An Analysis of the United States and United Kingdom Smallpox Epidemics (1901-5) - The Special Relationship that Tested Public Health Strategies ...

←

→

Page content transcription

If your browser does not render page correctly, please read the page content below

Med. Hist. (2020), vol. 64(1), pp. 1–31. c The Author 2019. Published by Cambridge University Press 2019 This

is an Open Access article, distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution licence

(http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted re-use, distribution, and reproduction in

any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

doi:10.1017/mdh.2019.74

An Analysis of the United States and United Kingdom

Smallpox Epidemics (1901–5) – The Special

Relationship that Tested Public Health Strategies for

Disease Control

BERNARD BRABIN 1,2,3 *

1

Clinical Division, Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine, Pembroke Place,

Liverpool, L3 5QA, UK

2

Institute of Infection and Global Health, University of Liverpool, UK

3

Global Child Health Group, Academic Medical Centre, University of Amsterdam,

The Netherlands

Abstract: At the end of the nineteenth century, the northern port of

Liverpool had become the second largest in the United Kingdom. Fast

transatlantic steamers to Boston and other American ports exploited

this route, increasing the risk of maritime disease epidemics. The

1901–3 epidemic in Liverpool was the last serious smallpox outbreak in

Liverpool and was probably seeded from these maritime contacts, which

introduced a milder form of the disease that was more difficult to trace

because of its long incubation period and occurrence of undiagnosed

cases. The characteristics of these epidemics in Boston and Liverpool

are described and compared with outbreaks in New York, Glasgow and

London between 1900 and 1903. Public health control strategies, notably

medical inspection, quarantine and vaccination, differed between the

two countries and in both settings were inconsistently applied, often for

commercial reasons or due to public unpopularity. As a result, smaller

smallpox epidemics spread out from Liverpool until 1905. This paper

analyses factors that contributed to this last serious epidemic using the

historical epidemiological data available at that time. Though imperfect,

these early public health strategies paved the way for better prevention

of imported maritime diseases.

Keywords: Smallpox, Maritime, Epidemic, Public health, Boston,

Liverpool

* Email address for correspondence: b.j.brabin@liverpool.ac.uk

The author wishes to acknowledge Dr Loretta Brabin and the three anonymous reviewers for critical appraisal

of the manuscript; Mr David McGuirk for assistance with medical illustration; the University of Liverpool Inter-

Library Loan Team; and staff at the Wirral Archives, Liverpool and Birkenhead Central Reference Libraries, and

Wellcome Trust Reference Library, London.

Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. IP address: 46.4.80.155, on 21 Dec 2020 at 20:26:58, subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at

https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms. https://doi.org/10.1017/mdh.2019.742 Bernard Brabin

Introduction

A constellation of factors contributed to the pattern of smallpox outbreaks in the United

States and United Kingdom at the onset of the twentieth century. This dreadful disease had

occurred in sequential epidemics throughout the nineteenth century in British cities,1 and

was largely imported from Europe.2 In contrast in the United States, with the exception

of mild smallpox in the southern states and a few severe cases in New York City, the

disease had, by 1897, entirely disappeared from the country.3 This changed in late 1896,

following an outbreak of a very mild type of smallpox which originated in the southern

states and spread over four years to northeastern cities and ports. Historical epidemiology

suggests importation of smallpox from these ports to the United Kingdom, and particularly

to Liverpool from Boston in 1901. The barrier of the Atlantic Ocean was now bridged by

fast transatlantic steamers, shortening crossing times to fewer than six days,4 heightening

commercial shipping interests while allowing rapid dissemination from infected sailors.

The Liverpool Dock System between 1890 and 1906 was radically reconstructed, allowing

intake of a greater number of larger ships from America.5 Liverpool expanded to become

the second largest port in the United Kingdom at the turn of the century.

This paper describes the factors that contributed to the pattern of national smallpox

outbreaks in the United States and United Kingdom, and specifically in the cities of New

York, Boston and Liverpool, between 1901 and 1903. Reconstructing these historical

epidemics using imperfect sources is challenging, and methodological limitations are

considered. The primary aim is to describe public health approaches to control smallpox

during epidemics in major transit ports for Atlantic shipping, and factors which influenced

these efforts. Experience with different responses helped develop a more evidence-based

approach to disease control and to anticipate the general public’s response to such

measures. A knowledge base for disease control was growing, given experience with other

maritime imported epidemic diseases, such as cholera and plague, but smallpox differed

due to the availability of an effective preventive vaccine, the efficacy of which had not

been fully assessed. In analysing these data, a secondary aim is to examine the evidence

that smallpox cases occurring in Liverpool in 1901 and 1902 may have originated from

American imported cases. Peak smallpox incidence in the United States spanned the period

1901 and 1902 and a high infection risk was channelled via ships travelling from Boston

to Liverpool, where the outbreak peaked in April 1903. Outbreaks across northern and

central England were temporally related to the Liverpool epidemic.

The response to the epidemics was influenced by new epidemiological approaches

and public health practices in both countries, although public health recommendations

differed. In the United States, national and state vaccination strategies varied, as did

exemption regulations for children and adults. In both countries, local factors influenced

commercial interests, variable clinical disease patterns, delayed diagnosis and quarantine

practices. An improved understanding of smallpox disease epidemiology slowly emerged

1 Charles Creighton, A History of Epidemics in Britain, Volume Two 1666–1893 First edition 1894 (London:

Frank Kass and Co. Ltd., 1965), 582–601 and 604–19.

2 Donald R. Hopkins, Princes and Peasants, Smallpox in History (Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press,

1983), 87–96.

3 Charles Value Chapin, ‘Variation in Type of Infectious Disease as Shown by the History of Smallpox in the

United States 1895–1912’, Journal of Infectious Diseases, 13 (1913), 171–96.

4 P.J. Hugill, World Trade since 1431 (Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1993), 128.

5 William Farrer and J. Brownbill (eds), A History of the County of Lancaster, Volume 4 (London, 1911), 41–3.

British History Online http://www.british-history.ac.uk/vch/lancs.

Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. IP address: 46.4.80.155, on 21 Dec 2020 at 20:26:58, subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at

https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms. https://doi.org/10.1017/mdh.2019.74United States and United Kingdom Smallpox Epidemics (1901–5) 3

and contributed to eventual control and elimination through broadened international

efforts.

