Risk factors for prospective increase in psychological stress during COVID-19 lockdown in a representative sample of adolescents and their parents

←

→

Page content transcription

If your browser does not render page correctly, please read the page content below

BJPsych Open (2021)

7, e94, 1–7. doi: 10.1192/bjo.2021.49

Risk factors for prospective increase in

psychological stress during COVID-19 lockdown

in a representative sample of adolescents and

their parents

Kerstin Paschke, Nicolas Arnaud, Maria Isabella Austermann and Rainer Thomasius

Background psychological stress. Risk factors for increased psychological

COVID-19 lockdown measures imposed extensive restrictions stress included sociodemographic (e.g. female parents, severe

to public life. Previous studies suggest significant negative financial worries) and emotion regulation aspects (e.g. non-

psychological consequences, but lack longitudinal data on acceptance of emotional responses in parents, limited access to

population-based samples. emotion regulation strategies in adolescents), explaining 31% of

the adolescent (Nagelkerke R2 = 0.31) and 29% of the parental

Aims (Nagelkerke R2 = 0.29) model variance.

We aimed to prospectively identify increased psychological

stress and associated risk factors in parent–child dyads. Conclusions

This study is the first to prospectively show an increase in psy-

Method chological stress during COVID-19 lockdown in a representative

We conducted a prospective, observational online study on family sample. Identified demographic and psychosocial risk

a representative German sample of 1221 adolescents aged factors lead to relevant implications for prevention measures

10–17 years and their parents. Psychological stress and psy- regarding this important public health issue.

chosocial variables were assessed before the pandemic (base-

line) and 1 month after the start of lockdown (follow-up), using Keywords

standardised measures. We used multilevel modelling to Psychological stress; COVID-19 lockdown; adolescents; parents;

estimate changes in psychological stress, and logistic regression risk factors.

to determine demographic and psychosocial risk factors for

increased psychological stress. Copyright and usage

© The Author(s), 2021. Published by Cambridge University Press

Results on behalf of the Royal College of Psychiatrists. This is an Open

The time of measurement explained 43% of the psychological Access article, distributed under the terms of the Creative

stress variance. Of 731 dyads with complete data, 252 adoles- Commons Attribution licence (http://creativecommons.org/

cents (34.5%, 95% CI 31.0–37.9) and 217 parents (29.7%, 95% CI licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted re-use, distribu-

26.4–33.0) reported a significant increase in psychological stress. tion, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work

Baseline levels were lower than in dyads without increased is properly cited.

The COVID-19 pandemic represents a major crisis that threatens Initial studies support the notion of the COVID-19 pandemic

physical and mental health. It places significant psychological being perceived as a stressful experience on a population level.8 One

burden on societies and individuals across the world.1 In the first cross-sectional study identified 38% of the Italian general population

weeks of the pandemic, many countries adopted public measures as having experienced significant distress during early lockdown.9

based on social distancing, to slow down the human-to-human Psychosocial conditions of children and their parents have long

spread of the novel virus. In mid-March 2020, the German played a subordinate role in the public debate during the COVID-

Government legislated the nationwide closure of schools, child care 19 pandemic.1,10 To the best of our knowledge, no studies are available

facilities, sports venues and public playgrounds, along with the impos- that have investigated psychological stress before and during the

ition of massive contact restrictions (termed ‘lockdown’).2 By that COVID-19 pandemic in representative family samples. Although

time, Europe was the epicentre of the pandemic. By mid-April, 977 stress increase in populations facing large-scale stressful events

569 cases and 84 607 COVID-19-associated deaths were reported in seems to be self-evident, such an approach is necessary to better

Europe. The most cases occurred in Spain (n = 172 541), Italy (n = understand the effects of an event unpredictable in duration.1,6,10

162 488) and Germany (n = 127 584). Among these countries, the Assessing the subjective appraisal of threatening or challenging

death rate was lowest in Germany at that time (2.56%, compared events in light of available coping resources (individually perceived

with 12.97% in Italy and 10.46% in Spain).3 Case fatality rates could stress), rather than life events per se (objective stress), could be

be shown to positively correlate with fear of the disease.4 Besides shown to be superior in terms of predicting health and health-

fear of death, severe lifestyle transformations, including decreased related outcomes.11 Global stress perception thus depends on context-

social contacts and upended daily structures, were associated with ual and personal factors, such as gender; age; educational, economical

higher depression and anxiety rates in adolescents.5 This is supported and occupational background;12 emotion regulation capabilities13 and

by studies from previous virus outbreaks that indicate containment parental self-efficacy.14

measures, such as quarantine, isolation and social distancing, can

have extensive negative consequences for mental health.6 Moreover,

the resulting high-density conditions (i.e. household crowding) are Aims

known to be particularly stressful and even traumatising to a signifi- To better identify those particularly vulnerable and thus in need of

cant proportion of children and parents.2,6,7 future targeted preventive action, this study aimed to assess

