Assemblage Theory and Town Foundation in Medieval England

←

→

Page content transcription

If your browser does not render page correctly, please read the page content below

Assemblage Theory and Town Foundation

in Medieval England

Ben Jervis

It is proposed that our understanding of medieval town foundation is limited by a fail-

ure to appreciate that ‘town’ is a relational category. It is argued that urban character

emerges from social relations, with some sets of social relationship revealing urbanity and

others not, as places develop along distinctive, but related, trajectories. This argument is

developed through the application of assemblage theory to the development of towns in

thirteenth-century southern England. The outcome is a proposal that, by focusing on the

social relations through which towns are revealed as a distinctive category of place, we

can better comprehend why and how towns mattered in medieval society and develop a

greater understanding of the relationship of urbanization to other social processes such as

commercialization and associated changes in the countryside.

Introduction society might transcend the urban/rural divide im-

posed through modern analysis.

Assemblage theory (after Deleuze & Guattari 1987; This approach is used here to move away from

see also De Landa 2006) offers a means of think- seeking to define the town, a task which, as discussed

ing through archaeological data which forces us to below, is fraught with difficulty, and towards explor-

explore how evidence finds meaning in relation to ing the forms which medieval urbanism takes. In so

other fragments of knowledge about the past. Here doing, the value of assemblage theory to both me-

it is proposed that thinking through assemblage the- dieval archaeology and settlement archaeology more

ory, which, along with associated ‘relational’ ap- generally, in shifting the focus of analysis from seeing

proaches, has increasing currency in both archaeology places as simply urban to reflecting upon the pro-

(e.g. Fowler 2013; Harris 2014; Hodder 2012; Jervis cesses which make them so, is demonstrated (see also

2014; Jones 2012) and human geography (Allen 2011; Christopherson 2015). A problem with defining towns

Dewsbury 2000; Dewsbury et al. 2002; McFarlane is that they take different forms and perform different

2011), a radically different approach to the study roles. Attempts to define urban archaeological signa-

of the medieval town can be taken (see Astill 1985; tures have often resulted in frustration, highlighting

2009; Dyer 2003, for general reviews of previous ap- patterns of similarity as well as dissimilarity between

proaches). If we view the town as relational (that is, town and country, suggesting that fresh perspec-

formed through the performance of social relation- tives might be required (see, for example, Egan 2005;

ships), then it stands to reason that it emerges through Pearson 2005). Through a consideration of the nature

some relationships and not others. Therefore, it is of categorization processes the first part of this pa-

through these relations that a place is defined as ur- per proposes that categories of town emerged as peo-

ban and that the process of urbanism had relevance to ple related to places and communities, meaning that

medieval people. By implication, it might be argued different understandings of urbanism might exist si-

that the town does not reveal itself through all sets of multaneously. Taking this as a starting-point, the re-

relations, suggesting that some elements of medieval mainder of the paper uses archaeological evidence

Cambridge Archaeological Journal 26:3, 381–395

C 2016 McDonald Institute for Archaeological Research. This is an Open Access article, distributed

under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution licence (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted re-use, distribution,

and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

doi:10.1017/S0959774316000159 Received 30 Mar 2015; Accepted 14 Feb 2016; Revised 11 Dec 2015

Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. IP address: 46.4.80.155, on 23 Oct 2020 at 04:52:25, subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms.

https://doi.org/10.1017/S0959774316000159Ben Jervis

from the Weald of Sussex (UK) to propose that, standing is partial, directed by categorizations made

rather than being a characteristic of a place, urban- for specific purposes and passed on to us through an

ism is an emergent quality of assemblages of ac- incomplete historical record. Furthermore, inconsis-

tants (that is, the people, things and materials which tencies between sources make it difficult to develop a

participate in social practice) linked through perfor- firm definition of what a town is. Attempts to over-

mances of everyday life. This discussion leads to a come this by creating a check-list of urban charac-

call to move from an emphasis on site-specific in- teristics (Biddle 1976; Reynolds 1977) have been un-

terpretation to a multi-scalar consideration of the successful, as only the largest towns fulfil all of the

processes through which different forms of urban- criteria and certain characteristics might be consid-

ism come to be revealed through the analysis of ered as more important than others. A pragmatic and

past practice, finding parallels with recent consider- commonly used definition is that towns are places

ations of urban processes in Scandinavia in particu- which have an economy that is largely dependent

lar (Ashby et al. 2015; Christopherson 2015; Sindbaek upon activities other than agriculture (Dyer 2002, 7).

2007). Whilst this is satisfactory, in that it allows the dis-

tinction between urban and rural places to remain

Defining towns: unpacking an analytical black-box fuzzy, its vagueness limits its utility. Dyer (2002, 7)

cautions against critiquing the contrast between town

We all think we know what the word town means. A and country too deeply, as it is an important analytical

picture of a relatively small but densely settled place, distinction, which can be considered relevant within

a commercial centre with some administrative func- the medieval mind.

tion, probably springs to mind. Yet the definition of Whilst it is true that the category of town was

the word continues to be debated in medieval studies. meaningful in the medieval period, Masschaele’s

‘Town’ stands for more than a place; it is an analytical (1997) work shows how ‘town’ was interpreted differ-

‘black-box’ (that is a concept which crystallizes past ently depending upon the context of categorization.

action and circulates as a referential starting-point; see Historians and archaeologists have specific reasons

