The Role of Friends' Appearance and Behavior on Evaluations of Individuals on Facebook: Are We Known by the Company We Keep?

←

→

Page content transcription

If your browser does not render page correctly, please read the page content below

Human Communication Research ISSN 0360-3989

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

The Role of Friends’ Appearance and

Behavior on Evaluations of Individuals

on Facebook: Are We Known by the

Company We Keep?

Joseph B. Waltherl,2, Brandon Van Der Heide2, Sang-Yeon Kim2,

David Westerman3, & Stephanie Tom Tong2

1 Department of Telecommunication, Information Studies & Media, Michigan State University, East Lansing,

MI 48824

2 Department of Communication, Michigan State University, East Lansing, MI 48824

3 Department of Communication Studies, West Virginia University, Morgantown, WV 26506

This research explores how cues deposited by social partners onto one’s online network-

ing profile affect observers’ impressions of the profile owner. An experiment tested the

relationships between both (a) what one’s associates say about a person on a social net-

work site via ‘‘wall postings,’’ where friends leave public messages, and (b) the physical

attractiveness of one’s associates reflected in the photos that accompany their wall post-

ings on the attractiveness and credibility observers attribute to the target profile owner.

Results indicated that profile owners’ friends’ attractiveness affected their own in an

assimilative pattern. Favorable or unfavorable statements about the targets interacted

with target gender: Negatively valenced messages about certain moral behaviors

increased male profile owners’ perceived physical attractiveness, although they caused

females to be viewed as less attractive.

doi:10.1111/j.1468-2958.2007.00312.x

Forming and managing impressions is a fundamental process, and one that has been

complicated by new communication technologies. As computer-mediated commu-

nication (CMC) has diffused, successive technological variations raise new questions

about interpersonal impressions. For example, with people meeting via text-based

CMC—e-mail, discussion groups, or chat spaces of various kinds—a variety of

questions arose about impression formation and management. These included

whether and at what rate impressions are formed online (Walther, 1993), how online

impressions may be like or unlike offline impressions (Jacobson, 1999), and how

people judge the authenticity of self-presentation online (Donath, 1999). With fur-

ther developments of Internet-hosted technologies, however, people can garner

Corresponding author: Joseph B. Walther; e-mail: jwalther@msu.edu

28 Human Communication Research 34 (2008) 28–49 ª 2008 International Communication AssociationJ. B. Walther et al. Facebook Friends and Individual Evaluations

information about one another in other ways than direct online give-and-take.

As Ramirez, Walther, Burgoon, and Sunnafrank (2002) noted, information seekers

can mine static repositories of individuals’ prior interactions or deliberate profiles in

archives of group discussions or in personal and institutional Web pages. Add to the

mix that many individuals are now ‘‘Googleable’’ and the possibilities grow. The

relative value of various kinds of online information may depend on the extent that

any item appears to be involuntarily associated with the person to whom it refers

(Walther & Parks, 2002).

The newest forms of online communication complicate matters in ways that are

unique with respect to the kinds of information they offer for observers to draw

impressions, and they raise different theoretical issues than those formerly applied to

interactive uncertainty reduction online. Social networking technologies, such as

Facebook (http://www.facebook.com), offer a blend of interactive and static features

in any one individual’s online ‘‘profile.’’ Moreover, what complicates these sites from

an impression formation perspective is that people other than the person about

whom the site is focused also contribute information to the site. Such postings

may or may not include secondhand descriptions about the target individual and

his or her conduct. More importantly, whereas postings by other people on one’s

own profile reflect the character of the individuals who made the postings, it is also

possible that observers’ reactions of those others may affect perceptions of the target

profile maker as well, even though the profile maker his- or herself did not initiate or

condone the postings. This makes participative social networking technologies dif-

ferent from Web pages, e-mail, or online chat because all those technologies allow

the initiator complete control over what appears in association with his- or herself.

The possibility that individuals may be judged on the basis of others’ behaviors in

such spaces prompts this question: Are we known by the company we keep?

This research examined the question of how other individuals’ contributions to

one’s own online profile affect observers’ impressions and evaluations of the profile

maker. We discuss several approaches to impression formation online with respect to

personal characteristics and draw upon offline research specifically related to context

effects on judgments of physical attractiveness and interpersonal evaluations in order

to form hypotheses about online perceptions that can be tested on the basis of

judgments resulting from different characteristics on Facebook profiles. An original

experiment involved mock-up Facebook profiles that alternately featured attractive

or unattractive elements surrounding invariant central profile material. These var-

iations affected observers’ impressions of credibility and attractiveness, all without

the target of these judgments having changed.

Facebook

Facebook is a social networking Web site initially built for college communities. It is

organized around social networks corresponding to schools and, recently, other

institutions and locales. Like other online social networking sites (see for review,

Donath & boyd, 2004; Stutzman, 2006), Facebook provides a formatted Web page

Human Communication Research 34 (2008) 28–49 ª 2008 International Communication Association 29Facebook Friends and Individual Evaluations J. B. Walther et al.

profile into which each user can enter a considerable amount of personal informa-

tion in response to stock questions about his- or herself. On Facebook, this may

include birthdate, e-mail address, physical address, hometown, academic demo-

graphics (year, major), hobbies, sexual orientation, relationship status, course sched-

ule, favorite movies, music, books, quotations, online clubs, and a main picture (or

other graphic) chosen by the user. Within and across social networks, users are

allowed to search for other registered users and can initiate requests to other indi-

viduals to be friends. The implicit definition of friends on Facebook ranges from

established intimate relationships to simply being acquainted (boyd, 2006). Once

accepted as a friend, not only the two users’ personal profiles but also their entire

social networks are disclosed to each other, and new friendships often evolve via

friends’ friends. One’s social network snowballs rapidly across institutions in this

fashion, and this is the very function of Facebook that has fascinated millions of

students and other users in the United States so far. The number of registered

Facebook members was recently purported to be 19 million (Facebook Customer

Support, personal correspondence, March 7, 2007).

