Prehospital paediatric emergency care

←

→

Page content transcription

If your browser does not render page correctly, please read the page content below

26 Review Articles Medical Education

Prehospital paediatric

emergency care

Citation: Kaufmann J, Laschat M, Wappler F: Prehospital paediatric emergency care.

Anästh Intensivmed 2020;61:026–037. DOI: 10.19224/ai2020.026

Summary more, competency and technical re 1 Abteilung für Kinderanästhesie,

Kinderkrankenhaus der Kliniken der Stadt

sources are not identical to those found

Because prehospital paediatric emer- Köln gGmbH

in a specialised environment, e.g. a (Direktor: Prof. Dr. F. Wappler)

gency care is commonly rendered by

paediatric emergency department. In a 2 Fakultät für Gesundheit, Universität

non-specialist teams, always operating Witten/Herdecke

prehospital environment, paediatric

in a suboptimal environment, simple (Dekan: Prof. Dr. S. Wirth)

emergencies and – for example – en-

and feasible treatment recommendations

dotracheal intubation are so uncommon

are required. First and foremost, these

that practice solely in this environment

are provided by the resuscitation guide-

cannot provide for advanced experience

lines, which provide recommendations

[1].

consistent with the above premise not

only for cardiac arrest but for most other

important situations. The laryngeal mask More than 80% of emergency physi-

airway and the intraosseous needle are cians are afraid of being over-

essential technical adjuncts for airway whelmed by paediatric emergencies

management and venous access respec- or have experienced overwhelming

tively. Equipment must be provisioned in such a situation [2].

for each and every age bracket. Simple

basic principles and support provided Complex deficits have been described

by references and aids can increase the in the context of simulated scenarios

safety of drug administration. Sound [3] and prehospital emergencies [4]; for

individual and institutional preparations example, difficulties with endotracheal

for paediatric emergencies ensure safe intubation arose in 2/3 of children

initial care of the child prior to ongoing with head injuries, whilst the same was

treatment provided by specialists. only true of 1/5 of adults in the same

health care setting. At the same time,

Introduction intravenous access was successfully

established in 86% of adults investi

When considering prehospital paediat- gated, whilst the same could only be

ric emergency care, it is imperative to said of 66% of children [5]. The European

develop strategies based on a realistic Resuscitation Council (ERC) Guidelines

analysis of circumstances and available note that due to real-life limitations,

resources, aiming to provide care at the recommendations must be “simple

as close to optimum level as possible. and feasible” [6]. Even though it may

Because the circumstances under which seem remarkable to read this in the Keywords

prehospital care is provided – consider preamble of a guideline, it is precisely Prehospital emergency care

for example the location, e.g. at the this basic nature, seeking compromise, – Children – Drug safety –

roadside – can per se be suboptimal, avoiding excessive burdens on the user Treatment recommendations

compromise is indispensable. Further and providing a clear, easily remembered Medical Education Review Articles 27

and practicable course of action which amenable to defibrillation (approx. 5% – due to their relatively high oxygen con-

is its greatest quality. It is as such that of cases) underscores this mechanism. sumption and small pulmonary residual

these guidelines offer an essential con- volume relative to body weight – the

tribution to safe paediatric emergency Due to the typical pathophysiology reserve in children is small and they will

care. of cardiac arrest, oxygenation and suffer a decrease in oxygen saturation

Based on the aforementioned prerequi- ventilation are the most important within seconds following respiratory

sites, this review takes into account measures in paediatric resuscitation. arrest. On the other hand, the anatomy

the feasibility and effectivity of recom- is advantageous when compared with

mended measures and adjuvants. Those that of the adult, with the larynx situated

• As demonstrated by clear evidence

measures which are either indispensable relatively higher and a factually difficult

and ascertained by all international

(e.g. intraosseous access) or which – airway being rather less common. It has

guidelines, resuscitation of a newborn

whilst requiring only a small effort – been shown that experience and clear

is not possible without successful

would be expected to significantly en- strategies can significantly increase

ventilation, and chest compressions

hance the safety of paediatric emergency safety when managing the paediatric

without ventilation are actually

care (e.g. the laryngeal mask airway) airway.

neither helpful nor indicated [10,11].

are emphasised. A potential desire for • Whilst, at least for lay persons Airway management

paediatric emergency care to be rendered providing telephone-guided aid, Only approximately 5% of prehospital

solely by designated experts in the field resuscitation of adults may be emergencies in Germany involve chil-

is surely an example of the opposite – a performed forgoing ventilation and dren, and of those only approximately

measure requiring insurmountable effort, providing chest compressions only 5% require endotracheal intubation.

especially considering that the required [12], the resuscitation of children Therefore, statistically speaking, emer-

number of experts couldn’t even be pro- has been shown to be associated gency physicians will perform prehos-

vided. Good preparation in a “protected with a significantly higher rate of pital endotracheal intubation of a child

environment” (e.g. simulated scenarios), survival with good neurological once every 3 years, and of an infant once

knowledge of current, simple, structured every 13 years [1].

outcome when lay persons provide

guidelines and the use of adjuvants

chest compressions and rescue

enable non-specialised emergency phy-

breaths [13]. Airway management routine cannot

sicians to provide safe care [7].

• A further observational study involv- be established only by experience as

ing prehospital paediatric resus an emergency physician.

Typical challenges citation also showed conventional

resuscitation incorporating ventilation

Even in paediatric emergency depart-

Oxygenation to be superior. A relatively small

ments, emergency intubation performed

Significance of ventilation for paediatric group of children who received only

by paediatric medical staff was asso-

emergencies ventilations without chest com-

ciated with a serious drop in oxygen

pressions showed even better “good

In contrast to adult resuscitation, in saturation in almost half of the cases. 2

neurological” outcomes [14]. This

which cardiac arrest mostly arises from out of 116 children even suffered hy-

group was too small to deliver a

a cardiac incident, in children and poxic cardiac arrest [15]. Prehospital

statistically definitive result, but the

especially in a prehospital environment, intubation associated with a lower rate

finding underscores the importance

respiratory causes are usually foremost of complications and higher rate of suc-

of ventilation for the survival of

[8]. Here, cardiac arrest is typically the cess can only be achieved by physicians

children even outside the neonatal

result of a respiratory incident leading to who intubate children on an everyday

period.

myocardial hypoxia. Whilst in an ideal basis. It is for these reasons that the ERC

