The Association Between Marijuana Smoking and Lung Cancer

←

→

Page content transcription

If your browser does not render page correctly, please read the page content below

REVIEW ARTICLE

The Association Between Marijuana Smoking

and Lung Cancer

A Systematic Review

Reena Mehra, MD, MS; Brent A. Moore, PhD; Kristina Crothers, MD;

Jeanette Tetrault, MD; David A. Fiellin, MD

Background: The association between marijuana smok- moricidal dysfunction, increased oxidative stress, and bron-

ing and lung cancer is unclear, and a systematic appraisal chial mucosal histopathologic abnormalities compared with

of this relationship has yet to be performed. Our objective tobacco smokers or nonsmoking controls. Observational

was to assess the impact of marijuana smoking on the de- studies of subjects with marijuana exposure failed to dem-

velopment of premalignant lung changes and lung cancer. onstrate significant associations between marijuana smok-

ing and lung cancer after adjusting for tobacco use. The

Methods: Studies assessing the impact of marijuana primary methodologic deficiencies noted include selec-

smoking on lung premalignant findings and lung can- tion bias, small sample size, limited generalizability, over-

cer were selected from MEDLINE, PSYCHLIT, and all young participant age precluding sufficient lag time for

EMBASE databases according to the following pre- lung cancer outcome identification, and lack of adjust-

defined criteria: English-language studies of persons 18 ment for tobacco smoking.

years or older identified from 1966 to the second week

of October 2005 were included if they were research stud- Conclusion: Given the prevalence of marijuana smok-

ies (ie, not letters, reviews, editorials, or limited case stud- ing and studies predominantly supporting biological plau-

ies), involved persons who smoked marijuana, and ex- sibility of an association of marijuana smoking with lung

amined premalignant or cancerous changes in the lung. cancer on the basis of molecular, cellular, and histopatho-

logic findings, physicians should advise patients regard-

Results: Nineteen studies met selection criteria. Studies ing potential adverse health outcomes until further rigor-

that examined lung cancer risk factors or premalignant ous studies are performed that permit definitive conclusions.

changes in the lung found an association of marijuana smok-

ing with increased tar exposure, alveolar macrophage tu- Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:1359-1367

M

ARIJUANA IS THE MOST cannabinoid compounds in addition to

commonly used illicit many of the same components as tobacco

drug in the United smoke. For instance, benzopyrene, a carci-

States.1 According to nogenic polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon,

the 2003 National Sur- is found in both tobacco and marijuana

vey on Drug Use and Health, more than 94 smoke and has been implicated in mutations

million Americans, or 40% of Americans related to lung cancer.4-7 Furthermore, ex-

aged 12 years or older have tried marijuana perimental studies support an association

at least once.2 Recent data indicate that past- between marijuana smoke exposure and

year prevalence of marijuana abuse or de- lung cancer, with lung cancer cell lines dem-

pendence increased significantly in the onstrating tetrahydrocannabinol (THC)-

Author Affiliations: population from 1.2% in 1991-1992 to 1.5% induced malignant cell proliferation8,9 and

Departments of Medicine, Case in 2001-2002, which translates into an a murine model suggesting that THC pro-

Western Reserve University, increase from 2.2 million persons to 3.0 mil- motes tumor growth by inhibiting antitu-

Cleveland, Ohio (Dr Mehra), lion.3 Given the widespread use of mari- mor immunity by a cannibinoid-2 recep-

and West Haven Veterans juana, its use for what are believed to be me- tor mediated pathway.10 Although the

Administration Hospital, dicinal purposes, and the increasing abuse preponderance of in vitro data supports a

West Haven, Conn

and dependence on this substance, it is im- biologically plausible association, limited re-

(Dr Tetrault); and Departments

of Medicine (Drs Crothers, portant to examine potential adverse clini- search exists that suggests anticarcino-

Tetrault, and Fiellin) and cal consequences. genic cannabinoid effects.11-13 Given these

Psychiatry (Dr Moore), Yale Marijuana smoking, like tobacco smok- contrasting data, we chose to systemati-

University School of Medicine, ing, may be associated with increased risk cally evaluate the association between smok-

New Haven, Conn. of lung cancer. Marijuana smoke contains ing marijuana and lung cancer.

(REPRINTED) ARCH INTERN MED/ VOL 166, JULY 10, 2006 WWW.ARCHINTERNMED.COM

1359

©2006 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.Table 1. Specific Medical Subject Headings Terms, Main Terms, and Text Words in MEDLINE, EMBASE, and PSYCHLIT

Concept Terms Text Words

MEDLINE

Marijuana use Cannabis, cannabinoids, marijuana abuse, marijuana marijuana or marihuana or cannabis or hashish or hash or

smoking ganja or ganga or bhang or hemp or pot

Pulmonary disorders Neoplasms/or exp carcinoma/or pathology/or cance$ or carcinom$ or squamous$ or adenocarcinom$ or

smoking/pathology or tars/respiratory tract diseases/, metaplasi$ or hyperplasi$ or dysplasia$ or pathology or

exp respiratory physiology/or lung tar or tars pulmonary or respirat$ or airway$ or lung$ or

bronch$ or inhale$

EMBASE

Marijuana use Cannabis, cannabinoids marijuana or marihuana or cannabis or hashish or hash or

ganja or ganga or bhang or hemp or pot

Pulmonary disorders Respiratory tract tumor/or neoplasm/or carcinoma/or cance$ or carcinom$ or squamous$ or adenocarcinom$ or

pathology/or tar/respiratory tract diseases/. metaplasi$ or hyperplasi$ or pathology or tar or tars

respiratory tract infections/respiratory system/respiratory pulmonary or respirat$ or airway$ or lung$ or bronch$ or

physiology inhale$

PSYCHLIT

Marijuana use Cannabis, cannabinoids/or marijuana/or exp marijuana marijuana or marihuana or cannabis or hashish or hash or

usage ganja or ganga or bhang or hemp or pot

Pulmonary disorders Neoplasms/neoplasms/or pathology/respiratory system/or Pulmonary, respirat$, airway$, lung$, wheez$, cough$,

exp respiratory distress/or exp respiratory tract disorders dyspnea, pulmonary or respirat$ or airway$ or lung$ or

bronch$ or inhale$

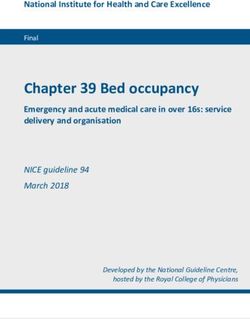

from the OVID, MEDLINE, PSYCHLIT, study setting; (5) subject selection; and

186 Abstracts

and EMBASE databases from 1966 to (6) subject characteristics.