Methodological Approaches to Reconstructing Historical Epidemiological

Evidence

Extracting and interpreting late nineteenth-century information from historical medical

records on smallpox in order to quantify risk factors, a standard method in modern disease

epidemiology, is subject to several pitfalls. Instead of meticulous tracing and recording of

known cases and their contacts, the basic assumption at that time attributed the social and

domestic habits of the poor to be the principal factors spreading smallpox.6 Emphasis on

environmental and aggregate models of health and disease suggested that microorganisms

causing a specific disease were subordinate to the person’s total environment.7 It is true

that environmental conditions are important, but by the late nineteenth century it was also

realised that epidemics were caused by a specific agent. Although the organism responsible

for smallpox had not been isolated, it caused a recognised disease, which evoked

introduction of tighter measures to prevent its importation. This included inspecting ships,

monitoring smallpox outbreaks at home and abroad, and some level of contact tracing.8

Europe-wide pandemics from 1870 to 1875 had led to improved vaccination strategies,

with legal provisions for enforcement. These developments, the basis of modern preventive

epidemiology, occurred despite inadequate understanding of the causal agent, its modes of

transmission, or the relative impact of behavioural changes and social determinants.9

Despite such progress, the present reconstruction of historical outbreaks and

examination of their risk factors is affected by several criteria which are difficult to

quantify. These included: variable definitions of reported events; misdiagnoses; lack of

detailed household transmission data; spatial heterogeneities; inadequate information on

vaccine effectiveness – partly because of lack of reliable estimation methods; difficulties

in early recognition of smallpox cases and confusion with chicken pox or measles;

notification delayed until the afflicted person had been suffering for many days and the

absence of explicit statistical analyses.10,11 Since the length of the incubation period

can only be known for individuals exposed early, late reporting compromised quarantine

regulations which specified a period of fourteen to sixteen days. In practice, it was based

on clinical experience and limited epidemiological data. Similarly, vaccine coverage of

the general population, or subgroups, was critical in order to reach a target capable of

interrupting an epidemic. In the modern era, estimates of critical vaccine coverage are

6 Anne Hardy, The Epidemic Streets. Infectious Disease and the Rise of Preventive Medicine 1856–1900 (Oxford:

Clarendon Press, 1993), 134 and 145.

7 Charles E. Rosenberg, Explaining Epidemics and Other Studies in the History of Medicine (Cambridge:

Cambridge University Press, 1992), 299–301.

8 Alexander Mercer, Infections, Chronic Disease, and the Epidemiological Transition: A New Perspective

(Rochester, NY: University of Rochester Press, 2014), 69.

9 S. Del Valle, H. Hethcote, J.M. Hyman and C. Castillo-Chavez, ‘Effects of Behavioural Changes in a Smallpox

Attack Model’, Mathematical Biosciences, 195, 2 (2005), 228–51.

10 Hiroshi Nishiura, Stefan O. Brockmann and Martin Eichner, ‘Extracting Key Information from Historical Data

to Quantify the Transmission Dynamics of Smallpox’, Theoretical Biology and Medical Modelling, 5 (2008), 20

doi:10.1186/1742-4682-5-20.

11 Karen Wallach, The Antivaccine Heresy: Jacobson v. Massachusetts and the Troubled History of Compulsory

Vaccination in the United States (Rochester Studies in Medical History), (Rochester, NY: University of Rochester

Press/Boydell and Brewer, 2015), 70–73, 253. Provides an extensive list of references covering the period 1900

to 1902 on difficulties of smallpox diagnosis in the United States.

Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. IP address: 46.4.80.155, on 21 Dec 2020 at 20:26:58, subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at

https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms. https://doi.org/10.1017/mdh.2019.744 Bernard Brabin

obtained by estimating the ’reproduction number’, which is based on the average number

of secondary cases which arise from a single index case in a susceptible population in

the absence of interventions. During the early twentieth century, lack of reliable statistical

methods precluded measurement of vaccine effectiveness and, as a consequence, use of

smallpox vaccine remained controversial. In this paper, vaccine efficacy is calculated from

the data available, both in the United States and the United Kingdom. In 1903, Boston

Health Department physician Dr Frank Morse pointed out that accurate smallpox records

had been kept only since 1888, and were reported in the Annual Reports of the City Health

Department Surgeon, as well as the Annual Reports of the Surgeon General of the Public

Health, and Marine-Hospital Service of the United States. Nevertheless, this information

provided no data on how many people were vaccinated or re-vaccinated out of the total

population.12 In the United Kingdom, case numbers and locations were listed in the

Annual Reports of City Medical Officers of Health, and the Metropolitan Asylums Board,

and these provided crude estimates of vaccinated and allegedly vaccinated individuals,

although criteria for identifying vaccine scars were unclear. Part of the analysis in this

paper uses information based on these reports for the years 1901 to 1905. Monthly case

notifications are available in both the United States and United Kingdom, but seasonal

analysis of case fatality is limited, as available reports provide mostly annual data on

deaths. The availability of these data also enables evaluation of the hypothesis that the

Liverpool outbreaks originated in the United States, where disease control measures

differed and may have been less efficient.

Maritime Relationships between Britain and the United States

Early Twentieth-Century Maritime Quarantine Regulations at British and United States

Seaports

In the late nineteenth century, quarantine stations and regulations for the sanitary

inspection of ships were present at many British seaports, and general sanitary

arrangements were satisfactory in two-thirds of the sixty port sanitary districts.13 Similar

arrangements were present on the Atlantic seaboard of the United States.14 Several

diseases were cause for concern, including cholera, plague, yellow fever and smallpox.15

Sanitary inspection of all vessels entering British or United States ports was the main

strategy available. The UK Public Health (Shipping) Act of 1885 extended the ordinary

powers of local authorities granted in the 1872 Public Health Act to the Port Sanitary

Authorities with respect to infectious disease.16 These initiatives allowed efficient

intervention when vessels with infected crew or passengers entered ports.17 To this end,

smallpox figures for countries from which other ships originated were included in reports

12 Ibid., 16.

13 Anne Hardy, ‘Smallpox in London: Factors in the Decline of the Disease in the Nineteenth Century’, Medical

History, 27 (1983), 128.

14 Howard Markel, ‘A Gate to the City: The Baltimore Quarantine Station, 1918–28’, Public Health Reports,

110, 2 (1995), 218–9.

15 D.S. Barnes, ‘Cargo,”Infection,” and the Logic of Quarantine in the Nineteenth Century’, Bulletin of the

History of Medicine, 88 (2014), 75–101.

16 Public Health (Shipping) Act (1885), 48 & 49, and Public Health Act (1872), 75 & 76 Vict. c. 79, sec. 3, 20.

17 J.C. Burne, ‘The Long Reach Hospital Ships and Miss Willis’, Proceedings of the Royal Society of Medicine,

66 (1973), 1017–21.

Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. IP address: 46.4.80.155, on 21 Dec 2020 at 20:26:58, subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at

https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms. https://doi.org/10.1017/mdh.2019.74United States and United Kingdom Smallpox Epidemics (1901–5) 5

in both countries,18,19 and could be used to enhance surveillance.

