Emergence of Avian Influenza A(H7N9) Virus Causing Severe Human Illness - China, February-April 2013

←

→

Page content transcription

If your browser does not render page correctly, please read the page content below

Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report

Early Release / Vol. 62 May 1, 2013

Emergence of Avian Influenza A(H7N9) Virus Causing Severe Human Illness

— China, February–April 2013

On March 29, 2013, the Chinese Center for Disease Control which exposure information is available, 63 (77%) involved

and Prevention completed laboratory confirmation of three reported exposure to live animals, primarily chickens (76%) and

human infections with an avian influenza A(H7N9) virus not ducks (20%) (3). However, at least three family clusters of two or

previously reported in humans (1). These infections were reported three confirmed cases have been reported where limited human-

to the World Health Organization (WHO) on March 31, 2013, to-human transmission might have occurred (3).

in accordance with International Health Regulations. The cases The median age of patients with confirmed infection is 61 years

involved two adults in Shanghai and one in Anhui Province. All (interquartile range: 48–74); 17 (21%) of the cases are among

three patients had severe pneumonia, developed acute respiratory persons aged ≥75 years and 58 (71%) of the cases are among

distress syndrome (ARDS), and died from their illness (2). males. Only four cases have been confirmed among children; in

The cases were not epidemiologically linked. The detection of addition, a specimen from one asymptomatic child was positive

these cases initiated a cascade of activities in China, including for H7N9 by real-time reverse transcription–polymerase chain

diagnostic test development, enhanced surveillance for new reaction (rRT-PCR). Among the 71 cases for which complete

cases, and investigations to identify the source(s) of infection. data are available, 54 (76%) patients had at least one underlying

No evidence of sustained human-to-human transmission has health condition (3). Most of the confirmed cases involved severe

been found, and no human cases of H7N9 virus infection have respiratory illness. Of 82 confirmed cases for which data were

been detected outside China, including the United States. This available as of April 17, 81 (99%) required hospitalization (3).

report summarizes recent findings and recommendations for Among those patients hospitalized, 17 (21%) died of ARDS or

preparing and responding to potential H7N9 cases in the United multiorgan failure, 60 (74%) remained hospitalized, and only four

States. Clinicians should consider the diagnosis of avian influenza (5%) had been discharged (3).

A(H7N9) virus infection in persons with acute respiratory Chinese public health officials have investigated human

illness and relevant exposure history and should contact their contacts of patients with confirmed H7N9. In a detailed report

state health departments regarding specimen collection and of a follow-up investigation of 1,689 contacts of 82 infected

facilitation of confirmatory testing. persons, including health-care workers who cared for those

patients, no transmission to close contacts of confirmed cases was

Epidemiologic Investigation reported, although investigations including serologic studies are

As of April 29, 2013, China had reported 126 confirmed ongoing (3). In addition, influenza surveillance systems in China

H7N9 infections in humans, among whom 24 (19%) died (1). have identified no sign of increased community transmission of

Cases have been confirmed in eight contiguous provinces in this virus. Seasonal influenza A(pH1N1) and influenza B viruses

eastern China (Anhui, Fujian, Henan, Hunan, Jiangsu, Jiangxi, continue to circulate among persons in areas where H7N9 cases

Shandong, and Zhejiang), two municipalities (Beijing and have been detected, and the Chinese Centers for Disease Control

Shanghai), and Taiwan (Figure 1). Illness onset of confirmed cases and Prevention has reported that rates of influenza-like illness

occurred during February 19–April 29 (Figure 2). The source of are consistent with expected seasonal levels.

the human infections remains under investigation. Almost all CDC, along with state and local health departments, is

confirmed cases have been sporadic, with no epidemiologic link continuing epidemiologic and laboratory surveillance for

to other human cases, and are presumed to have resulted from influenza in the United States. On April 5, 2013, CDC

exposure to infected birds (3,4). Among 82 confirmed cases for requested state and local health departments to initiate enhanced

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services

Centers for Disease Control and PreventionEarly Release

FIGURE 1. Location of confirmed cases of human infection (n = 126) with avian influenza A(H7N9) virus and deaths (n = 24) — China,

February 19–April 29, 2013

A

No. of cases

1 Beijing North

Proportion of deaths

! Korea

4

N

! City with H7N9 case reported

2 South

I

" City with a poultry market, farm,

Shandong Korea

or household with an animal

H

positive for H7N9 27

! "

!

( !

Province with confirmed cases !