the second week of October 2005, Tworeviewersindependentlyassigned

37 Duplicates

using the medical subject headings and a quality index score according to a 31-

text words shown in Table 1. point scale that assesses reporting, exter-

149 Abstracts

Retrieval of studies was performed by nal validity, bias (internal validity), con-

2 reviewers (R.M. and B.A.M.) who ex- founding (external validity), and power.14

119 Letters, Editorials,

amined the titles and abstracts obtained Based on these quality components, we

Reviews, Case Reports, from the initial electronic search. We ex- graded articles as good (a score ⱖ12) or

and Limited Case Series cluded letters, reviews, editorials (ie, non- fair to poor (a score ⬍12) based on an es-

Did Not Meet Exposure

or Outcome Criteria research studies), and case series involv- tablished cutoff.14 Differences between re-

ing fewer than 10 patients, as well as viewers were resolved by consensus with

30 Manuscripts Categorized studies that did not involve humans with input from the third reviewer. Interrater

direct, intentional marijuana smoking (eg, reliability was high (r=0.77).

11 Letters, Editorials, studies of hemp exposure in occupa-

Reviews, Case Reports, tional settings) or did not examine lung SELECTION AND DATA

and Limited Case Series

functioning or lung conditions related to

Did Not Meet Exposure

premalignant or cancerous changes. Stud-

SYNTHESIS

or Outcome Criteria

ies involving cannabis, hashish, and/or kif

(Moroccan hashish) were included ow- We identified 186 abstracts through the

19 Manuscripts Included

for Data Extraction and ing to content overlap. Abstracts that literature search as described in the

Quality Evaluation

could not be categorized based on the in- “Search Strategies” subsection (107 from

formation provided were reviewed in MEDLINE, 67 from EMBASE, and 12

manuscript form to allow a final deci- from PSYCHLIT); 37 were duplicates,

Figure. Literature search results. leaving 149 unique abstracts. Of these,

sion regarding classification. Studies with

discrepant categorizations by the 2 re- we categorized 119 based on abstract re-

The purpose of the current re- view and evaluated full manuscripts for

viewers were resolved by a third mem-

view is to determine whether (1) ber (D.A.F.) of the research team using the remaining 30 citations. The level of

marijuana smoking is associated with consensus. agreement regarding inclusion of po-

lung cancer risk factors or premalig- tential manuscripts based on abstract re-

nant changes assessed by known or view between the 2 reviewers was high

potential mediators of lung carcino- ABSTRACTION AND VALIDITY (=0.95). Of the 149 articles, 56 were

genesis and (2) marijuana smoking ASSESSMENT excluded because they were not re-

search studies (ie, they were letters, re-

is associated with increased inci- Data regarding methods were ex- views, or editorials); 8 were case series

dence of lung cancer. tracted using a custom-designed data col- of fewer than 10 cases; 51 did not in-

lection form. Data were collected on (1) volve humans with direct, intentional

METHODS amount, frequency, mode, and meth- marijuana smoking; and 15 did not in-

ods of marijuana smoking; lung cancer clude measures related to lung cancer.

SEARCH STRATEGIES risk factors or premalignant changes and Thus, 19 studies that examined the as-

lung cancer outcomes; (2) assessment of sociation between marijuana use and

English-language studies in persons tobacco or illicit substance use; (3) evalu- lung cancer were included in this sys-

aged 18 years or older were identified ation of preexisting lung disorders; (4) tematic review (Figure).

(REPRINTED) ARCH INTERN MED/ VOL 166, JULY 10, 2006 WWW.ARCHINTERNMED.COM

1360

©2006 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.Table 2. Studies Reporting Marijuana (MJ) Use Exposure and Tar Exposure

Male Participants,

Source; Study Type No. (%) Age (SD), y Setting Outcome

Matthias et al15; experimental 10 (100) 23.2 (.3) Metropolitan Tar delivery

Los Angeles

Tashkin et al16; experimental 10 (NP) NP NP Amount of inhaled tar deposition of inhaled tar, CO

boost; THC delivered to lung

Tashkin et al17; experimental 10 (NP) NP NP Amount of inhaled tar, percentage deposition of inhaled

tar, CO boost, THC delivered to lung

Wu et al18; experimental 15 (100) 31.5 (7.1) NP Blood CO, inhaled tar retention in the respiratory tract

Cannabis Confounders Mean Study

Source; Study Type Exposure Results Controlled Quality Score

Matthias et al15; experimental Habitual MJ smokers Tar delivered and deposited in the lung in the most NA 11

potent compared with the least potent MJ

preparation

Tashkin et al16; experimental Daily or near daily Longer breath-holding time significantly increased NA 11

MJ use over ⱖ5 y retention of inhaled tar in the lungs (P⬍.001)

Tashkin et al17; experimental Daily or near daily More tar was inhaled from the second half of the MJ MJ exposure compared 9.5

MJ use over ⱖ5 y cigarette than the first half (P⬍.05) with tobacco exposure

Wu et al18; experimental Habitual smokers Compared with smoking tobacco, smoking MJ MJ exposure compared 11.5

resulted in 3-fold increase in amount of tar with tobacco exposure

inhaled (P⬍.001)

Abbreviations: CO, carbon monoxide; NA, not applicable; NP, not provided; THC, tetrahydrocannibinol.

