Sports Medicine FOR THE PRIMARY CARE PROVIDER - Hershey Medical Center

←

→

Page content transcription

If your browser does not render page correctly, please read the page content below

WINTER 2016

Sports Medicine F O R T H E P R I M A R Y C A R E P R O V I D E R

Concussions and Chronic Traumatic

Encephalopathy

BY MATTHEW SILVIS, M.D.

The recent movie “Concussion” has created quite a stir nationally about chronic traumatic

encephalopathy (CTE). This is written to help fellow providers understand what is known, and

just as importantly, unknown about this condition.

In 10 to 15 percent of athletes with concussion, symptoms last longer than 10 days and can

persist for weeks, months, or years after injury. Post-concussion syndrome is ill-defined, poorly

understood and currently explained as persistent symptoms or signs of concussion that persist

for weeks or months after concussion. ‘Time’ is the primary treatment for post-concussion Dear Health Care Provider,

syndrome, which is frequently frustrating for patients and providers, alike. A multidisciplinary My name is Matthew Silvis. I am medical

approach is recommended, including providers with experience in caring director of Penn State Primary Care Sports

for sports-related concussions and may also include pharmacologic Medicine. I have enclosed the winter edition

management, physical, vestibular, speech and occupational of our Primary Care Sports Medicine

therapies, neuropsychological evaluation and treatment, visio-ocular Newsletter, a biannual newsletter of seasonal

evaluation and treatment, and behavioral health, amongst others. sports topics. We hope you find the information

In recent years, there has been increasing media attention to useful and appreciate any feedback you have

sports-related concussion, specifically CTE. CTE is a progressive to enhance our efforts. We have selected a

neurodegenerative tauopathy associated with repetitive brain variety of topics for this issue.

injury. It was originally diagnosed in boxers

If you’d like to receive this newsletter by

more than 85 years ago. Research groups

email, please forward your address to my

have proposed that head injury, including

administrative assistant, Sandy Miland at

both concussive and subconcussive blows,

smiland@hmc.psu.edu. Please send any

leads to neuropathologic changes and

future topic ideas to Sandy or me at

the development of alterations in mood,

cognition and behavioral functioning. msilvis@hmc.psu.edu.

CTE can occur in as few as one blow to the

head and appears to develop from eight to Enjoy,

20 years following retirement from contact

sports. The diagnosis is made at autopsy and

is separate from permanent post-concussion Matthew Silvis, M.D.

syndrome. Initially, mood and behavior ASSOCIATE PROFESSOR

changes predominate with later clinical PENN STATE HERSHEY FAMILY AND COMMUNITY MEDICINE

presentations involving cognitive and PENN STATE HERSHEY ORTHOPAEDICS AND REHABILITATION

PENN STATE MILTON S. HERSHEY MEDICAL CENTER

CONT’D ON PAGE 2Skin Infections in Wrestlers

BY BY JESSICA BUTTS, M.D.

Wrestling season is upon us. Due to the nature of the sport, with brief, here is a listing with a few reminders:

near constant skin-to-skin contact, skin infections are a common

• Tinea corporis requires a minimum of 72 hours of topical antifungal;

issue encountered when caring for competitive wrestlers of all ages.

Fungal infections (e.g., ringworm), viral infections (typically herpes • Tinea capitis requires 10 days of oral antifungals;

gladiatorum caused by HSV-I) and bacterial infections (impetigo • Herpes gladiatorum requires treatment with an oral antiviral: 10 days

and MRSA) are all common offenders. As these infections are highly for initial outbreak and 120 hours for recurrence; all lesions must be

transmissible among these athletes, providers need to be vigilant with crusted over with no new lesions in the preceding 48 hours.

patients who wrestle and present with skin complaints. Many skin

infections, specifically those listed above, would disqualify the athlete • Bacterial skin infections need at least three days of oral antibiotics

until they have been properly treated. As these infections directly affect with all lesions scabbed.

their eligibility to participate, wrestlers may go to extreme measures All of this information, and more, can be found at the bottom of the

to hide the nature of their lesions. Applying bleach, using sandpaper PIAA wrestling skin form.

and excoriating (or picking) are all possible ways to hide or disguise

As we care for these athletes, being aware of how common these

disqualifying skin conditions. Therefore, providers who treat these

skin infections are in this population, as well as being aware of the

athletes need to have a very high level of suspicion for these conditions,

potentially atypical appearance of some of these lesions, is important.

as well as a low threshold to treat empirically if any of these conditions

Being familiar with the PIAA

are suspected.

guidelines for return-to-play

Completion of the PIAA “skin form” is universally required for all and having a low threshold to

wrestlers with any potentially contagious skin lesion to be allowed to treat keeps as many athletes in

participate. This form is infinitely useful to keep in any primary care the game (or in this case on

office setting where a “wrestler with rash” may present for evaluation. the mat) as possible.