• In addition, clinical experience shows

scenario, adults whose cardiocirculatory guidelines note that only those who have

very clearly that infants and toddlers

arrest due to ventricular fibrillation is safe command of drugs required for

rapidly terminated by defibrillation cannot be resuscitated without

intubation and are proficient in preoxy-

won’t necessarily suffer tissue hypoxia, ventilation. As such, measures and genation and intubation should consider

the respiratory cause of cardiac arrest adjuncts which enable safe ventilation prehospital intubation [6]. In all other

in children means that serious organ of children are indispensable and, cases supraglottic airways should be

damage has already ensued. This is a whilst requiring only a small effort, the airway adjuncts of choice. Under no

major factor in the lower rate of survival have a significant effect on patient circumstances may repeated intubation

in infants following cardiac arrest when survival. attempts be made, as these may lead to

compared with youths or adults [9]. A Even outside of resuscitation, providing prolonged apnoea and can cause swell-

more favourable rate of survival in those oxygenation and ventilation to children ing and bleeding, leading to a total loss

few children presenting a cardiac rhythm takes on a central role. This is because of the airway.28 Review Articles Medical Education

A prehospital trial involving more than Working Group for Paediatric Anaes- recommendation that invasive tech-

800 children suffering grave conditions thesia (WAKKA) of the German Society niques (cricothyrotomy, tracheotomy,

(cardiac arrest, multiple trauma, head of Anaesthesiology and Intensive Care surgical airway) are never required.

injuries) failed to show any difference in (DGAI) [17]. However, the authors are Needle cricothyrotomy cannot real-

the survival rate or neurological outcome of the opinion that laryngoscopy should istically be performed on infants and

between those primarily successfully be performed at an early stage of man- toddlers as the location coincides with

intubated and those who were mask agement, especially in a prehospital the narrowest section of the paediatric

ventilated [16]. Seeing then that even setting. This way airway obstruction airway and the short neck forces the

successful intubation cannot positively by a foreign body or secretions can operator to adopt a very steep approach

influence the outcome, the rationale be- be detected at an early phase. It is not [18, 19]. If anything, needle tracheot-

hind intubation needs to be questioned. necessary to force the laryngoscope into omy, which likewise is difficult, should

However, mask ventilation by itself is a deep position as for intubation; instead be attempted; the procedure is possible

certainly also not an ideal ventilation it can be sufficient simply to open and with a less steep approach, and the

light up the mouth, making it possible tracheal lumen is wider at this location

strategy in a prehospital setting; it binds

to detect the aforementioned compli- [20]. If at all possible, however, surgical

at least one person continuously and can

cations, suction the airway or remove a tracheotomy – a procedure which can be

be difficult to perform. At that point at

foreign body using Magill forceps. performed by an experienced surgeon

the latest, the use of a supraglottic airway

(including paediatric surgeons) within

is required.

a small number of minutes – should be

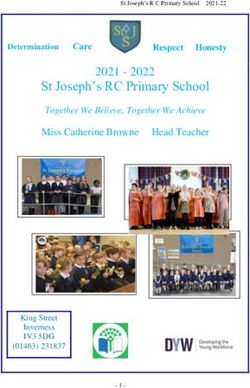

For situations when mask ventilation is It is extremely unlikely that, follow-

preferred [21].

not successful, a clear and simple strat- ing immediate and complete imple-

mentation of the measures set out, The laryngeal mask airway (LM) is the

egy needs to be available for immediate airway adjunct which has been most

ventilation should remain impossible

recall and easy implementation (Fig. 1). thoroughly examined in good clinical

by the point at which a laryngeal

The measures set out should be es- trials for both elective and emergency

mask airway is used.

calated step by step until ventilation of use, is most commonly used, and as

the child is successful. To a significant such is the supraglottic airway adjunct

extent, the algorithm equates to the Based on their own experience however, which can best be recommended for

recommendations of the Scientific the authors do not share the WAKKA use in children from 1.5 kg body weight

(BW) upwards [22]. Evidence for the

use of the laryngeal tube (LT) is not

Figure 1

comparable and consists solely of a

small number of studies demonstrating

mask ventilation impossible

successful use in children from 10 kg

body weight upwards. Despite this

fact, the LT is used surprisingly often in

activate CALL FOR HELP prehospital settings. However, according

EMERGENCY PLAN e.g. consultant, medical supervisor

to current consensus reached by numer-

ous professional bodies, provisioning

escalate until ventilation successful

the LT only whilst forgoing the LM as

DIRECT LARYNGOSCOPY the clearly “better” airway adjunct,

remove foreign bodies,

(to exclude e.g. foreign bodies, blood,

treat laryngospasm cannot be recommended. At the same

secrections, swabs, spasm)

time, provisioning both devices (LM and

LT) and thereby promoting confusion,

increasing costs and taking up addi-

1) jaw thrust, two-person mask ventilation, Guedel airway tional space would seem less than ideal

2) increase anaesthetic depth, decompress stomach

3) supraglottic airways (e.g. nasopharyngeal tube, LM) [22]. For a brief period at least, during

4) neuromuscular blockade intubation or when neither an LM nor

5) (careful) intubation attempt an LT are available, sufficient ventilation

6) intubation aids (e.g. video laryngoscope, bronchoscope)

can almost always be provided using a

7) needle tracheotomy (cricothyrotomy)

nasopharyngeal tube (pharyngeal tube;

a nasally inserted tube in the “Wendl

position”) whilst manually providing

no success: surgical airway

closure of the mouth and contralateral

Algorithm for the management of difficult mask ventilation in a child.

nostril. It is imperative that all the afore-

mentioned adjuncts and techniques Medical Education Review Articles 29

should be trained in the context of job health require larger fluid volumes. pulse oximeter plethysmograph can

shadowing or through participation in The fluid deficit can be categorised point to serious hypovolaemia.

simulated scenarios before they are used by weighing the child or by clinical Deficits resulting in haemodynamic dis-

in paediatric care. assessment (Tab. 2, taken from [27]). ruption and any other situation in which

In addition, respiratory variation of the blood pressure is insufficient with

Cardiocirculatory support

Blood pressure by age

There is good evidence that age adapted Table 1

normal blood pressure values (Tab. 1) Age adapted blood pressure range (min – max) considered safe [25].

are a sufficient therapeutic goal even in Age group Age adapted blood pressure

emergency situations with increased cer-

Preterms (approximation) Mean arterial pressure = gestational age in weeks

ebral pressure [23] and as such should

systolic pressure mean arterial pressure

be achieved, but not overstepped [24].

It is also clear that failing to reach these Preterms 55 – 75 35 – 45

values can cause serious damage. 0 – 3 months 65 – 85 45 – 55

3 – 6 months 70 – 90 50 – 65

Rational infusion therapy

Adequate fluid therapy is the basis of 6 – 12 months 80 – 100 55 – 65

sufficient circulatory support. To avoid 1 – 3 years 90 – 105 55 – 70

hyponatraemia and cerebral oedema 3 – 6 years 95 – 110 60 – 75

only balanced electrolyte solutions may 6 – 12 years 100 – 120 60 – 75

be used. When treating infants (< 1 year > 12 years 110 – 135 65 – 85

of age), the use of solutions containing

additional glucose (1%) is expedient,

if available in the prehospital setting.

