The Time Needed for Clinical Documentation versus Direct Patient Care

←

→

Page content transcription

If your browser does not render page correctly, please read the page content below

84 © Schattauer 2009 Original Articles

The Time Needed for Clinical

Documentation versus Direct

Patient Care

A Work-sampling Analysis of Physicians’ Activities

E. Ammenwerth; H.-P. Spötl

Institute for Health Information Systems, UMIT – University for Health Sciences, Medical

Informatics, and Technology Tyrol, Hall in Tyrol, Austria

(physicians, nurses, etc.), clinical areas (radi-

Keywords ing physicians on two internal medicine

ology, surgery, etc.), and health care organi-

Documentation, time and motion studies, wards of a 200-bed hospital in Austria. A

zations (primary care, hospitals, nursing

workload, physicians, medical record systems 37-item classification system was applied to

homes, etc.), producing a high demand for

categorize tasks into five categories (direct

Summary the documentation and communication of

patient care, communication, clinical docu-

Objectives: Health care professionals seem patient-related data. This is aggravated by

mentation, administrative documentation,

to be confronted with an increasing need for rising economic pressure, decreasing lengths

other).

high-quality, timely, patient-oriented docu- of stay [2], and legal regulations all requiring

Results: From the 5555 observation points,

mentation. However, a steady increase in additional documentation under great time

physicians spent 26.6% of their daily working

documentation tasks has been shown to be pressure. Overall, health care professionals

time for documentation tasks, 27.5% for di-

associated with increased time pressure and seem to be confronted with an increasing

rect patient care, 36.2% for communication

low physician job satisfaction. Our objective need for high-quality, timely, patient-

tasks, and 9.7% for other tasks. The documen-

was to examine the time physicians spend on oriented documentation.

tation that is typically seen as administrative

clinical and administrative documentation An increase in administrative tasks has

takes only approx. 16% of the total documen-

tasks. We analyzed the time needed for clini- been shown to be associated with increasing

tation time.

cal and administrative documentation, and time pressure and low physician job satis-

Conclusions: Nearly as much time is being

compared it to other tasks, such as direct faction [3], whereas adequate time for phy-

spent for documentation as is spent on direct

patient care. sician-patient interaction seems to be associ-

patient care. Computer-based tools and, in

Methods: During a 2-month period (De- ated with higher physician satisfaction [4].

some areas, documentation assistants may

cember 2006 to January 2007) a trained in- Furthermore, in Austria, this rising need for

help to reduce the clinical and administrative

vestigator completed 40 hours of 2-minute documentation is criticized by clinicians and

documentation efforts.

work-sampling analysis from eight participat- regarded as a danger for the quality of patient

care. The Austrian Medical Association states

that clinicians spend too much time at the

Methods Inf Med 2009; 48: 84–91 computer, and that the administrative and

Correspondence to:

doi: 10.3414/ME0569 documentation tasks (“paper chaos”) are

Elske Ammenwerth

received: May 3, 2008 taking too much time away from patient care

Institute for Health Information Systems

accepted: August 15, 2008 [5]. A recent survey of 2000 Austrian hospital

UMIT – University for Health Sciences,

prepublished: physicians showed decreasing job satisfaction

Medical Informatics,

compared to earlier years, with 82% of the

and Technology Tyrol

physicians stating that they feel stressed

Eduard Wallnöfer Zentrum 1

partly or heavily due to administration and

6060 Hall in Tyrol

documentation tasks [6] – this representing

Austria

the category with the highest stress level,

E-mail: elske.ammenwerth@umit.at

higher than, for example, stress from a high

personal workload or from night shifts. In

this survey, 53% of the physicians stated that,

Introduction other things, increase the quality and efficien- in recent years, work has become more

cy of patient care, and to support health care unpleasant, with increasing documentation

Health care is increasingly influenced by the professionals in their daily tasks. Modern and administration efforts being the fre-

use of modern information technologies (IT) health care is characterized by the distribu- quently mentioned reasons (52%) for this

[1]. IT systems are introduced to, among tion of tasks between professional groups feeling [6].

