Dissolution and Calling of Parliament Bill 2021-22

←

→

Page content transcription

If your browser does not render page correctly, please read the page content below

By Richard Kelly

30 June 2021

Dissolution and Calling of

Parliament Bill 2021-22

Summary

1 Introduction

2 Fixed-term Parliaments Act 2011

3 The Bill

4 Issues raised by the Bill: prerogative powers

5 Issues raised by the Bill: the ouster clause

6 Dissolution principles

7 Other issues

commonslibrary.parliament.ukNumber 9267 Dissolution and Calling of Parliament Bill 2021-22

Image Credits

Chamber-070 by UK Parliament image. Licensed under CC BY 2.0 / image

cropped.

Disclaimer

The Commons Library does not intend the information in our research

publications and briefings to address the specific circumstances of any

particular individual. We have published it to support the work of MPs. You

should not rely upon it as legal or professional advice, or as a substitute for

it. We do not accept any liability whatsoever for any errors, omissions or

misstatements contained herein. You should consult a suitably qualified

professional if you require specific advice or information. Read our briefing

‘Legal help: where to go and how to pay’ for further information about

sources of legal advice and help. This information is provided subject to the

conditions of the Open Parliament Licence.

Feedback

Every effort is made to ensure that the information contained in these publicly

available briefings is correct at the time of publication. Readers should be

aware however that briefings are not necessarily updated to reflect

subsequent changes.

If you have any comments on our briefings please email

papers@parliament.uk. Please note that authors are not always able to

engage in discussions with members of the public who express opinions

about the content of our research, although we will carefully consider and

correct any factual errors.

You can read our feedback and complaints policy and our editorial policy at

commonslibrary.parliament.uk. If you have general questions about the work

of the House of Commons email hcenquiries@parliament.uk.

2 Commons Library Research Briefing, 30 June 2021Dissolution and Calling of Parliament Bill 2021-22

Contents

Summary 5

What will the Bill change? 5

Fixed-term Parliaments Act 2011 5

Scrutiny of the draft Bill 6

1 Introduction 7

2 Fixed-term Parliaments Act 2011 8

2.1 Overview of the Act 8

Intervals between ordinary elections 8

Early general elections 8

Dissolution of Parliament and calling elections 9

Operation of the Act 10

2.2 Review of the FTPA 11

Draft Bill published 11

Review of the Act 12

Scrutiny of the draft Bill 12

Government response to the review 14

Previous reviews of the FTPA 14

3 The Bill 15

Clauses 1 and 2 15

Clause 3 15

Clause 4 16

Clause 5 17

Clause 6 18

The Schedule 18

4 Issues raised by the Bill: prerogative powers 22

4.1 The prerogative is exercisable again 22

3 Commons Library Research Briefing, 30 June 2021Dissolution and Calling of Parliament Bill 2021-22

4.2 What is the power? 24

4.3 Conventions, political controversy and the Monarch 25

When might a dissolution be refused? 27

How can Executive power be checked? 28

4.4 Should Parliament have a say? 29

5 Issues raised by the Bill: the ouster clause 31

5.1 The ouster clause 31

Is the prerogative of dissolution susceptible to judicial review? 31

5.2 Is the ouster clause needed at all? 32

Safeguards 33

5.3 Drafting of the ouster clause 34

6 Dissolution principles 36

7 Other issues 39

7.1 Maximum term of a Parliament 39

7.2 The confidence convention 40

7.3 The election timetable 43

4 Commons Library Research Briefing, 30 June 2021Dissolution and Calling of Parliament Bill 2021-22 Summary The Dissolution and Calling of Parliament Bill 2021-22 [Bill 8 of 2021-22] was introduced in the House of Commons on 12 May 2021. The second reading has been scheduled for 6 July 2021. The Bill would repeal of the Fixed-term Parliaments Act 2011 and confirms that the maximum term of a Parliament (rather than the period between general elections) shall be five years. The Bill’s Explanatory Notes confirm that its effect is to “enable Governments, within the life of a Parliament, to call a general election at the time of their choosing”. It envisages that there will not be a role for Parliament in deciding when general elections are held. What will the Bill change? Before the Fixed-term Parliaments Act 2011 (FTPA), the Monarch used personal prerogative powers to dissolve a Parliament, before it expired, and call a new Parliament. Under the FTPA, Parliament was dissolved in accordance with statute, not the prerogative. The Bill states that the powers that were exercisable “by virtue of” the royal prerogative are exercisable again. The Bill confirms that the timetable for the election of a new Parliament is triggered by the dissolution of the old Parliament. The Bill also states that questions relating to the use of the powers, preliminary work on dissolution and the extent of the powers cannot be questioned by the courts. Fixed-term Parliaments Act 2011 The FTPA was passed by the Coalition Government and fixed the period between ordinary elections at five years. It allowed the House of Commons to trigger early elections in two ways: by at least two thirds of all MPs voting for an early parliamentary general election, or if a government was not confirmed in office within two weeks of a vote of no confidence. The prerogative power of the Monarch to call general elections was removed by the FTPA. Arrangements for a statutory review of the FTPA had to be made by the Prime Minister between June and November 2020. In its manifesto for the December 2019 General Election, the Conservative Party said that it would “get rid of” the FTPA, as it had “led to paralysis at a 5 Commons Library Research Briefing, 30 June 2021

Dissolution and Calling of Parliament Bill 2021-22 time the country needed decisive action”. The Labour Party’s manifesto also committed to repeal the Act, saying it had “ stifled democracy and propped up weak governments”. Scrutiny of the draft Bill A Joint Committee was appointed to undertake the statutory review of the FTPA in November 2020. It also scrutinised the Draft Fixed-term Parliaments Act 2011 (Repeal) Bill, which was published on 1 December 2020. Its report was published on 24 March 2021. The Joint Committee examined the Government’s approach to legislating for a return to the pre-FTPA position, whereby early dissolutions are approved by the Monarch, not triggered by the House of Commons. It considered whether the Monarch would be brought into political controversy and whether the Monarch would be able to refuse a request for a dissolution when it was inappropriate. It also considered whether provisions to prevent the courts from questioning decisions about dissolving and calling parliaments were proper, desirable and appropriately drafted. It recommended that the Government should consider a more limited provision. A minority of the Joint Committee’s members thought retaining a vote to dissolve Parliament in the House of Commons would improve the Government’s proposals. By the operation of Article 9 of the Bill of Rights 1689, this would prevent the courts questioning decisions about dissolution. It would also mean that the Monarch would be protected from political controversy. Overall, the Joint Committee was satisfied that the drafting of the Bill was “sufficiently clear” to give effect to the Government’s intention of returning to the pre FTPA constitutional position, “in substance if not necessarily in form”. The potential legal uncertainty over the source (prerogative or statute) of the power to dissolve Parliament would likely only be relevant if the question of dissolution was considered by the courts. The Government’s response to the Joint Committee’s report was published on 12 May 2021, when the Dissolution and Calling of Parliament Bill 2021-22 was introduced. 6 Commons Library Research Briefing, 30 June 2021

Dissolution and Calling of Parliament Bill 2021-22

1 Introduction

The Dissolution and Calling of Parliament Bill 2021-22 was introduced by the

Government on 12 May 2021. It would repeal the Fixed-term Parliaments Act

2011 (the FTPA) and provides that prerogative powers used to dissolve

Parliament and to call a new Parliament, used prior to the 2011 Act, are

exercisable again. It would limit the maximum length of a parliament to five

years, running from when it first meets.