1

Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. 31 May 2021 at 19:35:29, subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use.Paschke et al

prospective levels and potential risk factors of psychological stress in Questionnaire (Fragebogen zur Selbstwirksamkeit in der Erzie-

adolescents and their parents, from the general population in hung).14 Adolescents’ and parents’ emotion regulation problems

Germany. We relied on standardised, longitudinal subjective were assessed by the short form of the Difficulties in Emotion Regu-

ratings of psychological stress before and during the COVID-19 lation Scale,16 a standardised 18-item tool organized into six sub-

pandemic, and expected that (a) a relevant proportion of adoles- scales (non-acceptance of emotional responses, lack of emotional

cents and/or parents will report an increase in psychological stress clarity, difficulties engaging in goal-directed behaviour under

during COVID-19 lockdown compared with pre-COVID-19 pan- unpleasant emotions, impulse control difficulties, limited access to

demic baseline measures; and (b) increases in psychological stress emotion regulation strategies and [lack of] emotional awareness).

can be predicted by a prespecified set of sociodemographic vari- Behavioural avoidance was measured with the four-item Procrastin-

ables, such as gender and financial worries, as well as potentially ation Questionnaire for Students (Prokrastinationsfragebogen für

modifiable family-related and stress coping-associated factors, Studierende).17 This questionnaire was initially validated in

such as emotional dysregulation and behavioural avoidance (i.e. German university students via online questionnaire. Because of

procrastination). the simple item structure with a five-point Likert-scale response

((almost) never to (almost) always) and its relation to study assign-

ments (e.g. ‘I put off starting tasks until the last moment’), it has

Method been frequently applied to high school students in clinical settings.

This is supported by an excellent internal consistency for the present

Participants and procedure adolescent sample (Cronbach’s α = 0.90). Moreover, during follow-

A representative sample of 1221 German adolescents aged between up, parents and adolescents were asked whether they mainly stayed

10 and 17 years, and 1221 respective parents, were included in this at home during COVID-19 lockdown.

observational study, using an online battery of questionnaires (N = The change in psychological stress from baseline to follow-up

2242). Of those, 824 parent–child dyads (67.5%) consented to join measurement was the primary outcome assessed by the Perceived

the follow-up measurement (n = 1648). Representativity was Stress Scale (PSS-4).11 This four-item instrument has been validated

assured in terms of proportions of gender, age and region of resi- in large international samples,12 including adolescents,18,19 and was

dence by using a random sampling method from the well-established applied at baseline and follow-up. Participants rated how frequently

German market research and opinion polling company forsa they have appraised their life as unpredictable, uncontrollable and

Gesellschaft für Sozialforschung und statistische Analysen mbH overloading within the previous month. Likert-scale responses

(for details see the study by Paschke et al,15 and Supplementary were summed up to a score of 0–16, with higher scores indicating

Methods and Supplementary Fig. 1 in Supplementary Appendix 1, higher general stress. A score of ≥ 8 could be referred to as

available at https://doi.org/10.1192/bjo.2021.49). The baseline data elevated.20

was collected as part of a large online survey on psychological

stress and media usage in families on a population basis, and supple-

Statistical analysis

mented by follow-up measurements at approximately half-year

intervals. The first interim results of an ongoing longitudinal study Absolute and relative frequencies were computed together with

are presented here. The observational period was set between 13 95% confidence intervals for categorial variables, and mean values

and 27 September 2019 for baseline, and between 20 and 30 April with s.d. for metric variables. Sociodemographic and psychological

2020 for the first follow-up assessment, 1 month after the start of characteristics of the baseline and the follow-up adolescent and par-

the German COVID-19 lockdown. ental sample were compared with χ2- and t-tests for categorial/

The authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work metric variables, to account for the sample attrition. Equivalence

comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national and testing was performed to compare mean baseline PSS-4 scores

institutional committees on human experimentation and with the with the literature by calculating two one-sided tests (TOST; for a

Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008. All procedures detailed description refer to the Supplementary Methods in

involving humans were approved by the Local Psychological Ethics Supplementary Appendix 1). To investigate the potential change

Committee of the University Medical Center Hamburg-Eppendorf of mean PSS-4 scores, paired-sample t-tests were computed. Effect

(ethical approval number LPEK-0145). Informed consent was sizes were calculated by Cohen’s d for repeated measures (drm).

obtained from all participants. Pearson correlation tests were used for PSS-4 values of parents

and adolescents at baseline and follow-up. Correlation values were

statistically evaluated using a z-test and Cohen’s q for effect size

Measures and outcome estimation.

