Gazeta - Taube Philanthropies

←

→

Page content transcription

If your browser does not render page correctly, please read the page content below

Gazeta Volume 28, No. 2

Spring/Summer 2021

Wilhelm Sasnal, First of January (Side),

2021, oil on canvas.

Courtesy of the artist and Foksal

Gallery Foundation, Warsaw

A quarterly publication of

the American Association

for Polish-Jewish Studies

and Taube Foundation for

Jewish Life & CultureEditorial & Design: Tressa Berman, Daniel Blokh, Fay Bussgang, Julian Bussgang, Shana Penn, Antony Polonsky, Aleksandra Sajdak,

William Zeisel, LaserCom Design, and Taube Center for Jewish Life and Learning

CONTENTS

Message from Irene Pipes ................................................................................................ 4

Message from Tad Taube and Shana Penn .................................................................... 5

FEATURES

Lucy S. Dawidowicz, Diaspora Nationalist and Holocaust Historian ............................ 6

From Captured State to Captive Mind: On the Politics of Mis-Memory

Tomasz Tadeusz Koncewicz ................................................................................................. 12

EXHIBITIONS

New Legacy Gallery at POLIN Museum of the History of Polish Jews

Barbara Kirshenblatt-Gimblett

Tamara Sztyma ..................................................................................................................... 16

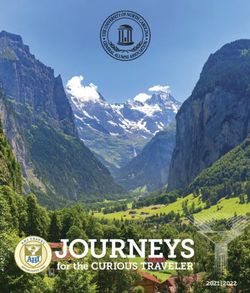

Wilhelm Sasnal: Such a Landscape. Exhibition at POLIN Museum ............................ 20

Sweet Home Sweet. Exhibition at Galicia Jewish Museum

Jakub Nowakowski ............................................................................................................... 21

A Grandson’s Reflection on Sweet Home Sweet

Adam Schorin ....................................................................................................................... 24

REPORTS

Kraków to Stop the Sale of “Lucky Jews”

Magda Rubenfeld Koralewska ................................................................................................ 25

Changes in Governance at the Auschwitz-Birkenau State Museum

Antony Polonsky ................................................................................................................... 27

CONFERENCES

History of the Jewish Workers’ Alliance—the Bund

Antony Polonsky ................................................................................................................... 28

Symposium in Honor of Professor Antony Polonsky

Michael Fleming, François Guesnet, and Christine Schmidt ...................................................... 30

“What’s New, What’s Next?” Online Conference at POLIN Museum .......................... 32

International Association of Jewish Genealogical Societies (IAJGS) ......................... 33

“Restoring Jewish Cemeteries of Poland” ..................................................................... 33

ANNOUNCEMENTS

BOOKS

Warsaw Ghetto Police: The Jewish Order Service during the Nazi Occupation.

By Katarzyna Person ..................................................................................................... 34

Islands of Memory. By Jolanta Ambrosewicz-Jacobs ............................................... 35

The Stage as a Temporary Home. By Diego Rotman ................................................ 35

The Rebellion of the Daughters. By Rachel Manekin ................................................ 36

2 n GAZETA VOLUME 28, NO. 2Hasidism, Suffering and Renewal: The Prewar and Holocaust Legacy

of Rabbi Kalonymus Shapira. Edited by Don Seeman, Daniel Reiser, and

Ariel Evan Mayse ........................................................................................................... 36

The Touch of an Angel. By Henryk Schönker ............................................................. 37

Tale of a Niggun. By Elie Wiesel .................................................................................. 37

The Towns of Death: The Pogroms of Jews by Their Neighbors.

By Mirosław Tryczyk ...................................................................................................... 38

Ashkenazi Herbalism. By Deatra Cohen and Adam Siegel ...................................... 38

The August Trials: The Holocaust and Postwar Justice in Poland

By Andrew Kornbluth .................................................................................................... 39

Philo-Semitic Violence: Poland’s Jewish Past in New Polish Narratives

By Elżbieta Janicka and Tomasz Żukowski ................................................................ 39

AWARDS

Barbara Engelking Receives 2021 Irena Sendler Memorial Award .......................... 40

Jósef Hen Receives Lifetime Achievement Award ..................................................... 41

IN BRIEF

Stanford Libraries Receives International Military Tribunal

Nuremberg Trial Archives ...................................................................................... 42

Jewish Historical Institute Dedicates Jan Jagielski Heritage

Documentation Department ......................................................................................... 43

GEOP Announcements ................................................................................................. 44

New Foundation to Support LGBTQ+ Communities in Poland ................................. 46

OF SPECIAL INTEREST

The Rediscovered Caricature Art of J.D. Kirszenbaum-Duvdivani

Nathan Diament .................................................................................................................... 47

POEM

The Tale of a Niggun (Excerpt)

Elie Wiesel ........................................................................................................................... 49

OBITUARIES

Roman Kent

Antony Polonsky ................................................................................................................... 50

Jan Jagielski

Emanuel Ringelblum Jewish Historical Institute ........................................................................ 53

Faye Schulman

Tressa Berman ..................................................................................................................... 54

Marek Web

Joanna Lisek ........................................................................................................................ 56

Jewlia Eisenberg

Naomi Seidman .................................................................................................................... 57

Teresa Żabińska-Zawadzki .............................................................................................. 59

SPRING/SUMMER 2021 n 3President, American Association

Message from for Polish-Jewish Studies

Irene Pipes Founder of Gazeta

Dear Friends,

Greetings from Cambridge, Massachusetts. I am very happy that the POLIN

Museum in Warsaw is again open and very much hope to be able to visit it in

the near future.

We have continued to take advantage of the wonders of technology to carry on

our important work. In my last message I described the opening of the Legacy

gallery at POLIN Museum which honors Polish Jews who have made a major

contribution to the life of Poland and the wider world. A series of online events has

marked its opening. Among these are the series of interviews “Meet the Family”

Irene Pipes

in which Barbara Kirshenblatt-Gimblett, Ronald S. Lauder Chief Curator of the

Core Exhibition at the Museum, discussed the lives of prominent Polish Jews with

members of their families.

