PRINCIPAL - ABORIGINAL EDUCATION - Canadian Association of ...

←

→

Page content transcription

If your browser does not render page correctly, please read the page content below

PRINCIPAL

C AT H O L I C

ONTARIO

PRINCIPALS’

Winter 2015 • Volume 19 • Issue 2

CONNECTIONS

COUNCIL

ABORIGINAL EDUCATION"And the angel said unto them, Fear not:

behold, I bring you good tidings of great

joy, which shall be to all people."

Luke 2:10

May the Lord bless you this Christmas and always.

Catholic Principals’ Council | Ontario

The CPCO office will be closed for the If immediate legal advice is required,

Christmas holidays, commencing Monday, contact Protective Services Coordinator

December 21, 2015, and will reopen Joe Geiser at 1.888.621.9190 ext. 34 or

on Monday, January 4, 2016. email at jgeiser@cpco.on.ca.

Voice and email messages received If assistance is required for CPCO’s

over the holidays will be returned on Long Term Disability Program, contact

January 4, 2016. Johnson Inc. at 1.877.709.5855.

SHARE YOUR STORY WITH SHARE YOUR STORY WITH

PRINCIPAL

CONNECTIONS CPCO BLOG

We are always looking for interesting articles. Submissions We want to know what’s happening in your school community.

should be 800-1000 words. Images should be 300 dpi Send stories about new initiatives, events and any other

minimum and in jpg, tif, or png formats. Please do not special happenings.

reduce the size of digital images.

Submissions should be 300-800 words. Images should be in

Send the articles in Word format only to Editor, jpg or png formats.

Deirdre Kinsella Biss at dkinsellabiss@ cpco.on.ca

Send your stories in Word format only to Communications Officer,

Upcoming themes and deadlines: Andie McHardy-Blaser at amchardy-blaser@ cpco.on.ca

SUMMER 2016 - Transformative Education

Articles due by April 8, 2016 blog.cpco.on.ca

CPCO reserves the right to edit all materials. Please understand that CPCO reserves the right to edit all materials. Please understand that

a submission does not automatically guarantee publication. a submission does not automatically guarantee publication.Winter 2015 • Volume 19 • Issue 2

C AT H O L I C

ONTARIO

IN THIS ISSUE PRINCIPALS’

COUNCIL

EDITORIAL, ADVERTISING & SALES

IN THE SPOTLIGHT

Deirdre Kinsella Biss, Editor

Exploring Math through Indigenous Culture | 4 dkinsellabiss@ cpco.on.ca

Fostering Indigenous Inclusive Schools | 8 Ania Czupajlo, Senior Designer/Principal Connections Art Director

aczupajlo@ cpco.on.ca | ext. 25

Sharing Cultures - Shaping Futures | 10

John Nijmeh, Advertising Manager

The Metaphor of the Circle | 13 events@ cpco.on.ca | ext. 28

10 Steps to Start the Conversation | 16 Gaby Aloi, Manager of Corporate Operations

Indigenous Education | 18 galoi@ cpco.on.ca | ext. 26

Native Spirituality and Catholic Praxis | 22

3 Good Ideas | 24 Sharing Cultures - Shaping Futures 10 CORPORATE, PROGRAMS & SERVICES

Recognizing Student Voice | 43 Wayne Hill, President

Reflections by Richard Wagamese | 46 president@ cpco.on.ca | ext. 22

Paul Lacalamita, Executive Director

placalamita@ cpco.on.ca | ext. 23

Hannah Yakobi, Marketing & Communications Manager

hyakobi@ cpco.on.ca | ext. 38

KEEPING YOU INFORMED

Andie McHardy-Blaser, Communications Officer

amchardy-blaser@ cpco.on.ca | ext. 30

Creating Conditions for Success | 20 Luciana Cardarelli, Program & Member Services Coordinator

The Need for Reconciliation | 27 lcardarelli@ cpco.on.ca | ext. 37

Creating Space for Elder Knowledge Vanessa Kellow, Professional Learning Assistant

in our Catholic Schools | 28 vkellow@ cpco.on.ca | ext. 31

The First Nations, Métis and Inuit Joe Geiser, Protective Services Coordinator

3 Good Ideas 24 jgeiser@ cpco.on.ca | ext. 34

Collaborative Inquiry Initiative | 32

Ron McNamara, Protective Services Assistant Coordinator

Storytelling, Art & Indigenous Knowledge | 34 rmcnamara@ cpco.on.ca | ext. 27

Crossing the Borders of Catholicity, Maria Cortez, Administrative Assistant

FNMI Teachings and Technology | 36 mcortez@ cpco.on.ca | ext. 32

Leadership that Supports Indigenous Bessy Valerio, Receptionist

Ways of Knowing and Learning | 38 bvalerio@ cpco.on.ca | ext. 21

The Art of the Medicine Wheel | 40

Using the Medicine Wheel | 44 We thank all those who contributed to this issue.

Pow Wow | 48 Please note, however, that the opinions and views

expressed are those of the individual contributors and are

not necessarily those of CPCO. Similarly, the acceptance

of advertising does not imply CPCO endorsement.

The Art of the Medicine Wheel 40 Publications Mail Agreement No. 40035635

IN EVERY ISSUE

No part of this publication may be reproduced in whole or

in part without written permission of CPCO.

Education is for Everyone! | 2

A Time for Inclusion | 3 Copyright ©2015 Catholic Principals' Council | Ontario.

All rights reserved.

10% Total Recycled Fiber

CONTACT US

Catholic Principals’ Council | Ontario

Aboriginal Education Box 2325, Suite 3030, 2300 Yonge Street

Toronto, Ontario M4P 1E4

Cover design by Ania Czupajlo

1.888.621.9190 toll free • 416.483.1556 phone

416.483.2554 fax • info@ cpco.on.ca

As principals and vice-principals, we embrace the diversity www.cpco.on.ca

and uniqueness that exist in our schools. Our Catholic schools

should be a place of welcome, a place of respect and caring, and We would like to acknowledge that the CPCO

a place of acceptance and friendship. office is on the traditional territory of the

Mississaugas of the New Credit First Nation.