We collected sociodemographic data on gender, age, place of resi- PSS-4 values of adolescents and corresponding parents were

dence, educational and first-generation migration background, estimated in a multilevel model, with the measurement time point

parental partnership status and the number of underaged children as an independent variable. Random effects were accounted for by

in the household at baseline. Occupation (‘Which of the following considering participants and their nesting within parent–child

descriptions of your occupation most closely applies to you?’ – dyads. To reveal the effect of between-group variance resulting

example answers: ‘not employed’, ‘job-seeking’ versus ‘part-time from measurements before and during the COVID-19 pandemic,

employed’, ‘fully employed’), school attendance (‘What are you cur- the intraclass correlation coefficient was calculated.

rently doing? Are you still in school, are you in training, are you Based on the individual’s change in psychological stress, the

employed or what else do you do?’) and financial worries (‘Which samples of adolescents and parents were each divided into two

of the following statements about your financial situation applies groups: group 1 showed an increase in psychological stress by >3

most to you?’ – ‘I often worry about paying my bills’, ’ I/my points (1 s.d.) and group 2 showed no increase in psychological

child often have to do without something because I have to limit stress. The sociodemographic characteristics and total scores of

myself financially’ versus ‘I have enough money for everything I the psychological measures for these groups were compared by

need’, ‘I have enough money to save something each month’) χ2- and t-tests (categorial/metric variables) and multivariate analysis

were measured by single items. Moreover, confidence in parenting of variance (psychometric variables), with separate post hoc Scheffé

was assessed with the validated nine-item Parental Self-efficacy tests for adolescents and parents. Effect sizes were computed with

2

Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. 31 May 2021 at 19:35:29, subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use.Psychological stress in families during COVID‐19

Cramer’s V (categorial variables) and Cohen’s d (metric variables) Table 1 Sociodemographic sample description

for independent measures.

Follow-up sample, n (%) or

Logistic regression analyses were used to determine risk factors Variables/categories mean (s.d.; range)

for increased psychological stress in adolescents and parents during

Adolescents 824

COVID-19 lockdown, controlling for potential age and baseline Gender

psychological stress effects. Respectively, the sociodemographic Male 442 (53.6)

and psychological baseline measures, time spent at home during Female 382 (46.4)

COVID-19 lockdown and an increase in psychological stress (yes/ Age, years 13.06 (2.4; 10–17)

no) of the corresponding parent/child were simultaneously (Prospective) school-leaving certificatea

No/low educational degreeb 30 (3.8)

entered into multivariate regression models, with age and PSS-4

Middle or higher educational degreec 762 (96.2)

baseline as covariates after dichotomising. Model reduction was High school studentd

performed by backwards elimination using the Akaike information Yes 763 (92.7)

criterion. Adjusted odds ratios were estimated based on the final Noe 60 (7.3)

model (for further details refer to the Supplementary Methods in Parents 824

Supplementary Appendix 1). Gender

All statistical analyses were performed with the software Male 405 (49.2)

Female 419 (50.9)

package R version 4.0.2 for Windows.21

Age, years 46.5 (8.0; 28–75)

Highest educational levelf

Low educationg 73 (8.9)

Results Middle or high educationh 750 (91.1)

Occupation

Sample characteristics Full-time or part-time employment 733 (89.0)

No employment 91 (11.0)

A comparison between the baseline and follow-up sample, regard- Relationship statusi

ing sociodemographic factors and psychometric responses to Single 63 (7.7)

account for potential attrition effects, did not reveal any significant Partnership 759 (92.3)

differences (Supplementary Table 1 in Supplementary Appendix 1). Parent–child dyad

Number of underaged children in 1.7 (0.83; 1–13)

Of the 824 dyads that participated in the baseline and the follow-up

householdj

measurements, 731 sufficiently completed the PSS-4 and could be Place of residence

included in the family-based analyses (Supplementary Fig. 1 in Urban living 440 (53.4)

Supplementary Appendix 1). Rural living 384 (46.6)

Table 1 shows the sample characteristics. The adolescent sample Financial worriesk

was 46.4% female. The adolescents’ mean age was 13.06 (s.d. 2.40). Yes 33 (4.1)

The adolescents showed mean PSS-4 values of 5.53 (s.d. 3.02) before No 782 (96.0)

First-generation migration backgroundl

the pandemic and 6.93 (s.d. 3.14) during COVID-19 lockdown. A

Yes 36 (4.4)

paired t-test revealed a clinically significant increase in psycho- No 787 (95.6)

logical stress in adolescents (t(823) = 11.44, P < 0.001, Cohen’s

a. No answer, n = 32.

drm = 0.41). The parental sample was 50.9% female. The parents’ b. No, special school (Förderschulabschluss) or lower school certificate

mean age was 46.5 (s.d. 8.0). The parents showed mean PSS-4 (Hauptschulabschluss).

c. Secondary school certificate (Realschulabschluss) to university entry qualification

values of 5.33 (s.d. 2.98) before the pandemic and 6.33 (s.d. 2.99) (Abitur).

d. No answer, n = 1.

during COVID-19 lockdown. Comparable with the adolescents, a e. In voluntary service, apprenticeship, national service or job-seeking.

paired t-test showed a clinically significant increase in psychological f. No answer, n = 1.

g. No or lower school certificate (Hauptschulabschluss).

stress in the parental sample (t(823) = 9.13, P < 0.001, Cohen’s h. Secondary school certificate (Realschulabschluss) to doctor’s degree (PhD).

drm = 0.32). i. No answer, n = 2.

j. No answer, n = 4.

