Visitors' willingness to pay for snow leopard Panthera uncia conservation in the Annapurna Conservation Area, Nepal

←

→

Page content transcription

If your browser does not render page correctly, please read the page content below

Visitors’ willingness to pay for snow leopard

Panthera uncia conservation in the Annapurna

Conservation Area, Nepal

M A U R I C E G . S C H U T G E N S , J O N A T H A N H . H A N S O N , N A B I N B A R A L and S O M B . A L E

Abstract The Vulnerable snow leopard Panthera uncia ex- Introduction

periences persecution across its habitat in Central Asia, par-

ticularly from herders because of livestock losses. Given the

popularity of snow leopards worldwide, transferring some T he conservation of large carnivores is difficult and costly

(Linnell et al., ; Nelson, ; Dickman et al., ),

and many have experienced significant global declines in

of the value attributed by the international community to

these predators may secure funds and support for their con- range and population size (Ripple et al., ). With an

servation. We administered contingent valuation surveys to estimated global population of ,–, individuals

international visitors to the Annapurna Conservation (McCarthy & Chapron, ; Snow Leopard Working

Area, Nepal, between May and June , to determine Secretariat, ) spread across a range of over . million km

their willingness to pay a fee to support the implementation in countries of south and central Asia (Jackson et al.,

of a Snow Leopard Conservation Action Plan. Of the % of ), snow leopards Panthera uncia have recently been re-

visitors who stated they would pay a snow leopard conser- categorized as Vulnerable on the IUCN Red List (McCarthy

vation fee in addition to the existing entry fee, the mean et al., ), suggesting that they are facing a high risk of ex-

amount that they were willing to pay was USD per trip. tinction in the wild in the medium-term future. Nepal is

The logit regression model showed that the bid amount, the home to c. – snow leopards, most of which inhabit

level of support for implementing the Action Plan, and the the country’s western regions, including the Annapurna

number of days spent in the Conservation Area were signifi- Conservation Area (Jackson & Ahlborn, ; Ale et al.,

cant predictors of visitors’ willingness to pay. The main rea- ; DNPWC, ).

sons stated by visitors for their willingness to pay were a Threats to snow leopards in Nepal include prey reduction

desire to protect the environment and an affordable fee. A because of illegal hunting, retribution for livestock depreda-

major reason for visitors’ unwillingness to pay was that tion, climate change, habitat degradation, wildlife crime

the proposed conservation fee was too expensive for them. and, more recently, Cordyceps fungus collection in alpine ha-

This study represents the first application of economic valu- bitats. The fungi are believed to have aphrodisiac properties

ation to snow leopards, and is relevant to the conservation of and can present a considerable source of income, but their in-

threatened species in the Annapurna Conservation Area tensive and unregulated harvesting contributes to the degrad-

and elsewhere. ation of the fragile ecosystem (Jackson et al., ; DNPWC,

). All of these potential threats are present to varying de-

Keywords Carnivore conservation, contingent valuation, grees in Nepal’s high altitude protected areas. Conflicts with

economic valuation, existence value, Panthera uncia, snow local communities over livestock losses to snow leopards may

leopard, threatened species, wildlife policy be the most serious threat in the Annapurna Conservation

Supplementary material for this article is available at Area (Wegge et al., ; Ale et al., ), a situation often ag-

https://doi.org/./S gravated by relative poverty (Jackson et al., ). A major

component of Nepal’s strategy to conserve the snow leopard

and other mega-fauna has been the establishment and man-

agement of protected areas, an approach implemented global-

ly to conserve biodiversity and maintain ecosystem integrity

(Chape et al., ; Gaston et al., ). Although often con-

MAURICE G. SCHUTGENS (Corresponding author) Space for Giants, Nanyuki PO sidered effective for biodiversity conservation and poverty al-

Box 174, 10400, Kenya. E-mail mauriceschutgens@gmail.com

leviation at the broad scale (Bruner et al., ; Balmford et al.,

JONATHAN H. HANSON* Department of Geography, University of Cambridge,

Cambridge, UK

; Geldmann et al., ), the current protected areas ap-

proach may not adequately protect many threatened species

NABIN BARAL University of Washington, School of Environmental and Forest

Sciences, Seattle, WA, USA at the small scale (Brooks et al., ; Mora & Sale, ), es-

SOM B. ALE University of Illinois at Chicago, Biological Sciences, Chicago, IL,

pecially where funding is inadequate (Bruner et al., ) and

USA species have large range sizes (Jackson et al, ).

*Also at: Jubilee Farm CBS, Larne, UK Jackson et al. () identified increased funding as one

Received May . Revision requested July . potential solution for effective snow leopard conservation

Accepted October . First published online March . and conflict management in Nepal, and tourism has been

Oryx, 2019, 53(4), 633–642 © 2018 Fauna & Flora International doi:10.1017/S0030605317001636

Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. IP address: 46.4.80.155, on 02 Feb 2021 at 09:51:24, subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms.

https://doi.org/10.1017/S0030605317001636634 M. G. Schutgens et al.

proposed as a way to raise funds (DNPWC, ). Global largest protected area in the country, ranges over ,–

tourism, valued at over USD . trillion in , is one of , m and includes the world’s tenth highest peak,

the fastest growing industries in the world (World Annapurna I. It is also renowned for containing the world’s

Tourism Organization, ) and nature-based tourism is deepest valley and a large diversity of flora and fauna, sup-

an important component (Gössling, ; Tisdell & porting different types of forest, , plant species, and

Wilson, ). Although the tourism industry is subject to over species of mammals and species of birds

external pressures such as political instability, infectious dis- (ACAP, ). The Conservation Area is managed by an au-

eases, natural disasters and the uncertainties of the global tonomous non-governmental organization, the National

economy, nature-based tourism is increasingly in demand Trust for Nature Conservation, in partnership with local

(Emerton et al., ). Over a -year period, nature-based communities, through their Conservation Area Manage-

tourism, measured in the number of visitors to protected ment Committees. As per the census, the human popu-

areas, increased at a rate of % per annum in developing lation of , relies heavily on agro-pastoralism and

countries (Balmford et al., ). This demand presents tourism. Tourist entry fees constitute the main source of

an opportunity for protected areas to charge fees that reflect revenue for management. In over , international

the true value associated with their services as well as the tourists visited the Conservation Area (Baral & Dhungana,

threatened species within them (Laarman & Gregersen, ), attracted primarily by the Himalayan landscape, as

; Walpole et al., ). To do so effectively for the well as its ecological and cultural diversity (ACAP, ).

