ENERGY SAFETY NETS USING SOCIAL ASSISTANCE MECHANISMS TO CLOSE AFFORDABILITY GAPS FOR THE POOR - SEforALL

←

→

Page content transcription

If your browser does not render page correctly, please read the page content below

ENERGY

SAFETY

NETS

Social assistance, in the form

of safety nets, can be a way to

enable access to affordable,

reliable, sustainable and

modern energy, in the same

way that it supports access to

other essential services such as

education, nutrition, or housing.

Research partners:ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The report series was commissioned by Sustaina- Mexico – Paul Sanchez, Danilo Chavez, Claudia Bello,

ble Energy for All (SEforALL). The SEforALL team Adrian Morales, Abigail Bello, and Aban Moreno

was led by Caroline McGregor and Hannah Girar-

deau, who worked in close collaboration with the The report received insightful comments from

Overseas Development Institute (ODI) team, An- peer reviewers. We would like to thank: Sarah

drew Scott, Sam Pickard, and the Catholic Agen- Alexander, Christine Eibs Singer, Laura Merrill,

cy for Overseas Development (CAOFD) team, Charlie Miller, Sheila Pachauri, Dana Rysankova,

Sarah Wykes, who commissioned the in-country Anita Shankar, and Asep Suryahadi. We would

research teams and worked with them to develop like to thank SEforALL staff for their support:

and shape the six country studies, and who wrote Annette Aharonian, Stephen Kent, Glenn Pearce-

the synthesis report and policy guide. Oroz, Sameer Ahmad, Juan Cerda, Jem Porcaro,

and Tracey Crowe.

The research was designed with an intent to ad-

vance the efforts of the People-Centered Ac- We acknowledge with gratitude the financial su-

celerator coalition, a broad group of SEforALL pport provided by the Wallace Global Fund, without

partners who share a commitment to extending which this research would not have been possible.

energy services to the hardest to reach – the re-

mote, the marginalized, the poor. We also acknowledge the core funding for SEforALL

provided by our institutional strategic partners: the

This report was based on research conducted by Austrian Development Agency; the Charles Stewart

several research partners. We would like to thank: Mott Foundation; the Federal Ministry for Europe,

Integration and Foreign Affairs of Austria; the

Brazil – Roberto Schaeffer, Alexandre Salem Szklo, IKEA Foundation; the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of

André Frossard Pereira de Lucena, Antonella Maz- Denmark; the Ministry for Foreign Affairs of Iceland;

zone, and Régis Rathmann and the Ministry for Foreign Affairs of Sweden. For

a full list of SEforALL supporters, please visit our

Ghana – Simon Bawakyillenuo website.

India – Sasmita Patnaik, Shaily Jha, Karishma Pra- We also thank Jenny Nasser (editor) and Vilmar Luiz

dhan, and Abhishek Jain (designer).

Indonesia – Teguh Dartanto, Qisha Quarina, Rus’an

Nasrudin, Fajar N. Putra, and Khaira Abdillah

Kenya – Murefu Barasa, Brian Kinuthia, Beryl

Ajwang’, Ida Githu, and Clara Kamau

ENERGY SAFETY NETS | USING SOCIAL ASSISTANCE MECHANISMS TO CLOSE AFFORDABILITY GAPS FOR THE POOR 3FOREWORD

Sustainable Development Goal 1 (SDG1) calls research to inform best practices at the inter-

for eradicating extreme poverty for all people section of energy policy and social assistance to

everywhere by 2030. One of its underlying tar- protect very poor, vulnerable and marginalized

gets is the implementation of nationally appro- people.

priate social protection systems and measures

covering the poor and the vulnerable. These are Energy Safety Nets demonstrates how govern-

people who struggle to have their basic needs ments are uniquely positioned to target and

fulfilled, such as access to clean air, water and support populations living in energy poverty.

food, which often prompts governments to offer The reality is that the energy needs of poor and

them some form of social assistance. vulnerable populations are unlikely to be cap-

tured by the private sector, which means public

Energy access is also a basic need. A lack of finance must fill this void.

household power and clean cooking leads to

drudgery, reducing people’s income potential, The report that follows is a synthesis of findings

while also exposing them to potential harms, from the broader Energy Safety Nets research

such as fumes from burning firewood indoors. series, which includes six case studies from

If children in poor households cannot read or countries that have experience implementing

study after dark, their education suffers, hurting energy-focused social assistance mechanisms.

their prospects for breaking the poverty cycle. These case studies have uncovered the many

In short, ensuring access to affordable, reliable, complexities of creating such mechanisms. For

sustainable and modern energy, as demanded example, initiatives need to consider how to

by SDG7, is essential for reducing inequalities in make electricity and clean cooking connections

opportunities, reducing poverty and catalyzing and consumption affordable.

development.

One of the overriding messages in this research

Incorporating energy access into the social pro- series is the importance of proper targeting

tection systems urged by SDG1 is already hap- of subsidies. A current lack of evidence on the

pening in various forms around the world. But energy consumption levels within vulnerable

there is little evidence of how mechanisms are households (disaggregated by sex) prevents

designed and the impact they are having on policymakers from determining appropriate

poverty reduction. Sustainable Energy for All thresholds for subsidies. Additional data collec-

(SEforALL) is closing this knowledge gap with tion on the specific energy needs of the poor

its Energy Safety Nets research series. With the would enhance program design and SEforALL

Overseas Development Institute (ODI) and the intends to support this effort. One of our strate-

Catholic Agency for Overseas Development gic priorities is to build a platform for the collec-

(CAFOD), we have developed first-of-its-kind tion, organization and dissemination of data to

ENERGY SAFETY NETS | USING SOCIAL ASSISTANCE MECHANISMS TO CLOSE AFFORDABILITY GAPS FOR THE POOR 4inform policies aimed at universal energy access in high-impact countries, including policies spe- cific to vulnerable groups. I am particularly excited by the insights found in Energy Safety Nets because of the value they will bring to SEforALL’s engagement with nation- al governments for developing integrated ener- gy plans for universal access. The recommenda- tions in this body of work will help governments devise strategies for bringing energy access to their most vulnerable populations, while build- ing on social assistance programs to improve targeting and delivery of public support. While SEforALL will continue to share these lessons in our discussions with governments, I encourage you to read about them in the pages that follow and consider how you can support the develop- ment of Energy Safety Nets. Damilola Ogunbiyi CEO and Special Representative of the UN Secretary-General for Sustainable Energy for All and Co-Chair of UN-Energy ENERGY SAFETY NETS | USING SOCIAL ASSISTANCE MECHANISMS TO CLOSE AFFORDABILITY GAPS FOR THE POOR 5

TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS 3 FOREWORD 4 LIST OF FIGURES 8 LIST OF TABLES 8 ABBREVIATIONS 9 MAP OF COUNTRIES HIGHLIGHTED IN CASE STUDIES 10 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 11 COUNTRY-SPECIFIC INSIGHTS 12 Electricity 12 Clean Cooking 13 Linkages to Social Protection 13 CONCLUSIONS 14 INTRODUCTION 15 WHAT ARE ENERGY SAFETY NETS? 18 GRID ELECTRICITY 21 Connecting customers to the electricity grid 21 Supporting grid electricity consumption 23 OFF-GRID ELECTRICITY 26 Connecting consumers to off-grid electricity and supporting ongoing consumption 26 CLEAN COOKING 27 Connecting consumers to clean cooking fuels and technologies 27 Supporting consumption of clean fuels for cooking 30 HOW EFFECTIVE ARE ENERGY SAFETY NETS IN ENABLING CONNECTIONS AND CONSUMPTION? 31 ‘ACCESS’ AS ENERGY CONNECTIONS 32 Electricity connection 32 LPG connections 33 ENERGY SAFETY NETS | USING SOCIAL ASSISTANCE MECHANISMS TO CLOSE AFFORDABILITY GAPS FOR THE POOR 6

‘ACCESS’ AS ENERGY CONSUMPTION 35 Electricity consumption 36 Clean cooking fuel consumption 38 HOW ARE ENERGY SAFETY NETS LINKED TO SOCIAL PROTECTION? 40 INTEGRATING ESNS INTO EXISTING SOCIAL ASSISTANCE PROGRAMS 41 LINKING ESNS TO EXISTING SOCIAL ASSISTANCE PROGRAMS 42 CONCLUSIONS 43 CONNECTIONS AND CONSUMPTION 44 TARGETING 44 CONSUMPTION THRESHOLD LEVELS 45 SUBSIDY DELIVERY 45 POLITICAL COMMITMENT 46 LOOKING AHEAD 47 REFERENCES 48 GLOSSARY 50 ANNEX 1: ENERGY SAFETY NETS RESEARCH – SUMMARY OF FINDINGS 54 ANNEX 2: KEY INDICATORS 60 COPYRIGHT AND DISCLAIMER 66 ENERGY SAFETY NETS | USING SOCIAL ASSISTANCE MECHANISMS TO CLOSE AFFORDABILITY GAPS FOR THE POOR 7

LIST OF FIGURES Figures Figure 1: Electrification rates for countries highlighted in this study, 1990−2017 22 Figure 2: Subsidized tariff blocks and price per unit (US cents PPP per kWh) 25 Figure 3: Access to clean fuels and technologies for cooking (% households) 28 Figure 4: Number of households (millions) with and without electricity connections 34 Figure 5: Poorest 40% of Indonesian households by type of electricity connection 37 LIST OF TABLES Tables Table ES1: ESNs examined in the study 12 Table 1: Purpose of subsidy schemes and programs reviewed 19 Table 2: Subsidy schemes and programs reviewed, by targeting method 20 Table 3: Energy sector support programs reviewed in this study that meet the definition of ESNs 21 Table 4: Current levels of subsidized tariffs and subsidies in four countries 26 ENERGY SAFETY NETS | USING SOCIAL ASSISTANCE MECHANISMS TO CLOSE AFFORDABILITY GAPS FOR THE POOR 8

ABBREVIATIONS BDT Basis Data Terpadu ESN Energy Safety Net FSUE Fondo de Servicio Universal Eléctrico IBT Increasing Block Tariff KOSAP Kenya Off-Grid Solar Access Project kWh kilowatt hour LMCP Last Mile Connectivity Project LPG Liquefied Petroleum Gas PaHaL Pratyash Hanstantrit Labh PMUY Pradhan Mantri Ujjwala Yojana PT PLN Perusahaan Listrik Negara SDG Sustainable Development Goal SDG7 Sustainable Development Goal 7 VA volt-ampere VDT Volume Differentiated Tariff ENERGY SAFETY NETS | USING SOCIAL ASSISTANCE MECHANISMS TO CLOSE AFFORDABILITY GAPS FOR THE POOR 9

MAP OF COUNTRIES HIGHLIGHTED

IN CASE STUDIES

Mexico India

Ghana

Kenya

Indonesia

Brazil

ENERGY SAFETY NETS | USING SOCIAL ASSISTANCE MECHANISMS TO CLOSE AFFORDABILITY GAPS FOR THE POOR 10EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The Sustainable Development Goal 7 (SDG7) be a way to enable access to affordable, reliable mandate to ensure access to affordable, reliable, and sustainable modern energy, in the same way sustainable and modern energy services for all that it supports access to other essential services means that even the poorest and most disadvan- such as education, nutrition, or housing. Some taged in society should have access to modern countries have tried linking energy subsidies to energy by 2030. As progress is made towards social assistance mechanisms but there is little this goal, the challenge of ensuring universal ac- empirical evidence about how effective these cess will shift from the question of connections to have been in expanding poor households’ energy the question of energy consumption. People who access. To help address this knowledge gap, this cannot afford basic levels of electricity consump- study examined 25 different initiatives or mea- tion or clean cooking, even when they have a con- sures supporting energy access for poor house- nection, are at risk of being left behind. Programs holds in six countries. The countries highlighted to extend access to modern energy will need to in the study are Brazil, Ghana, India, Indonesia, be supplemented by policy measures that make Kenya and Mexico – reflecting different regions, modern energy services accessible and afford- socioeconomic contexts, and experiences imple- able to poor and marginalized social groups. menting social assistance for energy access. General consumer subsidies for energy are one This research is an initial effort to understand how way of reducing energy costs and making access countries have leveraged social assistance mech- to modern energy affordable for poor and mar- anisms to close the affordability gaps for sustain- ginalized people. Though these subsidies have able energy, and to spark the discourse around increased accessibility and affordability general- how other governments facing access deficits ly, they also have significant shortcomings, most might devise similar approaches, appropriate to notably that they do not always benefit the poor. their own contexts, to drive progress toward uni- Social assistance, in the form of safety nets, could versal access and achieving SDG7. Energy Safety Net (ESN) is an umbrella term ESNs can make physical access (i.e. connections) for government-led approaches to support very to electricity or clean fuels affordable or they can poor and vulnerable people to access essential make the unit price of electricity or fuel afforda- modern energy services, defined as electricity ble to consume. ESNs include some form of tar- and clean fuels and technologies for cooking, by geting or eligibility criteria to direct benefits to closing the affordability gap between market pri- those who need them. ces and what poor customers can afford to pay. ENERGY SAFETY NETS | USING SOCIAL ASSISTANCE MECHANISMS TO CLOSE AFFORDABILITY GAPS FOR THE POOR 11

