

skills, or in an environment that does government services in general.

Office of Population and

Reproductive Health

not meet minimum standards for the

USAID

procedure, or both (18). Unsafe abortion What can be done?

jgausman@usaid.gov

6 is a major cause of maternal mortal- The varying levels of inequality present

ity, accounting for an estimated 13% of in a population have an important Shawn Malarcher, MPH,

maternal deaths worldwide (2). In 2005, impact on SRH outcomes. Differences Senior Technical Advisor,

an estimated 5 million women were hos- in control over and access to resources Research, Technology and

pitalized for treatment of complications determine both physical and financial Utilization Division,

from unsafe abortion (19). The highest access to health services. Power dyna Office of Population and

estimated rate of unsafe abortion is in mics also influence quality of clinical Reproductive Health,

Latin America and the Caribbean, where care received by a client. Additionally, USAID,

there are 33 unsafe abortions per 100 live individual health-related behavior is often

smalarcher@usaid.gov

births, followed by Africa (17 per 100 live influenced by norms surrounding social

births) and Asia (13 per 100 live births) position, ethnicity, and gender. At the

(20). Rates of unsafe abortion are highest structural level, the socioeconomic and

among young women, with almost 60% political environments interact with an

of unsafe abortions in Africa occur- individual’s position - social class, gender,

ring among women under age 25 (21). ethnicity, and income. The intermediaryReferences Medicine National Academies Press, matter? International Bank for Re-

2005. construction and Development and

1. Reproductive Health Strategy to acce 12. Blas, E, Kurup AS. Equity, social World Bank (Washington, DC), 2005.

lerate progress towards the attainment determinants and public health pro 24. Jensen ER, Ahlburg A. Impact of un-

of international development goals and grammes. Geneva: WHO, 2008. wantedness and family size on child

targets. Geneva: WHO, 2004. 13. Bott S. Sexual violence and coercion: health and preventive and curative

2. Unsafe Abortion: global and regional implications for sexual and reproduc- care in developing countries. Policy

estimates of the incidence of unsafe tive health. In: Malarcher S, editor. Matters No. 4. Policy Project, 2000.

abortion and associated mortality in Social determinants of sexual and 25. Wellings K et al. Sexual and repro-

2003. Geneva: WHO, 2007. reproductive health: informing pro ductive health – sexual behaviour in

3. Prevalence and incidence of s elected grammes and future research. Geneva: context: a global perspective. Lancet,

sexually transmitted infections, WHO, 2010. 2006, 368(9548):1706–1728.

Chlamydia trachomatis, Neisseria 14. Huntington D, Lettenmaier C,

gonorrhoeae, syphilis and Trichomonas Obeng-Quaidoo I. User’s perspective

vaginalis: methods and results used of counselling training in Ghana: the

by WHO to generate 2005 estimates. “mystery client” trial. Stud Fam Plann,

Geneva: WHO, 2011. 1990, 21(3):171–177.

4.. Parkin DM, Bray F, Chapter 2: The 15. Schuler SR et al. Barriers to effective

burden of HPV-related cancers. family planning in Nepal. Stud Fam

Vaccine. 2002 Aug; 24 (Supplement Plann, 1985, 16(5):260–270.

3): S11-S25. 16. Tavrow P. How do provider atti-

5. Cancer of the Cervix. WHO. http:// tudes and practices affect sexual and

www.who.int/reproductivehealth/ reproductive health? In: Malarcher S,

topics/cancers/en/. Accessed: October, ed. Social determinants of sexual and

6, 2011. reproductive health: informing pro

6. Female Migrants: Bridging the Gaps grammes and future research. Geneva:

through the Life Cycle. New York: WHO, 2010.