Our call is to ensure that the needs of all our learners, including

@CPCOtweet

Aboriginal students, are being met through the education we #leadCPCO

linkd.in/1vBkhw3

deliver and the inclusive environment we create.

blog.cpco.on.ca youtube.com/CPCOtorontoFROM THE PRESIDENT

Wayne Hill

Education is for Everyone!

As educators and

A while back I read a column in the Catholic school traditions and beliefs of Canada’s

Globe and Mail written by Naheed

Nenshi, the Mayor of Calgary. In

leaders, we now have First Peoples. We have asked school

leaders to share their own success

expressing his concern for the potential the opportunity stories in their schools.

of bias and racism to isolate segments of

our society he writes, and responsibility We cannot pretend that we are getting

At our best we’ve figured out a simple

to build on our everything right. After all, this is a

journey and there is much work to be

truth: we’re in this together. Our common strengths, done. But we are in this together. We

neighbour’s strength is our strength. can learn from each other and build on

The success of any one of us is the to create changes each other’s strengths. Together, we

success of every one of us. More

importantly, any one failure is all

that make our can ensure that education is inclusive

for everyone and that no child or young

our failure, too. schools welcoming person feels left out. I thank you for

your work, your dedication and your

This quote clearly connects to Aboriginal and inclusive to all commitment to each and every one of

Education in Ontario. Even though we your students.

have shone the light on our Aboriginal our students.

students and identified issues and I want to take this opportunity to

concerns, we have much yet to do to thank all of our practising Associates

nurture student success and well-being. for their steadfast resolve and support of our students and

school communities over the course of the labour disruption.

As school leaders, we must address the achievement gap

with our Aboriginal students. We must ensure equal access I know how difficult a task it has been, how many long hours

to education, improved literacy and numeracy skills, in- you have put in, and the demands that this has placed on you

creased graduation rates and problem-solve drop out rates. and your families. What was evident throughout was your

We must find ways of engaging these students in post-sec- commitment to your school community and to Catholic

ondary studies. education. We all knew that this would end, and on that day

we needed to emerge with our relationships intact and our

As educators and Catholic school leaders, we now have the communities whole. You have seen to that and your efforts are

opportunity and responsibility to build on our common to be applauded!

strengths, to create changes that make our schools welcoming

and inclusive to all our students. May the hope, the peace, the joy, and the love represented by

the birth in Bethlehem fill our lives and become part of all that

This issue of Principal Connections focuses on various we say and do this Christmas and throughout the school year.

aspects of Aboriginal Education. We have invited Elders

and FNMI community leaders and educators to share their May God continue to bless you in your work.

stories, teachings and wisdom. We have examined many

of the commonalities between our Catholic faith and the

2 Principal Connections • Winter 2015 • Volume 19 • Issue 2FROM THE EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR

Paul Lacalamita

A Time for Inclusion

I trust this issue

The reasons why I believe in CPCO are will provide new learn to respect and grow familiar with

many. But none are more important

than the fact that as a professional as-

learning and the heritage and traditions of Canada’s

Aboriginal peoples.

sociation CPCO serves as a unifying

voice for the principals and vice-princi-

inspiration as you As you read this, labour relations

pals who work to bring exemplary lead- work to ensure that continue to be a priority for CPCO

ership to Catholic school communities staff as we prepare for principal/vice-

across our province. the needs of our principal negotiations with trustees

and the government.

The type of leadership our Associates First Nations, Métis

are called to practise – and indeed

what CPCO teaches in our Principal

and Inuit students CPCO has met several times with OPC

and ADFO to prepare for upcoming

Qualifications Program – is that of

servant leadership. Our leadership is

are met in your provincial government and Trustee

meetings regarding Principal/Vice-

steeped in the model of Jesus. Through schools ... principal terms and conditions of

Jesus we learn about truth, leadership employment. We anticipate beginning

and the importance of community. this process in earnest in January 2016.

In the meantime, our Protective Services staff continue to work

This issue of Principal Connections is themed around diligently on your behalf by preparing and engaging members’

Aboriginal Education. It explores our role, as Catholic school lead negotiators through regional meetings. Interest-based

leaders, who are called to embrace inclusiveness and create bargaining , review of contracts and data collection are but a

successful schools that are welcoming to all. few topics that will be covered at these meetings.

Many of the articles reflect the 4Rs of Indigenous pedagogy: Recently CPCO launched an online mental wellness re-

Respect, Reciprocity, Relevance and Responsibility. I’m sure source, available to Associates. Starling Minds provides

you will find that there are strong parallels between these education and training to help manage stress and over-

4Rs and our Catholic faith values, especially when viewed come anxiety and depression. This service came about as

through the type of trust and relationship building that is key the result of feedback from Associates, who have indicat-

to successful servant leadership. ed the need for support in managing their mental health,

increasing their coping skills and helping them become

The benefits of incorporating Indigenous ways of knowing and more resilient to stress. This online resource is available

learning in our schools are too obvious to ignore. The cross- to Associates at www.cpco.on.ca/starlingminds. Should

overs with leadership in particular seem very relevant as we you wish to learn more about Starling Minds itself you may

come to appreciate that it is not only ideas and vision that are do so at starlingminds.com.

prerequisites of great leaders but also beliefs and convictions.

As the blessed season of Christmas approaches I want to thank

I trust this issue will provide new learning and inspiration as you you all for being a gift to your school communities and for your

work to ensure that the needs of our First Nations, Métis and commitment to Catholic education. May this holy season of

Inuit students are met in your schools, and that all our students Advent root us all in faith, hope and love.

