The Terrorist Attack on Utøya Island: Long-Term Impact on Survivors' Health and Implications for Policy - Universiteit Leiden

←

→

Page content transcription

If your browser does not render page correctly, please read the page content below

PERSPECTIVES ON TERRORISM Volume 15, Issue 3 The Terrorist Attack on Utøya Island: Long-Term Impact on Survivors’ Health and Implications for Policy by Kristin Alve Glad, Synne Øien Stensland, Grete Dyb Abstract In this article, we summarize some of the main findings from The Utøya Study, a comprehensive longitudinal study on the impact on the survivors of the July 22 Utøya Island terrorist attack, and describe some implications for future policy. In total, 398 (79%) of the survivors participated in one or more of the four data collections in the study. Their mean age at the time of the terrorist attack was 19.2 years (SD=4.3, range 13.1–56.7, 94.0% < 26 years of age), and 49.0% were female. The vast majority (88.9%) were of Norwegian origin. Participants were interviewed face-to-face at 4-5 months (T1), 14-15 months (T2), 30-32 months (T3), and 8.5 years (T4), post-attack. We found that the terrorist attack had negative repercussions for the survivors’ mental and somatic health for years after the attack, including symptoms of posttraumatic stress, anxiety, depression, complicated grief, headache, and other somatic symptoms. Exposure to the attack also led to long-term functional impairment for many, particularly in relation to the survivors’ academic performance and well-being at school. Furthermore, it had negative health consequences for people close to the survivors, such as their caregivers. An important factor associated with how survivors cope after a terrorist attack is the support and help they receive from their social network, but also from the health care system. In line with the national health outreach plan, most survivors had received early proactive outreach from their municipality, but many missed a broader and longer lasting follow-up. The comprehensive documentation of short- and long-term health and social consequences in this study underlines the challenges societies are faced with after terrorist attacks. This insight calls for actions from decision makers in providing adequate outreach programs in health and social services. In particular, survivors with a non- Norwegian origin reported higher levels of PTSD symptoms and were less satisfied with the follow-up. After future attacks, the official outreach should be proactive, long lasting, and consider the diverse needs and characteristics of the affected individuals. For example, there should be a particular focus on survivors with a minority background. Furthermore, the outreach should be broad, and include people in the survivors’ immediate social network, schools and workplaces. Keywords: Mental health, Norway, public policy, PTSD, somatic health, terrorist attack, Utøya, victims of terrorism, young survivors Introduction Terrorist attacks are acts of violence intended to attain a political, economic, religious, or social goal through provoking widespread, collective fear and insecurity.[1,2] Over the past decades, terrorist attacks have become a severe and concerning threat to societies and individuals in many parts of the world.[3] From the trauma literature, it appears that the malicious human intent and unpredictable nature of terrorist attacks may result in particularly adverse outcomes for those affected, including high risk of serious health problems.[4] In this article, we will first outline some potential consequences of being directly exposed to a terrorist attack, with a particular focus on survivors’ mental and somatic health, and their daily functioning. Subsequently, we will briefly describe the terrorist attack that targeted politically active youth on Utøya Island, Norway, on July 22, 2011. Then we will describe the comprehensive longitudinal interview study we designed to explore the impact of the attack and sum up some of our main findings regarding the health and functioning of the young survivors. Finally, we discuss how the new knowledge gained can help decision makers provide necessary health care and follow-up in the aftermath of future terrorist attacks. ISSN 2334-3745 60 June 2021

PERSPECTIVES ON TERRORISM Volume 15, Issue 3 Potential Consequences of Terrorist Attacks for Survivors Impact on Survivors’ Mental Health The most studied mental disorder that can develop after exposure to a traumatic event, such as a terrorist attack, is posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Characteristic symptoms of PTSD are re-experiencing the event as if it is happening again, including intrusive thoughts and images of the event, nightmares, and flashbacks; efforts to avoid stimuli associated with the trauma, including places or thoughts reminding of the event; and increased arousal, which often results in sleep disturbances, poor concentration, an exaggerated startle response, and irritability. Some may also experience negative changes in thoughts and feelings after the event, including their thoughts about the self (e.g., “I’m weak”) or the world (e.g., “Nowhere is safe”).[5] In a recent systematic review of the literature on PTSD among terrorist attack survivors, Garcia-Vera et al. (2016) found that as many as 33% to 39% of those directly exposed to life-threatening danger during a terrorist attack developed PTSD within the first year.[6] Furthermore, they found that 6 to 7 years after the attack, 15% to 26% still had PTSD. These findings demonstrate that many people are at risk of experiencing severe psychological reactions in the aftermath of a terrorist attack and that, for some, these reactions last for many years post-trauma. However, the large individual variation in post-trauma reactions raises important and difficult questions, including: “Why do we respond so differently to trauma?” and “What are the main factors that determine how we respond?” Extensive research on potential predictors for PTSD during the last 30 years has led to marked advances in our understanding of factors associated with elevated risk of this disorder. Such factors include individual characteristics (e.g., female gender, ethnic minority, low socio-economic status and psychiatric history), characteristics of exposure to the traumatic event (e.g., exposure intensity, bereavement, personal injury, perceived life threat), and post-trauma factors (e.g., low social support).[7] It has also been suggested that exposure to trauma reminders (i.e., cues that resemble the traumatic event and elicit distressing reactions) may play a superordinate role in PTSD, because it can trigger symptoms in all the PTSD symptom categories.[8] Furthermore, highly publicized disasters, such as a terrorist attack, can lead to considerable media attention on the survivors, which can be experienced as an extra strain.[9] Other well-known forms of psychopathology that terrorist attack survivors may experience are anxiety and depression.[10] For example, in a systematic review of the literature on major depressive disorder after terrorist attacks, Salguero et al. (2011) found that the risk of developing this disorder ranges between 20-30% among those directly exposed in the first few months after an attack.[11] Furthermore, given the brutal nature of such attacks, levels of mortality can be high. Whereas grief is a normal response to the loss of someone close, traumatic loss (e.g., by a terrorist attack) can lead to severe and persistent psychological reactions, such as symptoms of complicated grief. The hallmark of complicated grief is “persistent, intense yearning, longing and sadness, usually accompanied by insistent thoughts or images of the deceased and a sense of disbelief or an inability to accept the painful reality of the person’s death.”[12] While the dual burden of direct traumatization and traumatic loss is characteristic of terrorist attacks, few have explored the combined psychological consequences.[13] Impact on Survivors’ Somatic Health Through infliction of death, injury and destruction of physical and social environments, terrorist attacks may violate all aspects of survivors’ health—including their physical, mental and social well-being. Although these aspects of health are heavily entangled post-trauma, symptoms originating from or relating to the body (or soma) are commonly differentiated from those previously described, relating to the mind, soul, spirit or psyche.[14] In the aftermath of a terrorist attack, somatic symptomatology in survivors may result directly from exposure to a range of physical hazards, such as penetrating or blunt force, infectious, toxic or radioactive agents or irritants.[15-17] Among the survivors of the July 22 Utøya Island shooting, however, the most severe injuries were caused by gunshots, while survivors’ less severe injuries were largely related to falls incurred during flight. [18-20] Other than direct exposure to physical hazards during a terrorist attack, horrifying impressions can give rise to a range of individual somatic and behavioral stress responses.[21.22] Somatic symptoms, such as ISSN 2334-3745 61 June 2021