Table 3. Studies Reporting Marijuana (MJ) Use Exposure and Cytomorphologic Changes in Sputum Specimens

Male

Participants,

Source; Study Type No. (%) Age (SD), y Characteristic Outcome

27

Roby et al ; case-control 75 (100) 28 (17-38) Surfers from north coast of California Sputum samples

Starr and Renneker26; case control 75 (100) 27.5 (15-38) Surfers from California and Hawaii Cytologic evaluation of sputum

Cannabis Confounders Mean Study

Source; Study Type Exposure Results Controlled Quality Score

Roby et al27; case-control Smoking MJ regularly for Cytologic changes in habitual MJ smokers similar to MJ smokers 9.5

ⱖ2 y without tobacco use tobacco smokers and different from nonsmokers; compared with

MJ smokers had more of the following compared tobacco smokers

with nonsmokers: columnar cells (P⬍.01),

metaplastic cells (P⬍.01), reactive columnar cells

(P = .03), and purse cells (P = .01)

Starr and Renneker26; Regular MJ smokers MJ (n = 75) smokers show higher levels of Non–tobacco smoking 10.5

case-control (smoked at least twice metaplastic cells, macrophages, pigmented MJ smokers

weekly) for ⬎2 y macrophages, and columnar cells (P⬍.05) compared with

compared with nonsmokers and lower levels of tobacco smokers

neutrophils (P = .005) and pigmented

macrophages (P⬍.001) compared with tobacco

smokers; dysplasia noted in 2 tobacco smokers, 1

MJ smoker, and no nonsmokers

The 19 studies on marijuana smok- unteers presenting with respiratory tract Studies described marijuana expo-

ing and lung cancer that met our criteria symptoms at a clinic,30,33 volunteer surf- sure using a variety of methods, includ-

for inclusion had diverse study designs ers,26,27 and patients recruited at hospi- ing frequency, duration, and quantity

that included 4 experimental stud- tal admission or outpatient clinic vis- (Tables 2, 3, 4, 5, and 6). Most stud-

ies,15-18 5 prospective cohort studies (all its.24,25,31,32 Five studies15-18,34 did not ies defined marijuana use as current

involving a similar cohort),19-23 2 retro- specify recruitment procedures. Approxi- smoking of marijuana, with an average

spective cohort studies, 24,25 6 case- mately 50% of these studies reported the of more than 10 marijuana cigarettes per

control studies,26-31 and 2 case series.32,33 ages of subjects (mean age, 32.5 years week for 5 or more years.19-23,29

Study subjects included those who re- [range, 20.4-63 years]). Roughly 75% of Premalignant and lung cancer out-

sponded to newspaper advertisements the studies reported the subject’s sex comes included those with (1) prema-

and radio announcements,19-23,29 army vol- (male, 43.9%; range, 43%-100%). lignant associated changes such as tar

(REPRINTED) ARCH INTERN MED/ VOL 166, JULY 10, 2006 WWW.ARCHINTERNMED.COM

1361

©2006 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.Table 4. Studies Reporting Marijuana (MJ) Use Exposure and Alveolar Macrophage Effects

Male Participants,

Source; Study Type No. (%) Age (SD), Range, y Setting Outcome

Baldwin et al19; cohort 56 (71.4) 34.4 (8.4), 21-49 Metropolitan Los Angeles Alveolar macrophage tumor

cytotoxicity assays

Sarafian et al34; case-control 20 (NP) NP NM (assumed Los Angeles BAL alveolar macrophage

metropolitan area) oxidative stress

Sherman et al29; case-control 52 (NP) 26.8-41.4 Newly recruited or from existing DNA damage, superoxide anion

cohort production, nitrite production

Cannabis Confounders Mean Study

Source; Study Type Exposure Results Controlled Quality Score

Baldwin et al19; cohort Smoked MJ for at Alveolar macrophages from MJ smokers Non–tobacco-smoking 11.5

least 5 d/wk for 5 y were limited in their tumoricidal ability MJ smokers

(P⬍.01) compared with nonsmokers

Sarafian et al34; case-control ⬎10 MJ cigarettes/wk BAL from habitual MJ smokers revealed Non–tobacco-smoking 7

for ⱖ5 y GSH levels that were 31% lower than MJ smokers and

cells from nonsmokers (P⬍.03) controls

Sherman et al29; case-control ND Alveolar macrophages recovered from MJ MJ smokers compared 7.5

smokers, either alone or in combination with MJ ⫹ tobacco

with tobacco smoking, show a trend smokers

toward DNA damage

Abbreviations: BAL, bronchoalveolar lavage; GSH, glutathione; ND, not defined; NM, not mentioned; NP, not provided.

delivery15-18; (2) cytomorphologic ab- cal of marijuana users significantly in- MARIJUANA SMOKING

normalities in sputum26,27; (3) alveolar creased the percentage of retention AND CYTOMORPHOLOGIC

macrophage tumoricidal activity, DNA of inhaled tar in the lungs compared CHANGES IN SPUTUM

damage, and oxidative stress19,29,34; (4) with shorter breath-holding time in SPECIMENS

histopathologic and molecular alter-

ations in bronchial biopsy speci-

tobacco smokers (P⬍.001). In a study

mens20-23,30,33; and (5) lung or respiratory of 15 male participants, smoking Two case-control studies26,27 exam-

tract cancer diagnosed radiographi- marijuana resulted in a 3-fold in- ined marijuana smoking and spu-

cally or histopathologically.24,25,31,32 crease in amount of tar inhaled tum cytomorphologic changes in ha-

The heterogeneous nature of the (P⬍.001) compared with smoking bitual marijuana smokers without

studies and their outcomes precluded tobacco.18 The amount of tar deliv- current or prior use of tobacco

quantitative synthesis (eg, a meta- ered and deposited in the lung was (Table 3). These studies26,27 noted

analysis); therefore, this review fo- reduced in the most potent mari- that non–tobacco-smoking mari-

cuses on a qualitative synthesis of the juana compared with the less po- juana smokers had more metaplas-

data. tic cells, macrophages, pigmented

tent marijuana preparation, which

suggests that there is reduced expo- macrophages, and columnar cells

RESULTS sure to carcinogenic components in compared with nonsmokers. In an-

the tar phase of marijuana with higher other study, 17 dysplasia was ob-

MARIJUANA SMOKING THC content.15 Increased tar expo- served in 3 of 25 tobacco smokers,

AND TAR EXPOSURE sure in the proximal half of the mari- 1 of 25 marijuana smokers, and none

juana cigarette compared with the of the 25 nonsmokers. Conversely,

Tar is particulate matter residue from distal half (P⬍.05) was also noted, lower mean levels of neutrophils and

smoke and includes carcinogens. Tar which suggests that smoking fewer pigmented macrophages were ob-

exposure results from marijuana marijuana cigarettes to a shorter served in marijuana smokers com-

smoking and may serve as a poten- length results in a greater delivery of pared with tobacco smokers.