Antony Polonsky, Chief Historian of the Global Education Outreach Program of POLIN Museum, has

organized a series of online discussions of recent books on the history of Jews in Poland, intended to

lead up to the international conference “What’s New, What’s Next? Innovative Methods, New Sources,

and Paradigm Shifts in Jewish Studies” to be held at POLIN this October. Among the most recent books

to be discussed are Nancy Sinkoff’s, Lucy S. Dawidowicz, the New York Intellectuals, and the Politics

of Jewish History (featured in this issue in an interview conducted by Professor Samuel Kassow),

Jeffrey Shandler’s Yiddish: Biography of a Language, and others.

One notable event also described in this issue was the online symposium held in honor of Professor Antony

Polonsky on the occasion of his eightieth birthday. Its theme was “The Holocaust in Eastern Europe:

Sources, Memory, Politics,” and it brought together established and junior scholars to review the state of

knowledge on this complex and disputed topic. The importance of this sort of exchange is made clear by

Tomasz Tadeusz Kuncewicz’s article, which clearly shows the complexities of history and memory to meet

the challenges that face Poland today.

I hope you are all well and that we shall soon be able to meet in person.

With best wishes,

Irene Pipes

President

4 n GAZETA VOLUME 28, NO. 2Message from

Chairman and Executive Director,

Tad Taube and Taube Foundation for Jewish Life

& Culture

Shana Penn

Two of our lead stories in this issue of Gazeta address a very serious issue:

intolerance and its impact on Jewish communities from the end of World War

I until today. Our first story is an interview conducted by Samuel Kassow

with Nancy Sinkoff, the biographer of Lucy Dawidowicz, arguably one of the

most influential Jewish writers since World War II. In her most famous book,

The War Against the Jews, Dawidowicz argued that anti-Semitism was the

driving force in Hitler’s worldview and an essential part of his European war.

She also argued that Poles themselves had a strong anti-Semitic streak, as she

witnessed first-hand on a visit to Vilna in 1938.

Tad Taube

Sinkoff concludes her interview with questions that Davidowicz’s writings

pose for today’s readers. “How do we understand the penetration of

intolerance in a society? Who’s responsible for it?”

These are exactly the kind of questions that dominate our second lead story,

by Tomasz Tadeusz Koncewicz, a legal studies scholar from Poland known

for his human rights scholarship and advocacy. His article focuses on the

current Polish government’s efforts to define Poles and Poland in a way that

imposes a single national narrative. Unfortunately, explains Koncewicz,

that ultranationalist narrative discourages, even punishes, the unbiased

examination of Poland’s complicated and often painful history, including

the relations between gentiles and Jews. To Sinkoff’s query of “Who’s

Shana Penn

responsible” for the “penetration of intolerance in a society?” Koncewicz

has a direct and sobering answer.

Both of our lead stories urge the importance of maintaining an open and

objective public and scholarly dialogue as a way of curbing intolerance. And

this, in turn, flourishes best in a democratic nation animated by civility and

the freedom to speak frankly about truth and justice. We hope you will find

that this issue of Gazeta helps to advance this critical discussion.

Tad Taube and Shana Penn

Chairman and Executive Director

SPRING/SUMMER 2021 n 5FEATURE ARTICLES

Lucy S. Dawidowicz (1915–90), Diaspora Nationalist and

Holocaust Historian

Samuel Kassow Interviews Nancy Sinkoff About Her Award-Winning Book

E ditors’ Note: This

interview has been

adapted from a conversation

Polish Republic, to spend a

year as a research fellow at the

YIVO Institute. She returned

between Professors to New York during the war

NancySinkoff and Samuel years, working closely with

Kassow on Sinkoff’s award- refugee scholars. She went

winning book, From Left to back to Europe, to post-war

Right: Lucy S. Dawidowicz, occupied Germany, in both

The New York Intellectuals the American and the British

and the Politics of Jewish zones. After fifteen months

History (Wayne State in two very different areas of

University Press, 2020). the occupation, she returned

Sinkoff and Kassow spoke to New York. She quite

on the webinar series literally was transnational

Encounters, co-hosted by the in her peregrinations.

University of Massachusetts Intellectually, she connected

the Jews.’” What does that

Amherst’s Institute for the US diasporic experience

mean, and how does the

Holocaust, Genocide, and back to Europe. She also

approach relate to her diaspora

Memory Studies, and the connected what I call the

nationalism and to the

Avraham Harman Research long Jewish past in European

traditions of Jewish historical

Institute of Contemporary historiography to the post-war

writing that preceded her in

Jewry at the Hebrew American Jewish experience.

Europe?

University of Jerusalem.

The book covers all these

See the full interview at: Sinkoff: Lucy Dawidowicz

subjects and is sensitive

https://www.youtube.com/ embodies transnationalism.

to the long Jewish past,

watch?v=gdvwgrpiW_Q. She was an American-born

Dawidowicz’s present

immigrant daughter raised

Kassow: Congratulations, in an intensely Jewish

moment, and the context,

Nancy Sinkoff, on a wonderful namely, the worlds of Yiddish

environment in inter-war

book. Your book claims that scholarship, American Jewish

New York City. In 1938, she

Dawidowicz argues “Jewish politics, and the transnational

made a fateful decision to

history must be written with connections that she—and

go to Vilna, then within the

Ahavat Yisrael, ‘love of I—would argue exist among

boundaries of the Second

6 n GAZETA VOLUME 28, NO. 2Jews. She saw herself as Kassow: Can you discuss

deeply connected to this her main contributions to

entity called the transnational the history of the Holocaust?

Jewish people. How do they stand up today,

forty-five years after the

Dawidowicz was informed

publication of The War

by the ideology known as

Against the Jews?

“diaspora nationalism,” or

diaspora national identity, Sinkoff: Dawidowicz was

which insists on the not Lucy Dawidowicz

peoplehood of the Jews. The until January 1948. Born

people themselves are the in 1915, her name was

motor of their history. Their Lucy Schildkret, or Libe in

religion, ideology, and politics Yiddish. In December 1947,

all derive from their existence Professor Nancy Sinkoff. she returned to the United

as a nation, which embodies a Nan Melville. Used with permission States, and at age thirty-three,

sense of belonging to a people after her two sojourns in

[Dawidowicz] connected

with a long historic past. Europe, she married Szymon

She was educated in diaspora what I call the long Dawidowicz, a refugee from

nationalist institutions. Warsaw who immigrated

Jewish past in European

Starting in childhood, she to New York before the

wrote in Yiddish, studied historiography to the Holocaust but lost his wife

Yiddish literature, and many and children in the Warsaw

post-war American

of her teachers were great Ghetto. They had a wonderful

Polish Jewish historians. Jewish experience. marriage. They did not have

children, but she got a Polish

Her diaspora nationalism ―Nancy Sinkoff

surname, Dawidowicz.