2006. 17. Gwatkins DK et al. Socio-economic

7. Buvini´c M, Médici A, Fernández E et differences in health, nutrition, and

al. Chapter 10: Gender Differentials population within developing coun

in health. In: Jamison DT, Breman JG, tries. Washington, DC: World Bank,

Measham AR et al, editors. Disease 2007.

control priorities in developing 18. Grimes DA et al. Sexual and repro-

countries, 2nd edn. Oxford University ductive health – unsafe abortion: the

Press (New York), 2006. preventable pandemic. Lancet, 2006,

8. Fact Sheet Number 110: Sexually 368(9550):1908–1919.

Transmitted Infections. WHO. 19. Singh S. Hospital admissions resulting

http://www.who.int/mediacentre/ from unsafe abortion: estimates from

factsheets/fs110/en/index.html 13 developing countries. Lancet, 2006, 7

9. Williams LB. Determinants of un 368(9550):1887–1892.

intended childbearing among ever- 20. Sedgh G et al. Induced abortion:

married women in the United States estimated rates and trends worldwide.

1973–1988. Fam Plann Perspect. 1991; Lancet, 2007, 370(9595):1338–1345.

23(5):212–218. 21. Shah I, Ahman E. Age patterns of un-

10. Garcia-Moreno C, Jansen HA, safe abortion in developing country

Ellsberg M et al. WHO Multi-country regions. RHM, 2004, 12(Suppl. 24):

study on women’s health and dome 9–17.

stic violence against women. Geneva: 22. Korejo R, Noorani KJ, Bhutta S.

WHO, 2005. Sociocultural determinants of in-

11. Growing up global: the changing duced abortion. J Coll Physicians Surg

transitions to adulthood in developing Pak, 2003, 13(5): 260–262.

countries. Washington, DC: National 23. Greene ME, Merrick T. Poverty

Research Council and Institute of reduction: does reproductive health

No.73 - 2011Social determinants of health and

Millennium Development Goal (MDG) 5:

improving maternal health

The following is an excerpt • Delay in receiving adequate care when the Region, the percentage of births as-

a facility is reached, for reasons such sisted by skilled health personnel between

from the report “Progress as, but not limited to, shortages of 2000 and 2010 was 98%, compared to

towards Millennium Devel- qualified staff or because electricity, 66% globally (5).

water or medical supplies are not Despite most countries in the Region

opment Goals 4, 5, and 6 in available (2). having almost all births attended by

the WHO European Region: skilled health personnel, there is evi-

Delays will be characterized differently dence of inequities within countries and

2011 Update.” depending on the country context and concerns about quality of the services

where a woman or adolescent girl finds provided. Available data indicate that

MDG 5 aims to improve maternal and herself within that context (i.e. her socio- socially disadvantaged groups (including

reproductive health. Its targets are: economic position, geographic location, populations with lower socioeconomic

A) to reduce by 75%, between 1990 and being of an ethnic minority group or status, ethnic minority groups and

2015, the maternal mortality ratio; irregular migrant experiencing social socially excluded migrants) and rural

B) to achieve, by 2015, universal access to exclusion). populations have poorer access (5-7).

reproductive health. Due to these social determinants, These inequities in the proportion of

inequities in MM between countries are births attended by skilled health person-

Globally, progress towards MDG 5 is stark in the European Region. Accord- nel reflect global trends. For instance,

insufficient. In 2008, there were approxi- ing to estimates from 2008 the country according to the report Progress for

mately 358 000 maternal deaths world- with the highest estimated MMR was children: Achieving the MDGs with Equity,

wide, representing only a 34% decline Kyrgyzstan (with an estimated ratio of in all regions worldwide women from

compared to 1990 (1). Maternal mortality 81) and the lowest estimated ratio was in the richest 20% of households are more

diminished by 2.3 % per year globally Greece (with an estimated ratio of 2) (1). likely than those from the poorest 20%

between 1990 and 2008, which is far short Romania had the fastest rate of decline, of households to deliver their babies with

of the 5.5% annual reduction necessary to with an 84% change in MMR between the assistance of skilled health personnel

achieve target A (1). 1990 and 2008 (1). (8).