Principal Connections • Winter 2015 • Volume 19 • Issue 2 3Dr. Ruth Beatty, Lakehead University

Exploring Math through Indigenous Culture

C

hristina enters the Grade 3 classroom and sits on a low stool and appreciation of Indigenous perspectives and values. This project was

in front of a group of cross-legged students. She opens up a developed to explore how to co-design and co-teach units of instruction

small box and, smiling at the children, hands out some bead that are culturally responsive and conform to the National Council of

bracelets for them to look at. “So, loomwork is done with Teachers of Mathematics (NCTM) Standards and practices.

glass and sometimes plastic beads. A very long time ago this kind of work

was done with the sinew from animals – that’s the muscles from animals’ Research has shown that creating connections between math instruction

legs – you dry it up and it would make thread. And then beads were made and Indigenous culture has had beneficial effects on students’ abilities

from shells, and porcupine quills and all kind of things that you’d find in to learn mathematics (Cajete, 1994; Lipka, 1994). Long-term studies

nature. And then after that, when people started trading for glass beads, by Lipka (2002, 2007), Brenner (1998) and Doherty et al. (2002) found

we started using glass beads, and then plastic beads.” Christina then shows that culturally responsive education in mathematics had statistically

the students a loom with some beadwork on it. significant results in terms of student achievement. Reform-based

mathematical instructional practices are aligned with many aspects

This is the beginning of a Grade 3 mathematics unit, focusing on of Indigenous teaching in that both emphasize experiential learning,

multiplicative thinking, and algebraic and proportional reasoning. modelling, collaborative activity and teaching for meaning over rote

Christina is a member of the Algonquins of Pikwakanagan First Nation memorization and algorithm efficiency.

and is the Operations Manager of their cultural centre. She is also an

expert loomer. She and the classroom teacher Anne are part of a larger One of the most important components of this project has been

research project investigating the connections between Indigenous placing Indigenous cultural practices at the heart of an inquiry-based

cultural practices and the Western mathematics found in the Ontario approach to teaching mathematics. Four research teams, made up

mathematics curriculum. of Indigenous educators and artists and non-Native educators, have

explored the powerful mathematical thinking that emerges when

Ministries of Education across Canada have recognized the need to First Nations community members are invited to co-create and co-

explicitly incorporate Indigenous content to support identity building deliver units of instruction.

4 Principal Connections • Winter 2015 • Volume 19 • Issue 2In Renfrew County, Christina and her

team worked with Grade 1 students to

create bead bracelets, with an emphasis on

proportional reasoning and spatial sense. In Grade 6,

students have designed round beaded medallions and, in the

process, discovered mathematical concepts such as fractions,

algebraic relationships, and pi. In Kenora, Kindergarten

students worked with members of the Wauzhushk Onigum

First Nation to explore the mathematics of dreamcatchers,

while Grade 4 students delved into the complicated spatial

reasoning of the peyote stitch. In Barrie and Orillia, teachers

with Simcoe County worked with an expert loomer to explore

patterning, fractions and spatial transformations. And in Moose

Factory, we have begun work with Cree educators and teachers to

think about the mathematics of creating fishing nets.

One of the most positive outcomes cited by participants has been

further developing the relationships between school and First Nations

communities. Prior to starting any of the research the teams met with

community leaders who shared their insights and guidance. As the work

progressed, regular meetings were held with members of the community

to share updates through short videos and/or newsletters. Each research

team has worked to strengthen these connections and facilitate ongoing

communication so that First Nations perspectives are incorporated in a

cohesive and authentic way.

The research teams have been extremely enthusiastic about the robust

mathematical understanding that has emerged from the work (e.g.,

Beatty & Blair, 2015a; 2015b). As Tamara Whiteduck, another member The students were then given this Grade 3 EQAO question that asks

of the Algonquins of Pikwakanagan First Nation and part of the Renfrew students to predict what the eighth shape in a repeating sequence of five

County team put it, “These projects just seem to be overf lowing with shapes will be.

math opportunities!”

The teams have also been amazed at the connections to the curriculum

documents. For instance, Grade 3 teacher Anne realized that looming

could potentially be the basis for all of her mathematics teaching. “I kept

coming across big ideas in every strand of the math curriculum that

connected with the beading,” she explains.

The understanding students constructed while engaged in these First

Nations activities also carried over to more artificial “school math”

questions. For example, students in Anne’s class explored the structure of

the five-column core of a pattern and were able to predict what any column

would look like further down the sequence – that any column ending in a “5”

would be identical to the fifth column, any column that was a multiple of “5”

subtract “1” would look like the fourth column.

Principal Connections • Winter 2015 • Volume 19 • Issue 2 5This item can be answered by simply extending the pattern and counting This project demonstrates the importance, and powerful potential, of

to the eighth shape. However, the students who had previously had many using Indigenous content as a way of delivering mathematics instruction.

conversations about the mathematics of looming realized they were Valuing the cultural perspectives from the local First Nations

analyzing the same kind of structure as their beading patterns and were community, and involving community members in the design, delivery

able to use algebraic reasoning to predict the correct shapes anywhere in and assessment of mathematics lessons has resulted in meaningful and

the sequence. They reasoned that any multiple of “5” subtract “1” would be engaging learning experiences. As much as this research has been about

a circle, or that the 108th shape would be a square because the 110th shape math, it has also been about a process of reconciliation, and valuing a

(a multiple of 5) would be a triangle, then subtract (go back) two shapes. distinct worldview and knowledge system that has historically been

excluded from the classroom.

The teachers speculate that, in part, this powerful thinking is due to the

fact that students are able to explore mathematics as they create beautiful

works that have cultural and emotional significance. Students can learn This project was conducted in partnership with Danielle Blair, Provincial

Mathematics Lead, on assignment with the Ontario Ministry of Education.

complex math concepts not by having these superimposed on an activity,

Funding was provided through a SSHRC Insight Development Grant, and

but rather as they arise from the activity naturally. through the Ontario Ministry of Education.

References

For First Nations students, this project has provided an opportunity

Beatty, R., & Blair, D. (2015a). Indigenous pedagogy for early mathematics:

to heighten their sense of pride. As one community member states Algonquin looming in a grade 2 math classroom. The International Journal of

“Sometimes our kids face social barriers. But this puts their culture at Holistic Early Learning and Development, 1, 3-24. (refereed)

the centre. At first, the non-Native kids are curious, and then they’re

Beatty, R. & Blair, D. (2015b). Connecting Indigenous and western ways of

interacting with art and math in a hands-on and fun way. It gives the

knowing: Algonquin looming in a grade 6 math class. Proceedings of the 37th Annual

Native kids an opportunity to show their identity.” It has also been Meeting of the Psychology of Mathematics Education, North American Chapter.

important for all students to learn from community members teaching

in the classroom, and see that the knowledge brought by these members Brenner, M.E. (1998). Adding cognition to the formula for culturally relevant

instruction in mathematics. Anthropology and Education Quarterly, 29(2), 214-244.

is honoured and respected.

Cajete, G., (1994). Look to the mountain: An ecology of indigenous education.