encouraged her to go to Vilna.

they had come and which

Diaspora nationalism infused Until the publication of the

they cherished.” She was

the Yiddishist ideologues Golden Tradition: Jewish

taught to love Jews and

with ahavat yisra’el/ahaves Life and Thought in Eastern

Jewishness, to relish Jewish

yisroyel (Heb. and Yid. love Europe in 1967, her anthology

experience and creativity.

of the Jewish people). In a of East European Jewish life,

1968 talk, she recalled that her This meant that in her she was relatively unknown.

childhood teachers “wanted perspective the historian of The book that makes her

to transmit what was viable of the Jews should acknowledge famous is the War Against

East European Yiddish culture a commitment to the Jewish the Jews: 1933–1945.

to their children, namely its people and care about it. It It’s still in print, which

ambience, the mood, the spirit, was a form of nationalism is interesting because, in

the values of the internal that privileged the belonging many ways, Dawidowicz

Jewish society from which of the Jews to a people. has been disregarded or is

SPRING/SUMMER 2021 n 7no longer significant to the war against the Jews was a

historians who write on the distinct and deliberate war.

Holocaust. Highly acclaimed The campaign to destroy the

in 1975, it is known for its Jews was already a blueprint

perspective on the causes in Hitler’s mind from the

of the Final Solution. She publication of Mein Kampf.

wrote that Hitler’s ideology That forms the first part of

of anti-Semitism was a her book.

linear steppingstone to the

The second part, “The

destruction of the Jews during

Holocaust,” is about the

the war. That concept is called

Jewish communal response to

“intentionalism.”

the attack. In this regard, the

When the book was re-issued book differs from the works

in 1985, she wrote, “It has that had preceded it in English

been my view, now widely because it emphasizes Jewish

Lucy Schildkret, Hunter College

shared, that hatred of the graduation, 1936.

sources, Jewish historical

Jews was Hitler’s central and Courtesy of Laurie Sapakoff agency, and the Jewish

most compelling belief and collective will to live, which

that it dominated his thoughts the gift that keeps on giving. is a reflection again of her

and actions all his life. The Scholars are still arguing about diaspora nationalism.

documents amply justify this. To what degree was anti-

Semitism the motor of Hitler’s Kassow: Though the book

my conclusion that Hitler

ideology? Can modern anti- has been superseded by other

planned to murder the Jews

Semitism be linked to earlier research, her discussion of

in coordination with his plans

forms of anti-Jewish hatred? the Jews—especially of the

to go to war for Lebensraum

How influential was it among ghettos—brought the attention

(living space) and to establish

the masses of German soldiers? of the wider public to the fact

the Thousand Year Reich. The

How important are ideas in that the ghettos were Jewish

conventional war of conquest

shaping historical change? communities and were worthy

was to be waged parallel to,

How important are “great men of study. Outside of Israel,

and was able to camouflage,

in history”? How important are the ghettos were not being

the ideological war against the

structures of society, socio- studied, they were regarded

Jews. In the end, as the war

economics, happenstance, as holding pens for the death

hurtled to its disastrous finale,

idiosyncrasy, etc.? camps. One issue that stands

Hitler’s relentless fanaticism

out is Poland. Can you discuss

in the racial ideological war Dawidowicz’s statement that her analysis of Poland, Polish-

ultimately cost him victory in her views were widely shared Jewish relations in the inter-

the conventional war.” is not true, but it represents war period especially, and the

Among historians of the her position that, in contrast war period? Other historians,

Holocaust, this paragraph is to conventional war, the such as Celia Heller, whose

8 n GAZETA VOLUME 28, NO. 2book was entitled On the Edge system. Her view of Eastern

of Destruction: Jews of Poland Europe was decisively shaped

between the Two World Wars, by her anti-communism.

saw Poland as inexorably

Regarding the inter-war years,

anti-Semitic and Jewish life as

when Dawidowicz arrived in

doomed from the onset of the

Poland in 1938, she’s already

Polish state’s independence

reading about Nazism and

after World War I. How did

fascism. The Yiddish press

Dawidowicz evaluate those

reports the discrimination

years in her memoir From That

against Polish Jews. Still, it

Place and Time?

was better to be a Polish Jew

Sinkoff: There are two parts in inter-war Poland than it

to your question. First, what was to be a German Jew after

is the “reality” of Polish- the rise of Nazism. There

Jewish relations in the inter- were no Nuremberg Laws in

war years? Second, how does Poland, even if anti-Semitism

Dawidowicz remember that Lucy Schildkret in Vilna, August 1939. increased after the military

Courtesy of Laurie Sapakoff

when she writes her memoir hero Józef Piłsudski died in

in 1989–90? The memoir is 1935. Before that, anti-Jewish

How do we understand

a late-in-life reflection on actions were present but were

the important years of being the penetration of not instrumentalized through

in Europe, returning to New the state, unlike in Nazi

intolerance in a society?

York, and the destruction of Germany.

Ashkenazi Jewish civilization. Who’s responsible for

Dawidowicz arrives in 1938,

The book is poignant and

it? I think the issues which we now know was the

written with a great sense

beginning of the end. The

of loss. raised during Lucy S.

drums of war are beating

Lucy Dawidowicz is living Dawidowicz’s life will hard. She’s well aware

in the Cold War period. She of anti-Jewish hatred and

speak to people today.

looked at Eastern Europe predations on the street and

through the lens of the Cold ―Nancy Sinkoff in the university. But in 1938,

War and the destruction of no one knew about Zyklon

Jewish particularism, of underground in those societies. B gassings. The Celia Heller

autonomous Jewish culture It was difficult to be publicly perspective, that Jews lived

in the Soviet Union and in involved with autonomous on the edge of destruction,

communist Poland. Jewish culture in Eastern gives you the false sense

Europe. We knew later that that Jews woke up in August

She didn’t have full access there were continuities of 1938 and rent their clothing

to much that was happening Jewish identity under the Soviet in mourning.

SPRING/SUMMER 2021 n 9Lucy Schildkret and Szymon Dawidowicz, 1946.

