8 Plagal Cadences inFanny Hensel'sSongs - UO Blogs

←

→

Page content transcription

If your browser does not render page correctly, please read the page content below

8

Plagal Cadences in Fanny Hensel’s Songs

Stephen Rodgers

When I teach plagal cadences, I often put the word “cadence” in scare quotes,

for the fact is, most plagal cadences are not really cadences at all—if, that

is, we see a cadence as the structural ending of a theme, section, or piece.

Most plagal cadences come after authentic cadences; they are post-cadential.

William Caplin has stressed this point in much of his work on closure in

Classical and Romantic music. In Classical-era music, he argues, true plagal

cadences are virtually nonexistent. In his book Classical Form, he writes,

“An examination of the classical repertory reveals that [the plagal cadence]

rarely exists—if it indeed can be said to exist at all.”1 In his forthcoming book

Cadence: A Study of Closure in Tonal Music, he notes that even in music from

the first half of the nineteenth century the plagal cadence is so rare as to be

“rejected as a standard category of cadential closure.”2

You will note that there are no scare quotes in the title of my chapter. That is

because Fanny Hensel is an exception to this rule. There are enough bona fide

plagal cadences in her songs—not plagal “cadences” but plagal cadences—to

suggest that, for her, this kind of cadence should be accepted as a category of

cadential closure.3 In many songs scattered through her output, she sidesteps

authentic cadences and replaces them with plagal cadences—and she does so

not just at the end of themes and sections, but also at the end of entire pieces.4

In the process, she does something as radical as it is simple: she elevates the

plagal cadence from its conventional status as a “cadence confirmer” to that

of a “cadence maker,” casting it not in a supporting role but in a starring role.

And in this way, she showcases yet another facet of her tonal ingenuity.5

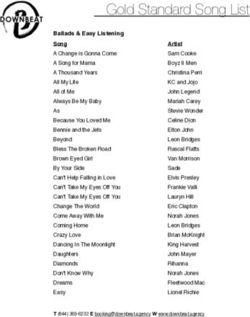

Table 8.1 lists those songs by Hensel in which the main structural cadence

is not V–I but IV–I—or, in some cases, a variant of a plagal cadence, what we

might call a diminished plagal cadence (vii o43 –I), where the bass moves from

4̂ to 1̂ but one of the upper voices moves from 7̂ to 1̂. (The table indicates not

only the “H-U” number for each song and when each song was composed,

but also where each song can be found, especially since several have not been

Stephen Rodgers, Plagal Cadences in Fanny Hensel’s Songs In: The Songs of Fanny Hensel. Edited by: Stephen Rodgers,

Oxford University Press (2021). © Oxford University Press. DOI: 10.1093/oso/9780190919566.003.0008.Table 8.1 Hensel’s Songs That End with Plagal Cadences

Title H-U Date of Closing Location of Score

Composition Progression

An die Entfernte 105 1823 viio43–I Unpublished; available via the digital collection of the

Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin (45 Musikstücke, MA Ms. 34,

pp. 30–31)

Der Eichwald brauset 170 1826 viio43–I Published by Breitkopf & Härtel

(Ausgewählte Lieder, vol. 1)

Neujahrslied 191 1826 IV–IV6–I Unpublished; available via the digital collection of the

Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin (62 Musikstücke, MA Ms. 35, p. 73)

Sehnsucht 217 1828 IV–I Published by Furore (Achmed an Irza)

Wonne der Wehmut 227 1828 IV–I Published by Dohr (Drei Klavierstücke)

Im Hochland Brüder 236/5 1829 IV–I Published by Furore (Liederkreis)

Zu deines Lagers Füßen 245 1829 iv–I Published by Furore (Lieder ohne Namen, vol. 2)

Once o’er my dark and 274 1834 iv–I Published by Arts Venture

troubled life (Three Poems by Henrich Heine)

Fichtenbaum und Palme 328 1838 iv–I Published by Breitkopf & Härtel

(Ausgewählte Lieder, vol. 2)

Erwache Knab’ 431 1846 iv–I Published by Karthause-Schmülling

(Die späten Lieder)

Bitte 440 1846 viio43–I Published by Bote & Bock (Sechs Lieder, Op. 7)Plagal Cadences in Fanny Hensel’s Songs 131

published.)6 In these songs there is simply no authentic cadence in the vi-

cinity of the song’s ending to signal a strong structural close. Indeed, in many

of these songs there is not an authentic cadence at all. The job of closing is

left to a kind of stand-in—a second stringer, if you will, a plagal cadence that

steps up to complete what an authentic cadence could not.

In the following pages I examine three of these songs: “Zu deines Lagers

Füßen,” H-U 245; “Bitte,” Op. 7, No. 5; and “Erwache Knab’,” H-U 431. I choose

these songs for three reasons. First, they extend across Hensel’s song output.

She wrote “Zu deines Lagers Füßen” in October of 1829, just shy of her twenty-

fourth birthday. “Bitte” and “Erwache Knab’,” by contrast, come from the very

end of her life; she wrote both less than a year before she died of a sudden stroke

at the age of forty-one. Together, these songs show that Hensel’s fascination

with plagal cadences spanned from her earliest to her latest works.