The parental PSS-4 baseline value was equivalent to the average k. No answer, n = 9.

score of large samples of 37 451 European participants (mean differ- l. No answer, n = 1.

ence of 0.1, TOST 90% CI −0.08 to 0.28).14 The adolescent baseline

score was 1.2 points lower than the PSS-4 total score of a large sample

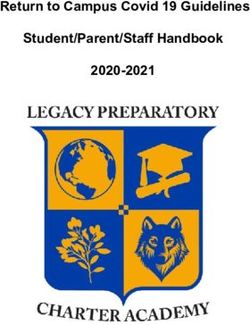

of 29 388 British adolescents (mean difference of 1.2, TOST 90% CI different trajectories of psychological stress development are visua-

1.01–1.39).15 A younger British sample showed an equivalent value lised in Fig. 1.

(mean difference of 0.1, TOST 90% CI −0.17 to 0.23).16 Please

refer to the Supplementary Results in Supplementary Appendix 1 Adolescents

for further details. A total of 252 adolescents (34.47%, 95% CI 31.03–37.92) reported

an increase in psychological stress from baseline to follow-up.

Psychological stress before and during the pandemic These adolescents showed significantly lower PSS-4 values before

the pandemic (4.36 v. 6.81, t(609.54) = −12.79, P < 0.001, d = 0.93)

PSS-4 values of adolescents and their respective parents showed

and significantly higher values during COVID-19 lockdown, com-

moderate correlations at baseline (r = 0.38, P < 0.001) and slightly

pared with adolescents who did not experience increased stress

higher (moderate) correlations at follow-up (r = 0.45, P < 0.001;

(9.15 v. 6.22, t(537.48) = 14.46, P < 0.001, d = 1.10), with large

comparison: z = 3.24, Cohen’s q = 0.17). A multilevel analysis of

effect sizes.

the PSS-4 values of all participants, taking into account the

parent–child dyads, revealed an intraclass correlation coefficient

value of 0.43 (Supplementary Table 2 in Supplementary Appendix Parents

1). This indicates that 43% of the PSS-4 variance is explained by A total of 217 parents (29.69%, 95% CI 26.37–33.00) experienced an

the time of the measurement (follow-up 1 month after start of increase in psychological stress during COVID-19 lockdown.

COVID-19 lockdown versus baseline 7 months earlier). The They showed significantly lower PSS-4 values before the pandemic

3

Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. 31 May 2021 at 19:35:29, subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use.Paschke et al

2.33, 95% CI 1.56–3.49), procrastination (adjusted odds ratio 2.10,

15

95% CI 1.27–3.48), limited access to emotion regulation strategies

(adjusted odds ratio 2.01, 95% CI 1.21–3.35) and mainly staying

at home during COVID-19 lockdown (adjusted odds ratio 1.65,

95% CI 1.08–2.50). High emotional awareness served as a protective

factor for adolescents, with an adjusted odds ratio of 0.47 (95% CI

0.29–0.77).

Psychological stress (PSS total score)

Parents

10 Ten out of nineteen predictors and the two covariates (baseline psy-

chological stress and age) stayed in the logistic regression model

after backwards elimination for the parents (Supplementary

Table 6 in Supplementary Appendix 1). The remaining variables

explained 29% of the final parental model variance (Nagelkerke

R2 = 0.29). Significant parental risk factors for increased psycho-

logical stress could be identified, including female gender (adjusted

odds ratio 1.86, 95% CI 1.29–2.76), partnership status (adjusted

5 odds ratio 2.78, 95% CI 1.10–6.98), urban living (adjusted odds

ratio 1.45, 95% CI 1.00–2.10), financial worries (adjusted odds ratio

1.86, 95% CI 1.08–3.19), increased psychological stress of the corre-

sponding adolescent (adjusted odds ratio 1.59, 95% CI 1.09–2.33),

procrastination (adjusted odds ratio 1.70, 95% CI 1.00–2.89) and

non-acceptance of emotional responses (adjusted odds ratio 3.02,

95% CI 1.78–5.13).

All adjusted odds ratios are visualised in Fig. 2.