Latour 2010, 160), standing for a tradition of histori- for wanting to categorize places as urban or rural;

cal and archaeological study (see Fowler 2013). The they seek, for example, to know how town life dif-

term circulates as a reference to a particular type of fered from village life, or how agricultural production

settlement which does not appear to be primarily ru- related to the marketing of produce. The debate has

ral in character. Debates about what exactly we mean been undertaken in relation to the circulating refer-

by town are not new, being as old as the medieval ence of the town—we know this category is real, but

settlements themselves. Masschaele (1997, 79–83) dis- what were these places for? Beresford saw towns as

cusses how tax assessment forced the urban character an instrument of lordship, founded to market agricul-

of places to be considered, as towns and villages were tural surplus and generate income; they were ‘spe-

taxed differently. Places such as Andover (Hamp- cialized centres of making and dealing’ (Beresford

shire), whose community probably saw themselves as 1967, 55–6). Medieval society is typically seen as being

urban, having a guild merchant and borough charter, agrarian and, therefore, towns have been set in oppo-

for example, were taxed at the rural rate. This high- sition to rural settlements, as an anomalous feature

lights how places might simultaneously have been in an agricultural economy. Following Hilton (1992)

perceived as urban and rural. Assessments made for in particular, scholarship shifted towards seeing ur-

specific purposes categorized places as towns, with ban and rural as united within an economic system,

these categorizations being enacted through admin- with towns being necessary for the disposal of sur-

istrative practice. As these practices were repeated, plus and the manufacture and exchange of other com-

through the enacting of this assessment, so ‘town’, as modities. In order to function, towns require a de-

a reference to a particular process of categorization gree of freedom or liberty, creating the town, or bor-

circulated, forming a reference against which towns ough, as a specific category of place (Hilton 1992,

as a category of place were understood. Importantly, 10–14). Hilton points to similarities in the social or-

this medieval categorization of places shows that set- ganization of town and country: tensions between

tlements without borough charters (that is, granted ruling and peasant classes and the organization of

certain freedoms seen to be fundamental to urban life) economic activity around the household unit in par-

could be perceived of as towns. ticular. He uses this to demonstrate that towns were

Through historical documents, therefore, we not anomalous within medieval society; however, we

have inherited an understanding that some places might also ask whether these similarities relate to the

were towns and that some were not; but this under- ambiguity over the classification of places discussed

382

Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. IP address: 46.4.80.155, on 23 Oct 2020 at 04:52:25, subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms.

https://doi.org/10.1017/S0959774316000159Assemblage Theory and Town Foundation in Medieval England

previously. Perhaps towns are a useful category when to one on relationality and connectivity (see partic-

discussing economic networks, but in relation to other ularly Kowaleski 1995). I propose, however, that an

elements of life do not emerge as a distinctive cate- over-reliance on the urban-rural divide hinders the

gory. This past analysis has created a reference which development of a deeper understanding of the dy-

has circulated over the intervening centuries, leading namics of medieval society. Therefore, rather than us-

us to attempt to work backwards to try to place a ing archaeology to justify the extent to which a place

settlement within or outside this category (see also is a town, a further depth can be achieved by unpack-

Christopherson 2015, 112). I argue that this approach ing the urban black-box, taking the word ‘town’ out

has resulted in an analytical seizure. ‘Town’ as a cat- of circulation and de-constructing it, using the evi-

egory emerged and was ‘black-boxed’ through circu- dence to examine the process of becoming urban and

lation in the assessment of places for economic pur- to consider what this means, rather than to assess the

poses, be it gathering taxes in the past or undertaking state of being urban (see also Christopherson 2015).

economic history in the present. Hilton’s work has As demonstrated by Fowler (2013), the aim of archae-

been highly influential in placing the relationship be- ological analysis is constantly to critique this received

tween town and country into focus, leading to revo- wisdom, to go back to the evidence, to enter into di-

lutionary insights into the medieval economy (Astill alogue with it and, although remaining informed by

2009, 265; Dyer 2002, 3; Dyer & Lilley 2010, 81; Hilton past study, not to be led by it. As Latour (2005, 27)

1992, 17–18; Kowaleski 1995). However, this work has argues, the world is constantly in flux and there are

caused the distinction to circulate further as a useful no such things as stable categories, just processes of

analytical tool in the present, but perhaps masking coalescence which emerge and dissolve through ac-

areas of life where an urban/rural dichotomy is not tion. The action of study has allowed the black-boxed

apparent. concept of ‘town’ to continue to circulate and, in do-

If, however, we removed this pre-conceived di- ing so, has sent scholarship on a certain trajectory.

chotomy and worked from the archaeological evi- The aim here is to explore whether, by placing this

dence upwards, a clear distinction between urban and black-box to one side, by unpacking and re-packaging

rural would not emerge. Rather, we would see a highly it, new insights into the process of urbanization

varied spectrum of small and large, nucleated and (taken in the sense of a national phenomenon of the

dispersed, economically diverse and specialized set- nucleation and specialization of settlements) might

tlements. The category of town is an inheritance; it is emerge.

a black-box packed through the performance of me- It has been argued that towns emerged as a cat-

dieval life, the ongoing categorization of places and egory through the assessment of places for specific

the circulation of these categories through particular purposes. Jones (2012) perceives categories not as a

types of social practice. The process of urbanization priori distinctions, but as resulting from the emer-

can be viewed at multiple scales, being a widespread gence of similar entities from repetitive interactions

characteristic of twelfth- to fourteenth-century Eng- between people and materials, or ‘performances’. We

land, but also taking regional and local forms. Histo- can, therefore, expect there to be similarities between

rians such as Britnell (1996) and Dyer (2005) relate the these places categorized as towns through various

growth of towns to the increasing commercialization forms of assessment in the recent and distant past;

of society, fuelled by the export trade and the need to however, archaeological analysis in particular is often

generate increasing seigniorial income to fund royal guilty of placing a settlement into an a priori category

expenditure on wars. This led to the growth of profes- of ‘town’. A category is a means of classifying things in

sions and trades, as well as an increasing pressure to spite of their differences and, as such, rigid distinction

formalize trade through the granting of borough and and categorization might be seen as masking the per-

market charters. The process of borough chartership formative and heterogeneous nature of entities in the

clearly created a distinctive category of administrative past, the variability which is clear when one looks at

place, but one which, in other areas of life, was not medieval settlements in depth. Settlements, therefore,

necessarily sharply distinguished from other types of can be viewed as repetitive performances of interac-

settlement. Urbanization and commercialization are tions between humans and their surroundings. The

separate but closely related processes. Towns were performance of a place brings together human and

more than commercial places, and commercial activ- non-human participants, situating them spatially (a

ity took place outside towns. In modern discussions of similar perspective on the town as performed has been

definition and function, however, the key distinction reached by Christopherson 2015). A town (as defined

is between categories of urban and rural place, the by Dyer 2002) is never at rest: people move around

primary move having been from a focus on contrast it, materials transform into objects in workshops and