This briefing sets out and explains the current constitutional framework that

governs the dissolving of Parliament and the holding of general elections,

under the Fixed-term Parliaments Act 2011 (see section 2).

Section 3 explains what the Dissolution and Calling of Parliament Bill 2021-22

will do if enacted.

Sections 4 and 5 discuss the issues raised by the Government’s approach to

return the system of calling elections that operated before the FTPA. First, the

prerogative power of dissolving Parliament is discussed and then the ‘ouster

clause’ is considered.

Section 6 discusses dissolution principles and section 7 considers other issues

raised by the Bill and the debate around the Bill, including the conventions

relating to how the House of Commons expresses confidence in a government.

Explanatory Notes to the Bill were also published on 12 May 2021.

Second reading is scheduled for 6 July 2021.

7 Commons Library Research Briefing, 30 June 2021Dissolution and Calling of Parliament Bill 2021-22

2 Fixed-term Parliaments Act 2011

2.1 Overview of the Act

Intervals between ordinary elections

The Fixed-term Parliaments Act 2011 (FTPA) set a maximum time period

between elections, rather than the actual length of the Parliament: an

ordinary general election would never take place more than five years after

the last election and polling day would take place on the first Thursday in

May. 1 It also gave the House of Commons a statutory role in the early

dissolution of Parliament.

Until the passage of the FTPA, the legislation governing the maximum term of

the UK Parliament was the Septennial Act 1715, as amended by the Parliament

Act 1911. This set the maximum length of a Parliament at five years (from the

day on which it was summoned to meet after an election to dissolution).

Unless they expired, Parliaments were ended by the Monarch dissolving them

– using prerogative powers – following a request from the Prime Minister. No

Parliament between 1911 and 2011 lasted the full five years (see Table 1, in

section 3).

Early general elections

The FTPA makes provision for “early” (as opposed to “ordinary”) general

elections to take place. Section 2 provides for early general elections when

either of the following conditions is met:

• if a motion for an early general election is agreed either by at least two-

thirds of the whole House of Commons (including vacant seats), i.e. 434

Members out of 650, or without division; or

• if a statutory motion of no confidence is passed and 14 days pass

without the Commons adopting a statutory motion of confidence. 2

1

Section 1 set the date of the subsequent UK general election as Thursday 7 May 2015 (following the

general election on 6 May 2010). Thereafter, polling days for ordinary general elections would be on

the first Thursday in May in the fifth calendar year, after the preceding election (unless an early

election was held between May and December, when the ordinary election would be in the fourth

calendar year after the election)

2

The Cabinet Manual (para 2.19) states that: “Under the Fixed-term Parliaments Act 2011, if a

government is defeated on a motion that ‘this House has no confidence in Her Majesty’s Government’,

there is then a 14-day period during which an alternative government can be formed from the House

8 Commons Library Research Briefing, 30 June 2021Dissolution and Calling of Parliament Bill 2021-22

Dissolution of Parliament and calling elections

The FTPA removed the prerogative power to dissolve Parliament. Parliament

is dissolved at the beginning of the 25th working day before polling day. 3

In evidence to the Public Administration and Constitutional Affairs Committee

(PACAC), Lord O’Donnell, a former Cabinet Secretary, Sir Stephen Laws, a

former First Parliamentary Counsel, and Mark Harper, the Minister who had

piloted the Bill through the House of Commons, confirmed that the intention

had been to abolish the prerogative. Sir Stephen said:

Section 3(2) says: “Parliament cannot otherwise be dissolved”. That

comes as close as I can see to abolishing it … 4

Before the passage of the Act, the dissolution of Parliament and the date of

meeting of the new Parliament were determined by proclamation. Although

separate proclamations dissolving the old Parliament and summoning the

new Parliament could be issued, in practice a single proclamation was

issued. 5

The Act specifies that once Parliament has been dissolved, “Her Majesty may

issue the proclamation summoning the new Parliament”. In 2015, following

the dissolution of Parliament on 30 March (by Act), a Royal Proclamation was

issued on 31 March calling a new Parliament to meet on 18 May 2015. 6

Under the FTPA, the responsibility for sealing and issuing the writs for the

election is a statutory responsibility of the Lord Chancellor and the Secretary

of State for Northern Ireland. 7

Previously, following the proclamation dissolving Parliament and summoning

a new Parliament, an Order in Council was made requiring the issue of writs

for a parliamentary election of a new Parliament. 8 This practice was

of Commons as presently constituted, or the incumbent government can seek to regain the

17

confidence of the House. If no government can secure the confidence of the House of Commons

during that period, through the approval of a motion that ‘this House has confidence in Her Majesty’s

Government’, a general election will take place.”

3

Section 3 of the Act had provided for a 17 working day election timetable, not including the day of

dissolution, but that was extended to 25 working days by section 14 of the Electoral Registration and

Administration Act 2013. See Library Standard Note 6574, Timetable for the UK Parliamentary general

election for further details

4

Public Administration and Constitutional Affairs Committee, The Fixed-term Parliaments Act 2011 –

Oral Evidence, 24 April 2020, Q15, see also Q14; Public Administration and Constitutional Affairs

Committee, The Fixed-term Parliaments Act 2011 – Oral Evidence, 21 July 2020, Q138

5

For example, “Dissolution Proclamation”, The London Gazette, Supplement No 1, 12 April 2010. The

Joint Committee noted an instance in 1713 when separate proclamations were issued to dissolve one

Parliament and call its successor (Joint Committee on the Fixed-term Parliament Act, Report, 24

March 2021, HC 1046 2019-21, para 180)

6

“Proclamation: By the Queen a Proclamation for Declaring the Calling of a New Parliament –

Elizabeth R”, The Gazette, 31 March 2015

7

Fixed-term Parliaments Act 2011 (chapter 14), section 3(3)

8

Justice Committee, Constitutional processes following a general election, 29 March 2010, HC 396

2009-10, Ev 24 [para 7 of Chapter 6 of the Proposed Cabinet Manual]

9 Commons Library Research Briefing, 30 June 2021Dissolution and Calling of Parliament Bill 2021-22

unchanged by the FTPA, the Parliamentary Election Rules state that “Writs for

parliamentary elections shall continue to be sealed and issued in accordance

with the existing practice of the office of the Clerk of the Crown”. 9

Operation of the Act

The general election on 7 May 2015 was preceded by the dissolution of the

2010 Parliament 25 working days earlier on 30 March 2015, in accordance with

the FTPA.