There was some collaboration between the two countries. The United States Assistant

Surgeon, Dr Carroll Fox (b.1874), stayed in the Liverpool United States Consulate for

three months in 1902 to review infection control policy and practice and the numbers

of smallpox and typhus cases.20 He reported on six Liverpool municipal hospitals as

well as on containment, refuse disposal and disinfection procedures, noting that steam

disinfectors used in Liverpool were newer than those used by the Public Health Service at

the quarantine station in Port Townsend, Washington. This exchange signalled some of the

first international efforts to harmonise infection control practice across major sea routes for

maritime transport. Yet, in September 1902, as Dr Fox completed his mission, eleven ships

with infected seamen from Boston had already arrived in Liverpool, and Dr Fox failed to

mention the Boston epidemic in his report.

In the last decade of the nineteenth century, the twin systems of medical inspection

and quarantine were in use, but with greater emphasis on medical inspection and case

isolation. The risk posed by foreigners had become more evident to the general public

in the United States as migration sensitised opinions, and foreigners became a focus for

quarantine policies.21, 22 In the United Kingdom, the Merchant Shipping Act of 1894

required medical inspection of all outward bound steerage passengers and crew, when

services of a medical practitioner could be obtained, on board ship or preferably before

embarkation.23 In the Port of London, Gravesend, the Medical Officer for the Board of

Trade commonly examined all persons as they proceeded along the gangway and refused

them permission to proceed, if considered ill.24 This screening had low sensitivity, but

should have identified obviously sick travellers with facial rashes, which might be a sign of

active infection. As an alternative to inspection, the argument for quarantine of ships was

contentious. A Lancet editorial commented in 1880 that it only survived because it was

plausible, seductive and fitted the unreasonable demands of certain Continental powers,

and that ’it was derogatory to England that she should submit to these hideously farcical

detrimental proceedings’.25 Quarantine avoided the trouble of disinfecting and removing

the sick, but was costly for trading sea ports. Moreover, unless cholera, plague or yellow

fever was existent on board a vessel, there was no legal authority for detaining her on

sanitary grounds. Some had advocated the inclusion of smallpox in the cholera, plague

and yellow fever order, but a smallpox reservoir in the United Kingdom was assumed so

its inclusion was considered inadvisable, as it would deter international trade.

18 Annual Report of the Surgeon General of the Public Health and Marine-Hospital Service of the United States,

Fiscal Year 1902 (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1903), 303–3.

19 Annual Report of the Surgeon General of the Public Health and Marine-Hospital Service of the United States,

Fiscal Year 1904 (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1905), 100.

20 Annual Report of the Surgeon General of the Public Health and Marine-Hospital Service of the United States,

Fiscal Year 1903 (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1904), 192–3. He later won recognition for the

identification of a quirk in the flea population of San Francisco, California, and helped prevent a wider outbreak

of plague which had been infecting the city population since 1900. Public Health Reports, 25 September 1908,

quoted in David K. Randall, Black Death at the Golden Gate: The race to save America from the bubonic plague

(New York: W.W. Norton and Company, 2019), 210–11.

21 Barnes, op. cit. (note 15).

22 Alan M. Kraut, Silent Travelers: Germs, Genes, and the ’Immigrant Menace’ (Baltimore, MA: Johns Hopkins

University Press, 1995), 50–77.

23 Port of London Sanitary Committee. Annual Report of the Medical Officer of Health to 31 December 1902.

May 1903, 23–5.

24 Ibid., Appendix H, 77–91.

25 The Lancet, editorial, 1 (1880), 687–9.

Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. IP address: 46.4.80.155, on 21 Dec 2020 at 20:26:58, subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at

https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms. https://doi.org/10.1017/mdh.2019.746 Bernard Brabin

Quarantine Stations

In Britain, quarantine stations, including some more isolated offshore establishments,

had existed in the early nineteenth century. This remained the only effective measure

until later in the century when contact tracing and surveillance were introduced. Port

Sanitary Authorities established hospital ships in a number of locations around Britain to

isolate suspected smallpox cases. In 1884, the Metropolitan Asylums Board moored three

converted ships in the Thames to serve as a floating hospital,26 primarily for indigenous

cases arising during the 1884–5 London smallpox epidemic.27 By 1899, the Infectious

Diseases Notification Act required compulsory notification of infections, by which time

smallpox was the focus of attention.28 In Liverpool in 1874, the Local Government Board,

under the Public Health Act, permanently constituted the Liverpool Council with powers

to inspect vessels on arrival and to appoint a quarantine station in the River Mersey where

vessels could anchor. A quarantine station already existed at Hoyle Lake, an offshore area

enclosed by sandbanks on the outer Mersey Estuary, which provided accommodation

for infected patients, particularly cholera cases.29 As the estuary began silting up and

Liverpool port expanded, a land-based Port Sanitary isolation hospital was built in 1875 at

New Ferry, isolated from the public, and with ship access via a long wooden jetty.30

Procedures were in place for ship fumigation, cleaning and painting of vessels,

disinfection of clothing, and vaccination of passengers and seamen, although often seamen

refused vaccination.31,32 This task was immense, given the number of ships passing

through the Port of Liverpool. More than 1200 cases of tropical diseases were admitted

to the Port Sanitary Hospital in the period 1875–1963, including cholera, leprosy and

smallpox. Some infectious disease patients were still treated as ordinary patients in

other Liverpool hospitals, including smallpox cases, which were later transferred to New

Ferry.33 As early as 1891, New Ferry was declared unnecessary. Instead, long-haul ships

proceeded directly to the Pier Head entrance of each Liverpool dock to answer questions

on quarantine, a concession much appreciated by ship owners.34 In 1896, quarantine

was discontinued and officially replaced by medical inspection,35 although in practice

quarantine remained, but at the discretion of the Local Government Board rather than

as a national policy.36 New Ferry simply acted as an isolation hospital for eighty-eight

26 Burne, op. cit. (note 17).

27 London Metropolitan Asylums Board Annual Report 1900 (London: M. Corquadale and Co. Ltd., 1901).

28 Infectious Diseases Notification Act (1899), 62 & 63 Vict. c. 8.

29 Thomas Herbert Bickerton, Medical History of Liverpool from the Earliest Days to the Year 1920 (London:

John Murray, 1936), 188.

30 Port Sanitary Hospital, New Ferry, City of Liverpool Smallpox Register, Wirral Archives, Cheshire Lines

Building Centre, Birkenhead, Wirral.

31 Hardy, op. cit. (note 13), 122–3, 129.

32 William Hanna, Report on Marine Hygiene: Being Suggestions for Improvements in the Sanitary

Arrangements and Appliances on Shipboard. Liverpool Port Sanitary Authority (Liverpool: C. Tinling and Co.