Annapurna Conservation Area, a study eliciting the value The world-famous Annapurna Circuit trekking route

of snow leopards to visitors is warranted. that circumnavigates the Annapurna massif within the

Snow leopards, like other threatened species, can elicit Conservation Area is one of the most popular trekking

both use and non-use values within the total economic routes in the country.

value framework. Use values are derived from consumptive The Annapurna Conservation Area has a population of

use of a resource, such as wildlife viewing or trophy hunting at least snow leopards (Ale et al., ). The most recent

(Loomis & White, ). For instance, in Hemis National estimates have suggested the presence of at least three adult

Park in India, photographic safaris based on snow leopards snow leopards in an area covering c. km within the

have been developed to generate necessary funds for their Conservation Area’s Mustang District (Ale et al., ).

conservation (Namgail et al., ). Non-use values, on A similar density was reported from Manang District’s

the other hand, are derived from appreciating that snow leo- Phu Valley (Wegge et al., ). These estimates represent

pards exist even if they will never be utilized, the existence a relatively high snow leopard density compared to other

value, and the value placed on knowing that snow leopards range countries (Jackson et al., ; Ale et al., ).

will be available for future generations, the so-called bequest Significant numbers of blue sheep Pseudois nayaur in and

value (Loomis & White, ). Both use and non-use values around the Annapurna massif are likely to constitute the

can be elicited through empirical research and used for the main source of food for this population of snow leopards

preservation of snow leopards (Loomis & White, ; (Ale et al., ).

Richardson & Loomis, ). Although it might be difficult

to value wildlife species accurately, an assessment of the

total economic value of the snow leopard has the potential Methods

to influence conservation policies.

In this paper, we assess international visitors’ willingness Sampling and data collection

to pay a fee for snow leopard conservation in the Annapurna

Conservation Area. We examine an array of visitors’ charac- During March and May we administered a written

teristics affecting their willingness to pay in Annapurna, questionnaire in Basic English to foreign tourists. The

which is visited by over , international trekkers an- Annapurna Circuit trekking route was followed in a clock-

nually (Baral & Dhungana, ). We outline the overall im- wise direction from Lower Mustang in the west to Manang

portance of this approach for the conservation of threatened in the east. Traveling the circuit in this direction meant we

species, particularly in the context of developing countries, encountered new tourists on a daily basis, as the majority of

and discuss policy implementations to ease financial pres- trekkers follow the circuit in an anti-clockwise direction. We

sure on the Conservation Area. used cluster sampling of hotels within villages along the

route to identify a random sample of visitors. We selected –

hotels randomly by lottery each day and approached tour-

Study Area ists staying in these hotels after obtaining permission from

the owners. Surveys were carried out in the evenings, when

The rugged Himalayan landscape of the , km tourists spent time relaxing or waiting for meals. We used

Annapurna Conservation Area in north-central Nepal, the questionnaires printed on a four-page booklet of laminated

Oryx, 2019, 53(4), 633–642 © 2018 Fauna & Flora International doi:10.1017/S0030605317001636

Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. IP address: 46.4.80.155, on 02 Feb 2021 at 09:51:24, subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms.

https://doi.org/10.1017/S0030605317001636Funding snow leopard conservation 635

A paper and added the relevant bid amounts in permanent individuals, q and q are the alternative levels of conserva-

marker before distribution to minimize the amount of paper tion practice (q being improved quality), X is a vector of

used. We shuffled the surveys before distribution to ensure a other characteristics, and ψ is a preference parameter. To

random distribution of bids. Prospective respondents were maximize utility, the individuals would make a trade-off be-

given a short briefing on the research project and then ver- tween income and conservation practice given their other

bal consent was taken if they showed interest in participat- characteristics. Individuals respond to the stated bid such

ing. We provided participants with markers to complete that:

their responses, which took . minutes on average

(SD = .; range = – minutes; n = ), and remained

nearby so that respondents were able to clarify any questions "Yes" if WTP . Bid

R=

with us. After entering the data, and before wiping out the "No" if WTP ≤ Bid

writing on the questionnaire sheet, we photographed all

questionnaires and catalogued them for future reference.

The questionnaires were cleaned and then re-used the fol- where R denotes the response, WTP is willingness to pay

lowing evening with the next set of random bids. Out of a and Bid is the stated conservation fee posed in the question

total of questionnaire completion requests, were re- asking about the visitors’ willingness to pay.

turned, giving a response rate of .%. Of the who gave Following the contingent valuation scenario (Supple-

their reason for not participating in the exercise .% stated mentary Material ), visitors were presented with a single

they were not interested in taking part, .% mentioned bound referendum-type question asking if they would be

language difficulties, .% were too tired, .% did not willing to pay a specific amount (USD A) as a conservation

have time, .% felt they did not know much about snow fee in addition to entry fees. One bid amount per question-

leopards, .% stated that there was no point in this type naire was randomly allocated from proposed conserva-

of research and .% were not allowed to write at that time tion fees: USD , , , , , , , , , , and

because of their religious practices. . These bid amounts were selected based on a literature

review of the contingent valuation of threatened species and

protected areas (Walpole et al., ; Bandara & Tisdell,

; Baral et al., ), supplemented by prior experience

Contingent valuation

of conducting similar studies elsewhere. Two debriefing

The contingent valuation method relies on surveys to esti- questions were also included. An open-ended follow-up

mate the value of environmental goods and services that question solicited the most important reason for visitors’ re-

are not traded in the conventional market (Arrow et al., sponse regarding their willingness to pay the specified

; Carson, ). By creating a hypothetical marketplace, amount. These qualitative responses were later coded and

people are asked to report their willingness to pay to obtain tallied.

or forgo a specified product or service, rather than inferring There is some criticism of the contingent valuation

it from observed behaviours in the regular market method concerning the reliability of results, potential biases

