Clinical Drug Testing in Primary Care - TAP 32 Technical Assistance Publication Series - SAMHSA Store

←

→

Page content transcription

If your browser does not render page correctly, please read the page content below

Clinical Drug

Testing in

Primary Care

Technical Assistance Publication Series

TAP 32Clinical Drug Testing in

Primary Care

TAP

Technical Assistance Publication Series

32

U.S. DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH AND HUMAN SERVICES

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration

Center for Substance Abuse Treatment

1 Choke Cherry Road

Rockville, MD 20857Clinical Drug Testing in Primary Care

Acknowledgments Electronic Access and Copies

This publication was prepared for the of Publication

Substance Abuse and Mental Health This publication may be ordered from

Services Administration (SAMHSA), by SAMHSA’s Publications Ordering Web page

RTI International and completed by the at http://store.samhsa.gov. Or, please call

Knowledge Application Program (KAP), SAMHSA at 1-877-SAMHSA-7 (1-877-726

contract numbers 270-04-7049 and 270 4727) (English and Español). The document

09-0307, a Joint Venture of The CDM may be downloaded from the KAP Web site at

Group, Inc., and JBS International, Inc., http://kap.samhsa.gov.

with SAMHSA, U.S. Department of Health

and Human Services (HHS). Christina

Currier served as the Contracting Officer’s

Representative.

Recommended Citation

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services

Administration. Clinical Drug Testing

Disclaimer in Primary Care. Technical Assistance

Publication (TAP) 32. HHS Publication No.

The views, opinions, and content of this (SMA) 12-4668. Rockville, MD: Substance

publication are those of the authors and do Abuse and Mental Health Services

not necessarily reflect the views, opinions, or Administration, 2012.

policies of SAMHSA or HHS.

Originating Office

Public Domain Notice

Quality Improvement and Workforce

All materials appearing in this publication Development Branch, Division of Services

except those taken from copyrighted Improvement, Center for Substance Abuse

sources are in the public domain and may Treatment, Substance Abuse and Mental

be reproduced or copied without permission Health Services Administration, 1 Choke

from SAMHSA. Citation of the source is Cherry Road, Rockville, MD 20857.

appreciated. However, this publication may

not be reproduced or distributed for a fee HHS Publication No. (SMA) 12-4668

without the specific, written authorization Printed 2012

of the Office of Communications, SAMHSA,

HHS.

iiContents

Chapter 1—Introduction . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 1

Audience for the TAP. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 1

Organization of the TAP . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 1

Reasons To Use Clinical Drug Testing in Primary Care . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 2

Primary Care and Substance Use Disorders . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 2

Development of Drug Testing . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 3

Workplace Drug Testing . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 4

Drug Testing in Substance Abuse Treatment and Healthcare Settings . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 5

Differences Between Federal Workplace Drug Testing and Clinical Drug Testing. . . . . . 6

Caution . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 6

Chapter 2—Terminology and Essential

Concepts in Drug Testing . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 9

Drug Screening and Confirmatory Testing . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 9

Testing Methods. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 10

Test Reliability. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 10

Window of Detection . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 11

Cutoff Concentrations . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 12

Cross-Reactivity . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 12

Drug Test Panels . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 13

Test Matrix . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 14

Point-of-Care Tests . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 14

Adulterants . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 14

Specimen Validity Tests . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 15

iiiClinical Drug Testing in Primary Care

Chapter 3—Preparing for Drug Testing . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 17

Deciding Which Drugs To Screen and Test For . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 17

Choosing a Matrix . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 17

Specimen Availability . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 20

Oral Fluid . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 20

Sweat . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 20

Blood . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 21

Hair . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 21

Breath . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 22

Meconium . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 23

Selecting the Initial Testing Site: Laboratory or Point-of-Care . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 23

Collection Devices . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 23

Laboratory Tests . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 24

Advantages and Disadvantages of Testing in a Laboratory . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 25

Considerations for Selecting a Laboratory . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 25

Point-of-Care Tests . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 26

Advantages and Disadvantages of POCTs . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 27

Considerations for Selecting POCT Devices . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 28

Implementing Point-of-Care Testing . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 29

Preparing Clinical and Office Staffs for Testing . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 30

Preparing a Specimen Collection Site. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 30

Chapter 4—Drug Testing in Primary Care . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 31

Uses of Drug Testing in Primary Care . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 31

Monitoring Prescription Medication Use . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 32

Management of Chronic Pain With Opioids . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 32

Evaluation of Unexplained Symptoms or Unexpected Responses to Treatment . . . . 32

Patient Safety. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 33

ivContents

Pregnancy . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 33

Psychiatric Care . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 34

Monitoring Office-Based Pharmacotherapy for Opioid Use Disorders . . . . . . . . . . . . 34

Detection of Substance Use Disorders . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 34

Initial Assessment of a Person With a Suspected SUD . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 35

Talking With Patients About Drug Testing . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 38

Cultural Competency and Diversity . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 39

Monitoring Patients . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 40

Patients With an SUD . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 40

Monitoring Patients Receiving Opioids for Chronic Noncancer Pain . . . . . . . . . . . . . 41

Ensuring Confidentiality and 42 CFR Part 2. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 42

Preparing for Implementing Drug Testing. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 43

Collecting Specimens . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 43

Conducting POCTs . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 44

Interpreting Drug Test Results . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 44

Result: Negative Specimen . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 45

Result: Positive Specimen . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 46

Result: Adulterated or Substituted Specimen . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 47

Result: Dilute Specimen . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 48

Result: Invalid Urine Specimen . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 48

Frequency of Testing . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 49

Documentation and Reimbursement . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 49

Documentation . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 49

Reimbursement . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 50

Chapter 5—Urine Drug Testing for Specific Substances . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 51

Window of Detection . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 51

Specimen Collection . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 52

vClinical Drug Testing in Primary Care

Adulteration, Substitution, and Dilution . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 52