Second, the songs use different strategies to effect plagal closure. In “Zu

deines Lagers Füßen” a plagal cadence appears after an evaded authentic ca-

dence, such that what might have been a normative, post-cadential “Amen”

becomes the most structural cadence in the song; the plagal cadence, in other

words, follows a moment of harmonic surprise. In “Bitte” and “Erwache

Knab’,” on the other hand, the plagal cadences are the moments of harmonic

surprise, strange substitutions for what “ought” to have been V chords (a

shadowy viio 43 chord in “Bitte” and a IV chord in “Erwache Knab’ ”—which

is no less surprising for being triadic); the plagal cadences in these songs

appear precisely where we expect an authentic cadence to happen.

Finally, though on first glance the poems may seem quite different from

one another (the first is a love poem, the second is a hymn to night, and the

third is a poem urging a child to awake from slumber), they have one thing

in common: all of them, in one way or another, have to do with night and

the vague, uncertain, and ambivalent experiences associated with it. This, of

course, is no coincidence: in setting these poems to music, Hensel uses equiv-

ocal endings to evoke equivocal perceptions and emotions; in each case, the

music’s inability to confidently close is a metaphor for the poetic speaker’s

inability to confidently hear, see, and act in the world of night and dreams.

“Zu deines Lagers Füßen”

“Zu deines Lagers Füßen” is one of six songs that Hensel set to poems by her

husband Wilhelm, who was a talented poet and artist. Both the poem and the132 Stephen Rodgers

song were written in the year of their marriage 1829. It is fitting, then, that the

theme is courtship; a lover, separated physically from his beloved, dreams of

walking to her bed at night and greeting her. (I treat the poetic speaker as a

man and his beloved as a woman because of the biographical context—this is

clearly Wilhelm speaking to Fanny.) In this nocturnal scene he sends peace

and comfort to her from afar, transmitting a song from his soul into hers and

receiving a sense of peace from her in return:

Zu deines Lagers Füßen To the foot of your bed

Tret’ ich im Sehnsuchtstraum, I walk in a dream filled with yearning,

Dich heimlich zu begrüßen In order to secretly greet you

Im fernen, fremden Raum. In a distant, strange space.

Will Trost und Lindrung bringen I shall bring comfort and relief

In Wunden und Gefahr In times of pain and danger,

Und meine Seele singen And sing my soul

In deine Seele gar. Utterly into yours.

O weht7 aus meinem Liede Oh out of my song wafts

Dich linde Ruhe an, Sweet calm over to you,

Und mir ein seel’ger Friede And a blessed peace

Von dir herüber dann. Then from you toward me.8

Hensel sets the poem’s three stanzas in modified strophic form (the first

two strophes are identical, and the last is slightly varied). Example 8.1

shows the first strophe not as Hensel composed it, but as I have recomposed

it. In this hypothetical version I have placed clear cadences at the end of each

phrase: a half cadence (HC) in m. 4, capping off the antecedent, and a perfect

authentic cadence (PAC) in m. 8, closing the consequent.

Now compare Example 8.1 with Example 8.2 , which shows what

Hensel actually wrote. (This example shows the entire song; I discuss the

final strophe further on.) Notice how she weakens the sense of closure at the

end of each phrase. In m. 4 the music pushes onward rather than resting,

since we hear not a D-major chord but a D-minor chord, which is quickly

transformed into a viio6/iv. This is an antecedent phrase that ends without a

true cadence; there’s a blurred boundary between the two halves of the pe-

riod. Hensel also weakens the ending of the consequent phrase. The piano

comes to rest after the singer arrives on the word “Raum” (“room”): rather

than a V7–i progression in G minor, we hear V7–I in E♭ major. We can think ofPlagal Cadences in Fanny Hensel’s Songs 133 this as a kind of evaded G-minor cadence, which defers a true cadence until later—yet when that cadence finally arrives, it is of course a plagal cadence (PC), not an authentic one. In fact, there’s not a single authentic cadence in the song. The sense of deferral is particularly strong because the evaded G- minor PAC is itself displaced from where it might have been. In mm. 6 and 7 Hensel stretches the words “fernen” (“distant”) and “fremden” (“strange”) so that they each fill an entire measure rather than a half measure. The music slows as it approaches what promises to be a PAC, veers unexpectedly away from that PAC, and finally makes a soft landing on a plagal cadence. The haziness of the song’s formal boundaries reflects both the meaning and the structure of the opening stanza. The blurred edges of the antecedent and consequent phrases conjure the haziness of the dreamy, night-time scene; in softening the moments of closure at the end of each phrase, Hensel finds a musical analogue for the dimness of the intimate, nocturnal setting that Wilhelm Hensel so beautifully evokes in his poem. The blurred edges also re- late to a syntactical, not just semantic, aspect of the stanza. The first two coup- lets are syntactically dependent upon one another, in that the second couplet tells us why the poetic speaker dreams of walking to the foot of his beloved’s bed. Borrowing from Yonatan Malin, who writes in Chapter 10 of the present volume about how Hensel responds musically to various kinds of couplets, we could say that the second couplet is a “continuation” of the first. True, the second line of the poem is end-stopped, and the couplet could certainly have finished with a period, marking the close of a complete thought. But lines three and four provide crucial context for understanding the driving force behind this curious “Sehnsuchtstraum” (“dream filled with yearning”), the reason for this imagined tryst; together, they convey action and motivation, and seem fused into a whole. In the same way, the two phrases of the pe- riod are fused together by the non-cadence between them. The consequent is the musical equivalent of a dependent clause, but it is a clause that continues smoothly from the declarative statement that precedes it. The expansion of the consequent phrase is equally expressive. The word- stretching in mm. 6 and 7 (especially on the word “fernen”) underlines the distance between the lovers. When I sing “fernen” and “fremden”—with their drawn-out dotted half notes, which sound all that much longer when juxta- posed with the piano’s moving quarters, and their soft initial consonants and open eh vowels, which contrast with the more percussive and closed sounds of the previous word “begrüßen”—I can practically see the poetic speaker extending his arms to his beloved, reaching out to her in an imagined em- brace. The phrase expansion enacts this physical (and emotional) gesture of