(Venkatachalam, ). The contingent valuation method and uncertainty of hypothetical markets (Venkatachalam,

has been used frequently to assess the willingness to pay ; Bartczak & Meyerhoff, ). Respondents may

of various types of stakeholders and for the protection of choose to state a lower willingness to pay if they are con-

threatened and charismatic species (Walpole et al., ; cerned that their responses may affect pricing policy, espe-

Bandara & Tisdell, ; Baral et al., a, b; Wilson & cially if they are likely to revisit the Conservation Area: the

Tisdell, ; Richardson & Loomis, ). The method ‘unrevealed motivation’ bias (Walpole et al., ). The re-

has, however, been used less frequently for large carnivores verse may also be true, with individuals wanting to demon-

(Lindsey et al., ; Richardson et al., ). strate their dedication to conservation. The strength of the

As the goal was to estimate the amount that visitors contingent valuation approach, however, is its ability to

would be willing to pay using a single bound dichotomous capture non-use values, describe the socio-demographic

question, we measured the compensating variation for the characteristics of the target stakeholders and present hypo-

improvement in conservation practice. Therefore, willing- thetical markets to estimate the value of the species in ques-

ness to pay was operationalized as the amount that must tion (Ressurreicao et al., ). Careful survey design is

be subtracted from people’s income to keep their utility con- crucial to minimize hypothetical biases and our design re-

stant: flected a real market scenario as closely as possible by choos-

ing the entry fee as a payment vehicle. Similar to Baral et al.

V1 (y − A, p, q1 ; X; c) = V0 (y, p, q0 ; X; c) (1) (), we also reported to respondents that the Annapurna

where V denotes the indirect utility function, y is income, A Conservation Area might re-assess pricing policy based on

is the bid amount, p is a vector of prices faced by the the survey’s results.

Oryx, 2019, 53(4), 633–642 © 2018 Fauna & Flora International doi:10.1017/S0030605317001636

Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. IP address: 46.4.80.155, on 02 Feb 2021 at 09:51:24, subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms.

https://doi.org/10.1017/S0030605317001636636 M. G. Schutgens et al.

Data analysis amount to implement the Action Plan. The probability

that a respondent would be willing to pay a given bid

We used logit regression to model the relationship between amount was assumed to follow a standard logistic variate

the dichotomous dependent variable (willingness to pay) (Hanemann, ):

and the independent variables. Ordinary least square regres-

′ −1

sion violates the normality assumption when the response Prob(Yes|A,X) = (1 + e−(a+bA+X F) ) (3)

variable is binary, so the logit model is most appropriate where α is a constant parameter, β is the coefficient of the

in such a case. Based on a review of other contingent valu- bid variable A, X is the vector of other explanatory variables

ation studies conducted in relation to protected areas (Baral influencing the response, and Φ is the vector of the corre-

et al., ; Baral & Dhungana, ) and threatened or cha- sponding slope parameters. Using estimated parameters of

rismatic species (Walpole et al., ; Bandara & Tisdell, equation (), the median amount that visitors were willing to

; Baral et al., a, b; Wilson & Tisdell, ; pay was computed as

Richardson et al., ), we hypothesized that respondents

who were offered lower bid amounts, had greater knowledge a+X ′F

WTP = (4)

of snow leopards, supported the implementation of b

the Snow Leopard Conservation Action Plan, were inter-

The mean amount was calculated by numerical integra-

ested in participating in nature-based activities in the

tion of the expected values of willingness to pay, from USD

Conservation Area, travelled in a larger group (Baral et al.,

. to the maximum bid amount of USD ., using

), used a guide (Baral et al., ), spent longer in the

equation (). We obtained the % confidence intervals

Conservation Area, were more satisfied with their trip (Baral

for the mean amount visitors were willing to pay running

et al., ), were a member of an environmental organiza-

the Monte Carlo simulation developed by Krinsky & Robb

tion, were older, had a higher income level, were more edu-

(). The simulation was implemented in STATA

cated, and were male would all be more likely to pay a higher

(StataCorp, College Station, USA) with the wtpcikr com-

snow leopard conservation fee than others. With respect to

mand (Estimate Krinsky and Robb Confidence Intervals

the latter, the influence of being male is suggested by poten-

for Mean and Median Willingness to Pay; Jeanty, ).

tial income disparity between men and women, as shown in

other contingent valuation studies (Horton et al., ).

The following equation was estimated:

Results

Probability (WTP) =

a + b1 bid amount + b2 snow leopard knowledge Visitor characteristics

+ b3 support for Snow Leopard Conservation Action Plan Of the respondents, .% had no formal education,

+ b4 expectation to see snow leopards .% had completed high school, .% had an associate

+ b5 group size + b6 use of a guide degree/diploma, .% had an undergraduate/bachelor’s de-

+ b7 time in Annapurna Conservation Area gree, .% had a postgraduate/master’s degree, and .%

had a doctoral degree. The mean age of respondents was

+ b8 trip satisfaction + b9 environmental membership

years (n = ). A total of respondents completed

+ b10 age + b11 gender + b12 active in labour force the employment question with .% employed full-time,

+ b13 education level + error .% temporarily employed, .% students, .% other,

(2) .% employed part-time, .% retired and .% home-

where a is the constant and bi are the coefficients of the ex- makers. Less than a fifth (.%) of the respondents were

planatory variables. The goodness-of-fit of the model was members of environmental organizations (n = ). About

estimated using the maximum log-likelihood ratio. We % of respondents answered the question about their

tested the model for misspecification and examined various total household income for the year . They fell into

residual plots. the following income brackets: ,USD , (.%),

USD –, (.%), USD –, (.%), USD

–, (.%), USD –, (.%), –,

Econometrics of willingness to pay (.%), –, (.%) and .USD , (.%).