Adulteration . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 52

Substitution . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 53

Dilute Specimens . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 53

Cross-Reactivity . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 54

Alcohol . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 54

Amphetamines . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 55

Barbiturates . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 56

Benzodiazepines. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 56

Cocaine . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 57

Marijuana/Cannabis . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 58

Opioids . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 58

Other Substances of Abuse . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 60

PCP . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 60

Club Drugs . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 60

LSD . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 61

Inhalants . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 61

Appendix A—Bibliography . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 63

Appendix B—Laboratory Initial Drug-Testing Methods . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 71

Appendix C—Laboratory Confirmatory Drug-Testing Methods . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 73

Appendix D—Laboratory Specimen Validity-Testing Methods . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 75

Appendix E—Glossary . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 77

Appendix F—Expert Panel . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 79

Appendix G—Consultants and Field Reviewers . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 81

Appendix H—Acknowledgments . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 83

viExhibits

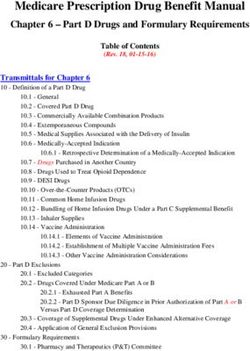

Exhibit 1-1. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services

Federal Mandatory Workplace Guidelines Cutoff Concentrations

for Initial and Confirmatory Drug Tests in Urine . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 5

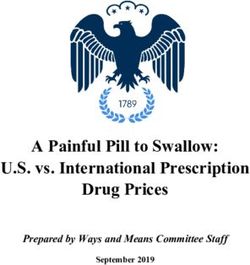

Exhibit 1-2. Comparison of Federal Workplace

Drug Testing and Clinical Drug Testing . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 7

Exhibit 2-1. Window of Detection for Various Matrices . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 12

Exhibit 3-1. Advantages and Disadvantages

of Different Matrices for Drug Testing . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 18

Exhibit 3-2. Comparison of Laboratory Tests and POCTs . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 24

Exhibit 3-3. Federal and State Regulations . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 25

Exhibit 4-1. Motivational Interviewing Resources . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 35

Exhibit 4-2. The CAGE-AID Questions . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 36

Exhibit 4-3. Brief Intervention Elements: FRAMES . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 36

Exhibit 4-4. Patient Flow Through Screening

and Referral in Primary Care . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 37

Exhibit 5-1. Barbiturates—Window of Detection . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 56

Exhibit 5-2. Benzodiazepines—Window of Detection . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 57

Exhibit 5-3. Opioids—Window of Detection . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 59

viiChapter 1—Introduction

Audience for the TAP

In This Chapter

This Technical Assistance Publication (TAP), Clinical Drug

• Audience for the Tap Testing in Primary Care, is for clinical practitioners—

• Organization of the physicians, nurse practitioners, and physician assistants—

Tap who provide primary care in office settings and community

health centers. The publication provides information that

• Reasons To Use practitioners need when deciding whether to introduce drug

Clinical Drug Testing testing in their practices and gives guidance on implementing

in Primary Care drug testing.

• Primary Care and

The TAP does not address drug testing for law enforcement

Substance Use

or legal purposes, nor does it include testing for the use of

Disorders

anabolic steroids or performance-enhancing substances.

• Development of Drug This TAP describes some of the ways that drug testing can

Testing contribute to the assessment, diagnosis, and treatment

of patients seen in primary care, the management of the

• Workplace Drug

treatment of chronic pain, and the identification and

Testing

treatment of substance use disorders.

• Drug Testing in

Substance Abuse

Treatment and Organization of the TAP

Healthcare Settings

This chapter briefly describes the role of drug testing in

• Differences Between primary care settings and its historical roots in workplace

Federal Workplace testing. Chapter 2 defines the terms and practices used in

and Clinical Drug drug testing. Chapter 3 presents the mechanics of testing

Testing and describes the steps that primary care practitioners can

• Caution take to prepare themselves, their staffs, and their office

spaces for drug testing. Chapter 4 provides information

about implementing testing in clinical practice. Important

aspects of urine drug testing for specific drugs are presented

in Chapter 5. Appendices A–H include the bibliography;

overviews of technical information on specific tests used

for initial or screening tests, confirmatory tests, and

specimen validity tests; a glossary of terms; the members

of the expert panel, consultants, and field reviewers; and

acknowledgments.

1Clinical Drug Testing in Primary Care

Reasons To Use Clinical Drug • Can affect clinical decisions about

Testing in Primary Care pharmacotherapy, especially with

controlled substances.

The term drug testing can be confusing

because it implies that the test will detect • Increases the safety of prescribing

the presence of all drugs. However, drug medications by identifying the potential for

tests target only specific drugs or drug overdose or serious drug interactions.

classes and can detect substances only • Helps clinicians assess patient use of

when they are present above predetermined opioids for chronic pain management or

thresholds (cutoff levels). The term drug compliance with pharmacotherapy for

screening can also be deceptive because it opioid maintenance treatment for opioid

is often used to describe all types of drug use disorders.

testing. However, drug screening is usually

used in forensic drug testing to refer to the • Helps the clinician assess the efficacy of

use of immunoassay tests to distinguish the treatment plan and the current level

specimens that test negative for a drug and/or of care for chronic pain management and

metabolite from positive specimens. For the substance use disorders (SUDs).

purpose of this TAP, the term drug testing is • Prevents dangerous medication

used. interactions during surgery or other

medical procedures.

When used appropriately, drug testing can

be an important clinical tool in patient care. • Aids in screening, assessing, and

The types of clinical situations in which diagnosing an SUD, although drug testing

clinical drug testing can be used include is not a definitive indication of an SUD.

pain management with opioid medications,

• Identifies women who are pregnant, or who

office-based opioid treatment, primary

want to become pregnant, and are using

care, psychiatry, and other situations when

drugs or alcohol.

healthcare providers need to determine

alcohol or other substance use in patients. • Identifies at-risk neonates.

