C-76 Non-Resident Voting Rights - Andrew Griffith and Robert Vineberg Summary - House of Commons

←

→

Page content transcription

If your browser does not render page correctly, please read the page content below

C-76 Non-Resident Voting Rights

Andrew Griffith and Robert Vineberg

Summary

This brief focuses on the issue of non-resident voting and proposes an amendment to s. 151 that

sets a minimum three year residency requirement for expatriate voting rights, consistent with

Article 1 of the Charter of Rights and Freedoms. This brief makes four recommendations:

1. To ensure that administrative simplicity and efficiency should guide any non-resident

voting rules, any changes should build on the current Elections Canada process;

2. That the committee should consider an amendment to s.151 — the addition of “for a

minimum of three years and be a holder of a valid Canadian passport”:

S. 222 Register of Electors

The Chief Electoral Officer shall maintain a register of electors in which is entered

the surname, given names, gender, date of birth, civic address, mailing address and

electoral district of each elector who has filed an application for registration and

special ballot in order to vote under this Division and who, at any time before

making the application, resided in Canada for a minimum of three years and

is a holder of a valid Canadian passport.

3. To allow only a valid Canadian passport to be used for proof of Canadian citizenship.

This is the recognizable document used by Canadians in all travel and legal activities

abroad. Those who choose not to renew or re-apply for a Canadian passport demonstrate

a weaker connection to Canada.

4. To direct Elections Canada to conduct an evaluation following the next election, on the

degree to which the changes increased the number of non-resident voters and the impact,

if any, it had in individual ridings and to recommend the creation of additional overseas

ridings as appropriate based on the number of non-residents who do vote in future

elections.

"1Introduction

This brief focuses on one element of Bill C-76, An Act to amend the Canada Elections Act and other Acts

and to make certain consequential amendments, namely the provisions for electors resident outside

Canada (clauses 150-155) that replace the current five-year rule with unlimited voting rights for

any citizen “who, at any time before making the application, resided in Canada.” (s.151)

The government has chosen to address this issue prior to the Supreme Court of Canada’s current

consideration of the challenge regarding the current limit of five years abroad for voting rights.

This brief is written from an overall citizenship policy perspective, and the message such an

unrestricted approach sends regarding the meaningfulness of Canadian citizenship.

To begin with, Canada has a generally inclusive approach to citizenship that encourages most

immigrants to become citizens, although the numbers applying and consequent naturalization

rate recently have been declining recently due to restrictions that are about to be repealed and

inordinately high application fees that we believe ought to be rolled back (see Mr. Griffith’s brief

to the Senate’s Social Affairs, Science and Technology Committee on Bill C-6 (changes to the

Citizenship Act)).

A major right that citizenship provides, as distinct from residency, is the political right of voting

and being able to present oneself as a candidate for office. A secondary right is the preference it

provides for joining the public service. Similarly, a major responsibility of citizenship, as distinct

from residency, is the duty to serve on a jury if called upon to do so.

But most rights and responsibilities apply to both citizens and permanent residents alike: the

Charter of Rights and Freedoms, obeying Canadian laws, paying taxes, not abusing or defrauding

social services and the like.

These rights and responsibilities are largely residence-based, not citizenship-based. Apart from

consular services, Canadian non-residents are not entitled to access Canadian medicare, EI or

welfare or other services but, if qualified, non-residents can receive payments under the Canada

Pension Plan and Old Age Security. Canadian non-residents are not subject to the Canadian

judicial system unless their crime or dispute happens in Canada or impacts on residents of

Canada. Canadian non-residents with Canadian income are, however, required to file income

taxes.

Voting rights are clearly citizenship-based rather than residence based, as confirmed by Supreme

Court jurisprudence and s. 3 of the Charter. However, extending indefinite voting rights to all

Canadians living abroad would allow them to pronounce on the main issues of elections and

political debates, irrespective of their ongoing connection to Canada.

