Tallinn Film Cluster: Realities, Expectations and Alternatives

←

→

Page content transcription

If your browser does not render page correctly, please read the page content below

http://www.bfm.ee/about-bfm/bsmr-journal/

Article

Tallinn Film Cluster:

Realities, Expectations

and Alternatives

Indrek Ibrus, Tallinn University, Estonia; email: ibrus@tlu.ee

Külliki Tafel-Viia, Tallinn University, Estonia; email: ktafel@tlu.ee

Silja Lassur, Tallinn University, Estonia; email: silja@tlu.ee

Andres Viia, Tallinn University, Estonia; email: viia@tlu.ee

6Baltic Screen Media Review 2013 / Volume 1 / ARTICLE

Abstract

The article takes a close look at the entrepreneurial

practices of the Estonian film industry and at how these

particular practices may be understood to influence the

evolution of the film production cluster in Tallinn. It asks

how these processes of institutional evolution of the local

film industry may be understood to influence the specific

nature of audiovisual culture in contemporary Estonia.

The article is based on a study that was conducted in mid

2012. The study consisted of interviews with the repre-

sentatives of the local film industry, including respondents

from production companies (“studios”), post-production

companies and distributors. The second phase of the study

was a confirmative roundtable with the select group that

included the previously interviewed filmmakers and a

few additional industry insiders. The key research ques-

tions were: (1) what are the existing co-operation practices

between companies like and (2) considering the further

evolution of the industry cluster in Tallinn, what are the

companies’ specific expectations and needs. The current

status of the cluster’s competitiveness was evaluated by

using Michael Porter’s model for analyzing conditions of

competition (Porter’s diamond). Also, development per-

spectives of the cluster were evaluated, considering the

needs and expectations of entrepreneurs. Key results of the

research were divided into two basic categories: (1) current

state of clustering of AV enterprises and (2) perspectives

and alternatives of further development of the AV cluster.

Introduction The enhanced dynamism and productivity

Clusters of firms and other institutions that is also expected to spread within the clus-

contribute to the production of culture are tered industry and that is eventually ex-

important in at least two ways. Firstly, as pected to also spill over into related local

will be demonstrated below, they are ex- fractions of the economy, generating eco-

pected to strengthen the industrial base nomic growth in the region. Secondly, as it

of the production activities in terms of its has been emphasised especially within the

economic rationales – i.e. will facilitate an evolutionary economic approach to creative

increase in exchange dynamism and will industries (see Potts and Keane 2011), in

therefore condition additional surplus val- the case of creative industries such clusters

ue for all integrated production processes. have a potential to constitute the ground-

7Baltic Screen Media Review 2013 / Volume 1 / ARTICLE

work for a diverse and dynamic cultural potential of the Estonian film industry. The

milieu that provides the broader ‘national entrepreneurial practices within Estonian

innovation system’ with much needed cir- creative industries in general were inves-

culation of alternate ideas and reflections. tigated in 2011 (Tafel-Viia et al. 2011) in a

That is, creative clusters also have a poten- study that focused on the growth potential

tial for operating as purpose driven incu- of Estonian creative industries’ start-ups

bators for innovative artistic thought and housed in the relevant incubators in Tallinn

experiments, facilitating heightened artis- and Tartu. One of the findings of that study

tic and cultural dynamism in the particular was that compared to start-up companies

region or a city where the cluster is located of other subsectors of the creative indus-

in. It is due to such dual functionality of cre- tries the young micro-companies of audio-

ative clusters and their impact on general visual content production were relatively

societal evolution that they should be care- more inclined towards achieving growth and

fully studied. That is, an academic quest international operations. What is more, the

for evidence is in place, in order to inform film-sector start-ups were also more inter-

the relevant policy process in Estonia and ested in moving their operations to dedicat-

elsewhere. ed production facilities that could then also

The above-described rationale was operate as ‘physical infrastructures’ for the

also among the motivations for a study con- potential cluster. Our new study, presented

ducted in Tallinn, Estonia’s capital in 2012. here, expanded on these findings, the new

In more concrete terms, from the perspec- aim was to investigate the further potential

tive of Estonia’s leading institutions of the of cluster development in Tallinn, based on

audiovisual production sector (Estonian motivational varieties of all kinds of compa-

Film Institute, Film Estonia) there was a nies and institutions constituting the film

need for research into the clustering poten- production industry in Tallinn.

tial in Tallinn. The latter institutions there-

fore commissioned a two-part study from Overview of Estonian film

Tallinn University’s Estonian Institute for production sub-sector

Futures Studies. The present article reports Although only limited data exists on the

on the rationales and findings of that study. economic scale and scope of the Estonian

In more detail the aim of the study was to in- film industry, still the following sections are

vestigate the then existing realities of entre- aimed to contextualize our study by intro-

preneurial practices in the local film indus- ducing some of the basic economic data

try together with their potential cluster-like on the Estonian film sector. Most of the

relationships and other related tendencies. relevant information is taken from a recent

Such a study of clustering in the mapping of the Estonian creative indus-

Estonian film industry was to an extent un- tries conducted by the Estonian Institute

precedented. The operations and practices of Economic Research (2013).

of Estonian audiovisual content production

industries have been generally studied only Incomes

very little. In the last ten years the Estonian There were 363 companies of audiovisual

Institute of Economic Research has mapped content production (the statistic does not

the scope and structuring of Estonian separate between film and television pro-

creative industries including audiovisual duction) officially registered in Estonia in

content production sub-sector three times 2011 (138 companies more than 4 years

(2005, 2009, 2013)1 by mainly combining earlier, in 2007). The number of people em-

all the existing statistical and market data. ployed in the sub-sector in 2011 was 1092.

In 2007, a consultancy called Peacefulfish The gross income of the subsector was

conducted a cost analysis of the clustering €50.7 MM. Income from sales was €43.7

MM, constituting 86.3% of gross income.