Courtesy of Laurie Sapakoff

A poignant part of Polish landscape. Jews felt among some historians to say

Dawidowicz’s memoir that way, and they did so in that Polish anti-Semitism has

describes going to see an Yiddish, in Hebrew, and in been greatly exaggerated.

exhibit, Jews in Poland, Polish. The exhibit showed I hope that by spelling out,

that CYSHO (Yid. Tsentral the enormous cultural and in small detail, what really

yidishe shul organizatsye) political vitality. Some Jews happened, my book will help

had prepared on Jewish life left if they could, but Poland to set the record straight.”

in Poland, which opened was their home.

Kassow: While there was

with a map showing Jewish

Dawidowicz, however, increasing anti-Semitism

communal life everywhere.

observed the discrimination, after Piłsudski died, Poland

The Jews were an urban

the anti-Jewish violence, the never passed a version of the

majority in Poland; they were

ghetto benches. Later, in an Nuremberg Laws. Once the

everywhere. This exhibit was

interview, she said—in her Polish pre-war government

to show the doikeyt (Yid.

typical forthright fashion— realized they needed the

“hereness”), the relatedness,

“It’s very fashionable now support of the Western

the belonging of Jews to the

10 n GAZETA VOLUME 28, NO. 2democracies, they had to put Nancy Sinkoff, PhD, is the

on hold many restrictions that Academic Director of the

they had intended to inflict Allen and Joan Bildner Center

on Polish Jews. Many Polish for the Study of Jewish Life

Jews, at the end of the 1930s, and Professor of Jewish

were cautiously hoping for Studies and History at Rutgers

new grounds within Polish University—New Brunswick.

society. Dawidowicz made From 2014 to 2018, she

no effort to learn Polish or to served as Rutgers University’s

really understand the Poles. Director of the Center for

I’m not apologizing for the European Studies.

Poles, but in this I think she

was strident and unable to Samuel D. Kassow, PhD, is

understand some deeper things Charles H. Northam Professor

that were going on within of History at Trinity College,

Polish society. where he specializes in the

Lucy Schildkret in Belsen.

history of Ashkenazi Jewry.

Sinkoff: I agree with your Courtesy of Laurie Sapakoff His groundbreaking book,

comments 100 percent. She Who Will Write Our History?

did not learn Polish. Her and because of the learning was adapted into an award-

husband spoke Polish. One of of languages. What did it winning film in 2018.

the reasons she could never mean for the average peasant

forgive the Poles was deeply hearing a sermon chastising

personal. First, the murder of the Jews versus a functionary

her beloved mentors, Zelig in a bureaucracy? And Jan

and Riva Kalmanovich, Gross put this question on

who were like parents to the map again with his

her. Second, the murder of famous book, Neighbors:

Szymon’s daughter, who The Destruction of the Jewish

was a ghetto fighter. And so, Community in Jedwabne,

she was angry and embittered. Poland, about the murder of

the Jews by their neighbors.

One of the complexities of

studying the relations of locals These are big questions.

to anti-Jewish incitements How do we understand the

is this divide, if you will, penetration of intolerance

between governmental in a society? Who’s

practices and from-the-ground responsible for it? I think

attitudes. That’s part of what the issues raised during Lucy

historians can do because of S. Dawidowicz’s life will

the opening of the archives speak to people today. n

SPRING/SUMMER 2021 n 11From Captured State to Captive Mind: Tomasz Tadeusz

On the Politics of Mis-Memory Koncewicz

I n loving memory of my

late grandmother Czesława

Strąg, a Righteous Among the

the state capture that has

taken place in Poland since

2015. With the judiciary

Nations, who taught me that and public media in tatters,

in order to move forward, we the government is now

must never forget about where implementing what I have

called elsewhere a “politics

we come from.

of mis-memory” that seeks to

Poland, March 2021 present one correct vision of

history for all Poles.

A court’s finding, only

weeks ago, that two Polish Czesława and Maria in 1994. The most dangerous installment

history professors are guilty Family Archives of Tomasz T.Koncewicz. of such politics came with

Used with permission

of defaming an individual the 2018 amendment to

for activities during the the Law on the Institute of

Holocaust, is not just a In a room where people National Remembrance,

case brought to protect the unanimously maintain which criminalized perceived

reputation of a relative. erroneous public statements

Rather, we seem to be entering a conspiracy of silence, which assigned to the Polish

unchartered territory, where nation any blame for crimes

one word of truth sounds

the long arm of the law committed by the Nazi

becomes a method of settling like a pistol shot. invaders. Minister of Justice

scores. In this case, the sacred Zbigniew Ziobro presented

―Czesław Miłosz,

dignity of the Polish nation, Nobel Lecture (1980) the rationale as follows. The

hidden under the argument of Polish government, he said,

protecting the “good name” done and, ultimately, are we “took an important step in the

of a person, overshadows ready to face it now, if ever? direction of creating stronger

the need to have a robust legal instruments allowing us

historical conversation about These questions face Poles to defend our rights, defend

the fate of millions of often today. The defamation suit of the historical truth, and

anonymous victims. Our focus the historians did not happen defend Poland’s good name

on this one case runs the risk in a legal vacuum, nor can everywhere in the world.” He

of obscuring a national debate we claim that we did not see vowed to prosecute all those

about fundamental questions: it coming. Quite the contrary. who defame the Polish nation

Who are we? What have we It follows from the logic of by these means.

12 n GAZETA VOLUME 28, NO. 2Even at its drafting stage, the split perception created “two

law sparked an uproar over moral vocabularies, two sorts

its breathtaking scope and the of reasoning, two different

severity of its sanctions (up pasts. In this circumstance,

to three years’ imprisonment) the uncomfortably confusing

and has been criticized as recollection of things done

yet another example of the by us to others during the

ultranationalist revival in war … got conveniently

Poland and the return of a lost.” Judt rightly points out

right-wing revisionist history. the communists’ interest in

Critics have pointed out the “flattering the recalcitrant

possible dangers of limiting local population by inviting it

free speech and of building to believe the fabrication now

a martyrological narrative deployed on its behalf by the

claiming that the world USSR—to wit, that central and

does not understand how eastern Europe was an innocent

much Poland and Poles Czesława Strąg and Rozalia

victim of German assault.”

have suffered. Kateganer (Maria Damaszek) during

the war. Czesława decided to protect The retracted legislation

The diplomatic fallout with Rozalia by having her baptized, with sends the signal that history

the name of a Polish girl who was

Israel that followed the law’s thought to have been sent to Siberia.

is being instrumentalized

entry into force saw the Family Archives of Tomasz T.Koncewicz. to serve a new vision of the

government finally cave in to Used with permission past. Imposing or threatening

pressure by withdrawing the sanctions for statements

Facing History Honestly

most controversial provision. contradicting the official

and Openly

This minor concession was understanding of “what

intended to improve the In trying to understand happened” clearly inhibits the

diplomatic optics. A more the current Polish way of free flow of ideas and leads to

general provision (Article historical mis-memory, the a singular vision of the past.