C

Henan Jiangsu

"

!

!

( !

4

!

! "

Anhui ! ! !

A " "

!

( " Shanghai

! ! !!"

!

!

!"

!

!

(

N

"

!

( ! 33

I

4

"

!

(

!!

C H 1

Hunan

!

!

Jiangxi

"

!

East China Sea

! Fujian 46

5 Zhejiang

2

!

! !

1

Taiwan

Vietnam

surveillance for H7N9 among symptomatic patients who had Laboratory Investigation

returned from China in the previous 10 days (5). As of April As of April 30, 2013, Chinese investigators had posted 19

29, 37 such travelers had been reported to CDC by 18 states. partial or complete genome sequences from avian influenza

Among those 37 travelers, none were found to have infection A(H7N9) viruses to a publicly available database at the Global

with H7N9; seven had an infection with a seasonal influenza Initiative on Sharing All Influenza Data (http://www.gisaid.

virus, one had rhinovirus, one had respiratory syncytial virus, org). Sequences are from viruses infecting 12 humans and five

and 28 were negative for influenza A and B. Among 31 cases birds, and two are from viruses collected from the environment.

with known patient age, seven travelers were agedEarly Release

FIGURE 2. Number of confirmed cases of human infection with avian influenza A(H7N9) virus (N = 126), by date of onset of illness and province,

municipality, or area — China, February 19–April 29, 2013

10

Hunan (1)

9

Fujian (2)

8 Jiangxi (5)

Taiwan (1)

7

Shandong (2)

6 Henan (4)

No. of cases

Beijing (1)

5

Zhejiang (46)

4 Jiangsu (27)

Anhui (4)

3

Shanghai (33)

2

1

0

18 20 22 24 26 28 2 4 6 8 10 12 14 16 18 20 22 24 26 28 30 2 4 6 8 10 12 14 16 18 20 22 24 26 28 2 4

Feb Mar Apr May

Date of illness onset

CDC’s Influenza Division Laboratory has received two H7N9 Immediately after notification by Chinese health authorities

influenza viruses (A/Anhui/1/2013 and A/Shanghai/1/2013) of the H7N9 cases, CDC began development of a new H7

from the WHO Collaborating Centre for Reference and diagnostic test for use with the existing CDC influenza rRT-

Research on Influenza at the Chinese Center for Disease PCR kit. This test has been designed to diagnose infection with

Control and Prevention (Figure 3). Full characterization of Eurasian H7 viruses, including the recently recognized China

these viruses is ongoing; however, studies to date have shown H7N9 and other representative H7 viruses from Southeast

robust viral replication in eggs, cell culture, and the respiratory Asia and Bangladesh. On April 22, this new H7 test was

tract of animal models (ferrets and mice). At higher inoculum cleared by the Food and Drug Administration for use as an in

doses (106–104 plaque forming units), the virus shows some vitro diagnostic test under an Emergency Use Authorization,

lethality for BALB/c mice. thus allowing distribution and use of the test in the United

Laboratory testing of the A/Anhui/1/2013 virus isolate at the States. The CDC H7 rRT-PCR test is now available to all

Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention, CDC, and qualified U.S. public health and U.S. Department of Defense

other laboratories indicates that this virus is susceptible to oseltamivir laboratories and WHO-recognized National Influenza Centers

and zanamivir, the two neuraminidase-inhibiting (NAI) antiviral globally and can be ordered from the Influenza Reagent

drugs licensed in the United States for treatment of seasonal Resource (http://www.influenzareagentresource.org). Access

influenza. The genetic sequence of one of the publicly posted H7N9 to the CDC H7 rRT-PCR test protocol is available at http:/

viruses (A/Shanghai/1/2013) contains a known marker of NAI www.cdc.gov/flu/clsis. Guidance on appropriate biosafety

resistance (2). The clinical relevance of this genetic change is under levels for working with the virus and suspect clinical specimens

investigation but it serves as a reminder that resistance to antiviral is being developed.

drugs can occur spontaneously through genetic mutations or emerge

during antiviral treatment. The genetic sequences of all viruses tested Animal Investigation and U.S. Animal Health

showed a known marker of resistance to the adamantanes, indicating Preparedness Activities

that, although these drugs (amantadine and rimantadine) are As of April 26, reports from the China Ministry of Agriculture

licensed for use in the United States, they should not be prescribed indicate that 68,060 bird and environmental specimens have

for patients with H7N9 virus infection. been tested, 46 (0.07%) were confirmed H7N9-positive by