In the European Region, the estimated Inequities in MM also persist within

average maternal mortality ratio (MMR) countries. Rural populations tend to have Contraceptive prevalence rate (CPR)

decreased from 44 deaths per 100 000 live higher MM than their urban counter- and the unmet need for family

births to 21 between 1990 and 2008 (1). parts. Ratios and risk vary widely by planning

This represents only a 52% decline when ethnicity, education and wealth status, An estimated one in three maternal

compared to 1990. The annual reduction and remote areas bear a disproportionate deaths globally could be prevented if

of 4.1% is also below the 5.5% needed to burden of deaths. Within urban areas, the women who desired contraception could

reach the target (1). risk of MM and morbidity can also differ have access to it (9). Hence, CPR and

Maternal mortality (MM) is influenced significantly between women living in the unmet need for family planning are

by interlinked social determinants that wealthy and deprived neighborhoods (3). two of the indicators used to monitor

prevent pregnant women from accessing In western Europe, where MM is gener- progress towards MDG 5 target B, which

the health services they need and are ally low, there is evidence of significantly is to achieve by 2015 “universal access to

8 entitled to as a basic human right. These higher risks for migrant and refugee reproductive health”.

determinants, of which the health system populations (4). Gender inequities, ad- Contraceptive prevalence is the per-

is one, collude to result in the “three de- dressed by MDG 3, undermine progress centage of women who are currently us-

lays”, which—when considering maternal to address MM and morbidity. ing, or whose sexual partner is currently

mortality globally—are understood to using, at least one method of contracep-

encompass: Proportion of births attended by tion, regardless of the method used. It is

• Delay in seeking appropriate medical skilled health professionals usually reported for married or in-union

help for an obstetric emergency for One of the indicators for monitoring women aged 15 to 49. The CPR for the

reasons of cost, lack of recognition of progress towards MDG 5 target A is the European Region was 70.7% for the

an emergency, poor education, lack of proportion of births attended by skilled 2000-2010 period (5). Evidence suggests

access to information, administrative health personnel. In the European Region that contraceptive prevalence (using any

barriers and gender inequality; as a whole, overall percentages of births modern method) has generally increased

• Delay in reaching an appropriate attended by skilled health personnel are across the European Region since 1990

facility for reasons of distance, infra- generally high when compared to coun- (10).

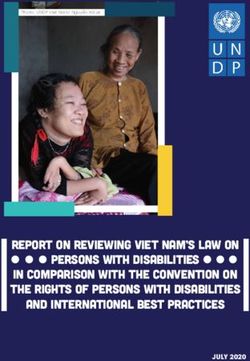

structure and transport; and tries in other regions of the world (5). In Women with unmet need for familyTable 1. ANC coverage (%) in select European Member States, by place of cations due to unsafe abortion and 50%

residence, wealth quintile and education level of mother (20). less likely to receive medical treatment,

compared to women in an urban area

ANC coverage

with a high income (16). Lack of quality

Place of Wealth Educational equipment, facilities and care may en-

Country Year

residence uintile

q level of mother

hance the risk of post-abortion complica-

Rural Urban Lowest Highest Lowest Highest tions. Stigma and psychosocial considera-

tions (including those influenced by age

Albania 2008-2009 96.2 99.1 93.3 99.3 96.9 99.4

and cultural beliefs), as well as irregular

Azerbaijan 2006 63.3 89.7 53.2 95.3 63.8 93.5 migrant status, can also be risk factors for

Turkey 2008 84.2 94.7 76.1 98.6 78.3 99.3 unsafe abortion.