In addition to his or her own profile, all users have a ‘‘wall’’ on their Facebook

profiles, where their friends can leave messages to the owner in public. In other

words, those peer-to-peer messages can be viewed by other registered users. These

postings contain the friend’s default photo from his or her own profile, as well as

a verbal message. The messages may express sentiments or reflect common or indi-

vidual activities between the target and/or the friend. They may even reflect a desire

to embarrass the profile owner, according to a popular press account (Haskins,

2005). Individuals may not know, for some interval of time, that particular com-

ments have been posted to their walls. Even if they do, they tend not to remove

friends’ postings from their profiles. Doing so is possible but defeats the spirit of

Facebook’s very utility and implicitly challenges the rules of friendship. Therefore,

even if people question what has been said about them, they may follow Facebook

norms and leave questionable posts on display. Half of the Facebook users in Tufekci

and Spence’s (2007) survey reported the discovery of unwanted pictures posted by

other people, linked to their own profiles. It is these postings, which are not initiated

by the profile owner but that nevertheless connect to that individual’s profile, that

make social networking technologies such as Facebook unique. This investigation

focuses on the impression-connoting potential of these postings.

Do people garner interpersonal impressions from Facebook materials? It appears

they do both for acquainted and for unacquainted targets. People already know

many of the individuals they view on Facebook. More than 90% of Facebook users

employ Facebook to stay in touch with or stay abreast of the activities of longtime

acquaintances such as high school friends (Ellison, Steinfield, & Lampe, 2007).

According to Tufekci and Spence (2007), more than half of the Facebook users

reported having found out something very important about friends from their

profiles. With respect to previously unacquainted individuals, some system creators

promote their sites as a means for ‘‘making new friends’’ (Donath & boyd, 2004,

30 Human Communication Research 34 (2008) 28–49 ª 2008 International Communication AssociationJ. B. Walther et al. Facebook Friends and Individual Evaluations

p. 71). In such cases, Facebook may provide the primary basis for impressions.

According to Ellison et al. (2007), approximately 80% of one college’s Facebook-

using sample indicated that total strangers on their own campus view their Facebook

profiles, and nearly 40% believe that total strangers from other universities view their

profiles as well. Even when previously unacquainted individuals meet offline at

college, they check the other’s Facebook profile to learn more about that person

and whether there are any common friends or experiences. This checking may

happen when such newly met individuals return home to their computers or, we

have been told anecdotally, is even done almost immediately after meeting, surrep-

titiously, using Web-enabled mobile phones.

Others are using Facebook to garner information about users as well. The Yale

Daily News created shock waves when it reported that numerous employers have

utilized Facebook to seek information about potential employees (Balakrishna,

2006). The shock was due in part to Facebook users’ presumption that Facebook,

like other virtual communities, is or should be private, if not technologically then by

convention. Users often expect that the messages they leave about themselves and

others are secluded to other college students or college personnel. Although a wider

audience than expected may have technical access to their systems, users of many

types of virtual communities develop a strong expectation of privacy about their

online postings and exchanges. Research has documented that both online commu-

nity participants (Hudson & Bruckman, 2004) and teenagers (Rifon, Vasilenko,

Quilliam, & LaRose, 2006) feel quite negatively about having their messages studied

in research. Individuals often feel that they should be free from observation online

and that they have legal and/or ethical rights to such freedom (no matter how

technologically or legally misplaced those expectations may be; see Walther, 2002).

Thus, the nature of some messages on Facebook is such that they might not have

been posted had the writers expected a wide and diverse audience to access them.

As we will show, garnering impressions from online information is nothing new,

although the kinds of information social networking technologies present and the

manner in which impressions form may be.

Impression formation and online venues

People spend considerable effort in order to form and to manage impressions,

especially when anticipating or engaging in the initial stage of interactions (Berger &

Calabrese, 1975; Goffman, 1959). Being able to self-present in a positive manner has

been tied to social (and even physical) survival (Hogan, Jones, & Cheek, 1985).

Nearly two decades of research has focused on the impressions people garner among

those who they initially encounter via interactive CMC, that is, CMC in which

participants’ discourse—synchronous or asynchronous—is the basis for impres-

sions. The central issue in that research tradition is that the nonverbal features

that typically stimulate impressions offline are unavailable through text-based

e-mail, group discussions, or real-time chat. Whereas early research suggested that

Human Communication Research 34 (2008) 28–49 ª 2008 International Communication Association 31Facebook Friends and Individual Evaluations J. B. Walther et al.

interpersonal impressions were occluded by CMC, alternative positions established

contrary findings. For instance, social information processing theory (Walther,

1992) posits that CMC users readily translate the production and detection of affec-

tive messages from nonverbal behavior to verbal equivalents, although doing so may

require more time and message exchanges in order to achieve normal levels of

impressions (see, for review, Walther, 2006).

The impressions garnered via CMC, however, may or may not be just like those

that occur from face-to-face encounters. In online interaction, there are fewer cues to

observe and those that remain are under greater control of the persons to whom those

cues pertain. Jacobson (1999) found that the initial impressions that individuals held

about their partners through interactions in a multiplayer chat environment were

discordant with later offline impressions of the same people, usually with respect to

physical features. Hancock and Dunham (2001) found that participants in an online

task-focused discussion of limited duration tended to make fewer judgments about

the personalities of their partners, but more intense ratings on the judgment scales to

which they did respond, than in comparable face-to-face discussions.

Because online impressions are controllable, they are often suspect. Online users

can organize the information flow and enhance self-image by strategically selecting

how and what to convey to the receiver (Herring & Martinson, 2004; Walther, 2007;

Walther, Slovacek, & Tidwell, 2001). Inflating or even manipulating others’ percep-

tions of oneself has come to be expected, and no small portion of online users’

disclosures involves a modicum of exaggeration, even with good chances of meeting

offline observers of their online portraits (Ellison, Heino, & Gibbs, 2006).