383

Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. IP address: 46.4.80.155, on 23 Oct 2020 at 04:52:25, subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms.

https://doi.org/10.1017/S0959774316000159Ben Jervis

buildings decay. Towns are not material settings for Urbanization in medieval Sussex: a summary and

urban life, nor are they collections of people. Rather, an approach

they are vibrant bundles of interactions between peo-

ple and materials and, as they are constantly in mo- Sussex is a county situated in southeastern Eng-

tion, forming and re-forming, ‘town’ might be con- land. By the thirteenth century, it was already par-

sidered a verb rather than a noun (Dewsbury et al. tially urbanized. In the southern part of the county, a

2002). Furthermore, the process of ‘towning’ or ‘be- number of settlements are recognized as towns. Some

coming urban’ might relate only to specific elements existed prior to the Norman Conquest of ad 1066,

of everyday life. Rather than underplaying Hilton’s principally developing from late Saxon burhs (de-

identification of similarities between urban and rural fended settlements). Further urban places, primarily

life, perhaps we should emphasize these and, rather ports, developed through the eleventh–twelfth cen-

than focusing on polarizing categories, explore why turies. It is worth pausing briefly to consider some

certain sets of social relationships became urban and of the elements of these places which have, in the

others did not. past, been used to define them as urban. These settle-

ments typically have regular street layouts, something

Shifting perspectives: medieval towns as which is seen as typical of towns. In Chichester, the

assemblages street alignment relates to the remnants of the Roman

town, whilst in other burhs, such as Lewes, the grid

So far it has been argued that the term ‘town’ relates can be seen as having a defensive function (Drewett

not to a way of being, but to a process of categoriza- et al. 1988, 333–9). In these planted settlements, land

tion, and that it is through the need to confront and was granted to local manors and religious institutions,

understand patterns of difference in settlement that creating a need for the regular division of space. Yet

various, sometimes conflicting, definitions have de- systems of land division and styles of architecture ap-

veloped. The aim of the second part of this paper is pear similar to those in surrounding rural settlements

to develop an approach through which it is possi- (see Reynolds 2003). Port towns have a specific func-

ble to understand better how these patterns of differ- tion, developing at strategic locations to control trade,

ence emerge and their implications for the wider social forming part of its infrastructure and being one end

form of medieval England. This requires an alterna- of a spectrum of landing-places along the coast. In-

tive approach, as conventional archaeological analysis dustry gradually shifted from rural estate centres to

might be argued to see the town as a stage or frame these new settlements; however, control was still ex-

for the action of urban life. Whilst we acknowledge ercised over access to resources, given the tenurial

that urban form changes with the fortunes of a town links between town and country. Yet, we can also see,

(see, for example, Lilley 2015), there remains a frac- for example in the evidence provided by material cul-

ture between the study of the sociality of urban life ture, the development of distinctive experiences of life

and its material manifestation. Materials are taken as in these places (e.g. Astill 2006; Jervis 2014, 110–18).

providing evidence of the adherence of a place to a The archaeological evidence demonstrates, therefore,

preconceived, black-boxed, notion of what a town is. both similarity and difference between these places

It is clear, however, that the places which we iden- and contemporary rural settlements.

tify as towns are highly varied in size and character. Following Butler’s (1993) discussions of gen-

The approach developed here focuses on social rela- dered identity, Gregson and Rose (2000, 447) argue

tions. Towns are more-than-spatial phenomena; they that places do not pre-exist action, but rather that

can be considered as bundles, or assemblages, of so- the performance of social relations brings them into

cial relationships between people, materials and their being. Places can be considered to be assemblages of

environment, grounded in physical space but taking social relations: through activity, assemblages ‘take

a permeable form in which they are entangled with place’ (McFarlane 2011). If we view these towns

their surroundings. Through the application of this as assemblages, they are not planted stages, popu-

perspective to a specific case study, the urbanization lated by people, but rather places which emerged

of the Weald of Sussex, the processes of assembling from specific sets of social relationships. In general

towns and their implications at different scales will be terms, these relations might include the control of

considered. This will build towards an understanding resources through trade and manufacture and the

of the town, not simply as a category of place, but as a need to defend these resources from Viking raids,

way of becoming through specific, effective and mu- which materialized as towns, reiterated through the

tually constitutive relations between people and their performance of social life (see also Christopherson’s

surroundings. (2015) consideration of towns as performed places).

384

Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. IP address: 46.4.80.155, on 23 Oct 2020 at 04:52:25, subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms.

https://doi.org/10.1017/S0959774316000159Assemblage Theory and Town Foundation in Medieval England

This materialization of relationships caused these for example, has demonstrated how the form of some

places to develop along specific trajectories and Anglo-Norman towns in Wales and Ireland served

develop distinctive characters, their form structuring, to marginalize local populations. This marginaliza-

and being structured by, these performances. These tion can be seen as coded through the layout of urban

iterative performances reproduced certain normative space, becoming increasingly exacerbated with every

behaviour and attitudes, which restricted the ways performance of urban life from which these people

in which social relations could form and might be were excluded.

seen as underpinning the similarities which can be When thinking through the process of urbaniza-

seen both between these settlements and between tion, therefore, we can use these concepts of territo-

the towns and contemporary rural sites. However, as rialization and coding to perceive how the process

bundles of interaction, towns are also effective. They of becoming urban emerges through iterative gather-

are places where difference could be negotiated at ings. As will be discussed later, urbanization occurred

intersections of spheres of interaction, leading to the at multiple scales, coding action (or striating space) in

emergence of particularly urban forms of identity a stratified way with implications for new and existing

and practice (Christopherson 2015, 130). settlements.