On 18 April 2017, Prime Minister Theresa May announced that she planned to

call an early election which would be held on 8 June 2017. On 19 April 2017,

the House of Commons supported Mrs May’s motion “That there shall be an

early parliamentary general election” by 522 votes to 13 meaning that more

than two thirds of MPs were in favour. 10 A proclamation, announcing that the

general election would take place on 8 June 2017, was issued on 25 April

2017, 11 and Parliament was accordingly dissolved on 3 May 2017.

On 16 January 2019, the House rejected a statutory no confidence motion,

tabled by the Leader of the Opposition, by 325 votes to 306. 12

In the autumn of 2019, three unsuccessful attempts were made to hold an

early general election under the FTPA. Although the House of Commons

agreed to all three motions, none secured the required two thirds of MPs in

favour:

• on 4 September 2019, a motion was agreed to by 298 votes to 59 but

without the majority required under the Act. 13

• on 9 September 2019, a motion was agreed by 293 votes to 46 but

without the majority required under the Act. 14

• on 28 October 2019, a motion was agreed to by 299 votes to 70 but

without the majority required under the Act. 15

Subsequently, the Government introduced the Early Parliamentary General

Election Bill 2019 in order to set the date of the next general election for 12

December 2019. 16 The Bill was introduced and passed all its Commons stages

on 29 October 2019. It was given a third reading by 438 votes to 20 17 and it

received Royal Assent on 31 October. It treated the election date as if it had

been set in accordance with the FTPA, so Parliament was dissolved on 6

9

Representation of the People Act 1983 (chapter 2), Schedule 1, para 3

10

BBC News, Theresa May to seek general election on 8 June, 18 April 2017; HC Deb 19 April 2017 cc681-

712

11

“Proclamations”, The Gazette, 25 April 2017

12

HC Deb 19 January 2019 cc1171-1273

13

HC Deb 4 September 2019 cc291-315

14

HC Deb 9 September 2019 cc616-639

15

HC Deb 28 October 2019 cc54-79

16

A Library Insight described the provisions of the Bill, What does the Early Parliamentary General

Election Bill do?, 29 October 2019

17

HC Deb 29 October 2019 cc328-330

10 Commons Library Research Briefing, 30 June 2021Dissolution and Calling of Parliament Bill 2021-22

November 2019; and the following election is scheduled to be held on the first

Thursday in May 2024. 18

2.2 Review of the FTPA

The FTPA required the Prime Minister to make arrangements for a committee

to carry out a review of the Act, between June and November 2020.

Before that review was initiated both the Conservative Party and Labour Party

had called for the Act to be repealed in their manifestos for the 2019 General

Election. 19

In November 2020, the Government brought forward proposals to establish a

Joint Committee to undertake the statutory review of the Act and to consider

the draft Fixed-term Parliaments Act 2011 (Repeal) Bill, which was published

shortly after the Committee was established.

The Joint Committee’s report was published on 24 March 2021. 20 In

accordance with its remit it undertook both the statutory review of the 2011

Act and a review of the Government’s draft bill.

Draft Bill published

The Government’s Draft Fixed-term Parliaments Act 2011 (Repeal) Bill was

published on 1 December 2020. 21 The draft bill provided for the repeal of the

2011 Act; confirms that the maximum term of a Parliament (rather than the

period between general elections) shall be five years; and contains an

express provision to restore the prerogative power to dissolve Parliament.

The draft Bill also stated that questions relating to the use of the powers,

preliminary work on dissolution and the extent of the powers are non-

justiciable. 22

The Explanatory Notes confirmed that the effect of the draft bill was to

“enable Governments, within the life of a Parliament, to call a general

election at the time of their choosing“. 23 It envisaged that there will not be a

role for Parliament.

18

Early Parliamentary General Election Act 2019 (chapter 29)

19

“We will get rid of the Fixed Term Parliaments Act – it has led to paralysis at a time the country

needed decisive action” – Conservative Party Manifesto 2019; and “A Labour government will repeal

the Fixed-term Parliaments Act 2011, which has stifled democracy and propped up weak

governments” – Labour Party Manifesto, 2019

20

Joint Committee on the Fixed-term Parliament Act, Report, 24 March 2021, HC 1046 2019-21

21

Cabinet Office, Draft Fixed-term Parliaments Act 2011 (Repeal) Bill, CP 322, 1 December 2020

22

Ibid, Explanatory Notes (paras 15-17) description of clause 3 of the draft bill

23

Ibid, Explanatory Notes, para 2

11 Commons Library Research Briefing, 30 June 2021Dissolution and Calling of Parliament Bill 2021-22

Alongside the draft Bill, the Government published a single-page “draft

statement of the non-legislative constitutional principles that apply to

dissolution”. A fuller description of the constitutional position before the

passage of the FTPA can be found in Chapter 6 of the Draft Cabinet Manual,

which the Cabinet Office submitted to the Justice Committee in February

2010, in connection with its inquiry into constitutional processes following a

general election. 24

On the same day, Chloe Smith, Minister of State, Cabinet Office, issued a

written statement, which outlined the provisions of the draft bill and

announced the publication of the summary of dissolution principles. 25

Review of the Act

The Committee concluded that the Act was “flawed in several respects”:

• The supermajority requirement “risks parliamentary gridlock” and given

it could be overridden by bespoke primary legislation, it lacked

credibility;

• Statutory provisions for no confidence allowed a Government to refuse to

put no confidence motions in other terms before the House;

• The loss of a vote on a matter of confidence could no longer lead directly

to a general election;

• What would happen in the 14-day period following a vote of no

confidence was unclear.

