Contrastive Multiple Correspondence Analysis (cMCA): Using Contrastive Learning to Identify Latent Subgroups in Political Parties - arXiv

←

→

Page content transcription

If your browser does not render page correctly, please read the page content below

Contrastive Multiple Correspondence Analysis

(cMCA): Using Contrastive Learning to Identify

Latent Subgroups in Political Parties

Takanori Fujiwara* 1 and Tzu-Ping Liu2

1 Department of Computer Science, University of California at Davis, Davis, CA 95616, USA. Email:

tpliu@ucdavis.edu

1 Department of Political Science, University of California at Davis, Davis, CA 95616, USA. Email:

tpliu@ucdavis.edu

arXiv:2007.04540v2 [cs.SI] 15 Jan 2021

Abstract

Scaling methods have long been utilized to simplify and cluster high-dimensional data. However, the latent

spaces derived from these methods are sometimes uninformative or unable to identify significant differences

in the data. To tackle this common issue, we adopt an emerging analysis approach called contrastive learn-

ing. We contribute to this emerging field by extending its ideas to multiple correspondence analysis (MCA) in

order to enable an analysis of data often encountered by social scientists—namely binary, ordinal, and nom-

inal variables. We demonstrate the utility of contrastive MCA (cMCA) by analyzing three different surveys of

voters in Europe, Japan, and the United States. Our results suggest that, first, cMCA can identify substantively

important dimensions and divisions among (sub)groups that are overlooked by traditional methods; second,

for certain cases, cMCA can still derive latent traits that generalize across and apply to multiple groups in the

dataset; finally, when data is high-dimensional and unstructured, cMCA provides objective heuristics, above

and beyond the standard results, enabling more complex subgroup analysis.

1 Introduction

Scaling has been a prolific and popular topic for research throughout political science. Scholars

have developed and utilized a diverse set of methods to identify political actors’ “positions” on the

left-right ideological space. This has been accomplished by utilizing one of two general ideas: “op-

timal scoring”(Jacoby 1999) and “spatial voting”(Enelow and Hinich 1984). While optimal scoring

methods include principal component analysis (PCA), multiple correspondence analysis (MCA),

and factor analysis(e.g., Brady 1990; Davis, Dowley, and Silver 1999), spatial voting methods en-

compass Aldrich-McKelvey scaling, the NOMINATE class of models, two-variable item response

theory, and optimal classification(e.g., Aldrich and McKelvey 1977; Clinton, Jackman, and Rivers

2004; Hix, Noury, and Roland 2006; Martin and Quinn 2002; Poole 2000; Poole and Rosenthal 1991).

These methods have most often been applied to roll-call votes in the United States Congress, or

other political bodies; however, they have been increasingly used to analyze a range of new data,

including surveys and text (Hare, Liu, and Lupton 2018; Imai, Lo, and Olmsted 2016; Monroe, Co-

laresi, and Quinn 2008; Poole 1998; Wilkerson and Casas 2017).

In general, these methods uncover the similarities/differences between observations in a given

dataset. These similarities are then used to estimate a small number of (underlying) dimensions

that reflect the similarities as a set of spatial distances between all of the estimated points. These

lower-dimensional representations can both help us to understand the general structure of a given

dataset, such as its distribution, and identify underlying patterns, like clusters and outliers (Fuji-

wara, Kwon, and Ma 2020; Wenskovitch et al. 2018). More precisely, these methods are often ex-

* Equal contribution and listed alphabetically.

1plicitly used to (1) identify clusters; (2) derive influential factors (dimensions); and (3) compare

the derived clusters and/or factors with predefined classes or groups (e.g., Armstrong et al. 2014;

Brady 1990; Davis, Dowley, and Silver 1999; Grimmer and King 2011; Hare et al. 2015; McCarty,

Poole, and Rosenthal 2001; Rosenthal and Voeten 2004).

In addition to deriving lower-dimensional spaces, correctly interpreting these recovered di-

mensions is just as, if not more, important. Since the work of Coombs (1964), the latent left-right

dimension of ideology is often recovered as a principal component/direction (PC) in political data.

Indeed, almost all of the methods discussed previously recover ideology as their first PC. Never-

theless, these methods can face situations when the left-right scale is uninformative, e.g., when

respondents are highly moderate or the data contains large amounts of missing values. Because of

this clustering, it is difficult to delineate between voters of some given group or category, such as

those that belong to an established political party. While this does not happen particularly often,

cases of strong moderation are found throughout political science (such as in Japan’s electorate,

see below).

Although derived scaling results may not be very interesting or informative, it does not neces-

sarily mean that supporters from different parties are politically similar. Rather, supporters from

different parties may be divided by specific issues or directions that are not captured by the left-

right scale. Thus, to analyze potential differences above and beyond simple ideological divides

Abid et al. (2018) derive a contrastive learning variant of PCA, named contrastive PCA (cPCA). This

method, instead of analyzing the data as a whole, first splits data into different groups, usually

by predefined classes (e.g., party ID), and then compares the data structure of the target group

against the background group to find PC(s) on which the target group varies maximally and the

background group varies minimally. This method can uncover within-group differences, as shown

below, such as euroskepticism among British voters within both major parties, and xenophobia

within the major conservative party in Japan.

We contribute to the field of contrastive learning by extending this idea from PCA to MCA so as

to enable the derivation of contrastive PC(s) using different types of features/data that social sci-

entists encounter frequently: binary, ordinal, and nominal data. With contrastive MCA (cMCA), we

find that even when voters are highly moderate and homogeneous across party lines, we can still

explore how specific issue(s) effectively identify subgroups within the parties themselves. Similar

to cPCA, cMCA first splits the data by predefined groups, such as partisanship or treatment and

control groups; second, as is the case with MCA, cMCA applies a one-hot encoder to convert a cat-

egorical dataset into a binary format matrix, called a disjunctive matrix; finally, cMCA takes one of

the groups as the background/pivot and then compares this group with the target group to derive

PCs on which the positions of members’ ideal points from target groups vary the most but those

from the background group vary the least.

To demonstrate the utility of cMCA, we analyze two surveys, the 2018 European Social Survey

(ESS 2018, the U.K. module only) and the 2012 Asahi-Todai Elite Survey (UTAS 2012). The results

show that when voters are highly moderate and the derived latent spaces are uninformative, as

shown by the results from the ESS 2018 and UTAS 2012, cMCA objectively detects subgroups along

with certain directions which are overlooked by traditional approaches, such as pro- and anti-EU

attitudes among supporters from each of the U.K.’s Conservative and Labour parties; or the anti-

Korean and Chinese sentiments among supporters of the Liberal Democratic Party in Japan.