Ukraine 2007 98.1 98.7 96.7 98.9 97.8 99.1 Adolescent birth rate

The adolescent birth rate, defined as the

annual number of births given by women

planning are those who are fecund and this is largely due to poor family planning aged 15–19 years per 1000 women in

sexually active but are not using any information in migrants’ home countries the age group, is an indicator for MDG

method of contraception, and report not and inadequate outreach services within 5 target B. Pregnant women under 20

wanting any more children or wanting the health services of the destination years of age face a considerable burden

to delay the birth of their next child. An country (4, 13). of pregnancy-related death and com-

average of 9.7% of women (of reproduc- Low CPR and the unmet need for plications. When compared to women

tive age who were married or in a union) family planning can contribute to higher aged 20–29 years, the risk of dying from

had an unmet need for family planning rates of abortion. Although records in pregnancy-related complications is twice

in the European Region during the 2000- many countries are not comprehensive, as high for girls/women aged 15–19 years

2009 period (5). evidence suggests that eastern Europe and and five times higher for girls aged 10–14

As with other MDG 5 indicators, central Asia has one of the highest abor- (17). Many health problems are particu-

differences can be seen across the social tion rates in the world (14). Cultural con- larly associated with negative outcomes

gradient and by location; that is, women siderations in some population groups, of pregnancy during adolescence. These

with higher incomes, education levels, including reliance on traditional methods include anaemia, sexually transmitted

and urban rather than rural residence of birth control such as withdrawal, can infections, postpartum haemorrhage and

tend to have higher use of contraceptives contribute to higher rates of abortion. mental disorders such as depression (15).

and lower unmet need for family plan- The average induced abortion rate in Taken as a whole, the European Region

ning. An example of urban versus rural countries of western Europe is low, but had an average adolescent birth rate of 24

differences comes from Turkey, where in there is evidence that requests for abor- for the 2000-2008 period (5). According

urban areas the percentage of women us- tion are higher among women with low to the latest data available, San Marino

ing a method of family planning is higher socioeconomic status, particularly if they has the lowest adolescent birth rate (1 per

(74%) than that of women residing in also have migrant status (13). 1000) and Turkey (56 per 1000) has the

rural areas (69%) (11). In some countries of the European highest. Adolescent birth rates have de-

Multidimensional social exclusion Region, abortion still causes more than creased in countries across the European 9

processes—such as those affecting ethnic 20% of all cases of maternal mortality Region (5). In the Caucuses and central

minorities and migrants—can also con- (15). In most of the Member States of the Asia, the adolescent birth rate declined

tribute to lower CPR. There is evidence European Region law permits abortion from 45 in 1990 to 29 in 2008 (18).

that the more pronounced the social to save a women’s life and in more than Adolescent fertility is influenced by a

exclusion (i.e. crossing social, political, half of the countries abortions on request range of social and cultural factors. These

economic and cultural domains), the are permitted. Despite this, it is estimated include but are not limited to gender

lower the prevalence. For instance, in Bul- that half a million unsafe abortions were inequities, low education levels, house-

garia, 65% of richer and more educated performed in 2008 in the European Re- hold poverty and lack of job prospects,

Roma women use any family planning gion, causing 7% of maternal deaths (15). stigmatization about seeking services, and

method, compared to 31% among all Exposure to unsafe abortion is socially early marriage (13). These factors com-

interviewed Roma women (12). Several determined and linked to weak health pound, resulting in more socially disad-

studies suggest that migrants tend to un- systems. Globally, a woman with low vantaged adolescents having less access to

deruse contraceptive methods compared income residing in a rural area is three needed services and less awareness about

to non-migrant populations in Europe; times more likely to suffer from compli- sexual and reproductive health (SRH)

No.73 - 2011Social determinants of health and

Millennium Development Goal (MDG) 5:

improving maternal health (continued)

and rights. Adolescents living in poverty among those in the highest education and perinatal components of basic

are particularly vulnerable. Evidence from level to only 63.8% among women in the benefit packages. Secure sufficient in-

developing countries globally suggests lowest education level. Almost all women vestments for SRH through increased

that an adolescent from a household in (95.3%) of women in the highest wealth awareness among decision-makers of

the poorest quintile is 1.7 to 4 times more quintile receive ANC, compared to only the contribution of health, includ-

likely to give birth than an adolescent 53.2% of women in households in the ing SRH, to the social and economic

from the wealthiest quintile (13). lowest wealth quintile (20). prosperity of countries.