Of the 25 initiatives examined, 13 support con- fied, while in Ghana and Kenya, national electri-

nections to electricity or clean fuels and tech- fication schemes have aimed to extend the grid

nologies for cooking, and 12 support the on- to large unconnected segments of the popula-

going consumption of electricity or clean fuels. tion. Targeting has been primarily geographic, al-

Roughly half of these initiatives can be formally though Brazil’s Luz para Todos program includes

considered ESNs, i.e. they are policy measures administrative selection – in other words, the

specifically targeted to enable poor and vulner- government targets specific regions or groups

able people to access and use electricity and/ for a particular benefit.

or clean fuels and technologies for cooking (see

Table ES1). The other initiatives examined in the In all six countries, the consumption of grid elec-

country studies fall into the category of more tricity has been subsidized to some extent in the

general energy access initiatives that: (a) do not form of a lifeline tariff for consumers of small quan-

target support to poor households, (b) provide tities of electricity. The premise for this quantitative

cash support directly to households that may or targeting approach is that low-income households

may not support energy purchases, or (c) are too generally consume smaller quantities of electric-

recent for any lessons to be drawn. ity and that low-consumption blocks are sized to

meet basic levels of electricity consumption. How-

COUNTRY-SPECIFIC INSIGHTS ever, these assumptions are not always borne out

in practice. In Ghana, for example, some low-in-

Electricity come consumers use more electricity than the

threshold of the first tariff block, and in Kenya the

Programs to connect households to grid and off- lifeline tariff threshold exceeds the consumption

grid electricity in Brazil, Ghana, Kenya and Mex- level of many poor households.

ico have adopted different approaches. In Brazil

and Mexico, the focus has been on connecting In Brazil and Indonesia, quantitative targeting

remote, rural communities that remain unelectri- in electricity tariffs is linked to administrative

Table ES1

TABLE 3: ENERGY SECTOR SUPPORT PROGRAMS REVIEWED IN THIS STUDY THAT

ESNs examined in the study

MEET THE DEFINITION OF ENERGY SAFETY NETS

CONNECTION CONSUMPTION

Tarifa Social

Brazil Luz para Todos

Bolsa Família (Vale Gás)

Ghana Lifeline electricity tariffs

India PMUY PaHaL

Electricity tariffs

Indonesia Kerosene-to-LPG conversion

LPG subsidy

Kenya Lifeline tariff

Differentiated electricity tariffs

Mexico Oportunidades Energéticas

Subsidized LPG

ENERGY SAFETY NETS | USING SOCIAL ASSISTANCE MECHANISMS TO CLOSE AFFORDABILITY GAPS FOR THE POOR 12selection. The social tariff in Brazil is available tunidades) was an important step, yet it was only

only to households on the country’s unified available between 2007 and 2011 due to changes

social assistance register, and the Indonesian in administration.

national electricity utility has begun to use the

unified database (BDT) of the poorest 40 per- While India and Indonesia have provided LPG

cent of households to determine eligibility for connections to tens of millions of households

the lifeline tariff. and subsidized LPG prices, the use of LPG as a

primary cooking fuel remains lower in rural and

Clean Cooking low-income households than in richer and urban

households. The uptake of LPG for clean cooking

In the six countries highlighted in this study, faces several challenges in addition to affordabil-

government programs to support households’ ity; the extent and efficiency of the LPG distribu-

acquisition of equipment for cooking with clean tion system is a key factor affecting its consump-

fuels have focused on the promotion of liquefied tion and the widespread practice of fuel stacking

petroleum gas (LPG). In Ghana and Mexico, sup- – using different fuels and technologies for differ-

port for LPG connections—cylinders, burners ent cooking needs – is another.

and fittings—has had limited reach and been

short-lived. In India and Indonesia, on the other Linkages to Social Protection

hand, programs to connect households to LPG

have been on a massive scale, benefiting 80 mil- The ESNs examined in the six country stud-

lion and 42 million households, respectively. In ies demonstrate links to social assistance pro-

India, where the Pradhan Mantri Ujjwala Yojana grams in two ways – integration and coordina-

(PMUY) program has targeted below-the-poverty tion. In Brazil and Mexico, energy components

line and socially disadvantaged households, the have been integrated into the countries’ wider

cash transfer for 50 percent of the cost of a LPG social assistance programs – Bolsa Família and

connection is subsidized, while subsidies for gas Oportunidades. In both countries, the sep-

refills are deliberately transferred to accounts in arate identity of the energy component was

the name of an adult woman in the household to lost or abandoned. For example, Brazil’s Bolsa

increase their impact. Meanwhile, in Indonesia, Família failed to adjust adequately as LPG pric-

the subsidy of the kerosene-to-LPG conversion es increased, meaning that the cost of LPG to

program is near universal (i.e., not targeted). households increased and households chose to

use the subsidy to support other non-energy

Schemes to enable the consumption of LPG by purchases.

poor households have been linked to the reform

of general fuel subsidies and social assistance Coordination between ESNs and social assis-

programs. In India, the introduction of a Direct tance programs can allow for an administrative

Benefit Transfer scheme to improve efficiency selection of the beneficiaries of the former using

in the implementation of social assistance pro- databases or registers developed for the latter.

grams was extended to LPG, but the benefit is In Brazil, India, Indonesia and Mexico, social as-

untargeted. In Indonesia, targeting is being in- sistance registers or databases are being used to

troduced, using the BDT register of the bottom target support for energy. In Ghana and Kenya

two quintiles of population by income. An en- however, social assistance programs are at earlier

ergy component included in Mexico’s national stages of development and unified social regis-

social assistance cash transfer program (Opor- ters are unavailable.

ENERGY SAFETY NETS | USING SOCIAL ASSISTANCE MECHANISMS TO CLOSE AFFORDABILITY GAPS FOR THE POOR 13CONCLUSIONS consumption and expenditure would inform

energy and social protection policymakers.

