CHAPLAINCY AND SPIRITUAL CARE RESPONSE TO COVID-19: AN AUSTRALIAN CASE STUDY - THE MCKELLAR CENTRE

←

→

Page content transcription

If your browser does not render page correctly, please read the page content below

[HSCC 8.2 (2020)] HSCC (print) ISSN 2051-5553 https://doi.org/10.1558/hscc.41243 HSCC (online) ISSN 2051-5561 Chaplaincy and Spiritual Care Response to COVID-19: An Australian Case Study – The McKellar Centre David A. Drummond1 McKellar Centre, Barwon Health, Geelong, Victoria, Australia Email: David.Drummond@barwonhealth.org.au Lindsay B. Carey2 Public Health Palliative Care Unit, La Trobe University, Melbourne, Australia Email: Lindsay.Carey@latrobe.edu.au Abstract: This article will consider a practitioner’s experience of the impact of COVID- 19 on spiritual care within aged care at the McKellar Centre, Barwon Health, Victoria, Australia. Using Sulmasy’s (2002) paradigm, the provision of holistic care will be con- sidered in terms of the physical, psychological, social and spiritual service variations that were necessary in order to continue to provide for the health and wellbeing of the most vulnerable in society – namely those in aged care. The WHO Spiritual Care Intervention codings (WHO, 2017) will be utilized to specifically explore the provision of spiritual care to assist the elderly requesting or needing religious/pastoral intervention. COVID- 19 has radically shaped the environment of the McKellar Centre, however, the needs of elderly aged care residents must continue to be met, and this paper seeks to document how that process has been resolved in light of COVID-19. As pandemics are likely to reoccur, future issues for providing spiritual care from a distance, for the benefit of cli- ents, their families, chaplains and health care organizations, will be noted. It must be acknowledged however, that the pandemic impact within Australia (and indeed much of the Oceania region) has been considerably less to that experienced by other regions of the world. Nevertheless, the preparatory and supportive response of spiritual care undertaken at the McKellar Centre speaks to a local response to an international crisis. Keywords: aged care, chaplaincy, COVID-19, pastoral care, religion, spiritual care 1. Rev. David Drummond, MCounsel., is the Spiritual Care Coordinator at the McKel- lar Centre, Geelong, Victoria, Australia. 2. Dr. Lindsay Carey, MAppSc, PhD, is Senior Lecturer and Senior Research Fellow with the Public Health Palliative Care Unit, La Trobe University, Melbourne, Australia. © Equinox Publishing Ltd 2020, Office 415, The Workstation, 15 Paternoster Row, Sheffield, South Yorkshire S1 2BX.

DAVID DRUMMOND AND LINDSAY CAREY Resumen (Español): Una Respuesta al COVID-19 Desde la Perspectiva de la Capellanía y Cuidado Espiritual: Estudio de un Caso Australiano – Centro “McKellar.” En este artículo se considerará la experiencia de un profesional respecto del impacto del COVID‑19 en el cuidado espiritual en asilos de ancianos, específicamente en el Centro McKellar, de Barwon Health, Victoria, Australia. Utilizando el paradigma de Sulmasy (2002), la provisión de atención integral se considerará en términos de las variantes en servicios físicos, psicológicos, sociales y espirituales, que son necesarias para continuar atendiendo la salud y el bienestar de los más vulnerables en la sociedad: los ancianos. Las codificaciones de la Intervención de Atención Espiritual de la Organización Mundial de la Salud (WHO, 2017) se utilizarán para explorar específicamente la provisión de cuidado espiritual para ayudar a los ancianos que soliciten o necesiten asistencia religiosa/pastoral. El COVID-19 ha cambiado radicalmente el entorno del Centro McKellar. Sin embargo, las necesidades de los residentes mayores deben continuar siendo atendidas. Este estudio busca documentar cómo se resolvieron los cambios necesarios debido al COVID-19. Previendo posibles futuras pandemias, se considerarán puntos claves para brindar atención espiritual a distancia, para el beneficio de los clientes, sus familias, los capellanes y las organizaciones de atención médica. Sin embargo, debe reconocerse que el impacto de la pandemia dentro de Australia (y de hecho, gran parte de la región de Oceanía) ha sido considerablemente menor al experimentado en otras regiones del mundo. No obstante, la respuesta en cuanto a preparación y apoyo del cuidado espiritual realizada en el Centro McKellar refleja tanto una respuesta local como una internacional. Palabras clave: COVID-19, asilos de ancianos, religión, cuidado espiritual, cuidado pastoral, capellanía, la tercera edad Introduction At the time of writing, the COVID-19 pandemic is rapidly increasing and seemingly with no end in sight. Internationally, 5,600,000 cases of the virus have resulted in 350,000 casualties and climbing. China, the originating source, has over 84,000 cases, but is no longer the most impacted nation and seems on the path to recovery, whereas other countries are still seek- ing to flatten the infection curve, with America (over 1,700,000 diagnoses), the United Kingdom (267,000 diagnoses), Spain (236,000 diagnoses) Italy (231,000 diagnoses), and others all seeking strategies to contain the spread of this pandemic. The spread and effects are reminding historians of other “pandemics” such as the bubonic plague, SARS, Ebola, the Avian Flu and the Swine flu. Commentators are recognizing, however, that there will be no “return to normal” in the wake of COVID-19; rather we will need to seek to find “a new normal.” In other words, this particular circumstance will redefine normality for us, and the community is increasingly worried for those who are most vulnerable, particularly the elderly. © Equinox Publishing Ltd 2020