1 See http://www.ki.ee/ Public funding for film production consti-

8Baltic Screen Media Review 2013 / Volume 1 / ARTICLE

tuted an additional 12.3% (€6.2 MM), local and 234 people were involved with screen-

governments contributed €27 000 (0.1%). ing films (operating cinemas). Turnovers

Lastly, production support from internation- were highest in screening business, produc-

al funds was 1.3% (€700 000). Gross profit tivity in post-production.

of audiovisual (AV)-sector companies was

€3.5 MM – constituting 0.08% of Estonia’s Films produced

private sector gross profit. At the same 187 films were produced in 2011. 25 of

time, AV-sector turnover constituted 0.12% these were “cinematographic films”, includ-

of private sector turnover in 2011 – the ing 13 “feature length” films, and 162 “video

difference pointing to comparatively lower films”. The 25 “cinematographic films” could

productivity in audiovisual content produc- be suggested to to be part of a standard

tion in relation to the rest of the economy. film industry value chain – i.e. films being

When it comes to public funding, screened in cinemas and sold on DVD/VOD.

the main funding agency is the Estonian The other “video films” were either advertis-

Film Institute (before 2013 known as the ing, promotional films or various produc-

Estonian Film Foundation) that distributes tions for TV.

money that mostly comes from the state

budget – in 2011 €3.1 MM for film produc- Audience

tion support. The second biggest contribu- The size of home market has been in Estonia

tor is the Estonian Cultural Endowment that as problematically tiny as elsewhere in

gets its funds mostly as a share of Estonian Europe. In 2011, Estonian films were watched

alcohol, tobacco and gambling taxes – in in cinemas by 172 290 people, which makes

2011 contributed to film-related activities 7% of all film consumption in cinemas. In

(not only production, but also support for 2012, the numbers were respectively 195 488

festivals, grants for travels, etc.) in the people and 7.6%. The most viewed Estonian

amount of €1,4 MM. The rest of state fund- film in cinemas was “Lotte ja kuukivi saladus/

ing comes straight from the budget of the Lotte and the Moonstone Secret” with

Ministry of Culture (€523 000 in 2011) 63 800 viewers – which took it to 6th place

together with some appropriations by the in the “most viewings” ranking list in Estonia.

Council of Gambling Tax (€12 000 in 2011). A year later the most viewed Estonian film

The main source of business revenues is was “Seenelkäik/Mushrooming” with 73 700

the production of TV commercials and other viewers and 4th place in the ranking. One of

TV content. Incomes from ticket sales, VOD the major challenges limiting the potential

(video on demand) services and DVD or growth of these numbers is the small number

license sales may vary, but is not always of regularly operating cinemas in the coun-

insignificant. Unfortunately, especially try. There was only 12 cinemas that operated

the latter three are currently unknown in the three biggest towns, elsewhere films

variables – there is no data available to were shown publically only irregularly – on

make justified assessments of their scales. semi-improvised screens and as secondary

activities in museums, theatres and other

Structure public buildings. The 12 cinemas in opera-

As elsewhere, the film industry is divided tion had altogether 74 screens, 15 of them

into the following sub-divisions: production digital (18 in 2012). The small number of dig-

(“studios”), post-production, distribution, ital screens undermines further efforts to

and cinemas. Out of these 198 companies strengthen the home market scale.

and 390 people were involved in producing With an approximate one-year delay, most

“films”; 64 companies (155 people) were films also make it to local TV channels where

busy with producing TV programmes; the audience numbers are normally multiplied

63 companies (160 people) were employed by tens, however the income to production

in post-production; 15 companies (25 peo- companies from these local TV license sales

ple) were doing distribution; 7 companies is normally financially insignificant.

9Baltic Screen Media Review 2013 / Volume 1 / ARTICLE

International reach Clusters in

There is no data comprehensive enough creative industries

on film-sector exports (both license sales Generally, economic clusters are considered

and services), but when it comes to inter- to be agglomerations of interconnected en-

national marketing efforts there is infor- terprises and organisations of an industry

mation of 9 “market screenings” at Cannes that are all located in the same geographi-

and Berlin film festivals (“The Graveyard cal area (Porter 1998). There are two main

Keeper’s Daughter”, “A Friend of Mine ”, schools of thought that provide the concep-

“Letters to Angel”, “Rattrap”, “Idiot”, “Farts of tualisation of a cluster. Firstly, an economic

Fury”, “Cubaton”). When it comes to festival approach that departs from a point of view

screenings 79 films were screened at inter- of economic statistics defines a cluster as

national festivals in 2011 (344 screenings an agglomeration of enterprises in a certain

altogether) and 185 films in 2012. territorial unit and focuses on how the links

between enterprises could be used more

Organisation and education efficiently. Alternatively, social scientists

There is a variety of institutions that and geographers tend to postulate sets of

shape, delimit and drive the film industry certain minimum requirements (concerning

in Estonia. The Estonian Film Institute as the types of relationships between enter-

the main funding agency, which also takes prises and the intensity of communication

care of some of its general development between them), the existence of which justi-

work (marketing, heritage digitisation, etc.) fies the application of the term ‘cluster’.

is normally perceived as the driver with These disciplinarily different ap-

clout when it comes to local production is- proaches to cluster conceptualisation have

sues. Film Estonia is the institution respon- not been mutually exclusive. Cluster con-

sible for marketing Estonia’s film produc- cept has widened as well as diversified over

tion services and also manages a post-pro- time. Several (additional) characteristics,

duction facility as a rental service. When it including deeper understanding of the

comes to self-organisation of professionals actors and their activity patterns, spectrum

and the industry then these processes are of goals of the cluster, different types of

very fragmented – there is a weak all-en- partnerships between cluster participants,

compassing Estonian Filmmakers’ Union etc. have emerged as analytically relevant

with mostly older generation filmmakers as when explaining the development of clus-

members and a multitude of smaller associ- ters. Gordon and McCann (2000) have dis-

ations for producers, directors, DOPs (direc- tinguished three different types of cluster

tors of photography), studios, documentary models that historically emerged at differ-

filmmakers, animators, etc. Such structuring ent points in time. The first is the classic

keeps the industry fragmented and hinders model of agglomeration based on either

its further integration, including potential local resources, demand or other advan-

clustering. An institution that may contrib- tages offered by the local economic envi-

ute towards integrating the industry is the ronment (Marshall 1925; Hoover 1948); the

regionally vital Tallinn University Baltic Film second is the neo-classical model that fo-

and Media School (BFM) – with its new pur- cuses on value chains based on direct eco-

pose-built house in downtown Tallinn that nomic links between enterprises (Moses

also accommodates two studios, as well as 1958; McCann 1995); and the third is post-

the post-production facility of Film Estonia. industrial social network or club model