Drug testing is also used to monitor patients’

• Monitors abstinence in a patient with a

prescribed medications with addictive

known SUD.

potential. Patients sometimes underreport

drug use to medical professionals (Chen, • Verifies, contradicts, or adds to a patient’s

Fang, Shyu, & Lin, 2006), making some self-report or family member’s report of

patients’ self-reports unreliable. Drug substance use.

test results may provide more accurate

information than patient self-report. • Identifies a relapse to substance use.

Although drug testing can be a useful tool

for making clinical decisions, it should not be

the only tool. When combined with a patient’s Primary Care and Substance Use

history, collateral information from a spouse Disorders

or other family member (obtained with

Practitioners can use drug testing to help

permission of the patient), questionnaires,

monitor patients’ use of prescribed scheduled

biological markers, and a practitioner’s

medications, as part of pharmacovigilance,

clinical judgment, drug testing provides

and to help identify patients who may need

information that:

an intervention for SUDs.

• Can affect clinical decisions on a patient’s

For the purpose of this TAP, substances

substance use that affects other medical

refers to alcohol and drugs that can be

conditions.

abused. As defined by the Diagnostic and

Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders,

2Chapter 1―Introduction

Fourth Edition, Text Revision (DSM diagnosed with SUDs. Moreover, the number

IV-TR; American Psychiatric Association of people ages 12 or older seeking help for

[APA], 2000), a substance-related disorder SUDs from a doctor in private practice

is a disorder related to the consumption of increased from 460,000 in 2005 to 672,000 in

alcohol or of a drug of abuse (APA, 2000). 2008 (SAMHSA, 2006; SAMHSA, 2009).

Substance use disorders (SUDs) includes

both substance dependence and substance Despite the potential benefits of drug testing

abuse (APA, 2000). Substance dependence (such as monitoring pain medication) to

refers to “a cluster of cognitive, behavioral, patient care, few primary care practitioners

and physiological symptoms indicating that use it. For example, a small study conducted

the individual continues use of the substance on the medical management of patients with

despite significant substance-related chronic pain in family practices found that

problems. There is a pattern of repeated self- only 8 percent of physicians surveyed used

administration that can result in tolerance, drug testing (Adams et al., 2001).

withdrawal, and compulsive drug-taking

behavior” (APA, 2000). Substance abuse

refers to “a maladaptive pattern of substance Development of Drug Testing

use manifested by recurrent and significant

adverse consequences related to the repeated Drug testing performed for clinical reasons

use of substances” (APA, 2000). In this TAP, differs substantially from workplace drug

the term substance abuse is sometimes used testing programs. However, clinical drug

to denote both substance abuse and substance testing draws on the experience of Federal

dependence as they are defined in the DSM- Mandatory Workplace Drug Testing and,

IV-TR (APA, 2000). to understand drug testing, a review of

workplace drug testing may be helpful. An

SUDs can have serious medical complications important reason for clinical practitioners

and serious psychosocial consequences and to become familiar with Federal Mandatory

can be fatal. Treatment of other medical Workplace Drug Testing is that the majority

disorders (e.g., HIV/AIDs, pancreatitis, of drug testing is done for workplace

hypertension, diabetes, liver disorders) may purposes. For this reason, most laboratories

be complicated by the presence of an SUD. and many point-of-care tests (POCTs) use

As the front line in health care, medical the cutoff concentrations established by the

practitioners are ideally situated to identify Mandatory Guidelines for Federal Workplace

substance use problems. The 2009 National Drug Testing Programs, discussed in Chapter 2.

Survey on Drug Use and Health (Substance

Abuse and Mental Health Services There are three categories of drug testing:

Administration [SAMHSA], 2010a) found that (1) federally regulated for selected Federal

23.5 million (9.3 percent) persons ages 12 or employees (including military personnel

older needed treatment for an illicit drug1 and those in safety-sensitive positions);

or alcohol use problem. Of this population, (2) federally regulated for non-Federal

only 2.6 million (1.0 percent) persons ages employees in safety-sensitive positions (i.e.,

12 or older (11.2 percent of those who needed airline and railroad personnel, commercial

treatment) received treatment at a specialty truckers, school bus drivers); and (3)

facility. Thus, 20.9 million (8.3 percent) of the nonregulated for non-Federal employees.

population age 12 or older needed substance Commercial truck drivers, railroad employees

abuse treatment but did not receive it in the and airline personnel make up the largest

past year (SAMHSA, 2010a). Therefore, a group of individuals being drug tested.

visit to a primary care practitioner may be

an excellent opportunity for such people to be The purpose of both Federal (always

regulated) and non-Federal (may be

1

Includes the nonmedical use of prescription-type nonregulated) workplace drug testing is to

pain relievers, tranquilizers, stimulants, and sedatives. ensure safety in the workplace by preventing

3Clinical Drug Testing in Primary Care

the hiring of individuals who use illicit drugs metabolites (SAMHSA, 2008):

and identifying employees who use illicit

drugs. • Amphetamines (amphetamine,

methamphetamine)

• Cocaine metabolites

Workplace Drug Testing

• Marijuana metabolites

Drug-testing methods have been available

for approximately 50 years (Reynolds, 2005). • Opiate metabolites (codeine, morphine)

Because of drug use in the U.S. military, by • Phencyclidine (PCP)

1984, the military established standards for

laboratories and testing methods and created These substances are generally called the

the first system for processing large numbers “Federal 5,” but over the years they have also

of drug tests under strict forensic conditions been called the “NIDA 5” and “SAMHSA 5.”

that could be defended in a court of law. The Federal mandatory guidelines have been

updated and revised over the years to reflect

In 1986, an Executive Order initiated the technological and process changes (Exhibit