One way in which Facebook differs from other online sites for self-presentation

has to do precisely with the degree to which some personal information is presented

by means other than disclosure by the person to whom it refers. In many other

communication settings, as Petronio (2002) notes, people make active decisions

about when and how they will self-disclose. These decisions involve a complex pro-

cess in which people set rules about how and when they will divulge private infor-

mation, negotiate those rules with other people, and make decisions on disclosure

based on violations of those rules. However, social networking sites to some extent

obviate an individual’s rules, negotiations, and disclosure decisions by placing dis-

cretion at the mercy of their social networks: ‘‘While (individuals) may have control

over the content they disclose on their university-housed webpages, friends . can

post discrediting or defamatory messages on users’ Facebook websites,’’ according to

Mazer, Murphy, and Simonds (2007, p. 3).

Walther and Parks (2002) considered the interplay of online self-generated

claims and other-generated clues in their formulation of the ‘‘warranting’’ value of

information, or the perceived validity of information presented online with respect

to illuminating someone’s offline characteristics. The warranting value of informa-

tion is hypothesized to be a function of the degree to which that information is

perceived to be immune to manipulation from the target to whom the information

pertains. Several forms of high-warrant information have been nominated that meet

32 Human Communication Research 34 (2008) 28–49 ª 2008 International Communication AssociationJ. B. Walther et al. Facebook Friends and Individual Evaluations

this classification. Information gained about someone through others in that per-

son’s social network is one example. People try to find out about one another via

common nodes in overlapping social networks for several reasons: to reduce uncer-

tainty about the partner, for example, and to do so without direct knowledge of the

target that s/he is being inquired after (Parks & Adelman, 1983). Moreover, the

objectivity and validity of third-party information should be considered more reli-

able than self-disclosed claims of the same nature. Thus, in a Facebook profile, things

that others say about a target may be more compelling than things an individual says

about his- or herself. It has more warrant because it is not as controllable by the

target, that is, it is more costly to fake.

Aside from interactive exchanges, people leave and make impressions via the

Internet by the intentional and unintentional characteristics conveyed by home

pages on the World Wide Web (www). Although there are numerous studies focus-

ing on personal Web sites and their creators (see Marcus, Machilek, & Schütz, 2006),

much of the literature relies on speculation or anecdotal evidence. Miller (1995), for

instance, suggests that users intentionally present themselves on the Web through

self-description, photographs, links to other Web pages, and by the style and format

(text, font, color, and background choices), structure, and vocabulary of their Web

pages. More systematic evidence has identified several elements that raise or lower

Web sites’ credibility, including being recommended by others and being linked to

from another credible Web site (Fogg, 2003; Fogg et al., 2001).

People use various features to assess personalities of the Web site creators (Vazire

& Gosling, 2004). They rely both on things that site creators deliberately display and

on things that creators unintentionally display to assess the character of the creator

of the original site. These elements are important in understanding how observers

appraise Facebook profiles: how they take in the intentionally built profile material as

well as the unintentional, that is, the material left on one’s profile site by friends in

one’s electronic and/or physical social network. These benchmarks, however, do not

enhance our theoretical understanding of the matter. By examining some theories

related to person perception via the artifacts that surround them, we gain more

focused insights not only into perceptions of individuals in general but also how

those perceptions are affected by context effects, that is, by concurrent information

about an individual’s associates and how, by assimilation, one’s associates affect

one’s image.

The Brunswikian lens model

Brunswik’s lens model (Brunswik, 1956; Gigerenzer & Kurz, 2001) describes one

process by which individuals make inferences about the characteristics of others.

According to this approach, individuals produce behaviors and generate artifacts

that reflect their personalities. These personality ‘‘by-products’’ are available for

observers to judge. In other words, the model supposes that environmental cues

function as a lens through which observers make inferences about the underlying

characteristics of a target. The lens model discusses the utility of various cues in

Human Communication Research 34 (2008) 28–49 ª 2008 International Communication Association 33Facebook Friends and Individual Evaluations J. B. Walther et al.

terms of cue validity, cue utilization, and functional achievement. When a particular

cue is accurately reflective of a target’s underlying personality characteristics, that cue

is said to have cue validity. Brunswik conceptualized that observers do not rely on all

possible cues in making their judgments about others, thus establishing the link

between an environmental cue and an observers’ utilization of that cue as cue uti-

lization. Finally, functional achievement is defined as the co-occurrence of both cue

validity and cue utilization. When functional achievement occurs, an observer

should make an accurate judgment about a target.

Research has used Brunswik’s lens model as a framework to understand others’

personality judgments of a target based upon elements in the space that targets more

or less control. Gosling, Ko, Mannarelli, and Morris (2002) used the lens model in

their study of personality judgments based on personal offices and bedrooms. They

proposed four mechanisms that linked individuals to the environments that they

inhabit: self-directed identity claims, other-directed identity claims, interior behavioral

residue, and exterior behavioral residue.

Self-directed identity claims are ‘‘symbolic statements made by occupants for

their own benefit, intended to reinforce their self-views’’ (p. 380). Other-directed

identity claims are ‘‘symbols that have shared meanings to make statements to others

about how they would like to be regarded’’ (p. 380). Gosling et al. (2002) concep-

tualize interior behavioral residue as ‘‘physical traces of activities conducted in the

[immediate] environment’’ (p. 381). Gosling et al. note that though interior behav-

ioral residue generally refers to past behaviors, they may reflect anticipated future

behaviors that may occur in the immediate environment. Exterior behavioral residue

is conceptualized as a ‘‘residue of behaviors performed by the individual entirely

outside of those immediate surroundings’’ (p. 381).

Using these elements, research has extended Gosling et al.’s (2002) use of

Brunswik’s lens beyond physical space to include Web space, that is, by using the

lens approach to study how observers make personality judgments about target

individuals based upon the targets’ personal Web pages (Marcus et al., 2006; Vazire

& Gosling, 2004). Although previous research has examined static personal Web

pages the creators of which had editorial control of the information presented therein,

Vazire and Gosling analyzed elements of users’ Web pages as those that were inten-

tionally created (identity claims) as well as those that were not (behavioral residue).

