Estimating the benefit of well-managed protected areas for threatened species conservation - Fuller Lab

←

→

Page content transcription

If your browser does not render page correctly, please read the page content below

Estimating the benefit of well-managed protected

areas for threatened species conservation

STEPHEN G. KEARNEY, VANESSA M. ADAMS, RICHARD A. FULLER

H U G H P . P O S S I N G H A M and J A M E S E . M . W A T S O N

Abstract Protected areas are central to global efforts to pre- The supplementary material for this article is available at

vent species extinctions, with many countries investing https://doi.org/./S

heavily in their establishment. Yet the designation of pro-

tected areas alone can only abate certain threats to biodiver-

sity. Targeted management within protected areas is often

required to achieve fully effective conservation within Introduction

their boundaries. It remains unclear what combination of

protected area designation and management is needed to re-

move the suite of processes that imperil species. Here, using

Australia as a case study, we use a dataset on the pressures

N ationally designated protected area networks are now

central to biodiversity conservation strategies globally

(Coetzee et al., ; Watson et al., ) as they are consid-

facing threatened species to determine the role of protected ered the most effective way to overcome the threats that are

areas and management in conserving imperilled species. We causing the current biodiversity crisis (Rands et al., ).

found that protected areas that are not resourced for threat Although recent research has found that protected areas

management could remove one or more threats to , generally support greater species richness and abundance

(%) species and all threats to very few (n = , %) species. than comparable areas that are not protected (Barnes

In contrast, a protected area network that is adequately re- et al., ; Gray et al., ), and they are mostly effective

sourced to manage threatening processes within their at mitigating vegetation clearing by human activity

boundary could remove one or more threats to almost all (Naughton-Treves et al., ; Joppa et al., ), there is

species (n = ,; c. %) and all threats to almost half (n = also evidence that under current levels of funding many pro-

, %). However, (%) species face one or more tected areas are unable to abate the many other processes

threats that require coordinated conservation actions that that cause species declines (Craigie et al., ; Joppa &

protected areas alone could not remove. This research Pfaff, ). Despite pronounced protected area expansion

shows that investing in the continued expansion of over recent decades and ambitious global targets for future

Australia’s protected area network without providing ad- growth under the Strategic Plan for Biodiversity (CBD,

equate funding for threat management within and beyond ; UNEP-WCMC & IUCN, ), little is known about

the existing protected area network will benefit few threa- the extent to which they can abate the full range of threaten-

tened species. These findings highlight that as the inter- ing processes that imperil species (Watson et al., ).

national community expands the global protected area Given the central, and sometimes sole, focus on the es-

network in accordance with the Strategic Plan for tablishment of protected areas to fulfil international conser-

Biodiversity, a greater emphasis on the effectiveness of vation targets (Joppa & Pfaff, ; Lopoukhine & de Souza

threat management is needed. Dias, ; Dudley et al., ), it is important to understand

the extent to which protected areas can mitigate threatening

Keywords Aichi targets, Australia, Environment Protection

processes. For example, Australia’s National Reserve System

and Biodiversity Conservation Act, EPBC Act, protected is the country’s most important investment in biodiversity

area effectiveness, protected area management, threats, conservation (Commonwealth of Australia, b) and in

threat management the Environment Minister announced to the World

Parks Congress that Australia had achieved its international

commitments because it reached the areal component of the

goal of % of land within protected areas as outlined in

STEPHEN G. KEARNEY (Corresponding author) and JAMES E. M. WATSON* School of Aichi Target of the Strategic Plan for Biodiversity

Earth and Environmental Sciences, University of Queensland, Steele Building, (Secretariat of the CBD, ; Hunt, ). Many other na-

Brisbane, Queensland 4072, Australia. E-mail stephen.kearney@uq.edu.au

tions are making progress towards their own protected area

VANESSA M. ADAMS, RICHARD A. FULLER and HUGH P. POSSINGHAM School of

Biological Sciences, University of Queensland, Queensland, Australia

coverage targets. For example, both South Africa and

Canada are planning a significant increase to their protected

*Also at: Global Conservation Program, Wildlife Conservation Society, Bronx,

New York, USA area networks to make their contribution to the global

Received July . Revision requested September . % target by (Government of South Africa, ;

Accepted November . Government of Canada, ).

Oryx, Page 1 of 9 © 2018 Fauna & Flora International doi:10.1017/S0030605317001739

Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. UQ Library, on 07 Oct 2018 at 19:25:31, subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms.

https://doi.org/10.1017/S00306053170017392 S. G. Kearney et al.

As national and global protected area networks are dra- Using this summary we quantify the role that protected

matically expanded to halt biodiversity decline (Venter areas play in separating threatened species from the pro-

et al., ; Watson et al., ; Barr et al., ), it is vital cesses that threaten their persistence.

to understand their effectiveness at conserving biodiversity.