0

pre-COVID-19 under lockdown Discussion

Time of measurement

To our knowledge, this is the first study to investigate psychological

Fig. 1 Multilevel analysis: trajectories of psychological stress stress within a representative sample of adolescents and their

before the COVID-19 pandemic and under lockdown measures. The parents during COVID-19 lockdown, compared with pre-

individual trajectories of all adolescents and parents are shown, COVID-19 conditions, in a longitudinal design. A total of 43% of

together with means and 95% confidence intervals of individuals the psychological stress variance in the parent–child dyads could

belonging to the increased psychological stress group and non- be explained by the time of measurement (September 2019 versus

increased psychological stress group, in reference to the two April 2020). We found that about a third of the adolescents and

measurement points. The size of the dots reflects the group size. parents showed a significant increase in psychological stress

Accordingly, smaller dots represent the increased psychological

during COVID-19 lockdown. Although increased psychological

stress group and larger dots represent the non-increased

stress seems to be a normal human reaction to the COVID-19 pan-

psychological stress group.

demic,6 this finding appears meaningful from a public health per-

spective because psychological stress is a major predisposing

factor for health problems, including (neuro-)psychiatric seque-

(3.74 v. 6.00, t(546.91) = −11.13, P < 0.001, d = 0.80) and signifi- lae.22,23 This is of particular importance in adolescents, given their

cantly higher values during COVID-19 lockdown (8.33 v. 5.51, increased vulnerability to stress and psychopathology in a period

t(427.98) = 13.41, P < 0.001, d = 1.06), compared with parents who of substantial neurobiological and psychological changes.24 The

did not experience increased stress, again with large effect sizes. finding builds on initial cross-sectional studies from Germany,25

A detailed comparison on sociodemographic and psychological Italy9 and China,26,27 showing that about a quarter of German, a

parameters, including results of the multivariate analyses of vari- third of Italian and up to half of Chinese adults reported feelings

ance and post hoc tests (psychometric variables) between groups of mental distress during the initial stage of the COVID-19

with and without increased psychological stress, can be found in pandemic.

Supplementary Appendix 1 (Supplementary Results and Supple- Interestingly, baseline psychological stress level could be identi-

mentary Tables 3 and 4). fied as a major factor that needs to be considered when investigating

potential stress increase. Adolescents and parents who experienced

a significant increase in psychological stress had lower baseline

Risk factors for increase in psychological stress

stress levels than those who did not experience increased psycho-

Adolescents logical stress during COVID-19 lockdown. This might suggest

Six out of fifteen predictors and the covariate baseline psychological that the latter group has better developed stress-coping mechanisms

stress (covariate age excluded) stayed in the logistic regression than those with lower baseline stress.28 On the other hand, albeit

model after backwards elimination for the adolescents hypothetical at the present stage of research, COVID-19 lockdown

(Supplementary Table 5 in Supplementary Appendix 1). The consequences, such as school closures and home office implementa-

remaining variables explained 31% of the final adolescent model tion, might actually be stress-reductive among a subsample of ado-

variance (Nagelkerke R2 = 0.31). Significant adolescent risk factors lescents and parents. Correspondingly, family cohesion and better

for increased psychological stress included financial worries family adjustment could be promoted, and school-related problems

(adjusted odds ratio 2.13, 95% CI 1.29–3.51), increased psycho- (like low academic achievement, experiencing social pressure or

logical stress of the corresponding parent (adjusted odds ratio being bullied) might decrease.29

4

Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. 31 May 2021 at 19:35:29, subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use.Psychological stress in families during COVID‐19

No stress increase Stress increase Adolescents Parents

Odds ratio [95% CI] P-value Odds ratio [95% CI] P-value

Urban living e e 1.45 [1–2.1] 0.05

Model

Low (prospective) education Adolescents e e 1.7 [0.86–3.33] 0.13

Parents

Female gender e e 1.89 [1.29–2.76] 0.001

Procrastinationa 2.10 [1.27–3.48] .004 1.7 [1–2.89] 0.05

Non-acceptance of emotional responsesb e e 3.02 [1.78–5.13]Paschke et al

stress, and parents with a low acceptance of emotional responses by COVID-19 and lockdown-induced economic changes. This

were three times as likely to experience increased psychological was not the primary aim of the study and is a complex issue, as

stress. Moreover, procrastination – an avoidance-based, short- research shows that youth stress responsiveness is a highly volatile

term emotion regulation strategy36 – could be identified as a risk construct, affected by numerous family-related, developmental and

factor for adolescent (adjusted odds ratio of 2.10) and parental other biopsychosocial aspects.41 Nevertheless, based on prior research,

increased psychological stress (adjusted odds ratio of 1.70). In con- we can assume that the COVID-19 pandemic was a significant source

trast, emotional awareness (the appraisal and recognition of one’s of stressors in the current sample, allowing for conclusions on a popu-

own feelings) could be identified as a potentially modifiable psycho- lation level.42 Finally, it should be kept in mind that the reported

logical protective factor against increased psychological stress in results are from an ongoing study. Thus, the added value of prospect-

adolescents (adjusted odds ratio of 0.47). Aside from external ive studies by means of multiple measurement points has not yet been

factors, cognitive appraisal processes determine whether and how fully exploited.