Methods Inf Med 1/2009E. Ammenwerth; H.-P. Spötl: The Time Needed for Clinical Documentation versus Direct Patient Care 85

Researchers, therefore, have attempted to Objectives of this Paper advantage is that work sampling just provides

quantify the actual time needed for docu- an estimate of the real-time distribution [18].

mentation, especially compared to the time The objectives of this paper were, therefore, to In addition, work sampling is only feasible

available for direct patient care. For example, objectively measure the time physicians when the clinicians remain in a defined area,

in an outpatient oncology clinic, Fontaine et spend on clinical and administrative docu- where they can easily be located by the ob-

al. found that U.S. physicians spend 29% of mentation tasks, and to compare it with the server. Both time-motion studies as well as

their time entering and retrieving informa- time needed for other activities. work sampling have been conducted in clini-

tion from paper-based medical records, and cal areas for many years [19]. In the 23 studies

43% on direct patient care [7]. In another reviewed by Poissant et al., 58% used time

U.S. study, Gottschalk et al. found that family Methods motion, 33% work sampling, and 8% a self-

physicians spend 55% of their time with face- report survey approach [9].

to-face patient care, while other activities pri- The traditional methods for time measure- For our present study, we selected work

marily involved reviewing medical records, ment comprise either the subjective esti- sampling, as it allows for only one observer

writing notes, and writing prescriptions [8]. mation by the actors themselves in a survey, documenting the activities of several clini-

For Austria, the Austrian Medical Association or the objective measurement by a trained cians. We followed the steps of work sampling

estimates that physicians in hospitals spend observer. The second method is typically pre- as described by Sittig [20]: First, the identifi-

no more than 63% of their time for direct ferred, as the first one only provides an impre- cation of working categories; then, the con-

patient care, without providing the source of cise, and potentially biased, measure of ac- duction of a pilot study for a sample size cal-

these data [5]. tivity [11]. For objective time measurements, culation; finally, the conduction and analysis

The electronic patient record (EPR) and the two most widely-used approaches are of the main study.

other more specialized computer-based time-motion studies, as introduced by F. W. Our analysis was conducted at a 200-bed

documentation systems promise to support Tayler (in the 1880s) [12], and work sam- hospital in Tyrol between November 2006

documentation and to reduce documen- pling, as introduced by L. H. C. Tippett (in the and January 2007. The study was conducted

tation efforts. Several evaluation studies have 1930s) [13]. in two wards of the inpatient area of the de-

investigated the relationship between intro- In time-motion studies, trained observers partment of internal medicine. Both wards

duction of an EPR system and time efficiency. measure the duration of activities by docu- admit around 520 patients each year. The

In a recent review, Poissant et al. [9] analyzed menting their beginning and end, using a mean patient length of stay in this depart-

seven studies evaluating the effects of an EPR predefined classification of activities. This ment is around 18 days, with mostly post-

on the time efficiency of physicians. Four of method has been applied, for example, to surgical patients treated. All of the eight

those studies reported an increase in the measure the impact of an EPR system on the physicians (one doctor-in-training, four resi-

documentation time (by 11-41%), whereas time use of oncologists [14], or to analyze the dent physicians, three senior physicians)

three studies reported a reduction (by time needed after the introduction of com- working in the observed wards during the

13–46%). Poissant et al. [9] found com- puter-based physician order entry [15]. study period agreed to participate and were

parable varying results when analyzing In a work-sampling analysis, a trained ob- included in the study.

studies on the time efficiency of nurses. Rea- server documents which activity is just being This hospital is equipped with a clinical

sons for the observed differences among the executed at predefined (for example, every five information system (Cerner Millenium,

reviewed studies may comprise differences in minutes) or randomly selected moments in [21]) that supports several clinical activities,

the amount of documented information, in time, also by using a predefined classification such as order entry and result reporting for

hardware equipment (for example mobile of activities. By counting the number of ob- lab and x-ray, report writing, and patient-

tools), clinical workflow, and usability and served activities in each category, the overall related scheduling. A paper-based record is

quality of the IT systems in the evaluated set- distribution and thus the duration of each still maintained for the documentation of

tings [7, 9]. An increase in workload for phys- task can be estimated. The larger the number of clinical admissions, vital signs, prescriptions,

icians can lead to low user satisfaction and observations, the more precise this estimation ongoing status documentation, and nursing

even user boycott [10]. can be. Work sampling was used, for example, care planning.

Overall, a rising demand for clinical and to study the work distribution of physicians We developed the initial classification of

administrative documentation may lead to a in a general medical service unit [16]. activities that are needed for the work-sam-

decrease in the direct time available for pa- The most important advantage of work pling analysis, based on an earlier work of

tient care and reduced job satisfaction for sampling is that the data for several clinicians Blum et al. who investigated the documen-

physicians. This problem is currently being can be obtained by only one observer, which tation efforts in German hospitals [22].

actively discussed in Austria. However, there makes it rather efficient compared to con- Castelein later adapted Blum’s classification

seems to be no objective data on the overall tinuous time-motion studies where, typically, for an Austrian hospitals’ setting [23]. We

time for documentation compared to the one observer shadows one clinician [17]. In used his classification as the basis for our

overall time for patient care. addition, work sampling minimizes the risk study. We also reviewed the international

that clinicians’ behavior will be affected by literature to check the completeness of our

being observed permanently [7]. The dis- classification system.