Given Australia is one of the first nations to have claimed to

have met the % terrestrial area target, it is a useful case Methods

study in which to assess the extent that protected areas

can abate those processes that threaten species. Despite hav- Australian threatened species data

ing a large protected area network, the country has a history

Species that have been classified as threatened by the

of recent extinctions (Woinarski et al., ) and with

Australian Department of the Environment and Energy’s

. , species currently listed as threatened with extinc-

Threatened Species Scientific Committee and Minister are

tion nationally (Commonwealth of Australia, ), further

listed under the Environment Protection and Biodiversity

extinctions are likely (Woinarski et al., ). Furthermore,

Conservation Act (Commonwealth of Australia,

most Australian species face multiple threats (Evans et al.,

b). We undertook this study in early , at which

) that require a variety of actions to mitigate. These

time there were , Australian species listed as threatened

range from protected area designation and targeted threat

under the Act. We followed previous studies (Carwardine

management across protected and non-protected areas, to

et al., ; Evans et al., ) and included all terrestrial

stronger legislation and better land-management practices

and freshwater vertebrate, invertebrate and plant species,

(Lindenmayer, ; Woinarski et al., , ).

as well as marine species that rely on land or freshwater

Quantifying the variety of actions needed to mitigate the

for a part of their life-cycle. We only considered threats to

impacts of threats on imperilled species is vital for under-

marine species that originate and require management on

standing the response required to conserve threatened spe-

land. Excluded from the analysis were extinct species,

cies. Where legal support for protected areas is strong, their

species that face uncertain threats and exclusively marine

designation alone will be effective at mitigating a number of

species. In total, , Australian threatened species were

threats, particularly those that cause habitat loss (e.g. agri-

considered in this analysis.

culture, urbanization). Nevertheless, many threats operate

irrespective of land tenure and, as such, management is re-

quired to mitigate their impacts. Where threats can be dealt Data on threatening processes

with at a local or point-basis, targeted management within a

protected area will effectively mitigate these (e.g. invasive Information on Australian threatened species and the

species, fire), but some threats are pervasive across the land- threats reported as impacting them are available through

scape and therefore require a systematic management ap- the Species Profiles and Threats database (Commonwealth

proach both inside and outside protected areas (e.g. of Australia, ). This database provides threat data on

invasive diseases and pathogens). In Australia, for species protected under the Environment Protection and

example, threats such as inappropriate fire regimes and Biodiversity Conservation Act and has been used in a num-

invasive species are contributing to the severe decline of ber of studies that assess threatening processes on Australian

numerous mammal species in one of Australia’s premiere species (Evans et al., ; Walsh et al., ). For this study

protected areas (and a UNESCO Natural World Heritage we used information from the database that was current as

site), Kakadu National Park (Woinarski et al., ). To ad- of late .

equately conserve these threatened species, protected area The information on threats is compiled using a range of

managers must be resourced to undertake intensive man- sources including listing advice, recovery and action plans,

agement of these threats. In evaluating the role of protected published literature and expert knowledge (Commonwealth

areas in threatened species conservation it is vital to recog- of Australia, ). It is likely that this information is not ex-

nize that in many circumstances protected area designation haustive and the listed threats are likely to be those that are

must be complemented with management to conserve obvious and tangible to managers of threatened species,

species effectively. meaning subtle threats may be overlooked and not reported.

Here we provide the first holistic assessment of the extent The Species Profiles and Threats database follows the stan-

to which a continental protected area network mitigates the dardized Threats Classification Scheme outlined by Salafsky

range of threats to species at risk of extinction. In doing this et al. (). These threat classifications are the same as

we aim to understand how effective protected areas are at those used by IUCN for the Red List process and allow com-

removing the processes that threaten species with extinc- parison across regions and taxonomic groups (IUCN, ).

tion. Using a recently compiled national database on the This threat classification scheme contains direct threat

threats to Australian species, we summarize the range of types and one type for new and emerging threats (‘Other op-

management actions required to mitigate these threats. tions’; Salafsky et al., ). The classification scheme is

Oryx, Page 2 of 9 © 2018 Fauna & Flora International doi:10.1017/S0030605317001739

Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. UQ Library, on 07 Oct 2018 at 19:25:31, subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms.

https://doi.org/10.1017/S0030605317001739Benefit of protected areas 3

based on a three-level hierarchy, with each level increasing where there is adequate funding and resources provided to

in detail and specificity. The first level (major threat) being undertake effective management of threats within its

the broadest, the second level (sub-threat) being more de- boundary. Here, management is a broad term that refers

fined and the third level (specific threat) being at a finer to activities that mitigate the processes that threaten species

scale. Each major threat has between three and six sub- within the protected area boundary. Management actions

threat classifications. Table provides a full description range from invasive species control and fire management,

and specific details for each major threat classification. to enforcement and habitat restoration (Table provides

full details).

Additionally, a number of threats to Australian species

Threat management are unable to be adequately mitigated by protected areas,

no matter how well resourced and managed (Gaston et al.,

We used government threat abatement plans and peer-

). These threats require a coordinated response across

reviewed literature to identify potential management

protected and non-protected areas, which we label ‘landscape

actions to mitigate each threat. Although there are potential-

management’ (Table ). An example of threats that require a

ly a number of ways to remove each threat and local context

landscape management approach are the invasive diseases

influences what is the most appropriate action, we identify

and pathogens listed as key threatening processes under

what would generally be the conservation action or

the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation

combination of actions used to mitigate each threat. For

Act (Commonwealth of Australia, a). These diseases

clarity we followed the standardized lexicon provided by

impact Australian threatened species and are thought

Salafsky et al. () for conservation actions. Table con-

to have caused or contributed to at least four extinctions of

tains a summary of the threats and conservation actions re-

Australian species (Commonwealth of Australia, ,

quired and Supplementary Table contains the reasoning

, ). The threat abatement plans for these diseases

for the choice of each action.

emphasize a number of management actions to be coordi-

nated nationally. These are minimizing the spread of the dis-

Assessing the effectiveness of the protected area ease by controlling dispersal through quarantine actions and

network to manage threats controlling the movement of infected species, mitigating the

impact on species at infected sites through identified means,

There is no dataset available that provides information on and the establishment of a captive breeding programme

how each individual protected area mitigates the threats oc- for species at high risk of extinction (Commonwealth of

curring within it. We therefore classified each threat relative Australia, , , ). Although effectively managed

to how effective the protected area network could be in over- protected areas play a vital role in mitigating the impact of

coming it. We followed the standardized conservation ac- threats such as this, a coordinated threat management

tions as defined by Salafsky et al. (). Conservation approach across the broader landscape is needed to ensure

actions are interventions that need to be undertaken to re- effective conservation.