The Committee believed that any stand-alone review of the Act would have

recommended changes to remedy these flaws. 26

The Committee did hear some evidence that the FTPA was unfairly blamed for

some of the difficulties faced in the 2017 Parliament and that it had worked

well. 27

Scrutiny of the draft Bill28

The Committee reviewed the legal debate on whether it was possible to revive

a prerogative power that had been abolished. The Committee said “it is clear

that it would be impossible to simply repeal the Fixed-term Parliaments Act,

as to do so would cause legal uncertainty”. The Committee agreed with the

Government that it was possible to revive the prerogative in the way it

24

Justice Committee, Constitutional processes following a general election, 29 March 2010, HC 396

2009-10, Ev 23ff

25

HCWS615, 1 December 2020

26

Joint Committee on the Fixed-term Parliament Act, Report, 24 March 2021, HC 1046 2019-21, Summary

27

Joint Committee on the Fixed-term Parliament Act, Report, 24 March 2021, HC 1046 2019-21, paras 57-

58. See also, Robert Hazell and Nabila Roukhamieh-McKinna, “In defence of the Fixed-term

Parliaments Act”, Constitution Unit Blog, 13 September 2019

28

Drawn mostly from the Joint Committee’s summary

12 Commons Library Research Briefing, 30 June 2021Dissolution and Calling of Parliament Bill 2021-22

proposed in the draft Bill, although it described the Government’s approach

to instruct the courts to act as if the FTPA had never been passed as “novel”. 29

However, the Committee stressed that it was important to have a clear

understanding of the previous position. 30 The Committee noted that the

prerogative of dissolution is a personal prerogative of the Monarch and there

the Prime Minister could “request” a dissolution, not “advise” the Queen to

dissolve Parliament.

The Committee believed that this was a sufficient check on executive power,

as no Prime Minister having proper regard to constitutional convention and

practice would seek a dissolution in circumstances that risked drawing the

Monarch into matters of party-political controversy.

The Committee saw the function of the ouster clause as being to prevent a

court from examining the validity of the Monarch’s decision to dissolve

Parliament, the Prime Minister’s request that the Monarch does so, or the

reasons a Prime Minister had or gave for making the request. It noted that if

the House of Commons was required to vote for an early dissolution, the

courts would not intervene because to do so would be contrary to Article 9 of

the Bill of Rights 1689.

It also heard arguments that the courts would not, or would only very rarely,

intervene on a question involving the use of a personal prerogative by the

Monarch. Despite these observations, the majority of the Committee was

satisfied with the Government’s approach, although it recommended that “a

clearer and more limited approach to drafting the ouster clause might be as

effective”.

The Committee noted that the Government’s approach did not return

everything to the pre-2011 Act position. The election timetable had been

extended from 17 to 25 days in 2013 and the Committee recommended that a

cross-party working party should be established to consider how it could be

shortened.

The Joint Committee also reviewed the Government’s Dissolution Principles, a

document published alongside the draft bill to set out the Government’s view

of the “non-legislative constitutional principles that apply to dissolution”. 31

The Committee considered that the Government’s document was inadequate.

It set out its own understanding of the conventions on elections and

government formation under a prerogative system. 32 It thought that

consideration should be given to enshrining some of these conventions in

Standing Orders, particularly the timing of a debate on a motion of no

confidence tabled by the Leader of the Opposition. It also expected that its

29

Joint Committee on the Fixed-term Parliaments Act, Report, 24 March 2021, HC 1046 2019-21, paras

102-103

30

See also the notes on the Committee’s views on Government’s Dissolution Principles below

31

HM Government, Dissolution Principles, 1 December 2020

32

Joint Committee on the Fixed-term Parliaments Act, Report, 24 March 2021, HC 1046 2019-21, pp61-64

13 Commons Library Research Briefing, 30 June 2021Dissolution and Calling of Parliament Bill 2021-22

understanding would assist the Government when it updated the Cabinet

Manual. 33

The Joint Committee also argued that the FTPA had been misleadingly

named. As the draft bill proposed not only repealing but also replacing the

2011 Act, it recommended that when the Bill is introduced, it should be called

the Dissolution and Summoning of Parliament Bill.

Government response to the review

The Government’s response to the Joint Committee review was published and

the Dissolution and Calling of Parliament Bill 2021-22 was introduced on 12

May 2021. 34

Previous reviews of the FTPA

In early September 2020, both the Public Administration and Constitutional

Affairs Committee (PACAC) and the House of Lords Constitution Committee

issued reports on the Fixed-term Parliaments Act 2011:

• Public Administration and Constitutional Affairs Committee, The Fixed-

term Parliaments Act 2011, 15 September 2020, HC 167 2019-21

• Constitution Committee, A Question of Confidence? The Fixed-term

Parliaments Act 2011, 4 September 2020, HL Paper 121 2019-21.

Both of these reviews are discussed in the Library briefing on the Fixed-term

Parliaments Act 2011 (SN06111).

33

Ibid¸ paras 233-234

34

Cabinet Office, Government response to the Joint Committee on the Fixed-term Parliament Act

Report, CP 430, 12 May 2021

14 Commons Library Research Briefing, 30 June 2021Dissolution and Calling of Parliament Bill 2021-22

3 The Bill

This section describes the Bill. The issues raised by the Government’s

approach to repealing the FTPA and returning to the pre-FTPA means of

dissolving Parliament are considered in subsequent sections.

Clauses 1 and 2

Clause 1 of the Bill repeals the Fixed-term Parliaments Act 2011. The Joint

Committee on the Fixed-term Parliaments Act noted a simple repeal would

“cause legal uncertainty” because it was unclear whether the 2011 Act had

abolished the prerogative power of dissolution or simply put it into abeyance,

and “whether it is, in fact, legally possible to legislate for a return to

prerogative powers”. 35

Clause 2 works with Clause 1 to overcome this uncertainty. It states that:

The powers relating to the dissolution of Parliament and the calling

of a new Parliament that were exercisable by virtue of Her Majesty’s

prerogative immediately before the commencement of the Fixed-

term Parliaments Act 2011 are exercisable again, as if the Fixed-term

Parliaments Act 2011 had never been enacted.

This provision is unchanged from the draft bill and the Joint Committee

considered that this overcame the uncertainty over whether a prerogative

power could be restored.

Section 4 of this briefing considers questions about the position before the

2011 Act was passed and questions raised by the Government’s approach to

repealing the FTPA and reverting to the previous system for calling

Parliaments.