PERSPECTIVES ON TERRORISM Volume 15, Issue 3 headaches, pain, palpitations, insomnia or fatigue, are common in the early days and weeks post-trauma.[23] Such symptomatology has largely been understood as transient, normal reactions, without further need for follow-up.[24-26] On the other hand, long-term somatic complaints or illnesses have predominantly been seen as a sequela of persistent posttraumatic stress or PTSD.[27-29] However, results from large epidemiological studies indicate that frequent headache, pain, and other somatic symptoms contribute to considerable functional impairment.[30] It is likely that a high level of somatic symptoms and related functional impairment in the early phase post-trauma could compromise survivors’ capability to take on everyday tasks necessary for recovery, such as preparing and eating healthy meals, ensuring good sleep hygiene, and abstaining from overuse of pain medication and alcohol.[31] If the somatic symptoms experienced by survivors post-trauma are more impairing and persistent than previously understood, these could play an active role in hindering healthy recovery, not accounted for in current guidelines [32] and clinical practice. Impact on Survivors’ Daily Functioning Given the major impact that exposure to a terrorist attack may have on the survivors mental and somatic health, it is not surprising that it also can affect their daily functioning, such as their ability to do daily chores, their interests and activities, and how they get along with family and friends. The experience of terror can also impair the survivors’ academic performance and well-being in school. In a recent systematic review of the literature on school-related outcomes of trauma, Perfect et al. (2016) reported that many studies have found significant associations between trauma exposure and related PTSD symptoms among youth and impaired cognitive functioning, lower academic performance, and social-emotional-behavioral problems.[33] Clearly, such outcomes may have detrimental, long-lasting impact on young trauma survivors’ lives, for example in terms of their future career. Social Support and Follow-up An important factor associated with how survivors cope after a terrorist attack is the support and help they receive from their social network, as well as from the health care system. In societies enduring terrorist attacks, questions immediately arise as to how the attack will affect the bereaved, the survivors, their families and the community, and how authorities should respond. Unfortunately, findings from international studies on disasters, including 9/11, suggest that many affected do not receive the help they need from the public health care system.[34-36] We also know that many who are affected do not seek help when they need it.[37-38] As such, a proactive follow-up is recommended after large-scale disasters, such as a terrorist attack.[39] The Terrorist Attack on Utøya Island and the Outreach Program The Terrorist Attack On July 22, 2011, Anders Behring Breivik conducted two consecutive terrorist attacks in Norway. After having detonated a car bomb outside the government quarter in Oslo, killing nine people and injuring many more, while also causing immense material damage, the perpetrator moved to Utøya Island, 30 kilometers north of Oslo, where the Norwegian Labor Party was holding its annual youth summer camp. In total, 564 people were gathered on the island, mostly youths and young adults. For about one hour and twenty minutes, the perpetrator shot, killed and wounded those who crossed his path. Sixty-eight people were killed at Utøya Island, and 34 were hospitalized with physical injuries, of whom one died in the hospital.[40-42] Many more had minor injuries.[43] Numerous factors amplified the brutality of this attack. First, the youths were isolated on a small island of only 26 acres as the perpetrator hunted them down and shot them. They all heard gunshots and most hid or ran away from the terrorist as they realized they were in mortal danger. Their only chance to escape was to swim to the mainland, across the cold fjord, with the risk of drowning. Second, the survivors witnessed extreme trauma as many saw dead bodies and witnessed others being injured or killed. Third, the perpetrator was extremely brutal. He often shot the victims several times, and the mortality rate was high. Since the participants of the ISSN 2334-3745 62 June 2021

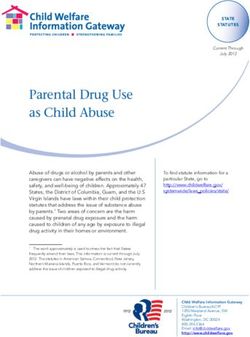

PERSPECTIVES ON TERRORISM Volume 15, Issue 3 summer camp had many friends and acquaintances on the island, most of them lost friends and/or family members in the attack. Finally, the perpetrator was disguised as a police officer, to lure the youths out of their hiding places. This left many with prolonged fear, as they did not know whom to trust when the first rescuers came to their aid.[44] During the next few days, the survivors returned to their homes and a national outreach program for affected families was implemented.[45] The National Outreach Program The Norwegian Directorate of Health advised affected municipalities on how to organize the health services and offer support to the directly affected families. Survivors and their families lived in municipalities across the entire country, and since the gravity of the massacres indicated that many would need follow-up over time, the outreach plan was anchored in the existing health services in the municipalities.[46] The outreach program was based on three main principles; proactivity in early outreach, continuity in responses, and targeted interventions for individuals in need. The crisis teams in the municipalities were required to establish early contact with the survivors and their families. The municipalities appointed a designated professional to serve as the “contact person” for the survivors and their families for at least the first year. The contact person was to make direct contact with the affected families, offer a personal meeting, and provide information about available help measures in the municipality and in the specialist health care services. The contact person was also expected to ensure a good and regular assessment of the victims’ functioning level, their access to social support, and any need for help. The aim was to ensure that all the directly affected survivors’ and close family members’ needs for services were identified and met.[47-48] The Utøya Study The Utøya Study is a comprehensive longitudinal interview study that commenced shortly after the terrorist attack on Utøya Island. The main aim of the study was to provide increased knowledge about how people exposed to terrorism react in the immediate aftermath, and to identify important predictors for their long- term responses. This is imperative for preparedness planning and the ability of health professionals to develop and provide efficient, evidence-based services following a terrorist attack. The study has been funded by the Norwegian Directorate of Health and consists of four data collection waves, conducted at 4-5 months (T1), 14- 15 months (T2), 30-32 months (T3), and 8 years (T4) after the July 22 attack. Methods According to police records, 495 people survived the massacre on Utøya Island. Five survivors were not invited to the study at T1 due to their young age (

PERSPECTIVES ON TERRORISM Volume 15, Issue 3

Figure 1: Overview of the Survivors (n = 399) who Participated in the Utøya Study

Total survivors

(n=502*)

Excluded: No

contact info (n=1)

< 13 years (n=4)

T1

Invited survivors

(n=497)

Opted out (n=3)

Declined/not reached (n=162)

T1

Participating survivors

(n=332)

Open cohorts

T2

Invited survivors

(n=494)

New participants T2 Opted out (n=6)

(n=30) Declined/not reached (n=197)

T2

Participating survivors

(n=291)

T3

Invited survivors

(n=362)

Closed cohort

Opted out (n=2)

Declined/not reached (n=94)

T3

Participating survivors

(n=266)

T4

Invited survivors

Open cohort

(n=498)

New participants T4 Opted out (n=1)

(n=36) Declined/not reached (n=208)

T4

Participating survivors

(n=289)

* 495 *were

495 were on island

on the the island duringthe

during theattack;

attack; 77 were

were on

onthe

themainland

mainland. In total, 398 (79%) of the 502 survivors

participated at one or more time point(s).