duce the extinction risk of a species (Salafsky et al., ). There are local factors that require interpretation to de-

Using these conservation actions, we defined three distinct termine the most appropriate management action. These

threat management scenarios for protected areas. factors influence both the impact of threats and the effect-

The first, which we label ‘unmanaged’, considers pro- iveness of the management action required to deal with it.

tected areas as a legally designated land use, which can over- For example, the impact of salinity can vary widely in its

come threats causing vegetation clearance and habitat loss scale and severity. Where its impact is localized, a protected

but where threat management such as invasive species con- area with restoration efforts can effectively mitigate this.

trol and fire management does not occur (Table ). This Whereas when salinity impacts an entire landscape, as is oc-

scenario captures a situation in which protected area man- curring in Australia’s Murray-Darling Basin, a landscape

agers are inadequately resourced to undertake threat man- management approach is required (Murray-Darling Basin

agement, as is likely to be the case in some protected areas Authority, ). Similarly, to mitigate adequately the

across Australia (Taylor et al., a; Craigie et al., ). In impact of a number of invasive species, multiple levels of

some countries, protected areas are ineffective at achieving management may be required. For example, to abate the im-

their primary goal because of poor legislative support mediate impact of an invasive plant species, control (e.g.

(Watson et al., ). Protected areas designated but never spraying, physical removal) is first needed (IPAC, )

implemented (commonly referred to as paper parks) are but then should be complemented with local (and potential-

unlikely to be able to abate the threats we discuss here. ly national) policies aimed at minimizing its spread and es-

The second scenario, which we label ‘well-managed’, tablishment in new areas (IPAC, ). Additionally, the

considers a protected area as not only a legally designated size of a protected area has a significant impact on its effect-

land use, and hence able to halt habitat loss, but one iveness at mitigating threats. For example, the conservation

Oryx, Page 3 of 9 © 2018 Fauna & Flora International doi:10.1017/S0030605317001739

Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. UQ Library, on 07 Oct 2018 at 19:25:31, subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms.

https://doi.org/10.1017/S00306053170017394 S. G. Kearney et al.

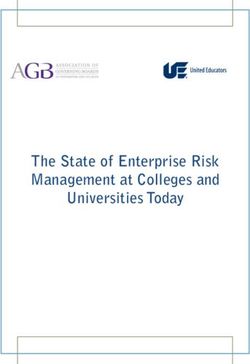

TABLE 1 A description of the threat classifications, the typical conservation actions taken to mitigate these and our assessment of the cor-

responding protected area management scenario. Threat classification, description and conservation actions taken from Salafsky et al.

().

Major threat Key conservation Threat manage-

classification Description Sub-threats actions ment scenario

Residential & Threats from human settlements or Commercial & industrial areas, Site/area protection Unmanaged

commercial other non-agricultural land housing & urban areas, resi-

development uses with a substantial footprint dential & commercial devel-

opment, tourism & recreation

areas

Agriculture & Threats from farming & ranching Agriculture, aquaculture, live- Site/area protection Unmanaged

aquaculture as a result of agricultural expan- stock farming/grazing, timber

sion & intensification, including plantations

silviculture, mariculture & aqua-

culture (includes the impacts of any

fencing around farmed areas)

Energy production & Threats from production of non- Oil & gas drilling, mining, Site/area protection Unmanaged

mining biological resources quarrying & renewable energy

Transportation & Threats from long, narrow trans- Roads & railroads, shipping Site/area protection Unmanaged

service corridors port corridors & the vehicles that lanes, transportation & service

use them including associated corridors, utility & service lines

wildlife mortality

Biological resource Threats from consumptive use of Fishing/harvesting/collecting/ Site/area protection & Well-managed

use wild biological resources including gathering terrestrial, marine & management, com-

both deliberate & unintentional aquatic species pliance &

harvesting effects; also persecution enforcement

or control of specific species Commercial logging Site/area protection Unmanaged

Human intrusion & Threats from human activities that Human intrusion & disturb- Site/area protection & Well-managed

disturbance alter, destroy & disturb habitats & ance, recreational activities, management

species associated with non-con- work & other activities, mili-

sumptive uses of biological tary exercises

resources

Natural system Threats from actions that convert Dams & water management Policies & regulations Landscape

modifications or degrade habitat in service of management

managing natural or semi- Fire & fire suppression, other Site/area protection & Well-managed

natural systems, often to improve ecosystem modification management

human welfare

Invasive & other Threats from non-native & native Invasive non-native species, Site/area protection & Well-managed

problematic species, plants, animals, pathogens/mi- problematic native species invasive/problematic

genes & diseases crobes, or genetic materials that species control

have or are predicted to have Invasive diseases, pathogens & Invasive/problematic Landscape

harmful effects on biodiversity fol- parasites species control management

lowing their introduction, spread

&/or increase in abundance

Pollution Threats from introduction of exotic Garbage & solid waste Site/area manage- Well-managed

&/or excess materials or energy ment, compliance &

from point & non-point sources enforcement

Agricultural & forestry pollu- Legislation & policies Landscape

tants, excess energy, urban & regulations management

sewage & waste water; indus-

try/military pollution

Geological events Threats from catastrophic geo- Landslides Habitat & natural Well-managed

logical events process restoration

Climate change & Threats from long-term climatic Climate change, severe wea- Habitat & natural Well-managed

severe weather changes that may be linked to glo- ther, droughts, storms & process restoration &

bal warming & other severe cli- flooding, temperature ex- species re-

matic/weather events that are tremes, habitat shifting/ introduction

outside of the natural range of alteration

variation, or potentially can wipe

out a vulnerable species or habitat

Oryx, Page 4 of 9 © 2018 Fauna & Flora International doi:10.1017/S0030605317001739

Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. UQ Library, on 07 Oct 2018 at 19:25:31, subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms.

https://doi.org/10.1017/S0030605317001739Benefit of protected areas 5

of large, intact landscapes is the best response to the impacts

of climate change (Watson et al., ; Gross et al., ). As

such, small protected areas that comprise a high proportion

of Australia’s protected area network (Commonwealth of

Australia, a) are unlikely to be able to mitigate the im-

pacts of such threats. Here, we determined the typical ac-

tions used to mitigate each threat. Supplementary Table

provides a full reasoning for the choice of the conservation

action required to mitigate each threat to Australian species.

Level of threat abatement

To estimate the role of protected areas in threatened species

conservation in Australia, we quantify the level of threat

abatement provided by each management scenario. We do

this by calculating the proportion of threats removed by

each scenario to Australian threatened species, and the

number of species that have one or more and all threats aba-

ted by each management scenario. Although these calcula-

tions are theoretical, by comparing the effectiveness of the FIG. 1 The number of Australian threatened species facing each

two protected area management scenarios we approximate of Salafsky et al.’s () major threat classifications (a) and the

the role that well-managed and unmanaged protected areas relative impact of each major threat classification on Australian

play in threatened species conservation in Australia. threatened species (b). The relative impact is defined as the

cumulative number of specific threats within a major threat that

impacts a species. It takes into account that species may face

more than one specific threat under each major threat. For

example, a species may be threatened by an invasive plant

Results species and an invasive animal species and as such is impacted

twice by the major threat classification ‘invasive and problematic

The threats impacting Australian species species’. Threat information is compiled using a range of sources

including listing advice, recovery and action plans, published

Australian threatened species face major threat classes, literature and expert knowledge (Commonwealth of Australia,

with invasive and other problematic species impacting the ). It is likely that this information is not exhaustive and the

greatest proportion of species (n = ,, %; Fig. ). Two listed threats are likely to be those that are obvious and tangible

to species’ managers, meaning subtle threats may be overlooked

other major threats, natural system modifications and agri-

and not reported.

culture, impact over half of Australia’s threatened species

(n = ,, % and n = , %, respectively; Fig. ). The

sub-threats of invasive non-native species (within the The number of threats mitigated by each management

major threat class ‘invasive and other problematic species’; scenario

%) and fire and fire suppression (within the major threat

class ‘natural system modifications’; %) threaten the Under our unmanaged protected area management scen-

greatest number of Australian threatened species. ario, in which protected areas are not resourced for threat

management, the Australian protected area network can re-

move % of all threats to Australian threatened species

(Table ). We found that although the protected area net-

The number of threats reported as impacting Australian work could mitigate one or more threats to , (%) spe-

species cies, it could only remove all threats to (%) species

(Table ). In contrast, under the well-managed scenario,

Each Australian threatened species is impacted by – in which protected areas are adequately resourced for threat

major threats (Fig. a) and – specific threats (Fig. b). management, Australia’s protected area network can re-

On average, each species faces . ± SD . specific threats. move % of threats to all threatened species. Similar to

Only species (%) face a single specific threat and , the unmanaged scenario, we found that although the well-

species (%) face five or more specific threats (Fig. b). managed scenario can remove one or more threats to almost

Oryx, Page 5 of 9 © 2018 Fauna & Flora International doi:10.1017/S0030605317001739

Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. UQ Library, on 07 Oct 2018 at 19:25:31, subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms.

https://doi.org/10.1017/S00306053170017396 S. G. Kearney et al.

of Australia’s threatened species, the other % require well-

managed protected areas complemented with threat man-

agement in non-protected lands. Threats from invasive

diseases and pathogens, air and waterborne agricultural

pollutants, and altered flow regimes from dams require

combined management across the entire landscape. As

such, for all threats to be removed to all species and

ensure the effective conservation of species in Australia,

well-resourced protected areas must be complemented

with effective landscape-scale threat management.

Discussion

Using the actions required to mitigate threats to species, we

evaluated the potential effectiveness of protected areas, the

predominant action taken to protect biodiversity globally, at

conserving threatened species. Using Australia as a case

study, we found that even in the best-case scenario where

protected areas are well-resourced and effectively managed,

only % of threatened species will have all threats removed

by the nation’s protected area network. These results are

FIG. 2 The number of Australian threatened species that face one likely to be an overestimate of the effectiveness of the

or more major threat classifications (a) and the number of

current protected area network, as the few studies that

threatened species facing one or more specific threats (b).