CHAPLAINCY AND SPIRITUAL CARE RESPONSE TO COVID-19 Background As a part of Barwon Health, one of the largest and most comprehensive regional health services in Victoria, Australia, the McKellar Centre offers over 400 residential aged care beds across four facilities and two sites, including high and low level care, aged persons’ mental health, dementia specific and respite care. Such a diverse population, across a breadth of social, cultural, and spir- itual backgrounds of clients, requires spiritual care to be able to engage fluidly between the facilitation of rituals, to emotional support, counselling and education in emotional regulation strategies, through mediation of the complex family issues that arise around placement into care and end-of-life support and the support of staff in times of stress and distress. Case Study – The McKellar Centre COVID-19 arrived in Australia while the first author was on leave. It seemed to “come out of the blue.” It had been hovering, “over there,” overseas, like a storm on the horizon; but before I was scheduled to return to work to support my community, the storm became an immediate reality, here and now. I had been supporting staff and residents remotely even while on leave. However, like many allied health practitioners, the spiritual care team was advised that our role was “essential” but not “immediate.” Therefore, we would be working remotely, which raised an immediate question: “How do you offer a ministry of genuine presence, without being physically present?” In truth, coronavirus arrived in Australia quite soon after the original appearance in Wuhan, China. According to the World Health Organiza- tion (WHO, 2020), cases of “pneumonia of unknown aetiology (unknown cause)” were detected in Wuhan City in December, 2019, and the condition was subsequently named 2019-nCoV (Zhu et al., 2020), then COVID-19, and subsequently SARS-CoV-2 – though it is most commonly described as COVID-19 or the more generic coronavirus. The first case of COVID-19 in Victoria was diagnosed on January 19, 2020, in an international visi- tor to Melbourne who had flown in from Wuhan, China (Walker, 2020). From early February, the Australian Government immediately increased vigilance around COVID-19 in residential aged care facilities leading to the development of a “Residential Aged Care COVID-19 Pandemic Plan” on March 6, 2020. Nearly two months after the first COVID-19 patient diagno- ses, and approximately 75 km from Melbourne, the first case was reported in the Geelong area (proximal to the McKellar centre) being diagnosed around March 6 (Geelong Advertiser) – the same day as the release of the © Equinox Publishing Ltd 2020

DAVID DRUMMOND AND LINDSAY CAREY

government’s “pandemic plan.” Social-isolation for all aged care facilities

commenced from March 19, at which point, visiting spiritual care from

faith communities and our honorary team ceased, followed on March 27 by

a request for spiritual care staff to work remotely and only attend for spe-

cifically triaged needs, determined by facility management. At the time of

writing, no cases of COVID-19 had been diagnosed at the McKellar Centre.

During COVID-19, the McKellar Centre implemented a number of mul-

tidisciplinary measures to assist in the continuity of spiritual care to its

residents whom, as much as possible, have been supported by the incum-

bent chaplains and spiritual carers. These measures can be categorized and

explained using a biopsychosocial–spiritual paradigm (Sulmasy, 2002),

namely (i) physical, (ii) psychological, (iii) social, and (iv) spiritual dynamics

that have been enacted. Each of these are explained in greater detail below,

with the primary focus for the purposes of this article upon the spiritual.