ISSN 2334-3745 64 June 2021PERSPECTIVES ON TERRORISM Volume 15, Issue 3

In each data wave, postal invitations describing the purpose of the study were sent to potential participants.

Interviews were performed in the participants’ home by health care personnel (mostly psychologists, medical

doctors, and nurses); these had been specially trained for the task. The interviews were audiotaped and lasted

approximately an hour and a half, with topics ranging from mental and physical health pre-and post-trauma, to

personal experiences with the media, and their post-trauma school performance. To measure the participants’

reactions to the attack, we used several validated measures. For example, to assess their level of PTSD symptoms,

we used the 20-item UCLA PTSD Reaction Index (PTSD-RI).[50,51] Because three items have two alternative

formulations, of which the highest score was applied to calculate the total score, the total symptom scale score

is made up of 17 items, corresponding with the DSM-IV criteria for PTSD.[52] Responses were recorded on

a 5-point Likert-scale, ranging from 0 (never) to 4 (most of the time), and possible total scores range from

0-68. A threshold score of 38 was used to determine likelihood of meeting the criteria for a PTSD diagnosis.

All measures used in the study are thoroughly described in relevant publications (see the Notes section of this

article). Of note, because the fourth data collection was only recently completed, most of the results presented

in this article are from publications based on data collected in the first three interview waves. The study was

approved by the Regional Committee for Medical and Health Research Ethics in Norway (REK 2011/1625 and

REK 2014/246).

Main Findings

The Utøya Island study has produced more than 50 peer reviewed papers and reports on topics ranging from the

survivors’ adverse mental and somatic health outcomes (including posttraumatic stress reactions, complicated

grief, migraines, other headache, pain and somatic symptomatology), to school functioning, experiences with

the media, and experiences with the outreach model.[53] In the following, we will summarize some of the main

findings from the study, with a particular focus on health and post-disaster follow-up.

Mental Health Reactions

We found that 47% of the survivors reported clinical levels of PTSD in the first wave, 4-5 months post-attack,

whereas 11% met the diagnostic criteria for full PTSD and 36% for partial PTSD (i.e., meeting criteria for only

two out of three PTSD symptom subcategories).[54] Survivors’ PTSD levels were more than six times higher

when compared to youth in the general population.[55] Furthermore, the number of survivors with clinical

levels of anxiety and depression was roughly 45% in the first wave, and about 30% and 25% in the second and

third wave, respectively.[56] In the fourth wave, a substantial minority of the survivors reported major mental

health symptoms and were still in need of health care services.[57]

In line with previous studies in the field, we found that significant predictors for the survivors’ level of PTSD

included female gender, minority ethnic status, high level of trauma exposure, current physical pain, the loss of

someone close, and low levels of social support.[58] Furthermore, physically injured survivors had increased

risk for later PTSD symptoms, as compared to non-injured.[59] Surprisingly, minor injuries—such as bruises,

a sprained or twisted ankle or broken leg—were related to particularly high levels of PTSD symptoms.[60] This

could imply that the presence of minor injuries in survivors may signal a high level of proximity and exposure

to the atrocities (i.e., urgent need to flight), and thereby increased risk of PTSD symptoms.[61] Feelings of

shame and guilt among the survivors were also uniquely and positively associated with their PTSD symptom

level.[62] In the second and third interview waves, we asked how often the survivors had experienced various

trauma reminders (i.e., sounds, visual experiences, emotions, bodily reactions, touch, smells, and situational

reminders) during the last month, and which one they perceived to be the worst.[63,64] In both waves, auditory

reminders—especially loud and sudden noises—was the type of trauma reminder that the survivors reported

experiencing most often, and the one they found to be the most distressing.

One survivor described it like this:

Sounds and bangs are uncomfortable, for example if I’m sitting in the library and I hear a bang

in the cafeteria, I become very alert. That’s something that I really cannot control. Then the

whole day… then I’m down the rest of the day, it affects my schoolwork and stuff like that.[65]

ISSN 2334-3745 65 June 2021PERSPECTIVES ON TERRORISM Volume 15, Issue 3

Of the 261 survivors who participated in the third interview wave, approximately 2.5 years post- attack, we

found that almost 90% had experienced one or more reminder during the month prior to the interview, and

about 20% said that they had experienced strong emotional reactions when they experienced their worst

reminder.[66] Survivors who met the diagnostic criteria for PTSD reported significantly higher frequency of

exposure to trauma reminders compared to survivors who did not meet the criteria for this disorder.

In sum, these findings suggest that many survivors were struggling with mental health reactions for a long-

time post-attack, that trauma reminders were common for years post-attack, and that PTSD is strongly related

to frequency of exposure to reminders.

Loss and Complicated Grief

Of the 355 survivors who participated at some point during the first three interview waves, 275 had lost

someone close (i.e., a family member, partner, and/or close friend) in the attack. We explored the longitudinal

association between symptoms of PTSD and complicated grief reactions among these young, bereaved

survivors.[67] As hypothesized, in all three interview waves we found that participants who reported higher

levels of complicated grief also reported higher levels of PTSD symptoms. From analyses of our longitudinal

data, we found that posttraumatic stress symptoms predicted complicated grief reactions, but not vice versa.