BFM has a potential to function as a space based on social relationships and trust be-

that brings the industry professionals and tween the members of a cluster (Harrison

its offspring together. When it comes to 1992; Granovetter 1985). These different

industry evolution BFM with its more than approaches have also been somewhat

400 registered students is important in convergent; we may recognize that cluster

terms providing a trained workforce. models based purely on economic factors

10Baltic Screen Media Review 2013 / Volume 1 / ARTICLE

have evolved over time to include as well as fostering the export activities of

socio-cultural dimensions. enterprises. In terms of the development of

The researchers studying the specific a cluster, this signifies an opportunity for

nature of creative industries’ clusters more efficient local interactions and coordi-

(e.g. Pratt 2004; Roodhouse 2006; Davis nation of activities, but also for more direct

et al. 2009; Evans 2009a) tend to suggest links with related dynamics globally.

that compared to more conventional clus- In terms of the structure of the cultural

ters the objectives of creative clusters are labour market, one of the main character-

connected to either social or cultural goals istics of a network society is the increas-

in addition to economic and growth targets. ing individuation of the society, which may

Therefore, we propose that in order to strengthen the standing of individuals in

explore the evolution of the film cluster in labour relations, production processes and

Tallinn we need to analyse cluster charac- industry structures. Networks condition in-

teristics and the related developments on dividuation as the “nodes” of networks are

the one hand, and the specific peculiarities now constituted by the individuals rather

of actors (enterprises) in audio-visual sec- than different communities or institutions.

tor in particular, on the other hand. What is Managing the flow of information in a net-

more, in this article we take the approach work society is increasingly the responsi-

that an agglomeration of enterprises and bility of individuals, and consequently, the

organisations located in a common region same applies to labour relations and crea-

is only a potential cluster. We proceed from tive activities. In addition, the decreasing

an understanding that, for the formation of cost of technologies of media production

an actual cluster to take place, two parallel must be mentioned since this allows for

processes have to amplify each other: first, smaller production units that replace the

economic cooperation between enterpris- huge studios and other “industrial” produc-

es and, secondly, communication between tion facilities of the past. Additionally, the

the key individuals of those companies that increasing specialisation within the knowl-

creates synergy and establish trust. edge-based industries must be taken into

Proceeding from the need to investi- account as this has led to the evolving com-

gate the relationships that constitute and plexity within creative industries – where

shape the modern creative clusters we pro- a specific service can often be acquired

pose that the specific networking dynamics from only a very small set of adequately

in such clusters and therefore the nature skilled individuals or enterprises. Also the

and evolutionary dynamics of clusters are dynamics characterising most media mar-

also affected by an ongoing socio-cultural kets – that these tend to evolve towards oli-

circumstance, i.e. the evolution of the “net- gopolistic structures – may often condition

work society” (Castells 1996; van Dijk 2006). that the sheer majority of companies in the

What this concept refers to is that most so- audiovisual sector is constituted by micro-

cietal relationships tend to be structured by sized independents. Resulting from all the

the Internet as an infrastructure that condi- aforementioned causes, the audio-visual

tions people to form networks for almost all sector of the network age consists increas-

activities regardless of whether it includes ingly of micro-enterprises with only a few

production, consumption or experiencing. employees.

The paradox of networks lies in their strong One of the consequences of this for

ties to a location but also in their irrevers- creative entrepreneurs is that planning

ible connection to the largest of global net- their career and securing an income entails

works. This causes all networks to func- a greater risk. Work is becoming unsteady,

tion at their most efficient on the local level irregular, temporary and project-based; of-

while being more or less directly influenced ten, individuals work part-time for several

by international dynamics, thus supporting companies fulfilling various roles. In this

individuals in making international contacts context, individuals always have less

11Baltic Screen Media Review 2013 / Volume 1 / ARTICLE

influence and power than larger communi- to grow together. On the other hand, it is the

ties to secure their jobs. At the same time, trust between individuals and the opportu-

Gill (2007) has pointed out a paradox that nity for like-minded people to create

creative individuals value this situation as something together.

one that allows for more freedom and inde- The former aspect (overlapping of

pendence. However, it must be understood human and business relationships) is con-

that the individuation of a network society nected to the statements about the wider

is not of the isolating kind but the trend is horizontalisation of relationships in the

instead towards a “hyper-social society”. creative sector. Wirtz (2001), among others

“Networking” or the conscious creation and has suggested to that it is increasingly

managing of contacts is developing into the justified to talk about the complexity of

main method of managing risks involved in “value nets” instead of linear value chains.

individuation. Gill has demonstrated that “Co-opetition” is another well-known con-

conscious and purposeful networking strat- cept, which refers to the fact that coopera-

egies are characteristic of “independents” in tion and competition might not be mutually

a wide array of creative industries. exclusive in modern creative sectors. These

As several researchers (Banks et al. concepts must simultaneously refer to the

2000; Deuze 2007) have demonstrated, the increasing complexity of value chains and

central factor of such networking activities business models during the Internet age

is trust between creative individuals. As (plurality of parallel business models, their

mutual trust and habits of cooperation mutability and therefore the unclear bar-

develop, especially when the often project- gaining power of enterprises) and also to

based practices of creative industries is the horizontalising effect that the Internet

taken into account, we see the same or sim- is often considered to have.