134 Stephen Rodgers reaching out, and reinforces the fact that the lovers are separated physically, if not psychically. The separation of melodic and harmonic closure likewise emphasizes this sense of physical separation. We might imagine the piano accompaniment as the beloved and the vocal melody as the poetic persona, who longs to be physically close to her but can only imagine that proximity in a “dream filled with yearning.” We might even think of the piano accompa- niment as Fanny and the vocal melody as Wilhelm, dreaming of the kind of intimacy that they will be able to enjoy after they are married. The second strophe of the song is identical to the first. It would be easy to conclude therefore that the relationships between music and poetry that we have seen in the first strophe do not really obtain for the second. Yet, as with so many of Hensel’s strophic songs, she tailors the music not just to the opening stanza of the poem, but also to subsequent stanzas; we feel resonances between musical and textual details throughout the song. The fused antecedent and consequent are even more appropriate in this stanza, since there is an enjambment between the third and fourth lines of the stanza (“Will Trost und Lindrung bringen / In Wunden und Gefahr / Und meine Seele singen / In deine Seele gar” [“I shall bring comfort and relief in times of pain and danger”]). In the context of the second strophe, the stretching of the consequent phrase and the protracted descent from the high G evoke not so much the distance separating the lovers as the song that the speaker sings across that distance; if this passage in the first strophe suggests arms stretched out, here it suggests music poured out. For this reason, I tend to sing this line louder and with more vibrato than the comparable line in stanza 1— “Dich heimlich zu begrüßen / Im fernen, fremden Raum” (“in order to se- cretly greet you in a distant, strange space”)—which I think requires a more hushed, and even straight-tone, delivery. Still, even more striking than the text-music resonances in the second strophe are those in the final strophe (see mm. 11ff. of Example 8.2 ). It is here that the most significant strophic modification happens, and the most peculiar cadential evasion. In place of the E♭-major chord that we heard on the word “Raum” (in m. 9) Hensel substitutes a V56/iv (in m. 19)—in essence, the evaded cadence gets evaded. As a result, the melodic close (on the word “dann”) seems especially unmoored, detached from the harmony beneath it. Singing this line, I somehow feel that the piano is drifting even further from me, pulling away with a faintly stronger force, because of the prolonged secondary dominant that demands resolution. This faint force propels the accompaniment onward, so that it comes to rest a measure later than before. (The consequent phrase of

Plagal Cadences in Fanny Hensel’s Songs 135

the third strophe is seven bars long, not six, as in the previous two strophes.)

The last stanza reads, “O weht aus meinem Liebe / Dich linde Ruhe an, / Und

mir ein seel’ger Friede / Von dir herüber dann” (“Oh out of my song wafts

sweet calm over to you, and a blessed peace then from you toward me”). “Linde

Ruhe” (“sweet calm”) and “seel’ger Friede” (“blessed peace”) arrive, as the voice

and the piano’s left hand conjoin on the tonic pitch in the final measure and

the plagal cadence now takes on conventional religious connotations, as if

responding to the words “seel’ger Friede.” We finally experience the union of

voice and piano, these musical embodiments of Wilhelm and Fanny, and the

union is all the more satisfying because we’ve had to wait for it.

“Bitte”

I turn now to an even more radical example of musical closure. If in “Zu deines

Lagers Füßen” Hensel softens the edges of phrases, in “Bitte” (composed in

August 1846, nine months before her death), she smears them, letting the

tonal colors bleed into one another. This is true not only of the final plagal

cadence, which in this song is suffused with chromaticism, both leading up

to the cadence and following it; it is also true of the cadences (or would-be

cadences) in the “body” of the song, which are veiled in ambiguity and uncer-

tainty. Indeed, the entire song is ambiguous, in that it is hard to tell whether

it is in a major or minor key. The key signature says A♭ major, but our ears tell

us otherwise: Hensel makes such liberal use of mixture that one might argue

that more of the song is in A♭ minor than in A♭ major. Imagine A♭ major and

A♭ minor as two colors, say red and blue. Hensel’s song doesn’t juxtapose these

colors, alternating between them; she blurs them together, so that the entire

song takes on a purple hue.