Federal Drug-Free Workplace Program that 1-1). The guidelines, last updated in 2008

defined responsibilities for establishing a (effective May 1, 2010), are available at http://

plan to achieve drug-free workplaces. In dwp.samhsa.gov/DrugTesting/Level_1_Pages/

1987, Public Law 100-71 outlined provisions mandatory_guidelines5_1_10.html.

for drug testing programs in the Federal

sector. In 1988, Federal mandatory guidelines Revisions for testing of other matrixes (e.g.,

set scientific and technical standards for hair, oral fluid, sweat) and the use of POCTs

testing Federal employees. In 1989, the U.S. were proposed in 2004 (SAMHSA, 2008), but

Department of Transportation (DOT) issued have not been finalized.

regulations requiring the testing of nearly 7

million private-sector transportation workers Although Federal agencies are required

in industries regulated by DOT. to have drug-free workplace programs for

their employees, private-sector employers

The Federal mandatory guidelines included that do not fall under Federal regulations

procedures, regulations, and certification can establish their own drug-free workplace

requirements for laboratories; outlined the programs and establish their own

drugs for which testing was to be performed; regulations, testing matrices, and testing

set cutoff concentrations; and stated reporting methods. Non-Federal employees can be

requirements that included mandatory medical tested for a broader range of drugs than the

reviews by a specially trained physician federally mandated drugs. Many States have

Medical Review Officer (MRO). Because a laws and regulations that affect when, where,

positive result does not automatically identify and how employers can implement drug-free

an employee or job applicant as a person workplace programs (search in http://www.

who uses illicit drugs, the MRO interviews dol.gov).

the donor to determine whether there is an

alternative medical explanation for the drug Laboratories are accredited by the National

found in the specimen. The Federal mandatory Laboratory Certification Program (NLCP)

guidelines recommended that the initial to meet the minimum requirements of the

screening test identify the presence of the Federal mandatory guidelines. This program

following commonly abused drugs or their resides in SAMHSA in the Department of

Health and Human Services (HHS).

4Chapter 1―Introduction

Exhibit 1-1. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Federal Mandatory Workplace

Guidelines Cutoff Concentrations for Initial and Confirmatory Drug Tests in Urine

Federal Cutoff

Initial Test Analyte Concentrations (ng/mL)

Marijuana metabolites 50

Cocaine metabolites 150

Opiate metabolites (codeine/morphine ) 1

2,000

6-Acetylmorphine (6-AM) 10

Amphetamines (Amphetamine /methamphetamine)

2

500

Phencyclidine (PCP) 25

Methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA) 500

Federal Cutoff

Confirmatory Test Analyte

Concentrations (ng/mL)

Amphetamine 250

Methamphetamine3 250

MDMA 250

Methylenedioxyamphetamine (MDA) 250

Methylenedioxyethylamphetamine (MDEA) 250

Cannabinoid metabolite (delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol-9-carboxylic acid) 15

Cocaine metabolite (benzoylecgonine) 100

Codeine 2,000

Morphine 2000

6-Acetylmorphine (6-AM) 10

PCP 25

Source: SAMHSA (2008).

1

Morphine is the target analyte for codeine/morphine testing.

2

Methamphetamine is the target analyte for amphetamine/methamphetamine testing.

3

To be reported positive for methamphetamine, a specimen must also contain amphetamine at a concentration equal to, or greater

than, 100 ng/mL.

Drug Testing in Substance Abuse testing for drug treatment programs under

Treatment and Healthcare Settings Federal mandates.

Substance abuse treatment programs Drug testing in SUD treatment is:

use drug testing extensively. Drug

testing for patient monitoring in SUD • Part of the initial assessment of a patient

treatment programs began considerably being evaluated for a diagnosis of an SUD;

before workplace drug testing and has

• A screen to prevent potential adverse

become an integral part of many drug

effects of pharmacotherapy (e.g., opioid

treatment programs for patient evaluation

screen prior to starting naltrexone);

and monitoring. By 1970, the Federal

Government implemented specific mandatory • A component of the treatment plan for an

testing requirements for treatment programs SUD;

that were licensed by the U.S. Food and

• A way to monitor the patient’s use

Drug Administration to dispense methadone

of illicit substances or adherence to

or that received Federal funds. During the

pharmacotherapy treatment for SUDs; and

1970s, Federal agencies developed a program

to monitor laboratories performing drug • A way to assess the efficacy of the

treatment plan (i.e., level of care).

5Clinical Drug Testing in Primary Care

Drug testing can also be used to document drug testing in clinical settings (Exhibit 1-2).

abstinence for legal matters, disability Despite the differences, Federal workplace

determinations, custody disputes, or drug-testing guidelines and cutoff

reinstatement in certain professions (e.g., concentrations continue to influence clinical

lawyers, healthcare providers, airline pilots). drug testing. For example, many laboratories

and POCT devices test either for the federally

Drug testing is also useful in healthcare mandated drugs or for the same drugs, but

settings: using modified cutoff concentrations as the

default drug-testing panel. These panels are

• For determining or refuting perinatal not suitable for clinical drug testing because

maternal drug use; these panels do not detect some of the most

• As an adjunct to psychiatric care and commonly prescribed pain medications, such

counseling; as synthetic opioids (e.g., hydrocodone) and

anxiolytics (e.g., benzodiazepines, such as

• For monitoring medication compliance alprazolam), or other drugs of abuse. Initial

during pain treatment with opioids; screening test cutoffs may not be low enough

for clinical practice in some instances (e.g.,

• For monitoring other medications that

cannabinoids, opiates, amphetamines).

could be abused or diverted; and

• To detect drug use or abuse where it may

have a negative impact on patient care in Caution

other medical specialties.