This supports the existing hypothesis that PTSD reactions may disrupt the mourning process and affect the

severity of complicated grief symptoms.[68,69]

Somatic Symptoms

Among the survivors, headaches, fatigue, and lumbar pain were the most frequently reported somatic symptoms

in the early phase post-trauma.[70] As headaches were the most frequent early complaint, known to commonly

cause considerable disability [71], we explored the effect of terror on risk of headache in a case control study

of the adolescent survivors as compared to matched controls.[72] The findings clearly showed that survivors

of the terrorist attack had a four times higher risk of weekly and daily migraines and tension type headaches in

comparison to a matching control group. Further, we investigated how somatic symptomatology overall—such

as headaches, stomachache, other musculoskeletal pain, palpitation, faintness and fatigue—relate to PTSD over

time.[73] To our surprise, we found that survivors’ early somatic symptoms predicted later posttraumatic stress

reactions. This finding is at odds with current theory and practice that assumes symptoms of PTSD precede the

development of adverse somatic health outcomes after trauma.[74-77] The present findings suggest that early

identification of survivor’s somatic symptoms and provision of adequate services may represent an untapped

potential to improve and increase the efficiency of post-trauma interventions.

Impaired Functioning

Almost half of the survivors reported that they found it very difficult to perform their everyday tasks,

and approximately 25% said they were less interested in the things they used to do before the attack.[78]

Furthermore, about 10% said that it had become much more difficult to get along with their family and friends.

[79] Many of the survivors were part-time or full-time students and we found that 61% reported impaired

academic performance and 29% reported impaired well-being in school.[80] In a qualitative interview of 65

students (aged 16–29 years), a majority of students (69%, n=45) reported negative changes in their academic

performance, particularly having difficulties in concentration and noticing a failure to remember what they

had just read.[81] For example, one girl in her final year of high school said:

Everything fell apart! It used to take me one minute to read a page, maybe half a minute. But

now I had to read the page over and over again. I spent 20 to 30 minutes on a page – I’m not

kidding. I just sat there staring at it, reading over and over, trying to make it stick. And in math

… well, I simply couldn’t concentrate (…) Everything went so slow. I used to have top grades,

and then I ended up with Cs. My plans for university were blown … just like that.[82]

ISSN 2334-3745 66 June 2021PERSPECTIVES ON TERRORISM Volume 15, Issue 3

These findings demonstrate both how exposure to a terrorist attack can negatively affect young survivors’

academic performance and well-being at school, and the potential long-lasting impact of this, in terms of their

future career. When asked to what extent they had resumed functioning normally in various life areas eight

years after the attack, two thirds of the survivors answered that they were back to normal in relation to school,

studies and work and/or in relation to family.[83] About 50% said they were completely back to normal in

their spare time and in relation to friends. The fact that so many reported that they are not back to functioning

normally almost a decade after the attack shows how long-lasting the impairment can be, and is, for many

survivors.

The Impact of Massive Media Attention

The Utøya survivors received considerable media attention after the attack. In fact, almost everyone who

participated in our study said that journalists had contacted them, and 88% had given interviews about their

experiences on Utøya.[84] We found that survivors who experienced their contact with the media as upsetting

had more symptoms of PTSD compared to survivors who did not. [85] At T3, we explored their personal

experiences with the media in more detail and analyzed written descriptions of positive or negative personal

media experiences of 235 survivors after the attack.[86] As many as 90% described negative experiences with

the way journalists’ approached them. A recurring theme was that the journalists had neither shown them

respect nor been considerate, but had been rather invasive. For example, one survivor stated:

My first encounter with the media was pretty negative. There was a meeting that day when the

entire press corps was outside and the camera flashes were going like crazy in the room where we

were trying to take care of each other and grieve. It annoyed me so much. (…) Basically, it was

rough that we didn’t even get 12 hours to process what had just happened.[87]

In relation to the interview situation, the journalists themselves were mostly described as both caring and

considerate, while their experiences with the media’s coverage of their story were more mixed. Positive

experiences included being pleased with the angle on the story or having been given the opportunity to read

the result of an interview prior to publication. Others reported negative experiences—e.g., that the angle

of their story had been excessively negative and dramatic, or that their story or picture had been published

without their consent. For some, it had been a burden to be recognized in public after being photographed by

journalists for the media.[88]

Social Support

It is generally known that one of the most important protective factors for people who have experienced

something traumatic is support from their social network, including family and friends.[89.90] In all four

waves of the study, most survivors reported that they had experienced a lot of support from the people around

them. However, in each wave, about 10% reported that they missed having people around them who cared

about them; someone to talk to about their problems, someone to be with, and someone who could give them

important advice.[91-94]

Unmet Healthcare Needs Despite Proactive Outreach

The Norwegian health authorities implemented a national outreach program to meet the health care needs of

citizens directly affected by the terrorist attack. For participants in our study, it seemed to have worked well

in the first phase after the attack.[95] For example, we found that 84% of the survivors reported that they had

been contacted by their contact person.[96] In addition, in a qualitative study where the authors of this article

explored how the caregivers of the survivors had experienced the follow-up, only few reported that they were

unaware that the health services proactively contacted their child who had been on the island during the attack.

[97] That said, the most salient theme in the caregiver’s interviews was a wish for a more active and enduring

follow-up, especially for siblings and the family as a whole.[98] For example, one mother stated:

I have missed help from the municipal crisis team beyond a single conversation. We have not

ISSN 2334-3745 67 June 2021PERSPECTIVES ON TERRORISM Volume 15, Issue 3

received follow-up locally – no one has contacted us as a family after the first week. We had to get

help ourselves and feel forgotten by the municipality![99]

Similarly, in a qualitative report on how the directly affected survivors themselves assessed the outreach from

the public health services, we found that many felt that the outreach disappeared too quickly, and that the

follow-up had not been proactive enough.[100] Furthermore, during the third interview wave (approximately

2.5 years after the attack), one in five survivors reported unmet needs for addressing their negative psychological

reactions, and one in seven for attack-related somatic health problems.[101] Unmet healthcare needs were

associated with higher levels of posttraumatic stress, depression/anxiety, somatic symptoms, and low social

support. Survivors with a non-Norwegian background were more likely to report unmet needs for attack-related

physical health problems. They were also less satisfied with the post-attack healthcare.[102] Of note, we also

found that the parents of the Utøya survivors experienced high levels of emotional distress following the attack,

including symptoms of posttraumatic stress, anxiety and depression, and that they developed a wide range of

healthcare needs.[103,104] Eight years post-attack, a substantial minority of caregivers still reported high levels

of PTSD symptoms.[105] These findings are in line with the limited literature in the field on reactions among

people in the immediate social network of the survivors. They also illustrate how caregivers may themselves

suffer severe emotional traumatization associated with a life threat to their children.[106-108]

How Can This Knowledge Improve Practice?

The terrorist attack on Utøya Island had long-term health implications for those directly affected, including

high levels of PTSD reactions, anxiety, depression, complicated grief, headaches, and other pain and somatic

symptoms. It also impacted the victims’ daily functioning, including their ability to study and their interpersonal

relationships. This impact on functioning may be caused by the psychological and physical consequences of the

trauma, but it can also be related to the lack of sufficient outreach from health and social services, and a lack of

support and understanding from schools, workplaces, families and friends. Based on these findings, we offer

the following suggestions for future policy.