tial mediator of lung carcinogen- tar to the respiratory tract relative to These studies suggest overall in-

esis. In general, 4 experimental stud- a comparable amount of marijuana creased pathologic changes, in par-

ies demonstrate that marijuana from more cigarettes smoked to a ticular metaplastic changes, in se-

smoking is associated with in- longer butt length.16 lect populations of marijuana

creased tar delivery to the lungs com- This literature supports an in- smokers compared with tobacco

pared with cigarette smoking; fur- creased exposure to tar in marijuana smokers and nonsmokers.

thermore, there are several factors smoke compared with tobacco smoke

that affect the degree of tar expo- based on comparable amounts of MARIJUANA SMOKING

sure from smoking marijuana 13 smoked contents and increased tar ex- AND ALVEOLAR

(Table 2). A study17 examining the as- posure associated with decreased MACROPHAGE EFFECTS

sociation between marijuana smok- marijuana potency in the proximal

ing and tar exposure indicated that portion of a marijuana cigarette com- Studies evaluating the associations be-

the longer breath-holding time typi- pared with the distal portion. tween marijuana smoking and alveo-

(REPRINTED) ARCH INTERN MED/ VOL 166, JULY 10, 2006 WWW.ARCHINTERNMED.COM

1362

©2006 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.Table 5. Studies Reporting Marijuana (MJ) Use Exposure and Bronchial Biopsy Histopathologic and Molecular Alterations

Male Participants,

Source; Study Type No. (%) Age, y Setting Outcome

Barsky et al20; cohort 104 (77.9) Range, 21-50 Metropolitan Los Angeles Histopathologic and molecular alteration in

bronchial epithelium in habitual smokers

of marijuana, cocaine, and/or tobacco

(bronchial biopsy and brush specimens)

Fligiel et al22; cohort 70 (NP) NP Metropolitan Los Angeles Bronchial biopsy specimens, examining for

epithelial changes and basement

membrane changes

Fligiel et al21; cohort 241 (83) NP Metropolitan Los Angeles Bronchial biopsy specimens, light

microscopic evaluation

Gong et al23; cohort 37 (85) NP Metropolitan Los Angeles Bronchial biopsy specimens, examining for

epithelial changes, basement membrane

changes, and submucosal inflammation

Henderson et al33; n = 200, 6 of whom NP Army medical facility. Came Bronchial biopsy specimens

case-control underwent to facility with respiratory

bronchoscopy, 100% complaint related to

high-dose hashish use

Tennant30; 36 (100) Mean, 20.4 US soldiers stationed in Bronchial biopsy specimens showing

case-control (range, 17-22) West Germany atypical cells, basal cell hyperplasia,

squamous metaplasia

Cannabis Confounders Mean Study

Source; Study Type Exposure Results Controlled Quality Score

Barsky et al20; cohort Current smoking of MJ with MJ-only smokers (n = 12) had more frequent MJ smokers non–tobacco 11

an average of ⬎10 MJ histopathologic abnormalities than smokers and compared

cigarettes/wk for ⱖ5 y nonsmokers: squamous metaplasia with a tobacco smoking

(P⬍.001), cell disorganization (P⬍.001), group

nuclear variation (P⬍.001), mitotic figures

(P⬍.001), increased nuclear-cytoplasmic

ratio (P⬍.001), MJ smokers had more

abnormal expression of Ki-67 (P⬍.01) and

EGFR (P⬍.01) compared with nonsmokers

Fligiel et al22; cohort Smoking of MJ with an Tobacco, cocaine, and marijuana smokes had MJ smokers non–tobacco 10

average of ⬎10 MJ severe effects on histopathologic alterations; smokers and compared

cigarettes/wk for ⱖ5 y abnormalities were more commonly seen in with a tobacco smoking

MJ-tobacco smokers as opposed to tobacco group

smokers; compared with nonsmokers, MJ

and tobacco smokers more often had

squamous metaplasia (P⬍.001)

Fligiel et al21; cohort Current smoking of MJ with Effects of MJ and tobacco on bronchial MJ smokers non–tobacco 11.5

an average of ⬎10 MJ histopathologic findings is additive; those smokers and compared

cigarettes/wk for ⱖ5 y who smoked MJ only had more frequent with a tobacco smoking

histopathologic abnormalities than group

nonsmokers: squamous metaplasia

(P⬍.001), stratification (P⬍.001), cell

disorganization (P⬍.05), mitotic figures

(P⬍.001), increased nuclear-cytoplasmic

ratio (P⬍.001)

Gong et al23; cohort Current smoking of MJ with MJ smokers have more abnormal airway MJ smokers (non–tobacco 9.5

an average of ⬎10 MJ appearance and histopathologic alterations smokers) compared with

cigarettes/wk for ⱖ5 y irrespective of tobacco use; MJ smokers had tobacco only smokers

more basal cell hyperplasia (P⬍.009)

compared with nonsmokers; MJ smokers had

more cellular disorganization (P⬍.03)

compared with tobacco smokers

Henderson et al33; Heavy hashish smokers All 6 MJ smokers who underwent bronchoscopy Tobacco smoking not taken 1.5

case-control had mucosal injection, and all biopsy into account

specimens had epithelial abnormalities

Abbreviations: EGFR, epidermal growth factor receptor; NP, not provided.

lar macrophage function, DNA dam- alveolar macrophages recovered from ered from marijuana smokers with

age, and oxidative stress consisted of marijuana smokers were severely lim- and without tobacco exposure were

1 cohort study19 and 2 case-control ited in their ability to kill tumor cells more likely to show DNA damage;

studies29,34 (Table 4). A study involv- (P⬍.01) compared with nonsmok- however, results were not statisti-

ing a prospective cohort revealed that ers.19 Alveolar macrophages recov- cally significant. 29 In a separate

(REPRINTED) ARCH INTERN MED/ VOL 166, JULY 10, 2006 WWW.ARCHINTERNMED.COM

1363

©2006 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.Table 6. Studies Reporting Marijuana (MJ) Use Exposure and Other Lung Cancer Outcomes

Male

Participants, Mean Age

Source; Study Type No. (%) (Range), y Setting Outcome

Sasco et al24; case-control 353 (97) 59.3 Hospital-based, Morocco Lung cancer diagnosed radiographically and/or by

lung biopsy, other diagnostic biopsy, or

exfoliated cells

Sidney et al25; cohort 64855 (43) 33 (15-49) Health plan, early 1980s, Incident smoking-related cancers (upper

Northern California aerodigestive, lung, pancreas, kidney, bladder)

Sridhar et al31; case-control 110 (54) 60.5 (27-87) Oncology clinic, University of Lung cancer