Although they describe personal Web sites as a ‘‘highly controlled context’’ where

self-expression consists almost exclusively of identity claims, they also note that ‘‘no

real-world environment can be completely free of behavioral residue’’ (p. 124). Inad-

vertent elements such as broken links, spelling and grammar errors, and other ‘‘unin-

tentional cues’’ exist and impact the judgments people make. Using a random

selection of personal Web pages from the Yahoo! directory, observers rated each

personal Web page on the personalities of the Web page authors along the dimensions

of the five-factor model (FFM) of personality (see McCrae & Costa, 1999). The

authors of those Web pages also completed self-report FFM instruments, and there

were high levels of interrater and rater–author consensus on all the factors of the FFM.

34 Human Communication Research 34 (2008) 28–49 ª 2008 International Communication AssociationJ. B. Walther et al. Facebook Friends and Individual Evaluations

These applications of the lens model to home pages, including both ‘‘other-

directed identity claims’’ and ‘‘interior behavioral residue,’’ in that the information

presented is deliberately or incidentally associated with the sender and interpreted by

observers as such, provide insights to the potential effects of information forms on

Facebook. From this perspective, information left by others on one’s interactive

profile site may be utilized as cues about the profiler and, if so, may function as

exterior behavioral residue if they present clues about the profiler’s behavior in some

context other than Facebook. Although such clues are not emitted by the target his-

or herself, their association by observers with the targets is consistent with the lens

model approach, which focuses on the associations observers draw in any judgmen-

tal context. It may be especially true in this context because the presence of wall posts

(comments left by other individuals) on a Facebook profile may implicitly connote

approval by the target. When profilers choose to associate with the other users, or

‘‘friends,’’ they allow them ‘‘user privileges’’ to post to their profile walls. Thus, the

behavioral residue left by their Facebook friends can be construed as sanctioned, at

least in the eyes of observers.

Context effects

In addition to the Brunswikian lens, research focusing on ‘‘context effects’’ in person

perception also suggests that characteristics of other people who appear together

with a target affect perceived attractiveness of the target. In this case, research has

focused on physical attractiveness judgments. Melamed and Moss (1975) demon-

strated context effects by showing pairs of photographs to research participants.

A photo depicting an individual of average attractiveness was shown along with

a very attractive or a very unattractive individual in the other of the pair. When

participants were told nothing about any relationship between those individuals in

the photo, a contrast effect occurred: Average faces were rated less attractive when

paired with a more attractive face, and average faces rated more attractive when

paired with a less attractive face. However, in their second experiment, Malamed and

Moss presented average faces along with two attractive ones or two unattractive ones,

and told half the subjects that an association existed between the individuals in the

pictures, or did not. When there was a presumed relationship, an assimilation effect

took place: Average-attractiveness photos were rated more attractive than neutral

when they appeared alongside attractive faces; average-attractiveness photos

appeared less attractive when presented along with low-attractive faces. Research

by Geiselman, Haight, and Kimata (1984) tested whether these effects occurred in

combinations of four photos and two photos; assimilation effects persisted across

these conditions. Kernis and Wheeler (1981) extended these effects to observation of

live interaction, where results were similar. In the present case, however, the assim-

ilation of ostensible friends’ photos surrounding the target’s photo on that target’s

perceived attractiveness describes very well the potential of Facebook profiles to

arouse these effects and influence perceptions of a target’s attractiveness.

Human Communication Research 34 (2008) 28–49 ª 2008 International Communication Association 35Facebook Friends and Individual Evaluations J. B. Walther et al.

H1: The presence of physically attractive friends’ photographs on a target profile raises

targets’ physical attractiveness perceptions whereas physically unattractive friends

reduce targets’ physical attractiveness.

In addition to the potential assimilation of perceived physical attractiveness from

the presence of others’ photos, there may be second-order effects on social evalua-

tions that are also inferred from the apparent attractiveness of one’s Facebook

friends. There is a long-standing association between physical attractiveness and

positive personality impressions, leading researchers to conclude that ‘‘what is beau-

tiful is good’’ (Dion, Berscheid, & Walster, 1972). Whether or not the attribution of

goodness transfers from one’s friends to one’s self is unknown but could be a potent

effect of Facebook representations. This, too, is likely to exhibit an assimilation effect,

as with the transfer of physical attractiveness perceptions predicted in H1. That is,

a profile holder may seem ‘‘better’’ as a result of appearing to have physically attrac-

tive friends (assimilation). However, as in the case of physical attractiveness percep-

tions, it is also possible that a profile owner may be perceived as ‘‘worse’’ in

comparison to one’s presumably desirable, physically attractive friends, constituting

a contrast effect. Notwithstanding this possibility, the second hypothesis is directional

but the precise directionality is contingent on the effect for H1 such that social

attractiveness may change as a result of friends’ photos’ attractiveness in the same

positive or negative direction as physical attractiveness ratings change.

Rather than focus on global ‘‘goodness’’ in the present case, we will focus on

common interpersonal evaluations that are sensitive to communication variations.

Although any number of attributes might be examined, the nonphysical aspects of

interpersonal attractiveness—social and task attractiveness—along with source cred-

ibility are common evaluative dimensions in impressions of interaction partners, and

their factor-based measures have been used in communication research for over 3

decades (see Burgoon, Walther, & Baesler, 1992). According to McCroskey and

McCain (1974), social attractiveness represents liking, for example, the degree to

which a target is seen as a likely friend, whereas task attractiveness connotes the

degree to which a target is seen as a valued and respected task partner (see, for review,

Rubin, Palmgreen, & Sypher, 1991). Source credibility pertains to how people eval-

uate others as acceptable information sources, and generally pertains to their exper-

tise and trustworthiness, although the precise factors comprising credibility may vary

due to a variety of reasons (see, for review, Rubin et al., 1991).