Trends in drug use and abuse change over

See Chapter 4 for more information about the time and can necessitate a change in drug

use of drug testing in clinical situations. testing panels. The technology for drug

testing evolves quickly, new drug-testing

devices become available, and old tests are

Differences Between Federal refined. Although this TAP presents current

Workplace Drug Testing and information, readers are encouraged to

continue to consult recent sources. Wherever

Clinical Drug Testing possible, the TAP refers readers to resources

Important distinctions exist between drug that provide up-to-date information.

testing in Federal workplace settings and

6Chapter 1―Introduction

Exhibit 1-2. Comparison of Federal Workplace Drug Testing and Clinical Drug Testing

Component Federal Workplace Testing Clinical Testing

Specimen • Urine • Primarily urine, some oral fluid tests

Collection • Federal regulations stipulate specimen • Practitioners and clinical staff (hospital or clinical

Procedures collection procedures. laboratory) follow procedures for properly

• Policies minimize mistaken identity of identifying and tracking specimens.

specimens and specimen adulteration. • In general, rigorous protocols are not used.

For example, in criminal cases, Chain of custody usually is not required;

chain-of-custody policies require however, laboratories under College of American

identification of all persons handling Pathologists accreditation and/or State licensure

specimen packages. In administrative should have specimen collection, handling, and

cases (e.g., workplace testing), specimen storage protocols in place.

packages may be handled without

individual identification. Only those persons

handling the specimen itself need to be

identified.

Specimen • Extensive testing verifies that specimen • In general, laboratories do not conduct the

Validity Testing substitution or adulteration has not same validity testing as is required for Federal

occurred. workplace testing.

• Validation often is not required with clinical use

of POCT.

• Some laboratories record the temperature of

the specimen and test for creatinine and specific

gravity of urine specimens.

• Pain management laboratories may have

specimen validity testing protocols that involve

creatinine with reflexive specific gravity, pH,

and/or oxidants in place.

Confirmatory • Gas chromatography/mass spectrometry • GC/MS, liquid chromatography/mass

Methods (GC/MS) spectrometry (LC/MS), liquid chromatography/

mass spectrometry/mass spectrometry LC/MS/

MS.

Testing for • Testing is for the federally mandated drugs. • No set drug testing panel.

Predetermined • Drugs tested vary by laboratory and within

Substances laboratories.

• Clinicians may specify which drugs are tested for

and usually select panels (menus) that test for

more than the federally mandated drugs. Various

panels exist (e.g., pain).

Cutoff • Cutoff concentrations have been • Cutoff concentrations vary.

Concentrations established for each drug. • In some circumstances, test results below the

• A test detecting a concentration at or cutoff concentration may be clinically significant.

above the cutoff is considered to be a • Urine and oral fluid drug concentrations are

positive result; a test detecting nothing, usually not well correlated with impairment

or a concentration below the cutoff, is or intoxication, but may be consistent with

considered to be a negative result. observed effects.

Laboratory • Testing must be conducted at an HHS, • Laboratories do not need HHS certification.

Certification SAMHSA-certified laboratory. However, clinical laboratories in the United

States and its territories must be registered with

Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments

(CLIA) and comply with all State and local

regulations concerning specimen collection,

clinical laboratory testing, and reporting.

• POCT using kits calibrated and validated

by manufacturers does not require CLIA

certification.

Medical Review • A physician trained as an MRO must • MRO review is not required.

interpret and report results.

7Chapter 2—Terminology and Essential

Concepts in Drug Testing

Drug Screening and Confirmatory Testing

In This Chapter

Traditionally, drug testing usually, but not always, involves

• Drug Screening and a two-step process: an initial drug screen that identifies

Confirmatory Testing potentially or presumptively positive and negative specimens,

• Testing Methods followed by a confirmatory test of any screened positive

assays.

• Test Reliability

• Window of Detection Screening tests (the initial tests) indicate the presence

or absence of a substance or its metabolite, but also can

• Cutoff Concentrations indicate the presence of a cross-reacting, chemically similar

substance. These are qualitative analyses—the drug (or drug

• Cross-Reactivity

metabolite) is either present or absent. The tests generally

• Drug Test Panels do not measure the quantity of the drug or alcohol or its

metabolite present in the specimen (a quantitative analysis).

• Test Matrix Screening tests can be done in a laboratory or onsite

• Point-of-Care Tests (point-of-care test [POCT]) and usually use an immunoassay

technique. Laboratory immunoassay screening tests are

• Adulterants inexpensive, are easily automated, and produce results

• Specimen Validity quickly. Screening POCT immunoassay testing devices are

Tests available for urine and oral fluids (saliva). Most screening

tests use antigen–antibody interactions (using enzymes,

microparticles, or fluorescent compounds as markers) to

compare the specimen with a calibrated quantity of the

substance being tested for (Center for Substance Abuse

Treatment, 2006b).

Confirmatory tests either verify or refute the result of the

screening assay. With recent improvements in confirmation

technology, some laboratories may bypass screening tests

and submit all specimens for analysis by confirmatory

tests. It is the second analytical procedure performed on

a different aliquot, or on part, of the original specimen to

identify and quantify the presence of a specific drug or drug

metabolite (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services

Administration [SAMHSA], 2008). Confirmatory tests use

a more specific, and usually more sensitive, method than do

screening tests and are usually performed in a laboratory.

Confirmatory tests usually:

• Provide quantitative concentrations (e.g., ng/mL) of specific

substances or their metabolites in the specimen.

• Have high specificity and sensitivity.

9Clinical Drug Testing in Primary Care

• Require a trained technician to perform Testing Methods

the test and interpret the results.