Patient safety considerations, however, Table 2

mean that individual blending of such Estimating fluid loss (dehydration) based on clinical signs [27].

solutions cannot be recommended. Signs and minimal/no slight/medium severe

Instead, intravenous boli of 0.1 – 0.2 g/ Symptoms dehydration dehydration dehydration

kg BW glucose can be used to treat low Weight loss < 3% 3 – 8% ≥ 9%

blood glucose levels, which should be Consciousness, health normal agitated, irritable apathetic,

determined for every infant and when or tired lethargic,

confronted with altered consciousness. unconscious

Drinking normal thirsty, drinks greedily drinks poorly or is

Acetate-based balanced electrolyte unable to drink

solutions are the most suitable fluids Heart rate normal normal to increased tachycardia; severen

for maintenance and fluid replenish- cases: bradycardia

ment. Pulse quality normal normal to decreased weak or not palpable

(comparison of central

vs. peripheral pulses)

Basal requirements can be calculated

Respirations normal normal to deep; deep breathing

using the 4-2-1 rule:

increased resp. rate (acidosis!)

• 4 ml/kg/h for every kg for the first

Eyes normal sunken deeply sunken

10 kg BW,

• 2 ml/kg/h for every kg for the next Tears present reduced none

10 kg BW, Mucosa moist dry desiccated

• 1 ml/kg/h for every additional kg Skin folds smooth delayed smoothing, standing > 2 s

BW. immediately but ≤ 2 s

To balance deficits caused e.g. by preop- Capillary refill normal prolonged (< 3 s) severely prolonged

(> 3 s)

erative fasting, in keeping with the above

Urine production normal reduced oliguria or anuria

recommendation for basal requirements,

the basal requirement for the first hour Fluid loss < 30 mild 30 – 50 > 100

(ml/kg BW)* medium 50 – 100

can be assumed to be a blanket 10 ml/

kg/h [26]. Children suffering exsiccosis Resp.: Respiratory; BW: Body weight;

* for children < 6 years of age; school children and adults require smaller fluid volumes due to their

in the context of vomiting and diarrhoea

smaller extracellular space relative to body weight.

or inadequate fluid intake due to poor30 Review Articles Medical Education

out clear cause should be treated by adrenaline should be carefully titrat- ml, from the 7th year of life on 0.5 to

administration of a 20 ml/kg BW fluid ed and used only in conjunction with 1.0 ml administered intramuscularly

bolus with subsequent re-evaluation an inotropic catecholamine. or intravenously as a single dose…”

[6]. Current knowledge suggests that for Experience suggests that a quarter of this

children with fever and serious infec- dose should be given initially and the

In prehospital situations, safe and rapid

tious disease (e.g. pneumonia, sepsis) drug then titrated according to effect. It

treatment with catecholamines can be

fluid should, when possible, only be is also possible to bolus 0.5 (-1) µg/kg

administered in this fashion once [28] difficult to implement, particularly be

cause drug choice and dose are often adrenaline, whereby the effect is short

and catecholamines introduced early. lived and repeat doses may be required.

Repeated administration may be neces unfamiliar, and dopamine and in some

sary, especially when treating exsiccosis cases syringe drivers, are not routinely

provisioned by emergency services. Injecting the contents of a 1 ml = 1 mg

and hypovolaemia; however, an (ad-

ditional) drop in haemoglobin levels As such, it is necessary to stabilise ampoule of adrenaline into a bottle

through haemodilution should be kept the cardio-circulatory situation during containing 100 ml of isotonic saline

in mind. Whilst the use of colloids is transfer to a paediatric intensive care or (NaCl 0.9%) results in a concentra-

typically not necessary and their value emergency facility using a simple and tion of 10 µg/ml, which can then be

unclear, attempted treatment of an safe concept. Cafedrine/Theodrenaline dosed highly accurately using 1 ml

otherwise unstable circulatory situation (Akrinor®) is an example of a suitable syringes with a 0.01 ml scale.

by admin istration of 5 – 10 ml/kg BW, drug. The manufacturer’s summary of

taking the manufacturer’s recommen- product characteristics recommends the

following doses [43]: “…Children: de- Gaining access for drug administration

dations regarding contraindications and

pending on the severity of the condition, and fluid therapy

maximum doses into account (e.g. 6%

HES 130/0,42: 30 ml/kg), can be justi- in the 1st and 2nd years of life 0.2 – 0.4 Placement of an intravenous catheter

fied [27]. ml, in the 3rd to 6th years of life 0.4 – 0.6 can often be difficult in paediatric emer-

Rational use of catecholamines

The aim of treatment with catechola- Table 3

mines is to re-establish adequate perfu- Prehospital treatment of children with haemodynamic shock using catecholamines.

sion and oxygenation of the organs. A

Type of shock Catechola- Dose Rules of thumb

significant intraindividual variability in mine a) Preparation

pharmacokinetics and -dynamics [29] b) Dosing

and the effect of catecholamines can be c) Escalating treatment

observed in infants and toddlers (due, hypody dopamine 5 – 20 µg/kg/min a) 1 ampoule dopamine 5 ml = 50 mg;

amongst other things, to individual re- namic/ 1 ml = 10 mg + 29 ml NaCl 0.9%

cardiogenic, → 0.33 mg/ml

ceptor density and intracellular response b) rate (ml/h)) = body weight equating to

preterms and

[30,31]). When there is no response to newborns 6 µg/kg/min

treatment, increasing the dose by one c) dobutamine, hydrocortisone, adrenaline

order of magnitude is recommended, hypody dobutamine 5 – 20 µg/kg/min a) 1 ampoule dobutamine 50 ml = 250 mg;

titrating down once an effect ensues [32]. namic/ draw up undiluted → 5 mg/ml

cardiogenic, b) rate (ml/h) = 1/10th body weight age

Another peculiarity when compared to all other age brackets equating to 8 µg/kg/min

the treatment of adults is the use of do- brackets

pamine which, on the basis of available hypovolae- adrenaline 0.05 – 2.5 µg/kg/min a) 1 ampoule adrenaline 1 ml = 1 mg;

data, is still the most commonly used mic 6 ml = 6 mg + 44 ml NaCl 0.9%

catecholamine in newborns, infants and → 0.12 mg/ml

b) rate (ml/h) = 1/10th body weight equating

toddlers [32,33]. Table 3 summarises the to 0.2 µg/kg/min

catecholamine of choice for treatment

septic adrenaline 0.05 – 2.5 µg/kg/min a) 1 ampoule adrenaline 1 ml = 1 mg;

of different types of shock in children 6 ml = 6 mg + 44 ml NaCl 0.9%

based on current guidelines [34–42] and → 0.12 mg/ml

provides “rules of thumb” for prepara- b) rate (ml/h) = 1/10th body weight equating

to 0.2 µg/kg/min

tion of and dosing with syringe drivers. c) noradrenaline carefully titrated, only if

extremities warm

Even for septic shock, noradrenaline additionally, noradrena- 0.05 – 2.5 µg/kg/min a) 1 ampoule Noradrenalin 1 ml = 1 mg;

is not the catecholamine of choice in as required: line 6 ml = 6 mg + 44 ml NaCl 0.9%