Ltd., 1917).

33 Liverpool and Emigration in the Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries. National Museums Liverpool, Maritime

Archives and Library, Information Sheet 64.

34 John Booker, Maritime Quarantine. The British Expansion, 1650–1900 (Hampshire, UK: Ashgate Publishing

Ltd, 2007), 547.

35 The Public Health Act 1896 (Statute 59 and 60, c19) made provisions with respect to epidemic, endemic

and infectious diseases and repealed the 1825 Quarantine Act (Statute 6 Geo iv, c78), and sections in other acts

in which quarantine was mentioned. The Act united for the first time the sanitary arrangements of the United

Kingdom.

36 Booker, op. cit. (note 34), 549–50.

Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. IP address: 46.4.80.155, on 21 Dec 2020 at 20:26:58, subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at

https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms. https://doi.org/10.1017/mdh.2019.74United States and United Kingdom Smallpox Epidemics (1901–5) 7

Figure 1: Liverpool Port Sanitary Hospital Commemorative plaque.

years and was officially razed to the ground in 1963. A commemorative plaque records

its historic role and location and is the last physical reminder of a Port Sanitary hospital

in the United Kingdom (Figure 1). Even today, quarantine is exerted only in exceptional

circumstances.

In the United States, maritime quarantine was initially a state service but was transferred

to a national Public Health Service between the 1880s and the 1920s. The Marine Hospital,

dedicated to the care of ill and disabled seamen in the United States Merchant Marines, the

US Coast Guard and other federal beneficiaries, eventually evolved into the Public Health

Service Commissioned Corps.37 Quarantine stations were established,38 and a prescribed

protocol followed, based on the vessel’s sanitary history and presence of infected or

deceased crew or passengers. Disease detection led to active disinfection and fumigation of

ships and isolation of passengers. When a case of smallpox was diagnosed on board, crew

and passengers were expected to spend fourteen days in quarantine, although breaches

of recommended policies were often made, especially for travellers in first and second

class.39

Factors Leading up to the Boston 1901–2 Smallpox Epidemic in the United

States

Smallpox, when diagnosed, was reported and case fatalities were recorded across the

country. Dr Charles Value Chapin (1856–1941), an American pioneer in public health

research and practice, and Health Superintendent (1884–1932) for Providence, Rhode

Island, compiled a detailed outline of smallpox in the United States between 1895 and

1912.40 By 1897, with the exception of mild smallpox in the South and a few severe cases

in New York City, the disease had disappeared from the country. During 1896, cases of

mild smallpox in Florida began to spread and within a period of about four years cases

37 United States Public Health and Marine-Hospital Service Annual Report, 1905, 221.

38 Markel, op. cit. (note 14).

39 Michael Willrich, Pox. An American History (New York: The Penguin Press, 2011), 219.

40 Chapin, op. cit. (note 3), 186.

Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. IP address: 46.4.80.155, on 21 Dec 2020 at 20:26:58, subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at

https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms. https://doi.org/10.1017/mdh.2019.748 Bernard Brabin

were detected all over the country.41 The rate of dispersion was exponential because the

infection was mild, which meant that patients remained active, and contagious, in their

communities and cases were under-reported.42 By 1900 this wave of infection had reached

northeastern cities, and by 1901 had carried smallpox to every state and territory in the

Union. There had been an epidemic in New York City in late 1899, preceding that in

Boston in 1901.43,44 The main culprit was the milder strain (Variola minor), with had a

death rate of 2 to 6% among unvaccinated individuals, which was considerably lower than

with the Variola Major strain.45 Variola major nonetheless remained present in several

American cities, particularly in the northeast.

Disease notification was incomplete in some cities and rural areas, and some states

omitted returns.46 Incidence for individual states returning notifications can be estimated

using 1900 National Population Census data and the 1901 Annual Report of state smallpox

notifications of the Surgeon General of the Public Health and Marine-Hospital Service. 47,

48

Figure 2 shows these estimates by state between 28 June 1901 and 27 July 1902 per

100 000 population. By 1901, as the epidemic spread to northern states, incidence rapidly

declined in southern states, ranging from less than one per 105 population in Texas, to

more than 300 cases per 105 population in North Dakota, Minnesota and Wisconsin.

Annual smallpox notifications peaked nationally in 1901 at 56 857 cases (Figure 2). In

Massachusetts, where the 1901 Boston epidemic occurred, annual incidence for that year

was sixty per 105 population. In New York City, between 1901 and 1902, 3480 smallpox

cases were reported, with 720 deaths (incidence approximately 100 cases per 100 000

population).49

The Boston epidemic commenced in May 1901 in a large factory.50 Cases were initially

mild but by May 1901 severe cases began to appear. Their source was not known. The

Health Department thought a letter received by a family from infected relatives living

through the New York epidemic was the cause.51 In the outbreak, twelve cases within

forty-eight hours were admitted to hospital, and despite control measures, cases increased

to thirty in September, forty-nine in October, 195 in November, and 201 in December

1901.52 By the end of October 1902, new cases of smallpox had appeared in nearly

every section of the city with the epidemic continuing into 1903. In total, there were

1596 cases (period incidence 284 per 100 000 population) with 270 deaths (17%).53

41 Hopkins, op. cit. (note 2), 288.

42 Gareth Williams, Angel of Death. The Story of Smallpox (Hampshire, UK: Palgrave Macmillan, 2010), 331–2.

43 Chapin, op. cit. (note 3), 186.

44 Willrich, op. cit. (note 39), 41–74, 167.

45 Thirty-First Annual Report of the Health Department of the City of Boston for the Year 1902 (Boston: City of

Boston Printing Department, 1903), 36.

46 Ibid., 172.

47 United States National Census 1900. 12th Census Population. United States Federal Census Records,

www.Censusrecords.com.

48 Annual Report of the Surgeon General of the Public Health and Marine-Hospital Service of the United States,

Fiscal Year 1901 (Washington DC: Government Printing Office, 1902), 319–44, 579–82.

49 John Christie McVail, Half a Century of Smallpox and Vaccination (Milroy Lectures), (Edinburgh: Edinburgh,

E. & S. Livingstone, 1919), 10.

50 Thirtieth Annual Report of the Health Department of the City of Boston for the Year 1901 (Boston: City of

Boston Printing Department, 1902), 43.

51 Chapin, op. cit. (note 3), 186.

52 Thirtieth Boston Annual Health Department Report, op. cit. (note 50), 44.

53 Michael Albert, Kristen Ostheimer and Joel Breman, ‘The Last Smallpox Epidemic in Boston and the

Vaccination Controversy, 1901–1903’, New England Journal of Medicine, 344, 5 (2001), 375–8.

Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. IP address: 46.4.80.155, on 21 Dec 2020 at 20:26:58, subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at

https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms. https://doi.org/10.1017/mdh.2019.74United States and United Kingdom Smallpox Epidemics (1901–5) 9

Figure 2: United States smallpox incidence per 100 000 population per annum, 28 June 1901–27 July 1902.

Sources: National Population Census data of 1900 [note 47]; Annual Report of State Smallpox Notifications of

the Surgeon General of the Public Health and Marine-Hospital Service for 1901 [note 48].

A smaller concurrent smallpox epidemic occurred in the adjoining city of Cambridge,

Boston’s close neighbour across the Charles River.54 The nationally prominent senior

public health officer in Boston, and Health Department Chairman, Dr Samuel Holmes

Durgin (1839–1931), initially played down the epidemic, referring to it as only ’a flurry

of cases’ and a minor storm that would pass.55 Durgin advised that schools should remain

open and insisted that immediate vaccination rather than quarantine was the most effective

control strategy. Many leading physicians in Boston preferred vaccination to sanitation and

quarantine, and were somewhat indifferent to public anxiety over contagion.56 Durgin was

blamed for the continued spread of smallpox, not least because he had allowed the Health

Department physicians who treated smallpox patients to mingle with and expose the public

without taking precautions.57 The cost of quarantine weighed heavily on officials and the

controversy received front-page press coverage.58

The difference in severity of cases between epidemics warrants further examination.

Characteristics of this epidemic can be gleaned from the clinical records of 243 patients

consecutively admitted to the Southampton Street smallpox hospital in Boston.59 Some

hospital cases were caused by the Variola major form of smallpox, but these were not

necessarily representative, as many attacks were mild.60 Smallpox has an incubation period

of approximately seven to seventeen days, clinical onset leading to headache and backache,

fever and malaise during a three-day pre-eruptive period before appearance of a skin rash.

54 Wallach, op. cit. (note 11), chapter three, ’The 1901–2 smallpox epidemic in Boston and Cambridge’, 75–8.

55 Ibid., 59.

56 Ibid., 68–9.

57 Ibid., 152–3.

58 ‘Three Strong Letters against Quarantine, The Board of Health’s Opinion. Dr Brough’s Opinion’, Cambridge

Chronicle, 19 July (1896).

59 Michael R. Albert, Kristen G. Ostheimer, David J. Liewehr, Seth M. Steinberg and Joel G. Breman, ‘Smallpox

Manifestations during the Boston Epidemic of 1901–3’, Annals of Internal Medicine, 137, 12 (2002), 993–1000.

60 Wallach, op. cit. (note 11), 69.

Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. IP address: 46.4.80.155, on 21 Dec 2020 at 20:26:58, subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at

https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms. https://doi.org/10.1017/mdh.2019.7410 Bernard Brabin

Hospital cases presented with varying severity, but 47% were the milder form of the

disease, and most occurred in previously vaccinated persons. Full recovery took weeks,

with most deaths occurring as a result of unrecognised cases of smallpox in the city and

suburban districts going about from place to place, with many unvaccinated people being

exposed to infection.61 In the initial febrile phase (two to four days), individuals would

be infective, but infected seafarers, or their contacts, may not have developed symptoms

until nearly three weeks later. Individuals incubating the disease could readily depart on

transatlantic ships and act as disease vectors.62

The Boston epidemic coincided with a smaller smallpox epidemic (after accounting

for the difference in population size) in London, commencing in June 1901 and lasting

until January 1903, with 9484 notified cases.63 There is no evidence that the London

and Boston outbreaks were connected, despite their similar timing of onset. The daily

surveillance returns to the Metropolitan Health Board for the 1901–3 London epidemic

indicated upwards of twenty different centres of infection. The origin of the disease for the

first two patients could not be traced and, so far as was known, no cases arose from contact

with them. Two foci at the end of June identified a Parisian male who infected four people,

including a laundry worker who infected nine other contacts.64 In August, several other

cases, whose contact source could be traced, seemed unconnected. Preceding both these

epidemics was an outbreak in Glasgow, which began in April 1900 and lasted until July

1901 (1786 notified cases), with a recrudescent period between January and May 1902

(469 notified cases).65 The Glasgow epidemic terminated prior to the onset of the Boston

epidemic and the two are unlikely to have been directly related. A small epidemic occurred

in Dublin in 1903 with fewer than 250 cases and fewer than forty deaths,66 which resulted

from indigenous transmission with an index case from Glasgow. Vessels from Boston did

not sail via Dublin (see Figure 4 in next section).

Transatlantic Sailings Transmitting Smallpox from the Eastern United States

to Liverpool

In the nineteenth century, thousands of emigrants from the British Isles left from Liverpool

Port. Packet lines sailed regularly from 1818, and in 1822 smallpox was transmitted

from Liverpool to Baltimore on board the ship Pallas.67 Demand for North American

timber and cotton to meet British industrial expansion led to well-established transatlantic

links. British manufactured products provided a useful return cargo. Steamships started

to replace sail after the 1860s and the average voyage time was reduced to as few as

six days.68 The city of Liverpool was largely dependent upon the sea for its commercial

61 Thirty-first Boston Annual Health Department Report, op. cit. (note 45), 36.

62 Albert, op. cit. (note 59), 375.

63 Metropolitan Asylums Board Annual Report 1901, Sixteenth Report of the Statistical Committee (London:

McCorquadale & Co. Ltd., 1902).

64 Ibid., 108.

65 Archibald Kerr Chalmers, ‘Smallpox, 1900–2’, Corporation of Glasgow Report (West Nile Street, Glasgow:

Robert Anderson, Printer, 1902), 8–10.

66 Detailed Annual Reports of the Registrar-General (Ireland), for 1902 (39th), 1903 (40th), 1904 (41st)

containing numbers and causes of deaths registered in Ireland for that year (Dublin: His Majesty’s Stationery

Office, Cahill and Co., 1903, 1904, 1905).

67 Cyril William Dixon, Smallpox (London: Churchill Press, 1962), 198.

68 ‘The American Mails. Performances Outward and Homeward, Cunarders at the Front’, The Liverpool Post, 11

April (1900).

Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. IP address: 46.4.80.155, on 21 Dec 2020 at 20:26:58, subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at

https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms. https://doi.org/10.1017/mdh.2019.74United States and United Kingdom Smallpox Epidemics (1901–5) 11

prosperity. Several steamship lines at the turn of the century were competing for

transatlantic passengers to Boston from Liverpool, and American cattle ships departing

from Boston traded regularly with the City.69 Schedules of ships arriving in Liverpool

from Boston for different steamship companies resulted in multiple arrivals each week,

and round trip transits took less than a month. In 1902, tonnage entering and leaving the

River Mersey amounted to the colossal total of 29 000 000 tons, with 214 000 emigrants.70

Prior to the 1901–3 epidemic, smallpox was imported on eight known occasions to

Liverpool in 1900, the most important being that of the SS New England, which arrived

with nineteen cases on board. This ship left Boston on 1 February, arriving in Liverpool

on 30 March. On leaving Boston with 525 passengers and 268 crew, including fifty-five

clergymen and many elderly people, it travelled to the Mediterranean.71 On 11 March,

prior to arriving in Constantinople, a male death occurred after presenting with petechial

skin haemorrhages, which were attributed to liver atrophy. The body was buried at sea.

By 21 March, twelve other people were sick, including eight crew, two of whom were

employed in the laundry, and two who had been assigned to seal the dead man’s body

in a casket. By 23 March, other passengers were sick with presumed malarial fever and

biliousness, and passenger deaths were reported following visits to Jaffa and Naples. The

Captain’s log only records smallpox after 22 March, and it is unclear why he sought

smallpox vaccination for himself on the 11 March while docked in Constantinople. The

ship’s doctor had no previous experience of smallpox. At Naples, all remaining 500

passengers were peremptorily disembarked and given tourist tickets, while the vessel left

port and sailed for Liverpool without communicating with the port on the nature of this

disease outbreak. The United States Marine Hospital Fortnightly Gazette reported that a

number of these passengers fell ill with smallpox at Naples and in other places in Italy

and France.72 Three persons subsequently developed the disease in Liverpool on dates

which indicated it was contracted prior to disinfection of the ship, which occurred later at

Liverpool. On 8 July 1900, the SS Ivernia from Boston also landed a single smallpox case

at Queenstown while en route to Liverpool.

Competitive, fast transatlantic passenger and mail steamers were efficient disease

vectors. Figure 3 illustrates three examples of transit involving two ships arriving during

the initial phase of the Liverpool epidemic.73 These ships left Boston during the period of

peak prevalence during the epidemic of 1901–3.

Dates in Figure 3 indicate when notified and not when the illness began. The SS Kansas

arrived in Boston on 15 January 1902 following one smallpox death at sea. The ship was

quarantined but the vessel was allowed to leave for its return trip to Liverpool after only

six days. When it arrived back in Liverpool, nine clinical cases were identified on arrival

and transferred to the Port Sanitary Hospital at New Ferry, one of whom died.74 The crew

had been vaccinated before leaving Boston but some were already incubating the disease.

69 Edward William Hope, Annual Report on the Health of the City of Liverpool during 1901 (Liverpool: C.

Tinling and Co., Printing Contractors, 1902), 39.

70 Thomas Clarke, ‘Introductory Address to the Section on Port Sanitary Administration, Royal Institute of Public

Health Congress, Liverpool, July 1903’, Journal of State Medicine, 11, 8 (1903): 454–61.

71 Port of Liverpool, Annual Report of the Medical Officer of Health to the Port Sanitary Authority for the Year

1900 (Liverpool: C. Tinling and Co., Printing Contractors, 1901), 16–17.

72 Ibid., 17.

73 Edward William Hope, Annual Report on the Health of the City of Liverpool during 1902 (Liverpool: C.

Tinling and Co., Printing Contractors, 1903), 26–51.

74 Port Sanitary Hospital, op. cit. (note 30). These men had different occupations, including baker, engineers,

firemen, carpenter, sailor and boatswain.

Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. IP address: 46.4.80.155, on 21 Dec 2020 at 20:26:58, subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at

https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms. https://doi.org/10.1017/mdh.2019.7412 Bernard Brabin

Figure 3: Neighbourhood smallpox transmission linked to imported maritime cases from Boston. Sources: Port

Sanitary Hospital Archives [note 30]; Annual Report on Health of the City of Liverpool during 1902 [note 73].

The Boston Health Department Chairman, Dr Samuel Durgin, received criticism in the

press for allowing the ship to depart after so few days of quarantine.75 At a legislative

hearing on an anti-vaccine bill, Durgin responded as follows to a critical heckler: ’I hold

the public health of Boston in one hand and its commerce in the other’.76 Commercial

interests in Boston were influential factors affecting public health regulations, at least

in this instance. The Health Department deliberately gave the outbreak a low profile to

prevent an unwanted scare. Press releases stated that alarm was needless and claimed

smallpox has never been epidemic in the city.77

The SS Devonian carried infected seamen on separate occasions in early December,

January and February. With the mild type illness, diagnosis was unclear until medical

advice on skin spots was sought.78 A further maritime case was identified on the SS

Campania arriving from New York on 5 April, on a ship holding the fastest transatlantic

crossing time.79 Multiple secondary Liverpool cases arose from these infected seamen,

especially through local lodging houses and contact with workhouse inmates. Seven

different ships were carrying infected passengers, and the SS Kansas imported nineteen

cases from Boston that were admitted to the New Ferry hospital. When the ship sailed

from Liverpool on 4 January 1902, two crew were treated at sea, one of whom died.

Late acquisition of smallpox explained these cases. Upon reaching Boston, as many as

twenty men were put ashore and all cattlemen were taken to the quarantine station and

75 ‘Eight Cases on Board’, The Boston Globe, 7 February (1902), 4.

76 Wallach, op. cit. (note 11), chapter three, ‘The 1901–2 smallpox epidemic in Boston and Cambridge’, 61.

77 ‘Alarm Was Needless. Smallpox Has Never Been Epidemic Here. Less than Two Cases in Every 3000 of the

Population of Boston’, The Boston Globe, 15 December (1901).

78 ‘Smallpox in Liverpool, a Fresh Case Reported Today. Forty-two Cases in the City’, The Liverpool Echo, 17

February (1902), 5.

79 ‘The American Mails, Performances Outward and Homeward. Cunarders to the Front’, The Liverpool Daily

Post, 11 April (1900), 3.

Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. IP address: 46.4.80.155, on 21 Dec 2020 at 20:26:58, subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at

https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms. https://doi.org/10.1017/mdh.2019.74United States and United Kingdom Smallpox Epidemics (1901–5) 13

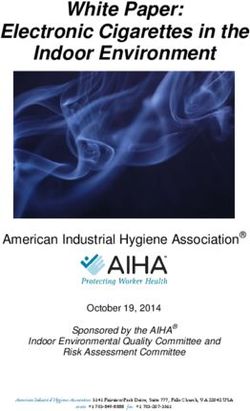

Figure 4: Commercial map showing the transatlantic trade connections of the Port of Liverpool in 1903. Source:

Appendix, City of Liverpool. Handbook Compiled for the Congress of the Royal Institute of Public Health, edited

by E.W. Hope (Liverpool: Lee and Nightingale, Printers, 1903). Map production Spottiswoode and Co., Ltd.,

Liverpool. Commercially developed: red, British Empire; grey, other countries. Detail of transatlantic section

from a world map.

revaccinated.80 Returning to Liverpool after leaving Boston, the SS Kansas put back to

New York and landed several further crew suffering from smallpox. Later arriving at

Liverpool on 6 February, nine convalescents and two contacts were identified and removed

to the Port Sanitary Hospital.81 Most of the crew were revaccinated and some were kept

under close observation.