With regard to the effect of friends’ apparent physical attractiveness on a profile

owner’s task attractiveness and credibility, we hypothesize the opposite direction

than we do for physical and social attractiveness. Physical attractiveness has been

associated with lower observers’ perceptions of competence. ‘‘Physical beauty. can

impose limitations on the kinds of performances others view as credible. Beautiful

people may be considered unapproachable or unintelligent,’’ according to a review

by Burgoon and Saine (1978, p. 263). Once again, it is likely but not certain whether

such an attribution of an individual’s abilities is bestowed due to or in contrast to

36 Human Communication Research 34 (2008) 28–49 ª 2008 International Communication AssociationJ. B. Walther et al. Facebook Friends and Individual Evaluations

one’s friends’ attractiveness. Moreover, because the deleterious effect of physical

attractiveness on competence discussed by Burgoon and Saine was documented

more clearly for female than male targets, a research question is offered to guide

investigation of the pattern’s occurrence in Facebook profiles.

H2: The physical attractiveness of one’s friends depicted on a virtual profile

affects observers’ perceptions of the profile owner on social evaluations

(a) in the same direction as physical attractiveness, for social attractiveness

and (b) in the opposite direction as physical attractiveness, for (i) task

attractiveness and (ii) credibility.

RQ1: Does the effect of physical attractiveness of friends’ photos interact with the sex of

the profile owner on (a) task attractiveness and (b) credibility?

Hypotheses are also derived based on context effects and the Brunswikian lens

conception of the utilization of cues. We extend cue utilization to include behavioral

residues that appear in the wall postings that friends leave in a profile owner’s

(virtual) space. Although they are not created by the target, because the target allows

specific others to leave these residues such cues will be utilized and affect observers’

impressions of targets. We hypothesize:

H3: Statements made by others on one’s virtual profile influence observers’ social

evaluation of the profile owner with respect to (a) social attractiveness, (b) task

attractiveness, and (c) credibility, in directions consistent with the valence of the

statement content.

Finally, a research question asks whether the association between attributions of

goodness and physical attractiveness works in reverse, if positive qualities bestowed

by friends’ statements left on a profile owner’s site might invoke superior perceptions

of physical attractiveness for the profile owner.

RQ2: Do positive (vs. negative) friends’ statements on a profile owner’s site raise the

perceived physical attractiveness of the profile owner?

Methods

Participants (N = 389) volunteered to take part in the research in exchange for extra

credit or satisfaction of a research requirement in one of several communication or

telecommunication courses at a large public university in the midwestern United

States. Each participant viewed one of the eight stimuli each containing a mock-up of

a Facebook profile. Differences among stimuli reflected variations in (a) physically

attractive or unattractive photos of ostensible wall posters and (b) positively or

negatively valued content of the wall posting messages with respect to their descrip-

tion of the profile owner’s behavior. There were all-female and all-male versions of

the stimuli. Because physical attractiveness ratings are sometimes affected by the sex

combination of the rater and target, omnibus data analyses included these factors.

Human Communication Research 34 (2008) 28–49 ª 2008 International Communication Association 37Facebook Friends and Individual Evaluations J. B. Walther et al.

Thus, the overall design was 2 (attractive or unattractive wall poster) 3 2 (positive or

negative wall message) 3 2 (sex of profile owner) 3 2 (sex of participant).

Stimuli

Wall poster attractiveness

Researchers pretested a number of photographs containing head shots of college-

aged persons in order to create specific variations in the apparent attractiveness of

wall posters (high and low attractiveness) and depict neutral attractiveness for the

ostensible profile owners. Researchers gathered photographs from photo-rating Web

sites (i.e., hotornot.com), from photos generated in previous studies where permis-

sion to use participants’ likenesses was given, and by utilizing an Internet search

engine with keywords such as ‘‘pretty girl.’’ Photos that seemed to capture the range

of attraction were presented to a mixed-sex group of college-aged raters (N = 10)

who evaluated each photo on a scale from 210 (physically unattractive) to 10 (phys-

ically attractive). Analyses of these scores yielded two attractive and two unattractive

male, and two attractive and two unattractive female, photos, among which there

was no overlap on raw attractiveness ratings. These photos were used to represent

wall posters on the profile mock-ups. Analyses also revealed neutral photos, which

were employed to represent the profile owners.

Message value

Focus groups and pretests also contributed to the development of verbal messages in

the wall postings. These postings were designed to reflect positively or negatively on

the profile owner by describing things the owner had done or would do, which were

socially desirable or undesirable among the college population based on the results of

focus group discussions. Messages were generated in part by actual postings observed

on Facebook that reflected the behaviors of the profile owner. Rewrites followed

focus group discussions that helped shape messages that were both believable and

positive or negative to the prospective participants who would later observe them.

Each pair had a male and female version.

The focus group discussions sought to discern what types of behaviors discussed

in Facebook postings connoted desirable and undesirable qualities or characteristics.

These discussions employed college-aged discussants other than those who were later

to become research participants. Discussions began with the question: ‘‘What state-

ments on Facebook would lead you to think that the profile owner was a ‘loser,’ or

conversely, a really desirable person?’’ Respondents suggested that statements reflect-

ing both excessive and morally dubious behavior were unfavorable. For example,

drinking, per se, was not negative, nor was drinking a considerable amount, but

drinking to the point of illness was. Flirting was not negative but flirting with

unattractive targets, and promiscuity, was alleged to be. Positive messages, on

the other hand, generally connoted that the profile owner was a socially desirable

individual. The person was, for instance, popular with people or was included in

38 Human Communication Research 34 (2008) 28–49 ª 2008 International Communication AssociationJ. B. Walther et al. Facebook Friends and Individual Evaluations

enjoyable past or future activity of some type. Prototype messages were reviewed,

and the final set consisted of two excessive and negative or inclusive and positive

statements per stimulus. The specific foci of these stimulus messages may have some

effects on the ultimate and differential responses to them, as will be discussed below.