Clause 3

Clause 3 is an ouster clause. An ouster clause is “a provision in statute that

puts any exercise of the powers contained in the legislation beyond the

jurisdiction of the courts, regardless of whether it is lawful or unlawful”. 36

In the Explanatory Notes to the Bill, the Government state that Clause 3

codifies “The long-standing position prior to the 2011 Act … that the exercise

35

Joint Committee on the Fixed-term Parliaments Act, Report, 24 March 2021, HC 1046 2019-21, paras

103-104

36

Joint Committee on the Fixed-term Parliaments Act, Report, 24 March 2021, HC 1046 2019-21, para 146

15 Commons Library Research Briefing, 30 June 2021Dissolution and Calling of Parliament Bill 2021-22

of the prerogative powers to dissolve one Parliament and call another was

not reviewable by the courts”. 37

Section 5 of this briefing considers questions raised by the ouster clause.

Clause 4

Clause 4 provides that if Parliament is not dissolved early, it will

automatically dissolve after five years. This broadly restores the position

between 1911 and 2011, when a provision in the Parliament Act 1911 (repealed

by the Fixed-term Parliaments Act 2011) limited the length of a Parliament to

five years. The five years ran from the time it was appointed to meet. 38

Table 1 shows that every Parliament between 1911 and 2011 was dissolved by

the Sovereign before it would have automatically expired. Wartime

Parliaments, starting in 1911 and 1935 were extended before they were due to

expire.

37

Dissolution and Calling of Parliament Bill 2021-22, Explanatory Notes, para 8

38

The Parliament Act 1911 had amended the Septennial Act 1715 to reduce a seven year maximum length

of parliaments to five years. The amended provision of the Septennial Act 1715 read:

… all Parliaments that shall at any time hereafter be called, assembled, or held, shall and may

respectively have continuance for five years, and no longer, to be accounted from the day on

which by the writ of summons this present Parliament hath been, or any future Parliament shall

be, appointed to meet, unless this present or any such Parliament hereafter to be summoned

shall be sooner dissolved by his Majesty, his heirs or successors.

16 Commons Library Research Briefing, 30 June 2021Dissolution and Calling of Parliament Bill 2021-22

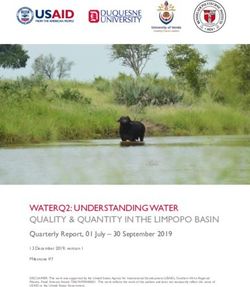

Table 1: Length of Parliaments since 1911

Parliament Summoned to meet Date of Dissolution Length (y/m)

1911 31-Jan-11 25-Nov-18 7y, 9m (3)

1919 21-Jan-19 (1) 26-Oct-22 3y, 9m

1922 20-Nov-22 16-Nov-23 0y, 11m

1924 (1923) 08-Jan-24 09-Oct-24 0y, 9m

1924 18-Nov-24 (2) 10-May-29 4y, 5m

1929 25-Jun-29 07-Oct-31 2y, 3m

1931 03-Nov-31 25-Oct-35 3y, 11m

1935 26-Nov-35 15-Jun-45 9y, 6m (3)

1945 01-Aug-45 03-Feb-50 4y, 6m

1950 01-Mar-50 05-Oct-51 1y, 7m

1951 31-Oct-51 06-May-55 3y, 6m

1955 07-Jun-55 18-Sep-59 4y, 3m

1959 20-Oct-59 25-Sep-64 4y, 11m

1964 27-Oct-64 10-Mar-66 1y, 4m

1966 18-Apr-66 29-May-70 4y, 1m

1970 29-Jun-70 08-Feb-74 3y, 7m

1974 (Feb) 06-Mar-74 20-Sep-74 0y, 6m

1974 (Oct) 22-Oct-74 07-Apr-79 4y, 5m

1979 09-May-79 13-May-83 4y, 0m

1983 15-Jun-83 18-May-87 3y, 11m

1987 17-Jun-87 16-Mar-92 4y, 8m

1992 27-Apr-92 08-Apr-97 4y, 11m

1997 07-May-97 14-May-01 4y, 0m

2001 13-Jun-01 11-Apr-05 3y, 9m

2005 11-May-05 12-Apr-10 4y, 11m

2010 18-May-10 30-Mar-15 4y, 10m

2015 18-May-15 03-May-17 1y, 11m

2017 13-Jun-17 06-Nov-19 2y, 4m

2019 17-Dec-19

(1) subsequently prorogued until 4 February 1919

(2) subsequently prorogued until 2 December 1924

(3) Wartime Parliaments, starting in 1911 and 1935, were extended beyond five years

The Joint Committee raised some issues about the length of Parliaments –

these are considered in section 7.1.

Clause 5

Clause 5 introduces the Schedule, which contains minor and consequential

amendments and some savings. The Explanatory Notes confirm that some of

the changes made by the FTPA to other Acts are retained. (More details are

given below.) So, although clause 2 returns the process of dissolving and

17 Commons Library Research Briefing, 30 June 2021Dissolution and Calling of Parliament Bill 2021-22

calling Parliaments to the position prior to the 2011 Act, some of the changes

that it made are retained.

Clause 6

Clause 6 confirms that the provisions of the Dissolution and Calling

Parliament Bill extend to the whole of the UK. The provisions also apply to the

whole of the UK: aspects of the constitution, including the UK Parliament, are

reserved matters.

Clause 6 also confirms that the Act will come into force upon Royal Assent.

The short title of the Bill has been changed since the draft Bill was published.

The Joint Committee considered that the Fixed-term Parliaments Act 2011

(Repeal) Bill did not fully encapsulate the subject matter and future function

of the Bill. It recommended the title “Dissolution and Summoning of

Parliament Act”. 39 (The Joint Committee noted that calling and summoning

“for all practical purposes mean the same thing.” 40)

The Schedule

The Schedule reverses certain changes to other electoral legislation made by

the FTPA.

The FTPA removed references to dissolution by prerogative from several

statutes, for example. Paragraphs 1, 2 and 3 restore these references to the

Succession to the Crown Act 1707, the Representation of the People Act 1867

and the Regency Act 1937.

During a general election period, registered parties need to make weekly

donation reports to the Electoral Commission. The requirement is currently

triggered by dissolution under the FTPA. Paragraph 14 removes the reference

to the FTPA. The requirement to submit weekly reports is not affected.

Paragraph 32 repeals the Early Parliamentary General Election Act 2019.

The Schedule does not restore every change made by the FTPA. Some of its

reforms to elections law would be retained or revised.