Figure 4 shows the commercial trade connections of the Port of Liverpool and the

multiple potential routes for inward transmission of smallpox in 1903.82 Vessels from

Liverpool travelling west to Boston discharged first at St Johns, Newfoundland, and

Halifax, Nova Scotia. On the return journey, these vessels often travelled directly to

Liverpool. Between 1901 and 1902, only a single case of smallpox was reported in

Halifax, affecting a seaman on a schooner leaving Gloucester, north of Boston.83 No deaths

from smallpox were reported in St Johns during this period,84 which suggests westward

transmission of smallpox from Liverpool was negligible. The number of maritime cases of

80 Hope, 1903, op. cit. (note 73).

81 ‘The Smallpox, Liverpool, no Fresh Cases, Infected Cattlemen Removed to Hospital’, The Liverpool Daily

Post, 8 February (1902), 6.

82 City of Liverpool, in E.W. Hope (ed.) Handbook Compiled for the Royal Institute of Public Health, Liverpool

Congress, 15–21 July 1903 (Liverpool: Lee and Nightingale, Printers).

83 Alvey A. Adee, ‘A Case of Smallpox on Schooner Thalia at Halifax’, Public Health Reports, 16 (1901), 2176.

84 St Johns, Newfoundland. Register of Deaths St Johns City District, Book 3 (1901–2), 333–9.

Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. IP address: 46.4.80.155, on 21 Dec 2020 at 20:26:58, subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at

https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms. https://doi.org/10.1017/mdh.2019.7414 Bernard Brabin

Figure 5: Periodicity of Boston and Liverpool epidemics and dates of transatlantic ship sailings. Sources:

[reference notes, 43, 50, 53, 68, 69].

smallpox landed from vessels in the Port of Liverpool between 1900 and 1904 is shown in

Table 1 in relation to port origin and case fatality. The total number of identified cases

arriving from Boston represents 27% of all maritime cases. The months involved are

shown in detail in Figure 5, to illustrate occurrence in Liverpool and steamship arrivals

from Boston with diagnosed smallpox infected crew or passengers. Another 27% of

importations arrived from New York and Baltimore in 1903 and 1904. Other incoming

vessels from outside the United States were also responsible for importations of cases or

suspected cases of smallpox (Table 1), but the majority of single-country origin was from

the United States.

Maritime and Non-Maritime Spread of Smallpox in the United Kingdom

1901–5

The connexion between seaports and smallpox had been initially observed in England

in the epidemic of 1870–2, when Liverpool and London were the first places to feel the

effects of the continental outbreaks associated with the Franco-Prussian war. In Liverpool,

smallpox had been introduced by Spanish sailors.85 Liverpool experienced almost 2000

deaths in the 1871 epidemic, but these numbers decreased with 685 deaths during the

1876–7 epidemic and 34 deaths in the smaller 1881 epidemic.86

85 Hardy, op. cit. (note 13), 128 and 132.

86 Ibid., 128.

Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. IP address: 46.4.80.155, on 21 Dec 2020 at 20:26:58, subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at

https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms. https://doi.org/10.1017/mdh.2019.74United States and United Kingdom Smallpox Epidemics (1901–5) 15

Year Cases from ships Cases from ships arriving Annual Annual

arriving from Boston from other locations case totalb case fatality

n (%)a n (%) n (%) n (%)

1900 1 (3.7)c 26d 156 23 (14.7)

1901 5 (21.7)e 18 37 6 (16.2)

1902 20 (44.4)f 25 560 20 (3.6)

1903 4 (16.6)g 20 1720 141 (8.2)

1904 4 (66.6)h 2 27 2 (7.4)

Total 34 (27.2) 91 2500 192 (7.7)

a Percentage of Boston and East Coast United States transits of all Liverpool maritime cases for that year.

b Annual number of cases for the city of Liverpool.

c Single case landed at Queenstown, Ireland.

d Includes nineteen cases on ship from Boston via the Mediterranean; one case on ship from New York.

e Transported on two different ships.

f Transported on seven different ships.

g Four cases from New York. Sixteen different ships brought cases, or suspected cases, of smallpox.

h Four cases from Baltimore.

Table 1: Number of maritime cases of smallpox landed from vessels in Port of Liverpool 1900–4 in relation to

United States origin and case fatality. Sources: Annual Reports on the Health of the City of Liverpool during

1900–4; Liverpool Smallpox Register, Wirral Archives [reference notes 30, 93].

The 1901 Liverpool outbreak was the last major smallpox epidemic in this city. Its

magnitude was comparable to earlier 1876–8 outbreaks, as shown in Figure 6. Four

Liverpool epidemics had occurred between 1875 and 1896, which exactly corresponded

temporally with the London epidemics, spanning both the same years and having identical

epidemic periods. This suggests indigenous transmission between these cities. In contrast,

the Liverpool epidemic of 1901 commenced twelve months after onset of the London

epidemic and was characterised by milder infections and close association with imported

maritime cases. Yet in London during 1902, of ninety-three smallpox cases treated in their

Port Sanitary Hospital, only one was an imported infection from New York, admitted on

12 April from the SS Minnehaha.87 Other cases were internally transferred to London,

mostly from British Ports – particularly Newcastle, with additional single importations

from Spanish, German and Dutch ports, as well as India and South Africa.88

John Christie McVail (1849–1926), Medical Officer of Health for Stirling and

Dumbarton in Scotland, and a leading advocate of smallpox vaccination in the early

twentieth century, suggested that smallpox was no longer indigenous in the United

Kingdom and insisted that epidemic outbreaks were imported.89 He tabulated provincial

smallpox outbreaks in English and Welsh cities and towns between 1902 and 1905.90

Incidence estimates per capita can be derived from these case numbers using the 1901

United Kingdom National Census. These are listed in Table 2, and their spatial dispersion

mapped in Figure 7. Case fatality estimates are also tabulated for the same locations.

The Liverpool focus is distinct from those in Glasgow, London, Edinburgh, Tynemouth,

Hull and South Wales, which are all ports, but which did not have regular scheduled

87 Port of London Sanitary Committee, Annual Report of the Medical Officer of Health to 31 December 1902,

May 1903, appendix H, 83.