The official recommendation after the July 22 terrorist attack in Norway was that the proactive follow-up should

last for one year. In retrospect, however, we see that many survivors struggled for several years after the attack,

and that the need for help therefore needs to be extended well beyond the first year. This is in line with findings

from a recent systematic study on PTSD following another terrorist attack.[109] As such, we recommend that a

core principle for follow-up after future major terrorist attacks should be long-term assistance and support. The

study also revealed that many survivors experienced a great need for help for their somatic reactions related to

the attack, even those who themselves were not physically injured. Current recommendations for preparedness

planning focus primarily on assessment and interventions targeting psychological symptoms. Current

guidelines should be revised to encompass identification and accommodation of survivors’ psychological and

somatic reactions and needs.[110]

After the Utøya attack, most of the outreach was concentrated on helping those who survived. However,

importantly—and in line with a recent systematic review on traumatic reactions following a terrorist attack—

we found that the people close to the directly affected, such as their caregivers, can themselves be traumatized

and develop post-trauma health problems.[111-113] As such, people in the immediate social network of the

survivors should be considered ‘affected’ in their own right and receive follow-up.[114] We also found that

survivors with a non-Norwegian origin reported higher levels of PTSD symptoms, and that they were less

satisfied with the follow-up, than those with a Norwegian background were.[115,116] Hence, after future

attacks, we recommend a particular focus on the follow-up of survivors with a minority background.

Exposure to a terrorist attack can be particularly detrimental for young survivors, as it may affect their

psychosocial development and education, with potential long-term adverse effects, including impaired

academic performance, spoiling future career opportunities. Given the long-term disruption and impairment

we found in the survivors’ academic performance after Utøya, it is important that appropriate school support

is provided after future attacks.[117,118] For example, greater educational follow-up by a teacher may offer a

ISSN 2334-3745 68 June 2021PERSPECTIVES ON TERRORISM Volume 15, Issue 3 good point of intervention with traumatized students.[119] The media coverage of a terrorist attack can be extensive and long lasting, but few have explored how media attention may affect survivors. Our results suggest that media exposure can be an extra strain for the survivors, particularly for those who are struggling post-attack. As such, journalists need to be careful and considerate when they approach, interview and report on people exposed to trauma. In addition, survivors should be warned about the media attention they may receive – and be briefed on how to handle it. Conclusion Terrorist attacks are traumatic events that violate security and feelings of safety. The prevalence of post- traumatic stress reactions, other mental and somatic health problems, and negative social consequences are often substantial among survivors. Recent research indicates that about 1/3 of those directly exposed to a threat against their own life during a terrorist attack develop PTSD the first year, and that many survivors struggle with these posttraumatic stress reactions 6-7 years after the attack.[120] The terrorist attack at Utøya Island on July 22, 2011, targeted politically active youth on a summer camp in an extremely brutal way. On this small island the victims were exposed to a heavily armed perpetrator, who killed 69 people. The survivors quickly realized their lives were in danger, and they witnessed extreme trauma, including exposure to the sight of dead bodies and others being injured or dying. The Utøya Study is a comprehensive longitudinal interview study designed to explore the impact of this attack on the survivors and their parents. As summed up in this article, 47% of the survivors had posttraumatic stress reactions on a clinical level 4-5 months after the event. For many, these reactions and other psychological problems lasted for many years. The need for using mental health services was substantial, and about 70% required specialized mental health services during the first years. Grief about the loss of friends was complicated by their posttraumatic reactions; it interfered with their own healing process. Pain and other somatic symptoms were common and appeared to also complicate recovery from psychological problems. The results of our study underline the challenges survivors and their families are confronted with after terrorist attacks. Our study’s findings calls for action from decision makers in providing adequate outreach programs in health and social services. To successfully improve readiness and respond adequately to victims’ needs after terrorist attacks, disaster guidelines and future outreach programs must integrate empirically based knowledge. Therefore, ensuring a systematic need-based response to terrorist attacks and other disasters over time requires integration of real-time research in preparedness planning. Post-attack outreach should be proactive, long lasting, and consider the diverse needs and characteristics of the affected individuals. For example, there should be a particular focus on survivors with a minority background. Furthermore, the outreach should be broad, and include people in the victims’ immediate social network, schools and workplaces. Acknowledgments We sincerely thank everyone who participated in The Utøya Study. About the Authors: Kristin Alve Glad, Ph.D., is a clinical psychologist. She holds a bachelor of arts (psychology) from Trinity College Dublin, and did her master’s degree and Ph.D. in psychology at the University of Oslo. Dr. Glad has been affiliated with the Norwegian Centre on Violence and Traumatic Stress since 2005 and has published a number of reports, book chapters and research papers. She is currently working as a researcher on “The Utøya Study” exploring the reactions among survivors directly exposed to the terrorist attack and their caregivers. Synne Øien Stensland, M.D., Ph.D., is a pediatrician and works as a researcher at the Norwegian Centre for Violence and Traumatic Stress Studies and the Research and Communication Unit for Musculoskeletal ISSN 2334-3745 69 June 2021

PERSPECTIVES ON TERRORISM Volume 15, Issue 3

Health (FORMI), Oslo University Hospital (OUS), Norway. As co-chair of “The Utøya Study”, she is conducting

longitudinal research projects on survivors and families of the 22 July 2011 massacre. She was trained as

pediatrician, and has worked for years as a clinician in hospitals and outpatient units. Her interest in children

and adolescents’ somatic health related to childhood trauma and posttraumatic stress reactions has resulted in

research on youth and young adults exposed to traumatic events such as child sexual abuse, violence, bullying

and disasters. Dr. Stensland has contributed to national guidelines, published book chapters and research papers.

She is supervising a number of doctoral and post doc students and currently serves as treasurer for the Executive

Committee of the International Society of Traumatic Stress Studies (ISTSS).

Grete Dyb, M.D., Ph.D, is a Child and Adolescent Psychiatrist and Professor at the Faculty of Medicine,

University of Oslo and Head of Research at the Norwegian Centre for Violence and Traumatic Stress Studies.

As the principal researcher of “The Utøya Study”, she is conducting longitudinal research projects on survivors

and families of the massacre. She was trained in child and adolescent psychiatry, and worked for many years as

a clinician in hospitals and outpatient units. Her special interest in childhood trauma and posttraumatic stress

reactions in children and youth has also resulted in research on children youth and families exposed to traumatic

events such as child sexual abuse, violence, accidents and disasters. She has 228 publications listed in Cristin

(https://app.cristin.no/persons/show.jsf?id=16243) within the field of childhood trauma, disasters, terror attacks

and the impact of trauma on mental health in children, adolescents and adults. She has supervised Bachelor,

Master, Ph.D. and post-doctoral students since 1992. She recently served for six years at the International Society

of Traumatic Stress Studies [ISTSS] Board of Directors and served in 2016 as its President.