The poem—by Nikolaus Lenau—is, in a sense, about actual blurred

colors, and blurred experiences. It is a poem in praise of night and the

“Zauberdunkel” (literally, “magic darkness”) that takes the daylight world

away from the poetic speaker, enshrouding him in dreams (I likewise treat

the poetic speaker as a man, mainly for the sake of consistency):

Weil auf mir, du dunkles Auge, Linger on me, you eye of darkness,

Übe deine ganze Macht, Exercise your power in full,

Ernste, milde, träumereiche, Solemn, mild, dream-laden,

Unergründlich, süße Nacht! Unfathomably sweet night!136 Stephen Rodgers

Nimm mit deinem Zauberdunkel With the magic of your darkness

Diese Welt von hinnen mir, Take this world away from me,

Daß du über meinem Leben So that you hover over my life

Einsam schwebest für und für. All alone, forever and ever.9

As with “Zu deines Lagers Füßen,” we can learn a lot about the effectiveness

of Hensel’s song by imagining a less conventional setting of the text. Example

8.3 shows how the song would look if it were fully in the major mode, and

if its cadences were clear and unambiguous. We might describe this version

as closed and bright—closed in the sense that the song’s phrases lead to well-

defined cadences, and bright in the sense that the minor mode does not in-

trude at all. Note especially the HC in m. 5, the imperfect authentic cadence

(IAC) in F minor in m. 9, and the PAC in m. 16. The only other cadence in

the song—the deceptive cadence (DC) in m. 13—is not technically a cadence

at all, since it defers true cadential closure down the road. But it is entirely

normative, and entirely diatonic—which, as we shall see, is not the case in

Hensel’s setting.

Indeed, very little is normative and diatonic in Hensel’s song, which

appears in Example 8.4 . If my hypothetical version is closed and bright,

her actual version is open and dark, or at least darker—open in the sense that

so many of the song’s phrases sound open-ended because they do not close

with cadences, and dark in the sense that the dark-blue, nocturnal hues of

A♭ minor practically overtake the song. (Scott Burnham, in his discussion of

this song in Chapter 3, aptly notes that it “seems to create its own haunting

tonal language.”) The clear-cut cadences of Example 8.3 are either weak-

ened or avoided altogether. The HC in m. 5 is dissolved by the turn from

an E♭-major chord to an E♭-minor chord, an “ernste” (“solemn”) and “milde”

(“mild”) harmonic transformation that perfectly matches the words. Even

more astonishing, the IAC in F minor in m. 9 of my recomposition becomes

an evaded cadence (EC) in F♭ minor—the music not only plunges into a

flatside key (♭VI) but also obscures this key because F♭ major is more im-

plied than asserted. The tonal maneuver sounds as “träumereich” (“dream-

laden”) and “unergründlich” (“unfathomable”) as the “süße Nacht” (“sweet

night”) that envelops the speaker. The DC in m. 13 of my recomposition re-

mains in Hensel’s version, but here too F♭ major (as a chord, not a key) colors

the passage, pulling us fully into the minor mode. Finally, and most strik-

ingly, instead of a PAC in m. 16, Hensel writes a diminished plagal cadence

(viio43—I); the bass E♭ of the cadential 46 chord sinks to D♭, and the melodyPlagal Cadences in Fanny Hensel’s Songs 137

droops with it, falling to 5̂ (E♭). A blanket of darkness covers everything in

this song, pressing gently downward: diatonic pitches move flatward, melo-

dies and bass lines fall.

One of the reasons the final cadence sounds so appropriate for all its

oddity, so “right” in spite of its unconventionality, is that it encapsulates

so much of what precedes it. The 8̂–♭7̂–♭6̂–5̂ melodic descent in mm. 15–16

fills in the space between A♭ and E♭ with the first two chromatic pitches

heard in the vocal melody—the F♭ in m. 2 on the word “dunkles,” or “dark”

(which is followed by its enharmonic equivalent E♮ a measure later), and

the G♭ on “ernstes” (“solemn”)—fusing these two borrowed tones into a

single melodic gesture. The melody associated with the plagal cadence

also responds to a similarly chromaticized melody associated with the

earlier evaded cadence in F♭ major: namely, the descending gesture on

“unergründlich süße Nacht” in mm. 7–9 (F♭–E♭–D♭–C–B♭♭). (That both

melodies are set to the same words underlines the connection; so does

the fact that the music after the plagal cadence features the characteristic

B♭♭–A♭ motion from mm. 8–9.) Even the bass line of the plagal cadence

grows out of earlier material: the F♭–E♭–D♭ octaves in mm. 14–15 echo the

same notes from m. 13. This particular plagal cadence, realized in this par-

ticular way, becomes a metonym for the “dream-abundant” tonality that

pervades the song.