© Schattauer 2009 Methods Inf Med 1/200986 E. Ammenwerth; H.-P. Spötl: The Time Needed for Clinical Documentation versus Direct Patient Care

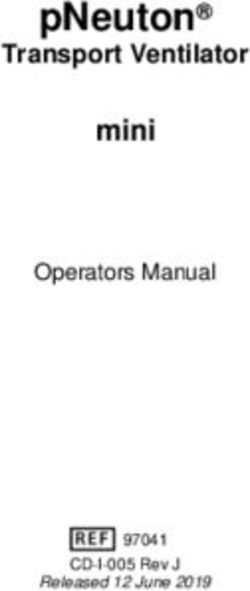

Table 1 Distribution of the most important activities of the observed physicians for the overall study The resulting list of activities was refined

period. Mean and standard deviation of the percentage of the overall working time is indicated. Only by a pilot study in the hospital, which was

those categories higher than 1.5% (for categories I to III) resp. higher than 0.5% (for categories IV and conducted in November 2006. This pilot

V) are indicated. For a complete list and definition of the categories, see Appendix. study comprised both direct observations of

Category Mean (Standard Deviation)

clinical workflow as well as interviews with

the physicians. The interviews that were con-

I. Direct patient care 027.5% (10.5%) ducted with two physicians were used to dis-

Communication with patients 00 9 .3% (5.5%)

cuss face validity of our instrument, and to

Other patient care 00 7 .2% (6.0%)

check the definitions of each category. The di-

Medical activities 00 5 .9% (5.3%)

Read in patient record 00 5 .1% (3.2%) rect observations within the pilot study lasted

Waiting for patient 00 0 .0% (0.1%) eight hours using a one-minute work sam-

pling interval. The observations were used to

II. Communication 036.2% (10.5%) train the observer, to test the prepared docu-

Personal communication with physicians 0 12.9% (6.8%) mentation form and to assess the complete-

Regular meetings 0 10.0% (8.4%) ness and clarity of each category. Overall, only

Phone calls 00 4.6% (3.2%) slight modifications mostly in wording of in-

Personal communication with non-physicians 00 4.0% (2.5%)

dividual categories were done as a result of

Other communication 00 1.6% (2.9%)

the pilot study. The pilot study was conducted

III. Clinical documentation 022.4% (10.7%) by that observer who also conducted the final

Writing of a preliminary discharge letter 00 4.5% (3.9%) study. No further formal reliability testing of

Ongoing clinical documentation 00 3.2% (3.0%) the instrument was conducted.

Writing of a final discharge letter 00 3.6% (2.8%) The findings from the pilot observations

Documentation of an initial examination 00 2.2% (3.1%) were used to calculate the needed number of

Prepare documentation forms 00 3.4% (2.6%) observations, using the formula provided by

Documentation of findings 00 1.9% (2.6%) Sittig (n = p (1 – p)/σ2, with n = total number

Prepare forms for order entry 00 1.9% (1.1%)

of observations, p = expected percentage of

Documentation of medication 00 1.5% (1.4%)

time required by the most important cat-

IV. Administrative documentation 004.2% (4.6%) egory of study (estimated from pilot), and σ

Generation of duty rosters 00 2.1% (4.6%) standard deviation of percentage) [20]. Based

Writing of discharge documents 00 0.7% (1.8%) on this formula, we calculated n = 2244 for

Completing of transportation orders 00 0.5% (0.9%) our study. Estimating a planned duration of

Other administrative documentation 00 0.5% (0.9%) observation of 5 days à 8 hours, this n would

be reached by 449 observations per day resp.

V. Other activities 009.7% (7.4%)

28 observations per hour. This means one

Walking times 00 2.6% (1.4%)

observation every two minutes.

Breaks 00 5.1% (3.6%)

Other 00 2.1% (7.1%) The final classification system comprised

37 categories, 21 describing documentation

Sum 100% activities, with 11 related to clinical docu-

mentation and 10 to administrative docu-

mentation. 씰Appendix 1 shows the classifi-

cation system.