MMWR / May 1, 2013 / Vol. 62 3Early Release

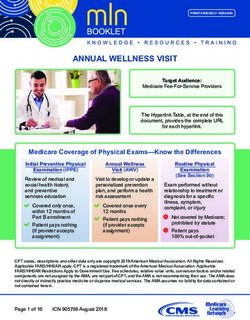

culture (7). The H7N9 virus has been confirmed in chickens, FIGURE 3. Electron micrograph image of influenza A/Anhui/1/2013

ducks, pigeons (feral and captive), and environmental samples (H7N9), showing spherical virus particles characteristic of influenza

virions — April 15, 2013

in four of the eight provinces and in Shanghai municipality

(Figure 1). As of April 17, approximately 4,150 swine and

environmental samples from farms and slaughterhouses were

reported to have been tested; all swine samples were negative.†

The China Ministry of Agriculture is jointly engaged with

the National Health and Family Planning Commission in

conducting animal sampling to assist in ascertaining the extent

of the animal reservoir of the H7N9 virus. Sampling of animals

is concentrated in the provinces and cities where human cases

have been reported. Poultry markets in Shanghai and other

affected areas have been closed temporarily, and some markets

might remain closed.

The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) has set up a

Situational Awareness Coordination Unit with a core team of

subject matter experts and other USDA representatives, including

the Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service (APHIS), the

Agricultural Research Service (ARS), the Food Safety and

Inspection Service, and the Foreign Agricultural Service.

USDA and CDC are working collaboratively to understand the

epidemiology of H7N9 infections among humans and animals

in China. To date, no evidence of this strain of avian influenza

Photo/CDC

A(H7N9) virus has been identified in animals in the United

States. The U.S. government does not allow importation of live

birds, poultry, and hatching eggs from countries affected with mapping study to help identify virus isolates that could be

highly pathogenic avian influenza. The current U.S. surveillance used to develop a vaccine for poultry if needed.

program for avian influenza in commercial poultry actively tests

Reported by

for any form of avian influenza virus and would be expected to

detect avian influenza A(H7N9) if it were introduced to the China–US Collaborative Program on Emerging and Re-emerging

United States. A screening test for avian influenza is available Diseases, Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention and

from the National Animal Health Laboratory Network and the CDC, Beijing, China. US Dept of Agriculture. Div of Global

National Veterinary Services Laboratories (NVSL), which can Migration and Quarantine, National Center for Emerging and

be used together with confirmatory tests at NVSL to detect Zoonotic Infectious Diseases; Div of State and Local Readiness,

this strain of avian influenza A(H7N9) in poultry and wild Office of Public Health Preparedness and Response; Influenza

bird samples. Coordination Unit, Office of Infectious Diseases; Influenza Div,

APHIS is working with the U.S. Department of the Interior Immunization Svcs Div and Office of the Director, National

to prepare a pathway assessment, using current literature, Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases; CDC.

to assess evidence for potential movement of Eurasian Corresponding contributor: Daniel Jernigan, MD, djernigan@

avian influenza viruses into North America via wild birds. cdc.gov, 404-639-2621.

USDA is conducting animal studies to characterize the virus

Editorial Note

pathogenicity and transmission properties of this virus in avian

and swine species. Preliminary results from studies performed After recognition of the first human infections with avian

on poultry by ARS in high-containment laboratories indicate influenza A(H7N9), Chinese public health officials and

that chickens and quail are showing no signs of illness but scientists rapidly reported information about identified cases

are shedding avian influenza A(H7N9) virus in these studies and posted whole virus genome sequences for public access.

(Southeast Poultry Research Laboratory, unpublished data; During April, laboratory and surveillance efforts quickly

2013). ARS also has completed a preliminary antigenic characterized the virus, developed diagnostic tests, generated

candidate vaccine viruses, identified cases and contacts,

† Additional information available at http://www.chinacdc.cn. described clinical illness, evaluated animal sources of infection,

4 MMWR / May 1, 2013 / Vol. 62Early Release

relatively few H7N9 virus–infected birds have been detected.

What is already known on this topic?

During the month after recognition of H7N9, increasing

Human infections with a new avian influenza A(H7N9) virus numbers of infected humans have been identified in additional

were first reported to the World Health Organization on March

31, 2013. Available information suggests that poultry is the

areas of eastern China, suggesting possible widespread occurrence

source of infection in most cases. Although no evidence of of H7N9 virus in poultry. Enhanced surveillance in poultry and

sustained (ongoing) human-to-human spread of this virus has other birds in China is needed to better clarify the magnitude

been identified; small family clusters have occurred where of H7N9 virus infection in birds and to better target control

human-to-human spread cannot be conclusively ruled out. measures for preventing further transmission.