This work makes an important contribution to scaling methods and unsupervised learning by

enabling researchers to identify latent dimensions that effectively classify and divide observations

(voters) even when the left-right scale cannot effectively discriminate between classes/groups (par-

tisanship). This method, as evidenced by its application to voter surveys, objectively and meaning-

fully identifies latent dimensions that would be, and are, overlooked by existing methods. Simply

put, cMCA’s results provide important information for researchers to better understand and make

Fujiwara and Liu 2meaningful distinctions between underlying groups in their data.

Moreover, compared with existing scaling methods such as the (Bayesian) Aldrich-McKelvey

Scaling method (Aldrich and McKelvey 1977; Hare et al. 2015), the ordered optimal classification

(Hare, Liu, and Lupton 2018), the basic-space procedure (Poole 1998), and the Bayesian mixed

factor analysis model (Martin, Quinn, and Park 2011; Quinn 2004), all of which tend to remedy the

missing data issue through imputation or deletion; cMCA, on the contrary, allows researchers to

analyze regular and missing data simultaneously by treating missing data as one of the levels—this

is important given that sometimes the presence of missing data may be theoretically meaningful

and interesting (Greenacre and Pardo 2006).

Finally, to date, almost all of the methods for subgroup analysis, such as class specific MCA

(CSA) (Hjellbrekke and Korsnes 1993; Le Roux and Rouanet 2010) and subgroup MCA (sMCA) (Greenacre

and Pardo 2006) (see Section 4 for detailed discussion), requires researchers to already know how

data should be “subgrouped” in the latent dimensions, and therefore, without such prior knowl-

edge, these methods are almost infeasible, especially when data is high-dimensional and unstruc-

tured. By objectively revealing the overlooked influential factors, cMCA indeed provides a spring-

board for further subgroup analyses when information about how to determine those subgroups

is unavailable. Overall, we believe that cMCA provides an important contribution to data visual-

ization, subgroup analysis, and unsupervised learning. The paper proceeds with a description of

cMCA, its application to our two voter surveys, and then concludes with general thoughts about,

and rules of thumb for using, cMCA, i.e., its comparison with current subgroup analysis methods,

and its application to substantive topics.

2 Contrastive Learning and Contrastive MCA

Contrastive learning (CL) is an emerging machine learning approach which analyzes high-dimensional

data to capture “patterns that are specific to, or enriched in, one dataset relative to another” (Abid

et al. 2018). Unlike ordinary scaling approaches, such as PCA and MCA, that usually aim to capture

the characteristics of one entire dataset, CL compares subsets of that dataset relative to one an-

other (target versus background group). The logic behind CL is to explore unique components or

directions that contain more salient latent patterns in one dataset (the target group) than the other

(background group). So far, this approach has been applied to several machine learning meth-

ods, including PCA (Abid et al. 2018), latent Dirichlet allocation (Zou et al. 2013), hidden Markov

models (Zou et al. 2013), regressions (Ge and Zou 2016), and variational autoencoders (Sever-

son, Ghosh, and Ng 2019). We utilize this contrastive learning approach by applying it to MCA,

an enhanced version of PCA for nominal and ordinal data analysis (Greenacre 2017; Le Roux and

Rouanet 2010).

2.1 Multiple Correspondence Analysis (MCA)

When applying PCA to non-continuous data, the method considers each level or category in the

data as a real numerical value. As a result, PCA necessarily ranks the categories and assumes that

the intervals are all equal and represent the differences between categories (i.e., it treats it as inter-

val data). To overcome these issues, MCA first converts an input dataset X ∈ Òp×d (p: the number

of data points, d : the number of variables) of non-continuous data into what is called a disjunc-

tive matrix G ∈ Òp×K (K : the total number of categories) by applying one-hot encoding to each

of d categorical dimensions (Harris and Harris 2010). For illustration, assume that X consists of

two columns/variables: color and shape, and each variable has three (red, green, blue) and

two (circle, rectangle) levels, respectively. In this case, the disjunctive matrix G will contain

five categories: red, green, blue, circle, and rectangle. For instance, a piece of blue rectangle

paper will be recorded as [0, 0, 1, 0, 1] in G.

Fujiwara and Liu 3We could further derive a probability/correspondence matrix Z through dividing each value of

G by the grand total of G (i.e., Z = N −1 G where N is the grand total of G). This probability matrix

can now be treated as a typical dataset for use in analyses. Similar to PCA, we first normalize Z and

def

then obtain what is called a Burt matrix, B, with B = Z⊤ Z (B ∈ ÒK ×K ). This Burt matrix B under

MCA corresponds to a covariance matrix under PCA. Thus, as in PCA, to derive principal directions,

MCA performs eigenvalue decomposition (EVD) to B to preserve the variance of G.1

2.2 Extending MCA to cMCA

To apply CL to MCA, we first split the original dataset X ∈ Òp×d into a target dataset XT ∈ Òn×d and

a background dataset XB ∈ Òm×d (where p = n + m) by a certain predefined boundary, such as

individuals’ partisanship or whether they were assigned to treatment or control groups. We then

further derive two Burt matrices from the target and background datasets, BT and BB , respectively.

Importantly, because the CL procedure utilizes matrix differences, the Burt matrices must have the

same dimensions, i.e., BT ∈ ÒK ×K and BB ∈ ÒK ×K .

Let u be any unit vector with K dimensions. Similar to cPCA (Abid et al. 2018), we can derive

def

the variances of the target and background datasets along with u by using σT2 (u) = u⊤ BT u and

def

σB2 (u) = u⊤ BB u. To find the direction u∗ on which a target dataset’s probability matrix, ZT , has

large variances and a background dataset’s probability matrix, ZB , has small variances, one needs

to solve the optimization problem:

u∗ = arg max σT2 (u) − α σB2 (u) = arg max u⊤ (BT − α BB )u (1)

u u

where α is a hyperparameter of cMCA, called the contrast parameter. From Equation 1, we can

see that u∗ corresponds to the first eigenvector of the matrix (BT − α BB ). Note that all of the

eigenvectors of (BT − α BB ) can be derived through performing EVD over (BT − α BB ).2 We call

these derived eigenvectors contrastive principal components (cPCs).

2.3 Selection of the Contrast Parameter

The contrast parameter α in Equation 1 controls the trade-off between having high target variance

versus low background variance. When α = 0, the resulting cPCs only maximize the variance of a

target dataset producing results that are equivalent to applying standard MCA to only the target

dataset. As α increases, cPCs place greater emphasis on directions that reduce the variance of

a background dataset. As proved by Abid and Zou (2019), by selecting arbitrary α values within

0 ≤ α ≤ ∞, CL methods allows the researchers to produce different latent spaces with each

latent space showing a different ratio of high target variance to low background variance—rather

than representing a best solution to Equation 1, the contrastive parameter, α , instead represents

a “value set.” Thus, researchers can manually apply different α values as long as the derived latent

spaces demonstrate “interesting” or meaningful patterns.