Conventional scientific techniques are

• Can identify specific drugs within drug used to test specimens for drugs or drug

classes. metabolites. Most commonly, immunoassay

testing technology is used to perform the

In clinical situations, confirmation is not

initial screening test (Meeker, Mount, &

always necessary. Clinical correlation is

Ross, 2003). Appendix B, Laboratory Initial

appropriate. For example, if the patient

Drug-Testing Methods, briefly describes these

or a family member affirms that drug use

methods.

occurred, a confirmation drug test is not

usually needed. The most common technologies used to

perform the confirmatory test are gas

A POCT, performed where the specimen is

chromatography/mass spectrometry, liquid

collected, is a screening test. A confirmatory

chromatography/mass spectrometry, and

drug test is usually more technically complex

various forms of tandem mass spectrometry.

and provides definitive information about

Information about these methods and other

the quantitative concentrations (e.g., ng/mL)

confirmatory testing methods are in Appendix

of specific drugs or their metabolites in the

C, Laboratory Confirmatory Drug-Testing

specimen tested. However, the term drug

Methods. Other testing methods are used to

screening or testing is misleading in that it

detect adulteration or substitution. Appendix

implies that all drugs will be identified by

D, Laboratory Specimen Validity-Testing

tests, whereas the drug or drug metabolites

Methods, provides a short explanation of

detected by a test depend on the testing

methods for specimen validity testing.

method and the cutoff concentration.

In Federal workplace testing, all positive

initial screening test results must be followed Test Reliability

by a confirmatory test (SAMHSA, 2008). Both POCTs and laboratory tests are

In clinical settings, however, confirmatory evaluated for reliability. Two measures

testing is at the practitioner’s discretion. of test reliability are sensitivity and

Laboratories do not automatically perform specificity, which are statistical measures

confirmatory tests. When a patient’s of the performance of a test. The sensitivity

screening test (either a POCT or laboratory indicates the proportion of positive results

test) yields unexpected results (positive that a testing method or device correctly

when in substance use disorder (SUD) identifies. For drug testing, it is the test’s

treatment, or negative if in pain management ability to reliably detect the presence of a

treatment), the practitioner decides whether drug or metabolite at or above the designated

to request a confirmatory test. In addition, cutoff concentration (the true-positive

a confirmatory test may not be needed; rate). Specificity is the test’s ability to

patients may admit to drug use or not taking exclude substances other than the analyte

scheduled medications when told of the of interest or its ability not to detect the

drug test results, negating the necessity analyte of interest when it is below the cutoff

of a confirmatory test. However, if the concentration (the true-negative rate). It

patient disputes the unexpected findings, a indicates the proportion of negative results

confirmatory test should be done. Chapter 4 that a testing method or device correctly

provides information that can be helpful in identifies.

deciding whether to request a confirmatory

test.

10Chapter 2—Terminology and Essential Concepts in Drug Testing

Tests are designed to detect whether a Window of Detection

specimen is positive or negative for the

substance. Four results are possible: The window of detection, also called the

detection time, is the length of time the

• True positive: The test correctly detects the substances or their metabolites can be

presence of the drug or metabolites. detected in a biological matrix. It part, it

depends on:

• False positive: The test incorrectly detects

the presence of the drug when none is • Chemical properties of the substances for

present. which the test is being performed;

• True negative: The test correctly confirms • Individual metabolism rates and excretion

the absence of the drug or metabolites. routes;

• False negative: The test fails to detect the • Route of administration, frequency of use,

presence of the drug or metabolites. and amount of the substance ingested;

Confirmatory tests must have high • Sensitivity and specificity of the test;

specificity. Generally, screening tests have

relatively low specificity. Screening tests are • Selected cutoff concentration;

manufactured to be as sensitive as possible, • The individual’s health, diet, weight,

while minimizing the possibility of a false- gender, fluid intake, and pharmacogenomic

positive result (Dolan, Rouen, & Kimber, profile; and

2004). Notable exceptions from common

manufacturers of laboratory-based or point- • The biological specimen tested.

of-care immunoassay kits are cannabinoids, All biological matrices may show the presence

cocaine metabolite, oxycodone/oxymorphone, of both parent drugs and their metabolites

methadone, and methadone metabolite (Warner, 2003). Drug metabolites usually

(EDDP, or 2-ethylidine-1,5-dimethyl-3,3 remain in the body longer than do the parent

diphenylpyrrolidine). Other examples may drugs. Blood and oral fluid are better suited

exist. With the exceptions noted previously, for detecting the parent drug; urine is most

they cannot reliably exclude substances other likely to contain the drug’s metabolites.

than the substance of interest (the analyte), Exhibit 2-1 provides a comparison of

and they cannot reliably discriminate among detection periods used for various matrices.

drugs of the same class. For example, a low-

specificity test may reliably detect morphine, Many factors influence the window of

but be unable to determine whether the drug detection for a substance. Factors include,

used was heroin, codeine, or morphine. but are not limited to, the frequency of drug

use (chronic or acute), the amount taken, the

Generally, the cutoff level for initial screening rate at which the substance is metabolized

tests is set to identify 95–98 percent of (including pharmacogenomic abnormalities,

true-negative results, and 100 percent of such as mutations of CYP2D6 and other

true-positive results. Confirmatory test drug-metabolizing enzymes [White & Black,

cutoff concentrations are set to ensure that 2007]), the cutoff concentration of the test,

more than 95 percent of all specimens with the patient’s physical condition and, in many

screened positive results are confirmed as cases, the amount of body fat.

true positives (Reynolds, 2005). However,

confirmation rates are highly dependent upon

the analyte. For cannabinoids and cocaine

metabolite, the confirmatory rate usually

exceeds 99 percent. The clinically important

point is that false positives are rare for

cocaine metabolite or cannabinoids.

11Clinical Drug Testing in Primary Care

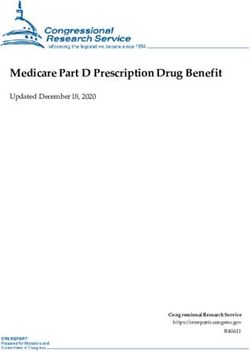

Exhibit 2-1. Window of Detection for Various Matrices

Matrix Time*

Breath

Blood

Oral Fluid

Urine

Sweat†

Hair‡

Meconium

Minutes Hours Days Weeks Months Years

*Very broad estimates that also depend on the substance, the amount and frequency of the substance taken, and other factors

previously listed.

†As long as the patch is worn, usually 7 days.