In his aforementioned proposal of the biopsychosocial–spiritual para-

digm, Sulmasy (2002, p. 25) observes that “sickness, rightly understood, is

a disruption of right relationships.” In response to COVID-19’s arrival in

Australia, Barwon Health and the McKellar Centre management, in line

with Government guidelines, initiated an immediate isolation of all aged-

care facilities. Family visits were limited, visitors who did arrive were care-

fully assessed, and coached in protective procedures, and non-essential staff

(including spiritual carers) were excluded. As a preventative measure, isola-

tion has been proven effective. While droplet precautions have been engaged

with residents showing suspect symptoms, to date no cases of COVID-19

infection have been reported within the isolated government-subsidized

facilities in Victoria (Department of Health – Australian Government,

2020). However – in line with Sulmasy’s observation of disrupted relation-

ships and connection with families, friends, and social groups – residents

have been left with feelings of isolation, separation from Easter and other

rituals, and for many there have been feelings of abandonment that need to

be constantly addressed for emotional wellbeing to be maintained.

(i) Physical

The physical part of this situation offers many challenges. The physical

symptoms associated with COVID-19 are synonymous with many other

conditions, and subsequently as we engage winter in Australia, the season

of colds and influenza, alerts are constantly triggered by symptoms that may

or may not be dangerous.

A recent encounter with a resident demonstrates the depth of this

dynamic. His neighbor in the facility had deteriorated and in line with

© Equinox Publishing Ltd 2020CHAPLAINCY AND SPIRITUAL CARE RESPONSE TO COVID-19

existing practices for caring for bronchial issues, staff undertook droplet-

precautions (wearing of personal protective equipment [PPE] when tending

to his care), until unfortunately, because of his physical frailness (not due

to COVID-19), he passed away. For the resident I was visiting, he had wit-

nessed staff congregating near his door to don PPE before going to tend his

neighbor. Out of concern he followed closely the pathway of his neighbor’s

progression, and mourned his neighbor. However, he subsequently noticed

some unrelated illness symptoms within himself, and the same staff who

had appeared in PPE for his neighbor, now entered his room, triggering

fear and anxiety, and compounding the impact of the condition he had

contracted.

In the seminal article that Sulmasy (2002) was expanding, Engel (1977,

p. 132) observed: “[t]he boundaries between health and disease, between

well and sick, are far from clear and never will be clear, for they are diffused

by cultural, social and psychological considerations.” The very necessary

medical and protective interventions themselves triggered insecurity and

hypervigilance impacting negatively the fragile wellbeing of a resident.

Anecdotally, a further expression of the “physical dimension” has been

the requests for physical contact (reaching out a hand, asking for a bless-

ing) that has been experienced in the infrequent times we have been able to

engage with residents face to face. The reduction of physical contact with

family leaves them craving contact, as a form of physical validation and

therapeutic soothing.

(ii) Psychological

The relationship between the mind and the body highlighted in the inter-

action above is frequently strained and distressed in a time of pandemic.

As I write, the television playing in my peripheral vision is airing footage

of mass graves being laid out in New York, the runner at the bottom of the

screen is proclaiming two thousand dead in a single day in the US. Such

images and statistics are overwhelming, particularly when viewed by minds

already anxious with the reality of isolation and the knowledge they are in

the “high-risk” population.

The McKellar population is a complex mix of physical and mental health

conditions, for many of our resident’s dementia, in some form and scale of

impact, is a present reality which influences their ability to engage and cope

with the pandemic conditions. Many find it difficult to comprehend “what”

is happening. However, they are either hyper-aware that families are not

visiting, or more generally that “something is wrong,” resulting in responses

© Equinox Publishing Ltd 2020DAVID DRUMMOND AND LINDSAY CAREY

varied from affect restriction and withdrawal, to anxiety and verbal and

physical outburst.

Interestingly in a review of the Chinese experience of COVID-19, Wang

and Wang (2020, p. 14) observed that “Patients will experience varying

degrees of stigma during the epidemic, and this will cause anxiety, depres-

sion, hostility, and other mental and psychological symptoms requiring

timely intervention to avoid the emergence of mental and psychological

disorders such as long-term post-traumatic stress disorder” or even (one

could add based on recent literature) possibly a “moral injury” given feelings

of abandonment and betrayal (Carey & Hodgson, 2018). Wang and Wang

(2020, p. 14) proposed in response that support strategies of future pandem-

ics should include a mental health early warning system, psychoeducation

and supportive counselling. Such observations are equally evident within

the McKellar environment and planning has already commenced for sup-

port strategies into the future to address potential grief, anxiety, and other

emotional dysregulation conditions.