Species facing more than specific threats (n = , .%) were have discussed the adequacy of funding for management

excluded from (b) to facilitate presentation. Threat information of protected areas in Australia have shown that there are sig-

is compiled using a range of sources including listing advice, nificant shortfalls across much of continent (Taylor et al.,

recovery and action plans, published literature and expert a; Craigie et al., ). Taylor et al. (a), for example

knowledge (Commonwealth of Australia, ). It is likely that made the case for an estimated seven-fold increase in invest-

this information is not exhaustive and the listed threats are likely ment needed to fill the current management and protection

to be those that are obvious and tangible to species’ managers,

gap in Australia’s protected area network. Where protected

meaning subtle threats may be overlooked and not reported.

areas are inadequately funded to undertake threat manage-

ment, few species (n = , %) will have all threats removed.

all threatened species (n = ,; c. %), it can only remove Similarly, this analysis overestimates the benefit to threa-

all threats to (%) threatened species (Table ). Of tened species conservation provided by Australia’s current

great concern is that species face threats that require co- protected area network. With the majority of Australian

ordinated landscape-scale management for adequate miti- threatened species inadequately represented in protected

gation (Table ). Protected areas alone, no matter how areas and % of species having no coverage (Watson

well-managed, cannot remove all threats to these species. et al., ), protected areas provide little to no benefit to

The disparity between scenarios can be explained by the these species. This highlights the importance of a landscape

variety of threats to Australian species and the number of scale approach to threat management as many threatened

threats each species faces. Unmanaged protected areas can species occur outside protected areas, and half (n = ,

only effectively mitigate threats causing habitat loss, particu- %) of Australia’s threatened species face threats requiring

larly agriculture, urbanization and transport corridors concerted efforts across protected and non-protected areas.

(Table ). As the majority of Australian species face multiple This emphasizes the need to fund not only establishment of

threats, of which many require management to abate, un- new protected areas but also to adequately fund manage-

managed protected areas cannot remove the majority of ment within and outside the current protected area network.

threats to Australian species. In contrast, well-managed pro- These findings have significant implications for biodiver-

tected areas can abate the two greatest threats to Australian sity conservation globally. As the international community

species: invasive and other problematic species, and natural undertakes concerted efforts to halt biodiversity decline

system modifications as well as threats causing habitat loss (Juffe-Bignoli et al., ), too narrow of a focus on pro-

(Table ). Hence, well-resourced protected areas can remove tected area network expansion will probably lead to an in-

all threats to many more species than unmanaged protected sufficient response. The threat of invasive species, pollution

areas. Although this accounts for the conservation of c. % and fire impact thousands of species globally (Rodrigues

Oryx, Page 6 of 9 © 2018 Fauna & Flora International doi:10.1017/S0030605317001739

Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. UQ Library, on 07 Oct 2018 at 19:25:31, subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms.

https://doi.org/10.1017/S0030605317001739Benefit of protected areas 7

TABLE 2 The total number (and percentage of total) of threats to all Australian species, the number of species with one or more threats, and

all threats removed by the two protected area management scenarios. The unmanaged scenario represents a network of protected areas that

receives no funding for threat management, whereas the well-managed scenario represents a protected area network that is well-funded

and all necessary threat management occurs. Landscape-scale management is required to mitigate threats that either originate outside

protected areas or require coordinated management across all land-tenures.

‘Unmanaged’ protected ‘Well-managed’ protected Landscape All management types

area scenario area scenario management combined

Total number of threats removed 3,056 (26%) 10,220 (86%) 1,651 (14%) 11,871 (100%)

to all threatened species

Number of threatened species with 1,185 (76%) 1,551 (*100%) 815 (52%) 1,555 (100%)

one or more threats removed

Number of threatened species with 51 (3%) 740 (48%) 4 (,1%) 1,555 (100%)

all threats removed

et al., ; Maxwell et al., ) and in many countries, in- threatened species protection and recovery in Australia is in-

vasive species impact a significant proportion of native spe- adequate (Taylor et al., a; Waldron et al., ).

cies (e.g. the USA; Wilcove et al., ). Therefore, we expect Additionally, the allocation of the limited available resources

our findings to be similar in many other nations. Although is currently biased (Walsh et al., ) and often ineffectively

protected areas play a crucial role in solving the biodiversity spent (Bottrill et al., ; Taylor et al., b). Although it is

crisis, we have shown here that this investment will only be unlikely the suggested seven-fold increase in funding

of value if complemented by effective threatened species (Taylor et al., a) for Australia’s protected area network

management. will occur soon, efficiency can be addressed with a strategic

The protected area management scenarios defined in this planning process for threatened species management

analysis are the two extremes of a spectrum. In Australia, (Watson et al., ). Systematic and strategic investment of

few protected areas are probably receiving no threat man- available funding through management action-specific plan-

agement actions within their boundary, just as few are likely ning protocols has proven effective and efficient (Bottrill et al.,

to be adequately and effectively managed for all threats ; Joseph et al., ). These protocols incorporate cost,

within their boundaries. Where Australia’s current pro- benefit and likelihood of success to ensure effective and effi-

tected area network is on this management spectrum is dif- cient outcomes for threatened species. Such protocols have

ficult to determine; however, based on reported funding for been used in some states across Australia (Tasmanian

protected area management, it is likely to be highly variable Government, ; N.S.W. Government, ) but a national

(Taylor et al., a). Taylor et al. (a) report that in approach is required given that threatened species and the

–, the average funding for protected area manage- threats they face are unaffected by state borders.

ment across Australia was AUD ./ha. Although New As the global protected area network continues to expand

South Wales has reported that impacts to threatened species in an attempt to halt biodiversity decline, it is vital to under-

in protected areas are stable or improving for the majority, stand its effectiveness in achieving this goal. We have provided

in .% of protected areas, impacts are increasing (N.S.W. the first continental evaluation of how effective a network of

Government, ). Considering the national average for protected areas is at removing the suite of threats that imperil

protected area management funding is less than one third species. We discovered that a protected area network well-re-

of New South Wales (Taylor et al., a), it is likely that sourced for threat management within its boundaries could

many of Australia’s protected areas are inadequately abate all known threats to half of Australia’s threatened species.

resourced for effectively managing all threats within their Although protected areas will play a role in reducing threats to

boundaries. the other half of Australia’s threatened species, they are unable

Our analysis emphasises the importance of all threats being to mitigate all of the processes that impact these species. A co-

removed from threatened species. Although it is unlikely that ordinated approach across protected and non-protected areas

every threat must be removed to prevent species’ extinction, is therefore required to conserve these species adequately.