→ 0.12 mg/ml

children because the increase in af- b) rate (ml/h) = 1/10th body weight equating

terload rapidly leads to a decrease to 0.2 µg/kg/min

in contractility [32]. As such, nor Medical Education Review Articles 31

gencies and may be impossible in some ministration of drugs, and most which point on overdosing adrenaline is

circumstances, e.g. exsiccosis or cardiac drugs achieve bioavailability similar potentially fatal, there is no doubt that

arrest. In prehospital emergencies of this to that following intravenous admin- overdosing by an order of magnitude

kind, placement of a central venous line istration. (1,000% of the recommended dose;

is inarguably not a suitable alternative. 100 µg/kg BW) is not compatible with

survival [47]. All international guidelines

Doses similar to those used for intra-

The intraosseous (IO) needle is a warn explicitly of overdosing adrena

venous administration can often be

quick, easy and safe adjunct for ac- line during resuscitation of paediatric

used for intranasal administration. The

cess to the vascular system. patients of any age. Vigilance derived

total should always be split across both

simply from awareness of the danger

nostrils so as to utilise the maximum

and recognition of personal fallibility is

Complications are rare and are only possible mucosal surface. Administered

pivotal for drug safety [48].

to be expected when the needle remains volumes should preferably be 0.2 – 0.3 ml

in situ for prolonged periods of time. The per nostril and should not exceed 1 ml. Using simple measures can help achieve

current ERC Guidelines recommend the Copious quantities of secretions or blood a significant increase in drug safety when

use of an IO needle in all critically ill can inhibit adequate resorption from the caring for children [49,59].

children in whom venous access has not nose, making cleansing or selection of an

been able to be established within one alternative method necessary. Published It can safely be assumed that any

minute [6]. The most suitable and typi- experience is available especially for measure which reduces the cogni-

cal location in children is the proximal • midazolam tive load of the prescribing physician

anterior tibia. Use of IO needles can • fentanyl will increase drug safety in children.

be trained using chicken bones, which • sufentanil

provide for very realistic conditions. • ketamine and

It is essential that training should take In a test of written orders for adrenaline

• dexmedetomidine administration for resuscitation, for ex-

place before taking on work in emer-

gency care. Intraosseous drills (EZ-IO®, ample, use of a simple table was shown

Drug safety in paediatric emergency

Teleflex), which are widely available in to avoid nine out of ten single order of

care

Germany, are not suitable for newborns magnitude errors, and the same fraction

and small infants weighing less than 3 kg. of errors by two orders of magnitude

Grave errors occur regularly during

The tibial spongiosa is so shallow in [51]. A similar effect was also seen

paediatric emergency care, even in

these children that there is a risk the when the Paediatric Emergency Ruler

specialised facilities such as paediat-

posterior cortex could be pierced, lead- (“PädNFL”; “Pädiatrisches Notfalllineal”;

ric emergency departments.

ing to serious damage or even re- www.notfalllineal.de) was used during

quiring amputation of the lower leg treatment of “real” prehospital paediat-

[44]. Instead, suitable manual needles Because suitable doses have to be cal- ric emergencies: nine out of ten severe

need to be provisioned. The authors culated on an individual basis, mistakes dosing errors (> 300% of the recom-

have had very good experience using such as misplacing the decimal point can mended dose) of all drugs studied were

18 g butterfly needles in these situations, lead to results which are off by an order avoided [52]. With regard to adrenaline,

as is also recommended elsewhere of magnitude. Whilst typical doses feel which was overdosed by more than

[45]. They can easily be gripped by the familiar when treating adults, the wide 300% of the recommended dose in all

wings, are very sharp and have a tube range of paediatric patients – ranging from cases where the PädNFL was not used,

attached, simplifying the use. infants to youths – precludes familiarity no mistakes were made when using the

For on-off administration of sedatives with correct doses. Even doses off by an PädNFL.

and analgesics, the intranasal route us- order of magnitude can be serviced from Body weight is a deciding factor for drug

ing an atomiser (“mucosal atomization a single ampoule, making recognition administration and must, as such, be

device” – MAD) is an option. The intense of the error less likely. Because prehos taken into meticulous consideration. In

vascularisation of the nasal mucosa and pital care is neither rendered in a spe- a prehospital analysis in Germany only

the close proximity to the brain lead to a cialised environment, nor by specialised 0.5% of emergency physicians’ records

rapid onset of action comparable with personnel [6], significantly increased specified the weight of the child [52].

that following intravenous administra- error rates are incurred. A study in the If the parents can give the weight of

tion. USA showed that adrenaline was ad- the child, that weight should be used.

ministered incorrectly 60% of the time, When the weight is unknown however,

Owing to venous drainage avoiding and that the average overdose was 808% estimates based on age are unhelpful

liver passage, first-pass metabolism of the recommended 10 µg/kg BW and weight should be estimated based

does not occur following nasal ad- dose [46]. Whilst it is not known from on length.32 Review Articles Medical Education

Team communication is pivotal. Regard- lymphadenopathy in the context of ing external signs (such as bruising or

less of any hierarchy, all those involved infection, and unexplained events are neurological symptoms). For this reason,

must check every order in its entirety described below. serious trauma requires neurocranial

(weight of the child, desired dose per imaging, preferably in a paediatric

Trauma

kg BW, calculated dose and quantity to radiology department. Prior to fusion

be administered) and acknowledge it by Most injuries are isolated to a single ex- of the fontanelles, ultrasound is a rapid,

repeating the entire order before a drug tremity. The same basic principles used radiation-free imaging tool, while all

is administered [53]. When 1 ml syringes in adult trauma care should be applied, other children with a score of < 12 on

with a 0.01 ml scale are used, dilution adequate analgesia provided, and the the Paediatric Glasgow Coma Scale

can be avoided for most drugs so long injury stabilised carefully. Using sup- should undergo computed tomography

as administration is followed by flushing positories in an emergency situation is (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging

with NaCl 0.9%. Every emergency unlikely to provide a rapid and adequate (MRI). Bony injuries are better seen

physician should have paediatric phar- effect. Instead, administering opioids on CT, whilst brainstem injuries and

macologic information (e.g. age-specific such as fentanyl via a nasal atomiser [54] haemorrhage are better represented on

contraindications and doses) at their or using one of the alternatives set out in MRI. Subgaleal haemorrhage represents

disposal on scene, e.g. in the shape of a Table 4 [55] is well suited. a special type of head injury which

tabular compilation or pocketbook. does not occur in adults, and which

As a rule, care for children with mul- involves haemorrhage between the scalp

Common paediatric disorders tiple trauma follows the same basic and the calvaria. As the haematoma may