It is in this brief consideration of urbanism in The focus of this paper is a second wave of ur-

late Saxon Sussex that we can begin to see the key ele- banization in Sussex, which principally occurred in

ments of an interpretive framework emerging. Firstly, the thirteenth–fourteenth centuries in an area in the

we can see towns as materializations of specific sets of northern part of the county, known as the Weald

social relations. This process of place-making is mu- (Fig. 1). This is an area which was sparsely settled in

tually constitutive of other urbanizing processes, the the pre-Conquest period, but was gradually cleared of

‘towning’ of people, things and practices. The perfor- dense woodland through the medieval period (Bran-

mance of these relations can be perceived as a process don 1969, 135–42; Chatwin & Gardiner 2012; Gardiner

of gathering (Lucas 2012) and is what Deleuze and 1996). Settlement was largely dispersed, with towns

Guattari (1987, 245) term ‘territorialization’. Social re- forming distinctive nucleated foci. Here the first town

lations gather a range of actants in a particular location to develop was Battle, in the eleventh century (Searle

and serve to bind them together. This creates an as- 1974, 69; James 2008), with further towns developing

semblage which can be identified through the tracing at East Grinstead (Leppard 1991), Crawley (Stevens

of these relations in the archaeological record, for ex- 1997; 2008), Horsham (Stevens 2012) and Roberts-

ample the laying out of streets and the division of land. bridge (Gardiner 1997a) in the thirteenth–fourteenth

Gathering, however, is a transitory process. The ap- centuries. There is also an ambiguous class of nucle-

parent permanence of the town is brought about by the ated settlements, termed by Gardiner (1997b) ‘substi-

effective nature of these relations. By creating a street tute towns’. These are places which served as central

grid, dividing land and articulating power through economic foci for dispersed rural communities, but

tenurial links, social relations are ‘coded’ (Deleuze & without many of the characteristics which might be

Guattari 1987, 47). Deleuze and Guattari (1987, 5) per- seen as typical of a fully-fledged town. It is these am-

ceive a world formed of flows, for example of matter biguous settlements, as well as the fact that the Weald

and ideas, which move across a social plane, becom- was sparsely settled in the Anglo-Saxon period, that

ing entangled in random and multiplicitous ways, the makes it a suitable area for developing new frame-

processes of territorialization (or gathering) through works for examining urbanization. The following dis-

which assemblages form. These social relations have cussion is broken into three sections. The first exam-

implications and can be perceived as ‘striating’ this ines the processes of gathering and coding through

social space, limiting the ways in which social re- which these places emerged; the second explores the

lations can form (Deleuze & Guattari 1987, 559–60). relationship of settlement foundation to the surround-

This striating of space is the process of coding, the ing landscape, discussing the issue of scale and intro-

ways in which behaviour is limited and an assem- ducing the concept of de-territorialization; and the fi-

blage re-iterated. There is still space for creativity and nal section considers the implications of this approach

change between striations, but within certain bounds. for shifting towards a focus on becoming, rather than

Therefore, the performance of social relations was being, urban.

both reproduced and constrained by normative be-

haviour, rules, regulation and the residues of past ac- Gathering assemblages

tion. Furthermore, this coding might be seen as push-

ing these entangled flows along certain trajectories, Urbanization might be considered to develop at the in-

exacerbating specific social processes. Lilley (2000), tersection of two different scales of social process. The

385

Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. IP address: 46.4.80.155, on 23 Oct 2020 at 04:52:25, subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms.

https://doi.org/10.1017/S0959774316000159Ben Jervis

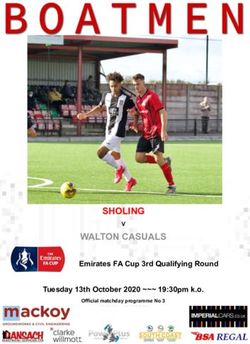

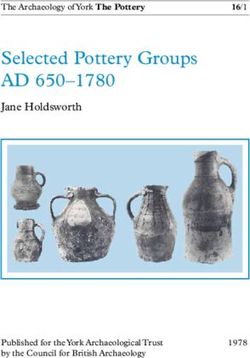

Figure 1. The location of towns and markets in Sussex. The area in grey is the Weald.

Boroughs: 1: Arundel; 2: Battle; 3: Bramber; 4: Chichester; 5: East Grinstead; 6: Hastings; 7: Horsham; 8: Lewes;

9: Midhurst; 10: Pevensey; 11: Rye; 12: Seaford; 13: Shoreham; 14: Steyning; 15: Winchelsea; 16: Withering.

Towns (urban places with market charters): 17: Crawley; 18: Mayfield; 19: Petworth; 20: Robertsbridge; 21: Rotherfield.

decision to plant a town formally, that is, through the A focus on lordship alone is misleading, imply-

acquisition of a borough or market charter, was gener- ing that towns are the result of human agency and

ally that of the lord holding a manor or estate. In gen- intentionality. Intentionality alone, however, does not

eral terms a lord may have had several motivations, equate to outcomes. By acting out intentionality, lords

chiefly economic: the need to generate revenue to pay acted upon existing networks of social relations, the

increased taxes arising from royal expenditure, a de- outcomes emerging as an effect of this process. If we

sire to retain revenue from the marketing of surplus take a view of agency as emerging from social in-

from their estate, and to generate tolls from market- teraction, as a property of relations (Bennett 2010, 24;

ing activity (Britnell 1996, 121). In the Sussex context Latour 2005, 63; see Jones & Boivin 2010 for a review of

a further motivation can be suggested. The pattern of approaches), then towns are not a means of seignio-

landholding in Sussex is considerably less fragmented rial expression, but rather a product of networks of

than in many areas of the country. The county was di- power in elite medieval society, perhaps most funda-

vided into five north–south divisions, known as rapes. mentally the tax burdens recognized as driving me-

Each rape was the possession of a lord, whose seat was dieval commercialization (Britnell 1996, 121; Hilton

situated in a port town. Across the rape a variety of 1985, 7). More accurately, it is not the town which

different landscape zones were present, providing dif- emerges from this process, but the borough or market

ferent resources and lending themselves to different charter. Documents such as charters can be considered

types of agricultural regime. The foundation of towns a form of black-box; they code social relations through

in the Weald by these lords or their associates, for ex- their relationship with other legal documents (Latour

ample at East Grinstead (rape of Pevensey), Crawley 2010), for example those which decree that marketing

(rape of Lewes) and Horsham (rape of Bramber), may can only take place in recognized locations. A char-

suggest the establishment of a marketing system in ter is more than a document: it is the materialization

which the full resources could be managed and pro- of an assemblage of lordship, which, through being

cessed. At this scale, therefore, town foundation can be enrolled into the performance of particular courses of

seen as an instrument of estate management (see also action, principally the marketing of resources, served

Goddard 2011), emerging from top-down economic to limit, or code, this action, focusing it on specific

pressures. places in the landscape.