88 Ibid., appendix H, pp. 77–91.

89 McVail, op. cit. (note 49), 8, 26.

90 Ibid., p. 6 (Table II).

Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. IP address: 46.4.80.155, on 21 Dec 2020 at 20:26:58, subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at

https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms. https://doi.org/10.1017/mdh.2019.7416 Bernard Brabin

Location Period in Cases 1901 Census Period incidence Deaths Case fatality

yearsa population per 105 (%)

Lancashire & North-West England

Liverpool 1901–3 2280 684,958 333 160 7.0

Stockport 1902–4 159 78,897 201 15 9.4

Oldham 1902–3 413 137,246 301 32 7.7

Chadderton 1902–5 144 24,000 600 5 3.5

Wigan 1902–3 70 60764 115 1 1.4

Blackburn 1902–3 141 127,626 110 5 3.5

Salford 1902–4 262 220,957 119 12 4.6

Manchester 1902–4 563 543,872 103 33 5.9

Warrington 1903 86 64,242 134 4 4.7

Macclesfield 1903–4 69 37,500 184 5 7.2

Preston 1904–5 172 112,989 152 8 4.7

Bradford 1901 28 279,767 10 0 0.0

St Helens 1902–5 66 84,410 78 3 4.5

ALL 1901–5 4453 2,457,228 181 283 6.3

Yorkshire & Pennines

Ossett Union 1902–3 519 12,903 4022 61 11.8

Heckmondwike 1904 91 9500 958 5 5.5

Dewsbury 1904 552 28,060 1967 57 10.3

Leeds 1902–5 690 428,968 161 35 5.1

Halifax 1903 141 104,936 134 6 4.3

York 1902–4 39 77,914 50 7 17.9

Batley 1904 103 128,712 80 6 5.8

ALL 1902–5 2135 790,993 270 172 8.0

Central England

Leicester 1902–4 731 211,579 345 30 4.1

Derby 1903–4 255 105,912 241 5 2.0

Nottingham 1903–5 479 239,743 200 17 3.5

Sheffield 1902–4 141 380,793 37 5 3.5

Northampton 1902–3 44 87,021 51 9 20.5

Birmingham 1902–5 364 522,204 70 17 4.7

ALL 1902–5 2014 1,547,252 130 83 4.1

North-East England

Tynemouth 1902–5 328 51,366 639 17 5.2

South Shields 1902–5 272 97,263 280 14 5.1

Chester-le-Street 1903–4 106 34,000 312 6 5.7

Newcastle 1903–5 628 215,328 294 28 4.5

Durham 1902 35 419,782 8 1 2.9

Sunderland 1902–3 66 146,077 45 4 6.1

Hull 1903–4 141 240,259 77 8 5.4

ALL 1902–5 1576 1,204,075 131 78 4.9

South Wales and South-West England

Swansea 1902 187 94,537 198 187 17.1

Cardiff 1901–5 96 164,333 58 5 5.2

Portsmouth 1902–5 20 188,133 11 1 5.0

Bristol 1903–5 125 328,945 38 1 3.2

ALL 1902–5 428 479,948 89 39 9.1

Table 2: Continued on next page.

Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. IP address: 46.4.80.155, on 21 Dec 2020 at 20:26:58, subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at

https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms. https://doi.org/10.1017/mdh.2019.74United States and United Kingdom Smallpox Epidemics (1901–5) 17

Figure 6: Periodicity of London and Liverpool smallpox epidemics between 1875 and 1905. Sources: [reference

notes, 27, 63, 93].

Location Period in Cases 1901 Census Period incidence Deaths Case fatality

yearsa population per 105 (%)

London

Greater London 1901–2 9484 6,226,494 152 (203)b 1540 16.2

Scotland and Ireland

Glasgow 1900–4 3413c 762,000 448 371 10.9

Edinburgh 1900–4 191 303,638 63 16 8.4

Dundee 1903–4 175 154,734 113 12 6.9

Rest of Scotland 1900–4 2844 3,251,731 87 235 8.3

Dublin (hospital) 1903–4 243 448,000 54 33 13.6

a Annual periods may not include all months of the year dependent on month outbreak commenced or resolved.

b Brackets is incidence estimate based on inner city London population alone.

c Includes some cases from beyond city boundaries.

Table 2 (Continued): United Kingdom smallpox period incidence and case fatality 1900–5. Sources: McVail,

Table II, 6 [note 49]; Martin, Table II, 19 [Journal of Hygiene, 34, 1(1934)]; UK Census, 1901 [note 39].

Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. IP address: 46.4.80.155, on 21 Dec 2020 at 20:26:58, subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at

https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms. https://doi.org/10.1017/mdh.2019.7418 Bernard Brabin

Figure 7: United Kingdom spatial smallpox period incidence per 105 population 1900–5. Sources: McVail, Table

II, 6 [note 49]; United Kingdom National Census, 1901 [note 99].

transatlantic links with eastern United States seaports. In Southampton, only two cases

of smallpox were reported on vessels bound for the port in 1902.91 Smallpox outbreak

distribution shows temporal dispersion across northwest and central England between the

years 1902 and 1904. The dispersion pattern implicates Liverpool as the primary focus,

possibly with discrete sequential transmission across the northwest during these years.

In these outbreaks, case fatality was low or very low (Table 2) and in the northwest

averaged 6.3%. This mortality was much lower than in the 1901 London epidemic (21.6%),

suggesting that infection was mostly due to a different milder strain, consistent with

transmission mainly from the Liverpool focus where a mild strain of Variola minor was

dominant. Chapin had considered it highly probable that the mild type of smallpox was

carried to England from Boston in 1902 and during the following years.92 Case fatality

during the epidemic decreased from around 16% in 1901 to 8% in 1903.93 As all cases

were hospitalised, this may have caused a bias towards observing severe or fatal cases.94

91 Southampton 1902 Public Health Report, 26.

92 Chapin, op. cit. (note 3).

93 Annual Reports on the Health of the City of Liverpool during 1900 to 1904 (Liverpool: C. Tinling and Co.,

Printing Contractors, 1901). Estimates compiled from figures available from Annual Health Reports produced by

Dr E.W. Hope, Medical Officer of Health for Liverpool, for the years 1900 to 1904, and published in the years

1901, 1902, 1903, 1904 and 1905.

94 Martin Eichner, ‘Analysis of Historical Data Suggests Long-lasting Protective Effects of Smallpox

Vaccination’, American Journal of Epidemiology, 158 (2003), 717–23.

Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. IP address: 46.4.80.155, on 21 Dec 2020 at 20:26:58, subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at

https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms. https://doi.org/10.1017/mdh.2019.74You can also read