The question becomes to what extent the “reasonable limitations” of s. 1 of the Charter can and

ought to be applied to limit voting rights to Canadians living abroad, most of whom neither use

nor contribute to government programs. Extending non-resident voting rights indefinitely means

that those who do not live in Canada will be voting on many issues that do not impact upon them

on a day-to-day basis. In contrast, Canadians living in Canada are directly impacted by all

government decisions and programs.

"2The government has partially addressed this issue by proposing to limit voting rights to those who

have at any time resided in Canada: i.e., Canadian expatriates by descent who have never lived in

Canada would not be able to vote.

The next section of this brief sets out what we know and do not know about the number of non-

residents, the main arguments for and against the Government’s proposed approach, and

proposes variants that may provide greater flexibility for Canadian non-resident voting rights

while ensuring a meaningful connection to Canada.

Number of non-residents (expatriates)

Before stating the arguments for and against the bill’s proposed approach, a more accurate

estimate of the number of Canadian non-residents is in order. The government, to date, has not

elaborated on the number of non-residents it deems affected by this change beyond the general

“over one million” Canadians living abroad.

This is a more reasonable estimate that that used by some recent advocates. Many have relied on

the Asia Pacific Foundation (APF) estimate 2.8 million non-residents in its study, Canadians Abroad:

Canada’s Global Asset.1 The APF did not control for age or citizenship. When age and citizenship

are factored in (using 2006 Census data), the number of voting age Canadian citizen non-

residents is just under 2 million (of the 2.8 million, 77 percent are aged 18 or over, 42 percent are

immigrants, of which 78.1 percent are Canadian citizens).

The vast majority of non-residents live in the United States (over one million), Hong Kong

(300,000), UK (73,000), Taiwan (50,000), Lebanon (45,000) and UAE (45,000).2

More important, there is a dearth of data on non-residents’ degree of connection to Canada,

and what exists is largely based on anecdote rather than hard data. Some non-residents remain

highly connected to Canada through family ties and visits or work and other professional

activities, including the plaintiffs in the Supreme Court of Canada challenge. Others have

minimal to no ongoing connection, having left Canada at an early age or having returned to their

country of origin once having become citizens (the so called “citizens of convenience”).

The government data that we do have, however, provides an indication of the degree of

connection.

Consular data for 2007 to 2015 show that approximately 20,000 non-residents annually accessed

services for people who had been abroad for five years or more (about 84 percent of all consular

cases). The number of adult passports issued to Canadians abroad was about 131,000 in 2015,

with the overwhelming majority (126,000) being issued to those adults living abroad for five years

or more. There were approximately 725,000 Canadian passport holders living abroad (adults and

children, short and long-term non-residents), about 630,000 of whom are adult non-residents

living abroad for five years or more.

Looking at non-resident Canadians tax filing data, 112,000 non-resident returns, less than one

percent of total tax returns. Compared to the estimated number of adult non-resident Canadians

(two million), 6 percent of non-residents filed tax returns in 2015, the most recent year complete

data are available. While this figure may understate the proportion of non-resident Canadians

filing taxes, as some may use Canadian addresses, it suggests that the vast majority of non-

"3residents do not pay Canadian income tax. There does not appear to be reliable data on non-

residents’ property taxes paid in Canada.

CHART 1

Data on voting among those who have been abroad less than five years indicate the number of

non-residents who register and vote is very low. Chart 1 shows the number of nonresident

electors, valid votes and percentage of voter turnout for the last six elections.

The number of Canadian non-residents that fall into the five-years or less category is small.

Consular data indicate only three percent of all consular cases are for medium-term non-

residents (one to five years), meaning around 60,000 non-residents in this category, with about

one-quarter of that number registering to vote. Passport data suggest a comparably small

number, just over 25,000 passport holders abroad fall into the less than five years group.

The data we have, however imperfect, suggest that of the 2 million Canadian citizens living

abroad aged 18 or over, the number who have ongoing active connections with Canada is likely

quite low. Even advocates of non-resident voting rights, after citing the APF number of 2.8

million non-residents abroad, go on to quote the figure of “over one million” who have active

connections, as did the government, but without explaining the basis for that number.