386

Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. IP address: 46.4.80.155, on 23 Oct 2020 at 04:52:25, subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms.

https://doi.org/10.1017/S0959774316000159Assemblage Theory and Town Foundation in Medieval England

Examples of ‘failed’ towns show that the process These repeated processes of gathering both

of town foundation is about more than a charter (see emerged from and generated wider sets of social, eco-

Beresford 1967, 290–302). The foundation of nucleated nomic and political relations. They caused places to

settlements (including towns) in the Weald appears re- persist in the landscape, with past action constraining

lated to places in the landscape which were already how people and goods could flow across it and in-

important locations of gathering (Gardiner 1997b, 65). teract with each other. The presence of Roman roads,

East Grinstead, for example, is identified as a hundred the division of land into hundreds and the establish-

meeting place (Leppard 1991, 31). Churches and hun- ment of parishes are all examples of the past inter-

dred meeting places attracted regular gatherings and actions which had striated space in both a physical

became places of exchange; in many cases in the Weald and a conceptual way. People and things were di-

markets appear to precede permanent settlement (see rected across the landscape, whilst administrative di-

also Dyer 2003, 98, for a general discussion of the re- visions drew people to particular gathering places in

lationship between towns and existing landscape fea- preference to others. As McFarlane (2011, 654) states,

tures). For other places, such as Crawley, there does assemblage thinking ‘emphasizes the depth and po-

not seem to have been such a history of regular formal tentiality of sites and actors in terms of their histories’;

assembly, but its situation at a crossing of north–south it forces us to think about not just what phenomena

and east–west routes, at an administrative boundary emerged from, but the processes through which this

(between the rapes of Bramber and Lewes), suggests occurred. Once established as gathering places, struc-

that it may have formed a nodal point in the land- tures such as churches, landmarks denoting meeting

scape (Stevens 1997, 193). Roads through the Weald places or road junctions colonized as markets became

were sparse and therefore traffic through this dense foci of citational behaviour, recognized as locations

woodland was channelled along particular routes for the playing out of particular sets of social relations

(Gardiner 1997b, 70; Searle 1974, 46). Prior to the for- which reiterated their significance. We can see, there-

malization of markets through charters, we can per- fore, how these places, through the coding brought

ceive of flows of movement through the landscape. about by past action, emerged with wider territories

These built towards repeated processes of assembly (De Landa 2006, 104); they emerged both as persistent

which made these places, and associated communi- and central places within the landscape.

ties, persistent (De Landa 2006, 36). These processes Prior to town foundation, these places were al-

of assembly leave little archaeological trace. Exam- ready mediating the emergence and reiteration of

ples might be small quantities of pre-twelfth-century communities (see Harris 2014 for a discussion of this

pottery recovered from excavations in Crawley concept). As these places were formalized, for exam-

(Stevens 2008). ple through the granting of charters, a shift in the

The agency for town foundation emerges at the regional dynamic of power can be perceived, as a neu-

intersection of this assemblage of lordship (which tral gathering place became a regulated centre of pro-

might be considered one driver of the national trend duction and marketing. Commercial relations were

towards urbanization and commercialization) and lo- formalized, changing how people perceived them-

cal processes of gathering. Christopherson (2015, 119) selves through the performance of this activity, what

highlights a contrast between top-down, processual we might view as the emergence of specifically ur-

approaches to urbanism and post-processual, bottom- ban forms of identity, or a ‘towning’ of the self. As

up approaches. What the approach taken here demon- discussed below, it is through this process that we

strates is that these need not be mutually exclu- see a sharp distinction emerge between urban and

sive (Fleicher 2015, 134); lordship is as important as rural and the reformulation of communities; with a

more banal social interactions, with change emerg- process of becoming urban came a process of becom-

ing when these different spheres of interaction col- ing rural. As Hilton (1992, 10–14) demonstrates, in

lide. This has implications for thinking about the both town and country power structures were sim-

spatiality of power in the landscape. Rather than ex- ilar and, rather than seeing this process as enfran-

pressions of seigniorial or communal power, we can chising urban communities and excluding rural ones,

see towns as a negotiation of power relations, as we can see the specialization and intensification of a

creating new power structures both internally (e.g. commercial network, in which specialized people and

civic government) and regionally, as the formaliza- places emerged. However, bonds of mutual reliance

tion of towns furthered their existing role as foci ensured that connections were retained between town

of gathering, crystallizing territories which emerge and country. The urban market became a location in

with town foundation, but out of congealed historical which urban and rural social networks intersected

action. with each other, in which difference was negotiated

387

Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. IP address: 46.4.80.155, on 23 Oct 2020 at 04:52:25, subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms.

https://doi.org/10.1017/S0959774316000159Ben Jervis

and the town emerged as a particular type of place relations, a national phenomenon, negotiated locally

through marketing interactions. at the intersection of scales and realms of interaction.