Miami Medical Center

Taylor32; case series 10 (60) (28-39) Hospital; no exclusion criteria; Respiratory tract malignancy

no control for tobacco

Cannabis Confounders Mean Study

Source; Study Type Exposure Results Controlled Quality Score

Sasco et al24; case-control Use of hashish/kiff Lung cancer OR with hashish/kiff use as relevant Statistical adjustment 14

(Moroccan hashish) exposure: 1.93, (95% CI, 0.57-6.58) after for tobacco smoke

controlling for tobacco use, with

hashish/kiff/snuff use the lung cancer:

OR: 6.67 (95% CI,1.65-26.90)

Sidney et al25; cohort Smoked MJ ⬎6 times Past and current use of MJ was not associated Controlled for tobacco 11

ever or current MJ with an increased risk for cancer of all sites: use

smoker male OR, 0.9 (95% CI, 0.5-1.7); female OR,

1.1 (95% CI, 0.5-2.6)

Sridhar et al31; case-control Smoked MJ sometime in 13 (100%) of 13 patients with lung cancer Tobacco use not taken 6

their life ⬎45 y reported ever smoking marijuana vs 6 into account

(6%) of 97 ⬎45 y; P⬍001; self-report

Taylor32; case series Defined as heavy use Surgical pathologic specimens collected; 7 of 10 Tobacco use not taken 3

(daily use) and regular patients with respiratory tract malignancy had into account

use (frequent but less a history of regular to heavy MJ use

than daily use)

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; OR, odds ratio.

study,34 bronchoalveolar lavage from smoking; 4 were cohort-based stud- quently in marijuana smokers

habitual marijuana smokers re- ies20-23 and 2 were case series30,33 compared with nonsmokers.20 A

vealed glutathione levels that were (Table 5). All reported an increase separate study concluded that all

31% lower than cells from non- in abnormal and precancerous find- types of smokers (those who smoked

smokers (P⬍.03), as well as a dose- ings in marijuana smokers com- tobacco, cocaine, and marijuana)

dependent relationship between THC pared with controls who smoked had abnormal histopathologic find-

content and reactive oxygen species tobacco20-23,30 or controls with un- ings; specifically, marijuana smok-

generation. specified tobacco exposure.33 Ob- ers were more likely to have patho-

These studies demonstrate that servational cohort studies dem- logic bronchial mucosal alterations

alveolar macrophages from mari- onstrated a relationship between compared with nonsmokers.21 In this

juana smokers had less tumoricidal marijuana use and abnormal bron- study, mucosal and basement mem-

ability, increased likelihood of DNA chial disease.20-23 One study demon- brane changes were observed with

damage, lower glutathione levels (en- strated that marijuana-only smok- a greater frequency in the marijuana-

hanced oxidative stress), and a dose- ers had more frequent abnormal smoking group than the tobacco-

dependent relationship between THC histopathologic findings than non- smoking group. Marijuana smok-

and reactive oxygen species when smokers with a significant associa- ers demonstrated more frequent

compared with nonsmokers. tion between marijuana use and histopathologic alterations com-

pathologic changes, including squa- pared with nonsmokers in 8 of the

MARIJUANA SMOKING mous cell metaplasia and increased 11 pathologic categories, and the ef-

AND HISTOPATHOLOGIC mitotic figures.20 Compared with fects of marijuana and tobacco

AND MOLECULAR nonsmokers, marijuana smokers smoking seemed to be additive.21

ALTERATIONS ON BRONCHIAL were noted to more commonly have This literature supports the con-

BIOPSY FINDINGS abnormal expression of Ki-67, a pro- clusion that marijuana smokers were

liferation marker. Epidermal growth more likely to have basal, goblet, and

There were 6 studies evaluating his- factor receptor, a surrogate marker squamous cell hyperplasia; stratifi-

topathologic and/or molecular al- for lung malignancy and a poten- cation; cell disorganization; nuclear

terations from bronchial biopsy find- tial cause for the histopathologic al- variation; an increased nuclear-

ings associated with marijuana terations, was also noted more fre- cytoplasmic ratio; basement mem-

(REPRINTED) ARCH INTERN MED/ VOL 166, JULY 10, 2006 WWW.ARCHINTERNMED.COM

1364

©2006 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.brane thickening; squamous cell (range, 9-12); for the 5 prospective servational studies fail to demon-

metaplasia; mitotic figures; abnor- cohort studies, 10.75 (range, 9.5- strate a clear association between

mal expression of a proliferation 11.5); for the 2 retrospective co- marijuana smoking and diagnoses of

marker, Ki-67; and increased epi- hort studies, 8.5 (range, 6-11); for lung cancer. Therefore, we must

dermal growth factor receptor com- the 6 case-control studies, 9.0 (range, conclude that no convincing evi-

pared with nonsmokers.20-23,30,33 The 3.5-14); and for the 2 case series, dence exists for an association be-

effects of marijuana and tobacco 2.25 (range, 1.5-3). tween marijuana smoking and lung

smoking seemed to be additive ac- cancer based on existing data.

cording to 1 study.21 Nonetheless, certain logistic prop-

COMMENT

erties of marijuana smoking may in-

MARIJUANA SMOKING crease the risk of carcinogenic expo-

AND LUNG CANCER These 19 diverse studies offer bio- sure compared with conventional

logical evidence for the potential as- tobacco smoking, raising questions as

Studies examining the association of sociation between marijuana smok- to why observational studies have not

marijuana smoking and diagnoses of ing and lung cancer. Most studies demonstrated an association with

lung cancer included 1 large retro- support an association between mari- lung cancer. These properties in-

spective cohort study (n=64855),25 juana smoking and premalignant lung clude the association of marijuana

2 case-control studies,24,31 and 1 case cancer findings, although small ob- smoking with a deeper inhalation

series32 (Table 6). The cohort study servational studies fail to demon- technique in conjunction with greater

demonstrated that past and current strate such an association. In particu- puff volume and length of inhala-

use of marijuana was not associ- lar, all of the studies that measure tar tion, which presents an increased like-

ated with an increased odds of lung exposure support increased tar reten- lihood of enhanced exposure. Mari-

cancer, after adjusting for tobacco tion with marijuana smoking com- juana smoke also contains similar

use in men (odds ratio [OR], 0.9; pared with tobacco smoking. The carcinogens as tobacco smoke, such