This form identifies diagnosis, number and location of lesions, and

type and date of treatment initiated. This form is required at pre-

participation skin checks by any athlete who has had a skin evaluation

and treatment. Completion of this form by the provider at the time of

visit streamlines this process for the athlete, athletic trainer and medical

staff covering these events.

The PIAA form also outlines standard required treatment for common

skin infections to be eligible to return to play. These guidelines are

extraordinarily useful as they outline the minimum required treatment

for some of the most commonly encountered skin conditions. No

athletes with new lesions in the preceding 48 hours, or with lesions

that are oozing, draining or moist, will be permitted to participate. In

CONCUSSION FROM COVER

motor impairment. by other groups of neuropathologists. recent study demonstrated no increased

Interestingly, there is a greater incidence risk of neurodegenerative disease in a

However, CTE is poorly understood

of abnormal tau protein deposition in long-term follow-up study of high school

at this time. Athletes with significant

the brains of opiate abusers compared to football players versus a control group

neurologic symptoms do not always have

controls according to research studies. Of (band members). While providers and the

histopathologic changes of CTE, and

note, more than half of the players in the public are appropriately concerned, much

the presence of histopathologic changes

National Football League (NFL) have been is unknown about CTE and a definitive

of CTE is not always associated with

reported to use opiates during their NFL causal link to American football has yet

neurologic symptoms. Tau protein may be

careers with most reporting abuse, clouding to be determined. Future prospective,

found in individuals undergoing normal

the etiology of CTE. NFL players are less longitudinal, population-based studies

aging, independent of head trauma,

likely to die from suicide than the general are needed to better understand CTE. For

although some leading researchers report

population and there is no definitive link now, following standard-of-care in the

a qualitatively different deposition of

between CTE and suicide at this time. In management of athletes with concussion

abnormal tau protein in CTE versus other

fact, retired NFL players live longer than remains the best approach.

neurodegenerative diseases. However,

their age-matched peers. Additionally, one

this finding has not been cross-validated

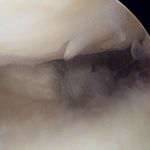

2When is a meniscal tear not a meniscal tear?

When it is a root avulsion!

BY ROBERT A. GALLO, MD

Meniscus tears come in all shapes and sizes. There are vertical tears,

horizontal tears, radial, and even complex tears which can include any

combination of these tear orientations. These conditions are managed

largely by the degree of symptomatology, tear orientation and location.

More recently, meniscal root avulsions (tears), a subset of meniscal

tears, have received increased attention in the orthopaedic community.

A meniscal root avulsion involves any disruption of the tibial

attachment sites of the menisci. While each meniscus has attachments

circumferentially to the knee capsule, the root insertions are located at

1 2

both the anterior and posterior ends of each meniscus. The meniscal

root attachments anchor each meniscus to the tibia and are essential

to the normal function of the meniscus as “shock absorbers.” With

a detachment of its root attachment, the meniscus loses the ability

to resist hoop stresses vital to its normal function. Therefore, the

downward force of the femoral condyles on the tibia causes the

meniscus to eventually extrude beyond the confines of the tibio-

femoral articulation (figure 1). Rapidly progressive osteoarthritis can

follow if the meniscus is unable to efficiently transmit load to the tibia.

While a meniscal root avulsion can occur in younger individuals

in a trauma setting, the majority occur in middle-aged adults. Most 3A 3B

patients recall incidents when they felt a “pop” and immediate

FIGURE 1: Extrusion of the meniscus beyond the border of the femoro-tibial

pain in the posterior medial or lateral aspect of the knee. Similar to articulation (line) occurs with prolonged weight-bearing following disruption of the

other meniscal tears, patients describe worsening pain with deep root attachment.

knee flexion; however, the pain is more posterior than meniscal FIGURE 2: Meniscal root tears are readily visualized as increased signal between the

tears involving the body and posterior horn of the meniscus. On meniscus and tibial (arrow) on T2-coronal MRI sequences.

examination, the hallmark physical examination finding is tenderness FIGURE 3: Meniscus root tears can be surgically repaired by passing sutures into the

to palpation of the joint line at the posterior aspect of the knee. meniscus, sending the sutures down a tunnel through the tibia, and tying the sutures

over a button on the anterior tibial cortex.