Even within the three towns associated with the It is from here that we can progress to think more

lords of the rapes or other major landowners, dis- about these collisions, through a discussion of de-

tinctions can be seen. Crawley is a market rather territorialization and scale.

than a borough for example, implying that Michael

de Poynings, who acquired the charter, was not will- Extending place: de-territorialization and scale

ing to give the inhabitants the full freedoms enjoyed

by those living in Horsham and East Grinstead. This Scale has emerged as a key point of discussion. In one

may be because, as archaeological excavation demon- sense urbanization can be viewed at multiple scales,

strates (Cooke 2001; Stevens 1997; 2008), Crawley from an (inter)national phenomenon with regional

functioned principally as a site for the processing variants to the individual experiences of households

of iron and it was desirable to retain some seignio- and people who were transformed from a rural to

rial control over this resource. Market charters are an urban way of life. In another sense, action can be

also a characteristic of the so-called ‘substitute towns’, perceived as stratified, in the manner described by

which developed principally on land belonging to the Deleuze and Guattari (1987, 46–7). For them, assem-

crown (e.g. Rotherfield) or to the Archbishop of Can- blages are formed of other assemblages and interac-

terbury (e.g. Wadhurst, Uckfield and Mayfield: see tions can reverberate between scales. These scales are

DuBoulay 1966, 125, 137) (Fig. 2). These settlements not neatly nested into each other, but are enfolded

appear to have developed at similar kinds of central with one another. If we think of an assemblage as

places, with informal plots surrounded by demesne constituted of a variety of actants, then each actant is

land developing around market places and market an assemblage in itself. Each actant might, simultane-

charters serving to formalize existing commercial ac- ously be a part of other assemblages, a process termed

tivity (Gardiner 1997b, 71). Monastic and royal es- de-territorialization, as through these actants, assem-

tates were managed for different reasons to seignio- blages extend beyond themselves. It is this process of

rial ones; often produce was intended for consump- de-territorialization that enfolds scales. An example is

tion by landowners, with varying proportions being the borough charter discussed above: it is simultane-

marketed (Hare 2006). Within this context borough ously part of the assemblage of medieval elite society

privileges were not appropriate, but there were ben- and of the place to which it relates; it de-territorializes

efits to being able to profit from existing marketing. the local performance of place, folding it into the na-

Tenurial geography was such that these central places tional web of interactions through which we can per-

were parts of different constellations of relations. As ceive a broader process of urbanism. Therefore assem-

with the seigniorial towns it can, however, be argued blage theory becomes a useful tool for overcoming the

that market settlements emerged at the intersection divide between local and larger-scale studies of town

between two scales of interaction, the local and the foundation (see also Allen 2011, 277; Latour 2005, 173).

administrative. Our settlements are themselves stratified assem-

Deleuze (1995, 160) states that it is not ‘begin- blages: each is formed of households and individuals,

nings and ends that count, but middles’. It is this em- but is a part of larger assemblages which are the rapes,

phasis of the middle that a consideration of towns estates, Sussex and local, regional and national urban

as processes brings out. Urbanization is one event in networks, for example. These assemblages are not dis-

a longer trajectory of place-making, emerging from crete, but overlap with one another, the town being

existing, iterative, processes of gathering which code articulated differently through enrolment in these net-

action and striate social space. The agency for change works. This demonstrates the key point from the first

emerges when existing networks of interaction col- section of this paper, that ‘town’ is not a single cate-

lide. If we see gathering and re-iteration as perfor- gory of place, but rather a mode of becoming which

mances, then ‘performativity is about connection’ occurs through enrolment in these different sets of in-

(Dewsbury 2000, 476). We can see that through the teractions. The current section explores this contention

connection of different territorialized sets of actions further, through a consideration of the relationship

(or assemblages) new things, boundaries, territories between our towns and their rural surroundings and

and places emerge. Seigniorial boroughs emerge from their place within regional urban networks.

the collision of elite networks and localized perfor- Excavations in Crawley demonstrate that in the

mances of place and substitute-towns through sim- thirteenth century, iron production became an ur-

ilar collisions with different tenurial networks. This ban industry. This shift was accompanied by an in-

illustrates how towns emerged from different sets of tensification of output, with the close relationship

388

Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. IP address: 46.4.80.155, on 23 Oct 2020 at 04:52:25, subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms.

https://doi.org/10.1017/S0959774316000159Assemblage Theory and Town Foundation in Medieval England

Figure 2. Market foundations on the Wealden estate of the Archbishop of Canterbury (grey area).

between producer and market, and the concentra- of mediating social relationships across scales, fold-

tion of production on the estate in a single centre. ing the ‘global’ or non-local processes into personal,

Iron, then, was an actant in the reiteration of Craw- small-scale performances (Bennett 2010, 42). It was

ley, but was enrolled in multiple other processes of this de-territorialization which caused externalities to

assemblage as it was put to use. The product de- act upon the process of iron production. Increased de-

territorialized the industry: iron might be considered mand from the army and the London market meant

an assemblage convertor (Deleuze & Guattari 1987, that production needed to intensify, with producers

378), a medium through which localized interactions devoting more time to iron working (Cleere & Cross-

between people and materials are joined to interac- ley 1985, 89–91; Hodgkinson 2008, 37). Here, then,

tions and processes occurring in different places, at we can see another confrontation of scale, between

different speeds. Objects and materials offer a means localized production and external demand, with the

389

Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. IP address: 46.4.80.155, on 23 Oct 2020 at 04:52:25, subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms.

https://doi.org/10.1017/S0959774316000159Ben Jervis

agency for change emerging in this coming together. Urbanization was, therefore, part of a wider eco-

Iron production did not occur in isolation. Coupled to nomic change, what might be termed commercializa-

the intensification of the iron industry was the greater tion, which was negotiated through changing relation-

management of woodland resources and clearance for ships with resources. The presence of informal mar-

agriculture. Timber was a valuable trade resource and kets set places on trajectories through which market-

wood also had to be managed for fuel (Galloway et ing activity intensified, was formalized, and became

al. 1996; Gardiner 1996, 123; Pelham 1928). Some ev- enrolled in the performance of places which were dis-

idence of coppicing and woodland management can tinct from both other places and the places that they

be seen in the wood fuel remains from excavations had been. The presence of chartered markets ‘over-

in Crawley (Stevens 2008, 141). This clearance cre- coded’ the existing system of informal markets and

ated further demand for iron tools (Hodgkinson 2008, dispersed settlement (Deleuze & Guattari 1987, 71–3).