The main work-sampling study was con-

ducted in December 2006 and January 2007,

and comprised 40 hours of observations dur-

ing the day shifts, with each day of the week

covered equally. Based on the results from the

pilot study, the chosen sampling period was

two minutes. The observer (HS) used a pro-

grammable watch that beeped every two

Fig. 1

minutes. Typically, three to four physicians

Distribution of the

activities of the ob- were observed in parallel by the observer. A

served physicians for typical observation session lasted eight hours.

the overall study If necessary, the observer looked into the pa-

period. The details tients’ rooms in case one of the physicians was

are shown in Table 1. there at the moment of observation, to

Methods Inf Med 1/2009 © Schattauer 2009E. Ammenwerth; H.-P. Spötl: The Time Needed for Clinical Documentation versus Direct Patient Care 87

capture patient-related activities. Overall, 30 documentation effort of an individual phy- none of the studies reviewed by Poissant et al.

so-called physician-days were observed (a sician was 21.6% of the overall working time, [9] were comparable to our study. Most

physician-day reflecting a full-day observa- and the highest was 36.2%. In 12 of 30 ob- studies focus either on other professional

tion of one physician). served individual physician-days, the daily groups (for example nurses), on outpatient

The observation form that we used docu- documentation load for a physician was near areas, on specialized inpatient clinical settings

mented the following information for each 30% or above. (such as intensive care or emergency care

observation point: the actor (name of phy- units), or only on certain activities (such as

sician); the performed activity (see Appen- order entry). For example, the study of Gott-

dix); and the tool used (computer-based, Discussion schalk et al. [8] analyzing activities of general

paper-based, or other). Overall, 5500 obser- physicians found that they spent around 20%

vations were documented. MS Excel 2003 was Meaning and Generalizability of their time documenting – this lower

used to analyze the respective data. First, for of the Results number may reflect, however, the lower docu-

each individual physician, the number of ac- mentation requirements in outpatient care.

tivities documented in each category was Our most interesting finding was the sub- Oddone et al. [24] analyzed the work dis-

translated into an individual percentage, stantial proportion of 27% of the working tribution of 36 physicians at a university

using the overall number of documented time dedicated to documentation, compris- medical center and found 43.6% for “patient

activities of this physician as denominator. ing both clinical and administrative tasks. evaluation” (comprising direct patient care

Then, based on those numbers, the mean and We conducted our work-sampling analysis and discussing patient care), 18.9% for edu-

standard deviation of the categories of all during the main working hours, i.e. 8 a.m. to cational activities, and 13.9% for adminis-

physicians were calculated. 4.30 p.m. Physicians later stated that they tration (for example charting, dictating,

often work overtime (i.e. after 4.30 p.m.), to label/forms). Here it is unclear as to whether

finalize documentation tasks. If we estimate the activities noted for patient evaluation

Results that this overtime was around 40 minutes per (such as physical exam, patient history, and

physician per day during the study period (as ward rounds) may have also included related

씰Table 1 and 씰Figure 1 show the overall re- estimated from the administrative working documentation activities. Educational activ-

sults of the work-sampling study. 27.5% of all time documentation of the department), the ities were not relevant in our study, as the hos-

activities were related to direct patient care, overall daily documentation workload would pital is not an academic hospital. Hollings-

36.2% to communication activities, 26.6% to increase from 26.6% to 32.4%. worth et al. [25] used a time-motion study to

documentation activities, and 9.7% to other Before the study, the hospital manage- analyze the time distribution in an emergency

activities. The clinical documentation activ- ment had stated that the documentation unit. They found that the observed ten faculty

ities accounted for 22.4%. Documentation should not exceed 30% of the working time. physicians spent 32% of their time on direct

activities typically defined as “adminis- While the mean (without overtime) is just patient care, 22% on communication, and

trative” (i.e. coding for billing purposes, below this threshold, each of the eight ob- around 18.5% on charting and other paper-

documentation for quality management) ac- served physicians spend at least one day work. Mamlin et al. [19] conducted a com-

counted for 4.2% overall, that is 15.7% of all (from five) with more than 30% of their time bined time-and-motion and work-sampling

documentation time. needed for documentation activities. study in a general medicine clinic and found

We also documented which tools were In a survey-based self-assessment study of that physicians spent 37.8% of their time

used for the documentation activities (cat- 1010 German physicians conducted by Blum charting, this reflecting the purely paper-

egories III and IV). Here, we found that for et al., they found a documentation effort of based documentation at the time of the study.

49.3 ± 19.7% of the documentation tasks, 40.6% [22]. The Austrian Medical Associ- A recent study by Westbrook et al. [26] is

paper-based tools (for example paper-based ation has stated that physicians in hospitals better comparable to our study; they used a

patient record, paper-based forms for order spend up to 63% of their time on documen- time-motion approach to quantify work

entry or duty rostering) were used. Com- tation [5]. Those subjective estimations may activities of doctors in a 400-bed teaching

puter-based tools (for example electronic pa- be biased [24] – a rising dissatisfaction of hospital where also a mix of computer-based

tient record, office, and statistic tools) were physicians in Germany and Austria with what and paper-based tools was used. They found

used for 49.3 ± 19.7% of the documentation they call “bureaucracy” may have led to those that 33% of the time was spent on professional

tasks. rather high subjective estimates. Our objec- communication, 32% on (direct and indirect)