The research for this study examined 12 individual • The design and implementation of ESNs

ESNs and compared key lessons learned from the should be appropriate for the country’s in-

experiences of six countries. Variations in the his- stitutional, geographic and economic con-

tory, operation and institutional context of these text. Social assistance and ESN initiatives

initiatives, as well as differences in the availability will need to continuously evolve, adapting

of data make comparisons difficult. However, it is to changing social and economic conditions

possible to draw some general conclusions from and in response to lessons learned from im-

the country case studies, which should serve as a plementation. It may also be necessary to

basis for the design of future ESNs: inform and educate citizens about modern

energy services and ESNs. The design and

• Distinct approaches are needed to support implementation of ESNs should also consid-

energy connections (e.g., wired meter boxes er the gendered nature of energy manage-

and LPG stoves) and ongoing consumption ment within the household; ESNs can be de-

(e.g., monthly electricity bills and regular signed or coordinated with other initiatives

fuel consumption). These may also require to ensure women’s empowerment in energy

different funding and delivery mechanisms. management is protected or enhanced, for

Support for electricity connections or clean example, by targeting resource transfers to

cooking technology distribution may be a women.

necessary first step toward energy access • The success of ESNs depends on strong and

but does not guarantee that energy is afford- sustained political commitment. Among the

able or consumed by the most vulnerable six countries studied, changes in govern-

among the population. ment have led to discontinuations of pro-

• Targeting criteria may differ between ESNs grams and disruptions in measures to sup-

seeking to support consumption versus those port connections and energy consumption.

focused on connections to electricity or ac- Political factors have also proven to influence

cess to clean cooking technology. Policy- the selection of target populations. Howev-

makers must specify and define the intended er, high-level policy commitment for univer-

target population for an ESN as it is being de- sal access to affordable, reliable, sustainable

signed. This determines the criteria or indica- and modern energy can provide the basis

tors that will be used to decide the eligibility for the development and implementation of

of households, including whether support will measures to target poor households.

require one or more targeting approaches

and one or more ESN mechanism. This first-of-its-kind research is intended to

• Household energy consumption data are es- build an evidence base that can inform and

sential to setting an appropriate and transfor- galvanize further work at the intersection of

mational level of subsidy or benefit and should energy policy and social protection by any

be explicit in the design of an ESN. Policy- government similarly motivated to innovate

makers need improved evidence of how much around ESNs. Experimentation on policy de-

and what types of energy poor households sign, robust monitoring and evaluation, and

are currently consuming in order to create ap- further iteration are necessary to establish best

propriate, tailored and supportive programs. practices and efficient programs to support the

Further quantitative research, improved data very poor and vulnerable to access essential

collection, and analysis of household energy modern energy services.

ENERGY SAFETY NETS | USING SOCIAL ASSISTANCE MECHANISMS TO CLOSE AFFORDABILITY GAPS FOR THE POOR 14INTRODUCTION ENERGY SAFETY NETS | USING SOCIAL ASSISTANCE MECHANISMS TO CLOSE AFFORDABILITY GAPS FOR THE POOR 15

The Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), alized people. Fuel and electricity subsidies have

adopted by the world’s governments in 2015, a long history, although poverty reduction has

embody the principle of ‘leave-no-one-behind’. not always been their primary purpose. Gener-

The Sustainable Development Goal 7 (SDG7) al subsidies can have significant shortcomings:

mandate to ensure access to affordable, reliable, they can encourage the use of environmentally

sustainable and modern energy services for all, damaging fossil fuels; they can be a disincentive

means even the poorest and most disadvan- for energy-efficient consumption; they use scarce

taged in society should have access to modern public funds; they can affect the financial viabil-

energy by 2030. ity of energy service providers; and they do not

always benefit the poor — subsidized electricity

The world is making progress towards this goal. tariffs do not benefit households without access

In 2017, 89 percent of the world’s population to electricity, and households above the poverty

had access to electricity and 61 percent access line often receive disproportionately more of the

to clean fuels and technologies for cooking. In total benefit.

urban areas, which are home to half the global

population, the electrification level was 97 per- Social protection systems are sets of policies and

cent (IEA et al. 2019). As access levels approach programs designed to reduce and prevent pov-

100 percent, the challenge of ensuring universal erty and vulnerability (ILO 2017). There have been

access will shift from the question of energy con- suggestions that social protection could be a way

nections to the question of energy consumption. to enable access to affordable, reliable, sustain-

People who cannot afford basic levels of electrici- able and modern energy. For example, the Mary

ty consumption or clean cooking, even when they Robinson Foundation has proposed using social

have a connection, are at dire risk of being left protection systems ‘to rapidly and efficiently ex-

behind. tend sustainable energy services to a country’s

poorest people’ (MRFCJ 2016). Subsidies to en-

That’s where Energy Safety Nets (ESNs) come in. able low-income and marginalized households

to access essential services, such as health and

Many of the approaches to extend access to mod- education, or adequate food and nutrition, are

ern energy, supported by governments and their included in the social protection systems of many

development partners, focus on connections and countries. Social safety nets of this kind are a

the development of commercial markets for en- form of non-contributory social assistance (see

ergy services and products. Market approaches Glossary). They are intended to provide regular

to extend connections or deliver energy services support to targeted poor and vulnerable popu-

too often overlook the needs of people on very lations and have been shown to reduce poverty

low incomes or those who may be disadvantaged and inequality (World Bank 2018).

in other ways. This occurs in rich countries as well

as poor. In order to leave no one behind, mar- There have been examples of governments link-

ket approaches must be supplemented by policy ing the delivery of energy subsidies to social

measures that make modern energy services ac- assistance programs, and cash transfers (a com-

cessible and affordable to poor and marginalized mon tool for social assistance) have been used to

social groups. compensate consumers when fuel subsidies have

been reformed. However, research on the impact

Consumer subsidies for energy are one way of and effectiveness of these initiatives has focused

reducing energy costs and making access to on the fiscal questions and the financial burden

modern energy affordable for poor and margin- of subsidies. Only limited evidence is available

ENERGY SAFETY NETS | USING SOCIAL ASSISTANCE MECHANISMS TO CLOSE AFFORDABILITY GAPS FOR THE POOR 16about how social assistance measures have af- geted support for energy access. The research

fected access to modern energy services. How reviewed literature, analyzed available statistics,

social assistance programs have affected access undertook key informant interviews, and conduct-

to energy or energy consumption by poor house- ed group discussions. The countries highlighted in

holds is not well understood, therefore, nor is the the study—Brazil, Ghana, India, Indonesia, Kenya

potential for social assistance measures to con- and Mexico—were selected because they all have

tribute to the goal of universal access to afford- experience with programs that support energy

able, reliable and sustainable modern energy. access and have some experience implementing

social assistance programs. They also represent

This report is a step towards filling the gap in different regions and present a variety of socio-

knowledge about how social assistance affects economic and institutional contexts.

access to energy and energy consumption by

poor households. It builds on a literature review The key research questions were:

(Scott and Pickard 2018) and presents additional

evidence of the potential for social assistance to • What policy measures have been used to en-

enable poor and marginalized households to ac- able very poor and marginalized people to ac-

cess and use modern energy services. The term cess and use modern energy services?