At the point of their creation, though, they satisfied the criteria of arousing respect-

ively negative and positive global evaluations.

Message postings also reflected profile owners’, rather than posters’, behavior.

Although spectators reading about friends’ own behaviors might also attribute qual-

ities to the profile holder (in the same way that photos affect judgments), verbal

messages were designed to reflect only owners’ behaviors. This approach is consistent

with the behavioral residual principle in which clues pertain to a central target, which

drove the hypotheses regarding messages. This approach was bolstered by a content

analysis of the nature of wall postings on Facebook, which indicated that many

postings do indeed discuss the target explicitly. One coder content analyzed 237

randomly selected Facebook wall postings on the college network where the research

took place. The coder classified 27% of friends’ postings as presenting information

about the target (profile owner), 23% as presenting information about the friend/

poster his- or herself, 28% presenting information about both the target and the

poster, and 21% pertaining to other foci or undeterminable. Thus, approximately

55% of wall postings referred to the profile owner alone or the poster and the profile

owner. Future research may explore the effects of self-oriented wall poster messages

on profile owner evaluations if such questions are warranted.

The final set of negative messages consisted of the following:

‘‘WOW were you ever trashed last night! Im not sure Taylor was that

impressed.’’

‘‘Hey, do you remember how you got home last night? Last I remember you

were hanging all over some nasty slob. please tell me you didnt take [him/her]

home..’’

Positive messages consisted of these:

‘‘Vegas Baby!!! Only 3 days and we are on our way. Im so pumped!’’

‘‘Chris, I just gotta say you rock!!! u were the life of the party last night.

all my friends from home thought you were great!’’

Typographical errors in these messages were intentional and reflect common writing

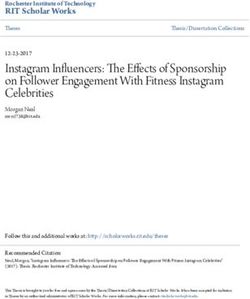

characteristics in Facebook postings. An example stimulus is presented in Figure 1.

Procedure

Researchers provided volunteers with a single www address and requested that they

complete the research on their own. Participants therefore viewed stimuli in a natural

setting in which they typically used the Internet. The www address directed users to

a Web page that reflected informed consent information and a button with which to

signal consent. Clicking the button activated a hidden Javascript code that randomly

Human Communication Research 34 (2008) 28–49 ª 2008 International Communication Association 39Facebook Friends and Individual Evaluations J. B. Walther et al.

Figure 1 Sample Facebook profile mock-up. Faces have been blurred for publication.

redirected a participant’s Web browser to one of the eight stimulus conditions.

Participants were instructed to view the Facebook profile and then to follow a

link to a questionnaire where they would answer questions about the Facebook

profile owner.

Questionnaire measures

The posttest questionnaire included measures of task, social, and physical attractive-

ness developed by McCroskey and McCain (1974). These 15 items employed

7-interval Likert-type response scales. Task attractiveness included items such as

‘‘I have confidence in this person’s ability to get the job done’’ and ‘‘If I wanted to

get things done, I could probably depend on this person.’’ Task attractiveness yielded

a Cronbach’s alpha reliability estimate of .79. Social attractiveness obtained a = .75

and included items such as ‘‘I would like to have a friendly chat with this person’’ and

‘‘I think this person could be a friend of mine.’’ Physical attractiveness included items

such as ‘‘This person is somewhat ugly’’ (reverse coded) and ‘‘I find this person very

attractive physically’’; a = .86.

Participants also rated profile owners on credibility using the 15 bipolar adjective

items from Berlo, Lemert, and Mertz (1970). Credibility measurement is known to

40 Human Communication Research 34 (2008) 28–49 ª 2008 International Communication AssociationJ. B. Walther et al. Facebook Friends and Individual Evaluations

be context sensitive; it yields different factor structures in different settings with

different sources and raters (see, e.g., Cronkhite & Liska, 1976). Therefore, research-

ers conducted a principal components factor analysis with Varimax rotation using

these criteria for factor retention: (a) factors display eigenvalues of 1.5 or greater,

(b) scree analysis displayed improvement in variance accounted through addition of

a dimension, and (c) factors contain at least three items with primary loading of 0.60

or greater and secondary loadings below 0.40. A three-factor solution accounting for

51.5% of the variance emerged, with factors similar to the dimensions prescribed by

Berlo et al. (1970); Cronbach reliability estimates were acceptable for qualification,

a = .87, including such items as Experienced/Inexperienced, Qualified/Unqualified,

and Informed/Uninformed; safety, a = .89, including Just/Unjust, Honest/Dishonest,

and Safe/Dangerous; and dynamism, a = .87, which included Bold/Timid, Active/

Passive, and Energetic/Tired. Although individual subscales might vary indepen-

dently, and the qualification and safety dimensions may be those most commonly

associated with the commonplace notion of credibility, no precision is lost in testing

these components simultaneously.

Finally, participants provided demographic information. Forty-six cases (11%

of the sample) in which participants had no Facebook account were removed

from further analysis (as was one individual who reported having 5,000 friends).

The remaining sample of 342 cases was 53% male and had a mean age of 19.9 years

(SD = 1.77); their year in school was 18% freshmen, 31% sophomores, 34% juniors,

15% seniors, and 2% missing. They had been using the Internet from 3 to 15 years,

M = 8.95, SD = 2.20. The mean number of Facebook friends participants reported

having was 245.91, SD = 183.76, mode = 200. They spent a mean of 3.72 hours per

day on Facebook (SD = 4.04, mode = 1, Mdn = 2, minimum = 0, maximum = 20,

suggesting that some individuals left their computers logged into Facebook most

of the day).