Still, as strange as the song’s tonal language may be, it is not an unsettling

strangeness; it is a strangeness that the poetic speaker relishes, an experi-

ence of unfathomable, mysterious beauty that the speaker does not want

to end. We hear this as much in the avoidance of strong cadential closure

as in the repetition of text: “Ernste, milde, träumereiche, / Unergründlich

süße Nacht, / Ernste, milde, träumereiche, / Unergründlich süße Nacht, /

Unergründlich süße Nacht.” We also hear it in the fact that not once does the

last, crucial word of the poem (“Nacht,” the very thing the poetic speaker

cannot let go of) fall on a clear cadence. The song’s phrases don’t so much

end as dissolve. They linger, as the night does.

“Erwache Knab’ ”

“Erwache Knab’ ” makes for a fitting final example since, like “Bitte,” Hensel

wrote it in the last year of her life (just two months before “Bitte,” in June

1846), and, like “Zu deines Lagers Füßen,” it is a setting of a poem by her138 Stephen Rodgers husband. The poem and the song were presumably given as a birthday gift to the Hensel’s son Sebastian, who was about to turn sixteen.10 The text is a mere two lines, a rhyming couplet that urges the “Knab’ ” (“lad”) to awake from “Kindheit Traum” (“childhood’s dream”), lest he miss all that life has to offer: Erwache Knab’, erwache nun aus Awake, lad, awake now from childhood’s der Kindheit Traum, dream; Der Späte nicht und Schwache Not he who is tardy and not he who is durchmißt der Erden Raum. weak strides through the earth’s realm.11 For all its brevity, though, the poem is rich with expressive details, both structural and semantic, a sign that Wilhelm Hensel was no dabbling ama- teur but a writer in full control of his craft. Notice the internal rhyme that links the first half of each line (“Erwache Knab’, erwache . . . / Der Späte nicht und Schwache . . .”), which prevents the long hexameter lines (with six poetic stresses) from sounding too monotonous. The comma in the middle of line 1 is also a beautiful touch; combined with the repetition of the word “erwache,” it makes the first line sound like a call to attention. It also creates a striking contrast with the second line. If line 1, with its pause and its repeated im- perative, begins with two arresting drumbeats (“Awake, lad, awake!”), line 2 barrels ahead. There is no caesura in this line, nor any word repetitions; it charges onward, doing rhythmically what the speaker wants the lad to do physically: move, don’t delay, get on with it. Semantically, the poem is also more complex than it first seems. On the face of it, this might read like a simple imperative to get up, to not sleep away the day because there’s much to do, but the wonderful phrase “Kindheit Traum” adds another layer of meaning. On first encountering the poem, I read this line as “Awake, lad, awake now from your childhood dream,” thinking that this referred to the child’s actual dream, the night-time rev- erie from which he must awake. Later, after a conversation with Harald and Sharon Krebs, I came to see that “Kindheit Traum” also means something more metaphorical, not just an actual dream but also a dream world, the blissful, uncomplicated, sheltered world of childhood itself: not just “your childhood dream,” but also “childhood’s dream.” In this light, the imperative “awake!” sounds at once forceful—“It’s time to get out of bed and get on with your day!”—and also tender—“It’s time to leave the idyllic realm of child- hood and experience the world as an adult.” Remember that the poem and

Plagal Cadences in Fanny Hensel’s Songs 139 the song were a gift to the Hensel’s sixteen-year-old son Sebastian, poised at the threshold of adulthood, ready to “stride through the earth’s realm,” with all its joys and its trials. Hensel’s musical setting, shown in Example 8.5 , beautifully captures this mixture of forcefulness and tenderness. The song begins energetically. The tempo is Allegro, the key is a bright D major, the dynamic is forte, the left hand of the accompaniment moves in striding quarter notes and the right hand in propulsive eighths, and the vocal melody begins with a leap of a sixth—a musical emblem of awakening. Yet the opening is not as forceful as it might have been, mostly because of what Hensel does harmonically. The song begins not with a root-position tonic but with a first-inversion tonic—the bass slides downward (F♯–E–D), approaching the tonic pitch surreptitiously. Instead of being illuminated brightly, it is only partly lit, emerging gradually, like the daylight that awakens the lad. Hensel makes this descending bass line the stuff of the song, outlining a continuous stepwise descent from the opening F♯ down to the A♯ on the downbeat of m. 6 and then, after hovering around B, continuing downward from there, all the way to the D♯ in m. 10. (See the circled pitches in the ex- ample.)12 It is this continuously descending bass line that enables her to end the opening phrase of the song with an unexpected F♯-major chord (m. 9). I say “unexpected” because another composer might have opted for a more conventional A-major chord, ending the phrase with a half cadence in D major rather than smudging the phrase ending with a secondary dominant. (As with “Zu deines Lagers Füßen” and “Bitte,” Hensel avoids hard-edged phrase endings in this song.) Another composer might also have chosen to state the tonic more emphatically at the very beginning, approaching it head- on rather than sideways. Example 8.6 shows a recomposition of the first phrase, which states the tonic more forcefully and rounds things off with a half cadence. My recomposition sounds far more commanding than Hensel’s actual version. Sticking for the moment with a more literal reading of the poem (as a call to get out of bed), this version has the effect of a sudden and loud alarm. Hensel’s version, for all its vigor and energy, sounds more en- ticing than commanding, like an alarm that starts softly and gradually gets louder. Her setting still says “wake up,” but it does so with a gentler tone. The same is true of the song’s ending. After repeating the second line of the poem, Hensel returns, in m. 14, to the opening line and then repeats this line once more to bring the vocal melody to a close. All this text repetition begets not so much surety and strength, however—with so many repeated cadences