Visitors from countries were recorded in the sample

We presented the willingness to pay question as a referen- (n = ); the most common were the USA (.%), Israel

dum in which the respondents were asked if they would (.%), Germany (.%), the UK (.%) and Australia

or would not be willing to pay a given bid amount A. It (.%). The average trip satisfaction score for the respon-

was assumed that visitors would maximize their utility dents was . on a -point scale. Almost all of those sur-

while expressing their willingness to pay the specified bid veyed (.%) said that they would recommend the

Oryx, 2019, 53(4), 633–642 © 2018 Fauna & Flora International doi:10.1017/S0030605317001636

Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. IP address: 46.4.80.155, on 02 Feb 2021 at 09:51:24, subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms.

https://doi.org/10.1017/S0030605317001636Funding snow leopard conservation 637

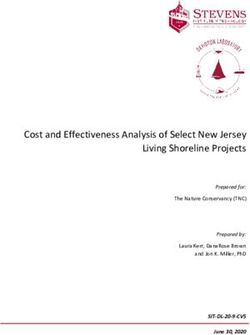

Conservation Area to their family and friends (n = ), and (Fig. ). The logit regression model correctly classified

the majority (.%, n = ) stated that there was no substi- .% of cases (X = ., P , ., Table ). Regarding

tute for the Annapurna Conservation Area in the world. the model’s Pearson residual, deviance residual, Pregibon le-

verage and multicollinearity, no obvious problems were ob-

served in the diagnostic plots. Of the explanatory

Trip characteristics variables, three were statistically significant predictors of

Of the respondents, .% reported that visiting the willingness to pay: number of days spent in the

Annapurna Conservation Area was the primary purpose Conservation Area, support for the Action Plan and the

of their trip to Nepal. Most visitors (.%) had never visited bid amount. A negative association between the willingness

the Conservation Area before. Just under half (.%) to pay and the bid amount indicated that the higher the bid

of the respondents were traveling with friends in a group. amounts the lower the probability of their acceptance. For

The average group size was . (n = ). Approximately each dollar increase in the proposed conservation fee, the

two-thirds (.%) of those who participated in the survey probability of visitors’ willingness to pay decreased by

had hired a trekking guide while in the Conservation Area .%. The probability of willingness to pay would increase

(n = ), and of these, .% rated their guide’s knowledge by .% if respondents also supported the implementation

as ‘excellent’, .% rated it as ‘good’, .% rated it as ‘fair’ of the Action Plan. Similarly, each additional visitor day in

and .% described it as ‘poor’ (n = ). Visitors spent the Conservation Area increased the probability of a positive

on average . days in the Conservation Area (n = ; response to the willingness to pay question by .%.

SD = .), and their mean daily expenditure was USD When the proportion of visitors’ willingness to pay was

. (n = ; SD = .) (Table ). Trekking/hiking was plotted against their snow leopard knowledge assessment

by far the most important activity attracting respondents scores, a clear linear trend was observed in bivariate analysis;

(n = ) to the Conservation Area (.%). This was fol- however, this relationship faded away during multivariate

lowed by nature photography (.%), visiting cultural sites analysis. Contrary to our expectation, the knowledge vari-

(.%), other (.%), research/study (.%), mountaineering able did not explain the significant variance in the willing-

(.%), wildlife viewing or bird watching (.%), visiting ness to pay.

ethnic museums (.%), and more than one reason (.%).

Reasons for and against willingness to pay for snow

Support for the Snow Leopard Conservation Action Plan leopard conservation

When asked to rate the importance of the implementation The majority of respondents (.%) answered the follow-

of the Action Plan, .% stated this was extremely import- up question asking to give a reason for their response to

ant, .% very important, .% somewhat important, .% the willingness to pay question. Respondents who were will-

a little important and .% not at all important. When asked ing to pay gave reasons slightly more frequently (.%)

about their motivations for supporting the implementation than those were not willing to pay (.%). The top three

of the Action Plan, the most important motivation that re- reasons for positive responses were that the visitors liked

spondents who had rated the implementation as very im- the idea of protecting nature, considered the proposed fees

portant or extremely important was: ‘I believe that snow to be reasonable, and felt that conservation of snow leopards

leopards have a right to exist’ (.%, n = ); followed by is crucial. A major reason for visitors’ unwillingness to pay

‘I enjoy knowing snow leopards exist in Annapurna even if was that the proposed fee was too expensive (Table ).

nobody ever sees one’ (.%, n = ); ‘I enjoy knowing

future generations will get pleasure from snow leopards

in Annapurna’ (.%, n = ); ‘I enjoy knowing other Projected impact of conservation fee

people get pleasure from snow leopards in Annapurna’ To understand the possible financial impacts of imposing a

(.%, n = ); ‘I may want to see snow leopards in the snow leopard conservation fee on the local economy we first

future in Annapurna’ (.%, n = ). calculated the gross economic impact of tourism following

the methodology of Baral et al. () based on the esti-

Willingness to pay a snow leopard conservation fee mated visitation rate for the Annapurna Conservation

Area in (Table ). We asked survey participants how

Four hundred of the respondents answered the willing- many days they planned to be in the Conservation Area

ness to pay question (.%). About half of the respondents and how much they expected to spend each day. On average,

(.%) were willing to pay the bid amount stated in their visitors stayed in the Conservation Area for . days and

surveys. The mean amount visitors were willing to pay spent USD . per day, meaning that during their trip to

was USD . (confidence interval .–.) per trip the Conservation Area visitors spend on average USD

Oryx, 2019, 53(4), 633–642 © 2018 Fauna & Flora International doi:10.1017/S0030605317001636

Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. IP address: 46.4.80.155, on 02 Feb 2021 at 09:51:24, subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms.

https://doi.org/10.1017/S0030605317001636638 M. G. Schutgens et al.

TABLE 1 Summary of variables used in the Logit Regression Model.