(iii) Social

The greatest reported impact has been in the social dimension. The loss of

family contact, and suspicion of fellow residents being treated with droplet

precautions has impacted feelings of connectedness and weakened relation-

ships at Easter – a time of year traditionally rich in social connection – and

as a consequence we have witnessed poignant scenes of families seeking to

connect across perimeter fences and through closed windows.

Emmanuel Lartey (2003, p. 140) proposed that “… spirituality refers

to the human capacity for relationship with self, others, world, God and

that which transcends sensory experience.” The social dimension, whether

described as relationship or connection is an essential element to the mean-

ing and identity of the individual, and the loss of that relationship impacts

immediately and substantially on the wellbeing, and even physical health

of the individual.

This is particularly the experience in working with those living with

dementia. Though we often hear the familial complaint “they don’t know

me anymore,” and though many residents with dementia experience diffi-

culties with what might be regarded as “effective social engagement” (coher-

ent speech, memory and recollection, empathic engagement), as Sabat and

Lee (2011, p. 323) observe “the experience of warm, mutually satisfying

social relationships with others becomes ever more significant for people

diagnosed with dementia.” And as Walmsley and McCormack (2018, p. 960)

observe: “[f]or individuals with dementia living in care homes, family visits

© Equinox Publishing Ltd 2020CHAPLAINCY AND SPIRITUAL CARE RESPONSE TO COVID-19

are important opportunities for relational, social, and physical connection,

especially when other opportunities for engagement are lacking.” Anecdo-

tally, I regularly witness residents with dementia seeking to follow, or stand

in close proximity to, staff and fellow residents, perhaps seeking exactly

this social connection. The loss of social connectedness and relationship

through isolation has deeply impacted all residents, regardless of diagnosis,

or stage in condition progression.

(iv) Spiritual

Of the four domains, it might be expected that the spiritual would have

the least impact in management and treatment of residents living under

COVID-19 precautions. However, as Sulmasy (2002, p. 25) observed, “[s]pir-

ituality is about the search for transcendent meaning” and when the world

becomes shrunken to the size of the facility, the transcendent becomes

an even more important filter and interpretive framework. It is also the

domain in which spiritual care practitioners principally, though not exclu-

sively, engage and offer the opportunity to comprehensively minister to the

whole person in tandem with the medical, psychological, and supportive

multidisciplinary team. Following such a holistic approach a number of

helpful strategies have been previously suggested for maintaining health

and well-being by putting faith into action during COVID-19 (Koenig,

2020). The WHO ICD-10/11-AM (WHO, 2017) Spiritual Intervention Cod-

ings (WHO-SPICs) (see Table 1) also offer a frame of reference by which to

Table 1: WHO ICD-10/11-AM spiritual intervention codings

Intervention Descriptor

Assessment Initial and subsequent assessment of wellbeing issues, needs

1824: 96186-00 and resources of a client

Support Spiritual support is the provision of a ministry of presence

1915: 96187-00 and emotional support to individuals or groups

Counselling, Guidance An expression of spiritual care that includes a facilitative in-

& Education depth review of a person’s life journey, personal or familial

1869: 96086-00 counsel, ethical consultation, mental health, life care and

guidance in matters of beliefs, traditions, values, and practices

Ritual All ritual activities both formal and informal.

1915: 96240-00

Allied Health Intervention Any spiritual care intervention undertaken that is not

– Spiritual Care specified or not elsewhere classified

1916: 95550-12

Note: WHO-ICD-10/11-AM (World Health Organization International Classification of

Diseases and Health Related Interventions). Sources: WHO (2017); Carey & Gleeson (2017).