Writs for a general election are to be issued on dissolution

The Schedule confirms that the writ for a general election “is taken to have

been received … on the day after the date of the dissolution of Parliament”. 41

Before 2011, the writ was received by each returning officer on the day after

the Proclamation calling a new Parliament was issued. In practice the

39

Joint Committee on the Fixed-term Parliaments Act, Report, 24 March 2021, HC 1046 2019-21, para

101; Cabinet Office, Government response to the Joint Committee on the Fixed-term Parliament Act

Report, CP 430, 12 May 2021, p8

40

Joint Committee on the Fixed-term Parliaments Act, Report, 24 March 2021, HC 1046 2019-21, p34, n111

41

Dissolution and calling of Parliament Bill 201-22, Schedule, paras 4 and 5

18 Commons Library Research Briefing, 30 June 2021Dissolution and Calling of Parliament Bill 2021-22

Proclamation that called a new Parliament also dissolved the old Parliament.

This meant writs for the election were effectively received the day after

dissolution. The Joint Committee noted that a return to the previous

arrangement (where a single Proclamation was not a requirement) might

mean a Prime Minister could seek a dissolution of Parliament but then delay a

Proclamation calling a new Parliament. This would delay the statutory

election timetable.

The draft Bill did not include such a provision. The Committee recommended

that the Government “should legislate to ensure that a proclamation

summoning a new Parliament must be made at the same time as, or

immediately after, the dissolution of Parliament” to prevent the Executive

governing without Parliament. 42 The Bill now links the timing of a general

election to the dissolution but does not specify when a new Parliament should

be called. In its response to the Joint Committee, the Government said it did

not think that specifying when the proclamation summoning a new

Parliament must be made would be proportionate or helpful. It continued:

Any Government would not wish to delay the first meeting of

Parliament but would want to commence its legislative programme

at the earliest opportunity. 43

Flexibility in the election timetable in the case of a demise of the Crown

The Bill allows some flexibility in the extension of the election timetable in the

event of the demise of the Crown. Currently, an election is delayed by 14 days

if the Monarch dies on or after the day of dissolution but before polling day.

Under proposals in the Bill, the 14-day period can be reduced or extended by

up to seven days, by statutory proclamation. The Joint Committee agreed

that a limited degree of extra flexibility was appropriate if the Monarch died

during an election period. It recommended that the Prime Minister should be

expected to consult other party leaders before seeking to exercise this

flexibility. 44 In its response, the Government confirmed that it “would engage

interested stakeholders, including the political parties and electoral

administrators, as an appropriate and early opportunity. 45

UK parliamentary general elections – combined polls

Currently ordinary general elections to the Scottish Parliament and the Welsh

Parliament/Senedd Cymru cannot be held on the same day as an ordinary UK

parliamentary general election (ie an election held under section 1(3) of the

FTPA). But early parliamentary general elections and UK parliamentary by-

elections could be held on the same day as an ordinary general election to

the Scottish Parliament.

42

Joint Committee on the Fixed-term Parliaments Act, Report, 24 March 2021, HC 1046 2019-21, para 188

43

Cabinet Office, Government response to the Joint Committee on the Fixed-term Parliament Act

Report, CP 430, 12 May 2021, p13

44

Joint Committee on the Fixed-term Parliaments Act, Report, 24 March 2021, HC 1046 2019-21, para 192

45

Cabinet Office, Government response to the Joint Committee on the Fixed-term Parliament Act

Report, CP 430, 12 May 2021, p14

19 Commons Library Research Briefing, 30 June 2021Dissolution and Calling of Parliament Bill 2021-22

The Bill removes references to early parliamentary general elections (to the

UK Parliament) and confirms that a UK parliamentary general election and

ordinary elections to the Scottish and Welsh Parliaments cannot be held on

the same day. The Secretary of State’s powers to make regulations to

combine polls are altered accordingly. Regulations can be made to hold by-

elections or extraordinary general elections to the Scottish or Welsh

Parliament on the same day as UK parliamentary general elections. 46

Donations to third parties in the pre-dissolution period

Currently, registered third parties must submit quarterly donation reports in

the pre-dissolution period, which is defined as the 365 days before a general

election. The Bill proposes to redefine the period in which the donation

reports are required. That period would begin on the fourth anniversary of the

day in which the existing Parliament met. A donation report would have to be

submitted for each complete three months and any shorter period that ends

with dissolution.

The Bill changes the definition of a ‘reportable donation’. It removes the

struck through words shown below in the current definition (section 95A of the

Political Parties, Elections and Referendums Act 2000):

A “reportable donation” means a relevant donation (within the

meaning of Schedule 11) which—

(a) is received by the recognised third party in respect of the relevant

election or elections the poll or polls for which take place during the

qualifying regulated period, and

(b) is accepted, or is dealt with in accordance with section 56(2) (as

applied by paragraph 7 of Schedule 11), by the recognised third party

during the reporting period.

Reports must be submitted within 30 days of the end of each reporting period.

Recall of MPs – recall petitions are not triggered towards the end of a

Parliament

Under the Recall of MPs Act 2015, the Speaker is not required to give notice

that the conditions for a recall petition have been met in the six months

before an ordinary general election under the FTPA.

In the Bill, the six-month period now ends on the day on which polling would

take place if the Parliament was automatically dissolved on its fifth

anniversary (see Box 1 for an illustration of the effect of this change).

Any ongoing recall process is terminated when Parliament is dissolved.

46

Dissolution and Calling of Parliament Bill 2021-22, Schedule 1, paras 10-12 and 18-20

20 Commons Library Research Briefing, 30 June 2021Dissolution and Calling of Parliament Bill 2021-22

Box 1: Recall of MPs: Speaker not to give notice that a

recall condition has been met close to a general

election

Under the current rules:

• the Speaker does not give notice six months before dissolution;

• an election is scheduled to take place on 2 May 2024;

• Parliament would be dissolved on 26 March 2024

• a recall petition would not be triggered after 26 September 2023.

Under the new rules:

• the Speaker would not give notice six months before the last possible

date for a general election;

• the last possible date for an election is 28 January 2025;

• Parliament would be dissolved on 17 December 2025;

• a recall petition would not be triggered after 28 July 2024.

21 Commons Library Research Briefing, 30 June 2021Dissolution and Calling of Parliament Bill 2021-22

4 Issues raised by the Bill: prerogative

powers

This section and the following section discuss questions raised, particularly by

the Joint Committee that examined the draft Bill. This section considers the

Government’s approach to reviving the prerogative; alternative approaches

that could have been adopted; and the role of the Monarch and Parliament.

4.1 The prerogative is exercisable again

The Monarch is given the power to dissolve and summon Parliaments by the

Dissolution and Calling of Parliaments Bill 2021-22. Without it, it is not clear

whether the Monarch would have this power.