Notes

[1] Butler, A. S., Panzer, A. M., & Goldfrank, L. R. (2003). “Understanding the Psychological Consequences of Traumatic Events,

Disasters, and Terrorism,” in A. S., Butler, A. M., Panzer, & L. R. Goldfrank (2003). Preparing for the Psychological Consequences

of Terrorism: A Public Health Strategy. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

[2] START (2020). Global Terrorism Database. Retrieved 16th of December, 2020; URL: https://www.start.umd.edu/gtd

[3] García-Vera, M. P., Sanz, J., & Gutiérrez, S. (2016). “A Systematic Review of the Literature on Posttraumatic Stress Disorder in

Victims of Terrorist Attacks,” Psychological Reports, 119(1), pp. 328-359. DOI:10.1177/0033294116658243

[4] Norris, F. H., Friedman, M. J., & Watson, P. J. (2002). “60,000 Disaster Victims Speak: Part II: Summary and Implications of the

Disaster Mental Health Research,” Psychiatry, 65(3), pp. 240-260.

[5]American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders: DSM-5 (Fifth edition. ed.).

Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association.

[6] García-Vera, M. P., et al. (2016). op.cit.

[7] For a review, see: Tortella-Feliu, M., Fullana, M. A., Pérez-Vigil, A., Torres, X., Chamorro, J., Littarelli, S. A., Ioannidis, P. J. P.

A. (2019). “Risk Factors for Posttraumatic Stress Disorder: An Umbrella Review of Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses,”

Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews, 107, pp. 154-165. DOI:10.1016/j.neubiorev.2019.09.013

[8] Pynoos, R.S., Steinberg, A.M., Layne, C.M., Briggs, E.C., Ostrowski, S.A., & Fairbank, J.A. (2009). “DSM-V PTSD Diagnostic

Criteria for Children and Adolescents: A Developmental Perspective and Recommendations,” Journal of Traumatic Stress, 22(5),

pp. 391-398.

[9] E.g., Doohan, I., & Saveman, B.-I. (2013). “Impact of Life After a Major Bus Crash: A Qualitative Study Of Survivors’ Experiences,”

Scandinavian Journal of Caring Sciences, 28(1): pp. 155-163.

[10] Thabet, A. M., Thabet, S. S., & Vostanis, P. (2016). “The Relationship Between War Trauma, PTSD, Depression, and Anxiety

Among Palestinian Children in the Gaza Strip,” Health Science Journal, 10(5), p. 1.

[11] Salguero, J.M., Fernández-Berrocal, P., Iruarrizaga, I., et al. (2011). “Major Depressive Disorder Following Terrorist Attacks: A

Systematic Review of Prevalence, Course and Correlates,” BMC Psychiatry, 11, p. 96.

[12] Shear, M. K. (2015). “Complicated Grief,” The New England Journal of Medicine, 372(2), pp. 153-160 (citation from p. 154).

DOI:10.1056/NEJMcp1315618

[13] Neria, Y., & Litz, B. T. (2003). “Bereavement by Traumatic Means: The Complex Synergy of Trauma and Grief,” Journal of Loss

and Trauma, 9, pp. 73-87.

ISSN 2334-3745 70 June 2021PERSPECTIVES ON TERRORISM Volume 15, Issue 3 [14] Asmundson, G. J. G., & Katz, J. (2009). “Understanding the Co-occurrence of Anxiety Disorders and Chronic Pain: State-of- the-Art,” Depression and Anxiety, 26(10), pp. 888-901. [15] Lippmann, M., Cohen, M. D., & Chen, L. C. (2015). “Health Effects of World Trade Center (WTC) Dust: An Unprecedented Disaster’s Inadequate Risk Management,” Critical Reviews in Toxicology, 45(6), pp. 492-530. DOI:10.3109/10408444.2015.10446 01 [16] Lucchini, R. G., Hashim, D., Acquilla, S., Basanets, A., Bertazzi, P. A., Bushmanov, A., Todd, A. C. (2017). “A Comparative Assessment of Major International Disasters: The Need for Exposure Assessment, Systematic Emergency Preparedness, and Lifetime Health Care,” BMC Public Health, 17(1), p. 46. DOI:10.1186/s12889-016-3939-3 [17] Neria, Y., Wickramaratne, P., Olfson, M., Gameroff, M. J., Pilowsky, D. J., Lantigua, R., Weissman, M. M. (2013). “Mental and Physical Health Consequences of the September 11, 2001 (9/11) Attacks in Primary Care: A Longitudinal Study,” Journal of Traumatic Stress, 26(1), pp. 45-55. DOI:10.1002/jts.21767 [18] Gaarder, C., Jorgensen, J., Kolstadbraaten, K. M., Isaksen, K. S., Skattum, J., Rimstad, R., Naess, P. A. (2012). “The Twin Terrorist Attacks in Norway on July 22, 2011: The Trauma Center Response,” J Trauma Acute Care Surg, 73(1), pp. 269-275. DOI:10.1097/TA.0b013e31825a787f [19] Sollid, S. J., Rimstad, R., Rehn, M., Nakstad, A. R., Tomlinson, A. E., Strand, T., Collaborating, G. (2012). “Oslo Government District Bombing and Utøya Island Shooting July 22, 2011: The Immediate Prehospital Emergency Medical Service Response,” Scand J Trauma Resusc Emerg Med, 20, 3. DOI:10.1186/1757-7241-pp. 20-23. [20] Bugge, I., Dyb, G., Stensland, S. O., Ekeberg, O., Wentzel-Larsen, T., & Diseth, T. H. (2017). “Physical Injury and Somatic Complaints: The Mediating Role of Posttraumatic Stress Symptoms in Young Survivors of a Terror Attack,” Journal of Traumatic Stress. DOI:10.1002/jts.22191 [21] Schnurr, P. P., & Jankowski, M. K. (1999). “Physical Health and Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder: Review and Synthesis,” Seminars in Clinical Neuropsychiatry, 4(4), pp. 295-304. DOI:10.153/SCNP00400295 [22] Yehuda, R., Hoge, C. W., McFarlane, A. C., Vermetten, E., Lanius, R. A., Nievergelt, C. M., Hyman, S. E. (2015). “Post- Traumatic Stress Disorder,” Nat Rev Dis Primers, 1, p. 15057. DOI:10.1038/nrdp.2015.57 [23] Kizilhan, J. I., & Noll-Hussong, M. (2018). “Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder Among Former Islamic State Child Soldiers in Northern Iraq,” British Journal of Psychiatry, 213(1), 425-429. doi:10.1192/bjp.2018.88 [24] Goldmann, E., & Galea, S. (2014). “Mental Health Consequences of Disasters,” Annual Review of Public Health, 35, pp. 169- 183. DOI:10.1146/annurev-publhealth-032013-182435 [25] Bisson, J. I., Berliner, L., Cloitre, M., Forbes, D., Jensen, T. K., Lewis, C., Shapiro, F. (2019). “The International Society for Traumatic Stress Studies New Guidelines for the Prevention and Treatment of Posttraumatic Stress Disorder: Methodology and Development Process,” Journal of Traumatic Stress, 32(4), 475-483. DOI:10.1002/jts.22421 [26] Koenen, K. C., Sumner, J. A., Gilsanz, P., Glymour, M. M., Ratanatharathorn, A., Rimm, E. B., Kubzansky, L. D. (2017). “Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder and Cardiometabolic Disease: Improving Causal Inference to Inform Practice,” Psychological Medicine, 47(2), pp. 209-225. DOI:10.1017/S0033291716002294 [27] Ibid. [28] Pacella, M. L., Hruska, B., & Delahanty, D. L. (2013). “The Physical Health Consequences of PTSD and PTSD Symptoms: A Meta-Analytic Review,” Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 27(1), pp. 33-46. DOI:10.1016/j.janxdis.2012.08.004 [29] Schnurr, P. P., & Jankowski, M. K. (1999). op. cit. [30] Mokdad, A. H., Forouzanfar, M. H., Daoud, F., Mokdad, A. A., El Bcheraoui, C., Moradi-Lakeh, M.,Murray, C. J. (2016). “Global Burden of Diseases, Injuries, and Risk Factors for Young People’s Health During 1990-2013: A Systematic Analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013,” Lancet, 387(10036), pp. 2383-2401. DOI:10.1016/s0140-6736(16)00648-6 [31] Bilevicius, E., Sommer, J. L., Asmundson, G. J. G., & El-Gabalawy, R. (2018). “Posttraumatic Stress Disorder and Chronic Pain are Associated with Opioid Use Disorder: Results from a 2012-2013 American Nationally Representative Survey,” Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 188, pp. 119-125. DOI:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2018.04.005 [32] Bisson, J. I., et al. (2019). op. cit. [33] Perfect, M., Turley, M., Carlson, J., Yohanna, J., & Saint Gilles, M. (2016). “School-Related Outcomes of Traumatic Event Exposure and Traumatic Stress Symptoms in Students: A Systematic Review of Research from 1990 to 2015,” School Psychology Quarterly, 33(1), pp. 30–43. URL: https://doi.org/10.1037/spq0000244 [34] DeLisi, L. E., Maurizio, A., Yost, M., Papparozzi, C. F., Fulchino, C., Katz, C. L., et al. (2003). “A Survey of New Yorkers after the September 11, 2001, Terrorist Attacks,” American Journal of Psychiatry, 160(4), pp. 780-3. [35] Norris, F. H., et al. op. cit. ISSN 2334-3745 71 June 2021