In addition to manual selection, we extend the method of Fujiwara, Zhao, Chen, Yu, et al. (2020)

to develop a technique for automatically selecting a special value of α , from which researchers can

derive the latent space where a target dataset has the highest variance relative to a background

dataset’s variance. This specific α can be found by solving the following ratio problem:

tr(U⊤ BT U)

max (2)

⊤

U U=I tr(U⊤ BB U)

1. Similar to PCA, without computing B, one could directly apply singular value decomposition (SVD) to Z to obtain the

same principal directions.

2. Unlike MCA, SVD cannot be applied to compute cPCs for cMCA due to the difference between target and background

datasets’ Burt matrices (i.e., BT − αBB ) may generate negative numbers.

Fujiwara and Liu 4′ ′

where U ∈ ÒK ×K is the top-K eigenvectors obtained by EVD. Following Dinkelbach (1967), we

employ an iterative algorithm to solve Equation 2 which is usually difficult to solve. This algorithm

consists of two steps: given eigenvectors Ut at iteration step t (t ≥ 0 and t ∈ Ú), we perform

tr(U⊤

t BT Ut )

Step1. αt ← (3)

tr(U⊤

t BB Ut )

tr U⊤ (BT − αt BB )U

Step2. Ut +1 ← arg max

⊤

(4)

U U=I

At t = 0, because the computed U0 does not exist, we self-define α0 = 0 as the default solution to

Step 1. As demonstrated, αt in Equation 3 is an objective value of Equation 2, which is computed

with the current Ut . The second step (Equation 4) is to derive the eigenvectors, Ut +1 , for the next

iteration. This step just solves the original cMCA problem based on the current contrastive parame-

ter, αt . With this iterative algorithm, αt monotonically increases to the maximum value and usually

converges quickly (i.e., in less than 10 iterations).

Note that when BB is nearly singular, αt approaches infinity. One potential solution to avoid

this issue is adding a small constant value, ε (e.g., ε = 10−3 ), to each diagonal element of BB . How-

ever, given that ε does not have a clear connection to the optimization problem in Equation 2, and

consequently, it is hard for researchers to control α ’s search space. Therefore, we add ε tr(UT BT U)

tr(U⊤

t BT Ut )

to the denominator of Equation 3, i.e., αt ← tr(U⊤ BB Ut )+ε tr(U⊤ BT Ut )

. Through this way, we now can

t t

control the search space so that αt reaches at most 1/ε (e.g., when ε = 10−3 , αt may increase up

to 1,000).

2.4 Data-Point Coordinates, Category Coordinates, and Category Loadings

As in ordinary MCA, in cMCA, we provide three essential tools for helping researchers relate data

points and categories/variables to the contrastive PC space: (1) data-point coordinates (also known

as coordinates of rows (Greenacre 2017), or clouds of individuals (Le Roux and Rouanet 2010)), (2)

category coordinates (also known as coordinates of columns (Greenacre 2017), or clouds of cat-

egories (Le Roux and Rouanet 2010)), and (3) category loadings. These three tools each provide

unique and useful auxiliary information for understanding the structure of the data.

Data-point coordinates provide a lower-dimensional representation of the data, which is stan-

dard in most dimensional reduction techniques. Furthermore, category coordinates and loadings

provide essential information on how to interpret these data-point coordinates. Similar to data-

point coordinates, category coordinates present the position of each category/level in a lower-

dimensional space. Given that the coordinates of each category are on the same contrastive la-

tent space with data-point coordinates (see Equation 7), by comparing these two sets of coordi-

nates, we can better understand the associations and relationships between the data points and

categories. Through comparing the positions of data-point and category coordinates, a given cate-

gory’s position implies that respondents who are close to that position are highly likely to withhold

that specific attribute (Greenacre 2017; Le Roux and Rouanet 2010; Pagès 2014). On the other hand,

category loadings indicate how strongly each category relates to each derived contrastive PC.3

′ ′

Similar to MCA, for a target dataset XT , cMCA’s data-point coordinates YTrow ∈ Òn×K (K < K )

can be derived as:

YTrow = ZT U (5)

′ ′

where U ∈ ÒK ×K is the top-K eigenvectors obtained by EVD. Similarly, we can obtain data-point

3. We provide a detailed discussion of the category selection procedure in Section 3.

Fujiwara and Liu 5coordinates, YBrow , of a background dataset XB onto the same low-dimensional space of YTrow through:

YBrow = ZB U (6)

As discussed in Fujiwara, Zhao, Chen, and Ma (2020), visualizing low-dimensional representations

of both target and background datasets can help researchers determine whether or not a target

dataset has certain specific patterns relative to a background dataset. When the scatteredness/shape

of plotted data points of YTrow is larger than YBrow , we can conclude that there exists a set of unique

patterns within YTrow .

In MCA, the most common way of deriving a dataset X’s category coordinates, Ycol , is through

Ycol = DW, where D is a diagonal matrix with the sum of each column of Z on the diagonal and W

′

is a matrix whose column vectors are the top-K eigenvectors obtained with EVD on B. However,

because cMCA applies EVD to the matrix, (BT −α BB ), the result is necessarily affected by XB as well.

As a consequence, we cannot simply compute category coordinates using the methods described

above. To overcome this issue, instead, we utilize MCA’s translation formula derived from data-

point coordinates to calculate category coordinates (Greenacre 2017). More precisely, the category

′

coordinates of the target dataset, YTcol ∈ ÒK ×K , can be derived through:

YTcol = DT−1 ZT⊤ YTrow diag(λ) −1/2 (7)

where DT ∈ ÒK ×K is a diagonal matrix with the sum of each column of ZT on the diagonal and

′ ′

λ ∈ ÒK is a vector of the top-K eigenvalues derived from Equation 1.

Finally, since MCA’s derivation procedure is highly similar to that of PCA, we utilize the concept

of principal component loadings in PCA to calculate category loadings in cMCA. More precisely,

′

category loadings, LT ∈ ÒK ×K , under cMCA can be derived through:

LT = U diag(λ) 1/2 (8)

3 Application

To demonstrate a), the utility of cMCA with high-dimensional and unstructured data, and b), the

derived results based on the manual- or auto-selection techniques, we analyze two surveys— the

ESS 2018 (the U.K. module) and the UTAS 2012. As suggested by Le Roux and Rouanet (2010), we

first recode some variables, before applying cMCA, to deal with the potential issue of infrequent

categories of active variables, such as the most extreme categories or missing values, that these

infrequent categories could be overly influential for the determination of latent axes. In general,

we keep all missing values and code them as 99; furthermore, when the number of levels of an

active variable is greater than five, we pool the adjacent two or three categories as a new category.4

For instance, the left-right ideological scale in ESS 2018 is originally an eleven-point scale from

zero through ten, we transfer this variable as a new five-point scale—respondents who originally

responded as 0 or 1 are recoded as 1, those who originally responded as 2 or 3 are recoded as 2,

those who originally responded as 4, 5, or 6 are recoded as 3, those who originally responded as 7

or 8 are recoded as 4, and those who originally responded as 9 or 10 are recoded as 5. Given that the

home countries of these surveys, the U.K. and Japan, have very different political environments,

these surveys provide a wide-range of political situations for testing. Furthermore, given that the

general political systems and cultures of each country are unique, we also test the consistency of

the derived cMCA results with the observed, qualitative political realities in each country.