133 of the Criminal Code) analysis of the late historian Protecting the good name of

remains in force and states: and essayist, Tony Judt, can the state or nation is deemed

“Whoever publicly insults be instructive. He has argued more important than a robust,

the Nation or the Republic that two kinds of memories comprehensive, and inclusive

of Poland shall be subject to emerged from what he calls the discussion about the past—a

the penalty of deprivation of official version of the wartime discussion that must tolerate

liberty for up to three years.” experience, which became statements, often shocking

It is now being deployed dominant in Europe by 1948. and controversial, though

to impose the approved One was that of the things done nonetheless adding to the

historical narrative on all of to “us” by the Germans during debate. Historical discourse

us. Civil liability, as used in the war, and the other that of belongs to this category.

the case of the two historians, things (however similar) done

completes the repression. by “us” to “others” after the By revealing the past, we

war. According to Judt, this discover the present. This

SPRING/SUMMER 2021 n 13approach allows us to bring of the Polish people and

controversial aspects of the the heroism of the Polish

nation’s history to the fore Righteous Among the Nations

and discuss them openly and or questioning Poland’s

dispassionately. These are both resistance in the face of the

the price for and the challenge Nazi atrocities. Nobody denies

of maintaining what American that. My point is different.

political philosopher John We survived because history

Rawls has evocatively called was always a repository

an “overlapping consensus” from which to imagine a

and living in a society with new order and rebuild life.

competing visions and We relied on our shared

understanding of our history. commitment and moved

Nobody should be excluded, Tomasz Tadeusz Koncewicz accepts forward. We remembered

Yad Vashem’s Righteous Among the

much less penalized, for Nations medal on behalf of his family, both the good and the bad

professing their own vision 2014. and what saved us and our

of history, which may go Family Archives of Tomasz T.Koncewicz.

way of life. Therefore, my

Used with permission

against the mainstream argument against an imposed

political narrative. struggles and common understanding of history

commitments.” This is the favors an inclusive historical

Moving Forward: A kind of intellectual and civic memory that brings together

Collective Denial? fidelity that should inform our and exposes all national

Poland and the Poles find understanding of our history. experiences and narratives.

themselves at a critical Building a historical debate

Unfortunately, in Poland the calls for a living pact among

juncture, suspended between

past continues to be seen as the past, present, and future.

old myths and the narratives of

a collection of indisputable That would move us away

“what happened,” on the one

truths, not open to divergent from what American historian

hand, and the rejection of any

interpretations and historical J. Connelly has called “a

attempts to discover the multi-

debate. Paranoid politics, historiography obsessed with

dimensional past, on the other.

having destroyed judicial minutiae and overgrown

Historical debate should strive

review, the courts, and the free with easy assumptions

for pragmatic recognition that

media, have now set their sights about martyrology,” and

we reshape and re-examine

on historical memory. The push us toward more critical

our civic and constitutional

Polish “politics of resentment” understanding of who we

commitments as we move

and the rising politics of mis- Poles are and where we come

forward. As legal scholars J.

memory threaten to make the from. A nation unready to

Balkin and R. Siegel remark,

past an uncontested sphere, embark on a comprehensive

“we turn to the past not

dominated by one truth journey into its past cannot

because the past contains

superimposed by the state. move forward. When grand

within it all of the answers to

our questions, but because it is All this must not be read gestures dominate, and soul-

the repository of our common as belittling the sufferings searching is lacking, the

14 n GAZETA VOLUME 28, NO. 2nation becomes a captive of its With the judiciary and in this context is about a

past rather than its master. public media in tatters, generational reading of our

national history. It is not about

More than thirty years ago, the government is now uncritical iconoclasm. It is

Jan Błoński’s taboo-breaking implementing what I about recognizing that the past

essay, “The Poor Poles Look

have called elsewhere a must be a key to the future.

at the Ghetto,” broke the cycle

After all, national constitutions

of silence. He wrote (my “politics of mis-memory” must be understood as

translation): that seeks to present one documents made for people of

Genocide, of which the correct vision of history different views. What matters

Polish people were not guilty, is that no one overarching

for all Poles. narrative exists, and that

happened after all on our

soil and stigmatized this as a tool to fight political disagreement should account

soil forever...Our memory adversaries and to divide for many “contested pasts.”

and public consciousness Poles into “better” and In Poland in 2021, we may

must never forget about this “worse” sorts. Yet, this be crying out in the historical

bloody and heinous sign … politics seems to be engulfing wilderness, but we must not

Our homeland is built first Poland. What is most alarming give up. After all, this is my

and foremost of memory; in is the rise of a government- history, your history, our

other words, only memory backed historical narrative civic history that should be

of the past gives us a chance claiming that a bunch of fancy recognized and owned up

to be ourselves. This past is historians, by revisiting a from bottom-up, rather than

not to be disposed of freely, settled and one-dimensional be ordained top-down by

even though we cannot be history, has transformed the sleight of opportunistic

held directly responsible for poor Poles from victims into political hand. And for

the past in our individual perpetrators. We are told that carrying this truth with me,

capacity. We are obliged to their research and academic I will be forever grateful to

carry this past inside us, queries betray the nation and my grandmother. n

irrespective of how painful aim at deforming the history

it might be. And we should by equating Nazi crimes Tomasz Tadeusz Koncewicz

strive to cleanse it ... all with the actions of the heroic is Director of the Department

the profanity that happened Poles. Is this attractive for of European and Comparative

here on this soil obliges us the masses? By all means, Law, University of Gdańsk,

to perform such an act of as the captive mind is prone a member of the Council

cleansing. On this graveyard to embrace intuitive and of the Fondation Jean

this obligation really boils exonerating myths. Monnet Pour l’Europe, and

down to a respect for one an attorney specializing in

thing: to see our past in truth. Again as put by Błoński, “On litigation before European

this graveyard this obligation supranational courts.