Placing Indigenous culture at the heart of mathematics instruction, and Durango, CO: Kivaki Press.

learning through that cultural perspective, has led to our re-thinking what

Doherty, W.R., Hilbert, S., Epaloose, G., & Tharp, R.G., (2002). Standards

it means to teach and learn mathematics. Mike, a Grade 6/7 teacher from

performance continuum: Development and validation of a measure of effective

the Renfrew County DSB laments, “I feel like as kids we were robbed in pedagogy. The Journal of Educational Research 96(2), 78-89.

terms of how we were taught math! Incorporating traditional ways of

knowing, and working with Christina and the team has totally changed my Lipka, J., Sharp, N., Adams, B., & Sharp, F., (2007). Creating a third space for

authentic biculturalism: Examples from math in a cultural context. Journal of

viewpoint on how I teach math now. The kids are so much more engaged

American Indian Education, 46(3), 94-115.

and excited, and there’s so much context for the mathematics.”

Lipka, J. (2002). Connecting Yup’ik elders knowledge to school mathematics. In M. de

And as an artist, Christina has reflected how this experience now impacts Monteiro (Ed.) Proceedings of the Second International Conference on Ethnomathematics

(ICEM2), CD Rom, Lyrium Communacao Ltda, Ouro Preto, Brazil.

her artistic process. “It’s easier to create patterns once you understand that

there are numbers there, not just beads, so I’ve started looking at it from a Lipka, J. (1994). Culturally negotiated schooling: Toward a Yup’ik mathematics.

totally different perspective.” Journal of American Indian Education, 33, 14-30.

6 Principal Connections • Winter 2015 • Volume 19 • Issue 2YOU EARN

YOU EARN 50%50% ON

ON EVERY

EVERY SALE

SALE YOU

YOU MAKE

MAKE

ALL P

ALL RODUCTS A

PRODUCTS RE G

ARE UARANTEED

GUARANTEED

C ANADA’S G

CANADA’S REEN F

GREEN UNDRAISER

FUNDRAISER

A LL S

ALL ALES M

SALES AT

A TERIAL IIS

MATERIAL SF REE

FREE

ALL SHIPPING

ALL SHIPPING IS

IS FREE

FREE

Call or click today to receive your FREE Information Kit & Supplies

1-800-363-7333 • www.veseys.com/fundraisingDr. Pamela Rose Toulouse, Laurentian University

FOSTERING INDIGENOUS

INCLUSIVE SCHOOLS

Integrating Indigenous teachings and values into the school community is a challenge that

principals and vice-principals are entrusted with today. This comprehensive task is one that

is framed within the Ontario First Nation, Métis and Inuit Education Policy Framework (2007);

however, the implementation of this framework in provincial schools is varied in its results.

School leaders are the day-to-day champions of inspiring and facilitating transformational change.

Principals and vice-principals have the unique opportunity to foster a school culture that honours

Indigenous peoples and their worldviews. So, how can this be done? What are the strategies, factors

and resources that contribute to a school that is First Nation, Métis and Inuit (FNMI) inclusive?1

This article explores the challenge through key questions (with suggestions for change) in the

physical, emotional, intellectual and spiritual domains.

THE PHYSICAL THE EMOTIONAL

The physical domain refers to the spaces (walls, The emotional domain refers to authentic connections

architecture, signage, outdoor areas, branding) that made with the FNMI community. It is further described

your school represents and occupies. It goes beyond as the concrete and co-developed strategies for FNMI

bricks and mortar and responds to the presence that community engagement. Questions to reflect on and

your school emits. Questions that focus on the inclusion further research are:

of Indigenous peoples in these spaces are: • Is there a parental/guardian engagement plan in

place that focuses on FNMI families? Are there

• Does the school environment reflect FNMI linkages in this plan made with various agencies to

culture? Take a concrete look at the entry, library, support FNMI families?

bulletin boards, cafeteria, gymnasium, offices and • Do you have connections to FNMI groups and

other rooms. resources that are available in the area? Fostering

• Is there language that reflects the FNMI these connections will be critical to your linking

communities in your area? Have you identified the FNMI students, families and teachers/staff with

Nation 2 – the FNMI community – that the school appropriate services and knowledge keepers.

community resides upon? Every school in Ontario • Do you know who your FNMI students are?

is built on Indigenous lands or treaty territories. What about their familial status? Many FNMI

Acknowledging the territory upon which the school families include extended members that are

is built is fundamental to respectful leadership. highly involved in child rearing. Accessing

• Are there Indigenous symbols or teachings this information may be as easy as examining

visible for students and staff? Once you have the nominal roll through existing tuition

done this inventory, it is critical to do a member agreements with First Nation communities, or

check. This means working with your FNMI through information acquired in a board-wide

Lead, FNMI education counsellor or respective planned FNMI self-identification strategy, or

Indigenous organization to assess the quality of (the most sustainable) your connections with

these spatial messages. FNMI human resources.

8 Principal Connections • Winter 2015 • Volume 19 • Issue 2THE INTELLECTUAL CONCLUSION

The intellectual domain refers to the curriculum, policies and profes- A holistic approach that addresses the physical, emotional, intellectual and

sional learning communities that are available in the school and board at spiritual domains is one of the ways for principals and vice-principals to

large. Questions to consider as part of this journey towards Indigenous integrate Indigenous teachings and values into the school community. It

inclusion are: is a task that requires a school leader to be open-minded, committed and

• Does the school curriculum include FNMI resources at all levels responsive to change. The benefits of infusing Indigenous worldview

in a meaningful way? Examine long-range plans to determine into the school environment goes beyond building relationships, it is

opportunities for Indigenous enrichment. Assess the availability and fundamental to learning communities that are constructed upon principles

diversity of FNMI resources in your library. of compassion, truth, citizenship and reconciliation.

• Who is your board’s FNMI Lead? And if there isn’t one, what steps

are needed to create this critical position for your school? There

are FNMI Leads all across Ontario that are doing amazing work in References

raising the profile of Indigenous pedagogy in schools. 1

FNMI is the abbreviated term for First Nation, Métis and Inuit. FNMI and the

• Are there professional development opportunities for teachers to learn word Indigenous will be used interchangeably in this article.

about implementing FNMI resources? Many educators are hesitant

about infusing FNMI teachings out of fear of getting it wrong. Relevant

2

Nation refers to the FNMI community that the school is located on. Every school

in the province of Ontario is built on Indigenous lands or treaty territories.