4. For a more detailed recoding scheme, please refer to Appendix B.

Fujiwara and Liu 6OOC Result of ESS 2018

MCA Result of ESS 2018 (All British Parties)

1.0

1

0.5

0

1

PC2

PC2

0.0

Con

2 Lab

−0.5

LD

SNP

3 Green

UKIP

−1.0 Other

4

−1.0 −0.5 0.0 0.5 1.0 2 1 0 1 2 3

PC1

PC1

(a) OOC (b) MCA

Ordinal IRT Result of ESS 2018

BlackBox Result of ESS 2018

4

1.0

2

0.5

PC2

PC2

0.0 0

−0.5 −2

−1.0 −4

−1.0 −0.5 0.0 0.5 1.0 −4 −2 0 2 4

PC1 PC1

(c) BS (d) BMFA

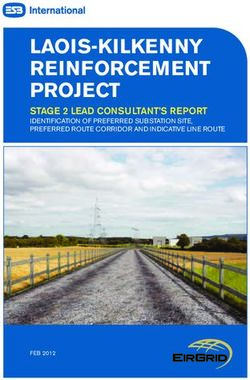

Figure 1. OOC, MCA, BS, and BMFA Results of ESS 2018

Fujiwara and Liu 7cMCA (tg: Con, bg: Lab, : 998.5) cMCA (tg: Lab, bg: Con, : 995.9)

2.5

3.0

2.0

2.5

1.5

1.0 2.0

0.5 1.5

cPC2

cPC2

0.0 1.0

0.5 0.5

1.0

0.0

1.5

Con 0.5 Lab

Lab Con

2.0

0.0 0.5 1.0 1.5 2.0 2.5 3.0 3.5 4.0 2.0 1.5 1.0 0.5 0.0 0.5 1.0 1.5 2.0

cPC1 cPC1

(a) Target: Con, Background: Lab (b) Target: Lab, Background: Con

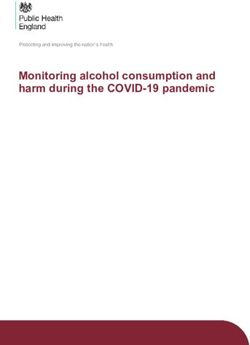

Figure 2. cMCA Results of ESS 2018 (Con versus Lab)

3.1 Case One: ESS 2018 (the U.K. Module)—the Brexit Cleavage in the Labor and Con-

servative Parties

The first survey we examine is the British module of the ESS 2018. We first manually select twenty

six questions which are generally related to political issues and recode this data through the afore-

mentioned procedure. As shown in Figure 1, we present the estimated results of all respondents

through four commonly used scaling methods for ordinal data in social science: the ordered op-

timal classification (OOC), MCA, the Basic-Space (BS) procedure, and the Bayesian mixed factor

analysis model (BMFA).5 According to Figure 1, all of the estimated results indicate that there are

no clear party lines under the ordinary PC space. This suggests that the status of political polar-

ization does not clearly exist among the mass public in the U.K. Important for the validity of these

scaling results, this conclusion is consistent with the current academic understanding that the

U.K. has undergone a period of political depolarization since the second wave of ideological con-

vergence between the elites of the two major parties, the Conservative and Labour parties (Adams,

Green, and Milazzo 2012a, 2012b; Leach 2015).

In addition, this survey was conducted from August 10th, 2018 through February 22nd, 2019,

which was between the two snap elections triggered around the issue of the UK’s departure from

the European Union (EU), commonly known as Brexit (Cutts et al. 2020; Heath and Goodwin 2017).

Theoretically, given how salient and polarized the Brexit issue is (Hobolt, Leeper, and Tilley 2018),

we should expect that such high salience should be reflected in voters’ responses and be revealed

on the derived PC space. However, as we see in Figure 1, the ESS results from traditional methods

do not demonstrate any clear evidence that voters are separated by preferences related to Brexit.

This suggests a clear failing of traditional methods in examining issue divisions in the U.K.’s elec-

torate.

In contrast to the traditional methods, we apply cMCA with the automatic selection of α to ESS

2018 and present the results in Figure 2 and Figure 3. As shown in Figure 2, the first pair we examine

includes the two major parties, the Conservatives and Labour. However, the results are relatively

uninformative. Figure 2a and Figure 2b together show that the two main parties fail to enrich each

other in a meaningful latent direction. In both figures, given that the clusters of Conservative and

5. Given that the purpose is only to demonstrate how well each derived result is able to cluster data, none of the sub-

figures through this paper calibrate the structure of the latent space to align the first PC with the left-right scale.

Fujiwara and Liu 8cMCA (tg: Con, bg: UKIP, : 999.9) cMCA (tg: Con, bg: UKIP, : 999.9)

3 Con 3 C

UKIP

cPC2 (European Union Related Attitude)

cPC2 (European Union Related Attitude)

UKIP

2 2

1 1

0 0

1 1

4 3 2 1 0 4 3 2 1 0

cPC1 cPC1

(a) Target: Con, Background: UKIP (b) Target: Con, Background: UKIP

(Con is color-coded by their opinions on EU)

c KIP, : 999.7

!" #$%& '()* +,- .KIP, : 999./0

3 3

cPC2 (European Union Related Attitude)

cPC2 (European Union Related Attitude)

2 2

1 1

0 0

1 1

2 2 1234568

L

9:;?

UKIP UKIP

3 3

5 4 3 2 1 0 5 4 3 2 1 0

cPC1 cPC1

(c) Target: Lab, Background: UKIP (d) Target: Lab, Background: UKIP

(Lab is color-coded by their opinions on EU)

Figure 3. cMCA Results of ESS 2018 (Con versus UKIP, Lab versus UKIP)

Fujiwara and Liu 9the Labour supporters almost perfectly stack onto one another (except for a few outliers), regard-

less of which one is the target or background group, we conclude that there are no hidden patterns

discernible by cMCA between these two main parties. This conclusion is consistent to Figure 1 and

academic wisdom of British politics (i.e., Adams, Green, and Milazzo 2012a, 2012b; Leach 2015)

Nevertheless, the sub-figures of Figure 3 tell a very different story. Instead of comparing the

two main parties themselves, we separate the parties and compare them as target groups with the

UK Independence Party (UKIP) selected as the background group. Through Figure 3a, we observe

that when UKIP supporters (the yellow points in Figure 3a) are the anchor, it splits Conservatives

(the blue points in Figure 3a) into two adjacent sub-groups along with the second contrastive PC

(cPC2) when α is automatically set to around 1000.