‘energy safety net’ was coined for the literature • How effective have these measures been in

review to capture the idea of a targeted mea- enabling the poorest social groups to access

sure to enable poor and vulnerable people to and use modern energy services?

access and use electricity and clean fuels and • What links have there been/are there between

technologies for cooking. The concept focuses these measures and wider/other social assis-

on measures to enable access for people who tance programs?

would not be reached by market-based ap- • What changes could be made to enhance the

proaches alone. effectiveness of existing policy measures in

enabling very poor people to access modern

The report is based on research that aims to pro- energy services?

vide guidance for policy- and decision-makers, by

identifying measures that have been successful The report is structured around these four ques-

in enabling very poor people to access modern tions. Section 2 briefly describes the ESNs identi-

energy services and exploring the reasons for the fied in the six countries, and Section 3 discusses

successes and challenges encountered. The ap- their effectiveness from the perspective of ener-

proach was to explore in depth, through country gy access. In Section 4, the links between ESNs

case studies, the experience in different countries and wider social protection systems are exam-

of reaching the poorest social groups with tar- ined. Conclusions can be found in Section 5.

ENERGY SAFETY NETS | USING SOCIAL ASSISTANCE MECHANISMS TO CLOSE AFFORDABILITY GAPS FOR THE POOR 17WHAT ARE ENERGY SAFETY NETS? ENERGY SAFETY NETS | USING SOCIAL ASSISTANCE MECHANISMS TO CLOSE AFFORDABILITY GAPS FOR THE POOR 18

This section describes the key measures to sup- though consumption cannot occur without a connec-

port access to affordable modern energy ser- tion, it does not necessarily follow that a connection

vices found in the six countries highlighted in results in consumption, as the country case studies

this study. To help understand their effective- demonstrate. Of the 25 measures examined in the

ness (discussed in the next section) and whether six countries, 13 primarily support connections and

they meet the definition of an Energy Safety Net 12 support consumption.i1 Table 1 lists the 25 ener-

(ESN), the subsidy schemes can be categorized gy support schemes by purpose. Annex 1 provides

by their purpose and by the kind of targeting a summary of information about each measure, and

they employ (Komives et al. 2005: Table 2.1). more detail can be found in the country case studies.

These schemes are typical of the measures to support

Support for access to energy has two main pur- energy access that can be found in other countries in

poses: to provide connections to modern ener- Africa, Asia and Latin America (Komives et al. 2005;

gy services ((i) electricity and (ii) clean fuels and Scott and Pickard 2018; Siyambalapitiya 2018).

technologies for cooking); and to enable the

consumption of energy. Connections require an Energy subsidies can be untargeted (available to

investment to install or purchase equipment (e.g. everyone), implicitly targeted (available by de-

wiring, meters and stoves), while consumption fault to anyone in a population group, e.g. those

requires a regular payment to a service provid-

i Schemes that support connections to solar household systems

er (e.g. a utility company or LPG distributor). Al- also enable consumption.

Table 1 TABLE 1: PURPOSE OF SUBSIDY SCHEMES AND PROGRAMS REVIEWED

Purpose of subsidy schemes and programs reviewed

COUNTRY CONNECTION CONSUMPTION

• Tarifa Social

Brazil • Luz para Todos

• Bolsa Familia (Vale Gás)

• Self-Help Electrification Program

• Improving Rural Energy Access through

Ghana Solar Home Systems • Lifeline electricity tariffs

• Improved cookstove programs

• LPG Program

• Pratyash Hanstantrit Labh (PaHaL)

• ‘Give it Up’ Campaign

India • Pradhan Mantri Ujjwala Yojana (PMUY)

• Unified Guidelines for Selection of LPG

distributorships

• Electricity tariffs

Indonesia • Kerosene-to-LPG conversion

• LPG price subsidy

• Slum Electrification Project

• Last Mile Connectivity Program

Kenya • Kenya Off-grid Solar Access Project • Lifeline tariff

• Energy and Cash Plus Initiative

• Mwananchi Gas Project

• Differentiated electricity tariffs

Mexico • Fondo de Servicio Universal Eléctrico (FSUE) • Oportunidades Energéticas

• Subsidized LPG price

ENERGY SAFETY NETS | USING SOCIAL ASSISTANCE MECHANISMS TO CLOSE AFFORDABILITY GAPS FOR THE POOR 19with existing connections), targeted by self-selec- is targeted (by self-selection or administratively) at

tion (household behavior) or targeted by adminis- households that are income poor and/or socially

trative selection (Komives et al. 2005). In practice, disadvantaged. Fifteen of the schemes reviewed in

targeting often involves two of these approaches. the six country case studies use self-selection or ad-

For example, a subsidy may be available to anyone ministrative targeting, six have some form of implicit

living within a defined geographic area (implicit tar- targeting and four have no targeting (Table 2).ii2

geting), but the area has been selected because of

a high incidence of poverty (administrative target- ii Targeting approaches can evolve. The current or most recent tar-

geting system is used here to categorize the subsidy schemes

ing). The definition of an ESN implies that support reviewed in the country case studies.

Table 2

Subsidy TABLE 2: SUBSIDY SCHEMES AND PROGRAMS REVIEWED, BY TARGETING METHOD

schemes and programs reviewed, by targeting method

IMPLICIT TARGETING BY ADMINISTRATIVE

COUNTRY MEASURE UNTARGETED

TARGETING SELF-SELECTION TARGETING

Luz para Todos X

Brazil Tarifa Social X

Bolsa Família (Vale Gás) X

Self-Help Electrification Program X

Lifeline electricity tariffs X

Ghana LPG Program X

Improving Rural Energy Access X

through Solar Home Systems

Improved cookstove programs X

Pratyash Hanstantrit Labh X

(PaHaL)

Pradhan Mantri Ujjwala Yojana X

(PMUY)

India

‘Give it Up’ Campaign X

Unified Guidelines for Selection X

of LPG distributorships

Electricity tariffs X

Indonesia Kerosene-to-LPG conversion X

LPG price subsidy X

Slum Electrification Project X

Last Mile Connectivity Project X

Lifeline tariff X

Kenya

Kenya Off-Grid Solar Access X

Project (KOSAP)

Energy and Cash Plus Initiative X

Mwananchi Gas Project X

Differentiated electricity tariffs X

Oportunidades Energéticas X

Mexico

Subsidized LPG price X

Fondo de Servicio Universal X

Eléctrico (FSUE)