The Joint Committee on the Fixed-term Parliaments Act described the

background to this lack of clarity. There was “uncertainty over whether the

FtPA abolished the prerogative power of dissolution or simply put it into

abeyance”. There was also a question over whether an Act of Parliament

could restore a prerogative.

Professor Gavin Phillipson, Professor of Law at Bristol University, told the Joint

Committee that a fundamental tenet of the UK Constitution, that Parliament is

sovereign, meant that “a sovereign parliament must be able actually to

abolish–to ‘unmake’ —prerogative powers, not merely place them into

temporary suspension.”

But the Committee also heard the contrary, that the sovereignty of Parliament

requires that Parliament, in fact, be able to revive the prerogative otherwise

the House of Commons that passed the FTPA would have effectively bound its

successors. Robert Craig, Law Lecturer at Bristol University, told the

Committee that: “The fundamental and orthodox principle that a current

parliament can completely unmake a previous Act of Parliament is therefore

directly at stake.” 47

The Joint Committee considered whether the distinction between abolition

and abeyance mattered and asked whether the prerogative could be revived

regardless. It was told that prerogative powers were non-statutory Executive

powers; that prerogative powers could be abolished by statute but that they

could not be created or revived by statute. Rather, as Daniel Greenberg,

Counsel for Domestic Legislation, Office of the Speaker’s Counsel, told the

47

Joint Committee on the Fixed-term Parliaments Act, Report, 24 March 2021, HC 1046 2019-21, para 105

22 Commons Library Research Briefing, 30 June 2021Dissolution and Calling of Parliament Bill 2021-22

Committee: “the restored prerogative powers of dissolution of Parliament will

now owe their continued life to a statute”. 48

The Committee considered that the Government, in its draft bill, had

overcome this potential uncertainty. 49 The Dissolution and Calling of

Parliament Bill 2021-22 both repeals the FTPA and replaces it. On the draft bill

the Committee commented that:

[The Government’s] position, therefore, is that it does not, for

practical purposes, matter whether the prerogative is capable of

revival as any legal uncertainty is resolved because the legislation is

clear that revival of the pre-2011 constitutional arrangements is the

statutory intention. 50

A difference between the Government’s Explanatory Notes for clause 2 in the

draft and actual bills indicate this:

Draft Bill Subsection (1) makes express provision to revive the

prerogative powers relating to the dissolution of Parliament,

and the calling of a new Parliament. This means that, as was

the case prior to the FTPA, Parliament will be dissolved by the

Sovereign, exercising prerogative power on the advice of the

Prime Minister. 51

Actual Bill Subsection (1) makes express provision to make the

prerogative powers relating to the dissolution of Parliament,

and the calling of a new Parliament exercisable again, as if the

2011 Act had never been enacted. This means that, as was the

case prior to the 2011 Act, Parliament will be dissolved by the

Sovereign, exercising the revived prerogative power, on the

request of the Prime Minister. 52

In evidence on 23 June 2021 to the Public Administration and Constitutional

Affairs Committee, on the Dissolution and Calling of Parliament Bill, Cabinet

Office Minister Chloe Smith said:

We are expressly legislating to revive the previous arrangements,

which, as you note, are based on a prerogative power. We know that

there has been a debate on the subject of whether such things can

be revived or restored, or whether they are abolished or put into

abeyance. Your Committee has heard evidence on that, as did the

Joint Committee that looked at the Bill. We think the correct answer

is to be expressly clear, and that is what we have been in the Bill. We

48

Joint Committee on the Fixed-term Parliaments Act, Report, 24 March 2021, HC 1046 2019-21, para

109

49

Joint Committee on the Fixed-term Parliaments Act, Report, 24 March 2021, HC 1046 2019-21, para 111

50

Joint Committee on the Fixed-term Parliaments Act, Report, 24 March 2021, HC 1046 2019-21, para 111

51

Cabinet Office, Draft Fixed-term Parliaments Act 2011 (Repeal) Bill, CP 322, December 2020, ENs, para

13

52

Dissolution and Calling of Parliament Bill 2021-22, Explanatory Notes, para 18

23 Commons Library Research Briefing, 30 June 2021Dissolution and Calling of Parliament Bill 2021-22

think that is backed up by clear voices in the debate, and in the

academic and legal commentary, which suggests that that is the

right course of action to achieve certainty and give people clarity

about what has been revived and what has been repealed. 53

4.2 What is the power?

The Joint Committee understood the powers under the prerogative of

dissolution and calling of Parliaments to be “legally uncomplicated” prior to

the FTPA. As a matter of law, it said:

a) The Monarch could dissolve Parliament by proclamation at any

time before the expiry of its maximum term;

b) The Monarch had discretion as to when to summon a new

Parliament by proclamation, provided that they did so within three

years of the dissolution of the last Parliament; and

c) Election writs could be and were prepared and issued immediately

following a proclamation summoning the new Parliament. 54

These powers are not expressly stated in the Bill. Despite this, the Joint

Committee concluded that “their legal nature and scope are widely accepted

and straightforward to explain”. 55

However, the Committee readily acknowledged that the legal nature of those

powers was only one important part of the constitutional picture. The

dissolution and calling of Parliament was influenced (pre 2011) far more by

non-legal constitutional conventions and shared political understandings

about how personal prerogative powers should be exercised, than by the

theoretical outer legal limits of those powers. The extent to which, for

example, the Monarch had a veto over dissolution requests that could ever be

exercised, for example, was really a question about constitutional

conventions, not one about the law.

On the conventions underpinning the operation of the powers, the Joint

Committee concluded that:

… As long as there is clarity about what these rules are, and how the

exercise of the prerogative is governed by constitutional conventions

to do with dissolution, calling of Parliaments, confidence, and

53

Public Administration and Constitutional Affairs Committee, Oral Evidence Dissolution and Calling of

Parliament Bill, 23 June 2021, Q6

54

Joint Committee on the Fixed-term Parliaments Act, Report, 24 March 2021, HC 1046 2019-21, para 117

55

Joint Committee on the Fixed-term Parliaments Act, Report, 24 March 2021, HC 1046 2019-21, para 118

24 Commons Library Research Briefing, 30 June 2021Dissolution and Calling of Parliament Bill 2021-22

government formation, this statutory approach is likely to be

effective. 56

The Joint Committee appeared to be much more sceptical about whether the

Government would be reviving the wider conventional framework on which

the old prerogative system used to depend. It described the Government’s

account of the conventions (the so-called ‘Dissolution Principles’) as

“inadequate”, offered its own account of what those conventions were and

ought to be, and called for the Government to address them more clearly in a

future iteration of the Cabinet Manual (see section 6).