Imaging should begin with anteroposterior weightbearing, lateral

and Merchant radiographic views of the affected knee. If moderate

or severe osteoarthritis is identified on radiographs, treatment The post-operative limitations are fairly extensive and involve a period

should manage the symptoms of osteoarthritis. In cases of relatively of non-weight-bearing and immobilization.

preserved joint spaces, MRI should be considered if a posterior root Despite the theoretical advantages of surgical repair, long-term clinical

tear is suspected. While they can usually be visualized on any image data assessing healing, meniscal extrusion and the ability to slow the

orientation, meniscal root avulsions are most readily seen on coronal progression of arthritis are lacking. Therefore, repair should only be

images as an area of signal intensity between the posterior meniscus considered after careful evaluation, which includes assessment of the

and tibia (figure 2). amount of pre-existing osteoarthritis, level of disability and symptoms

The treatment for meniscal root avulsions has evolved over recent and body habitus (i.e., obese patients place increased stress on any

years. Because of recent biomechanical studies confirming the benefits repair and are more likely to fail the repair procedure). Intra-articular

of restoring the meniscal root attachment, repair of these avulsion-type steroid injections and physical therapy are useful alternative treatment

tears has become increasingly popular. Surgical repair involves the modalities.

following process: In conclusion, root avulsions are a unique category of meniscal tears

• passing a high-strength suture through the torn edge of the that must be considered a different entity than other meniscal tears.

meniscus; Presenting with posterior knee pain, meniscal root tears can render

the meniscus nonfunctional, resulting in increased joint reactive forces

• passing those sutures through a small tunnel beginning at the and leading to rapidly progressive osteoarthritis. Consultation to an

normal root insertion site and exiting along the anteromedial tibia orthopaedic surgeon should be considered in those with an MRI-

adjacent to the tibial tubercle; then diagnosed meniscal root tear and relatively well-preserved joint space,

• tying the sutures over a button on the anteromedial cortex of the as seen on anteroposterior weight-bearing radiographs.

tibia (figure 3).

3Helmets – A False Sense of Security?

BY JAYSON LOEFFERT, D.O. , PRIMARY CARE SPORTS MEDICINE FELLOW

However, there are types of head injuries that helmets have been

shown to prevent, including skull fractures and head lacerations.

Helmets can compress during impact, allowing some deceleration

and decreasing the direct force applied to the head. Unfortunately,

this does not translate to prevention of all types of head injuries,

namely traumatic brain injury and concussion.

The question then is why haven’t helmets had more of an impact

on preventing head injury? There are several hypotheses: First, it

has been widely demonstrated that helmet use does not eliminate

the risk of concussion. While helmets can absorb some impact

during a collision, they do not significantly reduce the acceleration

or deceleration and rotational forces resulting in concussion.

Additionally, helmets are not being tested at speeds consistent with

all usage environments. The average skier travels at a speed of 24.6 to

The colder weather brings with it the anticipation of snow, and, of 31.3 miles per hour, yet linear impact tests are conducted in the lab at

course, skiing and snowboarding! Over the last decade, the concern only 14.3 miles per hour. Going above the average speed could result

for injury and prevention has grown, and simultaneously, public in as much as a quadruple increase in subjected impact energy above

helmet use has skyrocketed: 6 to 25 percent in 2003 to 70 to 90 what the helmet is designed to protect. Therefore, helmets may not

percent in 2013. The purpose of this article is to educate fellow be designed to handle the forces they are subjected to in real-world

providers on the limitations of helmet use for preventing head injury, environments. Finally, the idea of increased risk-taking behavior due

as well as to warn against false security and over-assumption that to helmet use has been discussed. While the idea that helmets overtly

helmets prevent head injury. cause recklessness has been refuted, their use could have an indirect