95% confidence interval [CI], 0.5- higher lung tar burden associated with as nitrosamines; phenols; alde-

1.7) or women (OR, 1.1; 95% CI, the longer breath-holding character- hydes; polyvinyl chlorides; and

0.5-2.6). 25 A case-control study istic of marijuana smoking may en- polyaromatic hydrocarbons, such as

(n=353) found the odds of lung can- hance carcinogenic risk based on benzopyrene, which occurs in higher

cer in users of hashish or kiff to be prior studies that have demon- concentrations in marijuana smoke

1.93 (95% CI, 0.57-6.58) after con- strated an association between tar ex- compared with tobacco smoke.4,13 The

trolling for tobacco use.24 Among pa- posure from tobacco smoking and biological plausibility of an associa-

tients younger than 45 years with lung cancer.35-37 tion of marijuana smoking and lung

lung cancer, marijuana smoking was In addition, there were more cy- cancer is supported by experimental

reported in 13 (13.4%) of 97 com- tomorphologic changes, in particu- studies, including induction of path-

pared with 6 (6.2%) of 97 among pa- lar metaplasia, alveolar macro- ways known to be key steps in the de-

tients older than 45 years (P⬍.001), phage tumoricidal dysfunction, velopment of tobacco-related can-

demonstrating an uncharacteristic enhanced oxidative stress, and his- cers.28,42-44 Furthermore, unlike most

presentation of lung cancer in young topathologic/molecular alterations tobacco cigarettes, marijuana is typi-

marijuana smokers compared with associated with marijuana smok- cally smoked without a filter. Experi-

older marijuana smokers, which sug- ing compared with controls or those mental studies support a marijuana

gests that marijuana exposure may who smoked tobacco. These find- exposure–lung cancer association; a

accelerate the malignancy latency pe- ings offer biological evidence that study involving lung cancer cell lines

riod.31 However, most subjects in this marijuana smoking could be asso- demonstrated THC-induced prolif-

cohort were also tobacco smokers, ciated with the development of lung eration of cancer cells,9 and a mu-

and the investigators did not ac- cancer in humans, as has been sug- rine model suggested that THC pro-

count for this. A small case series gested by animal studies and cell line motes tumor growth.10

(n=10) reported respiratory tract ma- experiments. Specifically, metaplas- Giventhisbiologicalplausibilityfor

lignancy in association with mari- tic cellular changes may lead to ma- the enhanced risk of lung cancer as-

juana smoking; however, this re- lignant transformation. Abnormal sociated with marijuana, the observa-

port did not control for tobacco macrophage tumoricidal function tional studies reported thus far may

smoking.32 may result in unchecked cellular have failed to find such an association

These studies were not able to proliferation, and enhanced oxida- owing to methodologic limitations.

demonstrate a relationship be- tive stress has been described as a Most studies defined marijuana expo-

tween marijuana smoking and a di- mechanistic link in carcinogenesis suredichotomously,precludingdeter-

agnosis of lung cancer. presumably via mutagenic oxida- mination of relevant threshold effects

tive DNA damage.38-41 Bronchial his- or dose-response relationships. Limi-

STUDY QUALITY topathologic and molecular alter- tations of the studies reviewed over-

ations, such as those involving Ki-67 allincludethefollowing:selectionbias,

Overall, the mean quality score was and epidermal growth factor recep- small sample sizes, lack of adjustment

9.5 (range, 1.5-14) on a 31-point tor, may represent a harbinger of ma- for tobacco smoking, lack of blinding,

scale.14 The mean quality score for lignant conversion. Despite these inconsistent measurement of mari-

the 4 experimental studies was 10.75 findings, the small number of ob- juana exposure, lack of standardized

(REPRINTED) ARCH INTERN MED/ VOL 166, JULY 10, 2006 WWW.ARCHINTERNMED.COM

1365

©2006 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.surveillance of lung cancer diagnosis, participants who represent a wider Funding/Support: This study was

young age of study participants, and spectrum of ages with longer fol- funded by grants from the Robert

concernsregardinggeneralizibilityow- low-up periods. Continued re- Wood Johnson Foundation’s Pro-

ing to the use of similar cohort in 9 search on the pathophysiologic gram of Research Integrating Sub-

(47.4%) of 19 of the reviewed studies. mechanisms by which marijuana stance Use in Mainstream Health-

Of the 6 studies examining the asso- smoking may lead to development care (PRISM), the National Institute

ciationbetweenmarijuanauseandhis- of malignancy should provide in- on Drug Abuse, and the National In-

topathologic findings, 4 involved a sight into shared and convergent stitute on Alcohol Abuse and Alco-

similar prospective cohort.20-23 These pathways with tobacco-related lung holism administered by the Treat-

4 studies revealed a positive associa- cancer. The potential for additive or ment Research Institute. Dr Fiellin is

tion between marijuana use and pre- synergistic effects between mari- a Robert Wood Johnson Foundation

malignantbronchialdisease;however, juana and tobacco smoking, as sug- Generalist Physician Faculty Scholar.

given the similar cohort involved, the gested from this literature, de- Dr Moore is supported by NIDA R21

externalvalidityofthesefindingsisun- serves rigorous evaluation, especially DA019246-02. Dr Mehra is sup-

certain. In addition, the case-control given the significant comorbid ported by an American Heart Asso-

study evaluating marijuana smok- prevalence of these 2 behaviors. ciation National Scientist Develop-

ing with lung cancer outcomes may Large, prospective studies with de- ment Award (0530188N) and an

be limited by the definition of lung tailed assessment of marijuana ex- Association of Subspecialty Profes-

cancer because some diagnoses were posure and definitive pathologic di- sors and CHEST Foundation of the

made radiographically rather than by agnosis of lung cancer are also American College of Chest Physi-

tissue diagnosis, which may have led needed. A population-based case- cians T. Franklin Williams Geriatric

to misclassification bias.24 In this control trial that started in 1999 and Development Research Award. Dr

study, an OR of 1.93 (95% CI, 0.57- recently concluded has assessed the Crothers is supported by the Yale

6.58) assessing the strength of the re- association of marijuana smoking Mentored Clinical Scholar Program

lationship of marijuana use and lung and lung cancer involving cases (NIH/NCRR K12 RR0117594-01).

cancer was observed, and lack of a sta- identified via the Los Angeles Sur-

tistically significant relationship may veillance Epidemiology and End Re- REFERENCES

have been secondary to limited power sults registry and matched con-

to detect an effect as well as a poten- trols. This study45,46 with results 1. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Ad-

tial outcome misclassification.24 The forthcoming has incorporated mari- ministration. Results From the 2003 National Sur-

large cohort study (n = 64 855) in- juana exposure data collection in vey on Drug Use and Health: National Findings.

volving a retrospective review may joint years obtained via trained in- Rockville, Md: SAMHSA; 2004. National Survey

on Drug Use and Health Series H-25. DHHS pub-

be subject to recall bias because data terviewers in the home setting. lication (SMA) 04-3964.

were not prospectively collected to Although observational studies 2. National Cancer Institute. Cancer Progress Report

evaluate the exposure and outcome have not shown a substantive mari- 2003. http://progressreport.cancer.gov/doc.asp

variables of interest.25 In addition, the juana smoking–lung cancer associa- ?pid=1&did=21&chid=13&coid=33&mid=vpco.