Results

H1 predicted that greater physical attractiveness of friends displayed on wall postings

in one’s Facebook profile raises perceptions of the profile owner’s physical attrac-

tiveness. Given the directional nature of the hypothesis, it was tested by way of a one-

tailed t test, which was significant, t(341) = 2.37, p , .01, h2 = .02. Participants who

saw attractive friends’ photos rated the profile owner significantly more physically

attractive (M = 3.65, SD = 1.17, N = 183) than did those exposed to unattractive

photos (M = 3.30, SD = 1.17, N = 160). This finding confirms an assimilation effect:

Profile owners’ attractiveness varied in the same direction as their friends’ did.

An omnibus F test showed no interaction effects involving the photos’ attractiveness

with any other factors on physical attractiveness ratings.1

H2 predicted that social evaluations of the Facebook profile owner are affected by

their friends’ photos’ physical attractiveness. Given that physical attractiveness rat-

ings corresponded positively with photo attractiveness, we expected positive effects

Human Communication Research 34 (2008) 28–49 ª 2008 International Communication Association 41Facebook Friends and Individual Evaluations J. B. Walther et al.

on social attractiveness as well (H2a), but negative effects were anticipated for task

attractiveness and credibility (H2b). Because the directions of the hypotheses dif-

fered for social attractiveness versus task attractiveness and credibility, hypothesis

testing proceeded in two steps. The test for H2a examined the effects of friends’

photo attractiveness only on social attractiveness ratings. Because the hypothesis

predicted directional effects for the impact of physically attractive photos on social

attractiveness perceptions, a one-tailed t test was conducted, which supported H2a,

t(341) = 1.70, p , .05, h2 , .01.

H2b specified negative effects on evaluations that were assessed with several

measures: task attractiveness and the three dimensions of credibility (safety, quali-

fication, and dynamism). Bartlett’s test of sphericity, x2(20) = 695, p , .01, indicated

that these variables were sufficiently related to be treated as a group. (Simple

correlations among all dependent variables are presented in Table 1.) Therefore,

a multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA) test examined the effect of friends’

photos on the set of dependent variables simultaneously. This test produced no

significant multivariate effects, Wilk’s l = 1.22, F(4, 338) = 1.22, p = .30. H2b was

not supported.

RQ1 explored whether previously documented stereotypical negative associa-

tions between physical beauty and competence for women were prompted by

friends’ photos and, if so, whether it was confined to judgments of females. Specifi-

cally, analyses focused on whether the interaction of physical attractiveness of the

friends’ photos with the sex of the profile owner affected task attractiveness and

credibility. As in the previous test, this analysis employed a multivariate test, with the

Photo 3 Target Gender interaction (and main effect factors) as the independent

variables. The omnibus test did not yield significance for the interaction effect,

Wilk’s l = 0.99, F(4, 326) = 0.74, p = .66. It appears that the physical attractiveness

of one’s Facebook friends does not affect observers’ judgments of one’s qualifica-

tions, either directly or in combination with the target’s gender.

H3 predicted that the valence of statements left by friends on a profile owner’s

Facebook wall affects social evaluations of the profile owner in a consistent direction

across the dimensions of social and task attractiveness and credibility. A preliminary

Table 1 Correlations (r) Among Physical Attractiveness, Social Attractiveness, Task Attrac-

tiveness, Safety, Qualification, and Dynamism

Social Task

Attractiveness Attractiveness Safety Dynamism Qualification

Physical attractiveness .26* .28* 2.12* 2.13* 2.02

Social attractiveness .26* .16* .02 .19*

Task attractiveness .12 2.08 .18*

Safety .11 .52

Dynamism .10

Note: *p , .05. N = 333.

42 Human Communication Research 34 (2008) 28–49 ª 2008 International Communication AssociationJ. B. Walther et al. Facebook Friends and Individual Evaluations

omnibus MANOVA yielded a significant multivariate interaction effect between

statements’ valence and sex of the participant, Wilk’s l = 0.95, F(5, 326) = 3.17,

p , .01, h2 = .01. The effect appeared to be confined to dynamism alone, which

revealed the sole univariate effect, F(1, 330) = 8.60, p , .01, h2 = .03, where the

pattern of means indicated a disordinal interaction. When female participants

viewed positive messages, they rated the profile owner less dynamic, M = 4.53,

SD = 0.92, N = 71, than when negative messages were shown, M = 4.85,

SD = 0.81, N = 90. Male participants, however, gave higher dynamism ratings when

they viewed positive messages, M = 4.76, SD = 0.84, N = 96, than when viewing

negative messages, M = 4.56, SD = 0.81, N = 85. Analysis proceeded to the main ef-

fects analysis implied in H3 with respect to the remaining social evaluation variables.

MANOVA examining the multivariate main effect of wall statements yielded

significance, Wilk’s l = 0.89, F(5, 338) = 8.99, p , .01, h2 = .11. See Table 2 for

descriptive statistics, F and h2 values. Univariate effects occurred on each of the four

remaining dependent variables. Positive wall postings yielded higher safety assess-

ments than negative statements by friends. Qualification was similarly affected;

participants exposed to positive wall postings rated the profile owners more qualified

than their counterparts who read negative statements. Both task and social attrac-

tiveness were influenced by the wall postings made by friends with regard to the

profile owners. Task attractiveness of the profile owner was significantly higher when

the statements from friends were positive than when negative; and profile owners

were rated significantly more socially attractive when friends’ wall posting statements

were positive than when they were negative. Due to the higher-order interaction on

dynamism, that variable was not tested for a main effect of statements. With that

exception, H3 was supported.

RQ2 asked whether the valence of friends’ wall postings affected the physical

attractiveness perceptions of the profile owner on whose wall the postings appeared.