Our sense, drawing from passport data, suggests an even smaller number.

"4International comparisons of non-resident voting

As in the case with Canada, the number of non-residents of other countries are estimates, not

exact numbers. Moreover, while non-resident voter registration and voting data is accurate, some

countries allow non-resident voting without advance registration (i.e., Australia) and do not

separate out non-resident from domestic postal ballots. There is no data on the number of non-

residents who may travel back to their country of origin to vote.

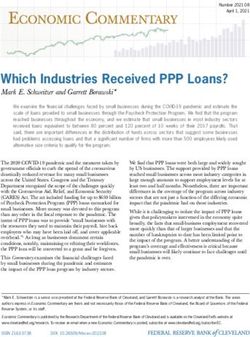

TABLE 1 - INTERNATIONAL COMPARISONS MOST RECENT NATIONAL ELECTIONS

Resident Data Non-Resident (NR) Data

Total Voting Turn- NR Voting Voters % %

Pop (TVP) Out Pop(EVP) Registered TVP EVP

Canada 25,939,742 68.3% 2,000,000 15,603 0.06% 0.8%

USA 230,593,103 57.5% 2,600,000 389,105 0.17% 15.0%

UK 46,354,197 66.1% 3,615,000 105,845 0.23% 2.9%

Australia 16,589,009 91% 688,000 71,406 0.43% 10.4%

New Zealand 3,496,850 78% 711,000 47,875 1.37% 6.7%

France 46,028,542 79.5% 1,742,713 1,067,457 2.32% 61.3%

With these caveats, the low number of Canadian registered non-resident voters (0.06 percent of

the total voting population - TVP) or 0.78 percent of the estimated number of non-residents of

voting age is not unique to Canada and its five-year limit as shown in Table 1. Countries with

more expansive non-resident voting rights such as the US, UK, Australia and New Zealand have

comparatively low registration rates compared to the total voting population: 0.17, 0.23, 0.43 and

1.37 percent respectively. France, with unlimited non-resident voting rights has a higher share of

non-resident registrations compared to the TVP: 2.32 percent.

This tends to confirm the view that the non-resident vote will not affect the overall outcome of

elections, although it may impact on some ridings. The one exception may have been with

respect to US presidential elections given the electoral college (e.g., Florida in 2000).

The picture changes with respect to the percentage of registered non-residents compared to the

estimated total number of non-residents. Over 60 percent of French non-residents are registered,

reflecting overseas constituencies. About 15 percent of American, ten percent of Australian and

seven percent of New Zealand non-residents are registered (for Australia we have used the voting

numbers given that registration is not required for Australian non-residents). The UK has the

lowest share of non-residents registering: only three percent.

It is not possible to predict the degree to which the change proposed in C-76 would result in a

change of non-resident registration rates. However, a working assumption would be a range of

ten to fifteen percent (Australia and USA respectively) meaning between 200,000 to 300,000

"5Canadian non-residents registering — not significant in terms of total voters (between 0.8 and

1.2 percent) but nevertheless over ten times the current number of registered non-resident voters.

The advocates behind the Charter challenge tend to agree that it would be a relatively small

number compared to either the total voting population or the number of voting age non-

residents.

Current system and how it would change

Non-resident voters must register their name in the International Register of Electors. Current

eligibility rules require that non-resident electors must:

• be Canadian citizens;

• be at least 18 years old on election day;

• have lived in Canada at some point in their life;

• intend to move back to Canada to reside; and,

• have lived outside Canada for less than five consecutive years or be exempt from the five-

year limit based on where they or someone they live with is employed.

Supporting evidence that must be provided includes the following options:

• pages 2 and 3 of a Canadian passport; or,

• a Canadian citizenship certificate or card; or,

• a birth or baptismal certificate, showing that the person was born in Canada.

There is considerable flexibility in which Canadian address non-resident electors can choose

provided it is an actual address, not a mailbox, although this is considered to be their last

Canadian address.

There is an on-line application to facilitate registration.