Variables Description Mean ± SD

Bid amount Respondents were asked varying & randomly drawn conservation fees between USD 5 and 120 59.05 ± 35.22

(ratio scale)

Snow leopard Respondents were asked a number of questions relating to snow leopards, with 1 for a correct 3.79 ± 1.72

knowledge answer, otherwise 0 (nominal scale)

Implementing Snow Respondents were asked how important it was to implement the Action Plan, on a five-point 3.92 ± 0.77

Leopard Conservation scale: not at all important = 1, a little important = 2, somewhat important = 3, very important-

Action Plan = 4, extremely important = 5 (ordinal scale)

Expectation of seeing Respondents were asked whether the presence of snow leopards affected their decision to visit, 1.41 ± 0.88

snow leopards on a five-point scale: not at all important = 1, a little important = 2, somewhat important = 3,

very important = 4, extremely important = 5 (ordinal scale)

Group size Respondents were asked the number of people, including the respondent, travelling to the 3.27 ± 2.58

Conservation Area on a trip together (ratio scale)

Use of a guide Respondents who hired a guide were coded 1, otherwise 0 (binary scale) 0.37 ± 0.48

Visitor days in Respondents were asked the number of days they intended to stay in the Conservation Area 15.89 ± 7.67

Annapurna (ratio scale)

Trip satisfaction Respondents were asked to rate their overall experience on a scale of 1–10, 10 being the most 8.47 ± 1.07

positive (ordinal scale)

Environmental Respondents who reported to be members of environmental organizations were coded 1, 0.17 ± 0.37

membership otherwise 0 (binary scale)

Age Respondents were asked to state the year they were born, which was subtracted from 2014 to give 32.19 ± 11.08

age (ratio scale)

Gender Respondents who identified themselves as men were coded 1 and women were coded 0 (binary 0.58 ± 0.49

scale)

Active in labour force Respondents were considered active in labour force (1) if they were employed full-time or 0.41 ± 0.49

part-time, otherwise not (0) (binary scale)

Education Respondents were asked to record highest level of education attained measured on a 6-point 3.83 ± 1.28

scale: no degree achieved = 1, secondary education = 2, associate degree/diploma = 3, bachelor’s

degree = 4, master’s degree = 5, doctorate degree = 6 (ordinal scale)

FIG. 1 A demand function derived from the

observed positive responses to the

willingness to pay question. The predictions

based on the econometric model are shown

in open circles. A linear trend line is fitted

to the observed frequencies shown in filled

circles.

.. We used this figure and corresponding visitation on the local economy, one of the primary concerns that

rates (adjusted for willingness to pay a snow leopard conser- must be considered (Table ).

vation fee) to calculate the gross economic impact on the

local economy in each scenario. Park revenue was calculated

by multiplying the number of expected visitors (adjusted for Discussion

willingness to pay) by the entrance fee (USD .). The ex-

pected snow leopard revenue was calculated by multiplying The results of this study indicate that foreign visitors are

the number of expected visitors (adjusted for willingness to willing to pay USD . per trip on average, in addition

pay) by the snow leopard fee. In doing so, we were able to to the USD . entrance fee, to support the implementa-

clearly gauge the impact of imposing a snow leopard fee tion of the Snow Leopard Conservation Action Plan in the

Oryx, 2019, 53(4), 633–642 © 2018 Fauna & Flora International doi:10.1017/S0030605317001636

Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. IP address: 46.4.80.155, on 02 Feb 2021 at 09:51:24, subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms.

https://doi.org/10.1017/S0030605317001636Funding snow leopard conservation 639

TABLE 2 Logit regression model of variables influencing responses to the willingness to pay question.

Willingness to pay Coefficient Std. Error z P.z Effect size (%)

Bid amount −0.0308 0.0041 −7.51 0.001 −3.0

Knowledge about snow leopards 0.0047 0.0776 0.06 0.951 0.5

Implementing Action Plan 0.5386 0.1899 2.84 0.005 71.4

Expectation of seeing snow leopards 0.0261 0.1518 0.17 0.864 2.6

Group size 0.0741 0.0532 1.39 0.164 7.7

Use of a guide 0.4442 0.2983 1.49 0.136 55.9

Visitor days in Conservation Area 0.0652 0.0243 2.68 0.007 6.7

Satisfaction from the trip 0.0372 0.1200 0.31 0.757 3.8

Environmental membership 0.4623 0.3586 1.29 0.197 58.8

Age 0.0207 0.0137 1.51 0.131 2.1

Gender −0.0662 0.2635 0.25 0.802 −6.4

Active in labour force 0.1803 0.2849 0.63 0.527 19.8

Education 0.0000 0.1137 0.00 1.000 0.0

Constant −2.9194 1.3976 2.09 0.037

Likelihood-ratio χ = ., P , ., n = , correctly classified cases = .%.

TABLE 3 Reasons for response to willingness to pay question.

Description Frequency (%)

Reasons why visitors were willing to pay an increased fee (n = 188)

To protect nature, forests, wildlife, ecosystems, or environment 23.9%

I can afford it; the entry fee is reasonable 21.3%

Snow leopards must be protected/conserved 15.4%

Tourists/visitors should pay to mitigate their negative impacts 9.6%

I like to donate to worthy causes, general philanthropy 9.0%

Conditional support, only if funds are judiciously used 9.0%

The area is beautiful, unrivalled & unique 7.4%

Likelihood of success 3.7%

To support economic development of the area 0.5%

Reasons why visitors were unwilling to pay an increased fee (n = 186)

I cannot pay; the fee is too expensive 67.2%

Concerns about corruption, misuse & leakage of funds 9.1%

There are other more important concerns e.g. clean drinking water 4.3%

Tourists/visitors should not be the only ones to pay 4.3%

It is the job of the Nepalese government 3.8%

Snow leopards are not important 3.8%

I already support other causes 2.2%

Entry fee is too expensive for shorter visits 1.6%

The project is unlikely to succeed 1.6%

Conservation fees should go to all species 1.6%

I prefer to visit other places 0.5%

TABLE 4 Projected impact of introducing a snow leopard conservation fee in the Annapurna Conservation Area.

Candidate snow % willing Expected Expected park Expected snow Gross economic

leopard fee (USD) to pay visitors revenue (USD) leopard revenue (USD) impact (USD)

0 100 129,966 3,509,082 0 53,935,890

5 91 118,269 3,193,264 591,345 49,162,082

10 88 114,370 3,087,992 1,143,700 47,541,354

20 71 92,276 2,491,448 1,845,517 38,357,229

60 35 45,488 1,228,179 2,729,286 18,908,493

Adapted from Baral et al. (), based on , visitors in (visitor numbers rounded to the nearest whole number).