What is added by this report? The emergence of this previously unknown avian influenza

By April 29, a total of 126 H7N9 human infections (including 24 A(H7N9) virus as a cause of severe respiratory disease and death

deaths) had been confirmed. Although a number of travelers in humans raises numerous public health concerns. First, the

returning to the United States from affected areas of China have virus has several genetic differences compared with other avian

developed influenza-like symptoms and been tested for H7N9

infection, no cases have been detected in the United

influenza A viruses. These genetic changes have been evaluated

States. Laboratory and epidemiologic evidence suggest that previously in ferret and mouse studies with other influenza

this H7N9 virus is more easily transmitted from birds to humans A viruses, including highly pathogenic avian influenza

than other avian influenza viruses. Candidate vaccine viruses A(H5N1) virus, and were associated with respiratory droplet

are being evaluated and human clinical vaccine trials are transmission, increased binding of the virus to receptors on cells

forthcoming, but no decision has been made regarding a U.S.

in the respiratory tract of mammals, increased virulence, and

H7N9 vaccination program.

increased replication of virus (5). Epidemiologic investigations

What are the implications for public health practice?

have not yielded conclusive evidence of sustained human-to-

State and local health authorities are encouraged to review human H7N9 virus transmission; however, further adaptation

pandemic influenza preparedness plans to ensure response

readiness. Clinicians in the United States should consider H7N9

of the virus in mammals might lead to more efficient and

virus infection in recent travelers from China who exhibit signs sustained transmission among humans. Second, human illness

and symptoms consistent with influenza. Patients with H7N9 with H7N9 virus infection, characterized by lower respiratory

virus infection (laboratory-confirmed, probable, or under inves- tract disease with progression to ARDS and multiorgan

tigation) should receive antiviral treatment with oral oseltamivir failure, is significantly more severe than in previously reported

or inhaled zanamivir as early as possible.

infection with other H7 viruses. Over a 2-month period, 24

deaths (19% of cases) have occurred, compared with only

and implemented control measures. Preliminary investigations one human death attributed to other subtypes of H7 virus

of patients and close contacts have not revealed evidence reported previously. Third, H7N9-infected poultry are the

of sustained human-to-human transmission, but limited likely source of infection in humans, but might not display

nonsustained human-to-human H7N9 virus transmission illness symptoms. Consequently, efforts to detect infection

could not be excluded in a few family clusters (3). Despite in poultry and prevent virus transmission will be challenging

these efforts, many questions remain. for countries lacking a surveillance program for actively

The epidemiology of H7N9 infections in humans so far identifying low-pathogenicity avian influenza in poultry. In the

reveals that most symptomatic patients are older (median age: United States, an active surveillance program is in place that

61 years), most are male (71%), and most had underlying routinely identifies low–pathogenicity viruses. If this newly

medical conditions. In comparison, among the 45 avian recognized H7N9 is detected, public health and animal health

influenza A(H5N1) cases reported from China during 2003– officials should identify means for monitoring the spread of

2013, the median patient age is 26 years (8). This difference asymptomatic H7N9 virus infections in poultry and maintain

in median age might represent actual differences in exposure vigilance for virus adaptation and early indications of potential

or susceptibility to H7N9 virus infection and clinical illness, human-to-human transmission.

or preliminary H7N9 case identification approaches might Beginning in early April 2013, CDC and U.S. state and

be more likely to capture cases in older persons. Ongoing local health departments initiated enhanced surveillance for

surveillance and case-control studies are needed to better H7N9 virus infections in patients with a travel history to

understand the epidemiology of H7N9 virus infections, and affected areas. A new CDC influenza rRT-PCR diagnostic test

to determine whether younger persons might be more mildly has been cleared by the Food and Drug Administration under

affected, and therefore less likely to be detected via surveillance. an Emergency Use Authorization and is being distributed to

Available animal testing data and human case histories indicate public health laboratories to assist in evaluating these suspect

that most human patients have poultry exposure; however,

MMWR / May 1, 2013 / Vol. 62 5Early Release

cases. Clinicians should consider the possibility of H7N9 virus United States, CDC recommends that local authorities and

infection in patients with illness compatible with influenza who preparedness programs take time to review and update their