The government’s proposed approach in C-76 has the advantage of administrative simplicity as

it would essentially entail repealing the intent to return and reside requirement along with the

five-year rule. Presumably, the same evidentiary requirements of citizenship would continue.

Arguments in favour of unlimited non-resident voting rights

Arguments in favour of expanding the non-resident voting rights are based on the Charter’s

protection of voting rights without qualification. The main substantive arguments, by the

plaintiffs in the Supreme Court challenge, by academics (such as Semra Sevi, Peter Russell,

Alison Loat and John McArthur), and by former Foreign Affairs (now Global Affairs) director

general of Consular Affairs, Gar Pardy, can be summarized as follows:

• Canadians living abroad contribute to Canada and the world, and many retain an active

connection with Canada, whether it is business, social, cultural, political, or academic.

These Canadians’ global connections should be valued as an asset;

• Patriotism and civic engagement are not tied to location;

"6• The internet and online communities make it easier for Canadians to remain in touch with

Canada and Canadian issues;

• As Judge Laskin said in his dissenting statement in the July 2015 Ontario Court of Appeal

ruling, Canadians living abroad pay “Canadian income tax on their Canadian income,

and property tax on any real property they may own in Canada,” and are subject to

Canadian laws and foreign policy decisions;

• As Russell and Sevi note, the non-resident vote will not “completely change the tide of an

election”, which international comparisons tend to bear out;

• The five-years-or-less limitation is more restrictive than our traditional comparator

countries:

• United States: no limitation, but non-residents are required to file US tax returns;

• United Kingdom: current limitation of fifteen years absence is in the process of

being removed (Votes for Life Bill);

• Australia: limitation of six years, and non-residents must file a declaration of their

intent to return at some point;

• New Zealand: limitation of three years, renewable upon visits, minimum of having

lived one year in New Zealand.

• The government, in justifying its approach, cited France, which has no limitation, and

where even foreign-born children of non-residents are able to vote in elections even if they

have never lived in France. However, they vote in one of 11 overseas constituencies, not in

domestic constituencies; 3

• The Canadian five-year limitation ignores the increasing globalization and population

mobility, and it sends the wrong signal to young Canadians; and,

• As Jean-Pierre Kingsley, former chief electoral officer, said when he advocated eliminating

the five-year limit: “The right to vote is a fundamental right of citizenship that is protected

by the Charter and does not depend on place of residence.” A parliamentary committee

reviewed his report in 2006 and endorsed his position.

Argument against unlimited non-resident voting rights

The principal arguments against unlimited non-resident voting rights are, in our view, the

following:

• The “social contract” argument, used by the Ontario Court of Appeal to uphold the

policy, states that voting “would allow them [non-residents] to participate in making laws

that affect Canadian residents on a daily basis, but have little to no practical consequence

for their own daily lives. This would erode the social contract and undermine the

legitimacy of the laws.” Examples of policies and programs that are considered part of the

social contract include economic and social policies and programs, at the federal level;

health care and education, at the provincial level; and policing and transit at the municipal

level;

"7• While some non-residents may pay Canadian taxes and may own property in Canada, the

data suggest over 90 percent do not, as they pay tax where they work and live outside of

Canada;

• Interest in voting among non-residents appears to be low and international comparisons

indicate suggest that removal of the five-year limit is unlikely to dramatically increase non-

resident turn-out. (This, of course, can also be used as an argument in favour of

expanding voting rights, as the impact would be small and the benefit to those who want to

vote would be large.);

• Apart from consular and passport services, most Canadian government economic and

social programs are tied to residency;

• In general, the longer the time spent abroad, the looser the bond with Canada, as family,

work and local connections become more meaningful. Over time, day-to-day living —

work, education, raising a family, consuming media — are predominately important for

non-residents, whether in the United States, Hong Kong or the Mid-East. Again, the

experience of the US and UK with more generous limits suggest this is a common

experience; and,

• While the current small numbers of non-resident voters is small and does not affect

individual ridings, allowing over a million non-residents to vote could affect outcomes in

some ridings where the numbers of non-residents is high (e.g., Hong Kong-based non-

residents voting in Vancouver-area ridings).