Accessed September 12, 2005.

overall young age of the participants tion, these studies are fraught with se- 3. Compton WM, Grant BF, Colliver JD, Glantz MD,

(mean age, 33 years) poses a serious rious methodologic limitations. Stinson FS. 2004. Prevalence of marijuana use dis-

overall limitation of these studies Therefore, the combination of the orders in the United States: 1991-1992 and

because this may have precluded an widespread use of marijuana, poten- 2001-2002. JAMA. 2004;291:2114-2121.

adequate period of follow-up for the tial marijuana-related health impli- 4. Denissenko MF, Pao A, Tang M, Pfeifer GP. Pref-

erential formation of benzo[a]pyrene adducts at

development of a malignancy. Fi- cations outlined in this review, and lung cancer mutational hotspots in P53. Science.

nally, despite performing an exten- studies evaluating lung premalig- 1996;274:430-432.

sive literature search in 3 electronic nant alterations supporting a biologi- 5. Hoffman D, Brunnemann KD, Gori GB, et al.

databases, there is the possibility that cally plausible association between On the carcinogenicity of marijuana smoke. In:

Runeckles VC, ed. Recent Advances in Phyto-

relevant studies that were not pub- marijuana smoking–lung cancer as- chemistry. New York, NY: Plenum;1975: 63-81.

lished or not included in databases sociation, in addition to compelling 6. Novotny M, Merli F, Weisler D, Fencl M, Saeed T.

were missed. in vitro data not included in this re- Fractionation and capillary gas chromatographic

The findings of this systematic re- view, provide support for physician mass spectrometric characterization of the neu-

view have implications for research advice regarding the potential ad- tral components in marijuana and tobacco

smoke concentrates. J Chromatogr. 1982;238:

and clinical practice. Our assess- verse effects, including the potential 141-150.

ment of study quality reveals that fu- for premalignant lung changes, to 7. Tashkin DP. Smoked marijuana as a cause of lung

ture research directions should in- their patients that use marijuana. injury. Monaldi Arch Chest Dis. 2005;63:93-100.

clude increased adherence to 8. Galve-Roperh I, Sanchez C, Cortes ML, del Pulgar

TG, Izquierdo M, Guzman M. Anti-tumoral action

methodologic standards, more de- Accepted for Publication: April 9, of cannabinoids: involvement of sustained ce-

tailed assessment of marijuana ex- 2006. ramide accumulation and extracellular signal-

posure, larger sample sizes, adjust- Correspondence: Reena Mehra, MD, regulated kinase activation. Nat Med. 2000;6:

ment for tobacco smoking, uniform MS, Case Western Reserve Univer- 313-319.

surveillance for lung cancer diag- sity, 11100 Euclid Ave, Cleveland, 9. Hart S, Fischer OM, Ullrich A. Cannabinoids in-

duce cancer cell proliferation via tumor necrosis fac-

noses, multicenter evaluation, evalu- OH 44106-6003 (mehrar@ameritech tor alpha-converting enzyme (TACE/ADAM17)-

ation of dose-response relation- .net). mediated transactivation of the epidermal growth

ships, and involvement of study Financial Disclosure: None reported. factor receptor. Cancer Res. 2004;64:1943-1950.

(REPRINTED) ARCH INTERN MED/ VOL 166, JULY 10, 2006 WWW.ARCHINTERNMED.COM

1366

©2006 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.10. Zhu LX, Sharma S, Stolina M, et al. Delta-9- smokers of marijuana with and without tobacco. new index for estimating lung cancer risk among

tetrahydrocannabinol inhibits antitumor immunity Am Rev Respir Dis. 1987;136:142-149. cigarette smokers. Cancer. 1992;70:69-76.

by a CB2 receptor-mediated, cytokine-dependent 24. Sasco AJ, Merrill RM, Dari I, et al. A case-control 38. An Y, Kato K, Nakano M, Otsu H, Okada S, Ya-

pathway. J Immunol. 2000;165:373-380. study of lung cancer in Casablanca, Morocco. Can- manaka K. Specific induction of oxidative stress

11. Kogan NM. Cannabinoids and cancer. Mini Rev cer Causes Control. 2002;13:609-616. in terminal bronchiolar Clara cells during dimeth-

Med Chem. 2005;5:941-952. 25. Sidney S, Quesenberry CP Jr, Friedman GD, Tekawa ylarsenic-induced lung tumor promoting pro-

12. Melamede R. Cannabis and tobacco smoke are not IS. Marijuana use and cancer incidence (Califor- cess in mice. Cancer Lett. 2005;230:57-64.

equally carcinogenic. Harm Reduct J. 2005; nia, United States). Cancer Causes Control. 1997; 39. Kaynar H, Meral M, Turhan H, Keles M, Celik G,

2:21. 8:722-728. Akcay F. Glutathione peroxidase, glutathione-S-

13. Munson AE, Harris LS, Friedman MA, Dewey WL, 26. Starr K, Renneker M. A cytologic evaluation of spu- transferase, catalase, xanthine oxidase, Cu-Zn su-

CarchmanRA.Antineoplasticactivityofcannabinoids. tum in marijuana smokers. J Fam Pract. 1994; peroxide dismutase activities, total glutathione, ni-

J Natl Cancer Inst. 1975;55:597-602. 39:359-363. tric oxide, and malondialdehyde levels in

14. Downs SH, Black N. The feasibility of creating a 27. Roby TJ, Hubbard G, Swan GE. Cytomorphologic erythrocytes of patients with small cell and non-

checklist for the assessment of the methodologi- features of sputum samples from marijuana small cell lung cancer. Cancer Lett. 2005;227:

cal quality both of randomised and non-randomised smokers. Diagn Cytopathol. 1991;7:229-234. 133-139.

studies of health care interventions. J Epidemiol 28. Sarafian TA, Tashkin DP, Roth MD. Marijuana 40. Masri FA, Comhair SA, Koeck T, et al. Abnormali-

Community Health. 1998;52:377-384. smoke and Delta(9)-tetrahydrocannabinol pro- ties in nitric oxide and its derivatives in lung cancer.