much a situation is perceived as stressful, triggering coping strat-

egies such as emotion regulation to reduce negative feelings.37

Considering intraindividual difficulties in emotion regulation can Clinical relevance and future research

help to understand interindividual differences in psychological This prospective observational study is the first to report on the

stress during COVID-19 lockdown measures, thereby providing increase in psychological stress in adolescents and their parents,

potential anchors for prevention approaches at individual and as well as associated demographic and psychosocial risk factors in

family levels. These might include elements of established programs a representative German family sample during COVID-19 lock-

such as mindfulness-based cognitive therapy, dialectical behavioural down, compared with pre-COVID-19 conditions. It thus adds

therapy or acceptance-based behavioural therapy.38 Moreover, activ- knowledge to the current evidence base on the psychological

ity-based interventions, such as yoga, sports, play and creative arts, impact of this worldwide pandemic. Our findings have several

have been shown to improve mental health, and might be promising implications for clinicians, researchers, policy makers and social

in providing helpful offers for adolescents to spend time outside the actors. As the COVID-19 pandemic continues, psychological

home without violating restriction rules.39 Online interventions stress and its corresponding threat to mental health should be of

might be a useful new method to support mental health,20 especially greater consideration among public health authorities. Besides pro-

during a time where personal contacts are limited. tecting the population from the disease, adolescents and their

parents – especially mothers – could benefit from targeted psycho-

logical stress prevention measures. The identification of sociodemo-

Strengths and limitations graphic, family-associated and potentially modifiable psychological

The study has numerous strengths, including the use of prospective risk factors, such as capacity for adaptive coping, provides decision

data with an assessment just before the pandemic and during makers with meaningful insights for public health action.

COVID-19 lockdown; a large study population representative Future studies should focus on the detailed investigation of

regarding gender (most of the studies available have included a sig- factors explaining individual increased psychological stress and

nificant higher proportion of female respondents), age and region of resiliency. Although the present study could not identify adoles-

living; the data of parent–child dyads; information on potential risk cents’ age as a significant covariate regarding psychological stress,

factors before the COVID-19 pandemic and the variety of standar- future research should investigate age aspects in more detail by

dised subjective ratings to collect data on psychological stress and including younger children and their parents. Moreover, cross-cul-

potential psychological risk factors. However, several limitations tural studies should enhance knowledge on the comparability of the

of this study need to be considered. presented findings. Psychological stress variability during the course

First, although sample representativity was warranted in terms of of the pandemic should be investigated by follow-up measurements.

age, gender and place of residence, representativity in other respects

might have been reduced because of the data collection procedure. In

Kerstin Paschke , MD, German Center for Addiction Research in Childhood and

this respect, the sample only includes households with sufficient Adolescence, University Medical Center Hamburg-Eppendorf, Germany;

knowledge of the German language, so families with an immigrant Nicolas Arnaud, PhD, German Center for Addiction Research in Childhood and

Adolescence, University Medical Center Hamburg-Eppendorf, Germany; Maria

background might not have been properly taken into account. In add- Isabella Austermann, MSc, German Center for Addiction Research in Childhood and

ition, around 5% of German households do not have internet access40 Adolescence, University Medical Center Hamburg-Eppendorf, Germany;

and could not be included in this study. Moreover, although online Rainer Thomasius, MD, German Center for Addiction Research in Childhood and

Adolescence, University Medical Center Hamburg-Eppendorf, Germany

questionnaires are highly valued for cost-effectiveness in large epi-

Correspondence: Kerstin Paschke. Email: k.paschke@uke.de

demiological studies, missing data is a common problem, especially

when investigating dyads and children. Accordingly, 113 parent– First received 20 Sep 2020, final revision 12 Feb 2021, accepted 1 Apr 2021

child dyads had to be omitted from subsequent analysis, which

might have decreased representativity. In addition, all participants

were asked to complete the questionnaire independently, but the

influence of others cannot be excluded. Supplementary material

Second, although our study revealed a significant increase in

Supplementary material is available online at https://doi.org/10.1192/bjo.2021.49.

psychological stress in families on a population level, and identified

risk factors during the first German COVID-19 lockdown, it could

not explain the individual circumstances that may have preceded Data availability

these increases. In fact, we cannot rule out the possibility that The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author,

other factors or unknown third variables during the survey interval K.P., upon reasonable request, after all results of the parent–child survey have been published.

contributed to the variance in the prospective psychological stress

change. Moreover, we cannot conclude on the individual factors Acknowledgements

that actually led to the observed increases in psychological stress,

We thank Dr Peter-Michael Sack for his support on preparing the manuscript, Dr Torsten

because of the restricted number of items in an online survey, Wüstenberg for valuable discussions on the initial data analysis strategies, and Milan

such as the number of critical life events, family members affected Röhricht for his language-editing support.

6

Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. 31 May 2021 at 19:35:29, subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use.Psychological stress in families during COVID‐19

18 Cartwright M, Wardle J, Steggles N, Simon AE, Croker H, Jarvis MJ. Stress and

Author contributions dietary practices in adolescents. Health Psychol 2003; 22(4): 362–9.