ilar teams working on a string of projects. Based on this logic of increasing ambi-

Organising work in such a manner is very guity of relationships between micro-enter-

characteristic of producing audiovisual con- prises and on the related market uncertain-

tent. The fact that relationships in creative ties, Potts et al. (2008) have proposed a new

industries may directly condition how work concept for describing the modern creative

is organised points to the question of cor- industries. It is called “social network mar-

relation between the social relationships of kets”. This concept recognises that in the

individuals and the exchange relationships case of creative industries we must look

between enterprises in the sector. As ex- beyond the “industry”-centred interpreta-

plained above, creative sectors are charac- tion. The central characteristic of creative

terised by the importance of both of these industry is not the inputs and outputs of a

aspects: horizontal relationships between production process but first and foremost

people and vertical relationships (value the specifics of markets or more precisely

and supply chains) between enterprises. their ambiguity. The nature, value and ulti-

However, in the case of micro-enterprises, mately the prices of cultural products are

these verticals can almost overlap; this is always unknown variables to consumers

important because, as previously demon- and to a certain extent also to the produc-

strated, the Estonian film industry mainly ers themselves and therefore difficult to

consists of micro-enterprises. In other determine. Resultingly, the economic and

words, both economic and social dynamics financial relations are not easily stabilised

are behind the development of a cluster in creative industries and there is therefore

in the film industry. On the one hand, the also no place for price competition. This

economies of scope logic may lead to the ambiguity is alleviated by social networks

formation of clusters – the need to de- that link both producers and consumers. As

crease production costs while making pro- was previously mentioned, social networks

duction more efficient, the opportunity to are characterised by trust between their

discover synergy between enterprises and members and a certain similarity in value

12Baltic Screen Media Review 2013 / Volume 1 / ARTICLE

systems. Therefore, the central factors on a agglomerate in more organic ways as many

market full of ambiguities are the choices of creative projects are implemented one after

other trusted network members and recom- another in cooperation among loose sets of

mendations for consumption made on the creative individuals/micro-companies. Such

basis thereof. In the creative industries of clusters are therefore formed on the basis

the networking age, decisions to consume of real cooperation and existing dynamics

or produce are made primarily on the basis – where there is activity, more will follow if

of feedback from networks. the circumstances are right. Several stud-

Based on Potts and his colleagues, ies have demonstrated that it is relatively

contemporary creative industries should more characteristic of creative clusters to

not be interpreted simply as subsidised arts converge in a small territory (Lazzeretti et

or the “cultural industry” or “creative busi- al. 2008; Evans 2009a, b). The convergence

nesses” but as a large number of specific of creative enterprises often means they

goods and services that are always “new” are located on a single street or in the same

and without a clear “use value”. In order to quarter. Such spatial proximity is expected

determine their value, network participants to promote intense everyday communica-

must rely on the filtering capability of their tion between creative individuals and com-

social networks. Due to this, the adjusted panies. According to a widespread view,

definition of creative industries is as most creative clusters are de facto cultural

follows: “The set of agents in a market char- quarters and not economic clusters as de-

acterized by adoption of novel ideas within fined by Porter. Strong agglomeration is also

social networks for production and con- generally characteristic to AV companies

sumption” (Potts et al. 2008). The arts are al- that are, pursuant to geostatistics, some of

ways striving towards new representations the most highly concentrated companies

and are therefore valuable for the society in Europe. Over 60% of the enterprises have

and economy due to their ability to gener- converged to a certain territory; these clus-

ate new meanings and ideas; therefore, the ters are generally situated in capital cities

communicative dynamics of networks help and located in city centres (Boix et al. 2011).

to filter out the most valuable. Therefore, Similarly to the previously described proc-

the networks of the creative sector can esses, the formation of AV-industry clusters

be seen as coordinating mechanisms for is not so much dependent on the proximity

innovation processes. In this context the of their customers as on the higher concen-

evolution and the specific nature of creative tration of creative individuals and, therefore,

clusters as networking hubs can be consid- on the related socialisation opportunities in

ered significant in terms of generating an inspiring environment. What is more, con-

innovations with economic value as well as cerning the specific nature of clusters that

for facilitating broader cultural dynamics in have specialised in producing audiovisual

a particular culture/society. What is more, it content, Lorenzen (2007) has drawn several

is the dynamics of internet-mediated ‘social conclusions from his analysis of the world’s

network markets’ that can be suggested (large) film clusters about the aspects that

to facilitate the increasing emergence of ensure sustainability. Two of these aspects

‘virtual clusters’ in the creative industries. also have direct relevance for small clusters

Due to the dual functions of not only in small countries and also for the discus-

generating economic growth, but also cul- sions in this paper. The first of these is that

tural dynamism, creative clusters are not the frequency of cinema visits and the pur-

usually formed in the same manner as ge- chasing power of the home market influence

neric industrial clusters, the agglomeration the number of films produced. Secondly,

of which is often based on the strengths of public sector policy influences the home

the local markets or the existence of insti- market and the export of most film clusters.

tutions that develop technologies (universi- That is, the public sector policy is an im-

ties). In case of creative clusters, companies portant factor influencing the development of

13Baltic Screen Media Review 2013 / Volume 1 / ARTICLE

film clusters. However, there is still no un- either the owners of the companies or with

ambiguous data about which kind of inter- their senior executives (often having both

ference of the public sector helps the clus- roles).

ters achieve the best results. According to a The interview schedules consisted of

study of cluster initiatives (Sölvell 2003), it 57 questions divided between five sections:

is possible to presume that interference by (1) personal profile of the entrepreneur,

the public sector is more successful when a including educational background, social

contribution is made to an existing cluster activity, previous career; (2) the motives for

that has a relatively uniformly understood becoming an entrepreneur; (3) company

common vision about increasing its com- profile, including a) organizational structure

petitive edge. and management, b) business model such

In the light of the above, our study as competitiveness factors, pricing practice,

aimed to focus on the nature of the existing profile of the target group, market position,

companies in the film industry (their prac- and c) cooperation partners and forms;

tices, motives, capabilities and cooperation (4) the development perspectives of the

patterns). On the one hand, this is due to company, including the growth patterns and

the fact that organisations and networking strategies, activity plans, success factors;

are one of the most important factors from and (5) requirements from support

the point of view of cluster development; structure, including the practice of using

therefore, when assessing the potential of public sector support, the expectations

a cluster, it is important to consider how towards the cluster in terms of services,

“organic” the current cooperation of enter- location and members. Majority of the

prises and creative individuals belonging questions were open-ended; nine questions

to it is. had a finite set of predetermined answers.