37). The de-territorialized nature of iron enrolled it Urban places, as sets of social relations, emerged out

in multiple processes of change. As an industrial re- of previous performances, and were effective in that

source, like cattle required for leather production (see they generated new relations, as well as reiterating

Brandon 1969, 149; Saunders 1998; Searle 1974, 5, for existing ones, which distinguished them from other

evidence of tanning in towns), it mediated the rela- places. Social space was further striated, but with cer-

tionship between the intensification of agricultural tain constraints (the need, for example, to undertake

activity and the intensification of production. Both in- multiple forms of economic activity in an unspecial-

dustries ‘became urban’ as conflicting demands on ized economy) being smoothed and a new form of

land, labour and resources led to the emergence of social space, in which a distinction between town and

increased specialization, as part of a commercializing country was perceptible, emerging.

economy. Dewsbury (2000, 477) argues that it is at points

In this specialization, we see the negotiation of of rupture, where performance is disrupted, that we

the polarized divide between town and country, with reveal ourselves, as it is in these situations that re-

towns becoming Beresford’s (1967, 55–6) ‘specialized negotiation takes place. Therefore, it is at points of

centres of making and dealing’. But these production change and rupture that towns reveal themselves as

processes were neither exclusively urban nor rural. a distinctive entity, as urbanism comes to be defined

The urban processing of rural resources created a di- in relation to other modes of becoming. There are,

alogue which made a firm divide between town and however, elements to Crawley which are distinctly

country untenable, if we base our understanding on rural. Fields were laid out with the town and industry

social connections rather than the spatial differentia- was seemingly organized at a household scale (Cooke

tion of activity. In this light, we might argue that that 2001; Stevens 2008, 145). But in the performance of

the settlement is a less useful frame for analysis than production and marketing it is revealed as a differ-

seeking to understand the system and the intercon- ent kind of place to those which surround it. It be-

nections between different activities through which came urban as the processes which constituted it as

specialization emerged and became focused in spe- a place changed and caused its position in relation

cific locations. As Jones and Sibbesson (2013) argue to other places, its region, people and resources to be

for the emergence of the Neolithic, we can perceive re-negotiated. Importantly, allied to this process, we

of multiple, entangled, trajectories of action, with the can see other places as becoming rural. Whereas in

agency for change emerging at their intersections. In the Wealden context dispersed settlements had been

this context iron production and agriculture might be normal, commercialization brought about a point of

perceived of as two such trajectories. Urban character rupture, in which they are revealed as different to

developed out of these intersections, rather than being the emerging urban centres, and in which the perfor-

bestowed upon a place through the act of foundation. mance of these places takes them on a divergent tra-

It was in the performance of social practice that peo- jectory, as specialized producers and managers of re-

ple, places and things became urban, as towns were sources. At the time of urbanization, therefore, we see

actualized through processes of assemblage. That is to an intensification of occupation and agricultural activ-

say, urbanity was not a given property of a place, but ity, a shift in the economy of the region to one based

was re-iterated and improvised. Urbanism is not de- on small-scale, specialized, production. This coloniza-

fined as a set of characteristics, but as a quality defined tion of the woodland transformed it from a wild to a

in relation to other ways of becoming that emerged managed landscape, a process of which urbanization

out of alternative entanglements of these courses of was one part.

action, resulting in multiple forms of both urban and This consideration of the relationship between

rural experience. towns and their surroundings brings us to the wider

390

Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. IP address: 46.4.80.155, on 23 Oct 2020 at 04:52:25, subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms.

https://doi.org/10.1017/S0959774316000159Assemblage Theory and Town Foundation in Medieval England

commercial networks within which these settlements nomic networks. Increased demand for Wealden iron

participated. The full range of pre-urban commercial pulled them into supra- regional networks of sup-

connections in the Weald is difficult to re-construct ply and consumption. The impact of major events,

owing to the limited number of excavations and the such as warfare, became localized through the de-

small number of finds recovered from them. With territorialization of iron, having a transformative ef-

the intensification of the management of rural re- fect on the towns, driving them towards more in-

sources and production came the intensification of tensive production and more explicit differentiation

commercial activity. The coastal ports were conduits from surrounding settlements. These were not net-

for Wealden products, particularly timber (Pelham works through which goods simply passed, but were

1928). Pottery production centres developed around performative, transformative networks in which ac-

the fringes of the Weald, their position determined tivities such as trade mediated processes of becoming

in part by access to markets (Gardiner 1990, 49). Pot- urban at multiple scales. This was not in the sense of

tery from Surrey, presumably transported through the adhering to a particular urban template, but rather

Weald, appears at coastal sites. Finds of French pot- a process of transformation in which urban assem-

tery in Horsham (Stevens 2012) and Crawley (Stevens blages take on the appearance of other, similar places,

1997) perhaps hint at return trade. The pre-urban mar- and become distinguished from their surroundings.

kets were already nodes in commercial networks, the Furthermore, as urbanism was performed at different

flow of goods around Sussex was already coded, caus- scales, so various experiences of urban life, multiple

ing trade to take place in particular places and not in urbanisms, occurred as people became urban through

others. The Wealden towns therefore emerged in re- their enrolment in different zones of the assemblage.

lation to these existing urban centres. Whilst towns By looking at the material actants enrolled in the

were not direct copies of others, existing urban struc- constitution of urban places, we can see how towns

tures acted on the form that new towns took. This are not separated from wider society, but emerge

was not so much a case of copying street layouts, but with other forms of sociality. Whilst urbanism gath-

rather ways of dividing space, assigning land and do- ered actants in processes of making and trading, it

ing business (cf. discussion by Lilley (2010) of towns also de-territorialized the town, causing ruptures in

in Devon and Hampshire). The differences between traditional ways of doing through which a contrast

religious and seigniorial foundations in terms of lib- between urban and rural becomes visible. It is in

erties (the granting of borough or market charters) these moments of rupture that we can perceive a cat-

demonstrates an enfolding of scale, as marketing cen- egory of town emerging. This process of becoming

tres were founded in relation to estates, whilst taking urban is allied with, in the Weald, processes of be-

the form of other settlements which emerged through coming rural, as part of a wider commercializing and

similar processes. managing of the landscape. Town and country can-

Processes of urbanization in one town were con- not, therefore, be separated in a processual sense as