Social and cultural factors play an Other aspects of social exclusion also • Ameliorate data collection and moni-

important role in shaping young people’s influence ANC coverage rates. Inadequate toring and evaluation systems, with

sexual behaviour. Factors such as gender social protection, at times linked to lack mechanisms in place to ensure the ef-

stereotypes, social expectation with re- of necessary documentation, is one of fective use of data on maternal health,

gards to reputations, and the existence of these. Lack of financial coverage for basic FP, SRH behaviour and the needs of

penalties and rewards for sex from society health services contributes to higher vulnerable populations. National in-

are strong determinants of behaviour. maternal mortality ratios among Roma formation systems should account for

Stereotypes can lead to refraining from women, especially when family planning the health status and needs of ado-

planned or rational behaviours in sex and antenatal care services are not cov- lescents and young people (including

practice (i.e. using a condom) and can ered. Reports from the former Yugoslav pregnant adolescents and, linked to

give limited space for young girls to adopt Republic of Macedonia show that Roma MDG 6, the numbers of adolescents

a proactive attitude in negotiating sex mothers often lack health insurance and and young people living with HIV).

practices within a societal paradigm of cannot afford the co-payment and infor- • Ensure quality of SRH services for

femininity and masculinity (19). mal costs linked to regular ANC, delivery all populations. Control for quality

and postnatal care (21). in the RMNCH continuum of care,

Antenatal care coverage Migrant women can also face chal- including for referrals and follow-

Antenatal care (ANC) is an indicator for lenges in access to ANC (13). Even when up allowing for effective coverage.

MDG 5 target B. A minimum of four socioeconomic and educational back- Increase attention to the production

ANC visits is recommended for opti- ground is taken into account, migrant and continuous capacity-building of

mal benefits. Globally, although 80% of women seem to be less likely to seek and/ professionals with the right skills mix

pregnant women received ANC at least or receive adequate ANC and have good and ensure their equitable availability

once during the 2000–2010 period, only pregnancy outcomes. This is especially for all population groups.

53% received the minimum of four ANC the case when the legal status of a migrant • Ensure access to and availability of

visits (5). in a country is unclear, and when women essential medicines and commodities

For the European Region as a whole, perceive local policies and social attitudes for SRH. Provide adequate well-

an average of 97% of women received towards them as negative. maintained equipment at all levels of

ANC from skilled health personnel at maternal/perinatal and SRH care.

least once during pregnancy during the Policy considerations • Create a demand for services through

2000-2010 period (5). In only Azerbai- In the European Region, actions where appropriate communication for

jan and Tajikistan did fewer than 90% particular attention will be required behavioural change. Communication

of women have at least one visit during to accelerate progress towards MDG 5 should be gender-, age-, literacy-level,

10 pregnancy, with coverage being 77% and include: culturally and contextually appropri-

89% respectively (5). Many countries • Increase government political and ate (reflecting thorough knowledge

do not have comprehensive data on the financial commitment for SRH and of the target population’s evolving

minimum of 4 visits. However, available rights. Ensure an enabling legal needs), and address men and tradi-

records points to inequities. and policy framework to overcome tional leaders. Due attention is also

In many countries globally, women access barriers, ensure quality, required to providers’ practices and

from the poorest households are less and strengthenthe Reproductive, attitudes, including towards adoles-

likely to receive ANC than women from maternal, neonatal and child health cents and socially excluded popula-

the wealthiest households (5). While (RMNCH) continuum of care. Facili- tions, that may obstruct patients’

varying considerably by country, in the tate that health reforms are designed access to services.