All interviews were recorded and tran-

Methods of data scribed verbatim that resulted in 420 pages

collection and analysis of interview texts.

The data and findings presented in this The interviews were analysed using

article are based on the research project text analysis method and combining various

carried out in 2012. The data was collected coding practices (Hsieh 2005; Lahe-

using semi-structured in-depth interviews. rand 2008). Based on the grounded theory

The interview corpus was composed on approach the main themes (problems,

the basis of the following principles: (a) to opportunities, strengths, etc.) related to the

encompass representatives from all key film industry were identified and the typol-

subfields in the local film industry includ- ogy of enterprises was developed contain-

ing representatives of production com- ing three following types: growth-oriented

panies (“studios”), post-production com- enterprises; enterprises with features of

panies and distributors; and (b) to include growth-orientation; and lifestyle orientation

entrepreneurs with both shorter and longer enterprises. In the following, the situation of

entrepreneurship experience in order to clustering of Estonian film companies was

evaluate how the differences in the devel- analysed on the basis of “Porter diamond”

opment stages of the company influence framework (Porter 1990, 1998. 2001), which

the attitudes towards clustering. The final analyses the competitive advantage by us-

corpus formed by following the “snow-ball ing four factors: (1) factor conditions, (2) de-

method” (Atkinson and Flint 2004) and prin- mand conditions, (3) firm strategy, structure

ciple of corpus saturation – i.e. the number and rivalry, and (4) related and supporting

of respondents proves sufficient if one can industries. Factor conditions can be seen as

observe repetitive patterns in interview dis- advantageous factors found within a coun-

courses. Representatives of a total of 19 en- try that are built upon and further developed

terprises of the local film industry were in- by companies – for instance, highly skilled

terviewed. The interviews were made with workforce, the presence of necessary

14Baltic Screen Media Review 2013 / Volume 1 / ARTICLE

Factors Interview topics

Factor conditions a. Education and professional background of

the interviewee

b. Relevant factors of location for the company

c. Actualisation of intellectual property rights

d. Entrepreneurial environment and access to

finances

e. Relevant infrastructure

f. Financial incentives and entrepreneurial support

from public sector

Firm strategy, structure and rivalry a. Description of the company (age, employees,

structure, etc)

b. Description of the company’s business model

today and after three years

c. Competitive situation (advantages and

disadvantages of the company)

d. Cooperation models, -partners, -networks

Demand conditions a. Demand for the company’s products and/or

services

b. Market orientation (home vs. foreign)

c. Factors that hinder the demand

Related and supporting industries a. Cooperation partners in related industries today

and in the future

b. Reactions to the new possibilities

(e.g. derived from technological developments)

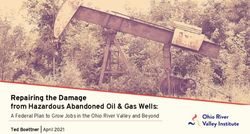

Table 1. Interview topics related to Porter’s four determinants.

Source: Study “The enterprises of the audiovisual sector – the situation and needs for clustering”;

conducted by the authors.

15Baltic Screen Media Review 2013 / Volume 1 / ARTICLE

infrastructure, established financing es regarding the competitiveness of the

mechanisms, etc. Demand conditions Estonian film cluster. Thirdly, we describe

describe the specifics of home-market the future alternatives for the Estonian film

demand for the products or services of the cluster. See also Figure 1 that describes our

particular industry. Firm strategy, structure interpretation of Porter’s four factors in the

and rivalry encompass factors such as how case of the Tallinn film cluster in more detail.

companies are organised and managed,

as well as the nature of domestic rivalry. Supportive factors of

Related and supporting industries concern Estonian film cluster

the presence or absence of supplier indus- The main supportive factors of the Estonian

tries and other related industries. The ad- film cluster can primarily be associated

vantage forms if these kinds of industries with two of Porter’s factors: the ‘factor

are closely intertwined, their actions are conditions’ and ‘firm strategy, structure

well coordinated, they work together for in- and rivalry’. Altogether the study identified

novation and achieving cost-efficiency. The six main aspects that speak for the forma-

interview topics corresponding to each of tion of a competitive film cluster in Estonia.

the four factors are presented in Table 1. Three of these relate to the business prac-

An analysis of the four factors was tices of Estonian film companies. The first is

used to assess the strengths and weak- the general growth orientation and interna-

nesses of the competitiveness of Estonian tional ambition of film companies. Although

film sector. After this the development the landscape of Estonian film is diverse –

alternatives for Estonian film cluster were consisting of tens of micro and small com-

identified that derive from the synthesis panies and representing a wide spectrum

analysis of the Porter’s factors. At this stage of different kinds of business models and

scenario analysis (Burmeister et al. 2002; activity patterns, the results indicate that

Heijden 1996) was used that enabled the about half of the respondents have plans

stimulation of alternative future perspec- for expansion – to develop the organisa-

tives. Eventually the most common model tion and increase the number of employees.

– the four-variant structure – was used. The Growth was normally seen to be generated

four alternatives were modeled by cross- by launching international operations and

ing two axes that reflect the most important entering foreign markets. Even those com-

variables or trends relating to the studied panies that exercise lifestyle-type business

phenomena. Our analysis proceeded in two models (characterised by having broader

steps. First, we identified the most diver- social goals, also non-monetary motivation-

gent opinions among the interviewees, and al factors and non-hierarchical structures

second, singled out the areas where the and informal relationships) considered in-

biggest development opportunities were ternational orientation important, at least

seen by the interviewees. in the future perspective.