We also analyzed the activity distribution tive measurements confirm that the docu- patient care, and 12% for documentation (ex-

for each individual physician to calculate the mentation efforts in the inpatient area are cluding medication documentation).

individual daily and weekly documentation quite high with 27%. However, only one-sixth A high documentation effort is often not

effort. The lowest daily documentation effort of this time is clearly devoted to adminis- well accepted, and physicians argue that

of an individual physician at a given day was trative documentation. documentation takes away time from direct

8.5% (for a resident), the highest 55.5% (for a Studies that analyzed the distribution of patient care, and thus endangering the quality

senior physician). When analyzing activity physicians’ activities in a clinical setting com- of care. Especially documentation tasks that

distribution over one week, the lowest weekly parable to our study are rare. For example, are seen as not directly related to patient care

© Schattauer 2009 Methods Inf Med 1/200988 E. Ammenwerth; H.-P. Spötl: The Time Needed for Clinical Documentation versus Direct Patient Care

(such as documentation for quality manage- physician (this is comparable to the 5% found who used 29 categories. Other authors have

ment or for legal reasons) are often not well by Westbrook et al. [26]), which means ap- used much fewer detailed categories for

accepted. In our study, we found 4.2% of the prox. 30% of the overall documentation time. documentation. For example, Bürkle et al.

working time (i.e. 15.7% of all the documen- Better computer-based support (including [33] used 23 categories to document nursing

tation time) is spent exclusively on “adminis- speech recognition and computer-supported activities, only one of which was clearly re-

trative” documentation tasks, arguably re- correction workflow) may help to reduce lated to documentation activities. Westbrook

flecting a moderate effort. In addition, both documentation efforts, and reduce the turn- et al. [26] used 22 categories, two of them

clinical and administrative documentation is around time of discharge letters. devoted to documentation.

vital to provide good-quality, affordable and In Austria, physicians’ organizations are We decided to execute the work-sampling

coordinated care to patients [8], especially in calling for the introduction of so-called observations at fixed intervals. Sittig [20] rec-

a health care setting that is characterized by a documentation assistants [5], who would ommends fixed intervals for observation of

large number of different professional groups take over certain documentation tasks in random work activities such as the hospital-

and institutions and by rising economic pres- order to reduce the workload of the phy- related activities in our study. For fixed obser-

sure. Therefore, the question should not just sicians. However, if we look at the documen- vations, Nickman [11] recommends a mini-

be how to reduce the documentation efforts, tation activities, only a few of them (such as mum of eight observations per hour. With 30

but rather how to plan and organize it to best coding of diagnosis and services, completion observations per hour, we were well over this

support patient care [27]. of transportation orders, documentation for limit. The 2-minute interval observations

Computer-based documentation systems quality management, preparation of docu- placed a high workload on the observer, but

may be helpful in streamlining documen- mentation forms) seem to be appropriate for guaranteed that the activities of a short du-

tation tasks, integrating data, and avoiding delegation to documentation assistants. ration were captured, which increased the

unnecessary double data entry. In our hospi- Other major documentation activities such precision of our measurements. Instead of

tal, already around half of the documentation as discharge letter writing, ongoing clinical using a paper-based work-sampling form, in

tasks are supported by computer-based tools, documentation, documentation of initial order to reduce the time needed for data

and this percentage is expected to increase in examinations, and documentation of medi- analysis as well as to eliminate transcription

the coming years. For example, the documen- cation, could not be delegated to non- errors, the use of a PDA for activity docu-

tation of the initial examination and of the medical professionals. In our opinion, it is, mentation might have been helpful, as, for

medical history is still performed on paper- therefore, questionable as to whether docu- example, proposed by [34] and used in

based forms. By using bedside terminals or mentation assistants can help to reduce studies by [11, 26].

mobile tools, such as laptops or PDAs, docu- documentation tasks of physicians. Earlier Our results may be subject to certain er-

mentation may be facilitated and might in- studies showed that a medical assistant can rors. For example, a misinterpretation of the

crease the data quality [28, 29]. In addition, help support physicians in certain areas of work category definitions is one possible

the use of mobile tools could also help to re- general information logistics, such as looking source of error. We attempted to limit the im-

duce the time needed for the paper-based for records or test results [32]. However, these pact of this threat by having just one well-

documentation of medication and other were results from mostly settings using trained observer, by defining each category,

clinical notes as well as for general order paper-based records and may not be repro- and by conducting a pilot study to validate

entry, which are at the moment performed in ducible in settings with already high levels of the working categories. Overall, each of our

the paper-based records. Using a CPOE sys- computer support. physicians was observed over approximately

tem (computerized physician order entry) four full days. We cannot be certain that the

may even help to increase patient safety by of- observed days were representative, even when

fering checks and alerts [30, 31]. Altogether, Strengths and Weaknesses we attempted to guarantee representative

we estimate that another approx. 25% of the of the Study days by distributing the observation days

documentation time could be supported by equally over the whole week and over two

computer-based point-of-care tools. Using work sampling it was possible for us to months. On all the observation days, the bed