The Joint Committee reported comments from witnesses who told it that one

of the reasons for the uncertainty about the operation of the prerogative

system of dissolution “is that most of the actions and representations made

by the monarch take place in private”. 57

4.3 Conventions, political controversy and the

Monarch

In the foreword to the draft Bill and in the Dissolution Principles, 58 published

alongside the draft Bill, the Government said that “Parliament will be

dissolved by the Sovereign, on the advice of the Prime Minister” [emphasis

added]. 59 However, the Joint Committee argued that by reverting to the

prerogative system the Government proposed to “restore, at least formally,

legal powers to the Monarch”.

The Committee recommended that the Government should replace any

explanatory references to “advice” on dissolution to “requests” for

dissolution, since the powers to dissolve and summon a Parliament are

personal prerogatives. 60

The Government accepted this recommendation and changes have been

made to the Explanatory Notes. In its response to the Joint Committee, the

Government used “request” when referring to the Prime Minister seeking a

dissolution. In its comments on the Committee’s recommendation, it

confirmed that:

In repealing the FTPA, we are returning to a position whereby the

power to dissolve Parliament is exercised solely by the Sovereign as a

‘personal prerogative power’. We are grateful to the Committee for

56

Ibid

57

Joint Committee on the Fixed-term Parliaments Act, Report, 24 March 2021, HC 1046 2019-21, paras

127-128

58

HM Government, Dissolution Principles, undated

59

Cabinet Office, Draft Fixed-term Parliaments Act 2011 (Repeal) Bill, CP 322, December 2020, Foreword

60

Joint Committee on the Fixed-term Parliaments Act, Report, 24 March 2021, HC 1046 2019-21, para 124

and para 142

25 Commons Library Research Briefing, 30 June 2021Dissolution and Calling of Parliament Bill 2021-22

its scrutiny of how this is described in the dissolution principles

paper, and agree that the better description is that the Prime

Minister “requests” a dissolution. 61

This means that the Monarch does have discretion when the Prime Minister

requests a dissolution. The Joint Committee considered the circumstances in

which a Monarch might refuse a dissolution. It recommended that:

If the Monarch’s role in dissolution is indeed to be other than purely

ceremonial, there should be clarity about at least some of the

circumstances where exercising a veto would, or at least could, be

constitutionally appropriate. […]

The Government should consider further how best to articulate the

role of the Monarch in this process, to build trust in the prerogative

system they wish to implement. At the least, any revision of the

Cabinet Manual should, unlike the initial Dissolution Principles

document, address much more directly how the Monarch’s veto

operates in practice. 62

In its response to the Joint Committee, the Government said that there would

be circumstances in which the Monarch would refuse a dissolution request. It

did not identify any such circumstances. Nor has the Government said when it

considered it would be inappropriate for the Government to request a

dissolution:

In returning to the position where the Prime Minister is able to

request a dissolution, there remains a role for the Sovereign to in

certain circumstances refuse a dissolution request. It is not possible

to predict every scenario and challenge that a country might face.

That is why a constitution that provides flexibility in exceptional

circumstances is necessary for a functioning and modern

democracy. 63.

Nor has the Government said when it considered it would be inappropriate for

the Government to request a dissolution.

The Government also said that it would be “incumbent” on those involved in

the political process to ensure that the Monarch was not drawn into party

politics. It also accepted that “once the FTPA has been repealed the

Government will need to revisit these sections of the Cabinet Manual.” 64

61

Cabinet Office, Government response to the Joint Committee on the Fixed-term Parliament Act

Report, CP 430, 12 May 2021, p10

62

Joint Committee on the Fixed-term Parliaments Act, Report, 24 March 2021, HC 1046 2019-21, paras

144-145

63

Cabinet Office, Government response to the Joint Committee on the Fixed-term Parliament Act

Report, CP 430, 12 May 2021, p10

64

Cabinet Office, Government response to the Joint Committee on the Fixed-term Parliament Act

Report, CP 430, 12 May 2021, p10

26 Commons Library Research Briefing, 30 June 2021Dissolution and Calling of Parliament Bill 2021-22

When might a dissolution be refused?

Under the pre FTPA system some information in the public domain gave what

the Joint Committee described as “some indication of the circumstances in

which the Monarch might refuse a request to dissolve Parliament”. It drew

attention, for example, to the so-called ‘Lascelles Principles’:

Sir Alan Lascelles, the then King’s private secretary, posited

pseudonymously in The Times that a wise Sovereign would only

refuse a dissolution request if he or she were satisfied that:

a) The existing Parliament was “vital, viable and capable of doing its

job”;

b) A general election would be “detrimental to the national

economy”; and

c) He or she could “rely on finding another prime minister who could

govern for a reasonable period with a working majority in the House

of Commons.” 65

The Joint Committee considered that these principles were “a reliable guide

to the nature of the Monarch’s veto over dissolution from 1950 to at least the

1990s.” But since then, according to Lord Hennessy, Attlee Professor of

Contemporary British History, the Committee reported that “it was sufficient

to say that a Monarch could refuse a dissolution if the Parliament remained

vital, viable and capable and that an alternative government could carry on

for a reasonable period of time with a working majority in the Commons.” 66

Other witnesses identified circumstances in which a dissolution might be

refused in Commonwealth countries, suggesting that they might also apply to

the UK. A Prime Minister who was defeated at an election would not have the

right to request a further dissolution; neither would a Prime Minister who was

defeated on an amendment to the Queen’s Speech immediately after a

general election.

A dissolution request might also be refused if the Government would run out

of supply between dissolution and the State Opening of the new Parliament.

As in the UK, if holding an election was “damaging” or a shift in majority could

lead to “a baton change” without an election, then the Monarch might refuse

an election. 67

The Joint Committee on the FTPA suggested examples of its own:

• “a Prime Minister should not make a dissolution request if it is made

simply to avoid forthcoming changes in electoral boundaries”; and

65

Joint Committee on the Fixed-term Parliaments Act, Report, 24 March 2021, HC 1046 2019-21, para 129

66

Joint Committee on the Fixed-term Parliaments Act, Report, 24 March 2021, HC 1046 2019-21, para 130

67

Joint Committee on the Fixed-term Parliaments Act, Report, 24 March 2021, HC 1046 2019-21, paras

130-135

27 Commons Library Research Briefing, 30 June 2021You can also read