The last thing Poland needs really boils down to … one

today is the spreading of thing: to see our past in truth.”

a culture of treason, using My understanding of civic and

its own vision of the past constitutional commitment

SPRING/SUMMER 2021 n 15EXHIBITIONS Barbara Kirshenblatt-

Gimblett

New Legacy Gallery at POLIN

Museum of the History of Polish Jews Tamara Sztyma

T he new Legacy gallery

at POLIN Museum of

the History of Polish Jews

features distinguished Polish

Jews and their achievements.

Conceived as an epilogue

to POLIN Museum’s

Core Exhibition, which

presents the thousand-year

history of Polish Jews, the

Legacy gallery showcases

exceptional individuals in a

beautiful architectural space

overlooking the Monument to Legacy gallery in POLIN Museum.

the Ghetto Heroes. Photograph by Maciek Jaźwiecki. Courtesy of POLIN Museum of the History of Polish Jews

In determining whom to exclude them? What about • W

ho is representative?

feature in the new gallery and converts? Would the Which individuals best

how to present them, we individual in question want represent the diversity of

considered the following to be identified as a Jew what it means to be a

questions: (and as a Polish Jew) and to “Polish Jew” and the broad

be included in this spectrum of fields in which

• W

ho is a Jew? Who is a presentation? they were active—from the

Polish Jew? How do 18th century to the present?

individuals identify • W

hy does it matter?

themselves in relation to Assuming a case can be • W

ho is distinguished? On

how others identify them, made for identifying an what basis should

whether as Jewish or individual as a Jew (and as a “distinction” be determined?

Polish? If they do not Polish Jew), what is the

• S

hould living individuals

identify themselves as relevance of such

be included?

Jewish or “of Jewish identifications for each

origin,” on what grounds individual and for the • A

nd finally, how does the

would we include or Legacy gallery more story of a particular

generally? individual illuminate the

16 n GAZETA VOLUME 28, NO. 2history of Polish Jews, and Our goal as curators life, and reflection on the

how does the history of condition of modern man.

was to make a selection

Polish Jews illuminate an n I saac Bashevis Singer,

individual’s story? that would form a

Nobel laureate, who, in his

Our goal as curators was not

coherent whole, however novels written in Yiddish

simply to select outstanding kaleidoscopic it might be, but translated into many

individuals, but to make a languages, evoked the world

and to raise questions,

selection that would form a of Jewish towns in Poland.

coherent whole, however indeed the very questions n Shmuel Josef Agnon,

kaleidoscopic it might be, and that we asked ourselves. Nobel laureate, who was a

to raise questions, indeed the creator of modern Hebrew

very questions that we asked to explore the lives, careers, literature, where his Polish

ourselves. The twenty-six and achievements of the hometown of Buczacz, in

individuals featured in the twenty-six individuals in Austrian Galicia, and the

Legacy gallery represent but greater depth. Tamara Sztyma, Land of Israel meet.

one constellation—twenty- co-curator of the gallery,

Bruno Schulz, who

undertook extensive research

n

six is the numerical value of

combined literature and art

koved (Heb. honor) in and selected the rich content

and made the world of

gematria. The volume that for beautifully designed

Drohobycz, his provincial

accompanies this gallery (see interactive stations.

hometown, the mythical

link below) presents many

In this gallery and in the center of his artistic

more individuals, and we hope

accompanying volume, we microcosm.

even more will be nominated

bring a critical perspective to

by our visitors and readers and n Henryk Berlewi, a founder

what might otherwise be a

included in an online of the Jewish and Polish

“Hall of Fame” and Jewish

supplement to the gallery. inter-war avant-garde, who

apologetics, by considering

was also a pioneer of

The Legacy gallery offers the social and historical

modern typography.

another way to engage with the conditions that affected Jewish

history of Polish Jews. creativity throughout the n Alina Szapocznikow,

Hopefully, those who thousand-year history of whose highly personal

experience this gallery will be Polish Jews. sculpture, at the juncture of

inspired to revisit the Core body, memory, and trauma,

Exhibition and rediscover The Twenty Six defined a new direction in

some of these luminaries contemporary art.

n J ulian Tuwim, one of the

within the historical narrative most admired creators of n Ida Kamińska, doyenne of

presented there. The Legacy modern Polish poetry, who the Yiddish stage as actress,

gallery offer a more intimate combined the creative director, and theatre

visitor experience in an potential of language, poetics manager before and after

inspiring space and opportunity of the paradoxes of everyday the Holocaust.

SPRING/SUMMER 2021 n 17n Arnold Szyfman, founder

of modern Polish theatre as

director, playwright, and

institution builder.

n Samuel Goldwyn, one of

Hollywood’s creators, a

film producer known for

excellence in the movie

industry.

n Aleksander Ford, key

figure in 20th-century

Polish cinematography and

creator of the iconic film,

The Teutonic Knights.

n H

enryk Wars, a popular

composer for cabaret and

film, remembered to this day

for his hit tunes in both

Poland and the United States.

n Artur Rubinstein, virtuoso

pianist, considered his era’s

greatest interpreter of

Chopin.

n Bronisław Huberman,

celebrated violinist and

founder of the Palestine

Symphony Orchestra

Hubert Czerepok’s Tree of Life, inspired by the Kabbalah, won POLIN Museum’s

(forerunner to the Israel competition for an artwork capturing the Legacy gallery’s celebration of the

Philharmonic Orchestra) in achievements of Polish Jews.

Photograph by Maciek Jaźwiecki. Courtesy of POLIN Museum of the History of Polish Jews

1936, who helped musicians

flee Europe for British n Rosa Luxemburg, activist n arek Edelman, member

M

Mandate Palestine on the

of the Polish and German of the Bund, the Jewish

eve of the Holocaust.

socialist movement, Labor Movement, a leader

n avid Ben-Gurion, first

D supporter of democracy and of the Warsaw Ghetto

Prime Minister of Israel, the proletarian revolution, Uprising, and an activist

signed the Declaration of the who paid with her life for in Poland’s post-war

Establishment of the State of her involvement in the democratic opposition.

Israel on May 14, 1948. revolutionary movement.