K.P. and R.T. conceptualised and designed the study, and decided to publish the paper. K.P. 19 Demkowicz O, Panayiotou M, Ashworth E, Humphrey N, Deighton J. The factor

performed the statistical analysis. All authors interpreted the data. K.P. drafted the manuscript, structure of the 4-item Perceived Stress Scale in English adolescents. Eur J

with support of N.A.. M.I.A. edited tables and figures and performed the final formatting. All Psychol Assess 2019; 36: 913–17.

authors critically revised the draft for important intellectual content. All authors agreed to be

accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or 20 Harrer M, Adam SH, Baumeister H, Cuijpers P, Karyotaki E, Auerbach RP, et al.

integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. All authors Internet interventions for mental health in university students: a systematic

gave final approval for the article to be published. review and meta-analysis. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res 2019; 28(2): e1759.

21 R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing.

Funding R Foundation for Statistical Computing, 2019 (https://www.R-project.org/).

22 Davis MT, Holmes SE, Pietrzak RH, Esterlis I. Neurobiology of chronic stress-

The current study is part of a parent–child survey that was financially supported by the German

health insurance company DAK Gesundheit. The funding was awarded to the German Center related psychiatric disorders: evidence from molecular imaging studies.

for Addiction Research in Childhood and Adolescence (K.P. and R.T.). The supporters had no Chronic Stress 2017; 1: 2470547017710916.

role in the creation of the study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation or 23 Troyer EA, Kohn JN, Hong S. Are we facing a crashing wave of neuropsychiatric

writing of the manuscript.

sequelae of COVID-19? Neuropsychiatric symptoms and potential immunologic

mechanisms. Brain Behav Immun 2020; 87: 34–9.

Declaration of interest 24 Grant KE, Compas BE, Thurm AE, McMahon SD, Gipson PY, Campbell AJ, et al.

None. Stressors and child and adolescent psychopathology: evidence of moderating

and mediating effects. Clin Psychol Rev 2006; 26(3): 257–83.

25 Liu S, Heinz A. Cross-cultural validity of psychological distress measurement

References during the coronavirus pandemic. Pharmacopsychiatry 2020; 53(5): 237–8.

26 Wang C, Pan R, Wan X, Tan Y, Xu L, Ho CS, et al. Immediate psychological

responses and associated factors during the initial stage of the 2019 corona-

1 Holmes EA, O’Connor RC, Perry VH, Tracey I, Wessely S, Arseneault L, et al. virus disease (COVID-19) epidemic among the general population in China. Int

Multidisciplinary research priorities for the COVID-19 pandemic: a call for action J Environ Res Public Health 2020; 17(5): 1729.

for mental health science. Lancet Psychiatry 2020; 7(6): 547–60. 27 Qiu J, Shen B, Zhao M, Wang Z, Xie B, Xu Y. A nationwide survey of psychological

2 Röhr S, Müller F, Jung F, Apfelbacher C, Seidler A, Riedel-Heller SG. distress among Chinese people in the COVID-19 epidemic: implications and

Psychosoziale folgen von quarantänemaßnahmen bei schwerwiegenden cor- policy recommendations. Gen Psychiatr 2020; 33(2): e100213.

onavirus-ausbrüchen: ein rapid review. [Psychosocial impact of quarantine 28 Glanz K, Rimer BK, Viswanath K. Health Behavior and Health Education: Theory,

measures during serious coronavirus outbreaks: a rapid review]. Psychiatr Research, and Practice. John Wiley & Sons, 2008.

Prax 2020; 47(4): 179–89.

29 Guessoum SB, Lachal J, Radjack R, Carretie E, Minassian S, Benoit L, et al.

3. World Health Organization (WHO). Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) Adolescent psychiatric disorders during the COVID-19 pandemic and lock-

Situation Report – 86. WHO, 2020 (https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/ down. Psychiatry Res 2020; 291: 113264.

coronaviruse/situation-reports/20200415-sitrep-86-covid-19.pdf?sfvrsn=c615ea20_6).

30 Wang C, Pan R, Wan X, Tan Y, Xu L, McIntyre RS, et al. A longitudinal study on the

4 Fulawka K, Lenda D, Traczyk J. Associations between case fatality rates and mental health of general population during the COVID-19 epidemic in China.

self-reported fear of neoplasms and circulatory diseases. Med Decis Making Brain Behav Immun 2020; 87: 40–8.

2019; 39(7): 727–37.

31 Connor J, Madhavan S, Mokashi M, Amanuel H, Johnson NR, Pace LE, et al.

5 Chen F, Zheng D, Liu J, Gong Y, Guan Z, Lou D. Depression and anxiety among Health risks and outcomes that disproportionately affect women during the

adolescents during COVID-19: a cross-sectional study. Brain Behav Immun COVID-19 pandemic: a review. Soc Sci Med 2020; 266: 113364.

2020; 88: 36–8.