ENERGY SAFETY NETS | USING SOCIAL ASSISTANCE MECHANISMS TO CLOSE AFFORDABILITY GAPS FOR THE POOR 20Each of these 25 programs was designed to ad- GRID ELECTRICITY

vance access to affordable modern energy ser-

vices and resulted in benefits for various seg- Connecting customers to the

ments of the population. electricity grid

Twelve of the 25 measures did not target — or Investment in connections to an electricity grid

only implicitly and indirectly targeted — poor has three aspects: (a) investment in distribu-

households. The benefit was intended to reach tion infrastructure (poles, low voltage lines and

them, but the programs were structured in ways transformers), (b) connection to the household

that channelled support via suppliers, subna- (lines to the building and meters) and (c) wiring

tional governments, etc. As such, they do not within the home. Distribution infrastructure is

conform to the definition of an ESN used in this commonly built by utility companies, often with

study. This means that only 13 energy access sup- public funds, making a grid supply available to

port measures examined by the study might be households that can afford to connect. In some

described as ESNs (Table 3). countries, the costs of connection to the distri-

bution network and internal wiring are borne by

There are many lessons to be learned from the the household. However, connection charges can

design and implementation of the 12 public- be a barrier to access for households in lower in-

ly-funded energy access programs (that do not come groups (Golumbeau and Barnes 2013).

qualify as ESN programs). They are included in

the research to highlight the connection between Electrification rates for the six countries are

social protection mechanisms and energy access shown in Figure 1. Three of the six countries—

goals, furthering discourse around solutions to Brazil, Indonesia and Mexico—have achieved, or

enable very poor and marginalized people to ac- almost achieved, universal access to electricity,

cess and use modern energy services. as measured by household connections to an

Table 3

Energy sectorTABLE

support programs reviewed in this study that meet the definition of ESNs

3: ENERGY SECTOR SUPPORT PROGRAMS REVIEWED IN THIS STUDY THAT

MEET THE DEFINITION OF ENERGY SAFETY NETS

CONNECTION CONSUMPTION

Tarifa Social

Brazil Luz para Todos

Bolsa Família (Vale Gás)

Ghana Lifeline electricity tariffs

India PMUY PaHaL

Electricity tariffs

Indonesia Kerosene-to-LPG conversion

LPG subsidy

Kenya Lifeline tariff

Differentiated electricity tariffs

Mexico Oportunidades Energéticas

Subsidized LPG

ENERGY SAFETY NETS | USING SOCIAL ASSISTANCE MECHANISMS TO CLOSE AFFORDABILITY GAPS FOR THE POOR 21electricity supply. In these countries, only house- tion. For practical reasons, the program initially

holds in the most remote and most difficult to focused on areas near to the grid that had a low

reach settlements have still to be connected – score on the Human Development Index. More

households that are amongst the poorest and recently Luz para Todos has targeted communi-

most marginalized in each country. The country ties farthest from the grid as well as low-income

case studies for Brazil, Ghana, Kenya and Mexico families, ethnic minorities and vulnerable popu-

review government initiatives to extend the grid lations living in protected areas such as national

and connect poor and marginalized households parks, extractive reserves and conservation areas

to the grid supply. The approach in each country (Mazzone et al. 2020). Targeting under Luz para

has been different, reflecting their diverse elec- Todos has thus been administrative, including a

trification statuses and contextual challenges. combination of geographic (remoteness from the

grid) and socioeconomic criteria.

Brazil’s Luz para Todos (Light for All) program

was launched in 2003, when 93 percent of the National electrification plans in both Ghana and

country’s population had access to electricity. Kenya have set out to achieve universal access

The program’s aim was to electrify the rural and to electricity by 2030. Ghana’s National Electri-

urban areas that remained without an electricity fication Scheme, 1990−2020 (NES) laid out plans

supply. Luz para Todos, which does not require to electrify all settlements with an adult popula-

a financial contribution from the households it tion of at least 500. In its first two phases, the

connects, had reached over 16 million people by NES focused on district capitals, routes to dis-

2015 – about 7 percent of Brazil’s total popula- trict capitals and settlements within 20 km of the

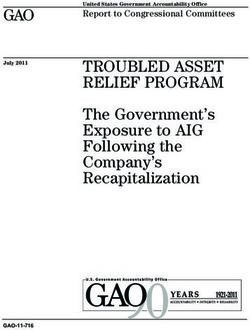

FIGURE 1: ELECTRIFICATION RATES FOR COUNTRIES HIGHLIGHTED IN THIS STUDY, 1990-2017

Figure 1

Electrification rates for countries highlighted in this study, 1990−2017

99.7% 100% BRAZIL

98.9% 98.8% 99% 100% MEXICO

100% 98%

95.8% 99.2%

93.1% 97.1% 97.5% 98.1% INDONESIA

94.4% 94.2%

90% 91.7% 92.6% INDIA

87.5%

86.3% 86% 88%

80%

76.3% 79% GHANA

75.9%

70%

66.9%

67.1%

59.4% 64.2%

60%

63.8% KENYA

54.6%

50%

50.9% 51.4%

48.9%

40% 43.7% 41.6%

34.2%

30%

30.6%

20% 26%

19.2%

10.9% 15.3%

10%

0% 0.29 4.4%

0.29

1990 1995 2000 2005 2010 2015

Source: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/EG.ELC.ACCS.ZS

ENERGY SAFETY NETS | USING SOCIAL ASSISTANCE MECHANISMS TO CLOSE AFFORDABILITY GAPS FOR THE POOR 22grid (Bawakyillenuo 2020). To accelerate electri- nection charge of USD 150, equivalent to 15 per-

fication, the government introduced a Self-Help cent of the total average cost of a connection.

Electrification Program (SHEP) for settlements This connection charge is less than half the USD

that were too small for inclusion in the NES plan. 350 previously charged for connections, yet 10

Under SHEP, communities contribute the costs of times higher than the Slum Electrification Proj-

poles for low voltage lines and meters, and are ect’s connection charge. The USD 150 subsidized

required to ensure that 30 percent of the house- connection charge can be paid upfront or over

holds are wired and ready to be connected. To three years in a monthly instalment of USD 4.16

this extent, targeting was by (community) self-se- included in the household’s electricity bill (EED

lection, but neither program in Ghana targeted Advisory 2020).

poor households.