European Region differences in ANC to expand delivery of SRH services, • Establish multi-sectoral linkages and

coverage can be seen by place of resi- including through strengthened fam- integrate actions to address gen-

dence, wealth quintile and education level ily planning (FP) and service integra- der inequalities and other social

of mother (see Table 1). For instance, in tion in primary health care. determinants of SRH into policies,

Azerbaijan, ANC decreases from 93.8% • Improve financing of the maternal programmes, and laws within andbeyond the health sector. Strengthen NCDs be provided as part of an inte- stry of Health General Directorate of

partnership and coordination grated approach to promote women’s Mother and Child Health and Family

between various stakeholders and and children’s health. Planning, TR Prime Ministry Under-

donors working in SRH areas, child secretary of State Planning Organiza-

health, gender equality and the em- tion and TÜBiTAK, 2009.

powerment of women. 12. Krumova T, Ilieva M. The health

• Increase government support for the status of Romani women in Bulgaria.

active involvement of civil society and Veliko Turnovo, Center for Intereth-

References

communities in the design, provision nic Dialogue and Tolerance “Amalipe”,

and evaluation of SRH policies and 1. Trends in maternal mortality: 1990- 2008.

programmes. In keeping with this, 2008. Geneva: WHO, 2010. 13. Social determinants of sexual and

efforts can also be scaled up to move 2. Report of the Office of the United Na reproductive health: Informing future

beyond the historical approach to tions High Commissioner for Human research and programme implementa

promoting SRH that focuses on the Rights on preventable maternal mor tion. Geneva: WHO, 2010.

deficit model towards one that also tality and morbidity and human rights. 14. A review of progress in maternal health

embraces the assets model and hence Geneva: Human Rights Council, in eastern Europe and central Asia.

accentuates resources of individuals 2010. Doc. A/HRC/14/39 New York: UNFPA, 2009.

and communities. A participatory 3. Shakarishvili G. Poverty and equity 15. Making pregnancy safer: adolescent

approach is a key part of this change. in health care finance: analyzing post- pregnancy [web site]. Geneva: WHO,

• Ensure the rights of adolescents to Soviet healthcare form. Budapest: 2011. http://www.who.int/mak-

age-appropriate information, confi- Local government and Public Service ing_pregnancy_safer/topics/adoles-

dentiality and privacy, and access to Reform Initiative and Open Society cent_pregnancy/en/

services and commodities. Reinforce Institute, 2006. 16. Singh S et al. Abortion worldwide: a

the Convention on the Rights of the 4. Machado MC et al. Maternal and decade of uneven progress. New York:

Child principle of evolving capacities child healthcare for immigrant popula Guttmacher Institute, 2009.

of the child for autonomous decision- tions. Brussels: International Organi- 17. Issues in adolescent health and devel

making and informed consent. zation for Migration, 2009. opment. Adolescent pregnancy – unmet

Indentify and reduce the barriers for 5. World Health Statistics 2011. Geneva: needs and undone deeds. A review of

(pregnant) adolescents to access HIV/ World Health Organization, 2011. the literature and programmes. Ge-

SRH services, including safe abortion 6. Conference document: The Millen neva,: WHO, 2007.

and post-abortion care services where nium Development Goals in the WHO 18. The Millennium Development Goals

abortion is legal. Enforce laws and European Region: health systems Report 2011. New York: UN, 2011.

policies that directly protect most- and health of mothers and children – 19. Marston C, King E. Factors that shape

at-risk adolescents, decriminalize the lessons learned. Copenhagen: WHO young people’s sexual behaviour:

behaviours that place them most at Regional Office for Europe (EUR/ a systematic review. Lancet, 2006;

risk, and ensure that they have access RC57/8), 2007. 368:1581-1586.

to the services they need and are 7. Lloyd CB. Growing up global: the 20. Azerbaijan Demographic and Health

protected from stigma. changing transitions to adulthood in survey 2006. Calverton, Maryland:

• Address the links between non- developing countries. Washington, DC, State Statistical Committee [Azerbai- 11

communicable diseases (NCDs) and National Research Council, 2005. jan] and Macro International Inc,

MDG 5. NCDs increasingly affect 8. Progress for children: Achieving 2008.

women and children across the the MDGs with equity. New York: (http://www.measuredhs.com/pubs/

RMNCH continuum of care. For UNICEF, 2010. pdf/FR195/FR195.pdf, accessed 1July

instance, obesity in women increases 9. Gender Justice and the M illennium 2011).