nected to those in other towns, a point well demon- they define each other; processes of becoming urban

strated by Sindbaek (2007), who shows how exchange are enmeshed in processes of becoming rural. These

networks mediate the emergence of different types actants are the media through which scales are en-

of urban place. These marketing connections de- folded, as demand in distant places pulled local per-

territorialize towns, with action in one place having formances of gathering in the market into wider pro-

implications for others. Therefore, urban processes in cesses driven by factors such as taxation and war-

a single place can be seen as enfolded with those in fare. The assembly of the town, therefore, flowed be-

other places at a regional scale. This has two impli- yond its physical borders; through networks of in-

cations: firstly, activity in one town cites that in oth- teraction spatial and commercial territories emerged

ers, creating a category of places joined through the into which the town was de-territorialized (see De

performance of similar forms of commercial activity; Landa 2006, 104). These might be classed as hinter-

secondly, we can see new forms of urban sociality lands, but rather than seeing towns as controlling

emerging as towns became sites of negotiation be- these spaces, I am arguing for spaces emerging which

tween the local networks discussed earlier in this sec- are defined in relation to these new centres. As they

tion and wider commercial networks. The very rela- become urban, so people become affiliated with a mar-

tionships which constitute towns also de-territorialize ket, enter into regional networks of commercial inter-

them, forcing them into relations with other towns and action and are enrolled in processes which over-code

markets. Links to south coast ports and to London existing social relations. Through these interactions

simultaneously contributed to the coming together towns form, becoming an active presence in the social

of these places, but also situated them within eco- landscape.

391

Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. IP address: 46.4.80.155, on 23 Oct 2020 at 04:52:25, subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms.

https://doi.org/10.1017/S0959774316000159Ben Jervis

Multiple urbanisms idence to trace the areas of medieval society in which

urbanism is significant and those in which it is not,

This paper began with a discussion of issues sur- rather than taking as a starting-point that a place is

rounding the definition and recognition of towns and a town and that we should, therefore, expect certain

has gone on to highlight the variation amongst places things of it.

which we might categorize as urban. It has been ar- We can push this argument further still, to ques-

gued that, rather than focusing on the town as an tion whether places are always towns. If we view

entity, a deeper understanding might emerge if we places as reiterated through performance, and de-

focus analysis on the processes through which social termine that urbanism reveals itself through certain

change was mediated and friction between scales ar- sets of social relations and not through others, we

ticulated. This analysis leads to a contention that not can view urbanism as something of a flicker, rather

only do different forms of urbanism exist, but that than a constant. The processes which weave the fab-

if urbanism emerges at intersections between assem- ric of a place are transformative, but do not shift

blages (as argued, for example, in the case of the iron a place to an urban state; rather they cause urban

industry), towns emerge through various forms of dis- qualities to surface. These processes are the medium

course (McFarlane 2011, 652). Both urbanization and through which a place becomes urban, but perhaps

its related process of commercialization can be consid- also, as they cease, might be perceived as processes

ered as wide-scale processes formed through localized of unbecoming, as ruptures heal over and the dis-

interactions. Elsewhere towns also formed in similar tinctions that they bring about dissolve. Over the

ways, as coalescences of associations, but did not form longer term, ruptures are apparent in the different

a single type of town but multiple forms of urban as- trajectories that places take, creating a spectrum of

semblage, manifesting as various forms of urban iden- urban places. Urban trajectories can be perceived at

tity and sociality (Thrift 2007, 161). It is less that we can the national scale, but locally we can see different

create a typology of towns, but more a case that people forms of coding emerge, the social spaces of settle-

assemble their own urbanisms as they experience and ments and regions being striated as places are de-

partake in social relations; towns are not found, but territorialized in different ways, manifesting as the

are actualized as they are enacted within an assem- contrast between boroughs and substitute towns, for

blage (Dewsbury 2000, 482; McFarlane 2011, 665). As example. As the processes that cause ruptures are ex-

discussed above, it is at points of rupture that towns acerbated, so the presence of urban qualities becomes

reveal themselves. This is as much the case in the di- more vivid. Perhaps, then, the reason that towns are

vision between urban and rural which emerges in the so elusive is that they are emergent, coming into

Weald in the thirteenth century as in the tax assess- view in different ways through different processes,

ments discussed by Masschaele (1997), where towns of which historical and archaeological research is

reveal themselves through an inability to be taxed just one.

on agricultural produce. Following Butler (1993) and

Gregson and Rose (2000), it was argued that towns are Conclusion

not stages for action, but are produced through per-

formances. Therefore, towns are not inhabited, but are This paper set out to utilize assemblage theory to de-

produced through dwelling in space (McFarlane 2011, velop new perspectives on processes of urbanization

651), emerging through specific forms of relationship in medieval England. Principally this entailed mov-

which cause tears in the social fabric and reveal dif- ing from understanding ‘urban’ as a state of being, to

ference. Being urban is, therefore, not a characteris- a state of becoming, to highlight the varying forms and

tic of a place; urbanism is a property which emerges roles taken by places that we recognize as towns in the

through social interactions. Industry becomes urban medieval past. The consideration of town as an ana-

as it enacts a divide between towns and other places, lytical black-box served to demonstrate that categories

just as other activities, such as the cultivation of fields emerge through action, and this was developed fur-

in Crawley, appear to transcend the urban and rural ther when it was argued that towns appear at points

divide. Rather than focusing at a simple level on sim- of rupture in social practice. By viewing the town re-

ilarities and differences between rural and urban life, lationally, several key conclusions have been reached.

or particular sites, an assemblage approach allows us Firstly, towns reveal themselves as the performance

to de-territorialize our site, follow the flows and the of relationships between scales of interaction creates

relationships which constitute it and understand how difference. Secondly, these processes of emergence

contrasts emerge through which urban places reveal have implications, as action comes to be coded

themselves. In other words, we can work from the ev- and places develop along trajectories, in which they

392

Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. IP address: 46.4.80.155, on 23 Oct 2020 at 04:52:25, subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms.

https://doi.org/10.1017/S0959774316000159You can also read