PD can address these vulnerabilities in a supportive manner.

• Has your board created and/or adapted an Indigenous Presence in Ontario Ministry of Education. (2007). Ontario First Nation, Métis and Inuit

Our Schools Handbook (2013)? There are many examples across the Education Policy Framework. Toronto, ON: Queen’s Printer.

province of Ontario that are wise practices. These handbooks are

Lakehead Public Schools. (2013). Aboriginal Presence in Our Schools: A Cultural

valuable for teachers and staff in understanding basic information

Resource for Staff (Edition 3, Working Document). Thunder Bay, ON: Same as Author.

about FNMI peoples in the area, as well as implementing culturally

appropriate teaching and communication strategies.

• What types of relationships exist with Indigenous organizations in

the critical areas of assessment, literacy, numeracy and mental health?

These organizations are leaders in Indigenous research and have

access to information/tools/services that are relevant for all students.

Dr. Pamela Rose Toulouse is an Associate Professor in

the Faculty of Education at Laurentian University in

THE SPIRITUAL Sudbury, Ontario. She is also a proud Ojibwe woman

from Sagamok First Nation.

The spiritual domain refers to the school culture and evidence-based con-

scientiousness in appreciating Indigenous worldview. It further signifies

the building of meaningful relationships with the Indigenous community

in a reciprocal and respectful way. Questions to investigate are:

• Are Elders, Métis Senators and FNMI cultural resource people

accessible to the school? These human resources provide a first-hand

learning experience that cannot be duplicated. Their knowledge and

skills are examples of primary sources. How Important Is It To See Yourself Reflected In

School? Video by Pamela Toulouse

• Are there opportunities for classes to link with FNMI geographical

bit.ly/1OeKJFW

sites of significance? Going to a location where history lives OR a

place that has special meaning for Indigenous peoples is central to

experiential learning. A school leader has the opportunity to provide

connections to the community and access funds for classes to attend

a place of cultural importance. Learn More

• What types of FNMI events does your school plan OR attend in an

FNMI setting? June 21 is National Aboriginal Day, however, there Ontario First Nation, Métis and Inuit Education Policy

are so many Indigenous events and celebrations that can be infused Framework (2007)

www.edu.gov.on.ca/eng/aboriginal/fnmiFramework.pdf

into the school calendar.

• How do you assess the integration of FNMI teachings/resources/

Teaching First Nations Children: Lakehead University

connections and their impacts on the school (students, teachers,

www.edu.gov.on.ca/eng/aboriginal/1ALakehead.pdf

staff, administration)? This is crucial and requires a multi-layered

inquiry approach. Evaluating change (positive/negative) is needed Capacity Building Series: Student Voice

as signs for the direction your school needs to take in the area of bit.ly/1Gwcya4

Indigenous inclusion.

Principal Connections • Winter 2015 • Volume 19 • Issue 2 9Kevin Greco, Principal

St. Marguerite d’Youville

Dufferin-Peel CDSB

SHARING CULTURES

SHAPING FUTURES

St. Marguerite d’Youville bridges schools

of the North with schools of the South

student/teacher excursion to Iqaluit, Nunavut, is just one of

the many ways St. Marguerite d’Youville Catholic Secondary

School is working toward building a bridge and meeting the

goals outlined in the Ontario First Nation, Métis, and Inuit

Education Policy Framework, 2007.

This framework and the Ontario Indigenous Education Strategy state

that the ministry, boards and schools must work together to improve

the academic achievement of Indigenous students and close the gap in

academic achievement between Indigenous and non-Indigenous learners.

The ministry has identified a number of overriding issues affecting

Indigenous student achievement. St Marguerite d’Youville Catholic

Secondary School is attempting to address the issue that there is a lack of

understanding within schools and school boards of First Nation, Métis

and Inuit cultures, histories and perspectives.

Our school has engaged in many approaches to foster greater understand- THE IQALUIT EXCURSION

ings. These include staff professional development, First Nations, Métis,

Inuit Studies course offerings, school-wide presentations, classroom The Iqaluit excursion is an extension of our learning and our vision to

workshops, enhanced resources for our library, incorporating Indigenous build awareness and understanding of the complexities of Inuit culture

education into our Alternative Education Program and, most recently, a and history and to begin to provide a curriculum that facilitates learning

nine-day student excursion to Iqaluit, Nunavut with Archbishop Romero about all Canada’s First Peoples. The intent is also to help develop

Catholic Secondary School. community partnerships and implement strategies that facilitate increased

participation by First Nation, Métis and Inuit communities in Catholic

With extensive support at the system level and through collaboration school curriculum.

with the Dufferin-Peel CDSB Program Department we were able to

“facilitate professional development opportunities for teaching staff During their time in Nunavut, our students had opportunities to dialogue

to assist them in incorporating culturally appropriate pedagogy into with Inuit Elders, explore the vast and beautiful northern landscape, and

practice to support Aboriginal student achievement, well-being and sample traditional country food including arctic char, ptarmigan, beluga,

success” and “identify opportunities for the sharing of promising polar bear, caribou and bannock. They also spent time with the Inuit

practices and culturally appropriate/responsive resources to better meet community. Here they were able to learn about amauti, sing and drum

the learning needs of First Nation, Métis and Inuit students” as outlined with Inuit throat-singers, listen to traditional story-telling, build igloos,

in the Ontario First Nation, Métis, and Inuit Education Policy Framework practise Arctic Winter Games and make traditional tools such as ulus. Our

Implementation Plan 2014. students heard first-hand from experienced hunters about the traditional

10 Principal Connections • Winter 2015 • Volume 19 • Issue 2All students in Ontario will have knowledge and appreciation of contemporary and traditional

First Nation, Métis and Inuit traditions, cultures and perspectives.