the risk of gestational diabetes, Development Goals. New York: 21. Report on the Progress towards the

pre-eclampsia, pregnancy-related hy- UNIFEM, 2010. Millennium Development Goals. Sko-

pertension, induced labour, caesarian 10. World Contraceptive Use 2010. (POP/ pje: Government of the Republic of

sections and stillbirths. The RMNCH DB/CP/Rev2010), New York: UN, Macedonia. 2009.

continuum of care provides several Department of Economic and Social 22. Keeping the promise: united to

opportunities to prevent, diagnose Affairs, Population Division, 2011. achieve the Millennium Development

and treat NCDs. The Global Strategy 11. Turkey demographic and health survey Goals. Resolution. General Assembly,

for Women’s and Children’s Health 2008. Ankara: Hacettepe University Sixty-fifth session, Agenda items 13

recommends that health services for Institute of Population Studies, Mini and 15. New York: UN, 2010.

No.73 - 2011The Millennium Development Goals, social

determinants and sexual and reproductive

health: an overview in Europe

T

he social determinants of health Figure 1. Maternal mortality rate in selected western and eastern European

are directly linked to develop- countries, latest available data (3).

ment and therefore will directly

contribute to Europe’s ability to reaching,

or not, the set Millennium Development

Goals (MDGs) for the year 2015. Beyond

that year, the health sector will transform

these goals into a new challenge, called

“Health 2020”.

As an essential part of the WHO

Regional Office for Europe’s Member

States public health landscape, sexual and

reproductive health (SRH) is particularly

sensitive to the social determinants of

health. These determinants influence to

which extent a man or woman of repro-

ductive age can benefit from SRH services

in his or her country and thus, his or her

SRH health outcomes. In this article we

will highlight how these factors impact Economic and social status experience continued missed opportuni-

both the supply and demand side of SRH The relationship between poor SRH and ties for equitable access to care.

services and how this contributes to the poverty has been well established; not

accessibility, quality and affordability of only is the burden of ill SRH outcomes Migration and internally displaced

offered SRH services. greater in low resource settings, but populations (IDPs)

also greatest among the populations in While not traditionally thought of as a

Culture, ethnic diversity and age the lowest wealth quintiles in these low social determinant of health, experience

The countries that make up the European resource countries. Throughout Europe in the European Region with migrants

Region are diverse, with many different varying rates of utilization of antenatal and IDPs has clearly shown that migra-

ethnicities, cultural practices and age care and maternal mortality rates are tion is an important determinant that

groups. All of these factors have a rela- seen (figure 1 and 2). The correlation must be considered when addressing SRH

tionship with how SRH is perceived and between income and poor SRH indica- programmes and policies and improv-

practiced. For example early marriage and tors is easy to interpret; higher maternal ing SRH outcomes for individuals and

childbearing may be more common among mortality rates are seen in countries with communities. Armed conflicts disrupt

certain ethnic groups. Such practices may lower incomes level and greater utiliza- health services and IDPs in countries with

impact negatively on SRH as studies have tion of antenatal care services among territorial disputes are often unders-

shown that women who experience preg- higher income groups compared to lower erved in the field of SRH services and at

nancy and childbirth at a young age are at income groups. However, the relationship increased risk to adverse SRH outcomes.

increased risk of morbidity and mortality between poverty and poor SRH utiliza- Such conflicts also pose a threat to the

12 (1, 2). From a supply side such groups tion and outcomes is complex and may implementation of the national SRH

may be excluded from SRH services due reflect a variety of other issues that influ- agenda of countries, weakening the health

to issues such as lack of cultural sensitivi ence these inequities, such as: inability systems ability to deliver services and

ty and/or language barriers that limit the to access services due to opportunity its responsiveness for well implemented

interaction between the client and care costs; social exclusion due to discrimina- quality control mechanisms.