When using cMCA we derive two types of auxiliary information—the category coordinates and

the total category loadings—on each latent direction as heuristics for determining which categories

and variables are the most influential.6 To calculate total category loadings, we first calculate

each category’s loading through Equation 8 and further sum each category’s normalized absolute

loading (over the whole dataset) for any given variable to derive that variable’s overall loading

along with each latent direction. This means that differences in responses to the highest loading

variable(s) lead to the largest division or distance between respondents’ positions along the esti-

mated latent component. The nine variables with the highest absolute loadings (i.e., the top nine

most influential variables) and their categories in each latent direction are colored in Figure 6a and

Figure 6b—the order of the colors in the legend refers to the ranking of each variable’s loading.

The second auxiliary information we rely on is category coordinates. Through Equation 7, we

derive each variable’s coordinates and present them with the same top nine most influential vari-

ables by each latent direction in Figure 6c and Figure 6d separately. As discussed in Section 2, we

use this information to explore potential categories or attributes that respondents from different

subgroups may hold.

Although Figure 6a illustrates that the distribution of the Conservatives along the first cPC

is largely impacted by the missing values of the variables tradition (imptrad), environmental

protection (impenv), strong government (ipstrgv)), understanding (ipudrst), and equality

(ipeqopt) (in order by total category loadings), the first cPC is rather uninformative. Together with

Figure 3a and Figure 6, we see that only a handful of Conservatives are separated from the main

group by voters from UKIP along cPC1.7 Nevertheless, Figure 3a also demonstrates that Conser-

vatives can be divided by the anchor, UKIP voters, along with the second cPC, i.e., the second cPC

represents a certain trait, revealed by UKIP voters, that divides the Conservatives into two sub-

groups.

Furthermore, Figure 6b reports that the top nine most influential variables in order of dividing

Conservative voters are: religiosity (rlgdgr), immigration to living quality (imwbcnt), environ-

mental protection (impenv), tradition (imptrad), strong government (ipstrgv), emotionally

attached to Europe (atcherp), immigration to culture (imueclt), understanding (ipudrst),

and equality (ipeqopt). Interestingly, according to Figure 6b, the response of 5 to the immigra-

tion to living quality question (immigration makes the U.K. an extremely better place to live) is the

most influential category which “pulls” some Conservatives away from their co-partisans along

cPC2. The second most influential category is also the response of 5 to the immigration to cul-

ture question (the respondent’s life is extremely enriched by immigrants), which also significantly

divides Conservative voters, specifically pulling these respondents in the positive direction along

cPC2. Other influential categories which divide Conservatives along cPC2 include the response

of 1 to religiosity (extremely nonreligious), the response of 1 to the environmental protection

6. Please refer to Appendix A for figures of this auxiliary information.

7. For the combinations of new variable names and original abbreviations in the data, please refer to online Appendix B.

Fujiwara and Liu 10question (it is extremely important to care for nature and environment), and so on. In contrast, one

can also find several categories that significantly push some Conservative toward the negative end

of cPC2, such as the response of 2 to immigration’s effect on living quality, the response of 2 to

religiosity, and the responses of 2 and 3 to the environmental protection question.

The results of Figure 6b more or less reveal that Conservative voters can be divided into two

subgroups—the extremely liberal and the rest. We further utilize the coordinates of categories in

Figure 6d as another heuristic. After comparing respondents’ positions in Figure 3a, one can see

that among the top nine most influential variables, the Conservatives located on the positive side

of cPC2 are likely to hace responded with 5 to the immigration to living quality, immigration to

culture, and emotionally attached to Europe (extremely emotionally attached to Europe) ques-

tions.

More interestingly, although not all of these are top three or five loading variables for cPC2 in

Figure 3a, we find that Conservative supporters who are on the top of cPC2 in Figure 3a are as-

sociated with extremely open views over at least one of the three EU- or Brexit-related variables:

immigration to living quality, immigration to culture, and emotionally attached

to Europe.8 As shown in Figure 3b, we further color this extremely EU-supportive sub-group

(Con_Pro) in teal and color the rest of the Conservative supporters (Con_Oth) in pink.

Analogously, we also find subgroups within Labour party voters by using UKIP supporters as

the background group. Similar to the previous results, we find that when α is automatically set to

around 1000, Labour supporters’ (the orange points in Figure 3c) are split by UKIP supporters (the

yellow points in Figure 3c) along cPC2. In fact, from Figure 3c we see that only a handful of Labour

voters are separated from the main group, and thus we do not consider the first cPC to represent

any meaningful traits or issue dimensions. Nevertheless, the results in Figure 7b and Figure 7d

indicate that Labour voters have a similar distribution as the Conservatives. The top nine most

influential variables which divide respondents along the cPC2, in order, are: immigration to living

quality (imwbcnt), emotionally attached to Europe (atcherp), religiosity (rlgdgr), tradition

(imptrad), environmental protection (impenv), understanding (ipudrst), strong government

(ipstrgv), equality (ipeqopt), and immigration to culture (imueclt).

According to Figure 7b and Figure 7d, we see that Labour party voters located on the positive

side of cPC2 are highly associated with the response of 5 to the immigration to living quality,

emotionally attached to Europe, and the immigration to culture questions. Similar to the di-

mension obtained for Conservative voters, we speculate that cPC2 represents the same latent trait

which also divides Labour voters into two subgroups—those who are extremely liberal on EU re-

lated issues and the rest. We further divide Labour supporters into two sub-groups with different

colors and present them in Figure 3d: those who hold extremely open opinions over at least one of

the three variables, i.e., immigration to living quality, immigration to culture, or emotionally

attached to Europe, are in green (Lab_Pro) and the rest colored red (Lab_Oth).

Overall, given that recent research has linked negative immigration attitudes to anti-EU sen-

timents (Colantone and Stanig 2016), we conclude that both Conservative and Labour party sup-

porters are internally divided by Brexit attitudes. These results further demonstrate that cMCA

can identify latent traits often ignored by traditional scaling methods, that generalize across large

pre-defined groups. As we may expect, although the two parties are divided by Brexit attitudes,

the size of the pro-EU sub-group is significantly larger among Labour supporters, as compared to

Conservative ones.

The ESS 2018 analysis emphasizes an important component of cMCA—that is, the selection of

the background group is highly influential in deriving either meaningful or meaningless results.

8. All three variables are five-point scales where 1 refers to the feeling of extreme anti-EU or anti-immigrant and 5 to the

feeling of extreme pro-EU or pro-immigrant. Please refer to online Appendix B for more details.

Fujiwara and Liu 11While this is intuitive, given the basic conceit of contrastive learning methods, it is very impor-

tant to consider when using cMCA: if the selected target and background groups are highly similar,

cMCA may not be able to capture any informative patterns, as illustrated by the results in Figure 2a

and Figure 2b. Nevertheless, this “uninformative” situation can actually be informative when ex-

amined from a different perspective—researchers can apply the contrastive learning method to

any two groups to examine their level of similarity. From this perspective, the results of Figure 2a

and Figure 2b actually validate previous findings about the wave of ideological convergence be-

tween the two major parties in British politics.