The second factor relates to the coop-

Findings: Supportive eration pattern of Estonian film companies.

and deterring factors of The results indicate that film enterprises

the film cluster in Tallinn already have tight and functioning coop-

Although one can find supportive and eration patterns. People in the film sector

deterring aspects within each of the four are often engaged in each other’s projects,

of Porter’s factors, it can be suggested that, even managers or owners of a film com-

overall, some of these tend to be more pany are often involved as professionals

developed and influential than others. We (e.g. as DOPs, directors, editors, etc.) in the

introduce the findings in three parts. Firstly, projects of other film studios. Certain dif-

we present the main supportive factors ferences in cooperation patterns appeared

of clustering in the Estonian film sector. among companies with different business

Secondly, we introduce the main weakness- models. Growth-oriented companies

16Baltic Screen Media Review 2013 / Volume 1 / ARTICLE

(companies that intend to increase the qualified human resource. The majority of

number of employees, that consider hiring the respondents have graduated from uni-

a manager or have already done so, or that versity and two third of the interviewees

have an explicit growth strategy) represent had obtained education in audio-visual me-

rather stable teams on their own and coop- dia. However, a significantly small number

erate with other companies more on an or- of entrepreneurs have a business-related

ganisational level. The networking pattern education. Entrepreneurs evaluate their

among lifestyle-oriented companies again competences rather high, but this applies

is very variable, depending on projects and first and foremost to their film-related pro-

people. But irrespective of the business fessional competencies. The interviewees

model, cooperation works both in terms of also expressed rather systematically that

horizontal as well as vertical relationships. experienced and well-educated workers

Our study confirmed what was already stat- constitute their competitive advantage. The

ed in the literature overview: the creative well-qualified workforce in Estonia’s film

sectors (and potentially: clusters) are char- sector can, at least partly, be related to the

acterised by both kinds of relationships be- fact that a higher education institution of-

tween enterprises as well as professionals. fering film and media education is situated

Furthermore, the cooperation pattern in Tallinn. Tallinn University Baltic Film and

of Estonian film companies also follows the Media School can be considered a separate

co-opetition model. This indicates that co- factor supporting the further clustering of

operation and competition are not mutually Estonian film companies.

exclusive, on the contrary. One day the com- The clustering is also supported by

panies may compete for external financial the existing agglomeration of the Estonian

support, the next day they may be working film sector to Tallinn; moreover, most of the

together again on their next project. They are companies are located in the city centre or

‘colleague–competitors’ as one interviewee in its close neighbourhood. For most of the

said: companies, the most decisive factors when

choosing the location were: (a) good access

...in Estonia, we only compete with – both for employees and clients, (b) rea-

other companies at the same level – sonable rental price, and (c) the existence

in the sense that whether or not they of other companies of their kind nearby, the

have better ideas than us, so that ac- latter associates with typical creative clus-

tually we are in the same group with ter characteristics described previously. In

these companies, so we are colleagues addition, high-speed Internet, vibration free

and competitors, it is a positive com- environment, the height of the rooms and

petition /.../ we tend to see people with other similar factors were also considered

a similar competence as competitors, important. Quoting the interviewee:

they are in a similar situation, search-

ing for interesting ideas and think in Where we are located is extremely im-

the same way, at some point we will portant. Environment has to be such

share experiences and exchange ideas that you want be there and want to go

anyway; /.../ So in this sense, it is sort there, that inspires you. /…/ For us it is

of like challenging each other as col- important that we have a parking space

leagues in order to develop. [18]2 and that around us there are other crea-

tive people from other fields of art. And

The next three supportive factors relate in that we have a fast Internet connection.

different ways to Porter’s ‘factor conditions’. And that there is no electricity disrup-

The first is the relatively well-educated and tions or that rain would not pour in. [5]

2 The number refers to a respondent. Numbers were

given to grant respondents anonymity.

17Baltic Screen Media Review 2013 / Volume 1 / ARTICLE

Deterring factors of ronment is not favourable for film pro-

Estonian film cluster duction. This is the main problem that

The main factors deterring the further at the moment sets us on a weak

evolution of Estonian film cluster relate competitive position. [16]

primarily to Porter’s other two factors: first

of all the ‘demand conditions’, but also to Analysis of the demand situation also re-

‘related and supporting industries’. vealed one of the biggest differences among

‘Demand conditions’ of Porter’s dia- the film sector actors. There is a clear

mond turned out to be the most problem- distinction between film producers and

atic factor for the Estonian film cluster. The post-production companies. When the

study revealed that small local market and majority of film producers indicated that

low domestic demand are the most critical demand for their products or services is

factors, which impede the development of rather limited then all post-production

film cluster. More than half of the respond- companies admitted that demand for their

ents claimed that Estonian market is too services is high or even increasing.

small to make a living. Thus, the majority of The second hindering factor that sup-

film companies seek opportunities to orient presses the growth of domestic demand is

themselves to international markets (which the limited access to Estonian films by the

also explains the high rate of international local audiences. The small numbers of cin-

ambition of Estonian film entrepreneurs). emas operating across the country causes

International examples of successful film this. Currently there are cinemas that op-

clusters (although mostly outside Europe) erate daily in only the three largest cities

are predominantly supported by the notable in Estonia. The inability of inhabitants of

purchasing power of the domestic market. smaller towns to consider cinema-going

Demand for servicing foreign productions for entertainment (or enlightenment)

has also been rather modest. Although, purposes curbs the domestic demand for

several interviewed film entrepreneurs em- Estonian film. The interviewees empha-

phasised that servicing foreign produc- sised also that VOD services are still un-

tions in Estonia continues to be an under- derdeveloped. Only a few interviewed en-

used opportunity and a line of business trepreneurs indicated that a share of their

that has to evolve and should be promoted. income comes from digital distribution.