‡7–10 days after use to the time passed to grow the length of hair, but may be limited to 6 months hair growth. However, most

laboratories analyze the amount of hair equivalent to 3 months of growth.

Sources: Adapted from Cone (1997); Dasgupta (2008).

Cutoff Concentrations Detection thresholds for Federal, employer,

and forensic drug testing panels are set high

The administrative cutoff (or threshold) of a enough to detect concentrations suggesting

drug test is the point of measurement at or drug abuse, but they do not always detect

above which a result is considered positive therapeutic concentrations of medications.

and below which a result is considered For example, the threshold for opiates in

negative. This level is established on the federally mandated workplace urine drug

basis of the reliability and accuracy of screening is 2000 ng/mL. The usual screening

the test and its ability to detect a drug or threshold for opiates in clinical monitoring

metabolite for a reasonable period after drug is much lower, at 300 ng/mL for morphine,

use (see Test Reliability). hydrocodone, and codeine (Christo et al.,

2011) to detect appropriate use of opioid pain

Before the establishment of the Federal medication.

mandatory guidelines, cutoff concentrations

for screening tests were determined by the For laboratory tests, practitioners can

manufacturer of the test or the laboratory. request lower cutoff concentrations than

Because the majority of drug testing is done are commonly used in workplace testing.

for workplace purposes, most laboratories However, in some cases, the error rate

and many POCTs use the Federal mandatory increases as the cutoff concentration

guidelines for workplace testing cutoff decreases.

concentrations. However, Federal cutoff

concentrations are not appropriate for

clinical use. Practitioners need to know the

cutoff concentrations used in the POCTs,

Cross-Reactivity

or by the laboratory testing their patients’ Cross-reactivity occurs when a test cannot

specimens, and should understand which distinguish between the substances being

analyte and at what cutoff the test is tested for and substances that are chemically

designed to detect. similar. This is a very important concept

when interpreting test results.

12Chapter 2—Terminology and Essential Concepts in Drug Testing

Drug class-specific immunoassay tests Practitioners can find some of this

compare the structural similarity of a information in the instructions in the POCT

drug or its metabolites with specially packaging material, or they can talk with

engineered antibodies. The ability to detect laboratory personnel to know exactly what a

the presence of a specific drug varies with laboratory’s tests will and will not detect.

different immunoassay tests, depending

on the cross-reactivity of the drug with an

antibody. For example, a test for opioids may Drug Test Panels

be very sensitive to natural opioids, such

as morphine, but may not cross-react with A drug test panel is a list (or menu) of drugs

synthetic or semisynthetic opioids, such as or drug classes that can be tested for in a

oxycodone. specimen. These can be ordered to identify

drugs of abuse or in pain management.

Substances other than the drug to be detected No single drug panel is suitable for all

may also cross-react with the antibody clinical uses; many testing options exist

and produce a false-positive result. Some that can be adapted to clinical needs. These

over-the-counter (OTC) decongestants (e.g., panels are designed to monitor adherence

pseudoephedrine) register a positive drug to pain treatment plans, to detect use

test result for amphetamine. Phentermine, of nonprescribed pain medications, and

an anorectic agent, commonly yields a to screen for use of illicit drugs. Clinical

false-positive initial amphetamines test. practitioners can order more comprehensive

Dextromethorphan can produce false-positive drug test panels to identify drugs or classes of

results for phencyclidine (PCP) in some assays. drugs that go beyond the federally mandated

Cross-reactivity can be beneficial in clinical drugs for testing. Which drugs are included

testing. As an example, a urine test that in the testing menu vary greatly between

is specific for morphine will detect only and within laboratories; laboratories differ

morphine in a patient’s urine. The morphine- in the drugs or metabolites included in their

specific test will miss opioids, such as comprehensive panel and have more than

hydrocodone and hydromorphone. A urine one type of panel. Therefore, practitioners

drug test or panel that is reactive to a wide should contact their laboratory to determine

variety of opioids would be a better choice for the capabilities and usual practices of the

a clinician when looking for opioid use by a laboratory. It is just as important for a

patient. Conversely, the lack of sensitivity to clinical practitioner to know what a “urine

the common semisynthetic opioid, oxycodone, drug screen” will not detect as it is to know

is detrimental to patient care when a what it will detect. Some laboratories have

clinician is reviewing the results of a “urine a comprehensive pain management panel

drug screen” and sees “opiates negative” for people prescribed opioids for pain (Cone,

when oxycodone abuse is suspected. Thus, Caplan, Black, Robert, & Moser, 2008).

cross-reactivity can be a double-edged sword Panels can be customized for individual

in clinical practice. practices or patients, but using existing

test panels from the laboratory is generally

To avoid false-positive results caused by less expensive for patients and less time-

cross-reactivity, practitioners should be consuming for practitioners than ordering

familiar with the potential for cross-reactivity tests for many individual substances.

and ask patients about prescription and OTC However, these panels vary by laboratory

medication use. and are not standardized. However, it

should be noted that laboratories may default

Drug-testing accuracy continues to improve. to the federally mandated drug tests if a

For example, newer drug tests may correct practitioner does not order a different test

for interactions that have been formerly panel.

associated with false-positive results.

13Clinical Drug Testing in Primary Care

Panels are available in various configurations. has a different window of detection. Urine

The more drugs on a panel, the more is the most widely used test matrix (Watson

expensive the test. Substances typically on et al., 2006). Detailed information about test

these panels include, but are not limited to: matrices is in Chapter 3.

• Amphetamine, methamphetamine.

• Barbiturates (amobarbital, butabarbital, Point-of-Care Tests

butalbital, pentobarbital, phenobarbital, A POCT is conducted where the specimen is

secobarbital). collected, such as in the practitioner’s office.

• Benzodiazepines (alprazolam, POCTs use well-established immunoassay

chlordiazepoxide, clonazepam, clorazepate, technologies for drug detection (Watson et al.,

diazepam, flurazepam, lorazepam, 2006).

oxazepam, temazepam).