Ontario First Nation, Métis, and

Inuit Education Policy Framework, 2007

LEARNING BESIDE EACH OTHER

ways of surviving out on the land in a harsh landscape in unforgiving Fundamental to the Iqaluit excursion are activities that highlight Reciprocal

weather. They went dog sledding, hiking, visited Hudson Bay Ridge Teaching. This coincides with the Four Rs of Indigenous education reform

and, during their Arctic College tour, they were invited to a fashion show and is aligned with our Catholic School Graduate Expectations. Both

hosted by the Fur Design Program. teacher and students are discerning believers formed in the Catholic

faith community, intent on participating in the transformation of society.

Students were also able to tour Nunavut’s Legislature. Students Learning beside each other on a journey to better understand human

engaged in discussions with Elders, professors and politicians around dignity and equality.

social and geopolitical connections between the developed and

developing parts of Canada. Nunavut Premier Peter Taptuna and In our pursuit of lifelong learning and in an attempt to be responsible

Commissioner and Assistant to Premier, Ed Pico spent time with citizens embarking on this excursion helped our Non-Indigenous students

our teachers providing first hand insight into some of their current to better understand from where Indigenous students operate. Significant

challenges. Pre and post learning activities exposed students and staff learnings came from the visits to Iqaluit schools. Our students facilitated

to the unique contemporary and traditional First Nation, Métis and fun interactive workshops for elementary students. Through dialogue

Inuit cultures and histories. They were also learned about social justice and presentations with the secondary students, they compared adolescent

issues and outreach within our own Country. experiences, issues and concerns in the north and south cultures.

Principal Connections • Winter 2015 • Volume 19 • Issue 2 11BUILDING OUR BRIDGE

Through our Iqaluit excursion our students experienced first hand

Indigenous sovereignty issues, and the barriers facing Indigenous

peoples in education and employment. They heard directly from

teachers, students, Elders and government officials about the

challenge of maintaining cultural identity while living harmoniously

within modern Canadian society. They critically analyzed negative

stereotyping of Indigenous peoples and learned how Indigenous

identity is closely linked to the physical environment. They have begun

to understand Indigenous peoples’ strong relationship to the land.

Another significant focus of the project was exploring the need to

promote dialogue and reconciliation in the relationship between

Indigenous and non-Indigenous peoples, as well as attempting

to understand the historical relationships between Indigenous

peoples and the Canadian government and Church. Our students

entered into authentic, realistic and sometimes blunt discussions on

social, political, and economic issues important to Inuit individuals

and communities in Canada. Our days spent at the Iqaluit

schools allowed our students to hear from other students about

the challenges facing Inuit youth in Canada and contemporary

Indigenous education and health issues.

Our hope for our students is that they will begin to unravel truth

and wholeness of our Canadian history. If we ignore any part of our

Canadian history; our history is not complete. As Catholic educators

we are called to build these relationships and share with First Peoples

of Canada as allies in the pursuit of reconciliation with all Canadians.

We believe this type of experiential learning empowers our students

with first-hand knowledge so they can act as agents for change

in the future. This outreach extends beyond a charity model to

understanding the complexities of resources, governance, politics

and the global citizenship as steward of our God-given resources.

As part of this yearlong project the students built strong positive

connections with local First Nations and Northern Inuit groups.

Sharing Cultures, Shaping Futures - Nunavut 2015

video: bit.ly/1XczPWX

TeachOntario Talks multimedia blog

www.teachontario.ca/community/explore/

teachontario-talks/blog

Learn More

Capacity Building Series: Cultural Responsive Pedagogy

bit.ly/1gnN1hP

As Solid Foundation: Second Progress Report on the

Implementation of the Ontario FNMI Education Policy Framework

www.edu.gov.on.ca/eng/aboriginal/ASolidFoundation.pdf

12 Principal Connections • Winter 2015 • Volume 19 • Issue 2Pam Garbutt, Principal, St. Timothy Elementary School

Tammy Webster, FNMI Consultant, Waterloo CDSB

THE METAPHOR OF THE CIRCLE

Infinite possibilities for leading and learning: the circle in First Nations and Christian cultures

Without beginning or end, circles commonly represent unity, wholeness and

infinity. Circles are often seen as protective symbols. For example, standing

within a circle can shield a person from dangers or influences from the outside.

The circle itself signifies inclusion, safety and belonging.

Many of the world’s religions and cultures refer to the symbol Since the beginning of man, the human experience of real-

and metaphor of the circle to depict and explain inclusivity ity and mystery has been linked to the symbol of the circle.

and equality. In our Catholic tradition, circles are inferred in The directions on a compass, the positioning of the sun, the

many faith-based concepts. Christ is worshiped as the Alpha progression of the seasons, the relationship between the ele-

and Omega, meaning He is the first and the last, the beginning ments of life, the earth, sun, water and air, the journey from

and the end of all creation. Our liturgical year follows a cyclical life to death, all follow cyclical patterns. The circle itself is

pattern including the liturgical seasons of Ordinary time, Advent, a metaphor used to describe all aspects of life and a person’s

Christmas, Lent and Easter. The most revered of our beliefs, the unique and yet interconnected role within God’s creation of

Resurrection cycle and Paschal Mystery connect to the cycle of the universe.

dying and rising above our earthly sufferings.

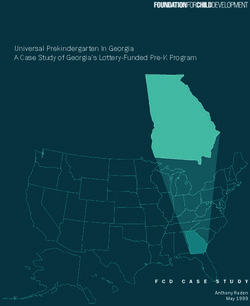

Principal Connections • Winter 2015 • Volume 19 • Issue 2 13ESS BA

EDN LA

NC

T

EC E

WEST NORTH

N

/R

ON

emotional mental

ES

-C

PE

personal cultural

ER

CT

INT

generational epistemological

reason movement

"figure it out" "do it"

heart & head language

SOUTH EAST

physical spiritual

ecological local knowledge

time cultural, worldview

"relate to it" vision

INT

land "see it"

ER

SS

teachings

-R

AT

NE

EL

stories E

I ON OL H

SH W

IP

Bell, N. (June 2014). Teaching by the Medicine Wheel: An Anishinaabe framework for Indigenous education. Education Canada, vol. 54(3)

First Nation peoples, recognize the importance of the circle Bell’s Medicine Wheel diagram included with this article,

in much of their teachings. The circular “Medicine Wheel” reviews the circle divided into quadrants. These symbolize the

represents Wakan-Tanka or “The great everything” or universe. gifts of the four Directions. In the East, the gift of vision is found,

The Medicine Wheel is among the oldest of the First Nation where one is able to see. In the South, one uses the gift of time in

traditions and essentially teaches the meaning of life through which to relate to the vision. In the West, the gift of reasoning is used

their central belief that promises unending and judicious care for to figure out the vision. In the North, one uses the gift of movement

the land and each other. to do or actualize the vision. (Bell, June 2014) The fourth gift

importantly, involves creating healing and change. Change and

understanding is only possible when the other directions have

The Medicine Wheel previously been considered.