The investment costs of installing wiring and

Kenya’s electrification strategy has also taken an meters within the home are rarely considered in

untargeted, demand-driven approach, extend- electrification strategies and plans. Indoor wiring

ing distribution infrastructure and providing con- may have to meet specified standards before a

nections to households that requested and could connection can be made, which increases the to-

afford them. However, a degree of targeting was tal cost to the household. To overcome concerns

introduced with the Slum Electrification Project that these costs were a barrier to electricity ac-

(2011−2017). This project was aimed at low-in- cess for low-income households, Kenya Power in-

come households in urban informal settlements, troduced a ‘ready board’, which includes a bulb,

subsidizing the utility’s connection charges for power socket and meter, and relaxed its require-

households that would otherwise be unable to ments around proof of legal residence and rights

afford them. The connection fee charged was of way.

equivalent to about USD 15, which could be paid

upfront or be recovered from prepaid tokens Supporting grid electricity

purchased over a year (EED Advisory 2020). Al- consumption

though the Slum Electrification Project provided

a subsidy to enable low-income households to For low-income households already connected to

connect to the grid, a key policy driver, and one an electricity supply, questions of affordability re-

that was achieved, was increased solvency for main, related to the recurring cost of the electrici-

the national utility, Kenya Power, by reducing the ty they consume. In all six countries the consumer

number of illegal connections. price of electricity is subsidized to some extent, in

the form of a lifeline or social tariff, for consumers

In 2015, Kenya initiated the Last Mile Connec- of small quantities of electricity. Either an increas-

tivity Project (LMCP) with the aim of achieving ing block tariff (IBT) or a volume differentiated tariff

70 percent access by 2017 and universal access (VDT) structure is used with a subsidized tariff for

by 2020 (subsequently revised to 2022 in the low consumption blocks (see Box 1). The number

Kenya National Electrification Strategy that was of subsidized tariff blocks, the quantity of electricity

launched in late 2018). Initially, this program fo- in the minimum block and the level of subsidy are

cused on reaching households within 600 metres different in each country (see Table 2).iii3

of a transformer, installed by LMCP, or at public

buildings, such as schools and health facilities, iii The India case study did not review electricity tariffs. Tariffs, tariff

structures and subsidies are different in each Indian state. Tariff

by the Rural Electrification Agency. Households structures in six states examined by Siyambalapitiya (2018) included

minimum blocks of up to 30 kWh, 40 kWh and 50 kWh per month

connected under LMCP pay a subsidized con- with subsidized tariffs between Rs 1.00 and Rs 2.90 per kWh.

ENERGY SAFETY NETS | USING SOCIAL ASSISTANCE MECHANISMS TO CLOSE AFFORDABILITY GAPS FOR THE POOR 23Box 1: Increasing block tariffs and volume differentiated tariffs

Two types of electricity tariff are commonly used unit price attached. The higher the quantity con-

for quantitative targeting, increasing block tariffs sumed, the higher the unit price for all the elec-

(IBTs) and volume differentiated tariffs (VDTs). tricity consumed. When the unit price for low

quantity consumption is subsidized, consumers

In a block tariff structure, a different price per whose consumption is above the quantity thresh-

unit (USD per kWh) is charged for different old do not benefit.

blocks of electricity consumption. In an IBT, the

unit price increases with each successive block. In some countries, including Mexico, tariff struc-

All consumers benefit when the price of the first tures are hybrids including IBT and VDT for dif-

one or two blocks is subsidized, because those ferent blocks.

initial increments of consumption are charged at

a lower KWh price. In Indonesia, quantitative targeting is partly

based on the power rating of the connection,

A VDT has a different price per unit depending measured in volt-amperes (VA), with a lower unit

on the total quantity consumed. Consumption price (USD per kWh) for consumers with low pow-

levels are divided into blocks, with a different er connections.

Sources: Komives at al. 2005; Beylis and Cunha 2016; Siyambalapitiya 2018.

A premise for targeting through IBTs and VDTs is the likely consumption for one socket and two light

the assumption that poor households generally bulbs. In July 2018, Kenya replaced its IBT tariffs

consume smaller quantities of electricity and that with a VDT structure that included a lifeline block

low-consumption blocks – lifeline blocks – are up to 10 kWh a month (EED Advisory 2020). In No-

sized to meet basic levels of electricity consump- vember 2018, after consumer and business com-

tion. The detailed country case studies show that plaints and intervention by the country’s president,

these assumptions are not always reflected in the first block was adjusted to 0-100 kWh a month

practice. Some low-income electricity consum- and the unit price reduced.iv4 The lifeline block un-

ers in Ghana, for example, consume above the der the previous IBT tariff structure in Kenya had

threshold of the first tariff block (Bawakyillenuo been 0-50 kWh a month. Ghana, on the other hand,

2020), while in Kenya this first tariff block thresh- changed the minimum block in the opposite direc-

old is well above a basic level of electricity con- tion, from 100 kWh to 50 kWh, shortly after the in-

sumption (EED Advisory 2020). Figure 2 shows troduction of the subsidized tariff in 1998. This was

that the size of the subsidized tariff blocks varies based on consideration of the national minimum

widely in the countries highlighted in this study. wage, affordability for rural consumers, the price of

kerosene, and the generation cost of hydropower

In Kenya, the Energy and Petroleum Regulatory Au- (Bawakyillenuo 2020).

thority (formerly the Energy Regulatory Commis-

sion) estimates the subsistence level of electricity

iv Reuters, 31 October 2018 (https://af.reuters.com/article/

consumption to be 10 kWh a month, determined as commoditiesNews/idAFL8N1XB643).

ENERGY SAFETY NETS | USING SOCIAL ASSISTANCE MECHANISMS TO CLOSE AFFORDABILITY GAPS FOR THE POOR 24As shown in Table 4, the levels of subsidy in the consumption exceeds this (Bawakyillenuo 2020;

price per kWh also vary between the countries. In EED Advisory 2020; Sanchez et al. 2020). (The

Brazil, the subsidy is 100 percent for some social effectiveness of this targeting in relation to the

groups, while in Kenya it is about 37 percent for size of the minimum block is discussed in the next

most consumers. Where there is more than one section.)

subsidized block, the higher consumption blocks

receive a lower level of subsidy. Mexico’s mini- In Brazil and Indonesia, quantitative targeting is

mum tariff varies by geography and season, in linked to administrative selection. The Tarifa So-

recognition of different basic energy needs. cial in Brazil is available only to households on the

country’s unified social assistance register (Cadas-

In Ghana, Kenya and Mexico, quantitative tar- tro Único). A higher level of subsidy is available

geting of support for electricity consumption to indigenous groups and to households living

by poor households is, effectively, self-deter- in areas of extreme poverty and in remote rural

mined; households pay the lifeline tariff if their areas, specified by the Ministry of Mines and En-

consumption is below the threshold of the sub- ergy (Mazzone et al. 2020). The national electric-

sidized block, and pay more per unit when their ity utility in Indonesia has begun to use the BDT

FIGURE 2: SUBSIDIZED TARIFF BLOCKS AND

Figure 2 PRICE PER UNIT (US CENTS PPP PER KWH)

Subsidized tariff blocks and price per unit (US cents PPP per kWh)