PERSPECTIVES ON TERRORISM Volume 15, Issue 3 [36] Stuber, J., Galea, S., Boscarino, J. A., & Schlesinger, M. (2006). “Was There Unmet Mental Health Need after the September 11, 2001 Terrorist Attacks?” Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 41, pp. 230-240. [37] Schwart, E. D., & Kowalski, J. M. (1992). “Malignant Memories. Reluctance to Utilize Mental Health Services After a Disaster,” Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 180, pp. 767-772. [38] Weiseth, L. (2001). “Acute Posttraumatic Stress: Non-Acceptance of Early Intervention,” Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 62(17), pp. 35-40. [39] Brewin, C. R., Scragg, P., Robertson, M., Thompson, M., d’Ardenne, P., & Ehlers, A. (2008). “Promoting Mental Health Following the London Bombings: A Screen and Treat Approach,” Journal of Traumatic Stress, 21(1), pp. 3-8. [40] Bugge, I., et al. (2017). op. cit. [41] Gaarder, C., et al. (2012). op. cit. [42] Jorgensen, J. J., Naess, P. A., & Gaarder, C. (2016). “Injuries Caused by Fragmenting Rifle Ammunition,” Injury, 47(9), pp. 1951-1954. DOI:10.1016/j.injury.2016.03.023 [43] Bugge, I., Dyb, G., Stensland, S. O., Ekeberg, O., Wentzel-Larsen, T., & Diseth, T. H. (2015). “Physical Injury and Posttraumatic Stress Reactions. A Study of the Survivors of the 2011 Shooting Massacre on Utøya Island, Norway,” Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 79(5), 384-390. DOI:10.1016/j.jpsychores.2015.09.005 [44] Filkukova, P., Hafstad, G. S., & Jensen, T. K. (2016). “Who Can I Trust? Extended Fear During and After the Utøya Terrorist Attack,” Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, 8(4), pp. 512-519. DOI:10.1037/tra0000141 [45] Dyb, G., Jensen, T., Glad, K. A., Nygaard, E. & Thoresen, S. (2014). “Early Outreach to Survivors of the Shootings in Norway on the 22nd of July 2011,” European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 5:1. URL: https://doi.org/10.3402/ejpt.v5.23523 [46] Jensen, T. K., Stene, L., Nilsen, L., Haga, J. M., & Dyb, G. (2019). “Tidlig intervensjon og behandling,” in G. Dyb & T. K. Jensen (Ed.). Å leve videre etter katastrofen, Oslo: Gyldendal, pp141-163. [47] Dyb, G., et al. (2014). op. cit. [48] The Norwegian Directorate of Health, 2011: Helsedirektoratet (2011) Råd for oppfølging av rammede etter hendelsene på Utøya 22.07.2011. Retrieved 20. June, 2013; URL: http://helsedirektoratet.no/helse-og-omsorgstjenester/oppfolging-etter-22-7/ Documents/rad-for-oppfolging.pdf [49] Stene, L. E., & Dyb, G. (2016). “Research Participation After Terrorism: An Open Cohort Study of Survivors and Parents After the 2011 Utøya Attack in Norway,” BMC Research Notes, 9(57). URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/s13104-016-1873-1 [50] Pynoos, R., Rodriguez, N., Steinberg, A., Stuber, M., & Frederick, C. (1998). UCLA PTSD Index for DSM-IV. Los Angles: UCLA Trauma Psychiatry Program. [51] Steinberg, A., Brymer, M., Decker, K., & Pynoos, R. (2004). “The University of California at Los Angeles Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder Reaction Index,” Current Psychiatry Reports, 6(2), 96-100. DOI:10.1007/s11920-004-0048-2 [52] American Psychiatric Association. (1994). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders : DSM-IV (4th ed.). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association. [53] NKVTS, 2021 (2021, 01, 27). Utøyastudien. Website. https://www.nkvts.no/utoya/ [54] Dyb, G., Jensen, T. K., Nygaard, E., Ekeberg, Ø., Diseth, T. H., Wentzel-Larsen, T., & Thoresen, S. (2014). “Post-Traumatic Stress Reactions in Survivors of the 2011 Massacre on Utøya Island, Norway,” British Journal of Psychiatry, 204, pp. 361-367. [55] Ibid. [56] Stene, L. E., Wentzel-Larsen, T., & Dyb, G. (2016). “Healthcare Needs, Experiences and Satisfaction After Terrorism: A Longitudinal Study of Survivors from the Utøya Attack,” Frontiers in Psychology, 7:p.1809. URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.3389/ fpsyg.2016.01809 [57] Dyb, G., Stensland, S., Porcheret, K., & Wentzel-Larsen, T. (work in progress). “Posttraumatic Stress Reactions 8.5 Years After the 2011 Utøya Island Terrorist Attack.” [58] Dyb, G., et al. (2014), op.cit. [59] Bugge, I., et al. (2017), op. cit. [60] Bugge, I., et al. (2015), op. cit. [61] Bugge, I., et al. (2017)., op. cit. [62] Aakvaag, H. F., Thoresen, S., Wentzel‐Larsen, T., Røysamb, E., & Dyb, G. (2014). “Shame and Guilt in the Aftermath of Terror: The Utøya Island Study,” Journal of Traumatic Stress, 27(5), pp. 618-621. DOI:10.1002/jts.21957 ISSN 2334-3745 72 June 2021