140 Stephen Rodgers that hammer home the message—as warmth and tenderness, even a measure of reluctance. It is as though Fanny and Wilhelm do not want to lean too heavily on their sixteen-year-old son, as though they know he must face the adult world, must let go of “childhood’s dream,” but also that it cannot happen in an instant. Better, then, to coax him, rather than drag him, into that daylight world. Cadential avoidance, not cadential articulation, is the name of the game here. As in the opening phrase of the song, Hensel again uses an unexpected F♯-major chord to avoid a clear cadence.13 Measure 17 could well have been an IAC, but she evades that cadence with a chromatic bass line—which, in- terestingly, moves upward by step (see the circled pitches); this passage may reverse the direction of the plunging bass line from the opening of the song, but it still uses bass-line linearity to steer clear of a cadence, and with the same characteristic F♯ harmony. After this evaded cadence, we hear the opening line a final time—one final imperative, “erwache Knab’,” which climbs to the highest note of the song, the G on “Kindheit” in m. 21. Here, though, where the expectation for an authentic cadence is at its highest, the floor seems to drop out. A cadential 46 chord arrives on the downbeat of m. 20, but no root-position V chord follows it; instead, the harmonies droop downward through V42/IV to IV6 and then, with a sudden downward leap in the vocal melody and the piano’s right and left hands, to IV. The bass sinks even fur- ther to D, and although the piano’s right hand moves upward to 1̂, the vocal melody settles on 5̂, as if it has expended all of its energy on the high G. What could have been a decisive authentic cadence becomes a far gentler plagal ca- dence, a softer tonic landing. For comparison, imagine if the song had ended with an IAC in m. 17 and a PAC in m. 22 (Example 8.7 ). What this version gains in strength it loses in subtlety. While it offers a more vigorous (even a more crowd-pleasing) rendi- tion of the words “awake, lad, awake from childhood’s dream,” it is a bit one- sided, less sensitive to the complexity, even the ambivalence, of the emotions behind these words. (Sensing this ambivalence, I prefer a performance of the song that is not too forceful—that emphasizes not just the bursts of energy but, even more, the moments where the energy wanes.) This is one of Hensel’s greatest talents as a songwriter: her ability to use the simplest musical means (a well-placed inversion, an avoided cadence, a bass line that moves in steps precisely where we expect leaps, a cadential melody that avoids 1̂) to illumi- nate the most complex feelings—like the paradoxical feeling of wanting your child to become an adult and also wishing he could stay young a little longer.

Plagal Cadences in Fanny Hensel’s Songs 141

Conclusion

In Hensel’s songs the plagal cadence was a real cadence, an important articu-

lator of formal closure that in certain contexts could carry as much structural

weight as an authentic cadence. At the same time, these plagal cadences carried

great emotional weight. For Hensel, deciding to end a song with a plagal ca-

dence instead of an authentic cadence, and deciding how exactly to pull off such

a maneuver, was no small choice; it had profound expressive consequences,

fundamentally shaping how listeners grasped the overall arc and affect of a

song, and likely shaping how performers interpreted the song as well.

Yet there are other ways to make sense of these plagal cadences, ways

that go beyond the specific contexts of the songs themselves, beyond the

individual text-music connections that make these songs and their pecu-

liar endings so affecting. Let me close by suggesting two additional ways of

thinking about Hensel’s plagal cadences that might open up new avenues for

exploring her innovative approach to musical closure.

The first approach relates to her musical influences—in particular, her

lifelong interest in J. S. Bach’s music, where real plagal cadences of the kind

described in this chapter are far more common than in the music of Hensel’s

contemporaries (though hardly ubiquitous). Bach was central to Hensel’s

(and her brother’s) life from their earliest years through to the very end. The

compositional training that she received from Carl Friedrich Zelter was

based heavily on the treatises of Bach’s student, Johann Kirnberger, and it

included exercises in figured bass, chorale harmonization, invertible coun-

terpoint, canon, and fugue. In her essay in this volume on Hensel’s songs of

travel (Chapter 4), Susan Wollenberg suggests that the characteristic tonal

wanderings in Hensel’s songs might have been influenced by the “surprising

direction taken by the chorale phrases in Bach’s [chorale] harmonizations.”

Could the characteristic plagal cadences in her songs likewise have some-

thing to do with her immersion in Bach chorales? His chorales based on

Phrygian and Mixolydian melodies, for example, occasionally end with

plagal cadences, since the melodies lack the 2̂ and 7̂ that form part of a dom-

inant triad.14 It is notable in this context that two of the songs I discussed

in this chapter have quasi-Phrygian melodies: each strophe of “Zu deines

Lagers Füßen” ends B♭–A♭–G (3̂–♭2̂–1̂), and “Bitte” ends A♭–G♭–F♭–E♭ (8̂–♭7̂–

♭6̂–5̂ in the key of A♭ major but suggestive of a descent to an E♭ Phrygian final).