1ST BLOCK 2ND BLOCK 3RD BLOCK

650 kWh

600 kWh

43

550 kWh

500 kWh

450 kWh

400 kWh

350 kWh

300 kWh

34

250 kWh

27

200 kWh 23

150 kWh

9

100 kWh

15 20

50 kWh 8

9 17

0 kWh

BRAZIL GHANA KENYA MEXICO

Source: Author’s analysis

ENERGY SAFETY NETS | USING SOCIAL ASSISTANCE MECHANISMS TO CLOSE AFFORDABILITY GAPS FOR THE POOR 25Table 4

TABLE 4: CURRENT LEVELS OF SUBSIDIZED TARIFFS AND SUBSIDIES IN FOUR COUNTRIES1

Current levels of subsidized tariffs and subsidies in four countriesiv5

$ PRICE (PPP) LOCAL CURRENCY $ (PPP) EQUIVALENT SUBSIDIZED TARIFF AS

SUBSIDIZED LOCAL CURRENCY

EQUIVALENT MONTHLY MAXIMUM MONTHLY MAXIMUM % OF UNSUBSIDIZED

BLOCKS PRICE PER KWH

PER KWH COST COST TARIFF

0-50 kWh BRL 0.20vi $0.09 BRL 10.00 $4.45 35% or 0%

Brazil 51-100 kWh BRL 0.34 $0.15 BRL 34.00 $15.12 60%

101-220 kWh BRL 0.51 $0.23 BRL 112.20 $49.89 90%

0-50 kWh GHS 0.28 $0.17 GHS 13.85 $8.36 35%

Ghana 51-300 kWh GHS 0.56 $0.34 GHS 166.50 $18.55 69%

301-600 kWh GHS 0.72 $0.43 GHS 432.60 $261.23 90%

Kenya 0-100 kWh KES 10.00vii $0.20 KES 1,000 $19.90 63%

0-75 kWh MXN 0.80 $0.08 MXN 59.70 $5.69 17%

Mexico 76-140 kWh MXN 0.96 $0.09 MXN 134.40 $12.80 21%

141-250 kWh MXN 2.81 $0.27 MXN 703.25 $66.98 62%

Note:Indonesia

Table uses

1 current 2018 PPP exchange rates. Currency figures rounded to two decimal points.

is excluded from thetable because the tariff structure varies by power rating and payment method. The India case study did not examine electricity tariffs.

2

Tariffs in Brazil vary widely so the average tariff paid in 2018 (BRL 0.568 per kWh) has been used to estimate the tariff for each band.

OFF-GRID ELECTRICITY

Excluding sales tax.

3

database of households in the poorest 40 percent

to determine whether consumers are eligible for

the lifeline tariff (Dartanto et al. 2020).viii8 Connecting consumers to off-grid

electricity and supporting ongoing

Consumers on the minimum tariff block may be consumption

required to pay a fixed monthly standing charge

in addition to the per kWh tariff, to cover the fixed In many rural and remote areas distant from ex-

costs of the service provider (e.g. maintenance isting power grid infrastructure, the cost-effec-

and depreciation of infrastructure). These fixed tiveness of supplying electricity through off-grid

charges raise the average price per kWh actually systems is increasingly recognized (IEA 2017; SE-

paid by households and have greater significance forALL 2017). In Brazil, Luz para Todos has pro-

for households with lower levels of consumption. vided off-grid electricity systems in locations

Kenya removed the standing charge from the tar- where this is the most cost-effective approach.

iff structure in 2018 because it was perceived as a These systems have included mini-grids run on

barrier to consumption (EED Advisory 2020). thermal, micro-hydropower, biofuels, wind power

and solar PV generation. To date, Luz para To-

In some countries, a portion of the cost of the dos has installed 3,500 individual solar PV sys-

tariff subsidy is covered by the electricity provid- tems and 17 solar PV mini-grids (Mazzone et al.

er through cross-subsidization within the tariff 2020). The national electrification plans of most

structure where higher tariffs for consumers who countries highlighted in this study now recognize

consume larger quantities of electricity make up these lower-cost off-grid systems to be part of

the shortfall. However, in the case of Mexico, the the solution set for universal access.

cost of the subsidy is provided to the utility di-

rectly from public finance (Sanchez et al. 2020). In Ghana, the ‘Improving Rural Energy Access

v Indonesia is excluded from the table because the tariff struc- through Solar Home Systems’ project, for house-

ture varies by power rating and payment method. The India case

study did not examine electricity tariffs. holds in isolated Volta Lake island communities,

vi Tariffs in Brazil vary widely so the average tariff paid in 2018 (BRL supported the purchase of 7,991 solar lanterns

0.568 per kWh) has been used to estimate the tariff for each

band. and 8,831 solar home systems. The purchase

vii Excluding sales tax.

viii See Box 3 for more information about Indonesia’s BDT register. price of solar products was subsidized by be-

ENERGY SAFETY NETS | USING SOCIAL ASSISTANCE MECHANISMS TO CLOSE AFFORDABILITY GAPS FOR THE POOR 26tween 50 and 60 percent, depending on the women and children breathing that air. However,

product. A loan was available to households to biomass is not easy to displace, since it can often

cover the remaining cost, post subsidy. Ghana’s be foraged for free, and LPG comes at a cost,

National Rooftop Solar Program, with its aim to often considerable. For these reasons, there has

install 200,000 solar home systems, has provided been substantial policy experimentation with

a capital subsidy in the form of free solar pan- ways to close the LPG affordability gap.

els (up to 500 watt-peak), equivalent to about 30

percent of the total cost, including the battery, In Ghana and Kenya, where the proportion of

controls and basic fittings (Bawakyillenuo 2020). the population using clean fuels and technolo-

gies for cooking is lower than in the other four

The approach to enabling households to connect

to off-grid power can be through support to the

suppliers of household solar systems. In Kenya,

for example, the Kenya Off-grid Solar Access

Project (KOSAP), which began in 2018, aims to

install 250,000 household solar systems across 14

marginalized, under-served counties. The project

subsidizes a financing facility to allow companies

to supply solar home systems to households in

the targeted counties. KOSAP also aims to install

151 mini-grids through public-private partner-

ships, which will apply the national tariff struc-

ture, including the lifeline tariff (EED Advisory

2020). Subsidies to suppliers, however, do not fall

within the definition of an ESN.

CLEAN COOKING

Policy initiatives around clean cooking increas-

ingly involve incentives and support for using

LPG, although biomass cookstoves predominate

in many parts of the six countries highlighted in

this study.

Connecting consumers to clean

cooking fuels and technologies

Government clean cooking programs tend to fo-

cus on improving access to LPG, a cleaner-burn-

ing fuel, rather than supporting deployment of

improved biomass cookstove technology. Im-

proved cookstoves (ICS) burn biomass more

cleanly than traditional open fire methods, but

particulate matter is still often generated during

combustion, with harmful health impacts for the

ENERGY SAFETY NETS | USING SOCIAL ASSISTANCE MECHANISMS TO CLOSE AFFORDABILITY GAPS FOR THE POOR 27You can also read