Oryx, 2019, 53(4), 633–642 © 2018 Fauna & Flora International doi:10.1017/S0030605317001636

Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. IP address: 46.4.80.155, on 02 Feb 2021 at 09:51:24, subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms.

https://doi.org/10.1017/S0030605317001636640 M. G. Schutgens et al.

Annapurna Conservation Area. Their willingness to pay once-in-a-lifetime activity, as suggested by the fact that

was influenced by the time participants spent in the only % of participants had visited the area previously. It

Conservation Area, their support for the Action Plan and is possible that participants may have agreed to higher bid

the bid amount. The main motivation to support the Snow amounts as they were unlikely to return to the Conservation

Leopard Conservation Action Plan was that the snow leop- Area. Similarly, although responses were treated anonym-

ard had the right to exist. Given these results, the critical ously, participants may have agreed to higher bid amounts

question is thus how to translate this economic value attrib- because of perceived peer-pressure to demonstrate their

uted to snow leopards by international tourists into financial willingness to support this cause to fellow travellers or our-

resources for conservation initiatives in the Conservation selves. The mean amount that visitors are willing to pay

Area. A logical policy implication would be to introduce a should thus be seen only as an indication of willingness to

conservation fee for foreign visitors to the Conservation support the conservation of the snow leopard, a species with

Area that directly raises funds for snow leopard conservation currently no use value in the Conservation Area, rather than

initiatives without significantly reducing visitation rates. a figure to be implemented without further consideration.

The introduction of a snow leopard conservation fee set Respondents’ open-ended responses explaining why

at the mean amount that visitors were willing to pay in this they were willing to pay a snow leopard conservation fee

study could theoretically generate c. USD million in funds also have potential management implications for the

per year. This is a significant proportion of the estimated Annapurna Conservation Area. The most common reason

USD . million required to implement the national cited for supporting a conservation fee was to enhance the

Snow Leopard Conservation Action Plan for Nepal in overall protection of nature. The Conservation Area man-

– (DNPWC, ). However, there would be sig- agement may consider showcasing their conservation ef-

nificant financial repercussions to the local economy forts more prominently to visitors, which could enhance

(Table ) as a result of decreased visitation rates to the visitor satisfaction during the trip and increase their willing-

Conservation Area. It is likely that such an aggressive pri- ness to pay (Tisdell et al., ; Baral et al., ). To secure

cing policy would be met with resistance from local tourism long-term support for the initiative, clear disclosure on how

entrepreneurs whose livelihoods would be threatened funds would be spent will be necessary to build trust and

(Laarman & Gregersen, ; Walpole et al., ; Baral achieve optimal acceptance of the scheme, as frequently

et al., ), and could result in increasing resentment to- mentioned in open-ended responses (Table ).

wards snow leopards: a counterproductive outcome. Some This study contributes to research conducted on the total

international visitors may also perceive this proposed fee economic value framework, using the contingent valuation

to be too high. method, with specific reference to threatened species. The

The implementation of a fee set at this study’s mean snow leopard has no apparent use value within the

amount that visitors are willing to pay, as well as that deter- Conservation Area at the time of writing, and although

mined by similar studies elsewhere, may be problematic be- this could change, this study illustrates the importance of

cause of the uncertainties involved in translating a understanding and quantifying existence value, as has

hypothetical scenario into reality. Although there are been emphasized elsewhere (e.g. Han & Lee, ). Nearly

many possible consequences of introducing or increasing % of respondents were not influenced to any degree in

a fee, the economic impacts should be considered carefully. their decision to visit the Conservation Area by the possibil-

For example, both Walpole et al. () and Baral et al. ity of encountering a snow leopard, and yet our results indi-

(), investigating visitor’s willingness to pay entrance cate an opportunity to generate revenue for the conservation

fees to protected areas, avoided recommending the imple- of this species.

mentation of the studies’ mean amount that visitors were

willing to pay in favour of a more ‘reasonable’ fee (based

on expected additional revenue, impact on visitation rates Conclusions

and impact on local economies) to be introduced either in-

crementally or over a trial period. Given these inherent un- International visitors are willing to pay for snow leopard

certainties, we recommend that the Conservation Area conservation in the Annapurna Conservation Area and

management reviews its current pricing policies and consid- their decision is influenced by the number of days they

ers the implementation of a snow leopard conservation fee, spend in the Area and their views on snow leopard conser-

albeit cautiously and in consultation with local communities vation. However, the mean amount they would be willing to

and stakeholders. pay (USD .) would prove difficult to implement given

Despite our best efforts to minimize potential biases the likely detrimental impacts on the local economy and vis-

within this contingent valuation study, some biases cannot itation rates. Although we do not propose the introduction

be ruled out completely, so the results must be viewed cau- of a specific amount, a snow leopard conservation fee imple-

tiously. For many visitors the Conservation Area trek is a mented in the Conservation Area would help offset the costs

Oryx, 2019, 53(4), 633–642 © 2018 Fauna & Flora International doi:10.1017/S0030605317001636

Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. IP address: 46.4.80.155, on 02 Feb 2021 at 09:51:24, subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms.

https://doi.org/10.1017/S0030605317001636Funding snow leopard conservation 641

of snow leopard conservation in the area and possibly the B A L M F O R D , A., B E R E S F O R D , J., G R E E N , J., N A I D O O , R., W A L P O L E , M.

entire country. This decision however, should be viewed & M A N I C A , A. () A global perspective on trends in

nature-based tourism. PLoS Biology (): e.

in light of the likely economic, social and political impacts.

B A L M F O R D , A., B R U N E R , A., C O O P E R , P., C O S T A N Z A , R., F A R B E R , S.,

Although there is significant potential to raise funds for G R E E N , R.E. et al. () Economic reasons for conserving wild

snow leopard conservation in the Conservation Area, it nature. Science, , –.

may not be feasible in other places within snow leopard B A N D A R A , R. & T I S D E L L , C. () Changing abundance of elephants

range where the tourism industry is not well established. and willingness to pay for their conservation. Journal of

Environmental Management, , –.