Some of the advocates of non-resident voting, for example, Gar Pardy, argue for no limits, with

Loat and McArthur implying this. Sevi and Russell imply limits, but ones that are more in line

with those of other countries, without indicating their preference.

Overall assessment

In choosing to respond to pressures to relax the current five-year restriction on non-resident

voting, the Government has chosen the one of the least restrictive approaches possible: only

requiring a citizen to have lived in Canada at one time, without setting any minimum time of

residence in Canada. This has the advantage of administrative simplicity, only requiring minor

changes to current Elections Canada requirements and being relatively easy to verify.

The government has justified this approach in part by invoking the “a Canadian is a Canadian is

a Canadian” argument without acknowledging that this argument was originally made in limited

context of revocation of citizenship in cases of treason or terrorism, and the consequent need to

treat Canadian-born and naturalized Canadians equally before the law.

While others with greater knowledge of the Charter arguments for and against expanded non-

resident voting will no doubt also be submitting briefs, in our view, the “reasonable limitations”

provision of s. 1 of the Charter provides scope to limit s. 3 regarding the right to vote as the

Ontario Court of Appeal ruled. We believe that the situation of prisoners as ruled in the Sauvé

case is distinct from those of non-residents, given that prisoners reside in Canada and, while

different from other residents, have day-to-day experience with government policies and services,

and thus a greater stake in political outcomes.

"8The government’s residency requirement (“at any time”) addresses the issues posed by expatriate

Canadians of descent who have never lived in Canada and thus who do not have the right to

vote. However, the lack of any minimal time requirement means that a Canadian born in

Canada but who left as a baby and never having lived in Canada would be entitled to vote.

While the provision to extend voting rights indefinitely may be the most administratively simple

system, it is more generous than most of our normal comparator countries; could be seen to

devalue Canadian citizenship; and, may undermine the connection between exercising one’s

votes and living with the consequences of the resulting government decisions.

Most Canadians living in Canada have to live with the consequences of their political choices.

Non-resident Canadians, whether interested in Canadian politics or not, have less at stake in

terms of the bread and butter issues of the economy, such as jobs, healthcare and the like.

Moreover, in proposing this expansion of voting rights, the government has not taken the logical

next step of considering publicly whether such an expansion should be accompanied by the

creation of overseas constituencies in the form of separate ridings for non-residents, as a number

of countries have done, including France, Italy and Portugal among OECD countries.4

While there are issues with respect to overseas constituencies, given that it deepens the meaning

of dual citizenship and perceptions of allegiance and loyalty, such constituencies could address

the concern of voters residing in Canada their wishes could be overrules by the non-resident vote

or that their local MP might be overly responsive to non-resident voters in ridings where relatively

more non-residents have lived. Furthermore, these would reflect non-resident voter interest in

Canadian issues being more broad and general than the bread-and-butter issues of those living in

Canadian ridings.

The “comparability” with other nations argument is more reasonable and convincing, and opens

the discussion as to which option — a citizenship taxation linkage, as in the United States;

extending the limitation to 15 years, as currently in the United Kingdom; or, renewable voting

rights, as in Australia or New Zealand — makes the most sense from a policy and

implementation perspective. The French model cited by the government appears to reflect the jus

sanguinis (bloodline) approach to citizenship as opposed to the jus soli (birthright) approach to

citizenship of immigration-based countries like Canada.

Recommendations

In our view, the government’s proposed approach may diminish the value of Canadian

citizenship in one of its most fundamental manifestation: political participation. It makes no

effort to establish any meaningful criteria related to non-residents’ connection to Canada beyond

having lived in Canada at one time, no matter how short.

While the five-year absence rule may have been arbitrary and too short, it was meaningful in that

it acknowledged that physical presence in Canada, at one time or another, mattered. We require

a minimum period of three years residence for immigrants to become Canadian, and if a

“Canadian is a Canadian is a Canadian” then it would make sense to have a comparable

minimum eligibility period for non-residents.