In addition, workflow reorganization may observe four physicians at the same time be- occupancy was high, which seems to be rep-

help to reduce any unnecessary documen- cause physicians mostly stayed in the defined resentative for the overall situation of the

tation tasks. For example, the writing of dis- area of a ward. The observer only had to take observed department.

charge letters is – at the moment – a rather a short look at what a physician was doing at a The present study was conducted in a de-

complicated process, with a physician dictat- certain moment, thereby minimizing the partment of internal medicine, characterized

ing both a preliminary and later a final letter, danger of a Hawthorne effect and avoiding by a mean length of stay of approx. 18 days,

and the final letter is written by secretaries any disturbance of the clinical workflow. and with mostly post-surgical patients

with a long paper-based correction process We developed a classification system with treated. This duration of stay is much higher

involving the author as well as the senior and 37 activity categories, 21 of which were re- than the overall mean duration of stay in Aus-

head physician. Overall, discharge letter pro- lated to documentation activities, as this was trian hospitals, which was 5.7 days in 2006 [2].

duction (both preliminary and final ones) the major focus of our study. Our classifi- Our results may, therefore, not be generaliz-

sums to 8% of the daily working time of a cation was based on the work of Blum [22] able to other inpatient settings in Austria.

Methods Inf Med 1/2009 © Schattauer 2009E. Ammenwerth; H.-P. Spötl: The Time Needed for Clinical Documentation versus Direct Patient Care 89

http://www.ifes.at/upload/1156086926_folie.pdf. aufnahme und Verbesserungsvorschläge – Unter-

Conclusion Last accessed: August 1, 2008. suchung im Auftrag der Deutschen Kranken-

7. Fontaine BR, Speedie S, Abelson D, Wold C. A work- hausgesellschaft [Clinical documentation effort

We found that a substantial proportion of sampling tool to measure the effect of electronic in hospitals]. Düsseldorf: Wissenschaft und Praxis

26.6% of working time was dedicated to medical record implementation on health care der Krankenhausökonomie (Band 11). Deutsche

documentation in a department of internal workers. J Ambul Care Manage 2000; 23 (1): 71–85. Krankenhaus Verlagsgesellschaft. ISBN

8. Gottschalk A, Flocke SA. Time spent in face-to-face 3-935762.22-4; 2003. http://www.dkvg.de/index.

medicine, 22.4% of which was for clinical patient care and work outside the examination php?cat=c23_Wissenschaft-und-Praxis-der-

documentation, and 4.2% for administrative room. Ann Fam Med 2005; 3 (6): 488–493. Krankenhausoekonomie.html. Last accessed: Au-

documentation. The time for direct patient 9. Poissant L, Pereira J, Tamblyn R, Kawasumi Y. The gust 1, 2008.

care was 27.5% and, therefore, was only impact of electronic health records on time efficien- 23. Castelein J. Analyse des Dokumentationsaufwands

cy of physicians and nurses: a systematic review. J im ärztlichen Bereich und seine Auswirkung auf die

slightly higher than the time spent for docu- Am Med Inform Assoc 2005; 12 (5): 505–516. Arbeitszeitbelastung von Krankenhaus-Ärzten am

mentation. The further introduction of com- 10. Ornstein C. California; Hospital Heeds Doctors, Beispiel des Landeskrankenhauses Innsbruck (Uni-

puter-based tools and the reorganization of Suspends Use of Software: Cedars-Sinai physicians versitätskliniken). PhD thesis, UMIT – University

the working processes (such as discharge entered prescriptions and other orders in it, but for Health Sciences, Medical Informatics and Tech-

called it unsafe. In: The Los Angeles Times, Jan 22; nology, Hall in Tyrol, Austria. In preparation; 2008.

letter writing) may help to reduce the docu- 2003. 24. Oddone E, Guarisco S, Simel D. Comparison of

mentation efforts that physicians often state 11. Nickman NA, Guerrero RM, Bair JN. Self-reported housestaff ’s estimates of their workday activities

are excessively high. Further research is work-sampling methods for evaluating phar- with results of a random work-sampling study.

maceutical services. Am J Hosp Pharm 1990; 47 (7): Acad Med 1993; 68 (11): 859–861.

needed to see whether similar results can be

1611–1617. 25. Hollingsworth JC, Chisholm CD, Giles BK, Cordell

found in other inpatient settings with a short- 12. Barnes R. Motion and Time Study Design and WH, Nelson DR. How do physicians and nurses

er mean duration of stay. In addition, evalu- Measurement of Work. 6th ed. New York: John spend their time in the emergency department?

ation studies may help to show how docu- Wiley and Sons; 1968. Ann Emerg Med 1998; 31 (1): 87–91.