provider. Age may also affect the ability to tion and marginalization of select lower

access or receive services. While adoles- socio-economic or ethnic population Programmatic and policy gaps

cents may feel uncomfortable accessing groups; inability to demand equal and fair Many countries in the eastern part of the

traditional SRH health services for infor- treatment from providers due to feelings European Region find themselves in a

mation about SRH, societal attitudes and of exclusion; and inequitable distribution transitional period, moving away from

beliefs towards sexuality of adolescents of SRH services favouring higher income a centrally planned economy towards a

can also limit access to care through poli- areas (urban vs. rural). All of these factors merit-based society in a system of free

cies that prevent Youth Friendly Health interact together to create a complex envi- market mechanisms. In this era of finan-

Services or fail to recognize the rights of ronment that ensures that those who are cial crises and donor fatigue it is para-

adolescents to also have positive SRH. most vulnerable to poor SRH outcomes mount to rely more and more on eachSandra Tamar

Elisabeth Khoma-

Roelofs suridze

Figure 2. Use of antenatal care by different socio-economic groups stakeholders of the relationship between

in the European Region, latest available data (3). social determinants of health and SRH.

Reducing inequities in SRH requires in-

volvement not only of the health systems

but also education, labour and social

sectors. Advocacy about these inequities

should occur at all levels and across all

sectors in order to diminish the health

risks faced by all populations, particularly

vulnerable and marginalized groups.

Europe has an ambitious agenda wishing

to ensure universal access to SRH services

for all its citizens, relying on European

standards of care. It is time to act, learn

Figure 3. Age-standartized death rate (SDR) of cervical cancer among 0-64, from each other’s best practices and

per 100 000 and the coverage rate within the national screening implement the commitments that have

programmes in selected countries, latest available data (3). been made in 2000 on the UN MDGs and

in Cairo at the International Conference

on Population and Development. With

the right commitment and the right

instruments to map and address the

social determinants of health and SRH,

we will quickly get closer to a society with

reduced inequalities and more accessible

and affordable care.

H.E. Sandra Elisabeth Roelofs,

WHO Europe Goodwill Ambassador

for health-related MDGs,

Chairperson of National Reproduc-

tive Health Council, Georgia,

Tamar Khomasuridze, MD, PhD,

country’s own resources, local public- health care system will help close this gap UNFPA AR, Georgia

private partnerships, creative co-financing and improve outcomes. Taken this one

schemes of federal, regional and mu- step further and incorporating health For correspondence contact:

nicipal governments and strengthening education on reproductive tract cancers geoccm@caucasus.net

of the medical insurance infrastructure and screening into the education sector

(increasing the insurance base can lead helps strengthen the efforts and coverage

to inclusion of more SRH services in the of the health system. Countries who have References 13

basic care package). Such actions require recognized these gaps and have imple- 1. Mayor S. Pregnancy and childbirth

coordination among the stakeholders of mented well organized national screening are leading causes of death in teenage

the existing donor, government and civil programmes with a high coverage rate girls in developing countries. BMJ,

society community in order to ensure achieve much better outcomes in terms of 2004;328:1152-1159.

programmatic and policy gaps are mini- cervical cancer morbidity and mortality 2. DuPlessis HM, Bell R, Richards

mized and that synergy exists between (figure 3). T.Adolescent pregnancy: Understand-

sectors. For example, national policies ing the impact of age and race on

that address reproductive tract cancers Conclusion outcomes. J Adolescent Health, 1997;

need to recognize that lack of organized National ownership of an area like SRH 20: 187-197.

population-based preventive and early can only be reached through increased 3. WHO Health For All Database. Ac-

detection services leads to negative SRH political commitment and strong con- cessed September 24 2011 at: http://

outcomes. Implementation of screening tinuous lobbying for SRH and rights of www.euro.who.int/en/what-we-do/

and early detection, a very cost-efficient individuals and populations. Essential to data-and-evidence/databases/europe-

measure, into each country’s primary this commitment is recognition by all key an-health-for-all-database-hfa-db2

No.73 - 2011You can also read