Connections to Canada generally weaken the longer one is absent from Canada. While one can

follow Canadian news and debates online, citizenship is more of a contact sport than virtual

"9reality. The day-to-day reality of living and working in Canada, being subject to Canadian laws

and using government services, is central to our democratic system.

The experience of other jurisdictions, with no limits or more generous limits, suggests that this is

common to most non-residents and it is likely that Canadian non-residents would behave

similarly for the most part.

While any time limit will be criticized as arbitrary and unfair by those most interested in voting

(likely the ones who do maintain a meaningful connection), the alternative of no limit could be

seen to devalue those electors in Canada who have to live from day to day with government

decisions and choices.

While one of us (Griffith) prefers the current status quo limit of five-years outside Canada (one

parliament) and one of us prefers broader non-resident voting rights (Vineberg), we recognize the

government’s commitment to expand non-resident voting rights. With this in mind, we make the

following recommendations:

1. To ensure that administrative simplicity and efficiency should guide any non-resident

voting rules, any changes should build on the current Elections Canada process;

2. That the committee should consider an amendment to s.151 — the addition of “for a

minimum of three years and be a holder of a valid Canadian passport”:

222 Register of Electors

The Chief Electoral Officer shall maintain a register of electors in which is entered

the surname, given names, gender, date of birth, civic address, mailing address and

electoral district of each elector who has filed an application for registration and

special ballot in order to vote under this Division and who, at any time before

making the application, resided in Canada for a minimum of three years and

be a holder of a valid Canadian passport.

3. To allow only a valid Canadian passport to be used for proof of Canadian citizenship.

This is the recognizable document used by Canadians in all travel and legal activities

abroad. Those who choose not to renew or re-apply for a Canadian passport demonstrate

a weaker connection to Canada.

4. To direct Elections Canada to conduct an evaluation following the next election, on the

degree to which the changes increased the number of non-resident voters and the impact,

if any, it had in individual ridings and to recommend the creation of additional overseas

ridings as appropriate based on the number of non-residents who do vote in future

elections.

"10Annex: Sources and methodology

Note: A number of different terms are used to capture non-resident citizens and voters. These

include expatriates, overseas citizens, and citizens living abroad. We have chosen non-resident as

the most neutral term.

Canada: The number of expatriates is derived from the 2011 Asia Pacific Foundation’s

Canadians Abroad: Canada’s Global Asset estimate of 2.8 million non-resident Canadians. Of the 2.8

million, 77 percent are aged 18 or over, 42 percent are immigrants, of which 78.1 percent are

Canadian citizens, meaning 1.96 million voting age Canadian citizens living abroad.

Voting data (2015) was provided by Elections Canada.

USA: The number of total non-residents (5.7 million) and voting age non-residents (2.6 million)

are taken from the Federal Voting Assistance Program (the State Department overall numbers are

higher: 9 million). Data from the US Election Assistance Commission was used with respect to

the number of ballots send to overseas non-military voters: 389,105 or 44.4 percent of the total

number 876,362 issued. The number of completed ballots for overseas civilians was 278,212, or

71.5 percent of ballots issued.

Other sources consulted included an article and related report by Jay Saxton and Patrick

Anhedric, Expatriate Americans are the most important voting bloc you’ve never heard of.

While not used, another source of data is the United States Election Project, which had a much

higher estimate of overseas eligible voters: 4.7 million.

We chose to go with the official government sources (FVAP, US EAC) and 2012 presidential data

as the full 2016 election data was not available at time of writing.

UK: The number of non-residents used was from a BBC article, Election 2015: Getting out the

expat vote, and the Royal Statistical Society’s How many British immigrants are there in other

countries? 18 November 2014 which estimates between 4.5 and 5.5 million. The voting

population is 72.3 percent of the total population (46.4 million of 64.1 million) and using the

same percentage for an estimated non-resident population of 5 million gives a voting age non-

resident population of 3.6 million.