The First Nations concept of medicine is not the same as the According to Bell, “Understanding First Nations knowledge

modern medicine that we think of today. It is not a procedure or and worldview begins with Medicine Wheel teachings (vision,

pill that can cure a person’s physical ailment. The First Nations time, reason, movement ) and the actions of these gifts; see it,

people refer to medicine as the vital power or force that is inherent relate to it, figure it out, do it. These actions in turn connect to

in nature itself and to the personal power within one’s self which the learning processes of awareness, understanding, knowledge

can enable one to be whole, complete and well. and wisdom. (Bell, June 2014)

MEDICINE = ENERGY = POWER = KNOWLEDGE First Nations spirituality as depicted in the Medicine Wheel, can

easily be compared to our Catholic faith, tradition and culture.

It is important to note that the Medicine Wheel can mean many We grow and develop in a natural and holistic way, whereby

things on many levels. It has been said that the grains of sand teaching and learning are lifelong quests nurturing our mind,

on the beach can outnumber the teachings and mysteries that body and spirit toward understanding God’s purpose and plan

the wheel or circle can attempt to explain. The Medicine Wheel for our existence. Catholic social justice teaching calls us to be

depicts a circle of self-awareness and knowledge that gives one a visible and active source of healing in the world, connecting

power over one’s life. Each First Nations clan may have their the human mind, body and spirit in deep caring for each other.

own interpretation of the wheel based on their location. Nicole Catholic liturgical expression emphasizes the cycle of repentance

Bell comments, “There is no right or wrong way to represent the (see), listening to the Word (time), relating the Word to our

wheel.” The common understanding is that the wheel represents lives (reason) and going forth, (movement) to make a positive

the interconnectedness and interrelatedness, balance, and difference in the world in the name of God The Father, The Son

respect of all things in nature and the universe. and The Holy Spirit.

14 Principal Connections • Winter 2015 • Volume 19 • Issue 2Circles Forward

The Medicine Wheel, can represent limitless metaphors Health and Physical Education Curriculum

related to our earthly experience. This is worthy of

consideration and reflection in contrast to our experience

of Catholicism. How can we find personal wellness and

Catholic Administrators' Toolkit

wholeness by adopting a mindset that actively seeks, accepts

and connects us to the cycles found within our lives? How

does our spiritual wisdom grow and change throughout our

lives? How can we use our God-given/creator-given gifts

and talents to benefit others on their life journey?

The teachings of the Medicine Wheel in comparison to

the teachings of our Catholic faith offer an educational

framework that can be applied to any spiritual learning

and discernment. Good leaders understand the power

found in the metaphor of the circle. This is because the

fundamental concepts of connectedness, inter-relationship,

balance and respect are valuable for all. (Bell, June 2014)

These values resonate in the hearts of all humans. This is

the place where the mind, body and spirit converge and the

opportunities to learn about oneself are endless.

We are holistic beings seeking understanding and to be

understood. The circle when used in a faith-based con- This online toolkit will:

text can provide limitless possibilities to celebrate our

sense of self, belonging, power, justice and joy. Catholic • Include presentation materials (slides) for

leaders can ref lect on the symbol of the circle when estab- parents and for educators, responses to

lishing and maintaining a school culture that builds upon frequently asked questions and a facilitator’s

positivity, inf luence, healing and change. The possibili- guide with tips and strategies

ties are truly infinite.

• Build administrator understanding of the key

Reference: components and key changes in the curriculum

Bell, N. (June 2014). Teaching by the Medicine Wheel: An

Anishinaabe framework for Indigenous education. Education • Support administrator dialogue with parents

Canada, vol. 54(3)

(individually or in groups), community partners

and Catholic educators about the updated

Health and Physical Education curriculum

Want to go deeper and learn more about

using circles with students? Check out the • Support partnerships between educators and

following resource: parents to positively impact the health and

well-being of all students.

Boyes-Watson C. and Pranis K. (2015)

Circles Forward: Building a Restorative School

Community, Institute for Restorative Justice This FREE resource is available to all our

Press, St Paul MN. Associates on www.cpco.on.ca under:

www.livingjusticepress.org

Associates ▶ Resources ▶ Health and Physical Ed

Learn More

Serve. Advocate. Lead. www.cpco.on.ca

For personal mental wellness and restorative

practice, see CPCO’s new resource: C AT H O L I C Box 2325, Suite 3030, 2300 Yonge

ONTARIO

Starling Minds (Associates only). PRINCIPALS’ Street, Toronto, ON M4P 1E4

www.cpco.on.ca/starlingminds COUNCIL 1.888.621.9190 toll free

Principal Connections • Winter 2015 • Volume 19 • Issue 2 15Sandra Mudryj, Principal, St. Patrick Catholic School, Toronto CDSB

Dr. Frank Pio, ED.D., Program Support Teacher, Toronto CDSB FMNI Program

10 STEPS

TO START THE CONVERSATION

Acknowledging the 500+ year narrative of Canada’s Indigenous people for your Catholic school community

WHERE DO YOU START A MORE THAN 500-YEAR-OLD STORY TO church-run boarding schools far from their home communities. In these

BUILD AN INCLUSIVE COMMUNITY IN A CATHOLIC SETTING? schools children endured emotional, physical and sexual abuse, which

has left lasting impacts on Indigenous communities and culture. The last

As school leaders we have a moral imperative to establish tangible steps residential school in Canada closed in 1996.

to create an inclusive educational community where the narrative can be

heard and shared in a safe and respectful forum. The narrative of Canada’s As Catholic educators, we must be mindful of the past as we educate our

Indigenous peoples is one of a history of cultural and physical abuse. students in learning about the narrative of our country’s Indigenous

peoples and how as Canadians we can move forward. Engagement of

This narrative begins with the Royal Proclamation of 1493 by King students, parents and staff of First Nation, Métis and Inuit (FNMI)

Ferdinand and Queen Isabella of Spain. Pope Alexander, through the background requires us to be conscious of the history and legacy of

Doctrine of Discovery, decrees that non-Christian nations may no longer Canada’s Indigenous peoples. The pedagogy must be respectful of the

own land in the face of claims made by Christian sovereigns. In effect, traditions, culture and spirituality of Indigenous peoples.