© Equinox Publishing Ltd 2020DAVID DRUMMOND AND LINDSAY CAREY discuss the spiritual care interventions applied during COVID-19 at the McKellar Centre. Assessment The assessment phase usually encompasses the tenure of the resident’s stay in continuous interaction, initially as a screening at or immediately prior to, admission, followed by history-taking to identify active beliefs and practices that might contribute to or otherwise impact care. The ongoing assessment domain is fulfilled in the continuous interactions and conversations with the resident, which must inform the care-plan and the interventions enacted to ensure their wellbeing (Puchalski, 2011, p. 52) Spiritual care at McKellar is seeking to broaden this dimension of assess- ment expanding the cooperation between spiritual care and the broader allied health teams, by incorporating both emotional and affect-informed3 domains into the spiritual assessment strategy in recognition that most spiritual experiences are expressed through emotion and affect, particularly in those with reduced cognitive and language capacities (Drummond and Carey, 2019). The experience of spiritual care in the realm of COVID-19 has confirmed the importance of formally incorporating affect assessment into the domain of spiritual assessment to assist in focusing spiritual interven- tions to the specific needs of each resident, rather than generic in principle applications. Support and Counselling Support and counselling in the current environment have expanded to incorporate digital engagement through Webex, ZOOM, Facetime and 3. Affect has been described as “… a broad class of mental processes, including feeling, emotion, moods, and temperament” (Chaplin, J., 1985, p. 14). It is distinguished from other mental activities such as cognition and volition as being focused on emotional reception and expression. While traditionally spiritual care has focused on the ministration of sacraments and rituals in hope of improving client/consumer’s “affect,” nevertheless, affect assessment has largely remained the domain of non-spiritual care allied health colleagues, particularly mental health. In order to develop evidence-based practices and person-centred care, spir- itual assessment should be informed not only by the instruments available to chaplains/ spiritual carers (prayer, blessing, communion, etc.), but also by the individual consumer’s affect and how we might, through the interventions available to us, assist them to regulate that affect. More recently, in line with the shift from “religious” to “spiritual” descriptors, the chaplaincy/spiritual carer profession has moved, through the incorporation of mindful- ness, to become more “affect informed.” However, with the exception of a small number of instruments, the commonly engaged spiritual assessment instruments make scant investi- gation about the consumer’s affect. © Equinox Publishing Ltd 2020

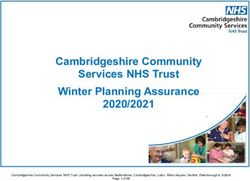

CHAPLAINCY AND SPIRITUAL CARE RESPONSE TO COVID-19 Skype, though admittedly the ability to note and interpret micro-expres- sions and body language is reduced through these mediums, and the lack of familiarity by the residents with such technology can make the experience somewhat stilted and awkward. The priorities of continuing family contact (allowing residents to use the medium to continue contact with family), means that the take-up of the support being offered has been low, with the few opportunities engaged usually being with our more cognitively engaged residents, which have been effective and appreciated. Nevertheless, irrespec- tive of the use of technology, the standard ethical principles of pastoral/ spiritual care have been maintained, namely (i) providing a patient/client- centred and (ii) holistic approach to care, (iii) ensuring accompaniment by actively listening and appropriately responding to clients so as to prevent feelings of alienation and abandonment, (iv) being tolerant and respectful of patient’s particular spirituality, and (v) ensuring discretion and confiden- tiality (Sulmasy, 2012; Carey & Cohen, 2015). Ritual With the COVID-19 pandemic occurring in tandem with the Easter celebra- tions, it was important to facilitate reflective opportunities to compensate for the loss of their usual spiritual and cultural practices around this time. Figure 1: Reflective open space created during COVID-19 © Equinox Publishing Ltd 2020