Preliminary remarks principles which apply to adult care spread around the whole head, blood

[56]. loss may become life-threatening and

must be recognised as such, triggering

The three most common prehospital

blood transfusion if required. External

paediatric disorders, each account-

Owing to their proportions and skeletal compression is not helpful, and obsolete

ing for approximately a third of cas-

development, however, up to 90% in the case of open fontanelles. Those

es, are injuries, respiratory disorders

of children with serious injuries also providing prehospital care should be

and seizures.

have head injuries, while the chest and aware of subgaleal haemorrhage and

abdomen are less commonly affected include assessment for this injury in their

In addition to these three, intussuscep- when compared with adults. It is note trauma evaluation, which would other-

tion (which does not occur in adults), worthy that children may regularly suffer wise be comparable with an appropriate

abdominal pain caused by systemic serious intracranial injury without show- adult routine. In contrast, pelvic fractures

leading to significant blood loss do not

occur in toddlers.

Table 4

Examples of suitable prehospital emergency analgesia. Respiratory emergencies

Asthma

Drug, mode of delivery Dose, Dosing interval

Sudden occurrence of dyspnoea with an

Piritramide (e.g. Dipidolor)

• IV 0.05 – 0.1 mg/kg BW initial bolus expiratory stridor and prolonged expira-

0.025 mg/kg BW every 5 min until pain free tion should bring a diagnosis of asthma

Morphine to mind. In addition to auscultation,

• IV 0.05 – 0.1 mg/kg BW initial bolus the smaller the child, the more helpful

0.025 mg/kg BW every 5 min until pain free laying hands on the chest can be – bron-

Fentanyl (ampoules containing 50 µg/ml) chospasm, secretions, consolidation and

• IV 1 – 2 µg/kg BW initial bolus the breathing pattern can all be felt and

0.25 µg/kg BW every 5 min until pain free

• intranasal using MAD 1.5 µg/kg BW (0.03 ml/kg BW) localised. Therapeutic measures (Tab.

5) don’t differ from those employed in

Esketamine (e.g. Ketanest S, ampoules

containing 5 mg/ml or 25 mg/ml) adults [7], and inhaled therapies don’t

• rectal 10 mg/kg BW require age-based dose adjustment.

• IV 0.5 – 1 mg/kg BW

• intranasal using MAD 2 mg/kg KG Croup syndrome (stenosing laryngo

Ketamine (e.g. Ketamin, ampoules tracheitis)

containing 10 mg/ml or 50 mg/ml) Sudden occurrence of an inspiratory

• rectal 15 – 20 mg/kg BW

stridor together with a barking cough

• IV 1 – 2 mg/kg BW

• intranasal using MAD 4 mg/kg BW is usually caused by Croup syndrome

which generally arises in conjunction

MAD: mucosal atomization device (nasal atomiser).

with viral infections, but which may Medical Education Review Articles 33

Table 5 a smooth surface in a restive situation.

Pharmacological treatment for asthma attacks (from [7]). Initially, the foreign body enters the

trachea, causing an impressive bout of

Nebulised treatment coughing, expelling the foreign object.

Epinephrine (e.g. Infectokrupp®) up to 10 kg BW: 1 ml + 1 ml NaCl 0.9 % If instead the foreign body reaches the

(= 4 mg) from 10 kg BW: 2 ml undiluted (= 8 mg) bronchial system, the child’s condition

Salbutamol nebuliser solution (e.g. Sultanol® 5 – 10 drops (= 1.25 – 2.5 mg) will commonly improve [57]. However,

sol.) (1 drop per year or 3 kg BW, minimum 3,

in the course of things, the object may

maximum 10 drops) in 2 ml NaCl 0.9%

dislocate into the trachea causing a

Ipratropium bromide solution (z. B. Atrovent® 5 – 10 pumps (= 0.125 – 0.25 mg)

life-threatening situation. As such,

sol.) Dose as for salbutamol, in 2 ml NaCl 0.9%

following aspiration, children should

Inhalation using a spacer

always present to a competent hospital

Salbutamol (e.g. Sultanol®) 1 – 2 puffs (0.1 – 0.2 mg) where any suspicion of aspiration should

Fenoterol (e.g. Berotec®) 1 – 2 puffs (0.1 – 0.2 mg) be investigated by bronchoscopy. Chest

Terbutaline (e.g. Bricanyl®) 1 – 2 puffs (0.25 – 0.5 mg) radiographs on the other hand do not

Corticoids provide any helpful information [57].

Methylprednisolone (e.g. Urbason®) 2 – 4 mg/kg BW IV In the case of an unconscious child, the

Prednisolone (e.g. Decortin H , Solu

®

2 – 10 mg/kg BW IV oral cavity must be inspected and swept

Decortin®) without delay, followed immediately by

Prednisone (e.g. Decortin®, Rectodelt®) 5 – 10 mg/kg BW (usually 100 mg) per rectum measures as set out in the resuscitation

β2 mimetics IM

guidelines. These describe in detail the

measures to be taken in case of foreign

e.g. Epinephrine or Terbutaline 10 µg/kg BW (max. 300 µg)

body aspiration (including, amongst

Additional Options

other things, the Heimlich manoeuvre

Magnesium, Ketamine, Theophylline and back blows) [6]. The oral cavity

should be inspected using a laryngo-

scope as soon as possible, removing any

occur spontaneously, and which in ever, unlike Croup syndrome, children visible foreign objects. If the condition

turn is caused by subglottic swelling of with epiglottitis show signs of serious does not improve, the child should be

mucous membranes. Croup is seldom bacterial infection including high fever intubated. If ventilation is not possible

threatening and can be treated in an and notable poor general condition. via the correctly situated tube, attempts

equivalent fashion to asthma. The differ- Preclinical intubation should only be should be made to push the foreign body

ential diagnoses include tracheitis and attempted in dire straits and can be into one or the other main bronchus

epiglottitis (see below), both of which extremely problematic in the presence by intentional deep insertion of the

can be differentiated from Croup by a of purulent swelling of the epiglottis. The tube, following which ventilation of the

prolonged progressing course and high receiving hospital should be informed unrestricted lung should be performed

fever. In unvaccinated children espe- of the suspected diagnosis as early as after retracting the tube into the trachea.