Indigenous people were placed under the guardianship of Christian

nations. Next is the 1867 British North America Act and the 1876 Indian The following 10 steps provide examples of how the Toronto Catholic

Act, which further confirmed that Canada’s Indigenous people were under District School Board (TCDSB) began this conversation, and how

the direct control of the Canadian Federal Government. the board has set the direction for acknowledging the narrative of

our FNMI students and sharing of the story of Indigenous peoples in

Through the Indian Act, the government denied Indigenous peoples the Canada. Central to this is the building of relationships and connections

basic rights that most Canadians take for granted. This was followed with the FNMI community to help provide schools with the necessary

by the federal government’s removal of Indigenous children from their resources to engage Catholic school communities in meaningful

communities from 1820 to the 1970s. Indigenous children were placed in learning experiences.

16 Principal Connections • Winter 2015 • Volume 19 • Issue 21. BUILDING COMMUNITY 7. CLASSROOM ACTIVITIES

• Engage in dialogue with family connections within your school • Include class activities on topics such as the Blanket ceremony (www.

community (e.g. parents, students, grandparents) by creating an kairosblanketexercise.org), drum and dance presentations, treaties,

environment where the student sees themselves and their heritage demystifying false stories, stereotyping and dream catchers.

both in the school and in the curriculum. • TCDSB initiated the The Northern Spirit Games in 2007. Each year

• TCDSB created a poster campaign entitled “I AM…,” which is made 1800 elementary students from Grades 4, 5 and 6 are hosted by six

up of a mosaic of current self-identified students in the board and is high schools. The students participate in traditional First Nations,

displayed prominently in all schools. Métis and Inuit games, which focus on physical strength, agility

and endurance. This includes a hand drum session led by a FNMI

2. ROLE OF SCHOOL LEADER Knowledge Keeper. Over 20,000 students have participated over the

• As school leaders, actively seek out opportunities to participate in past nine years.

FNMI ceremonies so that you better understand the intricacies of

the heritage and cultural traditions (smudging, etc.) 8. CATHOLICITY & NATIVE SPIRITUALITY

• TCDSB hosted a CPCO conference in 2012 for Catholic principals • Invite storytellers to share FNMI oral tradition and teachings that

which featured a session entitled “Leading The Instructional convey a moral lesson that connects to our Catholic virtues and faith,

Program: Fostering An Understanding of Aboriginal Perspectives in incorporating traditional spiritual ceremonies such as smudging.

An Inclusive School Community.” • TCDSB is piloting an Elder in Residence Program. Working in

collaboration with community partners, an Elder will identify and

3. PROFESSIONAL DEVELOPMENT FOR TEACHERS address topics relevant to the health, including mental health, and

• To enable teachers to continue the story telling after the experts well-being of Aboriginal students in our board.

leave; establish professional development for teachers to ensure that • Since 2013 a traditional storyteller has visited elementary and

the message and community connections are sustainable and viable. secondary schools across TCDSB.

This comes through only when you develop a sense of trust with

community members, which is authentic and respectful. 9. MENTORSHIP

• TCDSB has hosted yearly Teacher Symposiums since 2010. Topics • Develop mentorship programs for your school that connect to local

have included FNMI curriculum, teaching and learning, culture and communities by inviting FNMI members and academic experts

identity, community and student voices. from OISE, York University, University of Toronto and McMaster

University. Mentors include Elders and mentees who are FNMI

4. RESOURCES undergraduate and graduate students, sharing their personal journey

• Each board is mandated by the ministry to have a FNMI lead teacher and stories.

to create a Board Action Plan to obtain funding and resources to • A TCDSB school mentorship program started in 2014. In partnership

support FNMI projects and initiatives. FNMI credit-bearing courses with OISE/University of Toronto, the TCDSB Aboriginal Mentorship

also receive direct ministry funding. Program is an opportunity for OISE Aboriginal undergraduate and

graduate students and First Nation Elders to work as peer mentors

5. FNMI PARTNERSHIPS with students in the classroom from Kindergarten to Grade 12.

• Foster partnerships with the Aboriginal community by inviting

Elders and FNMI organizations to develop and lead workshops for 10. OUTSIDE AGENCIES

teachers and students. • Access agencies outside of the FNMI community such as public

• TCDSB has partnered with members of FNMI communities to libraries, the Royal Ontario Museum, The Bata Shoe Museum and

create opportunities for elementary and secondary school visits on the Aboriginal Education Office at the Ministry of Education.

topics that include: History and Treaties; Contemporary Issues of • Since 2011 the TCDSB and the Toronto Public Library have hosted a

FNMI Peoples; Myths; Stereotypes and Misconceptions of FNMI series of workshops detailing First Nation, Métis and Inuit Children’s

Peoples; Protocols; Melding of Traditions and Contemporary Life. Books for Elementary teachers from Kindergarten to Grade 6.

6. SCHOOL-WIDE ACTIVITIES

• Introduce tangible initiatives to your school, such as including prayers As school leaders, we need to work in partnership with the FNMI

for morning announcements, displays in hallways, and recognition of community to tell this story to all our students. This narrative varies

June 21st National Aboriginal Day from region to region and community to community particularly within

• Since 2010, the TCDSB has hosted National Aboriginal Week with larger urban settings such as the Greater Toronto Area. The continual and

FNMI speakers, dancers, storytellers, art exhibitions and music. collaborative effort requires engagement and input with all stakeholders:

These events are open to elementary and secondary students, students, parents, staff and the FNMI community. These 10 steps are just

teachers, staff and administrators, and provide a forum to showcase the beginning. It is your role, as the Catholic instructional leader, to ensure

student work relating to FNMI themes. that the narrative continues, is shared, and becomes part of your school

culture and community.

Principal Connections • Winter 2015 • Volume 19 • Issue 2 17You can also read