BlackBox Result of UTAS 2012

M@A BDEFGH IJ KNOP QRST UVWX YZ[\]^_`

1.0

3

2

0.5

1

PC2

PC2

0.0

0

−0.5 1

abd

efg

2

hij

−1.0

0 1 2 3 4 5

−1.0 −0.5 0.0 0.5 1.0

PC1

PC1

(a) OOC (b) MCA

BlackBox Result of UTAS 2012 Ordinal IRT Result of UTAS 2012

1.0

2

0.5

0

PC2

PC2

0.0

−2

−0.5

−1.0

−4

−1.0 −0.5 0.0 0.5 1.0 −2 0 2 4

PC1 PC1

(c) BS (d) BMFA

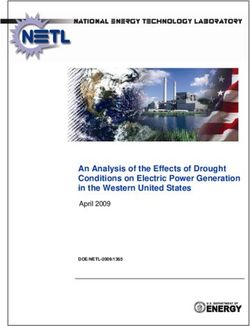

Figure 4. OOC, MCA, BS, and BMFA Results of UTAS 2012

3.2 Case Two: UTAS 2012—the Hidden Xenophobic Wing of the LDP

Next, we turn our attention to the 2012 UTokyo-Asahi Survey, conducted in Japan during their

House of Representatives election in 2012.9 For each election, UTAS surveys both candidates and

voters, and thus contains three sets of survey questions: candidate-specific, voter-specific, and

9. UTAS is conducted by Masaki Taniguchi of the Graduate Schools for Law and Politics, the University of Tokyo and the

Asahi News. The original data can be retrieved from http://www.masaki.j.u-tokyo.ac.jp/utas/utasindex.html.

Fujiwara and Liu 12shared questions. We focus on the voter-specific and shared questions only—we first select forty

questions which are also presented in UTAS 09 and recode this data through the aforementioned

procedure. With OOC, MCA, BS, and BMFA, we present the positions of all respondents who sup-

port either the Liberal Democratic Party (LDP), the Democratic Party of Japan (DPJ), or the Japan

Renewal Party (JRP) in Figure 4.

Similar to Figure 1, the UTAS results highlight how Japanese voters are highly mixed and over-

lapping along these dimensions—not one of the sub-figures of Figure 4 reveal any obvious patterns

that represent clear and distinct party lines. Indeed, these results are consistent with previous re-

search finding a downward trend in the ideological distinctions between Japanese parties, elites,

and voters (Endo and Jou 2014; Jou and Endo 2016; Miwa 2015). In short, while simple, left-right

ideology may still be the heuristic that Japanese voters rely on for determining their vote-choice,

the political culture of Japan has become decidedly more centrist. Given this high degree of mod-

eration, we apply cMCA with the manual-selection method to the UTAS 2012 to explore hidden

patterns within the Japanese electorate.

¯°±² ³´µ¶ ·¸¹º »¼½ ¾¿ÀÁ  ÃÄÅÆ cMCA (tg: LDP, bg: DPJ, : 1.6)

ÇÈÉ LDP_Anti

«¬® ÊËÌ 1.00

LDP_Oth

DPJ

§¨©ª 0.75

£¤¥¦ 0.50

¡¢ 0.25

cPC2

cPC2

0.00

0.25

0.50

0.75

1.00

1.00 klmn opqr stuv wxyz {|}~ 1.00 ÍÎÏÐ ÑÒÓÔ ÕÖ×Ø ÙÚÛÜ ÝÞßà áâãä åæçè éêëì

cPC1 cPC1 (Feelings to South Korea/China)

(a) Target: LDP, Background: DPJ (b) Target: LDP (color-coded by the attitudes to South

Korea/China), Background: DPJ

Figure 5. cMCA Results of UTAS 2012 (LDP versus DPJ)

As Figure 5 shows, when we assign LDP supporters to the target group and DPJ supporters

to the background group, cMCA identifies two subgroups, with minor overlap, within LDP sup-

porters. We start by manually setting α equal to 1 and find that LDP supporters can be divided

by DPJ supporters in the contrastive space; we then increase the value of α gradually (by 0.1) at

each iteration to adjust the position of every data-point, and finally, when α is set to 1.6, cMCA

shows that the LDP supporters (in blue color) are well divided by the DPJ supporters (in orange

color) along cPC1, as demonstrated in Figure 5a. Furthermore, based on the auxiliary informa-

tion provided in Figure 8a, we find that the top nine most influential variables in order of dividing

LDP supporters along cPC1 are: feeling close to South Korea (policy55), feeling close to Rus-

sia (policy55), feeling close to China (policy54), campaign contribution (policy50), party

control (policy52), diet (policy51), family form (policy43), US-Asia priority (policy47), and

electoral system (policy01). Upon closer investigation, we find that the first cPC is associated

with the LDP voters’ attitudes towards four foreign countries: South Korea, China, Russia, and the

U.S. Indeed, as demonstrated in Figure 8a, almost half of the top nine most influential variables

which disperse the LDP supporters along with cPC1 are related to these attitudes—feeling close

to South Korea, feeling close to Russia, feeling close to China (top three most influential vari-

Fujiwara and Liu 13ables), and US-Asia priority (the eighth most influential variable).

Furthermore, through category coordinates presented in Figure 8c, we find that the LDP sup-

porters who are located on the negative side of cPC1, in general, respond with 1 to the campaign

contribution, 5 to the feeling close to South Korea, 5 to the feeling close to China, and 1 to

the US-Asia priority questions.10 We speculate that one of the main latent traits to which cPC1

corresponds are attitudes towards Japan’s Asian neighbors: LDP supporters who are located on

the left of Figure 5a feel extremely distant to South Korea and China.11

We further divide LDP supporters into two subgroups and present them in Figure 5b: those

who feel extremely distant to South Korea or China are colored in green (LDP_Anti) and the rest

are colored in purple (LDP_Oth). We consider these feelings of extreme distance as anti-South

Korea and anti-China attitudes, respectively. Importantly, this xenophobia identified within the

LDP is consistent with the reality of current Japanese politics.12

Indeed, scholars have consistently identified a wave of xenophobic sentiments in Japan against

Korean, Chinese, and other peoples since the late 2000s—coined the “Action Conservative Move-

ment” (ACM) (Smith 2018). These new right-wing groups are considered to be quite different to

the traditional right-wing politicians and parties of post-war Japan. While these traditional par-

ties, which are the predecessors of the modern LDP and the Shinzo Abe administration, focused

on anti-communism and the Emperor-centered view of history and the state of nature, these new

parties are much more preoccupied with nativistic and xenophobic issues and policies (Gill 2018;

Smith 2018; Yamaguchi 2018). Interestingly, although these new right-wing groups in the LDP have

been identified and discussed by the news media and scholarly research, they are rarely identified

through surveys and traditional scaling methods. The use of cMCA on this data perfectly illustrates

the utility of this method in capturing influential features or categories that are substantively im-

portant, and which are often left unidentified by traditional methods.