POCTs:

• Illicit drugs (cocaine,

methylenedioxyamphetamine [MDA], • Reveal results quickly;

methylenedioxymethamphetamine [MDMA],

methylenedioxyethylamphetamine [MDEA], • Are relatively inexpensive ($5–$20,

marijuana). depending on the POCT, the drugs or drug

metabolites tested for, and the number of

• Opiates/opioids (codeine, dihydrocodeine, tests purchased);

fentanyl, hydrocodone, hydromorphone,

meperedine, methadone, morphine, • Are relatively simple to perform; and

oxycodone, oxymorphone, propoxyphene). • Are usually limited to indicating only

positive or negative results (qualitative,

The practitioner should consult with the

not quantitative).

laboratory when determining the preferred

test panels. When reading the test results, it is important

to know that how quickly the test becomes

The test menu for POCTs differs per positive or the depth of the color do not

the manufacturer and the device. Most indicate quantitative results.

POCTs screen for drugs included in the

federally mandated test panel and other A comparison of POCTs and laboratory tests

drugs or metabolites. Different devices and is in Chapter 3.

manufacturers offer various configurations of

drugs tested for in devices.

Adulterants

Test Matrix An adulterant is a substance patients can

add to a specimen to mask the presence of

A test matrix is the biological specimen used a drug or drug metabolite in the specimen,

for testing for the presence of drugs or drug creating an incorrect result to hide their drug

metabolites. Almost any biological specimen use. Methods to detect adulterants exist, and

can be tested for drugs or metabolites, but most laboratories and some POCTs can detect

the more common matrices include breath common adulterants. No one adulterant

(alcohol), blood (plasma, serum), urine, sweat, (with the exception of strong acids, bases,

oral fluid, hair, and meconium. Depending oxidizers, and reducing agents) can mask

on its biological properties, each matrix the presence of all drugs. The effectiveness

can provide different information about a of an adulterant depends on the amount of

patient’s drug use. For example, the ratio the adulterant and the concentration of the

of parent drug to metabolite in each matrix drug in the specimen. A specimen validity

can be decidedly different, and each matrix

14Chapter 2—Terminology and Essential Concepts in Drug Testing

test can detect many adulterants. Numerous Additional information on validity follows:

adulterants are available, especially for urine

(see Chapter 5). • The pH for normal urine fluctuates

throughout the day, but usually ranges

between approximately 4.5 and 9.0.

Specimen Validity Tests Specimens outside this range are usually

reported by the laboratory as invalid.

Specimen validity tests determine whether a Specimen adulteration should be suspected

urine specimen has been diluted, adulterated, if the pH level is less than 3.0 or greater

or substituted to obtain a negative result. than 11.0.

A specimen validity test can compare urine

specimen characteristics with acceptable • Creatinine is a normal constituent in urine

density and composition ranges for human at concentrations greater than or equal to

urine, detect many adulterants (e.g., 20 mg/dL. If the creatinine is less than 20

oxidizing compounds), or test for a specific mg/dL, the specimen is tested for specific

compound (e.g., nitrite, chromium VI) at gravity.

concentrations indicative of adulteration. • Specific gravity of urine is a measure of

Many laboratories perform creatinine and the concentration of particles in the urine.

pH analyses of all specimens submitted for Only specimens whose creatinine is less

drug testing. An adulteration panel can be than 20 mg/dL need to be reflexively

ordered that determines the characteristics tested for specific gravity, although

of the urine sample (e.g., creatinine level specific gravity may be an integral part of

with reflexive specific gravity when a low a POCT device’s specific validity testing

creatinine is encountered) and checks for panel. Specimens with a low creatinine

the presence of common adulterants. POCT and an abnormal specific gravity may be

devices are available that test for specimen reported as dilute, invalid, or substituted,

validity, as well. depending on the laboratory’s reporting

policies (SAMHSA, 2008).

Although validity testing is not required in

clinical settings, it is sometimes advisable if If the laboratory finds the specimen is

the patient denies drug use. For example, a dilute, it will report the specimen as dilute.

physician treating a patient for an SUD may However, the laboratory will also report the

want to request validity testing if the patient positive or negative test results. Depending

exhibits signs of relapse, but has negative on the degree of dilution, an analyte may still

test results. Point-of-care validity tests are be detected.

available, and some POCT devices also test

for validity at the same time they test for the Appendix D provides more information on

drug analyte. laboratory specimen validity tests.

15Chapter 3—Preparing for Drug Testing

Deciding Which Drugs To Screen and Test For

In This Chapter

When using drug tests to screen a patient for substance use

• Deciding Which Drugs disorders, the practitioner should test for a broad range of

To Screen and Test drugs. Decisions about which substances to screen for can be

For based on:

• Choosing a Matrix

• The patient, including history, physical examination, and

• Selecting the laboratory findings;

Initial Testing

Site: Laboratory or • The substance suspected of being used;

Point-of-Care • The substances used locally (the Substance Abuse and

• Preparing a Specimen Mental Health Services Administration’s [SAMHSA’s]

Collection Site Drug Abuse Warning Network compiles prevalence data

on drug-related emergency department visits and deaths;

information is available at http://www.samhsa.gov/data/

DAWN.aspx);

• The substances commonly abused in the practitioners’

patient population; and

• Substances that may present high risk for additive or

synergistic interactions with prescribed medication (e.g.,

benzodiazepines, alcohol).

Choosing a Matrix

Practitioners can choose among several matrices for drug

and alcohol testing for adults: urine, oral fluid, sweat, blood,

hair, and breath (alcohol only). Neonates can be tested using

meconium. Urine is the most commonly used matrix for drug

testing and has been the most rigorously evaluated (Watson

et al., 2006); it is discussed at length in Chapter 5. Exhibit

3-1 provides a brief comparison of the advantages and

disadvantages of the seven matrices.

17You can also read