15. Matthias P, Tashkin DP, Marques-Magallanes JA, mote necrotic cell death but inhibit Fas-mediated Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2005;172:597-605.

Wilkins JN, Simmons MS. Effects of varying mari- apoptosis. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2001;174:

41. Stringer B, Kobzik L. Environmental particulate-

juana potency on deposition of tar and delta9- 264-272.

mediated cytokine production in lung epithelial

THC in the lung during smoking. Pharmacol Bio- 29. Sherman MP, Aeberhard EE, Wong VZ, Sim-

cells (A549): role of preexisting inflammation and

chem Behav. 1997;58:1145-1150. mons MS, Roth MD, Tashkin DP. Effects of smok-

oxidant stress. J Toxicol Environ Health A. 1998;

16. Tashkin DP, Gliederer F, Rose J, et al. Tar, CO and ing marijuana, tobacco or cocaine alone or in com-

55:31-44.

Delta9THC delivery from the 1st and 2nd halves bination on DNA damage in human alveolar

42. Ammenheuser MM, Berenson AB, Babiak AE, Single-

of a marijuana cigarette. Pharmacol Biochem macrophages. Life Sci. 1995;56:2201-2207.

ton CR, Whorton EB Jr. Frequencies of hprt mu-

Behav. 1991;40:657-661. 30. Tennant FS Jr. Histopathologic and clinical ab-

tant lymphocytes in marijuana-smoking mothers and

17. Tashkin DP, Gliederer F, Rose J, et al. Effects of normalities of the respiratory system in chronic

their newborns. Mutat Res. 1998;403:55-64.

varying marijuana smoking profile on deposition hashish smokers. Subst Alcohol Actions Misuse.

43. Roth MD, Marques-Magallanes JA, Yuan M, Sun

of tar and absorption of CO and delta-9-THC. Phar- 1980;1:93-100.

macol Biochem Behav. 1991;40:651-656. 31. Sridhar KS, Raub WA Jr, Weatherby NL, et al. W, Tashkin DP, Hankinson O. Induction and regu-

18. Wu TC, Tashkin DP, Djahed B, Rose JE. Pulmo- Possible role of marijuana smoking as a carcino- lation of the carcinogen-metabolizing enzyme

nary hazards of smoking marijuana as compared gen in the development of lung cancer at a young CYP1A1 by marijuana smoke and delta (9)-tetra-

with tobacco. N Engl J Med. 1988;318:347-351. age. J Psychoactive Drugs. 1994;26:285-288. hydrocannabinol. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2001;

19. Baldwin GC, Tashkin DP, Buckley DM, Park AN, 32. Taylor FM III. Marijuana as a potential respira- 24:339-344.

Dubinett SM, Roth MD. Marijuana and cocaine im- tory tract carcinogen: a retrospective analysis of 44. Sarafian TA, Kouyoumjian S, Khoshaghideh F,

pair alveolar macrophage function and cytokine a community hospital population. South Med J. Tashkin DP, Roth MD. Delta 9-tetrahydrocannabi-

production. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1997; 1988;81:1213-1216. nol disrupts mitochondrial function and cell

156:1606-1613. 33. Henderson RL, Tennant FS, Guerry R. Respira- energetics. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol.

20. Barsky SH, Roth MD, Kleerup EC, Simmons M, tory manifestations of hashish smoking. Arch 2003;284:L298-L306.

Tashkin DP. Histopathologic and molecular alter- Otolaryngol. 1972;95:248-251. 45. Morgenstern HM. Marijuana use and the risks of lung

ations in bronchial epithelium in habitual smok- 34. Sarafian TA, Magallanes JA, Shau H, Tashkin D, and other cancers. National Institute of Drug Abuse

ers of marijuana, cocaine, and/or tobacco. J Natl Roth MD. Oxidative stress produced by mari- on Computer Retrieval of Information on Scientific

Cancer Inst. 1998;90:1198-1205. juana smoke: an adverse effect enhanced by Projects Web site. http://crisp.cit.nih.gov/crisp

21. Fligiel SE, Roth MD, Kleerup EC, Barsky SH, Sim- cannabinoids. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 1999; /CRISP_LIB.getdoc?textkey=2761718&p_grant

mons MS, Tashkin DP. Tracheobronchial histopa- 20:1286-1293. _num=1R01DA01138601A1&p_query

thology in habitual smokers of cocaine, marijuana, 35. Kaufman DW, Palmer JR, Rosenberg L, Stolley =&ticket=20721777&p_audit_session_id

and/or tobacco. Chest. 1997;112:319-326. P, Warshauer E, Shapiro S. Tar content of ciga- =92963459&p_keywords=. Accessed February 20,

22. Fligiel SE, Venkat H, Gong H Jr, Tashkin DP. rettes in relation to lung cancer. Am J Epidemiol. 2006.

Bronchial pathology in chronic marijuana smok- 1989;129:703-711. 46. Tashkin DP, Zhang ZF, Greenland S, Cozen W, Mack

ers: a light and electron microscopic study. J Psy- 36. Yoshie Y, Ohshima H. Synergistic induction of DNA TM, Morgenstern H. Marijuana use and lung can-

choactive Drugs. 1988;20:33-42. strand breakage by cigarette tar and nitric oxide. cer: results of a case-control study. American Tho-

23. Gong H Jr, Fligiel S, Tashkin DP, Barbers RG. Carcinogenesis. 1997;18:1359-1363. racic Society web site. http://www.abstracts2view

Tracheobronchial changes in habitual, heavy 37. Zang EA, Wynder EL. Cumulative tar exposure: a .com/ats06/. Accessed May 30, 2006.

(REPRINTED) ARCH INTERN MED/ VOL 166, JULY 10, 2006 WWW.ARCHINTERNMED.COM

1367

©2006 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.You can also read