cially, hoarseness, inspiratory stridor and possible so as to be able to have an ex- If the aforementioned measures are not

a barking cough – which can typically perienced team available for the patient successful, success is not to be expected

be triggered by applying pressure on on arrival. Tracheitis, which cannot be and the child should be transferred to

the tongue using a spatula – progressing differentiated from epiglottis clinically, hospital undergoing ongoing resusci-

over days may indicate diphtheria, a has become the most common form of tation, where the foreign body can be

disease once referred to as “real Croup”. life-threatening respiratory tract infec- removed from the trachea.

tion. The diagnosis can only be made by Seizures

Epiglottitis, Tracheitis

bronchoscopy. As a rule, these children Although seizures in children are usually

Since the introduction of the Haemophi-

can be intubated without difficulty; even febrile, other possible causes must be

lus influenza B vaccination, epiglottitis

so, intubation should be performed considered:

has become extremely rare, but does still

using a fibreoptic scope, taking samples • hypoglycaemia

occur because not all parents go through

and ensuring precise placement of the • intoxication

with recommended vaccinations – but

tube at the same time. • head injury

also because other pathogens can be

causative. The clinical picture seen Foreign body aspiration Meningitis must be excluded in infants

in epiglottitis is similar to that seen in Foreign body aspiration typically occurs suffering a febrile seizure without an

croup syndrome and is characterised by when a playing child inserts something obvious focus of infection. Repeated

inspiratory stridor and coughing. How- into their mouth or eats something with application of rectal drugs, which are34 Review Articles Medical Education

difficult to control and have a delayed risk of necrosis of the affected portions rare. Adherence to guideline-recom-

onset of action, can cause overdose and of the intestines when untreated. The mended treatment of BRUE requires the

respiratory depression. As such, the use diagnosis is made using sonography and emergency services to present children

of drugs and routes of administration set treatment by reduction of intussuscep- for treatment by a consultant paedi-

out in Table 6, leading to a rapid onset tion by insufflation of air or fluid can be atrician at a children’s hospital [58].

of action, would seem better suited [7]. provided by the radiology department of Following thorough examination by the

any paediatric hospital. paediatrician, immediate discharge from

Abdominal lymphadenopathy and

Unexplained events hospital may be justified.

intussusception

Regardless of the focus of infection, Emergency services are regularly con- The role of parents during emer-

toddlers regularly suffer swelling of fronted with reports of events perceived

gency care

the abdominal lymph nodes, causing to be life-threatening, whilst the elicited

abdominal pain. This can lead to an history doesn’t provide for clear-cut Presence of parents

erroneous diagnosis of an abdominal deductions and the child presents itself

disorder, which in turn can sometimes in good health. Formerly an apparent Whenever possible, parents should

even culminate in unwarranted surgery. life-threatening event (ALTE), this have the opportunity to be present

expression has been replaced by the during treatment of their children.

term brief resolved unexplained event

Children complaining of abdominal

(BRUE). This nomenclature was chosen

pain must always be investigated for On one hand, parents are generally well

so as to include events which had

a focus of infection outside the ab- informed of the past medical history of

not been interpreted as life-threatening.

domen, e.g. by auscultation of the their child, can tell the precise weight

Despite this, the term still defines a

lungs and inspection of the tympanic and offer the only possibility to elicit a

condition involving a change in

membranes. history. On the other hand, it has been

• muscle tone

shown time and again that relevant

• skin colour

• consciousness psychopathologies are significantly less

The swollen abdominal lymph nodes

• and/or breathing. common in parents who were present

may, however, actually cause a real

for at least some of the treatment of their

abdominal emergency, namely intus- A working diagnosis of BRUE is only child, even when the child died. As such,

susception. This usually occurs at the permissible if a detailed history and

the resuscitation guidelines recommend

ileocecal junction and involves parts of examination by a paediatrician shows

parents should be given the opportunity

the intestine folding into one another, no further irregularities. Colloquially, the

to be present during treatment of their

typically triggering abrupt, severe spas- term “unexplained event” is often used.

child, so long as their presence does not

modic pain. Bloody diarrhoea may also Generally speaking, these events have a

impact on the quality of medical care

occur. Spontaneous reduction of intus- multitude of possible causes, including

[6].

susception can occur, although delaying gastroesophageal reflux, seizures and

treatment whilst hoping for spontaneous upper respiratory tract infections. Cardi- Child abuse and neglect

resolution is not permissible as there is a opulmonary causes, however, are very It should not be overlooked, however,

that parents may play a role in or be

the cause of the illness or injury. Parents

Table 6

smoking at home, for example, may be

Pharmacological treatment for seizures.

the sole cause of asthma in their child.

Sublingual tablets To an often underestimated degree,

Lorazepam (e.g. Tavor® Expidet®) < 0.05 mg/kg BW administered as a sublingual children may be the victims of violence

tablet or neglect. The most recent available

Intranasal administration figures show an incidence of 10 – 15%

Midazolam* (e.g. Buccolam®, Dormicum®) 0.2 mg/kg BW (maximum 10 mg) in Germany, although a significant dark

figure has to be assumed. A review article

Lorazepam (e.g. Tavor® pro injectione) 0.1 mg/kg BW (maximum 4 mg)

looking at head injuries in children

Intravenous drug administration

determined that a quarter of all injuries

Clonazepam (e.g. Rivotril®) 0.05 – 0.1 mg/kg BW IV (max. 2 mg) in children under 2 years of age were

Midazolam (e.g. Dormicum®) 0.1 – 0.2 mg/kg BW IV or intranasal inflicted by others [59]. Recognising

Diazepam (e.g. Valium®) 0.05 – 0.2 mg/kg BW IV abuse gains particular importance with

Thiopental (e.g. Trapanal®) 1 mg/kg BW IV the knowledge that violence and abuse

are commonly not single occurrences

* midazolam solutions for IV administration cause smarting when administered intranasally.

but rather not only repeat themselves Medical Education Review Articles 35

but escalate. This does not mean that Epistry-Cardiac Arrest. Circulation 19. Navsa N, Tossel G, Boon JM: Dimensions

the worst should always be assumed of 2009;119:1484–1491 of the neonatal cricothyroid membrane –

parents or that forensic aspects should 10. Wyllie J, Bruinenberg J, Roehr CC, how feasible is a surgical cricothyroidot-