4 Discussion: Comparing cMCA with Other Subgroup-Analysis Methods

Scaling has been widely used for both pattern recognition and latent-space derivation. Neverthe-

less, due to the structure of different datasets and the methodology behind these ordinary scaling

methods, the derived results are sometimes uninformative. In this article, we contribute to both

the scaling and contrastive learning literature by extending contrastive learning to MCA enabling

researchers to derive contrasted dimensions using categorical data.

Through the analytical results from two surveys, the ESS 2018 and UTAS 2012, we illustrate the

two main advantages of cMCA, relative to traditional scaling methods. First, cMCA can identify sub-

stantively important dimensions and divisions among (sub)groups that are missed by traditional

methods. Second, while cMCA primarily explores principal directions for individual groups, it can

still derive dimensions that can be applied to multiple groups. As demonstrated in Figure 3, when

Conservative and Labour supporters are distributed almost identically, cMCA is able to identify the

Brexit division that exists in both parties.

It is also important to note that cMCA, and contrastive learning more generally, is different from

ordinary subgroup-analysis methods: almost all standard methods for subgroup-analysis require

researchers to have prior knowledge about how data should be “subgrouped.” For example, as

10. According to both Figure 8a and Figure 8b, the level of 99 of feeling close to South Korea seems to be the most

“powerful” category which pulls LDP supporters in the negative direction of cPC1. However, based on both Figure 8c and

Figure 8d, one can find that voters whose positions are extremely positive on cPC2 are more likely to not respond (99) to

feeling close to South Korea; and on the contrary, voters who are extremely negative on cPC1 are more likely to respond

with 5 to feeling close to South Korea.

11. Both variables are five-point Likert scales where 1 refers to feeling extremely close to South Korea/China and 5 refers

to feeling extremely not close to South Korea/China. Please refer to online Appendix B for more details.

12. Similar to the ESS 2018, cPC2 in Figure 5 represents mostly non-responses/missing values in certain variables so the

discussion of that dimension is ignored in this section.

Fujiwara and Liu 14compared with two of the most popular of these methods, class-specific MCA (CSA) and subgroup

MCA (sMCA), cMCA allows researchers to agnostically explore all possible latent traits from differ-

ent perspectives in the space. In other words, while conducting cMCA, without prior knowledge,

researchers need only apply different values of α , either with manual- or auto-selection, to derive

latent dimensions or traits which could subgroup data in meaningful ways.

In contrast, both CSA and sMCA requires researchers to subjectively subset/subgroup the origi-

nal data first and then compare the derived patterns with the reference group, usually the original

complete data. The ideas behind CSA and sMCA are similar: CSA is used to study whether a pre-

defined subset of data-points has a different latent pattern or not; and sMCA is used to explore

whether data-points distribute differently after excluding certain subgroup(s) from original data

(Greenacre and Pardo 2006; Le Roux and Rouanet 2010). Therefore, without any prior knowledge,

it is almost impossible for researchers to effectively apply CSA and sMCA to objectively explore

meaningful subgroups, especially when data is high-dimensional and unstructured, such as in our

two examples. This is because both datasets have a considerable amount of missing values and ac-

tive variables/categories. Given that both CSA and sMCA require researchers to manually compare

the latent distribution of every possible subset of data, as one can imagine, this issue becomes

much worse when the number of dimensions and missing values of data increases.

This comparison by no means indicates that cMCA and contrastive learning are superior to CSA,

sMCA, or any existing subgroup-analysis methods. Rather, it shows how cMCA is an additional tool

for researchers to agnostically explore latent traits. In that vein, we believe that this new approach

can complement the existing subgroup-analysis methods through providing preliminary heuris-

tics regarding hidden patterns within data. There are several use-cases for cMCA and contrastive

learning, in general. First, cMCA can be used for analyzing covariate-balance between treatment

and control groups in experiments; as demonstrated by Figure 2, cMCA instead can be utilized to

explore the level of similarity of two sets of identical active variables, and therefore, if there are

any categories or variables specific to either group, these results indicate potential issues regard-

ing the procedure of randomization.

Second, cMCA can be applied to substantive research as well. For instance, given that partisan

lines among British voters are not as clear as among American voters, a derived “issue cleavage”

from cMCA can be a good source of studying affective polarization (see Iyengar et al. 2019) by po-

litical issues instead of by party ID. In that vein, it has been noted that traditional scaling methods

usually classify the U.S. Congressperson group known as the “Squad” as “moderate Democrats”

based on their voting patterns. While clearly not moderate, this is due to how they sometimes

vote against with their Democratic colleagues’ more moderate policies (Lewis et al. 2019). Through

cMCA and contrastive learning, researchers could identify the specific kinds of bills that the “Squad”

typically disagree with other Democrats on so as to better understand the cleavage between the

progressive and moderate wings of the Democratic Party.

Supplementary Material

For coding scheme, please visit online Appendix B

References

Abid, A., M. J. Zhang, V. K. Bagaria, and J. Zou. 2018. “Exploring Patterns Enriched in a Dataset with Contrastive

Principal Component Analysis.” Nature Communications 9 (1): 1–7.

Abid, A., and J. Zou. 2019. “Contrastive Variational Autoencoder Enhances Salient Features.” arXiv:1902.04601.

Adams, J., J. Green, and C. Milazzo. 2012a. “Has the British Public Depolarized along with Political Elites? An

American Perspective on British Public Opinion.” Comparative Political Studies 45 (4): 507–530.

Fujiwara and Liu 15Adams, J., J. Green, and C. Milazzo. 2012b. “Who Moves? Elite and Mass-Level Depolarization in Britain, 1987–

2001.” Electoral Studies 31 (4): 643–655.

Aldrich, J. H., and R. D. McKelvey. 1977. “A Method of Scaling with Applications to the 1968 and 1972 Presi-

dential Elections.” American Political Science Review 71 (1): 111–130.

Armstrong, D., R. Bakker, R. Carroll, C. Hare, K. Poole, and H. Rosenthal. 2014. Analyzing Spatial Models of

Choice and Judgment with R. FL: CRC Press.

Brady, H. 1990. “Dimensional Analysis of Ranking Data.” American Journal of Political Science, 1017–1048.

Clinton, J., S. Jackman, and D. Rivers. 2004. “The Statistical Analysis of Roll Call Data.” American Political Sci-

ence Review 98 (2): 355–370.

Colantone, I., and P. Stanig. 2016. “Global Competition and Brexit.” American Political Science Review 112 (2):

201–218.