recent Australian extinctions suggest that a more holistic ap-

proach to threat management is needed. Insufficient manage-

ment of just a few threats resulted in these preventable Acknowledgements

extinctions (Woinarski et al., ). Well-funded, strategically

We are grateful to the Commonwealth Department of the

planned and coordinated threat management across pro- Environment and Energy for access to the Species Profile and

tected and non-protected areas in Australia is needed to con- Threats Database, and to J. Woinarski and two anonymous reviewers

serve its unique biodiversity. Currently, available funding for for helpful comments on the text. This research received support from

Oryx, Page 7 of 9 © 2018 Fauna & Flora International doi:10.1017/S0030605317001739

Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. UQ Library, on 07 Oct 2018 at 19:25:31, subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms.

https://doi.org/10.1017/S00306053170017398 S. G. Kearney et al.

the Australian Government’s National Environmental Science C O M M O N W E A LT H O F A U S T R A L I A () Species Profile and Threats

Program through the Threatened Species Recovery Hub. Database. Department of the Environment, Australian

Government, Canberra, Australia. Http://www.environment.gov.

au/cgi-bin/sprat/public/sprat.pl [accessed June ].

Author contributions C O M M O N W E A LT H O F A U S T R A L I A (a) EPBC Listed Key

Threatening Processes. Department of the Environment and Energy,

Conception and design of study: SK, VA, RF, HP, JW; analysis and in-

Canberra, Australia. Http://www.environment.gov.au/cgi-bin/sprat/

terpretation of data: SK, JW; drafting the text: SK, JW; revising the text:

public/publicgetkeythreats.pl [accessed June ].

SK, VA, RF, HP, JW.

C O M M O N W E A LT H O F A U S T R A L I A (b) Nominating a Species,

Ecological Community or Key Threatening Process Under the

References EPBC Act. Department of Environment and Energy,

Australian Government, Canberra, Australia. Https://www.

B A R N E S , M.D., C R A I G I E , I.D., H A R R I S O N , L.B., G E L D M A N N , J., environment.gov.au/biodiversity/threatened/nominations

C O L L E N , B., W H I T M E E et al. () Wildlife population trends in [accessed June ].

protected areas predicted by national socio-economic metrics and C R A I G I E , I.D., B A I L L I E , J.E.M., B A L M F O R D , A., C A R B O N E , C., C O L L E N ,

body size. Nature Communications, , . B., G R E E N , R.E. & H U T T O N , J.M. () Large mammal population

B A R R , L.M., W AT S O N , J.E.M., P O S S I N G H A M , H.P., I WA M U R A , T. & declines in Africa’s protected areas. Biological Conservation, ,

F U L L E R , R.A. () Progress in improving the protection of species –.

and habitats in Australia. Biological Conservation, , –. C R A I G I E , I.D., G R E C H , A., P R E S S E Y , R.L., A D A M S , V.M., H O C K I N G S ,

B O T T R I L L , M.C., J O S E P H , L.N., C A R WA R D I N E , J. et al. () Is M., T AY LO R , M. & B A R N E S , M. () Terrestrial protected areas of

conservation triage just smart decision making? Trends in Ecology & Australia. In Austral Ark: The State of Wildlife in Australia and New

Evolution, , –. Zealand (eds A. Stow, N. Maclean & G.I. Holwell), pp. –.

B O T T R I L L , M.C., W A L S H , J.C., W AT S O N , J.E.M., J O S E P H , L.N., Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK.

O R T E G A -A R G U E TA , A. & P O S S I N G H A M , H.P. () Does recovery D U D L E Y , N., G R OV E S , C., R E D FO R D , K.H. & S TO LT O N , S. ()

planning improve the status of threatened species? Biological Where now for protected areas? Setting the stage for the world

Conservation, , –. parks congress. Oryx, , –.

C A R WA R D I N E , J., W I L S O N , K.A., W A T T S , M., E T T E R , A., K L E I N , C.J. & E VA N S , M.C., W AT S O N , J.E.M., F U L L E R , R.A., V E N T E R , O., B E N N E T T ,

P O S S I N G H A M , H.P. () Avoiding costly conservation mistakes: S.C., M A R S A C K , P.R. & P O S S I N G H A M , H.P. () The spatial

the importance of defining actions and costs in spatial priority distribution of threats to species in Australia. BioScience, , –.

setting. PLoS ONE, , e. G A S T O N , K.J., J AC K S O N , S.E., C A N T U -S A L A Z A R , L. & C R U Z -P I N O N ,

CBD () COP Decision X/: Strategic Plan for Biodiversity - G. () The ecological performance of protected areas. Annual

. Https://www.cbd.int/decision/cop/?id= [accessed June Review of Ecology Evolution and Systematics, , –.

]. G OV E R N M E N T O F C A N A D A () Biodiversity Goals & Targets

C O E T Z E E , B.W.T., G A S T O N , K.J. & C H O W N , S.L. () Local scale for Canada. Minister of Environment and Climate Change,

comparisons of biodiversity as a test for global protected area Canada. Http://publications.gc.ca/collections/collection_/eccc/

ecological performance: a meta-analysis. PLoS ONE, , e. CW---eng.pdf [accessed June ].