And what of Hensel’s intimate familiarity with the Well-Tempered

Clavier, whose twenty-four preludes she performed for her father—from142 Stephen Rodgers memory—when she was only thirteen years old? I think, for example, of the ending of Bach’s Prelude in E major, from book 1. The melodic arrival on E coincides with a deceptive cadence, and beneath this sustained E the final harmonies go vi–V56/IV–IV–viio43–I. Considering Hensel’s lifelong im- mersion in this repertoire, it hardly comes as a surprise that at the age of nineteen, when composing “An die Entfernte,” or twenty-three years later, when writing “Bitte,” she drew upon a similar cadential progression (viio43–I); progressions like this had been in her ears, and in her fingers, since she was a child. Paradoxically, then, Hensel’s plagal cadences may point forward to the real plagal cadences that appear more frequently in late Romantic music than in music from the first quarter of the nineteenth century, and also backward to the closing strategies she absorbed from her Baroque forefather. A second way of approaching Hensel’s fascination with plagal cadences has to do with her novel handling of closure more generally. Plagal cadences, after all, are not the only means by which she weakens closure in her songs. In Chapter 7 of the present volume, Tyler Osborne writes about a song that sounds for all intents and purposes as though it ends on the dominant of the subdominant (“Die Äolsharfe auf dem Schlosse zu Baden”). Jürgen Thym, in Chapter 11, analyzes a song that ends on the dominant of the tonic (“Verlust”). And Osborne and I have explored Hensel songs that end without a cadence at all—neither authentic, nor plagal—but instead with what William Caplin has called “prolongational closure,” progressions like viio7–I, V56–I, or V43–I.15 Again and again in her music—and above all in the realm of song, that lab- oratory where she undertook her most adventurous musical experiments— Hensel employed stunningly original strategies to defer, smudge, attenuate, undermine, or altogether avoid expected moments of cadential closure, so that the only real musical punctuation marks come late in the game, if they come at all. I would go so far as to argue that her experiments with musical closure are as original as Robert Schumann’s, a composer who is justifiably famous for the “open endings” of his songs.16 I say this not least because she was challenging the orthodoxy of the authentic-cadential ending as early as the 1820s, whereas Schumann’s most unorthodox song endings appear in his later works, written after about 1850.17 This is yet another reason why Fanny Hensel’s once-marginalized songs deserve a central place in discussions about the aesthetics of nineteenth-century music. As music theorists and musicologists continue to explore the ways that Romantic composers modify the conventions of their Classical predecessors, and as they develop better

Plagal Cadences in Fanny Hensel’s Songs 143

tools to account for the idiosyncrasies of Romantic form more generally, they

would be wise to have her songs close at hand.

Notes

1. William E. Caplin, Classical Form: A Theory of Formal Functions for the Instrumental

Music of Haydn, Mozart, and Beethoven (New York: Oxford University Press, 1998), 75.

2. William E. Caplin, “Cadence in the Mid- to Late-Nineteenth Century,” chap. 9 of

Cadence: A Study of Closure in Tonal Music (New York: Oxford University Press,

forthcoming). Caplin makes a similar point in his article on the cadence in Classical-

era music: “It is perhaps possible to speak of plagal cadences in some nineteenth-

century works, but even there, it is probably better to understand such situations

as deviations from the classical cadence, whereby the rhetoric of the cadence may

be present, despite the absence of a genuine cadential progression” (“The Classical

Cadence: Conceptions and Misconceptions,” Journal of the American Musicological

Society 57, no. 1 [Spring 2004]: 72, note 64). To be fair, not everyone agrees with Caplin

on this point. Daniel Harrison, for example, argues that by treating the plagal ca-

dence as essentially non-cadential, Caplin presents an overly “particularist” theory of

cadences, one that regards late eighteenth-century style as the high point of musical

composition and the norm for functional tonal music writ large: “Caplin’s relegation

of the plagal cadence to the status of ‘myth’ . . . may be excused by its limited functional

uses in the Classical style, but which is a bald overstatement if the practices of pre-

vious and subsequent repertories are taken into account” (“Cadence,” in The Oxford

Handbook of Critical Concepts in Music Theory, ed. Alexander Rehding and Steven

Rings [New York: Oxford University Press, 2015], 20).

3. By “bona fide plagal cadence” I mean a plagal cadence that falls at the end of a formal

unit, as opposed to coming after the end of a formal unit. Here I follow Caplin, who

writes in Cadence: A Study of Closure in Tonal Music, “As we reach the middle of

the nineteenth century, we finally can recognize a small number of genuine plagal

cadences, ones that satisfy the conditions (1) that the arrival on tonic seems truly to

represent the moment of formal closure for a thematic unit and (2) that the penulti-

mate harmony is subdominant, not dominant” (forthcoming).