A preliminary omnibus analysis of variance revealed a significant disordinal inter-

action of message valence by the apparent gender of the profile owner, F(1, 339) =

6.47, p = .01, h2 = .02. Female profile owners were rated more physically attract-

ive when their profiles showed positive comments from friends, M = 3.98, SD = 1.29,

Table 2 Means (and SD) for Effects of Wall Posting Statements on Safety, Qualification, Task

Attractiveness, and Social Attractiveness

Statements from Friends

Positive (N = 167) Negative (N = 175) F(1, 341) h2

Safety 4.50 (0.71) 4.00 (0.71) 41.45 .11

Qualification 4.12 (0.75) 3.80 (0.76) 14.94 .04

Task attractiveness 4.15 (0.84) 3.77 (0.91) 15.94 .05

Social attractiveness 4.45 (0.97) 4.05 (1.04) 14.00 .04

Note: p , .01.

Human Communication Research 34 (2008) 28–49 ª 2008 International Communication Association 43Facebook Friends and Individual Evaluations J. B. Walther et al.

N = 80, than when the statements were negative, M = 3.46, SD = 1.19, N = 100. This

pattern, however, was reversed when the profile owner was male; positive comments

yielded lower physical attractiveness ratings, M = 3.20, SD = 0.91, N = 88, whereas

negative statements produced greater physical attractiveness perceptions, M = 3.31,

SD = 1.17, N = 75. Due to the higher order interaction, no further analysis of

statements on physical attractiveness was warranted.

Discussion

The goal of this research was to examine how information provided by and about

people’s friends in a Facebook profile impacts judgments about the profile owners,

who did not themselves provide that information. This investigation addresses novel

theoretical questions about the process of impression formation and the influence of

different forms of communication in that process as these issues are revealed by new

communication technologies.

In this experiment, the physical attractiveness of one’s friends’ photos, as seen in

the Facebook wall postings presented on another individual’s profile, had a signifi-

cant effect on the physical attractiveness of the profile’s owner. Perceptions of phys-

ical attractiveness did not reduce task competence attributions, an effect associated

with evaluations of women in other, offline domains. It behooves one to have good-

looking friends in Facebook. One gains no advantage from looking better than

one’s friends.

Although photo appearance on a wall posting may directly reflect a quality of the

posting friend, not the profile owner, the verbal statements within wall postings may

describe behaviors of the profile owner more directly. This approach was reflected in

the stimuli adopted in the present study. Results showed that complimentary, pro-

social statements by friends about profile owners improved the profile owner’s social

and task attractiveness, as well as the target’s credibility.

In all analyses, the effect sizes were very modest. This should be expected given

the small proportion of overall information in the stimulus profiles that reflected

the independent variable manipulations. For instance, even though there were two

friends’ photos on each profile, both of which were respectively attractive or unat-

tractive, each profile also featured a much larger photo representing the target

person. These target photos were neutral in attractiveness, by design. Furthermore,

stimulus profiles offered neutral yet visible information about the target’s interests

and favorite media, as is customary on Facebook. Thus, given the large amount of

common, neutral information about the target against which the small manipula-

tions in friends’ photos and wall comments appeared, small effects on the target’s

physical attractiveness and personal characteristics are not surprising. In a sense, it is

somewhat surprising to see any effect on physical attractiveness perceptions, given

that the alleged target’s photo was more prominent than anything else.

An unanticipated interaction effect involving the sex of the profile owner and the

nature of the wall statements was obtained with respect to the effect of friends’

44 Human Communication Research 34 (2008) 28–49 ª 2008 International Communication AssociationJ. B. Walther et al. Facebook Friends and Individual Evaluations

comments on perceptions of the targets’ physical attractiveness. The negative state-

ments depicted normatively undesirable behavior, as they involved sexual innuendo

and insinuated that the target person was drinking excessively the previous night.

These statements raised the desirability of a man’s appearance among the subject

population in this study, whereas the residues of such behavior rendered the target

physically unattractive when she is female. These results reflect what has come to be

known as the sexual double standard when making social judgments or forming

impressions of others. The sexual double standard pertains to the differences in

individuals’ evaluations of men and women who engage in premarital sexual behav-

iors: Men who engage in such encounters receive respect or admiration, whereas

women who engage in similar behavior are often shunned or denigrated by society.

This effect has been shown to be a pervasive belief in Western cultural ideology and

the subject of much scholarly research (see, for review, Crawford & Popp, 2003;

Marks & Fraley, 2006). Not only do these findings suggest a double standard, they

also reinforce concerns over the potential of Facebook dynamics to reinforce stereo-

types and behaviors that are potentially harmful to college students (see, e.g., Bugeja,

2006; cf. Haley, 2006). We might speculate that if greater attractiveness is perceived

for males who misbehave, confirmatory and rewarding reactions by others might

reinforce such behaviors or set observational learning dynamics into play encour-

aging others to behave in a similar manner.

In addition to these value implications, this study offers additional theoretical

implications. The findings suggest support for the social information processing

theory of CMC (Walther, 1992) and the warranting principle articulated by Walther

and Parks (2002). It is relatively well documented that people use information pro-

vided to them online to make judgments about others. What is less known is what

kinds of information are used to make what judgments. This study highlights the

utilization of exterior behavioral residue for judgments of others in a Facebook

setting. People made judgments about a target based on comments left by the target’s

friends and by the attractiveness of those friends. Even though this information is not

provided by the target, people may believe this information to be sanctioned by the

target and employ these clues to form impressions of the target in a manner con-

sistent with the Brunswikian lens model (Brunswik, 1956).

Alternatively, because the information may be perceived as unsanctioned by the

profile owner, it may have particularly great impression-bearing value. The results are

consistent with Walther and Parks’s (2002) warranting hypothesis. The warranting

principle suggests that other-generated descriptions are more truthful to observers

than target-generated claims. Findings that friends’ statements significantly altered

perceptions of profile owners support this contention. It is less costly to alter or

distort claims that one makes about oneself (e.g., one’s own profile) than to modify

or manipulate statements made by others (e.g., their pictures and wall postings).

Thus, information reflected in others’ ‘‘testimonials’’ should be of special value to

an individual making a judgment about the profile owner, according to the warrant-

ing principle. Results with regard to participants’ ratings of profile owners’ social and

Human Communication Research 34 (2008) 28–49 ª 2008 International Communication Association 45You can also read