C O M M O N W E A LT H O F A U S T R A L I A () Threat Abatement Plan for G OV E R N M E N T O F S O U T H A F R I C A () National Protected Area

Beak and Feather Disease Affecting Endangered Psittacine Species. Expansion Strategy for South Africa, Pretoria, South Africa. Https://

Department of the Environment and Heritage, Canberra, Australia. www.environment.gov.za/sites/default/files/docs/npaes_resource_

Https://www.environment.gov.au/system/files/resources/cda- document.pdf [accessed April ].

e-c--bffc/files/beak-feather-tap.pdf [accessed G R A Y , C.L., H I L L , S.L.L., N E W B O L D , T., H U D S O N , L.N., B O R G E R , L.,

June ]. C O N T U , S. et al. () Local biodiversity is higher inside than

C O M M O N W E A LT H O F A U S T R A L I A () Threat Abatement Plan: outside terrestrial protected areas worldwide. Nature

Infection of Amphibians with Chytrid Fungus Resulting in Communications, , .

Chytridiiomycosis. Department of the Environment and Heritage, G R O S S , J., W AT S O N , J.E.M., W O O D L E Y , S., W E L L I N G , L. & H A R M O N ,

Canberra, Australia. Https://www.environment.gov.au/system/files/ D. () Responding to Climate Change: Guidance for Protected

resources/de--d-ba-ffbdeb/files/chytrid- Area Managers and Planners. Best Practice Protected Area

background.pdf [accessed June ]. Guidelines Series, IUCN, Gland, Switzerland.

C O M M O N W E A LT H O F A U S T R A L I A (a) The National Reserve H U N T , G. () IUCN World Parks Congress Opening Ceremony ,

System—Protected Area Information. Department of the Environment, Greg Hunt MP, Federal Member for Flinders, Minister for the

Australian Government, Canberra, Australia. Http://www. Environment. Http://www.greghunt.com.au/Parliament/Speeches/

environment.gov.au/land/nrs/science/capad [accessed June ]. tabid//ID//IUCN-World-Parks-Congress-Opening-

C O M M O N W E A LT H O F A U S T R A L I A (b) The National Reserve System Ceremony-.aspx [accessed June ].

—Protecting Biodiversity. Department of Environment, Australian IPAC (I N VA S I V E P L A N T S A N D A N I M A L S C O M M I T T E E ) ()

Government, Canberra, Australia. Https://www.environment.gov. Australian Weeds Strategy to . Australian Government

au/land/nrs/about-nrs/protecting-biodiversity [accessed June Department of Agriculture and Water Resources, Canberra.

]. IUCN () Classification Schemes. IUCN, Gland, Switzerland.

C O M M O N W E A LT H O F A U S T R A L I A () Threat Abatement Plan for Http://www.iucnredlist.org/technical-documents/classification-

Disease in Natural Ecosystems Caused by Phytophthora cinnamomi. schemes [accessed June ].

Department of the Environment, Australian Government, Canberra, J O P P A , L.N. & P F A F F , A. () Global protected area impacts.

Australia. Http://www.environment.gov.au/system/files/resources/ Proceedings of The Royal Society B, , –.

badd--db--efb/files/threat-abatement-plan- J O P P A , L.N., L O A R I E , S.R. & P I M M , S.L. () On the protection of

disease-natural-ecosystems-caused-phytophthora-cinnamomi.pdf “protected areas”. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of

[accessed June ]. the United States of America, , –.

Oryx, Page 8 of 9 © 2018 Fauna & Flora International doi:10.1017/S0030605317001739

Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. UQ Library, on 07 Oct 2018 at 19:25:31, subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms.

https://doi.org/10.1017/S0030605317001739Benefit of protected areas 9

J O S E P H , L.N., M A LO N E Y , R.F. & P O S S I N G H A M , H.P. () Optimal V E N T E R , O., F U L L E R , R.A., S E G A N , D.B., C A R WA R D I N E , J., B R O O K S , T.

allocation of resources among threatened species: a project et al. () Targeting global protected area expansion for imperiled

prioritization protocol. Conservation Biology, , –. biodiversity. Plos Biology, , e.

J U F F E -B I G N O L I , D., B U R G E S S , N.D., B I N G H A M , H., B E L L E , E.M.S., D E W A L D R O N , A., M O O E R S , A.O., M I L L E R , D.C., N I B B E L I N K , N.,

L I M A , M.G., D E G U I G N E T , M. et al. () Protected Planet Report R E D D I N G , D., K U H N , T.S. et al. () Targeting global conservation

. UNEP-WCMC, Cambridge, UK. funding to limit immediate biodiversity declines. Proceedings of the

L I N D E N M AY E R , D.B. () Continental-level biodiversity collapse. National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, ,

Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States –.

of America, , –. W A L S H , J.C., W AT S O N , J.E.M., B O T T R I L L , M.C., J O S E P H , L.N. &

L O P O U K H I N E , N. & D E S O U Z A D I A S , B.F. () Editorial: what does P O S S I N G H A M , H.P. () Trends and biases in the listing and

target really mean? Parks, , –. recovery planning for threatened species: an Australian case study.

M A X W E L L , S.L., F U L L E R , R.A., B R O O K S , T.M. & W AT S O N , J.E. () Oryx, , –.

Biodiversity: the ravages of guns, nets and bulldozers. Nature, , W AT S O N , J.E.M., B O T T R I L L , M.C., W A L S H , J.C., J O S E P H , L.N. &

–. P O S S I N G H A M , H.P. () Evaluating Threatened Species Recovery

M U R R AY -D A R L I N G B A S I N A U T H O R I T Y () Basin Salinity Planning in Australia. Prepared on Behalf of the Department of the

Management . Murray-Darling Basin Ministerial Council. Environment, Water, Heritage and the Arts by the Spatial Ecology

Https://www.mdba.gov.au/sites/default/files/pubs/Basin_Salinity_ Laboratory, University of Queensland, Brisbane, Australia.