DAVID DRUMMOND AND LINDSAY CAREY Liaison with our facilities encouraged the creation of a reflective space (see Figure 1) in an open area where residents could sit quietly with sufficient “social distance.”4 Liturgies were developed to be passed to residents, which included a reading, a reflection, and questions for contemplation, and were either passed to residents or were left in the reflective space. In addition, media resources were provided for television shows and local narrow-cast and broadcast recording for communities that residents had belonged to. Feedback from residents in dialogue with nursing and care staff expressed appreciation for the opportunity to continue spiritual and community prac- tices that had been and continued to be a significant part of their life. Discussion The isolation protocols initiated to contain COVID-19 have triggered fur- ther needs within the residents under the care of the McKellar team, and necessitated changes in our methods of engagement with those residents. While nurses, lifestyle, and support staff are still attending physically to the residents who are able to engage physically, those staff are impacted by the added stress of dealing with behaviours, responding to the understand- able demands of families for information and contact, and remaining vigi- lant regarding the deterioration of residents and the emergence of warning symptoms. Spiritual care practitioners, who in “normal” times can assist through their ministry of presence, are now forced to stand far off, observ- ing but not near enough to engage. Therefore, our experience has pushed us to “secondary contacts”: video interaction mediated by computer and tablet-based technology, with a population for whom such media are usually unfamiliar and awkward, and through infrequent physical attendance to engage residents with specific needs to be resolved. Our parent institution has admirably created means for hospital systems to be safely accessed from remote locations, which allows the continual monitoring of information around the conditions of residents, meaning that practitioners can be more proactive in initiating contact with residents experiencing distress, though usually such contact needs to be initiated through on-site staff. 4. Note: Lifestyle staff, employed to consider person-centred activities and occupational health-related compliance, assisted to develop these spaces in line with the needs of their individual communities. The illustration (see Figure 1) is of an overtly religious space for Easter reflection, but this could be equally valuable as a spiritually neutral space. © Equinox Publishing Ltd 2020

CHAPLAINCY AND SPIRITUAL CARE RESPONSE TO COVID-19 Staff One further dimension minimally explored in this paper is the impact of the current situation on staff, and the need for expansion of avenues of staff support. There is a natural reluctance among professional carers to seek support for themselves, whether out of professional identity, fear of the per- ception of weakness, or a desire to conserve scarce resources for others, and thus consequently the take up of person-to-person enterprise assistance programs (EAP) have been low, even given the current pandemic. Certainly, the encouragement of public acclamation has been welcome, but for staff constantly working in areas of heightened vigilance and triggered residents, compounded by the fear of transmission either to their families or from the outside into the facility, the need for avenues of support, both direct and indirect, has increased. Spiritual care has worked with the clinical education team and others to develop education and support strategies around grief/loss and self-care for staff, allowing staff to access tools on the intranet. Additionally, we have consulted with other allied health teams (psychology, social work) to create avenues for managing critical incidents, and continue to offer phone and video personal support to staff distressed by work episodes, and online mindfulness sessions to support the emotional wellbeing of staff. Families The other dimension impacted in the current environment is that of fami- lies. Partners who have tended to their loved ones on a daily basis, visiting for hours at a time, are no longer able to be present. Family members of residents nearing end of life, where in the past we have had rooms full of family sitting vigil, are now limited to one or two at a time. Many family members are understanding of the situation, others frustrated and angry at the loss of contact, compounding the stress on staff. On a triaged, individu- ally assessed basis families are able to attend physically to residents, and can be supported through the same phone and video avenues offered to residents and staff, though such contacts need to be tempered in the face of the overwhelming needs of our more primary charges. Future Issues While this paper has focused on current experiences while the pandemic is still active, thought is being applied to future needs once this situation is resolved. One of the immediate issues being expressed by residents is the “lack of closure” around deaths (both virus related and natural). The © Equinox Publishing Ltd 2020

DAVID DRUMMOND AND LINDSAY CAREY regulations limiting numbers at funerals, the isolation triggered by the vul- nerability of our population to exposure, and the overwhelming numbers of deaths being communicated through our media locally and internationally, suggest that in the wake of this pandemic, public and private rituals will need to be enacted which will allow communal grieving, and the support of those impacted. Plans are already being developed within our facilities for public remembrance services, which will encompass the “usual” deaths experienced in our settings that have been lost amid the pandemic reports, as well as in support of family members our residents have not been able to mourn, or have not yet been informed of because of their situation, and for the impact of the survivors of this situation. Ultimately, the current situation has focused the need for increased atten- tion to ongoing spiritual assessment processes, the strategic development of care plans, and the incorporation of behaviour and affect into our assess- ment processes. Traditionally, assessment processes have focused on the identification of spiritual resources familiar to the consumer, so that these can be engaged in times of decompensation and at end-of-life to satisfy consumer needs. Research is currently being explored that will align spir- itual care assessment practice, focus, and language more closely with other allied health professions, and thus allowing greater collaboration between multidisciplinary teams in the development and execution of care plans that better meet the immediate wellbeing needs of the residents. This is less a priority in acute care settings where spiritual engagement are over a shorter time period. However, in the residential aged care setting, where engage- ments can form over years and decades, the assessment process needs to progress in line with the tenure of the resident and engage a myriad of goals, emotional and physical conditions, and the negotiation of life’s end. The new instrument will be founded in the traditional domains of spir- itual care, but will be informed not only by historic practices and resources, but also by the assessment of current emotional and attachment states, including guilt, shame, anxiety, alienation/abandonment, and grief/loss, which the care plan will then address in accordance with the spiritual, cul- tural, and experiential needs and expectations of the consumer. The new instrument will not be framed in specifically religious or spiritual terminol- ogy, but rather in generic language in order to allow adoption of the instru- ment regardless of the faith, or lack thereof, expressed by the consumer. Spiritual interactions will continue to be founded and grounded in the tril- ogy of screening, history taking and assessment, but through the proposed instrument such assessment tasks will be more refined and targeted (Drum- mond & Carey, 2019). © Equinox Publishing Ltd 2020