The Annapurna Conservation Area has a reputation as a

B A R A L , N. & D H U N G A N A , A. () Diversifying finance mechanisms

world-class trekking destination, but other protected areas for protected areas capitalizing on untapped revenues. Forest Policy

in Nepal harbouring snow leopards attract fewer visitors. and Economics, , –.

Therefore, the potential for generating tourism income to B A R A L , N., G A U T A M , R., T I M I L S I N A , N. & B H AT , M.G. (a)

subsidize snow leopard conservation projects may be lim- Conservation implications of contingent valuation of critically

ited at other snow leopard sites within or outside Nepal. endangered White-rumped Vulture Gyps bengalensis in South Asia.

The International Journal of Biodiversity Science and Management,

We propose further research across other range states to de- , –.

termine visitors’ willingness to pay for snow leopard conser- B A R A L , N., S T E R N , M.J. & B H A T T A R A I , R. () Contingent valuation

vation elsewhere and stress the importance of investigating of ecotourism in Annapurna Conservation Area, Nepal:

the economic value of a species as a tool for its conservation, implications for sustainable park finance and local development.

especially in developing countries. Ecological Economics, , –.

B A R A L , N., S T E R N , M.J. & H E I N E N , J.T. (b) Integrated

conservation and development project life cycles in the Annapurna

Conservation Area, Nepal: Is development overpowering

Acknowledgements conservation? Biodiversity and Conservation, , –.

B A R T C Z A K , A. & M E Y E R H O F F , J. () Valuing the chances of survival

We thank the Annapurna Conservation Area staff for pro- of two distinct Eurasian lynx populations in Poland–do people want

viding support and assistance, the hotel owners who gave us to keep the doors open? Journal of Environmental Management, ,

permission to conduct research on their premises, partici- –.

pants for their enthusiasm and patience, and N. Shrestha B R O O K S , T.M., B A K A R R , M.I., B O U C H E R , T., D A F O N S E C A , G.A.B.,

H I LT O N -T AY LO R , C., H O E K S T R A , J.M. et al. () Coverage

and J. Schuurmans for collecting the data during fieldwork. provided by the global protected area system: is it enough?

All necessary permits were obtained prior to fieldwork and BioScience, , –.

the authors followed the guidelines developed by the British B R U N E R , A.G., G U L L I S O N , R.E. & B A L M F O R D , A. () Financial

Sociological Association. JHH was supported by Economic costs and shortfalls of managing and expanding protected area

and Social Research Council Grant ES/J/. systems in developing countries. BioScience, , –.

B R U N E R , A.G., G U L L I S O N , R.E., R I C E , R.E. & D A F O N S E C A , G.A.B.

() Effectiveness of parks in protecting tropical biodiversity.

Science, , –.

Author contributions C A R S O N , R.T. () Contingent valuation: a user’s guide.

Environmental Science & Technology, , –.

MGS, JHH, NB and SBA conceptualized the study and C H A P E , S., H A R R I S O N , J., S P A L D I N G , M. & L Y S E N KO , I. ()

methodology. NB analysed the data. JHH acquired funding. Measuring the extent and effectiveness of protected areas as an

MGS and JHH conducted the field work and prepared the indicator for meeting global biodiversity targets. Philosophical

original draft. NB and SBA reviewed and edited the draft. All Transactions of the Royal Society B, , –.

D I C K M A N , A.J., M AC D O N A L D , E.A. & M AC D O N A L D , D.W. () A

authors approved the final version for submission. review of financial instruments to pay for predator conservation and

encourage human-carnivore coexistence. Proceedings of the

National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, ,

References –.

DNPWC () Snow Leopard Conservation Action Plan (–).

ACAP () Management Plan for Annapurna Conservation Area. Department of National Parks and Wildlife Conservation,

Annapurna Conservation Area Project, Pokhara, Nepal. Kathmandu, Nepal.

A L E , S.B., S H A H , K.B. & J AC K S O N , R. () South Asia: Nepal. In E M E R T O N , L., B I S H O P , J. & T H O M A S , L. () Sustainable Financing

Snow Leopards: Biodiversity of the World: Conservation from Genes of Protected Areas: A Global Review of Challenges and Options. The

to Landscapes. st ed. (eds P.J. Nyhus, T. McCarthy & D. Mallon), World Conservation Union (IUCN), Gland, Switzerland.

pp. –. Elsevier, Amsterdam, Netherlands. G A S T O N , K.J., J AC K S O N , S.F., C A N T Ú -S A L A Z A R , L. & C R U Z -P I Ñ Ó N ,

A L E , S.B., S H R E S T H A , B. & J A C K S O N , R. () On the status of snow G. () The ecological performance of protected areas. Annual

leopard Panthera uncia in Annapurna, Nepal. Journal of Threatened Review of Ecology, Evolution and Systematics, , –.

Taxa, , –. G E L D M A N N , J., B A R N E S , M., C O A D , L., C R A I G I E , I.D., H O C K I N G S , M.

A R R O W , K., S O LO W , R., P O R T N E Y , P.R., L E A M E R , E.E., R A D N E R , R. & & B U R G E S S , N.D. () Effectiveness of terrestrial protected areas

S C H U M A N , H. () Report of the NOAA panel on contingent in reducing habitat loss and population declines. Biological

valuation. Federal Register, , –. Conservation, , –.

Oryx, 2019, 53(4), 633–642 © 2018 Fauna & Flora International doi:10.1017/S0030605317001636

Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. IP address: 46.4.80.155, on 02 Feb 2021 at 09:51:24, subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms.

https://doi.org/10.1017/S0030605317001636642 M. G. Schutgens et al.

G Ö S S L I N G , S. () Sustainable tourism development in developing N E L S O N , F. () Developing payments for ecosystem services

countries: some aspects of energy use. Journal of Sustainable approaches to carnivore conservation. Human Dimensions of

Tourism, , –. Wildlife, , –.

H A N , S.Y. & L E E , C.K. () Estimating the value of preserving the R E S S U R R E I Ç Ã O , A., G I B B O N S , J., D E N T I N H O , T.P., K A I S E R , M.,

Manchurian black bear using the contingent valuation method. S A N T O S , R.S. & E D WA R D S -J O N E S , G. () Economic valuation of

Scandinavian Journal of Forest Research, , –. species loss in the open sea. Ecological Economics, , –.