PERSPECTIVES ON TERRORISM Volume 15, Issue 3 [63] Glad, K. A., Jensen, T. K., Hafstad, G. S., & Dyb, G. (2016). “Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder and Exposure to Trauma Reminders After a Terrorist Attack,” Journal of Trauma & Dissociation, 17(4), pp. 435-447. DOI:10.1080/15299732.2015.112677 7 [64] Glad, K. A., Hafstad, G. S., Jensen, T. K., & Dyb, G. (2017). “A Longitudinal Study of Psychological Distress and Exposure to Trauma Reminders After Terrorism,” Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, 9, pp. 145-152. URL: http:// dx.doi.org/10.1037/tra0000224 [65] Ibid. p.148. [66] Ibid. [67] Glad, K. A., Stensland, S.O., Czajkowski, N. O., Boelen, P. A., Dyb, G. (in press). “The Longitudinal Association Between Symptoms of Posttraumatic Stress and Complicated Grief. A Random Intercepts Cross-Lag Analysis,” Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy. [68] Nakajima, S., Ito, M., Shirai, A., & Konishi, T. (2012). Complicated Grief in Those Bereaved by Violent Death: The Effects of Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder on Complicated Grief,” Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience, 14, pp. 210-214. [69] Schaal, S., Jacob, N., Dusingizemungu, J.-P., & Elbert, T. (2010). “Rates and Risks for Prolonged Grief Disorder in a Sample of Orphaned and Widowed Genocide Survivors,” BMC Psychiatry, 10(55). [70] Stensland, S. O., Thoresen, S., Jensen, T., Wentzel-Larsen, T., & Dyb, G. (2020). “Early Pain and Other Somatic Symptoms Predict Posttraumatic Stress Reactions in Survivors of Terrorist Attacks: The Longitudinal Utøya Cohort Study,” Journal of Traumatic Stress, 33(6), 1060-1070. DOI:10.1002/jts.22562 [71] Vos, T., Flaxman, A. D., Naghavi, M., Lozano, R., Michaud, C., Ezzati, M., Memish, Z. A. (2012). “Years Lived With Disability (Ylds) for 1160 Sequelae of 289 Diseases and Injuries 1990-2010: A Systematic Analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010,” Lancet, 380(9859), pp. 2163-2196. DOI:10.1016/s0140-6736(12)61729-2 [72] Stensland, S. O., Zwart, J. A., Wentzel-Larsen, T., & Dyb, G. (2018). “The Headache of Terror: A Matched Cohort Study of Adolescents from the Utøya and the HUNT Study,” Neurology, 90(2), pp. e111-e118. DOI:10.1212/WNL.0000000000004805 [73] Stensland, S. O., et al. (2020), op.cit. [74] Andreski, P., Chilcoat, H., & Breslau, N. (1998). “Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder and Somatization Symptoms: A Prospective Study,” Psychiatry Research, 79(2), pp. 131-138. URL: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9705051 [75] McLaughlin, K. A., Basu, A., Walsh, K., Slopen, N., Sumner, J. A., Koenen, K. C., & Keyes, K. M. (2016). “Childhood Exposure to Violence and Chronic Physical Conditions in a National Sample of U.S. Adolescents,” Psychosomatic Medicine, 78(9), pp. 1072-1083. DOI:10.1097/psy.0000000000000366 [76] Pacella, M. L., et al. (2013), op. cit. [77] Schnurr, P. P., & Jankowski, M. K. (1999), op. cit. [78] Glad, K. A., Aadnanes, M., & Dyb, G. (2012). “Opplevelser og reaksjoner hos de som var på Utøya 22. Juli 2011.” Deloppsummering nr. 1 fra prosjektgruppen. NKVTS. [79] I [80] Stene, L. E., Schultz, J. H., & Dyb, G. (2018). “Returning to School After a Terror Attack: A Longitudinal Study of School Functioning and Health in Terror-Exposed Youth,” European Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, pp. 1-10. URL: http://dx.doi. org/10.1007/s00787-018-1196-y [81] Schultz, J-H., & Skarstein, D. (2020). “I’m Not as Bright as I Used to Be – Pupils’ Meaning-Making of Reduced Academic Performance After Trauma,” International Journal of School & Educational Psychology. DOI: 10.1080/21683603.2020.1837698 [82] Ibid. p.5. [83] Dyb, G., et al. (work in progress). op.cit. [84] Thoresen, S., Jensen, T. K., & Dyb, G. (2014). “Media Participation and Mental Health in Terrorist Attack Survivors,” Journal of Traumatic Stress, 27(6), pp. 639-646. URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/jts.21971 [85] Ibid. [86] Glad, K. A., Thoresen, S., Hafstad, G. S., & Dyb, G. (2018). “Survivors Report Back. Young People Reflect on Their Media Experiences After a Terrorist Attack,” Journalism Studies, 19(11), pp. 1652-1668. URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/146167 0X.2017.1291313 [87] Ibid. p.7. [88] Ibid. ISSN 2334-3745 73 June 2021

You can also read