CHAPLAINCY AND SPIRITUAL CARE RESPONSE TO COVID-19 Conclusion In the mid-1990s, the first author recalls visiting with a colleague at the bedside of a patient at end of life with AIDS. Both of us gowned and gloved head to foot under the requirements of that hospital, both feeling the isola- tion of the patient. I remember still my reaction when my colleague, heed- less of rules, stripped off a glove to hold the patient’s hand, and I remember wrestling with the “would have,” “could have” thoughts of my own actions. In the current pandemic, because of heart and lung conditions, I am in the high-risk, vulnerable, population and yet still I wrestle not to touch and hold residents wrestling with pain and loss and fear. Our engagement is shaped fundamentally and completely by the pandemic environment, and yet our engagement can continue, and our ability to meet needs and journey with residents through dark times can still be potent, if not as present. One of the scariest dimensions of this current experience is that of asymptomatic and pre-symptomatic transmission – that staff, committed and essential resources to meeting our community’s needs may become part of the threat. That reality generates fear and hypervigilance in our commu- nity, as it should, but fear in any form unresolved or unrecognized places stress on the individual which must be tended and calmed for wellbeing to be cultivated within the individual – spiritual care offers an ideal medium for that wellbeing to be cultivated, and for that reason spiritual care practi- tioners are essential, and must adapt their practice to fit the parameters of the present reality. Both authors are very mindful that this paper is a reflection on an initial response to COVID-19, rather than an analysis of whether a community’s needs have been met, or indeed whether the response was best-practice for the situation. In the long term, such analysis will be critical to ensuring that future situations will be resolved effectively, but such analysis is long into the future, and in the interim, this paper serves to document how spiritual care in residential aged care might meet the consumer in their present real- ity and journey with them as we all seek to navigate the unknown paths COVID-19 creates for us. Acknowledgements Acknowledgement is given to Kate Gillan (Chief Nursing Officer, Barwon Health) and Angela Erwin (Co-director, Aged Care, Barwon Health), for their contribution to this article. Appreciation is also expressed to the management and staff who have continued to support the McKellar Centre vulnerable community in face-to-face contact through an unprecedented © Equinox Publishing Ltd 2020

DAVID DRUMMOND AND LINDSAY CAREY

challenge, and continue to reach past their own anxieties to support those in

greatest need. Appreciation is also expressed to Rev. Dr. Chris Swift (Direc-

tor of Chaplaincy and Spirituality, Methodist Homes, England, UK), Rev.

Meg Burton (Chaplain, St. John’s Hospice, Doncaster, UK) and Associate

Professor Rev. Dr. Bruce Rumbold, OAM (Director of the Public Health

Palliative Care Unit, La Trobe University, Melbourne, Australia) for their

contribution towards this article. Final appreciation is expressed to J.Renae

Carey, BA(Hons), DipLang, for the abstract translation.

Lindsay B. Carey ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1120-7798

David A. Drummond ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3000-2341

References

Carey, L. B., & Cohen, J. (2015). Pastoral and spiritual care. Encyclopaedia of Global Bioethics,

New York: Springer Science, pp. 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-05544-2_326-1

Carey, L. B., & Hodgson, T. J. (2018). Chaplaincy, spiritual care and moral injury: consider-

ations regarding screening and treatment. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 9(619), 1–10. https://

www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyt.2018.00619/full

Carey, L. B., & Gleeson, B. (2017). Spiritual care intervention codings summary table (WHO-

ICD-AM/ACHI/ACS, July 2017). https://doi.org/10.26181/5d563f699a157

Chaplin, J. (1985). Dictionary of Psychology (2nd ed.). New York: Random House.