32 Lecic-Tosevski D. Is urban living good for mental health? Curr Opin Psychiatry

6 Brooks SK, Webster RK, Smith LE, Woodland L, Wessely S, Greenberg N, et al. 2019; 32(3): 204–9.

The psychological impact of quarantine and how to reduce it: rapid review of

33 Huang Y, Zhao N. Chinese mental health burden during the COVID-19 pan-

the evidence. Lancet 2020; 395(10227): 912–20.

demic. Asian J Psychiatr 2020; 51: 102052.

7 Solari CD, Mare RD. Housing crowding effects on children’s wellbeing. Soc Sci

34 McCormick R. Does access to green space impact the mental well-being of chil-

Res 2012; 41(2): 464–76.

dren: a systematic review. J Pediatr Nurs 2017; 37: 3–7.

8 Sprang G, Silman M. Posttraumatic stress disorder in parents and youth after

health-related disasters. Disaster Med Public Health Prep 2013; 7(1): 105–10. 35 Evans GW, English K. The environment of poverty: multiple stressor exposure,

psychophysiological stress, and socioemotional adjustment. Child Dev 2002; 3

9 Moccia L, Janiri D, Pepe M, Dattoli L, Molinaro M, De Martin V, et al. Affective (4): 1238–48.

temperament, attachment style, and the psychological impact of the COVID-

19 outbreak: an early report on the Italian general population. Brain Behav 36 Zhang S, Liu P, Feng T. To do it now or later: the cognitive mechanisms and

Immun 2020; 87: 75–9. neural substrates underlying procrastination. Wiley Interdiscip Rev Cogn Sci

2019; 10(4): e1492.

10 Onyeaka HK, Zahid S, Patel RS. The unaddressed behavioral health aspect

37 Myruski S, Denefrio S, Dennis-Tiwary TA. Stress and emotion regulation. In The

during the coronavirus pandemic. Cureus 2020; 12(3): e7351.

Oxford Handbook of Stress and Mental Health: 415. Oxford University Press,

11 Cohen S, Kamarck T, Mermelstein R. A global measure of perceived stress. 2019.

J Health Soc Behav 1983; 24(4): 385–96.

38 Moltrecht B, Deighton J, Patalay P, Edbrooke-Childs J. Effectiveness of current

12 Vallejo MA, Vallejo-Slocker L, Fernández-Abascal EG, Mañanes G. Determining psychological interventions to improve emotion regulation in youth: a meta-

factors for stress perception assessed with the Perceived Stress Scale (PSS-4) analysis. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry [Epub ahead of print] 27 Feb 2020.

in Spanish and other European samples. Front Psychol 2018; 9: 37. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-020-01498-4.

13 Wang M, Saudino KJ. Emotion regulation and stress. J Adult Dev 2011; 18: 39 Cahill SM, Egan BE, Seber J. Activity- and occupation-based interventions to

95–103. support mental health, positive behavior, and social participation for children

14 Kliem S, Kessemeier Y, Heinrichs N, Döpfner M, Hahlweg K. Der Fragebogen zur and youth: a systematic review. Am J Occup Ther 2020; 74(2): 7402180020.

Selbstwirksamkeit in der Erziehung (FSW). [The Parenting Self-efficacy 40. statista. Share of households in Germany with internet access by 2020. statista,

Questionnaire (FSW).] Diagnostica 2014; 60: 35–45. 2021 (https://de.statista.com/statistik/daten/studie/153257/umfrage/haush-

15 Paschke K, Austermann MI, Thomasius R. Assessing ICD-11 gaming disorder in alte-mit-internetzugang-in-deutschland-seit-2002/).

adolescent gamers by parental ratings: development and validation of the 41 Lippold MA, Davis KD, McHale SM, Buxton OM, Almeida DM. Daily stressor

Gaming Disorder Scale for Parents (GADIS-P). J Behav Addict [Epub ahead of reactivity during adolescence: the buffering role of parental warmth. Health

print] 7 Jan 2021. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1556/2006.2020.00105. Psychol 2016; 35(9): 1027–35.

16 Kaufman EA, Xia M, Fosco G, Yaptangco M, Skidmore CR, Crowell SE. The 42 Veer IM, Riepenhausen A, Zerban M, Wackerhagen C, Puhlmann LMC, Engen H,

Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale Short Form (DERS-SF): validation and et al. Psycho-social factors associated with mental resilience in the corona

replication in adolescent and adult samples. J Psychopathol Behav Assess lockdown. Transl Psychiatry 2021; 11: 67.

2016; 38: 443–55.

17. Glöckner-Rist A, Engberding M, Höcker A, Rist F. Prokrastinationsfragebogen

für Studierende (PfS). [Procrastination Scale for Students.] In: Zusammenstel-

lung sozialwissenschaftlicher Items und Skalen. [Summary of Items and Scales

in Social Science.] GESIS, 2009 (https://doi.org/10.6102/ZIS140).

7

Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. 31 May 2021 at 19:35:29, subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use.You can also read