The respondents saw benefits especially Nevertheless, the majority of the respond-

in getting new experiences and contacts. ents saw that several new opportunities

At the same time, Estonia is positioned could emerge based on the further devel-

rather poorly compared to other countries opment of new media platforms and

in attracting foreign productions to film in distribution opportunities.

Estonia due to the lack of dedicated tax Certain shortages related to film pro-

exemptions in Estonia. duction infrastructure can also be consid-

ered as barriers to clustering. The interview-

What makes the situation difficult for ees claimed that, in general, the technology

us is that increasingly more countries and equipment necessary for film produc-

are offering tax exemptions to foreign tion are accessible to them. However, the

film producers. And as Estonia does absence of a proper large-scale film studio

not offer these, it may often happen together with related services was high-

that the producer chooses a studio lighted as a growth barrier to the Estonian

in a country that offers these exemp- film sector (including to servicing foreign

tions. So it may happen that won’t win productions in Estonia). The need for the

a competition and get some available new studio was also one of the topics

job not because we don’t measure up where the opinions of the interviewees

to quality- or pricing standard but be- diverged most often. One group of inter-

cause in our country the general envi- viewees argued that the new studio would

18Baltic Screen Media Review 2013 / Volume 1 / ARTICLE

be an important prerequisite for strength- one hand, the entrepreneurs consider it too

ening the sector’s capacity. The others were risky and, on the other, the banks are not

again sceptical about the cost-effective- eager to lend to markets that are generally

ness of the related investments. Even if perceived to be rather unpredictable for all

the Estonian film production sector would the aforementioned reasons.

attract more foreign productions to Estonia, The study also revealed that the

the numbers of local professionals to Estonian film sector significantly lacks ties

cover the whole flow of film production are with other sectors. When it comes to other

still limited – which would question the fields of art then strong and effective part-

rationale behind developing new expensive nerships have been built between film and

infrastructure. the performing arts – theatre and music.

Also, the dependence on public fund- The interviewees praised the cooperation

ing could be seen to hinder the clustering with actors and musicians and their um-

of Estonian film sector. In most cases, the brella organisations that have helped to for-

Estonian film production activities rely only malise clear standards, for instance, for re-

on public sector funds. There is no indica- muneration among other aspects. The links

tion that the volume of state funding could with other sectors and industries are sub-

increase in the (near) future, this in turn stantially weaker. However, closer coopera-

limits unavoidably the potential to increase tion with other sectors, especially with the

the volumes of the (local) audiences. information and communication technol-

ogy (ICT) sector, was seen as an opportunity

If about two or three motion pictures by the majority of the interviewees. When it

are produced in a year here, then they comes to such potentially interdisciplinary

just disappear into the rest of the cooperation then one of the hindrances is

mass and well, you must train a person also the lack of cooperation with research

to watch locally produced films in and development institutions. None of the

the same way. If we were to produce respondents in this study indicated that

8 films a year for 10 years, then people their company is cooperating with research

would sort of learn and grow to watch institutions.

these films. [2] One of the deterrents to clustering is

the relative weakness of the film-sector’s

There are only a few examples of involv- umbrella organisations – an aspect influ-

ing private sector finances (e.g. loans, in- encing its inherent coherence. There are

vestments, sponsorships). This can be ex- multiple associations and unions that as-

plained to an extent by the limited financial sociate themselves with the film sector in

competencies of film sector entrepreneurs. Estonia, but many of them are rather inac-

But this is also due to the small size of the tive. The interviewees argued that the um-

local market and other limitations to the lo- brella organisations are too fragmented

cal demand described above that may curb and do not speak with one ‘voice’. According

the motivations of potential investors. Also, to interviewees these are also of little use:

Estonian production companies tend to be they are especially weak in organising joint

focused on producing art house films rather cross-border activities, similarly in finding

than targeting either mass audiences with partners and fostering cooperation projects.

more entertainment oriented content or Still, one can observe several positive devel-

producing genre films (for instance horror, opments in the recent years. While the mul-

sci-fi) for the long tail of global niche audi- tiplicity of umbrella organisations contin-

ences. ues to keep the sector fragmented, new in-

When it comes to financial capabilities stitutions have emerged that have facilitat-

then the overall ability and openness of film ed new forms of joint international opera-

companies to take loans to support their tions. The establishment of Estonian Digital

development goals is rather modest. On the Centre and Estonian Film Commission both

19Baltic Screen Media Review 2013 / Volume 1 / ARTICLE

increase the reputation of Estonia as a companies, for example, and anima-

location for film production. tion studios and let us say sound stu-

dios, and then, that they are together

Development alternatives a group that produces material for TV

for Estonian film cluster and cinemas. Then there is the game

Here we introduce the possible develop- industry and the Internet industry that

ment alternatives for the Estonian film also use people with similar skills. [8]

cluster that were derived from the synthe-

sis analysis of Porter’s four factors. We start The second factor relates to the infrastruc-

by describing the two factors, which formed ture and environment conditions necessary

the basis for the construction of the devel- for cluster development. The need for the de-

opment alternatives. The first factor relates velopment of the infrastructure and environ-

to the diversity of actors and fields related ment that supports the development of the

to the cluster. On the one hand, several in- film sector was commonly understood and

terviewees expressed their doubts about valued, although the choices for that were

strengthening cooperation with other in- seen differently. One group of interviewees

dustries. Some of the interviewees even clearly favoured the development of physi-

questioned the need for strengthening the cal infrastructure, including the film pavilion.

cooperation within the audio-visual sector For them the lack of necessary infrastruc-

as film producers and television producers ture was a barrier to the film sector’s devel-

or film producers and post-production opment and the establishment of a physical

companies are supposedly different kind of edifice with contemporary technology would

actors with varying development needs. In bring growth opportunities for the film sec-

order to find solutions to the development tor. The other group of interviewees consist-

problems bigger fragmentation was seen as ed of those who, although they saw the need

a solution. Quoting an interviewee: for the development of a new production fa-

cility, doubted the cost-effectiveness of the

For me it is very important, for many investments. This was explained with the

film makers it is very important to rapidly changing technology and the low de-

draw a thick red line between film pro- mand for these technologies in real terms.