18 n GAZETA VOLUME 28, NO. 2n Ludwik Zamenhof, creator The Legacy gallery n Leopold Kronenberg,

of Esperanto, the most entrepreneur, industrialist,

offers a more intimate

successful international banker, and philanthropist,

language, in support of visitor experience in active in Polish and Jewish

the utopian ideal of worlds during the 19th

an inspiring space and

universal humanity. century.

opportunity to explore

n J anusz Korczak, educator, n Helena Rubinstein, an art

pediatrician, and writer, the lives, careers, and collector and business

founder of Jewish and woman who created one of

achievements of the

Catholic orphanages, creator the first cosmetic empires in

of a modern pedagogy that twenty-six individuals the world, revolutionizing

supports the autonomy and the idea of beauty.

in greater depth.

rights of the child.

The Legacy gallery’s

Parliament, co-founder of

n S

ara Schenirer, creator of companion book is Legacy of

the Institute of Judaic

a network of pioneering Bais Polish Jews, edited by Barbara

Sciences in Warsaw, and a

Yaakov schools, which Kirshenblatt-Gimblett and

leader in Jewish communal

transformed the education of Tamara Sztyma, published by

life in Poland during the

Orthodox Jewish girls by POLIN Museum of the History

inter-war years.

offering secular subjects, and of Polish Jews, 2020. n

which continue to this day in n Joseph Rotblat, nuclear

Copies of the e-book can be

Europe, North America, physicist who worked on

ordered at:

Israel, and South Africa. the atom bomb, but

https://ebookpoint.pl/ksiazki/

abandoned that project to

n Abraham Stern, brilliant legacy-of-polish-jews-barbara-

devote himself to research

mathematician and inventor, kirshenblatt-gimblett-tamara-

on the devastating effects of

active in the 18th and 19th sztyma,e_1wzg.htm.

radiation, and who received

centuries, the first Jew

the Nobel Peace Prize for

admitted to the Warsaw Barbara Kirshenblatt-

his advocacy for nuclear

Society of the Friends of Gimblett, PhD, is the Ronald

disarmament.

Science. S. Lauder Chief Curator of the

n Raphael Lemkin, lawyer Core Exhibition and Advisor

n elene Deutsch, disciple

H to the Director at POLIN

who created the word

of Sigmund Freud, co- Museum of the History of

“genocide,” after the

founder of the Vienna Polish Jews in Warsaw.

Holocaust, and who fought

Psychoanalytic Institute,

tirelessly for the United

pioneer in the study of Tamara Sztyma, PhD, is

Nations Convention on the

female psychology. Curator of Exhibitions at

Prevention and Punishment

of the Crime of Genocide, POLIN Museum of the History

n Moses Schorr, rabbi,

which was ratified in 1948. of Polish Jews.

historian, Member of

SPRING/SUMMER 2021 n 19Wilhelm Sasnal: Such a Landscape

Temporary Exhibition at POLIN Museum of the History of Polish Jews

June 17, 2021–January 10, 2022

I n June 2021, a new

exhibition of works by

Wilhelm Sasnal, one of the

most outstanding contemporary

Polish artists, opened at POLIN

Museum. The exhibition

presents paintings and drawings

depicting familiar and remote

landscapes juxtaposed with

well-known figures.

Set against the “landscape” of

the Shoah, this exhibition is part

of POLIN Museum program

activities in which artists

explore the history, culture, and First of January (Back), 2021, oil on canvas.

legacy of Polish Jews. The Courtesy of the artist and Foksal Gallery Foundation, Warsaw

exhibition, curated by Adam imately sixty artworks will be debate on the difficult past and

Szymczyk, promises to draw presented for the first time. art (October), and a lecture on

international attention to new Wilhelm Sasnal’s abstract

ways of (re)configuring the land Wilhelm Sasnal’s work has been

painting (November). For

in relation to its peopled history. inspired by visual information

information on the Sasnal

In 2003–14, Szymczyk was at derived from various sources

exhibition and activities,

Kunsthalle Basel, and during and contexts, including

please visit:

2014–17 served as artistic television, the internet, and the

https://www.polin.pl/en/

director of Documents 14 in press. Sasnal also draws

wilhelm-sasnal and

Athens and Kassell. inspiration from works by other

https://www.polin.pl/en/

artists, especially photographers.

The exhibit features works on geop-online-activities-and-

loan from the artist, interna- Online events will accompany initiatives. n

tional collections, and public the exhibition. The program

and private collections in will include a discussion on the

Poland, including POLIN lasting impacts of Holocaust

Museum. Some of the approx- landscapes (September), a

20 n GAZETA VOLUME 28, NO. 2Sweet Home Sweet: A Story of Survival,

Memory, and Returns Jakub Nowakowski

Galicia Jewish Museum

August 2021–July 2022

When [my father] was

in the Kraków ghetto he

was still taking photos,

and those photos were

buried in Płaszów and

discovered after the war,

he hid them in a pickle

jar, a glass pickle jar

in Płaszów . . . So I sat

with him in his home

with these photographs

and I asked him who

everyone was in the

Clockwise from top left: Lutz Bergman, Ernest (“Erni”) Abraham, Adam Goldberger,

photo . . . and he told me. and Richard Ores. Likely in late 1941 or early 1942 in the Kraków Ghetto.

Courtesy of Michelle and Nina Ores

He remembered their

names, he remembered if family and their relationship to remove the dead

to Poland. The exhibition bodies in a wooden cart.

they survived the war, he

will explore how Holocaust

remembered everything When they got near me,

memory and narratives are

about them. transmitted through the I spoke and scared them.

—Michelle Ores generations, and how the “Sorry,” I said. “I am

children and grandchildren

S

still alive. Could you

weet Home Sweet: A Story of survivors engage with

take me to the hospital,

of Survival, Memory, contemporary Poland.

and Returns, an upcoming please?”

exhibition at the Galicia Background on the ―Richard Ores’s testimony

Jewish Museum in Kraków, Ores Family

Poland, is devoted to three Two men came with a Oskar Ryszard Ores, known as

generations of the Ores stretcher . . . and started Richard, was born in Kraków

SPRING/SUMMER 2021 n 21in 1923, into an assimilated

Jewish family. His father held

several jobs and his mother’s

family owned a kosher

sausage factory in Kraków.