1) have traveled within ≤10 days of illness onset to countries pandemic influenza vaccine preparedness plans because it

where avian influenza A(H7N9) virus infection recently has been could take several months to ready a vaccination program, if

detected in humans or animals, or 2) have had recent contact one becomes necessary. CDC also recommends that public

(within ≤10 days of illness onset) with a person confirmed to health agencies review their overall pandemic influenza plans to

have infection with avian influenza A(H7N9) virus. Because of identify operational gaps and to ensure administrative readiness

the potential severity of illness associated with avian influenza for an influenza pandemic. Continued collaboration between

A(H7N9) virus infection, CDC recommends that all H7N9 the human and animal health sectors is essential to better

patients (confirmed, probable, or under investigation for understand the epidemiology and ecology of H7N9 infections

H7N9 infection) receive antiviral treatment with oseltamivir or among humans and animals and target control measures for

zanamivir as early as possible. Treatment should be initiated even preventing further transmission.

>48 hours after onset of illness. Guidance on testing, treatment,

References

and infection control measures for H7N9 cases has been posted

to the CDC H7N9 website (9). 1. World Health Organization. Global Alert and Response (GAR): human

infection with influenza A(H7N9) virus in China. Geneva, Switzerland:

On April 5, CDC posted a Travel Notice on the Traveler’s World Health Organization; 2013. Available at http://www.who.int/csr/

Health website informing travelers and U.S. citizens living in don/2013_04_01/en/index.html.

China of the current H7N9 cases in China and reminding 2. Gao R, Cao B, Hu Y, et al. Human infection with a novel avian-origin influenza

A (H7N9) virus. N Engl J Med 2013; April 11 [Epub ahead of print].

them to practice good hand hygiene, follow food safety 3. Li Q, Zhou L, Zhou M, et al. Preliminary report: epidemiology of the

practices, and avoid contact with animals (10). CDC and avian influenza A (H7N9) outbreak in China. N Engl J Med 2013;

WHO do not recommend restricting travel to China at this April 24 [Epub ahead of print].

4. CDC. CDC health advisory: human infections with novel influenza A

time. If travelers to China become ill with influenza signs or (H7N9) viruses. Atlanta, GA: US Department of Health and Human

symptoms (e.g., fever, cough, or shortness of breath) during Services, CDC, Health Alert Network; 2013. Available at http://

or after returning from their visit, they should seek medical emergency.cdc.gov/han/han00344.asp.

treatment and inform their doctor about their recent travel. 5. Uyeki TM, Cox NJ. Global concerns regarding novel influenza A (H7N9)

virus infections. N Engl J Med 2013; April 11 [Epub ahead of print].

Travelers should continue to visit www.cdc.gov/travel or follow 6. Chen Y, Liang W, Yang S, et al. Human infections with the emerging avian

@CDCtravel on Twitter for up-to-date information about influenza A H7N9 virus from wet market poultry: clinical analysis and

CDC’s travel recommendations. characterisation of viral genome. Lancet 2013; April 25 [Epub ahead of print].

7. Ministry of Agriculture of the People’s Republic of China. No H7N9

Given the number and severity of human H7N9 illnesses virus found in poultry farm samples. Beijing, China: Ministry of

in China, CDC and its partners are taking steps to develop a Agriculture; 2013. Available at http://english.agri.gov.cn/news/

H7N9 candidate vaccine virus. Past serologic studies evaluating dqnf/201304/t20130427_19537.htm.

8. World Health Organization. Update on human cases of influenza at the

immune response to H7 subtypes of influenza viruses have human – animal interface, 2012. Wkly Epidemiol Rec 2013;88:137–44).

shown no existing cross-reactive antibodies in human sera. In 9. CDC. Avian influenza A (H7N9) virus. Atlanta, GA: US Department

addition, CDC has activated its Emergency Operations Center of Health and Human Services, CDC; 2013. Available at http://www.

to coordinate efforts. In the United States, planning for H7N9 cdc.gov/flu/avianflu/h7n9-virus.htm.

10. CDC. Travelers’ health. Watch: level 1, practice usual precautions—avian

vaccine clinical trials is under way. Although no decision has flu (H7N9). Atlanta, GA: US Department of Health and Human

been made to initiate an H7N9 vaccination program in the Services, CDC; 2013. Available at http://wwwnc.cdc.gov/travel/notices/

watch/avian-flu-h7n9.htm.

6 MMWR / May 1, 2013 / Vol. 62You can also read