ducers and television producers. The

production specificity is too different. I am with those that think that we

So, if we have film producers then only don’t need to build (a studio) here. This

film producers. The associations for di- is such a bit naive dream. Close to us

rectors and screen writers pronounced similar things have been built, also

also that they don’t want to get in- Russians have built their own. But

volved with TV work since the work many I hear are staying empty. This is

specificity is different. [14] quite like: “let’s try, let’s invest!” But

this is too big to simply try out. I don’t

On the other hand, the cooperation with understand where is the enthusiasm

other fields was seen as an opportunity for of these people coming from? How are

strengthening the capacity and competi- they going to staff all these…? /…/ And

tiveness of the film sector. Collaboration long will the payback period be for this

was seen with the fields that offer syn- investment? [6]

ergy and amplification for film sector: ICTs,

games and media sector were mentioned On the basis of these two factors (axes) the

most often. study identified four development alter-

natives for Estonian film cluster (see also

I can see that there are many ele- Figure 2). The following describes the prin-

ments that create synergy between cipal characteristics of each of the four

companies. So let us take production alternatives.

20Baltic Screen Media Review 2013 / Volume 1 / ARTICLE

FACTOR FIRM STRATEGY, STRUCTURE AND RIVALRY

CONDITIONS + orientation towards internationalisation

+ educated and + tight cooperation between enterprises

competent human + cooperation and competition go hand

resources in hand

+ concentration to

the city centre – small and weak enterprises

+ accessibility of – project based activities predominantly

technology

+ state financing

system

+ Tallinn University

Baltic Film and

Media School

DEMAND

+/– Estonian Digital + development

Centre, Estonian of cross-media

Film Commission

– small home market

– lack of – missing Estonian

competences in wide cinema

marketing, financial network

and juridical fields – small international

– dependency of reputation

public sector

financing

– lack of private

investors

– missing film

pavilion

– fragmented and RELATED AND SUPPORTING INDUSTRIES

non-active + tight cooperation with creative industries

representative (performing arts)

organisations + television as a possible output channel

– lack of specific

support schemes, – weak cooperation with ICT enterprises

e.g. no tax (for the development of production technics

exemptions for film and technologies)

Figure 1. The strengths and weaknesses of the competitiveness of the

Estonian film cluster based on Porter’s diamond model.

21Baltic Screen Media Review 2013 / Volume 1 / ARTICLE

Alternative 1 – Studio based film clus- post-production and distribution) or to ex-

ter for film companies – is a cluster which pand and involve actors from other indus-

encompasses film sector companies with tries. Another fundamental choice is based

dedicated production facility. It aims to en- on the question of whether there is the need

hance cooperation efficiency among film for a built production facility that integrates

sector companies and improve the quality different actors or if the virtual network is

of film production and services. The actors enough to strengthen the cooperation with-

in the cluster cover the whole flow of the in the film sector as well as between film

film production process, from production to and other sectors.

distribution. The majority of the film sector

companies move to the new facility that is Discussion and

developed around a new large-scale studio policy suggestions

together with supporting services, includ- The purpose of this study was to evaluate

ing renting equipment, lightening, casting the ongoing clustering of film enterprises

services, sound engineering, post-produc- in Tallinn, and based on this, to assess the

tion services, distribution, etc. Alternative 2 prospects for the further development of

– Film with partners around the studio – is a a cluster. To conclude the results, it can

cluster which has similarly developed next be suggested that the AV-cluster forma-

to the new production facility, but it encom- tion in Tallinn is not going to slow down. The

passes not only film sector enterprises, but Estonian film industry can be characterised

also companies from several other fields by close horizontal and vertical relation-

such as online media, ICTs, television. The ships between the enterprises and creative

aim of the cluster would be to enhance in- individuals and also by their further readi-

ternational competitiveness of the whole ness to cooperate. Collaboration and com-

audio-visual sector in Estonia and the main petition go hand in hand: enterprises com-

potential is seen to emerge from the syn- peting for external funding at one moment

ergy of different industries located together. could be cooperating on another project

Alternative 3 – Cloud cluster for film compa- the next moment. Most of the entrepre-

nies – again encompasses solely film sector neurs in the Estonian film industry also be-

companies, but is a virtual-social network lieve that they can benefit from a cluster in

without a concentrating production facil- several ways. Entrepreneurs felt that the

ity. It proceeds from an understanding that cluster could play an important role in im-

in the context of limited resources the main proving business cooperation further and

effort for strengthening Estonian film clus- enhancing communication among indus-

ter capacity is to invest into improving the try fractions. This could also help gain bet-

information exchange, joint marketing and ter access to foreign funding and/or to en-

export activities instead of investing into able work on larger foreign projects. These

developing new infrastructures. Alternative aspirations are especially pronounced in

4 – Mixed community in the cloud – is also a the answers provided by the younger entre-

network-based cluster, but it encompasses preneurs in the industry. This may be due

several other fields besides film sector. It to their relatively smaller involvement in

aims to make use of the competencies and the social networks of the industry and the

synergies of different fields to support the slightly more marginal position of their en-

innovation in the audio-visual sector. terprises in the dynamics of the audiovisual

To summarise, all of the four alterna- industry so far. The further organic develop-

tives for the Estonian film cluster are based ment of the cluster is supported by the fact

on the enhancement of collaboration in the that enterprises have already agglomerated

film sector, but differ from the range of ac- in the centre of Tallinn and in the nearby

tors involved in that cooperation. The fun- district of Põhja-Tallinn (northern part of

damental question is whether to stay within the city). The majority of the interviewees

the frame of the film sector (together with expressed a need for better production

22You can also read