Department of Health – Australian Government (2020). Coronavirus (COVID-19). Austral-

ian Government Department of Health, Canberra, ACT. https://www.health.gov.au/

sites/default/files/documents/2020/04/coronavirus-covid-19-at-a-glance-coronavirus-

covid-19-at-a-glance-infographic_10.pdf

Drummond, D. & Carey, L. B. (2019). Assessing spiritual wellbeing in residential aged care:

An exploratory review. Journal of Religion and Health, 58(2), 372-390. https://link.

springer.com/article/10.1007/s10943-018-0717-9

Engel, G. (1977). The need for a new medical model: A challenge for biomedicine. Science,

196(4286), 129–196. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.847460

Koenig, H.G. (2020). Maintaining health and well-being by putting faith into action during

the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Religion and Health (Online), 1–10. https://doi.

org/10.1007/s10943-020-01035-2

Lartey, E. (2003). In Living Color: An Intercultural Approach to Pastoral Care and Counseling

(2nd ed.). London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

Puchalski, C. (2011). Formal and informal assessment. Asian Pacific Journal of Cancer Pre-

vention, 11(MECC Supplement), S51–S58.

Sabat, S., & Lee, J. (2011). Relatedness among people diagnosed with dementia: Social cogni-

tion and the possibility of friendship. Dementia, 11(3), 315–327. https://doi.org/10.1177/

1471301211421069

Sulmasy, D.P. (2002). A biopsychosocial–spiritual model for the care of patients at the end

of life. The Gerontologist, 42(Special Issue III), 24–33. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/42.

suppl_3.24

Sulmasy, D. P. (2012). Ethical principles for spiritual care. In M. Cobb, C. Puchalski, & B.

Rumbold (eds.), The Oxford Textbook of Spirituality in Healthcare (pp. 465–470). Oxford:

Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/med/9780199571390.003.0062

© Equinox Publishing Ltd 2020CHAPLAINCY AND SPIRITUAL CARE RESPONSE TO COVID-19 Walker, G. (2020). First novel coronavirus case in Victoria. Victorian Department of Health Media Release, 25 January 2020. https://www2.health.vic.gov.au/about/media-centre/ MediaReleases/first-novel-coronavirus-case-in-victoria Wang, J., & Wang, Z. (2020). Strengths, weaknesses, opportunities and threats (SWOT) analysis of China’s prevention and control strategy for the COVID-19 epidemic. Inter- national Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(7), 1–17. https://doi. org/10.3390/ijerph17072235 Warmsley, B., & McCormack, L. (2018). Moderate dementia: relational social engagement (RSE) during family visits. Aging and Mental Health, 22(8), 960–969. https://doi.org/10 .1080/13607863.2017.1326462 World Health Organization (2017). Tabular list of interventions. The World Health Organi- sation International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, Tenth Revision, Australian Modification (ICD-10-AM), Australian Classification of Health Interventions (ACHI) and Australian Coding Standards (ACS) WHO ICD- 10-AM/ACHI/ACS. Australian Consortium for Classification Development (ACCD: University of Sydney). Darlinghurst, NSW: Independent Hospital Pricing Authority Chapter 19 — Spiritual: (i) assessment, p. 262; (ii) counselling, guidance and education, p. 272; (iii) support, p. 291; (iv) ritual, p. 291; (v) allied health intervention – Spiritual Care – generalised intervention (listing only), p. 291. World Health Organization (2020). Pneumonia of unknown cause – China: Disease out- break news, 5 January 2020. Retrieved 27 April 2020 from https://www.who.int/csr/ don/05-january-2020-pneumonia-of-unkown-cause-china/en/ Zhu, N., Zhang, D., Wang, W., Li, X., Yang, B., Song, J., Zhao, X., Huang, B., Shi, W., Lu, R., Niu, P., Zhan, F., Ma, X., Wang, D., Xu, W., Wu, G., Gao, G., and Tan, W., for the China Novel Coronavirus Investigating and Research Team (2020). A novel coronavirus from patients with pneumonia in China, 2019. The New England Journal of Medicine. 382(8), 727–733. https://doi.org/10.1056/nejmoa2001017 © Equinox Publishing Ltd 2020

You can also read