Groups all over the world have recognized the growing trend to wear effect. If athletes believe they are more protected because they are

helmets while skiing or snowboarding, and have studied the effect this wearing a helmet, they may travel at faster speeds or engage in riskier

has had on head injury. Although studies are limited, there does not maneuvers than they otherwise would without the helmet.

appear to be a strong correlation between helmet use and decreased Fortunately head injuries in snow sports are rare, but still a concern

head injury. In fact, one study has shown that in spite of increased for all skiers and snowboarders. When considering helmet use during

helmet use, the frequency of head injuries also increased over the snow sports, it is important to realize that helmets will not prevent all

same time period. head injuries. Practicing safe activities and wiser decision-making on

the mountain may be a better way to prevent head injury!

PRIMARY CARE SPORTS MEDICINE Shawn Phillips, M.D. Robert Gallo, M.D.

sphillips6@hmc.psu.edu rgallo@hmc.psu.edu

Matthew Silvis, M.D.

Assistant Professor, Departments of Family and Community Assistant Professor, Penn State Hershey Orthopaedics

msilvis@hmc.psu.edu

Medicine and Orthopaedics Penn State Hershey Bone and Joint Institute, 717-531-5638

Associate Professor, Departments of Family and Community

Penn State Hershey Medical Group—Mt. Joy, 717-653-2900

Medicine and Orthopaedics Scott Lynch, M.D.

Penn State Hershey Bone and Joint Institute, 717-531-5638

Medical Director, Primary Care Sports Medicine slynch@hmc.psu.edu

Penn State Hershey Medical Group—Palmyra, 717-838-6305 Rory Tucker, M.D. Associate Professor, Director of Sports Medicine Service

Penn State Hershey Bone and Joint Institute, 717-531-5638 jtucker@hmc.psu.edu Practice Site Clinical Director of Adult Bone and Joint Institute

Assistant Professor, Departments of Family and Community Medicine Associate Director of Orthopaedic Residency Education, 717-531-5638

Jessica Butts, M.D.

and Orthopaedics Penn State Hershey Bone and Joint Institute, 717-531-5638

Jbutts@hmc.psu.edu

Penn State Hershey Medical Group—Camp Hill, 717-691-1212

Assistant Professor, Departments of Family and Community Medicine

Penn State Hershey Bone and Joint Institute, 717-531-5638 SPORTS MEDICINE PHYSICAL THERAPY

and Orthopaedics

Penn State Hershey Medical Group—Nyes Road, 717-214-6545 Andrew Wren, D.O. Robert Kelly, PT, ATC

Penn State Hershey Bone and Joint Institute, 717-531-5638 awren@hmc.psu.edu Physical Therapist, Certified Athletic Trainer

Associate Professor, Department of Family and Community Medicine Team Physical Therapist, Hershey Bears Hockey Club

Bret Jacobs, D.O.

Medical Director, Penn State Hershey Medical Group—

bjacobs@hmc.psu.edu Scott Deihl, ATC, PTA

Elizabethtown, 717-361-0666

Assistant Professor, Departments of Family and Community Medicine Physical Therapist Assistant, Certified Athletic Trainer

and Orthopaedics

ORTHOPAEDIC SPORTS MEDICINE Tanya Deihl, ATC, PTA

Penn State Hershey Medical Group—Middletown, 717-948-5180

Physical Therapist Assistant, Certified Athletic Trainer,

Penn State Hershey Bone and Joint Institute, 717-531-5638 Kevin Black, M.D.

Athletic Trainer, Annville Cleona High School

kblack@hmc.psu.edu

Cayce Onks, D.O. Professor and C. McCollister Evarts Chair John Wawrzyniak, MS, ATC, PT, CSCS

conks@hmc.psu.edu Penn State Hershey Orthopaedics Physical Therapist, Certified Athletic Trainer

Assistant Professor, Departments of Family and Community Medicine Penn State Hershey Bone and Joint Institute, 717- 531-5638 Strength & Conditioning Specialist, Hershey Bears Hockey Club

and Orthopaedics

Penn State Hershey Medical Group—Palmyra, 717-838-6305 Aman Dhawan, M.D.

Penn State Hershey Bone and Joint Institute, 717-531-5638 adhawan@hmc.psu.edu

Assistant Professor, Department of Orthopaedics

Penn State Hershey Bone and Joint Institute, 717-531-5638

4

FCM-9228-16 022216You can also read