Management_BSM_.pdf [accessed June ]. W AT S O N , J.E.M., D A R L I N G , E.S., V E N T E R , O., M A R O N , M., W A L S T O N ,

N A U G H T O N -T R E V E S , L., H O L L A N D , M.B. & B R A N D O N , K. () The J., P O S S I N G H A M , H.P. et al. () Bolder science needed now for

role of protected areas in conserving biodiversity and sustaining protected areas. Conservation Biology, , –.

local livelihoods. Annual Review of Environment and Resources, , W AT S O N , J.E.M., D U D L E Y , N., S E G A N , D.B. & H O C K I N G S , M. ()

–. The performance and potential of protected areas. Nature, ,

N.S.W. G O V E R N M E N T () State of the Parks . Office of –.

Environment and Heritage, New South Wales. Http://www. W AT S O N , J.E.M., E VA N S , M.C., C A R WA R D I N E , J., F U L L E R , R.A.,

environment.nsw.gov.au/sop/sop-.htm [accessed April J O S E P H , L.N., S E G A N , D.B. et al. () The capacity of Australia’s

]. protected-area system to represent threatened species. Conservation

N.S.W. G O V E R N M E N T () Saving our Species—Technical report. Biology, , –.

Office of Environment and Heritage. Http://www.environment.nsw. W AT S O N , J.E.M., F U L L E R , R.A., W AT S O N , A.W.T., M A C K E Y , B.G.,

gov.au/resources/threatenedspecies/SavingOurSpecies/ W I L S O N , K.A., G R A N T H A M , H.S. et al. () Wilderness and future

sostech.pdf [accessed June ]. conservation priorities in Australia. Diversity and Distributions, ,

R A N D S , M.R., A D A M S , W.M., B E N N U N , L. et al. () –.

Biodiversity conservation: challenges beyond . Science, , W I L C O V E , D.S., R OT H S T E I N , D., D U B O W , J., P H I L L I P S , A. & L O S O S , E.

–. () Quantifying threats to imperiled species in the United States.

R O D R I G U E S , A.S., B R O O K S , T.M., B U T C H A R T , S.H., C H A N S O N , J., C O X , Bioscience, , –.

N., H O F F M A N N , M. & S T U A R T , S.N. () Spatially explicit trends W O I N A R S K I , J.C., B U R B I D G E , A.A. & H A R R I S O N , P.L. () Ongoing

in the global conservation status of vertebrates. PLoS ONE, , unraveling of a continental fauna: decline and extinction of

e. Australian mammals since European settlement. Proceedings of the

S A L A F S K Y , N., S A L Z E R , D., S TAT T E R S F I E L D , A.J. et al. () A National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, ,

standard lexicon for biodiversity conservation: unified classifications –.

of threats and actions. Conservation Biology, , –. W O I N A R S K I , J.C., G A R N E T T , S.T., L E G G E , S.M. & L I N D E N M AY E R , D.B.

S E C R E T A R I AT O F T H E CBD (S E C R E T A R I AT O F T H E C O N V E N T I O N O N () The contribution of policy, law, management, research, and

B I O LO G I C A L D I V E R S I T Y ) () Conference of the Parties advocacy failings to the recent extinctions of three Australian

Decision X/, Strategic Plan for Biodiversity, –. Https://www. vertebrate species. Conservation Biology, , –.

cbd.int/decision/cop/?id= [accessed June ]. W O I N A R S K I , J.C.Z., L E G G E , S., F I T Z S I M O N S , J.A. et al. () The

T A S M A N I A N G O V E R N M E N T () Prioritisation of Threatened Flora disappearing mammal fauna of northern Australia: context, cause,

and Fauna Recovery Actions for the Tasmanian NRM Regions. and response. Conservation Letters, , –.

Department of Primary Industries, Parks, Water and Environment,

Hobart, Australia. Http://dpipwe.tas.gov.au/Documents/Tasmanian Biographical sketches

%Threatened%Species%Prioritisation%June%.pdf

[accessed June ]. ST E P H E N KE A R N E Y is interested in understanding the pressures on

T AY LO R , M., S AT T L E R , P., F I T Z S I M O N S , J., C U R N O W , C., B E AV E R , D., threatened species and how to mitigate these efficiently. VA N E S S A

G I B S O N , L. & L L E W E L LY N , G. (a) Building Nature’s Safety Net AD A M S focuses on the human dimensions of conservation and system-

: The State of Protected Areas for Australia’s Ecosystems and atic environmental decision-making. RI C H A R D FU L L E R is interested in

Wildlife. WWF-Australia, Sydney, Australia. understanding how people have affected the natural world around them,

T AY LO R , M., S AT T L E R , P.S., E VA N S , M., F U L L E R , R.A., W A T S O N , J.E. and how some of their destructive effects can best be reversed. HU G H

M. & P O S S I N G H A M , H.P. (b) What works for threatened species PO S S I N G H A M is interested in decision-making for conservation, includ-

recovery? An empirical evaluation for Australia. Biodiversity and ing spatial planning, optimal monitoring, value of information, popula-

Conservation, , –. tion management, prioritization of conservation actions, structured

UNEP–WCMC and IUCN () Protected Planet Report . decision-making, bird ecology and dynamic systems control. JA M E S

UNEP–WCMC and IUCN, Cambridge, UK, and Gland, WA T S O N is a conservation biogeographer interested in identifying con-

Switzerland. servation solutions in a time of rapid anthropogenic change.

Oryx, Page 9 of 9 © 2018 Fauna & Flora International doi:10.1017/S0030605317001739

Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. UQ Library, on 07 Oct 2018 at 19:25:31, subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms.

https://doi.org/10.1017/S0030605317001739You can also read