4. Interestingly, bona fide plagal cadences are much less common in her instrumental

music—in part because her instrumental works are generally longer than her songs

and, perhaps, because she felt that the conclusion of a longer piece required a cadence

that was syntactically stronger than a plagal cadence. For two examples of instrumental

works that end with genuine plagal cadences, see her unpublished Allegro moderato

assai in A minor, H-U 405 (1844), in which an emphatic cadential 46 is followed by

iv–iiø56 –I (in mm. 54–55), and another unpublished piano piece, the early Andante con

espressione in C minor, H-U 181 (1826), in which (remarkably) the structural cadence

features a first-inversion D♭7 chord (spelled with a B♮) leading to C major: 41 in the144 Stephen Rodgers

bass, in other words, but not iv–I in the harmony. I thank Tyler Osborne for drawing

these pieces to my attention.

5. To be sure, Hensel is not the only composer from the first half of the nineteenth cen-

tury to have ended her pieces with plagal cadences; a number of Schumann’s later

songs contain structural plagal cadences, often of the “diminished-plagal” variety—

see, for example, Op. 83, Nos. 2 and 3 (“Die Blume der Ergebung” and “Einsiedler”);

Op. 89, Nos. 1 and 4 (“Es stürmet am Abendhimmel” and “Röselein, Röselein!”); and

Op. 107, No. 2 (“Die Fensterscheibe”). But she is one of the earliest composers to have

done so, and she uses this technique more than any other early nineteenth-century

composer that I can think of.

6. Specific information about the published editions of Hensel’s songs can be found in the

bibliography to this book. Readers interested in searching the digital collection of the

Staatsbibiothek zu Berlin (which contains a growing number of Hensel manuscripts)

can find the collection at https://digital-beta.staatsbibliothek-berlin.de/.

7. The version of this song published by Furore lists this word as “ruft” (“calls”), but a

close examination of the original manuscript of the song suggests that the word is

most likely “weht” (“wafts”). I thank Harald Krebs for pointing this out to me. For the

published version of the song, see Cornelia Bartsch and Cordula Heymann-Wentzel,

eds., Fanny Hensel: Lieder ohne Namen (1820–1844), (Kassel: Furore, 2003), vol. 2,

18–19. The manuscript can be found in the Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin, MA Depos.

Lohs 2, 36.

8. The translation is my own. Special thanks to Harald and Sharon Krebs for help with

some trickier passages.

9. I draw my translation from Scott Burnham’s translation of this poem in Chapter 3.

10. See R. Larry Todd, Fanny Hensel: The Other Mendelssohn (New York: Oxford

University Press, 2010), 327.

11. The translation is by Sharon Krebs.

12. This sort of bass line resembles similar descending bass lines that Julie Pedneault-

Deslauriers has found in the music of Clara Schumann. See her article “Bass-Line

Melodies and Form in Four Piano and Chamber Works by Clara Wieck-Schumann,”

Music Theory Spectrum 38, no. 2 (Fall 2016): 133–54.

13. In his life-and-works study of Hensel, R. Larry Todd includes a few lines about

“Erwache Knab’ ” and comments specifically on Hensel’s tonicization of B minor

with these F♯ chords. The song, he writes, “plays upon tonal ambiguity between D

major and B minor, with the major mode associated with childhood dreams, and the

latter with earthly realities, before resolving the issue in favor of the major” (Fanny

Hensel: The Other Mendelssohn, 327).

14. See Lori Burns, Bach’s Modal Chorales (Stuyvesant, NY: Pendragon, 1995).

15. “Prolongational Closure in the Lieder of Fanny Hensel,” Music Theory Online 25,

no. 3 (September 2020). See William E. Caplin, “Beyond the Classical Cadence:

Thematic Closure in Early Romantic Music,” Music Theory Spectrum 40, no. 1 (Spring

2018): 14–16.

16. See David Ferris, Schumann’s Eichendorff Liederkreis and the Genre of the Romantic

Cycle (New York: Oxford University Press, 2000), 106–9.Plagal Cadences in Fanny Hensel’s Songs 145

17. To choose one representative example, consider the fact that four of the seven songs

from Schumann’s Sechs Gedichte von Lenau und Requiem, Op. 90 (1850), end without

authentic cadences: No. 3 (“Kommen und Scheiden”) ends with V56–I; No. 4 (“Die

Sennin”) begins in B major but ends with a plagal cadence in D♯ major; No. 6 (“Der

schwere Abend”) ends with V43–i; and No. 7 (“Requiem”) ends with a cadential 46 that

fails to resolve to a dominant but is instead followed by a tonic pedal, above which

we hear the progression viiø7/V–V7–I. Schumann’s earlier songs do on rare occasions

end without authentic cadences: “Im wunderschönen Monat Mai,” which ends on

a dominant seventh, is of course the most famous example, but “Mondnacht,” from

his Liederkreis, Op. 39, is another; there, the vocal melody lands on ^1 (in m. 59),

but the underlying harmonies evade an authentic cadence, instead going V42–V56/IV–

IV–I. Still, the frequency of these unorthodox endings is far greater in Schumann’s

later songs.You can also read