Rüdiger M, Trevisanuto D, Urlesberger omy? Paediatr Anaesth 2005;15:402–406

dictate treatment. Nevertheless, simple

B: European Resuscitation Council 20. Johansen K, Holm-Knudsen RJ, Charabi

attentive observation and recording

Guidelines for Resuscitation 2015. B, Kristensen MS, Rasmussen LS: Cannot

of attendant circumstances can offer a Section 7. Resuscitation and support of ventilate-cannot intubate an infant: surgi-

chance to free the child from a spiral of transition of babies at birth. Resuscitation cal tracheotomy or transtracheal cannu-

abuse through a process managed by a 2015;95:249–263 la? Paediatr Anaesth 2010;20:987–993

family court after completion of medical 11. Wyckoff MH, Aziz K, Escobedo MB, 21. Holm-Knudsen RJ, Rasmussen LS,

care (further reading regarding the legal Kapadia VS, Kattwinkel J, Perlman JM, Charabi B, Bøttger M, Kristensen MS:

framework and suitable course of action et al: Part 13: Neonatal Resuscitation: Emergency airway access in children –

is provided by [60]). 2015 American Heart Association transtracheal cannulas and tracheotomy

Guidelines Update for Cardiopulmonary assessed in a porcine model. Pediatric

Resuscitation and Emergency Anesthesia 2012;22:1159–1165

References Cardiovascular Care. Circulation 22. Hoffmann F, Keil J, Urban B, Jung P,

2015;132:S543–560 Eich C, Schiele A, et al: Interdisziplinär

1. Eich C, Roessler M, Nemeth M, konsentierte Stellungnahme:

12. Hupfl M, Selig HF, Nagele P: Chest-

Russo SG, Heuer JF, Timmermann Atemwegsmanagement mit supra-

compression-only versus standard

A: Characteristics and outcome of glottischen Atemwegs hilfen in der

cardiopulmonary resuscitation: a me-

prehospital paediatric tracheal intuba- Kindernotfallmedizin. Larynxmaske ist

ta-analysis. Lancet 2010;376:1552–1557

tion attended by anaesthesia-trained State-of-the-art. Anästh Intensivmed

emergency physicians. Resuscitation 13. Kitamura T, Iwami T, Kawamura T,

Nagao K, Tanaka H, Nadkarni VM, 2016;57:377–386

2009;80:1371–1377

et al: Conventional and chest-com- 23. Chambers IR, Jones PA, Lo TY, Forsyth

2. Zink W, Bernhard M, Keul W, Martin E, RJ, Fulton B, Andrews PJ, et al: Critical

pression-only cardiopulmonary

Volkl A, Gries A: Invasive techniques in

resuscitation by bystanders for children thresholds of intracranial pressure and

emergency medicine. I. Practice-oriented

who have out-of-hospital cardiac cerebral perfusion pressure related to

training concept to ensure adequately

arrests: a prospective, nationwide, age in paediatric head injury. J Neurol

qualified emergency physicians.

population-based cohort study. Lancet Neurosurg Psychiatry 2006;77:234–240

Anaesthesist 2004;53:1086–1092

2010;375:1347–1354 24. Catala-Temprano A, Claret Teruel G,

3. Lammers R, Byrwa M, Fales W: Root

14. Goto Y, Maeda T, Goto Y: Impact of Cambra Lasaosa FJ, Pons Odena M,

causes of errors in a simulated prehos-

dispatcher-assisted bystander cardiopul- Noguera Julian A, Palomeque Rico

pital pediatric emergency. Acad Emerg

monary resuscitation on neurological A: Intracranial pressure and cerebral

Med 2012;19:37–47

outcomes in children with out-of-hos- perfusion pressure as risk factors in

4. Heimberg E, Heinzel O, Hoffmann F: children with traumatic brain injuries.

Typical problems in pediatric pital cardiac arrests: a prospective,

nationwide, population-based cohort J Neurosurg 2007;106:463–466

emergencies: Possible solutions.

study. J Am Heart Assoc 2014;3:e000499 25. Coté CJ, Lermann J, Todres ID: A practice

Med Klin Intensivmed Notfmed

15. Kerrey BT, Rinderknecht AS, Geis GL, of anesthesia for infants and children.

2015;110:354–359

Nigrovic LE, Mittiga MR: Rapid sequence 4th Edition. Philadelphia: Saunders 2009

5. Bankole S, Asuncion A, Ross S, Aghai Z,

intubation for pediatric emergency 26. Sümpelmann R, Becke K, Brenner S,

Nollah L, Echols H, et al: First responder

patients: higher frequency of failed Breschan C, Eich C, Höhne C et al: S1-

performance in pediatric trauma: a

comparison with an adult cohort. Pediatr attempts and adverse effects found by Leitlinie: Perioperative Infusionstherapie

Crit Care Med 2011;12:e166–170 video review. Ann Emerg Med 2012;60: bei Kindern. Anästh Intensivmed

251–259 2016;57:368–376

6. Maconochie IK, Bingham R, Eich C,

López-Herce J, Rodríguez-Núñez A, 16. Gausche M, Lewis RJ, Stratton SJ, Haynes 27. Osthaus W, Ankermann T, Sümpelmann

Rajka T, et al: European Resuscitation BE, Gunter CS, Goodrich SM, et al: Effect R: Präklinische Flüssigkeitstherapie

Council Guidelines for Resuscitation of out-of-hospital pediatric endotracheal im Kindesalter. Pädiatrie up2date

2015. Section 6. Paediatric life support. intubation on survival and neurological 2013;08:67–84

Resuscitation 2015;95 223–248 outcome: a controlled clinical trial. 28. Duke T: New WHO guidelines on emer-

7. Kaufmann J, Laschat M, Wappler F: Die Jama 2000;283:783–790 gency triage assessment and treatment.

präklinische Versorgung von Notfällen 17. Weiss M, Schmidt J, Eich C, Stelzner J, Lancet 2016;387:721–724

im Kindesalter. Anästh Intensivmed Trieschmann U, Müller-Lobeck L et al: 29. Banner W, Jr., Vernon DD, Minton SD,

2012;53:254–267 Handlungsempfehlung zur Prävention Dean JM: Nonlinear dobutamine phar-

8. Turner NM: Recent developments in und Behandlung des unerwartet schwier- macokinetics in a pediatric population.

neonatal and paediatric emergencies. igen Atemwegs in der Kinderanästhesie. Crit Care Med 1991;19:871–873

Eur J Anaesthesiol 2011;28:471–477 Anästh Intensivmed 2011;52:S54–S63 30. Artman M, Kithas PA, Wike JS, Strada

9. Atkins DL, Everson-Stewart S, Sears GK, 18. Cote CJ, Hartnick CJ: Pediatric transtra- SJ: Inotropic responses change during

Daya M, Osmond MH, Warden CR, et cheal and cricothyrotomy airway devices postnatal maturation in rabbit. Am J

al: Epidemiology and outcomes from for emergency use: which are appro- Physiol 1988;255:H335–342

out-of-hospital cardiac arrest in children: priate for infants and children? Paediatr 31. Papp JG: Autonomic responses and

the Resuscitation Outcomes Consortium Anästh 2009;19 Suppl 1:66–76 neurohumoral control in the human36 Review Articles Medical Education

early antenatal heart. Basic Res Cardiol Refresher Course der DAAF 54. Borland M, Jacobs I, King B, O‘Brien D:

1988;83:2–9 2008;34:193–204 A randomized controlled trial comparing

32. Shukla A, Steven JM, McGowanJr. FX: 43. Fachinformation Akrinor, Firma AWD intranasal fentanyl to intravenous

Cardiac Physiology an Pharmacology. Pharma, Dresden. Stand Juli 2001 morphine for managing acute pain in

In: CJ Coté, J Lerman and ID Todres. A 44. Oesterlie GE, Petersen KK, Knudsen L, children in the emergency department.

practice of anesthesia for infants and Henriksen TB: Crural amputation Ann Emerg Med 2007;49:335–340

children. 4th. Saunders 2009 of a newborn as a consequence of 55. Kaufmann J, Laschat M, Wappler F:

33. Hunt R, Osborn D: Dopamine for intraosseous needle insertion and Analgesie und Narkose im Kindesalter.

prevention of morbidity and mortality calcium infusion. Pediatr Emerg Care Notfallmedizin up2date 2012;7:17–27

in term newborn infants with suspected 2014;30:413–414 56. Kaufmann J: Versorgung des kindlichen

perinatal asphyxia. Cochrane Database 45. Lake W, Emmerson AJ: Use of a butterfly Polytraumas. Anästh Intensivmed

Syst Rev 2002;CD003484 as an intraosseous needle in an oedema- 2010;51:612–614

34. Brissaud O, Botte A, Cambonie G, tous preterm infant. Arch Dis Child Fetal 57. Kaufmann J, Laschat M, Frick U,

Dauger S, de Saint Blanquat L, Durand Neonatal Ed 2003;88:F409 Engelhardt T, Wappler F: Determining the

P, et al: Experts‘ recommendations for 46. Hoyle JD, Davis AT, Putman KK, Trytko probability of a foreign body aspiration

the management of cardiogenic shock in JA, Fales WD: Medication dosing errors from history, symptoms and clinical

children. Ann Intensive Care 2016;6:14 in pediatric patients treated by emergen- findings in children. BJA: British Journal

35. Berner M, Rouge JC, Friedli B: The cy medical services. Prehosp Emerg Care of Anaesthesia 2017;118:626–627

hemodynamic effect of phentolamine 2012;16:59–66 58. Tieder JS, Bonkowsky JL, Etzel RA,

and dobutamine after open-heart 47. Perondi MB, Reis AG, Paiva EF, Nadkarni Franklin WH, Gremse DA, Herman B, et

operations in children: influence of the VM, Berg RA: A comparison of high- al: Brief Resolved Unexplained Events

underlying heart defect. Ann Thorac Surg dose and standard-dose epinephrine in (Formerly Apparent Life-Threatening

1983;35:643–650 children with cardiac arrest. N Engl J Events) and Evaluation of Lower-Risk

36. Dellinger RP, Levy MM, Rhodes A, Med 2004;350:1722–1730 Infants. Pediatrics 2016;137:e1–e32

Annane D, Gerlach H, Opal SM, et al: 48. Kaufmann J, Schieren M, Wappler F: 59. Duhaime AC, Christian CW, Rorke LB,

Surviving sepsis campaign: international Medication errors in paediatric anaesthe- Zimmerman RA: Nonaccidental head

guidelines for management of severe sia-a cultural change is urgently needed! injury in infants – the „shaken-baby

sepsis and septic shock: 2012. Crit Care Br J Anaesth 2018;120:601–603 syndrome“. N Engl J Med 1998;338:

Med 2013;41:580–637 1822–1829

49. Kaufmann J, Wolf AR, Becke K, Laschat

37. Harada K, Tamura M, Ito T, Suzuki M, Wappler F, Engelhardt T: Drug safety 60. Jacobi G, Dettmeyer R, Banaschak S,

T, Takada G: Effects of low-dose in paediatric anaesthesia. Br J Anaesth Brosig B, Herrmann B: Misshandlung

dobutamine on left ventricular diastolic 2017;118:670–679 und Vernachlässigung von Kindern –

filling in children. Pediatr Cardiol Diagnose und Vorgehen. Dtsch Arztebl

50. Kaufmann J, Laschat M, Wappler F:

1996;17:220–225 Int 2010;107:231–239.

Medikamentenfehler bei Kindernotfällen

38. Havel C, Arrich J, Losert H, Gamper G, – eine systematische Analyse. Dtsch

Mullner M, Herkner H: Vasopressors for Arztebl Int 2012;109:609–616

hypotensive shock. Cochrane Database 51. Bernius M, Thibodeau B, Jones A,

Syst Rev 2011;CD003709 Clothier B, Witting M: Prevention of

39. Lampard JG, Lang E: Vasopressors for

Correspondence

pediatric drug calculation errors by

hypotensive shock. Ann Emerg Med prehospital care providers. Prehosp address

2013;61:351–352 Emerg Care 2008;12:486–494

40. Sakr Y, Reinhart K, Vincent JL, Sprung 52. Kaufmann J, Roth B, Engelhardt T,

CL, Moreno R, Ranieri VM, et al: Does Lechleuthner A, Laschat M, Hadamitzky Jost Kaufmann

dopamine administration in shock C, et al: Development and Prospective MD, PhD

influence outcome? Results of the Sepsis Federal State-Wide Evaluation of

Occurrence in Acutely Ill Patients (SOAP)

Kinderkrankenhaus der Kliniken der

a Device for Height-Based Dose

Study. Crit Care Med 2006;34:589–597 Recommendations in Prehospital

Stadt Köln gGmbH

41. Stopfkuchen H, Racke K, Schworer H, Pediatric Emergencies: A Simple Tool Amsterdamer Straße 59

Queisser-Luft A, Vogel K: Effects of dopa- to Prevent Most Severe Drug Errors. 50735 Köln, Germany

mine infusion on plasma catecholamines Prehosp Emerg Care 2018;22:252–259 Phone: +49 0221 8907 15199

in preterm and term newborn infants. 53. Kaufmann J, Becke K, Höhne C, Eich C, Fax: +49 0221 8907 5264

Eur J Pediatr 1991;150:503–506 Goeters C, Güß T et al: S2e-Leitlinie

42. Emmel M, Roesner D, Roth B: – Medikamentensicherheit in der Mail: jost.kaufmann@uni-wh.de

Hypovolämischer Schock – Kinderanästhesie. Anästh Intensivmed ORCID-ID: 0000-0002-5289-6465

Besonderheiten des Kindesalters. 2017;58:105–118You can also read