13. Tippett L. Statistical Methods in Textile Research. 26. Westbrook JI, Ampt A, Kearney L, Rob MI. All in a

mentation efforts will develop after the intro- Uses of the Binomial and Poissant Distributions. J day’s work: an observational study to quantify how

duction of computer-based tools and/or the Textile Inst Trans 1935 (26): 51–55. and with whom doctors on hospital wards spend

employment of documentation assistants. 14. Pizziferri L, Kittler AF, Volk LA, Shulman LN, their time. Med J Aust 2008; 188 (9): 506–509.

Kessler J, Carlson G, et al. Impact of an Electronic 27. Leiner F, Haux R. Systematic Planning of Clinical

Health Record on oncologists’ clinic time. AMIA Documentation. Methods Inf Med 1996; 35 (1):

Acknowledgments Annu Symp Proc 2005. p 1083. 25–34.

We thank the management and staff of the 15. Overhage JM, Perkins S, Tierney WM, McDonald 28. Lu YC, Xiao Y, Sears A, Jacko JA. A review and a

analysed Tyrolean hospital for their co-oper- CJ. Controlled trial of direct physician order entry: framework of handheld computer adoption in

effects on physicians’ time utilization in ambulatory healthcare. Int J Med Inform 2005; 74 (5): 409–422.

ation and support. primary care internal medicine practices. J Am Med 29. Wu RC, Straus SE. Evidence for handheld electronic

Inform Assoc 2001; 8 (4): 361–371. medical records in improving care: a systematic re-

16. Guarisco S, Oddone E, Simel D. Time analysis of a view. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak 2006; 6: 26.

general medicine service: results from a random 30. Kaushal R, Shojania KG, Bates DW. Effects of com-

References work sampling study. J Gen Intern Med 1994; 9 (5): puterized physician order entry and clinical deci-

272–277. sion support systems on medication safety: a sys-

1. Haux R, Ammenwerth E, Herzog W, Knaup P. 17. Wirth P, Kahn L, Perkoff GT. Comparability of two tematic review. Arch Intern Med 2003; 163 (12):

Health Care in the Information Society: A Progno- methods of time and motion study used in a clinical 1409–1416.

sis for the Year 2013. Int J Med Inform 2002; 66 setting: work sampling and continuous observa- 31. Rothschild J. Computerized physician order entry

(1–3): 3–21. tion. Med Care 1977; 15 (11): 953–960. in the critical care and general inpatient setting: a

2. BMGF. Krankenanstalten in Zahlen. 2006; Available 18. Finkler SA, Knickman JR, Hendrickson G, Lipkin narrative review. J Crit Care 2004; 19 (4): 271–278.

from: http://www.kaz.bmgf.gv.at/. Last accessed: M, Jr, Thompson WG. A comparison of work-sam- 32. Wipf JE, Fihn SD, Callahan CM, Phillips CM. How

August 1, 2008. pling and time-and-motion techniques for studies residents spend their time in clinic and the effects of

3. Mechanic D. Physician discontent: challenges and in health services research. Health Serv Res 1993; 28 clerical support. J Gen Intern Med 1994; 9 (12):

opportunities. JAMA 2003; 290 (7): 941–946. (5): 577–597. 694–696.

4. Probst JC, Greenhouse DL, Selassie AW. Patient and 19. Mamlin JJ, Baker DH. Combined time-motion and 33. Bürkle T, Kuch R, Prokosch HU, Dudeck J. Stepwise

physician satisfaction with an outpatient care visit. J work sampling study in a general medicine clinic. Evaluation of Information Systems in an University

Fam Pract 1997; 45 (5): 418–425. Med Care 1973; 11 (5): 449–456. Hospital. Methods Inf Med 1999; 38 (1): 9–15.