Coombs, C. H. 1964. A Theory of Data. New York: Wiley.

Cutts, D., M. Goodwin, O. Heath, and P. Surridge. 2020. “Brexit, the 2019 General Election and the Realignment

of British Politics.” The Political Quarterly 91 (1): 7–23.

Davis, D., K. Dowley, and B. Silver. 1999. “Postmaterialism in World Societies: Is It Really a Value Dimension?”

American Journal of Political Science 43 (3): 935–962.

Dinkelbach, W. 1967. “On nonlinear fractional programming.” Management Science 13 (7): 492–498.

Endo, M., and W. Jou. 2014. “How Does Age Affect Perceptions of Parties’ Ideological Locations?” Japanese

Journal of Electoral Studies 30 (1): 96–112.

Enelow, J., and M. Hinich. 1984. The Spatial Theory of Voting: An Introduction. Cambridge University Press.

Fujiwara, T., O.-H. Kwon, and K.-L. Ma. 2020. “Supporting Analysis of Dimensionality Reduction Results with

Contrastive Learning.” IEEE Transactions on Visualization and Computer Graphics 26 (1): 45–55.

Fujiwara, T., J. Zhao, F. Chen, and K.-L. Ma. 2020. “A Visual Analytics Framework for Contrastive Network Anal-

ysis.” In Proceedings of IEEE Conference on Visual Analytics Science and Technology, 48–59.

Fujiwara, T., J. Zhao, F. Chen, Y. Yu, and K.-L. Ma. 2020. “Interpretable Contrastive Learning for Networks.”

arXiv:2005.12419.

Ge, R., and J. Zou. 2016. “Rich Component Analysis.” In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine

Learning, 48:1502–1510.

Gill, T. 2018. “The Nativist Backlash: Exploring the Roots of the Action Conservative Movement.” Social Science

Japan Journal 21 (2): 175–192.

Greenacre, M. 2017. Correspondence Analysis in Practice. New York: Chapman & Hall/CRC.

Greenacre, M., and R. Pardo. 2006. “Subset Correspondence Analysis: Visualizing Relationships Among a Se-

lected Set of Response Categories from a Questionnaire Survey.” Sociological Methods & Research 35 (2):

193–218.

Grimmer, J., and G. King. 2011. “General Purpose Computer-Assisted Clustering and Conceptualization.” In

Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 108:2643–2650. 7. National Acad Sciences.

Hare, C., D. A. Armstrong, R. Bakker, R. Carroll, and K. T. Poole. 2015. “Using Bayesian Aldrich-McKelvey Scaling

to Study Citizens’ Ideological Preferences and Perceptions.” American Journal of Political Science 59 (3):

759–774.

Hare, C., T.-P. Liu, and R. N. Lupton. 2018. “What Ordered Optimal Classification Reveals about Ideological

Structure, Cleavages, and Polarization in the American Mass Public.” Public Choice 176 (1-2): 57–78.

Fujiwara and Liu 16Harris, D., and S. Harris. 2010. Digital Design and Computer Architecture. CA: Morgan Kaufmann Publishers.

Heath, O., and M. Goodwin. 2017. “The 2017 General Election, Brexit and the Return to Two-Party Politics: An

Aggregate-Level Analysis of the Result.” The Political Quarterly 88 (3): 345–358.

Hix, S., A. Noury, and G. Roland. 2006. “Dimensions of Politics in the European Parliament.” American Journal

of Political Science 50 (2): 494–520.

Hjellbrekke, J., and O. Korsnes. 1993. “Field Analysis, MCA and Class Specific Analysis: Analysing Structural

Homologies Between, and Variety Within Subfields in the Norwegian Field of Power.” In Empirical In-

vestigations of Social Space, edited by B. J´’org, L. Frédéric, B. Le Roux, and A. Schmitz, 43–60. Cham,

Switzerland: Springer.

Hobolt, S. B., T. Leeper, and J. Tilley. 2018. “Divided by the Vote: Affective Polarization in the Wake of the Brexit

Referendum.” British Journal of Political Science, https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007123420000125.

Imai, K., J. Lo, and J. Olmsted. 2016. “Fast Estimation of Ideal Points with Massive Data.” American Political

Science Review 110 (4): 631–656.

Iyengar, S., Y. Lelkes, M. Levendusky, N. Malhotra, and S. J. Westwood. 2019. “The Origins and Consequences

of Affective Polarization in the United States.” Annual Review of Political Science 22:129–146.

Jacoby, W. G. 1999. “Levels of Measurement and Political Research: An Optimistic View.” American Journal of

Political Science 43 (1): 271–301.

Jou, W., and M. Endo. 2016. “Ideological Understanding and Voting in Japan: A Longitudinal Analysis.” Asian

Politics & Policy 8 (3): 456–473.

Le Roux, B., and H. Rouanet. 2010. Quantitative Applications in the Social Sciences: Multiple Correspondence

Analysis. CA: SAGE Publications, Inc.

Leach, R. 2015. Political Ideology in Britain. London: Macmillan International Higher Education.

Lewis, J. B., K. Poole, H. Rosenthal, A. Boche, A. Rudkin, and L. Sonnet. 2019. Voteview: Congressional Roll-Call

Votes Database. https://voteview.com/.

Martin, A., and K. Quinn. 2002. “Dynamic Ideal Point Estimation via Markov Chain Monte Carlo for the US

Supreme Court, 1953–1999.” Political Analysis 10 (2): 134–153.

Martin, A., K. Quinn, and J. H. Park. 2011. “MCMCpack: Markov Chain Monte Carlo in R.” Journal of Statistical

Software 42 (9): 1–21.

McCarty, N., K. Poole, and H. Rosenthal. 2001. “The Hunt for Party Discipline in Congress.” American Political

Science Review 95 (3): 673–687.

Miwa, H. 2015. “Voters’ Left–Right Perception of Parties in Contemporary Japan: Removing the Noise of Mis-

understanding.” Japanese Journal of Political Science 16 (1): 114–137.

Monroe, B., M. Colaresi, and K. Quinn. 2008. “Fightin’ Words: Lexical Feature Selection and Evaluation for

Identifying the Content of Political Conflict.” Political Analysis 16 (4): 372–403.

Pagès, J. 2014. Multiple Factor Analysis by Example Using R. FL: CRC Press.

Poole, K. 1998. “Recovering a Basic Space from a Set of Issue Scales.” American Journal of Political Science 42

(3): 954–993.

. 2000. “Nonparametric Unfolding of Binary Choice Data.” Political Analysis 8 (3): 211–237.

Poole, K., and H. Rosenthal. 1991. “Patterns of Congressional Voting.” American Journal of Political Science 35

(1): 228–278.

Quinn, K. 2004. “Bayesian Factor Analysis for Mixed Ordinal and Continuous Responses.” Political Analysis 12

(4): 338–353.

Fujiwara and Liu 17You can also read