After the outbreak of World

War II, Richard was forced

to live in the Kraków ghetto

with his mother and sister. In

March 1943, he was marched

to Płaszów, a nearby labor

camp. In the final months of

the war, he was a prisoner

Irena Keller, Richard Ores’s first wife, in the early years of the war.

in three other concentration Photograph by Richard Ores. Courtesy of Michelle and Nina Ores

camps: Sachsenhausen,

Flossenbürg, and finally and care of many of the city’s work has focused on Jewish

Dachau, where he was Jewish heritage sites, with the history and heritage. Many

liberated in April 1945. Ronald Lauder Foundation. other members of the family

For these actions, he was have forged their own various

Richard was the only one in awarded the Knight’s Cross relationships to Poland and

his immediate family who of the Order of Merit of the the Holocaust.

survived. After the war, he Republic of Poland, the Cross

recuperated in a US Army of the Home Army, and the The Galicia Museum

hospital and, a few years later, Oświęcim Cross. He was Exhibit

attended medical school in also a consultant on the film I lived in Kraków for two

Bern, Switzerland, emigrating Schindler’s List as the film

to New York in 1955. But he years, that’s where my

depicted several of the places

never forgot about Poland. in which he survived the war. grandfather grew up. He

Richard maintained a was there during the war,

Though Richard died in

relationship with Poland 2011, the second and third he was in the Płaszów

after the war, returning generations of his family concentration camp.

frequently and staying in have continued to be When I was in Kraków,

touch with friends in Kraków, involved with Polish Jewish

among them heroes from the for most of the time I

life. His daughter Michelle

Kraków Ghetto like Julian is engaged in the Kraków lived a ninety-second walk

Aleksandrowicz and Tadeusz Jewish community and the away from the apartment

Pankiewicz. In New York, preservation of Jewish life my grandfather lived in

he raised funds for hospital and heritage in Poland. One of

equipment for a clinic in before the war . . . and the

her sons, Adam, has lived in

Kraków and for the renovation Poland since 2017, where his market I would always

22 n GAZETA VOLUME 28, NO. 2go to was right across the

street from it. . . . I would

pass by the cemetery

where there’s a monument

for his family members

and a little plaque for his

family members who were

killed in the Holocaust,

and I gave tours of the

concentration camp that

he was in . . . and of the

ghetto that he was in. I

went to Rosh Hashanah

Richard Ores (hidden in middle) and two friends, likely during forced labor on a

services in 2018 in the farm in Prokocim in 1941.

Photograph preserved by Richard Ores. Courtesy of Michelle and Nina Ores

room where he was

Bar Mitzvahed in the life today. Richard visited about the relationship between

Poland frequently, bringing ethnic Poles and Jewish

High Synagogue.

his family to visit Kraków and survivors and visitors, with

―Adam Schorin Warsaw during communism, the goal of understanding this

Many Polish Holocaust the early days of democracy relationship today.

survivors and their in the 1990s, and the current

The exhibition will be

descendants understandably period of Jewish renewal. The

arranged in a modern and

have a view of Poland that family’s story offers a path of

visually attractive style. It will

resembles the Poland of their how one family formed their

present both historical objects

parents’ or grandparents’ own vibrant connections to the

(letters, documents, photos)

childhood and the horrors country of their roots, while

and audiovisual materials:

of the war. The Ores family, still living with the pain and

interviews and testimony

through its continued trauma of the Holocaust.

from Richard, recorded in

engagement with Poland, While Poland has become the 1990s and early 2000s, as

has a relationship with the an important destination for well as interviews with family

country that, while very Jewish heritage tourism over members recorded specifically

centered on the Holocaust the last few decades, there for the exhibition. n

and their family history, is rarely any meaningful

has a strong connection to interaction between visitors Jakub Nowakowski is

Poland as a whole and to the and locals. This exhibit will Director of the Galicia Jewish

renewal of Jewish Polish raise challenging questions Museum in Kraków. n

SPRING/SUMMER 2021 n 23A Grandson’s Reflection

on Sweet Home Sweet: The

Ores Family Exhibition

Adam Schorin

F or the past nine months, I have been on the

curatorial team behind Sweet Home Sweet, the

Galicia Jewish Museum’s upcoming exhibition

on Richard Ores and his family’s relationship One of the photographs Richard Ores buried in Plaszόw.

to Poland. Unique among the curators, I am It depicts, from left: Adam Wnuczek, Rena Rosenberg,

two unidentified people, Lusia Łuszczanowska, Helga

also a member of this family—Richard was my Łuszczanowska, Irena Keller, Władek Ratner (or Rath),

grandfather. I didn’t know him very well: he was Helena Haber, and Richard Ores.

somewhat estranged from the family, having left Courtesy of Michelle and Nina Ores

my grandmother nearly thirty years before I was you notice the arched wall of the ghetto stretching

born. My grandmother, Celia, is also a Holocaust from the edge of the frame, peaking in a small hill

survivor. I grew up seeing her several times a over Irena’s head.

week and I’ve known her story of survival as

long as I can remember. But Richard’s story What to make of these images? What do they tell

was something of a mystery to me. There were us about the people and events they depict, and the

comments he’d made to me about Kraków in the person (or persons) behind the camera? Richard

latter years of his dementia (comments I hardly continued to take photographs (and videos) for the

remember now), the framed Jude star he kept in rest of his life, leaving behind boxes and trash bags

his living room (I didn’t even know if it had been and film canisters with thousands of images across

his), and the handful of wartime stories passed continents, marriages, families. He often appears

down by my mother. himself, handing the camera off to a wife, a child,

or a friend, smiling goofily or looking formal and

It wasn’t until I moved to Poland in 2017 that I composed. Taken together, these photographs

finally watched Richard’s testimony and looked and videos form a kind of auto-ethnography of

through the photographs he buried in a glass jar Richard, a narrative threaded through the various

in Płaszów. These were photographs of his family states and stages of his life. Even though I knew

and friends from childhood, as well as some taken him only obliquely, it occurred to me recently that

in the early years of the war, at a forced labor I’ve seen more images made by Richard than by

farm in Prokocim and in the Kraków Ghetto. anyone else in my family—probably more than

In one photograph, of several friends including by anyone else I know. That’s been near the heart

Richard and his future first wife Irena, everyone of the work I’m doing with the museum team in

seems to have removed their armband (which preparing this exhibition: coming to know my

Jews were forced to wear and which appear in grandfather through the images he saved and the

other photos), or hidden it behind the arm of the ones he created. n

person next to them. They look like any group of

young people from the past, some smiling, some Adam Schorin is a writer and former co-director

stiff, some (Richard included) not looking at the of FestivALT. Based in Warsaw, he is a former

camera. You don’t realize anything is wrong until assistant editor for Gazeta.

24 n GAZETA VOLUME 28, NO. 2You can also read