5. Brettenthaler R, Mayer H. Stopp der Zettel- 20. Sittig DF. Work Sampling: A Statistical Approach to 34. Westbrook JI, Ampt A, Williamson M, Nguyen K,

wirtschaft – Bürokratie macht krank [stop paper Evaluation of the Effect of Computers on Work Pat- Kearney L. Methods for measuring the impact of

chaos – bureaucracy makes sick]. 2007. Available terns in The Healthcare Industry. Methods Inf Med health information technologies on clinicans’

from: http://www.buerokratiestopp.at/statements. 1993; 32 (2): 167–174. patterns of works and communication. In: Kuhn K,

html. Last accessed: August 1, 2008. 21. Lechleitner G, Pfeiffer K-P, Wilhelmy I, Ball M. Warren J, Leong T-Y, editors. Medinfo 2007 – Pro-

6. Mayer H. Spitalsärztinnen in Österreich 2006. Cerner Millenium: The Innsbruck Experience. ceedings of the 12th World Congress on Health

Ergebnis der Befragung für die Bundeskurie Methods Inf Med 2003; 42 (1): 8–15. (Medical) Informatics, Brisbane, August 20–24,

Angestellte Ärzte der österreichischen Ärzte- 22. Blum K, Müller U. Dokumentationsaufwand im 2007. Amsterdam: IOS Press; 2007. pp 1083–1087.

kammer. Österreichische Ärztekammer; 2006. Ärztlichen Dienst der Krankenhäuser – Bestands-

© Schattauer 2009 Methods Inf Med 1/200990 E. Ammenwerth; H.-P. Spötl: The Time Needed for Clinical Documentation versus Direct Patient Care

Appendix

Classification System Used for Analysis of Physician´s Activities

No. Name of Category Definition of Category

I Direct patient care

I.1 Medical activities Any diagnostic and therapeutic activity of the physician, related to the care of a patient

I.2 Communication with patients Direct conversation between the physician and patient

I.3 Waiting for a patient Physician is waiting for the next patient to arrive

I.4 Read in patient record Get information on the patient from the patient record

I.5 Other direct patient care Other activities of direct patient care

II Communication

II.1 Personal communication with physicians Direct conversation with other physicians

II.2 Personal communication with non-physicians Direct conversation with health care professionals other than physicians (for example,

nurses, co-therapists)

II.3 Personal communication with relatives Direct conversation with family members of a patient

II.4 Phone calls Phone calls with other health care providers (excluding phone calls for patient-related

scheduling)

II.5 Communication for scheduling Organization (mostly by phone calls) of patient-related appointments (such as diagnostic

or therapeutic examinations, next inpatient admission)

II.6 Electronic communication Use of e-mail, Intranet, and Internet

II.7 Regular meetings Any meetings that take place at a predefined time

II.8 Other communications Any other communication activities

III Clinical documentation

III.1 Documentation of the initial examination Documentation of the initial examination of a patient after his admission to the hospital

III.2 Ongoing clinical documentation Any written entries in the patient record, such as clinical notes (for example, during ward

rounds)

III.3 Documentation of findings Filing or copying of recent findings (such as lab or x-ray reports) into the patient record

III.4 Writing of preliminary discharge letter Writing of the preliminary discharge letter upon the discharge of the patient from the hospital

III.5 Writing of final discharge letter Writing of the final discharge letter, including the correction process and transport time

III.6 Writing of consultation letters Writing of a consultation letter for other departments

III.7 Documentation of medication Documentation of the prescribed drugs of a patient and of any changes to prescriptions

III.8 Preparation of documentation forms Prepare weekly documentation forms for a patient (for example, for care planning and care

documentation)

III.9 Preparation of the forms for order entry Order diagnostic or therapeutic procedures using predefined forms

III 10 Writing of prescriptions Filling-out paper-based prescription forms for a patient that is going to be discharged

III.11 Other clinical documentation Any other documentation related to a patient

IV Administrative documentation

IV.1 Coding of the diagnosis and services Documentation and coding of the diagnoses and services for accounting and legal reasons

IV.2 Completing of transportation orders Completing of a transportation order form for a patient

IV.3 Writing of doctors’ certificates Writing of any patient-related certificates (for example, inability to work)

IV.4 Documentation for external quality manage- Documentation of data for any quality reports

ment

IV.5 Documentation of the working time Personal documentation of the daily hours of work

Methods Inf Med 1/2009 © Schattauer 2009E. Ammenwerth; H.-P. Spötl: The Time Needed for Clinical Documentation versus Direct Patient Care 91

Appendix

Classification System Used for Analysis of Physician´s Activities (continued)

No. Name of Category Definition of Category

IV.6 Generation of departmental statistics Development and update of departmental-oriented statistics related to patient care

IV.7 Generation of duty rosters Development and update of departmental duty rosters for the clinical staff

IV.8 Writing of discharge documents Finalization of the administrative discharge documents of a patient

IV.9 Writing of requests Prepare patient-oriented applications for example, for rehabilitation, aftercare, nursing care, or

further hospitalization

IV.10 Other administrative documentation Any other administrative documentation

V Other activities

V.1 Walking times Physician walking between rooms, departments, etc.

V.2 Breaks Any breaks

V.3 Other Any other activities (for example, private phone calls)

© Schattauer 2009 Methods Inf Med 1/2009You can also read