H A N E M A N N , M.W. () Welfare evaluations in contingent valuation R I C H A R D S O N , L. & L O O M I S , J. () The total economic value of

experiments with discrete responses. American Journal of threatened, endangered and rare species: an updated meta-analysis.

Agricultural Economics, , –. Ecological Economics, , –.

H O R T O N , B., C O L A R U L LO , G., B AT E M A N , I.J. & P E R E S , C.A. () R I C H A R D S O N , L., R O S E N , T., G U N T H E R , K. & S C H WA R T Z , C. ()

Evaluating non-user willingness to pay for a large-scale The economics of roadside bear viewing. Journal of Environmental

conservation programme in Amazonia: a UK/Italian Management, , –.

contingent valuation study. Environmental Conservation, , R I P P L E , W.J., E S T E S , J.A., B E S C H T A , R.L., W I L M E R S , C.C., R I T C H I E , E.

–. G., H E B B L E W H I T E , M. et al. () Status and ecological effects of

J AC K S O N , R. & A H L B O R N , G. () The role of protected areas in the world’s largest carnivores. Science, https://doi.org/./

Nepal in maintaining viable populations of snow leopards. In science..

International Pedigree Book of Snow Leopards Panthera uncia S N OW L E O P A R D W O R K I N G S E C R E TA R I AT () Global Snow Leopard

Volume (ed. L. Blomqvuist), pp. –. Helsinki Zoo, Helsinki, and Ecosystem Protection Program. Http://www.globalsnowleopard.

Finland. org/ [accessed February ].

J AC K S O N , R.M., M I S H R A , C., M C C A R T H Y , T. & A L E , S.B. () Snow T I S D E L L , C. & W I L S O N , C. () Nature-based Tourism and

leopards, conservation and conflict. In The Biology and Conservation: New Economic Insights and Case Studies. Edward

Conservation of Wild Felids (eds D.W. Macdonald & A.J. Loveridge), Elgar Publishing, Cheltenham, UK.

pp. –. Oxford University Press, Oxford, UK. T I S D E L L , C., S WA R N A N A N T H A , H. & W I L S O N , C. ()

J E A N T Y , P.W. () Constructing Krinsky and Robb confidence Endangerment and likeability of wildlife species: how important are

intervals for mean and median willingness to pay (WTP) using stata. they for payments proposed for conservation? Ecological Economics,

In th North American Stata Users’ Group Meeting, Boston, , –.

Massachusetts. V E N K A TAC H A L A M , L. () The contingent valuation method: a

K R I N S K Y , I. & R O B B , A.L. () On approximating the statistical review. Environmental Impact Assessment Review, , –.

properties of elasticities. The Review of Economics and Statistics, , W A L P O L E , M.J., G O O D W I N , H.J. & W A R D , K.G.R. () Pricing

–. policy for tourism in protected areas: lessons from Komodo

L A A R M A N , J.G. & G R E G E R S E N , H.M. () Pricing policy in National Park, Indonesia. Conservation Biology, , –.

nature-based tourism. Tourism Management, , –. W E G G E , P., P O K H E R A L , C.P. & J N AWA L I , S.R. () Effects of

L I N D S E Y , P.A., A L E X A N D E R , R.R., D U T O I T , J.T. & M I L L S , M.G.L. trapping effort and trap shyness on estimates of tiger abundance

() The potential contribution of ecotourism to African wild dog from camera trap studies. Animal Conservation, , –.

Lycaon pictus conservation in South Africa. Biological Conservation, W I L S O N , C. & T I S D E L L , C. () How knowledge affects payment to

, –. conserve an endangered bird. Contemporary Economic Policy, ,

L I N N E L L , J.D.C., S W E N S O N , J.E. & A N D E R S O N , R. () Predators and –.

people: conservation of large carnivores is possible at high human W O R L D T O U R I S M O R G A N I Z AT I O N () UNWTO Annual Report

densities if management policy is favourable. Animal Conservation, . UNWTO, Madrid, Spain.

, –.

L O O M I S , J.B. & W H I T E , D.S. () Economic benefits of rare and

endangered species: summary and meta-analysis. Biological

Economics, , –.

M C C A R T H Y , T., M A L LO N , D., J AC K S O N , R., Z A H L E R , P. & Biographical sketches

M C C A R T H Y , K. () Panthera uncia. The IUCN Red List of

Threatened Species : e.TA. Http://www. MA U R I C E SC H U T G E N S works as a project manager for an elephant

iucnredlist.org/details// [accessed th October ]. conservation NGO in north central Kenya. He is particularly interested

M C C A R T H Y , T.M. & C H A P R O N , G. (eds) () Snow Leopard in the fields of human–wildlife conflict mitigation and the impacts of

Survival Strategy. ISLT and SLN, Seattle, USA. the illegal wildlife trade. JO N A T H A N HA N S O N is researching the

M O R A , C. & S A L E , P.F. () Ongoing global biodiversity loss and the human dimensions of snow leopard conservation. He is particularly

need to move beyond protected areas: a review of the technical and interested in the intersections between livestock farming and wildlife

practical shortcomings of protected areas on land and sea. Marine conservation. N A B I N B A R A L is interested in the human dimensions

Ecology Progress Series, , –. of natural resource management, resilience of social-ecological sys-

N A M G A I L , T., M A J U M D E R , B., D A D U L , J., A G VA A N T S E R E N , B., A L L E N , tems, sustainable tourism and protected area management. He re-

P., D A S H Z E V E G , U. et al. () Incentive and reward programs in searches the intricate linkages between nature and society. SO M AL E

snow leopard conservation. In Snow Leopards (eds T. McCarthy & is a wildlife ecologist. He works on snow leopard research, education

D. Mallon), pp. –. Elsevier, London, UK and New York, USA. and conservation.

Oryx, 2019, 53(4), 633–642 © 2018 Fauna & Flora International doi:10.1017/S0030605317001636

Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. IP address: 46.4.80.155, on 02 Feb 2021 at 09:51:24, subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms.

https://doi.org/10.1017/S0030605317001636You can also read