The House of Commons Library Briefing Paper Overseas Voters Number 5923, 11 October

2016 was used to provide the number of registered overseas voters: 26,918 in 2014, a number

which quadrupled to 105,845 in 2015, the figure used. The report also cites a 2006 study by the

Institute for Public Policy Research that indicates 5.6 million non-residents of which 4.4 million

are of voting age: 78.6 percent (the BBC covered the report extensively in Brits Abroad).

Australia: The most recent official figure of Australians living abroad is 760,000, dating from

2004 (Submission No 646 to the Senate Inquiry into Australian Expatriates, 2004, p. 5). Other

public sources indicate one million, which is the figure used, and then adjusted to reflect the same

percentage of voting age as in Australia: 68.8 percent, resulting in an estimated non-resident

voting population of 690,000.

"11Voting data (2016), both registration (enrolment) and votes cast was provided directly by the

Australian Electoral Commission (email 7 March 2017). As noted, registration is not mandatory

for Australian overseas voters, with the number of voters being almost three times as much as

those registered (71,406 compared to 28,400). We have used the number of votes as a more

accurate indication of interest.

New Zealand: The estimated number of non-resident New Zealanders is one million,

according Statistics New Zealand. Using the same methodology as for Australia, we apply the

percentage of eligible voters compared to the total population (71.1 percent) which gives an

estimated number of voting age non-residents of 711,000.

Voting data (2014) was provided directly by the New Zealand Electoral Commission along with

its annual report (email 23 February 2017). 47,875 electors were registered and 40,132 voted.

France: The number of registered non-residents is 1.6 million with 74 percent or 1.18 million

being of voting age according to the French Foreign Ministry. The number of unregistered non-

residents is higher; a 2014 article in The Independent French say au revoir to France: Over two

million French people now live abroad, and most are crossing the channel and heading to

London used the number of 2.5 million, the number most likely to be comparable to other

estimates used. The non-resident voting population has been calculated using the same

methodology as for Australia and New Zealand: 69.7 percent of non-residents being of voting

age as in France, or 1.7 million.

An analysis by Susan Collard, The Expatriate Vote in the French Presidential and Legislative

Elections of 2012: A Case of Unintended Consequences states the number of registered voters to

be 1,078,570 with 454,910 votes cast, the numbers that have been used in this comparative

analysis.

Information of the foreign constituencies can be found on Wikipedia: Constituencies for French

residents overseas.

"12Andrew Griffith is the author of “Because it’s 2015…” Implementing Diversity and

Inclusion, Multiculturalism in Canada: Evidence and Anecdote and Policy

Arrogance or Innocent Bias: Resetting Citizenship and Multiculturalism and is a

regular media commentator and blogger (Multiculturalism Meanderings). He is the

former Director General for Citizenship and Multiculturalism, Immigration,

Refugees and Citizenship Canada, has worked for a variety of government

departments in Canada and abroad and is a fellow at the Canadian Global Affairs

Institute and the Environics Institute.

Robert Vineberg is the author of Responding to Immigrants’ Settlement Needs The Canadian

Experience (Springer, 2012) as well as a number of scholarly articles on the history of

immigration policy. He is the former Director General of the Prairies and Northern

Territories, Citizenship and Immigration Canada (now Immigration, Refugees and

Citizenship Canada) and has worked for a number of federal departments in

Canada and abroad.

"131 Asia Pacific Foundation, Canadians Abroad: Canada’s Global Asset, Vancouver: 2011.

2 Data on the number of US and UK Canadian non-residents come from the OECD, which only counts as non-

residents those born in Canada, thus underestimating the total given the number of naturalized Canadians living

abroad. Hong Kong estimates are from Zhang and DeGolyer, 2011. The estimates for Taiwan, Lebanon and UAE

are from the Global Affairs Canada website.

3 Wikipedia, Constituencies for French residents overseas, consulted January 2, 2017.

4 Wikipedia, Overseas Constituencies, consulted 18 December 2016.

"14You can also read